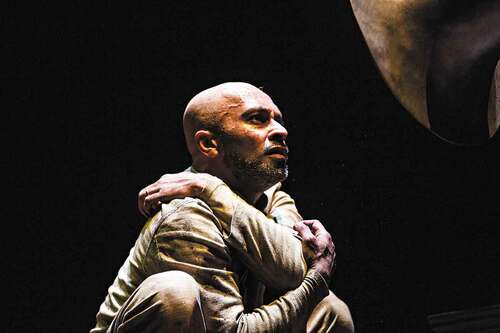

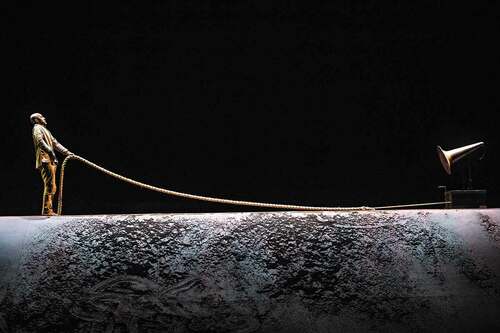

He sits crouched, teetering over the edge above the trenches in which he has been laying cables. He thinks and scratches his head. Next to him, stage left, is an object that looks like a golden gramophone, perhaps a portal to other worlds or perhaps a propaganda machine. He stares at it trying to figure out its function. He discovers that one end of a cable is connected to the gramophone, and, while playfully trying to connect it to the cable he is laying, he accidentally establishes a ‘connection’. The gramophone starts to recite names of the many sepoys, Indian colonial soldiers, who served in World War 1 along with their professions before they went to serve in the war. We learn of engineers and dance masters. As the list continues, his body gets more and more agitated. He moves swiftly away from the gramophone, walking to the opposite end precariously along the top of the trench. He seems worn down by the length of the list and the significance of unearthing these names from the depths of the archives. He is burdened by the responsibility he now shares in commemorating these individuals who served in the war. And then, the gramophone speaks, ‘My name is Taib Ali. I put down telephone cables in the mud. Voices in the mud. Half of them already dead Sir. Already dead. Already dead … already dead … . already dead’ ().

Image 1. Akram Khan stares into the gramophone that starts to list names of Indian colonial soldiers in WW1. In XENOS by Akram Khan Company at Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens, February 2018. Photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez.

Image 2. Akram Khan lays down the wires to bring the gramophone to life. In XENOS by Akram Khan Company at Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens, February 2018. Photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez.

If materiality as evidence is what constitutes archives, then the disappeared bodies who have been historically denied a place within them, and the contemporary bodies who bring the erased to life through the performative power of dance, are themselves archival subjects, teetering on the edges between fact and fiction, as exemplified in this powerful segment from XENOS (2018), British-Asian dance artist and choreographer Akram Khan’s swansong and full-length solo. A dance piece that exposes, critiques, and rewrites historic and contemporary erasures of the significant material contributions of Indian colonial soldiers from the archived British histories of World War 1 (WW1), XENOS powerfully navigates these territories between fact and fiction by transtemporally bringing Taib Ali to life in and through Khan. In this, Khan is both Ali and also not just Ali; he is both Khan and also not just Khan; he is both self and many Others at once. In doing so, I argue here Khan’s brown body becomes a site that claims space and agency for the million plus Indian colonial soldiers, whose unacknowledged labour was integral to Britain’s participation while conspicuously absent from the archives.Footnote1 Furthermore, I argue that his brown body becomes a site that critiques WW1 history and historiography as white-washed projects, at the methodological intersections of the performance genres of historical fiction and reenactment. By deploying a fictive lens through which to embody the labour, voices, and experiences of the Indian colonial soldiers who were not afforded a place in WW1 documented narratives, Khan dances the WW1 archive brown; he dances the archive Other. And in doing so he comments on the process of Othering that has been central to the project of archiving all along, and that continues to shape the psyche of the post-Brexit British nation today, from the position of an Other.

The profundity of Khan’s critique as embodied in his final full-length solo becomes fully apparent when we consider his significant status in the British and global dance sectors. Khan is a critically renowned British-Bangladeshi dance-artist whose significant body of works over two decades has been foundational in mobilising a new interculturalism in contemporary dance within and beyond the UK that centres politics of race, belonging, otherness, difference, selfhoods and embodiments, and operates at the interstices between his intercultural dance training and his complex diasporic positionalities. He is the only British South Asian dance artist to be made an Associate Artist at Sadler’s Wells, London’s premiere contemporary dance house, which positions him as an influential figure in British dance, and his oeuvre has fundamentally and irreconcilably dismantled the whiteness of contemporary dance from firmly within its centre.Footnote2

14-18 Now: UK’s National WW1 Commemoration Project

XENOS was commissioned by 14–18 NOW, a UK-wide WW1 commemorative project that promoted itself as an endeavour to enable ‘extraordinary art experiences connecting people with the First World War’. It commissioned new works by four hundred and twenty contemporary artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and performers who drew on the period between 1914 and 1918 in their art-making. Their website states:

By re-shaping the commemorative act, 14-18 NOW projects have presented heritage on an individual, human scale and enabled artists, participants and audiences to connect emotionally and intellectually with the First World War; prompting people to be more curious about those who lived during it and inspiring them to find out more.Footnote3

Hailed by renowned British filmmaker Danny Boyle, one of the commissioned artists, as ‘a truly nationwide project of remembrance’,Footnote4 the programme’s wide ranging commissions evidence its efforts to provide a necessary corrective on white-washed dominant narratives of WW1 for the British people. Black British public historian David Olusoga speaks from an Africanist perspective on this:

You would be forgiven for presuming that the nations of Africa didn’t take part in the 14-18 war. Their involvement has become a forgotten history, overshadowed by the conflicts between the European powers. And yet the very first shot on land was taken in Africa by an African and the very last engagement between the British and German forces again on the African continent. Over two million Africans served in British, French and German forces. Many lost their lives. And all of them had experiences that were shaped by the racism of the 19th and early 20th century. 14-18 NOW […] is drawing attention to the Africans who served with three major art commissions.Footnote5

Such a corrective stance was also necessary from an Indian perspective, as observed by politician and public intellectual Shashi Tharoor who notes that ‘as many as 74,187 Indian soldiers died during World War 1 and a far higher number were wounded. Their stories, and their heroism, were largely omitted from British popular histories of the war, relegated to the footnotes’.Footnote6 He continues:

Letters sent by Indian soldiers in France and Belgium to their family members in their home villages speak an evocative language of cultural dislocation and tragedy. ‘The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon’, declared one. ‘The corpses cover the country like sheaves of harvested corn’, wrote another. These men were undoubtedly heroes - pitchforked into battle in unfamiliar lands, in harsh and cold climatic conditions they were neither used to nor prepared for, fighting an enemy of whom they had no knowledge, risking their lives every day for little more than pride. Yet they were destined to remain largely unknown once the war was over: neglected by the British, for whom they fought, and ignored by their own country, from which they came. Part of the reason is that they were not fighting for India. None of the soldiers was a conscript - soldiering was their profession. They served the very British Empire that was oppressing their own people back home.Footnote7

14–18 then, in part, set out to unearth these stories of so many racialised Others who served in WW1, but who have remained significantly unacknowledged. In particular, its commissioned dance pieces addressed the question posed by Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebecca Schneider in their introduction to the ‘Archives’ section of the Futures of Dance Studies Anthology: ‘how might archives constructed by spectators from dominant cultures reveal the embodiment of dancers from subordinated cultures?’.Footnote8 It is also precisely this question that XENOS works through, not for dance studies alone, but for the UK’s cultural sector at large. Mobilising this state-sponsored commemorative endeavour to rewrite received histories of WW1, however, XENOS more crucially intervenes methodologically in theorising performance as/of archives. Teetering between and strategically evading the genre conventions of historical fiction and reenactments, in order to give life to the voices of Indian colonial soldiers, I argue that the piece exposes the limits of each of these genres as effective modes through which racial and social justice can be sought in, through, and beyond archives. And in doing so, XENOS performs historiography itself.

‘Bodily Archives’

Archives are white, heteronormative, and patriarchal apparatuses through which colonial (Western) knowledge systems have been legitimised and prioritised over centuries.Footnote9 This description not only applies to the kind of data held in them, but also extends to the very processes by which such data is collated, processed, classified, curated, and presented for the purpose of preservation and future analysis. This is despite interventions from within the field of archive studies itself as scholarsFootnote10 have started to ‘critically interrogate the role of archives, records and archival actions and practices in bringing about or impeding social justice, in understanding and coming to terms with past wrongs or permitting continued silences, or in empowering historically or contemporarily marginalized and displaced communities’,Footnote11 questioning the legitimacy afforded to the deemed permanence of the materiality of written documents and tangible artefacts as white Western masculinist hegemonies on knowledge itself. These questions were however present over a decade earlier in the foundational interventions made by performance studies scholar Diana Taylor’s study of The Archive and the Repertoire, where she notes the historical and critical tension between knowledge derived from material archives and knowledge derived from intangible cultural practices or ‘the so-called ephemeral repertoire of embodied practice’ such as dance, rituals, and oral traditions.Footnote12 To demonstrate the hierarchisation of knowledge derived from the former over the latter, Taylor reminds us that etymologically the word ‘archive is rooted in the Greek word arkhe which means ‘beginning, the first place, the government’, and hence inherently ‘sustains power’.Footnote13 Taylor acknowledges that ‘the space of written culture then, as now, seemed easier to control than embodied cultureFootnote14 such that ‘writing has paradoxically come to stand in for and against embodiment’.Footnote15 To undo this hierarchisation Taylor calls for a shift from the material to the intangible, from the archive to the repertoire, in order to understand the role performances can play in navigating the murky relationships between history, historiography, cultural memory, and, by extension, cultural amnesia. Dance scholar Priya Srinivasan has extended Taylor’s formulations helpfully by recognising a more complex interrelationship between the archive and the repertoire, such that the shift is not from one to the other, but rather a blurring of these seemingly mutually exclusive categories of knowledge production and transmission. She advocates for ‘bodily archives’, arguing that ‘the repertoire is its own archive’.Footnote16

My interest in taking this discourse further builds on Srinivasan’s premise by focusing on those peoples, voices, and experiences excluded from text-based archives in the first place. In this I am also responding to the call put out by scholars advocating for a ‘critical archival studies’, bringing it into conversation with critical dance studies and performance studies:

Let us use our expertise […] to identify injustices, to figure out how to change them, and then enact those changes. Let us use critical archival studies to liberate, interrogate, and usher in a ‘real democracy’, where power is distributed more equitably, where white supremacy and patriarchy and heteronormativity and other forms of oppression are named and challenged, where different worlds and different ways of being in those worlds are acknowledged and imagined and enacted. Let us activate a critical archival studies.Footnote17

XENOS activates critical archival studies through the embodied medium of dance, foregrounding the ‘bodily archives’ of Indian colonial soldiers from WW1. In analysing this piece, I want to consider what happens when these spectres from the past demand intergenerational retribution by acquiring fleshly form in the present moment through a deep interaction with both the archives that have buried them and the mediating embodiments of Khan. Can we consider such transtemporal unearthing of these people from the depths of histories as a rewriting of archives themselves? And if so, how might we reframe the intangibility of their repertoires in this process? When we consider these questions playing out in and through Khan’s movements, XENOS becomes a dance of fractured uncertainty. A fracture between generations and their shared trauma, between erasure and agency, between fact and fiction, between pre-war and post-war, and between life and death. As I go on to describe in the next section, in the opening segment of the piece during Khan’s classical kathak recital at the Nawab’s court, it is not clear if this fractured uncertainty is because this is perhaps his final dance at the court before he leaves for the war, knowing he may never return, or even if he does he is bound to return irrevocably changed. Or whether he is in fact a returned soldier, suffering from post-traumatic stress, trying to reclaim agency, space and voice in a world that was once his. Either way his body is fractured and in trauma.

As a dance piece, XENOS pulls no punches in exposing what the British-Ghanian journalist and cultural commentator Afua Hirsch has referred to as ‘state-sponsored amnesia’,Footnote18 vis-à-vis Britain’s troubled relationship to its colonial past. It calls out the violent erasure of 1.4 million plus Indian colonial soldiers from dominant and pervasive archives and narratives of World War 1, by casting a stark light on these uncommemorated subjects. XENOS critiques received histories of WW1 as incomplete, one-dimensional, and white-washed. It then rewrites these histories by generating complimentary fictional narratives that run parallel, drawing on deeply buried archival materials; intersecting, undercutting, and nuancing the dominant versions in powerful ways. It makes history brown by centralizing the Indian soldier, representative of the many brown bodies at the heart of these narratives, writing themselves and their experiences into the very earth that they have been hidden under and shovelled out of. XENOS asks of its predominantly white middle-class audiences, as I do in this article: why are the archives of the WW1 predominantly white? How do erasures of Black and brown bodies, voices, and experiences from the archives impact present-day public discourses and reimaginings of the Great War? How can the brown dancing body expose and disrupt the whiteness of these archives, by positioning itself at the heart of these reimaginings? More importantly, how can the brown dancing body intervene to reveal that such marginalisations of racialised and minoritised subjects is very much alive in present day discourse and practices?

Xenos, the Other

XENOS opens to a classical musical concert with percussionist B C Manjunath and vocalist Aditya Prakash sat in what appears to be a nawab’s court, surrounding by cushions, a takia (a bench), a swing and some chairs that face them with absent audience members, against a tilted backdrop covered with thick ropes that make their way down from another world into the court. A string of naked lightbulbs lace the ceiling as the musician’s powerful and joyous soundscape of a tarana fills the air. And then suddenly their melodious soundscape is shattered abruptly by Khan’s body falling into a heap onto his front down-stage-right, clutching onto a very thick rope, as though it is invaluable to him. He is dressed in a white churidar kurta and wears ghungroo around his ankles, a classical kathak dancer. Prakash’s voice fades into a quieter presence as Khan gradually gathers himself onto his feet and tries to separate himself from the rope, in order to make sense of why it bears so much weight in his hands. As he tussles with the rope, he falls hard onto the floor again, and this time the classical tarana stops all together into stark silence. Gradually sounds of a nightscape infiltrate the air, as we can hear the barking of a dog. This triggers something in Khan – enhances his disorientation. He walks around aimlessly trying to take stock of where he is at and why, walks onto the takia which caves under his weight and breaks. Mud from beneath the bench smears his pristine white kurta. We witness the start of a murky-ing of his world, but we can’t yet ascertain why. He turns slowly to face the musicians, searching in them for a sense of the familiar, and as soon as he meets their eyes, the light crackles and it goes pitch dark. In the darkness, Khan strikes a matchstick and holds it close to his face as a voiceover, quoting a letter sent home from one of the many Indian colonial soldier’s filters through the air, ‘Do not think that this is war. It is not war. It is the ending of the world’. Khan stares at the match, unflinching, as it burns out all the way to his where his finger touches the stick. We are plunged into pitch darkness.

What follows is a long pure classical kathak recital by Khan, a dance master in this court. He moves between abhinaya, the codified mimetic storytelling movement sequences in kathak that embody sentiments and characterisations of accompanying lyrics, and interludes of intense nritta, the pure technical components of kathak through which this introductory segment of XENOS builds tension and frenzy. The lyrics of the tarana repeatedly speak of a bride leaving her family, her father, and all she has held as her own, for the foreign and distant lands of her husband’s home. It speaks of the pain that such a disjuncture brings and the fear she may never feel welcome in her own childhood home again. Against these melancholic words, Khan dances his fractured uncertainty. He repeatedly interrupts his classical abhinaya gestures by tightly covering his mouth with his left hand, as though being silenced by himself or other external forces. He regularly pauses between his frenzied dancing to think, take stock, orient himself. And each time, his percussionist taunts him with ‘Bhul gaye kya?’ (Have you forgotten how to do this?). Khan responds to these teasings, dancing out his fractured existence with increasing vengeance. And through these sequences he repeatedly focuses on his hands, staring at them, wringing them in despair, as though trying to get rid from them whatever inhuman acts they have committed that lay buried deep in their sinews. As Khan’s distorted dance builds to a crescendo, he goes into kathak’s signature chakkars (pirouettes) until he loses balance and lands in a heap, and finds in his hands the same rope he found himself clutching onto when he came into the concert. He shakes them off, with much the same intention as he tried to shake off his own hands. He slowly starts to unwind his ghungroos from around his ankles and, keeping one of their ends held in place between his toes on each feet, he extends them to hold them up. He tries to walk, impeded by the ropes that hold his ghungroos together and falls face down again. He desperately shakes the ghungroos of his feet and lies them flat on the floor, staring at them, picking them up from underneath them, palms facing the ceiling. The musicians gradually disappear as Khan winds his ghungroos around his upper body, crossing each strand of rope over his chest as though they were reams of bullets strapped to his body. His movements start to shift from the lyrical to the angular, from the expansive to the contracted, hardening and sharpening his posture. Accompanied by a grating, industrial drone soundscape the nawab’s court-world is sucked up by the ropes hanging off the tilted backdrop and disappears out of sight, as Khan desperately tries to keep hold of it. He climbs to the top of the tilted stage, watching his world vanish and turn Other, and as the light darkens, he is spat out, down and into the trenches, showered by mud.

The word xenos in Greek means stranger, the unknown, the Other. Not surprisingly then the trope of the Other runs through multiple layers within the piece. Ruth Little, the dramaturg on the project, reveals the multi-layered symbolisms buried within the title of the piece. At the diegetic level Xenos is the name given to the character(s) of the Indian solider(s) that Khan brings to life. It is unclear if he plays one fictional composite character derived out of collated materials drawn from letters written by Indian soldiers to their families during the war that speak of ‘homesickness, love, women, faith, folk songs’,Footnote19 or many different soldiers at different points in the piece, embodying the many different traces of voices from the archives. In a sense this lack of clarity does not matter – Xenos is the name of each manifestation that Khan dances. The piece begins with Xenos the dance master in a north Indian nawab’s court, before his existence is obliterated beyond recognition as a result of being enlisted to serve in the Great War:

Xenos is a dance master in the nawab’s court. His life is shaped by tradition and ritual, by the conformation of his body to social and religious tradition. But he is a master. His craft is movement. War replaces one form of movement with another, and the work expresses the experience of embodied dislocation and cultural estrangement in its choreography. Xenos is enlisted in the myth of empire, and processed in industrialised warfare.Footnote20

Khan’s body is now entrenched into, and has become, the battleground as it starts a mechanistic and angular dance of rebirth into this hostile and unfamiliar world. We see the dance-master’s body transformed by discipline as the sound of a whistle makes his stand upright with his hands behind his back. He is disorientated by the sounds of dogs barking, just like they did outside the nawab’s court. In another life. He discovers on the top of the trench, located on up-stage-left, what looks like a gramophone. He spends much effort trying to figure out what it is while simultaneously laying down thick ropes that look like cables. Through all of this endless labour, his body responds to the sound of a whistle by standing upright, hands behind his back. To the sound of gun-fire, he throws himself onto the floor with his arms over him in a protective manner. And each time he picks himself up and continues. Mechanised by war, Khan’s becomes a stranger to himself.

Xenos, the Other occupies the heart of this piece. First, Khan is Xenos, every Indian colonial solider, serving the war under inhumane, dehumanised, racialized, and discriminatory conditions.Footnote21 Second, Khan experiences the cold and distant unfamiliarity of the Other-land in which he serves his colonial masters, irreconcilably torn away from the familiar comforts of his motherland. Third, Khan is also an Other to the highly mechanised world of industrialised warfare into which he has been thrown. And finally, the title enables us to dwell on the implications of Khan, a second-generation British dance-artist of Bangladeshi heritage as Other, in representing the unacknowledged Indian colonial soldiers of WW1. This is particularly pertinent because history tells us that these subjects were mainly Punjabi Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs from the ‘middle peasantry, recruited from the north and north-west of India partly on account of the “martial races” theory of the British which suggested that some races or castes were inherently more warlike than others’.Footnote22 Consequently, most Bengalis were enlisted in the war as labourers. However, history also tells us that XENOS conjures a time when the Indian subcontinent was one large landmass, not yet violently and arbitrarily partitioned into the nations of India, Pakistan, and, ultimately, Bangladesh. In performing the Other at multiple levels, XENOS opens up questions on the ethics of historical fiction that addresses past power asymmetries by asking who gets to speak for whom? Khan’s dancing in XENOS as representative of these erased Indian colonial soldiers and labourers needs to be understood as both a marking of shared ancestral histories, cultural memories, and anti-colonial struggles within the sub-continent during WW1, and a conscious and corrective colouring of the archive to a much-needed brown. This blurring between his own privileged diasporic positionality, and the subaltern brown soldiers he brings to life is simultaneously troubling and compelling.

He sits, thinks, scratches his head. He repeats all of this endlessly. He discovers the end of a cable connected to the gramophone and while playfully trying to connect it to the cable he is laying, he accidentally establishes a ‘connection’. It starts to recite the names of the many sepoys, Indian colonial soldiers, who served in WW1 and their occupations before they went to serve in the war. We learn of engineers and dance masters. As the list is reeled off, Khan’s body gets more and more agitated. He moves away from the gramophone, walking and teetering on the edge of the trench to the opposite end, worn down by the weight and significance of the unearthing of these anonymous sepoys from depths of the archives. He is both worn down by the weight of the moment and the responsibility he shares in naming and marking these individuals who served the war, but have remained uncommemorated. And then, the gramophone speaks, ‘My name is Taib Ali. I put down telephone cables in the mud. Voices in the mud. Half of them already dead Sir. Already dead. Already dead … already dead … . already dead’.

The stark implication is that his laying down of telephone cables that enables both communications between the different warring fronts and leads to the killings of so many, as the gramophone endlessly repeats ‘already dead’ like a broken record. This forces Khan to try and disconnect the cables, so the gramophone stops. But even after he disconnects the cables, the repetition continues. And then the gramophone disturbingly comes to life, converted now into a search light that starts to survey the stage and the audience. We are blinded by the light, exposed and implicated in bearing witness to these atrocities of war and still remaining silent from our positions of privilege.

Carrying the metaphoric and physical weight of the cables, Khan slowly spirals, heaps and piles them onto and around his neck, creating a faceless persona that dances a faceless existence in the trenches, far away from his homeland. Obscured by the cables, Khan’s abhinaya is now grounded solely in his body, no longer able to rely on facial expressions. Once again, the Hindi lyrics speak of separation from the beloved and the familiar, in a land where no one comes or goes, where the moon and sun and wind do not appear any longer ().

Image 3. Akram Khan piles on the wires over his head to obscure his identity and represent the million plus Indian colonial soldiers in WW1. In XENOS by Akram Khan Company at Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens, February 2018. Photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez.

Khan’s transtemporal embodiment of the uncertainties of being the racialised Other in the trenches is delivered with great detail and empathy while also exposing the historiographical dimension of XENOS. We witness the gramophone recite the endless list of names. We are left in a state of disease because it is never clear whether these names are the actual names unearthed from the archives, or a list augmented by Khan and his creative team’s imagination. We do not know if Taib Ali is a historical figure who laid cables in the trenches of WW1, or a composite figure created in response to the traces in the archives. The reinforcement of this blurring between history and imagination is present in the words ‘voices in the mud, already dead Sir … already dead’. A chilling reminder that Ali speaks for those who are already dead and can’t speak for themselves, just as Khan gives voice to the silenced subaltern soldiers. Khan becomes the historiographer, and in outing these names he simultaneously outs the whiteness of the archives that buried them deep into the depths of WW1 histories.

Beyond the immediate remit of the performance, the title XENOS bears further significance with regards to its reference to the Other and Othering more generically. In wider contextual terms then, I cannot help but wonder what it means for someone of Khan’s professional stature to title his final solo, XENOS. What does this choice illuminate about his reflections on the consequences and limitations of the Other to write themselves into the central landscape of British dance, so as to fundamentally transform how it looks, who it speaks to, and what it speaks of? Can the Other disrupt the centre from firmly within it? At a panel I was invited to curate by Akram Khan Company at Sadler’s Wells on 3 May 2018 with Khan and his key collaborators about the making of XENOS, the chair Alistair Spalding, the Artistic Director and Chief Executive of Sadler’s Wells, pondered on the question of Otherness in the piece, and asked the panel whether in fact, to some extent or another, we are all Others. Ruth Little’s response to this provocation was critical and vital in this moment. A white woman herself, she reminded the audience that to consider each of us as Other is to diminish and ignore the inherently dehumanising and degrading process that is Othering as experienced by the subject on the receiving end, due to the oppressive power relations that operate in the act.Footnote23 With this, Little reminded us that Othering, as has often been mobilised by and through the white gaze, is a fundamental enactment of power. Spalding continued this line of enquiry and asked Khan whether he feels like an Other in the UK. Khan’s response built on Little’s and complicated the various layers and contexts at which Othering works. He said that his feeling of being the Other shifts, changing from context to context. For example, in Wimbledon at his biracial children’s school playground he feels he is brown, while in an Indian classical dance or music concert in London he feels Bangladeshi. These reflections from the two leading members of the creative team confirmed that at the heart of XENOS was a strong critique of Othering that manifests as both erasures in and from WW1 archives and within the dominantly white contemporary dance sector, mobilised by Khan, from the position of the Other. And to tie these seemingly disparate but fundamentally linked critiques together and come full circle, can the absence of the Indian colonial soldiers in the archives and the absence of more Black artists and artists of colour in the contemporary dance sector, from the perspective of a brown artist who has spent their career centring absent voices through his body-of-works, disrupt the power upheld by whiteness from within the centre? As I have previously argued, this is absolutely the case,Footnote24 but XENOS takes this critique of whiteness to an explicit place and form. As Khan notes, while talking about Tim Reiss’s The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (2013), which he read and was influenced by during the making of XENOS:

The Black Count is a biography of General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, the father of the famous French author Alexandre Dumas. The elder Dumas’ father was a white, French nobleman, and his mother was of African descent, enslaved on a plantation in Haiti. So, Thomas-Alexandre was mixed race but had nobility running through him. He later fought in the French Revolution, and he was so strong and well respected that he was considered a threat to Napoleon, so they locked him up, with no reason. Alexandre was in awe of his father’s story. He wrote about him in The Count of Monte Cristo, but he knew the world wasn’t ready for a black hero. That’s why The Black Count surprised me – most of our civilisation has been based on the white-male perspective. There are so many stories that have been edited out of history because they’re different, or because of power and greed. I want to tell those stories.Footnote25

Khan, through XENOS, was consciously trying to dance the archives brown and in doing so created a piece that became an inconvenient truth, forcing its way out of the burial grounds of WW1 that had consumed so many stories beyond recognition.

In an interview about her powerful intervention to dominant studies of empire, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent, Priyamvada Gopal explains the need to expose how such inconvenient truths have been systematically and deliberately contained and erased from public consciousness and, following on, she advocates for their resurgence :

I very much want young Britons who are repeatedly urged to be proud of the imperial past to have access to a different past. A past in which their ancestors stood up and challenged the empire. That history has been marginalised and obscured, possibly quite deliberately so.Footnote26

Gopal’s words have important bearings on our present times, not just so young Britons (and others) are given the tools to re-examine the knowledge they have inherited about Britain’s imperial and colonial past of which WW1 is an integral part, but more importantly to apply this understanding to a long overdue re-evaluation of their turbulent present. It is in this context that XENOS needs to be understood as much more than a rewriting of white-washed history, important as this in itself is. Khan shares how the present and devastating state of UK foreign policy, anti-refugee and anti-immigration rhetoric implemented by the last decade of Tory government and their hostile environment policies led him to dig deep into the archives during the making of XENOS, such that the piece became a transtemporal meditation on the violent relationships between all kinds of hegemonies and oppressed Others:

If we conceive of ignorance and fear and greed for power as symptoms of war then what is really scary is that the same symptoms we see arising now – hatred of refugees, the so-called Muslim ban, the Home Office’s deportation policies – were also arising before the first world war. But we share the earth with these people whom we are so quick to make into strangers and so this sense of nationality, nation states and borders becomes all about power and greed. The piece was initiated by bearing witness to the ways in which the wealthy world dealt with the mass migration of Syrians. Looking on, I thought: when we don’t recognise ourselves in others, humanity is lost. The irony is that in the end, it’s not about wealth: the earth has the flu and will get rid of the virus that we are. We can choose while we’re here to lean into our capacity for greed, harm, and hatred or into our capacity for kindness, grace, and empathy.Footnote27

XENOS must then be read as both a rewriting of white-washed WW1 history and a powerful commentary on the ways in which so many embodiments of the Other continue to be violently dehumanised and marginalised in our white, patriarchal, able-bodied, classed, cis-gendered, heteronormative, and in the context of India and its diaspora, Brahminical social order. And Khan’s dance of despair, faceless, transfigured and imprisoned within the ropes is a stark reminder of the ways power plays out in and through our bodies.

At the end of dancing out his lyrical, nostalgic, homesick existence, it’s embodied message of stark loneliness and despair is echoed by the gramophone as a voiceover, as the searchlight slowly and menacingly beams across the audience:

And then I was a father. I was a son. And then at another time – and another time – I was a daughter. And then a father and a mother. And then a lover, again several times. I’m alone – I’ve been alone – I’ve been a soldier. I’ve killed and I’ve been killed. And again. Several times. Is it not enough?

As audience members, we are implicated in this transtemporal emphasis on humanity’s refusal to accept the horrors of war, discrimination and violence. We are forced to acknowledge the devastation it leaves behind for all concerned. Khan slowly, painstakingly, despairingly rolls down into the trench, obliterated by his experiences, a body beyond trauma. As he reaches the bottom of the trench, something rolls down next to him, and then another, and another … and then more and more and more. Pine cones rain down reminiscent of the line from a letter by an Indian colonial soldier, ‘The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon’. Khan is buried in this overwhelming avalanche of that which is simultaneously the promise of life and the harbinger of death. When it finally stops, Khan picks up a pinecone, stares at it in emptiness and lets it roll out of his hands. He has given up all hope. There is none left around him. The lights slowly fade on this devastating commentary on the state of humanity ().

Image 4. Akram Khan is showered on by an avalanche of pine cones in the final scenes. In XENOS by Akram Khan Company at The Grange Festival, Hampshire, December 2017. Photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez.

XENOS is an urgent call to remind us that violence against and erasure of all minoritised subjects continues to remain a twenty-first century reality. It is like a painfully long and silent scream that articulates the ongoing injustices in our world. As a brown, immigrant, middle-class, caste-privileged, cis-gendered, heterosexual, able-bodied Indian woman I hear this scream loud and clear. XENOS reminds me of the contexts in which power operates in my favour and I choose to remain complicit, and those in which I am at the receiving end of marginalisations. I am reminded:

As the genius gramophone and propaganda machine turned panopticon search-light beam, slowly pans across the audience, and blinds us out of our apathetic states, we are all implicated in our silent perpetuation of these inequalities through our own privileged positions, as we ignore so many Others teetering between life and death.

Writing the unacknowledged Indian colonial soldiers back into received narratives of WW1 is then just one dimension of XENOS. But critiquing its erasure in the first place and signalling how such erasures and dehumanisations continue to operate at large scales in the present day, for me, is perhaps the piece’s more lasting and powerful commentary. And this is where we, as scholars, educators, art lovers, and most importantly the general public become incriminated. This is where XENOS makes us confront our privileged relationship to the Other through treading a fine line between historical fiction and reenactment, while simultaneously exposing each genre’s limits in enabling social and racial justice.

Who is the Archive? Between Historical Fiction and Historical Reenactment

XENOS weaves in and out between fact and fiction as Khan’s embodied twenty-first century diasporic and racialised reality interfaces with the early twentieth century Indian colonial soldiers with whom he shares ancestries. Navigating murky territories between performance, history, cultural memory, and state-sponsored amnesia, XENOS resists easy categorisation and both comes alive at the intersections and teases out the limitations of historical fiction and historical reenactment, and their respective complex relationships to the legitimacy of archives. We are unsure whether Taib Ali is a composite of archival remains of several of these men brought to life by Khan and his creative team’s imagination. We are uncertain to what extent what we bear witness to is in fact, fact. But this fidelity to the factual seems irrelevant. Instead in being concerned with the erased histories of WW1 Indian colonial soldiers, the piece exemplifies Srinivasan’s observation that, ‘the historical archive is after all, a place to find and exhume unmoving dead bodies, not living moving ones’, by turning particular attention to performing ‘the dead bodies that once moved’.Footnote28 However, XENOS’ focus on the once-moving erased dead is mobilised through Khan’s living brown body and reality. This simultaneous investment in both what has been erased and has thus disappeared, and what remains of these people and memories as the fleshly materiality through which the dead can be brought to life, evokes for me performance studies scholar Rebecca Schneider’s assertion that ‘performance can be engaged as what remains, rather than what disappears’.Footnote29 By considering Khan as what remains in material terms and the erased Indian colonial soldiers as those who have disappeared, XENOS engages both simultaneously, and this is what makes it blur the genres of historical fiction and historical reenactment.

Despite their varied and complex allegiances to ‘factual legitimacy’, another shared component between these two genres of performance is the role of imagination, and the efficacy with which it fills gaps and fissures, and addresses erasures.Footnote30 Was Taib Ali, the cable-laying soldier, the dance master who opens the piece in the nawab’s court? We are not sure. We hear in the list recited by the gramophone of a soldier who used to be a dance master. But these links are unclear and ultimately don’t matter. The imagery of the avalanche of pine cones that bury Khan in the closing section, clearly draws on the imagery evoked in the words of the soldier who wrote home in a letter ‘the shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon’, and the monsoon becomes augmented into a scene of annihilation. Khan and his creative team deploy a fictive filter to the traces they encounter in the archives, in order to make XENOS speak beyond the archives, to the violent state of humanity now. And in this imagination plays a key role.

Writing from the context of tracing the genealogy of the mulata body, dance scholar Melissa Blanco Borelli advocates for the power of imagination, extending the philosopher and feminist Rosi Braidotti’s thinking on imagination as transformational:

There is something hopeful in the imagination. It envisions new possibilities and can even provide ways to understand or endure the past. Here, I am thinking of the many historical novels about mulatas and how they contribute to what will always be an incomplete archive. Still, this imagination produces something I consider hopeful.Footnote31

In her book She is Cuba: A Genealogy of the Mulata Body Blanco Borelli turns to performative writing in the form of interludes between the chapters to present a different modality with which to ‘enliven the scholarly discourse on the mulata body’.Footnote32 She states further that through these interludes she can ‘ponder the perils and epistemological potentiality that performative writing affords when materializing subaltern subjects’.Footnote33 This methodology seems key to understanding not only the efficacy of the fictive nature of XENOS in its attempt to centre WW1 Indian colonial soldiers, but to also consider Khan’s positionality vis-à-vis speaking for and materializing these historical subaltern subjects, from his position of relative contemporary privilege. It is important that we do not conflate the colonial soldiers’ subaltern positionalities with Khan’s embodied attempts to represent them. Yet, their shared ancestries and inherited narratives do find ways to collapse within his material presence, fuelled by imagination. It is also the interplay between reenactment of voices and traces as found in the archives and the augmentation of these voices and traces through fiction and imagination, that XENOS can signal to a reality beyond the trenches and turn a mirror for contemporary society to see itself now.

The role of imaginary and creative possibilities in engaging with historical reenactments has also been noted by performance studies scholar Andre Lepecki who has theorised the recent turn towards re-enactments of past works in Euro-American dance as a ‘will to archive’.Footnote34 Lepecki argues that ‘will to archive’ derives out of a recognition by choreographers of the ‘still not-exhausted creative fields’ and undiscovered possibilities that lie dormant in these works. XENOS is of course not in this sense a re-enactment of a past dance-work.Footnote35 However, in its investment in bringing to life the lives and plights of WW1 Indian colonial soldiers, the performance engages with re-enactment of histories through the fictive filter licensed by the genre of historical fictions. In this context XENOS embodies a ‘will to archive’ by examining and discovering the still-not-exhausted possibilities of engaging with WW1 archives that have systematically silenced these subaltern subjects. More importantly, XENOS demonstrates a ‘will to archive’ brown. It does so by exposing the tension between firmly locating its reenactment as ‘an act in the present’ and consciously challenging critiques of such reenactments as ‘historically defective’, by exposing these histories in themselves defective, white-washed, and incomplete.Footnote36 At the heart of its experimentations with re-enactment is a desire to reclaim space within WW1 archives. Dance scholar Mark Franko alludes to the particularities of the relationship between space and temporality in dance reenactments in the introduction to his edited anthology The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment:

When it comes to dance, let us emphasize that it is also an act that reclaims space for movement. Because of the prominence of gesture in dance, space also has certain claims on historicity. The carving of space in particular choreographic actions cannot be identified uniquely with the present, no matter when the actions are performed, because formally defined uses of space do not evoke a temporal so much as a rhythmically shaped dimension. Further, the idea of remains or the remainder is based on materiality, and hence cannot do without space and spatiality.Footnote37

Such spatial and temporal rewriting of the archives that is the heart, soul, and fuel of XENOS is also present in dance scholar Prarthana Purkayastha’s recent workings through the archives of colonial exhibits, as she tries to give voice to the silenced nautchwalis who were brought over from India to dress the windows of late nineteenth century London’s Liberty Store. Purkayastha recognises and cautions against the structural limitations of such dance re-enactments in the process. She observes, ‘I would argue that there are ideological underpinnings within current contemporary Euro-American dance reenactments, which fail certain kinds of archival traces, certain violent histories, and certain types of dance remains’.Footnote38 She continues to critique the predominantly white-referential nature of most dance reenactments projects, observing that ‘neither authorship as a conceptual drive nor notation as a methodological tool can help us re-imagine the nautch’.Footnote39 Purkayastha advocates instead for historical fiction mobilised through corporeal methodologies as means to decolonise dance studies’ archives. XENOS, similarly, rejects the project of simply reenacting the lives and plights of these subaltern subjects. Instead, it draws on multiple voices and experiences that call out through letters and songs that have been buried deep in the archives. Like Purkayastha, XENOS mobilises fictive filters to fill gaps, in order to create a composite multi-layered character embodied by Khan.

Ruth Little summarises the varied sources that orientated their research and anchored their creative process:

The Canadian playwright Jordan Tannahill who wrote the text for XENOS, draws phrases from letters written by Indian soldiers and recordings in the Imperial War Museum.

The BBC radio documentary The Ghostly Voices of World War One (2014) plays recordings of stories, poems and songs by Indian soldiers captured by Germans.

Letters quoted by Santanu Das in The Guardian: ‘As tired bullocks and buffalos lie down at the end of the monsoon, so lies the weary world. Our hearts are breaking’. Santanu Das said the sepoys (professional Indian infantry privates) were neither blindly loyal nor naïve victims. They instead negotiated complex cultural terrain.

We drew also on Across the Black Waters by Mulk Raj Anand (1939). 1.4 million Indian sepoys (out of 70 million combatants, and over 9 million dead), mostly recruited from peasant-warrior classes of North and North-Western India. Among them, Punjabi Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus. Also, labourers recruited from Bengal.

For insights into the experience of shell shock we drew on writings by nurses Ellen La Motte and Mary Borden, and archival footage on YouTube.Footnote40

In weaving these sources together via fictive means, XENOS recognises that its efficacy has to lie in not only unveiling historic erasures in the archives, but in centring Khan as the archive that connects the dots between shared ancestral trauma and present-day erasures of minoritised subjects. In this it extends Lepecki’s assertion that reenactments (in this instance not of dance-works but of erased histories) not only ‘unlock, release and actualise’Footnote41 what was, but consequently centre the role of the fictive in rewriting these histories, foregrounding the subaltern spectres through the process.

Through playing out at the limits of both historical fiction and reenactments, the stories told in XENOS belong to Khan and also don’t. The scenarios recounted and restaged are fictive while drawing on many semblances of memories, letters, and accounts drawn from the archives. In trying to undo the erasures within the archives, XENOS aims to achieve ‘more than enacting history, although it certainly does that’.Footnote42 Much more importantly though, XENOS stages historiography by focusing on the possibilities that emerge beyond the material in the realms of the ephemeral. Historian and modern literature and culture scholar Santanu Das notes in his book India, Empire, and the First World War Culture: Writings, Images and Songs that in recent years there has been a turn to investigate and unearth the Indian colonial soldier, the sepoy, in the First World War. He observes further:

If there has been a powerful material turn within cultural studies in recent years, some of its greatest yields have been in the field of colonial history; increasing use is made of ephemera, from calendar art to songs, in South Asian history, while Africanists have emphasized the importance of oral archives.Footnote43

Framed by 14–18 NOW’s curatorial endeavour, XENOS embraces this turn and reaches out to the realm of the performative, in order to transform the ephemera that exists around lost narratives of WW1, and that sits in and is generated from ‘bodily archives’ of the spectres whose stories had been silenced. It is this ephemera and ‘bodily archives’ that Khan’s dancing body in XENOS mobilises in his navigation of shared, inherited, ancestral South Asian histories of trauma, from his position within the British-South-Asian diaspora.

Dancing the Archive Brown, Dancing the Archive Other

This blurring between historical fiction and historical reenactment generates in XENOS a sense of dis-ease, and this experience of never not fully knowing puts us, its audience, permanently on edge. Moreover this dis-ease spills over from the realms of fact and fiction to the aesthetic world itself in which their blurring plays out. The melodious tarana distorts in and out of grating, disorientating, industrial drones. The poignant Hindi and Urdu lyrics and the significant classical Indian dance concert at the very beginning remain untranslated, layers of meaning unapologetically hidden from many in the audience. Our access to these layers of the performance teeters between the familiar and the unknown, just as Khan as the Indian colonial soldier, teeters on the edge of the trenches, trying to make sense of his life in foreign lands. Our stomachs churn as his body is hurled across the earth. We hold onto the hope offered in the one pinecone that he buries, until it is obliterated by the avalanche of pinecones that then nearly bury him. Nothing makes sense. Yet through the strange, we cobble together a deep and empathetic understanding of the Other, as one permanently under scrutiny, more often than not erased, endlessly dehumanised while also endlessly exploited, and forever trying to piece together their own existence on their own terms. We experience what it is like to not understand, and most importantly to be not understood. And in these states of ambiguity, Khan centres and writes brown ways of knowing and being in and out of the archive. That is to say, the ways in which South Asian audience members are empowered to experience and understand the piece remains deliberately distinct from the ways in which its predominantly white middle-class audiences are able to experience the piece.

Throughout, XENOS Others the archive and dances it brown in both explicit and implicit ways. By bringing to life in fictive composite terms archival subjects of an Indian colonial soldier who started life as a dance master in a nawab’s court, Khan, renowned for his contemporary dance works chooses to unapologetically centre a full twenty-minute segment of classical kathak at the start of the performance, accompanied by two classical Indian musicians who are visibly and aurally integral to its architecture. Predominantly white audiences with little to no understanding of the codes of kathak or the classical music, and with expectation of a WW1 commemoration piece, have to sit in the discomfort of their own unfamiliarity with these classical aesthetics. Those in the audience who are familiar with the codes of abhinaya and the accompanying Urdu lyrics of the tarana, mostly brown South Asian audience members like myself, are therefore also centred through Khan’s deliberately exclusionary aesthetic choices. We are empowered to make links and experience the piece at intellectual, aesthetic, and phenomenological dimensions that is denied to XENOS’ white audience members. Another explicit browning of the archive is the moment when the names of Indian colonial soldiers are recited during the performance through the gramophone that Khan connects through laying down cables. Not only do we hear these names recited, and hence commemorated, for the first time, it is Khan’s labour in laying down the telephone cables that enables the very mechanism that names these heroes. Using actual excerpts from the letters written by the colonial soldiers to their family back in the Indian villages, letters that have been deeply buried in the archives, is an explicit homage that enables these men to speak from the silenced dead. Their words do not just get voiced in the piece’s aural landscapes, much more interestingly, they shape the visual landscape of XENOS. Khan transforms the poignant reference in one letter to the monsoon-like raining of shells into a devastating commentary on life, hope, death and burial in the final scene of the avalanche of the pinecones.

However, perhaps the most impactful aesthetic strategy through which Khan dances the archive brown is that of non-translation. In my monograph Akram Khan: Dancing New Interculturalism, I talk about his postcolonial strategy of non-translation through which he decentres contemporary dance audiences by creating a sense of disease in them. I argue that this strategy of non-translation refuses to make accessible or explain in easy terms the highly complex, racialised, dehumanising condition of being the Other in white Western environments. I propose in the book that Khan deliberately denies layers of meanings from different members of the audience at different points in order to upend power, and makes dis-ease an integral component of his aesthetic. In particular, Khan’s inflection of non-translation plays out in the ways in which he deploys abhinaya, the codified and mimetic storytelling feature of kathak, in the obscured meaning-making in XENOS.

During the opening classical concert section of XENOS, Khan dances kathak for a prolonged twenty minutes. He moves between pure technical nritta and mimetic abhinaya accompanied by Urdu lyrics, acting out each word of the song. Aditya Prakash sings of a bride leaving her family, her father, and all she has held as her own, to start a new life in her husband’s home, in distant and hostile lands. Only those of us who can understand these lyrics, which are not coincidental, can link the parallel Khan draws between leaving one’s home/land for war and leaving one’s home/land for marriage. This paralleling further draws attention to and critiques the masculinization of war and its subsequent commemorations and the feminisation of the domestic sphere of home, emphasising that all genders experience losses entailed in departures in profoundly similar ways. Khan’s dancing out of the parallels between the departure of a bride for their husband’s home to the departure of a soldier to war in foreign lands, is a powerful, feminist choice of writing the brown women left behind by the Indian colonial soldiers, into masculinist archives. It writes back into WW1 history not only the million plus Indian colonial soldiers but also gives voice to the emotionally traumatic plights of often very young Indian women whose lives were left empty and devastated by their men’s departures. These lyrics are incredibly pertinent to how Khan’s embodiments can be read – yet they are not made accessible to the piece’s majority white audience. In addition, in this first instance, the nature of abhinaya does not stray from its classical codifications but is layered and interjected with the repeated gesture of silencing, which he enacts over his own mouth with his left hand. And every time this happens, Khan steps out of his classical dance routine, to reflect on the gesture’s embedded resonance.

It is in the creative licences it takes to avoid categorisation vis-à-vis its relationships between legitimacy and imagination, between fact and fiction and between the material and the ephemeral that XENOS enables voices to speak from silence about buried pasts. But, perhaps, much more importantly, in Khan’s gestural embodiment of Rebecca Schneider’s call of ‘your battleground is your body’,Footnote44 he is able to resurrect the voices of shared ancestral subaltern voices, from his relative position of privilege, by putting his brown body on the (archival) line. And it is through such significant disruptions of the centre, from within the centre, that Khan repeatedly centralizes the Other, enabling them to speak for themselves, instead of being spoken for.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Akram Khan Company and Sadler’s Wells for inviting me to curate the conversation with Khan and his key collaborators on XENOS (dramaturg Ruth Little, rehearsal director Mavin Khoo, lighting designer Michael Hulls, music and composer Vincenzo Lamagna) on 3 June 2018. I am also grateful to the Society of Dance Research UK for inviting me to present at their Choreographic Forum on XENOS alongside First World War historian Emma Hanna on 18 June 2018. The provocations I wrote to frame these two contexts and events, categorised under ‘histories’, ‘the present’ and ‘the Other’, became the materials and reflections that have fuelled this article. I also wish to thank my generous peer reviewers whose recommendations have strengthened my enquiry significantly.

Notes

1. Throughout this article I use ‘Indian colonial soldiers’ to refer to colonial soldiers from the Indian subcontinent, who served Britain during WW1, at a time when the independent nations of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri Lanka did not exist. My use of this term is to emphasise that these colonial soldiers came from an undivided/pre-Partition India during this war.

2. See Royona Mitra, Akram Khan: Dancing New Interculturalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd, 2015).

3. 14–18 NOW Website, ‘About Us’, 2018. https://www.1418now.org.uk/about/ (accessed August 27, 2019).

4. Boyle in 14–18 NOW; 2020.

5. David Olusoga, ‘Historian David Olusoga Meets the Creatives Telling Untold Stories of Africa and War’ on 14–18 NOW Website, https://www.1418now.org.uk/news/historian-david-olusoga-meets-the-creatives-telling-untold-stories-of-africa-and-war/ (August 27, 2019).

6. Shashi Tharoor, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India (London: Penguin, 2018).

7. Ibid.

8. Susan Manning, Janice Ross, and Rebecca Schneider, ‘Archives’, in Futures of Dance Studies, ed. Manning, Ross, and Schneider (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2020), 15.

9. In the context of Indian performance traditions, the master archive of the Natyashastra is also casteist, as argued by Anurima Banerji in her article ‘The Natyashastra as Law of Movement in Indian Classical Dance’ in this special issue.

10. Please see Michelle Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence, Memory and the Photographic Record in Cambodia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014); Michelle Caswell, ‘Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy in Archives’, in The Library Quaterley: Information, Community, Policy 87, no. 3 (2017): 222–35.

11. Michelle Caswell, Ricardo Punzalan, and T-Kay Sangwand, ‘Critical Archival Studies: An Introduction’, in Caswell, Punzalan, and Sangwand, eds., special issue ‘Critical Archival Studies’, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1, no. 2 (2017): 1.

12. Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 19.

13. Ibid., 19.

14. Ibid., 17.

15. Ibid., 16.

16. Priya Srinivasan, Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labour (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2012), 178.

17. Michelle Caswell, Ricardo Punzalan, and T-Kay Sangwand, ‘Critical Archival Studies: An Introduction’, in Caswell, Punzalan, and Sangwand, eds., special issue ‘Critical Archival Studies’, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1, no. 2 (2017): 6.

18. Afua Hirsch, ‘Britain Doesn’t Glorify Its Violent: Past, It Gets High on It’, The Guardian, May 29, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/29/britain-glorify-violent-past-defensive-empire-drug (accessed August 27, 2020).

19. Ruth Little, email communication with the author, February 4, 2020.

20. Ibid.

21. For an analysis of these conditions see Shashi Tharoor, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India (London: Penguin, 2018).

22. Daljit Nagra, ‘The Last Post: Letters Home to India from the First World War’, The Guardian, February 21, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/feb/21/found-translation-indias-first-world-war (accessed August 27, 2020).

23. Ruth Little, ‘XENOS: Akram Khan and the Creative Team In Conversation’, June 22, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fddhNDlZag (accessed August 27, 2020).

24. See Royona Mitra, Akram Khan: Dancing New Interculturalism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

25. Akram Khan in Tim Reiss ‘Another Thing I wanted to Tell You..: On The Black Count’, February 14, 2019, https://www.akramkhancompany.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AnOther-Magazine-AK-2019.pdf (accessed August 27, 2020).

26. Priyamvada Gopal in Elliott Ross, ‘First Rule of Fight Club: Power Concedes Nothing Without a Struggle’, The Correspondent, February 5, 2020. https://thecorrespondent.com/270/first-rule-of-fight-club-power-concedes-nothing-without-a-struggle/294104250000-fa413f80 (accessed August 27, 2020).

27. Akram Khan in Cornelia Prior, ‘Autonomy’ Pilot Issue 8, April 12, 2018. https://www.akramkhancompany.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Pylot_Issue_08.pdf (accessed August 27, 2020).

28. Priya Srinivasan, Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labour (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2012), 17.

29. Rebecca Schneider, Performance Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), i.

30. Carol Martin, ‘Bodies of Evidence’, TDR: The Drama Review 50, no. 3 (2006): 8–15 (9).

31. Melissa Blanco Borelli, She is Cuba: The Genealogy of the Mulata Body (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 22.

32. Ibid., 26.

33. Ibid., 26–7.

34. André Lepecki, ‘The Body as Archive: Will to Re-Enact and the Afterlives of Dances’, Dance Research Journal 40, no. 2 (2010): 29–31.

35. Ibid., 31.

36. Mark Franko, ‘Introduction: The Power of Recall in a Post-Ephemeral Era’, in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, ed. Franko (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 3.

37. Ibid.

38. Prarthana Purkayastha, ‘Decolonising Human Exhibits: Dance, Re-enactment and Historical Fiction’, South Asian Diaspora 11, no. 2 (2019): 223–38 (231).

39. Ibid.

40. Ruth Little, Email Communication with the Author, February 4, 2020.

41. André Lepecki, ‘The Body as Archive: Will to Re-Enact and the Afterlives of Dances’, Dance Research Journal 40, no. 2 (2010): 28–48 (31).

42. Ibid.

43. Santanu Das, India Empire and First World War Culture: Writings, Images and Songs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 9.

44. Rebecca Schneider, Performance Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 9.