Opening

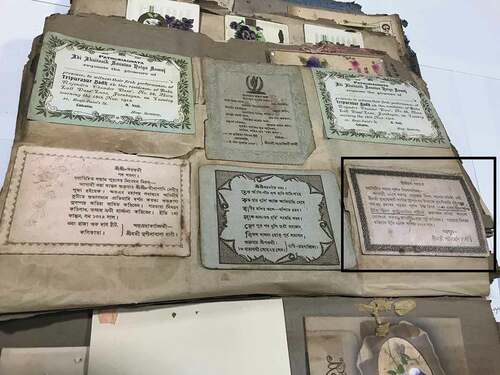

Touching the material remains of an illicit past, remnants of a forbidden zone, turns out to be a thrilling visceral experience.Footnote1 The fragile, bookworm-eaten pages of a scrapbook can barely contain its residents as I open and inspect it. With every turn of a page, invitations, cards and food menus tumble out, unmoored with the fading of glue. It is April 2018. Kolkata outside is sticky and heaving under the afternoon glare, bracing itself for a heat wave. But here, inside the air-conditioned cool of the JBMRC archives,Footnote2 some of Calcutta’s secrets come unstuck.Footnote3 A scrapbook heaving with a courtesan’s intimate memories is under a scholar’s glare.

The opening of this scrapbook is an act replete with multiple meanings. It is the opening of a space that provides us access, without granting it, to lives of women that we are normally not allowed to know. It is the opening of a gap in our knowledge of how some of those women scripted their lives in the early twentieth century. It is the opening of a very private archive which, at the time of this article’s writing, has not been studied by any other scholar, even though the document now rests in a public archive.Footnote4 This opening is bound up intimately with the vexed ethics of ‘outing’ certain lives, even when we, the raiders of lost or hidden worlds, come armed with the license and privilege of academic freedom. It necessitates, too, the ‘outing’ of my own position as a global North-residing scholar with Bengali/Indian/Hindu upper caste affiliations vis-a-vis the subjects of this study, those performers of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Bengal and contemporary Kolkata, who have historically been discriminated against by the colonial formation of ‘nautch’ and the subsequent anti-nautch clean-up operation led by Indian upper caste reformists.Footnote5

This article argues that British colonialism operated as a careful choreography of Indian subject populations into manageable formations, turning ‘nautch’ dancers into expendable subjects through legal acts. Yet, by following the hitherto undocumented social lives of some performers from the red-light district of the colonial city of Calcutta, I argue that heteronormative colonial archives are queered by under-the-radar counter-choreographies of Bengali courtesan practices. Through its analysis of pages of a rare scrapbook belonging to the Bengali courtesan Indubala Dasi (also referred to as Indubala Devi, 1899–1984)Footnote6 – the first Bengali artist to record with The Gramophone Company and a tireless crusader for the rights of sex-workers – the article mobilises a significant visual archive to provide a glimpse of the gendered and racialized lives of Calcutta’s courtesans, and the subversive anti-patriarchal acts they performed. Indubala’s scrapbook contains a collection of personal Christmas and New Year’s Eve greeting cards, invitations to very public theatre premieres in the city, and very private ‘flower’ ceremonies amongst her courtesan network. The scrapbook therefore becomes an invaluable window to the private world of Bengal’s female courtesans in the closing years of the British Empire in India (the early 1900s to the 1940s) and during the unfolding of a newly independent Indian nation state (post-1947).

But the article also wishes to reflect critically on the methodological practices that we as historian-voyeurs engage with, that enable us to lean in through the open windows that personal archives present us with in order to get a good look inside the bedrooms of history. It trains the spotlight on our role and responsibility (as scholars occupying positions of relative privilege through our class and caste markers) in narrating illicit lives and practices, and the ethical implications of outing Indubala and her red-light district colleagues. What are the problems of such ventriloquizing acts for contemporary historical researchers in the field of dance and performance studies and how do they stack up against the knowledge gained from a project such as this?Footnote7 What colonial scripts of original discoveries, of loss and recuperation, of authentic pasts, of what Anjali Arondekar calls ‘melancholic historicism’, do we continue to rehearse when claiming an archival breakthrough?Footnote8 What decolonial gestures can we set in motion to counter-choreograph the role that history has assigned to some bodies in the colonial archives? These questions frame, prompt and guide the analyses that follow.

In Part One, ‘Calcutta’s Contagious Dancing’, the article offers a brief look at the cultural history of prostitution in the first British colonial capital of India.Footnote9 It notices colonialism as a strategic choreography in which city zones and citizens are demarcated along trade lines, where dance succumbs to the terror of contagion and vice, and ‘nautch’ dancers are sacrificed by the colonial state for the health of its polis. Part Two, ‘My Name is Indubala’ offers a brief biography of Calcutta’s celebrated courtesan Indubala Dasi, her life as a singer, actress and performer, and her human rights activism in Calcutta’s red-light district. Part Three, ‘Scrappy Evidence: Pleasure, Indulgence and Intimacy in Indubala’s Scrapbook’ offers the very first analysis of the contents of her scrapbook, noting how the carefully curated documents within it reveal the quiet yet dynamic inner lives of Bengali courtesans. Finally, in ‘Closing’, the article notices the continued legacy of Indubala’s activism in the choreographic work of Komal Gandhar, a collective of cis and transgendered sex workers based in the Sonagachi red light district of present-day Kolkata. Throughout the article, the writing oscillates between contemporary representations of Kolkata today and historical material on the colonial city, to notice how archival remains and current circulations of embodied knowledge move in tandem.

Part One: Calcutta’s Contagious Dancing

Of all Indian metropolitan cities, Kolkata most satisfies the global north’s desire for poverty tourism. Its international appeal to a neo-imperial benevolent gaze is exemplified by the success of two landmark international productions for the screen, which catapulted the city to global attention: the French-British film City of Joy (1992) and the Indian-US documentary film Born into Brothels (2004).Footnote10 Born into Brothels, while occupying the genre of real-life documentary, follows the fictional City of Joy’s ‘white messiah’ narrative, focusing on ‘saving’ the children of Kolkata’s sex-workers in Sonagachi, the largest red-light district in Asia. Written and directed by Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman, the documentary arms the children of sex workers with cameras when their mothers prove to be difficult subjects to capture. Briski becomes the white saviour of underprivileged children who turn into Spivakian ‘native informants’,Footnote11 and the camera becomes a tool for the children’s escape from a hopeless world of sex work. The innumerable international awards for this documentary, topped by the 2005 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, has ensured that the colonial model of white paternalism remains firmly in place. In fact, I view these productions as being symptomatic of whiteness gagging for a global south poverty narrative. I use ‘gagging’ intentionally, because the unchanged status quo in these narratives – the power of the global north to rescue the helpless global south – seems to offer white spectatorship both pleasure (in the knowledge that they are better off) and disgust (to see how the poor live in filth, both morally and socio-economically).

My intention in this article is to highlight gestures from the global south that resist or disturb such a paternalistic or benevolent gaze. It is worth noting that one of Born into Brothels’ most vociferous critics was the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC), a collective of approximately 65,000 female, male and transgender sex workers from across West Bengal based in Sonagachi, Kolkata. The organisation has been managed and run by sex workers since 1995, who have been tirelessly lobbying for the legal recognition of sex work in India. The DMSC’s critique of Born into Brothels was aimed at the complete absenting of local, on-the-ground activism such as their decriminalisation of sex work movement, or the STD/HIV Intervention Programme (also known as the Sonagachi Project) operating since 1999. The distilled message from documentaries such as Born into Brothels is that sex work is a vice that needs eradicating or overcoming. Sex-trafficking figures attached to India remain alarmingFootnote12 and the Indian government’s ‘Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill’ which passed the lower house of Parliament in July 2018 and was set to come into legal force, despite strong opposition from sex-workers’ collectives across the country including DMSC, further adds to the conflation of sex work (including consensual sex work) with crime.Footnote13

These contemporary debates on sex work, criminalisation of sex workers, and human rights in Kolkata and more broadly speaking in South Asia, may be situated in a long and complicated history of British colonial law-making and Indian nationalist reform movements. It is useful to access and outline that history through the practices of dancers, actresses and singers, a community that both fuelled colonial medico-moral discourse and were directly affected by legal and reform movements in colonial Calcutta. While there is now a critical mass of well-established scholarship on the impact of nineteenth-century and twentieth-century colonial law, Indian reform and revival movements on the practices of devadasis (temple dancers) in southern India (Amrit Srinivasan, Davesh Soneji), tawaifs in north India (Veena Oldenburg, Pallabi Chakravorty) maharis in Orissa (Frédérique Apffel-Marglin, Anurima Banerji) and illicit dancers (Anna Morcom) relatively less is published on communities of dancers and performers who were pushed underground in Calcutta due to the enforcement of colonial jurisprudence.Footnote14

A watershed moment in colonial law that most scholars of South Asian performance (including dance, music and theatre studies) deem crucial is the Contagious Diseases Act (CDA) of 1868, which was enforced in India to protect British soldiers from contracting venereal diseases. However, as Erica Wald reminds us, the CDA was shaped by repeated failures of earlier acts that preceded it.Footnote15 Wald outlines a history of relationships between European men and Indian native women beginning from the seventeenth century, the gradual decline in mixed-race marriages due to increasing hostility from evangelical missionaries towards corrupting natives, the colonial government’s fear of mixed-race progeny claiming financial or political rights, and the tacit encouragement of British soldiers to seek prostitution.Footnote16 With the expansion of British troops in India, the regulation of the health of soldiers was prioritised through the establishment of lal bazaars and the lock hospital systems. These were controlled zones where the regiment’s prostitutes were allowed to trade in transactional sex and could be detained and locked up in venereal diseases hospitals if suspected of being disease carriers. As historian Ratnabali Chatterjee’s study has found, after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, fear of contagion coupled with nervousness around anti-colonial resistance led to tighter controls over native women’s sexuality and 1860’s Indian Penal Code joined the Indian ‘prostitute’ with the criminal category – the prostitute came to embody ‘filth, vice, disease and rebellion’.Footnote17

The criminal prostitute in nineteenth century India turned into the most composite and nebulous of categories, folding within it women from different religious, caste and class backgrounds as well as embodying a wide range of literacy and artistic skills. Kunal Parker reminds us that within Anglo-Indian legal discourse, ‘prostitution’ operated as a highly opaque category, encompassing a range of activities from urban sex trade to any sexual activity that Hindu women engaged in outside marriage.Footnote18 Equally nebulous was the category of ‘nautch’ (the Anglicised blanket word for the Hindi and Bengali word ‘naach’ meaning dance) which gradually came to be conflated with prostitution, and therefore by law criminalised. Without repeating a very well-rehearsed narrative of how ‘nautch’ became the centre of fierce colonial and patriarchal debates on the hereditary dancer’s right to sexual partnerships or property,Footnote19 I wish to focus here on ‘nautch’ in the city of Calcutta and the ways in which it choreographed its survival around legal movements.

The Company period in India had begun with the British East India Company’s trading activities since 1608, and its rule in India from 1757 following victory at the Battle of Plassey. The power of governance shifted to the British Crown in 1858, with the city of Calcutta serving as the first capital of British India until 1911 (when the capital shifted to Delhi in northern India). Calcutta became the seat of British colonial power, a major trading port, and an important cultural magnet too for theatre, music and dance artists when the deposed and exiled king Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh (1822–1887) arrived in Calcutta from Lucknow in May 1856, bringing with him his family, courtiers and a retinue of dancers and musicians. His home and its neighbourhood in Metiabruz, Garden Reach in the outskirts of the city soon came to be known as ‘Chota Lucknow’ or Little Lucknow, turning into a hub of courtly culture.Footnote20 Calcutta would launch the stellar careers of many notable theatre, music and dance artists through both royal and commercial patronage, including the legendary singer/dancer Gauhar Jaan (1873–1930, who was first noticed in Wajid Ali Shah’s court), and the star of an increasingly significant commercial Bengali theatre scene, the actress Binodini Dasi (1862–1941).Footnote21 It is important to note that courtesans such as Gauhar Jaan occupied a relatively privileged social status in nineteenth to mid-twentieth century Bengal, when compared to Indian women in heteronormative social settings. Operating within the urban salon or kotha culture, unbounded by any one court or king and performing for a largely feudal/merchant class audience, courtesans of Gauhar Jaan’s ilk and calibre were neither dictated by nor operated within, the standard laws of conjugality that governed ordinary women’s lives.Footnote22

By the mid-nineteenth century, Calcutta had also turned into a river-port teeming with soliciting women who served a variety of clients, from the rural poor who had immigrated to the city, administrative clerks, British soldiers and sailors, to members of Bengal’s landed aristocracy and the noveau-riche, the latter popularly known as the ‘babus’.Footnote23 Clusters of brothels sprung up in various parts of the city, and by the 1860s Calcutta’s prostitutes were divided into seven categories, as mentioned in an official British report by a Health Officer Dr. C Fabre-Tonnerre.Footnote24 In this report, the first three categories of prostitutes are highlighted to be Hindu women of ‘high-caste’ or ‘good caste’ while the fourth category supposedly ‘consisted of dancing women, Hindoo or Mussulman, living singly or forming a kind of chummery … receiving visitors without distinction of creed or caste’.Footnote25 This vague taxonomy of prostitution (for phrases such as ‘good caste’ are extremely unspecific), in which dancing occupied a mid-tier of respectability, seemed to get reflected in the city’s zones, with certain areas of the metropolis classed as areas where high-caste prostitutes lived, and others where poorer prostitutes solicited.

In the architecture of the city of British Calcutta, zones of exclusion were formed, which divided the city’s residents according to race, wealth and class status. The colonial demarcation of the city into White Town and Black Town with the Army headquarters in Fort William is well established, but as Swati Chattopadhyay suggests, White and Black towns were not homogenous zonesFootnote26 – they rubbed against and seeped into each other constantly. ‘Nautch’ dancers and performers regularly negotiated these exclusion zones, their moving bodies crossing the borders of Victorian respectability and morality. In Representing Calcutta, Swati Chattopadhyay suggests that the colonial administration’s attempt was ‘to control the visibility of prostitutes in the landscape’ but their presence only seemed to ‘proliferate an indeterminacy, thwarting any possibility of enumerating the population accurately’.Footnote27

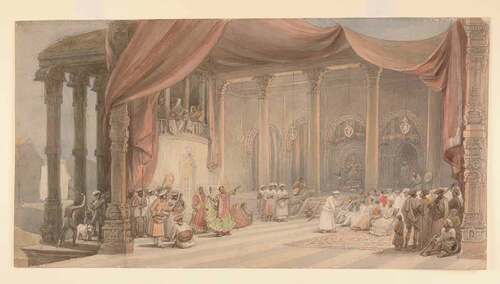

Visual evidence in the form of colonial paintings and local sketches attest to the existence of extravagant dance soirees and ‘nautch’ parties in Calcutta. For instance, Aishika Chakraborty discusses Bengal’s nineteenth-century dance scenes on the occasions of Durga Puja (the festival of goddess worship in the Autumn), Holi (the festival of colours in Spring) and official British functions such as the welcome party for the Prince of Wales’ 1876 visit to Calcutta.Footnote28 Many art works in the colonial visual archive of sketches and paintings capture ‘nautch’ dancing in expansive rooms and halls. Let us take for instance William Prinsep’s famous watercolour of dancers in Calcutta during Durga Puja (circa 1840), currently homed in the British Library archives. Here, the focal point of the viewer’s gaze is the female dancer, one hand holding up an edge of her pale green skirt which fans down to her feet, another arm raised in the air, her slightly tilted head and torso draped in a red dupatta (long scarf). Around her dance, other scenes unfold: servants bring trays to memsahibs in frilly Victorian gowns and sahibs in red and blue Company coats seated in the audience. Women and children lean over a balcony to watch the scene. A priest squats on the raised thakur dalan (prayer hall) where offerings have been placed in front of goddess Durga. But amidst this scene of entertainment, a violence is about to unfold in the left-hand corner of the painting. A goat is about to be slaughtered (See ).

Image 1. William Prinsep’s Durga Puja (circa 1840). Image courtesy of the British Library (Ref: WD4035)

I read this visual archival trace not so much as a static document of nineteenth century Calcutta or a snapshot of its dance and entertainment culture, but as a performance. The painting depicts a sacrifice that is just about to take place: the goat stands meekly as a bare-torsoed brown native in a dhoti, arm raised in the air and wielding an axe, is about to strike its neck. Another Indian native in turban, dhoti and kurta, calmly supervises the sacrifice. I read the ‘nautch’ scene and the sacrifice scene as two inextricably linked parts of the same performance. Here, the sacrificial goat and the ‘nautch’ dancer are twinned, native animal and human subjects who under colonial scrutiny and native complicity, must be killed in order to appease powerful guests (the goat must die literally, and the ‘nautch’ dancer metaphorically). The ‘nautch’ dancer becomes the killable body, the homo sacer, whose death protects the body and health of the population/citizenry and is therefore sanctioned by the sovereign powers invested in law.Footnote29 She is deemed unworthy of being the sacrificial scapegoat (of ritual/religious violence), and yet becomes the target of sovereign violence, included in the political as a form of exclusion and violated with impunity. In treating Prinsep’s painting as a performance of impending violence, I am proposing that we can look to the colonial visual archive as performative events, not just as documents that capture history. I therefore suggest that Prinsep’s painting performs colonial anxieties about native customs, contamination and harlotry.

Here, I move against Diana Taylor’s celebrated archive/repertoire theory where, despite best intentions to resist a binary, Taylor succumbs to an archive/repertoire divide when she suggests: ‘archival memory works across distance, over time and space’Footnote30 whereas ‘the repertoire, on the other hand, enacts embodied memory’ and ‘requires presence’.Footnote31 Rebecca Schneider, in her critique of Taylor’s theory, notes that Taylor ‘works to situate the repertoire as another kind of archive, rather than emphasizing the twin effort of situating the archive as another kind of performance’.Footnote32 It is precisely this move towards viewing archives as dynamic processes, acts, scripts and gestures that this study embraces in its analyses of the memories of Bengal’s courtesans. Prinsep’s painting, as a symptom of a creative colonial visual archive, feeds the white sahib’s terror of brown contagion. I am aware that my reading presents the ‘nautch’ dancer as an expendable victim in this colonial-era painting, her body falling prey to racial and nationalist violence. My turn to other native archives, such as Indubala’s scrapbook later on, presents a very different view of female subjectivity and agency within the ‘nautch’ world. But first, let us get the introductions out of the way.

Part Two: My Name is Indubala

14 December 2019: Finding Indubala’s house in Rambagan is not easy. I meet record collector Ashis Bhadra at Liberty Cinema and we make our way on foot to find Indubala’s house. We take a few wrong turns in a dizzying maze of narrow alleys, and end up asking for directions. People on the streets helpfully offer leads, and also some unsolicited advice: ‘dekhben, jayga ta khub ekta bhalo na’ (please watch out, the area is not very good), mutters someone. We locate the house eventually and are given a tour of two rooms by Pallab Ghosh, who is expecting us. He is the son of Pranab Ghosh who was Indubala’s adopted son. We gape at Indubala’s collection of rare coins framed on walls, her ivory collection in glass cabinets, her collection of dolls and miscellaneous objects in another cabinet, a huge custom-made hardwood wardrobe with the name ‘Indubala Dasi’ carved delicately in Bengali on its arch, an HMV gold gramophone disc, photographs of her mother, photographs from her acting career, and a harmonium gifted to her by the Gramophone Company with her name etched on it. These live alongside everyday objects and essentials belonging to Pallab Ghosh, who now lives in the rooms with his family. He says it has been several years since anyone tried to find Indubala’s house, that no one come around anymore.

Finding her on YouTube is easy. A simple search with ‘Indubala Devi’ yields a long list of voice recordings: Mor Ghumghore Ele Manohar (1931), Anjali Laho Mor (1936) … the list goes on. The songs are mostly accompanied by two or three grainy black-and – white images, such as the one here (See Image 2). In another photograph (available online but not reprinted here), she looks boldly at the camera, dressed in sari and statement jewellery, the fingers of one hand resting on her cheeks. On YouTube’s archives, then, Indubala’s presence and her music repertoire are well recorded. In scholarly publications, particularly in the English language, she is much less documented.Footnote33 The biography that follows is gleaned mainly from her Bengali biographer Badhan Sengupta’s work (1984), catalogues of music collectors and published interviews.Footnote34

This is a story where the worlds of circus, music, dance, theatre and film come together. Indubala’s mother, Rajbala was a trapeze artist in The Great Bengal Circus, founded in 1887 as Professor Bose’s Great Bengal Circus by Priyanath Bose (1865–1920). Priyanath’s brother Motilal Bose and Rajbala fall in love and marry, although the marriage is never accepted by the Bose family, more so because Motilal leaves his first wife for Rajbala. In 1899, Indubala is born to Rajbala and Motilal in Amritsar (Punjab), where the Great Bengal Circus is performing. Motilal leaves Rajbala when she refuses to return to the circus (although he remains in touch with his daughter throughout his life), and mother and daughter move to Calcutta. Rajbala trains herself as a singer, and Indubala follows in her mother’s footsteps after a failed attempt to train as a hospital nurse. She trains with well-known musicians such as Gauri Shankar Mishra, Kali Prasad Mishra and Elaahi Bux and the celebrated courtesan singer and dancer Gauhar Jaan takes her in as her only disciple.Footnote35

Indubala’s recording career begins in 1916, with the Gramophone Company initially booking her as an Amateur Artist. She, following her mentor and teacher Gauhar Jaan, would end her recordings with her signature: ‘My name is Indubala’. Her music repertoire was highly eclectic, consisting of Hindustani classical music, Bengali music written by the anti-colonial revolutionary poet and composer Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899–1976), and Bengali devotional kīrtans. Recordings for All India Radio (AIR) on the second day of AIR broadcasting in 1927 is followed by a remarkable pan-India career in music, touring and recording in several states. In 1936, Indubala is appointed as court musician to the Maharajah of Mysore, and over her career she records approximately two hundred and eighty songs (including for films).

Indubala’s exceptional career in music runs parallel to her other pursuits in theatre and film. She first performs on stage for the Rambagan Female Kali Theatre, an all-female ensemble theatre company founded by her mother Rajbala in 1922. In 1924, she joins the celebrated Star Theatre in Calcutta, her stage acting continuing into the 1950s. Her filmography is estimated to include forty-eight films in five Indian languages: Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi and Tamil. She loves writing poetry, jewellery, perfumes and collectibles. She never leaves the red-light district in Rambagan. She passes away in her home in 1984 after a prolonged illness.

My intention here is not to offer a hagiographic portrait but to note how Indubala’s kaleidoscopic career is at once shaped by and subverts the colonial and nationalist discourse on ‘nautch’ that I have outlined in the previous section. A couple of aspects about Calcutta’s performance culture stand out while reflecting on her biography. First, dance gets hushed. It gets excised from the Bengali courtesan’s unified skill-set of singing, dancing and acting. The ripple effect of legal acts targeting southern Indian temple dancing practices was felt in Bengal, amongst the courtesan community: the Madras Hindu Religious Endowments (Amendment) Act of 1929, had managed to successfully curb temple dedication in southern India, and in 1947, the year of India’s independence from British rule, the Madras Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act came into force, making temple dedication illegal and granting devadasis the right to marry mortal men. This, as Mytheli Sreenivas suggests, reinforced the privilege accorded to heterosexual monogamous conjugality within both Indian nationalist and feminist discourses.Footnote36 Indubala’s repertoire was built on skills that were under attack by the anti-nautch state and yet she managed to sustain a celebrated career as a ‘public woman’, without embracing the conjugal ideal. To carve one’s identity as a courtesan during an anti-courtesan era, one strategic move was perhaps for ‘naach’ or dance to be subsumed within music, song or acting. In her research on Bengali theatre actresses from this period, Rimli Bhattacharya suggests that there occurred, firstly,

fragmentation of the components of more composite performance forms: sangeet, nritya, abhinaya or speech as they may have co-existed in many forms. Second, although the theatre appeared to bring together these components, it tended to be more explicitly literary, so that there was always an apologetic air about the songs and dances. They entered (and stayed) almost by default and as an indicator of the poor if not wicked taste of the practitioners and viewers.Footnote37

So the gestural language of Bengal’s courtesans is gradually replaced by a skill focused entirely on voice or text. It is worth noting that in Gauhar Jaan’s biography too, the fact that Gauhar danced is only casually mentioned, that too rarely.Footnote38 There is no analysis of Gauhar’s movements or choreography even though we learn that she excelled in performing the thumri, which may be described as a ‘semi-classical’ form of music and dance.Footnote39 Nor is there any record of what gestures, movements and expressions Indubala, Gauhar’s only student, may have learnt from her. Some of Indubala’s record catalogues list her songs as ‘naach’ or ‘misri naach’, suggesting that her music was intimately linked to dance but record collectors and music researchers in India are unsure of what this may have meant.Footnote40

The second aspect that stands out is Indubala’s non-apologetic stance towards women in sex work. We learn from Sengupta’s biography how Indubala’s activism in Kolkata’s red-light district, where she lived her entire life, was based on a fierce commitment to improve the conditions of women in sex work. In the 1950s, she was involved with the Sammilita Nari Samiti (United Women’s Society), which lobbied for the state and central governments of India to launch anti-oppression and anti-corruption programmes in the red-light zones and which also pushed for the representation of sex workers on government committees on social welfare.Footnote41 It is important to note this in light of the 1956 All India Suppression of Immoral Traffic Act (SITA) and its 1986 amendment, the Prevention of Immoral Trafficking Act (PITA), which armed the law with punitive measures for women in sex work. Indubala and several of her colleagues resisted the colonial and patriarchal script that prostitution was a vice that needed eradicating, making their voices a precursor for contemporary human rights activism led by sex worker collectives such as DMSC in Kolkata today.

In an interview, collector and music researcher Rantideb Maitra revealed how Indubala would invest a lot of her time in reading and writing, surrounding herself with a rich library of lovingly curated books.Footnote42 Her New Years’ Eve ritual would be to write down her reflections on books read over the year in a personal journal. Very little remains of this collection. Some of her diaries were retrieved by Maitra when the contents of her house were sold. These await future publication, but I leaf through some of their pages while listening to her voice for an original Gramophone Company recording on a vintage LP at Mr Maitra’s library in a sub-urban flat in Kolkata. Indubala’s music has been collected and digitised due to the concerted efforts of record collectors across India. The rest of her life lies scattered across different collections, some private, and some, as in the case of her scrapbook, in public institutional archives.

Part Three. Scrappy Evidence: Pleasure, Indulgence and Intimacy in Indubala’s Scrapbook

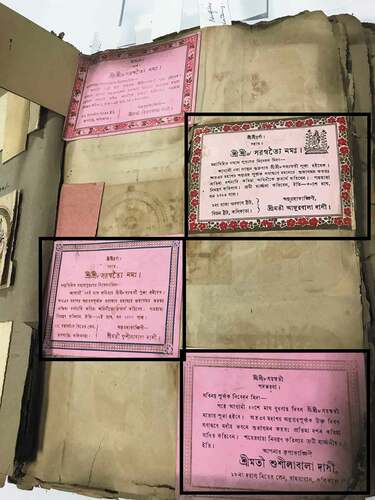

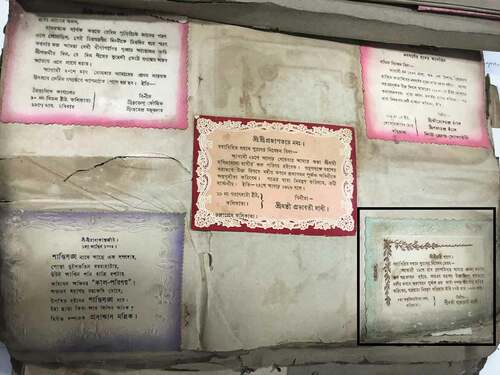

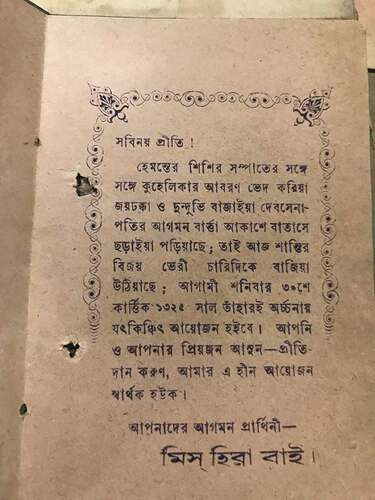

Let me begin this section with a spoiler. There are no illicit pictures, no sensational images of lust and desire, no scenes of sexual excess, and no tragic or melodramatic outpourings of a courtesan’s thwarted love or dashed hopes in Indubala’s scrapbook. In fact, the scrapbook is remarkably restrained in how much it gives away. At first glance, it seems to be a carefully put together but ordinary collection of invitations, Christmas and New Years’ Eve cards, playing cards and menus. The invitations are to a wide range of events in Calcutta’s socio-religious calendar: theatre premieres, pujas for goddess Saraswati, for Lord Kartik, weddings, etc. A closer look at the text of the invitations, most of which is in Bengali (barring one or two which are in English and Hindi), reveals an interesting fact: most of the invitees are women, and most are from Rambagan and its vicinity.

Image 3. See highlighted section. Saraswati puja invitations from Angurbala, Sushilabala and Kironbala in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

Image 4. See highlighted section. Invitation to Radharani’s daughter’s annaprashan (first rice ceremony) in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

Image 5. See highlighted section. Invitation to Ranibala’s daughter’s wedding ceremony in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

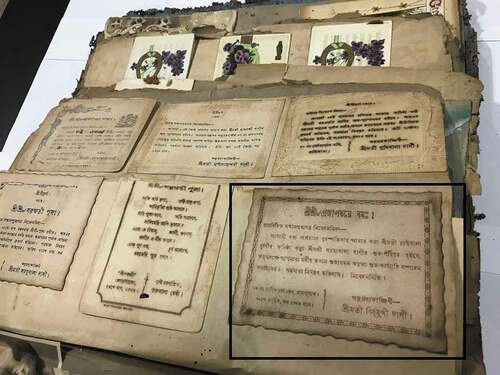

It is only when one carefully reads the details in each invitation that the full import of their meaning becomes clear. Not only are the invitations from women, they also turn out to be from a roster of Calcutta’s early twentieth century renowned stage performers. Saraswati puja invitations from Angurbala, Sushilabala and Kironbala (See ); Radharani’s daughter’s annaprashan (first rice ceremony, see ); Ranibala’s daughter’s wedding (see ); Miss Hira Bai’s invitation to Spring festival (see ); and so on. The scrapbook becomes an archive in itself, holding within it the names, lives and addresses of some of the most iconic women performers from early twentieth-century Bengal. But the scrapbook is not simply an invaluable resource of names. Coded within its matter-of-fact curation of invitations is a set of rather extraordinary events that keep appearing in its pages. These are not the weddings, religious festivals or first-rice festivals for infants that mark recognizable heteronormative events in Bengali culture. Instead, these are invitations from women to other women to attend a pushpostav: loosely translated, this means a ‘flower ceremony’. In all of the invitations, the pushpostav is held either for a daughter or niece of the invitee.

Image 6. See highlighted section. Miss Hira Bai’s invitation to Spring festival in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

Let us, for instance, take Sushilasundari Dasi’s invitation. Dated 22 Ashin 1319 (English calendar date 7 October 1912), it is an invitation to her youngest daughter Nirmala Bala Dasi’s pushpostav on Thursday the 24th day of Ashin (9 October 1912). The invitation is for madhyan bhojan (lunch), sandhya bhojan (evening dinner) and to participate in amod (pleasure) and alladi (indulging) (See ).

Image 7. See highlighted section. Sushilasundari Dasi’s invitation to a pushpotsav (flower ceremony) in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

Indubala would have been 13-years old at the time, so could it be that the invitation was sent to Rajbala, her mother? What were these flower ceremonies? What did these occasions mark and who were its participants? In historian Tapan Raychaudhuri’s study on love in colonial Bengal,Footnote43 we learn that in the late nineteenth century, when child marriage was still prevalent, sex was forbidden before puberty. The first menstruation of the child bride was therefore marked as a second wedding ceremony, except this ritual was observed by women for women and was ‘an occasion for saturnalian scenes out of bounds to men’.Footnote44 In a popular nineteenth century tract written by Satyacharan Mitra and creatively titled Strir Prati Swamir Upadesh (Advice of a Husband to His Wife, 1884), pusphpotsav is described as an event marked by women dancing in the nude.Footnote45 It is possible, then, that while dance disappears or is reduced from the public repertoires of performing Bengali women due to legal reform movements, it still remains, completely unseen to the bhadralok (or respectable person’s) eye, in the private worlds of performing women. This prevalence of women’s embodied activity in the interior spaces of homes complicates the Indian nationalist discourse of home as a ‘spiritual’ space, and subverts a colonial missionary discourse too, one that inscribed Indian women’s idleness and listlessness, in other words inaction, in the zenana or antahpur (women’s only quarters in Muslim and Hindu domestic spaces).Footnote46 In another invitation from Patalmani Dasi, sent on 25 Ashar 1314 (9 July 1907) the arrangement of music and dance on the occasion of her youngest niece Kujasundari Dasi’s flower ceremony is mentioned (See ). These ‘flower ceremony’ events also find mention in Vikram Sampath’s biography of Gauhar Jaan, where Gauhar’s own ceremony is marked by a massive celebration, a long night of excess. But in Gauhar Jaan’s case, men participated in the events too, and tragically Gauhar is raped at the end of the night, unbeknownst to her mother. Could it be, then, that a pushpotsav also marked a rite of passage for post-pubescence virgins, a deflowering ceremony that traded virginity for capital investment (property, cash, gold), an initiation into the world of courtesans?Footnote47 Did these ceremonies succumb to a dangerous capitalist patriarchy, while still affording women a space to find momentary pleasure and liberation?

Image 8. See highlighted section. Patalmani Dasi’s invitation to a pushpotsav (flower ceremony) in Indubala’s Scrapbook. Courtesy of Parimal Ray Collection at the JBMRC archives, Kolkata. Photo: Prarthana Purkayastha

The scrapbook may raise these inquisitive and probing questions from scholars, but Indubala refuses to answer them. There are no handwritten notes, explanations or private comments on the margins of her collected invitations. There is, instead, a dignified silence – or perhaps, a dignified quiet – what Kevin Everod Quashie calls ‘an ethic of quiet, the sense that the interior can inform a way of being in the world that is not consumed by publicness but that is expressive and dynamic nonetheless’.Footnote48 Indubala’s refusal to allow us entry into intimate lives is what I read as one of the courtesan’s finest subversive gestures, an act of self-archiving on her own terms. Like William Prinsep’s painting, which I read as a creative visual archive, Indubala’s scrapbook too is a highly creative material archive, shaped and edited to reveal enough but not all. In it, we witness archiving as a performance that grants access but also locks us out. This self-archiving does not seem to have been intended for an outside audience, to make decipherable or legible the interior world of the courtesan. The memories of the flower ceremony events of the past potentially brought private pleasure to Indubala. Or perhaps Indubala’s archiving was her way of fondly remembering her mother, with her scrapbook becoming a homage to Rajbala, who may have been the recipient of the flower ceremony invitations. If the latter is the case, then the scrapbook is one of the finest and rarest specimens of its kind, the priceless material remains of a unique mother-daughter bond in an Indian-Bengali courtesan world.

There are other subversive gestures too, that point to the anti-patriarchal script of Indubala and her collegaues’ lives. The fact that the scrapbook is dominated by women who invite each other to their private events butts against standard heteronormative socialization practices in early twentieth-century Bengal, in which it is mainly men who invite other men to social events, and men who curate such events. This practice of same sex invitations, I argue, adds a wonderful layer to early twentieth century women’s autobiographies that have garnered so much attention in recent years.Footnote49 The scrapbook highlights, too, the women-to-women transmission of embodied knowledge that may have occurred within these same-sex settings which, as Pallabi Chakravorty argues, was downplayed by Indian cultural nationalism, as in the case of its ‘official representation of Classical Kathak’.Footnote50 Finally, like Veena Talwar Oldenburg’s outstanding ethnographic research with Lucknow’s tawaif community,Footnote51 which reveals queer love and anti-patriarchal performance sketches as standard practice amongst the courtesans, Indubala’s scrapbook also proposes that a similar world of female friendship, love, intimacy, solidarity, amod (pleasure) and alladi (indulgence) may have powerfully sustained their battle for legitimacy in the world outside.

Closing

30 December 2019. After a meeting with Dr Smarajit Jana, Chief Advisor to DMSC, I am guided to Masjid Bari Street to meet members of Komal Gandhar, DMSC’s cultural wing. I enter a building which sticks out in its neighbourhood with its unapologetic pride colours and graffiti. Upstairs, rehearsals and make-up for a show later that evening are just beginning. I start talking to Komal Gandhar’s members, one after another, as they organise their costumes, mark their movements in the choreography, and start getting dressed. Tracks from popular Bollywood films such as Devdas (2002) play on the sound system. There is laughter, teasing, bickering, easy conversations that flow between bodies as they paint each other’s faces or help each other into shimmering costumes (See ). Over several hours, the group slowly and joyously revel in transforming their bodies through make-up, hairspray, costume and jewellery. Amod and alladi are at work here. Eight members are about to go on stage that evening. They are a mix of sex workers and children of sex workers, and half of them are transgender. They are all activists, with many working on anti-trafficking and HIV/AIDS prevention programmes through dance at Komal Gandhar for over a decade. They train in Bharatanatyam and Creative Dance regularly with Sujoy Thakur, dancer/choreographer and founder of Shinjan, a Kolkata-based dance company. They talk about their ‘India’s Got Talent’ experience in 2018, a dance competition show on prime time satellite television where they were finalists in Season 8.Footnote52 I follow them to the Rajasthani Mela (a fair) that evening and watch them perform on stage. They pull in the crowds, even though it is a Monday (See ).

What began for me as a journey into the very private world of Calcutta’s red-light district courtesans with the opening of Indubala’s scrapbook has ended, rather poignantly, with the brazenly public and proud face of Kolkata’s present-day sex workers from Sonagachi. My trepidations around outing intimate lives are blown to bits as I watch Komal Gandhar pirouette, leap, stamp and stride across the public stage, very much out there, marking their space firmly as queer Bengali artists and activists. I use the word ‘queer’ not as a blanket word for all sex workers, but for Komal Gandhar as a specific political formation of individuals, noting that the ‘abnormal’ bodies of hijras (‘third gender’ persons), dancers and homosexuals that constitute this group were also key to the construction of a queer imaginary in colonial India, to what Anurima Banerji calls ‘the queer politics of the Raj’.Footnote53

I began researching Indubala’s archive in the hope of finding remains of the courtesan’s dance from Calcutta’s notorious neighbourhoods. A small part of me hoped that I could recover at least one true song, one true gesture perhaps embedded in the bodily memory of an old matriarch, a living descendant of Calcutta’s courtesan culture. It was the ethnographic breakthrough I secretly craved. What I have witnessed instead is very far from what Indubala or her colleagues would have performed for their audiences – there is no ‘authentic’ Bengali courtesan past to be found here, and no possibilities for ventriloquism, for speaking on behalf of Indubala or Komal Gandhar – they have recorded their lives on their own terms, and continue to speak, or remain quiet, for themselves. Yet I must wrest this history from the grasp of my savarna (upper caste) Hindu privilege that continues to afford me, and other scholars such as myself, access to minoritarian lives, and the power to ‘out’ them. What is the role of the historian or critic, my role, in representing the other, in knowing the other? Following Spivak’s call for responsible postcolonial interventions, Vijay Devadas and Brett Nicholls note that

‘the critical commitment lies not in being able to unscramble the other, so that the other can be made known and part of knowledge. Rather the critical commitment lies in acknowledging the impossibility of forming a straightforward relationship with the other as if the other is calculable, programmable […]’Footnote54

Indubala’s scrapbook opens up this very impossibility of a straightforward relationship with the past lives of illicit female courtesans, while underscoring the historian’s ‘obligation to listen as a duty to justice’.Footnote55 Part of this duty to justice is to notice how the history and legacy of ‘nautch’ remains not just as a story of minoritarian tragedy, but as one riddled with moments of sublime minoritarian activism and insurgence, both in the private and public worlds of its subjects. My duty, too, is to suspect state-sanctioned narratives of cultural heritage and lineage in Indian performance, which inevitably exclude queer or illicit subjects. There may be no direct link between the early twentieth century courtesans’ movements and the choreographies of commercial sex workers in Sonagachi today, and any attempts at crafting genealogical links may seem forced or tenuous. Yet, a dance and performance studies lens allows us to notice striking parallels between Indubala’s career as a Bengali courtesan and activist, and the activist performers I meet at Komal Gandhar, enabling us to queer the very idea of Indian dance heritage and the forms its takes.

As I watch trans and cis-gendered bodies in Komal Gandhar sway and swish on stage to Bollywood songs about heterosexual love and coupling, I am reminded of José Esteban Muñoz’s formulation of ‘disidentification’, a process in which queer bodies of colour neither accept nor reject cultural norms but through a recycling of dominant images and structures, resist from within the mainstream.Footnote56 By inserting their trans and illicit bodies into recognizable and iconic Bollywood music, Komal Gandhar appear to propose a queer ‘counter-publics’, to cite Muñoz again; their choreographies may therefore be seen as ‘social movements that are contested by and contest the public sphere for the purposes of political efficacy – movements that not only “remap” but also produce minoritarian space’.Footnote57 I read the bodies of Komal Gandhar’s activist-dancers as remarkable archives in the process of being fashioned, a self-aware, creative and skilful collective that revels in amod and alladi, that moves with joy and indulgence, and demands that its queerness is seen and heard.

Notes

1. This work was supported by the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust under the Small Research Grants Scheme [grant number SG161464]. My sincere thanks to the following music researchers and collectors in India, for their time and generosity: Suresh Chandvankar in Mumbai, and Parimal Ray, Rantideb Maitra and Ashish Bhadra in Kolkata. Thanks also to Pallab Ghosh, for allowing access to Indubala’s house, which is now his family home. I am immensely grateful to documentary filmmaker and scholar Shohini Ghosh, who provided valuable contacts for the Kolkata-based sex workers’ collective DMSC, and to Dr. Smarajit Jana, Chief Advisor to DMSC and Komal Gandhar, for allowing me access to their work. I am indebted to archivist Kamalika Mukherjee at the JBMRC/CSSSC archives in Kolkata, for her deep knowledge of visual archives and for her unfailing enthusiasm and support for my work on Indubala’s scrapbook, and to Ritwika Mishra for her help. Anurima Banerji and Kareem Khubchandani offered wonderful leads to relevant scholarship and documentaries, for which I am ever so grateful. Finally, my deepest gratitude is reserved for Komal Gandhar and its members – thank you for letting me in.

2. The Jadunath Bhavan Museum and Resource Centre (JBMRC) is a unit of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta (CSSSC). The building houses a library, archive, documentation centre and exhibition space and holds one of the most important archival collections of popular visual culture from eastern India.

3. The use of two different spellings, Kolkata and Calcutta, is a deliberate act of signalling the shifts in this city’s identity. Kolkata is the official spelling of the city since January 2001. As most of the material discussed in this article is from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I will use the anglicised and British colonial spelling ‘Calcutta’ for the sake of historical accuracy.

4. When I first encountered this scrapbook in April 2018, the Kolkata-based collector Parimal Ray had just donated it to the JBMRC archives. In an in-person interview in his home, in itself a spectacular treasure trove of vintage bric-a-brac from Kolkata’s past, Ray stated that he salvaged the scrapbook when many of Indubala’s belongings were sold by her family members.

5. ‘Nautch’ was an Anglicised corruption of the word ‘naach’ meaning dance in Hindi, Bengali and several other languages in the Indian sub-continent. In the colonial imagination, it became associated with oriental mystique as well as moral filth, prostitution and contagion. The Anti-Nautch movement was initiated in the 1890s by reformists and culminated in the 1947 Madras Devadasis Prevention of Dedication Act. It targeted and criminalised devadasis and practices of temple dedication, but it impacted innumerable public dancing women all loosely bracketed in the category of ‘nautch’, and within which I place Bengali courtesans. See Pallabi Chakravorty, Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women and Modernity in India (Calcutta & London: Seagull Books, 2008); and Davesh Soneji Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory and Modernity in South India (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

6. Available literature on Indubala switch between the designations of ‘Devi’ and ‘Dasi’ after her name. Indubala, like many other courtesans in Bengal during her time, may have adopted the designation ‘Dasi’ (female servant of Krishna) to align her more firmly with Vaisnava Hinduism to solidify her social status. Eben Graves notes that this was certainly the case with other courtesans like Indubala who also sang kīrtan (devotional songs) in Bengal, and who similarly wished to distance themselves from the social disapprobation attached to their labour when the anti-nautch movement gained momentum. See Eben Graves ‘Kīrtan’s Downfall’: The Sādhaka Kīrtanīyā, Cultural Nationalism and Gender in Early Twentieth-century Bengal’, The Journal of Hindu Studies, 10 (2017): 328–57.

7. I am referring to Spivak who warns the privileged academic against ventriloquizing for the voiceless subaltern. See Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ in Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993), 66–111.

8. See Anjali Arondekar ‘In the Absence of Reliable Ghosts: Sexuality, Historiography, South Asia’, differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 25, no. 5 (2015): 98–122 (99). Arondekar’s remarkable essay on a diasporic devadasi community proposes that we abandon ‘the historical language of search and rescue’ and focus instead on ‘more imaginative histories of sexuality, full of intrepid archives and acts of invention, full of pith and moment, full of a “lyric summoning”’ (99).

9. I use the term ‘prostitution’ when discussing nineteenth-century events, and I deliberately move to ‘sex-worker’ (the Bengali equivalent in the field is ‘jouna kormi’) when discussing Indubala, her activist work, and contemporary sex-worker activists in India who view sex work as work, rather than criminal or immoral activity.

10. City of Joy (1992), dir. Roland Joffé, prod. Allied Fimmmakers. Born into Brothels: Calcutta’s Red Light Kids (2004), dir. Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman, prod. Zana Briski and Ross Kauffman.

11. Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ .

12. According to The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), human trafficking in India rose by almost 20% in 2016 against the previous year, with 8,132 known cases. See https://in.reuters.com/article/india-trafficking/indias-human-trafficking-data-masks-reality-of-the-crime-campaigners-idINKBN1DY1PB (accessed August 2, 2019).

13. In my interview with Dr Smarajit Jana, Chief Advisor to DMSC (December 30, 2019), I am informed that the Bill (which aimed to criminalise the sex worker’s clients, amongst other things) did not receive support from the Rajya Sabha.

14. See Amrit Srinivasan ‘Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance’, Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 44, (1985): 1869–76; Soneji, Unfinished Gestures; Veena Talwar Oldenburg ‘Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow, India’, Feminist Studies 16, no. 2, Special Issue: Speaking for Others/Speaking for Self: Women of Color (1990): 259–87; Chakravorty, Bells of Change; Frédérique Apffel-Marglin Wives of the God-King. The Rituals of the Devadasis of Puri (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1985); Anurima Banerji Dancing Odissi: Paratopic Performances of Gender and State, (Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2019); Anna Morcom Illicit Worlds of Indian Dance: Cultures of Exclusion (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).

15. Erica Wald ‘From begums and bibis to abandoned females and idle women: sexual relationships, venereal disease and the redefinition of prostitution in early nineteenth-century India’, The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 46, no.1 (2009): 5–25.

16. Ibid., 12.

17. Ratnabali Chatterjee ‘Prostituted Women and the British Empire’, ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change 1, no. 1 (2016): 65–81 (74).

18. Kunal M. Parker ‘A Corporation of Superior Prostitutes: Anglo-Indian Legal Conceptions of Temple Dancing Girls, 1800–1914ʹ, Modern Asian Studies, 32, no. 3 (1998): 559–633 (562–3).

19. See, for instance, Soneji, Unfinished Gestures; and Srinivasan, ‘Reform and Revival: The Devadasi and Her Dance’.

20. Rosie Llewellyn-Jones The Last King in India: Wajid ‘Ali Shah, 1822–1887 (London: C. Hurst and Company, 2014).

21. See Vikram Sampath My Name is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician, (New Delhi: Rupa Publications, 2010); and Binodini Dasi’s autobiographies Amar Katha (My Story, 1912) and Amar Abhinetri Jiban (My Life as an Actress, 1924/5). Both of Binodini’s autobiographies are edited and translated by Rimli Bhattacharya as My Story and My Life as an Actress, (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1998).

22. For instance, Regula Burckhardt Qureshi notes ‘the unprecedented scope for female agency afforded by the salon within a thoroughly patrilineal/patriarchal society’, which stood in contrast with the largely male management of bourgeois public theatres. See Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, Chapter 17 ‘Female Agency and Patrilineal Constraints: Situating Courtesans in Twentieth Century India’, in The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross Cultural Perspectives, ed. Martha Feldman and Bonnie Gordon (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006): 312–31 (319).

23. Sumanta Banerjee Dangerous Outcast: The Prostitute in Nineteenth Century Bengal (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1998).

24. Ibid., 82.

25. Ibid.

26. Swati Chattopadhyay ‘Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of “White Town” in Colonial Calcutta’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59, no. 2 (2000): 154–79.

27. Swati Chattopadhyay Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism and the Colonial Uncanny (London: Routledge, 2005), 256.

28. Aishika Chakraborty Kolkatar Naach: Samakalin Nagarnritya (Kolkata: Gaangcheel Books, 2019).

29. Giorgio Agamben Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1998).

30. Diana Taylor The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2003), 19.

31. Ibid., 20.

32. Rebecca Schneider Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 108, emphasis in original. Citing Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever, Schneider states that ‘it is not discursivity on the one hand and performance on the other that constructs the privilege of the archive, but, for Derrida, “patriarchic” habits of nomination and consignation that police ways of knowing’ (107).

33. Rimli Bhattacharya’s Public Women in British India: Icons and the Urban Stage (New Delhi: Routledge, 2018) makes a brief mention of Indubala and her mother’s theatre company. Bikas Chakraborti’s discusses her activism in Chapter 11 ‘Mirabai and Indubala: Spiritual Empowerment Redefined’ in Debalina Banerjee ed. Boundaries of the Self: Gender, Culture and Spaces (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 127–39.

34. Badhan Sengupta Indubala (Kolkata: Mousumi Prakasani, 1984); The Record News: The Journal of the Society of Indian Record Collectors, Mumbai. ‘A Short Biography of Indubala’, by Jyoti Prakash Guha, pp. 37–54. https://dsal.uchicago.edu/books/trn/trn.php?volume=2008&pages=78#page/36/mode/1up (accessed August 5, 2019).

35. Sobha Sen, ‘Indubala’, Epic Theatre, August/Issue 20, (1972): 47–53.

36. Mytheli Sreenivas ‘Conjugality and Sexual Economies in India’, Feminist Studies 37, no.1 (Spring, 2011): 63–92.

37. Rimli Bhattacharya ‘The Nautee in ‘the second city of the Empire’, The Indian Economic and Social History Review 40, no. 2 (2003): 191–235 (213).

38. Vikram Sampath My Name is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician, (New Delhi: Rupa Publications, 2010).

39. Regular Burckhardt Qureshi notes that in the post-independence bourgeois classification of Indian music, text-oriented genres of music such as thumri and dadra, which were honed by courtesans, were classified as ‘light’, ‘semi-classical’ or ‘mixed’ whereas genres such as khayal and dhrupad were recognized as belonging to the pure classical canon (2006: 319).

40. In interviews with record collectors Suresh Chandvankar (November 14, 2019, online) and Rantidev Maitra (December 26, 2019, Kolkata), some conjectural thoughts were offered. These suggest that Indubala may have recorded songs for dancers, or recorded songs that recreated a dance salon for her listeners.

41. Bikas Chakraborti (2014).

42. Interview with Rantidev Maitra (December 26, 2019, Kolkata).

43. Tapan Raychaudhuri ‘Love in a Colonial Climate: Marriage, Sex and Romance in Nineteenth-Century Bengal’. Modern Asian Studies 34, no. 2 (2000): 349–78.

44. Ibid., 357.

45. Ibid. For a discussion of this tract, see Judith Walsh, ‘The Virtuous Wife and the Well-Ordered Home: The Reconceptualization of Bengali Women and their Worlds’, in Mind, Body and Society, ed. Rajat Kanta Ray (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995), 331–63.

46. Indrani Sen ‘Devoted Wife/Sensuous Bibi: Colonial Constructions of the Indian Woman, 1860–1900ʹ, Indian Journal of Gender Studies 8, no. 1 (2001): 2–22.

47. This is conjectural rather than evidence-based knowledge on flower ceremonies, offered by music researcher Rantidev Maitra during an in-person interview (December 26, 2019, Kolkata).

48. See Kevin Everod Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (New Jersey, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 52.

49. A notable early twentieth century woman’s autobiography is that of Bengali stage actress Binodini Dasi, now translated from Bengali into English by Rimli Bhattacharya. See Binodini Dasi, My Story and My Life as an Actress, (New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1998).

50. Chakravorty, Bells of Change, 27.

51. Oldenburg ‘Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow, India’, 259–87.

52. India’s Got Talent is a reality television series which is part of the global Britain’s Got Talent franchise.

53. Anurima Banerji ‘Queer Politics of the Raj’, in The Moving Space: Women in Dance, ed. Urmimala Sarkar Munsi and Aishika Chakraborty (New Delhi: Primus Books, 2017), 81–101 (97).

54. Vijay Devadas & Brett Nicholls ‘Postcolonial Interventions: Gayatri Spivak, Three Wise Men and the Native Informant’, Critical Horizons 3, no. 1 (2002): 73–101 (93).

55. Ibid., 92.

56. See José Esteban Muñoz Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

57. Ibid., 148, emphasis in original.