Abstract

Canada has adopted stricter immigration policies within the last thirty years, which criminalize forced migrants. This has resulted in the construction of immigration holding centers (IHCs), buildings built exclusively for the detainment of undocumented individuals. As part of a directed design studio research project, the Laval IHC in Quebec, Canada, was examined by reconstructing government-issued design guidelines obtained using public access to information requests. The resultant project employs architectural documents as evidence to rebuild the interior spaces of the building through conventional tools of architectural representation, such as drawing, photography, and physical and computer modeling. By unveiling architectures shrouded in secrecy, this article illustrates how the design of these infrastructures legitimizes the narrative that undocumented migrants are “illegal” and should be incarcerated.

Keywords:

Migrant detention facilities are made inconspicuous in multiple ways. They are sited in far-flung suburban areas obscured by layers of fencing, and bureaucratic euphemisms, such as Immigration Holding Centres (IHCs) in Canada, Processing Centers in the United States, or Reception Centers in certain European countries, are enabled to misconstrue their function.1 In Canada, few if almost no photographs of IHC interior architecture are publicly available, as media access to these facilities is highly restricted. This paradigm is reinforced by how these buildings are discussed and designed within professional practice, as many architects repudiate or relinquish accountability for their involvement in the design of these infrastructures that perpetuate the narrative that forced migrants are “illegal” and deserve imprisonment. Architectural tools, such as drawing and modeling, however, can be operational to reconstruct these underrepresented and hidden spaces. Drawing upon architectural documents as evidentiary material, visual representations of the interior architectures of IHCs can bring about methodological and ethical discussions within architectural discourse regarding the ways in which representation can be used to interrogate and understand the role of architecture in concealing the process of immigration detention, an ostensibly unrelated political procedure.

Building Structures of Power from Policy

Only within the last thirty years has Canada become more aggressive in its implementation of immigration policies, introducing laws that make landing on Canadian soil without papers a criminal offence. This criminalization has been instituted through several laws, including the Deterrents and Detention Act (Bill C-84) passed in 1987, making it an offence to aid any Canadian-bound migrant who is not in possession of valid travel documents. Canada has also become more aggressive in its interdiction practices, the process of turning away asylum claimants before reaching their destination country, by deploying increased numbers of immigration officers overseas, amendments to the Immigration Act (Bill C-86), and the introduction of the Safe Third Country Agreement in 2002.2

Alongside these legislative measures, the Canadian government has invested $138 million into the National Immigration Detention Framework, a program contributing funding and political support for the design and construction of IHCs.3 The programmatic concerns were previously satisfied by architectures that could be adapted as “temporary” solutions, in the form of converted hotels, rooms in airports, camps, and in many cases, prison cells.4 The criminalization of undocumented individuals has become so commonplace that new buildings are being constructed despite the UN’s assertions that the right to seek asylum is a human right and that detention should be avoided.5 While Canada is one of many Western nations employing IHCs as a response to migrations of undocumented individuals, the rapid construction and expansion of IHCs are a metric by which we can evaluate the country and its evolving attitudes toward forced migrants.

Historically, certain architectures act as mediums translating political forces into designs with embodied realities for people.6 From public restrooms to psychiatric hospitals and prisons, architecture is instrumentalized as a tool to exercise control over the body’s freedom of movement. The infrastructures of immigrant detention are another such example, enforcing power relations and upholding the Global North as an attractive place that has the capacity to select between “desirable” immigrants, from wealthy capitalist nations, and those deemed “undesirable.”7 Often individualized from racialized groups, the “undesirable” figure holds no rights or privileges within the state. The forced separation of individuals without status from the general population and the arbitrary imposition of indefinite periods of waiting both legitimize the migrant’s illegality and necessitate the construction of these facilities.8 Architecture is not separate from the legal frameworks that help shape buildings. In the case of immigration detention, design bolsters policy, reinforcing the ideologies that initially ushered them in.9 Laws may shape the ways in which these spaces are designed, but their architecture institutionalizes the criminalization of forced migrants.

Reconstruction as Representation: Modeling the Laval Detention Center

Using the to-be-built Laval IHC (Lemay Architectes), in Laval, Quebec, as a case study, this investigation examines the ways in which architecture and policy are inextricably tied. Since the announcement of the construction of the new detention center in Laval, backlash has followed in the form of protests during 2019 in front of the architect’s office in Montreal and vandalism of the Lemay office and a partner’s vehicle in reaction to the firm’s involvement.10 Lemay issued a public statement reasserting its renunciation of responsibility, responding that the firm “would like to remind you that our mission is to create quality environments, and our project of the new Laval Immigration Center is no exception.”11 This exchange illustrates that, beyond aesthetics, accountability is being demanded of architectural professional practice and that architects are no longer perceived as autonomous creators, untethered to larger political forces. In the case of the IHC, architecture works to other undocumented migrants from the general population. Investigative architectural reconstruction, both within design studio education and practice, is one method of grappling with such problems and acknowledging the culpability of architecture in shaping the prison industrial complex.12

The use of architectural representation to better understand obscured processes, architectures, or events is not novel: practices such as Forensic Architecture and the Office for Political Innovation are two groups of architects that examine design evidence through a range of mediums, such as drawing, diagramming, computer modeling, and rendering, to illustrate sociopolitical unknowns. In the case of Forensic Architecture’s projects, architecture often serves as a backdrop to larger political processes, and architectural documentation (along with open-source information) is used to reconstruct spaces where state violence, legal injustice, or environmental destruction has occurred, thus confirming facts. The Office for Political Innovation uses annotated drawings and network maps of economic and political forces to better understand the mechanics of statecraft on built projects while sometimes staging interventions on project sites to illustrate the role of policy on the built work. Rather than looking to corroborate information, depict actors, or simply illustrate spaces didactically, the project illustrated in this article uses fragments of redacted primary source documents to reconstruct images of spaces to be built and nearly impossible to photograph once they are built. Alongside these methodologies, this project aims to provide clues as to how an unconstructed building will operate, thus opening a discussion about how architecture works to other its occupants.

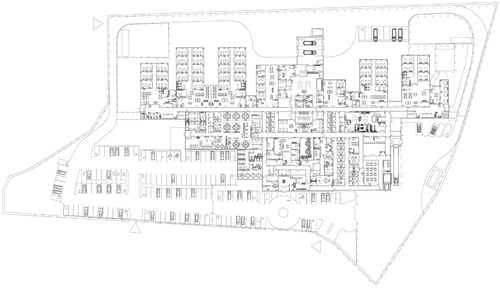

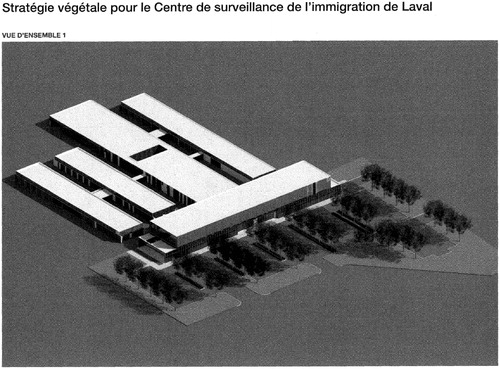

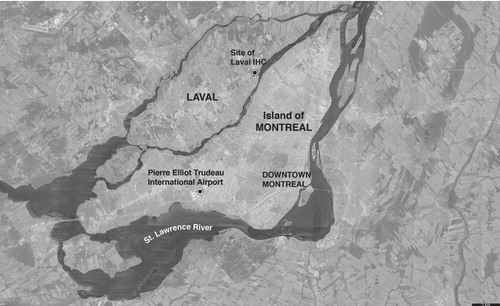

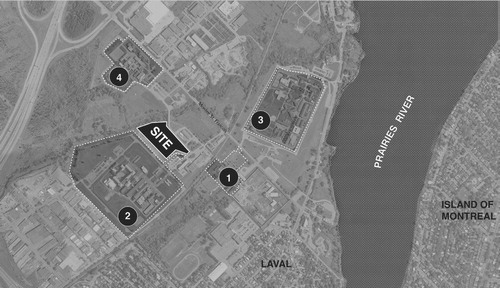

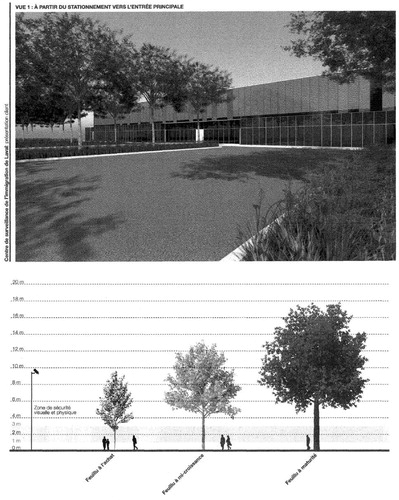

Early schematic designs and “Room Space Data Sheets” for the Laval IHC were produced by Chernoff Thompson Architects (). Their schematic plan was used as the basis for much of the reconstruction presented in this research for the dimensions and placement of furnishings, as the Canadian government did not release an update plan through the conducted Access to Information request. Updated designs and guidelines for the Laval IHC were later produced in 2017 by Lemay Architectes, although they were only partly released in public (). By actively examining these sources, the role of design in the concealment of the IHC process can be better understood. The concept of the architectural capsule, while typically alluding to the space of individualistic cells for living, becomes useful when considering the building’s siting within a “territorial capsule”—enclosed spaces described as “non-places” by Marc Augé or “heterotopias” by Michel Foucault.13 The otherness of the IHC is enabled not only through the politics of the project or the geographic distancing of the site but also through design decisions themselves. For example, the proximity between the Laval IHC and other sites of incarceration indicates that individuals are being criminalized, regardless of the new rhetoric surrounding the facility. While the generic principles for the IHC design specify that “the facility should not present itself to the public or detainees as a correctional institute that is non-institutional in its design,”14 its siting indicates otherwise (). Furthermore, the specification of trees in the visitor parking lot and foliage to hide barbed-wire-topped fencing are used as strategies to soften the appearance of the new Laval IHC. However, no trees are provided in the detainee yard, which suggests that such trees are meant not for the aesthetic pleasure of detainees but for the concealment of its carceral nature ().15 Another early guideline specified that bars on detainee rooms should be spaced to prevent escape yet must be imperceptible from the building exterior.16 These design decisions shape public perception. By presenting a more “humane” exterior to the public, immigration detention becomes normalized while othering the people detained inside.

Figure 1. Schematic plan of Laval Immigration Holding Centre (IHC), designed by Chernoff Thompson Architects, published on a Canadian government tendering website. Plan adapted from Schematic Design Report, 2017. Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services, “1.3 Drawings,” ARCHIVED Immigration Holding Centre A&E Project (EF944-171885/B). (© Chernoff Thompson Architects.)

Figure 2. A 3D rendering of the Laval IHC, as designed by Lemay Architectes. The massing of the building has been rearranged significantly in comparison to the first schematic plan. The front bar, assumed to be administrative, forms both a physical and visual barrier between the public and the accommodation areas of the center, preventing the public from entering or viewing inside the facility. While privacy is a concern, the form of the building also aids in actively obscuring the process of detention occurring behind its façade. (Rendering from CBSA, Access to Information Request A-2019-00781.)

Figure 3. The site of the Laval IHC is in Laval, a suburban city separated from Montreal by the Prairies River. The geographic siting of the project, away from the city center, along an industrial road, further others the spaces of detention through its distancing from the general population. (Map by author.)

Figure 4. Site of the Laval IHC located adjacently to a road that connects several provincial and federal correctional facilities. Site 1 is the site of the existing Laval IHC in operation. Site 2 is the Leclerc Provincial Prison for women. Sites 3 and 4 are the Federal Training Centre, a maximum and minimum security prison.

Figure 5. Vegetation strategy for the Laval IHC. A rendering and section illustrate how newly bought trees will be planted closest to the detention center and how mature trees will be preserved when farthest from the “physical and visual security zone,” which includes the outdoor detainee areas. While vegetation works to mask the facility from the public, vegetation is not to be enjoyed by detainees. (Drawing and rendering from CBSA, Access to Information Request A-2019-00781.)

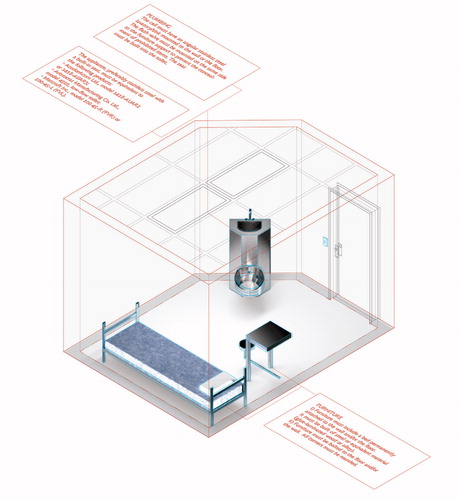

The rhetoric surrounding the Laval IHC suggests that it is “warm and homey.”17 However, the dimensioning, materiality, and furnishing elucidate the relationship between its design and that of prisons. This is reinforced by the capsular nature of the building itself, which segregates different groups (men, women, and women with children) within separate accommodation blocks. The blocks hold securitized shared washrooms, “living areas,” and bedrooms for detainees, which are subsequently subdivided into cellular space. In her graphic novel, Undocumented: The Architecture of Immigration Detention, Tings Chak, an artist and researcher trained as an architect, illustrated the ways in which anthropological and ergonomic minimums become dimensions to determine the smallest area of habitable space, ideals transferred from the domestic interior to the carceral one. The legacy of the modernist principles of existenzminimum, initially developed by Ernst May for worker’s housing, can be traced to the ways in which the cell is dimensioned and designed in contemporary practice.18 Following existenzminimum, Le Corbusier presented Modulor, a mode of measuring the proportions of the body and their relations to the residential interior. Used as the basis of measurement for many of his projects, Modulor was tested in the design of Le Corbusier’s own cabanon, a project demonstrating the minimum dimensions one person needed to live. This space contained a toilet, a sink, a desk, a shelf, a table, and a bed—furnishings of subsistence. The functional design of a prison cell often includes many of these same items, even if materially they differ: the essential furnishings one needs to live in confinement are ultimately determined in relation to the human body.

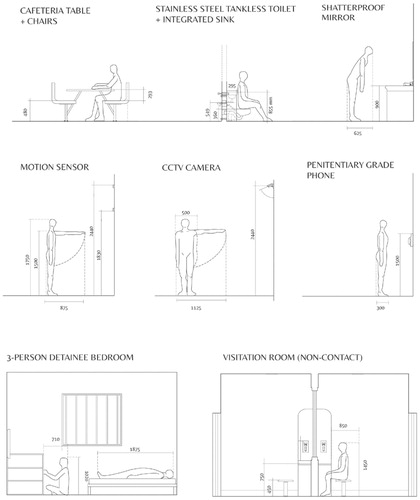

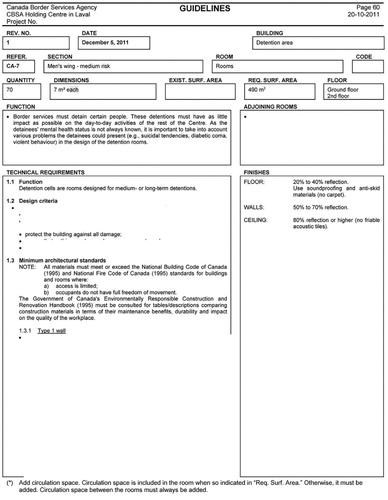

In architectures of detention, space is shaped not only by minimum dimensions but also by implications of safety and security, which demands the installation of fixed architectural devices (). These devices mediate the relationships between the human body and space: for example, surfaces and furniture must be designed in ways to mitigate self-harm but that are also resistant to abuse and destruction. One of the early design specifications written for the schematic design of a female dormitory bedroom in the Laval IHC states, “No piece of furniture or fixture provided as part of the furnishings in the Primary Accommodation rooms can be used or fashioned in a manner such that it may be used as a tool or implement for escape, or as a weapon. In this regard, the Contractor must design the room to eliminate protruding objects that could heighten the risk of suicide by hanging, ensure maximum surveillance of Detainees in the rooms, protect the building against damage, and prevent the concealment of weapons and prohibited objects.”19 The use of razor wire, fencing, security cameras, motion sensors, security glass, and locking mechanisms are all material manifestations of the complicity of architecture in the institutionalization of immigrant detention.20 Isolation rooms, in particular, illustrate the extent to which prison designs have come to inform IHC plans and details, as revealed by their materiality and choice of fixtures (). The complexity of such a building and the choice of materials, plumbing, ventilation, and details are all aspects of the project that must be resolved by architects.

Figure 6. Typical dimensions of “devices” in relation to the human body, as adapted from Ernst Neufert’s Architects’ Data (1936), a standard reference guide for human measurements. The cultural connotations embedded within these devices relate to prison design, as most are employed in the construction of penitentiaries; however, in this context, they have been repurposed for the surveillance and control of migrants. (Drawing by author.)

Figure 7. Plan of a solitary confinement cell (left); plan of an isolation area in the Laval IHC (right). The minimum dimensions for a cell in a correctional institution is 6.5 m2, while the minimum dimension for a solitary confinement “room” in the detention center is 7 m2, only half a square meter larger. Notably, the design of a solitary confinement room at the IHC is closer to a standard maximum-security cell than even to a medium-security cell. Furthermore, in federal guidelines, minimum-security cells are drawn with a separate toilet and sink, both made from ceramic materials, whereas the maximum-security cell is drawn with a stainless steel toilet-integrated-sink. The design language of this fixture is distinguishably carceral. (Plans drawn by author. Plan of solitary confinement cell adapted from “Federal Correctional Facilities Accommodations Guidelines 2015”; plan of isolation area adapted from “1.3 Plans” from “Schematic Design Report,” 2017.]

![Figure 7. Plan of a solitary confinement cell (left); plan of an isolation area in the Laval IHC (right). The minimum dimensions for a cell in a correctional institution is 6.5 m2, while the minimum dimension for a solitary confinement “room” in the detention center is 7 m2, only half a square meter larger. Notably, the design of a solitary confinement room at the IHC is closer to a standard maximum-security cell than even to a medium-security cell. Furthermore, in federal guidelines, minimum-security cells are drawn with a separate toilet and sink, both made from ceramic materials, whereas the maximum-security cell is drawn with a stainless steel toilet-integrated-sink. The design language of this fixture is distinguishably carceral. (Plans drawn by author. Plan of solitary confinement cell adapted from “Federal Correctional Facilities Accommodations Guidelines 2015”; plan of isolation area adapted from “1.3 Plans” from “Schematic Design Report,” 2017.]](/cms/asset/bec042a0-b596-4ee3-8c29-ddb9ab262aec/rjae_a_1790939_f0007_b.jpg)

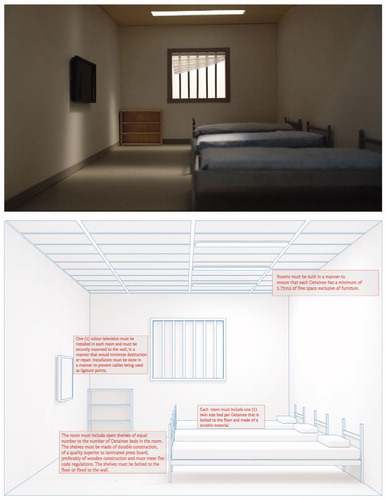

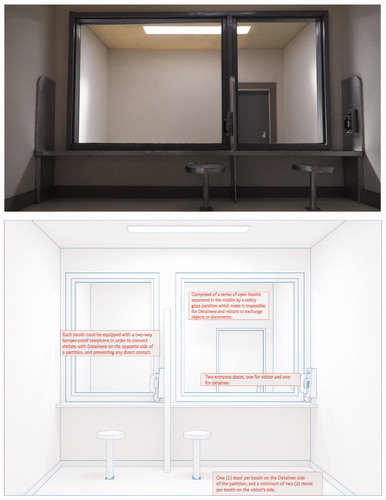

To depict the interior spaces of the Laval IHC, schematic plans from government tender websites and documents were obtained through the Access to Information Act, a law that allows citizens to request public information from Canadian government agencies. These room space guidelines were used to understand what the various interior spaces of the Laval IHC may look like once constructed. Perspective drawings were created from a 3D model generated from the schematic plan and have been annotated with the specifications of the room space guidelines, illustrating how policy has informed design decisions. While these drawings were useful to understand the implications of the design, they do not allow for an embodied experience on the part of the viewer, which led to the construction of large-scale 1:10 models. The models were constructed from MDF and painted using a latex-based paint (). Baseboards, ceiling tiles, and floor surfaces were made using different textures of cardstock and paper so that the surfaces would be captured differently on camera, depending on if they were meant to appear reflective or matte, as specified in the room space guidelines ().21 Furniture was constructed from wood and 3D-printed components painted to resemble the furniture in the catalogs of prison manufacturers ().

Figure 8. The 1:10 Model of Hallway. The physicality of the object of the model becomes evident when placed within another space, as the entire model measures approximately 6 m long. Although conspicuous in size, the exterior of the model reads as a blind box, indistinguishable until approached and peered into. (Photograph by author.)

Figure 9. Redacted room space guidelines for a solitary confinement room. This information was used to select materials for the model reconstruction. (Room space guidelines from Access to Information Request A-2019-00781.)

Figure 10. Solitary confinement room, fixtures, and manufacturers. Furniture is drawn based on CORCAN online catalogs, a manufacturer and construction service provider operated by Canadian Correctional Services, which employs the labor of existing and previously incarcerated people. (Drawing by author.)

Three spaces were built: a three-person detainee bedroom, a noncontact visitation room, and a corridor. The immigration detention bedroom was reconstructed to explore the elements of false domesticity within the IHC, as these rooms are intended to house detainees for longer periods of time, with three detainees assigned to each room. While each is given approximately 5.75 m2 of personal space, privacy is limited.22 Each detainee has a bed and an accompanying shelf; however, some personal belongings are restricted, such as cell phones.23 A noncontact visitation room was reconstructed as it operates in an explicitly carceral manner. In some cases, the physical separation of the glass is used to separate Canadian citizens from noncitizens (e.g., Canadian children may only speak with their detained parents from the other side) at the discretion of the facility officers.24 The models became literal fragments presenting redacted information obtained from the design documents (). The models were filmed, introducing a durational element to otherwise static images, highlighting the fact that many detainees are not informed if or when they will be released (and there is no limit on the amount of time one can be detained in Canada). The film itself is protracted and slow, the longest segment of the film is a single-take tracking shot traveling down the center of a 60-m corridor connecting the accommodations to the intake area where detainees would arrive. Overlaying the images are audio clips recorded from the site of the IHC—sounds of footsteps walking near the perimeter, wind, and vehicles driving on the nearby industrial road. By employing filmic depictions alongside drawings of architectural devices within the facility, the work contrasts the banality of architectural drawing against the affective qualities of these spaces. This research was conducted by the author during a year-long master’s project executed within a design-studio research program at McGill University. Similar methods of extrapolating and reassembling spaces from documentary material could be employed for research studios elsewhere, where students are asked to use model- and image-making as a way of unraveling the implications of architects in the creation of hidden yet politically charged spaces.

Figure 11. Still from a video of a 1:10 model of a detainee accommodation room, compared to the drawing of the space as reconstructed from room space guidelines. Each accommodation unit is installed with a color television, and all furniture is penitentiary grade to mitigate self-harm. The furniture was reconstructed based on dimensions and images of CORCAN furnishings. (Drawing and photograph by author.)

Figure 12. Drawing of a noncontact visitation room as reconstructed from the room space guidelines and annotated with the guidelines’ text, along with the corresponding model built from the plan in a schematic design report and its accompanying room space guidelines. (Drawing and photograph by author.)

The possibility of recreating the space of the Laval IHC was afforded through the availability and subsequent interpretation of authorized design documents. While these documents have been prepared and stamped by architects, detention center projects rarely appear in the public portfolios of the offices that produce them. At the time of writing this article, the Laval IHC is not listed on the websites of Chernoff Thompson Architects or Lemay Architectes, although both firms are credited on public government tender websites.25 This decoupling of designer and building further abstracts and absolves the architects’ involvement in their execution, even though the buildings cannot come to exist without their expertise. IHCs are a result of the Canadian government’s desire to demarcate and uphold geopolitical borders and maintain sovereignty over settler-colonial territory, and their architectural qualities reinforce a status quo where undocumented migrants are criminalized and alienated—values that become concretized through building design. By examining design documents and rebuilding spaces often obscured and placed outside the discussions of the traditional design canon, representational reconstruction can turn the lens of architecture back on the profession itself. In doing so, it asks in what ways architecture is complicit. And if so, how should it be held accountable?

Acknowledgement

This project was supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada through the Canada Graduate Scholarships—Master’s Program.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ella den Elzen

Ella den Elzen is a researcher and designer based in Montreal, Quebec. She holds a Bachelor of Architectural Studies from the University of Waterloo and an MArch from McGill University. Currently, she works as a curatorial coordinator on exhibitions and research projects about architecture. She has worked internationally as a designer in various architecture and urban design offices, contributing to residential, commercial, and urban projects at a range of scales. Through her own practice of design research, she explores the role of architecture and its situation within contemporary social and political discourse.

Notes

1. Michel Agier, Hala Azbou-Zaki, and Clara Lecadet, Un monde de camps (Paris: Découverte, 2014), 316–23.

2. Carrie Dawson, “Refugee Hotels: The Discourse of Hospitality and the Rise of Immigration Detention in Canada,” University of Toronto Quarterly 83, no. 4 (2014): 826–46, https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.83.4.826.

3. “National Immigration Detention Framework,” Canada Border Services Agency, last modified February 14, 2019, https://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/security-securite/detent/nidf-cndi-eng.html.

4. Anna Pratt, Securing Borders: Detention and Deportation in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000), 23–52, ProQuest Ebook Central link: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=3242644.

5. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “UNHCR’s Revised Guidelines on Applicable Criteria and Standards Relating to the Detention of Asylum-Seekers,” Refworld, accessed February 1, 2020, https://www.unhcr.org/protection/globalconsult/3bd036a74/unhcr-revised-guidelines-applicable-criteria-standards-relating-detention.html.

6. Ara Wilson, “The Infrastructure of Intimacy,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 41, no. 2 (2016): 247–80.

7. Michel Agier, Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government, trans. David Fernbach (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2011), 2–8.

8. Joseph Pugliese, “The Tutelary Architecture of Immigration Detention Prisons and the Spectacle of ‘Necessary Suffering,’” Architectural Theory Review 13, no. 2 (2018): 206–21.

9. Sarah Lopez, “From Penal to ‘Civil’: A Legacy of Private Prison Policy in a Landscape of Migrant Detention,” American Quarterly 71, no. 1 (2019): 105–34, doi:10.1353/aq.2019.0005.

10. Giuseppe Valiante, “Quebec Design Firm Says It’s Being Attacked for Its Role in Immigration Detention Centre,” Globe and Mail, June 20, 2019, https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/2243262134?accountid = 12339.

11. Valiante, “Quebec Design Firm.”

12. Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003), 15–21.

13. Peter Šenk, Capsules: Typology of Other Architecture (London: Routledge, 2017), 5–10, https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.4324/9781315272177.

14. Canada Border Services Agency, A-2019-00781, “Guiding Principles for Generic Immigration Holding Center Design,” 165. Released under the Access to Information Act.

15. Canada Border Services Agency, A-2019-00781, “Client Presentation, Laval Immigration Holding Centre,” 127–29. Released under the Access to Information Act.

16. “Quebec IHC Spec Sheets,” Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services (November 24, 2016), 133, available as “1.1 Preliminary Data Sheets,” in the attachment ef944-171885_immigration_laval.zip, at ARCHIVED Immigration Holding Centre A&E Project (EF944-171885/B), https://buyandsell.gc.ca/procurement-data/tender-notice/PW-MTC-560-14362.

17. “Immigration Holding Centre (IHC) Laval, Quebec: Schematic Design Report,” Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services (May 11, 2017), 15, available as “1.3 chematic,” in the attachment ef944-171885_immigration_laval.zip, at ARCHIVED Immigration Holding Centre A&E Project (EF944-171885/B), https://buyandsell.gc.ca/procurement-data/tender-notice/PW-MTC-560-14362.

18. Tings Chak, Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention (Ottawa: Ad Astra Comix, 2017), 97–104.

19. “Quebec IHC Spec Sheets,” 172–77.

20. Raphael Sperry, “Architecture, Activism, and Abolition: From Prison Design Boycott to ADPSR’s Human Rights Campaign,” Scapegoat 7, 29–37.

21. Canadian Border Services Agency, A-2019-00781, “Guidelines,” 60–64. Released under the Access to Information Act.

22. “Quebec IHC Spec Sheets,” 182.

23. Canadian Border Services Agency, A-2019-00781, “Statement of Work,” 7. Released under the Access to Information Act.

24. Rachel Kronick, Cécile Rousseau, and Janet Cleveland, “They Cut Your Wings over Here … You Can’t Do Nothing: Voices of Children and Parents Held in Immigration Detention in Canada,” in Detaining the Immigrant Other, ed. Rich Furman et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 201–2, ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=4413904.

25. “Tender Notice,” Government of Canada, Public Works and Government Services, ARCHIVED Immigration Holding Centre A&E Project (EF944-171885/B), last modified August 10, 2017, https://buyandsell.gc.ca/procurement-data/tender-notice/PW-MTC-560-14362.