ABSTRACT

As conservatives ban the teaching of Black history and critical understandings of race across the country, Black teachers are turning again to fugitive pedagogies, or subversive ways of teaching, to counter anti-blackness and imagine the world anew. This study drew on data from interviews, classroom observations, and student focus groups to demonstrate how a Black teacher fugitive professional learning space helped to motivate and inform the pedagogies of a Black secondary school teacher. Using the theoretical framing of BlackCrit and the concept of fugitivity, I share how one teacher reflected on and made sense of how his participation in this professional learning space impacted his pedagogical practice. The research provides insight into how Black teachers learn to use fugitive pedagogies to create Black-affirming collective learning spaces for their students.

Introduction

Black folk have long been charged with “making a way out of no way,” and they have historically used education as a path toward economic and social equality (Du Bois, Citation1903; Duncan, Citation2020). After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, Black teachers turned to more formal schooling to lead Black people out of the oppression of slavery as an avenue for “racial uplift” (Irvine, Citation1989, p. 54) through using exemplary teaching to overcome the systematic withholding of education from enslaved peoples and their descendants (Siddle Walker, Citation2000). As teaching was one of the few professions available to Black people, it has been a career held in great esteem within the Black community (Madkins, Citation2011).

However, even though Black educators have been influential educators, after the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, thousands of Black teachers lost their jobs as integrating schools retained white teachers at the expense of Black teachers (Siddle Walker, Citation2000), resulting in a 41.7% reduction in Black teacher employment across 759 southern school districts (Thompson, Citation2022). Due to these mass firings, the Black community experienced a disruption in the legacy of excellence and expertise from Black leadership and role models (Tillman, Citation2004). This Brown legacy persists today: while Black students make up 15% of the total student population, Black teachers make up only 7% of the teaching population (U.S. Department of Education, Citation2017). In light of this history of Black teachers, this ethnographically informed study follows how one high school humanities teacher, Medgar, used a Black teacher professional affinity space to continue the cycle of innovative and liberatory Black teacher pedagogies (BTP).

Black teacher pedagogies

There is a long-standing body of literature on Black teacher pedagogies.Footnote1 Many scholars have described Black teacher pedagogies by emphasizing how Black teachers support positive racial identity formation for Black and other racially minoritized youth and teach students to be critical consumers of the racialized world in which they live. Black teacher pedagogies undergird a legacy of activism, high expectations, and innovative teaching for their students, and their beliefs around addressing anti-blackness show up in their curriculum, classroom practices, and leadership (Givens, Citation2021). Accordingly, Black teachers have used innovative pedagogies to support students to learn academic and social content that does not compromise their racial and cultural identities.Footnote2

Due to their understanding of anti-blackness and the underlying systemic issues in their students’ lives, Black teachers are less likely to blame Black students for academic or behavioral imperfections (Foster, Citation1990; Mitchell, Citation1998). Black teachers also tend to have high expectations for academic achievement, use their experiential knowledge of navigating anti-Black bias to expose the hidden curriculum of school, and offer a positive example of the outcome of schooling (Milner, Citation2006). A McKinney de Royston et al. (Citation2021) study found that Black teachers felt a need to protect Black students from racialized harm, and they used their knowledge of institutionalized racism to reframe Black students’ behavior through more asset-based lenses. Black teachers are generally more likely to interpret Black student behavior more positively and less subjectively, significantly decreasing the likelihood of Black students interacting with the school discipline system (Gregory & Weinstein, Citation2008).

Medgar, the teacher at the heart of this study, builds on these pedagogical practices through the prism of his students’ particular needs in 2022, a time when students and teachers alike were still processing the events of 2020: the mass deaths of the COVID-19 pandemic, the racial reckoning of Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and the growing criminalization of the teaching of history, Blackness, and Critical Race Theory. These current social and physical attacks on Black life have impacted how Black teachers must take up their work. As classrooms have become increasingly surveilled, Black teachers must employ pedagogical strategies of an imagined fugitivity. Fugitivity invokes the connotation of enslaved Black people running toward a real or imagined freedom, which Campt (Citation2014) argues “is the quotidian practice of refusal.” This refusal is a rebellion against an anti-Black system, even if this refusal to participate puts one’s livelihood at risk. Medgar engaged in fugitivity by participating in the Black Teacher ProjectFootnote3 (BTP), a Black community organization that serves as a Black teacher fugitive space (Stovall & Mosely, Citation2023) for teachers to build their capacity to navigate and disrupt anti-blackness, improve their pedagogies, and build their leadership aptitude. This article explores how Medgar transferred his learnings in this fugitive space to his classroom. I first asked: How does Medgar feel his professional learning in a Black teacher fugitive space shapes his thinking? And then: How is this reflected in observations of his teaching and in his students’ perspectives?

Theoretical framework

BlackCrit

In this afterlife of slavery (Hartman, Citation1997) and the afterlife of school segregation (ross, Citation2021a), scholars have turned to Dumas and ross’s (Citation2016) conceptualization of BlackCrit, for this lens allows for the “specificity of the Black” (Wynter, Citation1989, as cited in Dumas & ross, Citation2016, p. 417) in understanding the pervasiveness of anti-Black racism in our institutions. Dumas and ross (Citation2016) assert that:

BlackCrit in education promises to help us more incisively analyze how social and educational policy are informed by anti-blackness, and serve as forms of anti-Black violence, and following from this, how these policies facilitate and legitimize Black suffering in the everyday life of schools.

BlackCrit will be central to how I analyze and think about Medgar’s stories and experiences, as it affords me a lens to consider how he encounters hostile, anti-Black working environments that are endemic to the American way of life, as well as how he conducts what Dumas and ross (Citation2016) call “Black liberatory fantasy” (p. 431) or the ways that Black teachers fight, resist, and disrupt these environments. Through the lens of BlackCrit, I am able to more carefully examine how Black teacher fugitive space impacts Medgar’s enactments of Black-affirming pedagogies and practices that counter white hegemonic norms. In the following section, I will discuss how the concept of fugitivity describes the active work that many Black teachers do to stay in the teaching profession.

Educational fugitivity

Fugitivity (Harney & Moten, Citation2013) describes the subversive work that Black people take up to continue the revolutionary work of Black intellectualism. Since enslavement, when human traffickers would maim or kill Black people for teaching others to read or write, Black teachers have often had to teach subversively because of the risk of violence or harm. In Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens (Citation2021) argues that this legacy has continued. Black people must continue to steal their education because “The surveillance of black intellectual life was a carryover from slavery, reflecting a set of enduring relations that structured black experiences of schooling” Givens, Citation2021, (p. 102). Patel (Citation2016) argues that fugitivity occurs today when agentic learning is rendered dangerous, and Coles et al. (Citation2021) remind us that although fugitivity must happen underground, “fugitive logic informs us that these spaces and the people who live beautiful lives in them are markers of emancipatory existences” (p. 106). As BlackCrit allows us to see anti-blackness as endemic to our schools and society at large, fugivitity allows us to see how teachers implementing these responsive fugitive pedagogies are the latest iteration of Black teachers enacting refusals against anti-blackness in order to imagine other possible worlds.

Black Teacher Fugitivity. In earlier work (Stovall & Mosely, Citation2023), we built on ross’s (Citation2021a) notion of Black educational fugitive space to argue that the BTP is a Black teacher fugitive space. The significant characteristics of the Black teacher fugitive space were that BTP teachers: (1) constantly ratified one another’s ideas in ways that promoted collective affirmation; (2) “spoke plain” and refrained from regulating their speech in ways that helped them feel more fully and authentically embodied; and (3) brought their multifaceted identities to this space in ways that disrupted monolithic representations of Blackness. Being more fully embodied, expressing emotions, and experiencing joy were all components of fugitive practice. Building on what these Black teachers articulated about how the BTP helped sustain them in the profession, I wanted to know more about the potential impact on their teaching. To explore this inquiry, I designed an ethnographically oriented study where I followed Medgar from this group into his classroom to study his pedagogies and his students’ reactions to those pedagogies.

Methods

I met Medgar in 2019 when I followed him for a year in the BTP Inquiry Group. Two years after this study (2021–2022),Footnote4 I went into Medgar’s classroom to examine how he took up the teachings of the BTP. To guide my findings, I asked, “How does Medgar feel that his professional learning in a Black teacher fugitive space shapes his thinking? And how is this reflected in observations of Medgar’s teaching and in his students’ perspectives?” The data sources in this study included participant observations, interviews, and focus groups.

Setting and participants

The Black Teacher Project is an all-Black affinity space that allows Black teachers who have perpetuated anti-Black harm to unlearn these practices. However, it tended to attract what Mawhinney and Baker-Doyle’s (Citation2023) research participants call “a specific kind of unicorn-y teacher” (p. 559) who is both racially minoritized and committed to the deconstruction of anti-Black systems (p. 6). For Black teachers, the BTP serves as a site of resistance against norms of whiteness and the broader anti-Black organizational structures. This article examines a Black teacher who criticizes white dominant norms, condemns anti-blackness, and intentionally seeks out Black affinity spaces to help him negotiate these philosophical commitments. In making this choice, I am shedding light on the possibilities for Black teachers who are explicit in both countering anti-blackness in schools and creating new spaces of possibility for their students.

Medgar

I selected Medgar for the study because he was steeped in the ethos of BTP through participating in all of their programming. In addition to the inquiry group, he also had participated in the BTP’s high- touch three-year Fellowship program, to which Black teachers must apply to. Teachers are selected based on their commitment to learning approaches to becoming Black teacher leaders who lead for liberation for themselves and their students. He also participated in the yearly virtual BTP Sustainability Institute, monthly wellness programs, and various one-off gatherings. I therefore chose Medgar because he was well-versed in BTP’s pedagogical mission, and he specifically mentioned that the BTP inspired his pedagogy in his interviews during the 2019–2020 school year. I asked Medgar why he ultimately decided to participate in the study, and he offered that he was initially hesitant about participating because he did not “consider [himself] extraordinary” since his work is “instinctual,” but I had reminded him that his work “should be documented because he has a legacy and something to offer the art and craft of teaching.”

Medgar has a gregarious personality, and he makes friends everywhere he goes. When not teaching or preparing to teach, he can most often be found dancing—in his living room, for his private TikTok, in a Zumba class he instructs, or out on the town with his husband and friends. At the time of the study, Medgar was in his seventh and final year of teaching high school humanities (Hip Hop, humanities, and ethnic studies) at Golden Gate School, an independent private school in San Francisco. Medgar was, for a while, the only Black teacher at his school, and at the time of the study, he mentored a Black teacher who was working as a fellow to gain his teaching credential. Most of the students came from affluent families, and Golden Gate is approximately 60% white and 40% racially minoritized youth, with 1% of that percentage identifying as Black. Medgar’s experiences in an elite secondary school while teaching several Black-centric courses with Black-affirming pedagogy provided an intimate look at how a teacher can teach in ways that uplift and support Black people even when there are few Black students present.

Data collection

I took a BlackCrit Ethnography (Coles, Citation2019) approach to data collection and analysis, which allowed me to center the lenses of Blackness and anti-blackness as I sought to understand how Medgar incorporated what he had learned in the Black teacher fugitive space into his classroom pedagogies. To further explore how Black teacher fugitive space impacted student learning, I conducted audio-recorded, semi-structured interviews (60 minutes in length) with Medgar three times throughout the school year, using Seidman’s (Citation2006) framework for a three-interview series. During the first interview, I elicited a detailed background on Medgar’s life and what brought him into the teaching profession. In the second interview, I aimed to develop a better sense of his teaching philosophies, lessons learned from the BTP inquiry group, and student work and lesson plans that he felt best illustrated his approaches to teaching. In the final interview, I presented Medgar with data on his pedagogies (excerpts from audio recordings, as well as examples from my field notes) and asked him to engage in participant retrospection (Martínez, Citation2010; Rampton, Citation2003) by commenting on and explaining his pedagogies in his own words. I wanted to honor him as the knower of his experiences and center his storytelling as a valid source of knowledge (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002). Lastly, I examined how students made sense of Medgar’s pedagogies. Using a semi-structured interview protocol, I conducted audio-recorded 30-minute focus groups with 61 of Medgar’s students to elicit their perspectives on their learning and experiences in their classroom. I invited students to provide specific examples of lessons and activities that were particularly impactful in addition to their general impressions of the learning environment.

I attended Medgar’s classes an average of three days a week during the spring semester of 2022. I engaged in observant participation (Vargas, Citation2006) in his pedagogical practice, taking detailed field notes in his classrooms, lunch and extracurricular activities, and the transitional time between instructional blocks and other daily routines. In Medgar’s ethnic studies class, I occasionally taught lessons, as the content aligned with my research and interests. In addition to taking field notes, I audio-recorded the whole class, small group, and dyadic interactions among students and teachers to study Medgar’s pedagogies and how students engaged with and reacted to his pedagogical choices.

Data analysis

For the interviews and focus groups, I began with a codebook I had developed across my various Black teacher studies; I also coded inductively for emergent salient themes as I worked through the data. After transcribing the audio recordings of the classroom visits and student interviews/focus groups, I began to code each idea unit (Jacobs & Morita, Citation2002) in the transcriptions and field notes to look for themes in Medgar’s pedagogy and student responses to these Black-affirming spaces. After coding, I worked with a second coderFootnote5 to employ the transcripts using both analytic induction (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017) and theoretically informed sense-making with our constructs of fugitivity, pedagogy, and BlackCrit in each transcript. For an academic quarter, we met to talk through emerging themes, wrote analytical memos about salient moments in class, and searched for disconfirming cases. We came to our conclusions by engaging in data display, putting codes like “pedagogy” and “discussion of anti-blackness” together so we could find common patterns and findings. To verify our work, after I drafted the initial findings, I shared the excerpts and the preliminary findings with Medgar to co-theorize and co-analyze how the BTP influenced his pedagogy, retention, and navigation of anti-blackness (Bonilla, Citation2015).

Findings

For this study, I wondered how the BTP impacted Medgar’s pedagogies and how his students reacted to those pedagogies. I first discuss what Medgar reported that he learned from the BTP. Then, I explore how what he learned from the BTP aligned with what I observed and learned from the students. Finally, I discuss how his pedagogies supported him in creating a collective learning space and how this space supported Black students and disrupted anti-Black consciousness in white students.

Shaping Medgar’s pedagogies

When I asked Medgar how the BTP influenced his teaching, he talked about how much Mariah, one of the facilitators of the BTP inquiry group, inspired him. He reflected:

There’s a lot of Mariah that I’ve been inspired by and have applied to my pedagogical style to my classroom …. Mariah was a huge influence on me because of … [her] unapologetic Blackness …. I was inspired because I was in a PWI [Predominately White Institution], and I [was] code-switching, sometimes muting my Blackness as a way to survive, but she kind of gave me permission to lean into it.

Medgar was “very much influenced” by Mariah’s teaching style, and he appreciated how she structured and organized the professional learning space. Medgar named pedagogical tools that added to his classroom’s organization and overall climate, like playing Lo-fi beats while students worked or including Black-affirming ways of grounding his students during transitions, such as the Ghanaian call and response song “Shay Shay Koolay.” He also made space for joy and laughter in the classroom, hosting classroom potlucks in the middle of a long week, allowing students to run to the gym to play basketball for five minutes to pick up their energy, and debating the latest celebrity or reality TV gossip. His reference to watching Mariah teach highlights how influential it was for Medgar to see the possibility of what his pedagogy could be, that he could bring the “human” back to his humanities classroom. In these ways, learning from other Black teachers in a fugitive space allowed Medgar to witness his peers’ teaching, helping him see the potential in his own teaching practice.

In addition to impacting his pedagogies, Medgar discussed how the BTP impacted the way that he learned to “lean into” his Blackness in ways that were not accessible to him before. Seeing examples of Mariah embracing her “unapologetic Blackness” allowed him to see that he could bring more of his racial and cultural identities into his teaching practice. He noted that he felt that he needed to “mute” his Blackness out of survival, but witnessing other ways of being helped him recognize that bringing his racial and cultural identities into the classroom is actually more sustaining in the long run. His use of the word “permission” revealed that Medgar needed encouragement to try more authentic ways of being. Medgar credited Mariah for the opportunity to reimagine his teaching practice and how he expressed his Blackness in primarily white spaces.

Creating liberated learning spaces

The BTP prides itself on working towards designing liberated learning spaces, or learning spaces that seek to become free from anti-Black norms. Medgar reported feeling responsible for creating a classroom learning space that allows students to show all of who they are and disrupts injustice in his classroom and beyond. Medgar stated that the BTP:

has helped me to embrace my identity as a teacher … I’m at a predominantly white school … and there’s three Black kids in the class, right? I see my role as providing this great supportive learning environment for them and also for teaching white folks not to call the cops on us.

This interview excerpt highlights how Medgar sees himself in the dual roles of creating supportive learning environments for Black children and preventing white students from causing future Black harm. I next discuss how Medgar co-created spaces where students supported each other to show up more authentically. Finally, I demonstrate how these spaces concurrently supported Black students and taught white students the critical consciousness they need to be co-conspirators (Love, Citation2019) in disrupting anti-blackness.

Supporting the collective

Medgar cared about students taking care of each other. He frequently told his students to work with “their homies” and often had them learn in small groups. He would start each lesson stretched out on the floor for a mindful meditation practice followed by a whip-around check-in so that all voices were heard in the room each day. These whip-arounds were usually light-hearted in nature, such as asking about people’s astrological signs or what Drake mood they were in from a series of photos. In his ethnic studies class, he would start each class by having the students chant the Valdez and El Teatro (Citation1990) poem “In Lak’ech” in unison. When he was ready for class to begin, the class would say together: “Tú eres mi otro yo. You are my other me/Si te hago daño a ti, If I do harm to you/Me hago daño a mi mismo/I do harm to myself/Si te amo y respeto, If I love and respect you/Me amo y respeto yo. I love and respect myself” (p. 174). This poem consistently reminded the students that they were a collective and must invest in each other for their healing and growth.

As a result of this commitment, the students in this ethnic studies class became very invested in others’ learning and growth. They pushed each other to overcome their fear of mistakes so they could grow together. For example, after a particularly challenging discussion around race, Nadia, a Black female student, discussed the importance of making mistakes and shared that just because she was Black did not mean that she knew everything there was to understand about the construct of race. She explained:

I’m not scared of making mistakes [students start snapping] because I think a lot of the ways that I’ve learned has been through making those mistakes. And I know that can be uncomfortable, especially for the white people in the room because making the mistakes feels like it is offending someone. And I want to create more of a culture where … How do I say this? If there is any—and I said this to other people before—if there’s any space in the universe where these discussions are appropriate to have, it’s going to be this classroom.

Nadia’s response highlights how she saw herself as contributing to the classroom space. She modeled her willingness to be vulnerable in the space and invited her classmates, especially her white classmates, to do the same. Her mention of her motivation “to create more of a culture where … ” highlights her commitment to being a part of the co-construction of the space. She also highlighted how particularly unique this space is, as Medgar created a classroom environment where frank discussions about race are normal and appropriate. Similar to the BTP, the students ratified each other through audible forms of support, like when her classmates started snapping their fingers in agreement.

Creating space for Black students

As mentioned in his interviews, Medgar wished to create safe spaces for Black students to be seen and affirmed. For Medgar, that meant naming racial tensions and reframing negative feedback to prioritize the needs of Black students. For example, he taught the nineth-grade humanities course for a couple of years before realizing how isolating it was for the one Black student in the class to read novels like Walter Dean Myer’s Monster. Consequently, he proposed that all of the Black students in the entire grade should be in his classroom to prioritize their comfort instead of promoting the illusion of diversity across the classes. As a result, during the semester I observed Medgar’s classroom, he had all four Black first-year students in his class. This change in structure and school policy demonstrated that Medgar was willing to take responsibility for teaching all of the Black students.

Medgar also prioritized the safety and well-being of his Black students in his ethnic studies class. For example, in the first couple of weeks of the class, as the students started to dive into challenging discussions of race, the Black and white students, in particular, started to experience racial tension. Although there were no assigned seats, students began to habitually sit in the same places, with the three Black girls in the class at the farthest end of the circle away from Medgar and most of the white girls closer to him. In one lesson, a white student asked a question about cultural appropriation, and a few of the students at the back of the room started laughing, including two of the Black girls. Medgar noticed how this laughter caused immediate tension in the students near him, and he asked his students to reflect honestly on the class in the weekly feedback form. Consequently, eight out of the 18 students spoke directly or alluded to a racial divide that made white students uncomfortable speaking up or making mistakes.

In the subsequent lesson, Medgar openly named the tension between the racially minoritized and white students, leading to a deep whole class discussion. As the physical placement of the students (i.e., white students and Black students physically separated) was of evident concern to some white and Asian students, one student suggested that they try to mix up their seating in some way. Medgar responded to this suggestion by interrupting the focus on where Black students sat to point out the choices the non-Black students were concurrently making in the classroom. Medgar argued that “there’s absolutely nothing problematic about people of color sitting with each other. Yet it’s often perceived as a problem because it prevents the dominant culture often from integrating and understanding.” By highlighting this fact, Medgar modeled a rupture in anti-blackness to create more critical consciousness around placing blame and deficit thinking. He asked the students to reflect on why the focus was on where the Black and Latinx students were choosing to sit, even though the white and Asian students were making parallel decisions, yet those choices were not as visible in the same way.

As the students shared their experiences, Demi, one of the Black girls, spoke about why they had laughed when the white student asked about cultural appropriation—someone had made a joke about Youtuber Trisha Paytas. Demi clarified that she did not want white students to feel uncomfortable, but she wanted to stress that she constantly had to regulate her speech and facial expressions in her other classes. She appreciated that after experiencing harm in the class before, this class was a “release” for her. Medgar affirmed her thoughts by stating:

I appreciate that context, Demi, because I also want to name the fact that students of color at this school are often one of few in a class with a teacher who’s not like me that’s going to break down the tension. With a teacher that’s going to allow shit to be said [students snap] that is harmful and impacts them … students of color go through classes all day where they don’t feel safe … And so I want to honor the contrast that this class feels very different for a lot of students of color and Black students in particular at Golden Gate because, as you all know … I’m the only [Black] teacher in the whole damn building, right? That means something.

Medgar’s response to Demi demonstrated his desire to prioritize the comfort of Black students to create a brave space radically different from their traditional anti-Black classrooms. He highlighted that Black and other racially minoritized students could spend their entire day without feeling seen and that this space was fundamentally trying to be a space where they could feel safe. Medgar’s use of profanity and informal language underscores his intentional choice to be direct and relatable to his students, and it also invited the non-Black students to take a step back on their feelings of comfort to provide space for the Black students to show up more fully in who they are. In the subsequent weeks, I observed white students continuing to ask questions and Black and Latinx students articulating their needs more to the group. They did not change their seats, but there was a noticeable change of support when students chose to be vulnerable. If a student shared a personal story, the students would snap, nod their heads, or give the student a rub on the back if they wanted one. When I asked Demi how she felt about the course a few weeks later, she stated:

I already like, feel like a weight’s been lifted off my shoulders when I walk into [ethnic studies], specifically because I’m … It feels like I’m in a space where I can just not have to code switch constantly because the teacher looks like me and there are students in the class that I can relate to … And it just feels like I’m able to speak in African American Vernacular English. I’m able to actually share my truth and share things that have happened to me without feeling like I’m going to get backlash behind it.

Demi pointed out several components of BTP’s Black teacher fugitive space, where participants can draw on their full linguistic repertoires to communicate without worrying about ridicule or consequences. She appreciated that in this predominantly white space, she had a learning environment where people looked like her and could accept her for who she was. She walked away feeling like she could speak about her experiences without consequence, and this notion was a radical element for her. As Demi’s reflection demonstrates, Medgar prioritized Black students’ feelings to create a safe space for all students.

Influencing white consciousness

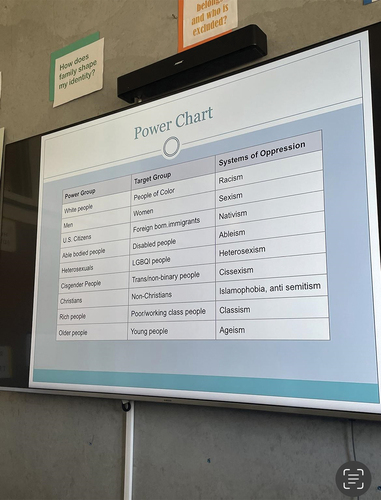

In addition to his focus on supporting Black students, Medgar said he needed to disrupt anti-blackness and educate white people who, as Medgar phrased it, would “not call the cops on us.” Medgar would do so by directly calling out issues of race when necessary. For example, in his Hip Hop class, after reviewing the agenda and the power chart (see ), Medgar stressed that an important takeaway from that day’s lesson was the role of intersectionality. Leo, a white male-identifying student, then raised his hand to ask about his own intersectionality. The following exchange ensued:

Leo: If I’m like … I’m just kind of confused about race and if I’m like … I’m a white cis straight male, would I just say I don’t experience any intersectionality?

Medgar: Oh. That’s a great question. … this is not the overall list [of oppressed identities] … It means actually there’s no systems working to oppress you happening simultaneously.

Leo: So for the last question, it was like, “Explain how much you experience,” but I’m … So I’m just confused about the phrasing. I said, in that, I don’t experience it, because I’m white. I don’t know. But yeah. So I don’t know. Is that correct?

Medgar: Yeah. That’s correct … This is something that comes up a lot with, for example, white cis-het wealthy Christians. Right? It’s not that you don’t suffer in this life. It’s not that there are not hardships. But it’s that those hardships aren’t because of systems working to oppress you … You were saying, “Do I have any intersectionality?” You do. You do, because you’re a multitude of things. But in terms of how Kimberlé Crenshaw came up with this, it was about oppression …

Figure 1 The slide Medgar used to teach about power and systems of oppression, (adapted from SOUL School Of Unity and Liberation, Citation2001, p. 31).

This exchange highlights a particularly vulnerable moment, where a white student felt comfortable enough to ask about his own identities and their contribution to systems of oppression. His questions highlighted his desire to understand his role and to self-reflect on how his multiple identities might provide him with privilege. This exchange also demonstrates Medgar’s willingness to confront often-taboo topics in schools, and his students were receptive to a different perspective. In his participant retrospection interview, Medgar stated that although he first prioritized Black and other racially minoritized students, he then prioritized “white bravery,” as he wanted his white students to be able to ask questions and reflect in community so that they could ultimately adopt mindsets that would disrupt anti-Black ideologies. He reflected that Leo’s question was an example of a brave question, and it was probably a question that other students had. Medgar created a space where all his students felt they could have truthful and challenging conversations about race and ask questions that would help deepen their understanding of how their lived experiences with race impact their engagement with the world.

In summary, Medgar used Black-affirming pedagogies to create collective learning environments where students could experience more wholeness of their humanity and build their racial literacies. Racial literacy is the capacity to read and respond to harmful racially influenced social interactions, and Stevenson (Citation2014) argues that “the teaching of racial literacy skills protects students from the threat of internalizing negative stereotypes that undermine academic critical thinking, engagement, identity, and achievement” (p. 4). In focus groups, students revealed that building racial literacy helped them feel like they could influence society for the better. For example, Margo, a white girl student, said that after taking two of Medgar’s classes, she has called out some of her friends for racially insensitive comments and is more motivated to learn about injustices and how to interrupt them.

When I asked Medgar if he thought his pedagogies were subversive, he noted that the current anti-truth political climate, with the conservative attempts to erase the history of Black suffering (and Black joy), made it particularly important for him to use fugitive pedagogies. He argued that Black teachers build students’ racial literacies as an essential antidote to these erasures. He replied:

Yes, definitely in this moment where AP African American Studies isn’t taught in Florida and there’s an attack on Critical Race Theory. So there’s almost like this intentional … whitewashing. It’s antithetical to racial literacy. So yes, I think I’m doing something a little bit different … but I do think that a lot of Black teachers are doing what I’m doing, that they’re trying to incorporate racial literacy for all of their students, which makes us so special and, I’m not going to say magical, it makes us so important to … this country, that we need to be … in greater number and also better supported and appreciated.

Medgar underscores how the anti-Black backlash that is whitewashing curricula across the United States necessitates subversive pedagogies. He argues that he is not alone in using fugitive pedagogies, as Black teachers are at the forefront of fugitive pedagogies no matter the subject. He argues that their pedagogies teach students to be critical and racially literate about the information they consume. He also asserts why, in this critical political moment, we must invest in more Black teachers to bolster the resistance against anti-blackness in schools.

Discussion

This article demonstrates how Medgar felt the BTP inquiry group, a Black teacher fugitive space, shaped his pedagogies. Riordan et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that students are most likely to experience equitable classrooms when their teachers have professional learning that focuses on learning about structural oppression and the pedagogies that will address those injustices in the classrooms. Medgar felt that the fugitive space of BTP supported him in learning to disrupt anti-blackness and enacting fugitive pedagogies, setting him free to use his Blackness to create safe and liberatory learning spaces for his students.

To better understand how fugitive pedagogies are in response to anti-blackness, I draw on BlackCrit as an analytical lens. Coles (Citation2023) describes that BlackCrit “offers a political analysis into Black life that creates an outlet to more liberatory Black futures, by disrupting the realities and technologies of anti-Black racism” (p. 449). Therefore, the theoretical framing of BlackCrit allows me to understand that even though anti-blackness is endemic to American society and schooling, Black teachers work to reveal and make known this structure, enabling the teachers and their students to co-imagine counter-structures. Therefore, these fugitive pedagogies offer us hope and a blueprint for co-creating Black-affirming educational spaces even when schools are places where Black children suffer (Dumas, Citation2014).

The lens of BlackCrit helped me to focus on counterstories that disrupt the dominant narrative of schooling. The story of Medgar provides nuance to the larger conversation of how Black teachers are navigating a teaching climate where what is being taught (and, in some cases, how it is taught) is under attack. As Medgar learned to embrace his whole self, appreciate his Blackness, and learn/perfect his pedagogies in a fugitive space, he brought this information back to his students. Medgar found ways to upend traditional schooling by removing the competition, focusing on the collective, and refusing to whitewash his curriculum. Teaching students about anti-blackness allowed them to see that what they witness and experience is not normal; instead, the stripping of Black and other racially minoritized folks’ humanity is intentional and predictable. In addition, when Medgar was not focusing on teaching racial literacy or how to closely read the lines of a novel, he was pumping joy into the classroom. Therefore, as an antidote to Black suffering, allowing students to express their multiple identities and experience joy was a deliberate and radical component of Medgar’s teaching.

Some fundamental tenets of fugitive pedagogy emerged from analyzing Medgar’s teaching. I suggest that, for Medgar, fugitive pedagogy included the following characteristics:

Creating a collective learning community. Medgar believed it necessary to create a supportive, community-based learning environment, so he made his pedagogical moves in service of the collective. He established a healthy community of care and trust through which he could break norms of individualism and competition that are rampant in a society built on colonial logics, capitalism, and exceptionalism. Medgar prized a sense of collective responsibility to care for each other and recognized that no one could learn in a space where they were not accountable for the impact of their actions.

Directly interrupting anti-blackness. Medgar directly addressed issues of anti-blackness and/or injustice in his teaching. He did so by openly calling out when there were poor racial dynamics between students and by teaching directly about anti-Black and systemic racism in his lessons. As a humanities teacher, he taught direct and unapologetic lessons on the legacy of chattel slavery and colonial logic, the social construction of race, Black-affirming theory. As teachers are often encouraged to be neutral in their political underpinnings, Medgar did not hide his sense of responsibility to interrupt anti-blackness in his classroom environments. In confronting displays of racial hierarchies and anti-Black behavior, Medgar actively created space for new possibilities in the classroom.

Centering Blackness. Medgar focused on centering the comfort and well-being of his Black students, and this centering did not appear to distance the non-Black students in his classes. Medgar pointed out that Black students often have to regulate their behavior, speech, and emotions in other classes, and he wanted to be a part of creating a space where they did not have to do so.

Prizing authenticity. Medgar appreciated learning how to show up more authentically himself, and he encouraged his students to do so as well. He appreciated that the BTP supported him in experiencing what it feels like to learn and contribute to an environment where he could “true speak” (hooks, Citation1989, p. 8). He asked students to share their thoughts at the beginning of the lessons through the whip-arounds and would occasionally use profanity to disrupt respectability politics and build connections with students. As a result, students in his class felt like they could share who they were without ridicule.

The youth’s feedback during my focus groups with them helped me to think about what Black teachers gain from fugitive spaces, and the tools and knowledge that make classrooms better sheltered from the suffering in schools. Medger’s pedagogies, which were inspired by this fugitive space, allowed the students to imagine and work towards a world they could feel proud to be a part of, demonstrating that there is perhaps a cycle of fugitivity that continues to help us co-construct Black-affirming structures in education.

Implications

Fugitive teaching becomes necessary in anti-Black climates, particularly when there is surveillance and control over the curriculum. As states across the United States attack Black Studies, it is becoming increasingly necessary for Black teachers, and any teacher who wishes to push against the anti-blackness embedded in schools, to teach fugitively. And the stakes are high—in some states, there are now consequences of job loss or lawsuits for teaching the truth about anti-blackness and students’ role in addressing it, which is why teachers like Medgar often do this work “under the cover of darkness.” And yet, Medgar and many teachers like him are teaching for the kind of world we are hoping for. As states continue to mandate the whitewashing of history and learning, we may very well see a surge of Black fugitive pedagogies. Nevertheless, these pedagogies and having to steal away for education have been the norm of Black education since enslavement, and teachers like Medgar are the latest cycle of that fugitivity. However, from the student interviews and observations, it is clear that these pedagogies are meaningful both for Black and non-Black students alike who are learning how to be a part of creating educational opportunities that will not require subversion to claim them.

Although studying fugitive education is an essential component of studying Black education, there is danger in considering fugitivity as a normative project. Fugitive education is not to be prized, nor is it the end goal (ross, Citation2021b; Smith-Purviance, Citation2023). Instead, it exists because the anti-Black world necessitates that it exists. I therefore hesitate to prescribe policy that would continue to normalize climates that are predicated on anti-blackness to bring out these inspiring Black teacher pedagogies. Instead, it is important for all teachers, Black and non-Black, to learn to understand and recognize anti-blackness, to learn to see. Once we learn to see, we can change our perspective of fugitive acts so we do not perceive them as threatening and therefore in need of policing. Instead, we can confront those who are misrecognizing the work of Black teachers and address the anti-Black climates that compel Black teachers to engage in acts of fugitivity in the first place. We can also prioritize policies that foster inclusive learning spaces that enable Black students and teachers to freely express the nuanced, evolving, and distinctly human dimensions of their learning experiences and aspirations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jessica Lee Stovall

Jessica Lee Stovall is an Anna Julia Cooper Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research sits at the intersection of Black Studies and education, and it addresses how Black teachers’ co-construction of fugitive spaces can provide us with a blueprint for innovative educational practices.

Notes

1. I use the term Black teacher pedagogies instead of a singular pedagogy to stress that Black teachers are not a monolith and that no one way of teaching can describe every Black teacher’s practice.

2. While much research reveals how Black teachers positively impact students (Blazar, Citation2022; Milner, Citation2006), it is important to note that Black teachers are not inherently best for Black students (Maylor, Citation2009) because they can also perpetuate anti-blackness due to the pervasiveness of institutionalized anti-Black racism and its impact on our lived experiences.

3. Except for Black Teacher Project, all names are chosen pseudonyms. Both the author’s institutional IRB and the participants consented to the naming of BTP.

4. I wanted to wait until the return of in-person teaching to be able to capture more of the embodied practices in the classroom.

5. I sincerely appreciate my research assistant Taylor Hall for this work. Your support was invaluable.

References

- Bell, L. A., Adams, M., & Griffin, P. (2007). Teaching for diversity and social justice. Routledge.

- Blazar, D. (2022). How and why do black teachers benefit students? An experimental analysis of causal mediation (Vol. 501). Annenberg Working Paper No. 22.

- Bonilla, Y. (2015). Non-sovereign futures. University of Chicago Press.

- Campt, T. (2014). Black feminist futures and the practice of fugitivity. Barnard Center for Research on Women. https://bcrw.barnard.edu/videos/tina-campt-black-feminist-futures-and-the-practice-of-fugitivity/Video.

- Coles, J. A. (2019). The black literacies of urban high school youth countering anti-blackness in the context of neoliberal multiculturalism. Journal of Language & Literacy Education, 15(2)

- Coles, J. A. (2023). Storying against non-human/superhuman narratives: Black youth Afro-futurist counterstories in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 36(3), 446–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2022.2035455

- Coles, J. A., Ohito, E. O., Green, K. L., & Lyiscott, J. (2021). Fugitivity and abolition in educational research and practice: An offering. Equity & Excellence in Education, 54(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2021.1972595

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The talented tenth. James Pott and Company.

- Dumas, M. J. (2014). ‘Losing an arm’: Schooling as a site of black suffering. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.850412

- Dumas, M. J., & ross, k. m. (2016). “Be real black for me”: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Education, 51(4), 415–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916628611

- Duncan, K. E. (2020). ‘That’s my job’: Black teachers’ perspectives on helping black students navigate white supremacy. Race Ethnicity and Education, 25(7), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1798377

- Foster, M. (1990). The politics of race: Through the eyes of African-American teachers. Journal of Education, 172(3), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205749017200309

- Givens, J. R. (2021). Fugitive pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the art of black teaching. Harvard University Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Gregory, A., & Weinstein, R. S. (2008). The discipline gap and African Americans: Defiance or cooperation in the high school classroom. Journal of School Psychology, 46(4), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.09.001

- Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning and black study. Autonomedia.

- Hartman, S. V. (1997). Scenes of subjection. Oxford University Press.

- hooks, b. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black (Vol. 10). South End Press.

- Irvine, J. J. (1989). Beyond role models: An examination of cultural influences on the pedagogical perspectives of black teachers. Peabody Journal of Education, 66(4), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619568909538662

- Jacobs, J. K., & Morita, E. (2002). Japanese and American teachers’ evaluations of videotaped mathematics lessons. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33(3), 154–175. https://doi.org/10.2307/749723

- Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

- Madkins, T. C. (2011). The black teacher shortage: A literature review of historical and contemporary trends. Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 417–427.

- Martínez, R. A. (2010). “Spanglish” as literacy tool: Toward an understanding of the potential role of Spanish-English code-switching in the development of academic literacy. Research in the Teaching of English 45(2), 124–149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40997087

- Mawhinney, L., & Baker-Doyle, K. J. (2023). Nurturing “A specific kind of unicorn-y Teacher”: How teacher activist networks influence the professional identity and practices of teachers of color. Equity & Excellence in Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2022.2158397

- Maylor, U. (2009). ‘They do not relate to Black people like us’: Black teachers as role models for Black pupils. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802382946

- McKinney de Royston, M., Madkins, T. C., Givens, J. R., & Nasir, N. I. S. (2021). “I’ma teacher, I’m gonna always protect you”: Understanding Black educators’ protection of Black children. American Educational Research Journal, 58(1), 68–106. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831220921119

- Milner, H. R., IV. (2006). The promise of Black Teachers’ success with Black students. Educational Foundations, 20(3–4), 89–104.

- Mitchell, A. (1998). African American teachers: Unique roles and universal lessons. Education and Urban Society, 31(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124598031001008

- Patel, L. (2016). Pedagogies of resistance and survivance: Learning as marronage. Equity & Excellence in Education, 49(4), 397–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2016.1227585

- Rampton, B. (2003). Hegemony, social class and stylisation. Pragmatics, 13(1), 49–83. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.13.1.03ram

- Riordan, M., Klein, E. J., & Gaynor, C. (2019). Teaching for equity and deeper learning: How does professional learning transfer to teachers’ practice and influence students’ experiences? Equity & Excellence in Education, 52(2–3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1647808

- ross, k. m. (2021a). Black space in education: Fugitive resistance in the afterlife of school segregation. In C. A. Grant, A. N. Woodson, & M. J. Dumas (Eds.), The future is Black: Afropessism, fugitivity, and radical hope in education (pp. 47–54). Routledge.

- ross, k. m. (2021b). On black education: Anti-blackness, refusal, and resistance. In C. A. Grant, A. N. Woodson, & M. J., Dumas (Eds.), The future is black: Afropessimism, fugitivity, and radical hope in education (pp. 7–15). Routledge.

- Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press.

- Siddle Walker, V. S. (2000). Valued segregated schools for African American children in the South, 1935-1969: A review of common themes and characteristics. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 253–285. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003253

- Smith-Purviance. (2023, April 13th-16th). The spatiality of black girlhood and educational fugitivity. [conference presentation]. In Critical approaches to place-based inquiries in black education. [symposium]. Krysta Evans (Chair) (ed.), American Education Research Association.

- Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103

- SOUL School of Unity and Liberation. (2001). A school to build a movement political education workshop manual. https://www.schoolofunityandliberation.org/

- Stevenson, H. (2014). Promoting racial literacy in schools: Differences that make a difference. Teachers College Press.

- Stovall, J. L., & Mosely, M. (2023). “We just do us”: How black teachers co-construct black teacher fugitive space in the face of anti-blackness. Race Ethnicity and Education, 26(3), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2022.2122424

- Thompson, O. (2022). School desegregation and black teacher employment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(5), 962–980. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00984

- Tillman, L. C. (2004). (Un)intended consequences? The impact of the Brown v. Board of Education decision on the employment status of black educators. Education and Urban Society, 36(3), 280–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124504264360

- U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Institute for Education Services, National Center for Education Statistics.

- Valdez, L., & El Teatro Campesino. (1990). Luis Valdez early works : Actos, Bernabé and Pensamiento Serpentino. Arte Público Press https://www-digitaliapublishing-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/a/40224.

- Vargas, J. H. C. (2006). Catching hell in the city of angels: Life and meanings of blackness in south central Los Angeles (Vol. 57). University of Minnesota Press.

- Wynter, S. (1989). Beyond the word of man: Glissant and the new discourse of the Antilles. World Literature Today, 63(4), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.2307/40145557