Abstract

The surprise and longevity of the COVID-19 pandemic and current sociopolitical climate have exposed critical oversights of systemic transgression, particularly in education. The course “Fugitive Practice: Introduction, Recentering, and Exploration of Black and Indigenous Design Methods” was part of the emergent effort toward redressing and repairing the climate of the school classroom, which often peripheralizes Black and Indigenous bodies and cultural traditions. By lifting up underrecognized subjectivities, cultures, and methods, “Fugitive Practice” advocates for the reimagining of the frame through which architecture is qualified, represented, and produced, while calling out opportunities for the repairs of institutional harm.

The surprise and longevity of the COVID-19 pandemic and current sociopolitical climate have exposed the precarity of the United States and its supposed democracy. This volatility, however, offers an opportunity to rethink and redress entrenched norms, particularly in education. While we are witnessing an increase, at last, in the acknowledgments of systemic transgressions in higher education, institutions, governments, cultural systems, and academic disciplines remain reticent to more fully engage in the much more selfless and expensive act of repair. Indeed, the classroom is a critical place where an epistemic repair must be undertaken—by recentering and celebrating the subjects, modes, and acts of cultural production that are systemically and historically othered and marginalized in mainstream (read: white Euro-American) curricula.

In the United States nearly two decades ago, Prince Edward County in rural southern Virginia offered a mea culpa for its own troubling history with schooling. The Virginia governor, on behalf of the county, issued an apology and plans for repair for its 1959–1964 campaign to avoid court-mandated racial integration. During that period, the county maintained an extreme practice of defunding its public school system, closing schools to students for five years. Those unable or unwilling to relocate to other districts were literally locked out of formal education, generating headlines of a “lost generation” for decades. In spite of this, a coalition of local Black educators, clergy, and professionals crafted a powerful apparatus of refusal and counter-action, sited in churches, shops, and basements. JET magazines and bibles were appropriated as reading material. These impromptu teachers invented “fugitive” pedagogies and programming, practically overnight.Footnote1

It is essential to underscore the legacy of the school classroom as both an agent and site of aggression toward Black and Indigenous bodies and “othered” cultural traditions. This narrative acknowledges the cultural purchase of Black and Indigenous means of transmitting and producing knowledge, and problematizes the limitations of canonization in architectural education and scholarship. By lifting up underrecognized subjectivities and cultures, we advocate for the reimagining of the frame through which architecture is qualified, represented, and produced, while calling out opportunities for the repairs of institutional harm. This reimagining of architectural scholarship and practice centers, rather than peripheralizes, subjectivity and culture, as Saidiya Hartman writes in her work on fugitivity.Footnote2

Redress as Repair

For many architecture schools, the pandemic inspired an array of digital alternatives to the decidedly analog, hands-on discourse to which we were accustomed. In a few exciting cases, ambitious students and faculty would embrace virtual whiteboard applications like Figma and Miro to devise experimental means of collaboration and discussion. However, most simply used these applications as proxies for traditional classrooms, models, critique, and disciplinary norms. While it can be argued that the pandemic sponsored as much opportunity for repair as it did to disrupt (often profoundly, with lasting psychosocial consequences), it seems that, more than not, the familiar and conventional dynamics of power and knowledge production of the traditional classroom were simply exported into the now digital realm of our classrooms and spaces of critique.

The virtualization of the traditional classroom and its associated problems might have been the primary shift in academia had the summer of 2020 not brought about a sea change in the ways we talk about race and identity, and importantly, of the power structures that underlie those discussions. Efforts geared toward “diversity” and “inclusion” seemed poised to throw architecture—a mostly (still) white male discipline insistent on Eurocentric histories and individual genius—into sharp relief. With a similar urgency as in Prince Edward County, many marginalized academics and practitioners (especially nonwhite folks) took to Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Signal to pool ideas and resources in a spontaneous, yet uncannily collective, effort to redress the “ivory tower.” Radical antiracist and counter-institutional projects such as Dark Study,Footnote3 Dark Matter U (DMU),Footnote4 and its affiliate organization Design as Protest,Footnote5 have emerged, working within, without, and across academic institutions, daring them to hold more space for the people that have been and are silenced and unseen.Footnote6

Through an innovative disrupting of the institutional frame, coinstitutional models piloted by DMU seek to disrupt the capitalism-driven motives of schools, proposing an alternative to the “sage-on-the-stage” learning model still so prevalent in many college lecture halls. This kind of disruption was the organizing framework for our course, “Fugitive Practice: Introduction, Recentering, and Exploration of Black and Indigenous Design Methods”—a transdisciplinary, transinstitutional seminar we cotaught, cross-listed at City College of New York (2022), Howard University (2021), and Yale University. As the name indicates, the course, taught in the spring semesters in 2021 and 2022 and held via Zoom, framed Black, Indigenous, and other historically marginalized tactics of cultural production collectively as “fugitive practices.” We further define this praxis as the counter-public and often covert ways that marginalized folks effect agency and joy in spite of (and often unconcerned with) the risks of surveillance, persecution, or worse. The foregrounding of these acts of refusal—and their radical shapings of place—was our effort to destabilize prevailing expectations associated with classroom structure and discourse. For us, the use of “fugitive” to define these interests and spatial legacies underscores 1) the persistence of these practices despite being actively discouraged and suppressed, and 2) the production of knowledge from a condition of semi-coversion and escape.

Our “Fugitive Practice” course insists that the work of redressing the canons of architecture, planning, and urbanism is a means of epistemic repair. Indeed, the decision to pair students from a historically privileged institution (Yale) with a historically Black university (Howard) and Hispanic-Serving Institution (City College) was equal parts a call to action as well as a pedagogical experiment. “Fugitive Practice” challenged students to see themselves in their own work, discover value in collective production, and embrace informality through low-stakes creative output. Each session was an invitation to problematize the apparently marginal positioning of Black, Indigenous, and other intersectional subjectivities and sociospatial practices within the discipline. Tropes of the “solo genius” myth were constantly questioned: lectures were infrequent, discussions were group-led, and the overall structure was a gradient of individual to collective projects. A wide range of topics centered the body as a conduit for the transmission of culture—in gathering and performance, rhetoric, and craft. Tropes of adornment and tattoos in Black and Indigenous traditions, quilting and weaving in the American South, and the fugitive act of marronageFootnote7 worked to create an intersectional lattice of Black and Afro-Indigenous histories that questioned how architecture can be qualified and described.

Fugitive PedagogyFootnote8

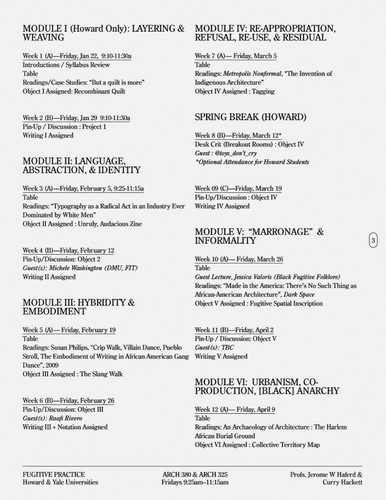

When drafting the first iteration of the course, we felt strongly that this was necessarily a multimedia project in order to fully image the milieu of cultural expressions that Black and Indigenous folks employ, often from conditions of escape, refusal, or limited mobility. This informed a set of attitudes that prefigured the course’s modules, which were supported by a counter-canonical roster of invited guests. Academics and practitioners like Amanda Williams, Jelisa Blumberg, Jessica Valoris, Mitch McEwen, and artists like @toys_dont_cry engaged the students in rich dialogues around our curated themes of Layering & Weaving, Language and Encoding, Embodiment & Dance, Re-Appropriation and Re-Use, Urbanism & Ephemerality, and Marronage. Prevalent attitudes and mediums that emerged from these discussions were in turn translated into architectural provocations. While the course examined a multiscalar suite of topics, they tended to fall on a spectrum ranging from the scale of the body to the architectural and urban scale.

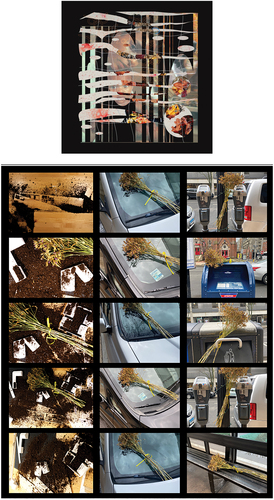

Both iterations of the course opened with the Layering & Weaving module, which involved a narrative-object created from found material. The Gee’s Bend quilters of rural AlabamaFootnote9 () were championed as proponents of an emergent episteme of entirely different ethics—“messy” and intuitive, “bottom-up” means of making and thinking, finding value in coauthorship, and care. These early days of the semester proved to be an effective entry point to our decolonial questioning of the canon. Weaving and quilting, for example, were not simply aestheticized as formal strategies, but were also positioned as ways of working, producing knowledge, and acts of rhetorical transmission.Footnote10 The Gee’s Bend quilts were juxtaposed with other artifacts of the Black tradition such as the ring shout, a ritual largely predicated on call-and-response, to highlight their space-making, space-taking, and architectural potential ( and ). The accompanying exercise for this model, “Recombinant Quilt,” embraced the discrepancies between the schools’ schedules by employing an asynchronous, exquisite corpse approach to collage to produce a digital album cover ().

Figure 1. African American quilts in the vicinity of the Alabama River (possibly Gee’s Bend), Wilcox County, Alabama. Photograph attributed to Edith Morgan, circa 1900. Image courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Figure 4. Examples of student work from Fugitive Practice seminar 2022. (Above) Recombinant Quilt/Layering & Weaving exercise, Rondela Spooner, Barbara Nasila, Mike Connor. (Below) Tagging, Saba Salekford, Gabriel Moyer-Perez, Ethan Chiang, and David Walker.

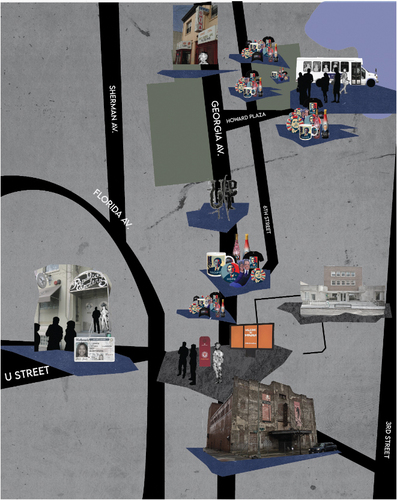

Other subsequent modules were similarly cumulative, and wove together topics and tropes concerning cartography, navigation, and marking at the urban and regional scale. The Marronage module posed another framework for understanding the spatial performance of “outsidership,” both within and without the colonial landscape. This was borne out in third and fourth exercises, which encompassed “tagging” and “harboring” as legitimate rhetorical and spatial devices. Cripwalking and graffiti, for example, were discussed without concern for their apparent “legality,” while acknowledging their deftness in transcribing markers of identity. The “Harboring” exercise invited students to create spatial and aesthetic systems to allow for diverse bodies to rest in various public spaces on campus, connecting to histories of the visibility of marginalized peoples’ leisure being itself a transgressive act. These more quotidian forms of space-taking and territorial sovereignty were intended to illustrate the pervasiveness of resistance, and the ever-present need for networks of freedom and safety ( and ). The final exercise, titled “Countermapping,” involved creating subject-driven, psychogeographic ways of knowing the landscape and city (). Students generated nontraditional documents to capture privileged layers and readings of territory that resist fixed and hegemonic mapping logics. The semester concluded with the Urbanism & Ephemerality module, which examined Black spatial imaginaries, with a focus on the milieu of “micro-marronage”—as coined in Fabienne Kanor’s novel HumusFootnote11—and behaviors that are often frowned upon or seen as less valid ways of occupying space. The speakeasy and the juke joint, among others, are templates for imagining architectures and infrastructures of collective survival, often in the urban context. We emphasized, however, that many of these tropes, such as the hush harbor,12 have extraurban and rural origins or analogues.

Figure 5. Student work from Fugitive Practice seminar 2021, “Marronage/Harboring” exercise, Bria Miller, Kenia Hale, Ivy Li.

Figure 6. “Rest Up at Yale,” “Marronage/Harboring” exercise, Chinaedu Nwadibia, Daud Aud, Josh Greene, student project, Fugitive Practice seminar, 2021.

Figure 7. “Old Howard,” “Countermapping” exercise, Chinaedu Nwadibia, Ivy Li, Bria Miller, Jenna Greer, student project, Fugitive Practice seminar, 2021.

When gathered in this way, these fugitive practices can be understood as a profound legacy of Black and Indigenous spatial paradigms that were created as means of care, safety, and refusal. Moreover, they are strategies of challenging the prevalence of Enlightenment-era principles and Eurocentric notions of order, control, and aesthetics. The value of these fugitive practices is that they necessarily fall outside of what is blindly taught, expected, and valorized in the academy.

The array of methods posed in “Fugitive Practice” are one step in destabilizing the institutional contexts, aims, values, and canon of design education. The students in “Fugitive Practice” grappled with the tension between our aspirations for gracious and generous pedagogies and the stubborn recalcitrance of existing institutional traditions. In both offerings of the course, white students were in the minority—a first for many in the mostly Black and Brown cohort. As we collectively reflected with students at the end of the semester, we sensed excitement by many, and a lingering skepticism of some, regarding the relevance of our course’s relationship to other coursework and learning. Affirming and affirmative nods during lectures, for example, about Black hair braiding were paired by uncertain questions about how this fits into conventional contexts of practice and licensure.

These frictions are perhaps the most promising aspect of “Fugitive Practice,” as we ultimately saw the course as an invitation for the students to reimagine, redesign and re-world their relationships to architecture—architectural education certainly, and possibly even practice. Perhaps these discussions should shape the contours of the reparations project. What imaginaries can emerge if marginalized students are empowered to see themselves in their work? What new systems of care and maintenance would we see? What new models of authorship and representation might be envisioned? Courses like ours are establishing new precedents that demonstrate how we might reorient disciplinary references and methods (the “what”), and demand a rethinking of both the content and the container of design pedagogy (the “how”). We insist on the possibility of a fuller, more holistic discipline that is more equipped to engage the multiplicity of populations and landscapes it serves. This is Fugitive Practice.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jerome W. Haferd

Jerome W. Haferd is an architect, urban designer, and educator based in Harlem, New York and the Hudson Valley. He is principal of Jerome Haferd, RA and cofounder of the award-winning practice BRANDT: HAFERD. Haferd is an assistant professor of architecture at City College’s Spitzer School of Architecture, affiliated faculty at Columbia and Yale Universities and a core initiator of Dark Matter U. His work critically engages with historically marginalized subjects, built environments, and nonhegemonic histories to unlock new imaginaries for architecture and urbanism. Recent creative practice has been exhibited at the 2022 Lisbon Triennale, the Park Avenue Armory, and the Center for Architecture New York.

Curry J. Hackett

Curry J. Hackett is a transdisciplinary designer, public artist, and educator. His independent design practice, Wayside, looks to underrecognized narratives to inform meaningful public art and critical research. Hackett’s ongoing research project, titled Drylongso, explores the intersections of Blackness, geography, land, and plants. He has taught at the University of Tennessee–Knoxville, Howard University, City College of New York, Carleton University, and Yale University, and is a core member of Dark Matter U. In 2022, Hackett was named as an inaugural member of the Journal of Architecture Education’s inaugural fellowship class for his proposal “Imaging the Black Landscape.” He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Architecture in Urban Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Notes

1 See Curry J. Hackett’s ongoing research project Drylongso: An Ode to the Southern Black Landscape (self-published via Soundcloud, 2021), which consists of a series of recorded phone conversations with his family who grew up on, or in close proximity to, his family-owned farmland in Prince Edward County. Many of these mention their experiences of the school closure in Prince Edward, and the mechanisms that the Black community deployed to effectuate education for their youth. These can be found online at https://soundcloud.com/curryhackett/sets/drylongso-an-ode-to-the-southern-black-landscape. (Conversations with Penny, Bernetta, and Claudette specifically mention the closing.)

2 See Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019). Dark Study is an experimental program centered on art that was started in 2020. See www.darkmatteru.org.

3 Dark Matter U (DMU), a primarily BIPOC-led counter-institutional network made up of built environment academics and professionals that formed in the wake of the BLM protests of 2020. DMU writes specifically on this in their essay “Collective Pedagogies” in the “Pedagogies for a Broken World” issue of the Journal of Architecture Education. See also www.darkmatteruniversity.com.

4 Design As Protest (DAP) is a collective of designers mobilizing strategies to dismantle the privilege and power structures that use architecture and design as tools of oppression. See Lisa C. Henry, Tonia Sing Chi, Shawhin Roudbari, and Bz Zhang on behalf of Dark Matter University, “Unseen Matters: Emerging Counter-Institutional Pedagogies,” in Journal of Architectural Education Vol.76, Issue 2 (Fall 2022: “Pedagogies for a Broken World”), 26-28. See also www.darkmatteruniversity.com.

5 These newer iterations build upon work to redress the classroom envisioned throughout the twentieth century by educators such as Fred Moten and Stefano Harney; see The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (New York: Autonomedia and Minor Compositions. 2013), Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro (Lanham: Dancing Unicorn Books, 2017 [1933]), bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (London: Routledge, 1994), and others.

6 While plantations dominated the landscape in the Americas, resistance from enslaved peoples was constant. Escape from the plantation gave way to the establishment of hinterland communities where creolized religious customs, secrets, and relative freedom could be enjoyed. The colonial French and Spanish coined this itinerant act as marronage, likely derived from the Spanish “marron,” meaning wild or feral (especially in reference to hogs).

7 Jarvis R. Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Harvard University Press, 2021). In the book, Givens uses this term and highlights the ways Black folks historically have educated themselves, often in clandestine fashion and at great risk.

8 The Gee’s Bend quilters were a community of Black women in rural Alabama that became known for the sophistication of their quilt patterns, made from scrap fabric, old clothing, and feed sacks. Their collage-like appearance and orthogonal geometries have possibly predated more celebrated 20th century figures such as Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee. See K. Michael, “Art Review; Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters,” New York Times, November 29, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/29/arts/art-review-jazzy-geometry-cool-quilters.html.

9 See Vanessa Kraemer Sohan, “‘But a Quilt Is More’: Recontextualizing the Discourse(s) of the Gee’s Bend Quilts,” College English 77:4 (2015): 294–316, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24240050. Sohan frames the needlework of the Gee’s Bend quilters as a Black feminist rhetorical practice, and a valid alternative to the lexical form of writing.

10 See Fabienne Kanor, Humus (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2020).

11 An architectural artifact of marronage, the hush harbor (also “bush arbor” or “hush arbor”) was an informal structure constructed of brush and small branches to obscure secret gatherings and facilitate escape from the plantation landscape. Hush harbors often hosted religious activity, and can be considered a precursor to the current-day Black church.