The manipulation debate

In the current regulatory environment of the United States of America (USA) there is ongoing debate and battles fought over manipulation, involving primarily the Chiropractic (DC) and Physical Therapy (PT) professions, but also Medical Physicians (MD) and Osteopaths (DO) [Citation1]. Examples for PT include the current need for a special endorsement in the state of Washington to utilize manipulation, the need to differentially diagnose in Indiana, a requirement for medical referral in North Carolina, prohibition of using the term ‘manipulation’ in California and Florida, and conflicts between state practice acts for physical therapists and chiropractors in many states. Though not as frenetic as the heated legislative battles of the 1990s, the debate continues and is frequently based upon the presumption that physical therapists need to defend their use of manipulation, which is primarily represented in the USA as a chiropractic invention and characteristic of chiropractic practice [Citation2].

A fresh and informing perspective to view this current debate is to step aside from a turf-based approach and dive deeper to understand what drove multiple professions to develop and provide manipulative interventions as part of their practice in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century [Citation3,Citation4]. Developing a better understanding of the genesis of manual and manipulative treatments within the PT, DC, DO and MD professions would allow these occupations to look at current debates from a less defensive standpoint but rather from a perspective of informed inquiry that would potentially support shared utilization of manipulation.

Manipulation: historical perspective

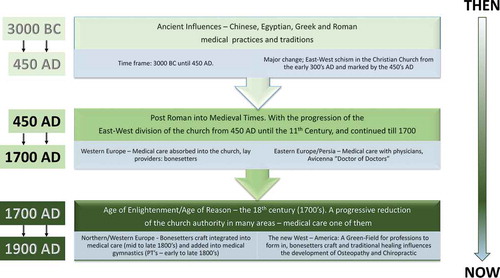

The utilization of manipulative treatments to address human ailments extends back at least 2500 years in Europe, and up to 5000 years worldwide [Citation5–Citation7]. Narratives on the use of manipulative therapy typically address treatments provided in the times of ancient Chinese practitioners, Egyptian interventions, Hippocrates (Greek) and Galen (Roman), and then in the European historical realm by bonesetters from the 1200s up until the nineteenth century [Citation2,Citation8–Citation10] ().

These narratives are typically framed to represent new discoveries in hands-on treatments such as by DD Palmer who founded Chiropractic in 1895 using his hands on spinous processes to create levers to adjust the spine [Citation11,Citation12], AT Still developing a theory of health maintenance and healing including hands-on treatments with Osteopathy in 1874 [Citation13] or Ling and Branting integrating hands-on interventions as part of medical gymnastics in the development of the physiotherapy profession circa 1813–1865 [Citation14,Citation15]. The skills brought by these pioneers were scrutinized by Sir James Paget in 1867 and other physicians that sought to acquire the use of bonesetters’ manipulations [Citation16]. What is missing in these narratives is an inquiry into why people sought different forms of care from medicine in nineteenth century Europe and the USA. Further inquiry is needed to better understand if four different professions truly developed independently or whether societal needs and opportunity for professional development led to the growth of professions providing hands-on care that shared a genesis in a common societal desire but created different historical narratives [Citation17–Citation19].

Manipulation in Europe and the USA

To understand the complex historical narrative, a brief overview of manipulative therapy history in Europe is helpful. Both Greek and Roman medical practitioners utilized manipulation in conjunction with gymnastics based rehabilitative approach for hundreds of years starting around 500 BC [Citation2,Citation18]. When the Roman Empire fell and Europe divided into Western and Eastern realms with fracturing along religious lines, hands-on manipulative interventions continued in the Byzantine East (Persia), but were removed from the hands of the lay practitioners and medical providers in the West (France/Germany/England) by church restrictions on providing medical interventions outside of religion [Citation19–Citation21]. With the enlightenment of the seventeenth century, the downward pressures restricting the use of hands-on approaches in healing were lifted in Europe [Citation22]. Bone-setters, likely predominant in hundreds of small towns through Europe, were more active and ironically than those more exposed to the developing regulation of medical societies [Citation16,Citation22]. An interest in the management of sprains, strains and minor injuries emerged, as medical providers moved from the age of heroic medicine into a more vested interest in hands-on approaches, for a more demanding society [Citation23,Citation24]. The ‘what is good… in the practice of bonesetters’[Citation16, p. 4] started to become of interest in Northern Europe around the same time that more formalized gymnastic approaches were refined in the Scandinavian nations bringing mechanotherapy into mainland Europe [Citation25,Citation26].

In the United States, similar social influences occurred in the nineteenth century with a developing middle class seeking a higher quality of life. Alternatives to opium, cocaine, morphine and alcohol-based approaches for musculoskeletal impairments were greatly desired [Citation27]. The nineteenth century brought a tremendous population migration from Europe to the Northern American continent. This key historical event created shared needs from two population groups, separated by the Atlantic. This could be a primary reason for the genesis of different professions providing very similar services under different titles [Citation28,Citation29].

As the use of hands-on treatments by medical professionals in Europe in the nineteenth century expanded, the traditional role of bone setters declined. Early progenitors of physiotherapy (Swedish mechanotherapists) and physicians sought to integrate the use of manipulative treatments in their patient care [Citation30,Citation31]. During this time, regulatory acts such as the Medical Act of 1858 in the United Kingdom limited the ability of ‘non-qualified’ practitioners from providing treatments that they had been offering for hundreds of years [Citation32]. Protective regulatory policies were introduced in Europe and sought by new professions in the USA [Citation33]. As a response, health-care professions sought to gain regulatory protections for the ability to practice what they had either previously used under another name or what they claimed to have discovered [Citation33–Citation35].

The United States did not have the same regulatory pressures of Europe and offered a ‘green-field’ for the development of new health-care providers in the late nineteenth century. Into this professional opportunity came osteopathy and chiropractic practice [Citation36,Citation37]. This more isolated nature of the USA Midwest versus the heavily European influenced east coast saw the development of osteopathy first in Missouri and chiropractic in Iowa [Citation4].

According to historical records, Andrew Taylor Still created osteopathy in the 1870s and Daniel David Palmer founded chiropractic in the 1890s. Both were previously bone-setters and/or magnetic healers [Citation38,Citation39], and potentially shared common influences [Citation40]. Still was famously known as the ‘lightning bonesetter’ and Palmer recognized influences from mesmerism and magnetic healing [Citation41]. Each saw the need to form a new profession to provide hands-on care to increasingly demanding and readily accepting societies. For Palmer, early patients expressed recognition of similar approaches between chiropractic and the Napravit approaches of Bohemia in Europe [Citation17].

Concurrently, directors of gymnastics in Northern Europe educated visiting physicians in specific exercise and hands-on treatment approaches throughout most of the nineteenth century [Citation42,Citation43]. By the 1880s, these gymnastic directors were formally called physiotherapists [Citation43]. Physicians such as Edgar Cyriax, initially a physiotherapist [Citation6], attended the Swedish Mechanotherapy schools to learn manipulative interventions in the late 1890s, and indeed Cyriax eventually wrote his thesis on Swedish Mechanotherapy [Citation44]. His son, James, likely influenced by his father’s studies, established orthopedic medicine in the early twentieth century in the United Kingdom. Progenitor’s of physiotherapy such as Jonas Kellgren established institutions throughout Europe to provide a mechanotherapy-based approach to care with such success by the 1870s that prominent individuals from the United States brought themselves and family members to ‘Swedish institutions’ in Northern Europe to receive care [Citation43]. One such prominent individual was Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

Mark Twain suggested that the hands-on approach of the manual therapists/physiotherapists in Europe was very similar to the ‘new’ approach of the DO’s/DC’s in the USA [Citation45]. He, in fact, stated that osteopaths and Swedish mechanotherapists provided the same treatment but from different ideologies in 1900 in a letter written to support the Director of the Swedish Mechanotherapy institute for recognition at the American Osteopathy institute in Kirksville, Missouri [Citation45]. He expressed support both for the Mechanotherapists in Europe and the osteopaths in the USA and provided testimony to support osteopathic regulation and recognition in New York state in 1901 [Citation46]. Shortly after that published papers presented an argument against the potential similarities between osteopathy and manual PT [Citation47].

Manual therapy: more similarities than differences between professions

History informs us that the PT, DO, DC and MD professions borrowed heavily from traditional healers, bone-setters and a common societal need for better healthcare. This is not to deride any profession but to highlight the potential that a common genesis is shared between professions. This narrative describes the early and continuing desire of the four professions for regulatory protections, the uniqueness of ideology and the simple effects of geographic separation between the United States and Europe. These professions have a lot more in common in the provision of musculoskeletal care. Born in relative isolation, the DC and DO professions in the USA, manual medicine within MD and the PT professions in Northern Europe, have been driven into an inevitable collision as they sought to carve out the uniqueness of their respective approaches and claim a historical narrative (in part) supporting their ownership of manipulative interventions. The historical narrative brought forward by each profession is in need of a challenge. It is time for health-care professions with expertise in hands-on manipulative treatments to partner to seek advancements in healthcare to create a greater benefit to our patients and society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). Position on thrust joint manipulation provided by physical therapists. 2009 Feb [cited 2018 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/Advocacy/State/Issues/Manipulation/WhitePaperManipulation.pdf

- Meeker WC, Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):216–227.

- Beyerlein C. The history of spinal manipulation from Hippocrates to the present. Kranken Gymnastik. 2002;54(11):1780–1784.

- Bovine G, Atkinson J (1854–1904). The English Bonesetter of Park Lane: his visit to America, bonesetting techniques, and the Atkinson connection to Chiropractic. John Washington Atkinson. Chiropract Hist. 2013;33(1):52–64.

- DeVocht JW. History and overview of theories and methods of chiropractic: a counterpoint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:243–249.

- Pettman E. A history of manipulative therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(3):165–174.

- Mirtz TA, Greene L. Biomedicine throughout history and the development of science as it relates to manipulative therapeutics. Chiropract Hist. 2003;23(2):59–67.

- Marrone R. Body of knowledge: an introduction to body/mind psychology. Albany (NY):State University of New York Press; 1990.

- Graham D. Massage, manual treatment, remedial movements, history, mode of application, and effects: indications and contra -indications. Philadelphia and London: J.P. Lippincott Company; 1913.

- Richards DM. The Palmer philosophy of chiropractic - a historical perspective. Chiropr J Aust. 1991;21(2):63–67.

- Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. The Chiropractic Adjuster: a compilation of the writings of D.D. Palmer. Davenport (IA): Palmer School of Chiropractic; 1921.

- Palmer DD. The science of Chiropractic. Davenport (IA): Palmer School of Chiropractic; 1906.

- Still AT, Graves F. The philosophy and mechanical principles of Osteopathy. Kansas City (MO): Hudson-Kimberly; 1902.

- Ling PH, Cyriax RJ. Educational gymnastics. Am Phys Edu Rev. 1912;697–704.

- Cyriax EF. Concerning the early literature on long’s medical gymnastics. Janus. 1930;26:225–232.

- Paget J. Cases that bone setters cure. J Br Med Assoc. 1867 Jan;314:1–4.

- Bovine G. The Bohemian Thrust: frank Dvorsky, the Bohemian “Napravit” Bonesetter. Chiropract Hist. 2011;31(1):39–46.

- Johnson W. The anatriptic art: a history of the art termed anatripsis by Hippocrates, tripsis by Galen, friction by Celsus, manipulation by Beveridge and medical rubbing in ordinary language, from the earliest times to the present day, followed by an account of its virtues in the cure of disease and maintenance of health. London: Simpkin Marshall; 1866.

- Gaucher-Peslherbe PL. Chiropractic: early concepts in their historical setting. Lombard (IL): National College of Chiropractic; 1993.

- Gaucher-Peslherbe PL. The Doctress of Epsom has outdone a chiropractor! Eur J Chiropr. 1983;31:13–16.

- Withington ET. Medical history from the earliest times: a popular history of the healing art (classic reprint). London: FB&C Limited; 2015.

- Gaucher-Peslherbe PL, Lawrence DJ. Chiropractic: early concepts in their historical setting. Lombard (IL): National College of Chiropractic; 1993.

- O’Brien JC. Bonesetters: a history of Osteopathy in Britain. Tunbridge Wells: Kent; 2012.

- Hood WP. On bone-setting, so called, and its relation to the treatment of joints crippled by injury, rheumatism, inflammation. New York London: Macmillan; 1871.

- Cyriax EF. Henrik Kellgren and his methods of manual treatment. London: John Bale, Sons & Danielsson; 1908.

- Ehrenhoff C. Medical Gymnastica or Therapeutic Manipulation: a short treatise on this science. Edinburgh: J Masters; 1845.

- Hamonet C. Andrew Taylor Still and the birth of osteopathy (Baldwin, Kansas, USA, 1855). Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(1):80–84.

- Fassett J. Osteopathy; its theory, history and scope and its relation to other systems. J Osteopathy. 1903 May 5;146–148.

- Fuller D Osteopathy and Swedenborg: the influence of Emanuel Swedenborg on the Genesis and development of osteopathy, specifically on Andrew Taylor Still and William Garner Sutherland. PCOM Scholarly Papers. 2012.

- Roth M. Notes on the movement-cure, or, rational medical gymnastics: the diseases in which it is used, and on scientific educational gymnastics. London: Groombridge; 1860.

- Taylor CF. The movement cure; with cases. New York (NY): J. A. Gray; 1858.

- Commons GBPH of. British Medical Act. Schedule A, paragraph 11. A Bill Intituled an Act to Amend the Law Relating to the Qualification of Practitioners in Medicine and Surgery, and Otherwise to Amend the Medical Act. 1858.

- Bullard JR. The osteopathic profession. J Osteopathy. 1902 Oct 10;325–327.

- Barclay J. Good hands. In: The history of the chartered society of physiotherapy 1894–1994, 1sted. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

- Still AT. Osteopathy with the lawmakers. J Osteopathy. 1902 Feb 2;63–67.

- Harlan WL. Osteopathy, the New Science. Chicago: Donohue &. Henneberry; 1898.

- Paris SV. A history of manipulative therapy through the ages and up to the current controversy in the United States. J Man Manip Ther. 2000;8(2):66–77.

- Jackson RB. Andrew Taylor Still, M.D., D.O.: the man, the pioneer, the educator and founder of osteopathy. Chiropract Hist. 2000;20(2):15–24.

- Still AT. From a faker to a faculty: how Dr. Still, “Lightning Bonesetter” of Missouri, Founded Osteopathy School. Kirksville (MO); 1912.

- Hart JF, Did DD. Palmer visit A.T. Still in Kirksville. Chiropract Hist. 1997;17(2):49–55.

- Homola S. Chiropractic: history and overview of theories and methods. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:236–242.

- Cyriax EF, Kellgren-Cyriax A. The mechano-therapeutics of muscular torticollis. N Y Med J. 1912;95:1031–1034.

- Cyriax EF. Collected papers on mechano-therapeutics. London: John Bale, Sons & Danielsson; 1924.

- Ottosson A. The manipulated history of manipulations of spines and joints? Rethinking orthopaedic medicine through the 19th century discourse of european mechanical medicine. Med Stud. 2011;3(2):83–116.

- Twain M. Personal correspondence to American Osteopathy School from London. London: Museum of Osteopathic Medicine; 1901. 1976.01.01c.

- Poste Express Feb 28. Mark Twain speaks for the osteopaths. J Osteopathy. 1901 Feb 2;114–116.

- Woodall PH. Osteopathy (not massage nor Swedish movement). J Osteopathy. 1908;15(4):176–179.