Abstract

Objectives: A recent report from the US Institute of Medicine indicated that identifying core elements of psychosocial interventions is a key step in successfully bringing evidence-based psychosocial interventions into clinical practice. Component studies have the best design to examine these core elements. Earlier reviews resulted in heterogeneous sets of studies and probably missed many studies. Methods: We conducted a comprehensive search of component studies on psychotherapies for adult depression and included 16 studies with 22 comparisons. Results: Fifteen components were examined of which four were examined in more than one comparison. The pooled difference between the full treatments and treatments with one component removed was g = 0.21 (95% CI: 0.03∼0.39). One study had sufficient statistical power to detect a small effect size and found that adding emotion regulation skills increased the effects of CBT. None of the other studies had enough power to detect an effect size smaller than g = 0.55. Only one study had low risk of bias. Conclusions: The currently available component studies do not have the statistical power nor the quality to draw any meaningful conclusion about key ingredients of psychotherapies for adult depression.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article

A recent report from the Institute of Medicine pointed once again at the need for identifying the key elements of psychosocial interventions that drive an intervention’s effect. Component studies are an important tool for examining how therapies work and they provide an elegant way to identify the active ingredients of psychotherapies. These studies decompose multicomponent therapies and compare the full therapy with a therapy in which one component is left out (dismantling studies) or in which a component is added to an existing therapy. We conducted a systematic review of component studies by searching an existing database of randomized trials examining the effects of psychological treatments of adult depression. This had the advantage that we probably missed few component, in contrast to earlier reviews, because component studies often do not use this design as index term.

Obiettivi: Un recente report dall'Istituto di Medicina USA ha indicato che identificare gli elementi centrali degli interventi psicosociali rappresenta un passaggio chiave al fine di portare con successo nella pratica clinica interventi basati sull'evidenza. I “component studies” hanno come obiettivo principale esaminare questi elementi centrali. Le prime reviews erano derivate da un set eterogeneo di studi e probabilmente mancavano molti lavori. Metodo: Abbiamo condotto una ricerca completa dei “component studies” su psicoterapie per la depressione adulta e incluso 16 studi con 22 confronti. Risultati: Quindici componenti erano esaminati di cui quattro in più di un confronto. La differenza cumulata tra i trattamenti completi e i trattamenti con una componente rimossa era g=0.21 (95% CI: 0.03∼0.39). Uno studio aveva una potenza statistica sufficiente da rilevare un piccolo effect size e trovato che aggiungendo le capacità di regolazione delle emozioni aumentavano gli effetti della CBT. Nessuno degli altri studi aveva abbastanza potere da rilevare un effect size minore di g=.55. Un solo studio aveva un basso rischio di bias. Conclusioni: I “component studies” attualmente disponibili non hanno potenza statistica nè la qualità per delineare alcuna conclusione significativa sugli elementi chiave delle psicoterapie per la depressione adulta.

Significato clinico o metodologico di questo articolo: Un recente report dall'Istituto di Medicina USA ha sottolineato ancora una volta la necessità di identificare gli elementi chiave degli interventi psicosociali che conducono all'effetto di un intervento. I “component studies” sono un importante strumento per esaminare come le terapie funzionano e forniscono un modo elegante per identificare gli elementi attivi delle psicoterapie. Questi studi decostruiscono le terapie multicomponenti e mettono a confronto la terapia globale con una terapia in cui una componente è lasciata fuori (studi di smantellamento) o in cui una componente è aggiunta a una terapia esistente. Abbiamo condotto una rassegna sistematica dei “component studies” attraverso una ricerca sui database esistenti di studi randomizzati esaminando gli effetti dei trattamenti psicologici della depressione adulta. Ciò ha avuto il vantaggio che probabilmente sono mancati pochi componenti, al contrario delle precedenti rassegne, perché i “component studies” spesso non usano questo disegno come termine indicizzato.

Zusammenfassung Fragestellung: Ein aktueller Bericht des US Institute of Medicine ergab, dass die Identifizierung von Kernelementen psychosozialer Interventionen ein wichtiger Schritt ist, um evidenzbasierte psychosoziale Interventionen erfolgreich in die klinische Praxis einzubringen. Komponentenstudien haben das beste Design, um diese Kernelemente zu untersuchen. Frühere Reviews führten zu heterogenen Studiensets und haben wahrscheinlich viele Studien verpasst. Methode: Wir führten eine umfassende Suche nach Komponentenstudien zu Psychotherapien bei Erwachsenen für Depression durch und schlossen 16 Studien mit 22 Vergleichen ein. Ergebnisse: Es wurden fünfzehn Komponenten untersucht, von denen vier in mehr als einem Vergleich untersucht wurden. Die gepoolte Differenz zwischen den Vollbehandlungen und den Behandlungen mit einer entfernten Komponente betrug g=0,21 (95% CI: 0,03∼0,39). Eine Studie hatte eine ausreichende statistische Power, um eine kleine Effektgröße zu erkennen, und fand heraus, dass das Hinzufügen von Fähigkeiten zur Emotionsregulation die Wirkung von CBT erhöht. Keine der anderen Studien hatte genug Power, um eine Effektgröße kleiner als g=0,55 zu erkennen. Nur eine Studie hatte ein geringes Bias-Risiko. Schlussfolgerung: Die derzeit verfügbaren Komponentenstudien haben weder die statistische Power noch die Qualität, um aussagekräftige Schlussfolgerungen über die wichtigsten Inhalte von Psychotherapien für Depressionen bei Erwachsenen zu treffen.

Objetivos: Um relatório recente do Instituto de Medicina dos EUA indicou que a identificação de elementos centrais das intervenções psicossociais é um passo fundamental para levar com sucesso as intervenções psicossociais baseadas em evidências para a prática clínica. Os estudos de componentes têm o melhor design para examinar esses elementos principais. Revisões anteriores resultaram em conjuntos heterogêneos de estudos e provavelmente perderam muitos estudos. Métodos: Realizamos uma pesquisa abrangente de estudos de componentes em psicoterapias para depressão em adultos e incluímos 16 estudos com 22 comparações. Resultados: Quinze componentes foram examinados, dos quais quatro foram examinados em mais de uma comparação. A diferença combinada entre os tratamentos completos e tratamentos com um componente removido foi g = 0,21 (IC 95%: 0,03∼0,39). Um estudo teve suficiente poder estatístico para detectar um pequeno tamanho de efeito e descobriu que adicionar habilidades de regulação de emoções aumentava os efeitos da TCC. Nenhum dos outros estudos tinham poder suficiente para detectar um tamanho de efeito menor que g = 0,55. Apenas um estudo apresentou baixo risco de viés. Conclusões: Os estudos de componentes disponíveis atualmente não têm o poder estatístico nem a qualidade para obter conclusão significativa sobre os principais ingredientes das psicoterapias para a depressão em adultos.

Significância clínica ou metodológica deste artigo: Um relatório recente do Instituto de Medicina apontou mais uma vez a necessidade de identificar os elementos-chave das intervenções psicossociais que impulsionam o efeito de uma intervenção. Estudos de componentes são uma ferramenta importante para examinar como as terapias funcionam e fornecem uma maneira elegante de identificar os ingredientes das psicoterapias. Estes estudos decompõem terapias multicomponentes e comparam a terapia completa com uma terapia em que um componente é deixado de fora (estudos de desmantelamento) ou em que um componente é adicionado a uma terapia existente. Realizamos uma revisão sistemática de estudos de componentes, pesquisando um banco de dados existente de ensaios randomizados examinando os efeitos dos tratamentos psicológicos da depressão em adultos. Isso teve a vantagem de provavelmente perdermos poucos componentes, em contraste com as revisões anteriores, porque os estudos de componentes geralmente não usam esse design como termo de índice.

目的:美國國家醫學研究院最近的一份報告指出, 辨識出心理社會介入的核心要素是成功地將實證為基礎的心理社會介入引進臨床實務的關鍵步驟。成份研究具有檢視這些核心要素的最佳設計。早期的回顧研究產生參差不齊的研究並可能遺漏許多研究。方法:我們針對為成人憂鬱進行的心理治療進行詳盡的成份蒐尋研究,包括16項研究,涵蓋22組比較。結果:共檢視15個成份,其中四個成份有進行多於一組的比較。比較完整治療與移除一項成份的治療,其合併差異為 g=0.21(95% CI: 0.03∼0.39)。其中一項研究具備足夠的統計考驗力,能偵測到小的效果值,並且發現添加情緒調節技巧可增加認知行為治療的效果。其他的研究則皆無足夠的統計考驗力來偵測 g 小於 0.55之效果值。只有一項研究具有低度的偏差危險。結論:現有的成份研究並無足夠的統計考驗力或是品質,以形成任何關於成人憂鬱心理治療之核心成份的有意義結論。

本文在臨床或方法學上的重要性:美國國家醫學研究院最近的一份報告再次指出,有必要辨識出導致心理社會介入有效的核心要素。成份研究在檢視治療是如何產生功效上,是個重要的工具;他們同時能以簡鍊的方式辨識出心理治療的活躍要素。這些研究分解多重成份的治療,並將完整治療與未包括其中一個成份的治療(即,拆解研究),或是與一個現存的治療再添加某一成分的治療做比較。我們透過蒐尋現有針對成人憂鬱的心理治療成效進行隨機詴驗之資料庫,進行系統性的成份研究回顧。與早期的回顧研究相較,這樣做有些優點,可能可以錯失較少的成份,因為成份研究通常不會以這個研究設計為其關鍵字。

Introduction

It is well established that several psychological interventions are effective in the treatment of depression, including cognitive behavior therapy (Churchill et al., Citation2001; Cuijpers et al., Citation2013), interpersonal psychotherapy (Cuijpers et al., Citation2011; Cuijpers, Donker, Weissman, Ravitz, & Cristea, Citation2016), problem-solving therapy (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, Citation2007), behavioral activation (Cuijpers, van Straten, & Warmerdam, Citation2007; Ekers, Richards, & Gilbody, Citation2008), and possibly psychodynamic therapies (Driessen et al., Citation2015; Leichsenring & Rabung, Citation2008). It is less well established, however, how these therapies work and which mechanisms are responsible for their effects (Kazdin, Citation2007, Citation2009).

Understanding how psychotherapies work is important, because this may result in more knowledge about how to optimize treatments for depression. Knowledge about how therapies work may also result in a better understanding of the causal mechanisms that lead to depression (Whisman, Citation1993). Optimizing treatments for depression is important because modeling studies estimate that current treatments can reduce the disease burden associated with depression by only about one third, in optimal conditions (Andrews, Issakidis, Sanderson, Corry, & Lapsley, Citation2004).

Component studies are an important tool for examining how therapies work and they provide an elegant way to identify the active ingredients of psychotherapies (Borkovec & Costonguay, Citation1998). These studies decompose multicomponent therapies and compare the full therapy with a therapy in which one component is left out (dismantling studies) or in which a component is added to an existing therapy (additive studies; Bell, Marcus, & Goodlad, Citation2013). Because of their experimental design, the strength of evidence resulting from component studies is high. If a component study finds a difference between a therapy with a component and a therapy without that component, this indicates that this component is indeed responsible for (part of) the effects of the intervention. This is in contrast with research on mediators, which is always indirect and correlational, and when a significant mediator is found it is always possible that a third unknown variable is responsible for the change in outcome as well as the change in the mediator (Kazdin, Citation2007).

A recent report from the US Institute of Medicine pointed once again at the need for identifying the key elements of psychosocial interventions that drive an intervention’s effect (Institute of Medicine, Citation2015). This report considered the identification of these elements to be one of the key steps entailed in successfully bringing an evidence-based psychosocial intervention into clinical practice.

The first major review and meta-analysis of component studies did not find specific components that are responsible for part of the effects of therapies (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001). This finding was one of the reasons why some researchers assume that the effects of therapies are not caused by the specific techniques used in these therapies (Luborsky et al., Citation2002; Luborsky, Singer, & Luborsky, Citation1975; Wampold, Citation2001), but by universal, non-specific factors that are common to all therapies, such as the therapeutic alliance and expectancies of the patient. If dismantling studies don’t find effective components, then that could be seen as an indication that these components don’t exist and as support for the assumption that it is not these components that cause change, but the universal mechanisms. In an important early review of 27 dismantling studies suggestively entitled “Where oh where are the specific ingredients?”, the authors did not find many indications for significant components and concluded that therapies are probably not working through specific techniques, but through non-specific, universal mechanisms (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001).

A second major review examined a much larger set of component studies and found that dismantling studies did not result in significant differences between the full and the partial treatment (in which one component was left out; Bell et al., Citation2013). They did find, however, a small but significant effect when a component was added to an existing therapy and this effect was larger at follow-up. The authors concluded that specific components may add to the effects of existing treatments. Their results did not support the conclusion of the earlier meta-analysis that it is universal factors, and not specific components, that are responsible for change. This meta-analysis has been criticized (Flückiger, Del Re, & Wampold, Citation2015; Wampold & Imel, Citation2015), and a re-analysis with longitudinal meta-analytical methods could not replicate the finding that effects of components were found at the longer term (Flückiger et al., Citation2015). Despite this criticism, however, the meta-analysis of Bell and colleagues is the most comprehensive and most recent meta-analysis of component studies.

The review by Bell and colleagues also has a number of limitations. One important limitation was that the quality of the included studies was not assessed. It is well known that the quality of randomized trials can have a large impact on the effect sizes found in these trials (Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon, & Andersson, Citation2010; Higgins et al., Citation2011). A meta-analysis can never be better than the studies it summarizes, no matter how sophisticated the meta-analysis is done.

Another problem of Bell et al. (Citation2013) is that the statistical power of most published component studies is low (Kazdin & Whitley, Citation2003). While the authors discussed this problem extensively, they did not quantify the statistical power of the included studies nor the corresponding effect sizes these studies could in theory evidence, considering their sample sizes. Most published dismantling studies are markedly underpowered and consequently the absence of significant effects in these studies cannot reliably lead to the conclusion that the components examined are indeed not effective. Non-significant results from underpowered studies can in no way be considered as evidence of absence of effects.

One more problem of Bell et al. (Citation2013) is that it was focused on a broad range of health problems, ranging from depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder to tension headaches, rheumatoid arthritis, and marital discord. Due to the large differences in the examined components, the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies was very high. Although the authors found that statistical heterogeneity was low, this has to be considered with caution because the uncertainty around statistical heterogeneity can be considerable and makes it impossible to assess the true statistical heterogeneity (Ioannidis, Patsopoulos, & Evangelou, Citation2007).

A final problem of Bell et al. (Citation2013) was that it was mostly based on systematic searches in bibliographical databases using search terms to identify component studies (although studies were also identified through handsearching key journals). But because many component studies do not use this design as index term, it is unlikely that all component studies from the past 30 years are identified with such search strings (Bell et al., Citation2013).

In the current meta-analysis, we partially solved this problem by using an existing database of studies on psychological treatments of adult depression, which uses broad search strings for identifying all studies in this field and is updated every year (Cuijpers, van Straten, Warmerdam, & Andersson, Citation2008). We examined all included studies and selected all component studies. Hence it is improbable that we missed many studies, and we also reduced the clinical heterogeneity of the target problems by focusing specifically on depression. This emphasis on one disorder also makes it also possible to examine whether there are groups of component studies focusing on the same components, and whether pooled effects of these studies result in significant outcomes. We conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of dismantling studies of psychotherapies for adult depression. In it, we not only focus on the effects of (groups of) components, but also on the quality of the included studies and the statistical power of these studies.

Methods

Identification and Selection of Studies

We used an existing database of studies on the psychological treatment of depression. This database has been described in detail elsewhere (Cuijpers et al., Citation2008), and has been used in a series of earlier published meta-analyses (www.evidencebasedpsychotherapies.org). For this database we searched four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and the Cochrane database of randomized trials) by combining terms (both MeSH terms and text words) indicative of depression and psychotherapies, with filters for randomized controlled trials. We also checked the references of earlier meta-analyses on psychological treatments for the included disorders. The database is continuously updated and was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to January 2016).

We included component studies that were: (a) a randomized trial (b) in which a psychological treatment (c) for adult depression was (d) compared with the same psychological treatment but with one component added or removed. We defined a component as a specific ingredient that is hypothesized to be critical to the success of the treatment (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001). We only included trials in which the full therapy was compared with the adjusted therapy in which one component was removed or added, when the content of this component was associated with the therapy. Although we tried to be as inclusive as possible, we excluded studies in which it was not clear whether an actual ingredient was examined, such as religious versus non-religious therapy (for religious people) and culturally adapted versus non-adapted therapy. We also excluded other types of components, such as the treatment format or characteristics of the therapist were not included to keep clinical heterogeneity as small as possible. For example, face-to-face therapies compared with guided self-help (in which part of the contact time with the therapist was reduced) were not included in the review. We also did not include trials in which professional and paraprofessional therapists were compared with each other. Trials in which a therapy was compared with non-directive supportive counseling were also excluded, assuming that the non-directive approach contains the elements that every therapy offers. We excluded these trials because they provide the effects of all components of a therapy taken together and compared with the basic empathy and support in the non-directive approach, instead of specific components (Cuijpers et al., Citation2012). We made an exception for studies comparing experiential therapy with non-directive counseling, because experiential therapy is built on the principles of non-directive counseling and can be seen as an extension or additional component to it (Greenberg & Watson, Citation1998).

Depression could be established with a diagnostic interview or with a score above a cut-off on a self-report measure. The therapies could be delivered individually, in groups, as guided self-help, or by telephone. Co-morbid mental or somatic disorders were not used as an exclusion criterion. Studies on children and adolescents (below 18 years of age) were excluded. We also excluded maintenance studies, aimed at people who had already recovered or partly recovered after an earlier treatment, and studies that did not report sufficient data to calculate standardized effect sizes. Studies in English, German, and Dutch were considered for inclusion.

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

We assessed the validity of included studies using four criteria of the “Risk of bias” assessment tool, developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., Citation2011). This tool assesses possible sources of bias in randomized trials, including the adequate generation of allocation sequence; the concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors; when only self-report measures were used for the assessment of depression we rated this as positive as well); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). We did not rate selective outcome reporting, because there are important flaws in its assessment (Page & Higgins, Citation2016), such as the conflation of nonreporting with selective reporting of outcomes, and because most psychotherapy trials are still not prospectively registered (Bradley, Rucklidge, & Mulder, Citation2017).

Two independent researchers assessed the validity of the included studies and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We also examined whether the interventions met the criteria for a “bona fide” therapy as defined by Wampold et al. (Citation1997). This meant that a treatment had to involve a therapist who had at least a master’s degree, who met face to face with the client, developed a relationship with the client. Furthermore, the treatment had to contain at least two of the following four elements: (a) The treatment was based on an established treatment that was cited; (b) a description of the treatment was contained in the article; (c) a manual was used to guide administration of the treatment; and (d) active ingredients of the treatment were identified and cited. The study’s research design also had to involve a comparison of one group with another group, and one of the following two conditions had to be satisfied: (a) One, two, or three ingredients of the treatment were removed, leaving a treatment that would be considered logically viable (i.e., coherent and credible), or (b) one, two, or three ingredients that were compatible with the whole treatment and were theoretically or empirically hypothesized to be active were added to the treatment, providing a “super treatment” (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001).

We did not assess the quality of the interventions in other ways, because we examined several criteria for intervention quality in a large, previous meta-analysis, but found no indication that these criteria were associated with the effects of the interventions (Cuijpers et al., Citation2010).

Meta-analyses

The effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test was calculated (Hedges’ g) for each comparison between the full psychotherapy and the partial therapy (in which one component was removed). The full psychotherapy could consist of an existing therapy to which a component was added (additive studies), or from which a component was removed (dismantling studies). This allowed us to examine the pooled effect of all component studies in one analysis.

Effect sizes of 0.8 can be assumed to be large, while effect sizes of 0.5 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0.2 are small (Cohen, Citation1988). We calculated effect sizes by subtracting (at post-test) the average score of the psychotherapy group from the average score of the control group, and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes, we corrected the effect size for small sample bias (Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985). If means and standard deviations were not reported, we used the procedures of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (see below) to calculate the effect size using dichotomous outcomes; and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such as t-value or p-value) to calculate the effect size. If a study reported more than one depression outcomes we pooled the effect sizes within each study, before pooling across studies, so that each study only had one effect size.

In order to calculate effect sizes we used all measures examining depressive symptoms (such as the Beck Depression Inventory/BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, Citation1961), the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Citation1996) or the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression/HAMD-17 (Hamilton, Citation1960)). To calculate pooled mean effect sizes, we used the computer program Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.3070; CMA). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we employed a random effects pooling model in all analyses. We also explored whether it was possible to pool secondary outcomes from the trials, but found that these were too heterogeneous to be pooled.

As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2 -statistic, which is an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Citation2003). We calculated 95% confidence intervals around I2 (Ioannidis et al., Citation2007), using the non-central chi-squared-based approach within the heterogi module for Stata (Orsini, Bottai, Higgins, & Buchan, Citation2006).

We conducted subgroup analyses according to the mixed effects model, in which studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model.

We tested for publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000), which yields an estimate of the effect size after the publication bias has been taken into account (as implemented in CMA). We also conducted Egger’s test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant.

Power Calculations

We expected to find only a limited number of component studies. Furthermore, we expected that the difference between a full and a partial therapy would be limited (resulting in small effect sizes) because this only measures the effects of one component. Power and the sample size of included studies is therefore a crucial element in a systematic review of these studies (Kazdin & Whitley, Citation2003). Because previous meta-analyses did describe the problem of low power of most component studies extensively, but did not examine this problem quantitatively, we decided to examine the power of included studies in more detail.

We first calculated the effect size for each study that could be detected with the sample size in that individual study. We conducted these analyses with G*Power software (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Citation2007), assuming a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05.

The threshold for a clinically relevant treatment effect in depression has been estimated to be g = 0.24 (Cuijpers, Turner, Koole, van Dijke, & Smit, Citation2014). Because dismantling studies should be expected to result in small effect sizes, we calculated in G*Power how many participants should be included in a trial to detect an effect size of at least g = 0.24. We found that the required number of participants in such a trial was 548. In order to get an idea of the statistical power of the included dismantling studies we calculated for each study separately the percentage of the 548 participants that was included in the trial.

Then, for meta-analyses, in which more than one study was pooled, and different power calculations (based on number of studies and number of participants per study) are needed, we conducted power calculations according to the procedures described by Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (Citation2009).

Results

Selection and Inclusion of Studies

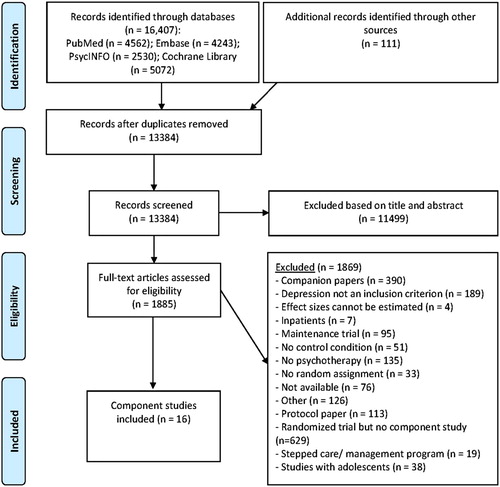

After examining a total of 16,407 abstracts (13,384 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 1,885 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 1,868 of the retrieved papers. The PRISMA flowchart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in . A total of 16 studies met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis. Selected characteristics of the included studies are reported in , and references of the included studies are listed in Appendix 1.

Table I. Component studies of psychotherapy for adult depression.

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 16 studies included a total of 22 comparisons between a full and partial therapy. A total of 1146 patients participated in the trials, 499 in the full therapies and 647 in the partial therapies (the mean number of patients per comparison was 52 and respectively 26 per arm). In the 22 included comparisons, 15 separate components were examined of which 4 were examined in more than one comparison (three components were examined in three comparisons, and one in two comparisons). Nine of the 22 comparisons had an additive design and the other 13 had a dismantling design. In two of the 22 comparisons, the full therapy had more sessions than the partial therapy.

In 10 studies patients had to meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder, while in the other six studies patients had to score above the cut-off on a self-report measure. Ten of the 16 studies were aimed at adults in general, while the other 6 were aimed at more specific target groups, like students and patients with co-morbid general medical disorders. In 16 comparisons CBT was examined, the other 6 examined another type of therapy. In 10 comparisons an individual treatment format was used, 12 used a group or mixed format.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the 16 included studies was not optimal. Only two studies reported an adequate sequence generation. One of the studies reported that allocation to conditions was properly concealed. One study reported blinding of outcome assessors, while another 12 used only self-report outcomes. Two studies conducted intention-to-treat analyses. Only one study met four criteria, one met two criteria and the remaining 14 studies met one or none of the criteria.

Overall Effects of Components in Dismantling Studies

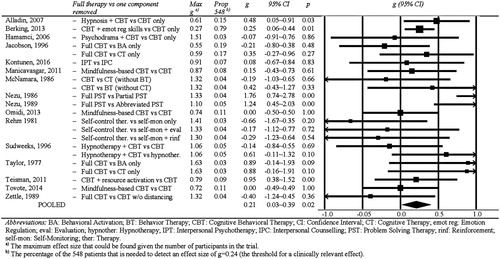

The effect sizes found for each study (full vs partial therapy) are presented in the forest plot in . The effect sizes indicating the difference between the full and partial therapies range from g=−0.66 to g = 1.76 (median g = 0.08). The pooled effect size for all studies together was g = 0.21 (95% CI: 0.03∼0.39; p = .02), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 =39). Exclusion of the two comparisons of interventions that did not meet criteria for a bona fide therapy, resulted in a comparable effect size (g = 0.20), which was still significant, and comparable levels of heterogeneity.

In six studies, more than one effect size indicating the difference between a full and partial therapy was calculated (4 studies had two effect sizes, and one study had three effect sizes). Because these effect sizes were not independent of each other, they may have artificially reduced heterogeneity and influenced the effect sizes. We conducted two separate analyses to examine this. In the first analysis we only included the largest effect size from each study, and in the second only the smallest effect size. As can be seen in , the effect sizes and levels of heterogeneity were comparable to those in the main analyses.

Table II. Dismantling studies of psychotherapies for adult depression: pooled effect sizes.

In four of the 22 comparisons a significant difference between the full and the partial therapy was found, one in which hypnosis was added to CBT (Alladin & Alibhai, Citation2007), another one in which emotion regulation skills were added to CBT (Berking et al., Citation2013), and two in which problem-solving therapy was compared with partial or abbreviated problem-solving therapy (Nezu, Citation1986; Nezu & Perri, Citation1989).

Eleven studies reported longer term outcomes. In we have reported the outcomes for 5–8 weeks, 6 and 12 months follow-up. None of the pooled effect sizes was significant, possibly because of low statistical power.

We also conducted a series of subgroup analyses (), but did not find any indication that the effect size differed significantly between subgroups (the number of sessions was the same in the full and partial therapies or not the same; the component was added to an existing therapy or removed; CBT vs other types; individual vs other treatment format; adults in general vs more specific subgroups; three or four criteria for low risk of bias vs less criteria).

We did find that the pooled effect size of the additive studies (in which a component was added to an existing therapy) was significant (g = 0.22). But this was no longer significant when the large study from Berking et al. (Citation2013) was removed (g = 0.18; 95% CI: −0.02∼0.38; p = .008). The pooled effect size of the dismantling studies was not significant (p > .1). However, the effect size was comparable to that of the additive studies (g = 0.26). This may have been not significant because of low power.

We found no indication for publication bias (Egger’s test of the intercept: p > .1; Duvall & Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure: adjusted and unadjusted effect sizes are identical, zero imputed studies).

Power Calculations

We calculated for each study how large the effect size was that could be found given the number of participants in the trial (). As can be seen, there was one study that had sufficient power to detect an effect size of g = 0.27 (Berking et al., Citation2013). The effect sizes that could be detected by the other studies ranged from g = 0.55 to g = 1.63. (as indicated earlier: the threshold for clinical relevance for treatments of depression has been estimated to be g = 0.24 (Cuijpers et al., Citation2014)). Thirteen comparisons (59%) had only sufficient power to detect effect sizes of g > 1.00.

As indicated earlier, we also calculated for each included study the percentage of the 548 patients that is needed to detect an effect size of g = 0.24 (the threshold for a clinically relevant effect). The results are given in and show that one large trial (Berking et al., Citation2013) included 79% of these 548 patients, while none of the other studies included more than 19% of the 548 patients needed to detect a clinically relevant effect size. Moreover, 16 of the 22 comparisons had less than 10% of the needed 548 patients.

Effects for Specific Components

There were several comparisons that examined the same components (, subsets of studies). As can be seen, the three studies in which cognitive behavior therapy was compared with cognitive therapy only (the behavioral activation component was removed) resulted in a significant effect size of g = 0.46 (95% CI: 0.01∼0.91) with zero heterogeneity. The other subsets of comparisons did not result in significant effect sizes, but the number of studies in each of these subsets was very small (three with three comparisons and one with two comparisons).

We conducted power calculations based on the number of studies and number of participants per study, to examine how many studies would have been needed to find a significant effect. In these calculations we assumed that the effect size found was the true effect size, and assuming that the number of included patients was the same as in the included trials. As shown in , the number of studies needed to show that a subset of studies resulted in significant outcomes was high for the subsets resulting in small effect sizes. For instance, the subset of studies comparing full CBT with behavioral activation only resulted in an effect size of g = 0.06, and a total of 956 studies with the same sample size would be needed to find this effect size to be significantly different from zero; 692 trials would be needed to show that mindfulness-based CBT is more effective than CBT.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of component studies by searching an existing database of randomized trials examining the effects of psychological treatments of adult depression. This had the advantage that we probably missed few component, in contrast to earlier reviews, because component studies often do not use this design as index term. The largest and most recent review of component studies (Bell et al., Citation2013) identified only four studies on depression, while in the current meta-analysis we identified 16 component studies on therapies for depression with 22 comparisons between a full and partial therapy. In these comparisons, 15 separate components were examined in which 4 were examined in more than one comparison (three components were examined in three comparisons, and one in two comparisons).

In our review, we explicitly focused on the power of component studies, and found that only one study came close to having sufficient statistical power to detect a clinically significant effect (Berking et al., Citation2013). This study also found a significant effect of the component (emotional-regulation skills in addition to CBT compared to CBT alone), and because risk of bias was low, the evidence that this component was effective can be considered quite strong. Evidently, this finding has to be replicated in further trials. Furthermore, there is a considerable risk of researcher allegiance in this study because the first author was also the author of the manual of the intervention. This study does show, however, that it is not impossible that significant components can be identified in well-powered dismantling studies.

One other significant component was identified after pooling the results of three studies comparing full CBT (consisting of CBT plus behavioral activation) with cognitive restructuring alone (without the behavioral activation). This finding suggests that behavioral activation is one of the effective components of CBT, and leaving it out reduces the effects of CBT considerably. However, there was considerable risk of bias in these studies and the results should therefore be considered with caution. Nonetheless, this set of studies also shows that (series of) dismantling studies can indeed identify effective components of therapies.

The other 13 components that were examined in the dismantling studies we identified in our search did not in any way have sufficient power to detect an effective component. Except for the earlier mentioned study by Berking et al. (Citation2013), none of the studies had more than 19% of the participants that are needed to detect a significant effect of a component, and 16 of the 22 comparisons had less than 10% of the participants that are needed. Moreover, none of the studies (except Berking et al., Citation2013) had enough power to detect an effect size smaller than g = 0.55, and 13 of the 22 comparisons only had enough power to detect an effect size larger than g = 1.0. So none of these studies came even close to an effect size like for instance the one that would separate the effects of antidepressants from placebo (g = 0.31; Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell, & Rosenthal, Citation2008).

We also pooled the results of all component studies and found that these pooled effects were significantly different from zero, suggesting that there may be some components that are actually effective ingredients of therapies. The additive studies showed a significant effect size, and although the effect size of the dismantling studies was not significant, it was about as large as that of the additive studies. Consequently, the lack of significance could very well be caused by low statistical power. Nonetheless, the pooling of component studies is generally not very useful, especially when the statistical power is low. When only a small number of components are indeed effective ingredients, and the statistical power of the included studies is small, it is very well possible that the pooled effects of all studies are not significant, while in fact several components do in fact have significant effects.

Apart from the statistical power, we also focused on the quality of the included component studies and found that only one of the 16 included studies had low risk of bias. This body of research can, therefore, in no way be considered as evidence that specific components of psychotherapies are not effective and that all effects can be explained by non-specific or universal effects (Ahn & Wampold, Citation2001; Wampold, Citation2000). Almost none of the studies has sufficient power to detect effective components and the risk of bias is so high in these studies that it is difficult to draw any conclusions from these studies at all. The one exception of a trial with more or less sufficient power and low(er) risk of bias, did indicate the presence of a significant effect for a component. On the other hand, this body of research can also not be considered as evidence that specific components of psychotherapies do exist. The evidence is simply too weak to draw any conclusions. The pooled significant effect of all studies together could very well be the result of bias in the included studies and there were simply too few studies with low risk of bias to draw any conclusion.

We did not assess researcher allegiance in the included studies. Most instruments of researcher allegiance focus on trials where two therapies are directly compared with each other. That is not the case for the studies in our review. Because the trials in the current study examined only one therapy (with or without one component) it is difficult to assess whether authors had allegiance toward this treatment. However, it is very well possible that allegiance played a role in these studies, and that the outcomes were affected, making them even less credible.

Apart from these methodological issues and the uncertainties they bring about, there are two important caveats to this research. The first is that whether or not distinct specific components of psychotherapies do exist and are effective is a separate issue from whether or not universal factors are responsible for therapeutic change. Lack of evidence for the former is not sufficient evidence for the latter. Universal factors must come with evidence of their own and cannot be postulated on the basis of insufficient evidence (or indeed lack thereof) for specific factors. The second is that it is very likely that not all purported components of therapeutic packages are equal, not should they be expected to be equally relevant. The theory behind most psychotherapy packages usually carries a degree of subjectivity and is rooted in the developers’ clinical experience and its subsequent interpretation. Consequently, some of the components included in the package might have simply been based on erroneous intuitions and looking for evidence to their existence or effectiveness doomed to fail.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, the number of included studies was relatively low, and both the quality and the statistical power in these studies to detect effects of the examined components is very low. Second, the components that were examined in the included studies differed widely, with 15 different components examined in 16 studies. Only three components were examined in three studies and 11 were examined in only one study. Considering that effective components had small effect sizes, many more trials examining the same components would be needed to detect whether these are effective or not if we were to use meta-analytic techniques. Third, we did not assess the quality of the interventions, because previous criteria of intervention quality did not indicate that these were associated with the effects of the interventions. However, this may be related to problems with measuring intervention quality. It is possible therefore that this may have influenced outcomes.

Conclusion

Based on this set of studies, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that we simply don’t know neither if specific components of specific therapies are effective ingredients of these therapies, nor that all effects are caused by universal, nonspecific factors that are common to all therapies. If we really want to examine effective components as recommended in the IOM report on psychosocial interventions, we need studies with lower risk of bias and considerably larger than the ones that have been conducted so far.

ORCID

Pim Cuijpers http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5497-2743

Mirjam Reijnders http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4272-2576

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahn, H., & Wampold, B. E. (2001). Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta-analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 251–257. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.251

- Alladin, A., & Alibhai, A. (2007). Cognitive hypnotherapy for depression: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55(2), 147–166. doi: 10.1080/00207140601177897

- Andrews, G., Issakidis, C., Sanderson, K., Corry, J., & Lapsley, H. (2004). Utilising survey data to inform public policy: Comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 184(6), 526–533. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.526

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-II, Beck depression inventory: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

- Bell, E. C., Marcus, D. K., & Goodlad, J. K. (2013). Are the parts as good as the whole? A meta-analysis of component treatment studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(4), 722–736. doi: 10.1037/a0033004

- Berking, M., Ebert, D., Cuijpers, P., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Emotion regulation skills training enhances the efficacy of inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(4), 234–245. doi: 10.1159/000348448

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Borkovec, T. D., & Costonguay, L. G. (1998). What is the scientific meaning of empirically supported therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 136–142. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.136

- Bradley, H. A., Rucklidge, J. J., & Mulder, R. T. (2017). A systematic review of trial registration and selective outcome reporting in psychotherapy randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135, 65–77. doi: 10.1111/acps.12647

- Churchill, R., Hunot, V., Corney, R., Knapp, M., McGuire, H., Tylee, A., & Wessely, S. (2001). A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technology Assessment, 5(35), 1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta5350

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Andersson, G., Quigley, L., Kleiboer, A., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 58(7), 376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702

- Cuijpers, P., Donker, T., Weissman, M. M., Ravitz, P., & Cristea, I. A. (2016). Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(7), 680–687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141

- Cuijpers, P., Driessen, E., Hollon, S. D., van Oppen, P., Barth, J., & Andersson, G. (2012). The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003

- Cuijpers, P., Geraedts, A. S., van Oppen, P., Andersson, G., Markowitz, J. C., & van Straten, A. (2011). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(6), 581–592. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10101411

- Cuijpers, P., Turner, E. H., Koole, S. L., van Dijke, A., & Smit, F. (2014). What is the threshold for a clinically relevant effect? The case of major depressive disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 374–378. doi: 10.1002/da.22249

- Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., & Andersson, G. (2010). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: A meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychological Medicine, 40(2), 211–223. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006114

- Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., & Warmerdam, L. (2007). Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(3), 318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001

- Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Warmerdam, L., & Andersson, G. (2008). Psychological treatment of depression: A meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 36. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-36

- Driessen, E., Hegelmaier, L. M., Abbass, A. A., Barber, J. P., Dekker, J. J. M., Van, H. L., … Cuijpers, P. (2015). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis update. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.004

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

- Ekers, D., Richards, D., & Gilbody, S. (2008). A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychological Medicine, 38(5), 611–623. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001614

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2015). The sleeper effect: Artifact or phenomenon—a brief comment on Bell et al. (2013). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2), 438–442. doi: 10.1037/a0037220

- Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. (1998). Experiential therapy of depression: Differential effects of client-centered relationship conditions and process experiential interventions. Psychotherapy Research, 8(2), 210–224. doi:10.1093/ptr/8.2.210 doi: 10.1080/10503309812331332317

- Hamamci, Z. (2006). Integrating psychodrama and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat moderate depression. Arts in Psychotherapy, 33(3), 199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2006.02.001

- Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gotzsche, P. C., Juni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., … Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343(2), d5928–d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 327(7414), 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Institute of Medicine. (2015). Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: A framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Ioannidis, J. P. A., Patsopoulos, N. A., & Evangelou, E. (2007). Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 335(7626), 914–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39343.408449.80

- Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., Gollan, J. K., … Prince, S. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 295–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.295

- Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

- Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 418–428. doi: 10.1080/10503300802448899

- Kazdin, A. E., & Whitley, M. K. (2003). Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504

- Kontunen, J., Timonen, M., Muotka, J., & Liukkonen, T. (2016). Is interpersonal counselling (IPC) sufficient treatment for depression in primary care patients? A pilot study comparing IPC and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Journal of Affective Disorders, 189(1), 89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.032

- Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2008). Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 300(13), 1551–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.13.1551

- Luborsky, L., Rosenthal, R., Diguer, L., Andrusyna, T. P., Berman, J. S., Levitt, J. T., … Krause, E. D. (2002). The dodo bird verdict is alive and well—mostly. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(1), 2–12. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.2

- Luborsky, L., Singer, B., & Luborsky, L. (1975). Comparative studies of psychotherapies: Is it true that everyone has won and all must have prizes? Archives of General Psychiatry, 32(8), 995–1008. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760260059004

- Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Schutte, N. S. (2007). The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(1), 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005

- Manicavasgar, V., Parker, G., & Perich, T. (2011). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1), 138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.027

- McNamara, K., & Horan, J. J. (1986). Experimental construct validity in the evaluation of cognitive and behavioral treatments for depression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(1), 23–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.33.1.23

- Nezu, A. M. (1986). Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 196–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.196

- Nezu, A. M., & Perri, M. G. (1989). Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: An initial dismantling investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 408–413. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.408

- Omidi, A., Mohammadkhani, P., Mohammadi, A., & Zargar, F. (2013). Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(2), 142–146. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.8018

- Orsini, N., Bottai, M., Higgins, J., & Buchan, I. (2006). HETEROGI: Stata module to quantify heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stata. Retrieved from http://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s449201.htm

- Page, M. J., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2016). Rethinking the assessment of risk of bias due to selective reporting: A cross-sectional study. Systematic Reviews, 5, 108. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0289-2

- Rehm, L. P., Kornblith, S. J., O’Hara, M. W., Lamparski, D. M., Romano, J. M., & Volkin, J. I. (1981). An evaluation of major components in a self-control therapy program for depression. Behavior Modification, 5(4), 459–489. doi: 10.1177/014544558154002

- Sudweeks, C. (1996). Effects of cognitive group hypnotherapy in the alteration of depressogenic schemas. Washington, DC: Washington State University.

- Taylor, F. G., & Marshall, W. L. (1977). Experimental analysis of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(1), 59–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01173505

- Teismann, T., Dymel, W., Schulte, D., & Willutzki, U. (2011). Ressourcenorientierte Akutbehandlung unipolarer Depressionen: Eine randomisierte kontrollierte Psychotherapiestudie. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 61(7), 295–302. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270453

- Tovote, K. A., Fleer, J., Snippe, E., Peeters, A. C., Emmelkamp, P. M., Sanderman, R., … Schroevers, M. J. (2014). Individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for treating depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 37(9), 2427–2434. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2918

- Turner, E. H., Matthews, A. M., Linardatos, E., Tell, R. A., & Rosenthal, R. (2008). Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358(3), 252–260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779

- Wampold, B. E. (2000). Outcomes of individual counseling and psychotherapy: Empirical evidence addressing two fundamental questions. In Handbook of counseling psychology (3rd ed., pp. 711–739). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Wampold, B. E. (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate; The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work, second edition. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wampold, B. E., Mondin, G. W., Moody, M., Stich, F., Benson, K., & Ahn, H. N. (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, ‘All must have prizes.’ Psychological Bulletin, 122, 203–215. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.203

- Whisman, M. A. (1993). Mediators and moderators of change in cognitive therapy of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 248–265. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.248

- Zettle, R. D., & Rains, J. C. (1989). Group cognitive and contextual therapies in treatment of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 436–445. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198905)45:3<436::AID-JCLP2270450314>3.0.CO;2-L

Appendix 1

References That Were Used in the Final Analyses

Alladin, A., & Alibhai, A. (2007). Cognitive hypnotherapy for depression: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55(2), 147–166. doi:10.1080/00207140601177897

Berking, M., Ebert, D., Cuijpers, P., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Emotion regulation skills training enhances the efficacy of inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(4), 234–245. doi:10.1159/000348448

Hamamci, Z. (2006). Integrating psychodrama and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat moderate depression. Arts in Psychotherapy, 33(3), 199–207. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2006.02.001

Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., Gollan, J. K., … Prince, S. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 295–304. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.295

Kontunen, J., Timonen, M., Muotka, J., & Liukkonen, T. (2016). Is interpersonal counseling (IPC) sufficient treatment for depression in primary care patients? A pilot study comparing IPC and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Journal of Affective Disorders, 189(1), 89–93. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.032

Manicavasgar, V., Parker, G., & Perich, T. (2011). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1), 138–144. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.027

McNamara, K., & Horan, J. J. (1986). Experimental construct validity in the evaluation of cognitive and behavioral treatments for depression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(1), 23-30. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.33.1.23

Nezu, A. M. (1986). Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 196–202. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.196

Nezu, A. M., & Perri, M. G. (1989). Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: An initial dismantling investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 408–413. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.408

Omidi, A., Mohammadkhani, P., Mohammadi, A., & Zargar, F. (2013). Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(2), 142–146. doi:10.5812/ircmj.8018

Rehm, L. P., Kornblith, S. J., O’Hara, M. W., Lamparski, D. M., Romano, J. M., & Volkin, J. I. (1981). An evaluation of major components in a self-control therapy program for depression. Behavior Modification, 5(4), 459–489. doi:10.1177/014544558154002

Sudweeks, C. (1996). Effects of cognitive group hypnotherapy in the alteration of depressogenic schemas. Washington, DC: Washington State University.

Taylor, F. G., & Marshall, W. L. (1977). Experimental analysis of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(1), 59–72. doi:10.1007/BF01173505

Teismann, T., Dymel, W., Schulte, D., & Willutzki, U. (2011). Resource-focused treatment for unipolar depression: A randomized controlled psychotherapy study. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 61(7), 295–302. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1270453

Tovote, K. A., Fleer, J., Snippe, E., Peeters, A. C., Emmelkamp, P. M., Sanderman, R., … Schroevers, M. J. (2014). Individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for treating depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 37(9), 2427–2434. doi:10.2337/dc13-2918

Zettle, R. D., & Rains, J. C. (1989). Group cognitive and contextual therapies in treatment of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 436–445. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198905)45:3<436::AID-JCLP2270450314>3.0.CO;2-L