ABSTRACT

Trauma infiltrates all of society – including museums. For guests, the trauma may lie in the context of the visit or what they bring with them from their everyday lives. Staff can develop trauma through daily interaction with stressful content or secondary trauma through interaction with traumatized guests. During the COVID19 pandemic, trauma also developed from workplace issues regarding personal health safety and job security. This is a case study about how one museum educated itself about the presence and impact of trauma through exploration of a framework developed by the Trauma Responsive Educational Practices (TREP) Project. We present results of a staff-wide evaluation around initial implementation of the framework. Results show staff found the framework to be relevant and useful, but they need more support adapting it to the unique environment of museums. It also triggered memories of personal trauma in some staff, requiring a rethinking about how to implement it.

Why museums should (and do) care about trauma

Trauma is not the first word that comes to mind when thinking about museums. Museums are often considered places to escape from life stressors, not as sources or vessels of stress. But trauma has a home in museums just as it does in other spheres of life. For guests, the trauma may lie in the visit's context (ex: visiting a Holocaust museum or having an aspect of their personal history triggered by an experience). Staff too, can develop trauma through daily interaction with psychologically stressful themes. They can also experience secondary trauma through interaction with traumatized guests. And, during times such as the COVID19 pandemic, critical workplace issues regarding personal safety and job security can be intense and chronic enough to become traumatic.

Trauma occurs when the psychological distress caused by a deeply disturbing or chronically stressful event overwhelms one’s ability to cope.Footnote1 Sources of trauma can be acute (sudden loss of a primary caregiver, a natural disaster, etc.) or chronic (ongoing community strife, historical and systemic racism, etc.). In museums, the effects of trauma can impact guest engagement and learning. It also manifests in staff stress levels causing long-term effects if left untreated. The pandemic has made the issue urgent, but many less urgent but nevertheless persistent and powerful sources of trauma predate it.

Educators and researchers have been studying trauma in the classroom for decades.Footnote2 Recently, a team of educators, counselors, researchers and neuroscientists developed a framework for addressing trauma in schools – Trauma Responsive Educational Practices (TREP) Project.Footnote3 Rooted in the neurobiology of how trauma affects the brain and behavior, TREP addresses how to set up a trauma-responsive learning environment and pedagogy, teaches how to identify and support youth coping with trauma and how to support the educators in their own trauma.

In the wake of the pandemic, the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago (MSI) implemented a wide-scale TREP training initiative for education staff to prepare for re-opening after the spring/summer 2020 shutdown. This paper describes the project as a case study to explore trauma-responsive practices at the institutional, group, and personal levels. How can a framework designed for formal classrooms be impactful in museums? To help answer the question, we also report on an evaluation of staff response to the initiative. Finally, we hope sharing our experience will spark collaboration with other institutions interested in exploring this framework.

Studies on trauma in museums tend to focus on institutions that memorialize moments of a catastrophe or are located at disaster sites.Footnote4 These studies explore how curatorial and exhibition choices evoke empathy or trigger distress in the visitor through cultural memory or “mobilizing visitors” imaginations throughout the exhibit.Footnote5 Some go further and discuss the larger social ramifications of such experiences.Footnote6 We know that trauma is caused by many things other than disasters, and that trauma from life outside of museums is carried by guests and staff. So museums of all types should be interested in how attending to trauma has implications for their work.Footnote7

Less common is research on how museum staff are affected by trauma in the work environment, either by constant interaction with emotionally sensitive collections,Footnote8 or through community engagement and discussion of difficult topics.Footnote9 Understanding the adverse effects of long-term stress on staff and visitors benefits both groups' psychological wellbeing,Footnote10 preventing “burnout” in staff,Footnote11 while supporting the common museum goal of creating a welcoming, empathic environment for visitors.Footnote12 The care we take for the communities we welcome into the museum should reflect the care we take for the community within. Organizational culture can offer some support to counter secondary traumatic stress or vicarious trauma,Footnote13 which is where frameworks like TREP may be useful.

Most approaches to trauma-informed education are designed for formal school classrooms and are less applicable to interactions with one-time visitors. However, there are trauma-informed practices that can support staff in identifying and responding to signs of trauma among museum guests. For example, learning how to identify and respond to children who show possible trauma-related reactions to sudden loud noises, crowded spaces, etc. Also, many museums do have long-term programming with guests that can benefit from trauma-informed relationship-building strategies such as mentoring and mindfulness practice (ex: many museums have after school and summer programs where adolescent youth participation that spans many months or years).

Our museum

Located on the South Side of Chicago, MSI is part of an incredible community of over 30 neighborhoods rich in artistic, community and cultural pride. The South Side also suffers from ongoing segregation stemming from historical racism.Footnote14 Resulting from this segregation are issues associated with lower socioeconomic status such as access to healthcare, healthy food sources, police involvement, housing instability and other issues.

In 2019, 1.3 million guests visited our museum. As with many science museums, our non-group affiliated guests overall reflect the more affluent segment of the local community.Footnote15 However, much of our programming extends beyond traditional audiences. For example, about 338,000 students visited on educational field trips. According to their teachers, about 84% of the schools serve lower to middle-income communities. Whether it be through school field trips, our adolescent development program or the programs we run at libraries and park districts – we serve many youths who have histories of traumatic experiences.

Even for visitors with minimal exposure to trauma, the nature of some of our exhibits could themselves be a traumatic experience. An example is MedLab, where students in field trip groups diagnose a human patient simulator that is programmed to experience various ailments – including diabetes, heart disease and asthma. It is almost a certainty that some students will come to the experience having witnessed these symptoms in real life (ex: a family member experiencing an asthma attack); thereby increasing the potential for triggering a traumatic reaction. Thus, when MedLab was launched staff were trained by a psychologist to look for signs of trauma and stress among guests and how to intervene appropriately.

Another way that visiting the museum could become a potentially traumatic event is by emitting sounds, smells and images that trigger memories of personally traumatic events that are completely unrelated to the exhibit. During a discussion of past experiences, staff who work on the museum floor described instances around our tesla coil, which fires loudly every half-hour. Not often, but occasionally some youths would freeze and become less engaged afterward. TREP provided the training needed to recognize this as a possible sign of trauma and gave us tools to appropriately keep the youth engaged in the learning experience instead of ignoring them. Finally, we have also had the terrible experience of having children of staff and participants in our youth programs fall victim to gun violence in the community. To each event, MSI responded by acknowledging the stress it was creating on staff and offering supports like time off, professional help, group discussions, etc. However, TREP training opened our eyes to the need to build trauma-responsive systems and culture into the museum consistently as opposed to only calling upon them in response to individual events. We need to engage in collective care and support to manage the emotional effects of the loss. By having the structure and training already in place, we can become better prepared to respond effectively.

Trauma responsive educational practices

The Trauma Responsive Educational Practices Project was founded by Dr. Micere Keels, Associate Professor, Department of Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago. It started in 2016 as a policy brief on the educational consequences of the chronic toxic stress of living in high poverty, high crime communities.Footnote16 It has since expanded into a significant project to develop the individual and organizational capacity of educators and schools serving children growing up in neighborhoods with high levels of toxic stress, such as violent crime, focused poverty, concentrated foster care involvement, and housing instability. Most of the project’s work is with schools and other formal educational environments, but Dr. Keels and her team have recently begun working with informal educational settings such as community centers, hospitals and now museums.

The TREP Project focuses on building the capacity of educators to compassionately understand where youth are coming from and meeting them where they are at. Because traumatized children often exhibit dysregulated behaviors, adult reactions often become focused on discipline, behavior control and result in exclusion from instruction. This scenario happens just as commonly in museum settings as in schools. Children may be asked to leave a field trip experience or theater show when perceived as disruptive and defiant. Staff may ignore their questions and close exhibit spaces early to avoid working with youth displaying behavior that makes that staff member uncomfortable.Footnote17

TREP helps educators identify the signs of trauma, use evidence-based practices to support healthy coping of those students, and prioritize creating spaces and processes that keep children in the classroom and engaged in learning. TREP is not a one-size-fits-all approach or recipe to be followed. Instead, it is a framework that educators can use to attend to students’ (and their own) physical, psychological and emotional safety. Those three domains are supported by the building of healthy relationships and using mindfulness practices to build children’s self-regulation skills.

The TREP framework is based on scientific research in education, psychology, human development and neurobiology. For example, the importance of mindfulness is grounded in a diverse corpus of research showing the impact of mindfulness on the brain.Footnote18 Also, research into neurobiological dysregulation (stress-induced impairment of the brain and body) shows how trauma can manifest itself very differently between people. For example, some may experience hyperarousal (inability to remain seated, outbursts, excessive startled responses) or hypoarousal (daydreaming, forgetfulness, lack of motivation). Science, and the experience of educators and counselors on the TREP team, underlies the framework.

The TREP Project has a range of asynchronous training programs available on their website, while others are conducted over a series of days via facilitated Zoom sessions (www.trepeducator.org). The website also has an informative TREP magazine and a professional learning community. In Summer, 2020 they also hosted a school mental health virtual conference. Briefs and video recordings of the sessions are available on their website.

We have focused our initial TREP implementation on aspects that do not require long-term engagement with guests – such as supporting staff with their own well being. And learning how to recognize and respond to more immediate signs of a traumatic stress response among guests.

Museums such as ours that also engage in longer-term, sometimes multiyear, youth development programming and summer internships can also implement the aspects of TREP that require sustained engagement and relationship building. For example, mindfulness meditation generally requires training, practice and works best as part of an ongoing regime. These components will be particularly important for diversity initiatives that focus on youth from racially, ethnically, and economically marginalized communities who also have a higher likelihood of exposure to traumatic life events. During the pandemic-induced pause in in-person programming, we have the opportunity to strategically rethink those programs. Making them all trauma-responsive became a priority.

Introducing TREP to a museum like ours

Museum staff were introduced to TREP about a year before the pandemic. At the time, we identified it as a long-term priority of the education division given our engagement in focused outreach to schools and communities experiencing chronic stress due to racism, poverty, segregation, violent crime, recent school closings (in Chicago), etc. When our physical building shut down for the pandemic, our education leadership team recognized that everyone was now experiencing trauma collectively, albeit in layered ways unique to each individual’s life experience. Staff were affected by the impact of COVID-19 on the health of their immediate and extended families, by concerns about the financial and workforce uncertainty faced by museums worldwide along with the broader economic fallout on friends, family and community. As we moved closer to re-opening there were intense stressors regarding staff health and safety. We also needed to assume that any given guest was also coping with family illness or loss, loss of employment, social isolation, etc. On top of that, civil strife sparked by the murder of George Floyd and the systematic and ongoing violence and disenfranchisement toward of Black and African Americans added additional layers of trauma to both staff and guests.

Shortly after the pandemic-induced closure, MSI formed a cross-departmental working group to investigate TREP and social-emotional learning (SEL) as part of preparing for returning to work and re-opening the museum. The group began by looking into the literature around museum trauma and SEL. Each member completed the Understanding Trauma and Trauma-Related Educational Practices self-guided course offered by the TREP Project.Footnote19 After the working group finished the training, a recommendation was made to extend the training to all staff. While everyone at the Museum was invited to take the training, staff in the education division were formally instructed by division leadership to complete it. They were given approximately three months to complete the training and allowed to take as much staff time as needed to do so. However, there was no request for documentation of completion nor consequences for those who did not. At the end of the period, we conducted an anonymous staff survey to measure the completion rate and obtain feedback.

The course itself consisted of four modules. The first was about how to identify trauma in students. The second was on the role of educators in helping students cope with trauma. Then there was a mindfulness break. The third lesson was about the neurobiology of trauma and how it shows up in behavior. The last module was about strategies for universal precautions in the classroom. As it is self-paced, the time needed to do the training varies. Our staff reported spending an average of 11 h on it.

Staff responses to TREP training

To get staff feedback, we e-mailed a survey to about 70 staff in the education division and posted to museum-wide staff communication channels to reach non-education staff (internal e-mail newsletters, Slack channels, etc.). In the end, we had 79 responses to the survey. Of them, 47% reported they completed the TREP training, 26% started it but did not complete it and 27% had not started it. Although our sample size is small, we found no statistically significant differences in our questions between genders or race/ethnic identity groups.Footnote20

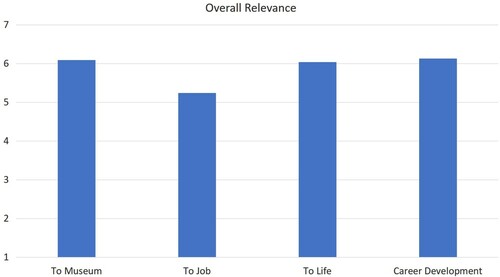

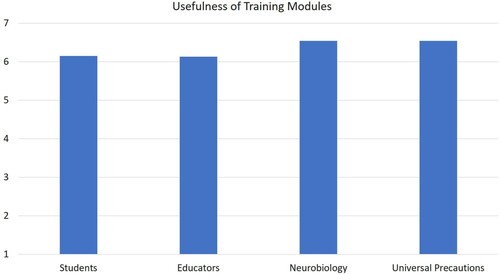

Staff who participated in the training reported very high levels of usefulness (). There was no significant difference between the four modules, with average scores from 6 to 6.2 per module. Only one person rated any of the modules as less than “neutral.” Scores were also high on relevance to their work, applicability to work, applicability to life as a whole, and it being a worthwhile investment for career development (). Of the 20 who identified as other staff managers, 12 said they had subsequently talked to their teams about trauma.

Figure 1. Mean staff ratings (1 = Not Useful, 7 = Very Useful) of overall TREP training experience.

Figure 2. Mean staff ratings (1 = Not Relevant, 7 = Very Relevant) of overall TREP training experience.

Despite the strong reactions overall, there were some critiques and recommendations. The most powerful was a staff member who had past traumatic memories triggered by the training. That same person rated the training highly and essential for the museum but had to stop participation for their mental well being. Another person said they were exhausted from hearing about trauma because they see and live it in their daily life. Such feedback made it clear that we need to consider prior staff trauma when designing these activities. It was a significant learning opportunity for the authors and the working group about applying TREP practices to our own research work. Otherwise, the most common critique was that the training’s focus on formal learning settings (discussed below).

Of the 18 who did not take the training, they rated the topic's usefulness to their job as an average of 4.6 (on the same 7-pt scale), about 1.5 pts lower than those who did participate (though still in the higher end of the scale). But they still showed interest in it, 48% said they would likely complete it if given more time.

What does trauma mean to you?

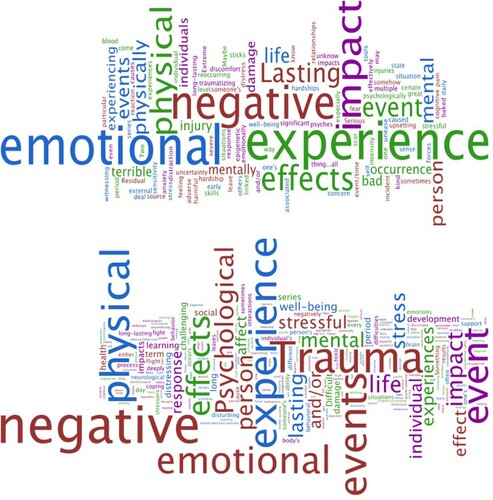

There are some interesting differences in how staff define trauma based on whether they participated in the training or not (). On the survey, we asked, “What does the word ‘trauma' mean to you?” in an open-ended format. Those who did not take the training were more likely to mention emotions and the effects of trauma. Those who started the training were more likely to reference an association with specific events and describe physiological reactions to trauma. This may reflect the TREP focus on the neurobiology of trauma, something the layperson often does not think about when considering trauma. We think this is important because it addresses misconceptions that trauma is a purely emotional response. Both those who did or did not participate in the training were equally likely to mention trauma as being associated with negative experiences and emotions. Overall, this reflects how the training shifted the concept of trauma and operationalized it for participants. Those who took the training were more likely to consider the triggers of trauma and its biological impact on the body and mind.

Figure 3. Word cloud of responses to “What does the word ‘trauma’ mean to you?” by staff who did not start the training (top) and those who did (bottom).

When asked to give examples about how the training can be applied to their jobs, the responses were mostly about guest behavior. For example, one staff member said it brought

Awareness that what I previously thought of as misbehavior, withdrawal, or anti-social is often a result of trauma. Creating safe spaces and time for students to express themselves when they are ready should continue to be a core goal of our student programs.

However, about 31% of those who took the training left this answer blank or wrote a version of “I don't know,” suggesting trouble articulating a direct answer. When asked about what aspects they would like more training on, staff generally spoke about more specific strategies for responding to signs of trauma and managing time needed to learn and implement the new strategies.

When asked about potential barriers to implementation, by far the most significant staff response was around the lack of sustained engagement time with guests. Many of the TREP recommendations require relationship building with youth. While it is not always possible with one-time guests, long-term programming with youth is common in museums and growing in popularity.Footnote21 Other common barriers included the institutionalized support that will be needed to keep the TREP framework front and center and also lack of knowledge about the backgrounds of our guests.

Next steps and recommendations

The most important next step for our working group is to further interpret and operationalize the TREP framework for informal settings. The main theme of the survey responses was that the training is valuable, practical and of high quality. However, staff need more help about how to apply it. For example, a method of considering how guests may engage with and be triggered by exhibits, formalized procedures for recognizing and supporting the needs of short- and long-term guests who may be experiencing a traumatic stress response, and institutionalizing collective-care practices that maximizes the wellbeing of staff. Within education, we have just begun to integrate our learnings about and experience with the TREP framework into our operations and practice. We now consistently try to find ways to prioritize and include TREP training into the narrative and budget of funding applications to support the museum’s programming. We also have recommended ways for museum senior leadership across all divisions to learn about TREP and consider its role across the institution.

The training did an excellent job of educating staff on the basics of what trauma is and the role it plays in learning. But most of the suggested interventions require more sustained engagement with guests than are possible at museums. Work is needed to develop TREP strategies of a just-in-time, operational nature. The working group plans to develop this further through investigation of the literature, involvement of professional consultants (both within and outside of the TREP Project) and engagement with staff (surveys, focus groups, etc.). We are happy to work cross-institutionally with anyone similarly interested.

At an institutional level, we believe almost every museum could benefit from an introduction to the TREP framework. Trauma is not limited to any geographic location, community group or museum type. The COVID-19 pandemic and its health and economic consequences make it even more critical to consider the psychological and emotional well-being of guests. Funding is always a consideration in nonprofit settings, so we recommend writing trauma awareness training into grant applications and other fundraising opportunities. At the group level, it’s essential to find the appropriate training for the specific museum context. The TREP Project is routinely updating and creating new training programs on their website with a wide variety of content. At the individual level, we recommend starting by spending some time at that site. In addition to background literature, the site offers a professional learning community full of targeted techniques and resources and monthly e-magazines full of practitioners’ tips. Initiatives like this often live and die at the grassroots level, so staff educating and supporting themselves in pursuing this work is critical.

Overall, we found TREP changed how we thought about trauma. It evolved from being an issue primarily considered as being outside of the museum's walls to one that impacts everything we do – including both guests and staff. We learned ways to identify and respond to signs of trauma and began to think about trauma as more than an emotional reaction but also one deeply rooted in human biology as well. Being trauma-informed is an invitation. This start was our acceptance of the invitation, now we need to show up.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge support and inspiration from Carla Bruton, Aaron Anderson, Anjylla Foster, Moïse-Denis Jean, Ronald Martin and Mitch Rodriguez. We also thank Margy LaFreniere for introducing us to the TREP framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

C. Aaron Price

C. Aaron Price, Ph.D. is the Director of Research and Evaluation at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.

Leila Makdisi

Leila Makdisi, M.A. is an Education Coordinator of Student Experiences at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.

Gail Hutchison

Gail J. Hutchison, M.M. is a Senior Educator of Out of School Time Programs at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.

Daniel Lancaster

Daniel Lancaster was a Senior Coordinator of Guest Experiences at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago. He now lives in Cincinnati, OH.

Micere Keels

Micere Keels, Ph.D. is Associate Professor, Department of Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago.

Notes

1 Onderko, “What is Trauma?”, https://integratedlistening.com/what-is-trauma/.

2 Martin et al., “Incorporating Trauma-informed Care,” 958; McInerney and McKlindon, “Unlocking the Door to Learning,” 1.

3 Trauma Responsive Educational Practices Project, https://www.trepeducator.org/.

4 Rauch, “A Balancing Act,” 6; Bendigan, “Developing Emotions: Perceptions of Emotional Responses in Museum Visitors,” 87.

5 Fields, “Narratives of Peace and Progress,” 62; Mason et al., “Experiencing Mixed Emotions in the Museums,” 125.

6 Sodaro, “Memorial Museums,” 162; Viloi, “Trauma Site Museums and Politics of Memory,” 36; Zalut, “Interpreting Trauma, Memory, and Lived Experience,” 4.

7 Brown, “Trauma, Museums and the Future of Pedagogy,” 250.

8 McCarroll, Blank and Hill, “Working with Traumatic Material,” 66.

9 Munro, “Doing Emotional Work in Museums,” 44.

10 Katrikh, “Creating Safe(r) Spaces,” 7–15.

11 Munro, “Doing Emotional Work in Museums,” 47; Svgdik, “If This Was Just a Museum,” 30.

12 Andermann and Arnold de-Simine, “Museums and the Educational Turn,” 1.

13 Munro, “Doing Emotional Work in Museums,” 50.

14 Moore, The South Side, 2.

15 DeWitt and Archer, “Participation in Informal Science Learning Experiences,” 356.

16 Keels, “A Whole School Approach.”

17 Dawson, “Not Designed for Us,” 981.

18 Young, “The Impact of Mindfulness-based Interventions,” 424; Querstret, “Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Health and Well-being in Nonclinical Samples.”

19 Usually costing $45, it was offered for free to the public during the Summer of 2020.

20 Staff who responded to the survey self-identified as 69% female, 27% male, 2% nonbinary, and 2% did not reply. For race and ethnic identity, they self-identified as 67% White, 13% Hispanic/Latino or Spanish origin, 9% African American, 6% Asian and 2% Native American or Alaska Native and Middle Eastern or North African.

21 Chi, Dorph, and Reisman, “Evidence & Impact”; Shelnut, “Long-term Museum Programs for Youth,” 10.

Bibliography

- Andermann, Jans, and Silke Arnold de-Simine. “Museums and the Educational Turn: History, Memory, Inclusivity.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 4, no. 2 (2012): 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2012.040201.

- Bendigan, Kirsten M. “Developing Emotions: Perceptions of Emotional Responses in Museum Visitors.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 16, no. 5 (2016): 87–95.

- Brown, Timothy P. “Trauma, Museums and the Future of Pedagogy.” Third Text 18, no. 4 (2004): 247–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0952882042000229854.

- Chi, B., R. Dorph, and L. Reisman. Evidence & Impact: Museum-Managed STEM Programs in out-of-School Settings. National Research Council Committee on Out-of-School Time STEM. Washington, DC: National Research Council, 2015.

- Dawson, Emily. “Not Designed for us': How Science Museums and Science Centers Socially Exclude low-Income, Minority Ethnic Groups.” Science Education 98, no. 6 (2014): 981–1008.

- DeWitt, Jennifer, and Louise Archer. “Participation in Informal Science Learning Experiences: The Rich Get Richer?” International Journal of Science Education Part B 7, no. 4 (2017): 356–373.

- Fields, Alison. “Narratives of Peace and Progress: Atomic Museums in Japan and New Mexico.” American Studies 54, no. 1 (2015): 53–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24589487.

- Katrikh, M. “Creating Safe(r) Spaces for Visitors and Staff in Museum Programs.” Journal of Museum Education 43, no. 1 (2018): 7–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2017.1410673.

- Keels, Micere. “A Whole School Approach to Improving the Outcomes of Children Living in High Crime Communities.” Accessed December 28, 2020. https://5ef1df80-84a7-49be-a188-dc2a261bb9d5.filesusr.com/ugd/fc6e9a_f5a961c5e6304ba5b88d64987104ae1e.pdf.

- Martin, Sandra L., Olivia Silber Ashley, LeBretia White, Sarah Axelson, Marc Clark, and Barri Burrus. “Incorporating Trauma-Informed Care Into School-Based Programs.” Journal of School Health 87, no. 12 (2017): 958–967.

- Mason, Rhiannon, Areti Galani, Katherine Lloyd, and Joanne Sayner. “Experiencing Mixed Emotions in the Museums: Empathy, Affect and Memory in Visitors’ Responses to Histories of Migration.” In Emotion, Affective Practices and the Past in the Present, edited by Laurajane Smith, Margaret Wetherell, and Gary Campbell, 121–146. London: Rutledge, 2018.

- McCarroll, J. E., A. S. Blank, and K. Hill. “Working with Traumatic Material: Effects on Holocaust Memorial Museum Staff.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65, no. 1 (1995): 66–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079595.

- McInerney, Maura, and Amy McKlindon. “Unlocking the Door to Learning: Trauma-Informed Classrooms & Transformational Schools.” Education Law Center (2014): 1–24.

- Moore, N. Y. The South Side. New York: Picador, 2016.

- Munro, Ealasaid. “Doing Emotional Work in Museums: Reconceptualizing the Role of Community Engagement Practitioners.” Museum and Society 12, no. 1 (2014): 44–60. https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/view/246.

- Onderko, Karen. “What is Trauma?” Accessed December 28, 2020. https://integratedlistening.com/what-is-trauma.

- Querstret, Dawn, Linda Morison, Sophie Dickinson, Mark Cropley, and Mary John. “Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Health and Wellbeing in Nonclinical Samples: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Stress Management (In press).

- Rauch, N. “A Balancing act: Interpreting Tragedy at the 9/11 Memorial Museum. Journal of Museum Education.” Interpreting Trauma, Memory, and Lived Experience in Museums and Historic Sites 43, no. 1 (2018): 6–21.

- Shelnut, S. L. “Long-term Museum Programs for Youth.” Journal of Museum Education 19, no. 3 (1994): 10–13.

- Sodaro, Amy. “Memorial Museums: Promises and Limits.” In Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Mueums and the Politics of Past Violence. Rutgers University Press, 162–184. 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1v2xskk.11.

- Svgdik, Dorothy. “If This Was Just a Museum: Employee Emotional Wellbeing at Trauma Site Museums. “ MA Thesis, University of Washington, 2019.

- Viloi, Patrizia. “Trauma Site Museums and Politics of Memory: Tuol Sleng, Villa Grimaldi and the Bologna Ustica Museum.” Theory, Culture and Society 29, no. 1 (2012): 36–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276411423035.

- Young, Katherine S., Anne Maj van der Velden, Michelle G. Craske, Karen Johanne Pallesen, Lone Fjorback, Andreas Roepstorff, and Christine E. Parsons. “The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Brain Activity: A Systematic Review of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 84 (2018): 424–433.

- Zalut, Lauren. “Interpreting Trauma, Memory, and Lived Experience in Museums and Historic Sites.” Journal of Museum Education 43, no. 1 (2018): 4–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2017.1419412.