You start a new job in a physical therapy clinic that specializes in treating patients with low back pain. You are excited. The clinicians you will work with in the clinic are board-certified specialists, fellowship trained, and are actively involved in clinical research. The clinic uses different treatment systems to classify patients and match those patients with the best treatment options. Your colleagues enthusiastically report that they are attaining excellent results, yet you notice that they do not appear to be reassessing their patient’s impairments within and between treatment sessions. You ask one of your colleagues, ‘What is the evidence supporting your treatment system that makes it better than other treatment approaches?’ The next day you receive eight references that support the use of the treatment approach and you thank your colleague for their assistance.

As a busy clinician, you use the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) website [Citation1] to identify the quality of the studies. You know that the PEDro scale has 11 criteria. The first criterion determines the external validity of the study and the other 10 help determine the internal validity of the study. You know that in general, you are interested in studies that score 6 or better on the scale according to the website [Citation1]. When you look up the studies on the PEDro website, you discover that for half of the studies the degree of external validity could not be determined. The other half has a PEDro score below 6 indicating low-quality studies with questionable internal validity. While on the PEDro website, you discover four different studies that satisfy the external validity criterion on the PEDro score and have PEDro scores of 6 or higher. These studies, with a respectable degree of external and internal validity, provide moderate to high-level evidence that the current system is no better than guideline-based care or advice to stay active [Citation2].

The next day, you bring in the evidence to have a conversation with your colleague. You report on what you found, and your colleague responds with, ‘you didn’t find any evidence that this assessment and treatment approach doesn’t work (Argument from ignorance-Logical fallacy)’. He goes on to say that ‘you are overly biasing the use of evidence in evidence-based practice (EBP) (Ad hominem-Logical fallacy)’ and that ‘EBP is the blend of the evidence, clinical experience, and patient values’. He elaborates on his recognition as a clinical expert and that the best clinics in the country are using this system (Appeal to authority-Logical fallacy). He states he has seen the efficacy of this treatment system with his own eyes and that clinical experience provides the best evidence (Cum hoc ergo propter hoc and/or post hoc ergo propter hoc-Logical fallacy). The conversation ends.

This vignette illustrates and highlights the predictably irrational [Citation3] conversations that are going on all over the country that may stifle the progress of our profession. Any classification system that is used to treat patients: 1) Must be able to discriminate between groups of patients; 2) Needs to be comprehensive in its ability to classify all patients and create mutually exclusive groups; 3) and should not have subgroups that patients never or rarely fit into [Citation4]. Any system that does not meet these criteria has significantly limited clinical utility [Citation4]. To date, there are no known classification systems that satisfy these criteria [Citation2,Citation5–7].

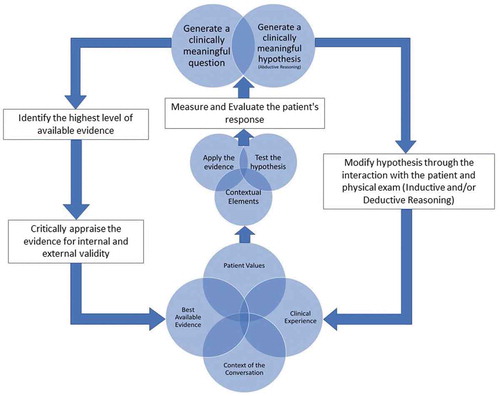

The process of EBP starts by asking a clinically meaningful question, seeks to find the best available evidence that can be used to answer the question, combines the best available evidence in the context of the clinicians' clinical experience, and the values of the patient, and evaluates the efficacy of the process based on the patients' response [Citation8]. EBP does not start with the answer to a clinical question then only seeks evidence that supports that answer (Confirmation bias-Cognitive bias). Attempting to answer a clinical question using a treatment system creates the assumption that you have the only, right, or best answer to the clinical question before developing a question. This thought process creates a high risk of confirmation bias. We all tend to remember our outstanding results and tend to forget average or less than spectacular results (Recall bias-Cognitive bias). If the facts conferred from the best available evidence do not support your opinion you cannot extract the evidence from EBP to support an opinion (Fallacy of incomplete evidence-Logical fallacy).

In 1999, DiFabio wrote a piece on the ‘Myth of evidence-based practice’. He stated, ‘I think that we need to abandon the quest for absolute truth and look, instead, at clinical research as a way to develop a reasoned philosophy about patient care.’ [Citation9]

‘Clinical reasoning is a reflective process of inquiry and analysis carried out by a health professional in collaboration with the patient with the aim of understanding the patient, their context, and their clinical problem(s) in order to guide evidence-based practice. [Citation10]

Reasoning involves the use of abductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, and deductive reasoning. Abductive reasoning is the reasoning used to generate hypotheses. Inductive reasoning collects disconnected pieces of evidence that increase the probability of something being true. Deductive reasoning creates a linear evidentiary framework to prove that something is true.

We use abductive reasoning to generate hypotheses during our early interactions with the patient. We then use inductive and/or deductive reasoning to modify and refine hypotheses as we progressively gather data through the examination process. We go onto test the hypothesis that is most likely true by providing the patient with an intervention most likely to improve their primary complaint if the hypothesis is correct. If the patient improves, the hypothesis is probabilistically accurate. This iterative process occurs frequently and evolves based on the response of the patient within and between treatment sessions. Clinical practice involves manipulating the probability of something being true based on a reasoned philosophy that is dynamic. It may be time to abandon the dream of a linear framework of being able to identify the only, right or best answer for the patient sitting in front of us. Using the premises of different classification systems and using an evidence informed reasoned probabilistic approach may create a link between hypothesis generation, hypothesis modification, hypothesis testing, and the patient’s outcome that when repeated increases the probability of success.

‘If it does not fit, it is the theoretical statement that must be wrong because the clinical presentation cannot be wrong.’ -Geoff Maitland

If we plan on using clinical reasoning to work through the evidence informed clinical process (), we should cognitively understand what reasoning is and is not, as well as being consciously aware of our own biases while conversing with our colleagues. A reasoned approach espoused in conversation must consider logically fallacious thinking or cognitive biases as illustrated above. Reasoned conversations should not be used to ‘win’ or end a conversation, either intentionally or unintentionally, but rather to insight further ‘truths’ and inform decision making. People are entitled to their own opinions, yet the best available evidence using a reasoned approach that recognizes and seeks to eliminate logically fallacious thinking and cognitive biases should inform ‘professional opinions’. If we eliminate the irrational and use a reasoned approach, the assimilation of that evidence into clinical practice may be expedited. Being mindfully reflective of a reasoned approach in and on our conversations may prove more productive in moving our profession forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro): centre for evidence-based physiotherapy, school of physiotherapy, The University of Sydney; 2019 [cited 2019]. Available from: https://www.pedro.org.au/english/pedro-publications/

- Riley SP, Swanson BT, Dyer E. Are movement-based classification systems more effective than therapeutic exercise or guideline based care in improving outcomes for patients with chronic low back pain? A systematic review. J Man Manip Ther. 2019 Feb;27(1):5–14. PubMed PMID: 30692838; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6338264

- Ariely D. Predictably irrational: the hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2009.

- Fritz J. Disentangling classification systems from their individual categories and the category-specific criteria: an essential consideration to evaluate clinical utility. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 Dec;18(4):205–208. PubMed PMID: 22131794; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3113265

- Kent P, Keating J. Do primary-care clinicians think that nonspecific low back pain is one condition? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 May 1;29(9):1022–1031. PubMed PMID: 15105677.

- Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. Treatment-based subgroups of low back pain: a guide to appraisal of research studies and a summary of current evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Apr;24(2):181–191. PubMed PMID: 20227640.

- Abenhaim L, Rossignol M, Gobeille D, et al. The prognostic consequences in the making of the initial medical diagnosis of work-related back injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Apr 1;20(7):791–795. PubMed PMID: 7701392.

- Manske RC, Lehecka BJ. Evidence-based medicine/practice in sports physical therapy. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Oct;7(5):461–473. PubMed PMID: 23091778; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3474298.

- Di Fabio RP. Myth of evidence-based practice. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999 Nov;29(11):632–633. PubMed PMID: 10610175

- Mosby’s BC. Dictionary of medicine, nursing and health professions. Vol. 2013. 9th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2013.