ABSTRACT

Aim: To compare the understanding of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment in Japanese patients (aged <75 years vs. ≥75 years) with blood pressure (BP) targets as per the 2014 Japanese guidelines.

Methods: A 10-question survey was administered before and after treatment.

Results: Majority of patients aged ≥75 years did not achieve their BP targets (75%); >50% of these patients had little knowledge of hypertension and poor understanding of their physician’s explanation of it.

Conclusions: Elderly patients with hypertension (aged ≥75 years) require daily BP monitoring and detailed and repeated explanation of hypertension and BP targets.

Introduction

In 2010, 60% of Japanese men and 45% of Japanese women over the age of 30 years had hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) of 140 mmHg or higher, a diastolic BP of 90 mmHg or higher, or being under treatment with antihypertensive drugs (Citation1). The prevalence of hypertension increases with age (Citation1). Since 1980, the proportion of Japanese patients with hypertension who received antihypertensive treatment has increased. For example, in patients aged 70–79 years, the proportion of patients receiving treatment increased from 38% to 65% among men and from 45% to 69% among women (Citation2). Over the same period, the control rate, defined as the proportion of patients receiving antihypertensive treatment who have normal BP levels, also increased and was 33% among men and 44% among women aged 70–79 years (Citation2). Nevertheless, when viewed in the global context, the control rate among Japanese patients with hypertension remains low (Citation3). Strict BP control is recommended in elderly patients (Citation2), and therefore, it is important to know which factors are associated with effective BP control in this population.

In a prospective, multicenter, open-label study, elderly patients with hypertension received angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker/calcium channel blocker combination therapy (Citation4). To evaluate patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with antihypertensive treatment, a 10-question survey was administered at baseline and at the end of the study. Although both patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction rates improved after treatment and the gap between them decreased (Citation4), there were differences in patients’ and physicians’ opinions about patients’ understanding of hypertension. At the end of the study, 81.5% of patients answered that they understood their physicians’ explanations of hypertension. On the other hand, only 64.7% of physicians believed that their patients understood their explanation of hypertension at the end of the study. We hypothesized that this difference in perceptions may be one of the reasons for the low BP control rate among elderly patients in Japan. Here, the results of this study were analyzed to determine the differences between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets. The aims of this analysis were to (Citation1): compare the understanding of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment among patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets; and (Citation2) further analyze the results in patients <75 and ≥75 years old. This information was then used to develop recommendations for the management of hypertension in elderly patients.

Methods

Study design

The design of this study has been described previously (Citation4). Briefly, this was an exploratory, open-label study conducted at 22 sites in Kagoshima, Japan, in 2015 and 2016. Participating physicians (n = 76) were all specialist cardiologists. Patients aged ≥65 years who had Grade 1 or 2 essential hypertension were eligible. In the screening phase, patients received 20 mg/day of olmesartan medoxomil or 16 mg/day of azelnidipine for 8 weeks. Those who did not achieve age-appropriate BP targets as defined in the 2014 Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014) (Citation2) at the end of the screening phase, entered a treatment phase. At entry, patients were given an information leaflet describing the goals of treatment for hypertension according to the JSH guidelines, including their own age-appropriate target BP. Physicians explained the targets and the study to them before treatment was started. In the treatment phase, patients received olmesartan medoxomil plus azelnidipine combination tablets for 12 weeks. A 10-question survey was administered to patients and physicians at the beginning and end of the treatment phase (). For questions 1–8, respondents were asked to select one of five possible answers (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree). Those who answered “strongly agree” or “agree” were considered to be satisfied with treatment. Question 9 was a yes/no question about whether the respondent was aware of their target BP (patients) or had informed the patient about their target BP (physicians). Respondents who answered yes to question 9 were asked to choose their clinic BP target (130, 140, 150, or 160 mmHg) and home BP target (125, 135, 145, or 155 mmHg). In this study, survey questions were divided into five groups: patient involvement (Q2), knowledge and understanding of hypertension (Q3, Q4, Q9), treatment satisfaction and patient-physician relationship (Q1, Q5, Q6), perception of BP reduction (Q7, Q8), and BP targets (Q10).

Table 1. Survey questions.

During treatment, patients measured their BP at home twice daily, after getting up and before going to bed.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as well as the guidelines of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan and the International Council for the Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating sites. All of the patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Statistical analysis

The final BP target was defined as a home early morning systolic BP of <135 mmHg and a clinic systolic BP <140 mmHg (Citation2). Home BP assessments were calculated as the mean of the most recent 5 days of measurement. The proportions of patients who achieved their BP targets at the end of the treatment phase were calculated. The responses of patients <75 and ≥75 years old were analyzed separately. The chi-squared test was used for hypothesis testing in comparisons between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets. The significance threshold was set at 0.05.

Results

BP target achievement

Overall, 70 patients for whom BP readings were obtained at both baseline and week 12 were included in the present analysis. The home early morning and clinic systolic BP values for these patients are summarized in , in which the final BP targets (Citation2) are presented as dotted lines. None of the patients <75 years old achieved both home and clinic BP targets at baseline (), and 23.7% of these patients achieved BP targets at week 12 (). Similarly, 2.4% of patients ≥75 years old achieved their home and clinic BP targets at baseline (); this increased to 25.0% at week 12. Overall, the proportion of patients who achieved both clinic and home BP targets was only 1.2% at baseline, and this proportion increased to 24.3% at week 12 (Supplementary figure).

Figure 1. Distribution of home early morning SBP and clinic SBP at baseline and week 12 of treatment. A) SBP values at baseline in patients <75 years old; B) SBP values at week 12 in patients <75 years old; C) SBP values at baseline in patients ≥75 years old; D) SBP values at week 12 in patients ≥75 years old. Dotted lines represent final BP targets, defined as <135 mmHg for home early morning SBP and <140 mmHg for clinic SBP. Percent values represent the proportion of patients with SBP values above or below these targets. SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Overall results of the patient and physician questionnaires

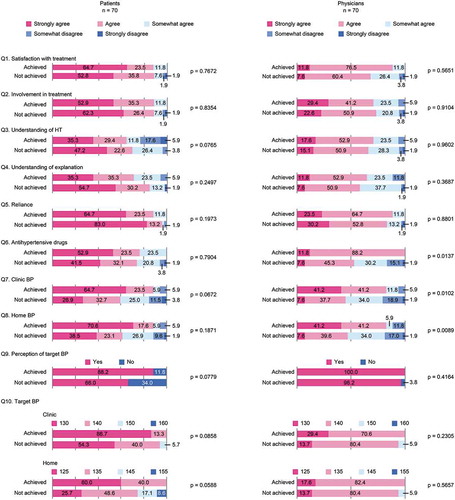

Among patients who completed the questionnaire, there were no significant differences in patient involvement (Q2), knowledge and understanding of hypertension (Q3, Q4, Q9), treatment satisfaction and patient-physician relationship (Q1, Q5, Q6), perception of BP reduction (Q7, Q8), or BP targets (Q10) between those who achieved their BP targets and those who did not ().

Figure 2. Achievement of target blood pressures and satisfaction survey results. Patients who answered “strongly agree” or “agree” were considered to be satisfied with treatment. Patients who answered “somewhat agree”, “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” were considered to be dissatisfied with treatment.

In the physician questionnaire, significant differences were observed in the level of satisfaction with the antihypertensive drug used by patients who achieved their BP targets compared with patients who did not (Q6, p = .0137; ). From the physicians’ point of view, there were no significant differences in responses to other questions about treatment satisfaction and the patient-physician relationship between patients who achieved their BP targets and those who did not (Q1, Q5; ). In addition, physicians reported that the proportion of patients whose clinic (Q7) and home (Q8) BP decreased in the preceding 3 months was significantly higher among those who achieved their BP targets at the end of the treatment period compared with those who did not (Q7, p = .0102 and Q8, p = .0089; ). There were no significant differences in physicians’ responses to questions about patient involvement (Q2), knowledge and understanding of hypertension (Q3, Q4, Q9) and BP targets (Q10; ).

Age subgroup analysis of patient questionnaire results

The number of patients <75 years old included in the present analysis (n = 38) was similar to the number of patients ≥75 years old (n = 32). At the end of the treatment period, 23.7% of patients <75 years old and 25.0% of those ≥75 years old achieved their final BP target.

Patient involvement (Q2)

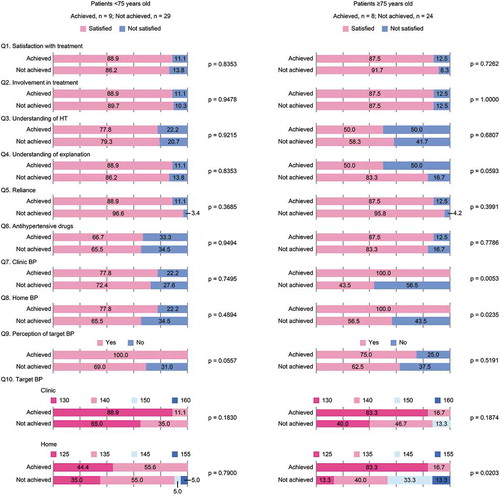

There were no significant differences in the level of involvement in treatment between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets among patients <75 years old (p = .9478) or patients ≥75 years old (p = 1.0000; ).

Figure 3. Patient satisfaction survey results stratified by target blood pressure achievement and patient age. Patients who answered “strongly agree” or “agree” were considered to be satisfied with treatment. Patients who answered “somewhat agree”, “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” were considered to be dissatisfied with treatment.

Knowledge and understanding of hypertension (Q3, Q4, Q9)

Among patients <75 years old, most had a satisfactory understanding of hypertension (Q3) and there were no significant differences between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets (Q3, p = .9215; ). In addition, most patients in this age cohort understood their physicians’ explanations of hypertension (Q4), and no significant differences were observed in this between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets (Q4, p = .8353; ).

Among patients ≥75 years old, 50.0% of those who achieved their BP targets reported having little or no knowledge about hypertension (Q3), compared with 41.7% of those who did not achieve their BP targets (Q3, p = .6807; ). Furthermore, in this age group, 50.0% of patients who achieved their BP targets and 16.7% of patients who did not reported that they did not understand, or poorly understood, their doctors’ explanations of the disease (Q4, p = .0593; ).

Knowledge of BP targets was higher among patients who achieved their targets at the end of the study (Q9; ). Among patients ≥75 years old, 25.0% of those who achieved their BP targets and 37.5% of those who did not reported that their doctor did not explain BP targets to them (Q9, p = .5191). On the other hand, 100.0% of patients <75 years old who achieved their BP targets knew what their targets were, while only 69.0% of patients who did not achieve their targets knew them (Q9, p = .0557).

Treatment satisfaction and patient-physician relationship (Q1, Q5, Q6)

There were no significant differences in responses to Q1, Q5 and Q6 between patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets among patients <75 years old and patients ≥75 years old ().

Perception of BP reduction (Q7, Q8)

Among patients <75 years old, there were no significant differences in the proportions of patients who reported reductions in either clinic (Q7) or home (Q8) BP between those who did and did not achieve their BP targets.

Among patients ≥75 years old, the proportion of patients who reported reductions in clinic BP (Q7; 100.0%) was significantly higher among patients who achieved their BP targets at the end of the treatment period compared with those who did not (Q7, 43.5%, p = .0053; ). In addition, the proportion of patients who reported reductions in home BP (Q8; 100.0%) was significantly higher among patients who achieved their BP targets compared with those who did not (Q8, 56.5%, p = .0235) in this age cohort ().

BP targets (Q10)

BP target levels tended to be lower in patients who achieved their BP targets compared with those who did not (). This was true for both clinic and home BP values, as well as for patients <75 and ≥75 years old. In addition, among patients ≥75 years old, home BP targets were significantly different in patients who achieved their targets compared with patients who did not (Q10, p = .0203; ).

Discussion

In the present analysis, data from an exploratory, open-label, multicenter, intervention study in elderly patients with hypertension (Patients’ Voice Study) (Citation4) were analyzed to determine whether knowledge and understanding of hypertension were associated with the achievement of BP targets. There were no significant differences in how patients who did and did not achieve their BP targets answered any of the questions. On the other hand, physicians’ responses showed that they were more satisfied with the antihypertensive treatment in patients who achieved their BP targets than in patients who did not.

Among patients <75 years old, there were no significant differences in responses to any of the questions between those who did and did not achieve their BP targets. All of the patients <75 years old who achieved their BP targets reported being aware of these targets, while only 69.0% of those who did not achieve their BP targets were (Q9). However, many patients in this age group had BP targets lower than those recommended in the JSH 2014 guidelines (clinic systolic BP <130 mmHg, home systolic BP <125 mmHg) (Citation2). Therefore, it is likely that these patients expected to reach lower BP values than those recommended in the guidelines.

Patients who did not achieve their BP targets tended to report higher target levels compared with those who did (Q10). However, statistically significant differences were observed only in home BP target levels in patients ≥75 years old. Because target home BP was only included in Japanese guidelines for the management of hypertension in 2014, it is possible that awareness of this has not spread to all patients ≥75 years old. All patients ≥75 years old who achieved their BP targets reported that their BP levels decreased in the previous 3 months. This was significantly higher than the proportion of patients who did not achieve their BP targets in this age cohort. This could be because patients who achieved their BP targets were more invested in their treatment and monitored their BP more closely.

There was a discrepancy between patients and physicians about whether BP targets were explained; however, this discrepancy was greater among patients ≥75 years old. In this group, 25.0% of patients who achieved their BP targets and 37.5% of those who did not reported that they did not recall their physician explaining these targets to them (Q9). Among patients <75 years old, the corresponding proportions were 0.0% and 31.0%, respectively (Q9). On the other hand, doctors reported explaining BP targets to 100.0% of patients who did and 96.2% of those who did not achieve their BP targets in both age cohorts (Q9).

The information from this study can be used by physicians to tailor antihypertensive therapies for elderly patients, and the following recommendations for the management of hypertension in the elderly are proposed. For patients <75 years old, healthcare professionals should provide a clear explanation of target BP levels and regularly remind patients about the need for and benefits of achieving these targets, focusing particularly on home BP levels. Healthcare professionals should encourage patients to adhere to antihypertensive treatment. For patients aged ≥75 years, healthcare professionals should encourage daily BP monitoring and stimulate and maintain patients’ involvement in treatment, regardless of results.

Results of previous studies on the management of hypertension in elderly patients have been mixed. In a cross-sectional study of 1540 patients ≥80 years old conducted in Spain, only 40.8% achieved target BP levels of <140/90 mmHg (<130/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes, chronic renal disease or cardiovascular comorbidities). Patients who did not achieve target BP levels were more likely to have metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, a history of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, renal disease, and stroke, and they were more likely to be smokers (Citation5). On the other hand, in a retrospective chart review conducted at elderly care facilities in Canada, 467 of 733 patients (64%) were able to achieve the target BP level of ≤140/90 mmHg (≤130/80 mmHg for patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, or a systolic BP of ≤140 mmHg for patients with isolated systolic hypertension) (Citation6). Data from the present study showing that 23.7% of patients <75 years old and 25.0% of patients ≥75 years old achieved their BP targets confirm earlier findings that BP control in Japan is suboptimal and lower than in other parts of the world (Citation3). Elderly patients, in particular, relied more on BP assessments and management at their clinic than on self-management at home, indicating that more can be done to engage elderly Japanese hypertensive patients in their own self-management.

The 2013 European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension suggested three main reasons for the low rate of BP control in real-life clinical practice: physician inertia, low treatment adherence and deficiencies in healthcare systems’ approaches to chronic diseases (Citation7). Age-related barriers to BP control were not considered (Citation7). Further research into this area is warranted. Target BP levels for elderly patients have been the subject of debate (Citation8–Citation10). Irrespective of what the precise values are, daily BP monitoring should be encouraged and healthcare professionals should develop close relationships with their patients.

Limitations of the present study include a small sample size, the use of only systolic BP to define the target BP (Citation11) and the fact that the questionnaire was not designed to meet the objectives of the study.

In conclusion, many patients <75 years old who achieved their target BP levels at the end of the study knew their target BP levels. On the other hand, many patients aged ≥75 years had little knowledge of hypertension and did not understand their physicians’ explanations of it. The management of elderly patients with hypertension requires a special approach. For patients <75 years old, clear explanations of BP targets are recommended. For patients ≥75 years old, daily BP monitoring is indicated, and detailed and repeated explanations of hypertension and BP targets are needed.

Disclosure of interest

M.O. has received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, Boehringer lngelheim, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Astellas Pharma Inc., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Teijin Pharma Limited, Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Kowa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., and Shionogi & Co., Ltd, and research funding and/or scholarship grants from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Astellas Pharma Inc., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Actelion Pharmaceuticals Japan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Genzyme Japan, Teijin Home Healthcare, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (143.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the late professor Chikuma Hamada for statistical analysis. We would also like to thank Yoshiko Okamoto and Georgii Filatov of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for providing medical writing support funded by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.

The authors also express their great appreciation to the Japan Academic Research Forum (J-ARF) for protocol development and data evaluation.

Data availability statement

We have no plan to share data that supports the results or analyses presented in this paper.

Supplementary material

supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. The 2010 national health and nutrition survey in Japan. 2012, Japanese. E-III. 2012. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html

- Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ishimitsu T, Ito M, et al. The Japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253–390.

- Tocci G, Cicero AF, Salvetti M, Passerini J, Musumeci MB, Ferrucci A, Borghi C, Volpe M. Attitudes and preferences for the clinical management of patients with hypertension and hypertension with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Italy: main results of a survey questionnaire. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10:943–54. doi:10.1007/s11739-015-1256-y.

- Ikeda Y, Sasaki T, Kuwahata S, Imamura M, Tanoue K, Komaki S, Hashiguchi M, Kuroda A, Akasaki Y, Hamada C, et al. Questionnaire survey from the viewpoint of concordance in patient and physician satisfaction concerning hypertensive treatment in elderly patients – patients voice study. Circ J. 2018;82:1051–61.

- Rodriguez-Roca GC, Llisterri JL, Prieto-Diaz MA, Alonso-Moreno FJ, Escobar-Cervantes C, Pallares-Carratala V, Valls-Roca F, Barrios V, Banegas JR, Alsina DS. Blood pressure control and management of very elderly patients with hypertension in primary care settings in Spain. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:166–71. doi:10.1038/hr.2013.130.

- Tsuyuki RT, McLean DL, McAlister FA. Management of hypertension in elderly long-term care residents. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:912–14. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70698-6.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr., Grimm RH Jr., Cutler JA, Simons-Morton DG, Basile JN, Corson MA, Probstfield JL, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–85.

- JATOS study group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115–27. doi:10.1291/hypres.31.2115.

- Garrison SR, Kolber MR, Korownyk CS, McCracken RK, Heran BS, Allan GM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD011575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2.

- Basile J. Blood pressure responder rates versus goal rates: which metric matters? Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;3:157–74. doi:10.1177/1753944708101552.