Abstract

Objective: We tested qualitative metasynthesis of a series of Hermeneutic Single Case Efficacy Design (HSCED) studies as a method for comparing within-session processes that may explain good and poor therapeutic outcome. Method: We selected eight HSCED studies according to change in clients’ scores on the Strathclyde Inventory (SI), a brief self-report instrument used to measure outcome in person-centered psychotherapy. Four of the case studies investigated the experience of clients whose pre–post change in SI scores showed improvement by the end of therapy, and the other four focused on clients whose change in SI scores indicated deterioration. We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis, adopting a generic descriptive-interpretive approach to analyze and compare the data generated by the HSCED studies. Results: In contrast to improvers, deteriorators appeared to be less ready to engage in therapeutic work at the beginning of therapy, and found the process more difficult; their therapists were less able to respond to these difficulties in a responsive, empathic manner; deteriorators were less able to cope successfully with changes of therapist and, eventually, gave up on therapy. Conclusion: We found that our qualitative metasynthesis of a series of HSCED studies produced a plausible explanation for the contrasting outcomes that occurred.

Clinical or Methodological Significance of this Article: This is the first study in which a qualitative metasynthesis of a series of Hermeneutic Single Case Efficacy Design studies has been used to compare within-session processes in good and poor outcome cases. We propose this method as a contribution to process-outcome research.

Traditionally, outcome in psychotherapy has been assessed by analyzing quantitative data collected using self-report instruments; however, there is a growing challenge to this position (e.g., Truijens et al., Citation2019). As Elliott (Citation2002) has argued, the “gold standard” of the quantitative paradigm, the randomized controlled trial design, is problematic for several reasons, most notably its causal emptiness; that although pre–post difference in quantitative scores may indicate that a particular outcome has occurred, it does not provide evidence about the change process that has taken place. More recently, Truijens (Citation2017) used an empirical case study to demonstrate that the procedural objectivity assumed in quantitative outcome measurement can be challenged when compared with alternative sources of data, for example the client’s own narrative about their experience during their therapy, highlighting specific problems associated with relying on one source of evidence (in this case, the numbers) to tell the client”s story.

Elliott (Citation2010) proposed systematic methodological pluralism as a way forward. He identified four promising lines of evidence within the change process research paradigm. One of these, qualitative helpful factors design, typically involves asking the client what they have found helpful in the therapeutic process, either during therapy (e.g., using a post-session questionnaire such as the Helpful Aspects of Therapy (HAT) form (Llewelyn, Citation1988) or by interviewing them, often at the end of therapy (e.g., the Change Interview; Elliott et al., Citation2001). Timulak”s (Citation2007) qualitative meta-analysis of client-reported helpful experiences in therapy identified nine core categories: awareness/ insight/ self-understanding; behavioral change/ problem solution; empowerment; relief; exploring feelings/ emotional experiencing; feeling understood; client involvement; reassurance/ support/ safety; and personal contact. Castonguay et al. (Citation2010) identified that both clients and therapists reported increasing client self-awareness as a particularly helpful therapeutic event. Although less conclusive, Castonguay et al. noted that the hindering event rated most often by clients was “poor fit”, and by therapists, “therapist omission”.

However, Elliott (Citation2010, p. 124) noted that process-outcome research is a more popular line of evidence within the change process paradigm as it is “intuitively appealing”: within-session therapy processes are assessed and related to post-therapy outcomes. Although generally quantitative in nature, the known groups design, in which clients are identified according to outcome and their experiences in therapy compared, is an approach to process-outcome research that allows for a more flexible approach to data collection. This enables process-outcome research to incorporate case study and qualitative research designs for investigating the specific helpful and hindering processes that may influence different outcomes in therapy. For example, Strupp (e.g., Citation1980) paired case studies of clients with contrasting outcomes who had worked with the same therapist. His findings provided evidence that the client’s readiness for therapy, their match with the therapy offered, and the therapist’s ability to adapt to the individual client, were key variables that could credibly explain the different outcomes achieved. McElvaney and Timulak (Citation2013) interviewed good outcome and poor outcome clients after the end of therapy. Although they found that both groups of clients reported broadly similar experiences in therapy, they noted that, more often, good outcome clients reported valuing therapist equality (e.g., someone who could relate to what they were sharing) than poor outcome clients, who preferred therapist guidance (e.g., someone who pointed out something of which they were unaware). More recently, Werbart et al. (Citation2019a) identified differences between successful and non-improved cases based on the development (or not) of agreement between client and therapist about the focus and goals of therapy, and the therapists’ ability to work with their clients through difficulties that arose in the therapeutic relationship.

The Hermeneutic Single Case Efficacy Design (HSCED; Elliott, Citation2002) is an example of systematic methodological pluralism in which outcome, efficacy, and change process research is integrated within a systematic single case study design. HSCED was introduced as a practical reasoning system not unlike those used in other professions such as law and medicine. Adopting a structured, critical-reflective approach, the researcher investigates three questions: (1) did the client change? (outcome research); (2) was the therapy generally responsible for the change? (efficacy research); and, (3) what specific factors within or outside therapy were responsible for the change? (change process research). HSCED is hermeneutic because it seeks to interpret a rich - and often contradictory - range of quantitative and qualitative data collected from various sources (e.g., client and therapist), interrogate complexities in the data, and draw inferences that can lead to a plausible understanding of an individual client’s therapeutic outcome, and the processes that brought it about. Data are collated in a rich case record, then analyzed. The researcher (or team of researchers; Elliott et al., Citation2009) interrogates the evidence from two opposing positions: first, the affirmative case, which seeks to demonstrate that change took place and was causally influenced by the therapy; and second, the skeptic case, which attempts to challenge the affirmative case and present alternative explanations for apparent client change. Finally, an independent adjudication panel evaluates the plausibility of each position. Most published HSCED cases have primarily focused on HSCED as a method for evaluating outcome: e.g., good outcome cases (e.g., MacLeod & Elliott, Citation2014), mixed outcome cases (e.g., Stephen et al., Citation2011), and poor outcome cases (e.g., MacLeod & Elliott, Citation2012). However, little work has been done to synthesize the findings of a series of HSCED studies: to build knowledge about the relationship between outcome and change processes that the HSCED method offers.

Iwakabe and Gazzola (Citation2009) proposed metasynthesis as one of three potential methods for aggregating several case studies, and thereby strengthening the potential impact of knowledge generated by this research method. Most multiple case study research following Iwakabe and Gazzola’s proposals has used either structured case comparison methods, for example, the multiple case study observational qualitative design combined with a theoretically-derived case conceptualization model (e.g., O’Brien et al., Citation2019) or metasynthesis as the final stage of a mixed methods approach to case comparison (e.g., Van Nieuwenhove & Meganck, Citation2020). Iwakabe and Gazzola described the main goals of metasynthesis as theory building and development, and the systematic identification of shared concepts and themes. Ma et al. (Citation2015) evaluated the utility of metasynthesis in qualitative research. They identified the potential for new insights and interpretations of the data that were not available to the original researchers: for example, by reducing the bias of small studies, identifying consistencies and variations across studies, and recognizing the role of contextual factors (e.g., gender, culture) in individual studies. However, they also highlighted concerns, noting that the purpose of metasynthesis violated basic principles in qualitative research (e.g., not generalizing, reducing differences, seeking the experience of the majority), and that it was not yet established if the findings of metasyntheses were useful for informing clinical practice. Nevertheless, Ma et al. argued that a rigorous approach to metasynthesis can produce reliable and generalizable findings that create a qualitative evidence base that is comparable to those produced using quantitative methods.

Aim of This Study

We wanted to find out if a metasynthesis of a series of HSCED studies would enable us to identify helpful and hindering processes within therapy that may explain the different outcomes of two known groups, which we refer to as “improvers” and “deteriorators”. At the time we were conducting a validity study of the Strathclyde Inventory (SI; Stephen & Elliott, Citationin review), a brief self-report instrument designed to assess therapy outcome. Therefore, it made sense to us to connect these two studies by identifying improvers and deteriorators according to their pre–post SI data. Our metasynthesis was guided by the research question: what helpful and hindering within-session processes might explain outcome?

Method

The study was conducted using archived data collected from clients and therapists who had participated in person-centered therapy (PCT; Mearns et al., Citation2013) at a UK-based university psychotherapy research clinic since it was established in 2007. Eight new case studies (not previously studied) were conducted using the HSCED method.

Participants

All participants (clients and therapists) were volunteers at the research clinic. They consented at the time of their involvement with the research clinic for their data to be analyzed in a range of ways consistent with its use in this study.

Clients

The eight clients (four improvers and four deteriorators) were selected from the research clinic archive according to pre–post change in scores collected using the Strathclyde Inventory (SI; Stephen & Elliott, Citationin review; see below). We identified two groups of clients within the archive whose pre–post SI scores demonstrated reliable change (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991) on the instrument: either “reliable improvement” or “reliable deterioration”. We used a reliable change index (RCI) of p < .20 (equivalent to an 80% chance that the difference in score was not caused by measurement error) in order to maximize the available dataset. Nevertheless, the sample of deteriorators (N = 7) was substantially smaller than improvers (N = 105). Three deteriorators were excluded as they had not consented to their data being used for a project of this kind. We included all four of the remaining deteriorators in the study, and then sought to select a group of four improvers that balanced the group of deteriorators in terms of gender, age, and duration of therapy, and represented the greatest degree of improvement according to their SI scores. As we discovered that all four deteriorators had experienced at least one change of therapist during their therapy, we ensured that two of the improvers selected had also worked with more than one therapist.

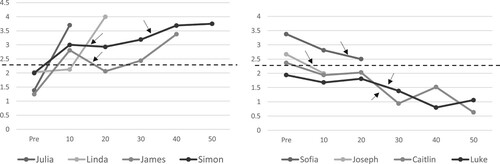

The final combination of clients appeared relatively well balanced, with each group including two males and two females and representing a range in therapy duration: the mean number of sessions for improvers was 29.25 (range = 9 - 47), and for deteriorators was 35.5 (range = 16 - 55). presents an overview of the eight clients, using pseudonyms selected by their HSCED researcher, with basic demographic data (gender, age, ethnicity), descriptive data (number of sessions, period at which they attended the research clinic, categories of self-identified presenting problems), and outcome data. (A) (improvers) and (B) (deteriorators) are line graphs that illustrate the change in mean SI scores at each data collection timepoint for each client over the course of therapy. These figures clearly depict the contrasting direction of change indicated by the SI scores collected from the clients in each group. Arrows have been added to indicate when a change in therapist occurred.

Figure 1. (A) Improvers (B) Deteriorators. Line graphs of mean SI scores for four ‘improver’ clients (A) and four ‘deteriorator’ clients (B) at each data collection timepoint over the course of therapy. Notes. Timepoints: pre = at intake; 10 = after 10 therapy sessions; 20 = after 20 therapy sessions; 30 = after 30 therapy sessions; 40 = after 40 therapy sessions; 50 = after 50 therapy sessions. Dashed line = 2.36 (clinical cut-off score; Stephen & Elliott, Citationin review). Arrows = first session with new therapist: James = session 16; Simon = sessions 15 and 33; Joseph = session 8; Sofia = session 16; Caitlin = session 26; Luke = session 28.

Table I. Overview of HSCED clients’ data.

Therapists

Fourteen volunteer therapists worked with these clients. The majority of therapists were female (n = 12) and had a mean age of 37.6 years (range: 23–58 years). There was little ethnic diversity among the volunteers: Middle Eastern (n = 1); White-Non-European (n = 1); and White-British (n = 12). Most therapists were in training at the time, either as person-centered counselors (enrolled in a one-year full-time or two-year part-time postgraduate diploma program) or as counseling psychologists learning person-centered therapy in the first or second years of their three-year professional doctorate program. In we have identified the therapists involved in this study according to their stage of training at the time they began working with their client (i.e., in the first or second half of their training period, or post-training). Three therapists were post-training at the time that they commenced the therapy: one was recently qualified (T3, Simon), another was two years’ post-qualification (Julia), and the third was six years’ post-qualification (T2, Sofia). This third therapist had also worked with one other client in the sample when in training (Linda).

Researchers

The ten co-authors of this paper formed a research team for the purpose of this study. The first author, an experienced person-centered therapist employed as a researcher by the university, designed the study, supervised the HSCED studies, and conducted the metasynthesis reported here. The tenth author, who was Principal Investigator of the research clinic and an experienced HSCED researcher, supervised the first author and audited the metasynthesis. The remaining eight authors, the “HSCED researchers”, were postgraduate students in training as person-centered therapists, who responded to an invitation from the first author to conduct the HSCED studies as credited coursework.

Both staff members held clinical governance and supervisory responsibilities within the research clinic. The first author was able to recall varied degrees of detail about the therapeutic processes of some of the clients selected for the study and had supervised some of the therapists involved. As a result, she was aware of assumptions she held about some clients’ experiences in therapy and potential reasons for their outcome, and used supervision to monitor these assumptions not only when working with the HSCED researchers, so that their interpretations of the data was not unduly influenced by her experience of the clients or therapists, but also when conducting the metasynthesis. Two other authors were in placement at the research clinic at the time of the study, but not when the eight clients were participating in their therapy.

All ten authors were aligned with PCT as trainers or trainees in the approach at the time we conducted the study. We were aware of our hope to find evidence that the therapy had been effective (and not harmful to those clients whose SI scores indicated deterioration). Before beginning the HSCED studies, we reflected on our existing assumptions in relation to the authority of quantitative versus qualitative data and what “substantial change” (whether improvement or deterioration) might look like, intending that this process would prepare us to approach the data with openness, curiosity and more explicit awareness of our biases.

Data Collection Instruments

The SI is a brief self-report instrument with a five-category Likert-style rating scale (range = 0–4; higher scores indicate greater functioning) designed to measure Rogers’ concept of the “fully functioning person”: “the end-point of optimal psychotherapy … the kind of person who would emerge if therapy was maximal” (Rogers, Citation1963, p. 18). Assessing a French-language version of the SI, Zech et al. (Citation2018) identified very good inter-item consistency (Cronbach alpha = .88), and evidence of convergent and discriminant validity consistent with predictions: a high positive correlation with emotional intelligence; moderate positive correlations with extraversion and agreeableness; moderate negative correlations with indicators of alexithymia and neuroticism (in students), along with symptoms of anxiety and depression (in patients). Data has been collected on the English-language version of the SI in the research clinic since 2007. Stephen & Elliott (Citationin review) evaluated the SI as unidimensional (i.e., good fit to the Rasch model) with 60.7% variance explained by the measure, and demonstrating temporal consistency at pre-therapy (r = .81) and sensitivity to change over the course of therapy (Cohen’s d = .93). Measurement gaps and item redundancy have been addressed to produce the current 12-item version (Stephen & Elliott, Citationin review). The SI is intended for use as an outcome instrument (with data collected in the research clinic at pre-therapy, at regular intervals during therapy and at the end of therapy). Stephen and Elliott (Citationin review) calculated a clinical significance cut-off score of 2.36, and minimum RCI values of .97 (p < .05) and .64 (p < .20).

Two further instruments were used to capture quantitative outcome data. The CORE-OM (Barkham et al., Citation2015) is a 34-item self-report instrument with a five-category Likert-type scale measuring general distress experienced in the past seven days. Barkham et al. recommended a clinical significance cut-off score of 1.0 and approximate RCI minimum value of .5 (p < .05). The Personal Questionnaire (PQ; Elliott et al., Citation2016) is a client-generated outcome measure created by the client at the intake interview to track change in specific difficulties. Elliott et al. recommended a clinical significance cut-off score of 3.25 and RCI minimum value of 1.5 (p < .05). In , pre- and post-therapy scores within the non-clinical range for each instrument are highlighted in bold. Post-therapy scores that indicate clinically significant change (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991) are identified with an asterisk. According to the clients’ PQ items, all but one client (Simon) identified difficulties involving sense of self, and relationships with others (interpersonal). Five clients (Julia, James, Simon, Sofia, and Caitlin) included PQ items relating to difficulties with life functioning. Two clients (James and Caitlin) added items that indicated difficulties with depression.

The Working Alliance Inventory—Revised Short version (WAI-SR; Hatcher & Gillaspy, Citation2006) is a 12-item self-report instrument completed by the client that seeks to measure the emotional bond between client and therapist as well as agreement on the goals and tasks of therapy. This was the main instrument used to assess the therapeutic relationship. The clients completed the WAI-SR at the end of sessions 3, 5, and then every fifth session until the end of therapy. In we have presented the mean WAI-SR scores for each client-therapist dyad. The maximum possible mean score on the WAI-SR is 5, and the minimum possible mean score is 1. As indicates, the median and range of WAI-SR scores for dyads within the improver group (median = 4.32; range = 3.10–5.00) is higher than that for dyads in the deteriorator group (median = 2.83; range = 1.43–4.50). Unfortunately, WAI-SR data was missing for Sofia and her second therapist.

The clients completed a Helpful Aspects of Therapy form (HAT; Llewelyn, Citation1988) at the end of each counseling session, in which they were invited to write brief qualitative descriptions of specific experiences within the session that they found helpful or hindering. After every tenth session of counseling and at the end of therapy, the clients met with a researcher (who was not their therapist) to complete the quantitative outcome instruments and participate in a semi-structured Change Interview (Elliott et al., Citation2001) designed to capture the client’s description of their experience of counseling so far, including changes they had noticed in themselves, their understanding about what had caused these changes, personal strengths and limitations that positively or negatively affected their ability to use therapy, specific and general examples of helpful and hindering experiences in therapy as well as the impact of the research protocol. Unfortunately, due to a technical issue, we were unable to access audio recordings of the Change Interviews of three deteriorators (Sofia, Luke and Caitlin). However, brief notes of these interviews had been made by their researchers, including a list of the changes that they had reported on each occasion, along with their ratings of how much they were surprised or expected these changes, how likely they thought these changes would have occurred without therapy, and how important these changes were to them. Copies of the HAT form and Change Interview can be accessed in the online supplementary material.

The clients’ therapists contributed qualitative process data about the therapy by completing a post-session form at the end of each counseling session in which they recorded process notes, including their perception of the main events in the session, and any unusual within-therapy or extra-therapeutic events.

Data Analysis

Due to space constraints, a description of the process followed by the HSCED researchers in preparing and conducting the HSCED studies is provided as online supplemental material. For a systematic review of HSCED research, including methodological options and issues, see Benelli et al. (Citation2015).

Metasynthesis

Once the eight HSCED studies had been completed, the first author commenced the metasynthesis using as data the material generated by the HSCED researchers: the affirmative and skeptic cases, and the narrative decisions produced by the adjudication panels. Our rationale for this design was that the HSCED researchers had already examined the raw data collected from the client and therapist, identifying and assessing the data for evidence of features in the therapeutic process that may have contributed to the client’s outcome. Their examination of the evidence was further evaluated and interpreted by the adjudication panel, who summarized the most plausible explanations from their perspective. Therefore, the data to be analyzed within the metasynthesis had already been through two layers of interpretation. This was an advantage in that it provided a condensed representation of each case study, but also presented the possibility that there may have been some differences in the way that the first author would have used the data available for inclusion in the rich case records.

Adopting a generic descriptive-interpretive approach to qualitative analysis (Elliott & Timulak, Citation2020), the first author entered into a “dialog with the data” (p.16), alternating between improver and deteriorator cases, and extracting meaning units from the HSCED material guided by the question: what helpful and hindering within-session processes might explain outcome? Meaning units were identified in arguments proposed or qualitative data cited (e.g., quotes from the client or therapist extracted from HAT forms, change interviews, or therapist session forms) by the HSCED researchers in their affirmative and skeptic cases, and in the adjudicator panels’ written feedback explaining the reasons for their decisions on the outcome of the case.

Influenced by McElvaney and Timulak’s finding (Citation2013) that good and poor outcome clients tended to report broadly similar experiences, the first author aimed to produce one analytic framework in which the therapeutic experiences of all clients, irrespective of outcome, could be accommodated, and then differences detected. First, she carried out a pragmatic and preliminary sorting process, bringing together similar meaning units into broad general domains (client, therapeutic relationship, therapist, nature of ending), then continued the analysis by seeking clusters of meaning units that represented more nuanced themes, and relationships between themes. This flowing process of constant comparison (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008) within a conceptual framework (Elliott & Timulak, Citation2020) resulted in the creation of a hierarchy of categories and sub-categories that represented a coherent model of the main features of the therapeutic process identified within the material produced by the eight HSCED studies.

As suggested by Elliott and Timulak (Citation2020), the final step was to count the frequency that the two groups, improvers and deteriorators, were represented within each category and sub-category in the model developed during the metasynthesis. This process enabled the characterization of categories within the therapeutic experience that were general for each group (i.e., the category or sub-category contained meaning units representing all four case studies), typical (three of the four case studies were represented), variant (two of four), or unique (one of four). Features identified as general or typical for either group were viewed as defining features, indicated by this synthesis of the group’s therapeutic experience. Following Hill et al. (Citation2005), we identified differences between the groups when results for the two groups in a category or sub-category diverged by at least two frequency levels (e.g., improvers—general; deteriorators—variant).

Results

The results of our metasynthesis are presented in six domains: readiness to begin therapy; therapeutic climate; therapist in the process; client in the process; challenges in the process; and ending of therapy. Due to limits of space, we present the defining (i.e., general or typical) features that we identified, and highlight the differences that these indicate between the two groups. provides an overview of our findings. Due to the multiple sources of data brought together by the HSCED method, our metasynthesis is not only an assimilation of a series of cases but also of multiple perspectives (i.e., clients, therapists, HSCED researchers and adjudicators) within each case study. Where we have illustrated our presentation of our findings with example meaning units, we have identified their source (e.g., the client, therapist, HSCED researcher or adjudication panel) and the part of the HSCED material (e.g., affirmative brief, skeptic rebuttal, adjudication) in which it was found.

Table II. Comparison of general and typical features in the therapeutic process of improvers and deteriorators.

Readiness to Begin Therapy

In general, improvers appeared ready to begin therapy, being motivated (general), including having determination (typical); being open to the experience (general), typically able to be reflective; and prepared (typical). Linda’s HSCED researcher reported that she “repeatedly indicated an expectation and a personal determination to change [showing] that she had significant expectations from the therapeutic process, and a strong sense of personal agency in making changes” (Skeptic Brief). Deteriorators were also identified as motivated (typical): for example, their adjudication panels acknowledged Luke’s “determination” and Caitlin’s “stubbornness” as being strengths that they brought to therapy. However, none of the deteriorators appeared to begin therapy with the same “web of readiness” as improvers at this stage of the process.

We found that it was typical in both groups for clients to begin therapy with various potential challenges to readiness for the process. Although there was no consistency in the nature of these challenges amongst improvers, it appeared to be typical for deteriorators to enter therapy with doubt / potential for doubt. These doubts (or potential for doubt) were experienced in several ways. For example, Caitlin’s HSCED researcher noted her “expectation of increased feelings of vulnerability because of attending counselling” (Affirmative Brief), whereas Joseph, at his change interview, reflected that “maybe I had the wrong expectations but it was, from the beginning, pretty clear that it’s me doing all the talking. Sometimes it feels like, you kinda want that advice or that constructive feedback, a bit more honest” (Skeptic Brief).

Therapeutic Climate

All improvers and deteriorators described the therapeutic climate, a reflection of the nature of the therapeutic relationship, as safe (typical), supportive (typical), and containing warmth and connection (typical), that is, the kind of therapeutic climate in which facilitative therapist and client processes are predicted to occur in therapy (Rogers, Citation1957/Citation1992; Lambert, Citation2013). For example, during their change interviews, Linda told her researcher “And then there came a point when I thought, no, maybe there [are] issues that I really need to bring up, release, and let go in this safe environment. And really deal with things” (Affirmative Brief), while Caitlin commented “It was a safe space so I could be me, exactly me, and not an act” (Skeptic Brief).

Therapist in Process

We found evidence that all therapists (or at least one therapist in each case) were described, or described themselves, as behaving toward their clients in ways that we characterized as facilitative therapist processes; in particular, working within the client’s frame of reference. Therapists in both groups (improvers, general; deteriorators, typical) demonstrated this by accepting/ understanding their client. For example, Linda’s therapist wrote in her post-session form:

I reflected [to the client] that there was one tree (according to client’s image) that still needs to be knocked down, and added that I don’t want to push the client to do that and hope I haven’t today (Affirmative Brief).

Therapists working with deteriorators also worked within their client’s frame of reference by validating and affirming their experience (typical). Interestingly, this was the only facilitative therapist process identified that differed by at least two frequency counts between the two groups. Deteriorators described feeling reassured by the affirmation in their therapist’s responses to them, which confirmed that their experiences could be taken seriously. For example, Joseph told his researcher that, when he noticed that his therapist was visibly moved by what he was telling her, “it validated […] what I was saying out loud, that it mattered and it was upsetting” (Skeptic Brief).

In addition to working within their client’s frame of reference, therapists who worked with the improvers could be described as offering opportunities (typical) and being transparent (typical). Offered opportunities could be as simple as inviting the client to ground themselves or slow down - for example, Simon’s therapist wrote that she suggested to him that “if he wanted, we could slow things down a bit” (Affirmative Rebuttal); or by noting an opportunity to develop the therapeutic process and offering this to the client—such as when Linda’s therapist identified an “opportunity to allow the inner child back in” (Affirmative Brief). There were a variety of ways in which improvers experienced their therapists as transparent, such as responding to client’s questions, and discussing the therapeutic process with them. Simon described asking his therapist how she thought he was doing as helpful because sometimes it was hard for him to feel positive. He commented that “it helped to hear what the therapist had to say” (Affirmative Brief). There were also unique and variant examples that described therapists working with deteriorators transparently and offering opportunities but not with sufficient frequency to identify either feature as typical for that group’s experiences.

We found evidence of interfering therapist processes within the deteriorator case studies. This was characterized by descriptions in which it seemed as if therapists were not working in the client’s frame of reference (typical), for example, by directing content, attempting to accelerate process, and losing patience with their clients. Indeed, Joseph described his counselor as wanting to “delve” into details about his family, and told his researcher: “that’s not what’s upsetting me, that’s not why I’m here” (Affirmative Rebuttal). Meanwhile, Luke’s HSCED researcher noted:

On multiple occasions, Luke’s therapists wrote about creating silence in the session as an “opportunity” for Luke to engage. Luke himself did not feel like this was the therapist kindly offering him a chance to engage—he viewed it as an abandonment and a lack of caring. The second therapist wrote: “He said it was not an opportunity. He said I wasn’t interested.” Luke described the silence as hindering on a couple of occasions. (Affirmative Brief)

These examples suggested to us that these therapists had struggled, more so than those working with the improvers, to maintain the conditions considered to be necessary for therapeutic change to occur (Rogers, Citation1957/Citation1992) when working with their clients. We found some indications of why this may have been when we turned to consider the client in the therapeutic process.

Client in Process

We noted features that could be described as facilitative client processes occurring for both groups of clients. There was clear evidence of client commitment present in both groups, in particular engagement in the therapeutic process (general for improvers; typical for deteriorators). For example, both Julia and James’ HSCED researchers argued in their affirmative briefs that the quantitative and qualitative data in their rich case records demonstrated that they were “fully engaged” from the beginning of therapy. Luke’s adjudication panel was able to point to “his consistent attendance, his requests for appointment changes, [instead of] cancellations” (Adjudication) as evidence of his engagement in therapy. However, in terms of commitment to the process, there were two clear differences between improvers and deteriorators. One was the apparent ability of the improvers to integrate therapy and life (general). The data showed them using therapy to connect with/ work on life problems (general): for example, Julia described to her researcher that “talking about getting off my anti-depressants had me feeling really anxious about it in the session, but then we turned it around and I was reminded that I do know how to ground myself in an anxious situation” (Affirmative Brief). In addition, there was evidence of all four improvers working hard in and out of the therapy room. For Julia, it was clear that the improvement she experienced by the end of therapy “came from really hard work in here, but also really hard work outside of the therapy room” (Affirmative Rebuttal).

We found more detailed descriptions in the improver HSCEDs about the client’s facilitative processes in therapy. Improvers described experiencing their feelings (i.e., opening up and allowing self-awareness; general), and in particular realizing their feelings (typical). This process occurred alongside the improvers working through complex situations by exploring, sorting thoughts more clearly, and making connections / understanding why things happened (typical). For example, in his post-session HAT form, James wrote:

Starting to deal with the feelings of shame and guilt is the deepest most important breakthrough in the therapy so far. The realization and new understanding of these issues allows me to find ways of finally tackling/dealing with the problem. (Affirmative Brief)

In contrast, deteriorators described interfering client processes that improvers did not report. All deteriorators experienced discomfort in the process, in particular difficulty opening up (general). For some, opening up was difficult and painful (typical), as Caitlin discovered when she spoke about experiences from her childhood (Affirmative Brief). Others may have experienced a pressure to engage (typical) before they were ready, an argument made by both Sofia and Luke’s HSCED researchers in their affirmative cases. A second type of discomfort in the therapeutic process for deteriorators was struggling to find direction (typical). For example, Joseph’s HSCED researcher noted that he had found the lack of direction from his therapists difficult (Skeptic Brief), while Luke’s HSCED researcher explained that the reason he “frequently brought no content into his sessions […] was due to the fact that he struggled knowing what to say” (Skeptic Rebuttal).

Some HSCED researchers used the rich case record to argue that deteriorators may have developed a deference toward their therapist (typical), which could have prevented them from getting what they needed from the therapeutic process. For example, in Sofia’s case, quantitative data collected using the Therapeutic Relationship Scale indicated that, as time went on, Sofia perceived her first therapist as sometimes taking the lead in sessions and saw herself as less able to disagree with or correct her (Affirmative Rebuttal).

Finally - and in contrast to the apparent ability of improvers in this area - there was evidence of some deteriorators struggling to integrate therapy and life (typical). Indeed, Caitlin recognized this at her first change interview, when she reported that she was struggling to apply what she learned in therapy “outside the counselling room” (Skeptic Brief).

Challenges in the Process

We identified that deteriorators seemed to experience more challenges in the therapeutic process than improvers. One of these challenges was change of therapist, an event that was experienced by all deteriorators and two improvers (Simon and James). From our perspective, changing therapist appeared to have an interfering effect (general) on deteriorators, especially when it happened with unfortunate timing for the client (typical). For example, Sofia’s HSCED researcher noted that her change of therapist occurred at “a time when Sofia was under a lot of pressure to make a very important decision about her future” (Affirmative Brief); while Caitlin reported that she was undergoing frequent changes to her medication at the time her therapist changed, and told her researcher that she was feeling overwhelmed by depression and under-supported during this period (Affirmative Rebuttal).

Nevertheless, a variety of non-interfering effects of the change were identified for both groups. Improvers presented these effects with more consistency, describing their positive perceptions of the change, and, significantly, seeing the change as an opportunity to gauge if they were handling it well. Two improvers noted in retrospect that the change had no impact on their overall process. Indeed, James reported later that he had found therapy helpful with both of his therapists (Affirmative Brief), and Simon concluded:

You kinda get to a point where you're spending an hour a week in a room with someone doing absolutely amazing stuff so all you can say realistically for me is that there may be some positive attachment not to the person but with the process. (Affirmative Brief)

Lastly, we found evidence suggesting that the therapeutic processes of deteriorators was affected by delay / inconsistency in the process (typical). Joseph told his researcher: “And then, when that thing happened with my personal situation, I really needed it but it wasn’t available […] I sort of found it annoying” (Affirmative Brief). Meanwhile, Caitlin struggled when her therapist rescheduled her appointments, and told her: “I would prefer if my counselling is more stable though, as my anxiety goes through the roof when I'm unsure about things” (Affirmative Brief).

Ending of Therapy

As clients were designated as improvers and deteriorators according to the change in their SI scores at the end of therapy, we felt it was important to look at the context in which this ending took place. Here, we identified distinct differences between the two groups.

Our metasynthesis suggested that only improvers experienced facilitative aspects of ending (general): they felt ready to end (general), they believed that the sessions helped a lot (general) - that they had made great progress (typical) - and there was a mutual decision to end (typical). Following their final therapy appointments, Julia wrote: “Letting go of sessions is scary but being able to, feels like great progress” (Affirmative Brief) and Linda noted: “Today was the end of our sessions—I feel it is time—I feel whole and ready to embrace life” (Affirmative Brief)

In stark contrast, only deteriorators reported interfering aspects of ending (general). The data collected consistently supported the view that deteriorators experienced an incomplete therapeutic process (general). Sofia’s HSCED researcher reported:

At the time that therapy ended, Sofia was not in a good place […] She had not fully worked through some very important personal issues. In fact, therapy had brought up a lot for her, particularly in relation to her experience of life in the UK. She had not identified what it was that she felt she was missing in the UK compared to life back home. It seems like Sofia ended her time in therapy too soon. (Affirmative Narrative)

Endings for deteriorators appeared to occur due to the client’s decision not to continue following therapist’s decision to leave or take an extended break (typical). Caitlin’s therapist recorded that when she informed her client that she was leaving the research clinic, Caitlin “seemed slightly disappointed about having to change counsellor in the new year” (Affirmative Brief), while Joseph’s HSCED researcher highlighted that Joseph left therapy at the point at which he would have been allocated another therapist “suggesting that he felt a further change of therapist was not helpful to him” (Affirmative Brief).

In general, deteriorators appeared to have experienced disappointment with the process by the end of therapy. This disappointment was founded on feeling worse (general), specifically more depressed / distressed (general) and more vulnerable (typical). Luke’s HSCED researcher noted that he had reported feeling “more guilty about self” as a result of therapy (Affirmative Brief) and that he seemed “very emotionally shut down and defeated even towards the end of therapy” (Skeptic Rebuttal).

Finally, we found evidence that all deteriorators were affected by a loss of hope in therapy, reinforced by a growing sense that there would be no resolution (typical). Joseph’s HSCED researcher argued that the fact he did not attend for an end of therapy change interview indicated that he felt therapy had not been helpful to him (Affirmative Brief). Meanwhile, Caitlin’s HSCED researcher concluded that: “the nature of Caitlin’s ending suggests that she was not ready for the intensity of her emotions if she were to allow things to ‘come to a head’ without the comfort of feeling like there could be a resolution” (Affirmative Brief).

Summary: Differences in the Processes of Improvers and Deteriorators

Compared to deteriorators, improvers began therapy feeling open to the experience and prepared. Their therapists were transparent and offered opportunities that enabled them to connect with themselves during the process. Improvers were able to experience their feelings, open up and allow self-awareness to develop, realize what they were feeling, clarify their thoughts, and make connections that enabled them to make sense of their experiences. They were able to integrate therapy into their lives, using therapy to connect with and work on their problems in life, and working hard in and out of the therapy room. If a change in therapist occurred it had little impact; they perceived this change positively and handled it well. When the time came, they felt ready to end therapy and the decision to end was by mutual agreement with their therapist.

In contrast, deteriorators began therapy describing more difficulties in their relationships with self and others, and holding more doubt (or the potential for doubt) about therapy. They experienced discomfort in the therapeutic process: it was difficult and painful to open up; they struggled to find direction, and deferred to their therapist. They were unable to integrate the therapy into their lives. Their therapists sought to validate and affirm their experiences but struggled to work within the client’s frame of reference at times, behaving in a controlling or directive manner. Deteriorators experienced delay, inconsistency and changes in therapist, which occurred with unfortunate timing. Typically, their therapy ended when their therapists left or took an extended break. Although the deteriorators could have continued in therapy, they decided that they would not, more than likely because they were feeling disappointed, depressed, distressed and vulnerable, and had lost hope in the process.

Discussion

This study piloted a new method: the metasynthesis of a series of Hermeneutic Single Case Efficacy Design (HSCED) studies within a known groups process-outcome design. The metasynthesis enabled us to synthesize and compare the therapeutic processes of four improvers and four deteriorators, analyzed using the HSCED method, and identify defining features. Consistent with Timulak’s (Citation2007) taxonomy of helpful factors, improvers explored emotional experiences, gained self-awareness and self-understanding, and felt understood, involved and empowered. They felt ready to end therapy and did so in mutual agreement with their therapist. This was not the case for deteriorators.

We propose three key findings that may explain why our four deteriorators ended therapy without the outcome that they had sought. First, our improvers and deteriorators differed in their readiness to begin therapy. Deteriorators were motivated to begin therapy, but carried doubts about the process: for example, because they expected to feel vulnerable or had the “wrong” expectations of this form of therapy, such as receiving advice from their counselor. This fits with Constantino et al.’s (Citation2020) finding of a significant association between optimistic client expectations (i.e., beliefs) about therapy outcome and favorable outcome, and Swift et al.’s (Citation2018) report of a small but meaningful difference in outcomes in favor of clients given their preferred psychotherapy, compared to those whose preferences were not matched nor given a choice of treatment conditions. Furthermore, it may be that deteriorators’ doubts indicate that they entered therapy at an earlier stage of change than the improvers. Krebs et al. (Citation2018) found a medium effect when testing the association between stages of change (according to the transtheoretical model) and psychotherapy outcome, suggesting that the amount of progress that clients make during therapy is a function of their stage of change (e.g., contemplation, preparation, action) when they begin.

It appears that deteriorators’ “initial misgivings” (MacFarlane et al., Citation2015) were confirmed by the discomfort they experienced in the process of therapy: difficulty in opening up, the struggle to find direction, leading to deference toward their therapist, and an inability to integrate the therapy and their lives. McFarlane et al. found that many clients had difficulty in actively participating in early sessions because of concerns and misgivings that they held, in particular not knowing what to expect and what might be expected of them. As in our study, their participants reported struggling to engage in various ways, including difficulty talking, concern about the psychotherapist, apprehension due to the newness of the situation, and fear that accessing therapy said something negative about themselves.

It seems probable that in our study, the therapists did not respond sufficiently to their clients’ doubts (or potential doubts) and discomfort as therapy proceeded. When exploring therapists’ experiences when working with nonimproved young adults, Werbart et al. (Citation2019b) found that the therapists had underestimated their clients’ problems, convinced that they were on the “right track”, and attributed the limited progress to their client’s “lack of will to open up and try harder” (p.904). Although these therapists attempted to talk with their clients about what was happening, Werbert et al. concluded that they were unable to adapt their approach to address their clients’ core problems. Krebs et al. (Citation2018, p. 1977) warned against assuming that all clients enter therapy “in action”, noting that “people in precontemplation underestimate the pros of changing, overestimate the cons, feel defensive when pressured, and … have lower expectations of therapist acceptance, genuineness and trustworthiness”.

Second, we considered descriptions of therapist responses in their work with the deteriorators, noting the ways in which they appeared to differ from the therapists of improvers. On one hand, we found clear evidence of the therapists validating and affirming their client’s experience. However, we also recognized descriptions of therapists working outside their client’s frame of reference, including acting in a controlling or directive manner: unhelpful therapist behaviors also identified by Curran et al. (Citation2019). From the perspective of person-centered theory, this suggests to us that there were times when these therapists experienced doubt and frustration, inevitably limiting psychological contact, empathic understanding, unconditional positive regard, and congruence. In short, we propose these therapists struggled at times to maintain the conditions required for therapeutic change to occur (Rogers, Citation1957/Citation1992). Instead of “appropriate responsiveness” (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017), these therapists made decisions about the therapeutic process that were not empathically attuned to their clients’ needs. In these circumstances, it is no wonder that the clients and therapists struggled to work through their mutual doubts. Similar evidence of an incomplete therapeutic process in poor outcome cases was identified by Watson et al. (Citation2007) who noted that the therapists in their cases were aware that “things were not meshing with their clients” (p.201), but felt helpless and uncertain about how to address the relational and process difficulties that ultimately led to an unsatisfactory outcome for their clients.

Third, we recognized that the apparent difficulties for deteriorators may have been further exacerbated by the presence of disruption and delay in the process. Although two improvers also faced the challenge of changing therapist, they used the experience to assess their growth (i.e., how well they handled this change of therapist). In contrast, while some deteriorators were optimistic about the change and there was evidence that their new therapists may have been a better fit for them, the change typically occurred at an unfortunate time for them for a variety of reasons. It seems highly likely that this unsettling change (which required clients, who had come to therapy reporting difficulties in their relationships with others, to begin another new relationship), combined for some with an inconsistency in the frequency of sessions, would have added further discomfort, discouraging them from engaging more fully in the process. It is no wonder that, when faced with changing therapist again (or having an extended break), these clients made the decision to end therapy. Indeed, our findings support Constantino et al.’s (Citation2020) conclusion that clients are more likely to have less positive expectations if they have already experienced a poor quality therapeutic alliance, and be at increased risk of poor outcome following an alliance rupture.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The potential generalizability of our results is limited by the demographics of our client group and the context in which they accessed therapy: White-British/European adults participating in relatively long-term person-centered therapy at a UK-based university psychotherapy research clinic. We also acknowledge that our analysis and interpretation of data throughout this study was shaped by our assumptions as person-centered therapist-researchers. It is likely that other groups of researchers, working with different theoretical perspectives, would have identified different themes and made different assumptions based on the data produced by the series of HSCED studies.

Nevertheless, we were surprised at the clear similarities and differences that we identified between improvers and deteriorators. We believe that the apparent lack of exceptions and alternative explanations in our findings is reinforced by three related factors. First, we studied extreme cases: examples of clients whose SI scores indicated reliable improvement or reliable deterioration. We expect that further HSCED studies examining the experience of clients with “no change” on the SI would introduce greater nuance when integrated within a future update of this metasynthesis. Second, due to space limitations we focused on presenting our general and typical findings only. Third, there is no indication that our metasynthesis reached “saturation” (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Our study was limited by the small sample of deteriorator cases and the relative “thinness” of the available data. Finally, did we find what we expected to find? We were not blind to the client’s quantitative outcome data and therefore may have been influenced by this knowledge; however, it would have been impossible to apply the HSCED method, nor to have analyzed the HSCED materials as known groups within the metasynthesis, without this information.

Conclusion

In this study, a qualitative metasynthesis of a series of eight HSCED studies produced a plausible narrative of within-session processes that led to either improvement or deterioration by the end of therapy, reflecting the participants’ quantitative outcome scores. We found that the HSCED method allowed the rich range of quantitative and qualitative data collected in each case to be analyzed and evaluated, while the qualitative metasynthesis enabled the detailed findings generated in each HSCED study to be synthesized and compared within the series. We propose that the qualitative metasynthesis of a series of HSCED studies offers an approach to systematic methodological pluralism and known groups design that can make a contribution to process-outcome research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (81.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the clients and therapists of the Strathclyde Counselling & Psychotherapy Research Clinic who shared their experiences of the therapeutic process and made this study possible.

Disclosure Statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author to obtain access to the dataset associated with this study.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed doi:10.1080/10503307.2021.1934746.

References

- Barkham, M., Mellor-Clark, J., & Stiles, W. B. (2015). A CORE approach to progress monitoring and feedback: Enhancing evidence and improving practice. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000030

- Benelli, E., De Carlo, A., Biffi, D., & McLeod, J. (2015). Hermeneutic Single Case Efficacy Design: A systematic review of published research and current standards. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 22 (1), 97–133. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM22.1.7

- Castonguay, L. G., Boswell, J. F., Zack, S. E., Baker, S., Boutselis, M. A., Chiswick, N. R., Damer, D. D., Hemmelstein, N. A., Jackson, J. S., Morford, M., Ragusea, S. A., Roper, J. G., Spayd, C., Weiszer, T., Borkovec, T. D., & Holtforth, M. G. (2010). Helpful and hindering events in psychotherapy: A practice research network study. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(3), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021164

- Constantino, M. J., Coyne, A. E., Goodwin, B. J., Vîslă, A., Flückiger, C., Muir, H. J., & Gaines, A. N. (2021). Indirect effect of patient outcome expectation on improvement through alliance quality: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 31(6), 711–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1851058

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Curran, J., Parry, G. D., Hardy, G. E., Darling, J., Mason, A-M., & Chambers, E. (2019). How does therapy harm? A model of adverse process using task analysis in the meta-synthesis of service users’ experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, art.347, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00347

- Elliott, R. (2002). Hermeneutic single case efficacy design. Psychotherapy Research, 12(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/713869614

- Elliott, R. (2010). Psychotherapy change process research: Realizing the promise. Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300903470743

- Elliott, R., Partyka, R., Alperin, R., Dobrenski, R., Wagner, J., Messer, S., Watson, J. C., & Castonguay, L. J. (2009). An adjudicated hermeneutic single-case efficacy design study of experiential therapy for panic/phobia. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4-5), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300902905947

- Elliott, R., Slatick, E., & Urman, M. (2001). Qualitative change process research on psychotherapy: Alternative strategies. In J. Frommer, & D. L. Rennie (Eds.), Qualitative psychotherapy research: Methods and methodology (pp. 69 -111). Pabst Science Publishers.

- Elliott, R., & Timulak, L. (2020). Essentials of descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: A generic approach. American Psychological Association.

- Elliott, R., Wagner, J., Sales, C. M. D., Rodgers, B., Alves, P., & Café, M. J. (2016). Psychometrics of the Personal Questionnaire: A client-generated outcome measure. Psychological Assessment, 28(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000174

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gillaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500352500

- Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

- Iwakabe, S., & Gazzola, N. (2009). From single-case studies to practice-based knowledge: Aggregating and synthesizing case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4-5), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802688494

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

- Krebs, P., Norcross, J. C., Nicholson, J. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2018). Stages of change and psychotherapy outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1964–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22683

- Lambert, M J. 2013). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy & behavior change (pp. 169–218). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Llewelyn, S. (1988). Psychological therapy as viewed by clients and therapists. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1988.tb00779.x

- Ma, N., Roberts, R., Winefield, H., & Furber, G. (2015). Utility of qualitative metasynthesis: Advancing knowledge on the wellbeing and needs of siblings of children with mental health problems. Qualitative Psychology, 2(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000018

- MacFarlane, P., Anderson, T., & McClintock, A. S. (2015). The early formation of the working alliance from the client’s perspective: A qualitative study. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038733

- MacLeod, R., & Elliott, R. (2012). Emotion-focused therapy for social anxiety: A hermeneutic single-case efficacy design of a low-outcome case. Counselling Psychology Review, 27 (2), 7–21.

- MacLeod, R., & Elliott, R. (2014). Nondirective person-centered therapy for social anxiety: A hermeneutic single-case efficacy design study of a good outcome case. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 13(4), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2014.910133

- McElvaney, J., & Timulak, L. (2013). Clients’ experience of therapy and its outcomes in ‘good’ and ‘poor’ outcome psychological therapy in a primary care setting: An exploratory study. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 13(4), 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.761258

- Mearns, D., Thorne, B., & McLeod, J. (2013). Person-centred counselling in action. Sage.

- O’Brien, K., O’Keeffe, N., Cullen, H., Durcan, A., Timulak, L., & McElvaney, J. (2019). Emotion-focused perspective on generalized anxiety disorder: A qualitative analysis of clients’ in-session presentations. Psychotherapy Research, 29(4), 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1373206

- Rogers, C. R. (1957/1992). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(6), 827–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.60.6.827

- Rogers, C. R. (1963). The concept of the fully functioning person. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 1(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088567

- Stephen, S., & Elliott, R. (in review). The Strathclyde Inventory: Development of a brief instrument for assessing outcome in counseling according to Rogers’ concept of the fully functioning person. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development.

- Stephen, S., Elliott, R., & MacLeod, R. (2011). Person-centred therapy with a client experiencing social anxiety difficulties: A hermeneutic single case efficacy design. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.546203

- Stiles, W. B., & Horvath, A. O. (2017). Appropriate responsiveness as a contribution to therapist effects. In L. G. Castonguay, & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 71–84). American Psychological Association.

- Strupp, H. H. (1980). Success and failure in time-limited psychotherapy. A systematic comparison of two cases: Comparison 1. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37(5), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780180109014

- Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., Cooper, M., & Parkin, S. R. (2018). The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1924–1937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22680

- Timulak, L. (2007). Identifying core categories of client-identified impact of helpful events in psychotherapy: A qualitative meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600608116

- Truijens, F. L. (2017). Do the numbers speak for themselves? A critical analysis of procedural objectivity in psychotherapeutic efficacy research. Synthese, 194(12), 4721–4740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1188-8

- Truijens, F. L., Desmet, M., De Coster, E., Uyttenhove, H., Deeren, B., & Meganck, R. (2019). When quantitative measures become a qualitative storybook: A phenomenological case analysis of validity and performativity of questionnaire administration in psychotherapy research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1579287

- Van Nieuwenhove, K., & Meganck, R. (2020). Core interpersonal patterns in complex trauma and the process of change in psychodynamic therapy: A case comparison study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00122

- Watson, J., Goldman, R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2007). Case studies in emotion-focused therapy for depression. American Psychological Association.

- Werbart, A., Annevall, A., & Hillblom, J. (2019a). Successful and less successful psychotherapies compared: Three therapists and their six contrasting cases. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, art.816, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00816

- Werbart, A., von Below, C., Engqvist, K., & Lind, S. (2019b). “It was like having half of the patient in therapy”: therapists of nonimproved patients looking back on their work. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 894–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1453621

- Zech, E., Brison, C., Elliott, R., Rodgers, B., & Cornelius-White, J. H. D. (2018). Measuring Rogers’ conception of personality development: Validation of the Strathclyde inventory-French version. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 17(2), 160–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2018.1473788