ABSTRACT

Wooden casks were used extensively to transport goods in medieval Europe but have been largely overlooked in Scandinavian marine archaeological studies. We present a study of casks recovered from the Danish-Norwegian royal flagship Gribshunden, which sank in the summer of 1495 outside Stora Ekö Island in southeastern Sweden. During excavations in 2020–2021, archaeologists recovered 135 wooden staves and heads for dendrochronological analysis. Seventy-nine percent of the samples were successfully dated and provenanced from seven different timber source areas, predominantly southeastern Baltic (59%) and Scania (22%). These results suggest the geographical extent of the late medieval Nordic timber trade. Components from several source areas were incorporated within individual casks, suggesting staves were bulk goods transported to production centres for cooperage. The dating results indicate the life span of medieval casks was just a few years. This study highlights the untapped potential of wooden casks for a wide range of research fields.

RESUMEN

Los barriles de madera fueron ampliamente utilizados para transportar bienes en la Europa medieval. Sin embargo, no han recibido la atención que merecen en los estudios escandinavos de arqueología marina. Aquí presentamos un estudio de los barriles recuperados de la embarcación de pabellón real Danes-Noruego Gribshunden, que naufragó en el verano de 1495 en las inmediaciones de la Isla Stora Ekö en el sudeste sueco. Durante las excavaciones en 2020-2021, los arqueólogos recuperaron 135 duelas y fragmentos de témpano de madera para efectuar análisis dendrocronológicos. 69% por ciento de las muestras fueron datadas con éxito y se determinó que procedían de siete fuentes de madera en diferentes áreas, entre las cuales predominan el sudeste del Báltico (59%) y Escania (22%). Los resultados sugieren la extensión geográfica del comercio de madera medieval tardío nórdico. Componentes obtenidos en diferentes áreas se incorporaron en barriles individuales, lo que sugiere que las duelas eran transportados a granel para la posterior producción en los centros toneleros. Los resultados de la datación indican que la vida útil de los barriles medievales era tan sólo de unos pocos años. Este estudio resalta el potencial escasamente aprovechado de los barriles de madera para una amplia gama de campos de investigación.

摘要

木桶在中世纪的欧洲被广泛用于货物运输,但北欧海洋考古研究却在很大程度上忽略了它的存在。我们发表的是丹麦-挪威皇家旗舰“格里芬号”上发现的木桶的研究。该旗舰于1495年夏天在瑞典东南部的大回声岛 (Stora Ekö) 外沉没。在2020-2021年的发掘过程中,考古学家提取了135份桶板和桶盖样品进行树木年代学分析。79%的样本已成功确定其年代并被指向七个不同的木材来源地,它们主要位于波罗的海东南部 (59%) 和斯堪尼亚地区 (22%)。这一结果勾勒出中世纪晚期北欧木材贸易的地理范围。单一桶体由来自多个不同地区的桶板组合而成,说明桶板是作为散装货物从采伐中心运送到制桶地。测年结果表明中世纪酒桶的寿命仅有几年时间。这项研究凸显了木桶在广大的研究领域中尚未被挖掘的潜力。

摘要

木桶在中世紀的歐洲被廣泛用於貨物運輸,但北歐海洋考古研究卻在很大程度上忽略了它的存在。我們發表的是有關丹麥-挪威皇家旗艦「格里芬號」上發現的木桶的研究。該旗艦於1495年夏天在瑞典東南部的大回聲島 (Stora Ekö) 外沉沒。在2020-2021年的發掘過程中,考古學家提取了135份桶板和桶蓋樣品進行樹木年代學分析。79%的樣本已成功確定其年代並被指向七個不同的木材來源地,它們主要位于波羅的海東南部 (59%) 和斯堪尼亞地區 (22%)。這一結果勾勒出中世紀晚期北歐木材貿易的地理範圍。單一桶體由來自多個不同地區的桶板組合而成,說明桶板是作為散裝貨物從開採中心運送到制桶地。測年結果表明中世紀酒桶的壽命僅有幾年時間。這項研究凸顯了木桶在廣大的研究領域中尚未被挖掘的潛力。

المُستخلص

تم استخدام البرامیل الخشبیة على نحو مُتسع وذلك لنقل البضائع في أوروبا في العصُور الوسطى ولكن تم تجاھلھا إلى حد كبیر في الدراسات الأثریة البحریة الإسكندنافیة. تقُدم ھذه المقالة دراسة عن البَرامیل المُنتشلة من السَفینة المَلكیة الدنماركیة النرویجیة جریبشوندن والتي غَرقت في صیف عام ۱٤۹٥ خارج جزیرة ستورا إیكو في جنوب شرق السوید. وخلال عَملیات ۲۰۲۱ قام عُلماء الآثار بالعثورعلى عدد ۱۳٥ من العِصِيّ والرؤوس الخشبیة والتي تم إخضاعھا - الحفائر والتنقیب في ۲۰۲۰ لتحلیل تأریخ الأخشاب المُستخدمة في صناعتھا. وتم بنجاح تأریخ تسعة وسبعین بالمائة من العینات والتوصل إلي سبعة مناطق مختلفة كمصادر للأخشاب والتي كان مُعظمھا من جنوب شرق البلطیق ( ٥۹ ٪) وسكانیا (۲۲ ٪). وتشُیرھذه النتائج إلى المَدى الجُغرافي لتجارة الأخشاب في بُلدان الشمال الأوروبي في العُصور الوسطى المتأخرة. ولقد آشار دمج مُكونات من عدة مَصادر مع برامیل فردیة إلى أن العِصِيّ كانت عبارة عن سلع غیر معبئة وقد تم نقلھا إلى مراكز الإنتاج من أجل التعاون. وتشیر نتائج التأریخ إلى أن عُمر برامیل القرون الوسطى كان بضع سنوات فقط. ولھذا تُسلط ھذه الدراسة الضوء على الإمكانیات غیر المُستغلة للبرامیل الخشبیة لنطاق واسع من مجالات البحث.

Introduction

The Baltic Sea is a tremendous storehouse of archaeological sites because its low-salinity waters preserve wood for centuries, most notably including shipwrecks. While the structure and construction details of these ships sunk in the Baltic Sea have attracted ample scholarly attention, the wooden casks carried within those hulls remain an untapped source of historical and archaeological information. Some detailed cask studies from other regions were published more than twenty years ago, providing ready templates (Loewen, Citation1999, Citation2007). Properly investigated, casks could prove to be as important to Northern European archaeology as ceramic amphoras have been to Classical archaeology in the Mediterranean region.

We present here a preliminary study of wooden containers recovered from the wreck of Gribshunden, flagship of King Hans (1455–1513), who ruled Denmark (from 1481) and Norway (from 1483) until his death. The vessel was likely constructed in Belgium or the Netherlands from timber growing in forests along the River Meuse in present-day Belgium and cut in the winter of 1482/83 (Hansson et al., Citation2021). The ship was in Hans’ possession before January 1486 and was used extensively thereafter for voyages in the Baltic and North Atlantic. Around 7 June 1495 (Pentecost), Hans and his retinue embarked on Gribshunden for what proved to be the ship's final voyage. He sailed with a squadron from Copenhagen toward Kalmar for a political summit scheduled to begin on 24 June with the Swedish regent, Sten Sture the Elder (ca. 1440–1503) (Etting et al., Citation2019; Wegen et al., Citation1864). Calamity struck during a stop en route near the town of Ronneby in the Blekinge archipelago, then a Danish territory but since 1658 part of Sweden. While Hans was ashore, the ship reportedly caught fire, suffered an explosion, and sank at anchor about 120 m north of Stora Ekön Island. The ship settled onto a soft sea floor with a starboard list of ∼27 degrees. Water depth at the site is now 10 m. Unburned rigging and probably portions of the upper superstructure stood above the water surface after the loss. Elements of the vessel and the material it carried likely were salvaged immediately. The hull now is embedded in the sediments from the keel to the level of the first deck, and fine-grained sediments have completely infilled the hull.

The wreck was re-discovered by sport divers in the 1970s, and it was the subject of six intermittent archaeological interventions between 2000–2015 led by Kalmar Museum and Södertörn University (e.g., Einarsson, Citation2012; Einarsson & Wallbom, Citation2001, Citation2002; Eriksson, Citation2015); so far only a cumulative paper of those studies has been peer-review published (Adams & Rönnby, Citation2022). In 2019, a new interdisciplinary research effort was initiated by Blekinge Museum and Lund University, including excavations and revisiting artifacts previously recovered. Publications on a variety of topics are now published or in preparation, with studies of the ship itself forthcoming (see e.g., Eriksson, Citation2020; Hansson et al., Citation2021; Macheridis et al., Citation2020).

Gribshunden is a particularly rich archaeological and historical site. The presence of the monarch on board and the secure date of sinking allow exceptional conclusions to be extracted from some of the artifacts (see e.g., Ingvardson et al., Citation2022). From Gribshunden's casks, information about the lifespan of wooden containers in the late medieval period can be obtained via dendrochronology. Further, the combination of the people on board and their intended mission provides a clear window on late medieval politics and economics. The vessel was conveying the Danish-Norwegian king on a diplomatic mission to Sweden to reconstitute the Nordic Union of those three countries. The casks in the ship's hold were not generic trade goods as would be found on the wreck of a merchant ship, nor were they standard provisions as might be present on the wreck of a warship. Instead, these casks contained foodstuffs and supplies intended for immediate consumption by the king, noblemen, and ship's complement during a relatively short summer cruise. These victuals were high-prestige items that would not only satiate the king and his noble entourage, but also were intended to impress the Swedish nobles at the planned summit in Kalmar (Macheridis et al., Citation2020). The casks studied here were recovered from the stern hold of the ship, in context with a variety of high-value prestigious items. As excavations continue in this locus and others, it may be possible to discern social stratification relating to diet, by differentiating containers carrying high-value foods and the casks containing standard fare for the sailors and soldiers in the complement.

Throughout this study, we refer to wooden containers generically as ‘casks’ unless the specific term ‘barrel’ is appropriate. Casks were the ubiquitous European cargo container from at least the early medieval period through the mid-20th century, and are still used today in some industries (Bevan, Citation2014). In the late medieval period when Gribshunden sailed, these wooden containers ranged in sizes, each with a specific designation and often with a capacity standard related to the product contained within. The English names were firkin, kilderkin (or half-barrel or rundlet), barrel, hogshead, tierce, puncheon, butt (or pipe), and tun (Zupko, Citation1968). Volume divisions, capacity standards, and naming conventions for wooden containers were similarly employed across Europe. For instance, in the Low Countries, a region with close economic and political connections to late medieval Denmark, the terms applied to similar volume-dependent wine containers were vaatje, kinnetje, halve ton, anker, ton, oskhoofd, aam, pijp, and vat/voeder. All manner of goods were shipped in wooden containers. Foodstuffs such as honey, butter, apples, raisins, nuts, malt, beans, peas, grain, barley, and oats shipped in casks. Gunpowder, iron, tar, coals, potash, lime, vinegar, and candles were transported in barrels; and no doubt much more (Zupko, Citation1968). Crews of naval vessels and merchant ships relied for their sustenance on provisions carried in wooden containers of several sizes (Söderlind, Citation2006). Across land and sea, casks carried a huge proportion of medieval Northern Europe's products.

Particularly for archaeologists in the Baltic region, wooden casks could be the Northern European analogue to ancient Mediterranean amphoras. While amphoras have been the subject of thousands of scientific manuscripts describing typology, chronology, contents, and the political-economic factors of their production and consumption, casks have been largely ignored in the Nordic region. A handful of dendrochronological studies have been performed on staves from medieval land sites, e.g., Crone and Fawcett (Citation1998), Daly (Citation2007, Citation2011), and Robben (Citation2008). Very few cask cargoes found in Baltic shipwrecks have been investigated,Footnote1 with two recent and notable exceptions serving as models to emulate. An interdisciplinary study was performed on 27 wooden container components from the mid-15th century Skaftö Wreck on the Swedish west coast. The casks contained lime, tar, speiss ingots, and provisions. The primary reason for the study was to determine a terminus post quem for the vessel's sinking. Dendrochronology of ship timbers provide a building date in the late 1430s; for the cask components, a felling date of 1439. Dendrochronology of timber cargo suggest that it was cut 1440–1443, suggesting a sinking date soon after (Von Arbin, Citation2014; Von Arbin et al., Citation2022). The most comprehensive study of casks to date relates to the Copper Wreck in Gdansk, Poland. Seventy-four casks, referred to as barrels, were recovered from that wreck, and 59 have been restored after conservation. They carried iron (44 barrels), wood tar (15 barrels), and potash. Dendrochronology of the ship timbers shows a felling date around 1399, while dendrochronology of the cask components indicates a sinking date of 1405–1408 (Ossowski, Citation2014).

The specific aims of the Gribshunden dendrochronological study are to determine the age and provenance of cask staves recovered from the wreck. This will help answer several research questions such as (i) the timber source area (ii) the cask construction locality (iii) Danish cask size and volumetric standards. In addition, because the date of Gribshunden's loss is documented, we can begin to determine (iiii) the lifespan of a cask in the late medieval period. If additional studies of casks from other securely-dated shipwrecks mirror the results obtained from Gribshunden's casks, then the utility of cask dendrochronology for closely determining the date of loss for unidentified wrecks will be further demonstrated.

Cask parameters will give an insight into the structure of Baltic societies and political-economic systems, and changes over time in that region and with its trading partners. Medieval cask volumetric standards are unknown for the Nordic states of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. If there was a state-imposed Nordic volumetric standard or standards in the late medieval period, it should be apparent in the casks of the Nordic king's flagship, Gribshunden. If so, did it conform to those of Denmark's largest trading partners, particularly the Low Countries and the Hanseatic League?

An area of future research is determining the contents of the casks in the absence of visible remains. This may be possible with chemical, aDNA, and other methods, but initial efforts conducted on Gribshunden casks have been inconclusive.

Material and Methods

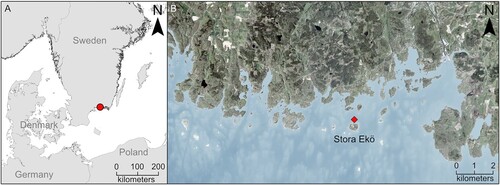

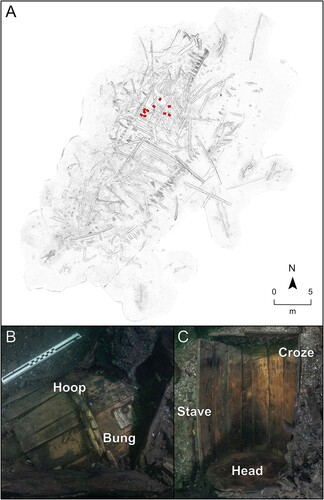

The Gribshunden shipwreck is situated north of Stora Ekön Island in the Blekinge archipelago, southeastern Sweden (). The water depth at the site is 10 m, and the sea floor consists of fine-grained sediments overlying clay substrate. The hull structure is intact from keel to first deck, and large coherent sections of hull and superstructure have fallen outboard and are buried under sediment. The cask components were recovered during excavations within the hull, aft of the waist and under the lower deck level. The samples studied here consist of cask staves and heads and were retrieved from Gribshunden during four separate field campaigns. The 2005 exploratory excavation was conducted at the stern along the centreline, opening a 1 × 1 m trench. This activity produced samples 55883–55900, which were subsequently conserved at the Kalmar County Museum. A 2 × 6 m trench opened in 2019 straddles the hull on the starboard side, slightly aft of amidships. Sample 55882 was retrieved in 2019. Samples 54020–54087 were retrieved in the autumn of 2020; these were cask components put aside during the 2019 excavation. A 2 × 6 m trench opened in 2021 is aft and adjacent to the 2019 trench, and entirely within the confines of the hull. Samples 54088–54099 and 54120–54155 were retrieved in 2021. The find loci of the cask samples retrieved in 2005, 2019 and 2020 are documented, but the components of the various casks were cached together on the sea floor adjacent to the trench, so their connections to each other are undetermined. The samples retrieved in 2021 are from four intact or semi-intact casks recovered from the excavation trench. Each of these four casks was excavated, disassembled, and retrieved as a separate coherent unit (A). The cask terminology is described in and .

Figure 1. A. The position of the wreck site (red circle) in southern Sweden. B. The wreck site, marked by the red square, is situated north of Stora Ekö Island (Authors).

Figure 2. A. Site map of the wreck. Cask positions are marked by red squares. B & C. Terminology used in describing the different parts of wooden casks (drawing by Frida Nilsson, Mediatryck).

All samples were analysed at the Laboratory of Wood Anatomy and Dendrochronology at the department of Geology at Lund University. The fragile water-logged staves and heads were frozen and thereafter sawed to expose the annual rings at the thickest section of each cask element to maximize the number of rings for study. The samples were prepared for measurement by cutting the exposed surface with an industrial razor blade to make the rings as distinct as possible. The samples were measured with a Rinntech Lintab 6 tree ring station in combination with TSAPWin software (Rinn, Citation2003). Each sample was measured twice, first on a clean surface in order to better detect any remaining sapwood, and then a second time with chalk applied to better distinguish the earlywood-latewood border and as a control for the first measurement. Ring-width chronologies were constructed after comparisons between the ring-width series, analysed with common statistical and visual methods (Pilcher, Citation1990). Quality control of the ring-width chronologies were then performed in the COFECHA software (Holmes, Citation1983).

The individual ring-width series were matched against each other (supplementary information). The individual ring-width series and the resulting ring-width chronologies were then matched against the large network of reference chronologies harboured at the Laboratory of Wood Anatomy and Dendrochronology. This generated calendar ages and timber provenance determination of the samples. This matching was performed in the TSAPWin software using the Baillie-Pilcher t-value (Baillie & Pilcher, Citation1973) and the gleichläufigkeit (glk) (Schweingruber, Citation1988) statistical parameters together with visual examination of the cross correlation.

Results

In total 135 samples were retrieved and analysed from the Gribshunden shipwreck. All but five of the samples are of oak. The exceptions are three beech samples and two samples of ash. The sample population is composed of 113 cask staves and 22 components from cask heads. The staves were categorized as complete or fragmentary based on the edge shape and presence or absence of the croze (the groove incised near both ends of each stave, cut to receive the head), and the length, thickness, and maximum width of staves and heads were measured and recorded.

Thirty-one (31) of the 113 staves were categorized as complete and a total number of 49 staves had both crozes preserved, making it possible to determine the size of the corresponding cask (). The lengths of the intact cask staves are between 730 and 755 mm, with the exception of one stave measuring 488 mm. The distance between the crozes ranges between 625 and 660 mm, with the exception of three staves where the distance is between 425 and 430 mm. This suggests there are two different sizes represented in the Gribshunden casks.

Table 1. Sample description and dating information of the barrel staves and heads.

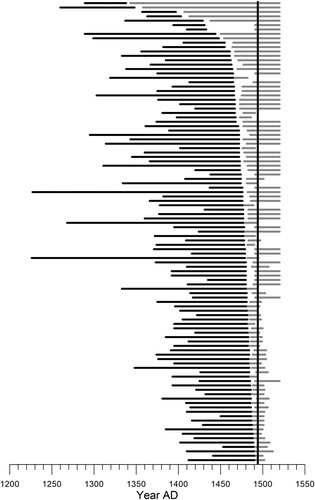

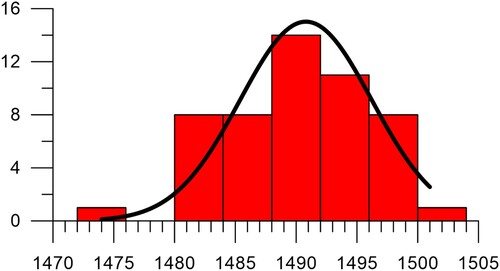

Dates were successfully determined for 107 (79%) of the 135 samples (). No sample has waney edge preserved, but sapwood is present in 56 (43%) of the oak samples. This allows a possible felling year to be calculated based on the normal amount of sapwood rings in oak from different geographical regions (). For the samples which lack sapwood, a minimal number of years has been added to the year of the outermost ring to determine a so-called terminus post quem dating, the oldest possible year of felling. The samples have between 27 and 254 rings and the ring-width varies between 0.64 and 4.34 mm.

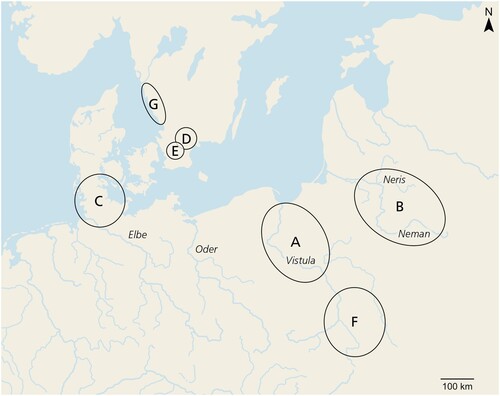

The dated samples have been placed in seven groups, A-G, based on their correlation with each other (). The resulting seven chronologies are presented together with the respective best matching reference chronology in . The chronologies span between 47 and 239 years and contain between two and 44 samples.

Table 2. Description and correlation information of the chronologies and the reference chronologies.

Discussion

Timber Provenance

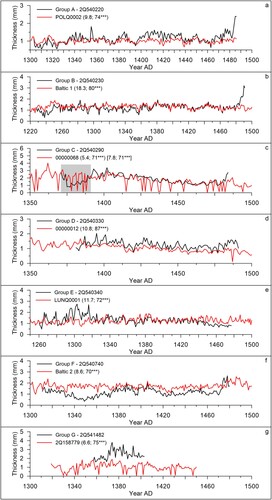

The Group A chronology correlates to reference chronologies from the Baltic region. The highest correlation is found with the Gdansk reference chronology (t-value 9.8; glk 74***) (a), which consists of timber from the East Pomerania region in Poland (Hillam & Tyers, Citation1995; Wazny, Citation1990). Slightly lower correlations are obtained with the Baltic 1 and Baltic 2 chronologies (Hillam & Tyers, Citation1995). The Group A timber should therefore be sourced from the Vistula River catchment area. During the 15th century the Masovia and Podlaise regions were the major timber suppliers (Wazny, Citation2005) and most likely the source area for the Group A timber. The normal amount of sapwood rings in Polish timber used to estimate the felling year is 9–24 (90% confidence interval) with an average number of 16 rings (Haneca et al., Citation2009).

Figure 4. Plots a-g showing the respective chronology (black lines) and its correlation to the highest correlating reference chronology (red lines) (Authors).

The Group B chronology shows a very high correlation to the Baltic 1 reference chronology (t-value 18.3; glk 80***) (b) (Hillam & Tyers, Citation1995), as well as to other reference chronologies of Baltic timber found in the Netherlands. The correlation between the Gdansk and Baltic 1 reference chronologies after the 13th century is low and the source area for the Baltic 1 reference should be found east of the Polish border (Vitas, Citation2020; Wazny, Citation2002). This statement is confirmed by Daly and Tyers (Citation2022), which suggests the Baltic 1 chronology source area can be found in western Lithuania around Klaipeda and the lower Neman River. High correlations between the Group B chronology and Lithuanian reference chronologies suggest the Group B timber source area can be found in eastern Lithuania and northwestern Belarus (Wazny, pers. com.). For the Group B timber 6–19 sapwood rings (median 12 rings) (95% confidence interval) has been used to calculate the felling year (Sohar et al., Citation2012).

The Group C chronology correlates with several reference chronologies from Lübeck, Hamburg, Schleswig and Sønderjylland (southern Jutland). The highest correlation is obtained with the 00000068 reference chronology from Lübeck (t-value 5.4; glk 71***) (c). By excluding the first 20 rings in the Group C chronology higher correlations are obtained with all matching reference chronologies. The Group C timber is therefore most likely sourced from an area in the Schleswig-Holstein and Sønderjylland regions in northwestern Germany and southernmost Jutland in Denmark, respectively. The normal number of sapwood rings in timber from this region is 10–30 (average 16 rings), which has been used to calculate the felling year (Haneca et al., Citation2009).

The Group D chronology correlates well with numerous reference chronologies from southern Sweden in general, and the county of Scania (Skåne) in particular. The highest correlation is obtained with the 00000012 reference chronology (t-value 10.8; glk 87***) constructed of Scanian timber (d). High correlations between the Group D chronology and reference chronologies from several churches in northeastern Scania built with local timber suggest that the Group D timber is sourced from an area north and east of the town of Hässleholm that extends towards the Scania county border. The normal number of sapwood rings in Swedish oak is 10–24 with an average of 15 rings (Linderson pers. com.).

The Group E chronology also correlates with several reference chronologies from southern Sweden, but Group E does not correlate well with Group D, indicating the trees grew in two different areas. The highest correlation for Group E is obtained with the LUNQ0001 reference chronology (t-value 11.7; glk 72***) (e) containing samples from several archaeological excavations from the city of Lund. The LUNQ0001 reference is constructed from a large number of samples from different source areas and should not be used for precise provenance determination. However, the Group E chronology also shows a high correlation to the Norra Mellby church in central Scania which was built from locally sourced timber, pointing to that region as a possible source area for Group E.

The Group F chronology correlates well with the Baltic 2 reference chronology (t-value 8.6; glk 70***) (f) (Hillam & Tyers, Citation1995), as well as a few other Baltic timber reference chronologies. The Group F chronology also correlates fairly well with both the Group A and Group B chronologies, suggesting that the Group F source area might lie somewhere between their respective source areas. The Baltic 2 source area is believed to have been in lower Silesia, around the region where the Bug and Narew rivers connects to the Vistula (Daly & Tyers, Citation2022). Therefore, the Group F timber source area could be further upstream from the Group A timber on the Vistula River, or on an eastern tributary in the southeastern quarter of Poland.

The Group G chronology solely consists of two samples which correlate well with reference chronologies with timber from constructions and archaeological excavations on the Swedish west coast (t-value 6.6; glk 75***) (g), which is the most probable source area for the Group G timber.

Provenance Areas and Timber Trade

The cask timber is sourced from several distinct geographical areas (). Group B, from eastern Lithuania and northwestern Belarus, is the most common provenance region representing 41% of the dated timber (). Group C contains 18 samples, or 17% of the dated timber. However, 12 of these samples were produced from the same tree; therefore, it is more accurate to state that 7% of the dated timber was produced in northwest Germany/southernmost Denmark. We consider Group A, Group B, and Group F as Baltic timber, and Group D and Group E as Scanian timber. This reveals a pattern of timber use and availability: 59% is Baltic timber, 22% is Scanian timber, and the remainder is made up of smaller amounts of timber from western Sweden and areas in northwestern Germany and southernmost Jutland.

Figure 5. Map of Northern Europe showing the timber source area of Groups A-G (map by Frida Nilsson, Mediatryck).

According to Wazny (Citation2005), during the 15th century the forests in the Masovia and Podlaise regions in what was then the Kingdom of Poland were depleted due to intensive timber extraction. This led to an eastward shift into the Duchy of Lithuania to satisfy the need for timber exports. This trend is indirectly evident in the cask timber from Gribshunden, as the dominant timber source is Lithuania and northwestern Belarus (Group B), although some timber from Poland was still available as seen in the timber from Group A. Of the timber available within lands controlled by King Hans, Scanian timber dominates, but a smaller amount of Schleswig-Holstein and Sønderjylland timber is also present.

The Gribshunden casks offer direct information about forest depletion. By comparing the average ring width for Groups D and E (1.25 and 1.30 mm, respectively) with the ring width of Group C (1.81 mm) we can see that the average ring width is about 0.5 mm wider in Group C. Trees growing in an open woodland grow faster than trees growing in a dense forest (e.g., Domínguez-Delmás et al., Citation2013; Schweingruber, Citation1996), with the result that the ring widths of fast-growing trees are wider than slow-growing trees. The ring widths from the Gribshunden staves indicate that the forests in Schleswig-Holstein and Sønderjylland were depleted, whereas there were still densely forested areas available for timber extraction in Scania. Low average ring-widths of 1.14 to 1.22 mm are also found in the Baltic timber () suggesting available dense forests for timber extraction. The high average ring-widths in the timber from western Sweden can be explained by the low number of samples (only two) and the fact that these samples contain very few rings (only 41). These samples of timber are not well-suited for interpretation of forest conditions in the area.

Together, the average ring widths and the number of samples from the different timber source areas apparent in the Gribshunden casks support the hypothesis of late medieval forest depletion in western Europe driving the need for imported Baltic timber described in e.g., Bridge (Citation2012) and Wazny (Citation2005).

Cask Identification Possibilities: Volume, Timber Source, Marks, Re-use/Lifespan

Both the cask staves and the cask heads have been cut radially from the tree trunks. 43% of the cask samples contain sapwood, which is rather surprising as the softer sapwood should weaken the cask structure. This suggests that casks were not meant for long-term use. This is further supported by the calculated felling years for the dated cask samples containing sapwood. The oldest sapwood-containing sample (no 54030) has a calculated felling year of 1467–1482, and only a further two samples have a youngest possible calculated felling date in the 1480s (). The youngest sample (no 54062) has an earliest possible calculated felling year of 1494, one year prior to Gribshunden's loss. However, in rare cases the amount of sapwood rings can deviate from the norm, making it possible that this tree was felled one or two years before 1494. Based on the average number of sapwood rings for each provenance region we can estimate the average year of felling for each tree (), and the sample population as a whole. The average felling year for the whole sample group is 1490.8 (). Before coopers built the staves into casks, the semi-finished staves had to be seasoned for some period of time; an 18th century document indicates this seasoning took two years (Daalen, Citation2021). Allowing for some time to transport the freshly-cut wood from forest to cooperage, some time to work it into semi-finished staves, and as long as three years to season the wood before final finishing (Waelput, Citation2004), this indicates that the casks that were on Gribshunden when the ship sank had been in use for an average of two years or less. Turnover time for the containers was short, but it is possible that casks in royal possession for the Kalmar voyage would have been newer (perhaps first-use) and higher-quality than standard casks.

Figure 6. Histogram showing the average felling year for the barrel timber by using the average number of sapwood rings for each region (Authors).

Two distinct sizes appear among the Gribshunden cask staves. A majority (43 of 46) of staves with both crozes preserved have a distance between the crozes of 625 to 660 mm, whereas three staves have a distance of 425 to 430 mm between the crozes. The larger size is represented in the sampled casks 1–4. Using the distance between the crozes for cask 1 and 3 together with the radius of the intact cask heads (sample no 54091: 440 mm and 54135: 425 mm, respectively) we can roughly estimate the volume to 99 litres in cask 1 and 94 litres in cask 3. More speculatively, the shorter stave size can be combined with sample 54023, an intact cask head with a smaller radius, to calculate a possible volume of 43 litres. These estimates suggest that the smaller casks held approximately one-half the volume of the larger casks. We note, however, that medieval casks were not symmetrical; the heads on each end of a cask could be different diameters by design. Also, the bulge in the cask form increases the volume compared to a straight cylinder (Loewen, Citation2007; Meskens et al., Citation1999).

For comparison, the casks from the Skaftö Wreck (circa 1443) also appear to have been of two sizes. Those containing tar had overall stave lengths (not croze distance; these staves had no crozes) of 67 cm and head diameters of 40 cm for an estimated cask volume of 80 litres. Those containing lime had overall stave lengths of 79 cm and head diameters of 39 cm for an estimated volume of 90 litres (Von Arbin, Citation2014; Von Arbin et al., Citation2022). The casks from the Copper Wreck (ca. 1407) are less uniform. Those containing iron ranged in height from 67 to 80 cm, and in diameter from 29 to 34 cm. One outlier was 80 × 23 cm. The casks containing tar were similarly inconsistent, with stave measurements varying from 67 to 81 cm (overall length, not croze distance) and head diameters 38 to 46.5 cm. Estimated capacities varied from 69 to 99 litres (Ossowski, Citation2014).

It is possible that the casks from these three wrecks show a slow shift toward standardization in the late medieval period, though the sample sizes of medieval wrecks and the casks they carried is too small for definitive conclusions. Documents show that by the late medieval period in Europe standards were enforced on weights and measures for many goods, for example by the Hanseatic League (Witthöft, Citation1979). However, the standards were imposed by different Hanse towns and were not always implemented widely. From the late 14th century, the Falsterbo/Skanör herring fishery in Scania exported its salted catch in ‘standardized Rostock barrels’ containing 830–840 herring (Jahnke, Citation2009). Despite this Rostock herring cask standard, set in 1375 by the Hanse merchants in that town, a variety of cask sizes continued to be used in the Nordic area throughout the medieval and into the early modern period (Nilsson, Citation1987). It is unknown whether these Nordic cask volumes conformed to Hanseatic attempts at standardization. Similarly, officials from several towns in 15th century Holland also imposed a standard volume for herring barrels. Those local authorities inspected the output of coopers, verified the casks’ volumes through a variety of means including go/no-go gauging and calculations of measurements, and then certified the barrel by applying their urban stamp. Any unmarked containers encountered by inspectors in the markets were confiscated and destroyed. Likewise, local and regional cask volume standards for beer, wine, butter, and many other goods were enforced in Holland and elsewhere throughout Europe (Dijkman, Citation2011; Lane, Citation1964; Meskens et al., Citation1999). The result of these local standards is a dizzying variety of measures and volumes, many of which were never codified, but passed down orally and therefore lost to history (Zupko, Citation1968).

Timber source area is not a reliable indicator of either cooperage location or content origin. Gribshunden cask 1 consists of timber from five source areas (). Cask 2 consists of 12 staves from a single tree which grew in Schleswig-Holstein or Sønderjylland together with one stave and one head from eastern Lithuania-northwestern Belarus, whereas cask 3 contains timber from three different source areas. The variety of wood sources in each cask suggests that staves were shipped from the timber source areas as bulk goods, and then were transhipped to cask production centres where coopers built the containers according to local standards. Both the Copper Wreck and Skaftö Wreck carried cargo of possibly semi-finished staves, providing direct evidence of this trade (Ossowski, Citation2014; Von Arbin, Citation2014; Von Arbin et al., Citation2022). The relatively large amount of local Scanian timber suggests the Gribshunden casks were constructed within the Danish kingdom.

Timber sourcing for cask construction may be an interesting topic for future research into forest sustainability and resource depletion. The market for casks was enormous in the medieval period. The scale of wood consumption is suggested by glimpses of data. By one estimate the Scanian herring fishery in Falsterbo/Skanör required 300,000 barrels annually for the fish, and more than 16,000 barrels for salt to preserve them (Etting, Citation2004). Other estimates place the minimum average yearly herring catch at around 100,000 standard Rostock barrels (Jahnke, Citation2009). This single commodity from one local fishery required between 1 and 5 million staves each year, depending on the extent of the catch, re-use of older barrels, and average number of staves per barrel. A later example of the volume of the continuing trade in barrel staves comes from Ireland in the early 1600s. The Boyle family of the Earl of Shannon cleared forest near Cork, and sold some four million barrel staves (Horgan, Citation2013). However, by this time the forests of North America were supplying cask staves and other timber products to the European market, causing the price to plummet.

The data from Gribshunden suggest that in the late medieval period, wooden casks had an expected lifespan of only a few years. However, it is possible that the monarch's presence on this voyage skews the data; perhaps new casks were employed for him. If so, then it is possible that those casks could have been re-used for some time if not lost in the wrecking event. Their physical properties indicate that they were not intended for long-term heavy usage or extensive re-use; the staves are too thin, and the inclusion of sapwood in several of them would have decreased the strength of the containers. A short lifespan meant frequent replacement at some cost to the buyer, but this economic burden was not great at the unit level; casks were cheap to produce and purchase. For example, empty barrels recovered from two shipwrecks in England in the years 1385 and 1387 were valued at 3d (pence) (Johnson, Citation2015). Empty wine pipes (capacity about 477 l, equal to four English standard volume wine barrels of about 119 l) provided in 1496 for Henry VII's great ship Sovereign cost 12d each (Oppenheim, Citation1896). At the time, the daily wage in England for a skilled worker was approximately 8d, so a single empty standard barrel was worth the equivalent of less than a half-day of labour. They were not single-use containers, but they were inexpensive enough to be readily disposable. No doubt often re-purposed as firewood, and they occasionally were re-used to shore up wells or privies. For maritime archaeologists, this apparent short lifespan may be a useful factor in dating unidentified shipwrecks. Just as dendrochronology may reveal the date of a ship's construction to within a few years, dendrochronological studies of the ubiquitous barrel cargoes contained within wrecks can narrow down the sinking dates. In the case of Gribshunden, dendrochronology of the ship timbers suggests a construction date after 1483, while the cask dendrochronology indicates a date of loss no earlier than 1491. Historical documents record the actual sinking event occurred in June 1495.

Despite the complexities of the problem, possibilities may exist for determining the origin and contents of casks by study of their volume and dimensions of the staves. Intact barrels may allow calculation of their volumetric standards, which may reveal their place of manufacture (as separate from the source of their timber), and possibly even the identities of the goods contained within. For example, in medieval England and continuing until 1688, a barrel of wine generally held 31.5 wine gallons (119 l), as did barrels of oil and honey. A barrel of ale contained 32 gallons (148 l) as did barrels containing soap or butter; a barrel of beer contained 36 gallons (166 l); a barrel of herring or eels contained 30 gallons (114 l), except when eels were transported in the 42-gallon (159 l) barrels used for salmon. Gunpowder was measured by weight not volume, so these barrels held one hundredweight (45.359 kg) (Zupko, Citation1968).

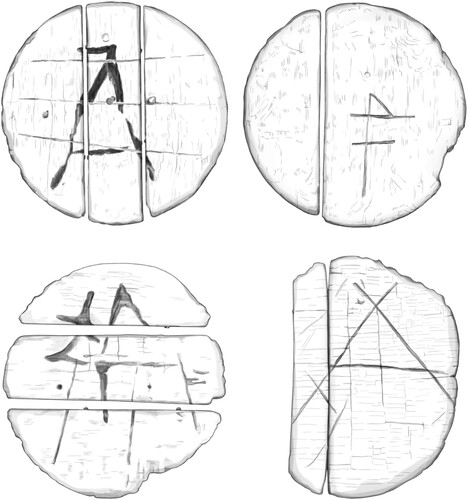

Markings applied by coopers, merchants, or local administrators are another potential source of information. Such marks appear on some barrel components recovered from the Copper Wreck and from Skaftö Wreck (Ossowski, Citation2014; Von Arbin, Citation2014; Von Arbin et al., Citation2022). Four of the Gribshunden cask components display marks, but their purpose and the identities they represent are as yet unknown (). Guild and makers’ marks are well-documented from late medieval and early modern Dutch primary sources, many available online. Baltic archives have produced some records (Svenwall, Citation1994), but more research is needed if this method eventually will allow direct connections among casks and the individuals who produced them.

Figure 7. Cask heads with markings imprinted from Gribshunden (drawing by Frida Nilsson, Mediatryck).

Clues to contents may be divined from other physical characteristics, but again the situation is complicated and clarifying archival sources may not exist. Tare weight is one example. In 16th century England, the 32 gallon barrels used for soap were mandated to weigh 32 pounds empty, while 32 gallon barrels for butter were to weigh only 26 pounds (Zupko, Citation1968). The staves of the soap barrels must have been thicker than those used for butter. Variation in stave thickness provided opportunity for merchants to cheat their customers, and temptation that has always existed with trade (Kadens, Citation2019). In Holland during the mid-15th century, butter barrels were deliberately fashioned with thicker staves than usual. Importers in Cologne lodged complaints with Dutch merchants that a full barrel weighed the mandated amount, but had too much wood and not enough butter (Dijkman, Citation2011). The Gribshunden containers suggest that some casks on board were more heavily constructed than others. Casks 1–3 had an average stave thickness of 10.2 mm. The staves of cask 4 are 13.4 mm on average, indicating a sturdier construction. The three complete staves from one smaller container with a croze length of ∼425 mm also had an average thickness of 13.4 mm. In the total Gribshunden population, the staves vary in thickness from 7.0 to 16.1 mm, with an average of 11.8 mm (standard deviation 2 mm).

Three of the recovered Gribshunden cask staves feature square inlets, or bungs, including sample 54076, 54152, and from cask 2 sample 54128. On an intact example a textile patch sealed the interface between bung and the stave. Square bungs have been associated with beer casks (Hyttel et al., Citation2015; Ratcliffe, Citation2012), and it is possible that cask 2 and others from this shipwreck contained that beverage. Another possible indication of contents may be inferred from the presence or absence of sapwood in the staves. A watertight ‘wet cooperage’ cask required more processing of staves to ensure a tighter fit than a ‘dry cooperage’ cask intended for transport of dry goods. Wet cooperage typically required removal of the sapwood, while dry cooperage did not (Daalen, Citation2021; Staniforth, Citation1987). The staves from the Gribshunden casks with square bungs have little to no sapwood compared to the casks without square bungs. Among the 15 staves of cask 2, two staves retain sapwood, but only two and three sapwood rings. In comparison, more than half the staves of cask 1 and cask 3 have sapwood, with as many as 12 sapwood rings. We speculate that cask 2 possibly contained beer, while casks 1 and 3 might have contained dry goods, though no remains of those products were apparent at the time of excavation.

Conclusions

The dendrochronological studies performed on the cask staves and heads from Gribshunden show that the cask timber was sourced from several different regions across Northern Europe, manifesting the extent of the European timber trade during the late medieval period. The different source areas indicate that the timber for staves was a bulk good and transported to wherever coopers needed it, in this case most likely inside the Danish kingdom. The timber source areas shifted through the medieval period in response to forest depletion. Furthermore, this study indicates barrels typically had a short working life of just a few years or less; this knowledge may aid in establishing the sinking dates of unknown wrecks to within a short span. Lastly, this study shows the untapped potential in wooden casks and the scientific gain possible for historical, archaeological, and other fields.

Author Contributions

Study design: All authors. Fieldwork: Brendan Foley. Dendrochronological analysis: Anton Hansson & Hans Linderson. Data interpretation: All authors. Manuscript writing: Anton Hansson & Brendan Foley. Comments on the manuscript: Hans Linderson.

Permissions Statement

This research was conducted under permits issued to Blekinge Museum by Länsstyrelsen i Blekinge [nr 431-4791-20 and nr 431-1299-2021].

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (46.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Blekinge Museum director Marcus Sandekjer and curator Christoffer Sandahl for their collegial collaboration, Tomasz Wazny for his kind help with specifying the dendro-provenancing of the Baltic timber, Staffan von Arbin for his edifying comments on the draft of this manuscript and for information on the Skaftö Wreck's cask components, and Jeroen Oosterbaan for insights into casks in the Netherlands. We acknowledge Lars Einarsson, Kalmar Läns Museum, for his previous investigations on the Gribshunden shipwreck.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Cask studies from a few post-medieval (after 1520) Baltic contexts have been published or are in preparation, including the Osmund Wreck (after 1553), Vasa (1628), and Lindormen (1644). Beyond the Baltic, cask studies are more common, with notable examples including Mary Rose (1545) (Marsden, Citation2003), the Red Bay Basque whaler (1565) (Loewen, Citation1999), William Salthouse (1841) (Staniforth, Citation1987), and others.

References

- Adams, J., & Rönnby, J. (2022). The Danish Griffin: The wreck of an early modern royal carvel from 1495. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572414.2022.2068803

- Baillie, M. G. L., & Pilcher, J. R. (1973). A simple crossdating program for tree-ring research. Tree-ring Bulletin, 33, 7–14.

- Bevan, A. (2014). Mediterranean containerization. Current Anthropology, 55(4), 387–418. https://doi.org/10.1086/677034

- Bridge, M. (2012). Locating the origins of wood resources: A review of dendroprovenancing. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(8), 2828–2834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.028

- Crone, A., & Fawcett, R. (1998). Dendrochronology, documents and the timber trade: New evidence for the building history of Stirling Castle, Scotland. Medieval Archaeology, 42(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00766097.1998.11735618

- Daalen, S. V. (2021). Can we estimate felling intervals for barrels without sapwood? International Journal of Wood Culture, 1(1-3), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1163/27723194-20210010

- Daly, A. (2007). Timber, trade and tree-rings. A dendrochronological analysis of structural oak timber in Northern Europe, c. AD 1000 to c. AD 1650. (Doctoral Thesis) University of Southern Denmark.

- Daly, A. (2011). Dendro-geography, Mapping the Northern European historic timber trade. In P. Fraiture (Ed.), Tree rings, art, archaeology (pp. 107–123). Scientia Artis 7.

- Daly, A., & Tyers, I. (2022). The sources of Baltic oak. Journal of Archaeological Science, 139, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2022.105550

- Dijkman, J. (2011). Shaping medieval markets: The organisation of commodity markets in Holland, c. 1200 - c. 1450. Brill.

- Domínguez-Delmás, M., Nayling, N., Ważny, T., Loureiro, V., & Lavier, C. (2013). Dendrochronological dating and provenancing of timbers from the Arade 1 shipwreck, Portugal. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 42(1), 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-9270.2012.00361.x

- Einarsson, L. (2012). Rapport om hydroakustisk kartering och kompletterande dendrokronologisk provtagning och analys av vraket vid St Ekö, Kalmar. Kalmar läns museum.

- Einarsson, L., & Wallbom, B. (2001). Marinarkeologisk besiktning och provtagning för datering av ett fartygsvrak beläget i farvattnen syd Saxemara, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län. Kalmar läns museum.

- Einarsson, L., & Wallbom, B. (2002). Fortsatta marinarkeologiska undersökningar av ett fartygsvrak beläget vid St. Ekö, Ronneby kommun, Blekinge län, Kalmar. Kalmar läns museum.

- Eriksson, N. (2015). Skeppsarkeologisk analys. In J. Rönnby (Ed.), Gribshunden (1495). Skeppsvrak vid Stora Ekön, Ronneby, Blekinge. Marinarkeologiska undersökningar 2013–2015. Blekinge museum rapport 21 (pp. 13–32). Blekinge museum/Södertörns högskola.

- Eriksson, N. (2020). Figureheads and symbolism between the medieval and the modern: The ship Griffin or Gribshunden, one of the last Sea Serpents? The Mariner’s Mirror, 106(3), 263–276. http://doi.org/10.1080/00253359.2020.1778300

- Etting, V. (2004). Queen Margrete I (1353–1412) and the founding of the Nordic Union. Brill.

- Etting, V., Straetkvern, K., & Gregory, D. (2019). Gribshunden – om vraget af kong Hans’ krigsskib i Blekinges skaergärd. In P. K. Madsen & I. Wass (Eds.), Nationalmuseets Arbejbsmark 2019 (pp. 102–113). Nationalmuseet.

- Haneca, K., Katarina, Č, & Beeckman, H. (2009). Oaks, tree-rings and wooden cultural heritage: A review of the main characteristics and applications of oak dendrochronology in Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.07.005

- Hansson, A., Linderson, H., & Foley, B. (2021). The Danish royal flagship Gribshunden – Dendrochronology on a late medieval carvel sunk in the Baltic Sea. Dendrochronologia, 68, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2021.125861

- Hillam, J., & Tyers, I. (1995). Reliability and repeatability in dendrochronological analysis: Tests using the Fletcher archive of panel-painting data. Archaeometry, 37(2), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1995.tb00752.x

- Holmes, R. L. (1983). Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring data and measurement. Tree-ring Bulletin, 43, 69–78.

- Horgan, J. (2013). The fifth element. Irish Pages, 7(2), 176–186. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43863814

- Hyttel, F., Majchczack, B., Dencker, J., & Segschneider, M. (2015). The excavations on the wreck of Lindormen. Archäologisches Landesamt Schleswig-Holstein.

- Ingvardson, G., Muter, D., & Foley, P. B. (2022). Purse of medieval silver coins from royal shipwreck revealed by X-ray microscale computed tomography (µCT) scanning. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 43, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103468

- Jahnke, C. (2009). The European Fishmonger: The great herring fishery in the Øresund c.1200–1600. Publications from the National Museum. Studies in Archaeology & History, 9, 34–47.

- Johnson, T. (2015). Medieval law and materiality: Shipwrecks, finders, and property on the Suffolk Coast, ca. 1380–1410. The American Historical Review, 120(2), 407–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/120.2.407

- Kadens, E. (2019). Cheating pays. Columbia Law Review, 119(2), 527–590.

- Lane, F. C. (1964). Tonnages, medieval and modern. The Economic History Review, 17(2), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/2593003

- Loewen, B. (1999). Les barriques de Red Bay et l’espace atlantique septentrional, vers 1565. Département d’histoire, Université Laval.

- Loewen, B. (2007). Casks from the 24M Wreck. In R. Grenier, M.-A. Bernier, & W. Stevens (Eds.), The underwater archaeology of Red Bay: Basque shipbuilding and whaling in the 16th century (pp. 5–46). Parks Canada.

- Macheridis, S., Hansson, M. C., & Foley, B. P. (2020). Fish in a barrel: Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) from the Baltic Sea wreck of the royal Danish flagship Gribshunden (1495). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 33, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102480

- Marsden, P. (2003). Sealed by time: The loss and recovery of the Mary Rose. Mary Rose Trust.

- Meskens, A., Bonte, G., De Groot, J., De Jonghe, M., & King, D. A. (1999). Wine-Gauging at Damme: The evidence of a late medieval manuscript. Histoire & Mesure, 14(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.3406/hism.1999.1501

- Nilsson, T. (1987). Tunnan - containerns föregångare. In A. W. Mårtensson (Ed.), Kulturen 1987 (pp. 40–54). Kulturen i Lund.

- Oppenheim, M. E. (1896). Naval accounts and inventories of the reign of Henry VII 1485-8 and 1495-7. Publications of the Navy Records Society Vol. VIII.

- Ossowski, W. (Ed.). 2014). The Copper Ship. A medieval shipwreck and its cargo. National Maritime Museum in Gdańsk.

- Pilcher, J. R. (1990). Sample preparation, cross-dating and measurement. In E. R. Cook & L. A. Kairiukstis (Eds.), Methods of dendrochronology: Applications in the environmental sciences (pp. 40–51). Kluwer Academic Publishers Group.

- Ratcliffe, J. E. (2012). The casks from Vasa. (Master's Thesis). East Carolina University.

- Rinn, F. (2003). TSAPWin user reference.

- Robben, F. (2008). Spätmittelalterliche Fässer als Transportverpackung im hansischen Handelssystem. Archäologische Informationen, 31(1&2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2008.1&2.11118

- Schweingruber, F. H. (1988). Tree rings – basics and applications of dendrochronology. Kluwer Academic Publishers Group.

- Schweingruber, F. H. (1996). Tree rings and environment: Dendroecology. Haupt.

- Söderlind, U. (2006). Skrovmål. Kosthållning och matlagning i den svenska flottan från 1500-tal till 1700-tal. Stockholms universitet.

- Sohar, K., Vitas, A., & Läänelaid, A. (2012). Sapwood estimates of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) in eastern Baltic. Dendrochronologia, 30(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2011.08.001

- Staniforth, M. (1987). The casks from the wreck of the “William Salthouse”. Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology, 5(1), 21–28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29543180

- Svenwall, N. (1994). Ett 1500-talsfartyg med arbetsnamnet Ringaren. Stockholms universitet.

- Vitas, A. (2020). Medieval oak chronology from Klaipėda, Lithuania. Dendrochronologia, 64, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125760

- Von Arbin, S. (2014). Skaftövraket – ett senmedeltida handelsfartyg. Bohusläns museum Rapport 2014:11. Bohusläns museum.

- Von Arbin, S., Skowronek, T., Daly, A., Brorsson, T., Isaksson, S., & Seir, S. (2022). Tracing trade routes: Examining the cargo of the 15th-century Skaftö Wreck. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572414.2022.2076518

- Waelput, E. (2004). Eer het van in duigen valt. Basistechnieken van het ambachtelijk kuipen. Garant Uitgevers.

- Wegen, C. F., Plesner, C. U. A., Becker, T. A., & Garde, H. G. (1864). Danske magazin ser. 4 vol. 1. Det Kongelige Danske Selskab for Faedrelandets Historie og Sprog.

- Wazny, T. (1990). Aufbau und Anwendung der Dendrochronologie für Eichenholz in Polen [doctoral thesis]. University of Hamburg.

- Wazny, T. (2002). Baltic timber in Western Europe – An exciting dendrochronological question. Dendrochronologia, 20(3), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1078/1125-7865-00024

- Wazny, T. (2005). The origin, assortments and transport of Baltic timber. In C. Van De Velde, H. Beeckman, J. Van Acker, & F. Verhaeghe (Eds.), Constructing wooden images (pp. 115–126). University Press.

- Witthöft, H. (1979). Umrisse einer historischen Metrologie zum Nutzen der wirtschafts- und sozialgeschichtlichen Forschung : Maß und Gewicht in Stadt und Land Lüneburg, im Hanseraum und im Kurfürstentum/Königreich Hannover vom 13. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Zupko, R. E. (1968). A dictionary of English weights and measures from Anglo-Saxon times to the nineteenth century. University of Wisconsin Press.