Abstract

Little Tokyo in Los Angeles has long been a community for Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens. Since its founding, Little Tokyo has been met with significant external resistance from individuals, organizations, the government, and legislation to curb its growth and reduce its footprint. This narrative focuses on the century-long resistance to these efforts and the continued strength and resilience of the local community through the lens of a little-known but significant building in Little Tokyo: the San Pedro Firm Building.

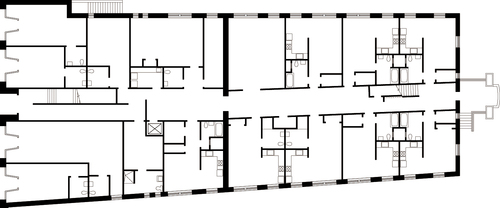

In Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo Historic District—in the parking lot behind the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA—sits an unassuming three-story brick building. It has Classical Revival style elements, and the cast-stone first floor is occupied by four commercial storefronts. The second and third floors, with exposed brick and square two-over-two windows, are home to forty-two studio apartments. Along the top horizontal band of the building are the words San Pedro Firm Building (). Modest in comparison to the surrounding Buddhist temples, condominium towers, and art spaces, the San Pedro Firm Building has, time and again, served as a catalyst in the fight for community control and cultural resilience in Little Tokyo by and for its Japanese American residents.

Figure 1. Renovated by the Little Tokyo Service Center in 1991, the San Pedro Firm Building today consists of four ground level storefronts and forty-two studio apartments for very low-income residents. Photograph by authors.

An enduring presence within the community, the Firm Building stands as an artifact of a history of racial prejudice associated with land ownership within Southern California and the Japanese American community’s recurring efforts to combat displacement and relocation through political activism. Following Japanese Americans’ fight for redress and reparations for their incarceration and internment during World War II, the building’s preservation and restoration in the 1990s marks an origin point from which many current community organizations and social development programs emerged.

While the story of racially discriminatory and exclusive practices concerning property and land ownership is well-documented, this narrative highlights a moment of resistance against these forces. The stories surrounding the San Pedro Firm Building represent a century-long struggle to resist community and cultural extraction, displacement, and erasure. The San Pedro Firm Building provides a powerful example of a community’s successful reclamation of lost property in the hopes of providing inspiration for future models and opportunities for redress, reparations, and wealth distribution amongst minority groups.

Beginnings

In 1912, fifty-four Issei flower growers came together to form the California Flower Market, a shareholder collective based in Los Angeles.Footnote1 In 1913, these Japanese growers opened the Southern California Flower Market in downtown, which to this day remains one of the largest flower markets in Los Angeles. Following the market’s initial success, in 1925 the growers commissioned architect William E. Young to design a building for the members of the collective to be located in the fledgling district of Little Tokyo.Footnote2 The second and third floors would house the flower growers, while the first floor was to be occupied by the Pacific Sewing School, a school for Japanese American girls.

The creation of the California Flower Market corporation was not only a financial decision to pool funding and resources, it was an acute strategic move that exploited a loophole in California’s Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited individual aliens from owning land and possessing long-term leases.Footnote3 After the passing of the Alien Land Law, farmers like the flower growers of the California Flower Market were forced to find new ways to hold onto and acquire buildings and land. Local business owners would form temporary credit associations, known as tanomoshi-ko, that would provide financing for new businesses. Kenjinkai were mutual aid societies amongst immigrants from the same ken, or prefecture, that provided opportunities and aid for Japanese in enclaves like Little Tokyo. Rather than submit to discriminatory legislation and relinquish any agency, the community of Little Tokyo found ways to fight exclusionary practices. The effect was twofold: a more tight-knit local community through the formation of collectives, and a flourishing model of immigrant ownership—of land, buildings, organizations, and businesses. Between 1920 and 1940, Little Tokyo became the fastest growing Japanese community in the United States.Footnote4

Incarceration and Displacement

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942 authorizing the mass removal and incarceration of all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Ordered to leave behind their belongings and take only what they could carry, approximately 122,000 men, women, and children were evacuated to assembly centers before being moved to one of ten internment camps situated in remote locations across six western states and Arkansas. Forced to sell and abandon their homes and businesses, members of the Japanese American community incurred massive financial losses with total property loss being calculated at $1.3 billion and a net income loss at $2.7 billion (in 1983 dollars per a congressional commission investigation).Footnote5 Along the entire West Coast, Japanese enclaves like Little Tokyo were quickly shuttered.

Bronzeville and Postwar Urban Renewal

These sudden vacancies left opportunities for the arrival of new residents. Labor shortages in Los Angeles’s war defense industry led to a large migration of African Americans, largely from the Southern United States, seeking work in the city. Because of racist and restrictive housing legislation, people of color were barred from living in many parts of Los Angeles. These housing covenants, paired with the forced displacement of the Japanese and Japanese American community, led to an influx of African Americans in Little Tokyo. In the 1940s, Little Tokyo adopted a second nickname—Bronzeville—and quickly became a thriving African American community.Footnote6 Given its vacancy and available bedrooms, it is presumed that during this time the San Pedro Firm Building became home for many of Bronzeville’s new residents.Footnote7

In the years after the war, Little Tokyo became increasingly diverse. Following their incarceration, many Japanese Americans returned to their communities to rebuild the lives they had left behind. Though many did not return, Little Tokyo remained an important economic and cultural center for Japanese Americans in Southern California. This was in part due to buildings like the San Pedro Firm Building which, although no longer under the ownership of the California Flower Market, provided affordable apartments and commercial space for returning businesses and new entrepreneurial projects.

The transition from Bronzeville back to Little Tokyo was complicated and representative of the community’s layered and multi-ethnic history. One contributing factor was the disappearance of local wartime defense industry jobs that led many African Americans to look for new opportunities elsewhere. Another was the preferential treatment given by white property owners to returning Japanese and Japanese American tenants and agreements between Japanese and African American business owners to buy out existing leases. There was a mix of racial tension and cooperation between these communities that reflected each group’s complex understanding of what it meant to integrate in postwar Southern California.Footnote8 Organizations such as the Nisei Progressives worked to find evicted African Americans new housing opportunities, and groups such as the Common Ground Committee sought to promote healthy interracial relations by working with African American business owners to hire Japanese American employees, and Japanese business owners to hire African Americans.Footnote9 In the case of the San Pedro Firm Building, a review of the 1956 Los Angeles City Directory reveals its thirty-three residents and renting business owners were predominantly Japanese or Japanese American, signaling a shift in the community’s identity from Bronzeville back to Little Tokyo by the 1950s.Footnote10

Seeing economic opportunities in downtown Los Angeles and the immediate areas surrounding it, developers beginning in the 1950s sought to rebuild these spaces through postwar urban renewal. The construction of the Parker Center in 1953—the Los Angeles Police headquarters located across the street from the San Pedro Firm Building—demolished a quarter of Little Tokyo’s commercial district, along with the homes of almost 1,000 residents.Footnote11 Similar events of demolition, construction, eviction, and displacement occurred throughout the downtown area, leaving the community of Little Tokyo in question, including the San Pedro Firm Building.

The Firm Building, Revisited

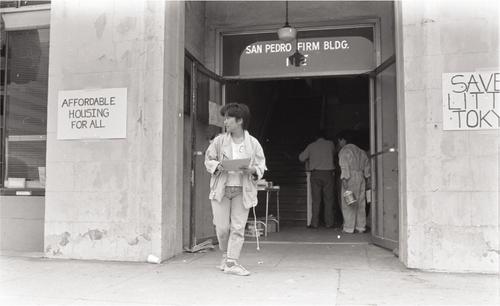

Beginning in the 1970s, work within the community began to shift towards activism, in large part due to the national fight for redress and reparations for Japanese Americans’ unjust incarceration during World War II. Many in Little Tokyo protested corporate and government interests in urban renewal. In 1974, the City of Los Angeles acquired the San Pedro Firm Building. And when the City targeted the San Pedro Firm Building for demolition in 1986 to make way for a planned $200 million extension of the Los Angeles Civic Center, it was members of the community who spoke up.Footnote12

In an effort to preserve this low-income housing for senior residents, a newly formed organization—the Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC)—created a committee to explore ways to preserve the San Pedro Firm Building.Footnote13 Their work represented one of the first organized efforts to return property to Little Tokyo stakeholders through the framework of community development. In 1987 the Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution to ensure the Firm Building be maintained as low-income affordable housing and be managed by a nonprofit community-based organization.Footnote14 Following the decision, several community groups began to organize efforts to restore the building, including one involving sixty volunteers—a majority of whom were students at UCLA, USC, and UCI ().Footnote15

Figure 2. Student volunteers from UCLA, USC, and UCI work to restore the San Pedro Firm Building on May 28, 1988. Photograph by Abraham Ferrer © Visual Communications Archives.

Figure 3. The restoration effort was organized by the Little Tokyo Community Development Advisory Committee, the Little Tokyo Tenants Association, and the UCLA Nikkei Student Union. Photograph by Abraham Ferrer © Visual Communications Archives.

In 1989, LTSC gained control of the building from the city through a fifty-year lease and partnered with the established community development corporation Los Angeles Community Design Center (LACDC) to lead a renovation effort. Work began in 1990 to improve the structure from the ground up, with the scope of work including interior finishes, added kitchens and bathrooms, and a new elevator to provide accessibility. Existing office spaces were converted to forty-two studio apartments and four ground level commercial spaces ().Footnote16 A year later, forty-seven tenants of varying ethnicities and ages moved in.

Building a Legacy Through Community-Led Development

The successful completion of the San Pedro Firm Building renovation served as a major catalyst for further community-led developments and restoring control of the area to Little Tokyo’s stakeholders. Soon after, LTSC established itself as a community development corporation (CDC) with the aim to “promote community control and self-determination in Little Tokyo.”Footnote17

Since the formation of its community development arm, LTSC has grown to become one of the eminent CDCs in the nation, providing both affordable housing within Southern California and training to other communities to develop properties within their own neighborhoods. As an organization, LTSC has built over 950 units of affordable housing, developed over 130,000 square feet of nonprofit community-based commercial real estate, employs over 130 full-time workers, and operates on an annual budget of over $9 million.Footnote18

Conclusion

Over the course of its ninety-plus year lifetime, the San Pedro Firm Building has endured as a physical marker of the power of collective effort and organizing. It represents the lives of those who filtered in and around the building—the flower growers who commissioned it, the activists who protested its demolition, the community organization that gained control and renovated it, and of course the residents themselves. Its continued presence in Los Angeles is a testament to the power and successes of the past and present collective action of those who have called Little Tokyo home.

With this narrative of the San Pedro Firm Building, we respond to Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson’s call to “expand the range of figures and objects we study to include the work on nonwhite subjects—including peoples previously deemed ‘outside history,’ whose records were seen as not worthy of preservation.”Footnote19 The story of the San Pedro Firm Building is precisely that: of both figures—the people—and objects—the building. Here, we hope to highlight the way in which a group of people were able to reverse and redirect the generations of persistent and pernicious flows of racist land legislation, urban gentrification, and displacement. With the San Pedro Firm Building, we can point to resistance, and also a true flourishing: a place where community and culture have endured, thrived, and grown.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Bill Watanabe and Alan Nishio who each spent time meeting with us to discuss their experiences serving the community and the issues facing Little Tokyo today. Thanks to Abraham Ferrer for allowing us to explore Visual Communications’ archive of photographs and for sharing his memories documenting the restoration of the San Pedro Firm Building. Thanks to Jason Tiangco and the Visual Communications staff for helping us to locate the archival images used in this manuscript. And thanks to Takao Suzuki and Larry Katata from LTSC who provided us original drawings of the renovation and gave us a tour of the San Pedro Firm Building.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nate Imai

Nate Imai is an assistant professor of architecture at Texas Tech University. His architectural and urban design research focuses on issues of land ownership, urban development, and the public realm. He is a cofounder of Oblique Labs, a design firm that explores urban and community structure through computation and construction. Imai holds a Master’s in Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a BA in Architectural Studies from UCLA. He has previously taught at the University of Tennessee, Woodbury University, and Harvard University.

Matthew Okazaki

Matthew Okazaki is an assistant teaching professor at Northeastern University. His research and creative practice focuses on alternative models of historic preservation, and the dynamics of power in places of layered or difficult histories. He is the founder of Field Office, an architecture practice based in Boston, Massachusetts, and a principal at Architecture for Public Benefit, a design firm specializing in working with nonprofits and mission-driven organizations. Okazaki holds a Master’s in Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a BS in Applied Mathematics from UCLA. He has previously taught at Tufts University, Brandeis University, and Harvard University.

Notes

1 Lauren Zuchowski, “Southern California Flower Market Papers,” Online Archive of California, accessed July 27, 2022, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89s1vfs/entire_text/.

2 National Park Service, “Little Tokyo Historic District,” last modified April 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/places/little-tokyo-historic-district.htm.

3 Cherstin M. Lyon, “Alien land laws,” Densho Encyclopedia, last modified October 8, 2020, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Alien_land_laws/. Prior to the law being enacted, Japanese immigrants owned 3,828 acres within Los Angeles County. With an average value of $192 per acre for a total of $732,000, this accumulation of property spoke to the financial success of first generation issei farmers and reinforced the connection between land ownership and prosperity for the growing Japanese American community. William M. Mason and John A. McKinstry, The Japanese of Los Angeles (Los Angeles: History Division, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, 1969), 31.

4 National Park Service, “Little Tokyo Historic District.”

5 “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942),” National Archives, last modified January 24, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9066.

6 Martha Nakagawa, “Little Tokyo/Bronzeville, Los Angeles, California,” Densho Encyclopedia, last modified October 8, 2020, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Little_Tokyo_/_Bronzeville,_Los_Angeles,_California/.

7 “112 Judge John Aiso Street —Timeline,” First Street North: Open, Visual Communications, accessed October 20, 2022, https://fsnopen.vcmedia.org/.

8 Scott Kurashige, The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008), 158-185.

9 Martha Nakagawa, “Bronzeville—Little Tokyo, Los Angeles,” Little Tokyo Service Center, accessed October 20, 2022, http://bronzeville-la.ltsc.org/; archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20221023022130/http://bronzeville-la.ltsc.org/; National Park Service, “Little Tokyo Historic District.”

10 City of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Street Address Directory, 1956, May, Los Angeles Public Library, accessed July 27, 2022, https://rescarta.lapl.org:443/ResCarta-Web/jsp/RcWebImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=026bc4f2-52f9-4cbf-b1e4-12291b1cd6d0/LPU00000/LL000001/00000001&pg_seq=655&search_doc=.

11 National Park Service, “Little Tokyo Historic District.”

12 Cathleen Decker, “Little Tokyo Takes on City Hall Again,” Los Angeles Times, December 28, 1986, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-12-28-me-985-story.html.

13 The mission of LTSC is: “to provide linguistically and culturally sensitive social services to the area and the Southern California Japanese American community.” Little Tokyo Service Center, “About Us,” accessed July 27, 2022, https://www.ltsc.org/about-2/.

14 Karen E. Klein, “Relocating Little Tokyo Elderly Shocks Group Into Builder’s Role,” Los Angeles Times, March 15, 1992, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-03-15-re-6473-story.html?_ga=2.12109693.892093456.1658704312-777184786.1658704311.

15 Lynn O’Shaughnessy, “60 Volunteers Restore a Part of the History of Little Tokyo,” Los Angeles Times, May 29, 1988, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-05-29-me-5659-story.html.

16 Klein, “Relocating.”

17 LTSC was established as a CDC in 1994. Little Tokyo Service Center, “Real Estate Portfolio,” https://www.ltsc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2017-REDD-Portfolio-Web.pdf.

18 Little Tokyo Service Center, “Real Estate Portfolio.”

19 Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson, Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 10.