ABSTRACT

Among the many unprecedented challenges that Brazil presented to the Jesuits, perhaps the most surprising was its resistance to making viable martyrs. The two places most likely to provide them a violent death were the sertão (backlands) and the sea. Jesuits in the Portuguese colony wanted adversaries to slay them in odium fidei (in hatred of the faith), a traditional requirement for martyrdom. Yet the Jesuits’ rhetorical construction of Indigenous peoples in the sertão, combined with its complex social dynamics, proved incompatible with this requirement. During the first decades of the province of Brazil, the Soldiers of Christ found that while their evangelical work remained on land, the sea’s narrative tropes suited the requirements for martyrdom best. To build their case for Jesuit martyrs in Brazil, José de Anchieta and his Jesuit companions subverted an age-old poetic landscape and constructed a fluid literary cartography.

‘O sertão vai virá mar e o mar virá sertão.’

Attributed to Antônio Conselhiero (Cunha Citation1902)

The unsigned letter’s hopeful interpretation silently gestured to the Jesuits’ decades of misfortune in Brazil. The murder of their companions had come at a time of despair for the mission. Despite their best efforts to elevate their fallen brethren, none of the Jesuits killed on Brazilian soil by Indigenous peoples had yet been suitable candidates for martyrdom. To be a martyr, which was historically a first step towards canonization, one had to be killed ‘in hatred of the faith.’ The Jesuits’ own descriptions of native Brazilians as religious naïfs who could not possibly kill anyone in hatred of any faith, undercut their efforts with the Vatican. Death at sea, at the hand of those recognized as heretics by the Church hierarchy, was a much more viable route to martyrdom and sainthood—and through them, legitimacy for the Jesuit mission in Brazil. This article teases out the narrative strategies the Jesuits created to make death at sea worthy of martyrdom, when death in the sertão (backlands) failed to bring them greater glory.

The anonymous letter writer’s interpretation of those forty men’s deaths has a deep history in apostolic Christianity and harks back to the bedrock, as it were, of the early Church. Martyrdom had been fundamental to the Church’s spiritual and physical foundation, and those who died for Christ in ancient times would be considered his most perfect imitators (Moss Citation2010). The Apostle Peter, said to have been martyred during Nero’s reign, was considered the first pope in Rome. According to tradition, his remains were buried in the Roman cemetery over which a basilica was erected during Constantine’s reign, and over which present-day Saint Peter’s Basilica now stands. The initially episodic Roman persecution of Christians spread in the third and fourth centuries, and Christian apologists highly regarded those who were killed, using them to underscore a sacrificial interpretation of Christ’s death (Moss Citation2013).

Persecuted Christians’ remains, like those of Peter, in turn entered the physical construction of churches. The Apostle Paul had referred to Christ as the ‘Chief Cornerstone of the Church’ (Ephesians 2:20). The patrons of early churches took inspiration from these words and had martyrs’ relics placed in their foundation stones. One Catholic rite involved a bishop, or a priest, blessing the foundation stone and the relics therein as a creaturam istam lapidis [creature of stone]. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) picked up this thread when it affirmed that martyrs’ ‘holy bodies’ were ‘temples of the Holy Spirit’ (O’Malley Citation2013, 233–34). Following ancient tropes and Catholic tradition, early modern Catholics, and the Jesuits in particular, believed that the Church’s successful expansion overseas depended on crowing new martyrs, whom they embraced as the groundwork for establishing ‘new churches’ (Cymbalista Citation2011; Gregory Citation1999).

This tradition allowed the Jesuits to both overcome their losses and to affirm that their forty brothers’ deaths at sea laid the spiritual foundation for the Church in Brazil. Huguenot pirates led by Jacques de Sores (also written Jacques de Sorie, fl. 1555–1570) had brutally killed the passengers aboard the Santiago on their way to replenish the struggling, understaffed Brazilian missions. According to some accounts, Sores and his men slit the throats of nearly all on board. The slain were led by the Jesuit Ignatius (Inácio) de Azevedo (1526–1570), the descendant of two of Portugal’s most illustrious families, who had already served as visitor to Brazil and was on his way to take up the post of provincial.Footnote2 A survivor, Pero Dias, wrote an account of the original attack, and then continued his journey to Brazil with a smaller retinue. Pirates, this time led by Jean de Capdeville, assailed them on an outbound voyage to Brazil near the Azores, producing further candidates for martyrdom (Leite Citation1938, 254). Paradoxical as it may seem, the Jesuits reasoned that this setback would strengthen the Church’s hold on the Portuguese colony since Catholic martyrs interceded to the benefit of the living (Cymbalista Citation2011, 162).

This maritime tragedy occurred in the middle of what has been called a ‘Renaissance’ of martyrdom (Cañeque Citation2020; Gregory Citation2000). At the beginning of the sixteenth century, it had become rare for Christians in Europe and especially on the Iberian Peninsula, where the Catholic Church had consolidated, to suffer physical martyrdom (Russell Citation2020, 70–74; Cañeque Citation2020, 17–19). By the middle of the sixteenth century, this had changed, and violent confessional conflict marked the return of martyrdom to the realm of the possible for much of Catholic Europe (Molinari and O’Donnell Citation2003). Books popularized images and tales of pious Catholics being slaughtered by Reformed Christians in England, the Low Countries, and France, and Catholics consumed with increased fervor tales of ancient martyrs such as Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea.Footnote3 In this same period, stories of Catholic missionaries slain overseas poured into Europe.

Martyrdom held special appeal for the Society of Jesus, which made spiritual and physical suffering central to its ethos.Footnote4 Founder Ignatius (Iñigo) of Loyola underwent religious conversion when he was convalescing from battle wounds, meditating on Christ’s passion and reading Ludolph of Saxony’s The life of Christ and Voragine’s Legenda Aurea, which contains the tales of 91 martyred saints (Cymbalista Citation2011, 165).Footnote5 It was said that Loyola himself wished to acquire the palm of martyrdom in Jerusalem, and the Society of Jesus’s headquarters were established in Rome, where the early persecutions of Christians influenced their imaginary. Members of the Society consumed martyrdom tales sometimes daily, as when they customarily read the Roman martyrology over supper (Russell Citation2020, 95; O’Malley Citation1993).

The Jesuits could expect to soon have martyrdom candidates of their own since the Formula of the Institute included a special vow to journey to any part of the world on the pope’s orders, regardless of the threat to their lives (O’Malley Citation2012, 147–64). Over time, professed Jesuits expressed their desires to achieve martyrdom and requested to join the notoriously risky missions of Japan, India—where Antonio Criminale suffered the first violent Jesuit death in 1549—and China, on the outskirts of which the highly influential Jesuit Francisco Xavier died in 1552 (Russell Citation2020, 77, 92–98).Footnote6 The first Jesuits arrived in Brazil around the same time, in 1549, with Manuel da Nóbrega at its head, and Brazil became a province in 1553. The deaths of missionaries there, as in the East, would provide the Soldiers of Christ with opportunities to compare their young society, founded only in 1540, with the early Church, and thus imbue it with the authority of antiquity.

The Jesuits’ increasing number of missionaries who died violent deaths overseas was not a guaranteed boon to their order. Instead of celebrating the abundance of candidates, the Church temporarily stopped canonizing new saints and began rethinking the canonization process.Footnote7 The impending changes to the rules of canonization made a persuasive case for martyrdom ever more important. Unsure of the Church’s future criteria, chroniclers sought legitimacy in the Church’s past, taking tales of ancient Christian martyrs as the benchmark of true martyrdom. Fortunately for them, the Jesuits could easily cast the Huguenot corsairs who threw the forty into the Atlantic as enemies of the faith on a par with pagan Roman emperors, making for a compelling martyrdom narrative.

The stage was set for prominent Catholics and Jesuits to hail the missionaries and laymen’s deaths as God’s blessing to Brazil. Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), who was a relative of one of the dead, claimed to have had a miraculous vision of them wearing crowns in heaven on the day they died, and Superior General Francis Borgia (1510–1572) was said to have prayed to them daily. The anonymous Jesuit from the College of Saint Anthony who wrote the letter referenced at the beginning of this article predicted that the deceased would eventually be canonized. He wrote that just as the parts of the world where Christianity rooted long ago have ancient saints as ‘their advocates and patrons in the Heavens,’ God wished to give with these deaths ‘new saints and new patrons in the heavens’ to Brazil (cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:306).Footnote8

The Jesuit José de Anchieta (1534–1597), likely known to the unnamed Jesuit through correspondence, praised the recently departed. Born in the Canary Islands and educated in Coimbra, Anchieta was at the forefront of evangelization efforts in Brazil, creating a grammar of Tupi, the language most spoken by Indigenous groups living along the coast. He also composed lyric poetry and autos (short religious dramas) in Tupi, Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin. He rose to the ranks of provincial and was widely expected to be made a saint even during his lifetime, with his first hagiography-styled biography appearing just one year after his death (Rodrigues Citation1988).Footnote9

Anchieta composed poems to commemorate the forty Jesuit missionaries and laymen killed on their way to Brazil, as well as the survivors of the original attack who pressed on the following year and died in strikingly similar fashion. While many martyrdom narratives were written after their deaths, Anchieta’s lyric poems stand out for the strikingly creative ways he found to situate the forty within an understanding of martyrdom that the Catholic hierarchy could accept. Moreover, as will be seen, his writings on martyrdom interconnected the sea and the sertão in ways that anticipated a recurrent trope in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Brazilian literature and culture.Footnote10

In his poems, Anchieta boldly invoked the tradition that held the ancient martyrs to be the spiritual and physical foundation of the primitive Church, depicting the Jesuit missionaries and laymen who languished at sea as the bedrock of the ‘new Church’ in Brazil. Seizing on the fact that one of the deceased had the same name as the Apostle Peter, whom Christ himself named (in Latin translation) petrus, meaning ‘rock’ or ‘stone,’ Anchieta presented their martyrdoms as particularly sturdy and ‘hard.’ In one poem in Spanish, he construed Pero [Peter] Dias as a ‘Stone of Light’ through a play-on-words with his name (Pero Días = Piedra / Día [Stone / Day]).

Si fue ‘Pedro’ por ser piedra

‘día’ fue por resplandor

con tal gracia del Señor

que con él no tuvo medra

el oscuro tentador. (Citation1998, 68)

Si quieres firmeza y luz

como el Padre Pero Dias

sigue al Salvador Mesías

Pero Dias piedra fue

miembro de la piedra viva

en que el edificio estriba

de toda la santa fe

que los sentidos cautiva. (Ibid.)

Anchieta’s stone metaphors matched his and his Jesuit counterparts’ confidence that the forty clearly fulfilled martyrdom’s central requirement: to be killed out of hatred of the Catholic faith (in odium fidei) and in its defense. The Jesuit Provincial of Portugal, Jorge Serrão (c. 1528–1590), affirmed that they foundered at the hands of ‘heretic corsairs’ and were killed ‘in odium fidei et Ecclesiae Romanae’ (in hatred of the faith and of the Catholic Church) (cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:305n120).Footnote11 This was not a difficult case to make since Sores was notorious for his iconoclasm. Allegedly, he once ordered his men to chop off the arms of a statue of the Virgin Mary at Santa Marta, on the coast of Tierra Firme, remarking that as the mother of God, she should be able to fend for herself (Lane Citation2016, 22). Since Reformed Christians such as the Huguenots were sworn enemies of the Roman Catholic Church, the hateful motives of the corsairs were undisputed among Catholics. The Jesuits’ self-assuredness was vindicated by the tacit approval of Pope Pius V (r. 1566–1572), who himself paid homage to the martyrdom candidates just one year after they perished.

Anchieta and his counterparts’ move to establish the sea as the solid ground of martyrdom narratives subverted their contemporaries’ poetic construction of the sea as wild, mutable, and treacherous, from Luís Vaz de Camões’s (c. 1524–1580) Os Lusíadas (Citation1572) to the sixteenth-century shipwreck tales later anthologized in Bernardo Gomes de Brito’s História trágico-marítima (Citation1735–Citation1736).Footnote12 Scholars have paid considerable attention to poets and chroniclers who developed classical tropes in light of Iberia’s (and especially Portugal’s) overseas ventures, more often than not centering on how they imagined themselves drawing on traditions from antiquity. The authors of these works are said to have retaken the image of Poseidon’s wrathful sea storms in Homer’s Odyssey and the disorienting, obstructive seas of Virgil’s Aeneid. The strength of seaborne martyrdom in Anchieta’s lyric poems, and his companions’ correspondence, commandeered this age-old poetic landscape by highlighting the redemptive potential for martyrdom of an ocean infested with clear enemies of the faith. In other words, for Anchieta, within the sea’s undeniable treachery lay the stable ground of redemption.

For the early Jesuits in Brazil, the ever-expanding space that washed away any traces of the past was not the ocean, even if it had often been construed this way in epic poetry and shipwreck narratives. Rather, the shifting, empty horizon of Christological time was the sertão, the unconquered, inland territories where Indigenous peoples remained free.Footnote13 The elements deemed crucial to martyrdom narratives were missing there, and this lack produced an alternate stone rhetoric. In the first Provincial Manuel da Nóbrega’s (1517–1570) Diálogo sobre a conversão do gentio (composed 1556–1557), the interlocutor Gonçalo Álvarez, a figure based on a real-life Jesuit missionary of the same name, vents his frustrations with evangelization: ‘to preach to these people is to preach to stones in the desert’ (Nóbrega Citation2010, 144). Solidity here manifests itself as (particularly) dry land and becomes not the rock of Saint Peter, but the fruitless effort to get blood from a stone.Footnote14

The Jesuits sent to Brazil discovered new possibilities and limitations for martyrdom in both the physical contours and the social worlds of overseas spaces, independent of the poetic landscapes of high culture, and the privilege that scholars continue to give them today. Antiquity's poetic construction of a treacherous ocean proved incomplete for them. In the waters near the Canary Islands and the Azores, Anchieta and his Jesuit companions found the key narrative elements of martyrdom: workable metaphor, a compelling plot, legible characters and, most importantly, the trappings of religious conflict. The sea organized people into clear, broad categories that lent themselves to martyrdom narratives. Catholics readily identified corsairs who hailed from the lands of notorious Reformers, whatever their true motivations and confessional involvement, as unambiguous religious adversaries.

The sea and the sertão, the spaces in which the Jesuits could most likely perish, differed starkly in the likelihood that adversaries would slay the Jesuits in a manner the Vatican might deem in hatred of the faith. The Brazilian interior did not provide the basic plot elements. The perception that Indigenous inhabitants were indifferent to Christianity, combined with internecine conflicts, led to more than one dead end, even as hagiographers struggled to fill the narrative gaps the native Brazilians could not. There were too many entangled factions in the sertão—slave hunters, Jesuit missionaries, warring Indigenous groups—to clearly say who killed whom there and why. Martyrdom languished when complex, overlapping conflicts resisted narration in terms of clear oppositional violence.

Of the first two prominent cases of Jesuit martyrdom in sixteenth-century Brazil, the first arose from the sertão, where two missionaries perished, and the second from the sea, where the lives of the forty were claimed. Whereas the first case gained little traction and faded into oblivion, the second garnered widespread enthusiasm, and the candidates were eventually beatified in the nineteenth century. Anchieta strengthened the case of the forty on their path to martyrdom by taking what was useful to him from contemporary rhetoric surrounding maritime and confessional conflict. His poetic techniques reveal a polyphonic Catholic construction of the sea as a fruitful domain for early modern martyrdom and evangelization.

In the end, the Jesuits would recognize both the sea and the sertão as complementary arenas for the success of their enterprise. They constructed a fluid literary cartography in their early reports on these deaths, which reverberated in seventeenth-century accounts. Furthermore, how they did so paved the way for later tropes in Brazilian cultural production that inverted the sea and sertão, most famously the leader of Canudos Antônio Conselheiro’s apocalyptic prophecy that the backlands would turn into the sea, and the sea into backlands (Cunha Citation1902). The Soldiers of Christ found that while their evangelical work remained on land, the sea’s narrative tropes suited their requirements for martyrdom best. Even as they continued preaching inland, they heeded the ocean’s pull, constructing compelling martyrdom narratives there and forsaking the sertão as a kind of narratively terrifying ocean.

The inglorious sertão: the path to being forgotten

In 1556, Provincial Manuel da Nóbrega, to address the missionaries’ despondence at their failure to save Brazilian souls, composed a dialogue in which two Jesuit interlocutors extensively debate perceived obstacles to conversion, Diálogo sobre a conversão do gentio. As a synthesis of the missionaries’ early frustrations, it captures the rhetorical construction of native Brazilians in early Jesuit letters.Footnote15 In the first part, the interlocutor Matheus Nugueira complains to his counterpart Gonçalo Alvarez that the Temiminó catechumen associated with the morubixaba (superior) Maracajá-Guaçu, known to Europeans as ‘o Gato,’ immediately embraced Christianity, only to just as quickly abandon it: ‘with one hook that I give them, I will convert all of them, and with others, I will then unconvert them, because they are fickle, and real faith does not enter their hearts’ (Nóbrega Citation2010, 144).Footnote16 Missionaries described native catechumen, primarily Tupi-speaking groups from the Brazilian coastline, as shapeshifters who were perhaps unable to become steadfast Christians. This discourse of ‘inconstancy’ was made famous by anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, who writes, ‘In Brazil, the word of God was eagerly welcomed with one ear and negligently ignored with the other. Here, the enemy was not a different dogma, but an indifference to dogma, a refusal to choose. Inconstancy, disinterest, forgetfulness’ (Citation2011, 4). Since the Jesuits widely reported that Brazil’s Indigenous peoples were not opposed to Christianity, and were in fact incapable of opposing it, they could hardly claim that native assailants killed their missionaries out of a sustained hatred of the faith.

Catholics and Jesuits in Europe and Asia had found that an effective strategy for promoting martyrs was to tell new stories about them in the mold of ancient ones. In Brazil, Nóbrega plainly admitted that the sertão lacked the necessary antagonisms: ‘These heathens are not like the heathens surrounding the early Church, who would either quickly mistrust or kill anyone who preached against their idols, or believe in the Gospel, thereby preparing themselves to die for Christ’ (Citation1955, 464; as translated in Castro Citation2011, 8). It was widely said that native Brazilians lacked three crucial elements—fé, lei, rei (religions, laws, and kings) (Gândavo Citation1980; Sousa Citation1971, 302). The Jesuits could not easily compare Brazilian ‘gentiles’ with Roman pagans when they themselves claimed that the former had no religion and no religious devotions. Scholars have tended to focus on the Jesuits’ frustrations that it was difficult if not impossible to convert these populations instead of the consequences that the perception of native indifference to Christianity had on early martyrdom campaigns (Castro Citation2011; Castelnau L’Estoile Citation2000).

Allegations of coordinated persecution of Christians were likewise difficult to make in Brazil, even though they would help produce martyrs as in Nagasaki, Japan, albeit with controversy (Zampol d’Ortia Citation2020, 174). At the outset of Nóbrega’s Diálogo, the fictionalized missionary Nugueira observed that deficiencies in political organization compounded the problem of so-called inconstancy (Citation2010, 144). ‘If they had a king, they could be converted,’ he says, and then reflects that the ancient Romans had more policia (roughly, civility) (idem, 144, 158). According to the settler Gabriel Soares de Sousa, ‘they do not obey anyone, neither does the son obey the father, nor the father obey the son’ (Citation1971, 302). This perceived unruliness dismayed the Jesuits, who also imagined that evangelization efforts would be incredibly onerous. Rather than converting political leaders, as the Jesuits strategized in East Asia, they contemplated having to individually redeem every soul in Brazil.

The Jesuits reported violence that was structurally different from the reported persecution of Christians in ancient Rome. In the latter, Roman tribunals had expressly condemned Christians to death for their faith and in response to their self-identification as such. The Jesuits in contrast described a set of historical characters marked by indifference, and rhetorically constructed a setting defined by cyclical violence, ‘cannibalism,’ and vengeance. The Jesuit Visitor to Brazil Cristovão de Gouveia, among many others, reported that the native peoples, ‘kill those they take in war with great festivals, and for sheer revenge they eat them’ (Loyola Citation1904, 1:740). In the Brazilian interior, the murders of missionaries were often attributed to entanglement in non-religious conflicts or else seen as isolated acts similar to what are today called ‘crimes of passion’ rather than premeditated persecution (Cañeque Citation2020, 324). The motives behind such violence were difficult to ascertain.

The problem was that the Jesuits needed another set of characters and another setting entirely for their martyrdom cases to work. From the raw events of their brothers’ deaths, they would construct narratives (i.e. bids for official martyrdom, beatification, and/or sainthood) whose central requirement—hatred of the faith—were at cross purposes with their earliest reports on the land and its people. On the martyrial front as on the missionary front, the sertão was proving to be, for them, a spiritual wasteland.Footnote17

When two missionaries perished in the sertão between Brazil and Paraguay, Anchieta embraced them as candidates for martyrdom, despite the many challenges. Almost immediately, he invoked stone metaphors. In a 1555 letter addressed to the Society’s Superior General Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), Anchieta, a distant relation of his, boldly declared the two men, Pero Correia and João de Sousa, the foundations of the ‘new Church’ that the Jesuits wished to establish in Brazil. He wrote that he and his companions believed that God had laid Correia and Sousa as ‘two stones’ soaked in ‘glorious blood’ (Anchieta Citation1933, 82; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294). His express desire to follow in Correia’s and Sousa’s footsteps signaled their viability for popular devotion, which he gave the impression was already spreading. Anchieta continued, ‘May God, if my sins are not too great, grant that I be also laid, as a third [stone]’ (Citation1933, 82; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294). He wrote that the other Jesuits found their fates exemplary: ‘all of us ardently desired and begged God, with continuous prayers, to do also in like manner’ (Citation1933, 76; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294).Footnote18 Correia and Sousa’s story, it could be hoped, would inspire more Jesuits to travel to Brazil from Europe in search of a similarly glorious fate, giving the missions a much needed boost.Footnote19 Nevertheless, the sertão would present obstacles to their commemoration and eventually wash away their identities.

Anchieta’s optimistic account of their deaths, following that of a Portuguese witness, was convoluted, exposing a web of conflict that made it difficult if not impossible to identify an adequate motive for the slaying (Leite Citation1938, 2:240). Anchieta first described how Correia and Sousa were charged with ensuring the safe journey of Spanish nobles to Paraguay and preached to the inhabitants of the interior along the way. In Cananeia, Correia liberated prisoners of war, two Carijós and one Castilian, held by the Ibirajáras. Correia and Sousa then pushed further into the sertão pacifying and evangelizing the Carijós. They came across two interpreters, one Portuguese and one Castilian. The Castilian had reportedly lived among the Carijó for a long time and resented the Jesuits for previously denying him an Indigenous concubine. In Anchieta’s account, the Castilian incited the Carijós against the Jesuits, convincing them that Correia planned to hand them over to their enemies, who would surely kill them (Citation1933, 81). Believing this, the Carijó attacked Correia and Sousa, murdering them both by shooting them with arrows. Anchieta’s praise of these candidates for martyrdom was immediately plagued by a problem: his account did not provide the traditional requirement of in odium fidei.

According to Serafim Leite, author of the foundational history of the Jesuits in Brazil, Anchieta interpreted Correia’s and Sousa’s deaths as martyrdom, even though official recognition would be hard to come by, based on Correia’s and Sousa’s ‘fulfillment of divine law in serious matters’ (Leite Citation1938, 2:241). Saint Augustine had influentially claimed that it was not the punishment but the cause (non poena sed causa) that makes a martyr, and many early martyrs were killed for refusing to apostatize. Yet theologians had also argued that those who offered their lives in defense of Christian virtue, or for Church order and discipline, were also martyrs (Gilby and Cunningham Citation2003, 230). In this broader sense of martyrdom, Anchieta praised the deaths of these Jesuits in the sertão: ‘They died for obedience, for preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and for the peace and love of their neighbors.’ The noble causes of deaths accumulate in his letter, and Anchieta compares them to precious stones adorning a martyr’s crown: ‘And so they may not lack in their crown this precious stone, they died for truth, for justice, and for the exaltation of our faith, which they were preaching’ (Anchieta Citation1933, 82).

Anchieta’s Jesuit companions, in contrast, focused on the one ‘precious stone’ that was missing: in odium fidei. Jesuit Visitor Cristóvão de Gouveia raised his objection in the unlikely place of his review (‘censura’) of the important early Jesuit and biographer Pedro de Ribadeneira’s (1526–1611) Vida de San Ignacio de Loyola which provided an account of the foundation and early years of the Society of Jesus. Ribadeneira described how Correia and Sousa died: ‘going to preach the Gospel to the Ibiraj[ára] villages, they were attacked with arrows by the Carij[ó]s, barbarous and ferocious people, and their throats slit while kneeling in prayer’ ([1605] Citation1863, 483). This description appeared in a chapter, the title of which referred to the perished missionaries as martyrs, ‘How the Brothers Pedro Correa and Juan de Sosa were martyred in Brazil’ (ibid.).

Gouveia plainly rejected Ribadeneira’s claim that Correia and Sousa died as martyrs, citing the missing requisite of hatred of the faith. ‘Going to preach to the Carijós, a Spaniard had them killed by the Indians themselves, but not in odium fidei’ (Loyola Citation1904, 1:740–41; Leite Citation1938, 2:236–66, esp. 241). Moreover, he took the liberty of claiming that his brethren in Brazil shared his skepticism: ‘Not even here is it thought that they were martyrs’ (ibid.). In his (and, allegedly, their) estimation, the necessary elements were simply not present to satisfy Anchieta’s idealistic interpretation.

On the one hand, the Jesuits’ rhetorical construction of native Brazilians, outlined above, challenged the very possibility that they could kill missionaries out of a sustained hatred of Christianity. Furthermore, Ribadeneira’s claim that Correia and Sousa were martyred by ‘barbarous and ferocious’ Carijós was contradictory according to assessments like that of the Jesuit José de Acosta, who wrote that the Indigenous peoples of Brazil, among others, were too ‘barbarous’ to produce martyrs. Acosta wrote in his Latin treatise De procuranda indorum salute that missionaries murdered in Brazil were ‘not so much martyrs’ as ‘spoils of the chase’ (praeda ferarum) (Acosta Citation1984 [1588], 306), implying that cases like Correia and Sousa’s were destined to be forgotten.Footnote20

On the other hand, Anchieta’s convoluted, second-hand account, and later recapitulations of those events, failed to provide the clear binaries that made martyrdom narratives successful. Correia’s and Sousa’s deaths could be seen as the result of extensive hostilities between the Jesuits, labor contractors, and slave hunters, which intensified warfare among Indigenous groups, as John M. Monteiro influentially argued (Citation1994). The Castilian who supposedly ordered their killing was just one of the many settlers who begrudged the Jesuits’ control over the native population and regularly raided missionary villages and enslaved their inhabitants. Despite this conflict between the Jesuits and settlers, the Jesuits themselves were actively involved in Indigenous enslavement and financially dependent on enslaved labor, as Carlos Zeron has carefully traced (Citation2011).

The reality of Indigenous enslavement also tainted the slain missionaries’ case. Prior to joining the Society, Correia worked as an interpreter (in Portuguese, as a língua) and go-between in such slave raids. Provincial Nóbrega, eager to take advantage of Correia’s mastery of Tupi, was trying to have Correia ordained a priest at the time of his death and was seeking special dispensation, ‘for voluntary homicides [committed against] some Indians’ (cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:237).Footnote21 Visitor Gouveia was likely aware of the efforts to elevate Correia, and he corrected Ribadeneira for referring to Correia as a priest: ‘Pedro Correa was a brother and not a Father [i.e. a priest]’ (Loyola Citation1904, 1:740). If there were any doubts that the Catholic Church would allow Correia to be ordained, there must have been more that it would recognize him as a martyr.

Serafim Leite points to yet another layer of violence that complicated Correia and Sousa’s bid for the Church’s recognition. For him, its doomed status had more to do with Portugal and Spain’s political union in 1580 than lack of the requisite hatred of the faith (Leite Citation1938, 2:242). The Society of Jesus had little presence in Paraguay at the time of their deaths because it was a Spanish territory and the Jesuits, who typically reached those lands from Brazil, tended to be Portuguese. The Spanish and Portuguese monarchs were fearful of each other’s encroachment and disagreed upon the demarcation of Spanish Paraguay and Portuguese Brazil. After 1580, when Portugal and Spain were united under the crown of Philip II (r. 1556–1598), travel through these territories became easier for the Jesuits. For Leite, recognizing as martyrs two Portuguese Jesuits whose deaths could be blamed on a Castilian threatened to re-ignite the fires of internecine Iberian violence.Footnote22 In the end, then, inter-Iberian conflict was perhaps as decisive an obstruction to successful martyrdom as inter-Indigenous conflict.

Decades after the fact, Jesuit chroniclers would nevertheless attempt to enshroud Correia’s and Sousa’s deaths in the legitimizing aura of antiquity, forcefully arguing that similarities between their demise and those of certain early martyrs compensated for the apparent lack of an adequate motive. In his Chronica da Companhia de Jesus no Estado do Brasil (Citation1663/Citation1865), Simão de Vasconcelos (1596–1671), following Saint Thomas Aquinas and others, pointed out that the martyrdom of the Holy Innocents did not strictly speaking fulfill the requirement of hatred of the faith either. He wrote, ‘Oh Castilian, what does it matter that you murdered with a hidden hand? Herod worked through others’ hands, yet the caretaker of chastity was illustrious with all the martyrs. The cause of martyrdom is not in your hand; it is in your intention, which was detestation of purity’ (Vasconcellos [Citation1663] Citation1865, 101). Vasconcellos’s ambitious bid was no less than to raise Sousa and Correia—two temporal co-adjutores (laymen who were not fully professed members of the Society), the former who served as a cook in the Society and the latter a língua with a troubled past—to the status of the male children massacred on Herod’s orders, who had exceptionally escaped the in odium fidei requirement (Leite Citation1938, 2:240).Footnote23

Vasconcellos again ambitiously hailed Correia and Sousa—‘Oh blissful souls! Oh happy martyrs!’—as martyrs in the mold of the ancients when he reported that they were shot by arrows and killed ‘as that other martyr, Saint Sebastian,’ who, by tradition, died when he was shot with arrows under the Roman emperor Diocletian’s persecutions (Citation1865, 151; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294). With this, an overly optimistic Vasconcellos compared two little-known missionaries to one of the most celebrated martyrs on the Iberian Peninsula, above all in Portugal. In 1554, the heir-apparent to the throne, Sebastião (r. 1557–1578), was said to have been miraculously born on the saint’s feast day and was subsequently named in his honor. Before him, Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460), Grand Master of the Order of Christ, had used the Convent of Christ in Tomar, and the massive painting of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom it housed, to strengthen the knights’ desires to conquer and evangelize ‘heathen’ populations overseas.Footnote24 The comparison of two low-ranking Jesuits in Brazil, which the Portuguese crown valued far less than its other territories, to this saint was unconvincing.

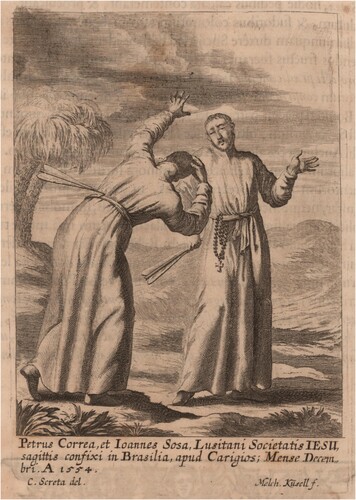

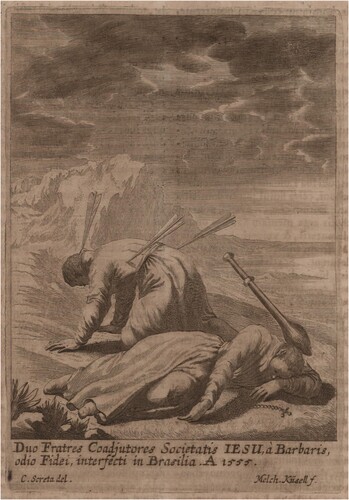

By the late seventeenth century, there were enough dead Jesuit missionaries the world over to supply an entire martyrology of contemporary holy deaths published by the Bohemian Jesuit Matthias Tanner as Societas Jesu usque ad sanguinis et vitae profusionem militans … (Citation1675), which included images by the Augsburg engraver Melchior Küsel. Among them, an image of Correia and Sousa pierced with arrows () continued to evoke Saint Sebastian, even if there were significant differences between the robed Jesuits and popular depictions of the saint, which showed Saint Sebastian scantily clad and tied to a tree. Even as Tanner persisted in hailing Correia and Sousa as martyrs, his account inadvertently revealed their case’s decline into oblivion: his hagiography featured a separate entry for two coadjutant brothers who perished in the sertão in 1555, one year after Correia and Sousa died (). Reports of these Jesuits’ deaths have not been found, and scholars have argued that they never existed—Tanner mistakenly duplicated Correia’s and Sousa’s supposedly illustrious deaths, confusing them with reports of two faceless and unnamed coadjutors dying in the interior (Leite Citation1938, 2:242; Page Citation2018, 73).

Figure 1 ‘Petrus Correa et Joannes Sosa.’ Pero Correia and João de Sousa are pierced by arrows. In Tanner Citation1675, 438. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Figure 2 ‘Duo fratres coadjutores.’ Two anonymous Jesuit co-adjutores, one shown struck by arrows, the other beaten by a club. In Tanner Citation1675, 441. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Tanner’s mistake reveals how Correia and Sousa’s case was so little celebrated that they had become anonymous in their own story. A century after Anchieta hailed them as ‘two stones’ providing the foundation for the ‘new Church,’ the details of their deaths were past recollection, as only one brother lies struck with arrows and the other shown beaten with a club-like weapon resembling the ibirapema or macaná. Perhaps what most meaningfully remained of Correia and Sousa’s case was the wish that the so-called ‘barbarians’ who killed them had done so for reasons that merited the glories of martyrdom. In , the caption below Küsel’s image ominously claims what the Jesuit José de Acosta had earlier claimed was impossible: that they died ‘a Barbaris odio Fidei’ (by barbarians who hated the faith; Citation1675, 441), as if the first entry in the book reflected what happened, and the second, with this caption, what they wished had taken place.

Brazil’s seaborne Church: a mirror of antiquity

In contrast with Correia’s and Sousa’s illegible deaths in the interior, the case of the forty Jesuits killed by Huguenot corsairs at sea in 1570 immediately benefitted from its similarities to ancient martyrs. The number forty evoked the well-known forty martyrs of Sebaste, also known as the Holy Forty, Christian soldiers said to have been killed in Lesser Armenia during the Roman emperor Licinius’s fourth-century CE persecution of Christians. When the local governor of Sebaste (now Sivas, Turkey) could not make the Christian soldiers apostatize, he allegedly ordered them to lie naked on a frozen pond on a bitter cold night. On this hardened body of water these Christian soldiers—forty in total—died, achieving the glories of martyrdom and, eventually, beatification. Roman soldiers were the perfect martyrs for the Jesuits to emulate since they considered themselves the foot soldiers of Christ.

Anchieta recalled ancient martyrs like the forty of Sebaste, and those popularly depicted on ships, like Saint Ursula and the 11,000 virgins, when he took the sea and its waters as a poetic backdrop for the new forty.Footnote25 In one poem, he construes the ocean as a metaphor for Christ’s redemption:

Ahogólos en la mar

el hereje, con furor.

Jesús, dulce Redentor

con esto quiso ahogar

sus pecados, con amor. (Anchieta Citation1998, 59)

En la mar pudo hundir

los cuerpos el matador,

mas al cielo con honor

las almas hizo subir

Jesús, dulce Redentor. (idem, 60)

Como tenías por guía

a Jesús crucificado

que a voces perdón pedía

para el pueblo, que lo había

en el madero enclavado

le ruegas muy inflamado

por tu matador francés.

Él quiere, por ti aplacado,

que gane vida el culpado

la muerte del portugués. (Anchieta Citation1998, 62)

The ocean was vital to popular devotion of the forty because of the sensation of proximity it produced between the martyrs and the people inhabiting the Brazilian coastline. In San São Salvador de Bahia, in 1574, the Jesuits designated the forty missionaries and laymen who foundered at sea the patrons of Brazil (Leite Citation1938, 2:264). This honor was far from self-evident, since the first group of men died close to the island of La Palma in what were known as the Fortunate Islands (present-day Canary Islands, where Anchieta was from), and the second closer to the Azores. In Brazil, since Europeans and their descendants overwhelmingly settled along the coast, and their livelihoods depended on the sea, the nearby Atlantic Ocean connected them to the martyrs. The centrality of ocean images in Anchieta’s poems, taken as a record of popular devotion, enabled Brazil to stake a claim to the martyrs for themselves and associate with depictions of them, even as La Palma and parts of Europe would do the same (Osswald and Hernández Palomo Citation2009, 134).Footnote26

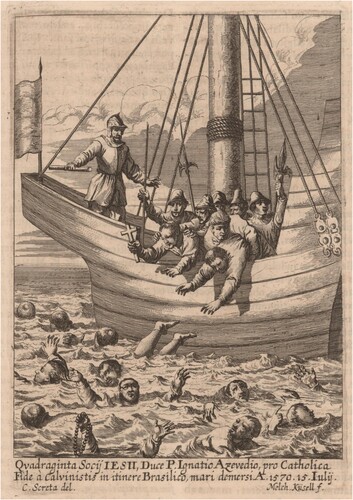

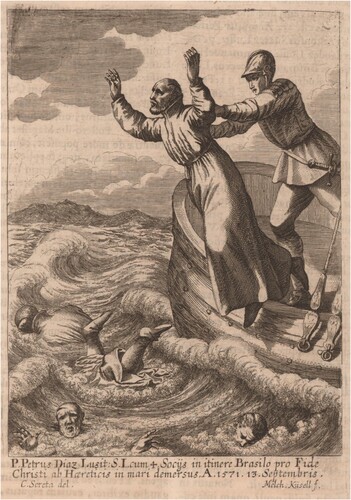

In the images of Tanner’s martyrology by engraver Melchior Küsel, no land mass comes into view, only water as far as the eye can see. The undulating, undifferentiated seascape seemingly erased the vast expanse between the Brazilian shores and the waters where the missionaries and laymen’s bodies languished.Footnote27 Much like the ocean helped the Jesuits collapse time—elevating the recently deceased to the status of ancient martyrs—it helped them overcome physical distance. What mattered to the Jesuits was not precisely where their brethren died but where their spiritual journey was leading them, and where they intended to go, which was Brazil.

A famous image that Azevedo carried on board with him provided a further link to the authority of antiquity: a copy of a miraculous icon said to date to the life of the Virgin Mary.Footnote28 The original icon (), which the pope later named the Salus Populi Romani Madonna, is housed in the Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. According to tradition, Saint Luke the Evangelist himself painted this portrait of Mary on a tabletop built by Jesus.Footnote29 The Jesuit Superior General Francis Borgia (r. 1565–1572) appealed to Pope Pius V to sanction the creation of official copies in honor of the Society’s special devotion to the image, which began with Ignatius of Loyola.Footnote30 This was the perfect devotional object for Borgia to entrust to the Jesuit missionaries he sent to establish the Catholic Church in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, not least because Saint Helena was said have discovered the image and brought it, together with sacred relics, to Constantinople, where it played a part in the ancient establishment of the Church. Breaking with custom, the pope granted approval in 1569, the very same year Borgia appointed Azevedo provincial of Brazil. Azevedo was thus the first Jesuit to set out with a copy of the Salus Populi Romani Madonna on a mission to establish the Catholic Church overseas, in the mirror of antiquity ().

Figure 3 Anonymous. Salus Populi Romani Madonna, sixth–tenth century, tempera on panel. Rome: Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Borghese Chapel. Photo: Wikipedia Commons.

Figure 4 ‘P. Ignatius Azevedius S.I.’ Ignatius de Azevedo stands pierced by a sword and holding the Salus Populi Romani Madonna. In Tanner Citation1675, 167. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

The exceptional status of this image later enabled the Jesuits to elevate the perished. On the one hand, the icon reinforced the interpretation of the forty Jesuits’ bodily demise and spiritual triumph as equals to that of ancient martyrs. On the other, since the copied image was considered as holy, miraculous, and authoritative as the original, the papal sanction amounted to an insurance policy. Any miraculous events attributed to the portrait of the Virgin Mary would carry the authority of Christian antiquity and would make the Jesuits on board the Santiago strong candidates for beatification and even sainthood in addition to martyrdom.

And miracles there were. Azevedo reportedly clutched the icon as the corsairs tried to pry it from his hands. Unable to remove it from his grasp, Sores’s men tossed Azevedo overboard. Witnesses claimed that as he drowned, Azevedo never let go of the image. In his 1570 letter, written from Madeira before his own death, Pero Dias wrote:

O primeiro, que mataram, foi o P. Inácio de Azevedo, que saíu a êles com a imagem [de Nossa Senhora] nas mãos,dizendo que êles eram católicos e êles eram luteranos e hereges e outras palavras. Derem-lhe com uma lança polacabeçacom que o cobriram de sangue, e a imagem, que trazia nas mãos, que era um retrato da imagem de NossaSenhora, que está em Santa María Maior, que fêz São Lucas, que trazia de Roma em uma lâmina de cobre, de queera muito devoto; depois lhe deram duas lançadas e, querendo-lhe tirar a imagem das mãos, nunca puderam. OPadre Diogo de Andrade se abraçou então com êle e mataram-nos ambos e deitaram-nos ao mar com a imagem nasmãos. (ARSI, Brasilina 15, f. 192r/v).Footnote31

Subsequent copies of the image—some claimed to be miraculous recoveries—produced crucial substitutes for the irrecoverable material remains of the forty’s bodies. These seaborne martyrs left few physical traces behind that the Jesuits could consecrate as relics. As Mia M. Mochizuki has argued, these images of the Virgin Mary were ideal replacements for bodily relics since, according to the Catholic doctrine of the Assumption (also attacked by Reformers like John Calvin [1509–1564]), Mary’s body ascended to heaven after her death, also leaving a bodily absence (Citation2017, 433). What is more, Azevedo’s story, combined with the papal sanction, turned the sacred icon into a sort of contact relic whose copies gave Brazil’s inhabitants a sense of great proximity to the martyrs. Not surprisingly, later hagiographical accounts even claimed that a Portuguese man came across Azevedo’s floating body, recovered the image clutched in his hands, and sent it to Brazil, where it was placed in the College of Bahia.Footnote32 The credibility of the story is irrelevant—Azevedo was tied to copies of the image since they were all sanctioned ‘originals.’

Anchieta’s commemoration of the martyrs dovetailed with his strong devotion to the Virgin Mary, which became known through his canticles (cantigas) and later disseminated by his biographers. Anchieta praised the Virgin Mary icon in a poem dedicated to Azevedo:

Con la Virgen en tu mano

¡oh Ignacio, varón fuerte!

peleaste de tal suerte

que del hereje tirano

triunfaste con tu muerte. (Citation1998, 61)

Cuando la Virgen María

quiso vencer el corsario

que las almas destruía,

ordenó que cada día

se rezase su rosario. (Anchieta Citation1998, 70)

In Brazil, other alternative remains echoing ancient times complemented the image. It was said that the Society had relics made of the wooden cross around which the deceased Jesuits had made their daily processions while training in Portugal (Cabral Citation1744, 129, as cited in Osswald Citation2010, 178). In this way, they again evoked the days of the early Church, when Saint Helena was said to have found the True Cross in Jerusalem, pieces of which became treasured relics throughout Catholic territories.Footnote33

The Jesuits shored up their master strategy of elevating the forty to the heights of the ancient martyrs through the interpretive frame of confessional conflict. Back in Europe, Catholics who died at the hands of the English, French, and German Reformers were increasingly presented as equals of the ancient martyrs. The Anglican Church was frequently compared with Ancient Rome as when Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) was popularly referred to as ‘England’s Nero.’ Henry VIII’s tyrannizing of Catholics sparked great interest in the early Christian martyrs and the devotional literature, images, and relics related to them.Footnote34 Sores, and later Capdeville, allowed the Jesuits in Brazil to claim that the heads of ‘heretical’ kingdoms afflicted them in the fashion of Roman emperors too, albeit through corsairs.

However lawless or self-interested the corsairs may have been, their connections to the French and English crowns allowed the Jesuits to paint them as persecutors of Catholics. A renowned Huguenot from Normandy, Sores was notorious for his murderous, destructive, and iconoclastic raids of the Spanish West Indies during the royally sanctioned hostilities between France and Spain of the 1550s (Lane Citation2016, 19–21). When Sores captured Havana in 1555, he was said to have desecrated the churches before burning them to the ground. In a letter to Philip II written shortly in 1570, Governor of Florida Pedro Menéndez de Avilés wrote that Sores was ‘Captain General of the sea against Catholics and in defense of heretics’ and ‘one of France and England’s best corsairs.’Footnote35 Menéndez de Avilés suggested that Sores was a military commander in the service of ‘heresy,’ and the pirate attack an extension of the confessional conflicts among the competing powers of the European landmass.

Anchieta’s poems, too, painted the forty’s deaths as their spiritual triumph over the ‘heretical’ Huguenots. He refers to the martyrs as ‘hosts [hostias, i.e. eucharists] of praise’ whose bodies were sacrificed like Jesus’s:

su mansedumbre siguiendo

sin temer ningún dolor,

hecho hostias de loor

vuestras vidas consumiendo

el hereje con furor. (Anchieta Citation1998, 59)

Over a century after the original events, visual images of the attack retained this confessional framing. Küsel’s images in Tanner’s martyrology show the missionaries and laymen being dramatically thrust overboard into choppy ocean water by figures resembling ancient Roman soldiers. In , one Jesuit defiantly stretches his hand above the water’s surface clutching a rosary. Another Jesuit holds a cross, appearing to bless, or perhaps administer last rites to, the men below. The images focus on the sea, in which the men appear to merely drown, contradicting reports that the corsairs slit their throats. In , Pero Dias is tossed into the waters, where feet and hands stick out of the oceanic abyss. In both, the heads of the doomed Jesuits bob in the water like buoys.

Figure 5 ‘Quadraginta Socii IESU, Duce P. Ignatio Azevedio, pro Catholica. Fide à Calvinistis in itinere Brasilico mari demersi.’ Forty Jesuits are thrown into the ocean from their ship. In Tanner Citation1675, p. 171. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Figure 6 'P. Petrus Diaz Lusit. S.I. cum 4 Sociis in itinere Brasilo pro Fide Christi ab Hareticis in mari demersus.’ Pero Dias is thrown into the ocean. In Tanner Citation1675, 174. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Accounts of Brazil’s missionaries being cast into the ocean, as hair-raising as they may have been, also offered Catholics spiritual solace because Sores and Capdeville were confirmed enemies of the Catholic faith. Sores met the martyrial requirement of in odium fidei and then some. As seen above, the Jesuit Provincial of Portugal Serrão asseverated that Azevedo and his companions died ‘in hatred of the faith and of the Catholic Church’ (cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:305n120).Footnote36 In the epistolary account he wrote prior to his own death, Dias emphasized that Sores and his men were motivated by confessional rage. He reported that Sores shouted, ‘Kill them, kill them, they are going to spread false doctrine in Brazil!’ (as cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:253–54). According to Dias, the corsairs threw the Jesuits into the water for the express reason of stopping the spread of Catholicism in the Portuguese colony.

These words attributed to Sores firmly re-inscribed Brazil within the context of confessional strife precisely when the Jesuit missions were themselves struggling. Around 1555, the French had established a short-lived colony, France Antarctique, near present-day Rio de Janeiro. According to Léry, these lands were a promised safe haven for Calvinists and Huguenots, who had no qualms about disregarding the papal bull that granted Portugal exclusive rights over them. From 1565 to 1567, the Portuguese destroyed the colony and drove out its French inhabitants in a battle they presented as the triumph of Catholicism over heresy. A few years later, Sores’s attack was an opportunity for the Jesuits to again tie Brazil to confessional conflict. Dias revived the confessional paradigm for Brazil by suggesting that the early fight was not over, and that Reformed Christians still vied to spread their beliefs there.Footnote37

As if encouraged by the prospect of rebuffing the ‘Lutherans,’ the inhabitants of Brazil hosted elaborate commemorative celebrations of the martyrs. Anchieta’s poems and canticles about Sores’s attack testified to the Brazilian cult.Footnote38 In his notebook, prior to the first poem, Anchieta wrote, ‘These were performed (se hicieron) at the fiesta of Father Ignacio de Azevedo,’ perhaps meaning that they were recited or sung (Citation1984, 92). They formed part of one or many of the celebrations that commemorated the day the forty died, 15 July, such as those reportedly held in São Salvador de Bahia in 1574.Footnote39

One of Anchieta’s poems in particular captures the fervor with which the people of Brazil celebrated their holy dead by conflating the original tragedy with its festive commemoration. In a poem dedicated to one of the forty, Manuel Álvares, Anchieta described him supposedly playing the drum as his Jesuit companions drowned, giving them a beat to which to achieve spiritual glory.

Viendo los buenos cristianos,

en las ondas de la mar,

fuertemente contrastar

a los malos luteranos,

que los quieren acabar,

para más los esforzar

en la fe de tu Señor,

con increíble fervor,

no cesando de gritar,

bien tocas el atambor. (Citation1998, 66)

The watery deaths of the forty gave the Jesuit province of Brazil its first rock-solid martyrdom case. For Anchieta, these holy men’s tragic end made them the true pillars of the Catholic Church in Brazil. In the lyric poem that opens this article, he compared the martyr Pero Dias to stone and marble, a comparison that reflected the strength of their case for martyrdom. That poem continues,

No sea tu alma esquiva

contra la penosa cruz

abrazada de Jesús,

piedra mármol y luz viva,

si quieres firmeza y luz. (Anchieta Citation1998, 68)

The poem closes by focusing on the bedrock of the forty’s case and, following Saint Augustine, all early modern martyrdom campaigns: a hateful adversary.

Como siguió en su vivir

a Jesús, su buen amigo,

fue de él tan fiel testigo,

que por él vino a morir

en manos del enemigo. (Anchieta Citation1998, 69)

Anchieta and his companions’ confidence in this martyrdom campaign subverted the well-known Iberian literary tropes of the tempestuous, unpredictable sea. Since ancient times, the sea had been a metaphor for mutability, especially in epic poems, from its use as a potent metaphor for instability in the Aeneid and tempestuous anger in the Odyssey. In the early modern Portuguese world, Camões’s 1572 epic Os Lusíadas, often compared to the Aeneid, glorifies Vasco da Gama’s (1469–1524) ‘subjugation’ of the sea route to India by recounting the oceanic tempests he overcomes (Blackmore Citation2022, 53). In Bento Teixiera’s (1561–1600) classicizing epic Prosopopeia (Citation2021 [1601]), which imitates Os Lusíadas, the ‘hero’ Jorge de Albuquerque Coelho also tempts fortune at sea. An image of the treacherous and untrustworthy sea abounded in shipwreck narratives, which circulated widely and have received considerable attention from scholars. This dominant image of the sea as the apotheosis of uncertainty has obscured the fact that, for the sixteenth-century Jesuits of Brazil, the sea was a more constant and reliable producer of indisputable martyrdoms than the protean and unnavigable sertão. The Atlantic seascape, riddled with French and English corsairs, functioned as the only stable ground upon which they could hope to establish the Catholic Church in Brazil through martyrs.

Deeming that they had successfully imitated Christ, current and prospective Jesuits and other Catholics in turn sought to imitate the forty martyrs of Brazil, demonstrating that they had entered the echo chamber of successful martyrdom narratives. After word of Sores’s and Capdeville’s ambushes spread throughout Europe, there was a sharp increase in the number of Jesuits who requested to be sent to Brazil. In their letters, they unequivocally expressed their desire to meet the same end as Azevedo and Dias (Costa Citation1957, 443; Osswald and Hernández Palomo Citation2009, 133n16).Footnote40 If prospective missionaries had been deterred by the lack of opportunity for spiritual triumph in the Brazilian sertão, they now took solace in the possibility of achieving the highest glory on their oceanic journey there. The prospect of martyrdom inspired Jesuits to voyage to Brazil despite the daunting tasks in the vast interior that awaited those who arrived safely.

The strength of the forty’s case also made it a model for future martyrdom campaigns. It was said that the five Jesuit martyrs of Salsete in Goa, India, perished on 25 July 1583 but were officially associated with 15 July to make their deaths coincide with the date on which the martyrs of Brazil perished (Benci Citation2018; Osswald and Hernández Palomo Citation2009, 141–42). Much later, the number forty was again echoed when those who died in England’s sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century persecutions of Catholics were beatified as the ‘Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.’ Since the narrative of the forty’s death had convincingly mirrored that of ancient martyrs, they in turn became a new measure of promising martyrdom candidacy to others, partaking in what Ulrike Strasser calls an ‘imitation game’ (Citation2015).

Miraculous visions on the Iberian Peninsula helped carry the forty’s case and tied it to further campaigns. Teresa of Ávila told her confessor, Baltasar Alvarez (1560–1630), that, at the time of the forty’s deaths, she had a vision of dozens of men wearing martyrs’ crowns in heaven (Osswald Citation2010, 166–67). The meaning of her vision was later clarified when the news arrived of the tragedy on the Santiago, in which the life of a relative of hers was claimed. Teresa had previously expressed her desire to physically experience martyrdom and this vision brought her closer to the martyrial realm, even if, from the Carmelite convents of Spain, she had fewer chances of personally experiencing violent death (Moltmann Citation1984, 265). The canonization process for Teresa, a towering figure of post-Tridentine spirituality, was bolstered by this miraculous vision, in turn supporting the forty’s case.

On the heels of such auspicious beginnings, and in a show of great confidence, the Brazilian province helped finance the beatification campaign of the forty martyrs in the early seventeenth century (Alden Citation1996, 641). The forty’s spiritual edifice showed signs of resilience and popular devotion to the perished missionaries and laymen was reportedly widespread. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, it was said that children sang of their virtues in the streets of Bahia (Osswald and Hernández Palomo Citation2009, 134). In Mexico City, a triumphal cart dedicated to the Catholic faith's triumph over heresy featured representations of Azevedo and Dias in the 1610 festivities for Ignatius of Loyola's beatification and the consecration of a new church (Pérez de Ribas Citation1896, 1:247).

The setting of martyrdom had changed for the Jesuits in Brazil. They had come a long way from early writings such as Nóbrega’s Diálogo (1556–1557) which lamented their inglorious and dangerous task of converting ‘barbarous and untamed’ people (Anchieta Citation1984, 76–77). Historical conditions would continue to carry their oceanic martyrs’ case forward. As confessional conflict intensified between Spain and England, the seaborne martyrs’ case flourished as that of their companions who perished in the sertão fizzled. The Catholic Church’s new focus on countering the Reformed churches gave the Jesuits the opportunity to create a foundation for the Church in Brazil, in the mirror of antiquity, through triumphalist martyrdom narratives. The spiritual edifice that crumbled to the ground in the sertão was being successfully built at sea.

Jesuit martyrdom on land and at sea

Anchieta and his counterparts’ constructions of land and sea in early martyrdom accounts evoke later formulations that loom large in the Brazilian cultural imaginary. One emblematic formulation arose from the separatist religious community Canudos, in the arid northeastern sertão, at the turn of the twentieth century. It was said that the community’s messianic leader, Antônio Conselheiro, made a prophecy about the End of Times in which everything would become its opposite: ‘The backlands (sertão) will turn into the sea and the sea into backlands’ (Cunha Citation1902). This famous phrase appears in the magnum opus, Os sertões (Citation1902) by Brazilian engineer-turned-writer Euclides da Cunha (1866–1909).Footnote41 Cunha himself portrayed the Amazonian sertão between Brazil and Peru as ocean-like, writing that the typical observer’s gaze tires of its ‘unbearable monotony’ and ‘endless horizon as empty and undefined as that of the sea’ (Citation2006, 6).

This wholesale inversion of the sertão and the sea in Brazil stretched back to the colonial period, when authors metaphorically flipped the sertão with the treacherous ocean as popularized in classical antiquity and revived in Camões’s epic poem, Os Lusíadas. Most notably, Fray Santa Rita Durão took the sea-based Os Lusíadas as the model for his epic poem Caramuru (Citation1961 [Citation1781]) about the life of the castaway Diogo Álvares Correira, better known as Caramuru, in the backlands among the Tupinambás. As early as 1616, a bandeirante (slave and fortune hunter in the interior) jotted down lines from Camões’s poem and compared his penetrations of the sertão near the Paraupava River (actual Araguaia River) to Vasco da Gama’s maritime navigations (Fernandes Citation2002, 270). By appropriating Camões’s portrayal of the sea, these colonial authors recast the Brazilian interior as a treacherous ocean and its navigators, sea captains.

In contrast with formulations that worked by inversion, land and sea were vitally inter-connected for Anchieta and his fellow Jesuits, for a simple reason—martyrdom was not the Society’s highest goal in Brazil. More than once the Superior General reminded overly zealous Jesuits that they were on mission to save souls as much if not more than to assure the salvation of their own souls by dying holy deaths. The upper ranks cautioned prospective missionaries against the hubris that could drive them to seek the crown of martyrdom (Russell Citation2020, 91). As Ines Županov has shown, superiors promoted everyday suffering in the Asian missions as the ideal form of martyrdom, as opposed to a rapid, violent death (Citation2005, 147–71). Even as the Jesuits in Brazil promoted their seaborne martyrs, their higher goal remained to continue the work of converting new souls, an enterprise that would take place on solid land.Footnote42

If stone metaphors reflected the solidity of seaborne martyrdom cases—their fulfillment of its traditional requirements and the strength of their candidacy for official recognition—another poetic image that proliferated in the sertão reflected the utility of holy deaths for the Jesuits’ greater ambition, however ill-fated they were for Church recognition. That poetic image was their ‘fertility,’ and it dates to the early Carthaginian Christian apologist Tertulian, who wrote around the turn of the second century that ‘semen est sanguis Christianorum’ (the blood of Christians is the seed).Footnote43 The Jesuits who chronicled inland deaths echoed Tertulian’s words, as when Anchieta wrote that Correia and Sousa were soaked in ‘glorious blood’ (Anchieta Citation1933, 82; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294) and Vasconcellos ([Citation1663] Citation1865) extolled the spiritual benefits that would be reaped from Correia’s and Sousa’s deaths: ‘with your blood you fertilized those forests, with your example they become attractive: and the day will come when this blood will yield great harvests among these peoples’ (idem, 101; English from Cymbalista Citation2010, 294).

The Jesuits continued to celebrate their fallen missionaries in the sertão and promote their potential to bring about the conversion of native peoples regardless of Correia and Sousa’s narrative failures. In 1628, general judge (procurador general) Juan Bautista Ferrufino wrote that the deaths of three priests in the Province of Paraguay in 1628 were ‘the first fruit of those extensive provinces, which, having already been watered with blood, hope to advance many others with their fertility’ (Armani Citation1988, 58–61, as cited in Cañeque Citation2020, 311). Even if it proved easier to construct martyrdom narratives at sea in the first decades of the Jesuit mission in Brazil, the Jesuits persisted in wanting the ‘seed’ of their holy dead to sprout on Brazilian soil, bearing spiritual ‘fruit’ in their missionary enterprise.

The contrasting metaphors of the earliest martyrdom candidates in Brazil—stone-solid seaborne candidates, on the one hand, and blood-soaked and fertile inland deaths, on the other—also reflect different measures of martyrdom’s ‘success.’ Officially recognized martyrdom was not necessarily indicative of the Jesuits’ evangelical success and could in fact signify the opposite. The rapid canonization of the martyrs of Nagasaki in 1627 can be seen as a sort of ‘consolation prize’ for the utter failure of the mission to Japan (Zampol d’Ortia Citation2020, 164). By the same token, martyrdom cases in the sertão that failed narratively—their candidates were not raised to the altars, as it were—may nevertheless reflect evangelical ‘success,’ from a Catholic and Jesuit perspective. Charlotte de Castelnau L’Estoile finds it remarkable that the Society did not push the martyrdom candidacy of the Jesuit missionary Francisco Pinto, who suffered violent death at the hands of Indigenous peoples, known to Europeans as ‘Tapuia,’ from Sierra d’Ibiapaba (today Ceará). For her, Pinto was perhaps overlooked because he was seen as too versed in native customs to sway the Vatican (Castelnau L’Estoile, Citation2006).

Despite their frustrations with inland martyrdom candidates, the Jesuits did not give up on the sertão as a space for conversion, as the consolidation and expansion of the mission system among the Guaraní in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries testify. The Jesuits’ early narratives of the seaborne martyrs may very well have been intended to further efforts in the sertão, as they in fact did when one Jesuit reported having a miraculous vision of the forty’s martyrdom at sea as he journeyed into the Paraguayan interior in 1616 (Osswald Citation2010, 174). At sea, corsair attacks ebbed and flowed, and other types of deaths occurred, but the Jesuits had a sustained commitment to converting native populations. The narrative ‘ground’ of the ocean needed the literal, if narratively ‘infertile’ land of the sertão to be generative, and the port towns and cities where they were celebrated brought these two spaces together. Without literal land to evangelize on, to hold festivals on, to erect churches on, there was little point to spiritually building a Church at sea. Land and sea bled into each other even as their metaphors, at times, separated them.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Stanford-Tinker Faculty Research Fund offered by the Center for Latin American Studies at Stanford University.

I want to thank the two anonymous reviewers and CLAR editor Dana Leibsohn for expertly guiding this piece to its final form. This article benefitted from conference panels organized by Caroline Egan, Lexie Cooke, and Juan Carlos Mantilla at the RSA and LASA conferences, presentations at the Center for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Stanford University, and workshops with the MEMIC research collective and the Stanford Humanities Center. Special thanks to Leonardo Velloso-Lyons, Lexie Cooke, Noel Blanco Mourelle, Miguel Ibáñez-Aristondo, Juan Carlos Mantilla, David H. Colmenares, and Mariana Meneses for closely reading the piece, and João Adolfo Hansen, Charlotte Castelnau L’Estoile, Carlos Zeron, Renato Cymbalista, and Andrea Daher for conversations that led to key insights and resources.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicole T. Hughes

Nicole T. Hughes is Assistant Professor of Iberian and Latin American Cultures at Stanford University. Her research focuses on the early modern world, especially sixteenth-century New Spain (Mexico) and Brazil. She has received support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (Mellon Humanities International Fellow), the John Carter Brown Library, and the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut in Berlin. Previously, she was a Mellon Scholar in the Humanities at the Stanford Humanities Center.

Notes

1 Original text is found in Archivum Societatis Jesu Romanum [hereafter ARSI], Brasilina 15, fs. 213–14.

2 He descended from the Malafaya and the Azevedos (Alcázar Citation1710, i; Osswald and Hernández Palomo Citation2009, 143n69).

3 See Ditchfield Citation2012.

4 Cymbalista argues that martyrdom was part of the Jesuit imaginary since its beginnings whereas Russell considers that a ‘martyrological sensibility’ became more prominent as Jesuits increasingly suffered violent deaths (Cymbalista Citation2011, 164; Russell Citation2020, 98).

5 Loyola was badly injured during the Siege of Pamplona (1521). Shortly after recovering his strength, he discovered Thomas à Kempis’s Imitatio Christi and began formulating the Spiritual Exercises (O’Malley Citation1993, 23–37).

6 On Xavier and Criminale’s deaths, see Županov Citation2005, 35–86, 147; 171.

7 For Gregory, the Church was reluctant to makes saints of Catholics executed in Reformed lands (Gregory Citation1999, 292). Thomas James Dandelet argues that leading a holy life and the performance of miracles came to replace martyrdom as the primary path to sainthood (Citation2021, 160–87). Burke notes the surprising lack of martyr-saints in this period given how many Catholics suffered violent deaths (Citation1999, 139).

8 Original text is found in ARSI, Brasilina 15, fs. 213–14.

9 Pope John Paul II beatified Anchieta in 1980 and Pope Francis announced his canonization in 2014.

10 This is striking given that Brazilian literary historiography in the early twentieth century saw him as a foundational figure. For example, the polymath Afrânio Peixoto dubbed Anchieta the ‘initiator’ of Brazilian literature (Peixoto Citation1933, 26).

11 Original text is found in ARSI, Lusitania 43, f. 423v.

12 The literature is vast. For bibliography on Camões, see Alves Citation2020. Boxer’s notion of the Portuguese ‘seaborne empire’ (Citation1969) is considered foundational. For more recent approaches, see Blackmore Citation2002; Citation2022; Voigt Citation2009; Barletta Citation2019.

13 On the early modern valences of this term, see Saramago Citation2016; Velloso-Lyons Citation2022, 46–60.

14 This contrasts with the later Jesuit writings that used ‘hardness’ as a metaphor for stable conversion studied by the Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (Citation2011, 1).

15 On the Jesuits’ rhetorical construction of the native Brazilian and the ‘Indian soul,’ see Hansen Citation2006. On the objectification of Brazil, see Greene Citation1999. On Nóbrega’s Diálogo, see Hansen Citation2006; Pécora Citation2018.

16 On the complexity of the ethnonym Temiminó and the question of ethnogesis, see Almeida Citation2013, 60–75.

17 The Brazilian Province was described as a ‘sterile, laborious, and dangerous vineyard’ (Castelnau L’Estoile Citation2000, 9).

18 Anchieta's original Latin letter to Loyola was lost and its contents are known through a Spanish copy published in Copia Citation1556 (Leite Citation1956a, 2:202–3). See also a letter from Loyola to Pedro de Ribadeneira on recent news from Brazil (Leite Citation1956b, 2:263–65).

19 On the uses of Jesuit letters, see Palomo Citation2005; Hoyos Hattori Citation2015.

20 On the ‘wasted charity’ of certain martyrs in Acosta, see Legnani Citation2020, 180–81.

21 Original text found in ARSI, Brasilina 3 (1), f. 96v.

22 See Santos Pérez Citation2014; Schwartz Citation1968; Vainfas, Citation2017. The assassin may have had ties to Rui Mosquera, who had previously violently challenged the demarcation of Spanish and Portuguese territories (Leite Citation1938, 2:241).

23 On social status and canonization, see Burke Citation1999. Although it appeared from Europe that all Jesuits overseas were missionaries, only a limited number of lower-ranking Jesuits preached in the interior (Castelnau L’Estoile Citation2006, 618).

24 This painting by Gregório Lopes, known as the Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, was originally executed for the Convent of Christ in Tomar c. 1536, five years after a relic of the saint was translated from Rome to Lisbon (Trindade Citation2016).

25 Anchieta composed an auto about the 11,000 virgins (Citation1977, 276–84).

26 In 1632, they were named the patrons of the La Palma island (Osswald Citation2010, 169). They are also known as the martyrs of Tazacorte after the last place they celebrated mass on land.

27 On the collapsed distance between the East and West Indies, see Padrón Citation2020.

28 The original copy, by João de Mayorca, was lost at sea; see Mochizuki Citation2016, esp. 1:136.

29 Conflicting dating of the image ranges from the sixth through the tenth centuries. The image received the title Salus Populi Romani Madonna c. 1870 from Pope Pius IX. See Belting Citation1994, 68–72; Ostrow Citation1996, 123–24, 314–15, 315n15; Wolf Citation1990, 24–28.

30 On the Salus Populi Romani Madonna as a ‘networked image’ and part of an ‘image chain,’ and on the earliest copies, see Mochizuki Citation2022, 118–38.

31 The first one they killed was Father Inácio de Azevedo, who came out towards them with an image [of Our Lady] in his hands, saying that they were Catholics and the other men were Lutherans and heretics and other words. They struck him on the head with a spear, leaving him covered in blood, and the image, which he was carrying in his hands, was a portrait of the image of Our Lady that is in Santa Maria Maggiore, which Saint Luke made, which he had brought from Rome on a copper plate, [and] to which he was very devoted; they struck him twice and, trying to wrest the image from his hands, they never managed. Father Diogo de Andrade then embraced him, and they were both killed and thrown into the sea, with the image [still] in his [Azevedo's] hands. (cited in Leite Citation1938, 2:253–54).

32 The Jesuit António Franco (1662–1731) recounts in his Imagem da virtude … (Lisbon, 1714) that the Portuguese man retrieved the image with ease from Azevedo’s clutches, hid it from the ‘heretics,’ and later, on the island of Madeira, handed it to the Jesuits who then brought it to the College of Bahia (Franco Citation1890, 107; Cymbalista Citation2010, 295). Scholars believe the ‘miraculous image’ is a copy created around 1575, the date of the earliest reported celebrations in Brazil (Mochizuki Citation2016, 1:136).

33 On how the early Jesuits in Brazil used relics to ‘imprint the old on the new,’ see Cunha Citation1996.

34 See Cañeque Citation2020, 71–129. For a comparison of contemporary and ancient martyrdom in Anchieta’s lyric poetry and autos, see Egan Citation2020.

35 See Pablo Citation1955.

36 Original text found in ARSI, Lusitania 43, f. 423v.

37 The Dutch presence in the early seventeenth century proved this right.

38 Armando Cardoso and Carlos Brito Díaz, among others. See Anchieta Citation1998, 57; Citation1984, 92.

39 Armando Cardoso speculated that this poem was a song that opened an entremés about Pero Dias (Anchieta Citation1977, 193–202).

40 ARSI, Lusitania 64, fs. 200, 204–5.

41 It is also the basis for the final scene of director Glauber Rocha’s classic cinema novo film, Deus e o diabo na terra do sol (Citation1964).

42 See Cymbalista Citation2017, esp. 133–67.

43 For a critique of the literal and figurative place of blood in Christianity, see Anidjar Citation2014.

Bibliography

- Acosta, José de. 1984. De procuranda indorum salute: pacificación y colonización. Edited by Luciano Pereña Vicente. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

- Alcázar, Bartolomé. 1710. Chrono-historia de la Compañía de Jésus en la Provincia de Toledo y elogios de sus varones. Madrid: Juan García Infanzo\n.

- Alden, Dauril. 1996. The making of an enterprise: the Society of Jesus in Portugal, its empire, and beyond, 1540–1750. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Almeida, Maria Regina Celestino de. (2013). Metamorfoses indígenas: identidade e cultura nas aldeias coloniais do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV.

- Alves, Hélio J. S. 2020. Luís de Camões. In Oxford bibliographies in Renaissance and Reformation. 25. https://www-oxfordbibliographies-com.stanford.idm.oclc.org/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0313.xml.

- Anchieta, José de. 1933. Cartas, informações, fragmentos históricos e sermões do Padre Joseph de Anchieta, S.J. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Anchieta, José de.. 1977. Teatro de Anchieta. Edited by Armando Cardoso. São Paulo: Edições Loyola.

- Anchieta, José de.. 1980. Poema da bem-aventurada Virgem Maria, Mãe de Deus [1563]. Edited by Armando Cardoso. São Paulo: Edições Loyola.

- Anchieta, José de.. 1984. Lírica espanhola. Edited by Armando Cardoso. São Paulo: Edições Loyola.

- Anchieta, José de.. 1998. Poesías líricas castellanas. Edited by Carlos Brito Díaz. La Laguna: Instituto de Estudios Canarios.

- Anidjar, Gil. 2014. Blood: a critique of Christianity. New York: Columbia University Press.