ABSTRACT

This paper examined how an HSI-STEM grant project at one such college responded, confronting challenges of the transition to an all-online environment head-on and tapping its unexpected benefits. With a focus on STEM student services and programs, two aspects of the situation are analyzed and studied. Facilitating Innovation: STEM administrators had to think outside the box and employ extra effort to continue providing support services such as Supplemental Instruction and Counseling Services to ensure success for their students. We attempt below to identify key issues and obstacles met along the way and how they were addressed: How did peer Supplemental Instruction (SI) Leaders, trained for a classroom setting, modify their approach and engage students through virtual-classroom-supplemented instruction? How did academic counselors incorporate non-verbal communication and document-sharing in their outreach and interaction with their students? How did faculty and staff guide two-year-long student research projects during the pandemic? What sort of challenges did they face and how were they overcome? Looking Ahead and Moving Forward: What started as a shocked reaction in the face of a dizzying crisis had to be transformed, and urgently, into an effective, necessity-dictated response in service of continued STEM teaching-and-learning advancement. Some of the changes adopted through the pandemic may now be pleasantly irreversible. What impact did access to, and experience with, online educational technology has on existing learning processes and support systems? How effective these efforts were? What are the long-lasting effects of implemented change on traditional ways of doing business?

Setting and context

Broader context

Online education or distance learning has been a growing component of the higher education scene for several decades, ranging from a single course to complete online universities. According to the Babson Survey Research Group, about 33% of college students have taken at least one online course (Lederman, Citation2019). While the technology has been readily available, the shift to fully integrate it into teaching and learning has been a slow undertaking – one that is not consistent across academic disciplines, especially in the STEM arena.

Unpredictably, COVID-19 provided a strong impetus for speeding up knowledge-delivery and skills-building processes through e-learning platforms. Responding to external conditions of lockdown, heightened anxiety, and institutional inertia, most institutions of higher education had no choice but to adopt and implement online delivery of instruction for nearly their entire academic programs. In March 2020, when the pandemic forced a pattern of complete physical closures, resistance gave way to innovation and positive outcomes.

Among educational institutions, all of which were affected, community colleges were uniquely challenged during this period. Considering their limited budgets and vulnerable dependency on their counties, which were themselves constrained and negatively impacted by the pandemic, college leaders had to be resourceful and mobilize the full collaboration of their faculty and staff.

Re-envisioning, redesigning, and transforming the technology infrastructure to support a diverse student body require serious capital investment and retraining. Staff and faculty at community colleges made substantial efforts, utilizing resources available to them, to turn remote-learning activities into valuable experiences for students. They had to support the success of traditional and non-traditional students, as well as degree- and non-degree-seeking students, while keeping students’ overall well-being in mind in the face of COVID-19.

Local setting

In this paper, we discuss and qualitatively analyze the effects of pandemic-motivated policy and process modifications made at Bergen Community College (BCC) in Northern New Jersey. Our focus is on COVID-activated response through a large Hispanic-Serving Institutions’ STEM grant initiative, the STEMatics project, whose aim is to enhance student persistence and success. The Hispanic-Serving Institutions Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (HSI-STEM) and Articulation Agreements is a Title III-Part F program funded by the U.S. Department of Education to increase the number of Hispanic and low-income students attaining degrees in STEM and strengthen transfer and articulation activities between two-year and four-year institutions in STEM fields. STEMatics was hit by the pandemic a year before its completion. We assess measures taken and changes adopted by project staff and college leadership, individually and collectively, and how students adjusted and responded to these measures.

Our external evaluation reviewed operational progress and project outcomes, a process that had to be reconceptualized because of the crisis. The population studied represented approximately 2,000 STEM majors served by the grant through 11 different activities to support student academic development and timely graduation, from comprehensive counseling to learning assistance and research engagement. We analyzed the state of every activity during the pandemic and paid attention to how students and staff reacted, adapted, and might have seized the opportunity of the crisis to bring about change and sustain it. We looked at the pace, nature, and depth of adaptability. As an example, we analyzed what worked for most students, how their perceptions of online learning changed, how they experienced the loss of social interaction with other students, and what it all meant – for both students and faculty/staff and the overall project.

A Pre-COVID baseline | student challenges

In our evaluation approach, we asked students about major challenges they face in pursuit of their college education. Throughout the grant period, the issues most cited were time management, work–life balance, making transition from high school to college, and dealing with the pressure to complete a large suite of STEM courses’ prerequisites. During an interview in the spring 2020, a student expressed, “work–life balance, time management, responsibilities of family are some of my main issues. I work about 15–20 hours per week. It gets very difficult sometimes.” Another student during the same interview added, “Learning new topics every day is a challenge in itself, sometimes it is how to focus on information, it is hard, when you have so many courses and there is a lot to take in.” A third student shared with us, how struggle to get organized, “I am taking six classes this semester and I am in three clubs, time management is critical, I have to use a planner and a google calendar to get organized.” For international students, added challenges included language barriers, communication, and navigating the U.S. educational system. An international student mentioned, “language is a big barrier, it’s hard for me to communicate, academics are hard. STEM program people were accepting and non-judgmental.”

Members of the STEMatics staff and college administrators involved with the project (including grant administrators; the Dean of Mathematics, Science and Technology; and the Principal Investigator), were also interviewed to examine college/division-wide challenges and experiences during COVID-19. Additionally, the Evaluation Team gathered quantitative data to assess how the administration’s combined efforts affected student retention, graduation, and transfer during the two and a half COVID-19 semesters.

A Pre-COVID baseline | staff challenges

In normal times, STEMatics staff commonly looked for innovative ways to publicize support services available and stay connected with students, which meant maintaining constant two-way communication, tracking students’ academic progress and life stressors, and scheduling appointments for counseling or tutoring and ensuring that students show up as planned.

Impacts of COVID-19

College closure and the transition to online instruction presented uncharted challenges to students, faculty, and staff. In interviews with students, we explored how they transitioned from a physical classroom to a virtual learning platform; whether and how they had to adjust in terms of being fully present, taking notes and studying individually or in teams, and getting help. We also inquired about how the online environment for instruction and participation in other college activities including STEMatics influenced their social interactions and sense of belonging to an educational community.

Non-traditional students, with work and family obligations, welcomed the opportunity to take classes online. Given that many of their classes were offered in an asynchronous mode, students were able to participate in their courses’ session when it fit their schedule. Other students with family obligations, such as having to care for children staying at home due to the pandemic, found that the scheduling flexibility of asynchronous courses allowed them to continue their education. It was clear that, for all students, not having to travel back and forth to campus for classes was a significant time- and cost-saving. Overall, online classes had a positive impact on the challenges of work–life balance for these students. A student interviewed in the spring 2021 explained,

Grabbing elements of time between, school, work and family commitments has always been a challenge for me. Sometimes I work till late nights to finish my course work. I work 40 hours a week, I am a part-time student. Opportunity to take online classes, has given me flexibility, I have more time now to finish everything.

Yet, it has to be noted that, for a vocal minority of students, the home-learning environment caused undue distractions and placed additional demands on their time because of COVID-19 related homeschooling and other family responsibilities.

On student–faculty interactions

For students in asynchronous classes, the inability to interact in real time with their professor was considered a major shortcoming. They noted that not being able to ask questions at a critical point in a lecture and get an immediate answer limited their understanding. Follow-ups with e-mail did not appear to be as satisfactory and, by their nature, were not in real-time either. Students also missed the presence of other students, which they came to realize was conducive to the learning environment.

Unevenness in the utilization of technology in the delivery of instruction across courses appeared to be another concern for students (how technology was to be incorporated to ensure uninterrupted teaching flow was not prescribed; rather, it was left to the discretion of instructors). On one end of the spectrum, some classes were conducted with only static documents shared and e-mail-based communication; on the other end, there were synchronous classes offered that allowed for stronger student–faculty interactions and graphics communications and document-sharing live.

On student–student interactions

Lack of student–student socialization, as revealed in our interviews, had a significant negative effect of COVID-19 for traditional-age (18–24 years old) community college students. These students felt the loss of in-person contact with other students in the classroom, the absence of naturally formed study groups, informal social connections (coffee in the food court), and, in some cases, just the physical environment of the college (from going to the library to hanging out between classes). To some extent, students utilized existing social media apps to connect with college friends and identify classmates, whereas non-traditional students who were interviewed expressed almost no change in their student–student socialization. One student mentioned, “I am retired; I am attending college because I want to learn; most students in my classes are younger than me and I don’t socialize with them.”

On student–staff interactions

Unlike weakened one-on-one interactions with faculty around classroom activity, which had to be replaced by e-mail communications and the significant time lags it carries, students seemed to have maintained a reasonably adequate connection with staff members engaged in counseling, supplemental instruction, and research as was highly evident in our interviews. This turned out to be the case despite the observation that STEMatics staff struggled to provide timely and required services to the STEM students during the pandemic. After all, the pandemic hit in the fourth year of a five-year grant period; it was a race against time to fulfill all grant deliverables. Service-delivery methods had to be redesigned and resources secured to help students with hardware and software needs. Initial months were exhausting for the entire team, especially as the number of e-mails exchanged skyrocketed.

Actions taken

Leadership and funding

A significant characteristic of the project is the synergy that exists between its program components. The cohesion of the STEMatics staff and the project’s components has been instrumental in developing a sense of community among STEM students, which is a key factor leading to success in terms of both retention and graduation during previous grant years. Sustaining the student community and providing continued support for academic success during COVID-19 times were the greatest priorities for STEM leadership. The STEMatics HSI-STEM grant from the U.S. Department of Education (#P031C160154) is at a level of approximately one million dollars per year. In contrast to college funding, this source is fixed for the grant period and is generally not subject to change, providing greater flexibility than academic departments and divisions to adjust to the COVID-19 environment. The grant administration is a highly focused system with a more direct path to decision-making and reduced operational inertia. One of the beneficial responses to COVID-19 was the implementation of online tools for document management, budgeting, purchasing, and approvals. These changes have been beneficial in allowing STEMatics, as well as all college users, to respond more quickly and complete all sorts of transactions in a relatively speedy manner.

Implementation of student services

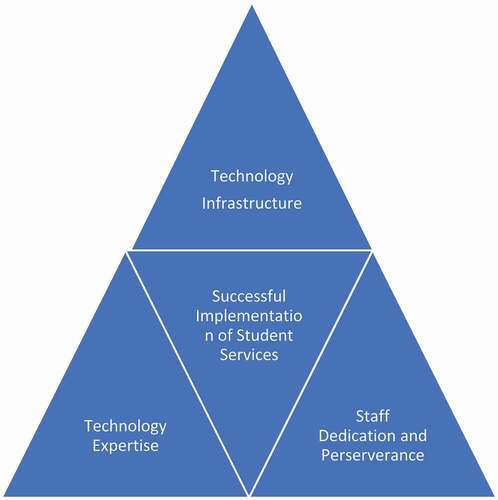

The successful implementation of online instruction and student services should use technology to enhance and not hinder student success (Terada, Citation2020). The STEMatics transition of student services from in-person to online depended upon three elements being in place: 1) institutional technology infrastructure; 2) expertise and experience in the use of educational and communication technology (technical preparedness); and 3) staff dedication and willingness to provide the extra effort to innovate and apply methods for student success (staff resourcefulness). This triad for success is illustrated in the diagram that follows ().

Institutional technology infrastructure

STEMatics benefited from a high level of systems’ readiness. In addition to the existing learning management system, e.g., Moodle for the online course material delivery, the college decided to adopt WebEx as the default platform for virtual instruction and meetings and scale its use. A standard interface made the transition process much simpler as students did not have to deal with different interfaces for different instructors or departments. This allowed students to move between classes and STEMatics activities with ease. Google Suite was adopted and applied for document-sharing, scheduling, and data management. During the early phase of closure, it was important to ensure that students had adequate devices for accessing the courses for which they were registered and availing themselves of the support services critically needed, even more so during the pandemic, for their success. Laptops were made available for lending by STEMatics working closely with other departments of the college.

Technological expertise

In general, the staff had been technologically prepared. As a matter of practice, the STEMatics grant project had embraced various forms of technology to support its mission. Recognizing that students engage better with technology environments that they accept and with which they are comfortable, the staff had invested in cutting-edge technology, which was scalable during the pandemic. This was facilitated by the staff’s adaptability and willingness to explore the latest software platforms, embracing what students are comfortable with, i.e., social media and mobile applications, such as Slack and Band App.

STEMatics staff had experience with project applications serving the STEM student population, including OER, a system providing free online textbooks and educational resources for STEM students. Since its inception, STEMatics has supported faculty members in the development of add-on materials (e.g., lab resources that are easily accessible), linked the local system to nationwide STEM resources, and motivated the creation of JOLT (a locally designed Just-in-Time Online Learning Tool), which evolved over the grant period. JOLT has reached a mature stage as a major tool for the delivery of STEMatics-specific contents, such as synchronous SI sessions. The value and timeliness of JOLT were validated by additional Department of Education funding in 2020 to support JOLT development and to provide loaner-hardware to students.

The STEMatics readiness of the counseling program illustrates the significance of planning and building technical expertise over time in ensuring a successful transition to online operations. Counselors were able to assess student’s technological and learning needs and were quick to adopt WebEx, which can be readily personalized and is seen as very user-friendly, for routine student-staff meetings and communications, making it a consistent interface with the college overall. This allowed for routine business as well as creative applications, such as the weekly round table conducted by the project director and the Q&A counseling sessions. Google Forms were quickly employed to register and track students for various activities.

Staff dedication and perseverance

Readiness of systems and technical preparedness of staff aside, the STEMatics staff have exhibited a high level of commitment to finding solutions toward adequately sustaining both the pre-COVID scope of support services and the depth of the teaching-and-learning exchange. Coordinators of each project component had to resourcefully apply technology that best served the needs and objectives of their activity. The motto of the counseling staff “experiment, optimize, and move forward” best exemplifies the spirit of the STEMatics staff to find creative and innovative solutions. Working long hours, the staff developed new methods to schedule and connect both synchronously and asynchronously with students, transitioning to 100% online within 2 to 3 weeks after the COVID-19 closure.

The continuous efforts of the staff, with guidance and support provided by the administration, led to a sustainable process. E-Mails, phone calls, and WebEx meetings have become the new norm for student-staff communication and meetings. The willingness of staff college-wide to adapt to changing demands and student needs is essential to sustaining the innovations developed in response to the Covid-19 crisis, or any crisis for that matter.

STEMatics response to COVID-19 – what worked

Academic counseling

The STEMatics academic counselors are engaged to assist students not only with scheduling, academic progress, graduation, transfer, and career-related queriesbut they also offer guidance, quite importantly, in the face of unexpected life challenges that hinder a student’s success. Academic counseling is, by and large, based on personal connections, and the rationale for the Covid-19 world was to maintain that personal, one-on-one relationship between student and counselor. Students develop a special rapport with their counselors, which is often based on trust and connectivity. One student stated, “counseling made me more confident and assured about my academic path and future STEM career plans.”

The STEMatics counseling staff consists of three counselors, who are active in outreach and intervention. Spring 2020 COVID-19 closures forced the counselors to respond with a cannot-fail-to-move-forward philosophy. This resulted in a full range of counseling services available online during the campus closure. When interviewed in the spring 2020, the counselors noted that the most noticeable issues included lack of technology for students and counselors’ inability to “see” their students during online meetings (many did not have cameras or would not turn it on), taking away the benefits of reading non-verbal clues, a factor in ensuring message delivery and personal connection. Other issues included being overworked, having been inundated with e-mails from students, staff, and administration, and never-ending one-on-one phone calls and WebEx meetings.

When interviewed again a year later in the spring 2021, the counselors noted that their concerns had been addressed on all levels. Most of the challenges that they identified in the spring of 2020 were resolved. To elaborate, a select list of solutions they managed to implement follows:

Q&A videos, accessible via YouTube covering such topics as resume writing and interviewing techniques, and hour-long weekly open Q&A sessions using WebEx.

Using WebEx capacity to display and share documents, and hosting video counseling sessions as applicable for students.

Using Google Forms to manage student information including their unique advisement needs and organizing them in an online database.

The implementation of Google forms allowed counselors to access the database and connect students with an appropriate counselor depending upon their individualized needs. In turn, the counselors would reach out directly to their students via e-mail to initiate services. The use of virtual meetings and phone/e-mail consultations with the academic advisors opened new doors of success for many students, especially non-traditional students who were juggling their schedules among academics, work, and family demands. Tasks that appeared unlikely in the beginning proved to be more efficient for both sides and effective at providing the support needed – and connectedness. Students proved to be prepared, with required documents at their fingertips, hence reducing the need for more than one appointment per student. One student commented, “I now have a [new] relationship with my counselor. I just send an email and we set up a time to meet online with WebEx.”

The effort led by the STEMatics academic counselors encouraged the College’s Academic Success Center to analyze and replicate the forms and processes used. The success and popularity of the effort have encouraged the administration and counselors to modify the working hours of all the counselors to accommodate virtual access for students in fall 2021, when the institution expects to be fully functional and in-person on campus once again.

Supplemental instructions (SI)

SI had a well-developed pre-COVID-19 system for a twice-a-week regimen of parallel-classroom instruction by well-trained SI Leaders who were mostly high-academic-performing peer students. The scheduling of these sessions was determined through the solicitation of student input regarding the best time to meet. All sessions were taught in person by the SI Leaders. With the advent of COVID-19, the SI program remained committed to direct leader-student contact by utilizing WebEx to provide synchronous sessions. Students logged in at their assigned time and worked interactively with their leaders. One student noted, “It really helped me out; my leader was very helpful at going over problems.” Students seemed to be quite satisfied with their SI experience during COVID-19 and saw positive benefits on their academic performance in the courses.

Before the COVID-19 closure and move to online instruction, the SI team was working on “Virtual SI,” which was to be an online mode of SI that would give students more flexibility in attending the sessions with the advantage of increased participation. This was a proactive move to utilize technology to respond to student needs and improve the delivery of SI. Such readiness helped the SI staff at BCC transition almost immediately to a quick and reliable virtual communication setting in March 2020. The SI team created Google Drive folders for all SI leaders for spring and summer semesters, which allowed them to share all the planning sheets and important updates. The team used the college-wide adapted WebEx Meet to hold the live virtual SI sessions. This transition was smooth for most of the students as WebEx was the standard platform at BCC, allowing students to participate in the SI sessions using cameras, microphones, whiteboard, and chat, among other tools. Students found their SI leaders to be “very good, knowledgeable, and focused on my problems and issues.”

It was observed that the SI program at BCC not only remained effective but expanded its outreach to other subject areas within the STEM domain during the pandemic to support student success. An analysis of student performance data showed that in 2020–2021, SI students continued to achieve higher grades and there were fewer failures and withdrawals compared to their classmates who did not participate in the SI sessions. One student was asked if the virtual SI sessions worked and responded, “Yes, I was helped by the leader on homework, better than asynchronous classes where you couldn’t ask the professor questions.”

As an example, the flexibility students gained to virtually meet their peer SI leader in a variety of STEM courses or get rapid responses to their questions from their financial-aid advisor or STEM counselor significantly increased their access to learning assistance and enhanced coping skills, as compared to pre-COVID-19 access. Online access to the sessions provided schedule flexibility for non-traditional and working students, who were not able to attend these sessions despite the need when the sessions were in-person only.

Student research

Student research at the community college level plays a significant role in promoting access, equity, and diversity in STEM education (Hewlett, Citation2018), and was a priority activity for continued support in the COVID-19 environment. The STEM student scholar program (3SP) connects students and faculty for summer research activities throughout two summers. 3SP students work with faculty, publish their research, and showcase their research at an annual research conference held at BCC by the STEMatics program. This conference is attended widely by other community college students, faculty, and staff, as well as industry partners and 4-year universities. Students and faculty receive stipends to work on their research projects, funded by STEMatics. Participation in 3SP has prepared students to transfer successfully to four-year colleges of their choice.

The COVID-19 closure impacted faculty communication and the ability to work in the physical student research center established 2 years prior. Yet, the work seemed to have proceeded uninhibited. When it came to 3SP faculty members, who work as research advisors and are involved with program operations, student selection, and teaching a series of research-learning short courses, they continued their engagement through a seamless transition using WebEx.

The hands-on and teamwork approach to research required creative approaches in an online environment. Faculty and students connected using a variety of communication apps, principally Slack. They were able to complete their summer projects with modifications to adjust to the lack of physical access to the STEM student research lab. Some projects were completed by maintaining social distancing and working in smaller groups or individually on various tasks involved, while others were modified to fit an online environment. The following is a partial list of research topics completed during COVID-19, along with the modified approach employed by students and faculty members in response to restrictions.

Creating a Python website to calculate chemical compounds and show long pairs. (Online participation)

Experiments with ethical hacking, using a variety of communication tools, such as Slack and Discord (online project exclusively)

Quantum computing (online only)

High-altitude balloon project (required in-person use of the STEMatics student research lab subject to CDC established guidelines)

COVID-19 Epidemiology (online only).

The completion of the summer research program represented a reasonable model for how technology can support student collaboration and communication in a remote distributed environment. Some of the notable outcomes as mentioned by students who were interviewed include teamwork, overcoming scheduling issues, and learning more flexible communication tools and team management skills. At least one student participated in the research from Israel, illustrating the ability to collaborate on student research even in different time zones.

The success of 3SP during COVID-19 has provided a framework for involving more students in the research activities at BCC in the coming semesters. Until now, only a small percentage of qualified STEM students were able to participate in this program due to a lack of human resources and time management.

What did not work well

Although the STEMatics project was able to provide a robust STEM support system for the success of students at BCC during the COVID-19 year, certain academic issues remained a challenge for students, faculty, and staff.

One of the biggest challenges faced by students and faculty regarding their online STEM courses, which could not be addressed by the STEMatics team, primarily because it was beyond their locus of control, was the associated lab component. It was quite a challenge for faculty to provide the optimal experience for Physics, Biology, and Chemistry labs in an online environment, as compared to Computer Science or Information Technology faculty. Faculty had no training or resources for online labs; students expressed their discontent for not having “hands-on” experience in lab courses. One of the students expressed it this way: “Lab course in chemistry – video of the lab and then fill our experiment sheet – it’s OK, but I don’t have hands-on experience.” Counselors expressed their concern regarding the transferability of the lab courses taken by students during COVID-19.

Another important theme that emerged from the student interviews was some dissatisfaction regarding both quantity and quality of course materials delivered in various sections of the same asynchronous course. Students mentioned the impact of ‘limited’ or ‘no’ correspondence with the professors of their asynchronous courses on their overall achievement in the course. One of the students mentioned that, “it is easier for the time management, no travel, no set time for the classes; but in asynchronous classes, there is no way to ask questions.” Another student asserted: “I don’t like asynchronous classes as I miss the learning that happens during the live interactions with other students in class.” Yet another student stated, “Talking to a screen did not do much good, I cannot ask questions and it limits my understanding, not having classmates to discuss things is difficult.”

Social interaction and connectedness are viewed as essential to student success (Jorgenson et al., Citation2018); yet, many students felt that their connection with the professors and fellow students had been lost during the COVID-19. A student expressed his concern by stating, “The connection between students and professor has been lost in COVID-19, in normal times I try to connect with my professors during their office hours, by simple walk-ins, which is now not a possibility.”

Students appreciated the flexibility in their schedules that they achieved via online classes; however, the disadvantage of staying home included distractions and not having a quiet space to study, and lack of access to library resources was noted by many students in their interviews. Non-traditional female students indicated that their responsibilities had increased during COVID-19. One of the students had to constantly take care of her toddler son during the interview, as she could not have any other help because of COVID-19 restrictions.

The College and the STEMatics team secured access to hardware for students at the beginning of the pandemic; however, issues of inequity around internet connections (access and speed) and availability of smartphones (for social media connectivity) may have played a role in limiting students’ ability to participate in the online learning environment. Also, a wide variability in course materials and delivery of instruction were frequently cited by students as a concern. These issues, which transcend Bergen Community College and the STEMatics project, require attention and need to be addressed in order to ensure full student engagement.

Lessons learned

As is the case with every crisis, this pandemic offered a series of valuable lessons around why institutions of higher education ought to invest in the latest available technology and adopt it to the extent possible to advance teaching and learning. There is little doubt that, post-COVID, higher education will look and feel very different from (and, in some ways, more evolved than) its pre-COVID counterpart. This applies not only to curriculum/program delivery but also to student engagement in learning.

The pandemic affirmed to many colleges, Bergen Community College and its STEMatics project among them, that the following observations could be capitalized upon moving forward:

The advantages and conveniences that online (asynchronous) courses offer students can no longer be ignored. However, approaches to address the resulting, more restrictive faculty-student communication must be considered.

The scheduling of multiple, online real-time learning-assistance sessions, such as SI, makes it possible for students who otherwise would not opt to attend or seek to fit such sessions into their schedules if they faced limited choices. In addition, the vast resources available online in support of any undergraduate STEM course (static materials and video segments) ought to be seized upon as supplemental materials to enhance learning. It is no longer necessary to reinvent or even customize teaching-support resources. What is still needed is a live person on the other end of the connection.

Members of the staff with technology experience are more readily able to implement and experiment with a variety of approaches in preparation for unexpected challenges, especially when it comes to maintaining strong linkages with their students. This calls for staff on the frontlines to be trained in technology that students use and with which they are most comfortable.

One of the challenges of the teaching process during the pandemic was the absence of clear guidelines, standards, and measurements in the online environment. There may be a great deal for campus-based colleges to learn from virtual-only universities around accountability for students and staff.

Students still expect in-person social interaction with other students and faculty as part of their educational experience. This is not an issue faced only by colleges; yet, it stands as a reminder that learning is as much a social as a solitary activity.

To respond to rapidly changing external forces, academic departments and divisions need greater fiscal flexibility in navigating a preferably reduced bureaucracy for purchasing, making student-focused decisions, and supporting professional development – all of which has to be balanced, of course, with process integrity and established controls.

Closing commentary and summary

As one of the myriad examples in the student-services domain, STEMatics at BCC has, since its inception, invested in technology to create a sustainable, remote support-services model for the college, which was brought to scale across other departments and institutions. The project had the required technology already in place, but it was not fully tapped at the time to shift its in-person activities online during COVID-19, fully and fairly rapidly. Aside from having built the technology infrastructure, the STEM project had established an environment through which its staff and faculty could be technically ready and committed to ensuring that student-focused activities, from counseling and supplemental instruction to student engagement in research, continued with little or no disruption. By first fulfilling the hardware and software needs of the students through a lending program and online technical training, staff customized the support to students and facilitated a smooth transition to a new mode of teaching delivery and student participation in learning.

Many challenges in the STEM arena remain to be addressed as institutions plan to reopen in fall 2021, among them:

Examining plans to support the working and non-traditional students who are now more comfortable attending classes remotely

Addressing how to stop and turn around a two-semester consecutive decline in student enrollment in general, and within STEM in particular

Exploring which facets of teaching/learning technology are needed and must be incorporated in the post-COVID era and, more importantly, generating related implementation plans

Addressing professional development among faculty and staff to remain ahead of the technology curve

Ensuring quality of learning outcomes and accountability for online vs. in-person instruction.

When considering the various lessons learned in a larger context, it appears that COVID-19, despite all its tragic consequences, may have given colleges and universities the non-negotiable incentive to use technology in ways unprecedented. The technology had been around and under-utilized – all that had to shift under COVID-19. Such a reality is here to stay and colleges will have to make a strong case for the in-person programs they offer and high overhead expenses that have driven the price of tuition way ahead of living-cost adjustments.

The broad implementation of online instruction in the COVID-19 era has opened a new arena of competition for higher education across geographic regions and institutional types. This issue will have to be seriously confronted in the years ahead. Colleges will have the potential to attract students both nationally and internationally; they can offer selected, quality specialized programs that will succeed because of a broader enrollment base.

Maintaining online instruction will appeal to a larger community of students, which may result in improved retention, shorter times to graduation, and a more diverse student body – if strong learning outcomes can be assuredly sustained. Students will have greater latitude in considering educational options as they relate to employment and careers, especially now that short courses and certifications can be delivered much more efficiently than had been previously the case.

References

- Hewlett, J. A. (2018). Broadening participation in undergraduate research experiences (UREs). Life Sciences Education, 17(3). Www.Lifescied.Org.https://www.lifescied.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-11-0238

- Jorgenson, D. A., Farrell, L. C., Fudge, J. L., & Pritchard, A. (2018). College connectedness: The student perspective. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 18(1), 75–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v18i122371

- Lederman, D. (2019). Online enrollments grow, but pace slows. Inside Higher Ed. Www.Insidehighered.Com.https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/12/11/more-students-study-online-rate-growth-slowed-2018

- Terada, Y. (2020). High-impact, evidence-based tips for online teaching. George Lucas Educational Foundation. Www.Edutopia.Org.https://www.edutopia.org/article/7-high-impact-evidence-based-tips-online-teaching