Saint Martín de Porres was born in late sixteenth-century Lima to a formerly enslaved and unmarried black mother and a Spanish father.Footnote1 When Martín died at the age of 59 in 1639, he left behind a local reputation as a humble Dominican religious servant with miraculous healing powers. Nineteen years after his death, the Dominican order opened a beatification case that was subsequently endorsed by King Philip IV and the Vatican, bolstered by pre-existing enthusiasm for the beatification case of Rose of Lima, the Creole beata who died twenty-two years before Martín in the viceregal capital.Footnote2 When Martín was finally canonized in 1962, Pope John XXIII declared him ‘the saint of racial justice,’ echoing language used by Peruvian president General Oscar Benavides in 1939 to refer to Martín as the ‘patron of social justice’ (Gjurinovic Canevaro Citation2012, 101; Cussen Citation2014, 196–97). Yet Martín’s contemporaries and those of the subsequent generation in Lima did not celebrate him as such in the seventeenth century. In fact, the varied ways that the earliest surviving portrayals of Martín depict his racialized social status deserve further examination, as they offer windows onto how, why, and to what effects images of black holiness were made and embraced in the mid-colonial period in Spanish America, an era typically associated with the solidification of skin-color based racial hierarchies.

Studies of Martín de Porres and his cult have yet to examine seriously one of the principal sources about him from the seventeenth century, the first edition of Dominican Creole Bernardo de Medina’s Vida prodigiosa del venerable siervo de Dios F. Martin de Porras, natural de Lima, published in Lima in 1673, because specialists had long considered the text lost or never actually printed.Footnote3 This first edition was in fact published two years before the well-known 1675 Madrid edition of Medina’s hagiography.Footnote4 While the narrative is identical in both editions, the 1673 Lima edition is distinct in that it includes an engraved portrait of Martín as its frontispiece () and significantly different frontmatter. As a corrective to scholarship on Martín and a point of dialogue with the history of images of black men and women in the Americas, this article examines the 1673 frontispiece portrait by the otherwise unknown artist José Martínez, comparing it to other engraved images of Martín from the seventeenth century as well as the accompanying poetic frontmatter to Medina’s 1673 hagiography. The comparison will demonstrate that the earliest dated portrait of Martín de Porres from Peru indexes the disparate racialized social statuses of Martín’s parents by making Martín into a visual and textual composite who could simultaneously embody black and white characteristics. This strategy, I will argue, represents an effort made by white Creole elites in Lima in the mid-to-late seventeenth century to fashion themselves before the larger Catholic world as inheritors of classical forms and successful evangelizers of the region’s dark-skinned populations.Footnote5

The portrait

Although there is a handful of extant paintings of Martín de Porres considered to have been made in the seventeenth century, none is dated and none has been subjected to scholarly examination in order to more carefully estimate its date of composition.Footnote6 For example, while the oil-on-copper double portrait of Juan Macías and Martín de Porres on display at the Santuario de Santa Rosa in LimaFootnote7is popularly considered to have been made during Martín’s life (Floyd Citation2017), in publications scholars have only voiced suspicions that it was made by an artist who had known Martín because of the specificity of the portrait compared to later examples that show him darker and younger.Footnote8 Further complicating efforts to date the double portrait, its legend presents Martín and Juan Macías as ‘beatos,’ indicating that the legend, at least, was composed or over-painted after 1837 when both men were beatified. As a result, the engraved portrait of Martín by José Martínez printed with Medina’s hagiography in 1673 is the earliest surviving dated image of Martín de Porres from Peru.

Martínez’s portrait () presents Martín in relation to his racially determined position within his convent’s hierarchy, his religiously exemplary behavior, and his city of birth, Lima. Dressed in a simple white tunic and hoodless black cape, Martín wears the habit of a Dominican donado, a religious servant in early modern convents who occupied a subordinate status to priests and lay brothers (Tardieu Citation1997, 1:385–93).Footnote9 A step above non-religious servants, donados swore some vows to God, but were still expected to perform more manual labor to support their spiritual communities than lay brothers. Because individuals of African descent were prohibited from becoming priests or lay brothers in colonial Spanish American convents, Martín’s clothing places him in the highest religious position available to someone born to a black parent during this period.

The physical features Martín inherited from his black mother are less obvious in the printed image than the sartorial display of his position as a donado. Martínez used some hatching to darken Martín’s face and hands, but it is unclear whether the lines were intended to produce the effect of a shadow or to signal a skin tone darker than that of the white tunic draped across his body. If one were to interpret the diagonal and vertical parallel hatching on the sides of his forehead, cheeks, and hands only as shading, the technique would demonstrate the artist’s adherence to a commonplace in early modern engravings and etchings that reserves hatching for depth-enhancing shadows rather than skin color (see Brewer-García Citation2016, 113–14). An example of such a strategy appears in Sadeler’s engraved print of the Epiphany from 1581 (), an image copied multiple times in mid-colonial Andean paintings. In Sadeler’s image, the black magus’s racial difference compared to the other two magi appears only in relation to his stereotypically round nose and thick lips, rather than a marked skin tone. Viewed alongside such a precedent, Martín’s pointed nose and thin lips in Martínez’s portrait might be read as indicators of a physical appearance entirely inherited from his white father rather than his black mother. Yet a competing tradition existed in which artists did employ hatching to index black skin tones in engraved images, as shown in the image of Benedict of Palermo in Pietro Tognoletto’s hagiography of the would-be Franciscan saint from 1667 ().Footnote10 Viewed in dialogue with this competing precedent, the lines on Martín’s face and hands in Martínez’s portrait could indeed mark a dark skin tone. To further support this interpretation, the cross-hatching representing Martín’s closely cut thick hair contrast significantly with the wispy vertical lines of the straight hair of Creole poet Pedro de Oña in the anonymous portrait printed in Lima in 1596 (). The distinction suggests Martín’s hair was thick and curly, attributes identified by Sebastián de Covarrubias in 1611 as common to black men and women (f. 435r, s.v. geta). The horizontal lines on Martín’s forehead that I interpret as wrinkles might have been intended as further indicators of his physical attributes inherited from his black mother, as Covarrubias includes ‘frentes c[on] muchas rayas’ [foreheads with many lines] as a common marker of black men and women (ibid.). Through the hatching on Martín’s face, hands, and hair and his donado habit, seventeenth-century viewers of Martínez’s engraved image would have been encouraged to see in Martín some physical attributes inherited from his black mother. I thus argue that, however subtly, Martínez’s portrait attempts to display the coexistence of features inherited from both of Martín’s parents: an individual with a nose and mouth like his white father’s and the skin tone and hair like his black mother’s.

Figure 2. Johann Sadeler, after Martin de Vos’s design, ‘Aanbidding der Koningen. Gebborte en eerste jaren van Christus’ (Cologne: Johann Sadeler, 1581). Engraved print on paper. Photo courtesy of Rijksmuseum.

Figure 3. Anonymous, P.F. Bendictus a S. Fratello, in Pietro Tognolleto’s Paradiso serafico del fertilissimo regno di Sicilia (Palermo: Domenico d’Anselmo, 1667). Engraved print on paper. Photo courtesy of St. Bonaventure University. Holy Name Collection.

Figure 4. Anonymous, Portrait of Pedro de Oña in Pedro de Oña’s Arauco domado (Lima: Antonio Ricardo, 1596). Woodcut print on paper. Photo courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Martínez’s portrait combines Martín’s distinct sets of physical features with a panoply of devices to signal his exemplary Christian virtue. Echoing the cross hanging from the rosary around Martín’s neck, the cincture knotted at his waist forms a perpendicular line across his body with the seam of his tightly clasped tunic. He demurely looks at the viewer, his lips pursed in silence. His gaunt face marks an asceticism that situates him in relation to the spiritual capital of a disciplined religious servant. The broom he holds in his right hand points upwards as if a torch, allowing it to appear in the three-quarter-length frame. The manner of grasping the broomstick also alludes to how subjects in religious portraiture of the period bear martyr’s palms, visually indexing Martín’s spiritual embrace of the humble domestic labor expected of a donado. This instrument of cleanliness also casts him as someone who could keep worldly and spiritual filth at bay. Meanwhile Martín’s left forearm carries a basket of bread to give to the poor and a little container filled with powders for his healing work hangs from his waist, representing his capacity to cure sicknesses and alleviate pain.Footnote11 His status as an exemplary religious servant is further punctuated by the cartouche shaped as a Roman funerary relief that presents his name and religious affiliation above a citation from the Divine Office for the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours (d. 397) that reads: ‘Martinus hic pauper et modicus caelum dives ingreditur’ [Martin here poor and humble comes into heavenly riches]. Finally, the braided straw of the oval border echoes the organic materials used in the basket and broomstick in the image, literally framing Martín in relation to materials used in the manual labor he performed for others.

The portrait mobilizes the aforementioned visual cues alongside details that depict Martín in relation to Lima, the city where he was born and for which he was known to have cared as a religious guide, alms giver, and healer. The rosary in Martín’s right hand ties him to the Dominican convent of Nuestra Señora del Rosario in Lima where he lived for most of his life.Footnote12 In the background to his left, a partially open door offers a view of a voluminous deciduous tree that could be from one of his convent’s gardens or, more likely, the Dominican hacienda of Limatambo just outside the city (at present in the neighborhood of San Isidro) where Martín grew medicinal herbs and retrieved the convent’s bread that he distributed in the city (Medina Citation1673, f. 18r). Trees such as the one in the image would have been unlikely in the Andean highlands during this period, and therefore its placement in the background could underscore Martín’s ties to the lowland area of Lima. The open door and view could also represent Martín’s reputation as a possessor of the divine gift of bi-location (the ability to be in two locations at once), which Martín used to travel between Lima and the hacienda of Limatambo to tend to others’ material and spiritual needs (Medina Citation1673, ff. 71r–72r). For viewers of the image in Peru, the references to Lima would have been more obvious than for viewers in more remote locations. For those other viewers, the portrait’s subject’s ties to Lima would have come more from the context of its publication as the frontispiece to a book published in that city, announcing in its title that its subject was ‘natural de Lima’ [born in Lima].

What models did Martínez use to compose this image? While Martínez’s engraved portrait is the earliest surviving image of a spiritually venerable individual of African descent from Spanish America, it is not the first known to have been made. The earliest mention of such an image appears at the end of a 1646 hagiography about a ‘mulata parda’ [dark-skinned mulata] named Estefanía de San José who died in Lima, Peru in 1645.Footnote13 The morning after her death, a group of individuals devoted to her commissioned a portrait rendered in front of her dead body.Footnote14 Estefanía’s portrait no longer exists so we do not know its medium, but its mention functions in the hagiography as proof of a profound appreciation for her at the time of her death and a shared desire (along with her elaborate funerary rites and the hagiography itself) to preserve her memory among the living. Such a use aligns with Covarrubias’s definition of the portrait as a ‘figura contrahecha de alguna persona principal y de cu[en]ta, cuya efigie y semejança, es justo quede por memoria a los siglos venideros’ [counterfeit image of some principal person of account, whose effigy and likeness should be preserved in memory for centuries to come] (1611, f. 11r [i.e. 613r], s.v. retrato).Footnote15

The next known reference to a portrait of a spiritually venerable individual of African descent from the Americas appears fourteen years later in Martín de Porres’s first beatification inquest in Lima in 1660. Three different witnesses interviewed that year explain that in the ensuing years after Martín’s death two portraits of him kept in elite households in Lima had miraculously healed individuals in pain (Proceso Citation1960, 164, 166, 188).Footnote16 Unlike the reference to the time and place of the rendering of Estefanía’s portrait, we do not know if these portraits were made from life, from his dead body, from memory, or from a copy of any of the above. It is possible the portraits mentioned in 1660 were two different versions of the same image. It is even possible that they refer to an earlier printing of Martínez’s portrait as the plate of the portrait printed with the 1673 hagiography is not dated itself. The Dominican convent of El Rosario sold single-sheet printed portraits of Rose of Lima in the years following her death as a means of fundraising for her beatification campaign, and so it is likely similar prints were sold for Martín’s case (Cussen Citation2014, 161, 259–60 n.26). These mentions of the lost early portraits of Estefanía and Martín signal the existence of antecedents to Martínez’s image, indicating that the 1673 image joined (and potentially shared visual language with) an already existing set of portraits of spiritually venerable and racially mixed individuals of African descent in the city.

The descriptions of these images of spiritually venerable individuals of African descent in Lima as well as Martínez’s portrait itself invite us to ask why individuals of African descent became subjects of religious portraiture at a time when the individuals themselves could not even aspire to become nuns or priests. Scholars seeking to answer this and similar questions about the portrayal of black subjects in early modern visual culture have proposed divergent theories based on different sets of images. I will review some of the most relevant here as a means of introducing what is distinct about Martínez’s 1673 portrait.

The black portrait subject

Four principal reasons have been given for the emergence of individuals of African descent in secular portraiture of the early modern period. The first relates to the phenomenon of the black page in portraits of elite white sitters, such as Titian’s painting of Laura Dianti (c. 1523), which circulated widely in the subsequent century in engraved copies like Sadeler's early seventeenth-century rendition. Through the age, placement, and gaze of the black page who looks up in admiration, the motif serves to index the elevated social status and benevolence of the white sitter (Lugo-Ortiz Citation2012, 6–8; McGrath Citation2012, 18–20, 30–32, 37).Footnote17 The second reason relates to portraits such as Diego Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja (1650) and Marie-Guillemine de Laville-Leroulx’s Portrait d’une Négresse (1800), which use their black subjects to showcase the artists’ skill in rendering dark skin tones with oil paints (Lugo-Ortiz Citation2012; Fracchia Citation2013). Citing both reasons, Agnes Lugo-Ortiz notes that secular portraits of black men and women in the early modern period focus on elevating the status of the white figures inside or outside of the frame, rather than portraying the authority or virtue of the black subjects themselves (Citation2012). Two other motivations for including non-white figures in secular portraiture during this period include a fascination with non-conventional subjects and a celebration of the European ability to civilize barbarous non-European populations, as argued in Rebecca P. Brienen’s interpretation of Albert Eckhout’s seventeenth-century ethnographic paintings of black men and women from Brazil (Citation2013).

Alternative theories have been proposed by scholars examining religious depictions of black individuals. For example, scholarship on the depiction of the black magus from late medieval and early modern Europe has noted that the black magus was a way of indexing and celebrating Christianity’s universal promise to save even the dark-skinned populations of the world (Kaplan Citation2010; Koerner Citation2010; Brewer-García Citation2016). While the earliest known visual examples date to the fourteenth century, the iconography truly proliferated throughout Europe in the late fifteenth century and was eventually embraced in Iberian visual culture by the middle of the sixteenth century (Kaplan Citation2010; Stoichita Citation2010; Fracchia Citation2019, 60–66). Another theory related to the emergence of black subjects in religious portraiture focuses on the evangelical uses of such images amidst the boom in the Iberian and transatlantic slave trade to Spanish America in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Erin Rowe’s study of the spread of the cults of Antonio de Noto and Benedict of Palermo throughout the Iberian world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Citation2019) argues that images of these black holy figures circulated throughout the Mediterranean and Atlantic with Iberian missionaries as strategies to evangelize enslaved sub-Saharan black men and women in Iberian territories. According to Rowe, cults devoted to the would-be black saints were then adopted, adapted, and celebrated by black confraternities dedicated to them in the eighteenth century.

Yet another theory regarding the spread of early modern images of black holy figures appears in scholarship on the Virgin of Guadalupe. The medieval cult to the black-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe of Extremadura arrived in New Spain in the sixteenth century where it transformed in relation to new miracles performed there, the most famous being the imprinting of her likeness on the tilma of the Indigenous man Juan Diego. Images of the Mexican Guadalupe became standardized by the seventeenth century as brown-skinned, linking her to what was perceived as her special favor for the people of New Spain (Peterson Citation2014). Significantly, the images of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe garnered a wider and more varied audience in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than those of the black saints examined by Rowe. That is, images of Guadalupe were not just appreciated by Indigenous populations of the viceroyalty or used exclusively as an evangelical tool for them. Instead, by the mid-to-late seventeenth century, white Creole authors celebrated and helped advocate the legitimacy of the popular cult as a way of articulating their own spiritually devout Catholic identity distinct from that of the Spanish metropole (Brading Citation1991, 343–61; Citation2001, 114–20).Footnote18 In New Spain, the brown-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe was thus seized as an opportunity for Creoles in mid-to-late seventeenth-century New Spain to rewrite the spiritual conquest narrative of the previous century and to present themselves as distinct from and yet spiritually equal to their Peninsular counterparts.

Like the case of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe, surviving images of Martín de Porres from the Andes in the late seventeenth century do not appear to have been explicitly or exclusively used to evangelize dark-skinned populations.Footnote19 black confraternities, for example, do not appear in documentation as participants in the spreading of Martín’s fame in Lima before his beatification case began. Instead, surviving images and texts made in Lima and Europe in the first century after his death show that Creoles in Lima were the principal promoters of Martín’s cult (Cussen Citation2014, 3, 10–12).

Contrary to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century images of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe which typically portray her as the only or the superior figure in the frame, most of the surviving engraved images of Martín from the seventeenth century position him in an inferior position in group portraits displaying a tiered hierarchy of sanctity in which different strata of Peruvian society are provided their own saintly models.Footnote20 An image composed in Rome by Maltese artist Melchiorre Cafà sometime between 1665 and 1667 provides the earliest example of that visual program (). The image was commissioned by the Peruvian Creole Dominican priest Antonio González de Acuña (1620–1682), who was sent by his order to Madrid in 1658 and then Rome in 1661 to advocate the beatifications of Rose of Lima, Martín de Porres, Vicente de Bernedo, and Juan Macías (Hampe Martínez Citation1998, 62; Weddigen Citation2018, 104).

Figure 5. Albertus Clouwet da Melchiorre Cafà, ‘Madonna col bambino e la Beata Rosa di Lima’ (c. 1667). Engraved print on paper. Photo courtesy of the Albertina Library, Vienna.

Cafá’s image presents Martín as the humblest spiritual treasure mined by the Dominican order in Peru to that date. In the composition, Martín’s upper body emerges from the middle ground on Rose’s right hand side. With his face half cast in shadows and in profile, he gazes at Rose, rather than looking higher at the Virgin and child above her as the other named figures in the portrait do. Martín is further distinguished from the rest by his comparably simple donado dress and his untonsured, uncovered head which contrast with the tonsures, scapulars, and cappe of Saint Dominic to the bottom left, Padre Vicente de Bernedo in the center, and lay brother Juan Macías to the right. Martín and Juan Macías also appear much younger than Saint Dominic and Vicente de Bernedo, denoting their subordinate statuses. The composition suggests that Rose was an example of holiness for non-European populations of the Andes, who in looking up to her receive the light of God in their own way. These strategies demonstrate a repurposing of the visual language of the black page motif from secular portraiture to depict a tiered notion of exemplary religious subjects emerging from a racially stratified colonial world.Footnote21

None of the aforementioned theories and images, however, adequately accounts for Martínez’s portrait (). In this portrait, an older Martín appears alone, positioned authoritatively in the middle of the three-quarter-length portrait, gazing slightly down at the viewer. Through his positioning, his lightly wrinkled forehead, and the direction of his gaze, Martín displays a subjectivity denied to the young servile follower of Saint Rose from Cafà’s image.Footnote22 Martínez further marks Martín’s important status by depicting him with a set of characteristics associated with white aristocratic men in contemporary European portraiture: a prominent chin and mustache.Footnote23 In fact, Martín’s aristocratic facial features in Martínez’s portrait echo the chin and mustache given to Pedro de Oña in the 1596 woodcut portrait printed as the frontispiece in Oña’s Arauco domado, a poem celebrating the Peruvian conquest of Chile on behalf of the Spanish Empire (). Emily Floyd’s analysis of Oña’s portrait argues that its composition and positioning at the beginning of the poem make a claim for the cultural authority and belonging of Lima in the Iberian world of letters at the turn of the seventeenth century (Citation2019, 365). By using similar facial features to depict Martín, Martínez invokes Martín’s reputation as a venerable servant of God as well as an inheritor of his father’s supposed Spanish nobility.

And yet, other aspects of Martínez’s image exist in tension with the aforementioned elements. Martín’s already referenced darkened skin tone and donado dress mark a lower status than that of a white Creole. Furthermore, in comparing the image to Jean-Baptiste Barbé’s undated engraved portrait of Rose of Lima (Mujica Pinilla Citation2001, 184), we see that rather than a church interior, Martínez’s portrait displays a bare, modest background that could be a domestic space in Limatambo or the Dominican convent where Martín was known to sweep (Medina Citation1673, ff. 29v, 51v, 52v). By superimposing features associated with the distinct appearances and statuses of his black mother and his Spanish father in the same figure, Martínez’s portrait presents Martín as a composite.

The composite

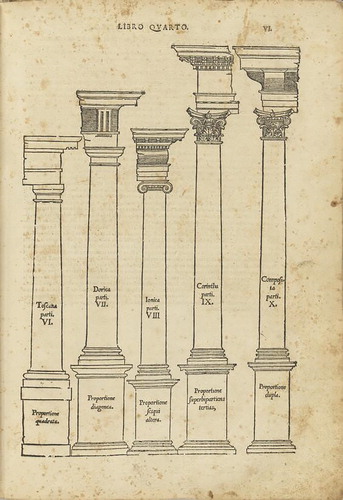

By composite, I mean that Martín’s figure in the 1673 engraving is composed of parts whose distinct identities remain legible in their combination in ways that depart from the notion of hybridity common to studies of racial formations in colonial Latin America (as will be discussed further below). Covarrubias’s definition of the verb ‘componer’ [to compose] alludes to such a combination when explaining it as ‘poner juntamente una cosa con otra’ [to put one thing next to another] (Citation1611, f. 229r). Rather than blending the items so as to render them both unrecognizable or collapsing one into the other, the composite suggests a juxtaposition that keeps each item distinct. This meaning is apparent in the architectural use of the term ‘compuesto’ [composite], which became current in mid-sixteenth-century Iberia due to the wide circulation of Sebastiano Serlio’s architectural treatises.Footnote24 After describing the four classical architectural styles of ancient Rome, each with its corresponding column, Serlio defines the composite as: ‘Una quasi quinta manera de columna mezclada de ellas mismas, aprobada con la autoridad de las obras Romanas antiguas … ’ [An almost fifth kind of column, a combination the others, approved with the authority of ancient Roman works] (Citation1573, libro IV, cap. 9, f. 63v). The mixture of the composite as illustrated in the prints accompanying Serlio’s explanation entails a superimposition of Ionic volutes and Corinthian foliage in the column capital (). This mixture is prudent, according to Serlio, because it respects rules of proportion: ‘tener si[em]pre respecto a no corromper el subjecto de las cosas, ni su origen’ [to be always careful not to corrupt the subject of the things [combined], nor their origin] (ibid.). The formal propriety mentioned in Serlio’s description resonates with Covarrubias’s mention of the moral propriety of the composite, referenced as ‘compostura’ [composure] and defined as ‘aseo de las cosas; la mesura y modestia en la persona’ [cleanliness in things; temperateness and modesty in a person].Footnote25 This set of definitions and associations from the early modern Iberian world suggests that the composite was a way of conceiving of a mixed entity that was aesthetically pleasing and morally proper rather than a degenerate, illegibly blended, or monstrous hybrid.

Figure 6. In Sebastiano Serlio’s Tercero y quarto libro de arquitectura. Trans. Francisco de Villalpando (Toledo: Juan de Ayala, 1573). Engraved print on paper. Photo courtesy of Avery Library, Columbia University.

Two engraved images of Martín from later in the seventeenth century are helpful comparanda as competing, non-composite, ways of visualizing Martín during this period. These are Bernard Balliu’s 1681 engraving from Rome () and Benoit Thiboust’s 1696 engraving from Venice (). (In both Balliu’s and Thiboust’s images, Martín is the figure on the bottom right, kneeling closest to the ground.)Footnote26 Balliu’s image does not index black features in Martín’s physical appearance other than his donado dress. Meanwhile Thiboust’s image () is an example of an effort to use only stereotypical features common in European engravings to portray black men. That is, in Thiboust’s engraving, Martín has the rounded facial features of de Vos’s black magus from Sadeler’s 1581 engraving () and emphasized hatching to denote the dark skin of Benedict of Palermo from the engraving accompanying Tognoletto’s 1667 hagiography ().

Figure 7. Bernard Balliu, Saint Rose of Lima, Juan Macías, and Martín de Porres in Juan Meléndez’s Tesoros verdaderos de las Indias (Rome: Nicolás Angel Tinassio, 1681–1682). Photo courtesy of Harvard University’s Houghton Library.

Figure 8. Benoit Thiboust, ‘Los ven[erables] Macias, Bernedo y Porres.’ In Alonso Manrique’s Retrato de la perfeccion christiana (Venice: Francisco Gropo, 1696). Photo courtesy of the British Library.

![Figure 8. Benoit Thiboust, ‘Los ven[erables] Macias, Bernedo y Porres.’ In Alonso Manrique’s Retrato de la perfeccion christiana (Venice: Francisco Gropo, 1696). Photo courtesy of the British Library.](/cms/asset/3fb5debf-51b7-4f7b-bfb5-20d2a9be3be1/ccla_a_1912485_f0008_oc.jpg)

Martínez’s 1673 portrait differs stylistically and compositionally from these later engravings. Unlike Balliu’s image of Martín as a white man, Martínez’s portrait includes hatching to suggest a dark skin and closely-cut thick curly hair, physical attributes I argued earlier would have been interpreted as coming from Martín’s black mother. And unlike Thiboust’s image of Martín as a black man, in Martínez’s portrait Martín’s mustache, lips, and small pointed nose signal physical attributes indexing his inheritance of physical attributes of his white father, too. Seen in contrast to these later images and the precedents referenced above, the composite approach in Martínez’s visual portrait stands out more prominently.

The cartouche and Saint Martin of Tours

The final way Martínez’s image presents Martín as a composite is through invoking the iconographic and song tradition related to a well-established saint who shared his name—Martin of Tours. The cartouche at the bottom of the oval frame (‘Martinus hic pauper et modicus caelum dives ingreditur’ [Martin here poor and humble comes into heavenly riches]) is a citation from a line sung yearly as a responsory at Matins of the Divine Office on 11 November, the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours.Footnote27 The cartouche’s allusion to Martin of Tours establishes an analogy between Martín and Martin that commented on and elaborated the portrait’s composite construction for the lay brothers and priests who read the hagiography at its time of publication.

Saint Martin of Tours is a saint from the fourth-century Roman world, born in a territory corresponding to today’s Hungary, but associated with the city of Tours in Gaul where he became a bishop after his conversion.Footnote28 The famous turning point of Saint Martin’s life, according to Sulpicius Severus’s De vita Beati Martini (c. 397), occurred when Martin was traveling on horseback in Amiens as a young Roman soldier. Approached by a naked beggar who asked for his assistance, Martin used his sword to cut his cloak in half, giving one half to the beggar and keeping the other for himself. That night, Martin dreamed that the beggar was actually Christ and when he awoke he decided to renounce his life as a soldier to dedicate himself to God (Citation1866, 112). Three of the readings from Matins for Saint Martin’s feast day come from Sulpicius Severus’s narrative (Breviarium Citation1592, 863). The line cited in the cartouche in Martínez’s portrait is the sung responsory to the eighth reading of Matins for Saint Martin’s feast day (idem, 863–64),Footnote29 which appears at a culminating moment in the third nocturn that turns from a general lesson about the illuminating power of faith to a final invocation of Martin. Due to its placement at the end of the Matins of the Divine Office for Saint Martin of Tours, the responsory cited in the cartouche serves as an epitome of the entire lesson about Martin. It is thus a particularly representative way to sonically allude to the Old World saint and his iconography in relation to the image of Martín de Porres.

The allusion to Saint Martin of Tours in the cartouche encouraged viewers to contemplate the image in relation to the iconography of the European saint common in visual culture of the early modern Iberian world. The most well-known example of this iconographic program appears in El Greco’s late sixteenth-century painting () that addresses the distinction between the knight and the beggar of the cloak-cutting scene through the positioning of Martin as a light colored and finely dressed figure on horseback above a darkly colored, injured, and nearly naked beggar. Earlier engraved images with similar iconography printed in Antwerp, such as Anton Wierix’s (), had reached Lima by the end of the sixteenth century. These prints were subsequently copied in paintings and sculpture in the Andes, numerous examples of which survive today. For example, in the Church of El Rosario in Lima, a sculpture of Saint Martin is the first panel on the left of the row of sculpted wood choir seats installed in the sixteenth century (Prado Heuderbert Citation1996, 72; Busto del Duthurburu Citation1992, 389). While the unpainted medium of the wood sculpture does not allow for an explicit color distinction between the two figures, the composition still follows Wierix’s hierarchical placement of the knight on horseback above the beggar. In another adaptation of Wierix’s engraving, an anonymous Cuzco-school painting from mid-to-late seventeenth century at the Museo de Arte de Lima combines both formal aspects, using color and placement to emphasize the distinct statuses of the knight and the beggar (Kusunoki and Wuffarden Citation2016, 102–3). Similar compositional strategies are adopted in other contemporary examples found in Lima, Cuzco, La Paz, and Bogota, suggesting the ubiquity of the iconographic program throughout the seventeenth-century Andes.Footnote30

Figure 9. El Greco, San Martín y el mendigo [c. 1599]. Oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art.

![Figure 9. El Greco, San Martín y el mendigo [c. 1599]. Oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art.](/cms/asset/a2987428-ea0a-45b9-8090-eb081afa9121/ccla_a_1912485_f0009_oc.jpg)

Figure 10. Anton Wierix, after Martin de Vos’s design, ‘Martin de Tours cutting his cloak.’ 1581. Engraved print on paper. Photo courtesy of the Albertina Library, Vienna.

The cartouche in Martínez’s engraving encourages its viewers to perceive Martín as a composite of both the noble knight and the humble beggar in one figure. His aristocratic facial features (mustache included) identify him with the knight, while his subtly darkened skin and uncovered head identify him with the beggar. Rather than wielding a sword on horseback as his namesake, this more modest Martín solemnly grasps a broom and a rosary. But like the noble knight, Martín de Porres still offers assistance to the needy with the bread he carries to feed the hungry. In citing the Divine Office’s celebration of Martin of Tours, the cartouche presents an allegorical reading of the limeño Martín as a composite born of exemplary allusion rather than illegitimate miscegenation.

Such visual and textual interpretations of Martín as a composite figure offered alternatives to contemporary ways of conceiving of mixed entities such as the hybrid and the amalgam, respectively tied to discourses of animal husbandry and metallurgy.Footnote31 The notion of the hybrid, in particular, was frequently used to describe mestizos and mulatos in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as products of illegitimate and degenerate sexual pairings. Such a stigma is apparent, for example, in Covarrubias’s definition of mulato: ‘El que es hijo de negra y de hombre blanco, o al revés: y por ser mezcla extraordinaria la compararon a la naturaleza del mulo’ [he who is the son of a black woman and a white man, or the opposite; and because it is an uncommon mixture they compared it to the nature of the mule] (Citation1611, f. 558r).Footnote32 Spanish jurist Solórzano y Pereira adapted this definition for the New World context in his treatise composed in Lima during the first half of the seventeenth century, stating that the stigma of mixture itself should not exclude legitimate mulatos from posts requiring limpieza (Hill Citation2004, 242).Footnote33 Despite such clarifications, sources from the late-sixteenth through the seventeenth centuries consistently show that Peninsular Spaniards and Creoles generally considered mulatos to be persons of uncertain affiliations and behavior who, on the whole, required monitoring and physical discipline to avoid impropriety or social upheaval (Ares Queija Citation1997; Citation2000; Cussen Citation2014, 24–25).

To further understand the stigmas related to mulatos in mid-colonial Peru that Martínez’s image had to negotiate, it helps to briefly survey the context in which the image was produced. Half of Lima’s inhabitants were reported in parish census records as black or mulato for most of the seventeenth century (Bowser Citation1974, 337–41). While sometimes black and mulato individuals of Lima were counted separately in these records, in general they were grouped together (apart from Spaniards and indios). Scholars have noted that in response to such treatment, mulatos in mid-to-late seventeenth-century Peru sometimes appear in legal documents attempting to separate themselves from other black populations by claiming more civility based on their Spanish lineage (Jouve Martín Citation2007, 186–87; Graubart Citation2012, 52–54; Cussen Citation2014, 21). The emergence of the term pardo (grey-colored) as a euphemism for mulato in the mid seventeenth century (Schwartz and Salomon Citation1999) might in fact reflect linguistic efforts taken by mulatos to distance themselves from some of those stigmas.Footnote34 Despite such efforts, however, individuals with known mixed African and Spanish ancestry were still excluded from lay confraternities, guilds, educational opportunities, and professional posts requiring limpieza de sangre in mid-colonial Peru (Graubart Citation2012, 48).Footnote35 In addition, all African-descended men and women in seventeenth-century Lima—including mulatos—bore the possible association of being enslaved or related to someone who was (Hill Citation2004, 243).Footnote36

Instead of activating the aforementioned stigmas, Martínez’s portrait of Martín resorts to the composite, a concept emerging from classical architectural discourse, a discourse which resonates with the ‘edifying’ effect images and stories of saints were supposed to have on their viewers and readers. By keeping markers of blackness and whiteness distinct and legible in the image, Martínez’s portrait selectively avoids associating Martín with language tied to degenerate hybridity and impropriety common in the seventeenth century to refer to racially mixed individuals.

Doubling in Medina’s prefatory poems

Two of the prefatory poems to the first edition of Medina’s hagiography develop a different but complementary connection between Martín and Martin of Tours than the one invoked in Martínez’s image. Instead of presenting Martín as a composite of both characters from the Martin of Tours’s iconography, the poems present Martín as a New World double of Martin of Tours. Medina’s ‘Redondilla’ does so by focusing entirely on Martin of Tours’s cape-cutting episode:

De una capa partio dos [From one cape, Martin made two

Martin, para Dios, viviendo; for God, when alive;

y aqueste Martin muriendo, and this Martin, when dead,

tambien partio para Dios. Also left, for God.]

The ideological implications of this doubling appear in another prefatory poem from the first edition of the hagiography that glosses the line from the Divine Office for Saint Martin of Tours from Martínez’s engraving’s cartouche. Titled ‘Romance del autor en elogio del siervo De Dios Fr. Martin de Porras’ [Romance of the author in praise of the servant of God Fr. Martin de Porras], the poem presents Martín as a lowly worldly vassal with a lofty heavenly destiny:

No ay cetros para con Dios, [There are no scepters for God,

no ay poder, ni magestad, no power, no majesty,

que para Dios es lo menos, for what is least important for God

lo que en el mundo es lo mas. is most important for the world.

En una mesma balança The same scale measures

el Rey, y el vassallo estan, the king and the vassal,

que respeto de Dios, todos who, according to God,

son vassallos por igual. are equally his vassals.

[…]

Mas es, quien parece menos, He who appears less is more,

menos, quien parece mas: he who appears more is less.

no muere, quien vive bien, He who lives well does not die,

no vive, quien vive mal. he who lives badly does not live.

Si el Principe se condena, If the Prince condemns himself,

quien es menos? Si se va who is worth less? If the pauper

al cielo el pobre: dezidme, goes to heaven, tell me,

quien mas que el pobre será? who could be worthier than him?

Poned atentos los ojos Gaze attentively

en este vivo exemplar, on this vibrant example:

pobre, humilde, y abatido; poor, humble, lowly.

es forçoso, que digais: It is necessary that you say:

Viendolo un pardo al vivir, Seeing him a pardo when alive,

y tan santo al espirar, and so saintly in death.

vivo, no pudo ser menos, Alive, he could not have been worth less.

muerto, no puede ser mas. Dead, he could not be worth more.]

Similar humble-yet-virtuous posturing appears in some of the Creole celebrations of Rose of Lima (Meléndez Citation1681–Citation1682; Vargas Lugo Citation1976; Hampe Martínez Citation1998).Footnote38 The humility referenced in the case of Rose, however, was not one associated with her color but one related to her birth in a faraway land and to her identity as a lay beata born to a family of modest means.Footnote39 Like contemporary Creole efforts to praise Lima’s spiritual worth through Rose in the mid-to-late seventeenth century, Medina’s poem from 1673 spins the allusion in Martínez’s portrait to the iconography of Martin of Tours into a conceit about Lima’s valuable place within the Iberian empire. What is novel about Medina’s approach is that it uses a donado of African and European descent as its subject to represent the city’s spiritual worth before the world.Footnote40

Medina’s effort to use Martín to praise Lima is reinforced soon after in the prologue to the reader in the 1673 edition where Medina declares that he offers up Martín’s story for the following purpose: ‘Para credito de su patria, y mia, pues pretendiendo la Republica hazer a sus ciudadanos virtuosos, según Aristoteles en sus Politicos; se ven en el siervo de Dios logrados sus intentos’ [As a credit to his homeland, and mine, for if the Republic’s efforts should be to make its citizens virtuous, as Aristotle says in his Politics, then the achievement of its intentions can be seen in this servant of God] (Citation1673, Prologo al letor [iii]). The reference to a shared patria with his text’s subject displays Medina’s self-identification with a homeland conceived narrowly as Lima and more broadly as Peru.Footnote41 Medina thus celebrates that Lima’s virtuous Creoles could civilize ‘even’ someone as low in earthly hierarchies as Martín. Considered together, Medina’s frontmatter poems present Martín as a limeño double of a popular European saint whom the spiritual laborers of the Dominican order and the greater urban environment of Lima helped shape.

By invoking Martín’s earthly body as solely base in nature, Medina’s ‘Romance’ complements the strategy adopted in Medina’s hagiography to parse Martín’s black and white characteristics, aligning the former with his base body and the latter with his exemplary soul. For example, to specify how Martín embodied the status of each of his parents, early in the narrative Medina declares: ‘Fue pardo, como dizen vulgarmente, no blanco en el color, quando lo era de la admiraciõ de todos’ [He was dark-skinned, as they say vulgarly, not white in color, though he was a white target of the admiration of all] (Citation1673, f. 3r). Medina’s play on ‘blanco’ in this passage is only apparent in Spanish where it means both the color white and a target. The pun activates both meanings, affirming, like Medina’s ‘Romance,’ an identification between blackness and low worldly worth.Footnote42

While it is true that Medina also cites Paul in Galatians 3:28 to declare the ultimate irrelevance of one’s worldly physical appearance to one’s spiritual worth (Citation1673, f. 3r/v), before and after that declaration in Medina’s narrative, Medina refers to blackness, whether physical or symbolic, to mark Martín’s base nature from which Medina states he was exceptionally pardoned (Brewer-García Citation2012). As a result, rather than questioning the spiritual relevance or legitimacy of worldly racial hierarchies, Medina’s narrative reifies them by celebrating Martín as a dark man with an exceptionally white soul. The racial hierarchy endorsed by such language appears saliently in Medina’s description of Martín’s acts of pious self-punishment, which Medina glosses as Martín’s white soul disciplining his dark body:

Para [que] se sugete, pues, el cuerpo, como esclavo, al alma, como a señora, es necessaria en el camino de la virtud la penitencia. El venerable hermano Fr Martin, ent[en]diendo la importancia deste negocio, tomò la mortificaciõ tan a su cargo, que se hacia increible su rigor, y parecia que de penitencia saludable pasaba a sangrienta crueldad, y al parecer de los hombres no era penit[en]te que se mortificava por sus culpas, sino verdugo fiero, que tomava vengança de si mesmo … .

[So that the body like a slave is subjected to the soul like a slaveowner, penitence is necessary in the road to virtue. The venerable brother fray Martín, understanding the importance of this business, embraced mortification to such an extreme that his rigor was incredible, such that his healthy penitence turned into bloody cruelty. And it appeared to men that he was not a disciplining penitent but rather a fierce executioner that took vengeance on himself.] (1673, f. 13v; my emphasis)

Conclusions

In glossing the 1673 engraving’s allusion to Saint Martin of Tours, Medina’s frontmatter poems attempt to reconcile the portrait from the frontispiece and the body of the hagiography. On one hand, like a composite column, Martínez’s engraving combines disparate aspects of Martín’s reputation in a single figure, visually and sonically reinforcing the pretensions of Lima’s lettered elite as inheritors of the forms of classical Rome and successful propagators of Catholicism in the New World. On the other hand, Medina’s hagiography presents Martín as an ambivalent figure who is black on the outside but white on the inside. The distinct strategies adopted by the artist and the author ultimately coincide as ways of perceiving elements of whiteness that persist in Martín’s identity as a pardo. As a result, both strategies support racial discourses articulated by Creoles across the colonial Americas in the mid-to-late seventeenth century that assert ‘an identity and cultural continuity with their Old World ancestors, particularly manifest in colonial Euro-American creoles’ assertions of being white’ (Bauer and Mazzotti Citation2009, 33). Threatened by theories of environmental determinism increasingly wielded by Peninsulars to disparage all New World inhabitants, Creoles often emphasized color-based hierarchies that placed people with lighter skin and European features above the darker-skinned populations of Indigenous and African-descended peoples (Cañizares-Esguerra Citation1999; Citation2005; Earle Citation2012). Whereas Martínez uses the form of the composite to signal the persistence of whiteness in Martín’s physical image, Medina discursively developed Martín’s ambivalence as an exceptionally white-souled black man. Both strategies work to a similar end: making Martín exemplary of the spiritual virtue of Creoles in Lima.

This reading of the Creole subtexts to Martínez’s engraving and the accompanying frontmatter poems to the first edition of Medina’s hagiography finds further support in the fact that the engraving and all prefatory materials from the first edition were excised in the second edition of Medina’s hagiography published two years later in Madrid with the endorsement of the Spanish Royal Chronicler Félix de Lucio. Such editing to the frontmatter of a previously published book is common in early modern translations but not so much in reprintings. By removing the image, epigraphs, and most of the prefatory poems of the first edition, the second edition of Medina’s hagiography omits the explicit celebration of Lima’s spiritual virtue through Martín as well as all of the explicit modeling of Martín on Martin of Tours, a saint who might have been considered too ‘French’ for the official chronicler of Spain.Footnote44 As a result, the 1675 Madrid version does not present Medina’s Vida or its protagonist as examples of Creole intellectual or spiritual success as does the first edition. Instead, Lucio’s preface to the second edition generically praises Martín as a universal hero and Medina as a talented painter of narrative portraits (Medina Citation1675, f. [¶7r]).Footnote45

Among the many questions that remain about the way Martín was remembered, portrayed, and perceived in seventeenth-century Lima is how non-elite readers of the hagiography and viewers of Martín’s early portraits interpreted them. For example, an eye witness in the Vatican-sponsored beatification trial for Martín in Lima explains that in the processions celebrating the Vatican sponsorship of Martín’s case in 1678, Dominican priests and the secular elite paraded through the city streets alongside ‘la mayor parte de la gente que en esta America comunmente se llaman pardos’ [most of the people that in this America are commonly called pardos].Footnote46 How such pardo individuals perceived or potentially made their own images of Martín before and after this date has not yet been recovered, though Cussen mentions some examples of how mulato individuals of Lima in later centuries helped move along his beatification and canonization cases (2014, 12).

What does appear to be the case from available evidence is that the composite approach adopted by Martínez’s portrait was soon after rejected by commissioners of images and artists in Lima who preferred images of Martín that were more stereotypically black. As Miró Quesada (Citation1939), Gjurinovic Canevaro (Citation2012, 114–201), and Cussen (Citation2014, 169–78, 189–203) have shown, the proliferation of images of Martín in the ensuing decades and centuries centers a dark-skinned black man singularly identified with the physical appearance and social status of his mother. In rejecting Martínez’s composite approach, the visual archive of Martín produced afterwards suggests that many saw and continue to see something particularly desirable and spiritually efficacious in Martin’s physical embodiment of blackness.

Epilogue

A 2015 portrait based on a forensic facial reconstruction of Martín de Porres’s skull is currently on display in the Dominican Church of Lima. The portrait was made alongside those of Rose of Lima and Juan Macías by a Brazilian non-governmental organization called Equipe Brasileira de Antropologia Forense e Odontologia Legal by using CT-scans of the three skulls kept in the Dominican Church of Lima. The 3D images of the skulls produced by the scans were then used as the basis upon which Brazilian odontologist Paulo Miamoto and designer Cícero Moraes reconstructed each individual’s facial structure and features. In a televised interview with Peruvian reporters in 2015, Miamoto explains that colonial images of the saints were used ‘as a reference’ for their work rather than models they felt they had to follow. Miamoto specifies that the skin color of the new portraits was determined using the width of the nasal openings of each skull: because Rose’s nasal opening was smaller, Moraes says he made her appear ‘white in her race,’ while he used a darker color for Martín de Porres because his nasal opening was ‘wider,’ and therefore more ‘African.’

In a 2017 interview about the 2015 portraits, the museum director for the Convento de Santo Domingo, Friar Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho, describes his perception of the 2015 portrait of Martín as that of ‘a very normal mulatto of African heritage, very average, very ordinary’ compared to Rose’s ‘very lovely’ portrait. Citing Martín’s age and his almost entirely toothless jaw at the time of his death, Ramírez Camacho notes: ‘He wasn’t at all stylized, nor excessively beautiful, nor divinized in any way, nor sacralized. This captures your attention, because [it means] we are all called to sainthood. We don’t necessarily have to be spectacularly beautiful. We are all called to sainthood’ (Floyd Citation2017). Many centuries later, we see black figures again compared to white figures in religious portraiture as a means of indexing universality and humility. We also see that celebrating a dark-skinned individual as spiritually virtuous and even representative of a region’s spiritual wealth can still be deeply connected to the reification of pernicious racial hierarchies.

Acknowledgements

This article is indebted to the peer-reviewers of CLAR, Dana Leibsohn, Kathryn Santner, Helen Melling, Agnes Lugo-Ortiz, Noémie Ndiaye, Richard Neer, and Anna Schultz for their careful readings and suggestions. Invaluable help with research queries came from Niall Atkinson, Susanna Berger, Ximena Gómez, Andrew Hamilton, Bob Kendrick, Tristan Weddigen, and Luis Eduardo Wuffarden.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Larissa Brewer-García

Larissa Brewer-García is Assistant Professor of Latin American literature at the University of Chicago where she specializes in colonial Latin American studies, with a focus on the Caribbean, the Andes, and the African Diaspora. She is the author of Beyond Babel: Translations of Blackness in Colonial Peru and New Granada (2020).

Notes

1 While now spelled ‘Porres,’ documents composed during his life and those produced in the first 45 years after his death spell Martín’s last name as ‘Porras.’ I will be using the modern spelling of his last name hereafter except when directly citing earlier sources.

2 Isabel Flores de Oliva, or Saint Rose of Lima, was born within a few years of Martín in Lima into very different social conditions: she was a legitimate daughter of Spanish descendants of some means. After her death in 1617 she was beatified in 1668 and canonized only three years later in 1671 (Hampe Martínez Citation1998; Mujica Pinilla Citation2001; Myers Citation2003). Unlike Rose’s quick progress from beatification to canonization, Martín’s case encountered numerous delays after receiving initial support by the Vatican in 1678 (Cussen Citation2014, 180–84). His beatification was secured only in 1837, and he was finally canonized in 1962 (idem, 183, 197–202).

3 Rubén Vargas Ugarte (Citation1949) gave the date of 1663 for the text’s initial publication in Lima. He later noted that although an entry appears in the Acta sanctorum for a 1673 edition of text printed in Lima, it was probably never published (Citation1954, 61). Vargas Ugarte’s initial misdating of the first edition was then cited in the modern re-edition of the 1675 Madrid version of Medina’s text (Citation1964) and repeated by subsequent scholars (Cussen Citation1996; Brewer-García Citation2012). More recently, Cussen (Citation2014, 251 n.8) notes that while a 1673 version might have been published, she was unable to find it. See Brewer-García (Citation2016, 119) for an earlier brief analysis of Martínez’s image from the 1673 Lima edition kept at the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

4 While Medina’s Citation1673 hagiography is the oldest printed source on Martín, the oldest surviving narrative manuscript source is the first beatification inquest held for him in Lima between 1660 and 1664 (Archivo Arzobispal de Lima, Peru; hereafter AAL). This inquest is called the Diocesan trial; it was transcribed and published in 1960 (Proceso Citation196Citation0). In it, 73 individuals testified to their memories of Martín.

5 For the status of Creoles in seventeenth-century Peru, see for instance Lavallé Citation1993; Mazzotti Citation2003; and Graubart Citation2009.

6 Gjurinovic Canevaro (Citation2012) reproduces five images attributed to the seventeenth century, among them the double portrait at the Santuario de Santa Rosa de Lima described in the main body of this paragraph (119). Cussen’s more recent study does not examine the aforementioned double portrait and attributes two more anonymous and now lost paintings of Martín in ecstasy embracing Christ to the seventeenth century without specifying how she dated them (Citation2014, 170–71). Her source for these additional paintings (Miró Quesada Citation1939) does not date them to the seventeenth century.

7 Accessible at https://mavcor.yale.edu/material-objects/double-portrait-saint-john-mac-and-saint-martin-porres.

8 This position was first voiced by Miró Quesada, who observed that the double portrait uniquely shows Martín as a lighter-skinned man with graying hair compared to the more stereotypical images from the eighteenth century (Citation1939, 16–17). Ten years later Vargas Ugarte (Citation1949, lámina III) stated that the double portrait is likely one of the earliest, without explaining his conclusion. Most recently Gjurinovic Canevaro (Citation2012, 120) repeated Miró Quesada’s assessment verbatim. See Perkinson on how, in pre-modern and early modern portraiture, a representation of an individual ‘can be highly individualized without constituting an attempt to replicate the actual appearance of a particular individual’ (Citation2009, 8).

9 On the status of African descent donados and donadas in the Andes, see Cussen Citation2014, 27–28, and van Deusen Citation2018, 95–116.

10 On images of Saint Benedict of Palermo see Rowe Citation2019, 40, and Brewer-García Citation2019, 506–8. On an earlier use of hatching to mark a subject’s status as black in Iberian engravings, see Brewer-García Citation2016, 118–20.

11 A witness describing a now lost painting of Martín that hung over the doorway of the refectory of the Dominican convent’s infirmary in Lima in 1686 identifies a pouch hanging from Martín’s waist in the portrait as ‘un estuche de cirugía’ [a surgeon’s pouch] (Vargas Ugarte Citation1949, 15–16). A record from 1613 states that the Dominican Convent distributed 245 small loaves of bread each day to the poor in the city (Cussen Citation2014, 55). Bread as a sign of Christian charity is common in medieval Christian imagery (Williams Citation1993, 37–72). See also Cussen’s (Citation2014, 160–63) analysis of what appears to be a loose-leaf copy of José Martínez’s 1673 image of Martín, an engraving composed by Juan de Laureano and printed in Seville in 1676.

12 Medina’s narrative specifies that the only two possessions Martín owned were a wooden cross and a rosary (Citation1673, ff. 29v–30r), both displayed in Martínez’s image. Cussen (Citation2014, 160–63) analyzes a 1676 copy by Juan de Laureano of Martínez’s image. In her interpretation of this later image, which I cannot analyze here due to space constraints, Cussen suggests a similar connection between the rosaries hanging from Martín’s neck and hand and Lima’s Dominican convent dedicated to the Virgin of the Rosary. See Floyd (Citation2019) on indexes of regional specificity in prints made in Lima to portray local themes and materials in the late sixteenth to mid seventeenth century.

13 Archivo Franciscano de Lima, Peru (hereafter AFL), Registro 17, Discurso de la vida … , f. 566v. Estefanía, according to her hagiography, was born around 1560 to an enslaved black mother and an unknown Spanish father in Cuzco. Estefanía lived her adult life in Lima where she became a Third Order Franciscan and a slave owner, admired for her charity and humility. The hagiography specifies she was elegantly buried in the Third Order’s chapel in Lima’s Franciscan Church.

14 AFL, Registro 17, Discurso de la vida … , f. 566v.

15 On the particularly flexible use of the term ‘retrato’ [portrait] in early modern Spain, see Falomir Citation2004.

16 The first of these testimonies, by Doña Isabel Ortiz de Torres, specifies that the miracle occurred in 1648 (Proceso Citation196Citation0, 164).

17 On Titian’s portrait of Dinati and the black page, see Kaplan Citation1982, Fracchia Citation2019, 155–56, and Lowe Citation2012, 17–19.

18 The bibliography on the proto-national creole celebration of the Virgin of Guadalupe is too vast to include in its entirety here. See Taylor (Citation2003) and Peterson (Citation2014) for approaches that look beyond the Creole-authored hagiographical sources to trace the presence of Indigenous, Creole, and Spanish support for the cult in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century New Spain.

19 Compared to the case of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the scope of the circulation and appreciation of images of Martín was much smaller. Whereas images of Guadalupe had reportedly spread beyond the valley of Mexico City to the entire viceroyalty by the end of the seventeenth century (Brading Citation1991, 346), images of Martín proliferated much more locally in late seventeenth-century Peru in convents, parish churches, and some domestic spaces (Cussen Citation2014, 156).

20 On tiered notions of sanctity vis-à-vis non-white populations in narrative hagiographies from the colonial Americas, see Greer Citation2000, Cussen Citation2005, Bristol Citation2007, and Brewer-García Citation2019.

21 Comparisons can be made to the composition of the painting ‘Rose of Lima with the Child Jesus and Devotees’ by Lazzaro Baldi, Cafà’s contemporary in Rome (Weddigen Citation2018, 112). Baldi’s painting, in which black and Indigenous characters reverently admire Rose who is placed above them, was made for display in Santa Maria sopra Minerva for Rose’s beatification ceremony in 1668 or her canonization ceremony in 1671. The shared compositional strategy between Cafà and Baldi’s designs, it is fair to surmise, was favored and perhaps requested by González de Acuña, the Peruvian Creole who commissioned both artworks on behalf of his order.

22 For a point of comparison regarding the denial of the gaze as a denial of subjectivity, see Fracchia on Velázquez’s Kitchen Maid with Supper at Emmaus (Citation2013, 160–61).

23 See Rappaport (Citation2014, 189) on the trend in narrative portraiture to describe only white European men in relation to facial hair in early modern Iberian and Spanish American travel documents.

24 Serlio described the composite order in what is considered his treatise’s fourth book, first printed in 1537. Serlio’s third and fourth books were translated and published in Toledo in 1552. The same printer published two more editions of this translation in 1563 and 1573, indicating its popularity. On Serlio’s role in popularizing the notion of the composite in Renaissance conceptions of the classical orders throughout Europe, see Onians Citation1988, 263–86. On Serlio’s influence on artistic forms in New Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, see Sebastián Citation1989, 78–85, and Peterson Citation1993, 72, 75.

25 The formal and moral propriety of the composite is further accentuated in Covarrubias’s definition of the composite’s antonym descompuesto, which it defines as immodest, disheveled, and uncouth (Citation1611, 1: f. 229r, s.v. componer).

26 Like Martínez’s engraving, Balliu’s and Thiboust’s images were printed with hagiographies about Martín. Balliu’s image was printed as an illustration in a voluminous anthology of hagiographies of men and women affiliated with the Dominican order in the Andes that included Medina’s narrative about Martín (Meléndez Citation1681–Citation1682). Thiboust’s engraving was published with a smaller anthology of hagiographies of Dominicans from Peru (Manrique Citation1696).

27 The Divine Office is the name of the regularly scheduled prayers all religious of the early modern Catholic Church recited eight times a day (Harper Citation1991). The breviaries used as scripts for the Divine Office ensured that annual feast days of important saints were recognized as part of these regular prayers. The readings and lyrics in the breviaries are an under-recognized way that saint iconography spread sonically throughout the early modern Catholic world.

28 See Maurey (Citation2014, 1–130) for an overview of the development of the cult in Europe.

29 The verse comes from Severus Sulpicius’s Epistle 3 about Saint Martin, an appendix added to the Vita to describe Martin’s good death (Maurey Citation2014, 92, 97).

30 See Schenone Citation1992, 2:581–83. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden mentioned the following extant colonial paintings of Martin of Tours in Lima in a May 2020 email correspondence: an old copy of a Van Dyck painting at Lima’s Cathedral and a large canvas at the Instituto Riva-Agüero.

31 See Nirenberg (Citation2009) on the advent of biological racial language of heritable difference in late medieval Iberia as the adoption of animal husbandry discourse to describe religious differences. On New World colonial technologies of amalgamation and their relation to racial language in the seventeenth century, see Bigelow Citation2020, 229–93.

32 On stigmas associated with mulatos in literary texts from early modern Spain, see Fra Molinero Citation2000. Hill (Citation2004, 242–43) traces Covarrubias’s reference to the mule to Pliny’s writings on the generation of species. Li Causi (Citation2008) presents a nuanced reading of Aristotle’s writings on generation that undergird Pliny’s position that all offspring of two different species constitute a third degenerate species. While Aristotle associates form with the father and matter with the mother and suggests that any variation of the form of the father is negative, there is some ambiguity about whether he considered hybrid progeny degenerate (ibid.). For an example of the use of Pliny to describe mulatos in early seventeenth-century Spanish America, see Pallas [Citation1619] Citation2006, 192–95. For the borrowing of language from horse and dog breeding to describe mixed race peoples across the Hispanophone Atlantic world in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries, see Hill Citation2015.

33 Whether or not black or African-descended individuals could claim limpieza de sangre (blood purity) was a fraught issue throughout the early modern Iberian world (Martínez Citation2004; Ireton Citation2017).

34 On the relationship between the terms zambaigo and mulato, see Ares Queija Citation2000, Forbes Citation1993, 234–36, and Graubart Citation2012, 52–53. See also Schwartz (Citation1997) and Twinam (Citation2009) on the continued porousness between the terms pardo and mulato in the later eighteenth-century Caribbean. On the use of mulato as a term to describe the color of servants brought to Spain from the Americas in late sixteenth-century Spain as a way of legitimating their servitude, see van Deusen (Citation2012, 229). Elsewhere, I have noted that the narrator of Medina’s hagiography only calls Martín a pardo directly, reserving the epithet mulato in the narrative for cited speech in which Martín’s contemporaries seek to humiliate him or when Martín humiliates himself (Brewer-García Citation2012, 133).

35 Also, like other free black men and women in Spanish America, mulatos were subject to a tribute charged of free people of African descent in Spanish America (Schwartz and Salomon Citation1999; Vinson and Milton Citation2002). There was, thus, a financial incentive for mulato individuals to try to pass as whites.

36 See Graubart (Citation2012) for examples of both the combination and disaggregation of stigmas in conflicts among confraternities of people of African descent in Lima. See O’Toole (Citation2015) for efforts by individuals of African descent in colonial Trujillo to disaggregate some of these stigmas.

37 In contrast to these two prefatory poems and the epigraph to the hagiography that repeats the line from the frontispiece portrait’s cartouche, only one reference to Saint Martin of Tours appears in the body of Medina’s narrative: ‘Estimulado de su caridad, y del exemplo del Sãto de su nombre, no una vez, sino dos, no partida, sino entera, dio a pobres su pobre capa’ [Inspired by his charity, and the example of the saint with his name, not once but twice he gave not part but all of his poor cape to the poor] (1673, f. 34v). As in Medina’s prefatory ‘Romance,’ the reference positions Martín as a poorer and therefore a potentially more virtuous version of Saint Martin of Tours.

38 Myers (Citation2003), Millones (Citation1993), and Mujica Pinilla (Citation2001), among others, explain how Rose's image has been used and redeployed for distinct purposes since the early seventeenth century. Brading (Citation1991, 337-42) and Morgan (Citation2002, 67-98), who analyze hagiographies of Rose of Lima from earlier in the seventeenth century, argue that Creoles do not present her as distinctively Peruvian but rather as a New World copy of the Virgin of the Rosary or Saint Catherine of Siena, respectively. Hampe Martínez (Citation1998) concurs with Vargas Lugo's reading of the Creole celebration of Rose of Lima.

39 Mujica Pinilla notes that one Creole Franciscan in the seventeenth century claimed that Rose’s maternal grandparents were recently Christianized ‘indios’ (Citation2016, 253). Yet this reading of her lineage was not widespread during the period and instead she was presented as early as her first beatification inquest as a ‘criolla.’ See also Iwasaki Cauti (Citation1994) for the argument that the Dominican order and the Church endorsed the campaign to beatify Rose and Martín to teach humility to arrogant white Creoles.

40 See Mazzotti (Citation2003) and Floyd (Citation2019) on seventeenth-century efforts by limeños to use the printing press to make similar claims for Lima’s intellectual and spiritual participation in the Iberian empire. On Indigenous and Creole self-fashioning through visual portraiture of the later colonial period, see Estabridis Citation2003, Engel Citation2010, and Stanfield-Mazzi Citation2011.

41 Medina, we learn from the Citation1673 title page, was ‘natural de la mesma Ciudad de los Reyes, Regente de los Estudios del Convento del Rosario de Lima, y Prior electo del Convento de Santo Tomas de Guanaco, del Orden de Predicadores.’ Many of the approvals to the Citation1673 text praise Medina’s eloquence as an orator and writer, holding him up as a comparable phenomenon to Martín, another local hero worthy of recognition and praise.

42 On precedents for this type of language to describe black sanctity, see Brewer-García Citation2019.

43 See Cohen Suarez (Citation2016) on the symbolic and yet still racial use of skin pigmentation to portray saved and damned souls in eighteenth-century mural paintings of the last judgement in the Andes.

44 See Maurey (Citation2014, 232–38) on the efforts in the late medieval period to exalt the Frenchness of Saint Martin of Tours.

45 A reader of the second edition of Medina’s hagiography supplemented their copy of the second edition by stitching a 1676 engraved copy of Martínez’s portrait into the binding of the book (Cussen Citation2014, 160–63), showing the reversal of some of Lucio’s editorial interventions. This supplementation made the copy printed in the Spanish metropole more like the original printed in the colony. That the 1673 hagiography and its image had gained a reputation for producing miracles by the time of the second beatification inquest for Martín in 1678 (AAL, SE, PBCMP, Book 2, f. 182; Book 3, f. 220; Book 6: ff. 338v, 388v, 562v) could have provided special incentive to do so. On the practice of applying prints to the body to enact curing miracles in Spanish Catholicism of the period, see Portús and Vega Citation1998, 213–61.

46 AAL, SE, PBCMP, Book 1, 9r–10r.

Bibliography

- Ares Queija, Berta. 1997. El papel de mediadores y la construcción de un discurso sobre la identidad de los mestizos peruanos (siglo XVI). In Entre dos mundos: fronteras culturales y agentes mediadores, edited by Berta Ares Queija and Serge Gruzinski, 38–59. Seville: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- Ares Queija, Berta.. 2000. Mestizos, mulatos y zambaigos (Virreinato del Perú, siglo XVI). In Negros, mulatos, zambaigos: derroteros africanos en los mundos ibéricos, edited by Berta Ares Queija and Alessandro Stella, 75–88. Seville: Publicaciones de la Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos.

- Bauer, Ralph, and José Antonio Mazzotti. 2009. Introduction: Creole subjects in the colonial Americas. In Creole subjects in the colonial Americas: empires, texts, identities, edited by Ralph Bauer and José Antonio Mazzotti, 1–57. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bigelow, Allison Margaret. 2020. Mining language: racial thinking indigenous knowledge, and colonial metallurgy in the early modern Iberian world. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bowser, Frederick P. 1974. The African slave in colonial Peru, 1524–1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Brading, David A. 1991. The first America: the Spanish monarchy, creole patriots, and the liberal state, 1492–1867. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Brading, David A.. 2001. Mexican phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: image and tradition across five centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Breviarium Romanum. 1592. Antwerp: Widow of Jan Moretus.

- Brewer-García, Larissa. 2012. Negro, pero blanco de alma: la ambivalencia de la negrura en la Vida prodigiosa de Fray Martín de Porras (1663). Cuadernos del CILHA 13 (2): 112–45.

- Brewer-García, Larissa.. 2016. Imagined transformations: color, beauty, and Black Christian conversion in seventeenth-century Cartagena de Indias. In Envisioning others: representations of “race” in the Iberian and Ibero-American world, edited by Pamela Patton, 111–41. Leiden: Brill.

- Brewer-García, Larissa.. 2019. Hierarchy and holiness in the earliest colonial Black hagiographies: Alonso de Sandoval and his sources. William and Mary Quarterly 76 (3): 477–508.

- Brienen, Rebecca P. 2013. Albert Eckhout’s African woman and child (1641): ethnographic portraiture, slavery, and the New World subject. In Slave portraiture in the Atlantic World, edited by Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal, 229–55. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bristol, Joan Cameron. 2007. ‘Although I am Black, I am beautiful’: Juana Esperanza de San Alberto, Black Carmelite. In Gender, race, and religion in the colonization of the Americas, edited by Nora Jaffary, 67–80. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Busto Duthurburu, José Antonio del. 1992. San Martín de Porras (Martín de Porras Velásquez). Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge. 1999. New World stars: patriotic astrology and the invention of Indian and Creole bodies in colonial Spanish America, 1600–1650. American Historical Review 104 (1): 33–68.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge.. 2005. Racial, religious, and civil Creole identity in colonial Spanish America. American Literary History 17 (3): 420–37.

- Cohen Suarez, Ananda. 2016. Heaven, hell, and everything in between: murals of the colonial Andes. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Covarrubias y Orozco, Sebastián. 1611. Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española. Madrid: Luis Sánchez.

- Cussen, Celia L. 1996. Fray Martín de Porres and the religious imagination of Creole Lima. PhD. dissertation. University of Pennsylvania.

- Cussen, Celia L.. 2005. The search for idols and saints in colonial Peru: linking extirpation and beatification. Hispanic American Historical Review 85: 417–48.

- Cussen, Celia L.. 2014. Black saint of the Americas: the life and afterlife of Martín de Porres. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Earle, Rebecca. 2012. The body of the conquistador: food race, and the colonial experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Engel, Emily. 2010. Official portraiture and authority in late-colonial Lima and Buenos Aires. Dieciocho 33 (1): 169–206.

- Estabridis, Ricardo. 2003. El retrato del siglo XVIII en Lima como símbolo del poder. In El barroco peruano, edited by Ramón Mujica Pinilla, 2:134–71. Lima: Banco de Crédito.

- Falomir, Miguel. 2004. Los orígenes del retrato en España. De la falta de especialistas al gran taller. In El retrato español: del Greco a Picasso, edited by Javier Portús Pérez, 72–95. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado.

- Floyd, Emily C. 2017. Reconstructing the faces of the saints: an interview with Friar Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho, O.P. Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion. https://mavcor.yale.edu/mavcor-journal/interviews/reconstructing-faces-saints-interview-friar-luis-enrique-ram-rez-camacho-o.

- Floyd, Emily C.. 2019. Privileging the local: prints and the New World in early modern Lima. In A companion to early modern Lima, edited by Emily A. Engel, 360–84. Leiden: Brill.

- Forbes, Jack. 1993. Africans and Native Americans: the language of race and the evolution of Red-Black peoples. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Fra Molinero, Baltasar. 2000. Ser mulato en España y América: discursos legales y otros discursos literarios. In Negros, mulatos, zambaigos: derroteros africanos en los mundos ibericos, edited by Berta Ares Queija and Alessandro Stella, 123–47. Seville: Publicaciones de la Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos.

- Fracchia, Carmen. 2013. Metamorphoses of the self in early-modern Spain: slave portraiture and the case of Juan de Pareja. In Slave portraiture in the Atlantic world, edited by Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal, 147–69. New York: Cambridge University Press.