Abstract

Good advertising is not enough anymore. With technological and societal progress, savvy consumers, and new media revenue models, advertising needs to be truly good to serve a purpose and to be allowed to live on. In this paper, I outline how truly good advertising (TGA) does not only produce equity for the advertiser, but also generates advertising equity to the benefit of the consumer, adds value to the media context and has a positive impact on society.

Let’s not talk about good advertising anymore. It’s been talked about for centuries already, and written about since at least 1896, when Charles Austin Bates (Citation1896) published his book “Good Advertising: And Where it is Made” (which was the earliest publication I found when I googled). Google Scholar produced nearly 8,000 texts that discuss “good advertising,” within a diversity of fields ranging from economics (e.g., Becker and Murphy Citation1993), finance (e.g., Abayi and Khoshtinat Citation2016), strategic management (e.g., Mason and Belt Citation1986), innovation and technology (e.g., Cooper and Kleinschmidt Citation1994), journalism and mass communication (e.g., Otnes, Spooner, and Treise Citation1993), and public policy (e.g., Boddewyn Citation1985), to, of course, advertising research (e.g., O’Connor et al. Citation2018).

Still, with all this talk and study of good advertising and how it is made, advertising does not seem to be doing well. In fact, it seems to be dying. Advertising’s impending death has been proclaimed repeatedly in recent years. The New York Times anticipates that advertising will die, because consumers don’t need it (Kuntz Citation2009) and even hate it (Hsu Citation2019). So do, for example, Fast Company, because consumers can avoid it (Cassano Citation2013), The Guardian, because increasingly aware consumers are changing the rules of the game (Prest Citation2012), and CNBC, because the new media don’t want it (CNBC Citation2016). Scholars have argued for similar reasons that advertising as we know it cannot survive (e.g., Rust Citation2016; Schultz Citation2016; Stewart Citation2016).

What this all means, I would like to argue, is not necessarily that advertising is not good enough. It is rather that good advertising is not enough.

Good advertising is not enough

Browsing through the texts since 1896, I find that not much seems to have changed from Bates’s definition of good advertising as being advertising that sells products. Bates gives advice on how to use pictures, layout, copywriting, and tonality to make people want to buy the advertised products, and more than 120 years later, the texts on good advertising are still preoccupied mainly with how advertising spending, design, placement, and formatting can increase the advertiser’s financial wealth directly or indirectly. In our content analysis of recent years’ advertising research, we found that about 80 percent of all studies focused on effectiveness, in terms of increasing consumers’ liking and buying of the advertised offers (Dahlen and Rosengren Citation2016).

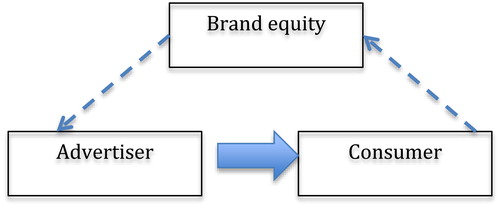

Throughout the years, the purpose and activity of advertising have been explicitly and consistently defined as persuading receivers to buy or do something, from Daniel Starch’s (1923)” selling in print” to Richards and Curran’s (2002)” paid, mediated form of communication from an identifiable source, designed to persuade the receiver to take some action, now or in the future”. Good advertising, thus, is advertising that sells and persuades as much as possible. I illustrate this view in , where the advertiser 1) pushes advertising on consumers in order to persuade them 2) to buy or do something (these various actions, now or in the future, are typically summarized by researchers as increases in the brand’s equity).

The problem with good advertising, as can be seen in , is that it is clearly one-sided, to the benefit of the advertiser. Legendary advertising executive Philip Dusenberry summarized it well in his famous quote,” I have always believed that writing advertisements is the second most profitable form of writing. The first, of course, is ransom notes.” In essence, good advertising is similar to a hostage situation, in which brands kidnap consumers’ attention in an effort to persuade them into opening their wallets.

But, of course, nobody likes being taken hostage. As concluded by Mark Ritson (Citation2015),” There is no prescribed moment when ad avoidance actually began, but we can probably assume it started about 20 minutes after the invention of advertising.” While the study of ad avoidance does not date back that far, it has indeed been subject to a large body of research. A seminal article, focusing on consumer perceptions of advertising clutter in various mass media, was published in this journal by Speck and Elliott in 1997. That marked the time pretty well when 1) advertising had increased its reach to pretty much include anyone, anywhere, and 2) technology increasingly enabled consumers to zap away from it in various ways.

Ever since then, advertising has been a cat-and-mouse game, where advertisers device new means of reaching consumers, and consumers find new ways of avoiding these ads. My own first advertising research publication, for instance, studied click-through rates for banner ads, which were novel and rather effective at the time (Dahlen Citation2001), but since then, a majority of consumers have started using ad blockers that automatically avoid them (53 percent of consumers in AdWeek’s 2015 survey). These ad blockers have led advertisers to device, for example, pre-roll ads on youtube, which, in turn produce new consumer avoidance behaviors (e.g., Goodrich, Schiller, and Galletta Citation2015).

Good advertising seems to be more or less an anomaly, something that works for a short period of time before consumers find new ways to avoid it (which they do at an increasing pace) or before it is called out in a cat-and-mouse-and-watchdog game where advertisers invent new formats, such as sponsored content and native advertising, which fly under the radar before either consumers recognize them as advertising or they eventually give rise to new regulations that force advertisers to identify themselves as such. Not surprisingly, there is a growing body of literature on advertising literacy (e.g., Hudders et al. Citation2017) and disclosures (e.g., Evans et al. Citation2017).

In all fairness, good advertising has never been solely a matter of finding more forceful or “deceitful” means of kidnaping consumers’ attention. Dating back to the creative revolution in the 1960s, and even Bates’s century-old advice on the use of color and copy, advertisers have been preoccupied with finding ways to attract attention as well (this has also been the focus of the majority of research). To my mind, this could be contrived as sugar-coating, where good advertising literally tastes good, but still serves to have consumers swallow the pill—that is, persuade consumers to buy or do something to the benefit of the advertiser.

Consequently, consumers associate advertising with persuasive attempts and frequently view it with skepticism and negative attitudes, which discount and counteract its intentions. Indeed, persuasion knowledge (Friestad and Wright Citation1995), ad skepticism (Obermiller and Spangenberg Citation1998) and attitudes toward advertising (Muehling Citation1987) are central concepts in the advertising literature, and new ones, such as offense (Dahlen et al. Citation2013) and insult (Dahlen, Rosengren and Smit Citation2014), are adding.

What this all boils down to in the end, is that good advertising is dying because it is not enough. No matter how clever it gets, it remains a hostage situation, which consumers have become savvy, technologically equipped and fed-up enough to resist. It’s time to talk about truly good advertising.

What is truly good advertising?

I propose that, in order for advertising to survive, it needs to be good not only for the advertiser, but also for consumers. That is, consumers need to gain something in return from taking part of the advertising.

By this gain, I do not mean that advertising helps consumers buy better products and make better decisions in some sense. These classic arguments, that advertising weeds out the bad products from the market (because in the long run, brands will not afford to advertise them, e.g., Milgrom and Roberts Citation1986), allows brands to produce higher quality and cheaper products (because advertising increases demand and produces economies of scale, e.g., Spence Citation1980), or helps consumers make more informed choices (because advertising informs them of the available options, e.g., Porter Citation1976), are all just fortunate byproducts of good advertising, which still serve the advertiser’s aim to sell. Obviously, these byproducts are not enough.

Instead, advertising needs to be truly good, in the sense that it is good in and of itself. Truly good advertising (TGA) gives something to consumers whether the advertiser’s aim to sell is fulfilled or not.

TGA is good for the consumer

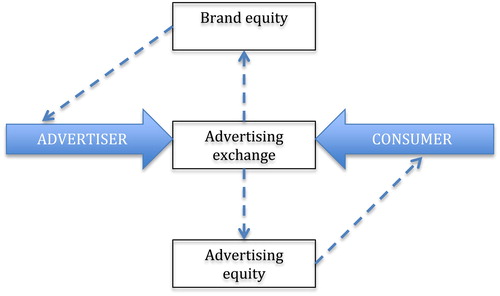

The idea that advertising can benefit consumers regardless whether it benefits the advertiser is illustrated in . While the advertiser still benefits in terms of brand equity, adds advertising equity as a benefit that consumers receive independently of what happens with the brand’s equity. We have proven in a series of experiments and tests that consumers can indeed derive equity from advertising, and that this advertising equity is a unique construct that is separate and independent from brand equity (Rosengren and Dahlen Citation2015).

The notion that consumers can derive value from advertising itself, typically because they find it entertaining, is not new. Robert Ducoffe published a highly cited article about consumer-perceived advertising values more than 20 years ago (Ducoffe Citation1995), and advertisers and scholars have always kept a keen eye on consumers’ liking of the ads. However, stuck in the paradigm of good advertising, they have always considered any value and liking for the advertising that does not translate into brand equity as dead-weight, because it does not benefit the advertiser (Rosengren and Dahlen Citation2015).

While advertising equity does not make consumers more prone to buy or do something, it does something that is absolutely vital for advertising to survive: it counteracts ad avoidance, and even stimulates approach behaviors. We found that our measure of advertising equity (which gauges the consumer’s perceived value and benefit of taking part of the ad itself) could predict the likelihood that a consumer would take part of the brand’s advertising the next time s/he encountered it, or even to voluntarily seek out more advertising from the brand, for example on youtube and in social media.

TGA frees consumers from the hostage situation that puts advertising at the risk of dying, by producing something that they want to take part of rather than is forced on them. It recognizes that consumers are no longer passive receivers of advertising, they are savvy enough and have the technology to actively choose whether they want to take part of and seek out the advertising themselves. This is also illustrated in , where both the advertiser and the consumer have been updated from entities (boxes) to forces (arrows) who can more or less keenly approach the advertising exchange.

In the advertising exchange, the advertiser needs to earn the consumer’s attention. Earning the consumer’s attention is a very popular saying, but we had never seen it put to the test, so we conducted two experiments to do so (Szugalski, Bergkvist and Dahlen Citation2014). In a first experiment, we found that when the advertiser put greater effort into the advertising (we manipulated it in terms of expense or creativity), consumers were more willing to attend to it. Correspondingly, we found in a second experiment, that when consumers put greater effort into attending to the advertising or even seek it out, they demanded more effort from the advertiser in return.

When measuring the consumer’s perceptions of both the advertiser’s and their own efforts, it became clear that consumers were indeed aware of their own efforts, and that they considered it a form of equity that they could choose to share or not. Consumers were also aware of the advertiser’s effort, and expected the advertiser to make a significant effort to their benefit in exchange for their own efforts. If they did not perceive that the advertiser put enough effort into rewarding them for their time and attention, they chose to discontinue the exchange, meaning that they stopped attending to the advertising and were not willing to receive or seek out advertising from the advertiser again.

Again, the consumers’ exchange behaviors were based on the advertising in and of itself, regardless of the brand and the touted product, and their interest in buying or doing something. Buying or doing something comes next, but TGA makes sure that it even gets to that stage. If consumers choose not to attend to the advertising, it doesn’t matter how good it is at selling and persuading.

TGA is good for the consumer in and of itself, because it needs to be. When consumers can choose whether to take part of advertising or not, and become increasingly aware of the value of their efforts to the advertisers, they will not settle for less. The good news is that when the advertising is truly good in this sense, consumers do indeed take part of it. We found this in our experiments, and there are plenty of real-life examples, such as the Super Bowl ads that have people seated in front of their TV-sets to purposely watch the commercial breaks, the viral commercials that consumers seek out on youtube, and the branded accounts that they follow on social media such as facebook and instagram. However, while these have historically been considered something out of the ordinary, they will need to be the norm in the future.

Truly good advertising is good for the media

TGA could be applied to media as well. If the consumer’s relationship to advertising resembled a hostage situation, then the media’s relationship to advertising could be likened to prostitution. Please forgive the vulgar allegory, but I find it rather accurate, in the sense that advertisers have had to pay the media to do something (feature ads) that they would not voluntarily do. From the media’s perspective, advertising is clutter that annoys, interrupts and distracts from the content (e.g., Speck and Elliott Citation1997) and should be kept to a minimum only to generate revenue, so as to not drive the audience away (e.g., Ha and Litman Citation1997).

As technology brings production and distribution costs down, however, the media become less dependent on advertising to cover expenses. Coupled with consumers’ willingness to pay a little extra for not having to be annoyed, distracted and interrupted, the media can remove advertising money out of the equation altogether. We are seeing this happen already, with commercial-free radio (e.g., Spotify) and TV (e.g., Netflix). This is also one reason why promoting advertising approach in own media is becoming increasingly important for advertisers.

However, advertisers will never be able to rely solely on consumers to seek out their advertising. There simply isn’t enough time in the day for it, nor interest from consumers to seek out advertising for all brands that wish to come in contact with them. Therefore, advertisers need the media to feature their advertising. But when money is taken out of the equation, the advertising will need to be good for the media in and of itself in order to be featured.

TGA enhances the audience’s perceived value of the media in which it is featured. My first notion of this was the experiments we conducted on creative media choice (Dahlen, Granlund, and Grenros Citation2009) and ambient media (Rosengren, Modig, and Dahlen Citation2015), where we found that entertaining and engaging advertising that somehow connected with the context actually increased consumers’ liking and perceived value of the context itself (e.g., waiting by the airport conveyor belt, riding the elevator, or pushing a shopping cart).

We also tested this notion in two experiments where we placed ads in magazines and found that, when putting greater effort into the advertising (in terms of expense and creativity) and integrating it carefully with the context, the ads could actually increase the audience’s perceived value of the magazine itself, so that they enjoyed it more and spent more time reading it (Rosengren and Dahlen Citation2013). The advertising was truly good in the sense that it did not only “not distract and disturb”, it even added to the perceived value of the magazine compared to when it did not feature advertising at all.

Again, the Super Bowl ads could serve as real-life example of TGA, and how it is potentially good for the media. According to a survey by Huffington Post (Spies-Gans Citation2016), among viewers under the age of 30, more people tuned in for the commercials than for the game. Similarly, in my native Sweden, many moviegoers come early to see the advertising that precedes the movie, which they find enhances their movie-going experience, because advertisers have traditionally put extra effort into making entertaining commercials. This is good for the theaters, which reap the benefits of both happier and timelier audiences. One could probably find real-life examples in several other media, for example ads in magazines, but I don’t know of any advertisers or media that have systematically targeted such effects. Yet.

Truly good advertising is good for society

I also believe that TGA can be applied in relation to society. Advertising has long been associated with negative societal impact. As Richard Pollay suggested in his highly cited article (Pollay Citation1986), more than a century’s evolution and refinement of good advertising has made it so powerful at persuasion that it reaches beyond the advertised products and impacts people’s perceptions of themselves and others, fostering, for example, materialism, anxiety and egotism. These effects are, of course, unintended, as good advertising does not aim to hurt people and society, it just wants to persuade consumers to buy and do things. But the disregard for advertising’s effects beyond what the advertiser intends are also at the root of the problem.

Research has found that exposure to advertising can indeed make people more materialistic (e.g., Kwak, Zinkhan, and Dominick Citation2002), lower their self-esteem (e.g., Dimofte, Goodstein, and Brumbaugh Citation2015) and reinforce negative stereotypes (e.g., Appel and Weber Citation2017). A common explanation for these effects is that advertising is a form of cultivation, which impacts reality because of its sheer pervasiveness in people’s everyday lives—it’s everywhere. In 2007, the mayor of Sao Paulo reacted to this pervasiveness by labeling outdoor advertising a form of pollution and banning it from the city’s public spaces, and several other cities have since followed suit, as reported in The Guardian (Mahdawi Citation2015).

For advertising to not be banned altogether at some point, it needs to recognize the effects it has on people beyond the scope of the advertiser’s interests. A first step has recently been taken in the updated, new definition of advertising as “brand-initiated communication that impacts people” (Dahlen and Rosengren Citation2016). This new definition holds advertisers accountable for potential, negative effects that their advertising has on society.

However, the recognition that advertising has extended effects on consumers provide opportunity to not only make “advertising that is not bad for society”, but to make truly good advertising that benefits society at the same time as it serves the advertiser’s interest. Recent experiments have found that carefully crafted portrayals and messages in ads can increase consumers’ interest in the advertised products and at the same time increase their own creative efficacy (Rosengren, Dahlen, and Modig Citation2013) and proneness to (unrelated) prosocial behavior (Defever, Pandelaere, and Roe Citation2011), as well as counteract stereotypes (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017a), and even increase social connectedness and empathy (Liljedal, Berg, and Dahlen Citation2020; Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017b).

TGA is good for society, because it needs to be. First, the opportunity to do good, to my mind, includes a moral obligation to do so. Second, advertisers will be at a much better position arguing that advertising does good rather than defending it as “not being bad” for society. Third, advertising needs to be about more than making money in order to attract talent (to both industry and academia) in the future. As commented by the Guardian (Vesty Citation2016) on a global survey of 27,000 LinkedIn members, “millennials want purpose over paychecks” (and the same was true to large extent for the other cohorts as well).

Examples of TGA from a societal perspective have become increasingly common, for example, some by-now-classic examples are Dove’s “Campaign for real beauty” featuring models of various shapes, sizes and colors, Always’ “Like a girl” femvertising, and IKEA’s “All homes are created equal” featuring gay couples and interracial families. However, these are still discussed as exceptions rather than the rule, both in industry and academia.

Let’s talk about truly good advertising

It is an old marketing axiom that one cannot please everyone, but this is basically what I suggest: advertising needs to be truly good for all parties involved. I am not saying it will be easy, maybe it is indeed impossible, but I would like to see all the brainpower in the industry and academia give it a try. Readers might not agree with me, but I am happy if TGA stirs a debate—if only to discuss something else than good advertising (it’s been talked about long enough already).

References

- Abayi, Mahsa, and Behnaz Khoshtinat. 2016. “Study of the Impact of Advertising on Online Shopping Tendency for Airline Tickets by considering Motivational Factors and Emotional Factors.” Procedia Economics and Finance 36:532–539. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30065-X.

- Åkestam, Nina, Sara Rosengren, and Micael Dahlen. 2017a. “Advertising “like a Girl”: toward a Better Understanding of “Femvertising” and Its Effects.” Psychology & Marketing 34 (8):795–806. doi: 10.1002/mar.21023.

- Åkestam, Nina, Sara Rosengren, and Micael Dahlen. 2017b. “Think about It–Can Portrayals of Homosexuality in Advertising Prime Consumer-Perceived Social Connectedness and Empathy?” European Journal of Marketing 51 (1):82–98. doi: 10.1108/EJM-11-2015-0765.

- Bates, CharlesA. 1896. Good Advertising: And Where It is Made. New York, NY.

- Appel, Markus, and Silvana Weber. 2017. “Do Mass Mediated Stereotypes Harm Members of Negatively Stereotyped Groups? A Meta-Analytical Review on Media-Generated Stereotype Threat and Stereotype Lift.” Communication Research 44:009365021771554. doi: 10.1177/0093650217715543.

- Becker, Gary S., and Kevin M. Murphy. 1993. “A Simple Theory of Advertising as a Good or Bad.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108 (4):941–964. doi: 10.2307/2118455.

- Boddewyn, Jean J. 1985. “Advertising Self-Regulation: private Government and Agent of Public Policy.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 4 (1):129–141. doi: 10.1177/074391568500400110.

- Cassano, Jay. 2013. “Advertising is dead, and advertising killed it”. Fast Company, August 27. https://www.fastcompany.com/3016450/advertising-is-dead-and-advertising-killed-it.

- CNBC. 2016. “Advertising’s dead… here’s why.” CNBC, July 12. https://www.cnbc.com/video/2016/07/12/advertising-is-dead-heres-why.html.

- Cooper, Robert G., and Elko J. Kleinschmidt. 1994. “Determinants of Timeliness in Product Development.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 11 (5):381–396. doi: 10.1111/1540-5885.1150381.

- Dahlen, Micael. 2001. “Banner Advertisements through a New Lens.” Journal of Advertising Research 41 (4):23–30. doi: 10.2501/JAR-41-4-23-30.

- Dahlen, Micael, Anton Granlund, and Mikael Grenros. 2009. “The Consumer-Perceived Value of Non-Traditional Media: effects of Brand Reputation, Appropriateness and Expense.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 26 (3):155–163. doi: 10.1108/07363760910954091.

- Dahlen, Micael, and Sara Rosengren. 2016. “If Advertising Won’t Die, What Will It Be? toward a Working Definition of Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 45 (3):334–345. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1172387.

- Dahlen, Micael, Sara Rosengren, and Edith Smit. 2014. “Why the Marketer’s View Matters as Much as the Message.” Journal of Advertising Research 54 (3):304–312. doi: 10.2501/JAR-54-3-304-312.

- Dahlen, Micael, Henrik Sjödin, Helge Thorbjornen, Håvard Hansen, Johanna Linander, and Camilla Thunell. 2013. “What Will ‘They’ Think? Marketing Leakage to Undesired Audiences and the Third-Person Effect.” European Journal of Marketing 47 (11/12):1825–1840. doi: 10.1108/EJM-10-2011-0597.

- Defever, Christine, Mario Pandelaere, and Keith Roe. 2011. “Inducing Value-Congruent Behavior through Advertising and the Moderating Role of Attitudes toward Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 40 (2):25–38. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367400202.

- Dimofte, Claudiu V., Ronald C. Goodstein, and Anne M. Brumbaugh. 2015. “A Social Identity Perspective on Aspirational Advertising: implicit Threats to Collective Self-Esteem and Strategies to Overcome Them.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 25 (3):416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2014.12.001.

- Ducoffe, Robert H. 1995. “How consumers assess the value of advertising.” Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising 17(1): 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10641734.1995.10505022

- Evans, Nathaniel J., Joe Phua, Jay Lim, and Hyoyeun Jun. 2017. “Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 17 (2):138–112. doi: 10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885.

- Friestad, Marian, and Peter Wright. 1995. “Persuasion Knowledge: lay People’s and Researchers’ Beliefs about the Psychology of Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (1):62–74. doi: 10.1086/209435.

- Goodrich, Kendall, Shu Z. Schiller, and Dennis Galletta. 2015. “Consumer Reactions to Intrusiveness of Online-Video Advertisements.” Journal of Advertising Research 55 (1):37–50. doi: 10.2501/JAR-55-1-037-050.

- Ha, Louisa, and Barry R. Litman. 1997. “Does Advertising Clutter Have Diminishing and Negative Returns?” Journal of Advertising 26 (1):31–42. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1997.10673516.

- Hsu, Tiffany. 2019. “The advertising industry has a problem: people hate ads.” New York Times, October 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/28/business/media/advertising-industry-research.html.

- Hudders, Liselot, Pieter De Pauw, Veroline Cauberghe, Katarina Panic, Brahim Zarouali, and Esther Rozendaal. 2017. “Shedding New Light on How Advertising Literacy Can Affect Children’s Processing of Embedded Advertising Formats: A Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Advertising 46 (2):333–349. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1269303.

- Kuntz, Tom. 2009. “News is dying because advertising is dying”. New York Times, April 6. https://ideas.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/06/why-advertising-is-failing-on-the-internet/

- Kwak, Hyokjin, George M. Zinkhan, and Joseph R. Dominick. 2002. “The Moderating Role of Gender and Compulsive Buying Tendencies in the Cultivation Effects of tv Show and tv Advertising: A Cross Cultural Study between the United States and South Korea.” Media Psychology 4 (1):77–111. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0401_04.

- Liljedal, Karina T., Hanna Berg, and M. Dahlen. 2020. “Effects of Nonstereotyped Occupational Gender Role Portrayal in Advertising: how Showing Women in Male-Stereotyped Job Roles Sends Positive Signals about Brands.” Journal of Advertising Research 60 (2):179–196. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2020-008.

- Mahdawi, Arwa. 2015. “Can cities kick ads? inside the global movement to ban urban billboards.” The Guardian, August 12. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/aug/11/can-cities-kick-ads-ban-urban-billboards

- Mason, Nancy A., and John A. Belt. 1986. “Effectiveness of Specificity in Recruitment Advertising.” Journal of Management 12 (3):425–432. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200311.

- Milgrom, Paul, and John Roberts. 1986. “Price and Advertising Signals of Product Quality.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (4):796–821. doi: 10.1086/261408.

- Muehling, Darrel D. 1987. “An Investigation of Factors Underlying Attitude-toward-Advertising-in-General.” Journal of Advertising 16 (1):32–40. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1987.10673058.

- Obermiller, Carl, and Eric R. Spangenberg. 1998. “Development of a Scale to Measure Consumer Skepticism toward Advertising.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 7 (2):159–186. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_03.

- O’Connor, Huw, Mark Kilgour, Scott Koslow, and Sheila Sasser. 2018. “Drivers of Creativity within Advertising Agencies: how Structural Configuration Can Affect and Improve Creative Development.” Journal of Advertising Research 58 (2):202–217. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2017-015.

- Otnes, Cele, Erin Spooner, and Deborah M. Treise. 1993. “Advertising Curriculum Ideas from ‘New Creatives.” The Journalism Educator 48 (3):9–17. doi: 10.1177/107769589304800302.

- Pollay, Richard W. 1986. “The Distorted Mirror: reflections on the Unintended Consequences of Advertising.” Journal of Marketing 50 (2):18–36. doi: 10.2307/1251597.

- Porter, Michael E. 1976. “Interbrand Choice, Media Mix and Market Performance.” The American Economic Review 66 (2):398–406. www.jstor.org/stable/1817253

- Prest, George. 2012. “Advertising is dying. Long live design.” The Guardian, October 26. https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2012/oct/26/george-prest-advertising-long-live-design

- Ritson, Mark. 2015. “The new breed of ad avoidance software is the biggest issue facing marketers.” Marketing Week, August 19. https://www.marketingweek.com/2015/08/19/mark-ritson-the-new-breed-of-ad-avoidance-software-is-the-biggest-issue-facing-marketers/

- Rosengren, Sara, and Micael Dahlen. 2015. “Exploring Advertising Equity: how a Brand’s past Advertising May Affect Consumer Willingness to Approach Its Future Ads.” Journal of Advertising 44 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2014.961666.

- Rosengren, Sara, and Micael Dahlen. 2013. “Judging a Magazine by Its Advertising.” Journal of Advertising Research 53 (1):61–70. doi: 10.2501/JAR-53-1-061-070.

- Rosengren, Sara, Micael Dahlen, and Erik Modig. 2013. “Think outside the Ad: can Advertising Creativity Benefit More than the Advertiser?” Journal of Advertising 42 (4):320–330. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2013.795122.

- Rosengren, Sara, Erik Modig, and Micael Dahlen. 2015. “The Value of Ambient Communication from a Consumer Perspective.” Journal of Marketing Communications 21 (1):20–32. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2014.970825.

- Rust, Roland T. 2016. “Comment: Is Advertising a Zombie?” Journal of Advertising 45 (3):346–347. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1180657.

- Schultz, Don. 2016. “The Future of Advertising or Whatever We’re Going to Call It.” Journal of Advertising 45 (3):276–285. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1185061.

- Speck, Paul S., and Michael T. Elliott. 1997. “The Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Advertising Clutter.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 19 (2):39–54. doi: 10.1080/10641734.1997.10524436.

- Spence, A. Michael. 1980. “Notes on Advertising, Economies of Scale, and Entry Barriers.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 95 (3):493–507. doi: 10.2307/1885090.

- Spies-Gans, Juliet. 2016.” Millennials are watching the super bowl for the commercials, not the game.” Huffington Post, February 4. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/yougov-super-bowl-commercials-game_us_56b105d3e4b0a1b96203f436

- Stewart, David W. 2016. “Comment: speculations of the Future of Advertising Redux.” Journal of Advertising 45 (3):348–350. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1185984.

- Szugalski, Stefan, Lars Bergkvist, and Micael Dahlen. 2014. “It’s Not the Quality but the Effort Itself That Matters? Advertiser Effort and Consumer Perceptions of Equitable Exchange.” Paper Presented at EMAC: Paradigm Shifts and Interactions, Valencia, June 3-6.

- Vesty, Lauren. 2016. “Millennials want purpose over paychecks. so why can’t they find it at work?” The Guardian, September 14. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/sep/14/millennials-work-purpose-linkedin-survey