Abstract

The 2018–2023 architectural preservation process of a historic Black church in Massachusetts demonstrates a set of socio-architectural tactics identified as guerrilla preservation, or small maneuvers in pursuit of exuberance. These are shown to be both necessary in dealing with existing structures of power, property, and funding and also necessary in responsibly unpacking difficult layers of history produced by racial capitalism and colonialism. Historical contexts of the building and its inhabitants, the historical context of the term “guerrilla,” and architectural legacies of Black vernacular architecture in New England demonstrate that smaller tactics of preservation and exuberant expression contain potential to rupture the social matrix of the colonial-capitalist value system in the present.

By 1910 there were nine Black churches near Central Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A historical survey reveals a common thread about their origins since the late nineteenth century; Black communities were tired of politely waiting and being denied participation in religious organization, so they left to find or establish their own spaces. In bigger, older churches, people of color were relegated to the rearmost pews, which were often painted black in contrast to all the othersFootnote1. These new buildings were built quickly and cheaply; structural schemes were taken from pattern books and their turned or band-sawn wood details were bought at low cost from component production yards. They were always built in neighborhood interiors, rather than on main roads, and thus had to make the best of small and constrained sites. Usable spaces were stacked over multiple floors in unlikely ways. Entry sequences were often irregular. These buildings were improvised, adapted, and strategically crafted—they were built with guerrilla tactics. In the context of twenty-first century architectural and urban paradigms—intense gentrification, property flipping, and landlording—these types of buildings call for guerrilla tactics with respect to their preservation and reparation.

The term ‘guerrilla’ is a Spanish word that emerged in 1808 during Spain’s national struggle against French imperial invasionFootnote2. The word referenced small combat maneuvers, or wars fought through stealthy, shrewd, and calculated tactics. The birth of guerrilla maneuvers, however, actually occurred in the colonial world over the course of the preceding century. During the eighteenth century, as plantations reached unprecedented production intensities, enslaved and colonized peoples developed new methods for organized resistance, fugitivity, hidden movement through bushland and mountain terrain, subterfuge, and networks of secret communication. “Conspiracies” and “rebellions,” as the colonizers termed these maneuvers, spread across Caribbean archipelagos and in places such as Haiti (Saint Domingue) and JamaicaFootnote3. Only later did “guerrilla war” arise in Europe as an echo of the colonial worldFootnote4. During this era of mounting rebellions across the plantation Americas, small groups of partisans, confronted by massive colonial force, maneuvered to sabotage the reigning order, or to rupture the dominant logistics of imperial conquest. As Black Studies scholars point out, enslaved and Maroon peoples performed futuristic acts of liberation using their guerrilla repertoires. Through their collective action they created new temporalities that sabotaged the oppressive schedule of colonial timeFootnote5.

This writing reflects on reparations struggles, as they manifest at and around a small Black church—St. Augustine’s African Orthodox Church—in Cambridge, Massachusetts ( and ). We define this effort as a series of guerrilla maneuvers, led from below by those who seek to disrupt and sabotage the present-day regime of racial capitalism. These are “small ‘r’ reparations”—ongoing, everyday, community-based, processual ways of sabotaging racial capitalism through strategic maneuvers of care and attention. By reckoning with and tending to Black survivals and the continuities of Black exuberance lodged here, we disrupt the gentrifying disavowals and exclusions against which the Church and its members have long contendedFootnote6. These exclusions and disavowals, rooted in the city’s history, social policies, and in the everyday attitudes of high-income neighbors, places St. Augustine’s in a position of precarity in an extractive property market that seeks to homogenize spaces of common use into enclosures of private wealth; a process that is rooted in an infrastructural economy of exchange that emerged from the historical legacies of slavery, racism, colonialism, and racial capitalismFootnote7.

Figure 1. A view of St. Augustine’s African Orthodox Church as it was before renovations began in 2018. Photograph by Christopher Hail, 1985. Cambridge Historical Commission collections.

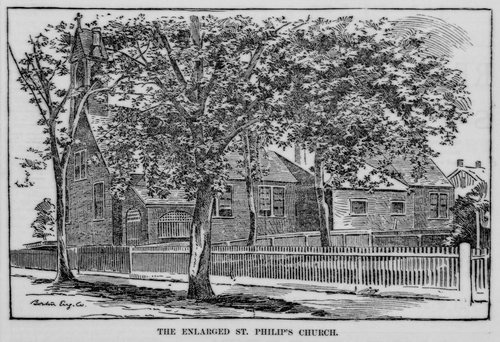

Figure 2. Artist’s rendering of the church from an 1888 issue of The Cambridge Chronicle. St. Augustine’s was formerly known as St. Philip’s. The church was originally built in 1886, but just two years later it was enlarged by sawing the building in half, moving the rear half back to the rear of the parcel, and filling in more nave length between the two split halves. Public domain image.

These guerrilla maneuvers can be seen during a 2018–2023 architectural preservation project at St. Augustine’s that seeks to sabotage and transform this infrastructural exchange. The “small ‘r’ reparations” work of this project were both embodied and are material and symbolic practices, where time is spent to accompany, tend to, care for, and treasure a historic Black church community in a system that has repeatedly classified their interests as less worthy of safeguarding than those of the expanding, gentrifying majority white population. The progress by “Man,” as Sylvia Wynter explains, relies on assigning Black and Brown communities to intensifying experiences of “dysselection”: disregard, exclusion, and precariousnessFootnote8. The reparative investment of care involved in tending to the administrative well-being, architectural integrity, and the safety of Black life at St. Augustine’s ruptures the surrounding racial capitalist grid. These moments of rupture allow for the wider gentrifying neighborhood community to see beyond static horizons of racial disavowal, and to find entry points to transforming a system of extractive values into shared wealth, equity, and historical reparation.

The work of reclaiming St. Augustine’s demonstrates that reparation is not about “revitalizing,” “reactivating,” or “fixing” a Black cultural institution; rather, it is the work of rupturing, and then transforming and repairing, the social matrix and colonialist-capitalist value system surrounding the sites of Black survival.

Since 2018, we—an architect and historian who live near St. Augustine’s—have been working with the remaining elderly parishioners of St. Augustine’s African Orthodox Church who have been caring for the building as a living social space, to maintain its stories, and to help enact its possible future. It was essential for us to make decisions with and alongside the parishioners as primary stakeholders. And our rapport with the parishioners grew out of a long-term practice of affiliation and genuine friendship. The project team has been joined by more neighbors, researchers, artists, healers, and activists to learn from the Black exuberance of St. Augustine’s, rooted in a rich African Caribbean American history. To this end, we formed a new resident nonprofit, Black History in Action for Cambridgeport, with reparation, research, art, and education as its mission.

The first—and most obvious—thing to be done to St. Augustine’s African Orthodox Church was to replace the roof. In 2018, sunlight could be seen through cracks in the exposed wood ceiling (). On rainy days, buckets were used to catch the water that leaked into the church. This small English countryside chapel-style church, in a historically Black industrial working-class neighborhood of Cambridge, Massachusetts, was beginning to stand out because nearly all nearby buildings had been renovated or replaced. Its 1970s woodgrain-stamped asphalt shingles were the last of their kind in the neighborhood. Coordinated by our newly formed nonprofit, an informal assemblage of people began the work of this “small ‘r’ reparation.” In the process, it became necessary to contend with the historical legacy building, and with the broken social bonds that resulted from systemic racism, exclusion, and disregard. Deferred maintenance at St. Augustine’s, pertaining to the physical state of the building as well as its social bonds, reputation, and the status of its deed and governance, actually represented the larger—and disavowed—racial disrepair of the surrounding gentrifying neighborhood.

Figure 3. A view up at the ceiling during initial emergency renovations showing steel reinforcement brackets and lateral tie rods that were added for structural stability, and also showing sunlight shining through cracks and holes in the roof of the church. Photograph by Gabriel Cira.

St. Augustine’s appearance had not changed much since the 1970s when the asphalt wall shingles were installed as a stopgap measure to patch the decaying shingles beneath. It was not “ruined,” but rather stood outside the “market time” of the capitalist real estate economy. St. Augustine’s existed in a stasis or abeyance, outside the colonial-capitalist processes where properties are bought and extractively flipped. From 1955 to 1970, members of the neighborhood vigorously resisted the construction of the infamous “Inner Belt” expressway, an urban connector highway that would have slashed through Cambridge. A 1966 issue of The Architectural Forum highlighted a project by The Architects Collaborative to embroider the would-be highway with housing blocksFootnote9. The article included a photo of St. Augustine’s, serving as an example of the “crowded-together and obsolete” architecture directly in the highway’s path. Strong community protests and, ultimately, a moratorium on highway-building within the outer urban ring road, Route 128, stopped the proposed highway project.

St. Augustine’s is known as a “pro-cathedral,” as it was the home church of the first bishop of the African Orthodox Church organization, George Alexander McGuire. African Orthodox Church practice shares much in common with the Anglican Episcopalian liturgical rite, but McGuire found no Episcopal or Catholic bishops who would confer apostolic succession on a Black man. Finally in 1921, the rogue Syrian Orthodox Bishop René Vilatte consecrated McGuire, who was known as a tireless educator, community leader, and believer in the socially transformative power of autonomous religion for Black people. McGuire had been a close associate of Marcus Garvey since 1918, and guided the African Orthodox Church throughout the United States, and in parts of the Caribbean and Africa as the religious wing of Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement. Members of St. Augustine’s from this heyday saved as keepsakes the tickets they bought for the steamship that was to take them on the storied “Back to Africa” voyage.

A church can be a tricky place. It is not subject to property tax and does not participate in the corresponding “market time” of the real estate economy, yet sits on land that could do so. The power of the church is also its weakness within the framework of extractivist real estate value-creation and maintenance. The “rot” and “ruin” we uncover at St. Augustine’s is only an indication of the otherness of this space—for too long it has been doing something other than creating “value” that is productive capitalist value. What appears as “ruin” is in effect a manifestation of survival and of the staying power of a place that works against the schedule of real estate capitalism. As a place seemingly out of time—an unlikely specter from another era—the epistemic ghosts of racism, policing, and gentrification are tangible. In other words, time itself “is out of joint” around St. Augustine’s. Ghosts, as Avery Gordon brilliantly explains in her study of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, are sociological indicators. They point to open secrets, the unconsidered known, and the silent confessions that disturb pretenses of normalcy, respectability, and amity within a social field constituted through ongoing racial, colonial, and gendered violenceFootnote10. Ghosts, according to Gordon, call the ones they haunt to reckon with the sites and substance of disavowal. A haunted house is only the aperture through which the social haunting of its surrounding neighborhood and social order can be indicated or pointed out.

The racial ghosts arising from legacies of racism, policing, and gentrification in Cambridgeport seemed to reenter the scene around St. Augustine’s over the course of the 2018–2023 preservation project. Working with the complexities of existing buildings is always a challenge to standard architect-owner-contractor procedures. At St. Augustine’s, layers of asphalt shingles indiscriminately covered over problems of all types: roof leak lines, splitting structural brackets, incomplete foundation walls, and rot. These problems only became apparent when the asphalt shingles and other quick-patch fixes were removed. Informed by scholarship on Black place-making, is not difficult to draw an analogy between these issues and the slipshod cultural layers of racial disavowal that obscure the need for reparation of historical damage done to Black social fabricFootnote11. Like our guerrilla historic preservation operations, with matching grants and donated labor, “small reparation” takes time, peeling back the layers of social disregard and reactive defense in order to first even grasp the extent of the social repair needed ().

Figure 4. Brothers Charles “Kit” Eccles and Edward “Ned” Eccles, members of the church vestry; Tiago “Dell” Silva, a contractor; and a pit bull, “Monk,” on the construction site in January 2019. Photograph by Gabriel Cira.

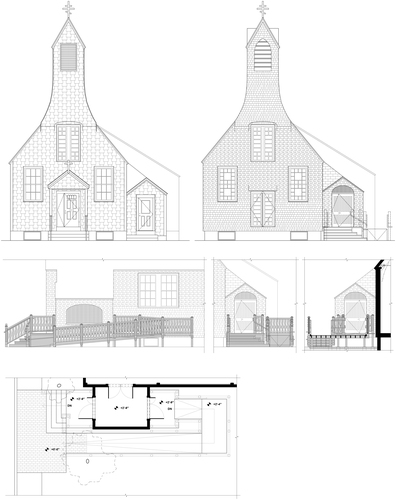

The 2018–2023 preservation project reactivated the building’s original entry sequence through the vestibule to the right side of the building’s front facade ( and ). Off-axis entry is a vernacular hallmark of urban churches on constrained sites. An 1888 newspaper engraving shows an excellent depiction of the original condition, although details are not entirely clear. In 2022, the side entry vestibule structure allowed for both an outdoor ramp and stair to be routed through it. Accessibility ramps, especially on constrained sites, typically route to a rear entry to accomplish necessary code-required slope and clearances. The side vestibule enables a more graceful integration into St. Augustine’s. In the future, ramps on historical buildings may be viewed as a product of a post-ADA era, and will struggle to escape historicization as what Jay Dolmage has categorized as a “retrofit,” or an added-on afterthought that is emblematic of nonintegrated accessibility planningFootnote12. Given this, the architectural detailing of the side vestibule and exterior entry features serves as a prism through which historical questions of reparation, restoration, and style are addressed as a distinct break from original conditions.

Figure 5. A view of the side vestibule after asphalt shingle siding had been partially stripped, revealing original window shapes boarded over, and original 1886 cedar shingle details. Photograph by Kris Manjapra.

Figure 6. A view of the side vestibule after asphalt shingle siding had been partially stripped, revealing original window shapes boarded over, and original 1886 cedar shingle details. Photograph by Kris Manjapra.

The conservation work utilizes a repeated 2D cutout wiggle shape derived from the joyful and inexpensive detailing of 1880s carpenter gothic, which used new steam-powered bandsaws to expressive, exuberant ends. Some of the most notable results from that period are the vernacular “gingerbread” drip vergeboard of the Black summer vacation-cum-religious enclave of Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, and the serpentine cutouts on witty and whimsical divans or tiered shelves made by Thomas Day, a renowned Black carpenter and furniture maker. The original architect of St. Augustine’s, Robert Slack, often used simplified Gothic fairing to integrate architectural parts in his search for a humble New England gothic style. While the overall new design of the side vestibule and entry sequence is based on the 1888 engraving, the wiggle shape and the other smaller wood details are geared toward a new architectural identity—one that balances external historical touchstones and a new exuberance of Black History in Action for Cambridgeport ( and ).

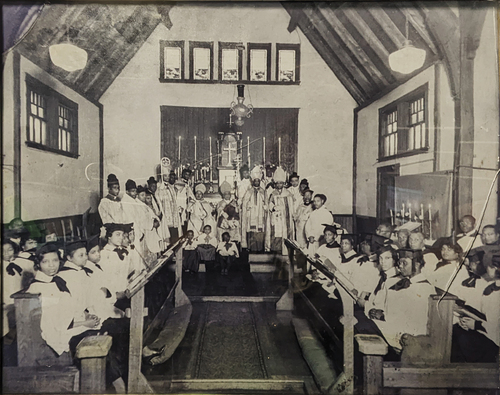

Figure 7. A circa 1930 photograph of the church sanctuary with clergy and choir. Photograph courtesy of St. Augustine’s African Orthodox Church.

Figure 8. Architectural preservation drawings of St. Augustine’s: (top) the front facade of the church, both as it existed before renovation and as it will exist post-renovation; (middle) three elevation views of the architectural detailing of the renovated side entry vestibule, with new ramp, stairs, windows, doors, and siding; (bottom) a detailed plan view corresponding to the elevations. The design of the architectural elements shown in these drawings is based on the 1888 newspaper engraving of the church (see ), although details are lacking in this historic depiction and much is left to the contemporary imagination. Drawings courtesy of Gabriel Cira.

Guerrilla preservation as a maneuver of “small ‘r’ reparation,” by necessity, deals with the ghosts of disrepair and rot, approaching them with small, sustained, grassroots acts of healing. On a larger scale, guerrilla preservation tracks and nurtures those elements, however small, that carry the spirit of exuberance and community from deeper histories of a space. Family recipes for the church basement Glenwood stove, or hand painted marbleization on glass panes for color effects, or the hymnals and the sung musical repertoire, carry these threads of continuity. These examples, and the architectural strategies that favor them, focus on something more than the survival of cultural inheritances. We suggest that exuberance, instead of survival, revival, or adaptation, is an ambition of guerilla preservation. Exuberance is not only about the continuation of lifeways from past to present. Exuberance is also not about revival, or the restarting of former lifeways in the present. We see exuberance as the capacity for life to bring forth a nascent future within present conditions—to create what is, as yet, new, recombinant, and unanticipated. Preservation cannot accomplish this alone, as it tends toward “adaptive reuse” with the logics of postindustrial cultural appropriationFootnote13. Rather than adapting spaces and places to dominant spatial-economical paradigms of the present, guerrilla preservation takes advantage of spatial energies rooted in past usage and historical accumulation that exude futuristic possibilities. Here, a neighborhood’s racial ghosts and their instructive hauntings can point to sites where the strategies of Black life and creativity operate below and beyond the radar of the racial-colonial order.

A Black church such as St. Augustine’s served as a crucial nondomestic and nonwork space for the formation and exultation of a social body in the face of oppression (). Guerrilla preservation sees this condition as the basis for a new, exuberant, Black cultural space. Within a gentrified—and secularized—urban condition, such a space will continue to exist on its own time, and for many will remain hidden. “The undercommons, its maroons, are always at war, always in hiding,”Footnote14 note Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, as they make a broader case for fugitivity, but say this as they make a broader case for fugitivity as creativity. Exuberance is this condition: the becoming-social of a space of historic struggle in an era when space itself—or the upkeep of space despite great external pressures—is a struggle.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gabriel Cira

Gabriel Cira is a licensed architect based in Massachusetts. He is a professor in the history of art at MassArt, where he teaches the longstanding Architecture of Boston course and other architecture and art history seminars. Cira’s professional practice and research work focus on historic preservation, vernacular/popular histories, ecological design, accessibility and preservation, and infrastructure history.

Kris Manjapra

Kris Manjapra is a professor of history at Tufts University, specializing in Global Black Studies. He is the author of four monographs, including Black Ghost of Empire: The Failure of Emancipation and the Long Death of Slavery (Scribner 2022). He cofounded the reparative justice local nonprofit, Black History in Action, devoted to the struggle against gentrification in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts.

Notes

1 Noel Leo Erskine, Plantation Church: How African American Religion Was Born in Caribbean Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

2 Carl Schmitt, Theory of the Partisan, trans. G. L. Ulmen (New York: Telos Press, 2007).

3 The vast literature on maroonage is brilliantly surveyed and advanced by two recent works, Malcom Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology (New York: Wiley, 2022), and Neil Roberts, Freedom as Marronage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). One of the greatest maroon conspiracies was the movement led by Françoise Makandal in Haiti in 1758. And one of the greatest “rebellions” was led by Tacky in Jamaica in the 1760s. See Elizabeth Dillon, “Makandal and Pandemic Knowledge: Literature, Fetish, and Health in the Plantationocene,” American Literature 92:4 (2020): 723–35, and Vincent Brown, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War (Cambridge: The Belknap Press, 2020).

4 Michael Craton, Testing the Chains (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

5 Katherine McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” Small Axe 17:3 (2013): 1–15; Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

6 Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, or a Poetics of Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

7 Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2000).

8 “Dysselected” is the term that philosopher Sylvia Wynter uses. See “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” The New Centennial Review 3:3 (2003): 257–337.

9 John Morris Dixon, “Last Hitch in the Inner Belt,” The Architectural Forum, May 1966: 68–71.

10 Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Hauntings and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), xvi.

11 “The extensive scholarship on Black place-making includes important contributions such as Ángel David Nieves and Leslie M. Alexander eds., “We Shall Independent Be”: African American Place Making and the Struggle to Claim Space in the United States (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2008); Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Adrian Woods eds., Black Geographies and the Politics of Space (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2007); Andrea Roberts, “When Does It Become Social Justice? Thoughts on Intersectional Preservation Practice” National Trust for Historic Preservation: Preservation Leadership Forum, July 20, 2017, https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/special-contributor/2017/07/20/when-does-it-become-social-justice-thoughts-on-intersectional-preservation-practice.

12 Jay Dolmage, “From Steep Steps to Retrofit to Universal Design” in Disability, Space, Architecture, ed. J. Boys (New York: Routledge, 2017), 102–13.

13 Hsuan Hsu, “Of Mimicry and Hipsters,” in Camouflage Cultures, ed. A. Elias, R. H. N. Tsoutas (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2015), 171–82.

14 Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Brooklyn: Minor Compositions, 2013), 30.