Abstract

In the eighteenth century, an African-Indigenous population in the Caribbean effectively prevented large-scale European enclosure on their island. Termed the “Black Caribs” within British primary documents, they retained control over St. Vincent, refusing to let the fate of the island succumb to systems of enslavement and plantocracies of the colonial imagination. Their refusal to accept defeat, even to this day, offers a generative view on what reparations must prioritize as a form of collective repair. Land and autonomy have endured as the guiding objectives for this Black Indigenous population, providing potential blueprints for the days ahead.

The act of repairing a wrong or a harm can suggest the ending of a conflict. Reparations as a theoretical point of analysis, a list of demands, or an organization, sometimes rests on the accepted fate after dominion, whether through colonization, enclosure, or the forging of a nation-state. Although the question of reparations is complex, it is always generative. Thinking through what reparations meant for a population specifically in the eighteenth century may seem futile or an exercise in anachronism. To repair meant something different in the 1790s, especially when positioned against attempts at colonization. However, the question of repair or compensation in the late eighteenth century points us towards identifying what objectives took precedence, and what principles were sustained by Black Indigenous inhabitants. Today, the question of reparations doubles as an examination of what our collective priority is at the moment, along with what is owed. History may provide a blueprint.

In the late eigtheenth century, the era historians deem the Age of Revolutions, African-descendant people were flipping plantocracies and colonialism on its head. Revolts against enslavement had been ongoing since the first attempts at kidnapping on Africa’s shores, but the 1780s onward were responsible for a cluster of insurrections in the Caribbean that changed the course of the world.Footnote1 A key demographic involved within this tradition were the Black Indigenous population primarily living on the island of St. Vincent and its smaller surrounding islands. In British colonial documents they were termed the “Black Caribs,” a nomenclature that today signifies their positionality and genealogy during this era. The Black Caribs were Amerindian and African people, inhabiting a multitude of skin tones, features, customs, and ideas, and up until the last half of the eighteenth century, were racialized in various ways by the British and French in accordance to unstable colonial aspirations.Footnote2 They were deemed charaibs when they behaved “amicably” and thus documented as natives, negroes when they were described as nuisances, needing to be put to labor, and finally towards the end of the century, more steadily termed Black Charaibs or Black Caribs—a racialization that would signal specific opposition to the British colonial project not just in St. Vincent but in surrounding British colonies as well.Footnote3 As British administrators grew increasingly insecure about their inability to affectively gain control over the areas they claimed were most profitable on the island, their consistency in utilizing this racialization increased. To regularly refer to them as Black or negroes in correspondence back to the metropole, or even amongst each other during council meetings in St. Vincent, would reinstate that this native population 1) had no significant claims to the land because they, like the Europeans, were visitors, and 2) that the Black Caribs could be categorized more easily as criminal when requesting more military fortifications from Whitehall, home to the central British government.Footnote4

From the seventeenth century onward, both French and British planters unsuccessfully attempted to gain control of St. Vincent, first through the submission of the Indigenous population, then through exile. Efforts intensified by the 1760s, largely due to intra-European conflict and land exhaustion in the neighboring and lucrative British colonies of Barbados and Jamaica.Footnote5 British administrators predicted that land in St. Vincent would yield as much profit as did other colonies, if not more—a faulty but maintained assumption, given that colonial maps drawn of St. Vincent correctly depicted the island as mostly mountainous terrain cradling the notorious and unpredictable volcano La Soufriére (“The Sulfur Mine”). The Black Caribs made sure early European settlements on the island were small-scale and contained, effectively maintaining control over the majority of the island. By the 1780s, British insecurities about their inability to usurp the windward, eastern portion of the island—considered the most fertile land—was starting to weigh on their ambitions against finally defeating the Black Caribs. As a result, the British colonial government in St. Vincent and the Black Caribs would engage in a struggle for control over the island, an idea that meant something very different for both parties. British administrators and planters aspired to transform St. Vincent into a plantocracy and slave society, to do what they understood as developing and cultivating usable land. This came with the imperative of a gradual, then immediate dispossession of the Black Indigenous population, by this time estimated at more than 5,000 people, including children. The Black Caribs were vehement in not just protecting their own bodily autonomy, but also the sovereignty of the land, prioritizing careful stewardship over “development” and surplus production, an ethos guided by a world of African and Amerindian Indigenous wisdom around the importance of ecosystem preservation and symbiosis.Footnote6

Throughout the eighteenth century, the question of land ownership revealed an important priority in the Black Carib struggle. By the imperial logics of treaty-ownership, both France and Britain took turns claiming St. Vincent and the Grenadine islands. At the end of the American Revolutionary War, the island was restored to the British in 1783 under the Treaty of Paris, and remained under versions of British dominion until independence in 1979. It is crucial to note, however, that during claims of European treaty-ownership, the Black Caribs maintained control of the majority of the island, including its coveted windward coast. While St. Vincent was formally owned by the British through treaty, socially, geographically, and militarily the land was completely controlled by the Black Caribs for much of the century.Footnote7 As warfare escalated, the Black Carib militia retained a strong hold over the majority of the island, and were frequently the victors during conflict with the British army. Having an intimate knowledge of the island’s terrain, they utilized guerrilla warfare tactics, as well as a network that extended beyond the shores of the island.Footnote8 The Black Caribs were skilled swimmers, divers, and canoeists, making circum-Caribbean travel quick and efficient. They were polyglots, and fluent in multiple Indigenous languages, along with English and French. Their proficiency in French, paired with the ongoing rivalry between Britain and France, enabled strategic comradery with the neighboring French army and government in Martinique.Footnote9 Much of their military weaponry and equipment were direct gifts from Martinique for the purpose of ousting the British from St. Vincent once and for all. It wasn’t until 1794, after French politician and colonial administrator Victor Hughes brought over French soldiers to join the Black Carib military, that the anti-British colonial front weakened. The aggressive French military presence muddled wartime strategies, and Joseph Chatoyer, a major leader with the Black Carib militia, was killed. Buoyed by Chatoyer’s death, British soldiers activated a program of artificial famine across the island that resulted in the starvation of Black Carib families, and the exile of a large majority of the Indigenous inhabitants first to the desolate island of Balliceaux, and then Roatán, off the coast of Honduras.Footnote10

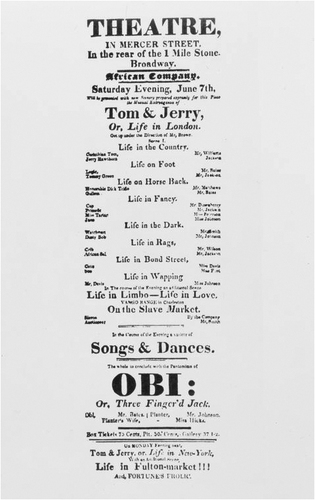

Although colonial narratives often depict the 1794 deportation and dispossession as the end of the war against the Black Caribs, the struggle for autonomy and land continued. The beginning of the nineteenth century saw the emergence of Black theater in North America, started by a Black Carib man named William Alexander Brown in New York, with his African Grove Theatre.Footnote11 The company enacted crucial interventions against European artforms, production, and literature, but perhaps one of the most stunning features was the spatial claim that the Theatre itself made. Situated on Thompson Street in Manhattan in the 1820s, Brown would erect plays right next door to an all-white production company, featuring the exact same production except with an all-Black cast.Footnote12 Brown and his castmates would face violent repercussions for these claims to space and stories. Today, the Garifuna carry on the tradition of their ancestors, the Black Caribs. While a small population still inhabit St. Vincent, the majority of Garifuna people live on the Caribbean coasts of Central America, with an increasingly large diaspora in Canada and the United States. Enclosure, as a result of Western tourism industries, centuries-deep traditions of racialized violence towards Black/Indigenous people in Latin America, biofuel industries, and the ongoing climate crisis have kept the Garifuna constantly building strategies towards land sovereignty and protection. Organizations like the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH) and Faluma Bimetu Radio work in defense of land, autonomy, and preservation. There are many more groups that are deliberately inaccessible, and unable to be found through a Google search. It is clear that in the case of the Black Caribs, or the Garifuna, this struggle has not ended, and any compensation will be inadequate until land has been freed.

Atlantic histories of colonialism and resistance are crucial towards our understanding of architecture. The struggle for ownership, the value of symbiosis with nature versus an insistence on development, the exhaustion of soil, extractive practices of property and its constituents, as well as other myriad and ongoing strategies against these inertias throughout the centuries—all contribute to our contemporary understanding of design and infrastructure. Any study of architecture is fundamentally rooted in a study of land. Beyond public or private property, the Black Caribs invested themselves in building a common space that stressed cooperation and mutualism with all, including nature, and that did not require colonial rationales of production or surplus to be valid or valuable. Their example challenges us to conceive of repair as not something given or bestowed upon a population, but instead an active coworking to deprivatize land and participate in social relations that are mutual and sustained—like William Alexander Brown in New York, or the Black Carib militia in the Caribbean. On the specific question of repayment for Black-Indigenous or Black and Indigenous people, there is also a crucial imperative that must be emphasized when thinking about this lineage. Social histories of the dispossessed and of the evicted, like the Caribs in the eighteenth century, insist that the teleology of success and defeat is faulty. Within colonial documentation there is no mention of requests for compensation, because for the Black Caribs, that would have been an admission of defeat, and an end of the war. For the Indigenous people of St. Vincent, and the Garifuna of the Atlantic diaspora, this program is still an ongoing struggle for getting land back, towards an emphatically collective repair. The enduring objective is land and autonomy, nothing less.

Figure 1. “Early 19th century African Grove Theatre playbill publicizing the production of Obi: Or the History of Three-Fingered Jack.” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 7, 2022, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-c6ff-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thabisile Griffin

Thabisile Griffin, PhD, is a historian specializing in the eighteenth century Atlantic world, Black indigeneity, and colonial insecurity. She has published in various outlets, including Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, and has lectured and presented her research at Yale, UCLA, the Shorenstein Center at Harvard, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at UPenn. Griffin is an ACLS Emerging Voices Fellowship recipient, and has lectured and programmed for the Global Racisms program and Ambedkar Initiative in the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society at Columbia University. She is Liberal Arts faculty at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in Los Angeles.

Notes

1 For more on two crucial revolts that dramatically altered the course of British and French military strategy and exposed the frailty of the colonial state, see Vincent Brown, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020) and C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Saint Domingo Revolution (London: Secker and Warburg, 1938).

2 In her text, Mia Bagneris explains how the British exaggerated phenotypic diversity among the individuals of groups that identified as Carib. Through primarily an analysis of Agostino Brunias’ eighteenth century paintings, she argues that “Black” and “Red” as applied to the Caribs were “ideological fictions built around the unmarked centrality of whiteness,” see Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias, Manchester University Press, 2018.

3 This describes the unfixed nature of race and racialization in St. Vincent, specifically after the Indigenous inhabitants were said to have mixed with a sizeable African population in the late seventeenth century. Prior to this, the Indigenous people known as the Caribs witnessed a bevy of inconsistent nomenclatures, beginning with the Spanish using the term in the early sixteenth century as a legal category “deployed against Indigenous people who resisted conquest or otherwise behaved inconveniently.” This genealogy is charted contextually in Melanie J. Newton’s article, “’The Race Leapt at Sauteurs’: Genocide, Narrative, and Indigneous Exile from the Caribbean Archipelago.” Caribbean Quarterly 60, no. 2 (2014): 5-28.

4 I discuss the emergence of criminality and its relationship to the Black Caribs in chapter 1 of my dissertation, “The Unmaking of St. Vincent: Colonial Insecurity and Black Indigeneity, 1780-1797” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2021).

5 See Eric Williams From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean, 1492-1969 (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), and Hilary Beckles’ A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Society to Caribbean Single Market (England: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

6 For more on Garifuna or Black Carib Indigenous conceptions of land and autonomy, see Joseph O. Palacio, The Garifuna, A Nation Across Borders: Essays in Social Anthropology (Belize: Cubola Publishers, 2005).

7 Robin Fabel, Colonial Challenges: Britons, Native Americans and Caribs (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000).

8 Christopher Taylor’s The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival and the Making of the Garifuna (Oxford: Signal Books, 2012) serves as the most recent and in-depth military history of the Black Caribs in St. Vincent during the eighteenth century. Taylor’s work, along with I. E. Kirby and C. I. Martin’s The Rise and Fall of the Black Caribs (Garifuna) (2004), detail the longevity of Black Carib defense, and how the Caribs, for much of the eighteenth century, regulated European settlement in St. Vincent and the nature of both British and French plantation production.

9 Griffin, “The Unmaking of St. Vincent.”

10 Griffin, “The Unmaking of St. Vincent.”

11 On the radical trajectory of William Henry Brown, see Marvin Edward McAllister’s text White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies and Gentlemen of Colour: William Brown’s African and American Theater (UNC Press: North Carolina, 2003).

12 Errol Hill specifically links William Brown to the Black Carib history of autonomous struggle in his article, “The Revolutionary Tradition in Black Drama,” Theatre Journal 38:4 (1986): 408–26, accessed August 14, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2307/3208284.