ABSTRACT

Objective

Lung disease is now recognized as an associated occupational hazard among farming and agricultural communities, however limited research surrounds lung health knowledge within our farming population. It is clear from this limited lack of knowledge that farming practices, perceptions and ideas relating to lung health are yet to be uncovered. This scoping review was conducted to identify what is known about lung health within farming and agricultural communities globally and to map the available evidence relating to lung health and lung health decline within this population. The objectives of this review were (1) focus on available lung health research from a global perspective specific to farming and agriculture relating to occupational lung exposures and (2) consolidate current knowledge, clearly identifying gaps within the literature.

Methods

This systematic scoping review of the literature is guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology framework. There were 22 studies eligible for inclusion within the scoping review, providing an up-to-date review of research conducted on lung health and lung disease in farming occupations.

Results

Results were grouped into three categories emerging from included studies: (1) focused on the prevalence of respiratory symptoms/disease within farming and agricultural occupations, (2) measurements of dust and particulate matter and correlating these with respiratory conditions, (3) common respiratory conditions linked to a decline in lung health among farming and agricultural occupations. Results identified no study focused on or referred to lung health, lung health knowledge or lung health awareness as an outcome, with all studies focusing on respiratory symptoms, development of lung disease and the common occupational hazards this population are exposed to.

Conclusion

This scoping review demonstrates the lack of literature to specifically map available evidence relating to lung health and farming occupations. Many respiratory symptoms and conditions can arise directly and indirectly from agricultural environments, however many of these cases could be prevented by lung health knowledge within the farming population. The results of this scoping review will be used to inform knowledge, awareness, education, health promotion and future research within this population.

Introduction

When investigating lung health within farming and agricultural populations, the terms “lung health”, “lung disease” “respiratory health” and “respiratory disease” are used interchangeably throughout the literature. One clear message presented throughout the research is that to gain a true understanding of lung health, lung disease must also be addressed. For clarity and for the purpose of this review, Reyfman’sCitation1 definition of lung health as “the absence of overt lung disease” is used, with lung disease referring to a wide range of conditions, of which there are a number of different causes, e.g., genetic and environmental factors, tobacco smoking and occupational exposures.Citation2

To explore the understanding of a specific topic, we first need to assess the level of knowledge, as without knowledge there cannot be understanding. Knowledge is the theoretical or practical understanding of a specific subject, often defined as the ideas or understandings that are used to take effective action to achieve the entity’s goalCitation3 and refers to an awareness, facts, information and skills gained through experience or education on a topic under investigation.

Lung disease, in comparison to lung health, is clearly defined as “any problem that prevents the lungs from working properly” and is divided into three main categories: airways disease, lung tissue disease, and lung circulation disease.Citation4 Lung disease among adults is generally divided into obstructive and restrictive conditions, with the obstructive conditions being further divided into reversible and irreversible disease. As the population of the world ages, the burden from chronic lung diseases will continue to increase, with a larger number of people disabled by these conditions and a greater number of deaths attributable to them.Citation5

The development of lung disease can also be attributed to repeated and long-term exposure to certain employment-related irritants leading to an array of lung diseases that may have lasting effects. These effects can continue even after employment exposure ceases.Citation6–11 Occupational lung diseases are a group of respiratory conditions associated with workplace exposures to dusts, micro-organisms and vapours, acting as irritants, carcinogens, or immunological agents and have the potential to cause lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asbestosis, and pneumoconiosis.Citation12 Occupational lung diseases are related to particular occupational exposures in two main categories: lung tissue disease and airways disease. Obstructive airways disease is also a common pattern of occupational lung disease, which may be reversible (occupational asthma) but can also develop to an irreversible disease pattern (chronic bronchitis, emphysema or COPD). Airborne hazards (particulate matter [PM], vapours, gases and fumes) are a common exposure in occupational settings, particularly farming and agricultural environments, with a number of studies having identified malignant and chronic respiratory disease as a result of these repeated exposures.Citation7,Citation13,Citation14

Historically, farming has been defined as the art, science or occupation of cultivating the land, feeding, breeding, and raising livestock or poultry and the production of cropsCitation15 with the terms farming and agriculture used interchangeably throughout time. Farming and agricultural employment have been identified as risk factors for many lung diseases due to occupational exposures with researchers consistently reporting impaired lung function, chronic bronchitis (CB), chronic obstructive airways disease (COPD), asthma and symptoms of cough, phlegm production, wheezing and rhinitis.Citation16,Citation17 Farmers and agricultural employees have a complex set of occupational and lifestyle exposures that can influence their lung health, e.g., particle exposure to organic dusts from livestock barns and confinements, grain dusts, pesticides and microbial agents originating from hay, silage, bedding, feeding systems and machinery fumes.Citation18 These exposures coupled with continual changes in agricultural practices for example, moving from small scale family run farms to larger scale industries, highlight the need for focus on the impact and importance of lung health within this population. The 2016 Central Statistics Office reporting on the structure of farming in Ireland states that 164,400 are employed in the agri-food sector and the total number of farms in Ireland is 137,500.Citation19 Agricultural employment is also crucial to global economic growth. In 2018, it accounted for 4% of global gross domestic product (GDP) and in some developing countries, it can account for more than 25% of GDP.Citation20

To synthesize and systematically map current evidence, a scoping review was conducted. To determine the scope of a body of literature, scoping reviews are used to examine emerging evidence, concepts, or studies in a particular field.Citation21 A scoping review methodology was chosen due to the broad nature of lung health and lung disease and their association with the terms “farming” and “agriculture”. Previous work is limited when systematically mapping and recording current knowledge of lung health within the farming community.

This review was defined by the following question “What is the current available evidence relating to lung health and farming?”. The objectives of this review were: (1) focus on available lung health research from a global perspective specific to farming and agriculture relating to occupational lung exposures and (2) consolidate current knowledge of lung health, clearly identifying gaps within the literature.

Methods

This review is guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology frameworkCitation22 for scoping reviews. A systematic scoping review of literature focusing on lung health and lung disease within the farming population was conducted aimed at identifying a wide range of article types, allowing for transparency, reliability, and reproducibility of current literature while also adopting a broad search strategy.Citation22 Prior to conducting this review, a scoping review protocol was developed and revised following feedback from the research team including a leading professor of respiratory medicine and members of the nursing and academic communities.

Eligibility criteria

The goal of the search strategy was to identify and uncover gaps within the current available literature. Any published study or research papers included within this scoping review were required to have a specific focus on lung health, lung disease and/or decline, reduced lung function, and the prevalence of respiratory symptoms within farming and agricultural populations. English language, peer reviewed journal papers, published between 2010 and 2020, involving human participants over the age of 18 years were included for consideration. Original research papers incorporating all forms of study design were eligible for consideration if focused on lung health or lung disease as a result of farming and agricultural exposures. All studies included in the final review are based on the ‘Population-Concept-Context (PCC) framework recommended by the JBI Reviewers Manual ().Citation22 Studies conducted prior to 2010 were excluded in the review, in addition to publications that focused on lung cancer.

Table 1. Inclusion/Exclusion criteria.

Participants

This review considered all research studies that included human participants (any sex) over the age of 18 described as farmers, farm labourers, farm employees, agricultural employees, or agricultural occupation. Farmers were defined as those who owned or managed a farm,Citation23 and a farm is: an area of land and its buildings used for growing crops and rearing animals.Citation24

Concept

As global farming practices continue to develop and evolve, changes to a higher farm production process bring to the forefront the added risks associated with outdoor work in fields and yards as well as indoors within the barn, stable, or feeding environments.Citation25 Physically demanding work coupled with the exposure of employees to agricultural machinery, toxic chemicals, pesticides, animal and environmental dusts, as well as dangers from the natural environment add to a potential decline in lung health. Results from literature reviewed have reported an increase in cough in both farmers (34%) and agricultural workers (40%)Citation26 compared to those in the general population (10%).Citation27 In French dairy farms it has been suggested that dust exposure on dairy farms carries the same risk of developing COPD as cigarette smoking.Citation28 Farmers and agricultural employees often work long hours, 7 days per week, performing the same or similar daily tasks, continually increasing their exposure risks. From these published figures, national and international health promotion strategies and education could significantly improve the lung health status of farmers and those engaged in agricultural employment.

Many farmers and farm settings worldwide are now struggling with unprecedented challenges resulting from the COVID-19 Pandemic.Citation29 This global pandemic presents additional risks for those involved in farming and agriculture, but more specifically those employed in meat processing plants and seasonal agricultural workers. These industries are continually expanding within the industrial and employment sectors and include large numbers of employees working within close proximity of each other.Citation30 This pandemic has highlighted the growing concern for risks to lung health and the development of lung disease among the farming and agricultural communities.Citation31,Citation32

Information sources and search strategy

Research articles are limited to developed countries/regions including UK, Canada, United States of America, Continental Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand, considering all studies carried out in farming and agricultural settings. To identify potentially relevant literature, comprehensive searches were conducted in conjunction with the review team and librarian with the aim to locate both published and unpublished primary studies. To consider all forms of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods study designs for inclusion, a wide-ranging search of the EBSCO research platform was undertaken, and included the following databases: Academic search complete, APA PsychArticles, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, MEDLINE Full text, Scopus and JBI Evidence-based Practice. Gray literature searches were conducted to identify any non-indexed literature related to the topic of this scoping review, along with theses and dissertations. Based on the initial scoping review process, the search strategy was amended to exclude the term “lung cancer”. This decision was made based on the results yielded from its inclusion where the focus moves away from the terms “lung health” and “lung disease” and shifts to lung cancer, lung cancer treatments, and lung cancer prevention. Population focus also shifts from the farming and agricultural sectors to include vast proportions of populations not relevant for this specific scoping review. The search strategy conducted focused on the following search strings: (1) Farming, (2) Lung Health, and (3) Lung Disease ().

Table 2. March 2021 scoping review search strategy.

Reference lists of included studies and reviews were screened to ensure all relevant articles and material were included within this scoping review. Contact was made with authors when further information was required in relation to these included studies. All identified relevant articles from the search were transferred to the EndNote X9 referencing manager software package with all duplicates removed. The EndNote (X9) file was later transferred to the Covidence Systematic Review Software Management Package to begin the title and abstract screening process. Only studies conducted in English were considered for inclusion, as this is the review author’s first language, and most major medical and scientific journals are published in English, leading to a greater scope of articles for potential inclusion within this review.

Identification of potential studies

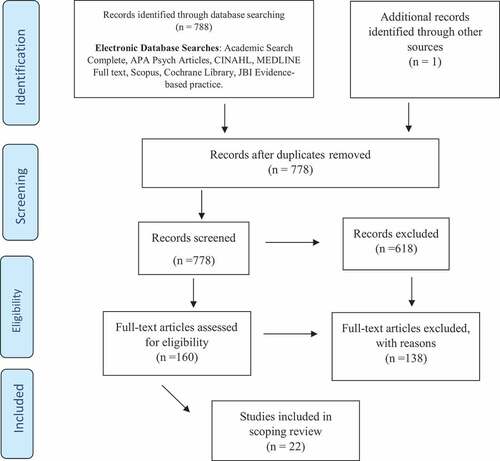

The literature search identified 778 citations following duplicate removal which were included for title and abstract review following initial screening. Based on title and abstract screening, 618 were excluded, with 160 citations eligible for full text review. Of these 160, 138 were excluded for the following reasons: wrong study design, population under the age of 18, not focused on lung health or lung disease, wrong study comparator, study data too dated despite study publication date meeting inclusion criteria, articles not published in English. A further four were excluded, as both reviewer and librarian were unable to retrieve these articles. 22 studies eligible for inclusion within the scoping review as outlined by the PRISMA diagram ().

Selection of relevant sources

To ensure consistency among the scoping review team, by applying the inclusion criteria, three reviewers screened all relevant articles for review, with first selection based on title and abstract screening. This approach also ensured consistency between the research question and purpose of the review. The second screening process was based on full-text screening. Any conflicts arising from both these processes were discussed until consensus was reached by all members of the review team. All peer-reviewed qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed-method studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included for the final scoping review.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

In terms of the geographical scope of the 22 studies, 59% were European studies (n = 13), 14% North American (n = 3), 14% (n = 3) Macedonian studies, 9% Australian studies (n = 2), and 1 Chinese study were included. Of the studies, 68% (n = 15) were published in the last 5 years, with the remaining 32% (n = 7) published within the last decade. Study populations included farmers, farming employees/labourers/managers working in dairy, crop, poultry, mushroom, and vegetable farming, with 36% (n = 8) of included studies used both matched and non-matched population control groups for study comparison.

Of the studies included, 23% (n = 5) focused on COPD prevalence and COPD-like symptoms among farming occupations, and 9% (n = 2) of studies looked at asthma risk factors and prevalence. 41% (n = 9) of studies concentrated on the prevalence of more general respiratory symptoms and the development of respiratory disease, with 27% (n = 6) of studies conducting a more in-depth review of the exposure of farming occupations to dust and thoracic particles. Within the scope of this analysis, no papers focused on lung health knowledge but mainly reported on lung health disease/decline and the development of respiratory symptoms within the chosen populations.

Types of methods and design

Of the included studies, four methodology types have been used. 86% utilized a quantitative cross-sectional design approach, with the remaining 11% using the following three study designs: longitudinal (n = 1), epidemiological (n = 1), and a mixed-method design (n = 1). Authors did not provide any further in-depth information into the methodologies used or the reasons behind the chosen designs. Spirometry testing (55%), exposure and occupational history assessments in addition to respiratory questionnaires and surveys (100%), respiratory inhalation, and exhalation sampling (23%) along with the assessment of farming practices and characteristics (27%) were the most common forms of data collection utilized throughout all included studies.

Types of outcomes measured

Results were grouped into three categories identified as the main focus emerging from the included studies: (1) focused on the prevalence of respiratory symptoms/disease in farming and agricultural occupation, (2) measuring the exposure to dust and particular matter, correlating these to respiratory conditions, and (3) common respiratory conditions linked to a decline in lung health in farming and agricultural occupation.

Prevalence of respiratory disease/symptoms in farmers and agricultural occupations

Using a cross-sectional study design, nine studies focused on the prevalence of chronic respiratory symptoms and impaired lung function. A variety of different farming activities were included: dairy farming,Citation13,Citation14,Citation26 crop farming,Citation33,Citation34 mixed farming (crop and dairy),Citation35 poultry farming,Citation36 greenhouse vegetable farming,Citation37 and mushroom farming.Citation38 Of the included studies, four incorporated a control group within their study design, using a non-farming population to compare against.Citation13,Citation14,Citation37,Citation39 Despite increased symptom prevalence, not all studies demonstrated a marked incidence of lung disease or decline in lung function parameters; however, all studies reported an increase in chronic respiratory symptoms, e.g., cough, wheeze, chronic bronchitis, asthma-like symptoms, and rhinitis. Results from the three studies focusing on dairy farming reported the prevalence of chronic respiratory symptoms among dairy farmers at 41%Citation13 with cough (34%), chronic bronchitis (CB) (35%), and wheezing (30%) reported in the last 12 months.Citation14–30 Obstructive and restrictive ventilatory patterns were observed at rates of 25% and 29%,Citation35 with additional study resultsCitation37 confirming 4% of participants having developed diagnosed lung diseases (CB, emphysema, and asthma) as a result of agricultural employment. Three studies notably reported a significant improvement in respiratory symptoms when workers were away from their agricultural environments or on holidays.Citation33,Citation36,Citation37

Measuring exposure to dust and particular matter (PM), correlating to respiratory conditions

Frequent exposure to organic dust and its microbial constituents has been identified as a primary threat to lung health, with organic dust containing multiple plant or animal particles. Five studies focused on a variety of farming and agricultural exposures (dairy, wheatbelt, and poultry farming) relating to PM exposure, organic dusts, thoracic dust particles, and endotoxin, and their correlation to the prevalence of chronic respiratory symptoms, lung health decline, and lung disease.Citation40–44 Poultry farming demonstrated a prevalence of diagnosed asthma at 6.4%, with clinical data presenting a trend of high incidence for both asthmatic (42.5%) and nasal symptoms (51.1%). In addition to these results, a high prevalence of respiratory symptoms without an asthma diagnosis was equally observed; wheezing (19.1%), coughing (29.8%), chest tightness (12.8%) with other respiratory problems (12.8%) also reported.Citation40 Reported results exploring indoor dairy farming exposures to organic dust, endotoxin, CO2, and total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), and measurements of the impact of different feeding systems, yielded a 42% reduction in the levels of inhalable endotoxin when working with semi-automated feeding systems rather than manual systems.Citation41 Higher levels of endotoxin were observed in manual feeding farms with inhalable dust levels increasing as the amount of feed distributed per cow increased. A second studyCitation43 reported a total of 10-minute mechanical bedding spreading increased thoracic dust exposure by 60%, endotoxin exposure by 120%, and gram-positive bacteria by >90%. Grain handling, silage, and slurry were further identified as major contributors to airborne contaminants. Storing manure in cowsheds and using automatic scrappers increased exposure to endotoxin by 126% and to gram-positive bacteria by 149%. These varied study results have demonstrated that this cohort of studied French dairy farmers were exposed to dust concentrations 3–4 times lower than that of American and other European dairy farmers.Citation40,Citation45,Citation46 Notably, one studyCitation40 reported 27.7% of all participants identified an improvement in respiratory symptoms during rest days and holidays, again suggesting an association between work-related activities, the development of respiratory symptoms, and an overall decline in lung health, with results consistent with previous review studies also included within this review.Citation33,Citation36,Citation37

Common respiratory conditions linked to a decline in lung health within farming and agricultural occupations

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are two of the most commonly researched conditions relating to reduced lung function, lung health decline, and the development of lung disease within larger farming communities. Three studies using a cross-sectional approach, and two studies including a control group for comparison, concentrated on the incidence of obstructive lung disease, namely COPD in farming and agricultural environments.Citation47–49 While all three studies reported chronic respiratory symptoms and symptoms of CB, one study has reported the prevalence of COPD was approximately 2-fold higher in the farming group than the non-farming control group.Citation48 COPD participants also reported more respiratory symptoms than the control group with 25% suffering from chronic cough and bronchitis and 31% reporting dyspnoea.Citation45 Results ascertained following a comprehensive cross-sectional study exploring the high incidence of obstructive lung disease in non-smoking farmers in Ireland reported the prevalence of chronic respiratory symptoms, with 40% of participants reporting upper respiratory symptoms (URS) 33% reporting cough, and 32% reporting dyspnoea and/or wheeze and of the 372 acceptable respiratory function measurements, 12% identified airflow obstruction.Citation47

Three further studies continued their focus on obstructive lung disease reporting on asthma and asthma-like symptoms.Citation25,Citation50,Citation51 Results from a Swiss epidemiological study where participants were divided into three groups considering both duration and levels of exposure where (1) work-related symptoms, (2) spirometry parameters, and (3) exhaled nitrogen oxide were all analysed.Citation50 Results reported 5.1% of primary farm operators had current asthma, with results in females significantly higher (7.3%) than those of their male counterparts (4.6%). A further cross-sectional study reported the prevalence of asthma attacks in the previous 12 months at 11.2% with the cumulative prevalence of asthma at 15.1%. The prevalence of rhinitis was 23.5% with reported symptoms higher in female participants with allergic rhinitis increasing the prevalence for cumulative asthma (p < .05).Citation51

Discussion

This scoping review is the first to specially map the current available evidence relating to lung health among farming and agricultural occupations. Results revealed that agricultural techniques and environments vary widely not only between countries but also on the farm itself, exposing workers to multiple exposures such as animal feeds, pesticide use, crop production methods, dusts, and endotoxins. Recent research has demonstrated that farming and agricultural occupations can have varied levels of organic dust and endotoxin exposures, often higher than the recommended health-based exposure levels.Citation41 The main focus of all studies centers on respiratory symptoms, potential development of lung disease, and common occupational hazards that this population are exposed to. General preventative farming strategies focus on the reduction of dust and gas generation, improving storage and ventilation to reduce the growth of moulds, bacteria, and endotoxins and the introduction of respiratory personal protective equipment.

Significant prevalence of non-smoking related airways limitations and chronic respiratory symptoms in farmers,Citation13,Citation47 with an increased level of upper airways symptoms among dairy farmers has been reported.Citation8,Citation26,Citation33 From the scope of the analysis undertaken, the burden associated with an increase in respiratory symptoms, a decline in lung health and an increase in diagnosed lung disease among this population is largely unrecognized, highlighting the need to identify lung health knowledge among farming and agricultural populations.

Recommendations from a number of global studiesCitation1,Citation3,Citation26,Citation47,Citation51 concluded that despite improvements in farming work practices, this population continue to suffer significant work-related respiratory symptoms. Due to the lack of information relating to the meaning and understanding of lung health among farming and agricultural populations, the increased burden of lung disease consideration is paramount when considering the high age-adjusted mortality rates within the farming and agricultural communities.Citation43 While national respiratory incidence and prevalence data are not available for this specific population group, in 2016 the mortality rate from respiratory disease increased by 14.6% from 2007 and, with lung cancer figures excluded, this increase is 16%.Citation2

With farming practices expanding from small scale traditional family farms to large-scale enterprises, farmers and farm workers are now at risk from increased exposure to airborne dusts, microbial agents and gases, increasing the risk for the development of chronic respiratory symptoms, lung disease and an overall decline in lung health. Occupational and environmental exposures in farming and agricultural settings are known to provoke inflammatory lung responses, increasing the risk for numerous respiratory diseases.Citation10,Citation44,Citation52 Farming and agricultural activities produce dust both outside (from working in fields) and inside (within the barn environment).

All review studies consistently report both restrictive and obstructive disease, decreased airflow limitations, and increased respiratory symptoms most commonly cough, wheezing, dyspnoea, rhinitis, and phlegm production.Citation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation51–53 This evidence could be interpreted with some degree of caution, as 86% of included papers are based on cross-sectional questionnaires and surveys relying on the self-reported responses of study participants; however, 57% of studies included additional forms data collection focusing on lung function testing, dust sampling, exposure measurements, and monitoring farm characteristics and activities. Results generated clearly identify strong links between farming and agricultural practices and known exposures; however, there is a clear lack of evidence focusing on farming and agricultural occupations knoweldge of lung health, how work practices and exposures can affect lung health, and the potential to develop lung health decline and disease if symptoms are left untreated.

While not all studies were able to provide satisfactory evidence of marked increases in diagnosed lung disease,Citation14,Citation47–49 all included studies identified a decline in lung function and clear evidence of the prevalence of respiratory symptoms. The increased prevalence of respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation in farmers raising cattle, swine, or poultry is consistent with those exposed to indoor air contaminants – carbon dioxide, dust, and endotoxin, all of which are determinants of COPD traits.Citation13,Citation14,Citation47,Citation49 In addition, numerous studies included within this scoping review reported all participants identified a significant improvement in respiratory symptoms when away from the agricultural employment environments (annual leave, holidays).Citation33,Citation36,Citation37,Citation40 The lack of discussion and debate relating to lung health knowledge in farming is a clear indication of the work that is required to empower this population to gain knowledge and understanding to improve lung health overall, preventing lung health decline, and in the recognition of respiratory symptoms.

Another key issue relating to the results of this scoping review is the apparent absence of qualitative research: all studies included were of a predominantly quantitative design. While there is clear evidence of numerous links between farming practices, associated working environments, and poor lung health, lung health knowledge among members of the farming community has not been considered.

The scoping review framework supported this review as the chosen topic area is extremely broad in nature, in relation to farming practices, characteristics, and the agricultural environments under review. One of the main strengths of this review is the clear, systematic nature of the search conducted, allowing for the mapping of the current literature. Limitations identified within this scoping review are the use of the term “lung health” and the interchangeable terms used throughout the included articles, e.g., “lung health”, “respiratory health”, “lung disease”, and “respiratory disease.” There is a potential that some studies may have been missed during the search process. By only including studies published in English, we may have missed important results that were published in other languages. Another important factor to note in relation to this scoping review is the male-dominated population in 95% of those included studies. Farming is traditionally a male dominated occupation, with just under 13,000 females employed in the Irish agricultural, farming, and fishing industry. This figure is 10.8% of the total and far below the EU average of 28.5%.Citation54

Conclusion

The main finding of this review is the lack of literature relating to lung health knowledge among farming and agricultural occupations. Previous research has failed to systematically map and categorize a general understanding of lung health and its meaning among the farming population in the prevention of lung health decline and the development of respiratory symptoms and potential lung disease. Central to discussing the findings of this review is considering the wider implications for policymakers, health and safety bodies, public health practitioners, researchers, and those developing and delivering health promotion education material. There is clear evidence presented of the risk to the lung health of farmers, but no research has focused on knowledge, prevention, or the promotion of lung health in this community. The results of this scoping review will be used to inform further research focusing on the areas of knowledge and health promotion within this population.Citation1

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. A. Coffey, Dr. L. Kingston and Prof. B.J. Plant for reviewing this manuscript and providing input and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Reyfman PA, Washko GR, Dransfield MT, Spira A, Han MK, Kalhan R. Defining impaired respiratory health. A paradigm shift for pulmonary medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;198(4):440–446. doi:10.1164/rccm.201801-0120PP.

- Irish Thoracic Society (ITS). Respiratory Health of the Nation [Internet] (IRE); [cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: https://irishthoracicsociety.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/RESP-Health-LATEST19.12.pdf

- Steve Denning. What is knowledge [Internet]. Washington (DC); [cited 2022 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.stevedenning.com/Knowledge-Management/what-is-knowledge.aspx

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: Lung Disease [Internet]. Durham (NC); [cited 2021 Mar 4] Available from: Lung Diseases (nih.gov).

- World Health Organisation: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [Internet]. (Europe); [cited 2021 Mar 5] Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd.

- Reynolds SJ, Nonnenmann MW, Basinas I, et al. Systematic review of respiratory health among dairy workers. J Agromedicine. 2013;18(3):219–243. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2013.797374.

- Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, Long S, et al. Pesticides are associated with allergic and non-allergic wheeze among male farmers. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(4):535–543. doi:10.1289/EHP315.

- Karunanayake CP, Hagel L, Rennie DC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of respiratory symptoms in rural population. J Agromedicine. 2015;20(3):310–317. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2015.1042613.

- van Doorn D, Richardson N, Storey A, et al. Farming characteristics and self-reported health outcomes of Irish Farmers. Occup Med. 2018;68(3):199–202. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqy020.

- Guillien A, Soumagne T, Dalphin J-C, Degano B. COPD, airflow limitation and chronic bronchitis in farmers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(1):58–68. doi:10.1136/oemed-2018-105310.

- Nordgen TM, Charavaryamath C. Agriculture occupational exposures and factors affecting health effects. Agriculture Occupational Exposures and Factors Affecting Health Effects, Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;18(12):65–78. doi:10.1007/s11882-018-0820-8.

- Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. The New Public Health. Third ed. San Diego (CA): Elsevier; 2004.

- Stoleski S, Minov J, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, Mijakoski D, Atanasovska A, Bislimovska D. Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease associated with occupational exposure in dairy farmers – importance of job exposure matrices. Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(14):2350–2359. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2019.630.

- Soumagne T, Degano B, Guillien A, et al. Characterisation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in dairy farmers. Environ Res. 2020;188:109847. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109847.

- Farms.Com [Internet] (Canada): the Farmer’s Advocate; [cited 2021 Mar 6] Available from:https://www.farms.com/reflections-on-farm-and-food-history/historical-articles-archive/agriculture-as-a-profession.

- Reynolds SJ, Lundqvist P, Colosio C. International dairy health and safety. J Agromedicine. 2013;18(3):179–183. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2013.812771.

- Tual S, Clin B, Leveque-Morlais N, Raherison C, Baldi I, Lebailly P. Agricultural exposures and chronic bronchitis: findings from the AGRICAN (AGRIculture and CANcer) cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(9):539–545. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.06.005.

- Sigsgaard T, Basinas I, Doekes G, et al. Respiratory disease and allergy in farmers working with livestock: a EAACI position paper. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020;10(1):1–30. doi:10.1186/s13601-020-00334-x.

- Department of Agriculture: Food and Marine: Fact sheet on Irish agriculture [Internet]. (IRE). [cited 2020 Jan 21] Available from. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/3ec3a-fact-sheet-on-irish-agriculture-september-2020/#.

- The World Bank.org [Internet]. (Europe); [cited 2021 Mar 5]. Available from:https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/overview

- Pollock A, Campbell P, Cheyne J, et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11):1–161. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013779.

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–2126. doi:10.11124/JBIES-20-00167.

- Teagasc.ie [Internet] (IRE); [cited 2019 Nov 22]. Available FROM: https://www.teagasc.ie/media/website/publications/2017/NFS-2016-Final-Report.pdf.

- Sustainablefoodtrust.org [Internet] Holden (UK); [cited 2021 April 15]. Available from: https://sustainablefoodtrust.org/articles/what-defines-a-farmer-exploring-attitudes-to-scale-in-agriculture/

- Mazurek JM, White GE, Rodman C, Schleiff PL. Farm work-related asthma among US primary farm operators. J Agromedicine. 2015;20(1):31–42. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2014.976729.

- Hogan V, Noone R, Hayes JP, Coggins AM. The prevalence of respiratory symptoms in Irish dairy farmers. Ir Med J. 2018;111:698.

- Arinze JT, de Roos EW, Karimi L, Verhamme KMC, Stricker BH, Brusselle GG. Prevalence and incidence of, and risk factors for chronic cough in the adult population: the Rotterdam Study. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2):1–10. doi:10.1183/23120541.00300-2019.

- Marescaux A, Degano B, Soumagne T, Thaon I, Laplante J-J, Dalphin J-C. Impact of farm modernity on the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in dairy farmers. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73(2):127–133. doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102697.

- Meuwissen MPM, Ph F, Slijer T, et al. Impact of Covid-19 on farming systems in Europe through the lens of resilience thinking. Agric Syst. 2021;191:103152.

- McEwan K, Marchand L, Shang M, Bucknell D. Potential implications of COVID-19 on the Canadian pork industry. Can J Agric Econ. 2020;68(2):201–206. doi:10.1111/cjag.12236.

- Teagasc Agriculture and Food Development Authority [Internet] Carlow (IRE); [cited 2020 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.teagasc.ie/news–events/news/2020/impact-of-covid-19-on-far.php

- Weersink A, Von Massow M, Bannon N, et al. COVID-19 and the agri-food system in the United States and Canada. Agric Syst. 2021;188:103039. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103039.

- Akpinar-Elci M, Pasquale DK, Abrokwah M, Nguyen M, Elci OC. United airway disease among crop farmers. J Agromedicine. 2016;21(3):217–223. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1179239.

- Stoleski S, Minov J, Mijakoski D, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J. Chronic respiratory symptoms and lung function in agricultural workers – influence of exposure duration and smoking. Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(1):158–165. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.014.

- Gulec Balbay E, Toru U, Arbak P, Balbay O, Suner KO, Annakkaya AN. Respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function tests in security and safety products plant workers. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1883–1886.

- Kearney GD, Gallagher B, Shaw R. Respiratory protection behaviour and respiratory indices among Poultry House Workers on small, family-owned farms in North Carolina: a pilot project. J Agromedicine. 2016;21(2):136–143. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1143429.

- Li J, Li Y, Tian D, Yang H, Dong L, Zhu L. The association of self-reported respiratory system diseases with farming activity among farmers of greenhouse vegetables Int. J Med Res. 2019;47(7):3140–3150. doi:10.1177/0300060519852253.

- Hayes JP, Rooney J. The prevalence of respiratory symptoms among mushroom workers in Ireland. Occup Med. 2014;64(7):533–538. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqu110.

- Stoleski S, Minov J, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, Mijakoski D. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smoking dairy farmers, Open Respir. Med J. 2015;9(Suppl 1: M5):59–66. doi:10.2174/1874306401509010059.

- Viegas S, Faisca VM, Dias H, Clérigo A, Carolino E, Viegas C. Occupational exposure to poultry dust and effects on the respiratory system in workers. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2013;76(4–5):230–239. doi:10.1080/15287394.2013.757199.

- Basinas I, Cronin G, Hogan V, Sigsgaard T, Hayes J, Coggins AM. Exposure to inhalable dust, endotoxin and total volatile organic carbons on dairy farms using manual and automated feeding systems, Ann. Work Expo Health. 2017;61(3):344–355. doi:10.1093/annweh/wxw023.

- Gilbey SE, Selvey LA, Mead-Hunter R, et al. Occupational exposures to agricultural dust by Western Australian wheat-belt farmers during seeding operations. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;15(12):824–832. doi:10.1080/15459624.2018.1521973.

- Pfister H, Madec L, Le Cann P, et al. Factors determining the exposure of dairy farmers to thoracic organic dust. Environ Res. 2018;165:286–293. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.04.031.

- Rumchev K, Gilbey S, Mead-Hunter R, Selvey L, Netto K, Mullins B. Agricultural dust exposures and health and safety practices among western Australian wheatbelt farmers during harvest. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2019;16(24):5009. doi:10.3390/ijerph16245009.

- Basinas I, Sigsgaard T, Enderson M, et al. Exposure-affecting factors of dairy farmers’ exposure to inhalable dust and endotoxin. Ann Occup Hyg. 2014;58(6):707–723. doi:10.1093/annhyg/meu024.

- Garcia J, Bennett DH, Tancredi D, et al. Occupational exposure to particulate matter and endotoxin for California dairy workers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2013;216(1):56–62. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.04.001.

- Cushen B, Suliman I, Donoghue N, et al. High prevalence of obstructive lung disease in non-smoking farmers: the Irish farmers lung health study. Respir Med. 2016;115:13–19. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2016.04.006.

- Guillien A, Puyraveau M, Soumagne T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for COPD in farmers: a cross-sectional controlled study. Eur Clin Respir J. 2016;47(1):95–103. doi:10.1183/13993003.00153-2015.

- Jouneau S, Marette S, Robert AM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in dairy farmers: aIRBAg study. Environ Res. 2019;169:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.026.

- Dorribo V, Wild P, Pralong JA, et al. Respiratory health effects of fifteen years of improved collective protection in a wheat-processing worker population. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(4):647–654. doi:10.5604/12321966.1185768.

- Saglan Y, Bilge U, Oztas D, et al. Oztas D, et al.The prevalence of asthma and asthma-like symptoms among seasonal agricultural workers. Biomed Res Int. 2020;9:1–5. doi:10.1155/2020/3495272.

- Ali Tarar M, Hussain Salik M, Riaz M, et al. Effects of pesticides on male farmer’s health: a study of Muzaffar Garh. Pak J Agric Sci. 2019;56(4):1021–1030. doi:10.21162/PAKJAS/19.9157.

- Basinas I, Sigsgaard T, Kromhout H, Heederik D, Wouters IM, Schlünssen V. A comprehensive review of levels and determinants of personal exposure to dust and endotoxin in livestock farming. J Expo Sci Environ Epid. 2016;25(2):123–137. doi:10.1038/jes.2013.83.

- Central Statistics Office [Internet] (IRE); [cited 2022 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.cso.ie/en/search/?addsearch=farming%20genders