Abstract

This essay explores the co-construction of urban health and blight through architectural representation during urban renewal, exploring how buildings symbolically stood for social and epidemiological diagnoses, producing racial othering through depictions of space. Analysis of photographs, building surveys, real estate appraisals, maps, reports, and advertisements preceding urban renewal in Charlottesville, Virginia, reveals a racialized gaze that constructed problematic associations of whiteness with health and Blackness with blight. We argue that racialized image-making practices perpetuated inequities that urban renewal policy purported to reconcile while masking the true generating dynamics of white neglect and wealth extraction.

Keywords:

Whether through the construction of monuments, racially coded public amenities, or residential segregation and differential infrastructure provision, the creation of architectural space has long been implicated in the rhetorical othering of Black people in the US. Designers and planners have played central roles in crafting images that produce the stereotypes associated with racially coded space in the public imagination. One such example is the Harland Bartholomew & Associates (HBA) 1959 master plan for the City of Charlottesville, a small city in Central Virginia, a master plan that outlined the application of urban renewal in this city. As was typical for the firm’s work in many cities across the country,1 HBA’s master plan relied on earlier studies of urban conditions and provided a conceptual frame for later architectural explorations that led to development of Charlottesville’s Downtown Mall.2 These documents present a sweeping proposal for reordering the city to create a bright, prosperous, and orderly future, with new business areas, transportation improvements, and expansion of parks and other public facilities. But this image is constructed in contrast to another: representations depicting Black3 Charlottesville neighborhoods as blighted places, marked by social ills and deserving erasure. These two constructions—speculative future and diagnostic interpretation of the present—are deeply linked and must be understood as a single project to contrast and construct images of white and Black people and places. In the case of Charlottesville and HBA, the urban renewal project project depended on deeply racist assumptions, producing equally racist outcomes. Integral to these assumptions and outcomes were the mobilization of architectural language, using materiality and selective depiction of building conditions as proxies for judgments about people and whether they belonged.

This essay explores the role that representations of the built environment played prior to and during urban renewal in Charlottesville, revealing how buildings came to signify particular racial logics of health and blight. These images demonstrate the deeply intertwined conceptions of race, space, and health that remain integral to the language of planning and design practice to this day. Visual media play an important role among professional planners and designers, who use and produce discursive objects to orient and frame their activities.4 These practitioners employ an array of visual-rhetorical strategies, including maps, images, charts, and data crafted to mask racial othering behind a screen of rationality.5 In the case of Charlottesville’s urban renewal, these moves served to naturalize racialized conclusions and actions in terms of city planning.

Charlottesville is a site of pronounced racial-spatial segregation to this day, alongside the major cities that are often the focus of pioneering historical scholarship.6 Because it was not subject to typical regulatory mechanisms known to segregate, such as redlining, Charlottesville is an ideal place to examine how visual representation and narrative construction impact racialized decision-making in city planning. HBA is widely known in the US as one of the prime architects of urban renewal policy and the federal highway program, and was influential in developing the methods of comprehensive planning.7 In the mid-1950s, Charlottesville authorities hired HBA to outline the application of urban renewal in the city. This examination of HBA’s work in Charlottesville provides a window into how narratives about race developed over time and provided the rhetorical resonance to urban renewal policy as municipalities implemented it across the nation.

The sections that follow explore the constructions of race, space, and health, as evidenced in both visual representation and spatial action, through the case of Charlottesville’s urban renewal. First, we develop a framework for articulating motives for both the construction of racial otherness and the use of architectural representation and urban spatial intervention as racial tools. Next, we turn to the history of urban planning, architectural regulation, and urban land economics in the US as key disciplinary contributors to racializing narratives about race, health, and space, using the formation of urban Charlottesville as a specific example. We trace the development of these stories and their confluence in the mystifying language of “blight” and urban renewal policy, both nationally and locally. We then extend this investigation to a particular moment when representations of space had real racialized consequences, through a closer examination of urban renewal policy implementation in Charlottesville in the 1950s and 1960s. Our study responds to recent calls from planning and design scholars to examine whiteness and privilege in planning discourse.8 We turn the gaze from communities construed as blighted to the underlying economic dynamics, policy decisions, and representational devices that produced the twinned images of “health” and “blight,” “white” and “Black.” These mechanisms, enacted by multiple players in the processes of articulating and producing a segregated and “renewed” city, implicate ongoing practices of building and neighborhood evaluation.

Racial Capitalism, Urban Space, and Architectural Representation

Race is a constructed concept rather than a biological fact. Cedric Robinson wrote that racism is integral to modern capitalism, producing a system of racial capitalism that uses the differential valuation of people and spaces to structure the accumulation of wealth for groups constructed as superior.9 Edward Said explored a related idea of racialized othering, observing that categories of privileged Eurocentric whiteness and nonwhite otherness are constructed in opposition to each other through representational discourses.10 Said’s analysis focused on literature, but this kind of analysis can be expanded to visual and spatial representations, as we aim to demonstrate throughout this piece.

In terms of how racism is produced as a form of othering, sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant proposed a theory of racial formation, suggesting that racial meaning is constantly produced, modified over time, and tied to physical and social structures of power. These racial projects organize human bodies, physical spaces, and social structures.11 Urban space is constantly structured and restructured to support racial projects where people are differentially and hierarchically represented and valued to orchestrate economic gain for some at the expense of Others.

Discourses of health, space, and race in American history exemplify a set of racial projects governing the differential allocation of both material and cultural resources across race through both narrative construction and physical city-building. Environmental psychologists provide a useful general analysis of the ties between space, culture, and race. Courtney Bonam, Caitlyn Yantis, and Valerie Jones Taylor proposed a racialized physical space framework.12 They argued that people’s perception of space is influenced by both the spaces they experience and racialized perceptions of that space, leading them to actions that exacerbate racialized inequalities.13 They called for place-based critical histories to disrupt commonsense notions of racialized space that reinforce racial inequities in ongoing and cyclical ways. These histories can disrupt and demystify the highly specific and economically motivated patterns of racial inequity persistent in the US.

This paper examines the larger historical and policy landscape leading up to a specific moment of racialized architectural intervention and planning: the implementation of urban renewal policy in Charlottesville, Virginia. Charlottesville is illustrative of the construction of racialized ideas over time through visual representations of buildings and people in planning and policy documents, and in popular media. We evaluate the co-productive relations between ideas of health, space, and race. Co-production refers to “the proposition that the ways in which we know and represent the world (both nature and society) are inseparable from the ways in which we choose to live in it.”14 This study in particular considers the sociotechnical imaginaries of planners, architects, and other dominant actors in the production of urban space.15 To challenge the legitimacy of this imaginary, especially in its racialized form in Charlottesville, analysis of acts of representation can reveal its contingency, as can comparisons with counter-imaginaries, such as those the community’s Black residents.

Race, Health, Building, and the Establishment of Professional Standards

The design professions are deeply entangled with narratives about race, space, and health that developed in the early US. Understanding these relations requires attention to the emergence of rational science in general and the development of several quasi-medical racial associations.16 Linking concepts of race, environment, and disease is a longstanding practice of Western colonialism and part of the context in which racial formation in the US occurred.17 These discourses linked tropical areas with underdevelopment, laziness, and disease, at the same time picturing peoples who originated in temperate regions—European whites—as intrinsically superior. Carl Zimring looked back to how Thomas Jefferson used agrarianism and ideals of Anglo-Saxon purity to anchor his account of the association of whiteness with cleanliness and purity, on the one hand, and nonwhiteness with dirtiness, waste, and disease on the other hand.18 This hierarchy informed the ongoing categorization of people into a Black/white binary in support of chattel slavery, a schema that would be reinforced and reinvented in the form of scientific racism and postbellum urbanization.

At the same time, the politics of professionalization and credentialization functioned to exclude women and racial minorities from the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, and medicine.19 As a result, architectural and medical discourses largely emerged from founding imaginaries generated by privileged white men. The co-constitution of race through health and space can be traced through this history of urban planning, architecture, and standardization of the built environment.

A project of associating whiteness/health/desirability and Blackness/ill health/undesirability often unfolded through the dual use of spatial representation and spatial intervention. Lesley Naa Norle Lokko tied racial projects to architectural thinking by extending Toni Morrison’s observations on “Africanist” images in Western canonical literature. She argued that traditional architectural representations produce racial hierarchies through a flattened dualism where dark signifies bad, and light signifies good.20 These visual tropes paired with active intervention in real space; K. Ian Grandison also drew on Morrison’s work, arguing that the theme of “Black Bottoms”21 illustrates the pattern of relegation of Black people to physically undesirable lands. Caricatured images of Blackness created by mainstream white-controlled design and health discourses, alongside real and ongoing white spatial control, contributed to recognizable white racial and spatial identities constituted in direct opposition to tropes of Blackness.22

In the physical realm, sanitation and health were major themes in the planning and building regulation of nineteenth-century US cities.23 As cities rapidly industrialized in the 1800s, the public health movement emerged to prompt a “sanitary awakening” that fundamentally altered thinking about cities.24 Cities invested in sewer system innovations and enacted tenement reforms aimed at improving ventilation, fire safety, and other basic public health–oriented design standards. Health and organicist metaphors for cities were major themes in early urban public works projects.25

At the same time, urban space became a container for what George Lipsitz termed racialized spatial imaginaries. Governmental agencies at all levels, dominated at the time by white decisionmakers and guided by a largely white voting populace, produced a collectivized white spatial imaginary “based on exclusivity and augmented exchange value,”26 fueling “the structured advantages that accrue to whites because of past and present discrimination”27 in a system of racial capitalism. Designers and planners often served those in power, operationalizing the white spatial imaginary in ways that segregated spaces and valued white-associated spaces and simultaneously devalued Black-associated spaces.

The mechanisms for the deployment of a white spatial imaginary were manifold, including legal and regulatory mechanisms, the spatial development of urbanizing landscapes, and the development of racializing narratives about people and space. Local governments began adopting zoning as a way to separate industrial and residential uses through an expressed concern for public health, safety, and welfare; however, most early zoning in the US also explicitly codified racial segregation.28 Policymakers used the notion of blight, associated with Blackness and pictured as an urban threat analogous to a communicable disease, as a common fear tactic in racial zoning campaigns. When Baltimore mayor J. Barry Mahool signed one of the first zoning ordinances into law in 1910, he mobilized highly racialized logic for the policy: “blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidents of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority.”29 Soon after, Virginia cities like Richmond and Charlottesville joined in legislating residential racial segregation.30 Although the Supreme Court deemed racial zoning illegal in 1917, the practice continued for many decades through privatized real estate practices.

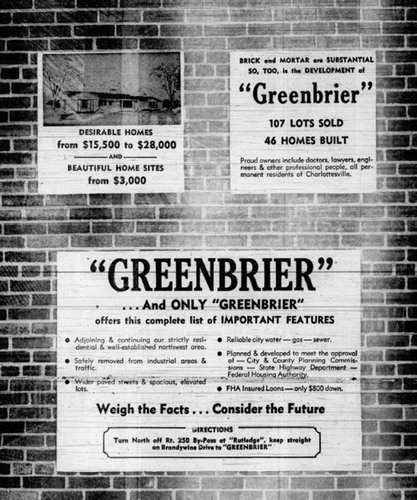

The emerging real estate industry, booming amid increasing suburbanization, shaped racialized associations with space through home marketing and sales practices. Racial covenants and deed restrictions codified racial segregation throughout new neighborhoods across the nation.31 This practice was common in Charlottesville, starting in the late 1800s, and was increasingly prevalent by the 1920s.32 One subdivision advertisement boasted the “proper restrictions to make it the most desirable suburb in the entire south.”33 These advertisements and their accompanying racialized restrictions show that what was being sold, in part, was an idea of exclusive whiteness. This advertisement emphasized reliable utilities, buffering from industrial uses, and an association with brick materiality that connected the whiteness of these spaces with more durable building materials ().34

Figure 1. This advertisement for an upscale subdivision links materiality with subtext that points to a sense of health, safety, and social homogeneity. The Daily Progress, January 9, 1959.

The mobilization of “infiltration theory” by real estate professionals further reinforced the selling power of exclusively white space. This narrative blamed decline in real estate values on “‘infiltration of inharmonious groups,’ real estate code for movement of African Americans to new residential areas.”35 Discourses on infiltration focused on racial change as an imminent threat to real estate values, providing urgency and justification for the systematic exclusion of nonwhite people from many neighborhoods.

By the 1920s, social scientific research and narratives worked in parallel to associate Black people and spaces with ideas of contagious disease and dangerous social “pathologies.” In Charlottesville, these ideas are pointedly demonstrated in a collection of reports by Phelps-Stokes Fund graduate fellows, a philanthropic organization that promulgated a throttled version of Black uplift.36 The fund supported white graduate students and researchers at the University of Virginia in studying the Black population of Charlottesville and surrounding areas. Mapping tactics used in these studies prefigured later mappings by rational planners in documents like HBA reports, which cloaked racial and moral judgments behind the supposedly objective methods of the “City Scientific” approach.37 HBA’s rationalist methodology existed alongside that of other early planners, including Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., Warren Manning, and Arthur Comey, who plotted racial patterns in their urban plans. These kinds of mappings often informally guided investment and development along racial lines, despite explicit racial zoning’s unconstitutionality.38 The causalities suggested in these urban mappings existed within broader patterns of scientific racism circulating during this period, such as Ellsworth Huntington’s deterministic mappings of climate, race, and levels of “civilization.”39

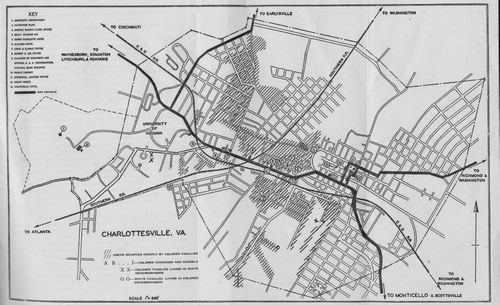

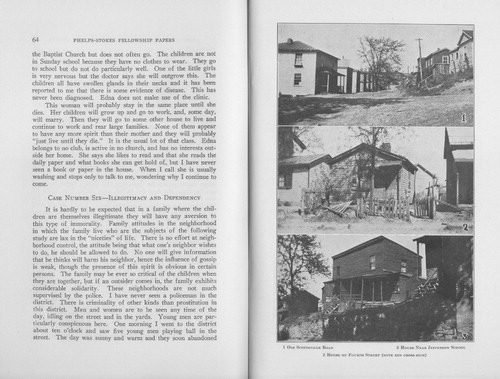

A 1929 Phelps-Stokes-funded report deploys mapping and photography of Black residential areas in Charlottesville () alongside a pathological narrative. This visual convention takes up tropes from epidemiological maps dating back to the earliest cholera maps by London’s John Snow, and late nineteenth-century maps of American cities, showing the origins and spread of contagions from cholera to the 1918 influenza epidemic. These depictions of Black presence as a social contagion conceptually and visually linked tropes of Blackness and disease. The report also aligned photographs of Black residential spaces with written ethnographic vignettes of Black character “cases” that blended moral and medical judgments, evident in titles such as “Feeblemindedness and Illegitimacy” and “Dependency and Blindness” (). These combinations of word and image functioned to produce narratives constructing the otherness of Black social life and space, and to affirm associations of Blackness and unhealthiness or disease. Finally, these reports show the early signs of constructions of space and class that persist. Only the very last of the nine ethnographic vignettes described a “higher class” Black family: “These stories are taken from the real life of one group of these people… . [T]here is another group of Negroes who are very unequally represented here. This group is important in the life of the whole of Negro group of the city but because they are so like ourselves I have not emphasized this class… . There is little of the morbid about the educated class of Negroes. They are just normal people.”40 With this stated omission, the report went on to describe the various “character types” who are of “real interest” to researchers, while for the most part erasing the spatial and social presence of middle-class Black people. Bonam, Yantis, and Taylor noted that white people to this day have difficulty reconciling Black-associated space as affluent or desirable, rendering Black middle-class people and space effectively invisible.41 These tactics of representation and the erasure of the Black middle class would be reused and retooled later in public and official planning documents supporting urban renewal.

Figure 2. This Phelp-Stokes study map of Black communities uses visual conventions common in public health mapping of the period, creating a sense of Blackness as contagion. The map’s emphasis on “out of place” white and Black families further highlights its representation of Black space as Other and naturalizes the idea of segregation as healthy. Marjorie Felice Irwin, (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 1929). (Image in the public domain.)

Figure 3. Pathologizing narratives are paired with selective photography of architectural conditions. Marjorie Felice Irwin, (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 1929). (Image in the public domain.)

By the early twentieth century, urban planners and architects adapted the racialized language of disease to design. The rhetoric of blight as cancer remained central to land use narratives about progress, with highway and civic center projects being posited as the medicine needed to cure the cities ailments from the New Deal era into the postwar era.42 New York City administrator Robert Moses argued that the city was dead and required immediate action instead of “dwell[ing] long on the fact that there’s been an illness in the family.”43 This resulted in the removal of thousands of affordable, mostly Black neighborhoods,44 and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) continued to deny nonwhite families access to home loans in new neighborhoods.45

Nationally, policies aimed at building materials also produced differential and often racialized effects. Many larger cities developed building codes in the early nineteenth century.46 Fire boundaries and building codes dictated material patterns in clusters, aiming to protect the welfare of urban neighborhoods against fire risk. However, these regulations evolved at a product scale, protecting the interests of the building production economy equally or more so than the interests of the broader urban population.47 Wealthier neighborhoods able to afford robust building materials often received the protection of brick or masonry restrictions, while working-class neighborhoods persisted as frame construction outside the fire boundaries.48 Building codes failed to restrict speculative construction of lower-durability structures, instead balancing material affordability with lifespan and durability.49 Wood frame construction is more vulnerable to moisture, lack of heat retention, and other potential health risks.50 When stratified along racial lines, this produced racialized health outcomes.

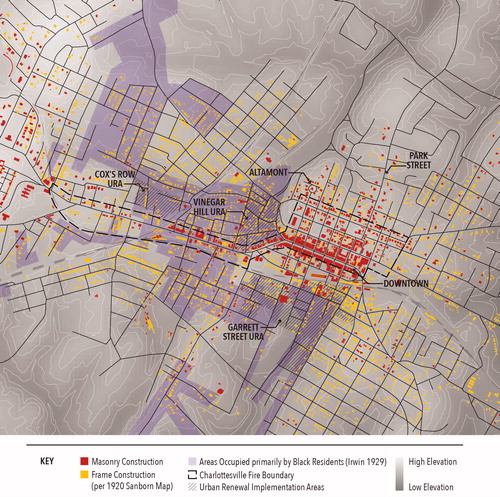

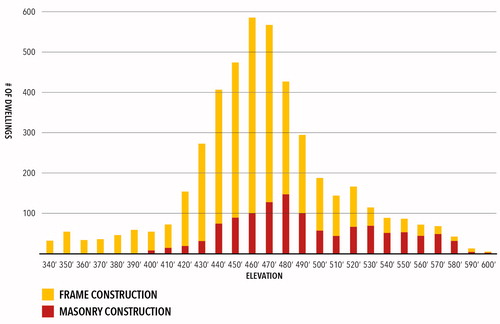

In Charlottesville, stark material distinctions emerged from speculative investment, selective fire limits, and racial covenants with a prevalence of wood frame rental housing in predominantly Black and working class white neighborhoods, often owned by white landlords. In Charlottesville, fire limits codified material stratification across neighborhoods by not only banning wood frame construction in the business district but also extending material protection in the wealthy white residential neighborhoods like Altamont and Park Street north of downtown (). Racial covenants also often restricted neighborhoods as white-only which, combined with other social practices, effectively narrowed housing choices for many Black residents to wood frame construction and material vulnerability. Jeff Ueland and Barney Warf have shown that across Southern cities, Black residents disproportionately live in lower lying areas at higher risk of flooding and other environmental risk factors. This pattern bears out in Charlottesville, where spatial patterns by the late 1920s show Black residents mostly confined to low-lying areas along urban streams in frame houses, while upland sites became associated with high-value white housing ().

Figure 4. The Progressive era urban fabric of Charlottesville generally concentrated Black residential areas in low-lying areas, which were dominated by frame construction. Upland white residential areas, even outside the downtown, were more likely to be brick, and some also received protection through the city’s fire limits, which prohibited wood construction. (Image by authors.)

Figure 5. Analysis of residential structures’ building materials by elevation reveals that more durable materials, like brick, were concentrated in upland white neighborhoods. (Image by authors.)

Analysis of these restrictions and patterns challenges the causality of the “Neighborhood Unit” model of urban form described by Clarence Perry in 1929 and adopted by HBA in their Charlottesville planning work. Perry explicitly tied built form to social value by arguing that urban space reflected the character of the people who live in it: “the character of the district in which a person lives tells something about him. Since he chose it, ordinarily it is an extension of his personality.”53 In the case of Charlottesville, the state of Black neighborhoods reflected white owner neglect and limited buyer options, but narrative constructions like the “scientific” studies produced by the Phelps-Stokes fellows projected the social meaning of these material conditions onto the bodies of Black inhabitants.

Mobilizing Postwar Narratives of Urban Blight: Urban Renewal in Charlottesville

During postwar urban renewal, destruction of Black neighborhoods hinged on designations of blight, which could legitimize and trigger massive clearances of “slum” areas. Blight, though employing an organic metaphor, is an elusive concept that legal and planning scholars have struggled to define.54 This slipperiness is key to the concept’s usefulness, its multiplicity of interpretive registers allowing the concept to provide justifications as needed for those in power. As one legal scholar argued, “the amorphous definition of blight, flawed decision-making, and false narratives, have led to the condemnation of properties in the most vulnerable communities.”55 Blight is better understood as a way of seeing and representing, linking specific articulations of space, race, and health in the service of localized exercises of power. It is a gaze that organizes the world—its people and places—into healthy and unhealthy.

In their oral history of Vinegar Hill, the first Charlottesville neighborhood razed in the 1960s as part of urban renewal, James Saunders and Renae Shackelford offered an alternative view of this period to that of official representations.56 Their text is an important counternarrative that challenges official blanket designations of the neighborhood as a blighted area worthy of destruction. Our essay contributes to that counternarrative by implicating the visualization practices of planners and architects in constructing blight. We also elaborate counternarrative conclusions on the economic motivations behind the decisions to unleash eminent domain on the neighborhood of Vinegar Hill. Finally, our counternarrative project examines planning documents to reveal alternative interpretations that point toward Black care and wealth accumulation between the lines of official documentations of Vinegar Hill.57

Political Context of Postwar Charlottesville

During and after the New Deal, developing housing agencies like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), FHA, US Housing Authority, Public Housing Administration, and Housing Financing Agency all encoded the idea of racial “contagion” into US housing policy.58 Redlining maps, well documented for their role in producing racial segregation,59 were never drawn by HOLC for Charlottesville. But segregated residential patterns emerged by this time nonetheless, and Saunders and Shackleford described Vinegar Hill as both a predominantly Black residential district and the premiere local Black business district in Charlottesville, adjacent to the predominantly white downtown slightly to the east.60

Saunders and Shackelford described the political setting of Charlottesville in the postwar years as one of widespread white backlash and resistance to the racial integration of public facilities precipitated by the Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision of 1954.61 They noted that Jim Crow–era voter suppression laws still shaped a voting population that was overwhelmingly white.62 This setting supported Grandison’s proposition that urban renewal in many ways was an extension of massive resistance at the state level against integration in Virginia. In Charlottesville, actions taken by a disproportionately white voting populace constituted a kind of putative planning or weaponization of local land use policy to disrupt Black wealth accumulation and to displace Black residents.63 The examination of architectural representations below will trace three types of visual narratives used in this effort: persuasive images, diagnostic reports, and comprehensive plans by HBA.

Mobilizing Blight: Persuasive Images, White Voters

The implementation of urban renewal in Charlottesville required the direct consent of voters and elected officials. In Virginia, until the Voting Rights act of 1965, voter suppression mechanisms meant the voting populace of Charlottesville skewed disproportionately white. Voters narrowly approved the establishment of a City Housing Authority in 1954, which allowed the city to hire HBA to begin planning for the redevelopment in 1958. The city and its consultants presented a plan in 1960, and voters narrowly approved another referendum to pursue redevelopment of the Vinegar Hill neighborhood later that same year. This referendum was one of a series conducted in the 1960s, which allowed local citizens to vote on which sites would undergo redevelopment. Sites that could alter racial dynamics in whiter neighborhoods drew outcry and were not approved; sites in the wealthiest white neighborhoods were never even on the ballot, unsurprisingly given that members of that class served as the housing authority’s leadership.64

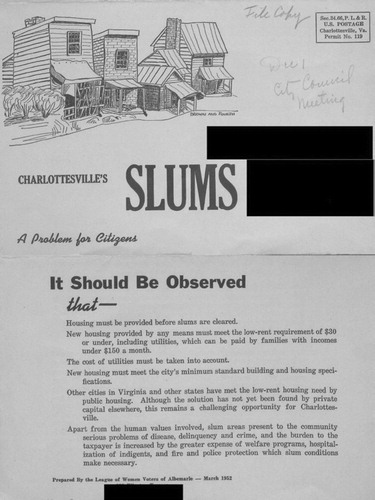

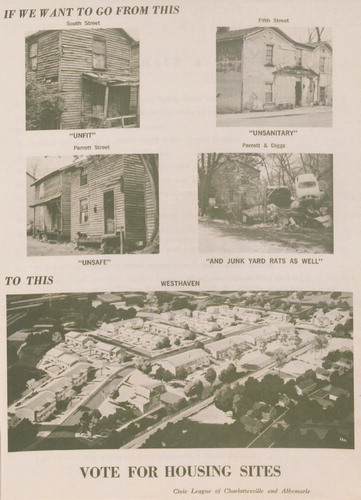

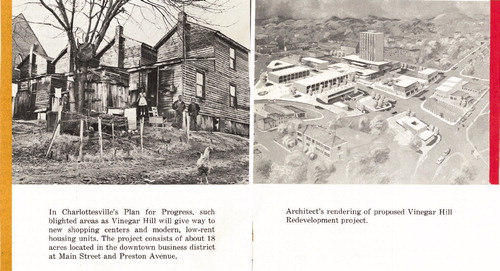

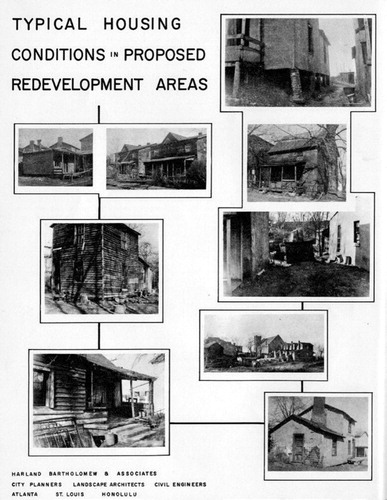

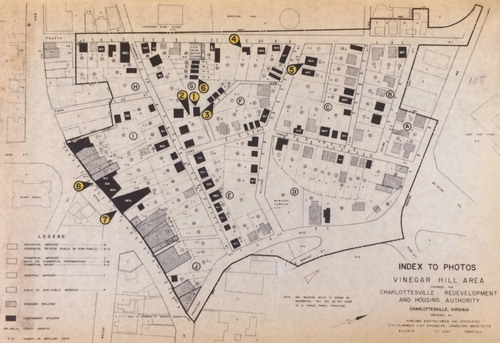

Intensive public relations campaigns accompanied all these “public” decisions, using tactics well rehearsed in the residential real estate advertisements and social scientific reports early in the 1900s. For instance, a League of Women Voters mailer from 1952 urging clearance of slums literally caricatured as “blighted” spaces ().65 Other persuasive materials used photographs to make their case ().66 Scholars have noted that photography is a powerful tool in urban renewal.67 Photographs present a seemingly neutral and objective view of urban space,68 while in fact constructing depictions of racialized “disorder,” using a variety of compositional tactics, such as selectively focusing on back alleys, vacant lots, and abandoned buildings.69 Images were also skewed at a low-angle toward ill-maintained frame construction photographed in winter, creating a sense of barrenness. Animals and children often appeared in ways that pathologized longstanding practices of self-provisioning and implied a lack of “proper” familial supervision ().70 These image tactics were used not only in advertisements but also in reports like the HBA 1959 master plan and in applications for federal urban renewal funding ().71

Figure 6. This sketch was used in advertisements supporting urban renewal. League of Women Voters of Albemarle, “Charlottesville’s Slums: A Problem for Citizens,” 1952. (Uncopyrighted image.)

Figure 7. This advertisement evokes a lack of health and safety to call for clearance, and it juxtaposes those conditions with a rendering of proposed redevelopment, illustrated through an aerial view of white, materially vague structures. Citizens Slum Clearance and Housing Committee. (Uncopyrighted image.)

Figure 8. In this image from a city-published pamphlet, a backyard garden in winter is contrasted with a modernist shopping plaza proposed for the same site. City of Charlottesville, “Report to Our Citizens,” 1964. (Image and its captions in the public domain.)

Figure 9. This collage exaggerates the worst conditions in a portion of the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, and it excludes images of well-kept homes on nearby blocks. HBA, (Atlanta, GA: HBA, Southeastern Office, May 1959). (Image in the public domain.)

Figure 10. This map accompanying the city’s urban renewal application reveals that photographs were selectively used to exaggerate the conditions of Vinegar Hill. HBA, “Final Project Report, Part 1—Application for Loan and Grant, Urban Renewal Project No. VA R-12, Vinegar Hill Project,” June 1960. (Image in the public domain.)

Images of blight were often paired with their opposites in persuasive diptychs, alongside aerial drawings that demonstrated the physical “order” that would be created through clearance and reconstruction (). These renderings served as a visual foil to images of “unhealthy” neighborhoods, reinforcing Lokko’s observations that in spatial discourse, “blackness is absolutely central to the construction of whiteness—ain’t no white without black.”72 The renderings deployed comparisons of existing, materially specific conditions and aerial views of materially generic but bright future structures.

These pairings used numerous visual strategies examined by scholars of racialized architectural representation. Renderings showed large-scale plans conveying a modernist vision for the city in axonometric view. These images functioned in the same way Diane Harris explained midcentury real estate advertising aimed at white potential homeowners: “unrestricted movement, whether of the eye or the body, was implicitly linked to whiteness and class identity, so that axonometric representations not only conveyed aesthetic and architectural modernity but also subtly reinforced racial constructs, as did the very aesthetic of modernity, with its emphasis on cleanliness, spaciousness, and lack of clutter.”73 This omniscient perspective contrasted with the low angles used to photograph existing neighborhoods. Further, the comparisons pictured the existing neighborhoods’ oversaturated blacks and greys, while the proposed “solutions” are rendered in a materially vague white. This move echoes widespread symbolism in modern architectural representation, as Mabel Wilson noted: “white forms represent the core of modernism’s utopian impulse… . [A]rchitecture for a gleaming white metropolis and ideal society depends upon a controlled blackness.”74

Synthesizing Documents: HBA Master Plan and Supporting Reports/Counternarrative Readings

In the 1950s, Charlottesville authorities hired HBA, a relationship that resulted in the first comprehensive plan for Charlottesville in 1959 and later plans and studies into the 1970s. HBA was a particularly influential firm in terms of urban renewal and related policies, such as federal highway construction. Eldridge Lovelace, an early firm partner, wrote in his account of HBA’s influence that Bartholomew was a central figure in the formulation and implementation of urban renewal policy nationally, and much of the firm’s meteoric success after the Great Depression hinged on this “expertise” in implementing these policies.75 Overall, HBA was particularly skilled at combining the visual tactics and narratives produced by a range of professionalized “experts” into implementable plans. These sweeping reports compounded racialized narratives and veiled the specificity of these stories in planning documents that claimed comprehensiveness and scientific objectivity as they simultaneously diagnosed “unhealthy” conditions and proposed policy-based solutions.

Bartholomew was among the planners most central to the legitimization of planning through the crafting of specialized knowledge systems; thus, it should be no surprise that his firm succeeded in crafting a seemingly objective view of Charlottesville’s housing conditions. But careful review of data collection and representation strategies in the years leading up to clearances challenges the firm’s conclusions, revealing patterns that run counter to the causalities framing blight designations.

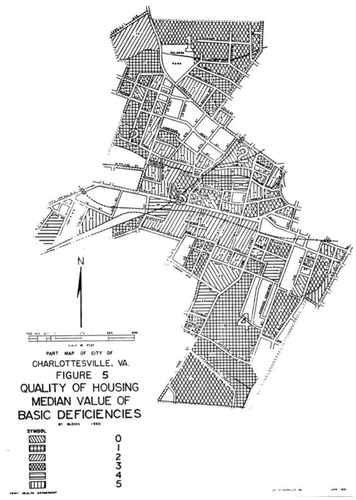

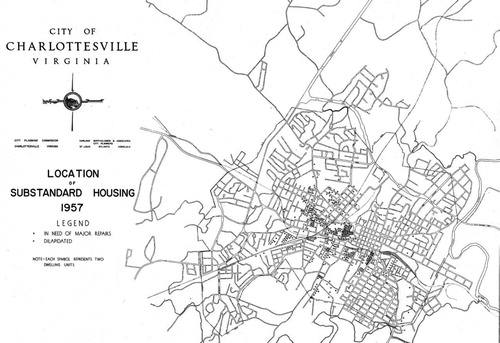

The 1959 master plan and its supporting documents drew on data about substandard housing from sources like the US Census of Housing, the local health department, and HBA’s own staff. A 1951 survey of housing, for instance, exclusively targeted areas associated with Black neighborhoods and included “practically all of the known blighted sections of the city,” a statement revealing that the area’s conditions were a foregone conclusion ().76 A 1957 survey focused on a similar area only evaluated rental units, skewing the data further by omitting owner-occupied buildings from consideration. Although clear rubrics about building materiality were included in supporting survey instruments, some maps identified both “substandard” buildings and those containing “blighting influences,” relying on the nebulous definition of the latter to justify condemnations that would not make sense based on the actual conditions of the property. As these data were translated to the maps that supported the final master plan, they had the effect of treating these clusters as if they were demonstrably far worse than other areas, which were not separated by a survey boundary in the final versions. These maps thus masked the fact that blight was never really considered as relevant to study in white neighborhoods while naturalizing the idea that dubiously identified areas of blight should be slated for redevelopment ().

Figure 11. This survey correlates strongly with Black neighborhoods of Charlottesville, by design. Joint Health Department, “An Appraisal of the Quality of Housing: Charlottesville, Virginia,” 1951. (Image in the public domain.)

Figure 12. Although this map in the 1959 master plan deploys data from the 1951 survey, the survey zone is omitted, implying that other areas are entirely without substandard structures. HBA, (Atlanta, GA: HBA, Southeastern Office, May 1959). (Image in the public domain.)

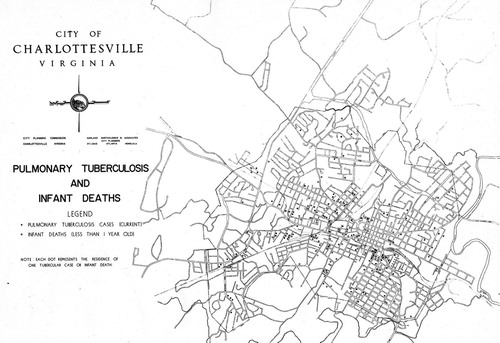

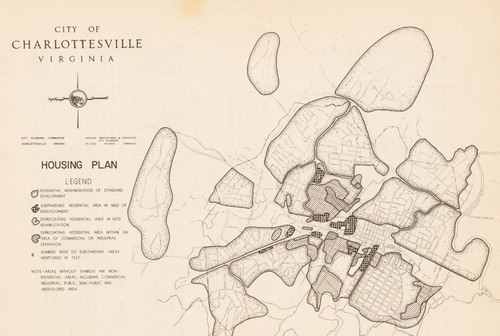

One of HBA’s key tactics was mapping, a type of media well examined by critical scholars.77 In a preliminary report by HBA, a map supporting a discussion of the “Relation of Bad Housing to Public Health, Safety, Welfare and Morals”78 pictured statistics on particular medical conditions: tuberculosis and infant mortality (). Tuberculosis has long been stigmatized and associated with the poor and minorities.79 Interest in infant mortality, likewise, emerges in the context of Progressive era reform movements led by white women and often targeted at Black women.80 This selective use of data contributed to the pathologization of Black people by the creators of these images. This documentation supported prescriptive maps in the final 1959 plan that simultaneously rendered the supposed problem (i.e., substandard housing) and the solution (i.e., wholesale district redevelopment), encasing these skewed datasets in a conclusive and seemingly objective format while deploying the visual trope of Blackness as contagion used in earlier health mappings ().

Figure 13. The medical conditions included in this map reflect racialized constructions of disease. HBA, (Atlanta, GA: HBA, Southeastern Office, May 1957). (Image in the public domain.)

Figure 14. This 1959 “Housing Plan” identifies darkly shaded areas, predominately Black neighborhoods, as “substandard areas in need of redevelopment” to contain blighting influences. HBA, (Atlanta, GA: HBA, Southeastern Office, May 1959). (Image in the public domain.)

These patterns were carried through to implementation and were reflected in property appraisals used to justify condemnation in federal funding applications prepared prior to the purchase of Vinegar Hill and other communities. These property evaluations read across physical improvements, comparable sales, evaluations of maintenance and condition, and other subjective criteria about location. These reports purportedly measured objective, quantitative value, but the appraisers’ comments expose assumptions about health and race that informed them, such as the following: “Owner occupied house in reasonably good condition considering the neighborhood.” “Vacant lot surrounded by worthless houses.” “Old building with colored restaurant operation with a colored apartment over it. Only colored people would venture in this area except during the day.”81 These statements, which range from implicit comments about “the neighborhood” to outright fear, reveal that the extent to which the condition of the neighborhood was understood was a product of who resided there—as suggested by comments about overcrowded and poorly maintained rental properties.

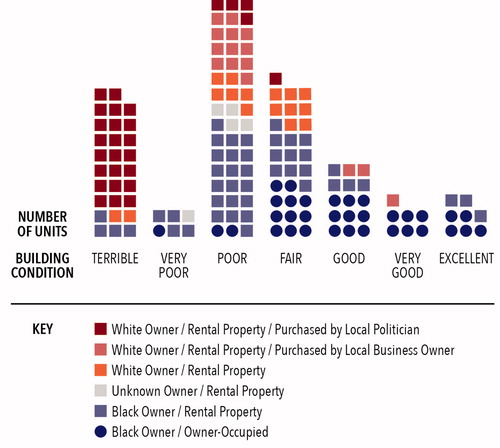

While uncovering the construction of racialization is critical, a rereading of the housing surveys and appraisal reports demonstrates how policy mechanisms and actors in urban renewal implementation disrupted Black wealth accumulation and concealed mechanisms for land-based redistribution of wealth to the white citizenry of Charlottesville. First, the condition of houses, as measured by assessors, was correlated strongly with whether the properties were rented or owned. In fact, most structures in poor condition were rentals, and housing quality was on average higher for owner-occupied structures (). This reveals that, far from being to blame for the “about to fall down” conditions of these structures, these residents, with few other housing choices, were actually victims of neglect by property owners. Second, many owners of these properties resided elsewhere in the city in white neighborhoods. Though some prominent Black families also owned rental units, these were on average in better condition than those units owned by whites. Most rental properties were actually owned by whites, many of whom were well placed in local politics and business. These figures could have been used to argue for remedies for structural and systemic disinvestment. Instead, Black wealth accumulation and housing stability was disrupted by demolition. In sum, players from outside these neighborhoods produced blight to their own economic benefit.

Figure 15. Analysis of appraisal reports for Vinegar Hill reveals that Black-owned properties, especially owner-occupied houses, were strongly correlated with better conditions in areas targeted for urban renewal. (Image by authors.)

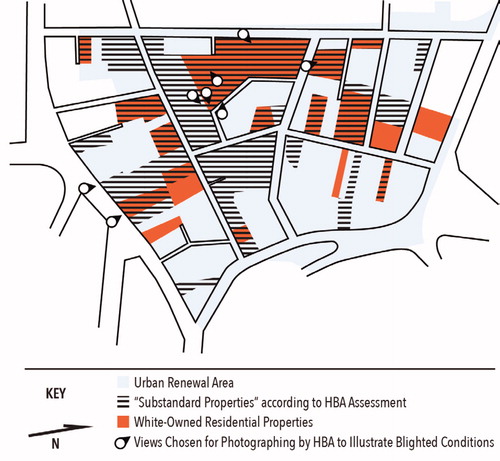

Combining these insights with the analysis of selective photography used as justification for blight designation in the urban renewal application, one can easily see the ways that white neglect was rhetorically transposed onto perceptions of Black residents ( and ). HBA used images of properties owned by white people to illustrate slum conditions, and properties cited as “substandard” in assessment maps were overwhelmingly rental properties. In contrast, Black-owner-occupied homes were for the most part not designated as substandard, but the overrepresentation of white-owned “substandard” homes and businesses in the imagery selected contributed to the erasure and invisibility of Black middle-class spaces within the district.

Figure 16. Comparison of photograph positions and patterns of ownership reveals that the “typical” conditions of Vinegar Hill were the result of neglect by white property owners residing elsewhere. (Image by authors.)

In addition, verbal descriptions in the appraisal reports recorded substantial investments in maintenance and improvement in residential properties in these communities. For instance, one report notes, “The house has been completely remodeled inside and outside. The exterior was frame siding when purchased. The buyer added the stucco outside, built new fences around yard, built concrete steps and two porches, installed central heating and remodeled the kitchen and bath.”82 Other improvements found throughout the neighborhood included additions, landscaping, and upgraded utility systems. Several properties had likewise been owned for decades or even generations.

Substantial areas within these neighborhoods were owned by Black families and reflected the accumulation of Black wealth despite structural challenges. The evidence drawn from appraisal reports challenges representations of the neighborhood as blighted and provides a measurable illustration of oral histories, which characterize it as a thriving Black community. As Saunders and Shackelford wrote, “during its prime, the Hill itself stood as something of a symbol against … exploitation… . [I]t was a part of town where at least some degree of black advancement and prosperity was extremely evident.”83 Oral accounts like these can point contemporary researchers to planning reports, maps, images, and texts as key evidence supporting more nuanced and complex analyses of the built and social fabrics of now-demolished neighborhoods, and they provide evidence, as we strive to do here, of planners’ and designers’ careful and selective construction of images of blight.

While condition and type of building materials are a crucial part of the evaluation of the urban landscape, regulatory standards related to these materials require representations that function as transparent and neutral translators. However, scrutiny of historical representations in Charlottesville reveals the distortions introduced by their authors, challenging the seemingly objective character of something as supposedly solid as matter. The application of the concept of blight to urban policy is an especially telling example of this slippage between matter and representation. As the case of urban renewal in Charlottesville reveals, the careful construction of maps and images created differences and causalities that perpetuated unjust policies rather than rectifying them, while accruing benefits for the city’s white population. This work unfolded through a suite of definitional and visual tactics and omissions that favored a particular narrative and set of outcomes beneficial to the city’s white residents. The challenge for designers and planners, whether engaging with contemporary plans or analyzing historical records, is how to avoid, critique, and decode the othering tropes we have identified here, which represent some but not all tools that have contributed to the racialization of American cities and buildings. These efforts must be part of a broader project of turning the gaze away from whitewashing histories and design interventions that merely address symptoms of this unjust history and toward a collective project of analyzing and deconstructing systemic racism.

Acknowledgments

This effort benefited from the substantial time and training efforts of Lydia Fulton and rigorous attention to detail by a research team including Katherine Rossi, Tarin A. Jones, Jessica Smith, and Ciara Horne. The project was supported by the Office of the University of Virginia Vice President for Research, the University of Virginia Equity Center, and the University of Virginia Schools of Architecture and Engineering.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kevan J. Klosterwill

Kevan J. Klosterwill is a candidate in the University of Virginia’s Ph.D. program in the constructed environment. He holds a BLA and MLA from the University of Georgia. His research explores the idea of “worldmaking” as a frame for historical and contemporary spatial practices, encompassing their material, socioecological, and narrative dimensions.

Alissa Ujie Diamond

Alissa Ujie Diamond is a landscape architect and a candidate in the Ph.D. program in the constructed environment at the University of Virginia. Alissa earned a BS in architecture in 2002 and an MLA in 2008, also at the University of Virginia. Her current research examines the intersections of design, everyday life, and racial history in the US, with a focus on the ways spatial histories can become levers for social change.

Barbara Brown Wilson

Barbara Brown Wilson is an assistant professor of urban and environmental planning in the School of Architecture, University of Virginia, and is faculty director of the Equity Center there. Her research focuses on the intersections between social and ecological issues, and on the role of lived expertise in land use decision-making. She is the author of Resilience for All: Striving for Equity Through Community-Driven Design and of Questioning Architectural Judgement: The Problem of Codes in the United States.

Jeana Ripple

Jeana Ripple is an associate professor of architecture at the University of Virginia, founding principal of the architecture practice MIR Collective, and a founding editor of TAD: Journal of Technology | Architecture + Design. Her research focuses on the impact of building codes on socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

Notes

1 Eldridge Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew: His Contributions to American Urban Planning (Urbana, IL: Department of Urban and Regional Planning, 1993).

2 James M. Marshall, “Appraisal Report: Vinegar Hill Area, Charlottesville, Virginia, Urban Renewal Project Number VA - R - 12,” 1960. Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society.

3 We have chosen to capitalize “Black” but not “white” throughout this article. Capitalization of both words is contested, but we are adopting the style of a local news outlet, Charlottesville Tomorrow. We feel this best redresses the historical convention of capitalizing “White” and not “black” or “Negro” that W. E. B. DuBois contested in the early twentieth century, and it draws attention to the fact that whiteness, though it is often considered a-racial or invisible, depends on comparative juxtaposition to social constructions of Blackness. Elliott Robinson (@EXIT265C), “Charlottesville Tomorrow is making a break from a portion of Associated Press style. We now capitalize Black and Indigenous when referring to people, culture and community in our articles. #ctom,” Twitter, September 12, 2019, 2:35 p.m., https://twitter.com/EXIT265C/status/1172217243041710081; Merrill Perlman, “Black and White: Why Capitalization Matters—Columbia Journalism Review,” Columbia Journalism Review, June 23, 2015, https://www.cjr.org/analysis/language_corner_1.php; and Lori L. Tharps, “The Case for Black with a Capital B,” New York Times, November 8, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/19/opinion/the-case-for-black-with-a-capital-b.html.

4 Robert A. Beauregard, “Planning with Things,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 32, no. 2 (June 2012): 182–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X11435415.

5 Andrew M. Shanken, “The Visual Culture of Planning,” Journal of Planning History 17, no. 4 (November 2018): 300–19, https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513218775122.

6 “The Racial Dot Map,” Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, accessed May 2, 2019, https://demographics.coopercenter.org/racial-dot-map.

7 Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew.

8 Edward G. Goetz, Rashad Williams, and Anthony Diamano, “Whiteness and Urban Planning,” Journal of the American Planning Association 86, no. 2 (2020): 142–56; Meltem O. Gurel and Kathryn H. Anthony, “The Canon and the Void: Gender, Race and Architectural History Texts,” Journal of Architectural Education, 2006, 66–76.

9 Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

10 Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism, 1st ed. (New York: Knopf, 1993); Edward W. Said, Orientalism, 1st Vintage Books ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

11 Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, Third edition (New York: Routledge, 2015).

12 Courtney Bonam, Caitlyn Yantis, and Valerie Jones Taylor, “Invisible Middle-Class Black Space: Asymmetrical Person and Space Stereotyping at the Race-Class Nexus,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 23, no. 1 (January 2020): 24.

13 Bonam, Yantis, and Taylor, 42.

14 Sheila Jasanoff, “The Idiom of Co-Production,” in States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order, ed. Sheila Jasanoff (London: Routledge, 2004), 2.

15 Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim, Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

16 Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (New York: Norton, 2011); and Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2015).

17 David N. Livingstone, “Race, Space and Moral Climatology: Notes Toward a Genealogy,” Journal of Historical Geography 28, no. 2 (April 2002): 159–80, https://doi.org/10.1006/jhge.2001.0397.

18 Carl A. Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

19 Timothy C. Baird and Bonj Szczygiel, “The Sociology of Professions: The Evolution of Landscape Architecture in the United States,” Landscape Review 12, no. 1 (2007): 3.

20 Lesley Naa Norle Lokko, ed., White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 29.

21 Kenrick Ian Grandison, “Negotiated Space: The Black College Campus as a Cultural Record of Postbellum America,” American Quarterly 51, no. 3 (1999): 529–79.

22 Mabel O. Wilson, “Dancing in the Dark: The Inscription of Blackness in Le Corbusier’s Radiant City,” in Places Through the Body, ed. Heidi Nast and Steve Pile (Abingdon: Routledge, 1998), 100.

23 Jon A. Peterson, The Birth of City Planning in the United States, 1840–1917 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003); and Jason Corburn, “Reconnecting with Our Roots: American Urban Planning and Public Health in the Twenty-First Century,” Urban Affairs Review 42, no. 5 (May 2007): 688–713, https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087406296390.

24 Martin V. Melosi, The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2000), 58.

25 Thomas Fisher, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Campaign for Public Health,” Places Journal, November 15, 2010, https://doi.org/10.22269/101115.

26 George Lipsitz, “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape,” Landscape Journal 26, no. 1 (2007): 10–23.

27 Lipsitz, 13.

28 Christopher Silver, “The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities,” in Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows, ed. June Manning Thomas and Marsha Ritzdorf (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997), 23–42.

29 Quoted in Silver, 192.

30 “Charlottesville City Council Minutes,” City of Charlottesville, February 15, 1912.

31 Clement E. Vose, Caucasians Only: The Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the Restrictive Covenant Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959).

32 See Jordy Yager’s work with the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center for more on racial covenants in Charlottesville at Mapping Cville (blog), https://mappingcville.com/. Last Accessed July 9, 2020.

33 “Fry’s Spring Terrace,” Daily Progress, April 8, 1913.

34 “Greenbrier,” Daily Progress, January 9, 1959.

35 Thomas and Ritzdorf, Urban Planning, 65.

36 Eric S. Yellin, “The (White) Search for (Black) Order: The Phelps-Stokes Fund’s First Twenty Years, 1911–1931,” Historian 65, no. 2 (December 2002): 319–52, https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6563.00023.

37 Joseph Heathcott, “‘The Whole City Is Our Laboratory’: Harland Bartholomew and the Production of Urban Knowledge,” Journal of Planning History 4, no. 4 (November 2005): 322–55, https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513205282131.

38 Silver, “Racial Origins of Zoning.”

39 Ellsworth Huntington, Civilization and Climate, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1922).

40 Marjorie Felice Irwin, The Negro in Charlottesville and Albemarle County (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 1929), 43.

41 Bonam, Yantis, and Taylor, “Invisible Middle-Class Black Space.”

42 Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew.

43 “Robert Moses on Slum Clearance,” WNYC, NYPR Archives Collections, radio broadcast, April 17, 1958, https://www.wnyc.org/story/robert-moses-on-slum-clearance/.

44 M. T. Fullilove, “Root Shock: The Consequences of African American Dispossession,” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 78, no. 1 (March 2001): 72–80, https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.1.72.

45 Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

46 Sara E. Wermiel, The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the Nineteenth-Century American City (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

47 David Listokin and David B. Hattis, “Building Codes and Housing,” Cityscape 8, no. 1 (2005): 21–67. Baltimore, MD.

48 Christine Meisner Rosen, The Limits of Power: Great Fires and the Process of City Growth in America (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

49 Karen Sawislak, Smoldering City: Chicagoans and the Great Fire, 1871–1874 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

50 William B. Rose, Water in Buildings: An Architect’s Guide to Moisture and Mold, 1st ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2005).

51 Official Building Code and Builder’s Directory, Charlottesville, VA, 1924 (Charlottesville, VA: Code of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia, 1924). City of Charlottesville, Virginia, Official Building Code and Builder’s Directory (The Michie Co. 1924).

52 Jeff Ueland and Barney Warf, “Racialized Topographies: Altitude and Race in Southern Cities,” Geographical Review 96, no. 1 (2006): 50–78.

53 Clarence Perry, “The Neighborhood Planning Unit,” in The City Reader, ed. Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout, 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 2011), 489.

54 Colin Gordon, “Blighting the Way: Urban Renewal, Economic Development, and the Elusive Definition of Blight,” Fordham Urban Law Journal 31 (2004): 305–38; Hudson Hayes Luce, “The Meaning of Blight: A Survey of Statutory and Case Law,” Real Property, Probate and Trust Journal 35, no. 2 (Summer 2000): 389–478; George Lefcoe, “Finding the Blight That’s Right for California Redevelopment Law,” Hastings Law Journal 52 (2001): 991–1036; G. E. Breger, “The Concept and Causes of Urban Blight,” Land Economics 43, no. 4 (November 1967): 369, https://doi.org/10.2307/3145542; and Christopher S. Brown, “Blinded by the Blight: A Search for a Workable Definition of Blight in Ohio Comments and Casenotes,” University of Cincinnati Law Review 73 (2005): 207–34. [Mismatch]

55 Patricia Hureston Lee, “Shattering Blight and the Hidden Narratives That Condemn,” Seton Hall Legislative Journal 42 (2017): 31.

56 James Robert Saunders and Renae Nadine Shackelford, Urban Renewal and the End of Black Culture in Charlottesville, Virginia: An Oral History of Vinegar Hill (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998).

57 Lipsitz, “Racialization of Space.”

58 Thomas and Ritzdorf, Urban Planning, 66.

59 Robert K. Nelson et al., “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond, accessed April 21, 2020, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/; and Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 1st ed. (New York: Liveright, 2017).

60 Saunders and Shackelford, Urban Renewal, 8–23.

61 Saunders and Shackelford, 41–45.

62 They noted that the city had only 1,300 Black registered voters, in contrast to a city of 29,427, where 19 percent of the population was Black. Saunders and Shackelford, Urban Renewal.

63 K. Ian Grandison, “The Other Side of the ‘Free’ Way: Planning for ‘Separate but Equal’ in the Wake of Massive Resistance,” in Race and Real Estate, ed. Adrienne Brown and Valerie Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 218.

64 Christopher S. Combs, “A Community in Turmoil: Charlottesville’s Opposition to Public Housing,” Magazine of Albemarle County History 56 (1998): 118–53.

65 League of Women Voters of Albemarle, “Charlottesville’s Slums: A Problem for Citizens,” 1952. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

66 Citizens Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee, “You Can Help Get Rid of Our Slums: Vote for all Three Housing Sites […],” 1967. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

67 Francesca Russello Ammon, “Picturing Preservation and Renewal: Photographs as Planning Knowledge in Society Hill, Philadelphia,” Journal of Planning Education and Research, December 5, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18815742; Wes Aelbrecht, “Decline and Renaissance: Photographing Detroit in the 1940s and 1980s,” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 2 (March 2015): 307–25, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214563500; and Mike Christenson, “Research Notes: The Photographic Construction of Urban Renewal in Fargo, North Dakota,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 23, no. 2 (2016): 116–28, https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.23.2.0116.

68 Vikramaditya Prakash, “Between Objectivity and Illusion: Architectural Photography in the Colonial Frame,” Journal of Architectural Education 55, no. 1 (2001): 17.

69 Themis Chronopoulos, “Robert Moses and the Visual Dimension of Physical Disorder: Efforts to Demonstrate Urban Blight in the Age of Slum Clearance,” Journal of Planning History 13, no. 3 (August 2014): 207–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513213487149.

70 City of Charlottesville, “Report to Our Citizens,” 1964. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

71 HBA. “Final Project Report, Part 1—Application for Loan and Grant, Urban Renewal Project No. VA R-12, Vinegar Hill Project,” June 1960. Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society.

72 Lokko, White Papers, 31.

73 Dianne Suzette Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

74 Wilson, “Dancing in the Dark,” 134–38.

75 Lovelace, Harland Bartholomew.

76 Joint Health Department, “An Appraisal of the Quality of Housing: Charlottesville, Virginia,” 1951, 8. University of Virginia Libraries [Note to editor: Not in Special Collections… in the regular circulating collections].

77 J. B. Harley and Paul Laxton, The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002); W. E. B. Du Bois, Whitney Battle-Baptiste, and Britt Rusert, W. E. B Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America, 1st ed. (Amherst, MA; Hudson, NY: W. E. B. Du Bois Center, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Princeton Architectural Press, 2018); and Alexander G. Weheliye, “Diagrammatics as Physiognomy,” New Centennial Review 15, no. 2 (2015): 23–58.

78 HBA, A Preliminary Report upon Housing: Charlottesville, Virginia (Atlanta, GA: HBA, Southeastern Office, May 1957), 10.

79 Gillian M. Craig, “‘Nation,’ ‘Migration’ and Tuberculosis,” Social Theory & Health 5, no. 3 (August 2007): 267–84, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700098.

80 Martha Hargraves and Richard W. Thomas, “Infant Mortality: Its History and Social Construction,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 9, no. 6 (1993): 17–23.

81 Marshall, “Appraisal Report.”

82 Marshall, “Appraisal Report.”

83 Saunders and Shackelford, Urban Renewal, 20.