ABSTRACT

This essay examines the intersection of queer, trans, and feminist politics with artistic research. It begins with a discussion of knowledge and form, arguing that we need to reinvent the formal structures of academic knowledge production in light of the digital revolution. I then examine two sets of examples of the scholarly video essay: three from a videographic journal I edit and three from my own practice. Such examples allow us to rethink or even to reinvent the embodied situatedness of researchers from a new perspective: the audiovisual body. I offer the “prophetic” to name this emerging mode of articulation.

Read this book like a song. (Tinsley 1)

1. Knowledge and form

“Artistic research” is one of several terms currently used to describe hybrid forms of scholarship that radically contest the equation of academic knowledge with written texts. What these developments share is a determination to figure a mode of production that is historically other to academia as no longer constitutively outside but instead integrally present within academic research. In this regard, they dovetail with longstanding conversations in some strands of performance studies (MacDonald and Riga), which have long examined the place of performance practice within performance studies, including “performance itself as an act of publication” (Shaffer 55). In the United Kingdom, where I work, the dominant term is “practice as research” (Allegue et al.; Nelson), now increasingly shortened to “practice research” (Hann), while in Canada it is “research-creation” (Manning and Massumi; Loveless). I have co-edited a volume on “performance as research” (Arlander et al.) and staked my own claims on the concept of “embodied research” (Spatz, Blue Sky Body). Each of these phrases carries its own geographies and genealogies and offers its own perspective on an emerging but still incomplete paradigm shift according to which art, practice, creation, performance, and even embodiment itself are no longer framed as objects of research but instead become the methods, methodologies, and forms through which knowledge is generated and shared. If I use the European term “artistic research” (Borgdorff; Assis) in this article, that should not be taken as a simple endorsement or a stable commitment. I use the term here strategically, because of how it foregrounds a particular aspect of the broader paradigm shift that remains underdeveloped: namely, the question of form.

As Michael LeVan observed some years ago, digital and multimedia environments offer new kinds of “hospitality to performance praxis” in which “[a]esthetic and epistemic concerns” may interact through “dynamics of friction and encounter” (LeVan 213). As far back as 2005, he notes, the journal Liminalities was publishing multimedia scholarship, “challenging the supplementarity of documentation for performance” and inviting practitioner-researchers to develop new forms of “digital thinking.” Following the philosopher Jacques Rancière, LeVan even suggests that “the forms” (italics original) engendered by the interaction of performance and the digital are “emerging as a potential center for the field,” with implications linked to emancipation and the politics of aesthetics (218). Yet, despite the continued growth of digital publication platforms, relatively little has been established when it comes to the aesthetics and epistemics of particular multimedia forms. Academic disciplines are historically founded on the circulation of documents made of written words (as well as musical and especially mathematical notation). With the stability and form of the written text increasingly decentered in today’s digitally networked systems, one might observe with John Law that “the division of labour which founds the academy, between the good of truth and such other goods as politics, aesthetics, justice, romance, the spiritual, inspirational and the personal, is in the process of becoming unravelled” (15). But where are the substantively new forms of scholarship that would articulate such an unravelling? Where are the successors to the text-based article, the “new forms of philosophy” that transform “what it means to think” (Maoilearca 108, 110)? In which specific forms are we able to ask ourselves “what thinking can possibly mean in the civilization in which we find ourselves?” (Haraway 130).

The form of a work – book, audio recording, live broadcast, film, zine – is not strictly separable from its knowledge content. While the passages between some forms may seem relatively frictionless (article into book chapter; film into video), distinctive media inherently define and contour the types of knowledge that may be incorporated within them and thereby also who can be recognized as an expert in the fields to which they contribute. In a contemporary digital context, scholarly articles circulate online alongside blog posts, movie trailers, and memes. Yet we are far away from anything like agreed best practices – let alone style guides – for scholarly publications that exceed the textual. Nor can it be said that we have escaped the hierarchy of knowledge according to which “too much effort doing performance at the expense of studying performance can make suspect a tenure case,” or the general dependence on textual forms for all kinds of academic assessment (LeVan 210). At this moment, multiple contradictory approaches are at work simultaneously, reconfiguring relations between documents and institutions and between textual and audiovisual modes of communication. What are the forms and structures by which text, image, sound, video, and interface can be integrated within a research publication? Which epistemic modes and rhetorical strategies are realized by particular juxtapositions of media? If there is such a thing as digital thinking, what are its present genres, styles, platforms, and techniques?

My focus in this article is on the form of publications and the particular ways in which practitioner-researchers and artist-scholars can triangulate embodiment, textuality, and audiovisuality to generate works and modes of thinking that are irreducible to written scholarship, video artwork, or live performance. Some obvious precedents for audiovisual thought include visual ethnography (Taylor) and the “essay film” (Papazian and Eades). Yet what interests me here is not only the mixing of textual and audiovisual media but also, crucially, the implications of this mixing for the embodiment of the researcher. In other contexts, I have argued on behalf of “embodied” research methods, in which the embodiment and embodied practice of the researcher is central to the methodology. Here I want to focus on the ways in which this embodiment is or is not carried forward into the form of publication. We might think of research as defined by two epistemic “cuts”: an opening cut, which sets initial conditions for something interesting to occur; and a closing cut, the means by which that unexpected “something” is traced, analyzed, recomposed, and shared beyond its original context.Footnote1 Embodied research, as an opening cut, can include many different methods, from traditional ethnography, performance ethnography, and autoethnography through to artistic practice and all forms of personal and socio-cultural “autoexperimentation” (Preciado 247). Yet, time and again, within present scholarship, these diverse embodied methods are returned to the conventional medium of academic epistemology: the written text as closing cut. My appeal to “artistic research” here emphasizes alternatives to this return: forms of publication in which the technology of writing itself is decentered as the privileged technology of epistemic closure. I not only want to argue that new forms of publication afford new ways of thinking. I also want to claim that such new forms imply new institutional structures, new communities of knowledge, new ethical positions, and new political interventions. In this article, I develop that claim by drawing links between artistic research and what I propose to call the queer prophetic.

I want to argue that there is something potentially, although not necessarily, queer about the position of the artist-scholar or practitioner-researcher, and that this queerness is located not only in the act or practice of doing research but also in the forms through which that research is shared. These forms, I suggest, might at their most radical constitute a new mode of articulation, or even a new kind of thought, in which the embodied and the critical are integrated – or rather, mutually incorporated – to a degree that I will call prophetic. This does not happen automatically, nor would I claim that it is widespread or even clearly established as a possibility. Rather, it is a potentiality that I have observed and been searching for, both in my own work and in that of others, in situations where embodiment, textuality, and audiovisuality come into new relations within digital media. In the present context, I will not be focusing on performances or installations that make use of digital media. Instead, my starting point will be what I call the archival obligation of academic research: the responsibility of researchers to generate transmissible documents that can circulate beyond their original contexts and support both synchronic and diachronic communities of knowledge. What interests me here is the unmaking of text/body and theory/practice dichotomies through the introduction of a third term – the audiovisual – which reveals the asymmetry of the other two. In other words, I believe that practical experimentation with the relationship between textuality and audiovisuality can help us reconceive how both of these relate to embodiment.

I am not the first to suggest connections between artistic research, digital media, and queerness. It has even been argued that artistic research is always already queer, because of its engagement with desire, embodiment, and mess. According to Alyson Campbell and Stephen Farrier, queer artistic research is

attracted to messiness as a methodology, where messiness is imbricated with queerness and where cleanliness in knowledge production is associated with knowledge forms that have routinely occluded the queer and the non-normative in an effort to tidy up hypotheses and conform to hegemonic forms of “rigour.” (84)

In the queer prophetic as I understand it, video and audiovisuality are not operative only at the level of method, to be converted into writing at the time of publication. Rather, the queer prophetic demands that scholarship take audiovisuality into account as a form of knowledge in its own right. This means that the embodiment of the researcher, which had previously oscillated between intentional concealment (in the distanced objectivity of “hard” methods) and discursive revelation (in the acknowledgment of positionality and standpoint, discussed below), potentially comes to the fore in an entirely different way. My suggestion will be that academia itself, precisely because of the way it has historically equated writing and knowledge – just think of how often we refer to the “thought” of a philosopher when we actually mean their writing – is ill prepared to grapple with audiovisuality as mode of thought and will require additional resources to do so. In particular (and in alignment with Haber’s political commitments, if not his methodological bent), I will be looking to feminist, queer, and queer of color critique for understandings of the queer prophetic that go beyond what academic institutions are currently able to recognize. For example: Recognizing that “aesthetics and image matter deeply” and that “the question of the visual is always also a question of the political,” the editors of Trap Door, a recent volume on the politics of trans visibility, distinguish between the “trap of the visible” and doors leading to “new visual grammars” (Gossett et al. xix, xxiv, xv, xviii). Artistic research, I suggest, can be understood in exactly these terms: On the one hand, it may function as a kind of trap within which all manner of queerly creative and even antiracist and decolonial activities and practices are politically contained within conservative epistemologies. This is certainly the dream of the neoliberal university, in which creativity and culture are instrumentalized for economic gain. On the other hand, artistic research may yet be a door or a threshold through which some of us manage to smuggle tools that could eventually transform academic institutions and their hierarchies of knowledge. It is not that new technologies will effect such changes on their own – obviously, the politics of their implementation will depend upon much broader social movements and forces – but that academia remains an important site at which to contest what counts as knowledge.

Many of the arguments made on behalf of artistic research and non-textual forms of thought are inevitably formulated in writing – like this article – as they would otherwise be unintelligible in an academic milieu that still runs on texts. These arguments, in their emphasis on embodied and affective excess, seem at least potentially allied with contemporary critical approaches to gender, sexuality, and race. On the other hand, the cultural and institutional limitations of contemporary discourses promoting artistic research – notably its predominant and largely unacknowledged whiteness (Kramer and Misa) – have meant that they have largely failed to engage with the politics of identity as part of what is inevitably staged when the body of the researcher appears audiovisually. There is then a gap between artistic research, as it has been institutionalized thus far, and the queer prophetic ends to which its methodological innovations could be put. To bridge this gap, it will be necessary to examine more carefully the epistemological consequences of new media forms and the unique capacities of audiovisuality to (re)situate the body of the researcher.

2. Embodiment, textuality, audiovisuality

When it comes to the queering of scholarly form, few established models exist, but there are many different pilot projects and prototypes that might be considered. The journal Liminalities, edited by LeVan, is a particularly longstanding one. In Europe, perhaps the best-established platform that explicitly pushes formal boundaries is the Journal of Artistic Research <http://jar-online.net/>, run by the Society for Artistic Research, which publishes peer-reviewed research online in the form of nonlinear “expositions.”Footnote2 With its open-ended, web-based design, JAR and its underpinning platform, the Research Catalogue, could be said to represent one end of the spectrum of artistic research forms: that emphasizing openness and nonlinearity, as do some of the multimedia works published in Liminalities. At the other end of the spectrum we might locate the PhD dissertation project of hip-hop artist-scholar A. D. Carson, recently completed at Clemson University in South Carolina, which took the form of a rap album and cited Stefano Harney and Fred Moten to identify itself as a work of “Black study and fugitive planning” (Carson). While the form of the doctoral dissertation is opening up radically in Europe (see Artistic Doctorates in Europe), this formal touchstone of PhD completion has been much more difficult to shift in the United States, where a book-length written text is still almost always required. Carson’s thesis notably replaces the book with a different form – the album – that is both structurally linear and well-established.

Today, even long-established journals increasingly include multimedia in some form, whether as linked or embedded references within textual articles or (less often) as standalone contributions. While these vary widely in form, I will focus in the rest of this section on two sets of examples with which I am closely familiar and which foreground the potential of a somewhat narrower and more specific medium: the video “essay” or linear video work. As will become clear, I am interested in this form because of the way it allows for the layering and mutual imbrication of textual and audiovisual elements within a container (the video file) that itself is clearly defined by particular technological parameters. I take this as a useful model through which to focus on and engage in detail with a sprawling landscape of possible forms. Among the advantages of linear audiovisuality are: its relatively long history, dating back to the advent of cinema; its relative technological stability, in comparison for example with a website; and increasing accessibility for both viewers and creators. Moreover, the linear video form offers an opportunity to explore the relationship between textuality and audiovisuality from a perspective that reverses the established hierarchy of knowledge: Rather than inserting videos within a written text, the question becomes how text can be embedded within a video. This formal, aesthetic, and epistemological question is my focus here.

The first set of video works I want to consider have been published in the Journal of Embodied Research <https://jer.openlibhums.org/>, which I founded in 2017. JER is a peer-reviewed, open access journal that exclusively publishes video articles. As such, it is defined by two basic parameters: embodied research as topic and method, indicated by its title, and the video article as a scholarly form. Unlike most academic journals that publish video, JER does not publish any accompanying text or research statement alongside the video work. A transcript of each video article is published, making its textual contents legible to both search engines and accessibility tools, but this includes only text that is spoken or written within the video. In fact, the process of transcription provides a useful definition of textuality for my purpose: “Text” here refers to everything in a video article that can be directly transcribed into writing. Such a definition applies equally to words that appear onscreen and to (the verbal content of) recorded speech – an equation that already reveals the extent to which the technology of writing shapes our understanding of speech. I have come to see JER as a platform for experimenting with relationship between textuality and audiovisuality through the video article form, as well as the relationship of this form to underpinning methods and practices of embodied research. Through the journal, questions about knowledge and form become usefully concretized: What are the different ways in which textuality can be embedded within audiovisuality? What kinds of knowledge can be articulated through this form? To what extent can knowledge transmission be “implicit” and what do we even mean by implicit or explicit in the context of videographic forms? The first eight articles published in JER, between 2018 and 2020, provide a useful window into some of the ways in which embodied and artistic researchers are beginning to answer these questions.Footnote3

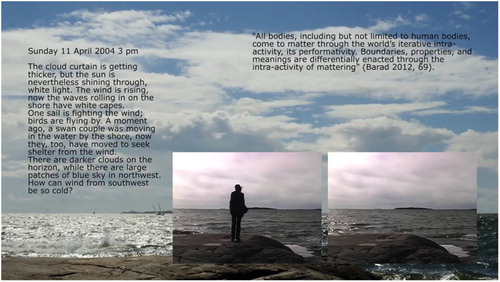

Annette Arlander has pointed to the sometimes overlooked connections between current debates in artistic research and feminist work of the 1970s on standpoint epistemology and situated knowledge (Arlander et al. 343). In her video article in JER 1.1, “The Shore Revisited,” Arlander makes use of nearly continuous voiceover alongside an elegant montage of “performances for camera,” which show her appearing and disappearing, present and absent, according to patterns of repetition that unfold over days or months on Harakka Island off the coast of Finland (Arlander) (). The voiceover is complex, narrating the interaction of multiple moments that appear juxtaposed as embedded videos onscreen. Arlander’s voice, speaking back to those moments, mixes in the audio track with the sea and wind sounds of the earlier recordings. Written texts also appear onscreen throughout the article: both academic quotations and fragments from Arlander’s journal entries, as well as an occasional scrolling text within the embedded videos, which sometimes echo and sometimes supplement the patient and probing analysis of the voiceover. I want to suggest that there is already something queer at work here, in the fragmentation and recomposition of the researcher’s multiple bodies – visible, audible, and textual – as they appear and interact with each other in the article. We might think, for example, of what Rebecca Schneider has identified as a crucial move made by performance artists like Carolee Schneemann, who become “both subject and object at once,” both “seer and seen,” in works that feature their own bodies but over which they retain artistic control (Schneider 74; and see Jones). But while Schneider emphasizes the empowering coherency of a process in which the artist sutures together both sides of the subject/object division, I see here (as well as in Schneemann and other precedents) something more like a generative fragmentation manifested by the interaction of multiple elements. In “The Shore Revisited,” the juxtaposition of textual and audiovisual elements works not to unite subject and object, but instead to unmake and remake the researcher’s body, revealing its inextricability from time and place. Arlander, as the author of the work, appears multiply, across multiple moments, even multiple bodies, differentiated from one another, rather than as a coherent whole.

Figure 1. Video still from Annette Arlander (Citation2018), “The Shore Revisited.” Journal of Embodied Research 1(1): 4 (30:34). doi: 10.16995/jer.8.

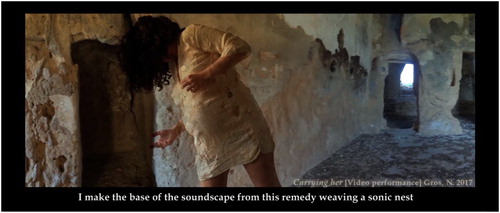

Across the first eight videos published in JER, voiceover is the most common technique by which textual information is conveyed. This likely reflects not only enduring assumptions about the necessity of propositional argumentation in research, but also a lack of practical alternative techniques. The voiceover is clearly distinct from what it “voices over” and, my previous point notwithstanding, to a certain extent intrinsically consolidating. This is especially the case when voiceover employs a rhetoric of explanation or framing, speaking to the video as if from outside it. Yet the voiceover is not an external text. It exists within the video document and remains in dialogue with it, bound to its linear temporality. In another JER video article, “Carrying the Nest: (Re)Writing History Through Embodied Research,” Nilüfer Ovalıoğlu Gros begins with a voiceover in Turkish, accompanied by subtitles in English (Gros). This is already a layering of two bodies: a spoken Turkish body and a written Anglophone body, both appearing together, alongside an old photograph of a Turkish city. The Turkish voiceover is soon accompanied by singing, even as the photo is overlaid by video showing a flock of birds in flight. Later on, Gros’s own visibly pregnant body appears repeatedly as a moving image. Throughout her article, Gros layers and juxtaposes archival images, video performance, personal recordings, and the sound of singing with textual quotations, subtitles, references, captions, and voiceover (). The result is a complex interweaving of history and memory in which themes of exile and embodiment are addressed through a decidedly nonlinear tapestry, woven into the linear form of the video article. The body of the researcher is undeniably present here, in ways that it could not be in a written text. Yet, the complex and layered form of the video article seems again to counter the integrity or authority of that body, instead presenting its thorough enmeshment with memory and history.

Figure 2. Video still from Nilüfer Ovalıoğlu Gros (Citation2019), “Carrying the Nest: (Re)writing History Through Embodied Research.” Journal of Embodied Research 2(1): 3 (23:30). doi: 10.16995/jer.23.

Falk Heinrich takes a contrasting approach in his video article, “To Be a Work Means to Set Up a World: Into the Woods with Heidegger” (Heinrich and Wolsing). Responding differently to the same formal problem, Heinrich speaks continually throughout the video – in Danish, with subtitles – but not as voiceover. Rather, his speech is entirely diegetic, originating at the same time as the primary audiovisual recording and incorporating dialogue with his co-author as well as a first-person testimony: “Now I am here … ” (). This type of voicing is very different from voiceover. More immediate and vulnerable, such speech is bound to the audible and visible moment of its recording, not amenable to multiple takes or revisions. Heinrich narrates his own process as he helps artist Thomas Wolsing in the creation of a site-specific artwork, the entire process being recorded on a head-mounted action camera. The resulting video article is technologically simple, involving minimal video editing, yet the relationships it implements between embodiment, textuality, and audiovisuality are complex. Interestingly, the moment when Heinrich is drawn most deeply into the physical labor of artmaking is also a point at which the audiovisual image fades, almost disappearing behind a scrolling text: an analysis of the moment that links it to a passage by Heidegger and which could not have been made in the moment. Springing forth at this moment of deeply embodied practice and taking over the screen, the written text simultaneously evokes embodiment and highlights its inaccessibility to both writing and video.

Figure 3. Video still from Falk Heinrich and Thomas Wolsing (2019), “To Be a Work Means to Set Up a World: Into the Woods with Heidegger.” Journal of Embodied Research 2(1): 1 (19:27). doi: 10.16995/jer.13.

These are some of the ways in which JER contributors have implemented the layering and composition of textual and audiovisual elements, aiming – I would argue – not to consolidate an authoritative and coherent subject position but to share embodied knowledge through complex articulations that are woven from particular, emergent interactions of particular bodies, places, and techniques. Further analysis of JER video articles could focus on the structure of authorship in videographic works – where, for example, I have encouraged contributors to include as co-authors those whose bodies and practices contribute materially to the article, even if they were not responsible for the recording and editing process (like Wolsing in the previous example). As JER continues to grow, every contributor faces the question of how best to articulate their embodied research in this specific form of audiovisual scholarship. However, keeping my focus here on relations between textuality, audiovisuality, and embodiment in the video essay form, I now turn to a second set of examples, drawn from my own work as a practitioner-researcher.

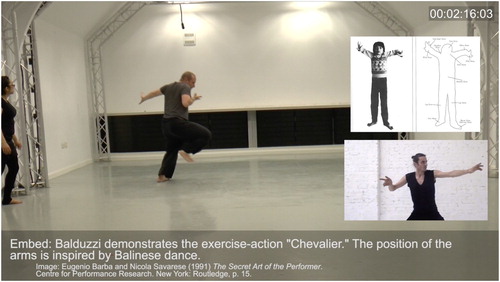

I have been creating video works since 2015, when I first began to take seriously the idea of video as a form of scholarship.Footnote4 In these works, I have rarely used voiceover, instead seeking other ways to compose words, images, and sounds. At first, my approach to the layering of textuality and audiovisuality was rigidly structured and attempted to establish a kind of analytical authority over the audiovisual material. This is evident in one of my first video essays (Spatz, “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions”), from 2015, which uses explanatory texts, video clips, and one still image to augment and contextualize four minutes of physical performer training that I led with two undergraduate students ().Footnote5 The added elements essentially mount an argument for the legitimacy of the transmissible embodied knowledge documented in the video. They identify individuals and exercises; draw textual and audiovisual connections between what is shown and related practices, more or less distant; and cite scholarly works, both to provide context for the exercises and to theorize them as epistemic objects. Although there is little speech in the video, the absence of voiceover allows the rhythms of the practice to become audible through the breathing of the practitioners and the sounds of their movement in the theater studio. Following a convention of more distanced research, in these textual annotations, I refer to myself in the third person.

Figure 4. Video still from Ben Spatz (2015), “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions.” Urban Research Theater. https://urbanresearchtheater.com/2015/08/12/training-with-a-sequence-of-exercise-actions/.

A comparison between this video essay and a 2018 video article (Spatz et al., “Diaspora”) reveals how profoundly my approach to videographic composition changed during this period, largely as a result of my intensive collaboration with Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Agnieszka Mendel, and a series of guest participants during the research project “Judaica: An Embodied Laboratory for Songwork” (see Spatz, “Molecular Identities”). One of these guests, performer-anthropologist Caroline Gatt, introduced a new way of working with books into the Judaica’s practice (see Gatt), which deeply impacted my understanding of textuality in relation to both embodiment and audiovisuality. The new audiovisual embodied research method that crystallized during the Judaica project is too complex to describe here.Footnote6 However, several key differences can be noted between the two videos, produced before and after that project:

Title: In the 2015 video, the title “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions” refers to what I understood us to be doing at the time of the recording: a sequence of exercise-actions. In contrast, the title “Diaspora” appeared only after the recorded session, when I watched the video material and had a strong impulse to shape it into an exploration of that concept. This is a major and epistemologically significant difference in the relationship between text and video: In the first case, a single title or conceptual frame holds and unites both embodied practice session and subsequent video essay; in the second, video emerges from a more open-ended process and only in retrospect suggests a concept/title.

Power dynamics: In the 2015 video, I am clearly the teacher, working with undergraduate students, and the hierarchy of knowledge transmission is unquestioned. In the 2018 video, I am working in a complex milieu defined by shifting relations amongst peers. In this context I am not teaching at all, but rather improvising and experimenting in the moment.

Videography: The primary video track in the 2015 video is shot on a stationary, tripod-mounted camera, providing a sense of stability and objectivity in relation to the documented event. In the 2018 video, the camera is mobile, wielded at different times by two different members of the team (Eda and Agnieszka), both of whom are also present as singing and moving performers in the video. This approach offers an intimate and emergent tracing of the event that is very different from a documentary approach.

Montage: The primary video track in the 2015 video is uncut (without edits), with additional information following along and responding to the temporality of the documented practice. The first 10 minutes of the 2018 video follow the same logic, honoring the linear temporality of the practice, while the remaining 20 minutes explore other approaches to editing, including several kinds of audiovisual montage.

Parameters of the practice: The 2015 video focuses strictly on “embodied” technique: movement-based exercises-actions in an empty room. The 2018 video incorporates drawing materials (paper, pencils, charcoal, eraser) as well as books, intentional clothing choices (if not quite costuming), and other objects, while still retaining a central focus on embodied practices like singing, speaking, and drawing.

Textual design: In the 2015 video, all supplementary textual information appears at the bottom of the screen in a visually separated, partially transparent bar. In the 2018 video, text is placed on screen in a variety of locations, as an element of visual composition that responds to and even actively plays with the moving image it annotates.

Textual content: In the 2015 video, the textual layer is narrowly focused on developing a coherent argument about the epistemic status of the documented technique. The 2018 video includes much more widely ranging text, from basic information about the participants to autoethnographic material and the repetition of words being read or spoken aloud. At one point, video of me retelling a story from childhood is accompanied by two simultaneously scrolling columns of text, one showing the story in its official, published form and the other offering an autobiographical comment about how I came to memorize that story – three simultaneous texts, if transcribed ().

Figure 5. Video still from Ben Spatz with Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Agnieszka Mendel, and Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz (2018), “Diaspora (An Illuminated Video Essay).” Global Performance Studies 2.1 (30:48).

In a third video work, yet to be published (Spatz et al., “He Almost … ”), I have inserted more than 50 scholarly quotations and references into a single uncut video recording lasting 30 minutes. The result is challenging; more than one set of peer reviewers have complained that the work fails to properly articulate any underlying research questions or arguments. Yet for me, this video goes further than my others toward a queer prophetic mode of articulation, foregrounding the prophetic as embodied action and performance (). I believe this video is perceived as illegible because reviewers expect its textual elements to frame its audiovisual elements and this does not happen. Instead, I challenge the viewer to recognize the citations and quotations as having been inserted into a flow of audiovisual thought, just as they would be inserted into a flow of written prose. I want the viewer to recognize the critical rigor of the selection and placement of these texts as providing further depth and context to what is already present as a flow of thought in audiovisual form. This seems possible to me because, as I placed each textual annotation, I knew that I was not simply embroidering or decorating the raw video. Rather, I experienced myself to be doing exactly what I do when I insert a quotation into a written article: namely, fleshing out a concept or argument by linking it to what others have said. With this in mind, I have begun to refer to such textual annotations as “illuminations.” Reversing the epistemic structure of medieval illuminated manuscripts, in which visual illustrations augment aspects of a primary textual work, in “illuminated video” it is the inserted texts that augment, expand, contextualize, comment upon, illuminate, deconstruct, problematize, and offer generative criticism to a primary flow of audiovisual thought.Footnote7

Figure 6. Video still from Ben Spatz with Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Caroline Gatt, and Agnieszka Mendel, “He Almost Forgets That There is a Maker of the World.” Unpublished work in progress.

The act of inserting critical texts within a video recording that includes my own audiovisual body seems to draw upon my entire self; or rather, it seems to combine my selves in a way that is simultaneously deconstructive and open-ended. At the same time, this approach breaks radically with scholarly convention insofar as my textual voice, my writing self, does not appear. In this form of work, I rarely or never arrive in the mode expected of a scholar or critic, as a contextualizing or explanatory voice. I am textually absent, an absence that I hope might stand as a challenge to the viewer, inviting them to make connections between two other kinds of thinking: the thinking (embodied, psychophysical, sung) that is traced audiovisually, owing to the combined practices of everyone who was present, and the thinking (critical, contextual, interdisciplinary) by which I select and place quotations into that recording. In this way of working, I cannot say that I am integrating or bringing together different selves. The quotations I insert do not aim to generate a synthesis. Instead, they often have a critical relation to the audiovisual layer: unpacking, unraveling, disaggregating. In these videos, my own documented embodiment is amplified and at the same time made vulnerable, problematized by a host of other voices, which I have (merely) selected. This experience leads me to ask: What would be videographic thinking if we did not assume that thought takes place only in editing, or only in performance, but instead focused on the relation between those moments? When I sit down to edit traces of my own audiovisual body, must I choose between a coherent framing that consolidates and a critical intervention that deconstructs? Must I write either with or against my audiovisual self? I feel that I have only just begun to formulate these questions, let alone to answer them. Going further, I suggest, will require other resources, including those to which artistic research has thus far insufficiently turned, but upon which its future may depend. It is to these “other” resources, and their challenges and invitations, that I turn in the next section.

3. Accounts and appearances

Since long before the audiovisual body of the researcher could make a literal appearance within a research document (with the important exception of some ethnographic films), feminist thinkers have attempted to situate the knower or thinker by verbal means. This occurs most clearly through what became, in the 1970s, a particular use of the word “as” to declare one’s identifications as a premise for one’s arguments: “I write this as a woman” (Cixous 875). Nancy Miller traces the evocation of the personal in a range of feminist texts that “mark the body’s presence, or personalize it; speak autobiographically or representatively” (Miller 7). The back cover of her book asks:

If according to the current protocols, every “I” must be located as an “as a” (as, for instance, a middle-aged, white, East Coast feminist), where does what’s left over get placed in a singular critical act? Does what’s left over get left out because it doesn’t fit the categories: too personal, too embarrassing to be taken seriously?

At stake in the “as” is the place of the researcher and their embodied identities in a particular work or context. For some time, the question for scholars has been how the body and embodied practice can appear in writing, a concern that has animated not only feminist theory but also anthropology (Stoller) and sociology (Wacquant) and which has ongoing importance for trans scholarship: “How do trans and genderqueer poets write the body onto and against the page?” (Blackston). But in emerging modes of artistic research, something else becomes possible: The body of the researcher – or at least, some traces of some aspects of that body – can now appear in the research audiovisually. Not instead of but in addition to verbal identifications, the researcher’s aural and visual appearance are increasingly traced and archived. The idea of writing “as a woman” therefore needs to be reexamined in light of two different developments, which we might suspect are related, at least historically: first, a recognition of the incomplete and discursively constructed status of the category of woman, as foregrounded by queer and trans feminisms (Stryker and Whittle); and second, the question of how to understand the “as” preposition when thought takes place audiovisually. In other words: What happens to the “as” when critical thought enters the audiovisual domain? How might these verbal or textual “as” statements be transformed by the presence of audiovisual embodiment, and vice versa?

It is a habitual and commonplace assumption that how one looks and sounds should or does not matter, especially in relation to “thought” and scholarship. This view is explicit in technoscientific research, where it has been duly questioned by feminist and postcolonial science and technology studies (Harding), but it is equally present in today’s “colorblind” ideologies of race that purport to ignore visible racial identity (Catanese). Underpinning this assumption is the idea that a person’s true or authentic qualities come through more transparently in words than in visible or audible appearance, an assumption that combines the modernist concept of the transcendent individual subject with a much older logocentrism to imply that what we put into words is the key to our “inner” character. From that perspective, audiovisual embodiment is merely a distraction from what one really has to say (where “say” again refers only to those aspects of speech that can be transcribed in words). Perhaps, in a context where audiovisual embodiment is very expensive, there could be a kind of validity to such logocentrism, insofar as writing might be a more democratic means of expression. In such a context, it might be that only celebrities can appear onscreen, while anyone can pick up a pen and write. But this imbalance no longer holds, if it ever did, in a digital and audiovisual age. The fact that so many of us now carry tiny, high resolution video cameras in our pockets only reveals the extent to which audiovisual bodies have always mattered. The prioritization of the written word, while in some cases perhaps justifiable, now starts to look like a flattening of identity that has more in common with patriarchal and colonial fantasies of neutrality and “colorblindess” than with radical democratization.

One of the points made mostly clearly in recent scholarship about and from queer, trans, and racialized identities, which artistic research might do well to consider more deeply, is that audiovisual embodiment is as real an expression of the self as is the written word. What if we were to reject “negative theories of appearance,” those that dismiss appearance as merely superficial, and instead recognize what Madison Moore calls “fabulousness” as “creative labor, a type of ‘self-couture,’ where our bodies become the site of artistic expression and creativity” (Moore 42, 44)? What if we recognized, in other words, that it absolutely does matter how one looks and sounds? If the prevailing assumption is that acknowledging audiovisual embodiment will automatically reinscribe patriarchal, racist, and ableist norms, it is nevertheless not at all clear that a predominantly textual politics can counteract those norms. Rather, it would seem that what we need is a radically alternative approach to audiovisual politics. If it matters how one looks and sounds, then the politics of that mattering will depend on how audiovisuality and textuality mutually construct each other in relation to that which underpins them both: embodiment as life and practice. And since it is no longer possible to ignore or dismiss the audiovisual body, that body must become a central point of analysis, debate, and intervention – as happens when disallowed and abjected bodies make themselves audiovisually present in the public sphere, contesting what Hannah Arendt called the “space of appearance.” As Nicholas Mirzoeff writes, regarding ongoing racist police violence in the U.S. and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement:

Here I will call the interface of what was done and what was seen and how it was described as “appearance,” especially as the space of appearance, where you and I can appear to each other and create a politics. What is to appear? It is first to claim the right to exist, to own one’s body, as campaigns from antislavery to reproductive rights have insisted, and are now being taken forward by debates over gender and sexual identity. To appear is to matter, in the sense of Black Lives Matter, to be grievable, to be a person that counts for something. (17–18, italics added)

The audiovisual body is not embodiment itself. It does not fully capture the body, or fully deliver it to the archive, any more than writing does.Footnote8 On the other hand, if audiovisuality involves “signs,” these are not the same kinds of signs as words. Audiovisual traces carry embodiment and identity, as well as histories of care and suffering, invisibility and “fabulousness,” in ways that are fundamentally different from writing. Consider, as a further example, how José Esteban Muñoz analyzes “disidentification” in the case of Pedro Zamora, a participant in MTV’s television show The Real World. As Muñoz explains, Zamora was selected for the show for reasons having little to do with his own life and politics and “his agency in this selection process was none” (152). Nevertheless, Muñoz finds in Zamora’s audiovisual appearance the traces of “a Foucauldian ethics of the self” that intervened in the space of appearance, taking “a leap into the social” and bringing to a mass audience moments of queer Latinx intimacy and celebration “like none that was then or now imaginable on television” (143, 153, 157). The site of these audiovisual interventions was highly restricted and determined by MTV’s editorial control – which, not coincidentally, included a version of the “as” formulation in which MTV framed the audiovisual appearance of cast members with stock identity accounts like “a Jewish cartoonist from Long Island” or “a Republican Mexican-American from Arizona who is applying to graduate school” (155). Yet what comes through in Muñoz’s account is the complexity and instability of Zamora’s audiovisual appearance. It can neither be said that MTV’s editorial power was definitive, nor that Zamora’s authenticity shone irrepressibly through. Instead, Zamora’s appearance emerged from a series of negotiations in which the compositional framing of his audiovisual body was precisely at stake.Footnote9

To clarify this point, we might also note the extent to which Judith Butler’s meditations on “giving an account of oneself” are shaped by the assumption that such accounts will be only or primarily textual. As in her earlier work on gender, Butler is concerned to postulate “a subject who is not self-grounding, that is, whose conditions of emergence can never fully be accounted for” (Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself 19). Drawing on Adriana Cavarero, she contrasts the way that selves may be “exposed, visible, seen, existing in a bodily way” as a “singularity,” a “being constituted bodily in the public sphere,” with “the problem of giving an account of oneself” (33, 35). Because the relation of the self to language is always incomplete and at least partly unchosen, “the account of myself that I give in discourse never fully expresses or carries this living self” and the stories or narratives that I tell about myself “do not capture the body to which they refer” (36, 38). Although Butler gestures towards a concept of “articulation” that includes “various modes of expression and communication, some of them narrative and some not” (58), the only sites in which the limitations of language are radically exceeded seem to be those of actual lived encounter: either literally in public, as at a political protest, or in the psychoanalytic scene of transference. Missing from Butler’s juxtaposition of language/discourse and embodiment is the triangulation enacted by audiovisual modes of articulation, in which the visual and audible singularity of the body may enter the space of appearance in a strikingly non-narrative way.

For Butler,

if we require that someone be able to tell in story form the reasons why his or her life has taken the path it has, that is, to be a coherent autobiographer, we may be preferring the seamlessness of the story to something we might tentatively call the truth of the person, a truth that, to a certain degree, […] might well become more clear in moments of interruption, stoppage, open-endedness – in enigmatic articulations that cannot easily be translated into narrative form. (64)

If our public identifications now more often than not incorporate audiovisual modes of appearance alongside textual ones – from the photo beside an author’s bio to the critical juxtapositions of word and image that Mirzoeff analyzes – this is not always done with the aim of more completely or authentically accounting for ourselves, rendering ourselves coherent, or convincingly narrating our trajectories. On the contrary, as I began to suggest in the previous section, the juxtaposition of text and video can be implemented in other ways, some of which might allow more “enigmatic articulations” to emerge, which might better correspond to “something we might tentatively call the truth.” As Mel Y. Chen writes in Trap Door, the shift from television and cinema to social media posts and streaming video requires “moving beyond thinking merely in terms of spectacle or visibility, and thinking more intensively about the kinds of presence that may be carved out in a given medium” (Gossett et al. 149). Also invoking the question of form, Laura Horak asks: “How do the parameters of YouTube affect the form and content of trans vlogs? What strategies do vloggers use to make their felt gender legible to viewers?” (Horak 572). Taking care to note that YouTube is hardly a utopian space, Horak points to the specific strategies involved in “attempts to use audiovisual and network technologies to grapple with the gaps between the felt body and the body as seen and heard by others” (582). Through techniques of montage and the placement of “on-screen text to frame” audiovisually evidenced processes (579), video blogs or vlogs can “position trans youth as experts, implicitly contesting the expertise over trans bodies claimed by medical professionals, educators, and parents” (574–75). Here again, it is the juxtaposition of spoken and written textuality with audiovisuality that affords new modes of articulation, in which more or less vulnerable individuals and communities can speak not only for but also through, around, about, and from themselves.

There is a vast archive of film and television media across which such aesthetic and political interventions can be analyzed. Katariina Kyrölä argues, for example, that the music videos of Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé should be approached “not only as provocations for thought, or objects to which theories can be applied, but as thought and theory themselves” (Kyrölä). Recent long-form audiovisual music video works like Beyoncé’s “visual album” Lemonade and Janelle Monáe’s “emotion picture” Dirty Computer would seem to further this claim. Their audiovisual dramaturgies build on a longer history and context of narrative hip-hop and Afro-futurist sound (Eshun), which finds a new institutional leverage point in Carson’s PhD dissertation album. In approaching these works, we are strongly compelled to hear Tinsley’s instruction, “Read this book like a song,” alongside another: Hear this song like a book. And with such works in mind, we might even be tempted to suppose that a queer prophetic mode of articulation is already ubiquitous, structuring the public sphere and spaces of appearance in ways that academia is only beginning to comprehend. Yet the limitations of commercial media production, to which Muñoz points, remain entrenched. I return then finally to the queer prophetic, as a mode of articulation that has not yet fully arrived.

4. Queer prophecy

“The prophetic,” writes Mark Ellis, “is an action. It is also a performance” (Ellis 16–17). The fragmentation and recomposition of embodiment in works that combine textual and audiovisual elements cannot be grasped within received understandings either of research or of artmaking. I therefore propose that what we are witnessing in the imbrication of audiovisuality and textuality is the potential for another mode of articulation, in which fundamental principles of authorship, identity, and knowledge may be reconfigured and reinvented. I call this mode prophetic because of how it pushes at the limits of intelligibility, appearing in forms that might at first seem to be merely additive combinations, but which on deeper inspection reveal substances and possibilities that have never previously existed. To call this “transmedia” would be to refer only to the integration of technological platforms and not to the ethical and political potentials that may appear through that integration (unless we intend a slippage to “trans/media”). Perhaps multimedia and transmedia are what happens when the prophetic potentialities of these technologies are contained within systems of alienated production and oriented toward the experience of a “user” or “consumer.” In contrast, I call prophetic the power of imbricated textuality and audiovisuality to work in the service of embodiment, through roles and functions like “artistic researcher” or “scholar-practitioner,” which attempt to avoid consolidating the individual as critic, as artist, or as consumer. And this is perhaps also why I have not explicitly referenced audiovisuality in the title of this article (as one reviewer suggested): I want to resist the instrumental uptake of audiovisuality without its attendant queerness. I want to mark the thrill of the audiovisual, as a medium of artistic research, with a warning, recalling and recentering its relation to embodiment: My proposal here refers not simply to the audiovisual medium but to its specific capacities for queer prophecy.

My concept of prophecy draws on Ellis’s idea of the prophetic as a “call for justice,” a disturbance of the peace, and “never a theoretical construct,” which demands a reckoning with history and cuts through illusions of empire and progress (114–19). It also draws on Cornel West’s invocation of “the Jewish and Christian tradition of prophets who brought urgent and compassionate critique to bear on the evils of their day,” a sense of the prophetic that “neither requires a religious foundation nor entails a religious perspective” (171). The prophetic in this sense is always political, but it can never be merely a statement of existing political will, any more than it can be a voice for established religion. The prophetic cuts into the space of appearance using partly-intelligible forms that performatively reinvent what is possible there.Footnote10 For thinkers who understand political appearance as a kind of speech act, these forms might involve new verbal identifications and narratives of the self, including new identities “as” which to speak. A queer prophetic, on the other hand, is more likely to articulate itself through multimedial and transmedial forms, where textual claims and identifications are simultaneously illustrated and contested by forms of audiovisual appearance. LeVan anticipates such a complex relation between elements, when he describes a multimedia performance in which “words encroach upon the visual space like pharmakon, at once remedy and poison” (214). Writing about and from the “position of scholar-artist,” Dorinne Kondo invokes the potential combination of “dramaturgical critique” and “reparative creativity” in new forms of work (Kondo 233, 132). I would further link this prophetic potentiality to what theorists of performance, literature, and cinema have recently evoked through expanded critical concepts of “speculation” (Rifkin), “fabulation” (Nyong’o), and “shimmering” (Steinbock).

I suggested above that the queer prophetic potential of artistic research cannot be realized unless it undertakes a fundamental grappling with the whiteness and heteropatriarchy of the institutions that support and fund it, as well as with its own constitution. This is simultaneously a political and an epistemological requirement, insofar as feminist and queer of color and Black and Indigenous theories and techniques of audiovisuality are often far advanced, both formally and ethically, beyond those that circulate within the disciplines of institutionally unmarked (white) artmaking. The difference between textual appearances and audiovisual appearances has major implications for what counts as knowledge, as well as who can be recognized as an expert, and this has everything to do with the structure and future of academic institutions. There are connections still be to be recognized between logocentrism, whiteness, and the projects of extractive and colonial disembodiment that have brought our world(s) to the brink of ecological collapse. There are strategies to unmake the structures of academia that radically decenter the textual, without losing its critical powers, in solidarity with broader decolonizing movements. The way in which these connections and strategies develop likely depends both on the social and political reshaping of academic institutions and on the generation of concrete new forms. Artistic research can contribute directly at least to the latter, by working to queer institutional bodies and at the same time to open doors (rather than traps) through which excluded individuals and communities might pass. Again, I return to a practical question: What forms might these transformations take?

Historically, within performance studies, two dominant modes of appearance and articulation have been assumed: the mode of textual discourse and the mode of what we have called “performance.” If the queer prophetic today is neither of these, then we may need not only to invent new forms for it, but also to question the substance and relation of those dominant modes. In a queer prophetic mode, we do not speak directly from our body to a public. We do not literally, physically appear. Yet neither do we articulate a purely textual self, a verbal self, a self defined by those aspects of speech that can be captured in words. No, this is a third relation to embodiment, a queer one: I am there, but I am not there. My audiovisual body is my body, but it is not my body. I know it is not my “real” body because I can cut it, splice it, delete it, distort it, and I do not feel pain. I can make unlimited copies of this body. If it is part of me, it is on the edges of my embodiment, like hair or nails, but even more detachable. If you privately delete a copy of my audiovisual body, I will not even notice. Once those copies go out, they are no longer part of me. Yet these bodies do not operate like textual bodies, either. It is not as easy to quote my audiovisual body out of context. You can steal it, but you cannot (yet) make it do whatever you want. Its mode of being is different. The whole semiotic point about the arbitrary relation between signifier and signified pertains – and, in fact, defines – language. What are the semiotics of representation when the body appears in multiple forms, both textually and audiovisually?

I am talking here about the audiovisual body, but a completely reinvented one: Not the body as it appears in film and television, but as it might appear in new forms of work built on different relations of production and criticality. My own investigation of the embodiment-textuality-audiovisuality triad coincided with a project, mentioned above, which set out to investigate Jewishness and ended up foregrounding whiteness also. At the same time, I finally abandoned the lifelong burden of speaking “as” a man and allowed myself to identify as nonbinary in the field of gender. We could then add a further point to the comparison I made above, between two video works: In “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions,” my need to explain and legitimate the transmission of embodied technique arose from a body that was still calling itself a man. By the time of “Diaspora,” the disaggregation of epistemic powers and the surrender to a complex experimental milieu, as well as my desire to reframe certain messy audiovisual traces under the sign of kinship and diaspora, existed alongside new relationships to my own gender and racial identities. These transitions are not identical or equivalent – nor are they yet finished – but neither are they entirely separate. Did the experience of sitting down to edit and compose my audiovisual body allow me to recognize my visible and invisible identities in another way? On the contrary, I think it was my shifting understanding of embodiment and identity that eventually gave me the idea to pick up the video camera – long rejected by many body-focused theatre-makers as a pedestrian tool of intrinsically incomplete documentation – and wield it in a different way.

Acknowledging this connection makes me think of “punk theologian” Michael Dudeck, whose “queer reading of religion” has led them to invent a new religion out of fragments of sacred, popular, and queer sources. Observing that “virtually every depiction of Jesus being crucified can be understood as an ancestor of performance documentation” (“The Religion Virus” 13), Dudeck’s “new, queer performative iconographies” draw as much on science fiction and modern cults as on their own Jewish upbringing (18, 12–16). While not identifying as trans, Dudeck’s performances invoke forms of multispecies or alien drag, as when they perform “painted white, wearing headdresses and multiple prosthetic breasts” or chanting in an invented language (23). Like me, Dudeck gravitates towards the “illuminated manuscript as a possible hybrid that could contain both image and word,” integrating “priestly reflection and prophetic frenzy” within a single work (22). I also think of Tobaron Waxman, a “visual artist who sings” and someone who rearticulates both gender and religion through a range of media including photography, video, installation, and performance. Waxman is a trained cantor, or Jewish liturgical singer, whose work as a “gender diasporist” integrates trans and Jewish identifications in nuanced ways. Responding to the trap of visibility, Waxman notes: The “expectation that I should make a picture of my body is, I feel, limiting in a potentially transphobic way.” Yet since 2012, a series of “new performance projects involve bringing my own body back into the work” (Johnson 614, 618). It seems right to acknowledge that, to a degree, we each speak “as” a white Jewish man. Yet so much is left out by those words, including much that comes through, not in a naïve authenticity of the audiovisual, but in the complex engagements and interpenetrations of audiovisualities and textualities.

What is clear in the range of examples I have considered is that negotiations of gender, sexuality, race, and other embodied and more or less visible identities play out in specific ways as affordances of the audiovisual body, contesting a space of appearance that is no longer only or even primarily textual. While in no sense equivalent to lived embodiment, the audiovisual body brings appearance, exposure, singularity, and vulnerability into discourse in ways that are not yet fully understood and which, because they will never be directly translatable into logocentric forms of thought, may with some justification be called both queer and prophetic. Inventing the queer prophetic is a matter of how the body appears in the work, where “the work” refers to whichever fragments of performance and document make it into the space of appearance. The term “audiovisual body” is intended to capture the paradox of these new forms, which are in a sense merely signs, circulating independently of living bodies just like written documents, and yet also unmistakably bodies – as we recognize whenever we see and hear “ourselves” onscreen. Without reducing either artistic research or the queer prophetic to a utopian fantasy, I want to propose that, in different ways, both of these concepts can help us to imagine a world in which the differential vulnerability of bodies is not only declared and analyzed but also demonstrated and contested, in forms that circulate across the boundaries of artistic, academic, and activist fields of action.

Dare we imagine an institution that recognizes the appearance of queer prophecy in the public sphere as an epistemic act, an act of knowledge and expertise, which requires the support not of one-time grants or fundraising drives but of ongoing ecologies of teaching and research? Dare we imagine the dismantling of whiteness, the decolonization of history, and the rendering of justice as the founding principles of a research culture in which audiovisual bodies are treated not as signs to be manipulated but as points of entanglement through which ethical and political responsibilities accrue? It seems to me that such imaginings suggest nothing less than a different concept of embodiment, that is, a different concept of life. If the mind/body split is indeed an artifact of the technology of writing, then “thought,” “knowledge,” and “reason” are debased whenever they are used as synonyms for that which can be written. The onto-epistemological significance of audiovisuality is therefore not only to displace “mind” from its position of dominance over “body,” but also to afford entirely different ways of making embodiment public. I do not believe we can yet imagine the range of documents, let alone the institutions, that such alternative ways of thinking might generate. For now, the best terms I can find to name them are those that combine the archaic and the novel, the lived and the appearing: artistic research and the queer prophetic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term “cut” here is adapted from Karen Barad. For my theory of experimental and laboratorial research as defined by “two cuts,” see Spatz, Making a Laboratory.

2 For a detailed analysis of the Journal of Artistic Research, including its origins, institutional strategies, epistemological framework, assessment criteria, and unique web-based form, see Chapter 11 in Borgdorff (Citation2012).

3 As of February 2021, JER has published 14 peer-reviewed video articles, including 3 composite articles, each comprising 5 separate video essays, as part of a special issue (3.2) on embodiment and social distancing. JER is published by Open Library of Humanities and has an interdisciplinary editorial advisory board.

4 Prior to 2015, I used video only in the mode of performance documentation, even if I sometimes found that a video “trailer” for a performance better captured its intentions than the live event. In 2014, I took up my first full-time academic position, moving from the U.S. to the U.K. and encountering for the first time a context in which the question of how to publish “practice as research” scholarship was seriously debated.

5 “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions” and most of the other videos discussed below are available from the Urban Research Theater website <http://urbanresearchtheater.com/>, as well as in other contexts as cited. On the physical training shown in this video, see also Spatz, “Massimiliano Balduzzi.”

6 For a detailed analysis of the method see Spatz, Making a Laboratory. The following point-by-point comparison is adapted from an earlier short text that compared a three-minute video called “dynamic rhythms” with a one-minute video called “laboratory”; see <http://urbanresearchtheater.com/2017/09/22/laboratory/>.

7 For a simple explanation and breakdown of the idea and implementation of illuminated video, see “ancestors: an illuminated video,” in International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media (forthcoming).

8 An anonymous peer reviewer found my claim that the “audiovisual body is not embodiment itself” to be “contentious.” In the context of this article, it should be clear that equating the audiovisual body with the living body would require also equating the written or textual body with both of those, so that the tripartite relationship I am analyzing – between embodiment, textuality, and audiovisuality – would simply collapse.

9 A similar point has been argued through many iterations of discussion around the film Paris is Burning (Butler, Bodies That Matter; Bailey; Moore). Ultimately, we can ignore neither the real power of the appearance of individuals like Venus Xtravanganza, nor the economic and editorial control over those appearances by filmmaker Jennie Livingston. At stake here are the core power relations structuring audiovisual appearance.

10 Karen Gonzalez Rice has studied the link between prophecy and performance art, arguing that “strategies of endurance art in the United States participate in deep traditions of American prophetic religious discourse” (Rice 5).

Works Cited

- Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017.

- Allegue, Ludivine, et al., eds. Practice-as-Research in Performance and Screen. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony. “Go Ahead, Speak for Yourself.” New York Times Aug. 2018. <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/10/opinion/sunday/speak-for-yourself.html>.

- Arlander, Annette. “The Shore Revisited.” Journal of Embodied Research 1.1 (2018): 4. doi: 10.16995/jer.8

- Arlander, Annette, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz, eds. Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact. Routledge, 2017.

- Artistic Doctorates in Europe. Experiences and Perceptions of the Artistic Doctorate in Dance and Performance. 2017. <https://www.artisticdoctorates.com/>.

- Assis, Paulo de. Logic of Experimentation: Rethinking Music Performance through Artistic Research. Leuven UP, 2018.

- Bailey, Marlon M. Butch Queens up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit. U of Michigan P, 2013.

- Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke UP, 2007.

- Blackston, Dylan McCarthy. “Writing the Body.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1.4 (2014): 627–32. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2815147

- Borgdorff, Henk. The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden UP, 2012.

- Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke UP, 2015.

- Browne, Kath, and Catherine J. Nash, eds. Queer Methods and Methodologies: Intersecting Queer Theories and Social Science Research. Ashgate, 2012.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. Routledge, 1993.

- Butler, Judith. Giving an Account of Oneself. Fordham UP, 2005.

- Campbell, Alyson, and Stephen Farrier. “Queer Practice as Research: A Fabulously Messy Business.” Theatre Research International 40.1 (2015): 83–87. doi: 10.1017/S0307883314000601. doi: 10.1017/S0307883314000601

- Carson, A. D. “Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions.” PhD diss. Clemson U, 2017. <https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1885/>.

- Catanese, Brandi Wilkins. The Problem of the Color[Blind]: Racial Transgression and the Politics of Black Performance. U of Michigan P, 2014.

- Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1.4 (1976): 875–93. doi: 10.1086/493306

- Dudeck, Michael. “The Religion Virus.” Ecumenica 11.1 (2018): 6–28.

- Ellis, Marc H. Future of the Prophetic: Israel’s Ancient Wisdom Re-Presented. Fortress P, 2014.

- Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. Quartet Books, 1998.

- Gatt, Caroline. The Voices of the Pages. Knowing From the Inside. U of Aberdeen, 2017.

- Gossett, Reina, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility. MIT P, 2017.

- Gros, Nilüfer Ovalıoğlu. “Carrying the Nest: (Re)Writing History Through Embodied Research.” Journal of Embodied Research 2.1 (2019): 3. doi: 10.16995/jer.23

- Haber, Benjamin. “The Queer Ontology of Digital Method.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 44.3–4 (2016): 150–69. doi: 10.1353/wsq.2016.0040

- Hann, Rachel. “Interview with Rachel Hann.” JAWS: Journal of Arts Writing by Students 5.1 (2019): 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaws.5.1.5_1

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

- Harding, Sandra G., ed. The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader. Duke UP, 2011.

- Harris, Anne M. Video as Method. Oxford UP, 2016.

- Heinrich, Falk, and Thomas Wolsing. “To Be a Work Means to Set Up a World: Into the Woods with Heidegger.” Journal of Embodied Research 2.1 (2019): 1.

- Horak, Laura. “Trans on YouTube: Intimacy, Visibility, Temporality.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1.4 (2014): 572–85. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2815255. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2815255

- Johnson, Dominic. “Voice, Performance, and Border Crossings: An Interview with Tobaron Waxman.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1.4 (2014): 614–19. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2815129

- Jones, Amelia. Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject. Routledge, 2006.

- Kondo, Dorinne K. Worldmaking: Race, Performance, and the Work of Creativity. Duke UP, 2018.

- Kramer, Paula, and Stephanie Misa. “Artistic Research as a Tool of Critique.” Nivel – Artistic Research in the Performing Arts 10 (2019). < https://nivel.teak.fi/adie/artistic-research-as-a-tool-of-critique/>.

- Kyrölä, Katariina. “Music Videos as Black Feminist Thought: From Nicki Minaj’s ‘Anaconda’ to Beyoncé’s ‘Formation’.” Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics 1.1 (2017): 08. doi: 10.20897/femenc.201708. doi: 10.20897/femenc.201708

- Law, John. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge, 2004.

- LeVan, Michael. “The Digital Shoals: On Becoming and Sensation in Performance.” Text and Performance Quarterly 32.3 (2012): 209–19. doi: 10.1080/10462937.2012.691327

- Loveless, Natalie. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Duke UP, 2019.

- MacDonald, Shauna M., and Vassiliki Riga. “Mapping Performance Studies in US Universities.” Text and Performance Quarterly 40.1 (2020): 72–89. doi: 10.1080/10462937.2019.1655165

- Manning, Erin, and Brian Massumi. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. U of Minnesota P, 2014.

- Maoilearca, Laura Cull Ó. “From the Philosophy of Theatre to Performance Philosophy: Laruelle, Badiou and the Equality of Thought.” Labyrinth 19.2 (2017): 102–20. doi: 10.25180/lj.v19i2.97. doi: 10.25180/lj.v19i2.97

- Miller, Nancy K. Getting Personal: Feminist Occasions and Other Autobiographical Acts. Routledge, 1991.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Appearance of Black Lives Matter. Name Publications, 2017. <https://namepublications.org/item/2017/the-appearance-of-black-lives-matter/>.

- Moore, Madison. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. Yale UP, 2018.

- Nelson, Robin. Practice as Research in the Arts – Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Nyong’o, Tavia. Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life. NYU Press, 2019.

- Papazian, Elizabeth, and Caroline Eades. The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia. Columbia UP, 2016.

- Patterson, G. “Entertaining a Healthy Cispicion of the Ally Industrial Complex in Transgender Studies.” Women & Language 41.1 (2018): 146–51.

- Preciado, Beatriz. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Feminist P at CUNY, 2013.

- Rice, Karen Gonzalez. Long Suffering: American Endurance Art as Prophetic Witness. U of Michigan P, 2016.

- Rifkin, Mark. Fictions of Land and Flesh: Blackness, Indigeneity, Speculation. Duke UP, 2019.

- Rouch, Jean. Ciné-Ethnography. Ed. Steven Feld. U of Minnesota P, 2003.

- Schneider, Rebecca. The Explicit Body in Performance. Routledge, 1997.

- Schwartz, Oscar. “You Thought Fake News Was Bad? Deep Fakes Are Where Truth Goes to Die.” Guardian Nov. 2018. <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/nov/12/deep-fakes-fake-news-truth>.

- Shaffer, Tracy Stephenson. “The Place of Performance in Performance Studies.” Text and Performance Quarterly 401.1 (2020): 49–71. doi: 10.1080/10462937.2020.1709742

- Spatz, Ben. “Sequence of Four Exercise-Actions.” Video Essay, 2015. <https://urbanresearchtheater.com/2015/08/12/training-with-a-sequence-of-exercise-actions/>.

- Spatz, Ben. What a Body Can Do: Technique as Knowledge, Practice as Research. Routledge, 2015.

- Spatz, Ben. “Molecular Identities: Digital Archives and Decolonial Judaism in a Laboratory of Song.” Performance Research 24.1 (2019): 66–79. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2019.1593724

- Spatz, Ben. Blue Sky Body: Thresholds for Embodied Research. Routledge, 2020.

- Spatz, Ben. Making a Laboratory: Dynamic Configurations with Transversal Video. Punctum Books, 2020.

- Spatz, Ben, Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Caroline Gatt, and Agnieszka Mendel. “He Almost Forgets That There is a Maker of the World.” Journal of Embodied Research (forthcoming).

- Spatz, Ben, Nazlıhan Eda Erçin, Agnieszka Mendel, and Elaine Spatz-Rabinowitz. “Diaspora (An Illuminated Video Essay).” Global Performance Studies 2.1 (2018): 30 minutes.

- Spatz, Ben. “Massimiliano Balduzzi: Research in Physical Training for Performers.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 5.3 (Sept. 2014): 270–90. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2014.930356. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2014.930356

- Steinbock, Eliza. Shimmering Images: Trans Cinema, Embodiment, and the Aesthetics of Change. Duke UP, 2019.

- Stoller, Paul. Sensuous Scholarship. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

- Stryker, Susan, and Stephen Whittle, eds. The Transgender Studies Reader. Routledge, 2006.

- Taylor, Lucien. Visualizing Theory: Selected Essays from V.A.R., 1990–1994. Routledge, 2014. doi: 10.4324/9781315021614

- Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha. Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders. Duke UP, 2018.

- Vannini, Phillip, ed. Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. Routledge, 2015.

- Wacquant, Loïc. Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. Oxford UP, 2006.

- West, Cornel. The Cornel West Reader. Basic Civitas Books, 1999.