?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives

Stress is not inherently negative. As youth will inevitably experience stress when facing the various challenges of adolescence, they can benefit from developing a stress-can-be-enhancing mindset rather than learning to fear their stress responses and avoid taking on challenges. We aimed to verify whether a rapid intervention improved stress mindsets and diminished perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity in adolescents.

Design and Methods

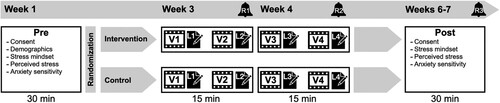

An online experimental design randomly exposed 233 Canadian youths aged 14–17 (83% female) to four videos of the Stress N’ Go intervention (how to embrace stress) or to control condition videos (brain facts). Validated questionnaires assessing stress mindsets, perceived stress, and anxiety sensitivity were administered pre- and post-intervention, followed by open-ended questions.

Results

The intervention content successfully instilled a stress-can-be-enhancing mindset compared to the control condition. Although Bayes factor analyses showed no main differences in perceived stress or anxiety sensitivity between conditions, a thematic analysis revealed that the intervention helped participants to live better with their stress.

Conclusions

Overall, these results suggest that our intervention can rapidly modify stress mindsets in youth. Future studies are needed to determine whether modifying stress mindsets is sufficient to alter anxiety sensitivity in certain adolescents and contexts.

Introduction

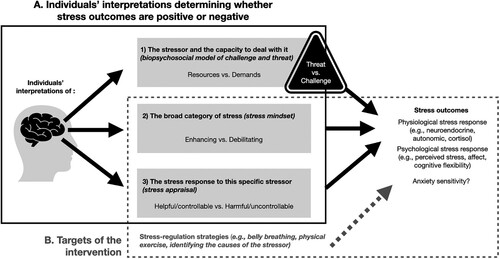

Experiencing stress is unavoidable given its role in energy mobilization necessary to deal with perceived environmental threats or challenges (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Selye, Citation1976). As adolescence is a developmental period where challenges are magnified by biological, social, and identity transformations (Dahl et al., Citation2018), youth are more likely to experience high levels of stress (Romeo, Citation2013). Though stress can be impairing (Lupien et al., Citation2009), optimal stress levels can also be enhancing across several domains (Cassady & Johnson, Citation2002; Chaby et al., Citation2015; Dienstbier, Citation1989; Jamieson, Citation2017; Lupien & McEwen, Citation1997). Stress can lead to either positive or negative outcomes depending on individual subjective interpretations about (1) the nature and extent of the stressor and capacity to deal with it, (2) stress in general (i.e., stress mindset), and (3) the stress response when faced with this specific stressor (i.e., stress appraisal). The left part of (A) depicts these subjective stress-related interpretations.

The biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat specifies that individuals experience stressful performance-motivated situations as either challenging or threatening depending on cognitive appraisals (for a review, see Jamieson, Crum, et al., Citation2018). Challenge type stress responses manifest when resources are perceived as surpassing situational demands, whereas threat occurs when demands exceed the resources. Stress mindsets are described as individual meta-cognitive processes that shape how a person interprets the overall meaning of stress as being either debilitating (negative) or enhancing (positive; Crum et al., Citation2013). In turn, when confronted with specific stressful situations (e.g., academic test), stress mindsets shape whether individuals appraise their stress responses as either helpful/controllable or harmful/uncontrollable (Jamieson et al., Citation2013; Yeager et al., Citation2016). Individuals who have a positive stress mindset tend to perceive specific stressful situations as being more challenging than threatening (Kilby & Sherman, Citation2016) as their stress responses in these situations are appraised as additional resources (Jamieson, Hangen, et al., Citation2018). Compared to individuals who have negative stress-related interpretations, individuals who experience stressors as challenges/have a positive stress mindset have been shown to experience several positive outcomes of stress. Examples of such outcomes include a more adaptive physiological stress response (Crum et al., Citation2013; Yeager et al., Citation2022), more positive affect, greater cognitive flexibility, enhanced productivity (Crum et al., Citation2017), active coping (Jamieson et al., Citation2013), and greater academic performance (Keech et al., Citation2018).

However, given that most scientific papers, the media, and people’s lay theories mainly focus on the harmful effects of stress (Crum et al., Citation2020; Liu & Vickers, Citation2015), it is commonly taught to adolescents that “stress should be avoided at all costs” (Pope, Citation2003). Such conceptions, which are remarkably similar to stress-is-debilitating mindsets, may have conditioned some youth to perceive their stress responses as threats they should fear, a concept known as anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety sensitivity is described as an individual’s tendency to fear physiological stress response sensations (e.g., sweating, heightened arousal, elevated heart rate; McNally, Citation1990; Reiss et al., Citation1986). This fear arises from the belief that these sensations will cause illness, embarrassment, or loss of control (Watt & Stewart, Citation2009). Importantly, adolescents with high levels of anxiety sensitivity experience more of the harmful outcomes of stress. As such, they tend to perceive more tension when faced with a psychosocial stressor, though their physiological stress responses are not greater than those with low levels of anxiety sensitivity (Wearne et al., Citation2019). Later in life, this discrepancy between adolescents’ subjective and physiological stress responses places them at higher risk of developing an anxiety disorder (McLaughlin et al., Citation2007; Schmidt et al., Citation2010). This raises the question of how we can modify such negative beliefs about stress in youth.

A growing body of laboratory and field studies has shown that certain rapid interventions can manipulate the psychological processes by which people make sense of themselves, the world, or any situation they face. These interventions are called “wise” interventions (Walton & Wilson, Citation2018). Crum et al. (Citation2013) conducted one of the first studies to test a wise intervention targeting stress-related interpretations. Results showed that exposure to 3-minute videos summarizing the positive effects of stress was able to transform the stress mindsets in a sample of adults into more stress-can-be-enhancing mindsets. In turn, these changes induced a more adaptive hormonal stress response (i.e., cortisol levels) when these same adults were exposed to a laboratory psychosocial stressor. In the same vein, Yeager et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated similar results, notably when testing high school students in classroom settings. In this study, a 30-minute self-administered online intervention synergistically manipulated different mindsets of the participants (i.e., stress mindsets and growth mindsets – stressors are helpful to learn how to overcome difficulties) in order to target stress appraisals (e.g., physiological manifestations of stress are additional resources that the body releases to overcome difficulties) in specific acute stress contexts (e.g., academic evaluations or assignments). Compared to previous interventions that passively exposed participants to information about stress, the wise intervention developed by Yeager et al. (Citation2022) actively encouraged participants to apply the content to their own lives using a daily exercise in which participants wrote about the stressors experienced. In sum, the intervention successfully diminished hormonal indicators of unhealthy responses to stress over 14 days, and improved academic performance and psychological well-being.

It is unclear whether the modification of stress-is-debilitating mindsets specifically affects adolescents’ stress mindsets or translates to anxiety sensitivity (i.e., fear of experiencing stress responses) more globally. As negative stress mindsets and anxiety sensitivity both arise from beliefs about the negative effects of stress, modifying the former may simultaneously modulate the latter. Nonetheless, anxiety sensitivity may be a more stable tendency in adolescents that could remain unaffected by wise interventions on stress mindsets. Furthermore, even adolescents who generally reappraise their stress responses as an additional resource to cope with encountered challenges might be reluctant to do so in certain stressful situations that are perceived as either negative or too overwhelming (e.g., heartbreak, high school graduation). As these situations are normal and likely to occur, adolescents may eventually stop believing in the stress-can-be-enhancing mindset. Teaching adolescents about effective strategies that can regulate the intensity of a stress response could contribute to the solidification of positive stress mindsets and help them engage with difficult challenges. Examples of such strategies include belly breathing, physical exercise, and identifying the causes of the stressor (Lupien et al., Citation2013). Learning these strategies could allow adolescents to successfully implement a positive stress mindset even in highly stressful situations by strengthening the idea that they have control over their stress responses to benefit rather than harm them in stressful contexts. Moreover, acquiring this additional type of stress knowledge could perhaps also reduce adolescents’ anxiety sensitivity by increasing their comprehension of stress and familiarity with its manifestations.

Extending prior work on stress mindsets, we created a series of four short videos for adolescents by combining concepts from synergistic mindset approaches and adding information on effective strategies to regulate a stress response. This pre-registered study aimed to verify whether a 4-video wise intervention modified stress-is-debilitating mindsets, as well as stress and anxiety sensitivity in Canadian adolescents aged 14–17 compared to a video control condition. After conducting pre-registered analyses, we added a supplementary objective to qualitatively explore how youth perceived the videos’ effects to identify the mechanisms of the intervention that affected how adolescents experienced stress.

Methods

It should be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic led to inevitable changes in the pre-registered protocol (https://osf.io/u4cmf). Specifically, the original version of this study included measures of cortisol and testing in classroom settings to examine the potential effect of the intervention on the intensity of adolescents’ physiological stress responses and their performance on an end-of-year examination. The Research Ethics Board of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de l’Est de l’Île de Montréal approved this study on March 10th, 2020. However, on March 13th, Canada declared a public health emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, as high schools were closed and all examinations were canceled, we abandoned our objective to assess adolescents’ performance during their end-of-year exams, were forced to replace cortisol measures with a perceived stress measure, and adapted the in-class study protocol to an online design. Amendments to the original protocol were approved on March 24th and April 17th, 2020 [certificate numbers FWA00001935 et IRB00002087], and testing occured from March 24th to June 8th, 2020. No other deviations were made.

Sampling and participants

Sample

A total of 918 high school French-speaking students (aged 14–17) from 126 cities in Quebec (Canada) were recruited using two voluntary response sampling strategies: via email as former research participants (Journault et al., Citation2022) or advertisements through their schools. Adolescents received an online poster inviting them to participate in an online study that “aimed to help them tame their stress” by watching videos. As such, the participant’s knowledge of the study’s purpose during recruitment typically induced an expectancy effect bias where youths expected that the videos would help them with their stress (Klein et al., Citation2012). The poster included a direct link to the consent form and thereafter, the study began with a pre-intervention questionnaire. In total, 463 adolescents completed the pre-intervention questionnaire and were blindly assigned to the intervention or control condition via Qualtrics’ computerized randomization. Five participants were excluded from the study as they were assigned to both conditions erroneously due to a technical computerized randomization issue. To avoid unnecessary delays between the pre-intervention questionnaire and beginning of the intervention, we used four data collection waves to launch the intervention (start dates in 2020: April 14th, April 28th, May 5th, and May 12th). A total of 458 adolescents received the launched intervention, of which 233 adolescents completed the entire protocol and were included in our analyses (i.e., 207 participants partially completed the conditions and 18 were lost to the completion of the post-test measures; attrition rate of 53% see for sample demographics). To assess the potential effects of this attrition, preliminary one-way ANOVAs were performed on all demographic data (i.e., age, sex, perceived SES, school type, racial and ethnic identity, and if they engaged in learning/academic activities or underwent evaluations at the time of testing) and pre-registered measures at pre-intervention. Results revealed that participants who completed the entire protocol did not significantly differ from those who dropped out before the end protocol, with one expection. Specifically, those who dropped out reported slightly less trait anxiety than those retained (F(1,793) = 8.45, p = .004, η2p = .009). Further, missing values for stress mindsets, perceived stress, and anxiety sensitivity were below 1% and likely due to random items skipped during scale completion. Adolescents received no compensation, but all participants gained access to the intervention at the end of testing.

Table 1. Sample demographics by conditions.

A power analysis revealed that a minimum of 100 participants was required per condition (N = 200) to meet the research objective. This analysis was conducted using Gpower with a type I error of 5% (α = .05), a target power level of 80%, and capability to detect an effect that explains 20% of the total variance (η2 = .20) based on the effects found by Crum et al. (Citation2013). Given the online design and the effects of the pandemic on youth routines, we aimed to recruit 800 adolescents to account for a high attrition rate.

Measures

A demographic questionnaire assessed youth age, sex (boy, girl, other), perceived SES (“How comfortable do you think your family is financially?”), school type, racial and ethnic identity, and if they had learning/academic activities or evaluations during the testing period.

Psychological assessments

We measured adolescents’ stress mindsets using the Stress Mindset Measure-General (SMM-G; Crum et al., Citation2013). This 8-item questionnaire evaluates whether an individual holds stress-can-be-enhancing (e.g., “Experiencing stress improves my health and vitality”) or stress-is-debilitating mindsets (e.g., “The effects of stress are negative and should be avoided”). Participants indicated how much they agreed with each item on a scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The overall score was calculated from the average of the eight items ranging from 0 to 4, where a score above 2 indicated a stress-can-be-enhancing mindset. The validation study found a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 (Crum et al., Citation2013). The French version we created using a double/back translation technique (Kristjansson et al., Citation2003) showed alphas of .83 and .88 at pre- and post-intervention, respectively.

Perceived stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale for Children (PSS-C; White, Citation2014). This 13-item questionnaire measures the frequency of stressful thoughts or feelings during the last week. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “often”. The total score was derived by summing all items after recodes, and therefore ranged from 0-39, with high scores indicating greater perceived stress in the last week. The scale has been validated in individuals ages 5–18 years old, although the authors report no reliability coefficient. The double-translated French version produced acceptable (Ursachi et al., Citation2015) Cronbach’s alphas of .67 and .71 at pre- and post-intervention, respectively. The factor structure of the translated measures used is found in the supplemental material.

We measured anxiety sensitivity using the French version of the self-report Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index (CASI; Stassart & Etienne, Citation2014). The questionnaire consists of 18 items rated on a 3-point Likert scale (1 being “not at all”, 2 “a little”, and 3 “a lot”). Items are summed to produce a total score that may vary between 18 and 54, where a higher score reflects a higher sensitivity. The French version of the scale has demonstrated a reliability coefficient of .82 (Stassart & Etienne, Citation2014). The Cronbach’s alphas in our sample were .83 and .86 at pre- and post-intervention, respectively.

Protocol

This study used an online experimental design (see ) to assess whether exposure to the intervention effectively modified stress mindsets and thus, reduced perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity in adolescents. Via email, adolescents received a video capsule of the intervention or control condition twice a week (on Tuesday and Thursday) over two consecutive weeks. To engage participants with the content of the videos, after each video, the adolescents were invited to complete a short online logbook entry to indicate if and how they intended to apply the content of the videos in their daily lives. Stress mindsets, perceived stress, and anxiety sensitivity were assessed pre-and post-intervention.

Intervention and control conditions

Intervention condition: The Stress N’ Go wise intervention consists of four video capsules (5 mins. each) designed for a youth audience (i.e., animations, humorous tone, bright colors, rhythmic music). The intervention combines the stress mindset/stress reappraisal material of the Yeager et al. (Citation2022) synergetic intervention and the stress-regulating strategies material of Lupien et al. (Citation2013; as seen in the bottom part of (B)). The material teaches youth about (1) how to recognize the physiological stress response and its causes, (2) both positive and negative consequences of a stress response, (3) the necessity of the stress response in overcoming pitfalls, (4) how to reappraise negative stress mindsets, (5) the possibility of taking advantage of the stress response during specific stressful situations (e.g., exams), and (6) the use of strategies to deal with a stress response to maintain it at an optimal level.

Control Condition: Destination: Brain consists of four video capsules (5 mins. each). The videos were inspired by the Anonymized program developed by the Centre for Studies on Human Stress (CSHS) which summarizes brain structure and function without addressing stress. Rather than using a control group that was not exposed to a particular condition, the control condition allowed US to determine whether changes in our observed variables were attributable to our intervention or to environmental factors (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic). French and English versions of the videos used in both conditions can be found at: https://humanstress.ca/programs/stress-n-go/.

Implementation assessment

Before testing our intervention, we evaluated how the intervention was put into practice as recommended by Lendrum & Humphrey (Citation2012). To do so, several indicators of the online implementation of both conditions were used, including compliance indicators and a quiz to verify whether participants were paying attention and understood the content of the videos. The results of these indicators of implementation assessment are described in supplementary materials, but overall reveal good compliance in both conditions as well as an adequate level of understanding and appreciation of the intervention material. In addition, to perform an in-depth exploration of the participants’ views of how they experienced the intervention, we asked them whether the videos helped them live better with their stress at post-intervention. Participants who answered “yes” were then invited to answer briefly to the following open-ended question: “How do the videos help you live better with your stress?”

Data analyses

Preliminary descriptive analyses

Values of skewness and kurtosis ranged from −1 to +1 for all variables, ensuring normal univariate distribution of the data (Kim, Citation2013). To ensure that group randomization had not induced group imbalances on demographic variables, we performed descriptive analyses on the participants who completed the pre-intervention questionnaire (N = 458). A t-test and Chi-Square tests were used to compare groups on age, sex, racial and ethnic identity, self-reported SES, and their respective data collection wave. We adjusted the main analyses for effects of these potential confounds when results revealed significant differences between conditions.

Pre-registered data analysis plan

We evaluated the effects of the intervention on stress mindsets, perceived stress, and anxiety sensitivity using 2 × 2 mixed ANOVAs in SPSS v.26. The between-subjects variable was condition (intervention versus control), and the within-subjects variable was time (pre-intervention versus post-intervention). As we tested the effect of conditions on many dependent variables, time, and their interactions, a false-discovery rate adjustment was applied to the p-values (Jafari & Axnsari-Pour, Citation2019). Effect sizes were estimated with partial eta squared (η2p), where .01, .06, and .13 correspond to small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation1969, as in Richardson, Citation2011). Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) estimates of Bayes Factors (Jarosz & Wiley, Citation2014) allowed us to determine evidential values of all null results, and to rule out the possibility that they were due to a lack of power (Aczel et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Dienes, Citation2016).

Exploratory analyses

To understand individual differences in response to the intervention and explore the heterogeneity of its effects, sensitivity analyses were performed. As the intervention may have more so affected measured outcomes for participants who had negative stress mindsets at baseline, we tested whether baseline stress mindsets moderated the effect of the intervention on these outcomes. To this end, we first computed participants’ stress mindset global scores using a dummy variable that divided participants into subgroups based on their stress mindset score at baseline (SMM-G < 2 = negative stress mindsets; SMM-G 2 = positive stress mindsets). We performed a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA to compare stress mindsets, perceived stress, and anxiety sensitivity levels at post-intervention between subgroups (i.e., negative versus positive stress mindsets at baseline) and condition (i.e., intervention versus control).Footnote1

Finally, to refine the quantitative results of this study, we conducted a non-pre-registered qualitative thematic analysis to obtain an in-depth exploration of how adolescents experienced the intervention. To conduct this analysis, the corpus of logbook text entries was first read through several times by the first author to identify emerging themes and to associate them with a code. Then, the third author and a research assistant uninvolved in the research project analyzed the corpus to code the remaining text entries according to the themes. Codes were attributed non-exclusively (i.e., a text entry could receive several codes when two or more themes were mentioned). A very high inter-coder agreement was obtained (91.25%; McHugh, Citation2012) and the coders resolved all disagreements via discussions.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Results of the t-test and chi-square analyses revealed no demographic differences between conditions at baseline (see ). Thus, no covariates were included in the main analyses. presents correlations and the descriptive statistics for all scales.

Table 2. Potential covariates.

Table 3. Mean, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations at pre- and post-intervention.

Main analyses

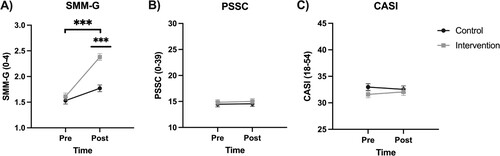

Effect of the intervention on stress mindsets

Results from the mixed ANOVA showed a significant Time*Condition interaction effect on stress mindset with a large effect size (F(1,229) = 44.81, p < .001,η2p = .16; (A)). This indicates that the changes in stress mindsets across time differed between conditions. We found no significant differences between conditions at pre-intervention (F(1,229) = 0.69, p = .406). However, the intervention group had significantly more stress-can-be-enhancing mindsets at post-intervention compared to the control group (F(1,229) = 43.34, p < .001, η2p = .16). These results show that the improvement in stress mindsets was greater following the Stress N’ Go intervention than the control condition.

Effect of the intervention on perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity

Results from the mixed ANOVA showed a non-significant Time*Condition interaction effect on perceived stress (F(1,229) = 0.02, p = .899; (B)) and anxiety sensitivity levels (F(1,230) = 2.24, p = .136, (C)). This shows that neither condition nor time impacted participants’ perceived stress or anxiety sensitivity levels. To better understand the null effects of the intervention these outcomes, we measured their evidential values using Bayes factors (BF01 – evidence in favor of the null hypothesis (no effect of the intervention in time) vs. the alternative hypothesis (effect of the intervention in time)). As suggested by Jarosz & Wiley (Citation2014), we used the BIC of the null and alternative models. The obtained Bayes factors were 31.50 and 16.44 for perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity, respectively. According to the Bayes factors interpretation table proposed by Jeffreys (Jarosz & Wiley, Citation2014), this provides strong evidence in favor of H0, suggesting that there was no main effect of the intervention on perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity levels and that these null findings were not due to insufficient statistical power.

Exploratory analyses – moderation effects

While evidential values suggest that the intervention did not affect perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity levels of adolescents, we conducted additional exploratory sensitivity analyses to explore the heterogeneity in response to the intervention.

First, the results of the mixed ANOVAs exploring the moderation effect of stress mindsets at baseline showed a significant Condition*Stressmindsets_baseline interaction effect on stress mindsets at post-intervention (F(1,220) = 4.39, p = .037, η2p = .02). This indicates that the stress mindsets at post-intervention varied significantly between conditions depending on participants’ stress mindsets levels at baseline. For participants who had a positive stress mindset at baseline, we found only a small difference in stress mindsets at post-intervention (F(1,227) = 5.49, p = .020, η2p = .02), whereas this difference was large for participants who had a negative stress mindset at baseline (F(1,227) = 59.03, p < .001, η2p = .21). These results show that participants with a negative stress mindset at baseline reported a greater change in stress mindset across time compared to those with a positive stress mindset at baseline. Second, the Condition*Stressmindsets_baseline interaction effect on perceived stress (F(1,220) = 0, p = .508) and anxiety sensitivity (F(1,220) = 0.34, p = .559) were not significant. This shows that the main effect of the intervention on perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity was non-significant despite the adolescents’ stress mindsets at baseline.

Exploratory non-pre-registered analyses – qualitative data

Of the 119 intervention group participants who answered the open-ended question post-intervention, 88 youth (75%) stated that the intervention helped them live better with their stress. A thematic analysis of the logbook text entries revealed the emergence of four themes regarding the interventions’ mechanisms that helped them to live better with their stress. The following entries were translated from French to English by RC, a native English-speaker.

Having a better understanding of the stress response: A little less than half of the participants (38%) reported that the intervention helped them understand that stress has a function, which helped them understand why they experience it daily. Some participants also mentioned that the videos helped them understand the causes of their stress, how the stress response works, and what manifestations are associated with it.Before I didn’t really understand why we were stressed and what it was for. But now, in situations that I experienced a few days ago, I’ve already been able to manage my stress a few times. – Girl, 15 y/oI think that knowing more about stress and having taken the time to better recognize my stress signals is helping me to cope better with stress. – Girl, 16 y/o

Knowing how to regulate a stress response: Half of the participants (50%) wrote that the intervention helped them to learn how to regulate or control their stress responses – whether it was due to knowing how to not let their stress responses overwhelm them or by learning new strategies to regulate their stress responses.The videos helped me discover many tricks to manage my stress. – Girl, 17 y/oThanks to them, the next time I have an exam, I’ll be able to control it. – Girl, 14 y/o

Accepting a stress response as enhancing: A little less than half of the participants (38%) reported that the intervention brought out a stress-can-be-enhancing mindset in them. The intervention helped to normalize stress, which helped them to appraise it more positively when they had a stress response and to accept it. Viewing the video capsules helped participants to understand that they can use stress to their advantage and that it is not always bad.They […] taught me that stress is a good thing. We can use it as an asset and not just as a negative thing in our life. It can especially help us move towards the unknown or towards a challenge to overcome. – Girl, 15 y/oI accept it more. I’m stressed but I tell myself it’s okay, it’s there to help me. – Boy, 16 y/oI also realize that I am not alone, that stress is a normal part of life. – Boy, 16 y/o

Feeling reassured in the face of a stress response: Few participants (7%) said that the intervention allowed them to feel reassured, to be less afraid of stress, or to be at peace with the idea of experiencing it.I am able to think more calmly and not get carried away by it. – Girl, 14 y/oI better understand why I feel stress at times and so, it seems to scare me less. – Girl, 16 y/o

Compared to the intervention group, out of the 114 control participants who answered the open-ended question post-intervention, only 46 youth (40%) reported that the intervention helped them live better with their stress. Moreover, their logbook text entries showed a different pattern of mechanisms. A similar proportion of participants’ responses corresponded to Theme 1, whereas fewer responses corresponded to Theme 2 and 3 than the intervention group. While these similarities aligned with the participants’ expectation bias instilled by recruitment, control group participants did not mention Theme 4 and a new theme emerged for most of them (i.e., the control condition helped by teaching them how the brain works).

Discussion

This study evaluated whether a wise intervention targeting stress mindsets/appraisals and stress-regulation strategies could not only reduce negative stress mindsets but also alter perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity among youth. Results showed that compared to a control condition, the intervention rapidly improved adolescents’ stress mindsets. However, modifying mindsets did not alter youth’s perceived stress or anxiety sensitivity. Important scientific and educational implications are discussed below.

As expected, compared to a control condition, the intervention effectively improved stress mindsets in youth towards a more positive stress mindset, particularly in those who had stress-is-debilitating mindsets at baseline. This result is interesting as it suggests that despite an overall positive effect of the intervention on adolescents’ stress mindsets, this effect was amplified for those who are most likely to benefit from the intervention. In doing so, the intervention has the potential to reduce the gap in mindsets between the adolescents who are equipped to take advantage of their stress responses (i.e., already having positive stress mindsets at baseline) and those who are not. Globally, exposure to our wise intervention explained a large, 16.4% of the variance in stress mindsets. The magnitude of the change in stress mindsets that we found (+0.82 on a 4-point scale) is four times greater than that found by Crum et al. (Citation2013; + 0.20 on a 4-point scale), where adult participants were passively exposed to a video presenting the enhancing effects of stress. Various parameters could explain the larger effect found with our intervention. First, combining different types of knowledge about stress (i.e., stress mindsets/stress reappraisal, and stress-regulation strategies) could have had additive effects on stress mindsets. A more active engagement of the audience (i.e., using logbooks) could also explain this larger effect, as well as the age of the audience (i.e., adolescents). Overall, these findings suggest that the Stress N’ Go intervention is an effective, free, and rapid tool to modify stress mindsets among adolescents, particularly among those with negative stress mindsets.

However, the change in stress mindsets did not extend to perceived stress or anxiety sensitivity, regardless of adolescents’ stress mindsets at baseline. Importantly, according to Bayes factors, these null effects could not be explained by a lack of statistical power. This suggests that manipulating adolescents’ negative beliefs surrounding stress through wise interventions has a specific effect on stress mindsets but does not modify perceived stress or anxiety sensitivity. These findings highlight the complexity of how adolescents experience stress, such that our intervention alone was insufficient to modify perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity across all participants during a pandemic.

First, the fact that the intervention did not modify adolescents’ perceived stress levels is not a negative finding per se, as lower stress levels are not necessarily more adaptive and can be impairing (Baldi & Bucherelli, Citation2005). Indeed, rather than seeking to eliminate or lower stress responses, our wise intervention taught participants how to embrace their stress responses (i.e., by optimizing them) and use them as a resource to overcome challenges. Further, as subjective and physiological stress measures are not consistently associated (Lupien et al., Citation2022), our intervention may create a more adaptive physiological stress response, despite its null effect on subjective stress measures. In fact, studies on youth have shown that improving stress mindsets and appraisals results in a more adaptive physiological stress response (Yeager et al., Citation2016, Citation2022; Crum et al., Citation2013, Jamieson et al., Citation2010).

Second, although stress-is-debilitating mindsets and anxiety sensitivity both arise from negative beliefs surrounding stress, our results suggest that improving mindset was insufficient to challenge an adolescent’s tendency to fear physiological stress responses (i.e., anxiety sensitivity). Three explanations can be proposed to interpret this result: (1) anxiety sensitivity is a stable tendency that requires more intense or long-term interventions to be modified (as opposed to rapid wise interventions), (2) the effects of the intervention were heterogenous and (3) the unique COVID-19 context in which the testing occurred (in which schools were temporarily closed) limited the scope of the intervention to stress mindsets.

To begin, while many cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) studies for the treatment of anxiety have shown that modifying cognitive appraisals effectively diminishes an individual’s anxious emotions (for a review, see Clark & Beck, Citation2010), the intervention tested in this study was a wise, low-intensity, and universal intervention. Thus, it is possible that Stress N’ Go was sufficient to modify the flexible meta-cognitive control of emotions (i.e., stress mindsets) but insufficient to produce a change in a more stable cognitive tendency towards biased attitudes regarding the experience of physiological stress responses in adolescents. The latter inability contrasts with the end results of intensified CBT. As such, stress responses could still activate these negative attitudes (or vice versa), where cognitive control would be insufficient to inhibit the negative emotions and behaviors (i.e., anxiety sensitivity). This interpretation is also supported by the fact that few adolescents qualitatively reported that the intervention helped them to feel reassured when faced with a stress response.

Second, the effect of the intervention on adolescents’ anxiety sensitivity may be heterogenous and moderated by factors that were not measured in this study (aside from stress mindsets at baseline). For instance, an important factor could be psychological affordances. Some authors argued that the effect of interventions depend on the context in which they are delivered (Bryan et al., Citation2021). As such, to foster the adequate growth of new mindsets, the social context in which the intervention is administered must afford this way of thinking (Walton & Yeager, Citation2020). Although our intervention successfully induced stress-can-be-enhancing mindsets, certain familial environments within the context of a worldwide pandemic may have promoted the opposite. Consequently, this may have interfered with the effects of this new mindset for these individuals and could explain our null findings.

Third, our wise intervention may have impacted adolescents’ anxiety sensitivity if it had been administered in an ecological context allowing them to test whether the stress-can-be-enhancing mindset truly helps them with their stress. Indeed, schools are a place in which the majority of performance-motivated contexts and sources of stress in a youth’s life occur (Byrne et al., Citation2007) and exposure to fear is another important aspect of CBT that reduces anxious emotions (Fréchette-Simard et al., Citation2018), as it allows for the “repeated evaluation of one’s reaction to events” (Clark & Beck, Citation2010, p. 40). Unfortunately, school closures at the time of testing may have deprived adolescents of most in-person opportunities to put the new knowledge from our intervention immediately into practice.

Beyond the null effect of the intervention on perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity, we did observe an effect of the intervention on the participants’ experience as examined through qualitative analyses. Most adolescents reported that the intervention helped them to live better with their stress and more than half reported that it did so by explaining how to manage a stress response. Taken alongside our quantitative data, the qualitative data suggests two interesting possibilities. First, if modifying stress-is-debilitating mindsets did not have a statistical effect on adolescents’ anxiety sensitivity in this study, our intervention may have planted a seed in the minds of adolescents. In turn, this could later facilitate their search for professional, more intensified, and personalized help. Second, adding stress-regulation strategies to the stress mindsets/appraisals material in this wise intervention was a key component of the adolescents’ stress experience. Even though adolescents could now recognize their stress responses as a tool, they continued to perceive that having control over the intensity of a stress response was necessary. Consequently, although it was not measured in our study, it may be that adolescents might have engaged in difficult challenges and used these strategies to overcome them during the following months.

Limitations and future directions

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, validation of the stress mindset measure French translation would strengthen the results. Second, although the pandemic demanded an online design, it led to high attrition rates between the launch of the intervention and post-intervention measures (53%). Adolescents who completed the entire protocol had greater anxious personalities than dropouts. Thus, we believe that most of the attrition was either due to a selection bias originating from the recruitment method or to the communication vehicle (i.e., emails) used by our team to send the videos and link to complete the post-intervention questionnaire. The emails may have been directed to junk mailboxes and/or adolescents may have missed our communications or become aware of them when it was too late if they infrequently checked their emails. Second, the online design affected the generalizability of the sample. Using the study’s initial in-person classroom design, where most students participate in studies conducted during school periods, would have ensured greater generalizability. Although our sample represented participants from various cities across Quebec (Canada), our results are mainly representative of the effectiveness of Stress N’ Go in a White population of anxious adolescent girls from moderate to high SES families.

Nonetheless, by evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention in modifying adolescent stress mindsets, this study provides a new tool to help youth benefit from their stress. The double-blind experimental design using both intervention and control conditions strengthened our results. It allowed us to demonstrate that the observed change in stress mindsets was attributable solely to the Stress N’ Go intervention, despite the stressful nature of the pandemic and expectancy effect induced by the recruitment strategy. To better capture the extent of the effects of the Stress N’ Go intervention, future studies should explore its optimizing potential on the stress response by combining physiological and subjective stress measures. Although we failed to find that youth baseline perceived stress levels moderated the effects of our intervention, Keech et al., (Citation2021) showed that the effects of wise interventions on stress mindsets can vary according to youth stress exposure levels. Thus, future studies should consider this potential moderating factor as individual stress exposure varies greatly in ecological versus laboratory settings, where the latter involves exposure to a controlled and single experimental acute stressor. Furthermore, studies in a normal school context that consider heterogeneity and psychological affordances are necessary to rule out the possibility that the unique COVID-19 context in which the testing occurred limited the scope of the intervention, and whether modifying stress mindsets/appraisals is sufficient to alter anxiety sensitivity in youth. Additionnally, comparing the effects of the two different mechanisms of this intervention (stress mindsets/appraisals or stress regulation strategies) on adolescents’ experience of stress using a factorial design could guide the interventions. Finally, future studies should also explore other potential outcomes of the intervention in the long term, such as seeking challenges and using stress-regulation strategies, alongside other factors underlying the heterogeneity of mindset interventions, such as age.

Conclusions

In conclusion, given that youth inevitably experience stress when overcoming the challenges of adolescence, it is essential to go beyond the general message conveyed that “stress is bad” and to teach them the utility of stress responses. Although results from this study revealed that our wise intervention was insufficient to reduce perceived stress and anxiety sensitivity in most youth of our sample, they suggest that it is a promising tool to help adolescents change the negative pair of glasses through which they see stress in their daily lives. Furthermore, our participants perceived that the addition of stress-regulation strategies to the intervention was an important aspect that helped them live with their stress. In contrast to other interventions, Stress N’ Go is free and does not require trained staff as it can be self-administered by adolescents or administered to groups of students. The flexibility and efficacy of Stress N’ Go thereby ensures easy accessibility to all youth seeking to benefit from their stress response.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank the adolescents who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Anonymized data and syntax are available at https://osf.io/cr8xt/

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Recent work showing that only participants with high perceived stress levels at baseline benefit from mindset interventions (Keech et al., Citation2021) was published after our testing. Additional non-preregistered analyses were thus conducted to explore whether perceived stress at baseline moderated the effects of our intervention. As results were not significant, they are not reported in this paper.

References

- Aczel, B., Palfi, B., & Szaszi, B. (2017). Estimating the evidential value of significant results in psychological science. PLOS ONE, 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182651

- Aczel, B., Palfi, B., Szollosi, A., Kovacs, M., Szaszi, B., Szecsi, P., Zrubka, M., Gronau, Q. F., van den Bergh, D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2018). Quantifying support for the null hypothesis in psychology: An empirical investigation. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(3), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918773742

- Baldi, E., & Bucherelli, C. (2005). The inverted “U-shaped” dose-effect relationships in learning and memory: Modulation of arousal and consolidation. Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology, Medicine, 3(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.2201/nonlin.003.01.002

- Bryan, C. J., Tipton, E., & Yeager, D. S. (2021). Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01143-3

- Byrne, D. G., Davenport, S. C., & Mazanov, J. (2007). Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). Journal of Adolescence, 30(3), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.004

- Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 270–295. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1094

- Chaby, L. E., Sheriff, M. J., Hirrlinger, A. M., & Braithwaite, V. A. (2015). Can we understand how developmental stress enhances performance under future threat with the yerkes-dodson law? Communicative & Integrative Biology, 8(3), e1029689. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2015.1029689

- Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2010). Cognitive theory and therapy of anxiety and depression: Convergence with neurobiological findings. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(9), 418–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.06.007

- Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press.

- Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Martin, A., & Fath, S. (2017). The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(4), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1275585

- Crum, A. J., Jamieson, J. P., & Akinola, M. (2020). Optimizing stress: An integrated intervention for regulating stress responses. Emotion, 20(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000670

- Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031201

- Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., & Suleiman, A. B. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554(7693), Article 441. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25770

- Dienes, Z. (2016). Commentary: How Bayes factors change scientific practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 7), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01504

- Dienstbier, R. A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.1.84

- Fréchette-Simard, C., Plante, I., & Bluteau, J. (2018). Strategies included in cognitive behavioral therapy programs to treat internalized disorders: A systematic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(4), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1388275

- Jafari, M., & Ansari-Pour, N. (2019). Why, when and How to adjust your P values? Cell Journal (Yakhteh), 20(4), 604–607. https://doi.org/10.22074/cellj.2019.5992

- Jamieson, J. P. (2017). Challenge and threat appraisals. In A. J. Elliot, D. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 175–191). The Guilford Press.

- Jamieson, J. P., Crum, A. J., Goyer, J. P., Marotta, M. E., & Akinola, M. (2018). Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: An integrated model. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1442615

- Jamieson, J. P., Hangen, E. J., Lee, H. Y., & Yeager, D. S. (2018). Capitalizing on appraisal processes to improve affective responses to social stress. Emotion Review : Journal of the International Society for Research on Emotion, 10(1), 30–39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6550483/.

- Jamieson, J. P., Mendes, W. B., Blackstock, E., & Schmader, T. (2010). Turning the knots in your stomach into bows: Reappraising arousal improves performance on the GRE. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.015

- Jamieson, J. P., Mendes, W. B., & Nock, M. K. (2013). Improving acute stress responses. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412461500

- Jarosz, A. F., & Wiley, J. (2014). What Are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting Bayes factors. The Journal of Problem Solving, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.7771/1932-6246.1167

- Journault, A.-A., Plante, I., Charbonneau, S., Sauvageau, C., Longpré, C., Giguère, C-É, Labonté, C., Roger, K., Cernik, R., Chaffee, K. E., Dumont, L., Labelle, R., & Lupien, S. (2022). Using latent profile analysis to uncover the combined role of anxiety sensitivity and test anxiety in students’ state anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035494

- Keech, J. J., Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2021). Changing stress mindsets with a novel imagery intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Emotion, 21(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000678

- Keech, J. J., Hagger, M. S., O’Callaghan, F. V., & Hamilton, K. (2018). The influence of university students’ stress mindsets on health and performance outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(12), 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay008

- Kilby, C. J., & Sherman, K. A. (2016). Delineating the relationship between stress mindset and primary appraisals: Preliminary findings. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1937-7

- Kim, H.-Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52

- Klein, O., Doyen, S., Leys, C., Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama, P. A., Miller, S., Questienne, L., & Cleeremans, A. (2012). Low hopes, high expectations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612463704

- Kristjansson, E. A., Desrochers, A., & Zumbo, B. (2003). Translating and Adapting Measurement Instruments for Cross-Linguistic and Cross-Cultural Research:A Guide for Practitioners. 35(2), 16.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2012). The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education, 38(5), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.734800

- Liu, J. J. W., & Vickers, K. (2015). New developments in stress research-Is stress all that bad? New evidence for mind over matter. In A. M. Columbus (Eds.), Advances in psychology research (Vol. 106). Nova Publisher.

- Lupien, S. J., Leclaire, S., Majeur, D., Raymond, C., Jean Baptiste, F., & Giguère, C.-E. (2022). ‘Doctor, I am so stressed out!’ A descriptive study of biological, psychological, and socioemotional markers of stress in individuals who self-identify as being ‘very stressed out’ or ‘zen’. Neurobiology of Stress, 18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2022.100454

- Lupien, S. J., & McEwen, B. S. (1997). The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: Integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Research Reviews, 24(1), 1–27. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00004-0

- Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2639

- Lupien, S. J., Ouellet-Morin, I., Trépanier, L., Juster, R. P., Marin, M. F., Francois, N., Sindi, S., Wan, N., Findlay, H., Durand, N., Cooper, L., Schramek, T., Andrews, J., Corbo, V., Dedovic, K., Lai, B., & Plusquellec, P. (2013). The DeStress for success program: Effects of a stress education program on cortisol levels and depressive symptomatology in adolescents making the transition to high school. Neuroscience, 249, 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.057

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900052/.

- McLaughlin, E. N., Stewart, S. H., & Taylor, S. (2007). Childhood anxiety sensitivity index factors predict unique variance in DSM-IV anxiety disorder symptoms. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701499988

- McNally, R. J. (1990). Psychological approaches to panic disorder: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 403. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.403

- Pope, D. C. (2003). Doing school: How We Are creating a generation of stressed-Out, materialistic, and miseducated students. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/9780300098334/doing-school.

- Reiss, S., Peterson, R. A., Gursky, D. M., & McNally, R. J. (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9

- Richardson, J. T. E. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.12.001

- Romeo, R. D. (2013). The teenage brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413475445

- Schmidt, N. B., Keough, M. E., Mitchell, M. A., Reynolds, E. K., MacPherson, L., Zvolensky, M. J., & Lejuez, C. W. (2010). Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of anxiety among early adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(5), 503–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.007

- Selye, H. (1976). Stress without distress. In G. Serban (Ed.), Psychopathology of human adaptation (pp. 137–146). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2238-2_9

- Stassart, C., & Etienne, M. (2014). A French translation of the childhood anxiety sensitivity index (CASI): Factor structure, reliability and validity of this scale in a nonclinical sample of children. Psychologica Belgica, 54(2), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.an

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

- Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000115

- Walton, G. M., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). Seed and soil: Psychological affordances in contexts help to explain where wise interventions succeed or fail. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420904453

- Watt, M. C., & Stewart, S. H. (2009). What you should know about anxiety sensitivity. Strides.

- Wearne, T. A., Lucien, A., Trimmer, E. M., Logan, J. A., Rushby, J., Wilson, E., Filipčíková, M., & McDonald, S. (2019). Anxiety sensitivity moderates the subjective experience but not the physiological response to psychosocial stress. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 141, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.04.012

- White, B. P. (2014). The perceived stress scale for children: A pilot study in a sample of 153 children. International Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 2(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.12974/2311-8687.2014.02.02.4

- Yeager, D. S., Bryan, C. J., Gross, J. J., Murray, J. S., Krettek Cobb, D., Santos, H. F., Gravelding, P., Johnson, H., Jamieson, M., & P, J. (2022). A synergistic mindsets intervention protects adolescents from stress. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04907-7

- Yeager, D. S., Lee, H. Y., & Jamieson, J. P. (2016). How to improve adolescent stress responses: Insights from integrating implicit theories of personality and biopsychosocial models. Psychological Science, 27(8), 1078–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616649604