ABSTRACT

In this essay, we explore ways in which cultural and museum spaces can be opened up to meaningful discussions about difficult topics and how this can be done through specific educational formats. We attempt to look critically at some of the assumptions that are around in critical museum education theory and practices, e.g. influences coming from standpoint theory. The goal is to understand our own unconscious biases as we develop methods to help address problematic issues such as racism and anti-Semitism. We argue that these biases are shaped by a logic of dichotomy that allows to position oneself on “the good side.” Especially in an atmosphere of scandalization, these dichotomies might hinder mutual learning situations. We propose using Michael Rothberg’s concept of the “implicated subject” to develop approaches and methods that move beyond dichotomous thinking patterns. We will try to illustrate our reflection process with three examples that also show that taking (one’s own) implication seriously has unsettling effects that can stall the development of methods that seek to open spaces also for conflictual discussions.

Introduction

In this essay, we explore ways in which museum spaces can be opened up to meaningful discussions about difficult topics and how this can be done through specific educational formats. We report on attempts, circular thoughts, and uncertainties. We write this text from the perspective of educators working both in art spaces and contexts where issues of historiography and memory politics are addressed. Both together and individually we develop methods to facilitate meaningful encounters and conversations in museums, exhibitions, and public space for diverse audiences of all ages. Andrea Hubin is currently based at the Kunsthalle Wien, an exhibition space for contemporary art and related discourses run by the City of Vienna. There she developed and directed the participatory project Community College (2013–2020), as well as conceptual guided tours, and experimental approaches for art conversations (Learning from Vulnerability). Karin Schneider is Head of Art Education at the Museums of the City of Linz, Lentos Art Museum, and Nordico City Museum. In addition, she is part of several projects to develop and research art-based methods of history education with focus on difficult cultural heritage.Footnote1 Together we research, publish, and teach on the history, theory, and methodology of art and museum education, always driven by the question of how this field of practice can be advanced to respond to pressing social issues.Footnote2 For this, we approach museums, exhibitions, and the objects on display (or in the storage) as environments to experiment with education methods that we develop specifically for each occasion. With the overarching goal to better understand how to actually talk to each other in such a way that new thoughts emerge, conflicts can be acknowledged as part of the debate, and different vulnerabilities must be taken into account. In this regard, our approach follows the theoretical viewpoints of constructivist pedagogy which “celebrates and encourages personal meaning making” as part of learning processes in museums and exhibitions.Footnote3 It puts an emphasis on the inclusion of subjective interpretation and personal perspectives of visitors on museum content, and “advocates a style of education that is necessary for supporting critical thinking and for developing a society that values diversity and respect for others.”Footnote4

We understand this as political work that aims to create settings for encounter and conversation that allow us to approach social issues that are hard to talk about because of embedded contradictions and unconscious biases, such as racism, colonialism, anti-Semitism, and their nexus and histories.

Open spaces and engaged pedagogies in cultural institutions

To choose museums and art galleries as contexts for this type of work relates to an idea of the cultural institutions as spaces “to really think through the present, what is happening, how to think of it as historical, in its historical contingencies, and how to map out other possibilities for the future,” as Wayne Modest, Director of Content at the National Museum of World Cultures and the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam (Netherlands), puts it.Footnote5 Modest is here addressing ethnographic museums and how their colonial histories reverberate in the present. Our takeaway is that a positive vision of cultural institutions as spaces for “societal conversations of what it means to live in the world with others” is indispensably grounded in a critical perspective that reckons with their troubled legacies and difficult heritages.Footnote6 The methods we strive to develop, test, and reflect upon are situated in and informed by these productive tensions. Ultimately, we are concerned with exploring our own implications in what we think needs to be criticized or transformed – regimes of epistemic power, inequality, and exclusion, and their histories.

Engaged museum pedagogies, as we understand it, are in alliance with the agenda to “stay with”Footnote7 moments of “critical discomfort,”Footnote8 so as to open up “a generative space for us to imagine another kind of museum practice in the future.” Modest emphasizes the decisive role of voices “outside of the museum” in the introduction of this transformative “critical practice.” He underscores that especially the “urgency for decolonization didn’t come from us! It came from activists out there, indigenous communities out there.”Footnote9 This viewpoint inspires our own practices and it is connected with the widespread thought in museum educational debates to “open up” spaces, so as to include voices and knowledges that, due to mechanisms of social exclusion, haven’t been given adequate access to and representation by cultural institutions as their democratic mission should entail. We take this approach very seriously. However, translating it into our own concrete museum educational practice raises some questions that we will discuss below.

The claim to open museum spaces follows different calls: On the one hand, it is a matter of a basic democratic imperative to enable cultural participation. On the other hand, hopes are that the participation of formerly excluded people could also change the institutional content, so as to shake up hegemonic models of knowledge production. The idea is that those yet-to-be-audiences have a “truer” knowledge of the dynamics of society due to their specific position on the margins.

We experience these assumptions as widespread in critical educational contexts, often as unconscious implications. We suggest understanding them as inspired by viewpoints brought forward by feminist and socio-critical standpoint theories which argue that “knowledge stems from social position,” and “that people from an oppressed class have special access to knowledge that is not available to those from a privileged class.”Footnote10 In open education situations, the assumption is that this truth can appear or at least flash up for a moment but only if one listens to these “marginalized others” and gives their voices a forum. Building on her expanded critical studies on the colonial power structure of the museum, museum education, and participatory projects museologist Bernadette Lynch proposes:

with the museum as participatory […] institution at the heart of civil society, community participants are no longer seen as “beneficiaries”, but rather as “critical friends”. Thus the museum becomes a sphere of contestation […], one in which people might begin to exercise their political agency as citizens, and might include processes of mobilization and local cultural and social activism.Footnote11

Denkbilder (thought images)

In order to open a space, it is not enough to open doors. As educators we know that impactful inclusion depends on language, what we propose as activities, image politics, and, maybe most important, the issues and questions around which to assemble. In recent years, we have spelled out the method of thought images (Denkbilder) not only, but above all, for educational contexts dealing with politics of history and memory.Footnote12 Thought images are part of our set of tools with which we aim to render open spaces (e.g. the gallery) more complex and to facilitate conversations in complicated spaces (like the post-Nazi environment of Austria).Footnote13 The goal is to enable engagement with difficult historical and political issues, often led by the desire to understand our own implication in an issue.

In 2016 we developed the prototype of the thought image method for an educational activity in the exhibition “Im Keller” im Keller (“In the Basement” in the Basement) at the Viennese gallery GPLcontemporary, to which we were invited by the curator Marcello Farabegoli. The exhibition featured single images from the film Im Keller (In the Basement, 2014) by the Austrian filmmaker Ulrich Seidl. The film tells stories about people in Austria “who pursue their obsessions in hiding” in their basements.Footnote14 One of the film scenes provoked a scandal, as it caught a glimpse of a collection of Nazi devotional objects and social activities such as gathering together and singing within this setting in the basement.Footnote15 Participants in one of the scenes were identified as (later) local ÖVP (the conservative party of Austria) councilors, and convictions for “Wiederbetätigung” (re-activation of references to National-socialism, which is forbidden in Austria) followed, as well as confiscation of the materials in the cellar.

One picture of this sequence around the “Nazi” cellar was shown in the exhibition, and curator Marcello Farabegoli was concerned not to leave the display of Nazi symbols undiscussed. What kind of art education could be done in reference to such an exhibit?

Was it really obvious what should be discussed in view of this picture? Is it about the scandal surrounding the film? And have we understood what caused the scandal, anyway? Was it the content of the image, the media discourse, or the political situation in Austria, to which this image presumably also refers?

Moreover, with the audience we expected in the gallery, did we not have to assume that we would be engaging in “preaching to the converted,” i.e. a conversation amongst people who are all against National Socialism, anyway? We assumed that scandals, in the form of media uproar, conceal rather than reveal their political triggering mechanisms; even artistic works that aim at a scandal often mask the political more than they denote it. For all these reasons, we decided to take a detour to find a more complex understanding of the political field in which truth is not organized according to the principle of either/or, or us and them.

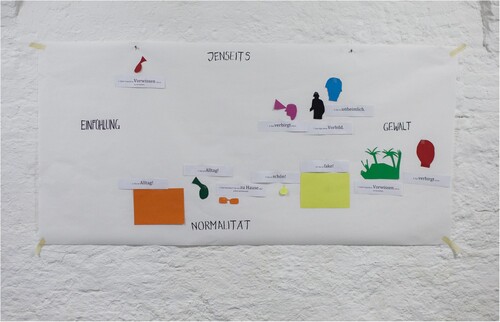

In order to do this, we developed a task that would first lead the participants more closely to the picture and away from an immediate discussion. Instead of expressing an opinion straight away, they were asked to select one thing in the picture that they personally felt corresponded to one of the following criteria: “This requires prior knowledge in order to understand it,” “This is everyday life,” “Each of us has used this at home or before,” “I had to learn this at some point,” “This follows an example,” “This refers to something outside of the picture,” “This is uncanny,” “This is beautiful!,” “This is hiding something,” or “This is fake!” Each person was given one of these criteria on a strip of paper, without knowing what the others received. The assignment was then to cut out their finding as a silhouette from colored paper (). The resulting figures were placed on the opposite wall in a new coordinate system, which we spanned between the following terms Jenseits/Normalität and Einfühlung/Gewalt (Beyond/Normality, Empathy/Violence) ().

Figure 1. Curator Marcello Farabegoli participates in the creation of the “thought image.” Photo © Gianmaria Gava.

Figure 2. The “thought image” in the exhibition ULRICH SEIDL ‘Im Keller’ im Keller (ULRICH SEIDL ‘In the Basement’, in the Basement) curated by Marcello Farabegoli for the Art Gallery GPLcontemporary, Vienna, 2016. Photo © Gianmaria Gava.

What emerged was a tableau – which in this case diverted the gaze from the original image (in which, we assumed, one could only see one thing, the scandal), and onto the opposite wall. This resulted in constellations that created tensions of thought, such as when, for example, the category “prior knowledge” appeared twice but in two diametrical quadrants. Thus a “thought image” was created, a rearrangement of the original picture, which could now be viewed anew and thought through from a distance, but which actually brings you close to it. These rearrangements make it possible to generate an understanding of what brings us and our everyday lives in proximity to the scene in the picture and its inherent violence.

For example, elements from a “Nazi basement” that we originally found simply scandalous ended up in the field of “normality.” The prompts we formulated were based on the desire to step out of the logic of scandal with the participants and to bring ourselves closer to what we saw. This allowed us to work out the actual, but hidden and silent “scandal behind the scandal”: the unspoken “post-Nazi normality” of Austria, whereby relations of violence weave themselves in an entangled way into all local family histories. With prompting phrases such as “This is everyday life!”, “This is beautiful!”, but also “This is uncanny” and “This hides something,” we opened up possibilities of both approaching and questioning our own history.

What we propose here is to try out what happens to our coordinate systems when we begin to locate the everyday in the abysmal, and the scandalous in the everyday. Our thesis is that in the “logic of the scandal,” a construction of a position of the Other is at work, which makes it possible to externalize responsibilities and to distance oneself – for example, from the “Nazis in the basement.” In contrast, the collective assemblage of the thought image makes it possible to discover oneself in the other and in the rejected.

Here we especially want to problematize a central function of the scandal (as justified as it might be, in view of the displayed Nazi worship): instead of working through an issue at stake and engagement in dialogue, the scandals produce a clear division between “us” and “them,” “good” and “bad,” or “perpetrators” and “victims,” and allows the “we” to locate itself at no cost on the side of the “righteous,” empathic with the victims. We propose stepping out of this logic of dichotomous, fixed subject positions with Michael Rothberg’s concept of the “implicated subject”:

(…) an implicated subject is neither victim nor perpetrator, but rather a participant in histories and social formations that generate the position of victim and perpetrator, and yet in which most people do not occupy such clear cut roles.Footnote16

New mappings

What does it mean for our methodological proposal to shift coordinate systems together with the participants of museum educational activities if the bigger context is a social situation where such shifts take place anyway? What if the coordinate systems are already being re-mapped, what openings would then be productive?

With the pandemic crises and the subsequent of splitting of society, basic parameters of democratic social agreements have been thrown into disarray. The requirement for Social Distancing on the one hand affected the daily work of educators in museums and cultural institutions. Compliance with COVID-19 safety regulations had to be monitored, and with masks, proof of vaccinations or tests, the question of who is allowed to access often became a matter of negotiation or even dispute up front. But the development also put more fundamental pressure on the concepts of open spaces and inclusion of voices from the margins. The protests against the pandemic measures, at least as we experienced them in Austria and Europe, also confused the clear layout of which groups in society justifiably claim a need for resistance against oppression and dominant systems of knowledge. Core agents of the protests called themselves Querdenker, meaning contrarian, or out-of-the-box thinker or counter/cross thinker. These protesters instigated counter-hegemonic activism, voiced outrage, and experienced themselves as marginalized groups of society who suffer from systems of biopolitical violence. In order to underline their ultimate victim position, the protesters used strategies of counter-culture activism and problematically identified themselves with the victims of the Holocaust. They understood themselves as victims of “vaccination fascism,” “brutal exclusion,” or “human experiments,” and marked themselves with “the yellow star” that Jews were forced to wear by the Nazis.Footnote17

If we wish to understand cultural spaces as places for public negotiation of burning issues of society, how do we react and position ourselves to this new mapping of who claims strategies of activism, resistance, and of the position of the oppressed?

To draw parallels with the above example, from our perspective, the Corona demonstrators are also on the “other side,” the “not us.” While Ulrich Seidl’s “basement-Nazis” are staged by him as such and thus offer the film or exhibition audience a foil of demarcation, the Corona demonstrators stage themselves as the marginalized. They see themselves as the “victims” of a “mainstream” campaign directed not only against them as individuals but against the “truth” they claim to courageously represent. Being in possession of the “actual truth” allows them to uncover the conspiracy of the powerful, in which the powerful are just puppets of puppet masters in the background, backed by the fake news media. From their perspective, the whole system must be resisted because it is “based on lies and excludes the broad masses from democratic participation.”Footnote18

In this thinking, we can find a dialectical link between “victim,” “margin,” and “truth.” Because they look at society from this victim position, a marginalized standpoint, they claim to better examine the true core of social relations, to be closer to the truth, and to appear as truth’s silenced messengers. And because they are the only ones who dare to tell the truth, they are marginalized by the mainstream discourse. Now we could easily argue that these are only “imagined victims,” whose whining does not actually penetrate the social power structure and whose stagings fail to reflect their true social positioning. Both the “basement Nazis” and the majority of the Corona protesters in Germany (and it can be assumed also in Austria) are actually part of the center of society/middle class, well situated and socially at little risk of povertyFootnote19 Their marginalization derives from self-positioning. In contrast, feminist and socio-critically informed standpoint theories such as those of Sandra Harding,Footnote20 Patricia Hill CollinsFootnote21, bell hooks,Footnote22 or the concept of situated knowledges by Donna Haraway,Footnote23 are based on sociological and socio-political analysis of objectively marginalized positions in the social power structure, e.g. of women, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, or workers. Nevertheless, the self-presentation of participants in the pandemic protests challenges the positive projections on the position of the marginalized that the standpoint theory might elicit. Such projections are based on the conscious or unconscious idea that positions on the margins of society carry with them a truth; in other words, this assumes that because of their position on the fringes, these groups have a sharpened understanding of social power structures.

Our thesis is that we, as well, are influenced by these assumptions and projections when we develop our methods, no matter how (self)critically we conceive them. Could inquiring into our own implications offer a way out of these projections? Then it would be about how we (i.e. not only the participants but we as educators) are implicated and interconnected in social relations permeated by power structures and differences? It can be deeply unsettling to see one’s one place in the history of racism, colonialism, anti-Semitism and the connected appeals for responsibility. Could one reason why we find it so difficult to translate these insights into an educational practice be that exploring implications, in the sense that Rothberg outlines, touches on vulnerabilities, i.e. that it starts to hurt? This is the track we want to follow in our third example.

Back to the art spaces

With our third example, we return to the art context. We maintain our skepticism about scandal logic, as well as an apprehension about a projection of “the marginalized” as always “the good guys” and the division between “us” and “them.” And we are further driven to open museum and art spaces as sites of negotiation, and to develop a methodical repertoire for this. Here we would like to re-visit documenta fifteen, 2022 and the artwork that was first veiled and then removed, becoming emblematic of this documenta’s anti-Semitism scandal: the banner People’s Justice by the Indonesian artist collective Taring Padi.Footnote24

The main accusation of anti-Semitism was related to motifs in the picture, such as the Star of David on the neckerchief of a soldier signed “Mossad” and mutated into a pig. Furthermore, it depicts a figure that can be described as a chimera of vampire (red, bloodshot eyes and pointed teeth), businessman (bowler hat, suit and cigar) and the Jew (hat, side-locks) who is marked as the ultimate evil with the Nazi SS symbol written on his hat. It was no surprise that such images were read and scandalized as anti-Semitic. However, we would like to ask whether focusing on these symbols helps us to understand the mechanisms that led to the appearance of the Jew as the personification of the ultimate evil in this specific context. We again suspect that the “logic of the scandal” is not conducive to the opening, which we believe is necessary in order to take a closer look at things and to be able to start learning processes.Footnote25 As art educators, we think that the image could be an occasion to investigate how anti-Semitism works.

We are dealing here with many open questions that are condensed through and in the banner image. How is it possible that such an unfiltered anti-Semitic representation can be found in the midst of an arrangement that actually seeks to stage a morally positive, anti-fascist utopia and fight against inhuman injustices? Can such utopias attract figures like this? What does this mean for our political perspectives, and what do we have to pay attention to? Are there elements in the picture that we would spontaneously agree with, that we like, and support? But then how are we to understand the association of such elements with an anti-Semitic figure?

The Corona deniers directed their protests against the powerful “those up there,” who they insinuated were in league with the media, science, and capital (the “pharmaceutical lobby”), planning the destruction and control of the ordinary people. Do such positions share a discursive field with left-wing power-critical and anti-imperialist positions, and if so, how is this possible?Footnote26 How should we understand an anti-Semitic – or in the case of the Corona protesters – Holocaust-denial-related symbolic repertoire in this context?

There are a number of studies and theoretical considerations on this issue.Footnote27 Still for us, the question remains what this means on the practical level for moderated conversations, education, and possible actions of solidarity. However, the atmosphere created by the “logic of the scandal” that informed many of the public debates about the documenta prevented both insight into the construction of anti-Semitic worldviews – as, we think, could have been gained through a deeper image analysis – and an understanding of the political context in which such images are painted. The banner relates to the misery, anger, and sadness of those traumatized by the brutal and genocidal military dictatorship under Suharto supported by the West in the wake of a colonial history of Indonesia.Footnote28

How can we discuss colonialism and anti-Semitism and both of its wounds in a connected way? We are by no means the only ones who see it as essential that this dialogue should happen.Footnote29 What art and gallery education could contribute to such a task is to find and facilitate ways and formats to moderate the controversy, inviting participants to truly look at the picture, with diligence diffracted by carefully designed questions that lead out of a logic of “always having already known.” This could have the consequence that we meet as fellow questioners in these spaces of education. Also, in order to be able to understand, name, and criticize anti-Semitism, we strongly believe that we need to bring in methods that invite us to step out of the logic of scandalization (as justified as it is in face of the trigger of trauma such images can cause) and to scrutinize what the image itself (and not its creators, critics, or defenders) wants to tell and teach us.

And yet this has been strangely difficult for us since we started discussing the debate around documenta in the last year and tried to think about ways to respond as art educators. It was as if we ourselves were hesitant to undergo this exercise. This time we are more implicated than in the two aforementioned examples, with our bodies, our personal histories, connections, and friendships. We do not identify with the filmmaker Ulrich Seidl, and even before our analysis of the “Nazi basement” image, we shared some of the existing criticism of his exoticizing practice of exposing people. It was easy for us to criticize the distancing of the Nazis as the Others within an Austrian context. And at the same time, we could reckon with the unanimous distancing of the gallery audience from a cellar full of Nazi devotional objects.Footnote30 Hence it was productive to introduce a method that challenged that distance, thereby offering all those involved the opportunity to produce a different, clearer knowledge, one informed by a more careful view of one’s own social and family history, rather than by prompt indignation. One thing was also clear from the example of the Corona protests: envisioning an educational activity around this question is complex and somewhat uncomfortable, but does not really shake our own world perception framework nor necessarily our friendships and working relations. But in the case of the firstly covered and then removed banner, People’s Justice, at documenta fifteen, things are different.

It concerns an anti-fascist and anti-colonial struggle in the Global South that we support. It is about people's liberation and radical criticism of capitalism, about justice and solidarity with the oppressed and disenfranchized. The artists themselves, the collective Taring Padi, are also representatives of these struggles, and they are actually among the ones we would like to listen to and learn from. If anti-Semitic building-blocks appear in this context, then this also creates in our contexts (those of critical art educators), and in ourselves, reflexes of defensiveness and benevolent explanations. In relation to the basement Nazis and the conspiracy theorists, this attitude would appear suspicious. However, our caution might be appropriate in the case of the banner. In contrast to the examples above, the experiences of exclusion and othering that artists from the Global South face reveal real social power and inequality relations. People’s Justice and other images by Taring Padi speak of real oppressive conditions caused by global capitalism and imperialism. The group’s visual language owes itself to traumatic experiences forged in the fight against a brutal regime and its aftermath. In the case of Taring Padi, we cannot speak of staged or borrowed victim positions.

All of this troubles our knowledge regarding which side we are on and which truth we want to create space for in the case of an education activity. In contrast to the first example of the Nazi-symbols, here we cannot count on an audience sharing the same view regarding anti-Semitism and “the scandal” in the context of documenta fifteen. In our numerous talks with many colleagues and friends in the last year, we understood that there is also no consensus among art educators and even less among those who wish to position themselves as critical voices. Do we deny or play down anti-Semitism in the art field if we propose a more differentiated judgment and are skeptical about the scandal-mongers? Are we denying or playing down structural and open racism and colonial influences if we take those seriously who sense anti-Semitism also on an institutional, structural level and focus on the anti-Semitic triggers and also scandalize the curatorial approaches that led to their exhibition?

The confusion concerning how little critical art educators, including ourselves, have to contribute here on a content and methodological level remains. Criticism and deconstruction in relation to those who have always been “not us” and marked as evil (basement Nazis, conspiracy theorists) are easier. We think that it would be productive to reconsider at what points ideas and concepts of open spaces and critical practices are formatted along the categories of we/they and true/false.

It is for this reason that in the aftermath, documenta fifteen can be considered such a good training ground for practicing methodical precision in the development of spaces that allow for a collective search for implications beyond the dichotomies of the logic of scandals. Precisely because Taring Padi’s hidden-object puzzle People’s Justice, and the debate that accompanies it, is so confusing, and because every position seems to be fraught with intolerability, it is the perfect context to work out ways to render the spaces we want to open as more complex and to facilitate conversations in complicated spaces. And getting stuck in the development of a concrete method helped us to recognize our vulnerability in the unrest of implication. We consider this vulnerability and the way it accompanies the acknowledgement of our implication as the necessary building blocks of our next methodological approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Hubin

Andrea Hubin is an art historian and art educator, currently based at the Kunsthalle Wien, where she developed and directed, among other things, the participatory project Community College in 2013–2020. Other contexts of her work as an art educator included Berlin Biennale 5, Volkskundemuseum Wien, and Generali Foundation Wien. 2007 she was part of the arts education project at the documenta 12 and was co-contributor of the knowledge transfer project DEUTSCH WISSEN in this context. Subsequently, she did research and published on educative concepts of the first documenta (1955).

Karin Schneider

Karin Schneider is a contemporary historian and art educator. She is head of art education at the Museums of the City of Linz, Lentos Art Museum and Nordico City Museum. From 2007 to 2019, she was involved in several projects to develop and research art-based methods of history education including MemScreen and Conserved Memories at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and TRACES – transmitting contentious cultural heritages with the arts at the Institute for Art Education at the Zurich University of the Arts. 2001–2007 she was the staff member for art education at the mumok, Vienna. She was co-coordinator of the EU project MemAct!, which deals with new methods of Holocaust education.

Together Karin Schneider and Andrea Hubin research, publish, and teach on the history, theory, and methods of art education. Working contexts include the project Intertwining Hi/Stories of Arts Education of the international network Another Roadmap for Arts Education and the University of Applied Arts Vienna. They develop new methodological approaches for art education (e.g. Learning from Vulnerability, Denkbilder, Talking with objects) and implement them in discursive projects with an experimental-performative character.

Notes

1 e.g. EU project MemAct, project on new methods of Holocaust education with Wolfgang Schmutz and Paul Salmons, https://memact.at/conference.pdf (accessed June 5, 2023), Mind Crossing, participatory performance in the open space telling a story of Holocaust survivors with Jasmin Avissar and Tal Gur; Synoptic Story Telling in a Multidirectional Vienna, Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna, with Friedemann Derschmidt, Alaa Alkurdi, Anne Pritchard Smith, Nikolaus Wildner, https://www.akbild.ac.at/de/forschung/projekte/forschungsprojekte/2021/synoptic-storytelling-in-a-multidirectional-vienna (accessed July 23, 2023).

2 See for example: Hubin and Schneider, “Flight of Riddles,” 1–15.

3 See for example: George E. Hein, “The Challenge and Significance of Constructivism,” 4, and Hein, “The Constructivist Museum,” 21–23.

4 Hein, Challenge and Significance, 6.

5 Wayne Modest, “Museums Are Investments in Critical Discomfort,” 70.

6 Wayne Modest in an American Anthropologist Podcast Special Feature on the 2018 Museum Ethnographer’s Group conference “Decolonizing the Museum in Practice”, for a transcript see: https://www.americananthropologist.org/podcast/decolonizing-museums-in-practice-part-03.

7 In the sense of Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble.

8 Modest, Museums Are Investments, 69.

9 Ibid.

10 Borland, “Standpoint theory”.

11 Lynch, “Good for you, but I don't care!”

12 For previous publications about this method, see Hubin and Schneider, “Dritte Sachen und Denkbilder,” 453–62; and Schneider, “Mit Geschichte eine Beziehung eingehen,” 19–28.

13 Other examples are a.o. Talking to/with objects, Learning from Vulnerability – Creating Care Packages (Lentos Linz, 2022), Performing the museum and the Workshop Brutality, its Languages, its Spaces of Articulation (Kunsthalle Wien, 2016).

14 “In Austria the basement is a locus of free time and the private sphere. Many Austrians spend more time in the basement of their single-family homes than in their living room, which often serves only for show. In the basement they can satisfy their real needs and pursue hobbies, passions and obsessions. In our unconscious the basement is also a place of darkness, a place of fear, a place of human abysses.” Seidl, Director’s statement.

15 For a trailer including the mentioned scene, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjvpwyJm89A (accessed July 23, 2023).

16 Rothberg, The Implicated Subject, 2.

17 Smith, “Holocaust Survivors Condemn Anti-Vaccine Protesters’ Use Of Nazi Imagery.”

18 Naumann and Kamann, Corona-Krieger, 35.

19 Koos, “Konturen einer heterogenen Misstrauensgemeinschaft,” 67–90.

20 Harding, “Rethinking standpoint epistemology,” 437–70.

21 Collins, “Some Group Matters,” 205–229.

22 Hooks, “Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness,” 15–23.

23 Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 575–99.

24 For a brief overview and the contentious parts of the image see e.g.: https://www.dw.com/en/the-anti-semitism-scandal-at-documenta-15-how-could-it-happen/a-63140490. For the full image, see e.g. https://www.derstandard.at/consent/tcf/story/2000136707611/documenta-fifteen-ruf-nach-entfernung-eines-werks-wird-laut (accessed July 23, 2023).

25 We, in no way, want to say that anti-Semitism in the art field is not scandalous. The scandalization is justified, but, from our point of view, not helpful.

26 For historical references in the German/Austrian context, see: Greiner, Die Diktatur der Wahrheit.

27 E.g. on anti-Semitc criticism of capitalism: Postone, “Die Logik des Antisemitismus,” 13–25; on communist anti-Semitism and conspiracy theories: Tabarovsky, “Demonization Blueprints,” 1–20. On the critique of dichotomies in ant-imperialism and left wing anti-Semitism: Stoetzler, “Capitalism, the Nation and Societal Corrosion;” Marjanović, “Unignoring Anti-semitism in Contexts of Critical Knowledge Production.”

28 “The banner was born out of our struggles of living under Suharto’s military dictatorship, where violence, exploitation and censorship were a daily reality.” https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/press-releases/statement-by-taring-padi-on-dismantling-peoples-justice/; see also: https://www.cicero.de/kultur/antisemitismus-documenta-15-taring-padi-kassel-diskriminierung-indonesien-postkolonialonialismus.

29 Prominent voices in this line were the artist Hito Steyerl and the Anne Frank Educational Center in Frankfurt.

30 Perhaps it was easier for us to propose to think about implications in this case, because we were able to keep our distance in some aspects. We did not really leave the position of knowing and were not shaken in our subject position as “critical educators,” maybe even strengthened.

Bibliography

- “Banner auf Documenta wird nach Antisemitismusvorwürfen abgebaut.” Der Standard, June 20, 2022. https://www.derstandard.at/consent/tcf/story/2000136707611/documenta-fifteen-ruf-nach-entfernung-eines-werks-wirdlaut.

- Borland, Elizabeth. “Standpoint Theory.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed 26 July 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/standpoint-theory.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. “Some Group Matters: Intersectionality, Situated Standpoints, and Black Feminist Thought.” In A Companion to African-American Philosophy, edited by Tommy Lee Lott and John P. Pittman, 205–229. New York: Blackwell, 2003.

- Greiner, Steffen. Die Diktatur der Wahrheit: Eine Zeitreise zu den ersten Querdenkern. Berlin: Klett-Cotta, 2022.

- Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn, 1988): 575–599.

- Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. United States of America: Duke University Press, 2016.

- Harding, Sandra. “Rethinking Standpoint Epistemology: What is ‘Strong Objectivity?” The Centennial Review 36, no. 3 (1992): 437–470.

- Hein, George E. “The Challenge and Significance of Constructivism.” Keynote Address Delivered at the Hands-On! Europe Conference (London, November 15, 2001), http://www.georgehein.com/downloads/challengeSignifHeinHOE.pdf.

- Hein, George E. “The Constructivist Museum.” Journal for Education in Museums, no. 16 (1995): 21–23.

- hooks, bell. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 36 (1989): 15–23.

- Hubin, Andrea, and Karin Schneider. “Dritte Sachen und Denkbilder. Methodische Überlegungen zur Neuanordnung von Redeweisen in Kunstvermittlungsaktionen.” In The Missing_LINK. Übergangsformen von Kunst und Pädagogik in der kulturellen Bildung, edited by Joachim Kettel, 453–462. Oberhausen: Athena, 2017.

- Hubin, Andrea, and Karin Schneider. “Flight of Riddles – Thinking Through the Difficult Heritage of Progressive Art Education in Austria.” Art Education Research, no. 15 (2018): 1–15. https://blog.zhdk.ch/iaejournal/files/2019/03/AER15_Hubin_Schneider_E_20190227.pdf.

- IN THE BASEMENT - Ulrich Seidl (trailer). Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjvpwyJm89A.

- Koos, Sebastian. “Konturen einer heterogenen »Misstrauensgemeinschaft«: Die soziale Zusammensetzung der Corona-Proteste und die Motive ihrer Teilnehmer:innen.” In Die Misstrauensgemeinschaft der »Querdenker«: Die Corona-Proteste aus kultur- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Perspektive, edited by Sven Reichardt, 67–90. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2021.

- Lynch, Bernadette. “‘Good for You, but I Don’t Care!’: Critical Museum Pedagogy in Educational and Curatorial Practice.” Paper for the “DIFFERENCES” Symposium, University of the Arts, ZHdK, Zürich 2016. https://www.academia.edu/26257963/_Good_for_you_but_I_dont_care_critical_museum_pedagogy_in_educational_and_curatorial_practice.

- Marjanović, Ivana. “Unignoring Anti-Semitism in Contexts of Critical Knowledge Production.” April 30, 2012. https://unignoringantisemitism.blogspot.com/.

- Modest, Wayne. “Museums Are Investments in Critical Discomfort.” In Across Anthropology: Troubling Colonial Legacies, Museums, and the Curatorial, edited by Margareta von Oswald and Jonas Tinius, 65–75. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020.

- Naumann, Annelie, and Matthias Kamann. Corona-Krieger: Verschwörungsmythen und die Neuen Rechte. Berlin: Das Neue Berlin, 2021.

- Postone, Moishe. “Die Logik des Antisemitismus.” Merkur. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur europäisches Denken 36 (January, 1982): 13–25.

- Rothberg, Michael. The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019.

- Schneider, Karin. “Mit Geschichte eine Beziehung eingehen. Kunstbasierte Verfahren in der Bildungsarbeit zu Nationalsozialismus und Holocaust.” In Die künstlerische Auseinandersetzung mit dem Nationalsozialismus. Jahrbuch 2017 der KZ-Gedenkstätte Mauthausen, edited by KZ-Gedenkstätte Mauthausen and Andreas Kranebitter, 19–28. Wien: new academic press, 2018.

- Seidl, Ulrich. “Director’s Statement.” https://www.ulrichseidl.com/en/ulrich-seidl-director/films/in-the-basement.

- Smith, Zachary Snowdon. “Holocaust Survivors Condemn Anti-Vaccine Protesters’ Use of Nazi Imagery.” Forbes, Jan 27, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/zacharysmith/2022/01/27/holocaust-survivors-condemn-anti-vaccineprotesters-use-of-nazi-imagery/.

- “Statement by Taring Padi on dismantling ‘People’s Justice’.” June 24, 2022. Accessed 26 July 2023. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/press-releases/statement-by-taring-padi-ondismantling-peoples-justice/.

- Stoetzler, Marcel. “Capitalism, the Nation and Societal Corrosion: Notes on ‘Left-Wing Antisemitism’.” Journal of Social Justice 9 (2019): 1–45.

- Tabarovsky, Izabella. “Demonization Blueprints: Soviet Conspiracist Antizionism in Contemporary Left-Wing Discourse.” Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism 5, no. 1 (March 1, 2022): 1–20.

- “The Anti-Semitism Scandal at Documenta 15.” DW Deutsche Welle, September 15, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/the-antisemitism-scandal-at-documenta-15-how-could-it-happen/a-63140490.

- Thiele, Ulrich. “Das Werk ist immer klüger als sein Autor.” Cicero, June 26, 2022. https://www.cicero.de/kultur/antisemitismus-documenta-15-taring-padi-kassel-diskriminierung-indonesien-postkolonialonialismus.

- Thomas, Deborah, and Chris Green. “Special Feature: Decolonizing Museums in Practice – Part 3.” Interview with Wayne Modest. American Anthropologist, Podcast Special Feature on the 2018 Museum Ethnographer’s Group conference “Decolonizing the Museum in Practice”, https://www.americananthropologist.org/podcast/decolonizing-museums-in-practice-part-03.