Abstract

Findings on the effects of alcohol warning labels (AWLs) as a harm reduction tool have been mixed. This systematic review synthesized extant literature on the impact of AWLs on proxies of alcohol use. PsycINFO, Web of Science, PubMED, and MEDLINE databases and reference lists of eligible articles. Following PRISMA guidelines, 1,589 articles published prior to July 2020 were retrieved via database and 45 were via reference lists (961 following duplicate removal). Article titles and abstracts were screened, leaving the full text of 96 for review. The full-text review identified 77 articles meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria which are included here. Risk of bias among included studies was examined using the Evidence Project risk of bias tool. Findings fell into five categories of alcohol use proxies including knowledge/awareness, perceptions, attention, recall/recognition, attitudes/beliefs, and intentions/behavior. Real-world studies highlighted an increase in AWL awareness, alcohol-related risk perceptions (limited findings), and AWL recall/recognition post-AWL implementation; these findings have decreased over time. Conversely, findings from experimental studies were mixed. AWL content/formatting and participant sociodemographic factors also appear to influence the effectiveness of AWLs. Findings suggest conclusions differ based on the study methodology used, favoring real-world versus experimental studies. Future research should consider AWL content/formatting and participant sociodemographic factors as moderators. AWLs appear to be a promising approach for supporting more informed alcohol consumption and should be considered as one component in a comprehensive alcohol control strategy.

Keywords:

Alcohol is the most consumed drug in the United States, with a lifetime prevalence rate of 87% among individuals >18 years-old.Citation1 Adults consume two-to-six liters of alcohol per year, on average,Citation2 and three-million deaths were attributed to alcohol misuse in 2016.Citation3 The prevalence of alcohol use disorder is also rising (12.7%/8.5% in 2016/2015, respectively).Citation4 To address detrimental alcohol-related concerns (e.g., car crashes, psychiatric comorbidities),Citation5 policies are implemented to reduce alcohol’s impact on society (e.g., taxation, advertisement restrictions).Citation6 There is growing evidence on alcohol warning labels (AWLs) as a policy to address alcohol concerns; however, research must be synthesized.

Warning labels appear on product packaging as text or text and pictorial formats, presenting facts and providing exposure to the potential physical/psychosocial harms of alcohol. AWLs are used in 49 countries with this under-utilization potentially result from industry pushback (e.g.,Citation7) Of countries with AWLs, their content/format vary widely.Citation8 Lack of consistent and global AWL implementation has resulted in few real-world studies testing AWLs particularly versus warnings on other addictive products (e.g., cigarettes).

Given the known harms of cigarettes, international guidelines (enforced under the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control).Citation9 CWLs effectively reduce cigarette use and increase motivation to quit, helpline calls, and abstinence rates.Citation10,Citation11 Similar guidelines do not exist for alcohol given conflicting evidence on their efficacy. Current AWLs are limited with unclear/abstract content, poor visibility, voluntary labeling, and no pictorial warnings/plain packaging.Citation12,Citation13 We must determine the public health benefits of AWLs.Citation12

Several reviews of the AWL literature have been conducted with mixed findings about the efficacy of AWLs.Citation14–20 Issues with these reviews include out-of-date literature searches, nonsystematic methods (e.g., rapid reviews), as well as a focus on one-to-two proxies of alcohol use, beverage warning labels (not alcohol specifically), nutritional information, and research-based AWLs. As such, an up-to-date systematic review of the AWL research, which addresses limitations of prior reviews, is critical. This review aimed to examine research on AWLs from inception. A focus was placed on comparing studies based on their methodology (i.e., real-world and experimental studies), while highlighting moderators to provide potential explanations for mixed findings across the field. Specific proxies of alcohol use were not pre-determined to expand the reviews breadth. It was predicted that AWLs would be more effective in the real-world versus experimental settings.

Methods

This systematic review adheres to the preferred reporting for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Citation21 Study protocols were pre-developed and no deviations occurred. AWL articles were searched in PsycINFO, Web of Science, PubMED, and MEDLINE databases (Appendix A). All articles published from inception (i.e., 1979) to July 26th, 2020 were included.

K. J. and M. A.-H. independently screened articles. Titles and abstracts were screened and excluded if they: were not original research; did not include an AWL; focused on alcohol ingredients/constituents and/or nutritional labels; provided general awareness/messaging; or were not written in English. No limits were set on participants or study design.

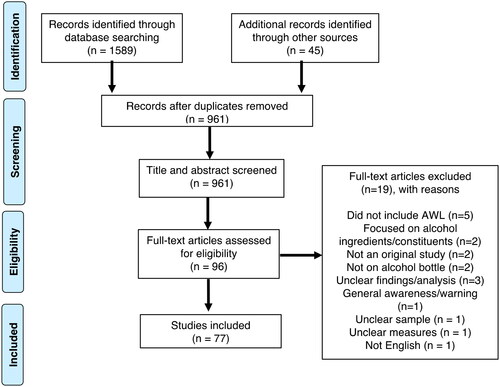

Thousand six hundred and thirty-four articles were found (1,589 from database searches and 45 from reference lists of eligible articles; ). After duplicate removal, 961 articles remained. Ninety-six articles underwent full-text screening. For full-text screening the following inclusion/exclusion criteria were added: clear purpose/research question/objective; clear participant description; clear analyses/findings. Excellent inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.84) and 82.85% agreement was obtained; disagreements were discussed to consensus. Seventy-seven articles were included. The themes of findings were subdivided into different proxies of alcohol use (described below).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram depicting the selection process for journal articles in the current systematic review.

Article data were recorded in duplicate and compared to ensure accuracy. The Evidence Project risk of bias tool, which examines studies of varying research designs incompatible with traditional risk of bias measures,Citation22 was completed individually by K.J. and E.M ().

Table 1. Summary of studies on the efficacy of alcohol warning labels.

Results

Risk of bias assessment

Moderate-to-substantial inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.54–0.79) and 76.62–94.81% agreement was obtained. Study descriptive information included: cohorts (9.09%), control/comparison (32.47%), pre–post intervention (33.77%; all interventions included participants viewing AWLs and the types of interventions can be characterized as policy-making or educational), and random participant selection (32.47%; ). Fourteen (58.33%) of studies with 2+ groups (N = 24) randomly assigned participants. One of seven longitudinal studies had retention rates ≥ 80% at follow-up. Seven (28.00%) and two (8.00%) studies with an intervention and control group (N = 25), reported equivalent sociodemographic and outcome measures at baseline, respectively.

Table 2. Results from the evidence project risk of bias assessment for all eligible articles.

Publications by year

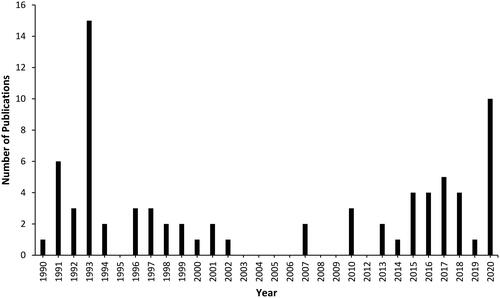

Publication of AWL research started in 1990; yearly publications peaked in 1993, declining thereafter. Yearly publications have recently increased ().

Research funding

Sixty-five studies (84.42%) reported funding source(s); none reported funding by the alcohol industry.

Knowledge and awareness

Knowledge and awareness refer to awareness of, or knowledge about, AWL or policies pertaining to them.

Real-world studies

Increased awareness of ALWs in the general population and in grade 12 students’ post-AWL implementation was found which lasted up to 3.7 years in several studies.Citation23–31

When examining specific AWL content, awareness of (a) the national drinking guidelines increased two-to-three-fold and (b) knowledge of sex-specific drinking limits by one-and-a half-fold and (b) alcohol effects increased months to the years’ post-AWL implementation.Citation32–34

AWL awareness appears dependent on sociodemographic characteristics. Those who are male, black, young, less educated, heavy drinkers, and alcohol-dependent evidence increased AWL awareness.Citation26,Citation30,Citation33,Citation35–37 For wine products, being female, younger, having children, having a higher education, and being the primary household grocery shopper increased desire to further one’s knowledge on excessive wine-drinking based on AWLs.Citation38 Pregnancy-related AWL awareness was highest among those (a) under legal drinking age,Citation37 (b) females between 19-39 years old (versus other age groups),Citation39 and (c) pregnant and postpartum females who were drinkers and educated (versus nondrinkers and “uneducated,” respectively).Citation40 In a sample of pregnant African Americans, being <30 years old increased knowledge of pregnancy-related AWLs seven months post-AWL implementation; this increased awareness lasted for three years before declining.Citation41,Citation42 Lower awareness of pregnancy-related AWLs was evident in older (>35 versus <25) and lower educated individuals.Citation40

Experimental studies

Contrary to real-work studies, findings from experimental studies are mixed. The minority of participants was unaware of AWLs pre-implementation,Citation43 cancer AWLs,Citation44 and alcohol drinkers preferred AWLs as a knowledge source.Citation45

AWL content/formatting also influences awareness and knowledge. High AWL awareness is evidenced among AWLs of horizontal orientationCitation46 and as text-warnings (versus pictorial warnings) in binge drinkers.Citation47 Higher preference of AWLs as a knowledge source are shown for (a) text warnings (versus pictorial AWLs)Citation45 and (b) large AWLs on plain packaging.Citation48,Citation49 Blank labels were preferable to those containing poison and cancer warnings.Citation50

In summary, real-world studies suggest an increase in AWL awareness post-AWL implementation, with demographic characteristics and AWL content/formatting influencing awareness. Experimental study findings are mixed, suggesting most participants are unaware of AWLs or do not prefer them as a knowledge source; AWL formatting appear to influence awareness and knowledge.

Perceptions

Perception refers to any measure of how alcohol consumers positively or negatively interpret AWLs.

Real-world studies

Increased risk perceptions of alcohol were identified following AWL implementation.Citation51 National surveys found initial increases in perceptions of alcohol use risk after AWL implementation, which decreased thereafter.Citation52–54 AWLs were effectively impacted perceptions in heavy drinker’s pre-to-post AWL implementation.Citation54 A longitudinal study also identified those with a history of drinking and driving increased their risk assessment of driving after two drinks post-AWL implementation; the same was not true for those with a history of impaired driving.Citation33

AWL content/formatting also influences risk perceptions, with less direct AWLs containing “may” reducing risk perceptions.Citation55

Experimental studies

AWLs appear to increase consumers alcohol-related risk perceptions (versus no AWL).Citation53 Similarly, combined text and pictorial AWLs decreases positive alcohol perceptions and elevates negative emotional arousal and perceptions of disease risk (versus no AWL).Citation13,Citation14 Findings are mixed, as Snyder et al.Citation56 found AWLs did not influence alcohol risk perception.

When assessing AWL content, pictorial warnings lowered consumers positive perceptions and product appeal and led to greater reactance, fear, and thinking about alcohol-related harms;Citation45,Citation57 this was particularly true when pictorial warnings were large and on plain backgrounds or depict bowel disease.Citation45,Citation58 Direct/concise statements (“alcohol is a drug”) effectively increased alcohol-related risk perceptions in binge drinkers (versus standard US alcohol warning) and when paired with pictorial AWLs.Citation53,Citation59

Although limited, real-life studies provide evidence for increased risk perceptions of alcohol post-AWL implementation; however, findings were not maintained across time. Experimental studies provided mixed findings on AWL-related perceptions; specific AWL content may increase/decrease effects.

Attention

Attention refers to objective measures of attention (e.g., eye tracking and fixation).

Real-world studies

Hobin et al.’sCitation60 findings suggest large AWLs impact on attention whether one reads, thinks about, or talks about AWLs, especially for females.

Experimental studies

Approximately, 50% of participant time is spent examining AWLs; the most time was spent focusing on product branding.Citation61,Citation62

When examining AWL content/formatting, red and larger fontsCitation63 and pictorial AWLs had higher self-reported attention and longer dwell.Citation64 Equal attention was paid to cancer warnings, national drinking guidelines, and standard drinking information,Citation32 while highly specific warnings containing “health problem,” “cancer” and/or “poison” are linked to increased attentional avoidance.Citation65

Research is lacking on consumers attention toward AWLs. Consumers appear to pay attention to AWLs; however, their attentional degree may be influenced by AWL content.

Recall and recognition

Recall and recognition refers to any indication of remembering AWLs after exposure in (recall) or shortly following exposure (recognition).

Real-world studies

Recall of AWLs increased post-AWL implementation across several studies and lasted one-to-five years, declining thereafter.Citation25,Citation28,Citation33,Citation39,Citation52 Similarly, recall increased two- and six-months post-AWL implementation is reported.Citation34 Unprompted AWL recall increased three- and ten-fold post-AWL implementation versus the control (national drinking guidelines) and prompted recall between three- and seven-fold post-implementation.Citation32

AWL recall/recognition increased among those who (a) were <40-years-old, (b) have higher education and health literacy, (c) were binge drinkers who drink out of the bottle, (d) were white, (e) believed AWLs were effective, (f) have a history of drinking and driving, (g) have exposure to AWLs (e.g., drinking 4+ drinks), and (h) were male.Citation27,Citation30,Citation33,Citation36,Citation60,Citation66–69 Recall/recognition was greater with larger AWL texts.Citation60

Sociodemographic factors also influenced recall/recognition. Recall for pregnancy AWLs was greater among females and younger individuals but recall for impaired driving AWLs was greater among males, heavier drinkers, individuals with a history of impaired driving, as well as those holding beliefs that impaired driving is hazardous or perceiving themselves to be at risk for impaired driving.Citation36,Citation39,Citation68

Experimental studies

Regarding AWL content/formatting, pictorial AWL recognition increased when (a) printed in red with icons and/or adding icons to a black AWL fontCitation70 and (b) on plain packaging.Citation13,Citation45 Inconsistencies in findings were evident.Citation47,Citation53

Recall of AWLs increased when (a) pictorial, (b) larger, (c) vertically oriented, (d) presenting birth defect information, and (e) in the consumers language.Citation23,Citation46,Citation47,Citation71 Finally, laboratory-based AWL exposure (versus no exposure) increased real-world recall.Citation72

In summary, real-world studies suggest an increase in recall/recognition of AWLs post-implementation; however, recall/recognition decreases over time. Sociodemographic and AWL content/formatting may impact recall/recognition. Recall results are mixed for experimental studies which may be attributed to moderators (e.g., pictorial versus text AWL).

Attitudes and beliefs

Attitudes and beliefs include statements about AWLs that are regarded by participants to be true, even if they are not factual.

Real-world studies

AWLs were the most publicly supported alcohol control policy in the United States 10+ years post-AWL implementation,Citation73 with exposure to AWLs increase support for policies.Citation74 Support for standard health warnings,Citation49,Citation75 national drinking guidelines,Citation32 low-risk drinking guidelines,Citation75 warnings about drinking during pregnancy,Citation76,Citation77 and cancer warningsCitation34 are high.

AWLs also influence alcohol-related beliefs, with most participants believing AWL contentCitation26 and cancer-related AWLs prompt discussions and raise awareness of alcohol-related harms.Citation78 Beliefs also differ by sociodemograpic factors with (a) light drinkers believing AWLs are effective for them, but not moderate-heavy drinkersCitation79 and (b) adolescents reporting no changes in alcohol-related harm beliefs post-AWL implementation.Citation28

AWL content/formatting may influence consumer attitudes, with AWL reference to cancer causal language generating negative alcohol-related attitudes (versus the same content with non-causal language).Citation80 Attitudes also differ with respect to sociodemographic factors, where those with a history of drinking and driving and/or impaired driving not accepting alcohol policies, including AWLs (longitudinal study).Citation33

Experimental studies

Among young people there is evidence of AWL support post-AWL implementation.Citation64 The greatest level of public support included when “cause” was presentCitation81 and cancer/birth deficit AWLs.Citation49,Citation82

AWLs considered highly credible,Citation83 more severe,Citation61 and largerCitation30 are believed to be most effective. When negatively framed and content pertains to violence/birth defects/impaired driving, AWLs are more believable, favorable, and relatable.Citation44,Citation84,Citation85 Neither positive nor negative AWL framing is more effective in changing alcohol-related attitudes.Citation86,Citation87

Negative AWL-related attitudes are common, with three-quarters of participants not viewing AWLs as acceptable and many viewing AWLs as lacking efficacy.Citation58 AWL content influences findings, with (a) AWLs containing health claims and warnings impacting alcohol-related attitudesCitation88 and (b) text-only AWLs being the most accepted.Citation89 Sociodemographic factors may also impact attitudes, with favorable attitudes toward drinking leading to disbelief of hazardous and long-term AWLs.Citation84

Collectively, real-world studies suggest high support for AWLs and attitudes/beliefs vary by AWL content and sociodemographic factors; experimental studies also found high support AWLs, but findings on attitudes/beliefs were mixed.

Intentions and behavior

Intentions to drink and drinking behavior includes measures of actual drinking behavior or likelihood of drinking in response to AWL exposure.

Real-world studies

Reduced intentions to drink and consumption may be linked to larger AWLs.Citation60 Regarding drinking behavior, light drinkers appear most strongly impacted by AWLs.Citation39,Citation78,Citation90 There were fewer sales of products with AWLs (versus non-labeled products) post-AWL implementationCitation66 Some findings suggest AWLs influence drinking, short-term warnings are more effective in changing behaviors,Citation48 and AWLs with “cause” effectively discourage consumption.Citation57 AWLs content also impacts drinking behavior, especially in females and when pregnancy-related.Citation46,Citation91,Citation92 Conversely, some studies find no effect of AWLs on drinking behavior.Citation24,Citation93

Experimental studies

AWL content/formatting influences drinking intentions. AWLs containing-specific health consequences/rebut positive social expectancies, emotionally framed messages, pictorial warnings, self-affirming intention messaging, and which depict bowel cancer reduce drinking intentions.Citation44,Citation53,Citation58,Citation89,Citation94,Citation95 Drinking intentions reduce when attention is spent toward AWLs (versus branding).Citation62 Despite these findings, male drinkers who viewed AWLs had increased drinking intentionsCitation56 and branding may have a stronger impact on alcoholic beverage choice versus AWL content.Citation86

Reductions in alcohol use following AWL exposure has been found across studies.Citation58,Citation83,Citation94 AWL content/formatting also influences results, with (a) AWL containing self-affirming reducing drinking intentions;Citation94 (b) pictorial AWLs (versus text) with liver cancer or negative alcohol expectancies reducing drinking and fewer impaired driving instances;Citation96,Citation97 (c) AWLs with novel, believed, and personally relevant information reducing drinking behaviors;Citation44 and (d) specific health consequences/rebut positive social expectancies on AWLs reducing drinking.Citation14,Citation44 Contrarily, drinking behaviors were not influenced post-AWL implementation in binge drinkers.Citation47

In summary, findings on intentions to drink and drinking behavior have been mixed. AWL content and sociodemographic factors may help explain conflicting results.

Discussion

This review highlights important findings of the impact of AWL on proxies of alcohol use which were divided into knowledge/awareness, perceptions, attention, recall/recognition, attitudes/beliefs, and intention/behavior. Conclusions differ based on the study methodology, with real-world studies being more favorable than experimental studies, on average. Findings also highlight the importance of considering AWL content/formatting and sociodemographic factors, as abundant findings suggest different findings based on the same. Results of this systematic review highlight the need for future studies on AWLs to consider moderators when analyzing data, and doing so within proper theoretical frameworks (e.g., basing the full text of manuscripts on race differences or genuine gender-based analysis).

Real-world studies suggested an increase in (a) AWL awareness, (b) risk perceptions of alcohol use (although findings are limited), and (c) AWL recall/recognition, post-AWL implementation which has decreased over time. High levels of support for AWLs were also identified. Findings on attitudes/beliefs and drinking intentions/behavior were mixed, however. One explanation for these findings is that AWLs have more universal effects on distal proxies of alcohol use (i.e., awareness, risk perceptions, recall/recognition), while their effects on attitudes/beliefs and drinking intentions and behaviors are more variable. For example, a recent systematic review by Hobin et al.Citation17 proposed a conceptual model of the expected causal pathway which explains how AWLs work. Hobin et al.’sCitation17 conceptual model suggests AWLs function by drawing in one’s attention and then increasing their knowledge of and attitudes/beliefs toward AWLs. Following this, it has been hypothesized that individuals will experience changes to their intentions to drink and then their drinking behaviors.Citation17 Although Hobin et al.Citation17 did not include all alcohol-related proxies identified in our review within their model, awareness, risk perceptions of alcohol use and recall/recognition would occur early in this model. As such, findings appear to be effective when assessing more distal proxies of alcohol use.

Findings from experimental studies were rather mixed, with some findings suggesting positive effects of AWLs, while other reported negative or no effects. One plausible explanation for the inconsistency in experimental studies stem from studies using a wide variety of warnings in terms of size, placement relative to brand imagery, and the types of warnings, all of which contribute to varied results. Contrarily, real-world studies mostly referred to the same AWLs, the ones in the United States, and therefore yielded similar results.

Across real-world and experimental studies, finding strength differed based on AWL content/formatting and/or consumer sociodemographic factors. Results suggesting AWL contact/formatting and/or consumer sociodemographic factors act as a moderator on AWL efficacy may explain mixed/conflicting findings across the field in prior literature reviews.Citation14–20 As such, it will be critical for future studies on the efficacy of AWLs to consider moderators, described throughout this review, into account.

When examining the publication timeline of articles on AWLs, there first articles were published in 1990 which coincides with the initial AWL enactment in the United States via the Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act of 1988,Citation98 peaking during 1993. The increase in publications from 2015 onward is likely related to the concern of governments regarding increasing rates of alcohol use and related harms.Citation4

The findings of this review should be considered with the following limitations and strengths in mind. Firstly, our risk of bias assessmentCitation22 highlighted the presence of potentially bias results across the most studies identified. Future research on AWLs must work to address sources of potential bias to better inform conclusions drawn from the literature. Secondly, only studies published in English were included which may limit generalizability. The number of AWL studies conducted in non-English languages is thought to be low; the future studies may wish provide insight into the effect of AWLs across non-English languages. Thirdly, we did not include unpublished studies, theses, or dissertations to control the quality of evidence being included (i.e., studies which have been peer-reviewed); however, this exclusion of unpublished studies may have biased our results in favor of positive AWL effects, also known as publication bias.Citation99 Fourthly, proxies of alcohol use identified in this review lack consistency and are differentially defined across the literature. As such, our definitions and categorization of proxies were broad. Future research should attempt to agree upon and standardize the definitions of alcohol use proxies to allow for study comparisons. Fifth, studies varied in design—where some were published pre-AWL implementation while others were post-AWL implementation.

Finally, hypotheses and methodology were not always informed by strong empirical, logical, or theoretical underpinnings. Researchers must use reviews of the literature to inform future studies on AWLs. With respect to strengths, included articles were systematically screened from inception and a risk of bias assessment was conducted. Issues with prior reviews (as outlined in the introduction) were also addressed. Proxies of alcohol use were also identified based on identified articles versus limiting results to pre-identified proxies. In sum, this review included a breadth of alcohol use proxies to provide a more comprehensive overview of extant literature than prior reviews.Citation14–20

This review highlights the evolution of AWL literature concluding that findings vary based on the methodology used (i.e., real-world versus experimental studies). Real-world studies highlighted an increase in AWL awareness, risk perceptions of alcohol use (limited findings), and AWL recall/recognition, post-AWL implementation which has decreased over time. Conversely, findings from experimental studies were mixed. Results underscore the importance of considering AWL content/formatting and sociodemographic factors in future AWL studies.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics.

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7.

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Apr 18]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Jung J, Zhang H, Fan A, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911–23. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161.

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–76. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566.

- Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Graham K, Grube J, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity - A summary of the second edition. Addiction. 2010;105(5):769–79.

- Vallance K, Stockwell T, Hammond D, Shokar S, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Greenfield T, McGavock J, Zhao J, Weerasinghe A, Hobin E, et al. Testing the effectiveness of enhanced alcohol warning labels and modifications resulting from alcohol industry interference in Yukon, Canada: protocol for a quasi-experimental study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(1):e16320. doi:10.2196/16320.

- International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Health warning labeling requirements. 2019.

- Yach D. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Lancet. 2003;361(9357):611–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12532-9.

- Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):327–37. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.037630.

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Cameron R, Brown KS. Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control. 2003;12(4):391–5. doi:10.1136/tc.12.4.391.

- Al-Hamdani M. The case for stringent alcohol warning labels: lessons from the tobacco control experience. J Public Health Policy. 2014;35(1):65–74. doi:10.1057/jphp.2013.47.

- Al-Hamdani M, Smith S. Alcohol warning label perceptions: emerging evidence for alcohol policy. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(6):e395-400–e400. doi:10.17269/cjph.106.5116.

- Clarke N, Pechey E, Kosīte D, König LM, Mantzari E, Blackwell AKM, Marteau TM, Hollands GJ. Impact of health warning labels on selection and consumption of food and alcohol products: systematic review with meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2021;15(3):430–53. doi:10.1080/17437199.2020.1780147.

- Hassan LM, Shiu E. A systematic review of the efficacy of alcohol warning labels: insights from qualitative and quantitative research in the new millennium. JSOCM. 2018;8(3):333–52. Vol. doi:10.1108/JSOCM-03-2017-0020.

- Wilkinson C, Room R. Warnings on alcohol containers and advertisements: international experience and evidence on effects. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(4):426–35. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00055.x.

- Hobin E, Jansen R, Vanderlee L, Berenbaum E. Enhanced alcohol container labels: a systematic review. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. 2022, 1–9.

- Kokole D, Anderson P, Jané-Llopis E. Nature and potential impact of alcohol health warning labels: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3065. doi:10.3390/nu13093065.

- Dimova ED, Mitchell D. Rapid literature review on the impact of health messaging and product information on alcohol labelling. Drugs: Educ, Prevent Policy. 2022;29(5):451–63. doi:10.1080/09687637.2021.1932754.

- Giesbrecht N, Reisdorfer E, Rios I. Alcohol health warning labels: a rapid review with action recommendations. IJERPH. 2022; Sep 1619(18):11676. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811676.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700.

- Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Armstrong KA, Denison JA, Yeh PT, O’Reilly KR, Sweat MD. The evidence project risk of bias tool: assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):3. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0925-0.

- Mayer RN, Smith KR, Scammon DL. Evaluating the Impact of Alcohol Warning Labels. Adv Cons Res. 1991;18:706–714.

- Scammon DL, Mayer RN, Smith KR. Alcohol Warnings: how do you know when you have had one too many? J Public Policy Mark. 1991;10(1):214–28. doi:10.1177/074391569101000115.

- Greenfield TK, Graves KL, Kaskutas LA. Long-term effects of alcohol warning labels: findings from a comparison of the United States and Ontario, Canada. Psychol Mark. 1999;16(3):261–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199905)16:3<261::AID-MAR5>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- Kaskutas L, Greenfield T. Knowledge of warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers In: Proceedings of the Human Factors Society, San Francisco, CA. 1991.

- MacKinnon DP, Fenaughty AM. Substance use and memory for health warning labels. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):147–50. doi:10.1037//0278-6133.12.2.147.

- MacKinnon DP, Nohre L, Pentz MA, Stacy AW. The alcohol warning and adolescents: 5-Year effects. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1589–94.

- Marín G, Gamba RJ. Changes in reported awareness of product warning labels and messages in cohorts of California hispanics and non-hispanic whites. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(2):230–44. doi:10.1177/109019819702400210.

- Mazis MB, Morris LA, Swasy JL. Longitudinal study of awareness, recall, and acceptance of alcohol warning labels. Appl Behav Sci Rev. 1996;4(2):111–120.

- Nohre L, MacKinnon DP, Stacy AW, Pentz MA. The association between adolescents’ receiver characteristics and exposure to the alcohol warning label. Psychol Mark. 1999;16(3):245–59. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199905)16:3<245::AID-MAR4>3.0.CO;2-S.

- Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Weerasinghe A, Vallance K, Stockwell T, Zhao J, Hammond D, McGavock J, Greenfield TK, Paradis C, Hobin E, et al. Examining the impact of alcohol labels on awareness and knowledge of national drinking guidelines: a real-world study in Yukon, Canada. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81(2):262–72. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.262.

- Parker RN, Saltz RF, Hennessy M. The impact of alcohol beverage container warning labels on alcohol‐impaired drivers, drinking drivers and the general population in northern California. Addiction. 1994;89(12):1639–51. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03765.x.

- Hobin E, Shokar S, Vallance K, Hammond D, McGavock J, Greenfield TK, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Communicating risks to drinkers: testing alcohol labels with a cancer warning and national drinking guidelines in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(5):716–25. doi:10.17269/s41997-020-00320-7.

- Parsons JA, Johnson TP, Barrett ME. Awareness and knowledge of alcohol beverage warning labels among homeless persons in Cook County, Illinois. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1993;14(2):153–64. doi:10.2190/LMGN-R5CN-J5TM-WHRF.

- Greenfield TK, Kaskutas LA. Early impacts of alcoholic beverage warning labels: national study findings relevant to drinking and driving behavior. Saf Sci. 1993;16(5-6):689–707. doi:10.1016/0925-7535(93)90031-8.

- Kaskutas L, Greenfield TK. First effects of warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1992;31(1):1–14. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(92)90002-t.

- Annunziata A, Pomarici E, Vecchio R, Mariani A. Health warnings on wine: a consumer perspective. British Food Journal. 2016;118(3):647–59. doi:10.1108/BFJ-08-2015-0300.

- Greenfield TK, Kaskutas LA. Five years’ exposure to alcohol warning label messages and their impacts: evidence from diffusion analysis. Appl Behav Sci Rev. 1998;6(1):39–68.

- Dumas A, Toutain S, Hill C, Simmat-Durand L. Warning about drinking during pregnancy: lessons from the French experience. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):20. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0467-x.

- Hankin JR, Sloan JJ, Firestone IJ, Ager JW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS, Townsend J. The alcohol beverage warning label: when did knowledge increase? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17(2):428–30. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00788.x.

- Hankin JR, Sloan JJ, Firestone IJ, Ager JW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS. Has awareness of the alcohol warning label reached its upper limit? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(3):440–4. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01072.x.

- Weiss S. Israeli, Arab, and Jewish youth knowledge and opinion about alcohol warning labels: pre-intervention data. Alcohol Alcohol. 1997;32(3):251–7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008264.

- Winstock AR, Holmes J, Ferris JA, Davies EL. Perceptions of alcohol health warning labels in a large international cross-sectional survey of people who drink alcohol. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2020;55(3):315–22. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agz099.

- Al-Hamdani M, Smith SM. Alcohol warning label perceptions: do warning sizes and plain packaging matter? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(1):79–87. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.79.

- Malouff J, Schutte N, Wiener K, Brancazio C, Fish D. Important characteristics of warning displays on alcohol containers. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(4):457–61. doi:10.15288/jsa.1993.54.457.

- Dossou G, Gallopel-Morvan K, Diouf JF. The effectiveness of current French health warnings displayed on alcohol advertisements and alcoholic beverages. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(4):699–704.

- Jones SC, Gregory P. Health warning labels on alcohol products: the views of Australian university students. Contemp Drug Probl. 2010;37(1):109–37. doi:10.1177/009145091003700106.

- Vallance K, Romanovska I, Stockwell T, Hammond D, Rosella L, Hobin E. We have a right to know”: exploring consumer opinions on content, design and acceptability of enhanced alcohol labels. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):20–5. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx068.

- MacKinnon DP. A choice-based method to compare alternative alcohol warning labels. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(5):614–7. doi:10.15288/jsa.1993.54.614.

- Mazis MB, Morris LA, Swasy JL. An evaluation of the alcohol warning label: initial survey results. J Public Policy Mark. 1991;10(1):229–41. doi:10.1177/074391569101000116.

- Graves KL. An evaluation of the alcohol warning label: a comparison of the United States and Ontario, Canada in 1990 and 1991. J Public Policy Mark. 1993;12(1):19–29. doi:10.1177/074391569501200103.

- Wigg S, Stafford LD. Health warnings on alcoholic beverages: perceptions of the health risks and intentions towards alcohol consumption. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153027. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153027.

- Kaskutas LA. Differential perceptions of alcohol policy effectiveness. J Publ Health Policy. 1993;14(4):413–36. doi:10.2307/3342876.

- Creyer EH, Kozup JC, Burton S. An experimental assessment of the effects of two alcoholic beverage health warnings across countries and binge-drinking status. J Consum Aff. 2002;36(2):171–202. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2002.tb00429.x.

- Snyder LB, Blood DJ. Caution: alcohol Advertising and the Surgeon General’s Alcohol Warnings May Have Adverse Effects on Young Adults. J Appl Commun Res. 1992;20(1):37–53. doi:10.1080/00909889209365318.

- Hall MG, Grummon AH, Lazard AJ, Maynard OM, Taillie LS. Reactions to graphic and text health warnings for cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and alcohol: an online randomized experiment of US adults. Prev Med (Baltim). 2020;137.

- Pechey E, Clarke N, Mantzari E, Blackwell AKM, De-Loyde K, Morris RW, Marteau TM, Hollands GJ. Image-and-text health warning labels on alcohol and food: potential effectiveness and acceptability. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):376. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8403-8.

- Krischler M, Glock S. Alcohol warning labels formulated as questions change alcohol-related outcome expectancies: a pilot study. Addict Res Theory. 2015;23(4):343–9. doi:10.3109/16066359.2015.1009829.

- Hobin E, Weerasinghe A, Vallance K, Hammond D, McGavock J, Greenfield TK, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Testing alcohol labels as a tool to communicate cancer risk to drinkers: a real-world quasi-experimental study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81(2):249–61. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.249.

- Sillero-Rejon C, Attwood AS, Blackwell AKM, Ibáñez-Zapata JA, Munafò MR, Maynard OM. Alcohol pictorial health warning labels: the impact of self-affirmation and health warning severity. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1403. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6243-6.

- Kersbergen I, Field M. Alcohol consumers’ attention to warning labels and brand information on alcohol packaging: findings from cross-sectional and experimental studies. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4055-8.

- Pham C, Rundle-Thiele S, Parkinson J, Li S. Alcohol warning label awareness and attention: a multi-method study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(1):39–45. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx087.

- Monk RL, Westwood J, Heim D, Qureshi AW. The effect of pictorial content on attention levels and alcohol-related beliefs: an eye-tracking study. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2017;47(3):158–64. doi:10.1111/jasp.12432.

- MacKinnon DP, Nemeroff C, Nohre L. Avoidance responses to alternative alcohol warning labels. J Appl Social Pyschol. 1994;24(8):733–53. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00609.x.

- Zhao J, Stockwell T, Vallance K, Hobin E. The effects of alcohol warning labels on population alcohol consumption: an interrupted time series analysis of alcohol sales in Yukon, Canada. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81(2):225–37. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.225.

- MacKinnon DP, Pentz MA, Stacy AW. The alcohol warning label and adolescents: the first year. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(4):585–7. doi:10.2105/ajph.83.4.585.

- Coomber K, Martino F, Barbour IR, Mayshak R, Miller PG. Do consumers “get the facts”? A survey of alcohol warning label recognition in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(816):816. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2160-0.

- Tam TW, Greenfield TK. Do alcohol warning labels influence men’s and women’s attempts to deter others from driving when intoxicated? Hum Factors Ergon Manuf. 2010;20(6):538–46. doi:10.1002/hfm.20239.

- Laughery KR, Young SL, Vaubel KP, Brelsford JW. The noticeability of warnings on alcoholic beverage containers. J Public Policy Mark. 1993;12(1):38–56. doi:10.1177/074391569501200105.

- Blume AW, Resor MR. Knowledge about health risks and drinking behavior among Hispanic women who are or have been of childbearing age. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2335–9. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.028.

- MacKinnon DP, Stacy AW, Nohre L, Geiselman RE. Effects of processing depth on memory for the alcohol warning label. Proc Human Factors Ergonom Soc Ann Meet. 1992;36(5):538–42. doi:10.1177/154193129203600514.

- Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Giesbrecht NA. Views of alcohol control policies in the 2000 National Alcohol Survey: what news for alcohol policy development in the US and its States? J Subst Use. 2007;12(6):429–45. doi:10.1080/14659890701262262.

- Weerasinghe A, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Vallance K, Stockwell T, Hammond D, McGavock J, et al. Improving knowledge that alcohol can cause cancer is associated with consumer support for alcohol policies: findings from a real-world alcohol labelling study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):398.

- Vallance K, Stockwell T, Zhao J, Shokar S, Schoueri-Mychasiw N, Hammond D, Greenfield TK, McGavock J, Weerasinghe A, Hobin E, et al. Baseline assessment of alcohol-related knowledge of and support for alcohol warning labels among alcohol consumers in northern canada and associations with key sociodemographic characteristics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81(2):238–48. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.238.

- Parackal SM, Parackal MK, Harraway JA. Warning labels on alcohol containers as a source of information on alcohol consumption in pregnancy among New Zealand women. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(4):302–5. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.006.

- Hilton ME, Kaskutas L. Public support for warning labels on alcoholic beverage containers. Br J Addict. 1991;86(10):1323–33. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01708.x.

- Miller ER, Ramsey IJ, Baratiny GY, Olver IN. Message on a bottle: are alcohol warning labels about cancer appropriate? BMC Public Health. 2016;16(:139. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2812-8.

- Kaskutas LA. Changes in public attitudes toward alcohol control policies since the warning label mandate of 1988. J Public Policy Mark. 1993;12(1):30–7. doi:10.1177/074391569501200104.

- Pettigrew S, Jongenelis M, Chikritzhs T, Slevin T, Pratt IS, Glance D, Liang W. Developing cancer warning statements for alcoholic beverages. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-786.

- Hall MG, Grummon AH, Maynard OM, Kameny MR, Jenson D, Popkin BM. Causal language in health warning labels and US adults’ perception: a randomized experiment. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1429–33. Vol. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305222.

- Andrews JC, Netemeyer RG, Durvasula S. The role of cognitive responses as mediators of alcohol warning label effects. J Public Policy Mark. 1993;12(1):57–68. doi:10.1177/074391569501200106.

- DeCarlo TE, Parrott R, Rody R, Winsor RD. Alcohol warnings and warning labels: an examination of alternative alcohol warning messages and perceived effectiveness. J Consum Mark. 1997;14(6):448–62. doi:10.1108/07363769710186060.

- Andrews JC, Netemeyer RG, Durvasula S. Believability and attitudes toward alcohol warning label information: the role of persuasive communications theory. J Public Policy Mark. 1990;9(1):1–15. doi:10.1177/074391569000900101.

- Andrews JC, Netemeyer RG, Durvasula S. Effects of consumption frequency on believability and attitudes toward alcohol warning labels. J Consum Aff. 1991;25(2):323–38. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.1991.tb00008.x.

- Jarvis W, Pettigrew S. The relative influence of alcohol warning statement type on young drinkers’ stated choices. Food Qual Prefer. 2013;28(1):244–252.

- Glock S, Krolak-Schwerdt S. Changing outcome expectancies, drinking intentions, and implicit attitudes toward alcohol: a comparison of positive expectancy-related and health-related alcohol warning labels. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2013;5(3):332–47. doi:10.1111/aphw.12013.

- Kozup J, Burton S, Greyer E. A comparison of drinkers’ and nondrinkers’ responses to Health-related information presented on wine beverage labels. J Consum Policy (Dordr). 2001;24(2):209–230.

- Clarke N, Pechey E, Mantzari E, Blackwell AKM, De‐Loyde K, Morris RW, Munafò MR, Marteau TM, Hollands GJ. Impact of health warning labels communicating the risk of cancer on alcohol selection: an online experimental study. Addiction. 2021;116(1):41–52. doi:10.1111/add.15072.

- Hankin JR, Sloan JJ, Firestone IJ, Ager JW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS. A time series analysis of the impact of the alcohol warning label on antenatal drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17(2):284–9. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00764.x.

- Hankin JR, Sloan JJ, Sokol RJ. The modest impact of the alcohol beverage warning label on drinking during pregnancy among a sample of African-American women. J Public Policy Mark. 1998;17(1):61–9. doi:10.1177/074391569801700107.

- Hankin JR, Firestone IJ, Sloan JJ, Ager JW, Sokol RJ, Martier SS. Heeding the alcoholic beverage warning label during pregnancy: multiparae versus nulliparae. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57(2):171–7. doi:10.15288/jsa.1996.57.171.

- MacKinnon DP, Nohre L, Cheong J, Stacy AW, Pentz MA. Longitudinal relationship between the alcohol warning label and alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(2):221–7. doi:10.15288/jsa.2001.62.221.

- Armitage CJ, Arden MA. Enhancing the effectiveness of alcohol warning labels with a self-affirming implementation intention. Health Psychol. 2016;35(10):1159–63. doi:10.1037/hea0000376.

- Zahra D, Monk RL, Corder E. IF you drink alcohol, THEN you will get cancer”: Investigating how reasoning accuracy is affected by pictorially presented graphic alcohol warnings. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):608–16. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv029.

- Stacy AW, MacKinnon DP, Pentz MA. Generality and specificity in health behavior: application to warning-label and social influence expectancies. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(4):611–27. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.611.

- Stafford LD, Salmon J. Alcohol health warnings can influence the speed of consumption. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2017;25(2):147–54. doi:10.1007/s10389-016-0770-3.

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. Title 27 – intoxicating liquors. Federal Alcohol Administration Act, Washington, DC, 2011.

- Nair A. Publication bias - Importance of studies with negative results! Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(6):505. doi:10.4103/ija.IJA_142_19.

Appendix A.

Search criteria

"Text warning" or "Textual warning" or "Graphic warning" or "Graphical warning" or "Health warning" or "Health message" or "Health communication" or "Warning message" or "Warning label" and Alcohol* or Drink* or Beer or Wine or Spirits