ABSTRACT

The lockdowns that began during the spring of 2020 changed the conditions for teaching and assessment across the globe. In Norway, schools were closed, and all school activities took place online. Moreover, all final exams were canceled, and all student grading was based on final grading by the individual teacher. Because of this, teachers’ assessment skills became more important. This study examines students’ and teachers’ experiences of assessment during the lockdown period. The findings revealed that students got little support from the teacher in their learning process; they worked alone and felt insecure about assessment. Teacher collaboration about assessment seemed sporadic and the assessment routines were weak. The study raises concerns about equity in education when teachers have problems implementing assessment practices that support students’ learning.

Introduction

Having the opportunity to go to school and get an education is a human right, defined by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) points out that fair and inclusive education is desirable to develop their capacities and to participate fully in society (OECD, Citation2021). However, school closures during the pandemic have provided a stark reminder that we do not all start out with the same resources and opportunities, and that the consequences of this persist throughout our lives. In Norway, the conditions for education are well regulated by law: “School shall ensure that human dignity and the values supporting this are the foundation for the education and training and all activities.” (Ministry of Education, Citation2018). The practice of public schools is shaped by national legislation and curricula that largely homogenize the schools all over the country. The ideal of social equity in Norway takes the form of the unitary school, determined by an overarching structural framework that shapes teachers’ views on teaching and learning.

Yet in this “one school for all” ideal system students are ultimately assessed and sorted by performance, which raises the question of how this assessment can be reconciled with the notion of equity. In response, for the last decade, national authorities have through laws and national programmes promoted Assessment for Learning (AfL), i.e. that assessment should be used to strengthen students’ rights and their involvement in own learning and to adapt teaching to every student’s needs (Regulations of the Education Act, Citation2020). However, national student surveys and research show that there are large variations in Norwegian schools in how successful the AfL implementation has been to ensure student involvement and equity in assessment (Hopfenbeck, Flórez Petour, & Tolo, Citation2015; Sandvik, Citation2019; Wendelborg, Dahl, & Buland, Citation2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, students had to take on greater responsibility for educating themselves remotely, which has placed great demands on students’ abilities to self-regulate their learning. The COVID-19 school situation has lasted for roughly two years nationwide. Home-schooling for longer periods from March 2020 until the spring of 2022 required students to adjust to learning from home with the available resources and with limited contact with classmates and teachers, and teachers had to set up online instruction using the resources at hand. Moreover, national authorities decided to cancel exams in 2020, 2021 and 2022. Initial reports have revealed that these circumstances affected the teaching and assessment practice and had a great impact on students’ experiences regarding the quality of learning and assessment (Sandvik et al., Citation2021), and on students’ social isolation and on their well-being (Letzel, Pozas, & Schneider, Citation2020); additionally it has been shown to impact teachers’ ability to adapt their instructional methods within a digital environment, as well as increasing the demands placed on teachers and consequently raising their workload (Flack, Walker, Bickerstaff, Earle, & Margetts, Citation2020).

Because the exams were canceled, teachers’ assessment skills became more important. In particular, the pandemic created challenges for teachers in designing assessment tasks during distance learning. Even though the Assessment for Learning (AfL) discourse has been dominant in Norwegian schools for the last ten years, as in the rest of the world, studies show that there is limited implementation of AfL in many Norwegian schools (Sandvik, Citation2019). International studies related to AfL have also revealed challenges regarding teachers’ knowledge, skills, and practices and how these aspects affect implementation (DeLuca, Chapman-Chin, LaPointe-McEwan, & Klinger, Citation2018). Furthermore, studies have found that students may not experience AfL practices as intended by the teacher (Cowie, Citation2009; Havnes, Smith, Dysthe, & Ludvigsen, Citation2012; Jónsson, Smith, & Geirsdóttir, Citation2018; Klenowski, Citation2009). Hence, it is important to understand students’ perspectives toward this pedagogical approach in circumstances that require a high level of assessment literacy from both students and teachers. Insufficient assessment literacy could therefore threaten the quality of the learning processes.

Mind-Sets and practices were challenged in a completely new manner. In a previous study investigating how Norwegian upper secondary school students perceived teaching and assessment practices during the COVID-19 lockdown (Sandvik et al., Citation2021), it was evident that students had notably varied experiences with teaching and assessment during distance learning. It was particularly challenging that many teachers had not coordinated the activities and assessment tasks, either within the different subjects or at the school level, such that the whole situation was experienced as chaotic and demanding for the students, which affected students’ motivation (Sandvik et al., Citation2021).

However, students who already had high levels of mastery managed to self-regulate their own learning and to create their own structures and routines for learning (Sandvik et al., Citation2021). Several students reported that they even learned better and got better grades. These findings are also confirmed by another COVID-19 study in the Norwegian context (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020). Conversely, students who did not master remote learning and felt that it was stressful and threatening found that they did not learn much during this period. Being motivated, self-efficient, and able to manage stress are the characteristics of successful learners (Davis, Solberg, de Baca, & Gore, Citation2014), and routines, structures, and relevant feedback from teachers are elements that support the effective learning experiences of students.

When new and unforeseen challenges occur, such as school closures during COVID-19, students’ levels of motivation and mastery depend heavily on their teachers (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020; Huber & Helm, Citation2020; Sandvik et al., Citation2021). During this time, elements that are crucial for student learning have been challenged, such as student involvement, self-regulation, and collaboration between students and teachers. The present study examines how upper secondary school students and teachers perceived assessment practices during COVID-19 home-schooling. The research questions that we seek to answer are the following:

How did teachers experience the teaching and assessment practices?

How did home-schooling affect students’ perceptions of self-regulation, feedback, and collaboration?

How are these students’ perceptions aligned with teachers’ perceptions?

The Norwegian context

In Norway, the government decided to keep everything in school as normal as possible, meaning that no adjustments were made to either curricula or the school calendar (OECD, Citation2021). According to a report presented by the OECD after the pandemic, it appears that 55% of the 33 countries with comparable data in this report made changes to the school calendar or curriculum during the pandemic. These changes could involve extending the school year or prioritizing subjects to be taught. The pandemic situation in Norwegian schools was resolved differently. The authorities made rules for when teaching had to be digital, and in some periods all schools were required to have online teaching depending on the infection situation in the country. The authorities also introduced a “traffic light” system that would guide schools in the choice of online teaching (red), teaching at school (green) or hybrid variants (yellow). Beyond that, it was up to each region to regulate this; and it was up to each school and school leader to plan the structure of the school day and to provide support for the teachers in reorganizing their teaching.

The assessment system in Norway could be characterized as a high-trust, low-accountability system (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015). Over 80% of the grades given in upper secondary schools are final grades given by the teachers without the involvement of external examiners. There are no systems or regulations in place to ensure validity or reliability in this final grading process. The Norwegian government trusts teachers and school leaders to maintain the required assessment competence. Final exams (20% of the final grades in upper secondary school) consist of written exams, which are largely developed and administered by national authorities, as well as oral exams, which are administered locally. Students are informed about which subjects they will have for the exam just a few weeks before the exam occurs.

However, the Norwegian education system has been grappling with dilemmas concerning this system comprised of low accountability and transparency on one hand, combined with a high level of trust, decentralization, and teacher autonomy on the other. These dilemmas are particularly evident when it comes to implementing AfL in schools and enhancing learning (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015; Sandvik, Citation2019). At the very beginning, AfL in Norwegian schools was a government-initiated programme and schools received funding to participate. The AfL programme (2010–2018) was rolled out as a top-down intervention. The intention was that some leaders and teachers would learn from research about the desired changes and then “spread” these ideas or practices in their own classroom, among their own colleagues, or to other schools. One of the main consequences of this strategy has been divergent practices and different understandings of what quality in assessments is (Sandvik, Citation2019).

In the Norwegian context, it is required by law for the school leader to provide a professional learning community related to AfL practices at the school level. Since 2020, Norwegian schools have a new curriculum that emphasizes the importance of collaboration in professional development work: “The school shall be a professional learning community where teachers, leaders, and other employees reflect on common values and investigate and further develop their practice” (Ministry of Education, Citation2018, p. 18). Moreover, this new curriculum also identifies how to best use assessment to adapt teaching. Regulations for AfL practices have also been included in the subject-based curricula (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2019). Through these regulations, teachers receive specific advice on how they can work with assessment in ways that can contribute to and promote students’ learning in the different subjects.

Relevant research

For decades, starting with Black and Wiliam in 1998, a growing body of research has been investigating the relationship between how learning is assessed and the learning processes and strategies students employ when engaged in those assessments. Scholars have recognized that AfL is relevant to helping develop students’ autonomy for their understanding of themselves as learners, their confidence and self-efficacy to engage in learning tasks, and their achievement of learning goals (Andrade & Brookhart, Citation2020; Boud, Citation2000; Hayward, Citation2015; Smith, Gamlem, Sandal, & Engelsen, Citation2016). Other studies have pointed to social aspects of AfL, such as the roles that teachers, students, and their student peers play in the learning process, and emphasize that assessment is not something that is done to the learners, but rather is conducted in collaboration with the learners (Pryor & Crossouard, Citation2008; Hayward, Citation2015; Swaffield, Citation2011).

Current research on AfL recognizes that the agency to learn resides with the student and that learning for the future is best built with self-regulation skills and a belief in one’s personal competence to face tasks and endure unexpected challenges (e.g. Smith et al., Citation2016). This claim is supported by Boud (Citation2000) who underlines that empowering students to become independent and self-regulated learners in a life-long perspective should be one of the main goals of education.

The field of research on the relationship between AfL and self-regulated learning (SRL) in the last 20 years has indicated that the processes of regulation are both inherent to both the learner’s thought processes, motivations, and behaviors as well as the social and contextual factors in the enactment of SRL processes (Panadero, Andrade, & Brookhart, Citation2018; Panadero, Broadbent, Boud, & Lodge, Citation2019). Several studies have shown that acquiring SRL skills during education may impact life-long learning and is therefore important for the success of students (De La Harpe & Radloff, Citation2000; Dignath & Büttner, Citation2008).

Students with the ability to set goals, to make flexible plans to meet those goals, and to monitor their progress tend to learn more and do better in school than students who lack those abilities (e.g. Andrade & Brookhart, Citation2020). Zimmerman and Schunk (Citation2011) concluded that SRL occurs when learners set goals and then systematically carry out cognitive, affective, and behavioral practices and procedures that move them closer to those goals. In contrast, less effective learners often have minimal self-regulation strategies and depend on external factors such as their teacher, peers, or the task for guidance and feedback (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Pintrich, Citation2004; Zimmerman, Citation2002).

The relationship between feedback and SRL has been investigated in several studies (Andrade & Brookhart, Citation2014; Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Wiliam, Citation2014), and the main conclusions from these studies are that AfL practices may enhance students’ SRL skills by providing students with the opportunity to practice these skills and by providing (external) feedback that can support student learning (Panadero et al., Citation2018).

Another field of interest is how self-assessment and peer-assessment as two AfL practices can affect SRL. These practices have their emphasis on student involvement and feedback, and studies have found a relationship between peer-assessment and co-regulation or socially shared regulation of learning (Hadwin, Järvelä, & Miller, Citation2011; McCaslin, Citation2009).

The teacher’s role is crucial to providing the conditions for SRL (Pastore & Andrade, Citation2019; Xu & Brown, Citation2016). Assessment-capable teachers not only need to believe in its importance but also need to know how to incorporate key conditions of AfL (Sadler, Citation1989; Thompson & Wiliam, Citation2008) into their teaching. That is, assessment-capable teachers should be able to do the following: collaboratively communicate goals and standards to students so they understand what constitutes quality work in their context, provide substantive opportunities for students to evaluate the quality of their produced work and help them to develop the metacognitive skills to engage in these practices, and provide opportunities for students to modify their own work during its production (Booth, Dixon, & Hill, Citation2016; Booth, Hill, & Dixon, Citation2014). A key element in this process has been developed under the heading of responsive pedagogy (Smith et al., Citation2016), which is also used in this study. At the core of responsive pedagogy is the “recursive dialogue between the learner’s internal feedback and external feedback provided by significant others” (Smith et al., Citation2016); more explicitly, this involves the explicit intention of the teacher to make learners believe in their own competence and ability to successfully complete assignments and meet challenges, to strengthen students’ self-efficacy, and to increase their overall self-concept.

Developing self-regulated learners depends on more than just the individual teacher using AfL practices; the school context and how teachers collaborate to develop assessment literacy has been found in several studies to be the factor with the greatest impact on their assessment practice (Robinson, Citation2011; van Gasse, Vanlommel, Vanhoof, & van Petegem, Citation2017). Nevertheless, it can be challenging for teachers to meet all the expectations to collaborate, to be creative, to present initiatives, and to contribute to innovative solutions (Hill, Citation2011, Citation2016; Sandvik, Citation2019). The teacher as an active part of an assessment culture is considered to be participatory, development-oriented, innovative, and adaptable; the pressure to meet all these expectations can be demanding for many (DeLuca, Rickey, & Coombs, Citation2021). For example, when the national Assessment for Learning initiative was introduced in Norway, it was revealed that many teachers were unmotivated or did not feel an inner commitment to this top-down implementation (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015; Sandvik & Buland, Citation2014). They worked mostly individually and new collaborations that transcended established forms of collaboration in the school were unsuccessful.

Other concerns are related to whether teachers are part of a school-wide commitment to the AfL communities and whether AfL communities have been created to generate change at the school level (Hill, Citation2016; Sandvik, Citation2019). Teachers’ overall assessment literacy within a school is a crucial aspect of such processes and includes the ability of teachers and school leaders to investigate students’ achievements, to develop action plans based on assessment results in order to raise learning outcomes, and to participate in the public debate on the use and abuse of such data (Admiraal, Schenke, Jong, Emmelot, & Sligte, Citation2019; Black, Harrison, Hodgen, Marshall, & Serret, Citation2010; Fullan, Citation2001).

Despite national-wide professional learning programmes designed to engage students in SRL processes, students still perceive teachers as the driving force in classroom learning and consider them to be primarily responsible for identifying learning goals and guiding students in the development of self-regulation learning strategies (DeLuca et al., Citation2018; Klinger, Volante, & Deluca, Citation2012; Marshall & Drummond, Citation2006). In these ways, students still rely heavily on teachers to guide and support learning.

Clark’s (Citation2012) suggestion that formative feedback is a “key causal mechanism” (p. 33) in the development of self-regulation can serve as a summary of the relevant research here. This quote underlines the teachers’ role in developing students’ self-efficacy and their self-regulation learning strategies. Also, literature points to school leadership as crucial to developing professional learning communities at the school level to ensure AfL practices that support student learning in a life-long perspective (Abrams, Varier, & Mehdi, Citation2020). Studies have also examined different organizational factors that influence AfL practices. School factors such as school leadership, positive assessment cultures, and effective collaboration are seen as key drivers of effective AfL practices (Leithwood, Harris, & Hopkins, Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic can certainly be classified as an unexpected challenge that calls for students’ independence and self-regulation. One study conducted among students in lower secondary during the pandemic showed a tendency of lower efforts and lower self-efficacy among low-achieving students (Mælan, Gustavsen, Stranger-Johannessen, & Nordahl, Citation2021). The findings raise growing concerns about home-schooling leading to a larger gap between high- and low-achieving students in lower secondary school. Another study revealed that the impact of home-schooling expanded not only into the educational domain, but also into social (e.g. social distancing), psychological (positive and negative activation), and educational equality (implementation of inclusive education) (Letzel et al., Citation2020).

Gaining more knowledge about how students and teachers were prepared to meet these challenges is significant for understanding how to best support students’ learning. The research presented in this section was used to design the questionnaire and the focus group interview protocols on the following issues: Attitudes toward home-schooling, AfL practices to support student involvement in assessment, collaboration about assessment, assessment literacy among teachers, AfL communities at the school level, and school leaders’ involvement in assessment. The method section explains what was considered in the survey and in the interview protocols.

Method

Data were collected from students in two county municipalities in Norway using a mixed-method approach. All upper secondary schools (80 schools) in these two county municipalities were invited to participate.Footnote1 The schools offer both academic education (50%) and vocational education (50%). The students are aged 16–18. The data material consists of two surveys (n = 4,377 for students [12.5%], n = 598 for teachers [12%]) and focus group interviews with a total of 18 students and 16 teachers. The survey was conducted digitally after Norway’s school reopening in the spring of 2020 and sent to the principals of all 80 schools, who distributed the questionnaire to students and teachers. The focus group interviews were conducted both in-person (one school) and digitally during the autumn of 2020. Pupils and teachers for the interviews were recruited via the principals of four schools that we contacted, two in each county municipality. The selection of schools was based on criteria such as capturing different regions within the county municipality and variation in student performance. The students were chosen to represent both sexes, different subjects and the full range of academic performance. There were some challenges associated with recruiting students because the interviews were conducted in the middle of a pandemic. It was unpredictable if students could participate.

The survey

The questionnaire consisted of closed questions and open responses. The questions (39 items) covered several areas related to teaching and assessment practices during home school. Twelve items are regarded as relevant for the current paper and included in the statistical analysis. These items asked for students’ attitudes toward home-schooling, feedback from teachers, how individual work and collaboration were facilitated by the teachers, and how assessment practices affected their motivation. After analyzing the student survey, we identified four items that were specifically interesting to compare with the teacher survey using descriptive statistics. Those items were:

Involvement

Students: I have received relevant feedback that has helped me to further my learning.

Teachers: Feedback has been aimed at students’ further learning.

Final grading

Students: It is unclear what will be included in the final grading.Teachers: It is unclear what will be included in the students' final grading.

Individual work

Students: I mostly worked individually on assignments. Teachers: The students have mostly worked individually on assignments.

Feedback

Students: I have received relevant feedback that has helped me to further my learning.

Teachers: Feedback has been aimed at students' further learning.

A four-point graded Likert scale (1 strongly disagree – 4 strongly agree) was used in addition to the possibility of answering “do not know.” The questions about assessment are based on previous studies of assessment practices in Norway (Sandvik & Buland, Citation2014). We also developed new questions about teaching and assessment that focus specifically on the situation in schools during the spring of 2020.

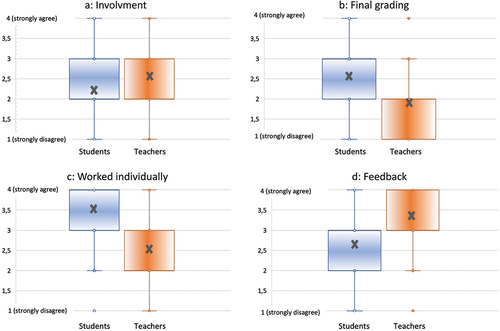

Student survey data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics, and through factor analysis using SPSS (Creswell, Citation2014). Descriptive statistics were used to provide contextual information on participants and general response trends. To be able to compare the two datasets in a manner that easily measured the degree of spread between the two groups involved (students and teachers), we chose box plot presentations (Tufte, Citation2001; Tukey, Citation1977).

Focus group interviews

The qualitative data material consisted of four focus group interviews conducted in four different schools with a total of 16 teachers, and seven interviews with 18 students. These interviews were semi-structured and with the same topic areas as the survey (Bryman, Citation2012). All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interview data were analyzed using the constant comparative method of analysis developed by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998). From an initial analysis of data, a code list was generated and then grouped into broader thematic categories. Codes with a high degree of co-occurrence (i.e. two or more codes used for the same data) or codes that had a logical association were clustered into themes (e.g. “too much individual work,” “too many assignments in all subjects,” and “little organised collaboration with fellow students” were clustered into student involvement in assessment). Direct participant quotations were used to explain and highlight themes. Three researchers reviewed and analyzed all data to ensure high rater reliability. Five themes were identified from the qualitative data: self-regulation, feedback, student involvement, motivation, and self-efficacy. Each category was systematized into sub-themes that corresponded to the survey data.

Results

Results from the student and teacher surveys and interviews are presented separately. First, survey results are described for the overall student and teacher sample. Survey results are presented in relation to the research questions: teachers’ experiences of teaching and assessment practice, students’ experiences of self-regulation, feedback and collaboration, and how teachers’ and students’ experiences are aligned.

Survey results

In the student survey, which is presented in , students were asked to report to what degree they experienced the facilitation of, and involvement in, teaching and assessment during Norway’s home-schooling period in 2020. The 12 items that we chose for this analysis were loaded on three scales: attitudes toward home-schooling, feedback, and individual work. The scree plot, parallel analysis, and interpretability all suggested three sub-scales. The scales had acceptable or good internal consistencies of .85, .78, and .53.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (Item means and standard deviations) and factor analysis for items related to assessment practices.

Three components seem to be clear (). Students’ perception of what effect assessments have on their learning is linked to how students experience individual work (items 1, 2, 3, and 4). There is also a link between how the teachers followed up with their students, how they communicated what students should achieve, what counted in the grading, and how they were involved in assessing their own work (items 5–9). The students reported that they learned most of the subject content by themselves and took greater responsibility for their own learning than before home-schooling began (items 10, 11, and 12).

For a closer look at items especially relevant to our study, a box plot is helpful to compare the students’ answers with the teachers’ answers (). The boxes indicate what 50% of the informants answered (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: agree, 4: strongly agree), X shows the average (median). Blue represents student answers, orange represents teacher answers. The dots represent outliers due to very few answers. Because the box plots only include discrete answers, the 5th option in the survey, “do not know,” is thus excluded from the plots in . However, the percentages of the responders that checked for this option are respectively: A: 9.8% (students)/8.5% (teachers), B: 11.2% (students)/2.2% (teachers), C: 3.3% (students/0.5% (teachers), D: 8.0 (students)/4.4% (teachers).

It can be observed that there is largely agreement between the students’ and teachers’ answers when it comes to the experience of involvement in assessment. Moreover, the median in is low for students in this answer (2.20).

There are differences when it comes to how students experience what is included in the final grading. While teachers believe that this is clear to the students, the students have a different opinion on this question. In , we also see that the median is low (2.50) when it comes to the question of whether the teacher has clearly communicated what is included in the final grading.

The figure also shows that students and teachers have different views about the extent to which they have individually worked on assignments under COVID-19. Students believe that this individual work has largely been the standard, while teachers do not quite have the same perceptions of this phenomenon. Students and teachers have different views on feedback during COVID-19; the teachers are more optimistic in their answers and believe that they have given feedback that promotes learning, while the students have a different perception of the feedback that was given.

Interview results

presents a summary of the findings from both student and teacher interviews. In the next sections, we present the findings from the four teacher group interviews and how they align with findings from interviews with students.

Table 2. Interview themes.

High-performing students were capable of self-regulation

In the interviews, teachers were concerned about how the differences between students’ performances increased during COVID-19. The high-performing students coped with independent work very well, while low-performing students and many students with a foreign-language background had challenges in understanding what independent work to do and how to get support from teachers and/or fellow students. This impression was confirmed in the student interviews. The students who already experienced high managed to create their own structures and learning routines. Several students reported that they even learned more effectively and got higher grades during the pandemic. On the other hand, students who did not master home-schooling life and felt that it was stressful and threatening reported that they did not learn much during this period. They also reported anxiety and were worried about the future. They felt unprepared for higher education because they had mostly worked from home and alone for extended periods.

Teachers were struggling with student involvement and feedback

It is evident that the students experienced challenges related to student involvement and feedback. The interviews revealed that the daily contact with the teacher has been almost absent for many students, while some students have experienced a closer relationship with their teacher during COVID-19. One explanation for why involvement has been difficult is, as the teachers reported in their interviews, that during home-schooling teachers were working from home under quite various conditions. Some had kindergarten-age children at home, others were single parents with children at home who needed help with schoolwork, while other teachers had enough time for follow-up teaching and assessment tasks, along with a genuine interest in trying out new ways of interacting with the students. One teacher expressed these issues as follows:

We do not train the students to be the goalkeeper who will be there alone during the whole match, we train them to be out there and send passes to each other. During COVID-19, there were fewer passes, and then it is the case that those who are normally saved by the team because they are participating just enough to be part of that team, they drop out.

Some teachers also pointed to school leadership as a key to getting this work done in an effective and supportive manner. There were large variations in the way teachers received support in using interactive digital tools. Many teachers expressed a need for more pedagogical guidance than they received in order to cope with the challenges that came with digital teaching and to be able to follow up with the students well enough.

Teachers did not facilitate collaboration

The students reported that they mostly worked alone on school activities and that the teachers organized the collaboration between the students to a lesser extent. Collaboration was mostly student-initiated and not facilitated by the teacher’s instructions. The most active and participating students in regular school were successful in establishing collaborative groups during home-schooling. However, many other students were unsure of how to work on schoolwork alone. The teachers said that the students who didn’t normally have anyone to collaborate with were negatively affected by home-schooling to a much greater extent than other students. The teachers also reported that they replaced many creative and collaborative assignments with individual, written assignments. These types of assignments are commonly used for the assessment of learning. One teacher expressed it this way:

… Less feedback and more approval instead of explaining what could have been done differently. There will be less learning through this kind of control. They get to show that they have done something, but they do not know what they could have done better.

Regarding collaboration between teachers during COVID-19, the interviews revealed that it became more difficult for teachers to collaborate on both teaching and assessment practice. Teacher collaboration was sporadic and teacher-initiated. Although the teachers received some help when it came to the practical technical aspects of home teaching, they experienced little guidance in their professional development work. In their interviews, the teachers asserted that it should be a leadership task to ensure that collaboration between teachers also continues during times of crisis.

Difficulties concerning motivation and self-efficacy

One thing that recurred in the interviews of both teachers and students was the feeling of exhaustion. This finding was pervasive among respondents from all schools. At the beginning of lockdown, both parties experienced the new situation as both exciting and challenging, but then it became too much, and some teachers just became resigned and waited for home-schooling to end. For the teachers, this meant that they did not so much try out new forms of collaboration and teaching but instead used a lot of digital lectures and individual assignments. For the students, this expectation meant that they did not have the strength to show up at school when they could, and when digital teaching began, they often participated with the screen turned off and without getting involved in the teaching.

However, the students reported that the cancellation of exams had positive consequences for most of them. Having time for academic preparation and a clear certainty about the basis for the assessment seemed to strongly impact students’ feelings of self-efficacy.

The teachers also experienced that the students were very happy that the exams were canceled, seeing a great burden fall from their students’ shoulders. The teachers had a much better time teaching toward the goals in the curriculum and had more time for tasks and assignments. However, one problem with the canceled exams was the pressure from school leadership to have enough assignments to ensure a valid assessment and a final grade:

There was a bit like quantity over the quality of the assessment. It was about having as much evidence as possible on paper then. And for me as a teacher, it was very stressful, and I think some of the students thought so too. Do we have to be assessed all the time, can we not just do some tasks in a good process, is it the case that everything must be submitted and assessed? So that exams were cancelled was good, but pressure from school leadership became harder.

To summarize, teachers found it very difficult to be in a situation where final grading had to be done by the individual teacher alone. In a normal situation, the organized professional learning community among teachers would help to ensure a valid and reliable assessment. During the pandemic and with canceled exams, this well-organized system disappeared. The only thing that many leaders seemed to care about was securing enough documentation to do the final grading.

The teachers were concerned with the large differences that arose between both students and teachers:

… And the external factors at home are very different. Some have space in a small bedroom or at the kitchen table with small children at home who need help with their schoolwork. Others have older children and adults and a lot of space around them at home. So those factors were very stressful. Both for us and for the students. We see that differences are amplified depending on what space and resources you have. It became very clear, both for us and the students.

This statement demonstrates an awareness of these differences among the teachers and in interviews with the students, these differences became clear and were commented upon. The teachers were concerned that the socio-economic background became even more important for the students’ experience of motivation and mastery during the pandemic.

Discussion

The new circumstances that COVID-19 brought to schools around the world challenged students, teachers, and school leaders in ways for which they were not prepared. In this study, we have provided a Norwegian upper secondary school perspective from more than 4,000 students and roughly 600 teachers about their reported perceptions of teaching and assessment practices during digital learning. Within this study, a special focus has been placed on self-regulation, feedback, and collaboration using multiple data collection methods: surveys and focus group interviews.

It is evident that teachers had varied experiences with teaching and assessment practices during home-schooling. Survey results indicated that the teachers found that maintaining student involvement and facilitating collaboration among students were difficult. Specifically, in their interviews, teachers expressed concern for their low-performing students because they felt that they were the ones hit the hardest by the difficult learning situation that arose from the COVID-19 lockdown. This finding is also confirmed by other COVID-19 studies (Huber & Helm, Citation2020; Mælan et al., Citation2021). In a longer perspective, this could turn to be an equity problem, because the students’ family background and life situation affected their learning process to a far greater extent than in a normal school situation.

The teachers had a clear view that the varying levels of support they received at their schools was one of the main contributors to their differences. They lacked the support and facilitation from their school leadership to cope with the new challenges resulting from COVID-19. Furthermore, the teachers thought that they would have performed better in their jobs if they had received better pedagogical support. These challenges were also shown in the study by Huber and Helm (Citation2020). Teachers in our study talk about how the collaboration internally at the school was gone and that teachers were also left to themselves. Quality support is crucial to facilitate teachers’ professional work, and is often one of the greatest challenges in AfL implementations (Hill, Citation2016; Robinson, Citation2011; van Gasse et al., Citation2017).

The fact that final exams were canceled lead to increased pressure on the teachers when it came to documenting the students’ improved competence levels. Although some teachers also said that they had more time for instruction and specialization in the subjects because exams were canceled, the main impression is that there was an even greater focus on assessment of learning than before. Teachers became insecure about how they should conduct assessments for learning when they entered the digital learning arena. In this COVID-19 situation, the teachers were unprepared to stand alone and felt a strong need for support. This finding may indicate that teachers in Norway have not developed this competence well enough to transfer experiences and knowledge about assessment in one situation to new situations. This has also been confirmed in studies on AfL implementation in Norwegian schools (Hopfenbeck et al., Citation2015; Sandvik, Citation2019). To support teachers in developing their assessment literacy, it is important to identify the components of assessment literacy that need to be addressed and the developmental paths to follow in order to better inform assessment practice (Pastore & Andrade, Citation2019).

The findings of the interviews with the students across schools confirmed survey results related to self-regulation, feedback, and collaboration during COVID-19. It is evident that the students had widely varied teaching and assessment experiences during home-schooling. The learning situation was experienced as confusing and difficult for many of the students and thus affected their motivation. Other studies that have explored self-regulation during the pandemic found that high-performing students managed to create their own structures and routines for learning and increased their own influence in how they organized their learning (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020). On the other hand, students who were already weaker academically had problems coping with home-schooling (Sandvik et al., Citation2021).

Findings in this study could support findings from other studies that both cognitive as well as social and contextual factors affect the enactment of SRL process (Panadero et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). In particular, studies have found that student involvement and feedback as AfL practices can affect SRL (Hadwin et al., Citation2011; McCaslin, Citation2009). In this study, it was found that the social factors can affect the learning process even more when the conditions for learning change and when AfL as a tool is not used to support students’ SRL. Knowing that acquiring SRL skills with the help of AfL during education may impact life-long learning (De La Harpe & Radloff, Citation2000; Dignath & Büttner, Citation2008) is also an important argument for using AfL as a tool to contribute to equity in education.

It is interesting to see how the teachers confirm the findings from the student study regarding self-regulation. This may indicate that they have comprehensive knowledge of their students and an eye for their needs and wants. The biggest challenges to teachers were, from their point of view, administrative and technical challenges. However, when we looked at other research findings concerning teachers’ professional development and assessment literacy (Pastore & Andrade, Citation2019), it is also possible that the lack of knowledge about how to practice and promote self-regulation among their students causes teachers to fail to see solutions when they encounter new and difficult teaching situations (Booth et al., Citation2016; Thompson & Wiliam, Citation2008). It seems that teachers struggled to provide substantive opportunities for students to evaluate the quality of their own work and to engage and modify their own work during its production (Booth et al., Citation2016, Citation2014).

While teachers seemed satisfied with the feedback that they gave to students during COVID-19, students seem to have different views on how and when they received feedback, and what significance it had for their learning experiences. Studies have shown that formative feedback is a cornerstone in the development of self-regulation (Clark, Citation2012). The results from the survey section of this study indicate that there are strong relations between how teachers gave feedback to their students and communicated what they should achieve, what counted in the grading, and how well they were involved in assessing their own work. Thus, this study emphasizes the core of responsive pedagogy: “recursive dialogue between the learner’s internal feedback and external feedback provided by significant others” (Smith et al., Citation2016).

While the findings from this study provide important information, there are some limitations to this study. It was conducted for a limited time during the COVID-19 lockdown. Because of this, the answers given by both students and teachers were probably strongly colored by their given situations at that time. We are also aware that there is a weakness in the study regarding the data material. The study was conducted at a time when both the researchers and even more so the schools were under pressure. Gaining access to the field was challenging because the study had to be carried out in the middle of a lockdown. The study could have been even better validated by gaining access to lesson plans, student work and other relevant artifacts.

Implications

This study has examined teaching and assessment practices in upper secondary schools in circumstances we had never encountered before. Given the widespread disruptions of regular schooling over the past two years, there is an urgent need to understand how students’ learning has been affected in order to better prepare for similar situations in the future. The study has highlighted both students’ and teachers’ experiences, and we have tried to go both in-depth and in-breadth to shed light on the phenomenon.

Neither students nor teachers in Norwegian schools were prepared to carry out all teaching and assessment via a computer screen. The classroom disappeared, leaving behind every single student and every single teacher, all of them facing challenges that not everyone had the capacity to meet.

Schools in Norway work hard to prepare for new challenges regarding teaching and assessment practices. Based on our findings and previous research, we find two main areas that can be strengthened to prepare for new and unforeseen tasks and challenges: 1) School development in Norway is a national matter and even greater emphasis will be placed on how to apply AfL practices in digital environments. National exams have been canceled three years in a row and there are many indications that final grading by the individual teacher will become even more important. It turns out that there is great uncertainty among the students about final grading and they experience weak communication about both assessment for and of learning. There is a need to develop common understandings of what final grading means for all parties involved to ensure valid and reliable final grading. 2) Student involvement and feedback practices in assessment are areas that Norwegian schools should strengthen. Not only does student involvement help to gain a greater understanding of the goals of learning, but it also helps to strengthen students’ ability to evaluate their own work and regulate their own learning. Since we can additionally refer to the body of research that shows that AfL practices can support SRL, this should be taken seriously in the work of developing assessment skills among teachers and leaders in schools.

Despite a nationwide AfL focus for more than ten years, our study indicates that the mind-set and the practices are not well enough implemented. It may seem that many teachers and schools are not prepared to face unforeseen challenges when it comes to teaching and assessment, which affects the students in situations where they need the teacher’s support the most. Developing an understanding for a more responsive pedagogy among teachers and school leaders would be helpful to adequately prepare educators for when the classroom disappears. A responsive pedagogy puts student agency at the forefront when planning for the future – the student has to be at the core of every step forward. Only in this way can we ensure equity for all in our nation’s “one school for all” policy. We believe that these target areas for future AfL research can inspire continued and more nuanced studies into the impact of the pandemic as it puts stress on teacher assessment skills and into how it can affect self-regulation among students. An increased research effort in exploring AfL practices for self-regulation in the post-pandemic era that we are slowly entering constitutes a promising way to provide recommendations for improved practices that could have a positive impact on students’ life-long learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The study has been approved by the NSD, the Norwegian Center for Research Data.

References

- Abrams, L. M., Varier, D., & Mehdi, T. (2020). The intersection of school context and teachers’ data use practice: Implications for an integrated approach to capacity building. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 69, 100868. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100868

- Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., Jong, L. D., Emmelot, Y., & Sligte, H. (2019). Schools as professional learning communities: What can schools do to support professional development of their teachers? Professional Development in Education47(4), 684–698. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1665573

- Andrade, H., & Brookhart, S. M. (2014). Assessment as the regulation of learning. Philadelphia, USA: Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association.

- Andrade, H. L., & Brookhart, S. M. (2020). Classroom assessment as the co-regulation of learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(4), 350–372. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2019.1571992

- Black, P., Harrison, C., Hodgen, J., Marshall, B., & Serret, N. (2010). Validity in teachers’ summative assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(2), 215–232. doi:10.1080/09695941003696016

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. doi:10.1080/0969595980050102

- Booth, B., Dixon, H., & Hill, M. (2016). Assessment capability for New Zealand teachers and students: Challenging but possible. Set: Research Information for Teachers, 2(2), 28–35. doi:10.18296/set.0043

- Booth, B., Hill, M. F., & Dixon, H. (2014). The assessment capable teacher: Are we all on the same page? Assessment Matters, 6, 137–157. doi:10.18296/am.0121

- Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151–167. doi:10.1080/713695728

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bubb, S., & Jones, M. A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers, and teachers. Improving Schools, 23(3), 209–222. doi:10.1177/1365480220958797

- Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 205–249. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

- Cowie, B. (2009). My teacher and my friends helped me learn. In D. M. McInerney, G. T. L. Brown, & G. A. D. Liem (Eds.), Student perspectives on assessment (pp. 85–105). Information Age.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Davis, A., Solberg, V. S., de Baca, C., & Gore, T. H. (2014). Use of social emotional learning skills to predict future academic success and progress toward graduation. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 19(3–4), 169–182. doi:10.1080/10824669.2014.972506

- De La Harpe, B., & Radloff, A. (2000). Informed Teachers and Learners: The importance of assessing the characteristics needed for lifelong learning. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 169–182. doi:10.1080/713695729

- DeLuca, C., Chapman-Chin, A. E., LaPointe-McEwan, D., & Klinger, D. A. (2018). Student perspectives on assessment for learning. The Curriculum Journal, 29(1), 77–94. doi:10.1080/09585176.2017.1401550

- DeLuca, C., Rickey, N., & Coombs, A. (2021). Exploring assessment across cultures: Teachers’ approaches to assessment in the U.S., China, and Canada. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1921903. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2021.1921903

- Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning, 3(3), 231–264. doi:10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

- Flack, C. B., Walker, L., Bickerstaff, A., Earle, H., & Margetts, C. (2020). Educator perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning in Australia and New Zealand. Pivot Professional Learning.

- Fullan, M. G. (2001). Leading in a culture of change. Jossey-Bass.

- Hadwin, A. F., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2011). Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 65–84). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

- Havnes, A., Smith, K., Dysthe, O., & Ludvigsen, K. (2012). Formative assessment and feedback: Making learning visible. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 38(1), 21–27. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2012.04.001

- Hayward, L. (2015). Assessment is learning: The preposition vanishes. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 27–43. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.984656

- Hill, M. F. (2011). ‘Getting traction’: Enablers and barriers to implementing assessment for learning in secondary schools. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 347–364. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2011.600247

- Hill, M. F. (2016). Assessment for learning community: Learners, teachers, and policymakers. In I. D. Wyse, L. Hayward, & J. Pandya (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 772–789). SAGE.

- Hopfenbeck, T. N., Flórez Petour, M. T., & Tolo, A. (2015). Balancing tensions in educational policy reforms: Large-scale implementation of assessment for learning in Norway. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 44–60. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.996524

- Huber, S. G., & Helm, C. (2020). COVID-19 and schooling: Evaluation, assessment and accountability in times of crises—reacting quickly to explore key issues for policy, practice and research with the school barometer. Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 32(2), 237–270. doi:10.1007/s11092-020-09322-y

- Jónsson, Í. R., Smith, K., & Geirsdóttir, G. (2018). Shared language of feedback and assessment: Perception of teachers and students in three Icelandic secondary schools. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 56, 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.11.003

- Klenowski, V. (2009). Assessment for learning revisited: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 16(3), 263–268. doi:10.1080/09695940903319646

- Klinger, D. A., Volante, L., & Deluca, C. (2012). Building teacher capacity within the evolving assessment culture in Canadian education. Policy Futures in Education, 10(4), 447–460. doi:10.2304/pfie.2012.10.4.447

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. doi:10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

- Letzel, V., Pozas, M., & Schneider, C. (2020). Energetic students, stressed parents, and nervous teachers: A comprehensive exploration of inclusive homeschooling during the COVID-19 crisis. Open Education Studies, 2(1), 159–170. doi:10.1515/edu-2020-0122

- Mælan, E. N., Gustavsen, A. M., Stranger-Johannessen, E., & Nordahl, T. (2021). Norwegian students’ experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(1), 5–19. doi:10.1080/08856257.2021.1872843

- Marshall, B., & Drummond, M. J. (2006). How teachers engage with assessment or learning: Lessons from the classroom. Research Papers in Education, 21(2), 133–149. doi:10.1080/02671520600615638

- McCaslin, M. (2009). Co-regulation of student motivation and emergent identity. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 137–146. doi:10.1080/00461520902832384

- Ministry of Education. (2018). Overordnet del av læreplanverket [Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education]. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2019). The national curriculum. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://sokeresultat.udir.no/finn-lareplan.html?fltypefiltermulti=Kunnskapsl%C3%B8ftet%202020&spraakmaalform=Engelsk

- OECD (2021). The state of school education: One year into the COVID pandemic. https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en.

- Panadero, E., Andrade, H., & Brookhart, S. (2018). Fusing self-regulated learning and formative assessment: A roadmap of where we are, how we got here, and where we are going. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 13–31. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0258-y

- Panadero, E., Broadbent, J., Boud, D., & Lodge, J. M. (2019). Using formative assessment to influence self- and co-regulated learning: The role of evaluative judgement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(3), 535–557. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0407-8

- Pastore, S., & Andrade, H. L. (2019). Teacher assessment literacy: A three-dimensional model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 84, 128–138. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.05.003

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. doi:10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x

- Pryor, J., & Crossouard, B. (2008). A socio‐cultural theorisation of formative assessment. Oxford Review of Education, 34(1), 1–20. doi:10.1080/03054980701476386

- Regulations of the Education Act (2020). Forskrift til opplæringslova. Kapittel 3. Individuell vurdering i grunnskolen og i vidaregåande opplæring. (nr.1474) [Regulations to the Education Act. Chapter 3. Individual assessment in primary school and in upper secondary education. (nr.1474)]. Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2006-06-23-724/KAPITTEL_5#KAPITTEL_5

- Robinson, V. (2011). Student-centered leadership. Jossey Bass.

- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF00117714

- Sandvik, L. V. (2019). Mapping assessment for learning (AfL) communities in schools. Assessment Matters, 13, 44–70. doi:10.18296/am.0037

- Sandvik, L. V., & Buland, T. (2014). Vurdering i skolen. Utvikling av kompetanse og fellesskap. Sluttrappport fra prosjektet ‘Forskning på individuell vurdering i skolen’ (FIVIS). [Assessment in schools. Developing competence and professional learning communities]. NTNU and SINTEF. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/upload/forskning/2015/fivis-sluttrapport-desember-2014.pdf

- Sandvik, L. V., Smith, K., Strømme, J. A., Svendsen, B., Sommervold, O. A., & Angvik, S. A. (2021). Students’ perception on assessment during COVID 19. Teachers and Teaching, 1–14. doi:10.1080/13540602.2021.1982692

- Smith, K., Gamlem, S. M., Sandal, A. K., & Engelsen, K. S. (2016). Educating for the future: A conceptual framework of responsive pedagogy. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1227021. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1227021

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Swaffield, S. (2011). Getting to the heart of authentic assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 433–449. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

- Thompson, M., & Wiliam, D. (2008). Tight but loose: A conceptual framework for scaling up school reforms. In I. C. Wylie (Ed.), Tight but loose: Scaling up teacher professional development in diverse contexts (pp. 1–44). Educational Testing Service (ETS).

- Tufte, E. R. (2001). The visual display of quantitative information. Graphic Press.

- Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory data analysis. Addison Wesley.

- van Gasse, R., Vanlommel, K., Vanhoof, J., & van Petegem, P. (2017). The impact of collaboration on teachers’ individual data use. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(3), 489–504. doi:10.1080/09243453.2017.1321555

- Wendelborg, C., Dahl, T., & Buland, R. M. O. T. (2020). Elevundersøkelsen 2019. Analyse av Utdanningsdirektoratets brukerundersøkelser. NTNU Samfunnsforskning.

- Wiliam, D. (2014). Formative assessment and contingency in the regulation of learning processes (paper presentation). American educational research association (AERA), April, Philadelphia, USA. American educational research association (AERA). https://famemichigan.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Wiliam-Formative-assessment-and-contingency-in-the-regulation-of-learning-processes.pdf

- Xu, Y., & Brown, G. T. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 149–162. doi:10.1016/J.TATE.2016.05.010

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

- Zimmerman, B., & Schunk, D. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performances. Routledge.