ABSTRACT

Despite its growing ubiquitous presence, the smart city continues to struggle for definitional clarity and practical import. In response, this study interrogates the smart city as global discourse network by examining a collection of key texts associated with cities worldwide. Using a list of 5,553 cities, a systematic webometric exercise was conducted to measure hit counts produced by searching for “smart city.” Consequently, 27 cities with the highest validated hit counts were selected. Next, 346 online texts were collected from among the top 20 hits across each of the selected cities, and analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively using AntConc software. The findings confirm, first, the presence of a strong globalizing narrative which emphasizes world cities as “best practice” models. Second, they reveal the smart city’s association—beyond the quest for incremental, technical improvements of current urban systems and processes—with a pronounced transformative governance agenda. The article identifies five critical junctures at the heart of the evolving smart city discourse regime; these shed light on the ongoing boundary work in which the smart city is engaged and which contain significant unresolved tensions. The paper concludes with a discussion of resulting implications for research, policy, and practice.

Introduction

Following in the footsteps of the sustainable (or eco) city, the smart city has turned ubiquitous, heralding an advanced global urban future. Within less than a decade it has become a major leitmotif in the discourse on urban development (Crivello 2015). For Moir et al. (Citation2014), its global significance arises from “smart” superseding “sustainability” as a main prism through which the future of cities is viewed. Its ubiquity manifests itself in the transnational circulation of smart city concepts and policies as well as the rapid proliferation of on-the-ground initiatives across regions in both the Global North and South (e.g., Caragliu et al. Citation2014; Datta Citation2015; Watson Citation2015; Karvonen et al., Citation2018).

Within this context of a globally mobile phenomenon, an essential aspect of the smart city is its discourse: it shapes concepts and programs, and is a key means by which ideas and practices are borrowed, transmitted, and reproduced within different geographical, cultural, and institutional settings. (As such, discourse relates to, and is co-constitutive of, the processes of urban policy mobilities: see, e.g., McCann Citation2011; Baker and Temenos Citation2015; Crivello Citation2015; Wiig Citation2015). The smart city can thus be considered a “global discourse network” (derived from Khor, 2013): a collectivity of locally contextualized yet globally interconnected discourses. This perspective is useful for analyzing both discourse structures and dynamics, and how this produces particular interlocking narratives and meaning. Consequently, this article interrogates the smart city, as global discourse network, starting with a comprehensive list of over 5,000 cities, which is used to run a semi-automated online search for harvesting smart city-related web addresses. Subsequently, 27 cities with the most online hits are selected; from these, 346 text files (in English) are collected and treated to detailed cross-comparative quantitative and qualitative analyses. Guiding this research are the following three central questions: (1) Which cities worldwide are mainly associated with contemporary smart city discourses (in English language)? (2) What are the key dimensions of this discourse, and how do they interrelate? (3) How are particular narratives mobilized to legitimize the smart city, and what critical junctures reveal themselves? The findings not least also aim to highlight opportunities for alternative scenarios on smart cities.

The webometric approach used in this study differs from other recent bibliometric analyses of the smart city (e.g., De Jong et al. Citation2015; Duran-Sánchez et al. 2017; Fu and Zhang Citation2017; Mora et al. Citation2017) as follows: the latter, by design, confine themselves to the scholarly literature (through Web of Science, Scopus, Science Citation Index etc.; NB Mora et al.’s [2017] additional inclusion of some grey literature databases) and principally focus on analyzing the smart city as an emergent research agenda and evolving scientific knowledge domain. In contrast, the present webometric analysis (drawing on Almind and Ingwersen, 1997 and Thelwall et al., Citation2005, among others) seeks to capture a broader online discourse which encompasses diverse policy and practice communications linked to actual cities worldwide. As such, it accesses global online sources that shed light on how the smart city is discursively constructed by a range of involved actors (municipal authorities, national agencies, international organizations, think tanks, consultants, etc.). Relatedly, the study pursues a particular angle of inquiry informed by critical discourse theory and based on corpus linguistic analysis; namely, how the smart city is constituted as a discourse regime (of which, more below) and what critical insights this can offer for future directions in smart city research, policy, and practice.

The burgeoning academic literature on smart cities has identified a number of emergent themes and critical perspectives which help inform the present analysis. One such theme, reflecting a critique of neoliberal urban policy, concerns the relationship between smart city initiatives and the corporatization of city management and, more broadly, new forms of technocratic governance (e.g., Allwinkle and Cruickshank Citation2011; Greenfield, Citation2013; Townsend, Citation2013; Söderström et al., Citation2014; Vanolo, Citation2014; Angelidou, Citation2015; Calzada and Cobo, 2015; Hollands, Citation2015; Kitchin, Citation2015; Przeybilovicz et al., 2018). Another theme relates to the smart city conceived of as experimental urbanism realized through new urban spaces and practices across multiple scales (e.g., Evans et al., Citation2016; Scholl and Kemp, Citation2016; Caprotti and Cowley, Citation2017; Raven et al., Citation2017). From yet another perspective, the smart city is interrogated in terms of its potential to recondition norms and practices of citizenship, the public sphere, and social engagement (e.g., Linders, Citation2012; Gabrys, Citation2014; Saunders and Baeck, Citation2015; Cowley et al., Citation2017; Joss et al., Citation2018; Cardullo and Kitchin, Citation2017, Citation2018). Finally, the relationship between smart city innovation and sustainable development has come in for critical examination (e.g., Gargiulo Morelli et al., Citation2013; Viitanen and Kingston, Citation2014; Haarstad, Citation2017; Kudva and Ye, Citation2017; Trindade et al., Citation2017; Chang et al., Citation2018). These and other scholarly discussion points, then, provide useful analytical orientation for the present examination of original source texts associated with the global smart city discourse.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: the next couple of sections expand on the study’s conceptual framework as well as the methodological approach used; this is followed by the presentation and discussion of the findings, which in turn leads to the conclusions where implications for research, policy, and practice are highlighted.

A Global Discourse Network

The smart city is more than “mere” discourse.Footnote1 Indeed, much of its critique centers upon the problematique of the “place-less” corporate-governmental discourse (e.g., Hollands, Citation2008; Shelton et al., Citation2015; Söderström et al., Citation2014; Kitchin, Citation2015). In response, recent research has inquired into how the smart city is constituted by, and situated within, particular settings (e.g., Karvonen et al., Citation2018). This acknowledges the importance of the smart city, like other grand urban visions, having to “negotiate with the spatiality and the geography of place” (Harvey, Citation2000: 179–180), through which the “unbound” conceptual smart city becomes the “bounded” enacted smart city. However, contemporary research has shown that even within on-the-ground practice contexts, the discourse aspect remains salient: for example, Cowley et al. (Citation2017) traces how smart city initiatives across six British cities were co-determined by a national discourse on “future cities” instigated by the UK government. Moreover, the authors of that article show that local smart city practices have a strong discursive component (pamphlets, websites, etc.), while spatio-physical articulations may remain ephemeral. Hence, discourse is of central importance concerning both how it variously intervenes within particular local practice settings, as well as how it interacts across geographical and institutional boundaries.

Applying the perspective of global discourse network to the analysis of the smart city is useful in that it draws attention, on one hand, to the textual circulation and interaction across networks and, on the other, to the resulting globalization of smart city discourse centered upon a series of distinctive narratives. The perspective is particularly apt, moreover, because it helps reveal—a key finding of this research—not just the emergent global discourse about smart cities, but also the significance of the “global” as a constitutive part of what is posited as a smart city. As one of the texts analyzed encapsulates it: “The smart city will understand its global responsibility” (Los Angeles_16).Footnote2

A global discourse network has several characteristics which render it potentially expansive (the following draws on Khor, 2013; Phillips and Jorgensen, Citation2004; Atkinson et al., Citation2010; Kitchin, Citation2014). Substantively, discourse embodies a certain vision and normative stance. For the smart city, this normativity relates broadly to a commitment to urban development through technology-enabled ecological modernization.Footnote3 The smart city thus espouses a certain “worldview”: the surrounding discourse serves to circulate and cement this within urban policy and practice. Discourse is globalizing in a dual sense: in its aspiration to render the smart city a universal urban paradigm and in its dynamic of propagating ideas and practices. This universalizing force, however, need not result in homogeneity. Rather, it functions by connecting diverse discourse acts and communities. Here, the notion of discourse networks becomes relevant, drawing attention to multiple contextualized discourses and their interconnectedness. On one hand, localized discourses absorb and re-work the circulating discourse into particular geographical, cultural and organizational settings; on the other, they feed the evolving global discourse as complimentary or contestatory variations. As such, a global discourse network has an inherently self-generative dynamic.

Yet, it is important to note that not all acts of discourse are equal: discourse has agency; it is generated and promoted, with varying degrees of success, to articulate, steer, and impose particular norms and practices (Weiss and Wodak, 2003; Fairclough, Citation2013). It is likely, for example, that a smart city discourse promoted by a powerful coalition of actors, mediated through well-established transnational channels, and adopted by prominent local actors enjoys greater presence than a more limited discourse advanced on the fringe. Given such agency, discourse produces and transmits power; it is both an instrument and effect thereof. Discourse, then, is also a site of hegemonic struggle, where differing versions and interpretations of that discourse vie for recognition and influence. However, in the process of one specific articulation of discourse becoming dominant and standardized, there are typically concurrent alternative articulations emerging that seek to modify and challenge such standardization (Khor, 2013: 23). A global discourse network, therefore, contains within it latent instability. Consequently, a key focus of discourse analysis should be on elucidating critical junctures where issues are subject to interrogation and debate.

At the textual level, these discourse characteristics can be analyzed by examining how certain meanings are produced and for what purpose (Wood and Kroger, Citation2000; Hoey, Citation2000). Of particular interest are (competing) storylines and narratives, through which the smart city is (re-)presented in particular ways. Likewise, attention should be on exclusionary tendencies; what is left out or incomplete from particular storytelling. Importantly, such analysis requires probing interpretation since, as Atkinson et al. (Citation2010: 12) note, “narratives are never ‘innocent’ nor are their underlying ‘master codes’ immediately accessible.” Hence, the analyst is prompted to apply interpretative categories or codes, to make sense of how different meanings and stances are deployed. Ultimately, the aim is to gain a critical theoretical understanding of how the smart city is constructed as a discourse regime, “a set of interlocking discourses that justifies and sustains new developments and naturalizes and reproduces their use” (Kitchin, Citation2014: 113). Here again, discourse is not a passive, innocent medium, but instead is deployed quite purposefully to “remake the world in a particular vision” in a way which makes it seem natural and desirable (Kitchin, Citation2014: 113). As such, the smart city as global discourse network rightly deserves close scrutiny.

Methodology

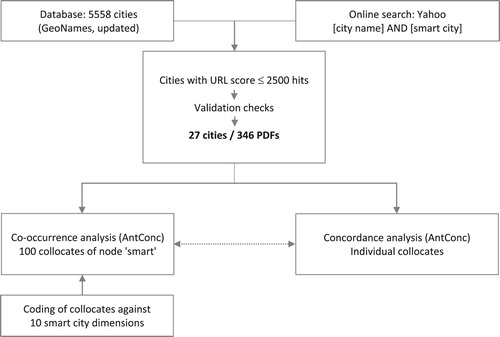

Establishing a suitable methodology is challenging, given the task of demarcating the expansive smart city discourse network and analyzing the resulting large text corpus. Hence, significant effort was required to design a robust methodology consisting of two main parts: first, capturing the global discourse network using the logic of the online search engine,Footnote4 to harvest a representative set of texts associated with cities worldwide; and second, treating the compiled corpus to a combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses with the help of AntConc (Anthony, 2016), a freeware tool for corpus linguistic research, using custom-made coding categories. illustrates the overall research design, and Box 1 elaborates the step-by-step methodological procedure (with further technical information contained in the footnotes). As shown, much of the research is protocol-driven following systematic webometric and corpus linguistic methodology. At the same time, the research entails complementary interpretive analysis, an essential element of critical discourse analysis (e.g., Fairclough, Citation1995; Gill, Citation2000; Haworth, Citation2000; Phillips and Jorgensen, Citation2004). Several established validation and triangulation techniques are applied to render the research both robust and meaningful. Concerning the choice of suitable Web search engines and the accuracy of search engine hit counts, as well as the need for data cleansing and validation techniques, the study draws on both published literature (e.g., Thelwall et al., Citation2005; Uyar, Citation2009; Martínez-Sanahuja and Sánchez, Citation2016; Sánchez et al., Citation2018) and own practical testing (pilot runs). Concerning the use of large-scale corpus analysis (“distance reading” techniques), the paper draws, inter alia, on Stubbs (Citation2007), Froehlich (Citation2015), and Anthony (Citation2016).

Step 1: Webometric analysis of global smart city discourse and sampling of cities

1.1 Compilation of global list of cities

• Use GeoNames database to compile list of cities with population ≥100K: 4,235 cities

• Crosscheck additional sources (UN Demographic Yearbook; population data etc.) to add missing cities and cities with alternative spelling (e.g., Köln/Cologne): 1,318 cities

• Result: consolidated list of 5,553 cities

1.2 Webometric analysis of association of city names with “smart city”

• Use Yahoo Advanced Search; choose settings ´language = English´ and ´file-type = pdf´

• Measure hit counts with search string: “smart city” + <city name X> ; as proxy for extent to which city X is implicated in global smart city discourse

• Use VBA Excel to automate search process for all 5,553 city names; nine repeat search runs across four locations, different computers and different dates (within 15-day window) to increase accuracy and validity

• Calculate most robust hit count value for each city name using probability density test (most probable hit-count among retrieved counts per city) and mode test (which exact hit count retrieved most per city)

• Result: hit range of 0–10,700, with seven cities (no. 1–7) in top quartile (≥7,500 hits); 4 cities (no. 8–11) in upper middle quartile (5,000–7,499 hits); 45 cities (no. 12–56) in lower middle quartile (2,500–4,999 hits); and 5,497 cities in bottom quartile (≤2500 hits)

1.3 Selection and validation of sample of cities

• Select cities no. 1–56 in the 2,500–10,700 hit range (excluding cities in bottom quartile); for each download all 20 PDF files listed on first search page using above search string (step 1.2)

• Check validity of PDF files for each city. This results in removal of 29 cities as follows: (a) 12 duplicate city names, where PDFs refer to another same-named city (e.g., all PDFs listed under London/CA are the same as/refer to those listed under London/UK; ditto e.g., Barcelona/VE and Barcelona/ES); (b) 12 cases where PDFs refer to generic words contained in city names but bear no actual relation to cities (e.g., all PDFs listed under Mobile/USA only contain generic discourse on “mobile;” ditto e.g., Enterprise/USA, Sale/MR); (c) five cities removed where no. of validated PDFs is ≤4 and thus deemed too small (Hamilton/NZ; Hamilton/USA; Reading/UK; Vancouver/USA; Washington/USA).

• For the remaining 27 cities, remove any duplicate or unrelated PDFs, resulting in varying numbers of PDFs harvested per city (18/20 each for Vienna and Copenhagen, to 8/20 each for Melbourne and Toronto)

• Result: sample of 27 cities, with total of 346 validated PDFs containing relevant “smart city” discourse

Step 2: Text corpus analyses (with AntConc software)

2.1 Co-occurrence analysis (quantitative)

2.1.1 Compilation of text corpus

• Convert 346 PDF files into text files and assemble into single text corpus; upload on AntConc software

2.1.2 Calculation of 100 most frequent collocates of “smart”

• Apply co-occurrence function to identify the 100 most frequent collocates of node “smart.” Twenty words to the left/right of ‘smart’ are measured, the maximum window setting in AntConc, recommended for enlarged textual analysis

• T-score is used to calculate statistical likelihood of association between individual collocates and the node ‘smart’ (literature recommends T-score over MI-score for smaller text corpus as used here). In AntConc, the T-score includes a built-in statistical adjustment, whereby a given collocate (within the window setting) with a proportionally high frequency outside the window receives a measured downward adjustment (see Stubbs, Citation2007; Anthony, Citation2016)

2.1.3 Categorization of 100 collocates according to 10 smart city dimensions

• Define 10 broad smart city dimensions: digital technology; infrastructure; governance; economy; society; environment; sustainability; spatial development/planning; experimentation/innovation; international. Derived collectively by the research team drawing on (a) literature and (b) an initial scoping analysis of the corpus (viewing of text strings containing individual collocates)

• Assign each collocate to one of 10 dimensions; if needed, view associated text strings in corpus for cross-checking. Collocates without clear/unambiguous attribution (e.g., “concept,” “future”) are assigned to category “unclassified”

• Result: 100 most frequent collocates (Appendix 1); categorization in terms of 10 “smart city” dimensions (; 3)

2.2 Concordance analysis (interpretive-qualitative)

2.2.1 Contextual analysis of 10 smart city dimensions

• Develop a contextual understanding of each dimension by analyzing corresponding collocates individually in relation to the discursive contexts in which they are used across the corpus. Apply the concordance function (and related sorting options) to obtain a complete set of text strings containing a given collocate; scan the set overall and subject multiple sub-sections to in-depth analysis to identify discursive themes and patterns. Repeat analysis with other collocates

• Use of a protocol to ensure systematic, consistent analysis of each dimension; as well as triangulation whereby each dimension is analyzed separately by two researchers and the combined results reviewed by the team overall

2.2.2 Identification of overarching themes and critical junctures

• Interpret findings (2.2.1) collectively (full research team) to discern interlocking discourse narratives and counter-narratives across 10 smart city dimensions and thus elucidate critical junctures

• Result: Thematic discussion in terms of five critical junctures

Step 1: Webometric Analysis of Global Smart City Discourse

Concerning research question (1) Which cities worldwide are mainly associated with contemporary smart city discourses (in English language)?, an online census was carried out of cities with ≥100 K inhabitants, with the information collected consisting of publicly available smart city documents. Linking the online documentary search to a global list of cities provides useful insight into the structural dimensions of the discourse network; furthermore, the harvested collection of documents represents an important interface between the smart city discourse oriented internally within cities and externally across the global network. The global list of cities is based on the open-access GeoNames (n.d.) database entailing 4,235 names of cities, to which 1,318 city names (with unusual spelling, or not recognized as having ≥100 K inhabitants by GeoNames) were added, resulting in a total of 5,553 cities (Step 1.1, Box 1). The online documentary search—using the search query [city name] AND [smart city]—was conducted on Yahoo (Step 1.2, Box 1). Following testing, this search engine was selected as it meets three concurrent criteria (unlike e.g., Google and Bing)—namely, the ability to use Booleans; apply semi-automated searches; and filter for PDF documents. Restricting online material to PDF has the dual benefit of returning not only more stable results (through reduced volatility of hit counts), but also more meaningful outputs: PDFs are more likely to entail relevant smart city texts (municipal documents, policy briefs, conference reports, etc.) and less likely to yield arbitrary results owing to the ubiquitous linguistic use of “smart” (e.g., “smart holiday;” “smart Christmas parties”). VBA Excel was used to run multiple online harvests over a 15-day period (See Uyar, Citation2009) and produce an aggregated dataset (August–September 2016). Two complementary validation techniques were applied to run checks on the raw data obtained. The resulting list of smart city hits (score value) for all 5,553 cities is available on the lead author’s ResearchGate profile.

As a full analysis of URL scores across all 5,553 cities would have been too resource-intensive, only cities in the 2,500–10,700 hit range were selected (Step 1.3, Box 1).Footnote5 This selection process yielded 56 cities. For each of these, the URLs were checked for false results: for example, the hits harvested for “Mobile” are unrelated to the city of Mobile (USA), instead referring mostly to “smart mobile” phones; and the hits for the city of London (CA) actually all relate to London (UK). Twenty-four cities were thus eliminated from the list. An additional five cities were removed because they yielded too few (≤4) valid PDF documents from among their 20 top URLs. The resulting final selection, therefore, includes 27 validated cities (See ). For each of these, the 20 top URLs were considered for inclusion in the aggregated corpus, potentially yielding 540 PDF files. However, once invalid files are discarded,Footnote6 the final aggregated corpus amounts to 346 validated files. While this selection of texts by no means encapsulates the smart city global discourse in its entirety—it is restricted to English language, excludes some discourse types (images, etc.), and does not cover cities in the bottom quartile (≤2,500 hits)—the methodical approach does produce a sufficiently robust sample suitable for analysis.

Table 1. 27 cities co-constituting the smart city global discourse network

As such, the harvested texts capture the recent period of rapid rise of smart city discourse globally: the average year of publication is 2014, ranging from 1999 to 2016 but with only four texts from before 2009. Furthermore, in line with the webometric approach, the diverse origins of the texts confirm a distributed network of actors involved in promulgating the smart city: 78 percent of the documents are by organizations that are not themselves the initiators of the smart city initiatives being reported, whereas 22 percent are by initiators themselves. In terms of organizational types, 38 percent of documents were published by private sector organizations (including international consultancy firms), 27 percent by municipal authorities, 17 percent by research organizations, 12 percent by other governmental organizations, 3 percent by international organizations, and 2 percent by NGOs (and 1 percent classified “other”).

Step 2: Quantitative and Interpretive-Qualitative Textual Analyses

The corpus of 346 files forms the basis of textual examination aimed at answering research questions (2) What are the key dimensions of this discourse, and how do they interrelate? and (3) How are particular narratives mobilized to legitimize the smart city, and what critical junctures reveal themselves? Following published guidance (Stubbs, Citation2007; Froehlich, Citation2015; Anthony, Citation2016), the first type of analysis using the AntConc software entailed a co-occurrence analysis based on measuring 20 collocates (words) each to the left and right of the node “smart” (Step 2.1.2, Box 1).Footnote7 This frequency analysis produces a ranking of words associated with smart city. As recommended in the literature, the T-scoreFootnote8 was used to establish the statistical likelihood of association between individual collocates and the node “smart.” Appendix 1 shows the 100 most associated collocates for the overall corpus. The same exercise was conducted for each individual city corpus.

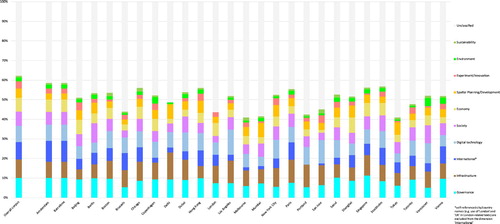

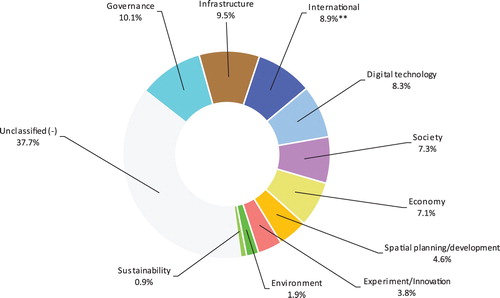

In order to categorize and compare the findings of the co-occurrence analysis, all collocates were coded according to one of ten smart city dimensions (Step 2.1.3, Box 1):Footnote9 (1) digital technology; (2) infrastructure; (3) governance; (4) economy; (5) society; (6) spatial planning/development; (7) environment; (8) sustainability; (9) experimentation/innovation; (10) international. Collocates that could not be unambiguously coded to any of these categories were designated “unclassified.” shows the related results for the overall corpus, while shows the comparative profile across the 27 cities.

Figure 2. Distribution of 10 smart city dimensions (100 collocates) for overall corpus*

Note: *Percentage calculation based on T-score (sum of T-score of individual collocates).**Self-referenced city/country names (e.g. use of ‘London’ and ‘UK’ in London-related texts) are excluded from the dimension ‘International’.

Complementing this quantitative analysis, the AntConc concordance tool was used for additional qualitative analysis, whereby individual collocates are examined in relation to the contexts in which they are used across the corpus (Step 2.2.1/2, Box 1).Footnote10 As an essential part of critical discourse analysis, this interpretive-qualitative inquiry was accomplished for collocates across all 10 smart city dimensions. In order to ensure robustness, the analysis was triangulated, with one researcher responsible for primary analysis, another researcher acting as reviewer, and the team as a whole interpreting the findings (presented further below in the “critical junctures” section).

Findings

Smart Cities as World Cities

This section reports the webometric results from Steps 1.1–1.3 (Box 1). The 27 cities (and associated texts) identified through the online search process are evidently part of a much larger smart city discourse network, although they occupy a central place as measured by their URL scores. Nine of the cities are located across Australasia, another nine in Europe, eight in North America, and one in the Middle East, with none from Africa or Latin America (See ). What is particularly notable is the strong presence of world cities: 13 are national capitals, while 21 are ranked as “alpha” world cities (GaWC, n.d.). The four exceptions (neither capital nor “alpha” ranking) are Boston (USA), Portland (Oregon, USA), San José (USA), and Vancouver (CA). Following the logic of the online search process, it may be unsurprising that world cities, which already enjoy a proportionally large online presence, should score high in terms of smart city online hits; conversely, it may be expected that cities with considerable on-the-ground smart city activity albeit limited international profile produce comparatively lower scores. However, notwithstanding the possibility of a certain inherent methodological bias, the results of this online search exercise are broadly in line with other international surveys. For example, all “top 10” smart cities (Vienna, Toronto, Paris, New York, London, Tokyo, Berlin, Copenhagen, Hong Kong, Barcelona) listed in an early survey by Cohen (2012; also 2014) feature in the group of 27. More recently, 7 of the 10 top-ranking smart cities (New York, London, Paris, Boston, Amsterdam, Chicago, Seoul) in the 2016 IESE Cities in Motion Index (Forbes, 2016) are among the group of 27. Elsewhere, 21 of the 27 cities appear in the survey by Gibson et al. (Citation2015) on “cities as connectors” (referring to digital-infrastructural connectivity).

Furthermore, the harvested texts themselves make repeated cross-reference to fellow cities in the group of 27, positing them as part of a global network and as standard bearers of smart city innovation. For instance, one document references “developments in global cities at the forefront of the smart city agenda (e.g., Chicago, Boston, Barcelona, and Stockholm)” (Stockholm_9). Other texts simultaneously mobilize more regional, smaller cities into the global network:

Thus, it is not only major cities, such as Boston, Chicago, Stockholm, Barcelona, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Berlin, London, and Manchester which have benefitted from giving a focus to “smart.” Smaller communities, such as Friedrichshafen, Aarhus, Santander, Paredes, Peterborough, and Bristol are attracting start-ups and generating growth on the back of a firm commitment to Smart City concepts. (Amsterdam_8)

Leverage London’s global city role: working with other EU (such as Barcelona, Gothenburg, Copenhagen, and Amsterdam) and global cities (such as New York, Singapore, and Tokyo) to share experience, and develop “lighthouse” projects that will demonstrate new approaches at scale … (London_1)

Dimensions of the Smart City Discourse

This section reports the quantitative textual results from Steps 2.1.1–2.1.3 (Box 1). A key benefit of corpus analysis, using AntConc, is to enable textual analysis at large scale (so-called “distance reading”: Froehlich, Citation2015); here, encompassing over 1.318 million words across 346 documents. By conducting a co-occurrence analysis of words surrounding the node “smart,” a robust measure is obtained of the most frequent word associations, which in turn provides insight into how the smart city is discursively defined. Appendix 1 shows the frequency table (T-scores) of the 100 most associated collocates for the whole corpus. Considering the first ten collocates—which next to “city” includes “energy,” “technology,” “development,” “data,” “infrastructure,” “management,” “public,” and “new”—the smart city is cast predominantly in terms of the management of data-enabled (energy) technology and related infrastructures. Enlarging the focus to the 100 most frequent collocates dilutes this perspective: on one hand, “mobility,” “water,” and “transport” now supplement the energy sector focus; on the other, significantly, the technology-infrastructure perspective is adjoined with governance-related (“government,” “project,” etc.), societal (“people,” “living,” etc.), and more marginally environmental (“green”) aspects, among others. Also notable is the significant presence of collocates denoting the “international” (“world,” “global,” “European,” etc.)

Next, each of the 100 collocates is assigned to one of 10 smart city dimensions (or otherwise labelled “unclassified”: See Appendix 1) derived from the literature as well as an initial scoping of the corpus. The related findings are shown in . Accordingly, across all 100 collocates, governance (10.1 percent) is the most dominant dimension, whereas environment (1.9 percent) and sustainability (0.9 percent) form the smallest categories. Interestingly, digital technology (8.3 percent) is not the most dominant dimension as might be expected; instead, governance leads, followed by infrastructure (9.5 percent) and international (8.9 percent).

The centrality of governance is further revealed by the qualitative concordance analysis.Footnote11 According to one main storyline, governance is a key focus of attention since “governance models remain in the 20th century … the smart city is so different in essence to the 20th century city that the governance models and organizational frameworks themselves must evolve” (Melbourne_1); and similarly, “systems are often siloed and not suitable for integration. This needs a whole new way of thinking” (Amsterdam_8). Governance reform, however, is not limited to government, but extends to collaboration across wider society. Hence, smart city innovation is “all contingent on participatory governance based on whole-of-society collaboration and open innovation” (Singapore_11), with reference elsewhere even to “the importance of ‘perpetual collaboration’” (Berlin_9).

A second, more “down-to-earth” storyline emphasizes the importance of governance for realizing optimization of existing structures and systems; e.g., “the smart city is to provide better management and planning of urban infrastructure” (Beijing_12). Here, governance closely relates to specific infrastructure concerns, such as “implementation of smart waste disposal and management measures” (Hong Kong_1), “promoting the concept of smart energy management” (Singapore_2), and “investment in intelligent traffic management systems” (Boston_7)—with mobility (including transport) receiving the most mentions across the entire corpus, followed by energy, water, and waste. The smart city, then, is seen as an opportunity to embark on fundamental infrastructure modernization activities, for which appropriate governance mechanisms are called for.

Digital technology is pivotal for smart innovation, e.g., “the definition of smart cities is still being defined today, but its essence entails a network of data-enabled, connected technologies … ” (San Jose_10). While this serves to consolidate various infrastructure technologies (as above), there is a correlated storyline which places digital technology more fundamentally (as an end in itself) at the heart of the city, e.g., “a smart and connected city is increasingly a system of systems, or a network of networks, where the networks are composed of nodes of communication” (New York_5), which “all connect us with the surrounding world and each other in a way never experienced before” (Copenhagen_1). However, this emphasis is again frequently moderated by storylines bringing the social, economic, and environmental dimensions to the fore. For example, one city defines its smart city engagement relating to its “community liaison role” thus: “a significant proportion of the smart cities work in Chicago lies at the boundary between government, the community, and private sector stakeholders” (Chicago_12). Elsewhere, Singapore states about its “smart nation” ambition: “there is a large potential to create economic value, but also to improve the living standards of citizens and create considerable social value” (Singapore_8).

Then again, some storylines foreground the smart city addressing global challenges relating to natural resource efficiency and environmental degradation. For example, one text argues that cities are

especially susceptible to the natural disasters and other long-term environmental concerns related to climate change. A smart city will understand its responsibility to adopt sustainable policies and make environmentally-friendly investments. (Los Angeles_16)

In summary, concerning the overall corpus, there is clear evidence of several specific storylines intermingling with one another, at times in a complementary and other times more contrasting fashion. The significance of the governance dimension, alongside that of infrastructure and digital technology, is particularly revealing. Furthermore, the prominence of the international dimension highlights the global as an integral element of the smart city. Social, economic, and environmental aspects are variously discursively mobilized to contextualize and justify the smart city, albeit often in a more ancillary manner.

The overall corpus can also be compared with individual city-specific corpora (See ). This reveals relatively self-similar profiles across the 27 cities, a further indication of the circulating, shared nature of current smart city discourse. (The corpus of Stockholm, SE, most closely resembles that of the overall corpus profile.) At the same time, some notable variations are apparent. For example, the corpora of Copenhagen (DK), Vancouver (CA), and Vienna (AT) have a more pronounced environmental component, in line with their reputation for sustainable urbanism. Concerning Delhi and Mumbai, the spatial planning/development dimension is elevated, which resonates with the area-based development focus of India’s Smart Cities Mission. For Los Angeles, Portland (OR), New York, and San José (all USA), the technology and infrastructure dimensions are to the fore, reflecting the focus of the Smart City Challenge of the US Department for Transportation and more generally the high standing of smart technology innovation (e.g., Silicon Valley). Finally, Amsterdam (NL), Barcelona (ES), and Paris (FR) have a more pronounced international profile, while the opposite is the case for Melbourne (AU), Mumbai (IN), San José (USA), and Portland (Oregon, USA), the latter scoring 0 percent. The overall quantitative picture, however, is one of considerable self-similarity across the 27 corpora.

Emergent Critical Junctures

This section reports the interpretive-qualitative results from Steps 2.2.1–2.2.2 (Box 1). Using the concordance tool—first, to further analyze individual collocates relating to each of the 10 dimensions in terms of their contextual appearances across the corpus; and, based on this, second, to identify and characterize transversal themes—not only helps develop a more fine-grained picture of individual smart city dimensions, but also reveals original insight into how various discourse strands interact to forge particular narratives about what is essential about the smart city and why it is instrumental for (future) urban development. In situating key interlocking discourses, the norms, motives, and justifications underpinning the smart city regime can be uncovered. At the same time, this helps reveal counter-narratives offering alternative interpretations. Consequently, five distinct, yet related critical junctures were identified through this in-depth qualitative analysis, as follows:

Socio-Technical Bifurcation

A central, as yet unresolved, question emerging from recent discourse concerns the foregrounding of the smart city as either an essentially technological or a primarily social endeavor. Insofar as the city encompasses both infrastructure and the public sphere, the technological and the social must be expected to intertwine in any definition of smart city. However, the discourse exhibits more than that—a struggle over pre-eminence. One report, by the European Commission, readily declares its hand, citing Amsterdam as a “good practice” exemplar:

Without the engagement of stakeholders, a city can never be Smart, no matter how much ICT shapes its data … The starting point of [Amsterdam Smart City] is not the (technical) solutions but the collaboration, co-creation, and partnering of stakeholders within the city of Amsterdam. (Amsterdam_17)

As expected, other perspectives espouse a more technological orientation closer to the roots of the smart city concept; e.g., “since the advent of ICT in the mid-1990s … [the] Smart City concept has been revealed as a city development concept that uses ICT as the foundation of initiatives and programs that facilitate social and economic activities within the city” (Seoul_7). Similarly, “the raison d’être of IoT-powered smart cities is improving the quality of life of citizens through a slew of technological solutions” (Mumbai_17). Yet another text explains that

there is no single global level accepted definition of a “Smart City”—but most rely on the use of technology and evidence to improve cities or city inhabitants’ services … Smart Governance is basically about using technology to facilitate and support better planning and decision making in the metropolitan or smart cities. (Vancouver_11).

Engaging the public and creating a sense of co-ownership over the challenges the country faces constitute the main challenges for Singapore. This is also a key component in the conceptual framework of Smart City, which is ultimately about exploiting ICT for transforming surpluses into resources, enhancing integration and multi-functionality of solutions, and improving mobility and connectedness to create better lives and a greener planet. Yet this is all contingent on participatory governance based on whole-of-society collaboration and open innovation. (Singapore_11)

Transformative Change versus Incremental Optimization

Another bifurcation concerns the change effected by smart cities: on one hand, change is posited as transformative, requiring “a whole new way of thinking—‘Smart City’ thinking” (Copenhagen_1); on the other, it implies a more incremental approach to improve urban service management. This difference may be partly explained by the discourse both projecting into the long-term future with bold visions and addressing immediate issues and practical applications in the present. This exposes an underlying tension about quite how fundamentally distinctive “smart” is.

The language of radical innovation and transformative governance enabled by disruptive technologies is deployed to create urgency for the adoption of smart urbanism. This may be rationalized referring to the inevitability of the “big data revolution:” as one text proclaims, “the emergence of ICT and big data has been a wakeup call for cities that the smart cities wave is coming” and “we are only on the cusp of the explosion of big data and the IoT … Some cities find themselves needing to ‘catch up’ to … the bottom-up revolution of disruptive technologies” (Boston_2). Relatedly, the demand for transformative change is rationalized referring to the outdatedness of conventional governance. As one report forcefully puts it,

cities are realtime systems, but rarely run as such. Governance models remain in the twentieth century … The implication here is that the smart city is so different in essence to the twentieth century city that the governance models and organizational frameworks themselves must evolve,

In contrast, the incremental change discourse serves to naturalize the smart city in a more immediately instrumental way: by demonstrating the practical applicability and related efficiency benefits of new technology to existing infrastructure systems and governance processes. Hence,

becoming a smart city starts with smart systems which work for the benefit of citizens and the environment. Electric grids, gas/heat/water distribution systems, public and private transportation systems, commercial buildings/hospitals/homes are the backbone of a city’s efficiency, livability, and sustainability. It is the improvement and the integration of these critical city systems that will make smart city [sic] become a reality. (Singapore_8)

A Place, Project, or Phase?

That the smart city deals with the urban goes without saying. Still, it can be difficult to discern where and how it intervenes and materializes. This is partly due to the innovation language used, such that “test,” “pilot,” “experiment,” “hub,” “laboratory,” “project,” “platform,” and similar metaphors serve as regular descriptors for smart city development.Footnote12 However, while invoking innovation is a common strategy to render the smart city novel and attractive, the resulting discourse can leave more questions unanswered. In particular, the spatial context of “platforms” and the scalability of “pilots” often remain unclear. “Test-bed” may well be a frequent discursive accompaniment, but in itself this says little about how and where the smart city becomes embedded in the urban fabric.

Owing to its technological origins and inflection, the smart city is regularly discussed in terms of “tests,” “pilots,” etc., to be run and evaluated, and “projects” and “phases” to be rolled out and managed. For example, “for ICT investment in Chicago, pilots are seen as a useful way to learn and test how to roll out a project at scale” (Chicago_12); and “the more advanced smart cities have taken the opportunity to test new business models in pilot projects, in order to assess scalability for full project implementation” (Shanghai_5). At times, such pilots and projects are defined in purely technological terms—e.g., “those projects mainly focus on the construction of network layers, such as physical network backbone, optical fiber, WIFI … ” (Barcelona_7)—while at other times this is cast in collaborative terms, e.g., “define pilots, with the main objective being to collaborate in the process of integration of municipal networks” (Stockholm_11).

Where spatial relationships are articulated, this raises the question whether the city as a whole, or specific places within it, act as “hub” for innovation. In China, whole cities are given the smart city treatment: “MOHURD [Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development] has announced 193 cities to be pilot cities as ‘Smart City’ by now” (Beijing_11). Similarly, “the pilot site Milan (Italy) aims to fully comprehend energy consumption across the city … ” (Barcelona_17); and, describing Barcelona’s smart city strategy, “one key element is the so-called ‘Smart City Campus,’ which is meant to: transform the city into an experimentation and innovation laboratory … ” (Barcelona_17). Elsewhere, the smart city is associated with named districts, e.g., “use Kowloon East as a pilot area to explore the feasibility of developing a Smart City” (Hong Kong_5); and “the Columbia Corridor and Powell/Division Corridor will be design labs for specific infrastructure implementation as well as for baselining, monitoring and reporting … ” (Portland_1). Here at least, more concrete spatial and material connections are created.

A further layer of complexity arises from the scalability of projects.Footnote13 It is often implied uncritically that initiatives can readily be replicated elsewhere: “the city then runs pilot projects to test the theories and optimize the engineering. Once the system is perfected, the pilot is up-scaled to the whole city” (Dubai_9). On a larger scale still, one report boasts: “from Smart Cities to a Smarter Europe: replication, scaling, and ecosystem seeding” (Barcelona_17). More tempered, realistic views exist though, too, e.g.,

cities must be able to successfully bring projects from pilot to the city-wide scale in order to build long-term solutions. The ability to transition from pilot tests to larger scale is distinctly absent globally. (New York_16)

Private–Public Partnership

Yet another tension becomes apparent between public and private interests driving the smart city. On one hand, the public (interest) is claimed to be a key motivation for, as well as main beneficiary of, smart city innovation; on the other, it is predominantly cast in terms of the logic of the private sector and, as such, arguably serves as an extension of it.

The pre-eminence of the market rationale manifests itself in two ways: first, repeated mention is made of the smart city’s sizeable market potential: e.g., “Arup estimates that the global market for smart urban systems for transport, energy, healthcare, water, and waste will amount to around $400 Billion p.a. by 2020” (London_10); and “the [smart water] market will be in excess of $22.2 billion by 2020, four times greater than its present value” (London_2). In other words, the smart city is there for the taking by business vying for a share in this eagerly anticipated growth sector. Second, more profoundly, the smart city is presented as a platform for economic renewal through cutting-edge innovation; e.g., “these markets also need the right conditions to emerge: a new innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem where stakeholders interact effectively and where new business models and ways of working can be created so that new technologies can be adapted” (London_6). Hence, “Smart City projects can be used to propel economic development of a region, which is what the city of Nice, France sought to do” (Barcelona_12); and similarly, “Busan in South Korea and Helsinki in Finland are beginning to use smart city projects … to provide innovative new services, driving economic growth and making the city’s businesses more competitive” (Seoul_6).

Within this strong market orientation, the public (with sister terms “people,” “citizens,” “social,” etc.) prominently features as a corresponding reference point. Indeed, in terms of frequency count (See Appendix 1), the “public” is among the top 10 collocates of “smart” followed by “people” (no 22), with “business” (26) and “economy” (43) further down the list. Seoul illustrates the eager embrace of the public (and it is worth noting the difference to Seoul_6 above). Reflecting on the technology-centric approach of its earlier smart city initiative (“u-Seoul”), the city more recently declared that: “Smart Seoul 2015 is a more people-oriented or human-centric project; and Seoul now aims to implement as many smart city technologies as possible, but also to create a more collaborative relationship between the city and its citizens” (Seoul_1).

While, then, the public is keenly mobilized, the overarching market-oriented discourse nevertheless means that the characterization of the public tends to be skewed in three particular ways: first, the private sector is posited as template to be emulated by both citizens and public authorities, thus underlining the primacy of the market:

As consumers of private goods and services, we have been empowered by the Web and, as citizens, we expect the same quality from our public services. In turn, public authorities are seeking to reduce costs and raise performance by adopting similar approaches in the delivery of public services. (Barcelona_20)

Moreover, third, the issues to be engaged in—health, education, work, etc.—are predominantly discussed in terms of enabling members of the public to be economically active and become entrepreneurially successful. For example, “Birmingham’s smart city ambition is to become the agile city where enterprise and social collaboration thrive—helping people to live, learn, and work better by using leading technology” (London_7). What is conspicuous by its absence in this three-fold articulation of the public is any real sense of collectivity, shared public discourse and active citizenship. Rather, public agency is mainly understood and exercised through entrepreneurial governance, such that: “cities … are developing new approaches to community involvement with an emphasis on the co-creation of services and on digital inclusion programs for residents and small businesses” (London_7).

Smart and Sustainable?

If “smart” is sometimes called “the new sustainable” (see introduction), this draws attention to another key juncture. Certainly, concluding from this study, smart does not straightforwardly equal sustainable. In quantitative terms alone, the findings of the co-occurrence analysis confirm that “environment” (1.9 percent) and “sustainability” (0.9 percent) are small compared with “governance,” “infrastructure,” and “digital technology.” This suggests that the environment is afforded a rather more marginal role in the smart city than one would expect from comparable sustainable city concepts and initiatives.

Nevertheless, in a few notable cases, the “environment” and “sustainability” categories are more prominent—especially Vancouver (5.3 percent, combined), Copenhagen (4.1 percent), and Vienna (3.9 percent)—with an explicit “green” agenda folded into the smart city mix. Thus,

Smart City Vienna … promote[s] the development of a city which is based on sustainability and the protection of resources. Through three key strategies—a vision of a sustainable future for Vienna in 2050, a roadmap for energy- efficient and climate-friendly urban development up to 2020 and an action plan for 2012–2015––Smart City Vienna has developed a concept which provides a vision for the city’s future. (Vienna_20)

[Copenhagen] has an ambitious green vision and is a perfect setting for a green laboratory. The projects in and around Copenhagen will serve as best practices bringing greater efficiency, cost savings, and sustainability that other cities in the world can reproduce. (Copenhagen_9)

Frequently, “sustainable,” “environmental,” and similar adjectives are used across the corpus as generic descriptors, to denote “good” urban development. This may well reflect the by now established status of (environmental) sustainability in urban policy which, therefore, does not require spelling out in detail. More pessimistically, it may reflect a tokenistic approach, whereby lip service is paid to environmental responsibility as part of the smart city’s sale’s pitch. Here again, however, such generic use is at times complemented with more specific descriptions, indicative of the pursuit of particular environmental ambitions and targets; e.g., “Bornholm’s vision is to become a 100 percent sustainable and carbon-free community by 2025” (Copenhagen_18), and

The smart city is being built with the objective of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 70 percent and decreasing water consumption by 30 percent. The smart city will meet over 30 percent of its energy needs through renewable energy sources, with energy savings for up to 100 years. (Seoul_20)

One of the greatest challenges facing the world today is climate change combined with a drastic reduction in the earth’s natural resources, especially fossil fuels … Answers will have to be found in the form of smart technologies, systems, and concepts. (Vienna_11)

This particular approach to (environmental) sustainability is reinforced by an overarching ecological modernization narrative at work (see above), which subsumes environmental and sustainability issues within an economic growth discourse. Thus, “[the smart city] advocates suggest the use of information technology to meet urban challenges in the new global economy“ (Boston_7); and “by testing these solutions, the city hopes to attract innovative companies, which will in turn support the economy through the process of becoming greener and smarter” (Vienna_20). Evidently, then, the smart city does strive for sustainability, but the particular approach pursued may well end up casting important environmental and other sustainability concerns aside.

Discussion: Two Key Observations

From its inception, the smart city has often struggled for definitional clarity and practical import, prompting Hollands (Citation2008: 304) to ask “will the real smart city please stand up?” and more recently Shelton et al. (Citation2015: 13) to inquire into “the ‘actually existing smart city.’” These and other writings highlight apparent conceptual fuzziness (“the smart city, a somewhat nebulous idea”: Shelton et al. Citation2015: 13), and the predilection for totemic “clean-slate” projects (e.g., Masdar, Songdo). Together, this suggests a “disjuncture between image and reality” (Hollands Citation2008: 305) and a remoteness from grounded practice within “ordinary” cities. Consequently, analysts are urged to turn their attention to locating and scrutinizing “real” smart cities.

This study seeks to contribute to this ongoing endeavor, by identifying and interrogating recent smart city discourses associated with cities from around the world. In pursuing this approach, the study understands discourse to be an essential element of the smart city, integral to its social practice. Furthermore, it understands discourse to be networked, dynamically adapting global discourse into particular geographical, cultural, and institutional settings while feeding global discourse with local (complimentary or contestatory) variations. This approach does not negate the need for research into the situated, material smart city practice. Rather, it emphasizes that the smart city’s materiality exists in close relationship with its discourse, and its local grounding in close relationship with its global circulation. As such, the smart city as powerful discourse regime merits critical analysis.

The findings of this research, obtained through a systematic webometric exercise combined with detailed textual analysis of smart city discourses related to cities worldwide, prompt two main observations.

Globalizing Smart City

The first concerns the smart city’s close conceptual alignment with a pronounced global narrative. Repeated mention is made in the texts of “global best practice” led by “advanced cities,” which thereby act as “models to others” (e.g., New York_5). Time and again, the same or similar groups of world cities are posited at the vanguard of smart city innovation. Occasionally, talk is of “lighthouse cities” to be emulated by “follower cities.” Altogether, this narrative suggests that world or capital city status de facto confers model and best practice standing. What, notably, this narrative fails to articulate is whether such presumed model status is necessarily justified on substantive ground and, moreover, how to account for likely differences between acclaimed smart cities. In short, in the search for the paradigmatic smart city, global or world city status appears to play an overriding factor, trumping other considerations.

The significance of the global narrative extends further still. Not only are major cities touted as models to be emulated by others, but the smart city—urbi et orbi—is even more ambitiously posited as the hub for global smart society. The city thus acts as “test site” for experimenting in smart innovations with a view well beyond the city itself. As one report puts it: “from smarter cities to a smarter Europe: replication, scaling, and ecosystem seeding” (Barcelona_17). Insofar as the smart city, then, is about lifestyles, knowledge production, and markets, and insofar as the emphasis is on up-scaling and international circulation and even “global responsibility”, it is not surprising that there is an inherent tension between the smart city’s local, material grounding and its expansive, global reach.

It is, furthermore, no coincidence that the 27 cities identified here form the core of the global discourse network. As (mostly) capital and world cities, backed by national governments and promoted by international organizations and business, they have evidently seized the opportunity to place themselves at the heart of the evolving smart city agenda, using it concurrently to promote urban renewal to their domestic audiences and to signal their global ambitions to foreign audiences, and in doing so frequently engaging in mutual cross-referencing. Needless to say, the smart city discourse is not limited to these 27 cities: there are significant discourses around many more cities (albeit with URL scores of <2,500 as measured in this study); and different methodological configurations (e.g., other language settings, or discourse genres) would likely produce some variations. It is important, therefore, that the discourse captured here is not taken to represent its entirety. Still, given that English acts as lingua franca and a well-established search engine was used, it is safe to say that the 27 cities and their associated texts are central to the smart city global discourse network: what they have to say matters.

Transformative Governance In and Beyond the City

The second observation concerns the nature of the discourse regime revealed. The question arises whether the multiple dimensions and critical junctures identified here amount to anything like a coalescing discourse regime, or rather display signs of an incoherent, self-contradictory discourse at work. While the latter may be more tempting to conclude,Footnote14 it is the former which deserves closer consideration. Some commentators have suggested that the smart city has transitioned from a mainly technology-focused to a more socially-oriented stage. Accordingly, the smart city is no longer predominantly driven by corporate interests on the lookout for new uses for technology, but rather guided by social concerns and the public interest for which appropriate technology is mobilized. At least, this is implied in such calls as “rethinking smart cities from the ground up” (Saunders and Baeck, Citation2015) and “cities for citizens; citizens changing cities” (the 2016 strapline of the Smart City Expo World Congress website: SCEWC, n.d.).

In contrast, this study exposes a more complex shift in discourse regime. For one thing, rather than a chronological transition from one stage to another, the findings show a persistent socio-technical bifurcation, with some texts (even recent ones) insisting on “a slew of technological solutions” (e.g., Mumbai_17) while others alternatively counselling a socially driven approach. For another, where a shift is advocated, this cannot be taken simplistically to mean a more socially conscious smart city. Rather, more problematically, it entails calls for a disruptive (seen as positive) change of society: references to outmoded twentieth-century governance models, the need for fundamental transformation, even a whole new way of thinking etc., together make clear the smart city’s ambition to reach profoundly into the social realm. Herein lies the significance of the emergent discourse regime. As a consequence, however, the discourse becomes more multifaceted, as it concurrently engages in multiple domains. In turn, this exposes several fault lines, laying bare tensions and contradictions as the smart city seeks to reconcile differing ambitions.

Together, the two overarching observations point to the smart city discourse presently being in flux, engaged in continuous boundary-work, and evidently struggling on several fronts for clear perspectives. This is in no small part due to the scope of the smart city expanding considerably, from a preoccupation with urban infrastructure and service issues to a far-reaching, transformative social governance project. In turn, this significantly extends the reach (both geographical and conceptual) of the smart city beyond the city itself. And while this is increasingly driven by, and happening in, “actually existing” cities, it is not surprising that the resulting discourse frequently remains elusive and difficult to pin down in local, material form and practice. That, though, does not make it any less relevant.

Conclusions: Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

This study has sought to answer three main questions concerning: (1) the prevalence of smart city discourse among cities worldwide; (2) the key dimensions characterizing recent discourse; and (3) the presence and significance of critical junctures. The analysis reveals an expansive discourse network involving 27 mostly capital or world cities in Asia, Europe, and North America. The overall text corpus shows the smart city consisting of multiple dimensions beyond an infrastructure-technology focus. Governance in particular acts as centralizing theme. The texts, too, display a strong international narrative, which reinforces the smart city as globalizing activity. In contrast, the environmental dimension is much less pronounced, calling into question whether smart is the new sustainable. Across the 27 cities, the texts are largely similar in terms of the composition of the various dimensions, suggesting cross-fertilization and considerable commonality. The further qualitative analysis highlights the presence of several critical junctures—key thematic areas characterized by ongoing boundary-work and, consequently, harboring unresolved tensions. These show that, despite reference to global models and best practice epitomized by advanced world cities, smart city discourse currently presents a multifaceted picture in trying to forge a new discourse regime centered upon transformative governance.

The findings have prompted two key observations. One, regarding the distinctly global character of the smart city, and, the other, regarding the transformative governance agenda that the smart city represents. These observations point to several directions for future research, policy, and practice.

First, concerning the smart city centrally defined in terms of global engagement, this invites research questions about the effects of the competitive dynamics created between world cities posited as “model” smart cities and various second- and third-tier “follower” cities. At the same time, within individual cities, the internal dynamics resulting from the concurrent discursive engagement with the smart city as a global undertaking and local practice merits closer analysis, for example how this is addressed by and calibrated with strategic planning. These same questions have implications for policy and practice, too: for one thing, the abstract notion of “global best practice” should be considered with caution, since this could problematically assume the ready applicability of generic models while neglecting or even negating the need for locally grounded approaches to smart city innovation. For another, nurturing a quasi-competitive environment in which implicitly “lesser” towns and cities are nudged if not compelled to follow superior “lighthouse” cities may risk creating counterproductive hierarchies through which external practices are elevated and home-grown approaches downplayed. Consequently, policies and practices promoting the globalizing smart city should be tempered with due emphasis placed on local relevance and resonance.

Second, concerning the smart city advocated as a fundamentally transformative governance project that goes beyond improving the efficiency and coordination of existing urban infrastructure systems and organizational processes, this invites additional follow-up questions. While the elaborate webometric exercise combined with systematic textual analysis across a large corpus, as carried out in this study, is a powerful tool for critically interrogating the “discourse regime” forming around the smart city, there is scope for expanding this research. For example, the emerging discourse regime could be further examined beyond textual sources, by looking at visual representations as well as the scripting and staging of events (e.g., Gamson and Modigliani, Citation1989; Hajer, Citation2009; Easterling, Citation2014). Moreover, research could probe more deeply into how discursive narratives and storylines are deployed by, and exert influence on, various smart city “discourse coalitions” (Hajer, Citation1995), as a means of revealing what interests and politics are at work in particular networks of actors.

Concerning the politics in play, it also is important to acknowledge and scrutinize the inherent normativity of representing the smart city as an agent of transformation. The underlying assumptions about the obsoleteness of existing governance modes, and the virtue of “disruptive” innovation, need careful examination and warrant more open discussion. Here, the five junctures provide useful openings, since they lay bare some of the underlying issues and challenges involved. It would seem essential that related policy and practice work not be confined to “back office” environments—where typically the smart city has been fashioned by various technical experts and professionals—but involve a broader set of actors and extend to the wider public sphere. If, as has been suggested, all towns and cities are seemingly on the path to becoming “smart” (e.g., Karvonen et al., Citation2018: 1), and if this entails (beyond incremental, technical upgrades) potentially profound socio-political transformations, then this deserves full and critical attention as part of wider public discourse. Finally, following McFarlane and Söderström (Citation2017), apart from offering up constructive critique, such broader engagement should essentially also include the possibility of forging alternative ways of thinking about, and putting into practice, the smart city.

Data Access Statement

The research data supporting this publication are openly available from the lead author's Research Gate profile at: <https://www.researchgate./net/profile/Simon_Joss>

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank colleagues on the research project “Smart Eco-Cities for a Green Economy: A Comparative Study of Europe and China” for their methodological input in the early stages of this study. We are grateful to the reviewers for their detailed feedback on the paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on Contributors

Simon Joss is professor of urban futures in the School of Social and Political Sciences (Urban Studies), University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

Frans Sengers is postdoctoral researcher in the Innovation Sciences section of the Copernicus Institute, Utrecht University, Utrecht, NL.

Daan Schraven is assistant professor in economics of civil infrastructures in the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, TU Delft, Delft, NL.

Federico Caprotti is associate professor in human geography in the Department of Geography, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK.

Youri Dayot graduated with a Master's degree (1st year) in Comparative Politics from Sciences Po Grenoble, Grenoble, Fr.

ORCID

Simon Joss http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2856-4695

Daan Schraven http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0647-1172

Federico Caprotti http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5280-1016

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This approach understands discourse as distinct from institutions, in contrast to e.g., Laclau and Mouffe (1985) (cited in Atkinson et al., Citation2010), who argue that there is no distinction between the discursive and non-discursive. Furthermore, for pragmatic reasons, the present approach is focused on the texts themselves (as networks of storylines). A discourse coalition approach (e.g., Hajer, Citation1995), focusing on networks of actors (and their storylines) could be useful for follow-up research.

2. “Los Angeles_16” refers to the PDF document found, through the online search process, in position 16 out of the first 20 PDF files for the city of Los Angeles (USA). N.B. This, therefore, does not necessarily mean that the document is published by the city authorities themselves; its origin may be a third party discussing the city as exemplar of smart city. See also footnote 7. Henceforth, the same nomenclature is used for all cited documents from the collated text corpus (346 files). For full references, see .

3. According to Trencher and Karvonen (Citation2017: 1), “the current smart city agenda has embraced th[e] ecological modernization approach to urban development,” explained as “the simultaneous pursuit of economic development and environmental protection.” See also Hajer and Dassen (Citation2014); and for a wider discussion of ecological modernization, e.g., Mol (Citation2001).

4. The logic here refers to how the global discourse network is identified and captured. A search engine reveals texts in predefined digital format that contains the key content for which texts are generated and circulated over the Web. As such, the search engine “infiltrates” the virtual space in which the global discourse is readily exposed to any contributor. It can, therefore, be considered a methodologically suitable tool for collecting texts in circulation.

5. As the overall range in URL scores was found to be 0-10,700, the selected range of 2,500-10,700 represents the top, upper-middle, and lower-middle quartiles of measurement. Apart from pragmatic reasons (manageability of data), the chosen range is appropriate methodologically, as the cities in this range have a larger exposure to the global discourse in both size and visibility, which in turn helps identify core narratives and critical junctures of the discourse.

6. A PDF document is considered valid if its contents explicitly—though not necessarily exclusively (e.g., in the case of comparative case studies)—relate to the corresponding city and related smart city activity. Furthermore, it is considered valid if authored either directly by city authorities (or smart city project initiators) or by third parties (including international organizations. Documents clearly not dealing with smart city per se (e.g., “smart holidays”) are excluded from the corpus.

7. Within the category of “smart city,” the term “smart” has multiple linguistic uses, including, e.g., “smart governance,” “smart mobility,” “smart grid.” Hence, to fully capture the various dimensions, “smart” is used as node (rather than “smart city”). Twenty words is the maximum window setting in AntConc, and is recommended for enlarged textual analysis (rather than more narrow semantic examinations). So-called “stopwords” (“the,” “that,” “of,” “and,” etc.) are automatically excluded.

8. The T-score (or T-value) is used to establish the statistical likelihood of association between a collocate and a node. Hence, the higher the T-score, the greater the likelihood of co-location. The literature recommends T-score over the alternative MI-score, given the small overall text corpus. The T-value measurement includes a built-in statistical adjustment, whereby if a given collocate (within the window; here 41 words) has a proportionally high frequency outside the window then a measured downward adjustment is made. (See Stubbs, Citation2007; Anthony, Citation2016).

9. The dimensions were derived, on one hand, from the literature (e.g., de Jong et al., Citation2015: section 4.4; Caragliu et al., Citation2011; Giffinger and Gudrun, Citation2010; Lee et al., Citation2013) and, on the other, from previous research on smart cities by the authors. The dimension “international” was added following initial textual analysis, which indicated an explicit presence of international terms.

10. For example, for the collocate “stakeholder,” all 1,433 instances of its in-text occurrence are comparatively shown, from which a qualitative picture can be developed of the particular meanings and significance of “stakeholder” and how, in turn, this informs the discussion of smart city.

11. These findings resonate with a growing discussion of the significance of governance in the literature. See for example the four perspectives on smart governance in Meijer and Bolivar (2015).

12. The notion of experiment is increasingly recognized in the literature. See in particular the conceptualization of “the experimental city” by Evans et al (Citation2016); also Scholl and Kemp (Citation2016), Caprotti and Cowley (Citation2017), and Raven et al. (Citation2017)

13. For a recent extended discussion, including a typology of scaling, relating to smart city pilot projects, see van Winden and van den Buuse (Citation2017).

14. It is worth noting that in their bibliometric analysis of scholarly literature (which, however as noted in the above introduction section, differs from the present webometric analysis), Mora et al. (Citation2017: 3) indeed conclude that smart city research is currently fragmented and lacks cohesion.

References

- S. Allwinkle and P Cruickshank, “Creating Smart-er Cities: An Overview,” Journal of Urban Technology 18: 2 (2011) 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2011.601103

- T. Almind and P. Ingwersen, “Informetric Analyses on the World Wide Web: Methodological Approaches to ‘Webometrics,’” Journal of Documentation 53: 4 (1997) 404–426. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000007205

- M. Angelidou, “Smart Cities: A Conjuncture of Four Forces,” Cities 47 (2015) 95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2015.05.004

- L. Anthony, AntConc (Version 3.4.4) [Windows] (Tokyo: Waseda University, 2016). <http://laurenceanthony.net/> Accessed August 1, 2016.

- R. Atkinson, G. Held, and S. Jeffares, “Theories of Discourse and Narrative: What Do They Mean for Governance and Policy?” in R. Atkinson, G. Terizakis, and K. Zimmermann, eds, Sustainability in European Environmental Policy: Challenges of Governance and Knowledge (London: Routledge, 2010) 115–130.

- T. Baker and C. Temenos, “Urban Policy Mobilities Research: Introduction to a Debate,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39: 4 (2015) 824–827. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12252

- I. Calzada and C. Cobo, “Unplugging: Deconstructing the Smart City,” Journal of Urban Technology, 22: 1 (2015) 23–43. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2014.971535

- F. Caprotti and R. Cowley, “Interrogating Urban Experiments,” Urban Geography 38: 9 (2017) 1441–1450. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2016.1265870

- A. Caragliu, C. Del Bo, and P. Nijkamp, “Smart Cities in Europe,” Journal of Urban Technology 18: 2 (2011) 65–82. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2011.601117

- A. Caragliu, C. Del Bo, and P. Nijkamp, “Smart Cities in Europe,” in M. Deakin, ed., Smart Cities: Governing, Modelling and Analyzing the Transition (London: Routledge, 2014) 173–195.