ABSTRACT

The current study had three aims: (1) to explore whether there is over-time change in adolescent delinquency and negativity in the parent–adolescent, sibling and marital relationships during adolescence; (2) to examine the interactions of negativity across subsystems; and (3) to examine whether levels and changes in adolescent delinquency are predicted by levels and changes in negativity in all family subsystems. Data of 497 families participating in the RADAR-young study were used. Ratings of all family members were used to measure negativity in family relationships, and adolescent self-report was used for delinquency. Multivariate latent growth curve models showed over-time increases in mother-adolescent negativity and over-time decreases in sibling negativity, as well as significant individual differences in these changes. Second, evidence for both social contagion and compensatory processes in family negativity was found. Third, initial levels of parent–adolescent negativity were related to initial levels but not over-time changes of adolescent delinquency, whereas initial levels of sibling negativity were related to over-time changes but not initial levels of adolescent delinquency. Finally, increases in parent–adolescent negativity were related to faster increases in adolescent delinquency, and decreases in sibling negativity were related to slower increases in adolescent delinquency. Implications of these results are discussed.

Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period during which delinquency has been shown to increase. Many studies have shown that age is related to offending or engagement in delinquent activities (Farrington, Citation1986; Loeber & Farrington, Citation2014; Tremblay & Nagin, Citation2005). In general, we know that the prevalence of delinquent behavior gradually increases from childhood towards adolescence, with a distinguished peak of delinquency engagement around age 15–19 (Loeber & Farrington, Citation2014). Similar patterns were shown in the study of Stanger et al. (Citation1997) in which trajectories of delinquent behavior in childhood, adolescence and the beginning of adulthood were analyzed. Their results indicate that from the age of 10 years delinquent behavior increases until the adolescents reached the age of 17. Additionally, in a study on the normative adolescent development of problem behavior, Bongers et al. (Citation2003) found that delinquent behavior showed an increase during the period of adolescence.

Family relationship quality has often been successfully used to explain individual differences in the development of delinquency involvement during adolescence (Pardini et al., Citation2015). According to interactional theory (Thornberry, Citation2014) and social control theory (Hirschi, Citation1969), weak social bonds with other family members make it more likely for adolescents to engage in delinquent activities. This would mean that lower levels of family relationship quality, reflected by low levels of support and high levels of negativity, would be related to increased delinquency involvement. Intervention studies have also shown that family-based treatments are promising in reducing delinquency in adolescence through increasing daily family contact and improving or restoring family relationships. For example, Multisystemic Therapy and Functional Family Therapy are shown to be effective in decreasing adolescent antisocial and delinquent behavior (Henggeler, Citation2015). Additionally, Windle (Citation2000) for example, examined latent growth models of delinquency among adolescent boys and girls, using family support as a predictor of change in adolescent delinquent behavior. Despite the fact that lower levels of family support were related to higher initial levels of delinquency, family support was not a significant predictor of change of delinquency over time. Similar results were found in the study of Deković et al. (Citation2004). Keijsers et al. (Citation2012), taking a somewhat different approach, found that over-time changes in parent–child relationship quality were linked to over-time patterns in adolescent delinquency. However, their sample consisted of only boys.

So, different aspects of family relationship quality have been linked to initial levels and over-time changes in adolescent delinquent behavior. Because empirical evidence has shown that negative aspects of family relationships – as compared to positive aspects – may be stronger predictors of adolescent problem behavior (e.g. Buysse, Citation1997; Muris et al., Citation2003), in the current study we will focus on negativity in family relationships only. Negativity in the family context can be defined as the perceived amount of annoyance, hostility, disagreements, and conflicts between family members (Furman & Buhrmester, Citation1992).

Although most previous studies either focus on the family as a whole or on the specific relationship between a parent and an adolescent child, there are indications that the quality of relationships between specific family members may affect adolescent delinquent development in different ways. For example, Buist et al. (Citation2015) found that higher levels of sibling conflict were significantly related to higher initial levels of as well as faster decreases in adolescent delinquency. Another point of concern is that in many of the above-mentioned studies the quality of family relationships is used as a static concept. That is, changes in delinquency are linked to a cross-sectional measure of family functioning or family status variables, while it is well-known that family functioning undergoes huge changes during the adolescent period (Li et al., Citation2018). In the current study we therefore aim to examine how over-time development of adolescent delinquency is related to over-time development of perceived negativity in the parent–adolescent, sibling and marital relationship.

Family relationships: interacting subsystems

According to a family systems theory perspective, the family is a dynamic and interactive system that consists of several interacting subsystems: the marital, sibling, and parent–child subsystem (Cox & Paley, Citation1997, Citation2003). We know that the quality of relationships between family subsystems is interrelated, which means that these subsystems are also likely to influence each other. Some researchers suggest that if a certain family relationship is characterized by increasing negativity, other family members might turn to each other for support which leads to decreasing negativity in other family subsystems (Whiteman et al., Citation2007). This phenomenon is known as the relationship compensation hypothesis. Another viewpoint is that one very negative relationship leads to increases in negativity in the other family relationships, which is known as the social contagion hypothesis (Whiteman et al., Citation2007). Empirical support has been found for both these theories (Buist et al., Citation2011; Dunn et al., Citation1999; Feinberg et al., Citation2005).

Empirical studies showed more compensational patterns of negativity between the sibling subsystem and parent–adolescent relationship, and spillover effects (social contagion) between marital and parent–adolescent subsystems (see for example: Dunn et al., Citation1999; Margolin et al., Citation2004). Results concerning the link between the marital and the sibling subsystem are contradicting, precluding firm conclusions (Dunn et al., Citation1999; Feinberg et al., Citation2005).

Family relationships during adolescence

The quality of the parent–adolescent relationship changes substantially during the period of adolescence. Whereas some studies report increasing levels of conflict between parents and adolescents (e.g. Steinberg, Citation2001), there are also studies that report a decline in the frequency of conflict between parents and their children. However, there are also indications that it is mostly the affective intensity of these conflicts that increases over time.

With regard to sibling relationships it has been found that older adolescents experience less conflict and rivalry and more warmth and positivity in their relationships with siblings than younger adolescents (Buist et al., Citation2002; Scharf et al., Citation2005).

Regarding the marital relationship, the findings seem to be less conclusive: Whiteman et al. (Citation2007) found that marital conflict remained stable during their offspring’s puberty. However, there are also indications that the normative development of marital relationship quality is characterized by an increase of marital partners’ experienced levels of conflict and negativity over time (Kurdek, Citation1999), independent of the age of their offspring.

In sum, there is reason to believe that negativity in family relationships seems to fluctuate during adolescence and early-adulthood. Therefore, it seems of great importance to consider the changing nature of family relationship quality when studying the associations with adolescent delinquency. By considering family relationship quality in a developmental perspective, contributions can be made to a better understanding of associated developmental processes (Hollenstein et al., Citation2004; Van Geert & Steenbeek, Citation2005).

Family relationships and adolescent delinquency

From the previous overview one can conclude that on the one hand there is a body of literature suggesting patterns of over-time change in adolescent delinquency, while on the other hand there are several studies that underline the importance of considering over-time change in family negativity. Theoretical perspectives such as the interactional theory of delinquency development (Thornberry, Citation2014) underscore the importance of (changes in) family relationship quality in explaining (changes in) adolescent delinquent engagement. These processes are also evident in family-based interventions, which show that improving family relationship quality results in decreased adolescent delinquency (Henggeler, Citation2015). However, studies that examine patterns of related change between family relationship quality and adolescent delinquent behavior are – until now – limited to studies that consider one single family subsystem. For example, decreases in parental knowledge about their child’s activities and personal life (i.e. an indicator of parent–child relationship quality) over time have been shown to be related to increases in self-reported delinquent behavior (Reitz et al., Citation2007). Concerning sibling relationships, Buist (Citation2010) found some evidence that faster increases in quality of sibling relationships were related to slower increases in adolescent delinquent behavior. With regard to changes in marital relationship quality, Cui et al. (Citation2005) found that over-time change in marital conflict was significantly related to change in adolescent delinquency: increases in marital conflict seemed to be related to increases in adolescent delinquency. Because we know that family negativity among several family subsystems interact with and influence each other, it is essential to consider patterns of related change between negativity in all these family relationships and adolescent delinquent behavior.

Present study

There were three aims to the present study. The first was to explore whether there is over-time change in adolescent delinquency and whether there is over-time change in negativity in the parent–adolescent, sibling and marital relationships in the period of adolescence. We expected delinquent behavior to show an increase over time during adolescence (Bongers et al., Citation2003; Farrington, Citation1986; Loeber & Farrington, Citation2014; Stanger et al., Citation1997; Tremblay & Nagin, Citation2005). We also expected parent–adolescent negativity to increase (Steinberg, Citation2001), sibling negativity to decrease (Scharf et al., Citation2005), and marital negativity to remain stable over time (Whiteman et al., Citation2007) during the period of adolescence.

The second aim was to examine the correlations of negativity across subsystems. Based on empirical evidence (Dunn et al., Citation1999; Margolin et al., Citation2004), we expected negative correlations between the sibling and parent–child relationship (reflecting patterns of compensation) and positive correlations between the marital and parent–child relationship (reflecting patterns of social contagion). Due to the contradicting findings (Dunn et al., Citation1999; Feinberg et al., Citation2005), we had no clear expectations concerning the correlations between the marital and sibling relationship.

The third aim was to examine whether levels and changes in adolescent delinquency are predicted by levels and correlated to change in family negativity in all family subsystems. Based on earlier studies that have examined family subsystems in isolation (Buist, Citation2010; Cui et al., Citation2005; Reitz et al., Citation2007), we expected to find that higher initial levels of parent–adolescent, sibling, and marital negativity would predict higher initial levels of as well as increases in delinquent behavior. Additionally, we expected to find that over-time increases in parent–adolescent, sibling, and marital negativity would be related to over-time increases in delinquent behavior.

Method

Participants and procedure

A sample of 497 participating target adolescents and their families from the ‘Research on Adolescents Development and Relationships’(RADAR-young) project were included in the current study. The participants in this study were selected by a two-step inclusion phase (for additional details, see Maciejewski et al., Citation2015). In the first phase, 230 primary schools in the Western and central parts of the Netherlands were approached. To oversample adolescents at risk for externalizing behavior, teachers rated the adolescents’ externalizing behavior using the externalizing scale of the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, Citation1991; Verhulst et al., Citation1997). A total of 3237 adolescents were selected based on these teacher’s ratings and the criterium Dutch origin (because good command of the Dutch language was essential for successful participation). In the second phase of the study, the families of these adolescents were contacted. Families in which both parents were available, and that included a sibling of at least 10 years old were eligible to participate in the study. Of the 1544 families of the adolescents who were randomly selected from the larger sample, 497 families met these criteria and agreed to participate in the study after providing written consent.

Adolescents were screened and recruited during primary school (230 different schools throughout a relatively large region). Data collection started when adolescents were in their first year of secondary school. Because adolescents were in a large number of different schools and also in different schools during screening and measurement, nesting effects of students in schools are unlikely. Data collection consisted of adolescents and their family members (i.e. parents and one sibling) filling out questionnaires during annual home visits. Trained research assistants provided verbal assistance in addition to written instructions that accompanied the battery of questionnaires. Families received about 100 euros for their participation annually.

All families included in the current study were of Dutch origin and predominantly from middle class families. Mean age of the target adolescent was 13.03 years at Time 1 (SD = 0.46), mean age of mothers was 44.41 years (SD = 4.45), of fathers 46.74 years (SD = 5.10) and of siblings 14.74 years (SD = 3.11). It should be noted that parents could ask any sibling to participate in the study, therefore siblings were not necessarily closest in age to the target adolescent. Of the target adolescents, 57% were boys. There was an equal distribution of same sex (51%) and mixed sex (49%) sibling pairs. In the majority of included families, the target adolescent was the younger sibling (74%).

We used the first six annual measurements waves of the RADAR-young study covering the whole period of adolescence of the target individual (ages 13–18 years). Inherent to the full family design in the current study, an analysis of the missing data patterns showed that there were some families with missing data. The number of families that could be included in the present study dropped from 497 at wave 1 to 410 at wave 6. The patterns of missing data could be mainly subscribed to absence of certain family members along the waves. Little’s Missing Completely At Random test (MCAR; Little, Citation1988) revealed a normed χ2 (χ2/ df) value of 1.17 (3.420/2.919), indicating a good fit between the sample scores with and without imputation of missings (Bollen, Citation1989; Ullman, Citation2001). In order to prevent a loss of information caused by the exclusion of families with missing data, the MLR approach was used in Mplus thereby including participants with partially missing data (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017; Widaman, Citation2006).

Measures

Delinquent behavior

In all six measurement waves, adolescents completed the Delinquent Behavior subscale of the Youth Self Report (YSR: Achenbach, Citation1991). This subscale consists of 11 items (for example: ‘I steal from my home’, ‘I lie or cheat’ and ‘I use alcohol or drugs’), to be answered on a 3-point answering scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true and 2 = very true or often true). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .70 to .77 across measurement waves.

Negativity in family relationships

Negativity in all family subsystems was assessed by using the subscale negative interaction of the Network of Relationship Inventory (NRI: Furman & Buhrmester, Citation1985, Citation1992). The scale consists of 6 items that reflect the degree of annoyance, hostility, disagreements, and conflicts (for example: ‘How often do you and your mother/father/sibling quarrel and fight?’). The questionnaire was filled out by every single family member about their relationship with every other participating family member. It was to be answered on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = hardly at all to 5 = extremely much. The reliability of this scale was satisfactory: Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .89 to .96 across family members and measurement waves.

Due to the complexity of the analytic models, ratings of negativity of two family members judging their relationship with each other were averaged to form a dyadic score of negativity. For example, the NRI negativity score of father about target adolescent and of target adolescent about father were averaged to reflect dyadic negativity in the father-target adolescent relationship. Mean overall correlation between scores of two dyad members across measurement waves was .51 (with a minimum of .39 and a maximum of .62). Although this method sacrifices information on family members’ unique perceptions, averaging relationship scores compared to the use of a single informant has also been shown to improve its reliability (Mathijssen et al., Citation1998).

Analytic strategy

In the present study, multivariate Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) was used to examine changes in family relationships in several family subsystems and changes in adolescent delinquency by using Mplus (version 8.1; Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017). All models were tested with the MLR estimation method (Maximum Likelihood estimation with robust standard errors). The first step was to model each construct in a univariate factor growth model separately in order to assess patterns of change in every construct. Covariates gender and sibling birth order and a covariate reflecting same – or different gendered sibling pairs were added to these univariate LGM’s in order to assess their association with the intercept and slope of the specific construct. For each construct, a linear model was tested first, followed by a model including a quadratic growth curve. After the univariate models were successfully tested, they were modeled simultaneously (Duncan et al., Citation2006). In all models, the intercept was estimated at wave 1 and represents the initial level of the measure.

Therefore, the next step in the analyses was to link the separate LGM’s of family negativity to each other and to the LGM of delinquency. This model represents a predictive multivariate LGM, in which intercept, linear slope and quadratic slope of adolescent delinquency were predicted by family negativity intercepts. Additionally, the intercept, linear slope and quadratic slope of adolescent delinquency were correlated with linear and quadratic slopes of family negativity. The assumed pattern of directionality is informed by the potentiality of the current paper to contribute to family interventions. Family relationship quality is considered to be a dynamic risk factor for the onset and over-time development of adolescent (and later adult) delinquency. With the directionality in our current models, we are able to show rather specifically how negativity in a specific family subsystem/ dyad (for example by addressing this in a family therapeutic intervention), may be related to delinquency development of the adolescent child.

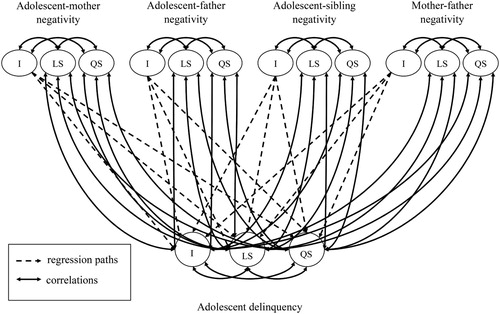

In only latent factors of levels and linear and quadratic slopes are shown, as are the regressions and correlations between these intercepts and slopes. Observed scores of negativity in each subsystem or adolescent delinquency, covariates, and the correlations of negativity intercepts, linear and quadratic slopes between different family subsystems are not shown in the model for the sake of clarity.Footnote1 Intercept-slope correlations between family subsystem negativity and adolescent delinquency were specified and also shown in .

Figure 1. Multivariate latent growth model used in the current study (simplified). Note: I = Intercept, LS = Linear slope, QS = Quadratic slope; Not shown for clarity reasons: observed scores of negativity in each subsystem or adolescent delinquency, covariates and the correlations of negativity intercepts, linear and quadratic slopes between different family subsystems.

The covariates that were significant in the univariate models were also added to the overall model to control for their assumed association with the intercept and slope of the specific construct by regressing the relevant growth factors on these covariates. The goodness of fit of both univariate and multivariate models is tested by examining several goodness-of-fit indices: χ² value, corresponding p value, the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Recommendation guidelines for each model fit index were used. That is, a non-significant χ²-value, CFI -values greater than .95, and RMSEA-values below .05 represent a good fit (Kline, Citation2005). Model comparison was done using Santorra-Bentler scaled χ², which is appropriate when using MLR estimation in Mplus.

Results

Patterns of change in adolescent delinquency and family negativity

The first step in the analyses was to test univariate linear LGMs for adolescent delinquency as well as of negativity in the father-adolescent, mother-adolescent, sibling and marital subsystem. For each of the constructs, adding a quadratic growth curve provided a significantly better fit (delinquency Δχ2(6) = 62.73, p < .001; negativity father-adolescent Δχ2(6) = 77.87, p < .001; negativity mother-adolescent Δχ2(6) = 41.90, p < .001; negativity sibling-adolescent Δχ2(6) = 65.54, p < .001; negativity father-mother; Δχ2(6) = 13.50, p < .05). Parameter estimates as well as model fit of the final univariate three-factor LGMs are presented in . All univariate LGM’s showed acceptable fit to the data.

Table 1. Parameter estimates for univariate LGMs of negativity and delinquency.

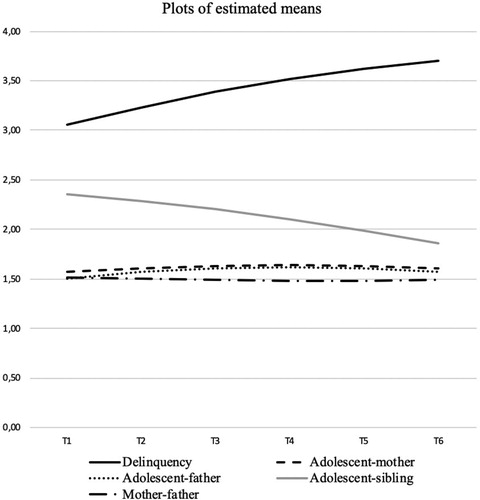

The intercept means all significantly differed from zero. The intercept variances of the assessed univariate models show that there was significant variability in the initial levels of delinquency as well as in negativity in all three subsystems (i.e. father/mother-adolescent, marital, and sibling). Parameter estimates of slope means show that negativity in the mother-adolescent relationship significantly increased over time, whereas negativity in the sibling relationship significantly decreased over time. No significant over-time change was found for delinquency, negativity in the marital relationship, nor in the father-adolescent relationship. Estimates of slope variances indicate that significant variability was found in the over-time change in adolescent delinquency as well as in negativity in all family subsystems. Only the quadratic slope mean for adolescent-mother negativity was significant, whereas the variances for the quadric slopes were significant across all variables.

After successfully fitting the univariate growth curve models separately, we combined the univariate growth curve models into a multivariate growth curve model, including significant gender and birth order covariates. Based on modification indices, four indicators of family negativity within the same wave were allowed to covary. This multivariate model showed an adequate fit to the data (χ2(381) = 564.82, p < .001; CFI = .97, TFI = .96, RMSEA = .03). The multivariate model provides information on how levels and change of family negativity are related among subsystems (see ), as well as information on how levels and change of family negativity are related to levels and change of adolescent delinquency (see ). shows the estimated means of adolescent delinquency and family negativity across the six waves, based on the final multivariate model.

Figure 2. Plots of estimated means of adolescent delinquency and family negativity across the six waves, based on the final multivariate model.

Table 2. Intercept-slope interrelations between family negativity variables.

Table 3. Regression coefficients and correlations of delinquency intercepts and linear and quadratic slopes by family negativity intercepts.

Gender and birth order were included as covariates in this multivariate model. Results showed that adolescent gender was significantly related to the intercept of delinquency (r = –.17, p < .001) and of mother-adolescent negativity (r = .12, p < .01) indicating that girls have lower initial levels of delinquency and higher levels of negativity in the mother-adolescent relationship as compared to boys. Moreover, sibling birth order was significantly associated with the intercept of sibling negativity (r = .28, p < .001), indicating that if the target adolescent is older than the sibling the initial levels of negativity in their relationship is higher. Sibling birth order was also significantly related to the intercept of adolescent-father negativity (r = .23, p < .001) and adolescent-mother negativity (r = .17, p < .01) indicating that there is more perceived negativity in the relationship of adolescents with both their parents when the target adolescent is older than the sibling.

The multivariate model showed a significant association between level and growth within the marital relationship (see ). Within the marital relationship, higher initial levels of negativity are associated with a less rapid over-time linear change in negativity in this relationship (r = –.40, p < .01). Additionally, we found that a higher initial level of delinquency is correlated with a significantly slower linear change in delinquency over time (r = –.27, p < .05). Finally, for delinquency as well as all family negativity variables, we found significant negative associations between the linear and quadratic change parameters within the same construct.

Associations between family subsystems’ negativity

Results concerning the second research question, focusing on the inter-relatedness of negativity across subsystems, can also be found in , which provides information on the interrelatedness of intercepts and slopes of negativity across the different family subsystems. The results show that initial levels of negativity are significantly positively associated across almost all family subsystems, indicating that higher starting levels of negativity in one subsystem are related to higher starting levels of negativity in other subsystems.

There are also relationships between intercepts and linear slopes that are worth mentioning here. For example, higher initial levels of mother-adolescent (r = –.17, p < .05) as well as mother-father negativity (r = –.14, p < .05) are significantly related to a less rapid linear change in adolescent-sibling negativity.

Patterns of associated linear change were also observed: faster linear changes in mother-adolescent negativity were significantly related to faster linear changes in father-adolescent (r = .62, p < .001) and adolescent-sibling (r = .36, p < .01) negativity. Similarly, faster linear changes in father-adolescent negativity were significantly related to faster linear changes in adolescent-sibling (r = .27, p < .01) and marital (r = .24, p < .05) negativity.

Links between family subsystems’ negativity and adolescent delinquency

shows patterns of associations and prediction between family negativity and adolescent delinquency. In our multivariate model, initial levels of family negativity were assumed to predict initial level of adolescent delinquency as well as linear and quadratic changes in adolescent delinquency. Additionally, linear and quadratic changes in family negativity were assumed to correlate with initial level of adolescent delinquency as well as linear and quadratic changes in adolescent delinquency.

The results indicate that higher initial levels of mother-adolescent (β = .41, p < .001) and father-adolescent negativity (β = .19, p < .05) significantly predicted higher initial levels of adolescent delinquency. Additionally, higher initial levels of adolescent-sibling negativity predicted slower linear changes in adolescent delinquency (β = –.23, p < .05). We also found patterns of associated linear change between family negativity and adolescent delinquency: linear changes in mother-adolescent (r = .48, p < .001), father-adolescent (r = .49, p < .001) as well as sibling-adolescent (r = .26, p < .01) negativity were related to similarly-paced linear changes in adolescent delinquency.

Discussion

The present study addressed the question whether over-time development of adolescent delinquency was related to development of perceived negativity in the father-adolescent, mother-adolescent, sibling and marital relationship. First, we examined whether there was significant over-time change in the assessed variables. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find an over-time increase (linear nor quadratic) in adolescent delinquent behavior, which is not in line with the literature concerning the age-crime curve. The significant variance in starting levels as well as linear and non-linear change over time suggests that there are large differences between adolescents in our sample regarding these over-time patterns. We found that boys generally reported higher levels of delinquency at age 13 as compared to girls, although they did not differ in their over-time change patterns. This pattern is consistent with earlier studies with similar samples (see for example: Miller et al., Citation2010).

With regard to the over-time development of family negativity, our hypothesis concerning the relationships between parents and their children was partially confirmed. Father-adolescent negativity was found to be relatively stable throughout adolescence, but negativity in the mother-adolescent relationship significantly increased over time. In general, the latter finding is in line with most studies on the changes in the parent–child relationship during adolescence (e.g. Steinberg, Citation2001; Steinberg & Sheffield Morris, Citation2001). Negativity in the mother-adolescent relationship was reported to be higher by girls as compared to boys. This finding is consistent with earlier work concerning mother-daughter relationships in adolescence (Branje, Citation2008)

In line with our expectations, we found a significant decrease in sibling negativity. Sibling birth order was shown to be related to levels of sibling negativity: When target adolescents were the older sibling, more negativity was reported in the sibling relationship than when they were the younger sibling. Similar results have been found in earlier work (e.g. Stewart et al., Citation1998).

Although it has been suggested that the marital relationship endures a lot of strain during the period of adolescence (Cui et al., Citation2005; Cui & Donnellan, Citation2009), we found that marital negativity overall seemed to remain rather stable over time. These findings are consistent with results of Whiteman et al. (Citation2007) who specifically examined how marital conflict as experienced by both husbands and wives changed during puberty of their offspring and found that marital conflict remained stable over time.

Social contagion or compensation in family negativity

Family systems theory suggests that family dyads do not exist in isolation, and this interdependency among family relationships needs to be considered. According to Whiteman et al. (Citation2007) there are two possibilities: patterns of social contagion can be found, but on the other hand also compensation effects might exist. Our second study aim was to examine these potential familial patterns. Our results showed support for both patterns. As expected, higher initial levels of parent–adolescent negativity were related to higher initial levels of marital as well as sibling negativity. Furthermore, higher levels of mother-adolescent and marital negativity were shown to be related to slower decreases in sibling negativity. Additionally, over-time changes in adolescent-mother and adolescent-father negativity were positively associated, as were over-time changes in adolescent-sibling negativity with over-time changes in adolescent-mother, adolescent-father and marital negativity. These results seem to suggest that these changes may occur at a similar pace throughout adolescence, which provides support for the social contagion hypothesis and suggests that there might be an underlying family effect (see for example: Rasbash et al., Citation2011). On the other hand, the finding that increases in mother-adolescent negativity were related to faster decreases in sibling negativity provide support for the existence of compensatory processes in family systems (Whiteman et al., Citation2007). From a family systems point of view (Cox & Paley, Citation1997, Citation2003), this indicates that when mother-adolescent relationships are characterized by increasing levels of negativity, siblings might seek support and help from each other, and consequently sibling negativity decreases (Dunn et al., Citation1999; Feinberg et al., Citation2003).

Family negativity is related to adolescent delinquency

Among other criminological theories, interactional theory (Thornberry, Citation2014) underlines the importance of studying (bidirectional) associations between family functioning and adolescent delinquency. Although there has been a growing interest in studying family relationships in a dynamic rather than a static way, current focus of criminological studies was often on a single family dyad, most often specifically the parent–child relationships. The current study has clearly shown that the development in family relationship quality across different family subsystems is interrelated. However, in line with interactional theory (Thornberry, Citation2014), we were specifically interested in exploring how development of family negativity in all subsystems would be related to over-time development in adolescent delinquency, which was the third aim of the current study.

The results of our study clearly show that higher levels of negativity in the parent–adolescent subsystem predicted higher initial levels of adolescent delinquent behavior, but not change in adolescent delinquency. This is in line with previous research suggesting that parent–adolescent negativity and delinquency co-occur. Additionally, initial levels of sibling negativity predicted over-time changes in adolescent delinquency.

One of the specific advantages of the current study was that we were able to examine patterns of related change between negativity in family relationships and adolescent delinquency. Patterns of related change may be specifically insightful in co-occurring development and may therefore be of help in guiding family-focused interventions. The results of the present study show that increases in not only mother-adolescent, but also father-adolescent negativity were related to faster increases in adolescent delinquency. Additionally, faster decreases in sibling negativity were associated with slower increases in adolescent delinquency. This result might indicate that adolescents whose sibling relationships show a more pronounced improvement during adolescence are less likely to become more delinquent.

Our results are in line with findings of earlier work demonstrating the protective effect of paternal (Yoder et al., Citation2016) as well as maternal support on adolescent delinquency (Hoeve et al., Citation2009). Combined with our findings concerning the sibling relationship, these findings suggest that investing specifically in relationships of adolescents with their mothers, fathers as well as siblings may have a mitigating effect on adolescent delinquency development.

Limitations and strengths

As any study, the present study has some limitations that should be mentioned here. First, only adolescent self-reports of delinquent behavior were used in the present study. Self-reports of delinquency have been found reliable in past studies (see for example: Glasgow et al., Citation1997). It would, however, also be valuable to check whether the same patterns of related change would be found when parent reports or even official record data would be used. Similarly, whereas it was beyond the focus of the current study, some of our results could also be related to sibling similarity in delinquency (see for example: Defoe et al., Citation2013; Whiteman et al., Citation2014). Given the scope of the current study, and the complexity of the model used, this is something that could be further examined in future studies.

Second, the included families were relatively well functioning intact families. It would be important to examine whether the associations we found would be stronger in families with higher levels of negativity or delinquent behavior.

Furthermore, the present study focuses on the family as a system. From previous research it is known that the relationship with peers also contributes to the development of delinquent behavior in the period of early adolescence (e.g. Fosco et al., Citation2012).

Another limitation is that, whereas the longitudinal design and analytical approach of the current study allowed us to examine associated development of family negativity and adolescent delinquency, causal inferences cannot be made based on these analyses. It would be worth exploring how specifically negative interactions between fathers and adolescents are related to delinquency engagement.

A final limitation is that due to the complexity of the combined multivariate growth model, we had to combine mutual relationship scores of negativity. Although we are aware of the disadvantages of this method (it sacrifices information on family members’ unique perceptions), it has also been shown that averaging relationship scores compared to the use of a single informant, improves its reliability (Mathijssen et al., Citation1998).

Despite these limitations, however, there are several strengths of the present study that are worth mentioning. First, examining patterns of related change in family relationships across different family subsystems has rarely been done before. Whereas in criminological research, family relationship quality has successfully been used to explain between-individual differences in delinquency (e.g. Thornberry, Citation2014), there are few criminological studies in which the family is regarded as a dynamic system of interacting subsystems. By using this approach, we were able to provide valuable information on how different subsystems interact over time. Using ratings of multiple family members to measure family negativity in the parent–adolescent, sibling, and marital subsystem also increased the validity of our study.

Additionally, rather than treating negativity in family relationships as a static concept, the present study modeled change in negativity in three different family subsystems over time. Therefore, we were able to account for the changing nature of family relationship quality during adolescence and the over-time change in delinquency during adolescence.

Finally, we focused on both mother-adolescent and father-adolescent relationship. Historically, the almost sole focus on the mother–child relationship or on the combined relationship between parents and an adolescent child has to a great extent narrowed our ideas of family relationship quality and family functioning. Our results concerning the impact of father-adolescent negativity shows that it is essential to include fathers in studies of adolescent development.

Conclusion and implications

Our study has some tentative implications for behavioral interventions aimed at decreasing adolescent delinquency. Our results indicate that negativity shows spill-over effects across all dyadic subsystems in the family system and is related to adolescent delinquency. Additionally, our results showed that over-time changes in the father-adolescent, mother-adolescent and sibling relationship are specifically related to over-time changes in adolescent delinquency. These results are consistent with existing effective interventions that aim to ameliorate adolescent problem behavior by addressing family relationships and parenting, e.g. Multisystemic Therapy, Functional Family Therapy (for an overview see Henggeler, Citation2015) and the Strengthening Families Program (Kumpfer et al., Citation2010). Oftentimes, the relationship between mothers and adolescents is used to represent the relationship of adolescent with parents, and the sibling relationship is often neglected in the context of problem behavior. To conclude, the results of the current study underline that it is important to know that our results show that investing in father-adolescent and sibling relationships specifically may also contribute to a positive change in adolescent problem behavior.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A full specification of the model can be obtained through the first author.

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables (Vol. 8). Wiley New York.

- Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., Van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.179

- Branje, S. J. T. (2008). Conflict management in mother–daughter interactions in early adolescence. Behaviour, 145, 1627–1651. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853908786131315

- Buist, K. L. (2010). Sibling relationship quality and adolescent delinquency: A latent growth curve approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020351

- Buist, K. L., Deković, M., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2011). Dyadic family relationships and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: Effects of positive and negative affect. Family Science, 2, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2011.601895

- Buist, K. L., Deković, M., Meeus, W., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2002). Developmental patterns in adolescent attachment to mother, father and sibling. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015074701280

- Buist, K. L., Paalman, C. H., Branje, S. J. T., Deković, M., Reitz, E., Verhoeven, M., Meeus, W. H. J., Koot &, H. M., & Hale III, W. W. (2015). Longitudinale effecten van kwaliteit van de broer/zus-relatie op probleemgedrag van adolescenten: Een cross-etnische vergelijking [Longitudinal effects of sibling relationship quality on adolescent problem behavior: A cross-ethnic comparison]. Kind en Adolescent, 36, 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12453-015-0076-1

- Buysse, W. H. (1997). Behaviour problems and relationships with family and peers during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 20, 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1997.0117

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259

- Cui, M., Conger, R. D., & Lorenz, F. O. (2005). Predicting change in adolescent adjustment from change in marital problems. Developmental Psychology, 41, 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.812

- Cui, M., & Donnellan, M. B. (2009). Trajectories of conflict over raising adolescent children and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00614.x

- Defoe, I. N., Keijsers, L., Hawk, S. T., Branje, S., Dubas, J. S., Buist, K., Frijns, T., van Aken, M. A. G., Koot, H. M., van Lier, P. A. C., & Meeus, W. (2013). Siblings versus parents and friends: Longitudinal linkages to adolescent externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12049

- Deković, M., Buist, K., & Reitz, E. (2004). Stability and changes in problem behavior during adolescence: Latent growth analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027305312204

- Duncan, T. E., Duncan, S. C., & Stryker, L. A. (Eds.). (2006). Latent variable growth curve modeling. Concepts, issues, and applications (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dunn, J., Deater-Deckard, K., Pickering, K., Golding, J., & the Alspac Study Team. (1999). Siblings, parents, and partners: Family relationships within a longitudinal community study. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40, 1025–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00521

- Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. In M. Tonry & N. Morris (Eds.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research (Vol. 7, pp. 189–250). Chicago University Press.

- Feinberg, M. E., McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., & Cumsille, P. (2003). Sibling differentiation: Sibling and parent relationship trajectories in adolescence. Child Development, 74, 1261–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00606

- Feinberg, M. E., Reiss, D., Neiderhiser, J. M., & Hetherington, E. M. (2005). Differential association of family subsystem negativity on siblings’ maladjustment: Using behavior genetic methods to test process theory. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.601

- Fosco, G. M., Stormshak, E. A., Dishion, T. J., & Winter, C. E. (2012). Family relationships and parental monitoring during middle school as predictors of early adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41, 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.651989

- Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016

- Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of network of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130905

- Glasgow, K. L., Dornbusch, S. M., Troyer, L., Steinberg, L., & Ritter, P. L. (1997). Parenting styles, adolescents’ attributions, and educational outcomes in nine heterogeneous high schools. Child Development, 68, 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01955.x doi: 10.2307/1131675

- Henggeler, S. W. (2015). Effective family-based treatments for adolescents with serious antisocial behavior. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior (pp. 461–475). Springer.

- Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. University of California Press.

- Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eichelsheim, V. I., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8

- Hollenstein, T., Granic, I., Stoolmiller, M., & Snyder, J. (2004). Rigidity in parent-child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JACP.0000047209.37650.41

- Keijsers, L., Loeber, R., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2012). Parent-child relationships of boys in different offending trajectories: A developmental perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1222–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02585.x

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Kumpfer, K. L., Whiteside, H. O., Greene, J. A., & Allen, K. C. (2010). Effectiveness outcomes of four age versions of the strengthening families program in statewide field sites. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 14, 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020602

- Kurdek, L. A. (1999). The nature and predictors of change in marital quality for husbands and wives over the first 10 years of marriage. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1283–1296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1283

- Li, L., Bai, L., Zhang, X., & Chen, Y. (2018). Family functioning during adolescence: The roles of paternal and maternal emotion dysregulation and parent-adolescent relationships. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 27, 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0968-1

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2290157 doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

- Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (2014). Age-crime curve. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology & Criminal Justice (pp. 12–18). Springer.

- Maciejewski, D. F., Lier, P. A. C. van, Branje, S. J. T., Meeus, W. H. J., & Koot, H. M. (2015). A 5-year longitudinal study on mood variability across adolescence using daily diaries. Child Development, 86, 1908–1921. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12420

- Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & Oliver, P. H. (2004). Links between marital and parent-child interactions: Moderating role of husband-to-wife aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 753–771. https://doi.org/10.10170S0954579404004766 doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004766

- Mathijssen, J. J. J. P., Koot, H. M., Verhulst, F. C., de Bruyn, E. E. J., & Oud, J. H. L. (1998). The relationships between mutual family relations and child psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00344 doi: 10.1017/S0021963098002388

- Miller, S., Malone, P. S., Dodge, K. A., & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2010). Developmental trajectories of boys’ and girls’ delinquency: Sex differences and links to later adolescent outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10802-010-9430-1 doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9430-1

- Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Berg, S. van den (2003). Internalizing and externalizing problems and correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022858715598

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Pardini, D. A., Waller, R., & Hawes, S. W. (2015). Familial influences on the development of serious conduct problems and delinquency. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior (pp. 201–220). Springer International Publishing.

- Rasbash, J., Jenkins, J., O’Connor, T. G., Tackett, J., & Reiss, D. (2011). A social relations model of observed family negativity and positivity using a genetically informative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 474–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020931

- Reitz, E., Prinzie, P., Dekovic, M., & Buist, K. (2007). The role of peer contacts in the relationship between parental knowledge and adolescents’ externalizing behaviors: A latent growth curve modeling approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9150-6

- Scharf, M., Shulman, S., & Avigad-Spitz, L. (2005). Sibling relationships in emerging adulthood and in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558404271133

- Stanger, C., Achenbach, T. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (1997). Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579497001053

- Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00001

- Steinberg, L., & Sheffield Morris, A. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

- Stewart, R. B., Verbrugge, K. M., & Beilfuss, M. C. (1998). Sibling relationships in early adulthood: A typology. Personal Relationships, 5, 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00159.x

- Thornberry, T. P. (2014). Interactional theory of delinquency. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 2592–2601). Springer.

- Tremblay, R. E., & Nagin, D. S. (2005). The developmental origins of physical aggression in humans. In R. E. Tremblay, W. H. Hartup, & J. Archer (Eds.), Developmental origins of aggression (pp. 83–106). Guilford Press.

- Ullman, J. B. (2001). Structural equation modeling. In B. G. Tabachnick & L. S. Fidell (Eds.), Using multivariate statistics (pp. 653–771). Allyn and Bacon.

- Van Geert, P., & Steenbeek, H. (2005). Explaining after by before: Basic aspects of a dynamic systems approach to the study of development. Developmental Review, 25, 408–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.10.003

- Verhulst, F. C., van der Ende, J., & Koot, H. M. (1997). Handleiding voor de youth-self-report [manual for the youth self-report]. Afdeling jeugdpsychiatrie, Sophia Kinderziekenhuis/Academisch Ziekenhuis Rotterdam/Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

- Whiteman, S. D., Jensen, A. C., & Maggs, J. L. (2014). Similarities and differences in adolescent siblings’ alcohol-related attitudes, use, and delinquency: Evidence for convergent and divergent influence processes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9971-z

- Whiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Longitudinal changes in marital relationships: The role of offspring’s pubertal development. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 69, 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00427.x

- Widaman, K. F. (2006). III. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 71, 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.00404.x

- Windle, M. (2000). A latent growth curve model of delinquent activity among adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 4, 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0404_2

- Yoder, J. R., Brisson, D., & Lopez, A. (2016). Moving beyond fatherhood involvement: The association between father–child relationship quality and youth delinquency trajectories. Family Relations, 65, 462–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12197