Abstract

Objective

Despite its considerable potential, psychotherapy research has made limited use of small-scale experimental study designs to test intervention components. This study employs such a design to test the immediate effects on emotional experience of two approaches to changing negative thoughts, cognitive restructuring and fostering positive thinking. Cognitive restructuring draws on the strategies core to cognitive behavioral therapies. Fostering positive thinking has also received attention, though less so as a psychological intervention.

Method

We tested the benefits of these strategies over a brief interval by randomizing 230 participants to complete a worksheet introducing one of the two strategies. Participants reported their skills prior to exposure to these worksheets and affect was assessed immediately prior to and following use of worksheets.

Results

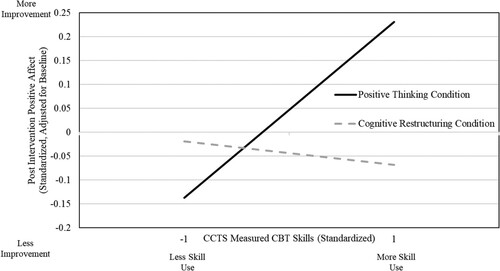

Participants’ negative affect reduced following both strategies. Conditions did not differ significantly in affect change. Analysis of potential moderators showed that, among those with higher levels of cognitive behavioral therapy skills, the positive thinking condition produced greater gains in positive affect than the cognitive restructuring condition.

Conclusions

These results indicate that both forms of brief interventions promote reductions in negative affect. Positive thinking interventions, which are not focused on the accuracy of one's thinking, appear to be particularly effective in promoting positive affect.

Keywords:

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: Little is known about the relative effects of therapeutic strategies intended to foster more accurate view versus more positive thinking. In an experimental comparison testing the immediate effects of these two approaches, there were not differences between strategies in their impact on positive or negative affect. However, those with greater cognitive behavioral therapy skills experienced greater positive affect improvements using positive thinking strategies.

Self-deception has often been portrayed as undesirable and deleterious to one's mental health (Makridakis & Moleskis, Citation2015; Maslow, Citation1950; Taylor & Brown, Citation1988). The goal of minimizing bias and inaccuracies in one's thinking is particularly central to conceptualizations underlying cognitive behavioral therapies (Hofmann & Asmundson, Citation2017). In various forms of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), reducing biases in one's views is a central therapeutic goal. Therapists make use of explicit strategies for helping clients to reevaluate their thinking, with goal being the development of less biased and more accurate views. As part of this process, therapists encourage the careful review of available evidence and the use of empirical testing of one's ideas (Beck, Citation1976 ; Beck et al., Citation1979).

There is a considerable body of evidence for overly positive thinking or positive illusions being characteristic of those in normative samples (Taylor & Brown, Citation1988). People generally regard themselves more positively (i.e., better) than others. Healthy individuals tend to judge themselves as better than average at driving, learning, teaching, memory, and work competency, among other things (Makridakis & Moleskis, Citation2015). These views are not limited to an elite subset of the population, nor are they accounted for by people's choosing to weigh the dimensions on which they are particularly gifted most strongly (Taylor & Brown, Citation1994). Viewing oneself in overly positive terms is associated with successful coping and positive outcomes. Positive thinking or optimism has been associated with positive outcomes as varied as physical health following recovery from surgery (Scheier et al., Citation1989), greater relationship satisfaction (Srivastava et al., Citation2006), and academic and job achievement (Buchanan et al., Citation1995).

These positive biases stand in stark contrast to the negative views observed among those with depression (Beck & Alford, Citation2009). Beck's early formulation of depression entailed a cognitive triad of negative views: unrealistically negative views of the self, world, and future. Although research evidence has shown that those with depression (or high levels of depressive symptoms) tend to have more negative views, whether those views are overly negative or just less positive has been the focus of some controversy (Ackerman & DeRubeis, Citation1991). Although those with high levels of depressive symptoms may be more accurate in some contexts, those with depression have more negative views and evidence for their greater accuracy appears to be limited to specific paradigms where more negative views are likely to coincide with greater accuracy (Carson et al., Citation2010). When researchers have focused on those with levels of depressive symptoms consistent with a clinical diagnosis and judgments that are emotionally engaging for participants, a more consistent pattern of overly negative views has been observed (Strunk & Adler, Citation2009).

Accuracy or Positive Thinking as a Therapeutic Target

The CBT strategies used to address cognitive vulnerabilities have been based on the conceptualization of the clinical problem being treated and an implicit goal of accuracy. In cognitive behavioral therapies, many intervention strategies are focused on correcting biases to develop more accurate views (Beck, Citation1976; Beck et al., Citation1979). Another approach is to counteract negative biases using positive thinking strategies, strategies that encourage clients to develop more positive views, even if such views are not tied to specific evidence. Though these strategies are less central to CBT, they are included in some treatment manuals (including Beck et al., Citation1979). For example, therapists might encourage clients to consider the adaptive value of their negative thoughts. However, CBT manuals have also taken care to distinguish CBT from simply promoting positive thinking (i.e., thinking more positively without regard for the accuracy of those thoughts; Beck et al., Citation1979).

Although a focus on accuracy has been more dominant in CBT, there is reason to consider strategies that focus on increasing positive thinking. As noted above, CBT does allow for some such strategies, even if they are less central. These strategies include therapists’ use of questions to help clients consider the adaptive value of a thought. Clients may be prompted to consider what perspective would help their mood or facilitate goal achievement. Although there has been little empirical evaluation of these strategies specifically, the appeal of fostering positive thinking has been highlighted by popular books such as The Power of Positive Thinking (Peale, Citation1952) and Learned Optimism (Seligman, Citation2006). Each offers a guide to helping people foster more positive attitudes.

Although we are not aware of specific tests of interventions focused on fostering more positive versus more accurate views, there is research showing that positive thinking interventions show promise. Shapira and Mongrain (Citation2010) assessed an internet-delivered optimism intervention that asked participants in a convenience sample to write a letter about a positive future and how they achieved it once per day for one week. The goal of this intervention was to foster positive thinking regardless of the likelihood of the outcomes imagined. Compared to controls, those completing the optimism exercises experienced reductions in depressive symptoms. A trial of brief online strength-based interventions also suggested potential benefits of positive thinking (Gander et al., Citation2013). For example, in that study, a condition that involved identifying three good things that occurred each day resulted in lower depressive symptoms than a control condition.

Though not focused on positive thinking per se, studies focused on leveraging clients’ strengths may also foster positive thinking insofar as thinking about areas of strength fosters positive thinking. In a study of an intervention prompting therapists to focus on clients’ strengths prior to the first five sessions, those in the intervention condition experienced improved therapeutic outcomes compared to a matched control group (Flückiger & Grosse Holtforth, Citation2008; see also Flückiger et al., Citation2016; Flückiger et al., Citation2021). The authors suggested that therapists’ focus on clients’ strengths may have led them to attend more to positive experiences and thereby enhance positive affect and therapeutic outcomes.

Craske et al. (Citation2019) reported a clinical trial comparing 15 weekly sessions of a novel positive affect (PA) treatment to a negative affect focused variant of CBT among those with clinically significant symptoms of depression or anxiety. The PA treatment included training in savoring pleasant moments, identifying positive aspects of neutral or negative experiences, and imagining future positive events. Six months post-intervention, the PA intervention was associated with greater improvements in PA, negative affect (NA), and symptoms of both anxiety and depression than the NA intervention. Though it is unclear what role exercises promoting positive emotions versus positive thinking per se played in the PA treatment, these findings are consistent with the possibility of therapeutic benefits or positive thinking.

Despite some studies including interventions that use positive thinking strategies, we are not aware of a study that has compared cognitive restructuring focused on accuracy and interventions focused on fostering positive thinking. To provide a focal comparison of such strategies, some studies have tested these strategies using randomization to brief interventions intended to foster different skills (Bruijniks et al., Citation2018; Bruijniks et al., Citation2020; Katz et al., Citation2016; Murphy et al., Citation2022; Shapira & Mongrain, Citation2010; Teasdale & Fennell, Citation1982; Yovel et al., Citation2014). Therefore, in this study, we provide an initial experimental comparison of a cognitive restructuring and a positive thinking intervention.

This Study

To provide an initial focal test these intervention approaches, we compared the impact of two brief worksheet-based interventions on change in affect. The interventions introduced and encouraged practice of either positive thinking skills or cognitive restructuring. We anticipated that both strategies would offer benefits, though we did not hypothesize a specific difference in the benefit of these strategies given the novel nature of our research question. We also planned to examine potential moderators of the impact of these interventions. A key moderator frequently considered when comparing psychotherapy strategies is one's facility with the skill that each approach is meant to enhance (Murphy et al., Citation2021; Sauer-Zavala et al., Citation2019; Strauman et al., Citation2006). We planned to test the skills core to our two strategies as potential moderators: CBT skills and positive thinking skills. Although findings have been mixed, there is some evidence suggesting that participants may respond more positively to interventions that harness a pre-existing skill (Cheavens et al., Citation2012). Given the mixed findings, we did not hypothesize a direction for the two potential moderators we planned to test.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 230 undergraduate students in an introductory psychology course. To be eligible for the study, participants needed to be age 18 or older. The average age of participants was 19.4 (SD = 3.8; range = 18–67), and the majority of the sample identified as female (57%). Participants identified as White (61%), Asian (20%), multiracial (8%), African American (7%), Latin American (3%), and American Indian/Native American (1%). A small number of participants also separately identified as Hispanic (7%). A minority of participants (15%) indicated that they were currently receiving treatment for a mental health condition.

Measures

Positive and Negative Affectivity Schedule (PANAS). The PANAS (Watson et al., Citation1988) is a 20-item self-report measure of positive and negative affect. Participants indicate the extent to which various emotions describe their current emotional experience, and the 10 PA and 10 NA items are summed separately. Both the PA and NA scores have strong support as measures of affect (Watson et al., Citation1988).

Competencies of Cognitive Therapy Scale – 10 (CCTS; Murphy & Strunk, Citation2022). The CCTS-10 is the shortened version of the original 29-item self-report measure (Strunk et al., Citation2014). The CCTS-10 is composed of 10 items assessing one's use of cognitive restructuring. Items are summed to generate a total score. This CBT skills score has shown evidence of adequate internal consistency and evidence of concurrent validity with another measure of CBT skills (Murphy & Strunk).

Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS). To assess positive thinking skill, we used a 10-item self-report measure describing use of positive thinking strategies that was written to parallel the content of the CCTS, highlighting use of positive thinking skills (e.g., “I caught myself thinking negatively, recognized the negativity, and thought more positively instead.”). As detailed in the online supplement, analyzes in this sample supported a single positive thinking skills factor for the measure.

Interventions

Thought Restructuring Intervention. Participants randomized to this intervention were presented with a worksheet that described how negative automatic thoughts can impact mood, highlighting how this thinking can be unduly negative, and how thought restructuring strategies can be used to combat negative thinking and improve mood. The worksheet provided several examples of using thought restructuring skills. Participants then provided their own example (using a situation from their own lives) and worked through a series of prompts to help them consider alternatives to their negative thoughts and notice benefits of considering these alternative perspectives.

Positive Thinking Intervention. Participants randomized to this intervention were similarly presented with a worksheet that described how negative automatic thoughts can impact mood. The worksheet emphasized the potential benefits of trying to alter one's thinking from negative to positive as well as the benefits of maintaining a positive outlook. Examples were given suggesting how one might identify a more positive view, without efforts to evaluate the accuracy of one's thoughts. Participants were presented with the same examples as those in the thought restructuring worksheet; however, responses demonstrating the use of positive thinking were provided. Participants then provided a personal example of a distressing situation and were asked to generate several positive thoughts in this situation. Finally, similar to the other condition, participants were asked to respond to prompts to help them notice benefits of positive thinking. This worksheet and the thought restructuring worksheet were made to be as similar as feasible while focusing on different skills. The worksheets are provided in the online supplement.

Procedure

Participants enrolled in the study through a university research experience program. Participants learned about the study through a posting accessible to participants in the program. Participants voluntarily signed up for time slots. At their chosen timeslot, participants were a consent form, followed by questionnaires assessing demographic characteristics and skill use. Just before being presented with a skills worksheet, participants reported their positive and negative affect. Participants were then presented with the intervention worksheet, with their worksheet being randomly assigned. Immediately following completion of the worksheet, participants again reported their positive and negative affect. All study materials were completed online. Participants were awarded course credit for their participation. All participants consented to study procedures.

Analytic Strategy

To test the impact of intervention on affect, we used a separate regression model for positive and negative affect. In each model, affect assessed after the intervention was the dependent variable. Affect assessed prior reviewing the intervention worksheet and intervention were included as predictors. In moderation analysis, we planned to test two initial models, one for positive affect and one for negative affect. Each model would include the following predictors: PTSS, CCTS, condition, the PTSS by condition interaction, and the CTSS by condition interaction. In the event of a non-significant moderator, we planned to remove terms associated with the moderator with the highest p-value for the interaction and test the simplified model. To address multiple testing, we utilize a Bonferroni correction for four tests (i.e., p < .0125 to adjust for four tests of moderation: PTSS and CCTS as moderators of change in negative and positive affect).

Results

To characterize the information submitted in response to the worksheet question asking participants to report on a recent distressing situation, we categorized participants’ responses. The most common topics were interpersonal situations with friends or romantic partners (35% of responses), academic concerns (32%), and concerns or conflict with family members (9%).

Affect Change Pre- to Post-Intervention

Participants reported their affect prior to and immediately following completion of the skill worksheet they were assigned. We used paired samples t-tests to evaluate whether participants’ affect changed. Across conditions, change in negative affect from pre-intervention (M = 18.97, SD = 8.01) to post-intervention (M = 17.41, SD = 7.82) was significant, with negative affect decreasing modestly: t(226) = −4.78, p < .0001, d = 0.32. In contrast, change in positive affect was near zero and not significant (pre-intervention: M = 26.31, SD = 9.14; post-intervention: M = 26.01, SD = 9.96; t(226) = −0.82, p = .41, d = 0.06).

Intervention Differences

Prior to testing condition differences, we first tested for potential condition differences prior to the intervention. There were no significant condition differences in demographic variables or in positive or negative affect pre-intervention (see online supplement). Next, we tested potential intervention differences. In the test of negative affect, cognitive restructuring yielded a very small and non-significant advantage over positive thinking (t(1, 223) = −0.70, p = .48, g = 0.09). For positive affect, positive thinking yielded a small, non-significant advantage over cognitive restructuring (t(1, 223) = −1.14, p = .26, g = 0.15).

Moderation of Affect Change

We tested two potential moderators of condition differences in change in positive and negative affect: CBT skills and positive thinking skills. As shown in , one of the four moderation tests was significant. The significant moderation effect was for CBT skills as a moderator of intervention effects on positive affect. The p-value for this test (p = .005) survived the Bonferroni corrected threshold for four tests (p < .0125). As shown in , the interaction was driven by the positive thinking skills condition producing larger improvements in positive affect among those with higher levels of CBT skills.

Figure 1. CCTS moderating intervention effects on positive affect change.

Note. Post intervention positive affect scores have been adjusted for pre intervention positive affect. CCTS = Competencies of Cognitive Therapy Scale – 10. The condition variable was coded −0.5 for positive thinking and 0.5 for cognitive restructuring. All continuous variables were standardized to mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1. N = 226.

Table I. Moderators of intervention effects on positive and negative affect.

Discussion

In this study, we provided an initial test brief positive thinking and cognitive restructuring interventions. Across interventions, we observed change in negative, but not positive affect. Interestingly, the two approaches did not show differential impact on negative or positive affect. Thus, the immediate effects of either approach on affect appeared comparable. In analyzes of potential moderators, we found that positive thinking yielded greater gains in positive affect among those with higher levels of CBT skills. This moderation effect was specific to positive affect. This is of particular interest given suggestions about the potential for leveraging positive affect as a means of improving existing psychotherapies for depression (Dunn, Citation2012). Although this was a preliminary study, our findings raise the possibility that positive thinking interventions offer benefits, particularly for those who use CBT skills more often. Although caution is still warranted, our findings suggest these strategies merit further consideration and study.

We failed to find a difference between the interventions in their effects on negative affect. Although this may be because both interventions had similar beneficial effects, it is important to note that we lacked a no intervention condition. Without this condition, we are unable to establish the causal impact of the interventions on affect across participants. Our moderation finding showed that, among those with higher levels of CBT skills, the positive thinking intervention led to greater changes in positive affect than the cognitive restructuring intervention. Thus, those who utilized realistic reevaluation more often appeared to benefit especially from positive thinking interventions.

Our focus in this study was on contrasting cognitive restructuring and positive thinking procedures. Participants determined how to apply the strategies described in the intervention materials. What goals and processes participants engage in when prompted to use procedures such as those described in our intervention conditions merits further study (see Lorenzo-Luaces et al., Citation2015). We suspect that the cognitive restructuring intervention elicited ways of thinking that involved modifying one's initial thoughts. The positive thinking intervention could have involved identifying thoughts that would lead to modifications of one's initial thoughts, but this intervention also allows for positive thoughts that would not contradict one's initial view. Relatedly, it may be that participants in the cognitive restructuring condition were more likely to adopt the goals of reducing their negative affect whereas participants in the positive thinking condition may have set goals to either reduce negative or increase positive affect. Future research that evaluates the goals participants adopted when using these strategies could clarify these issues (see Waugh, Citation2020). Whether the benefits of positive thinking among those with greater CBT skills are due to the novelty of the approach for them, their adopting different regulation goals (e.g., increasing positive affect), or their achieving greater change in perspective with this approach warrants further research.

One of the challenges in psychotherapy research is that the use of clinical trials to evaluate treatment components has been slow, costly, and has largely lacked high priority from those funding mental health research. Psychotherapy process research can provide a useful complement to clinical trial results. However, this research is limited due its reliance on sufficient naturalistic variability in the variables of interest and its inability to definitively establish causal relationships. Focused experimental comparisons, either in analog samples initially, or in clinical samples when there is sufficient confidence in the interventions to merit such a test, can fill an important research need (Bruijniks et al., Citation2018). In the current study, we were able to conduct an initial experimental test of a question that would have been difficult to address using other designs. Although the use of an undergraduate sample leaves important questions about the generalizability of our findings for future research, we view such a sample as an appropriate context for a focal test of these two approaches that had yet to be compared directly, particularly as psychotherapy developers have urged caution about the potential risk of positive thinking interventions (see Beck et al., Citation1979).

There are several important questions about interventions that seek to foster positive thinking that remain to be answered. A simple, but important question is whether these strategies lead people to alternative views that are overly positive or more positive and more accurate. Our greatest concern is whether there are downsides to positive thinking interventions that are not evident in our examination of immediate changes in affect. Positive thinking not adequately supported by evidence might prove to be fragile; consequently, it may be more difficult to persist in such thinking in the face of difficulties. A related concern is that the perspectives developed through positive thinking may yield less believable views. Even if these concerns turn out to be well-placed, the immediate benefits of positive thinking interventions may turn out to be clinically useful. These strategies could play a role in fostering new ways of thinking among those who find it difficult to see any different perspectives. Understanding the short- and long-term benefits of using approaches targeting positive thinking or the reduction of biases is an important future research direction.

This study had some important limitations. First, our sample was a general (i.e., unselected) undergraduate student sample, limiting its immediate clinical implications. As we have noted, whether our findings will extend to a sample with elevated depressive symptoms or those with clinical depression requires further study. Second, we utilized intervention materials designed for this study. Although we think the intervention materials were appropriate for testing our hypotheses, the effects of such approaches may differ in longer, more complex interventions. In a course of psychotherapy, the therapist monitors and adapts the approach as the patient progresses through treatment. Research will be needed to extend findings from focal experimental tests to the clinical contexts in which these approaches might be used. Third, we assessed coping skills among who had not been provided specific information or training regarding these skills. Although there is evidence for the validity of CBT skills measures among those who have not participated in treatment (Jacob et al., Citation2011; Strunk et al., Citation2014), it is possible that such scores are less informative than when obtained among those who have participated in an intervention that gives them a deeper understanding of what these skills involve. Fourth, as we noted earlier, our study lacked a control condition. Consequently, we are unable to determine if the interventions we studied have specific effects on affect. Fifth, our analyzes focused on immediate changes in emotion. Future research is needed to examine the impact of such strategies on depressive symptoms over a longer period.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that positive thinking interventions may have similar immediate emotional benefits as those achieved with cognitive restructuring. Among those who more frequently used CBT skills, the positive thinking intervention facilitated greater positive affect than cognitive restructuring. We encourage further study of the contexts in which positive thinking strategies may provide benefits and careful examination of the short and long-term effects of these strategies.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ackerman, R., & DeRubeis, R. J. (1991). Is depressive realism real? Clinical Psychology Review, 11(5), 565–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(91)90004-E

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities.

- Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford.

- Bruijniks, S. J., Los, S. A., & Huibers, M. J. (2020). Direct effects of cognitive therapy skill acquisition on cognitive therapy skill use, idiosyncratic dysfunctional beliefs and emotions in distressed individuals: An experimental study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 67, 101460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2019.02.005

- Bruijniks, S. J., Sijbrandij, M., Schlinkert, C., & Huibers, M. J. (2018). Isolating therapeutic procedures to investigate mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 9(4), 2043808718800893. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043808718800893

- Buchanan, G. M., Seligman, M. E. P., & Seligman, M. (1995). Explanatory style (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Carson, R. C., Hollon, S. D., & Shelton, R. C. (2010). Depressive realism and clinical depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(4), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.011

- Cheavens, J. S., Strunk, D. R., Lazarus, S. A., & Goldstein, L. A. (2012). The compensation and capitalization models: A test of two approaches to individualizing the treatment of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(11), 699–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.002

- Craske, M. G., Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Treanor, M., Dour, H., & Rosenfield, D. (2019). Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000396

- Dunn, B. D. (2012). Helping depressed clients reconnect to positive emotion experience: Current insights and future directions. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(4), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1799

- Flückiger, C., Forrer, L., Schnider, B., Bättig, I., Bodenmann, G., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2016). A single-blinded, randomized clinical trial of how to implement an evidence-based treatment for generalized anxiety disorder [IMPLEMENT]—effects of three different strategies of implementation. EBioMedicine, 3, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.049

- Flückiger, C., & Grosse Holtforth, M. (2008). Focusing the therapist’s attention on the patient’s strengths: A preliminary study to foster a mechanism of change in outpatient psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(7), 876–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20493

- Flückiger, C., Vîslă, A., Wolfer, C., Hilpert, P., Zinbarg, R. E., Lutz, W., Grosse Holtforth, M., & Allemand, M. (2021). Exploring change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder—A two-arms ABAB crossed-therapist randomized clinical implementation trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(5), 454–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000639

- Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Wyss, T. (2013). Strength-based positive interventions: Further evidence for their potential in enhancing well-being and alleviating depression. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1241–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9380-0

- Hofmann, S. G., & Asmundson, G. J. (2017). The science of cognitive behavioral therapy. Academic Press.

- Jacob, K. L., Christopher, M. S., & Neuhaus, E. C. (2011). Development and validation of the cognitive-behavioral therapy skills questionnaire. Behavior Modification, 35(6), 595–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445511419254

- Katz, B. A., Catane, S., & Yovel, I. (2016). Pushed by symptoms, pulled by values: Promotion goals increase motivation in therapeutic tasks. Behavior Therapy, 47(2), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.002

- Lorenzo-Luaces, L., German, R. E., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2015). It’s complicated: The relation between cognitive change procedures, cognitive change, and symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.12.003

- Makridakis, S., & Moleskis, A. (2015). The costs and benefits of positive illusions. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 859. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00859

- Maslow, A. H. (1950). Self-actualizing people: A study of psychological health. Personality, Symposium No. 1, 11–34.

- Murphy, S. T., Cheavens, J. S., & Strunk, D. R. (2022). Framing an intervention as focused on one’s strength: Does framing enhance therapeutic benefit? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 1046–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23302

- Murphy, S. T., Cooper, A. A., Hollars, S. N., & Strunk, D. R. (2021). Who benefits from a cognitive vs. Behavioral approach to treating depression? A pilot study of prescriptive predictors. Behavior Therapy, 52(6), 1433–1448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.03.012

- Murphy, S. T., & Strunk, D. R. (2022). The Competencies in Cognitive Therapy Scale – 10: A brief measure of cognitive behavioral therapy skills. Manuscript in preparation.

- Peale, N. V. (1952). The power of positive thinking. Prentice-Hall.

- Sauer-Zavala, S., Cassiello-Robbins, C., Ametaj, A. A., Wilner, J. G., & Pagan, D. (2019). Transdiagnostic treatment personalization: The feasibility of ordering unified protocol modules according to patient strengths and weaknesses. Behavior Modification, 43(4), 518–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445518774914

- Scheier, M. F., Matthews, K. A., Owens, J. F., Magovern, G. J., Lefebvre, R. C., Abbott, R. A., & Carver, C. S. (1989). Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: The beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1024–1040. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1024

- Seligman, M. E. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage.

- Shapira, L. B., & Mongrain, M. (2010). The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(5), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.516763

- Srivastava, S., McGonigal, K. M., Richards, J. M., Butler, E. A., & Gross, J. J. (2006). Optimism in close relationships: How seeing things in a positive light makes them so. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.143

- Strauman, T. J., Vieth, A. Z., Merrill, K. A., Kolden, G. G., Woods, T. E., Klein, M. H., Papadakis, A. A., Schneider, K. L., & Kwapil, L. (2006). Self-system therapy as an intervention for self-regulatory dysfunction in depression: A randomized comparison with cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.367

- Strunk, D. R., & Adler, A. D. (2009). Cognitive biases in three prediction tasks: A test of the cognitive model of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.008

- Strunk, D. R., Hollars, S. N., Adler, A. D., Goldstein, L. A., & Braun, J. D. (2014). Assessing patients’ cognitive therapy skills: Initial evaluation of the competencies of cognitive therapy scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9617-9

- Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193

- Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1994). Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.21

- Teasdale, J. D., & Fennell, M. J. (1982). Immediate effects on depression of cognitive therapy interventions. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6(3), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173582

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Waugh, C. E. (2020). The roles of positive emotion in the regulation of emotional responses to negative events. Emotion, 20(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000625

- Yovel, I., Mor, N., & Shakarov, H. (2014). Examination of the core cognitive components of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy: An analogue investigation. Behavior Therapy, 45(4), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.02.007