ABSTRACT

The Shift-of-Strategy (SoS) approach is an extension of the Strategic Use of Evidence technique. In the SoS approach, interviewers influence suspects’ strategies to encourage suspects to become more forthcoming with information by challenging discrepancies between their statements and the available evidence, in a non-accusatory manner. Our aim was to test the effectiveness of two variations of the SoS approach, one in which the interviewer responded immediately to any discrepancies with the evidence (Reactive) and one in which the interviewer only responded to severe discrepancies (Selective). We predicted that the SoS approach conditions would be more effective at eliciting new information from mock suspects, compared to direct questioning. In a laboratory experiment, N = 300 mock suspects committed a simulated crime and were interviewed using one of the two versions of the SoS approach or with an interviewing approach that did not involve the presentation of evidence. The Reactive version of the SoS approach was more effective than direct questioning at eliciting new information from mock suspects. The Reactive technique also led participants to change their strategies during the interview. The present experiment provided initial support for the core principles of the SoS approach.

A common challenge in human intelligence and law enforcement contexts is the collection of information from people who are willing to speak to an interviewer but are also motivated to conceal some or all of the critical information they possess. The present study concerns a technique designed to improve interrogators’ ability to obtain new information from such criminal suspects or intelligence sources: the Shift-of-Strategy (SoS) approach. The SoS approach is an extension of the Strategic Use of Evidence (SUE) interviewing technique (Hartwig et al., Citation2005) and is based on empirical research, psychological theory, and practitioner experience (for an introduction, see Granhag & Luke, Citation2018). Here, we present a laboratory test of variations of the SoS approach and provide initial support for its effectiveness. To contextualize the technique, we first provide a review of research on counter-interrogation strategies. We then discuss the research on the Strategic Use of Evidence technique, which has led to the development of the SoS approach.

Counter-interrogation strategies

The SoS approach is grounded in an understanding of how suspects tend to act in interviews in order to cope with the challenge of being questioned – that is, their counter-interrogation strategies. Research on counter-interrogation strategies has primarily focused on law enforcement contexts (but see Alison et al., Citation2014, Citation2013), in which a central objective of an interview is to ascertain whether a suspect is guilty or innocent. When questioned, suspects – regardless of their actual culpability – are typically motivated to be perceived as credible and to convince investigators that they are innocent. Despite the essentially identical goals, innocent and guilty suspects tend to adopt different strategies to convince interviewers that they are innocent (for a more complete discussion of counter-interrogation strategies, see Granhag & Hartwig, Citation2014).

Research on counter-interrogation strategies indicates that innocent suspects tend to adopt straightforward strategies in which they ‘tell the truth as it happened’ (Hartwig et al., Citation2007) and provide ample disclosures of information (Luke et al., Citation2014a). A central threat to their credibility is the interviewer failing to obtain an accurate account of what happened, and as such, there are clear incentives to being forthcoming (Hartwig et al., Citation2014a), except in situations in which an otherwise innocent suspect has other information they are motivated to conceal (Clemens & Grolig, Citation2019).

As with innocent suspects, guilty suspects’ strategic choices are thought to derive from their motivations and goals, but they are motivated to maintain their credibility by keeping the interviewer unaware of incriminating information. Thus, guilty suspects tend to be more cautious and strategic with their disclosures of information. When possible, they often try to keep their stories short and simple (Alison et al., Citation2014; Hartwig et al., Citation2007). However, when guilty suspects are aware that the interviewer may possess information that could contradict a bare-bones denial, guilty suspects often adopt strategies that are more forthcoming and provide stories that attempt to account for this information, without making admissions of guilt (Hartwig et al., Citation2005; Luke et al., Citation2014a; Luke et al., Citation2016b). Thus, guilty suspects tailor their information disclosures to their perceptions of what the interviewer already knows in order to maintain credibility (Alison et al., Citation2014; Brimbal & Luke, Citationin press).

The strategic use of evidence

The empirically-based understanding of suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies reviewed above serves as the foundation for the Strategic Use of Evidence (SUE) technique (Granhag & Hartwig, Citation2014). The SUE technique offers specific tactics that can be organized into three categories (1) pre-interview assessment of the background information (evidence), (2) the questions posed during the interview, and (3) the disclosure of the evidence (for a detailed account, see Granhag & Hartwig, Citation2014). Using the SUE technique in its most basic version, the interviewer first elicits an account of what happened (Hartwig et al., Citation2005), then asks tactical questions that makes the suspect address the evidence, without revealing the evidence (Granhag & Hartwig, Citation2014), and finally (possibly) discloses the evidence guided by the Evidence Framing Matrix (Granhag et al., Citation2013). The suspect’s account can then be assessed in terms of statement-evidence inconsistencies – that is, discrepancies between the suspect’s account and the available evidence, and/or in terms of within-statement inconsistencies – that is, discrepancies within the suspect’s account.

As discussed above, innocent suspects are quite prone to remaining close to the truth, and their stories contain few, if any, statement-evidence inconsistencies. Guilty suspects, in contrast, tend to avoid disclosing potentially incriminating information, unless they know that the interviewer is already knowledgeable about some details. When an interviewer withholds evidence, guilty suspects are much more likely to contradict the facts implied by the evidence, as they are unable to adapt their statements to what the interviewer already knows. Statement-evidence inconsistencies have been found to be a powerful indicator of deceit in numerous laboratory studies (for a review, see Hartwig et al., Citation2014a). Innocent and guilty suspects tend to differ in their consistency with the evidence in a magnitude that is plainly visible. Brimbal and Luke (Citationin press) estimated this difference (when suspects were questioned using the SUE technique) as d = 1.83, 95% CI [1.34, 2.32] – an effect size similar to the difference in height between men and women (Simmons et al., Citation2013). Thus, the SUE technique can be used, for example, to elicit cues to deception from suspects in order to assess their credibility and help determine culpability (Luke et al., Citation2017b). Laboratory experiments and training studies on the SUE technique have demonstrated the usefulness of interview tactics designed to take advantage of suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies (Hartwig et al., Citation2006; Hartwig et al., Citation2014a; Luke et al., Citation2016a).

Influencing suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies

Over the last several years, researchers have tested modifications of the SUE technique as methods for eliciting concealed information. In a series of laboratory studies, researchers have tested an approach known as SUE-Confrontation (see Tekin, Citation2016). This variation of the SUE technique involves giving the suspect the impression that the interviewer is substantially knowledgeable about the suspect’s activities. This is done by initially withholding information and evidence and then, after they provide a partial account of their activities, alerting suspects to the fact their statements have contradicted the evidence (or have been consistent with the evidence). As the interview proceeds, the suspect can gradually learn the pattern: that the interviewer typically knows more than they initially let on. The suspect then overestimates the interviewer’s knowledge and, later in the interview, is more likely to reveal truthful information about their activities to avoid damaging their credibility by contradicting something that the interviewer knows but has not yet revealed. Thus, the purpose of this approach is to induce guilty suspects to change their strategy from a generally withholding one to a more forthcoming one, while also providing an opportunity for innocent suspects to give a statement that is in line with the evidence. Initial experimental testing of this approach by Tekin and her colleagues (Citation2015, Citation2016) produced promising results, suggesting that the technique was effective at eliciting concealed information from suspects.

More recently, Granhag and Luke (Citation2018) reviewed the literature on counter-interrogation strategies and on the variations of SUE technique and (re)conceptualized these techniques into what they called the Shift-of-Strategy (SoS) approach. The name of the approach reflects its focus on influencing a suspect’s counter-interrogation strategy through the course of an interrogation – from generally withholding toward more forthcoming with guarded information – and the name places emphasis on the purpose of the technique (i.e. influencing strategies), rather than on some of the tactics used (i.e. confrontation). The SoS approach is a substantial expansion of prior work on the SUE-Confrontation technique, which principally focused on specific tactics for the disclosure of evidence. Beyond a set of evidence disclosure tactics, the SoS approach is a collection of strategies for managing information and social principles to guide interviewers.

The purpose of the SoS approach is to collect information from suspects or other intelligence sources who are motivated to appear credible. The approach can be considered an extension of the SUE technique, based on the same foundational understanding of suspect strategies, but it differs in its focus and scope. Whereas many SUE interviews may have deception detection or credibility as a main objective, the principle purpose of the SoS approach is obtaining previously unknown information. This purpose is not, however, incompatible with detecting deception through statement-evidence inconsistencies.

The SoS approach can be briefly summarized as the following principles: (1) Fostering a social environment in which the suspect is motivated to ‘stay in the game’ and maintain, bolster, and recover his or her credibility; (2) creating the impression that interviewer is knowledgeable about the source’s activities through strategic disclosure of evidence; (3) reinforcing and discouraging, respectively, suspect behaviors that are desirable and undesirable (e.g. deceptive responses), by handling statement-evidence (in)consistencies in a manner that follows the first two principles.

Past research supports the first two principles. The third principle has not been directly assessed in empirical research. With regard to the first principle, in the SoS approach, it is essential that the source continues to be motivated to speak to the interviewer. That is, interviewers should avoid situations in which the suspect believes there is little or no hope for maintaining or recovering their credibility. Experimental and observational research suggests that providing a nonjudgmental and non-guilt-presumptive environment can increase the likelihood suspects will disclose concealed information (Alison et al., Citation2013; May et al., Citation2017; Surmon-Böhr et al., Citation2020). For these reasons, the SoS approach avoids direct accusations of culpability or of deception. When identifying an inconsistency or following up on a topic, the interviewer should request a further explanation without suggesting that the suspect is lying or attempting to hide something.

The second principle is supported by research on the SUE technique and the more specific SUE-Confrontation variant, briefly reviewed above. Other research also suggests that suspects who perceive their interviewers to be knowledgeable about their activities are more prone to disclose information, especially information they believe the interviewer already knows. Indeed, this relationship between perceptions of interviewer knowledge and information disclosure is one of the foundations of the interviewing tactics of Hanns Scharff (that is, the Scharff technique) – which have received empirical support in a series of laboratory experiments (e.g. Granhag et al., Citation2016; Oleszkiewicz et al., Citation2014; see Luke, Citation2021), in addition to being anecdotally supported by Scharff’s own and some of his prisoners’ experiences (Scharff, Citation1950; Toliver, Citation1997). In the SoS approach, the interviewer influences the suspect’s perception of what and how much the interviewer knows through disclosures of evidence and identifying inconsistencies between the suspect’s statement and the evidence. In the SoS approach the elicitation of statement-evidence (in)consistencies serves the tactical purpose of encouraging suspects to shift strategies, but unlike in the original conceptualization of the SUE technique (Hartwig et al., Citation2005), these (in)consistencies are not ends in themselves, since detecting deception or assessing credibility is not the central goal.

The third principle has received little or no attention in the existing literature. In their introduction to the SoS approach, Granhag and Luke (Citation2018) emphasized the importance of further research that develops more specific recommendations for interviewers to handle a suspect’s inconsistencies in order to encourage suspects to shift strategies to become more forthcoming. The development of such tactics was one of the goals of the present study.

The present study

Here, we tested two variations of the SoS approach that we thought might be effective at prompting guilty suspects to shift from a relatively withholding strategy to a more forthcoming strategy, and we were interested in assessing their effectiveness. We termed these variations the Selective technique and the Reactive technique. These two variations are similar in that they both follow the three principles described above, but they differ in the manner in which the interviewer responds to statement-evidence inconsistencies by the suspect. In the Selective technique, the interviewer only challenges severe inconsistencies between the suspect’s statement and the evidence. This approach can be seen as being relatively cautious about keeping the suspect ‘in the game.’ That is, it takes care not to challenge the suspect too frequently or too much, to reduce the risk of discouraging from engaging further with the interviewer (e.g. giving up on trying to appear credible). In the Reactive technique, the interviewer challenges inconsistencies with the evidence, even relatively minor ones, without delay. This approach reflects a different concern than the Selective technique; it is more concerned with ensuring that the suspect does not infer that deception is a productive strategy. It attempts to provide immediate feedback that statement-evidence inconsistencies are damaging to the suspect’s credibility. In both the Selective and Reactive technique, inconsistencies were challenged in a nonjudgmental, non-accusatory manner (the techniques are described in more detail below). We compared these versions of the SoS approach to a technique that did not involve any disclosure of evidence but instead relied on direct questioning. Both the Selective and Reactive techniques are designed to work on the same psychological principles and to accomplish the same objective (i.e. to prompt shifts toward more forthcoming strategies), but we were uncertain which, if either, version of the SoS approach would be more effective at serving its intended purpose. We limited the scope of the study to eliciting admissions from guilty suspect because research consistently finds that innocent suspects are typically forthcoming with critical information and that they are consistent with the evidence regardless of the interviewer’s tactics (e.g. Hartwig et al., Citation2014b; Luke et al., Citation2014b; Tekin, Citation2016).

Method

Hypotheses, procedures, materials, data exclusion criteria were registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) prior to data collection. The project was registered again prior to the completion of data collection to add analysis code (for the last registration, see https://osf.io/zgxft). Data, materials, and supplementary materials are available at https://osf.io/mfus8/. This research was conducted in accordance with applicable laws governing research with human participants, and it was approved by the IRB for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (Docket No. 475-19).

Participants

The sample size was determined in advance based on power calculations and resource constraints. We report all data exclusions. We aimed to recruit N = 300 adults from the local community to serve as participants. We could reasonably recruit this number of participants given available funding. Power calculations indicated that this sample size would permit us to detect effects of d = .40 with .80 power when comparing between each of the three groups in the design. Each participant was paid 100 Swedish kronor (SEK; approximately $9) for their time.

We recruited a total of N = 318 participants. Of these, 12 were excluded from the analyses because they failed to follow the experimental instructions. An additional five were excluded due to technical problems in the recording of their data. One participant was excluded because an error by the research staff resulted in the interview being conducted incorrectly. We recruited participants until we reached our target of N = 300 participants with usable data. In the final sample, participants were 63.7% female (n = 188), 36.3% male (n = 109), and 1.00% other genders (n = 3). They ranged in age from 18 to 74 years (M = 29.7, SD = 10.8, mdn = 26).

Outliers

Given the nature of our dependent measures, we did not expect outliers, so we did not plan to exclude outliers from the analyses. However, after data were collected, we detected two participants who volunteered an unusually high amount of information (without admitting guilt) in response to the opening free-recall question of the interview, prior to the implementation of any of the techniques. These two participants were in the Selective condition (described below). For the main analyses, we have retained these participants as per the registered plan. However, we also describe how their removal impacts the results of the main hypothesis test.

Design and procedure

Mock crime

Participants were randomly assigned to take part in one of three mock crimes, each involving three discrete phases. After obtaining informed consent, the experimenter provided participants with detailed instructions about how to carry out the mock crime to which they were assigned. For each crime, participants were asked to imagine they were part of a radical political organization that was conducting an unlawful investigation of possible wrongdoing occurring at the university at which the experiment was being conducted. Mock crimes consisted of simulated acts of espionage (e.g. stealing documents, collecting a hidden audio recorder). After completing the mock crime, participants returned to the laboratory and gave the experimenter any materials they collected as part of the activities. Each phase of each crime was constructed in such a way that the experimenter could easily verify whether the participant had completed the task correctly. For example, for a task that demanded the theft of documents, the experimenter verified that the participant indeed had the documents.

We had no hypotheses about differences between the crimes. Rather, we incorporated these variations to decrease the plausibility that results were due to the idiosyncratic features of any single mock crime scenario. Additionally, to account for possible effects of the order in which the phases occurred in each mock crime, participants were assigned to complete the mock crime in a randomized order. With three phases, each crime had six possible orders in which it could be completed, resulting in a total of 18 possible crime-order sequences to which participants could be assigned. This randomization was logistically demanding, but it ensured that any extraneous features of the mock crime activities (such as differing levels of suspiciousness; see Srivatsav et al., Citation2021) were balanced across participants and conditions (at least in expectation), and again, it reduces the plausibility that results may be due to artifacts of the mock crime procedures. For more detail on each mock crime and its phases, see the supplemental materials (https://osf.io/mfus8/), which contain the instructions participants received, both in their original language and translated to English.

Interview

After returning to the laboratory, participants were informed they would be interviewed as suspects of the mock crime they had just committed. They then completed a brief pre-interview questionnaire and were given a few minutes to prepare for the interview. On this questionnaire, participants were asked two exploratory items: how confident they were in their ability to convince the interviewer of their innocence and how motivated they were to convince the interviewer. Data for all items are available in the online supplemental materials.

Participants were randomly assigned to be questioned with one of three interview strategies (described in more detail below): (1) Direct, (2) Selective, and (3) Reactive. Participants were questioned by one of three interviewers (two female, one male). To model the circumstances under which the SoS approach is applicable, participants were motivated to convince the interviewer that they were innocent. Specifically, they were informed that if they convinced the interviewer they were innocent, they would be entered into a lottery to win 500 SEK (approximately $47). Interviews were video recorded for subsequent transcription and coding.

Interviewers were trained to closely follow the procedures. Interviews were structured to model a situation in which the interviewer had access to information about some, but not all, of the suspect’s activities. More specifically, the interviews were designed such that the interviewer had evidence about the suspect’s activities for the first two phases of the mock crime but lacked information about the third. Thus, the third phase was a critical phase, in that any information the participant provided about activities in that phase represented new intelligence collected by the interviewer. The interviews covered the three phases of the crime in the chronological order in which the suspect completed the mock crime. For the first two phases of the mock crime, the interviews were scripted such that the interviewer asked specific questions about the suspect’s activities (and in two of three conditions, the interviewer presented evidence; described in more detail below). For the third phase of the mock crime, the interviewer only asked open-ended questions and generic follow-ups. In all conditions, the interviewer did not present any evidence concerning the third phase. To transition between discussing each phase (including the third), the interviewer prompted the participant to describe what they did next, and the interviewer only followed up with more specific evidence-informed questions in the first and second phases.

In each of the three mock crimes, there was one piece of eyewitness evidence, one piece of CCTV evidence, and one piece of fingerprint evidence. Each of these three pieces of evidence was yoked to a specific activity in each mock crime. Thus, through the randomization of the order of the crime phases, the type of evidence presented in the interview was also balanced (in expectation) across participants and conditions. This balancing is potentially important, since the type and reliability of evidence may have an impact on suspects’ responses when the evidence is presented (Brimbal & Luke, Citationin press). In reality, the evidence used in the interviews was not collected. Rather, as in previous experiments using similar methods (e.g. Hartwig et al., Citation2005; Luke et al., Citation2016a), the existence of the evidence was guaranteed to be plausible by the design of the mock crime activities (e.g. the participant could not steal the intended documents without touching an object on which the interviewer claimed to have recovered fingerprints). Crucial for the testing of the SoS approach, which cannot and should not be used with false evidence ploys, this design ensured that we had created a situation in which it was plausible that the interviewer actually had the evidence they used in the interview.

Interview conditions

All interview protocols (a total of 54) corresponding to the combinations of the three interview conditions, three mock crimes, and the orders in which mock crimes were completed are available in their original language on OSF (https://osf.io/mfus8/). In all conditions, interviewers worked to create a non-accusatory and supportive environment for the suspect, by encouraging the source to report as much information as possible and by not making any direct accusations of deception or culpability. Prior to the implementation of any tactics that distinguished the three techniques, all interviews began with an open-ended question about the suspect’s recent activities (i.e. ‘In as much detail as possible, would you tell me what you did while you were at the Department of Psychology today?’), with a single follow-up question to probe for more information (i.e. ‘Did you do anything else while you were at the Department of Psychology?').

In the Direct condition, the interviewer asked a series of open questions, followed by more specific and focused questions about the source’s activities (viz. following the ‘funnel structure’ recommended by the SUE technique; Hartwig et al., Citation2014b). These questions were identical to those asked in the SoS conditions, but in the Direct condition, the interviewer did not comment on the veracity of the suspect’s account and did not challenge any discrepancies with the evidence (i.e. statement-evidence inconsistencies). This condition represents a situation in which the interviewer possesses some evidence about the source’s behavior but withholds that information (similar to a ‘late disclosure of evidence’ approach in the SUE technique). In all conditions, consistent with general recommendations in investigative interviewing, the interviewer encouraged the source to be as detailed as possible and probed for further information using standard follow-up prompts (e.g. ‘Tell me more about X.’).

In the two SoS conditions, the interviewer challenged statement-evidence inconsistencies in different ways. In both conditions, interviewers listened actively to the suspects’ statements and noted if the suspects’ statements were contrary to the evidence they had. In the Reactive condition, the interviewer responded to statement-evidence inconsistencies immediately by pointing out the inconsistency between what the suspect was saying and what the interviewer knew, presenting known evidence, and encouraging the participant to respond to the contradicted evidence. In the Selective condition, the interviewer responded (in the same manner as the Reactive strategy) only to severe inconsistencies (i.e. denying being at the location in which the activities occurred) but did not react to minor inconsistencies with the evidence (e.g. leaving out some known incriminating details while acknowledging being at the scene of the crime).

In both SoS conditions, the interviewer made no more than two challenges for each piece of evidence. The evidence was presented in line with the recommendations of the evidence framing matrix (see Granhag et al., Citation2013). This approach was taken in order to give participants up to two opportunities to change their story to become consistent with the evidence. First, the interviewer presented the evidence at a level of specificity corresponding to the inconsistency (e.g. if the participant denied being in a place the interviewer knew they were, the interviewer would say that the evidence showed they were there). If the participant’s response was still inconsistent with the evidence, the interviewer then presented the evidence in full. For example, if the participant initially denied being in the location at which the crime occurred, the interviewer would state that there was evidence placing them at the scene. Alternatively, if the participant denied touching an object on which the interviewer had fingerprints, the interviewer would state that there was information indicating that they had touched this object (without specifying that the source of the information, i.e. fingerprints). If the participant provided a statement consistent with the evidence (before or after the presentation of evidence), the interviewer affirmed that the participant’s statement was in line with what they knew based on the available evidence.

To ensure compliance with all interview procedures, the three interviewers and two additional research assistants reviewed all the transcribed interviews. Following this review, they noted that the interviewers followed the procedures in all cases as stipulated, but each interviewer seemed to differ in style (e.g. some asked more or fewer follow-up questions to clarify the suspect’s account).

Dependent measures

Information disclosure

As the primary dependent variable of interest, we measured participants’ disclosure of (truthful) information for each phase of the mock crime they committed (i.e. related to each discrete activity they performed). For each phase of each mock crime, we identified five details with increasing specificity and coded whether the participant’s statement to the interviewer revealed those truthful details, at any point in the interview. The revelation of each detail necessarily implied revelation of less specific details (i.e. admitting to the most specific detail entailed admitting to all the less specific details), thus forming a 0–5 score for each phase of each mock crime. Again, each mock crime consisted of three phases, for a total of three observations per participant (N = 900 observations). The coding scheme is available online at https://osf.io/pq5hs/. Two independent raters coded all 300 interview transcripts to create this measure. Agreement between raters was high, ICC = .88, 95% CI [.87, .90]. Disagreements between the raters were resolved through discussion.

Self-assessment of performance

We assessed participants’ perception of how successful they were at convincing the interviewer they were innocent using self-reported endorsement of four statements about their performance in the interview (e.g. ‘I am confident that the interviewer thought I was innocent.’). Each statement was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘Strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘Disagree’, 3 = ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, 4 = ‘Agree’, 5 = ‘Strongly agree’). Ratings on these statements were averaged into a composite measure (some items reverse coded so that higher values indicate more positive self-assessments). The scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, standardized α = .72. Exact items in their original language, as well as more detailed information about the psychometric properties of this measure, including evidence for the scale’s unidimensionality, can be found in supplemental materials on OSF (https://osf.io/mfus8/).

Interaction quality

We assessed participants’ perceptions of the quality of the interaction and the interviewer using their self-reported endorsement of lists of positive and negative adjectives (6 for the interaction, i.e. smooth, awkward, comfortable, difficult, open, and pleasant; and 6 for the interviewer, i.e. friendly, pressing, aggressive, sympathetic, interested, and harsh). Each adjective was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘Strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘Disagree’, 3 = ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, 4 = ‘Agree’, 5 = ‘Strongly agree’). Each list of adjectives was averaged into a composite measure (some items reverse coded so that higher values indicate more positive assessments), forming a scale for participants’ perceptions of the interview and of the interviewer. The scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, standardized α = .76 for the interview scale and .71 for the interviewer scale. Exact items in their original language, as well as more detailed information about the psychometric properties of these measures, including evidence for the scales’ unidimensionality, can be found in supplemental materials on OSF (https://osf.io/mfus8/).

Exploratory measures

We also measured several variables for which we had no hypotheses.

Volunteered information

Two independent raters examined only the free-recall section of each interview to code how much information participants revealed prior to the implementation of any of the interview techniques. These information disclosures were coded using the same scheme as the information disclosure coding described above. Thus, for each participant, we obtained three measures (one for each mock crime phase) of how much information they volunteered without prompting. Agreement between raters was acceptable, ICC = .70, 95% CI [.66, .73]. Disagreements between the raters were resolved through discussion.

Evidence presentation

In the Selective and Reactive conditions, we counted the number of times the interviewer presented evidence in response to a statement-evidence inconsistency in the first two phases of the interview (i.e. the phases for which the interviewer had evidence). For each phase, the frequency of evidence presentations could vary from 0 to 2 (see the description of the evidence presentation procedures above). We coded this variable primarily to assess the difference between the Selective and Reactive conditions – that is, to see if the conditions differed in evidence presentation in practice.

Self-reports of strategies

The pre- and post-interview questionnaires contained self-report questions about whether the participant had a strategy during the interview and whether they changed strategies during the interview.

Research questions

Information disclosure

Our main research questions concern the comparison of the two SoS conditions to the direct questioning condition, with regard to sources’ disclosure of information. We were uncertain whether or how the SoS conditions would differ from each other. Broadly, we predicted that the SoS conditions will induce a greater amount of critical information disclosure. More specifically, we expected that participants in the Direct condition would reveal relatively little information across the three themes of the interview, forming an approximately flat trajectory of information disclosure. In contrast, we expected that the SoS conditions would elicit more critical information as the interview progresses. Thus, for the SoS conditions, we expected a linear trajectory (i.e. gradual increases in disclosures) or quadratic trajectory (i.e. an increase at the second phase and then a decrease at the third phase) over time. A positive linear pattern would suggest that participants shifted their strategy to become increasingly forthcoming over time, as they form the impression that forthcomingness is an effective strategy. A negative quadratic pattern would suggest an initial shift toward forthcomingness followed by a decrease in disclosure when discussing the topic about which the interviewer had no evidence. Such a pattern might suggest that, even if the SoS approach is effective at inducing more forthcoming strategies and previously unknown information, focused questioning, directly presenting evidence, and requesting an explanation for inconsistencies may still prompt greater information disclosure. That is, the more thorough questioning in the first two phases might induce the suspect to reveal more information than they otherwise would, but the more barebones questioning in the third phase might result in an apparent decrease in information disclosure.

Self-assessment of performance

The SoS approach is thought to depend on keeping sources motivated to continue to work toward making the interviewer view them as credible. In particular, in order to maintain motivation, the SoS approach aims at not damaging a suspect’s impression of how credibly they are presenting themselves as. If a suspect comes to believe the interviewer does not believe them and cannot be persuaded, they are likely to become uncooperative. The SoS approach is not expected to improve suspects’ self-assessments of their performance in the interview, but it should not diminish them. We expected that (1) the SoS conditions would not assess their performance more poorly than the Direct condition, and (2) all conditions would on average assess their performance as better than the midpoint of the scale.

Interaction quality

Analogous to our predictions about self-assessed performance, we expected that (1) the SoS conditions would not assess the interaction or the interviewer more poorly than the direct questioning condition, and (2) all conditions would on average assess the interaction and the interviewer as more positive than the negative endpoint of the scale. In comparing ratings to the endpoint of the scale, we did not necessarily expect the interactions to be perceived as positive overall (given their adversarial nature), but we view this as a test of whether people perceive the interaction as not having been highly aversive overall. If the SoS conditions in particular are perceived highly negatively, it may indicate practical or ethical issues with the approach.

Registered analysis code

Prior to the completion of data collection and before examining the data, we registered R code (R Core Team, Citation2019) for hypothesis testing. The registered code can be found here: https://osf.io/pmxcq/. A detailed report of the hypothesis tests, as well as exploratory and supplemental analyses, can be found here: https://osf.io/ahwgs/. This report contains more technical detail than the results reported here (e.g. formulas for the models, rejected models, robustness tests).

Results

Hypothesis tests

Information disclosure

Descriptive statistics for information disclosure are presented in . displays the frequency distributions for information disclosure in each interview condition, in each phase of the interview. We tested our hypotheses about information disclosure using linear mixed models. To fit these models, we used the lme4 package (Bates et al., Citation2015) for R. We also used the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., Citation2017) to obtain Satterthwaite approximated degrees of freedom for the inferential tests. Satterthwaite degrees of freedom are recommended for their robustness and for their favorable error-control properties (S. Luke, Citation2017; Meteyard & Davies, Citation2020). Models predicting information disclosure included fixed effects for interview phase (orthogonal linear and quadratic contrasts) and interview technique (Direct, Selective, and Reactive, treatment coded with Direct as the reference group) and random intercepts for participants (nested in mock crime sequences) and for the three interviewers. Models were fit using maximum likelihood estimation. The model selection process began with a model with only main effects for interview phase (linear and quadratic trends) and for each interview technique. We compared the initial model to one that added interaction terms for the fixed factors. Adding the interactions did not significantly improve the fit with the data, χ2 (4) = 7.11, p = .13, log likelihood −1495.5 vs. −1491.9, so the model with only main effects was retained. The results of this model are displayed in .

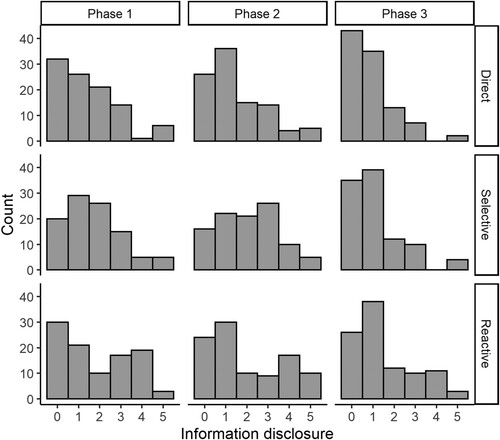

Figure 1. Frequency distributions for information disclosure in each interview phase, by interview condition.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for information disclosure in each interview phase, by interview condition.

Table 2. Linear mixed model predicting information disclosure.

Both the linear and quadratic contrasts across the interview phases were significant and negative, indicating that across conditions, there was a trend for participants to disclose less information in later phases of the interview. The quadratic contrast suggests this trend was curved, such that participants tended to provide about as much (or a little more) information in the second phase compared to the first, but then they tended to provide less in the third phase. This pattern is apparent in , which plots information disclosure across the phases in each condition as segmented lines. Participants in both the Selective and Reactive conditions provided significantly more information compared to the Direct condition. These results were partly in line with the hypotheses. Participants’ behavior in the Direct condition did not conform exactly to expectations (i.e. that participants’ information disclosure would have a relatively flat trajectory over time). Nevertheless, the results support the prediction that the Selective and Reactive conditions generated greater information disclosure.

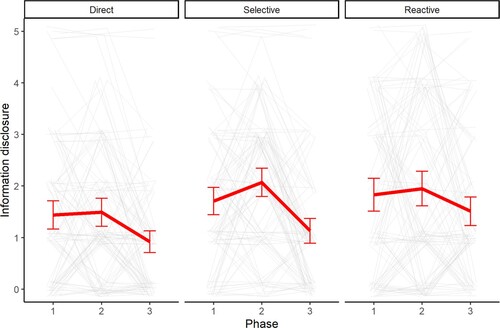

Figure 2. Trajectories of information disclosure across the three interview phases, by interview strategy. Information disclosure (0–5) is plotted on the vertical axis. Each panel represents an interview condition. Within each panel, the phases of the interview are plotted on the horizontal axis. The bold line tracks the group mean information disclosure at each phase (with a 95% confidence interval). The semi-transparent grey lines plot the trajectory of each individual participant in each condition, jittered slightly horizontally and vertically to more easily distinguish between lines.

However, two issues speak against the effectiveness of the Selective approach. First, it is apparent from the descriptive statistics and from the patterns displayed in that in the third phase of the interview, participants in the Selective condition disclosed an amount of information similar to those in the Direct condition, d = 0.18, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.46]. In contrast, participants in the Reactive condition tended to provide more information in the third phase compared to those in the Direct condition, d = 0.47, 95% CI [0.19, 0.75]. These differences can be seen in the distributions of information disclosure in third phase displayed in the rightmost panels of . Whereas the Direct and Selective conditions have similar distributions of information disclosure in the third phase, the Reactive condition’s distribution is notably different, with a heavier positive tail. Thus, it seems that the Selective approach was not more effective at collecting new information from the mock suspects.

Second, as we noted above, there were two participants in the Selective condition who volunteered nearly all the coded information during the initial open-ended questioning. These disclosures occurred before the tactics were implemented. Thus, it is quite likely their behavior is due to individual differences. To assess the impact of these outliers, we refit the model with their data removed. In the refitted model, the coefficient for the Selective condition was nonsignificant, b = 0.27 (0.16), t (297.00) = 1.75, p = .08. Other coefficients were substantively the same as in the previous fit.

In sum, the results provide support for the effectiveness of the Reactive approach for eliciting information, but the evidence in favor of the Selective approach is weaker (particularly for new information). These results hold across a variety of analytic approaches (e.g. regressions with alternate error distributions; cumulative link models) and also hold when using as a covariate the amount of information participants volunteered at the beginning of the interview. For robustness checks using alternative modeling approaches and for further information about the model with outliers removed, see the supplementary material (https://osf.io/mfus8/).

Random effects

A particularly useful aspect of these mixed effects models is that they can provide estimates of the variation due to participants’ individual differences, mock crimes, and interviewers. In , we can see that the variance of the random intercepts for participants is fairly large (ICC = .46), suggesting substantial individual differences in the propensity to disclose information. Indeed, the lines plotting individual participants’ trajectories in indicate considerable variation around the average trend. However, we can also see that there is quite little variation in the intercepts for the mock crimes and for the three interviewers.

Recall that we informally noted that the three interviewers seemed to have different styles despite implementing the techniques in a manner consistent with the protocols. In an exploratory follow up, we assessed a model that fit random slopes for each interviewer for each condition, to assess whether the interview strategies differed in their effectiveness among the interviewers. The fixed effects for this model were nearly identical to the model with only random intercepts for interviewers, and it did not fit the data significantly better than the previous model, χ2 (4) = 1.45, p = .84, log likelihood −1495.5 vs. −1494.8, suggesting that the interview techniques did not function significantly differently across the interviewers.

Self-assessment of performance

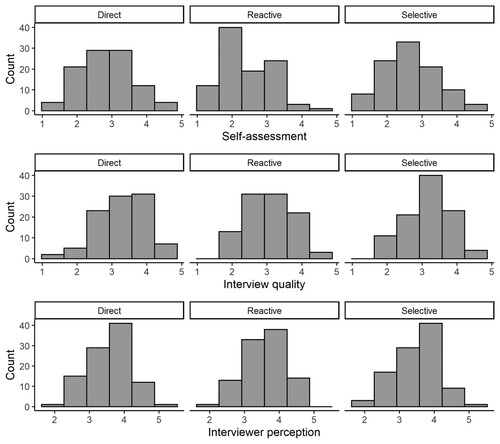

Frequency distributions for participants’ self-assessments of their performance in the interview are displayed in , and descriptive statistics are displayed in . Contrary to expectations, participants in all three conditions assessed their performance as significantly lower than the midpoint of the scale (see ). displays comparisons of each interview condition using Welch t-tests, and if these tests are nonsignificant, an equivalence test is reported, with bounds set at d = |0.20|. Equivalence tests were performed using the TOSTER package (Lakens, Citation2017) for R. Against predictions, participants in the Reactive condition rated their performance as significantly worse than those in the Direct condition and Selective condition. There was no significant difference between participants self-assessments in the Direct condition and the Selective condition, nor was there evidence of equivalence between these conditions. For an alternate approach to analyzing these data, arriving at the same conclusions, see https://osf.io/58pz4/.

Figure 3. Frequency distributions of self-assessment of performance, interview quality, and interviewer perception.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for self-assessment, interview quality, and interviewer perception with comparisons to specific scale points.

Table 4. Comparisons of each condition for self-assessment, interview quality, and interviewer perception.

Interaction quality

Frequency distributions for ratings of interview quality and interviewer perception are displayed in , descriptive statistics are reported in , and comparisons of each interview condition are reported in . For both interview quality and interviewer perception, participants’ ratings in all conditions were significantly above the negative endpoint of the scale, suggesting typically positive or neutral perceptions of the interaction and of the interviewer. Comparisons between each of the conditions on these two measures indicated that participants in the Reactive condition rated the quality of the interaction to be significantly lower than participants in the Direct condition. This result was counter to predictions. No other comparisons indicated significant differences, nor was there support for equivalence between the conditions in any comparison.

Exploratory analyses

Self-reported motivation

Before the interview, participants reported being relatively highly motivated to convince the interviewer they were innocent (M = 5.63, SD = 1.30, mdn = 6). Self-reported motivation did not significantly differ across the three interview conditions, F (2, 297) = 0.64, p = .52.

Volunteered information

In response to the initial question, prior to the implementation of any tactic, participants tended to reveal little or no information about the first (M = 0.42, SD = 0.75, mdn = 0), second (M = 0.41, SD = 0.78, mdn = 0), or third phase (M = 0.43, SD = 0.79, mdn = 0) of the mock crime activities.

Evidence presentation

In the Reactive condition, the interviewer presented evidence more frequently on average compared to the Selective condition, in both the first phase of the interview (Reactive: M = 1.38, SD = 0.74, mdn = 2; Selective: M = 1.11, SD = 0.79, mdn = 1), t (138.23) = 2.06, p = .04, d = 0.35 95% CI [0.11, 0.68], and in the second phase (Reactive: M = 1.24, SD = 0.84, mdn = 1; Selective: M = 0.91, SD = 0.88, mdn = 1), t (138.40) = 2.25, p = .03, d = 0.38 95% CI [0.04, 0.71]. These differences likely reflect the stipulation that the interviewer challenged only severe inconsistencies (i.e. denying being in the location in which the activities occurred) in the Selective condition, whereas the interviewer challenged even minor inconsistencies in the Reactive condition.

Self-reported changes in strategy

After participants were interviewed, we asked them if they had changed their strategy during the interview. Participants in the Reactive condition (33.3%, 33/99) reported changing their strategy more frequently than those in the Direct condition (12.2%, 12/98), χ2 (1) = 11.26, p < .001, difference 21.1%, 95% CI [9.8, 32.4]. Participants in the Selective condition (26.0%, 26/100) also reported changing their strategy more frequently than those in the Direct condition, χ2 (1) = 5.18, p = .02, difference 13.8%, 95% CI [3.0, 24.6]. Participants in the Reactive condition did not significantly differ from those in Selective condition in the rate at which they reported changing their strategy, χ2 (1) = 0.96, p = .32, difference 7.3%, 95% CI [−5.4, 20.0].

Those who provided an explanation for how and why they changed their strategy often noted that they needed to adjust in response to what the interviewer knew. For example, one participant noted, ‘I realized that the interviewer knew quite a lot, so I tried to offer explanations for what I did’ (Participant 10). Another noted that he changed strategy ‘when [he] discovered that the interviewer knew more than [he] thought’ (Participant 29). Some made specific reference to the presentation of evidence influencing their change in strategy: ‘I realized it was safer to stick as close to the truth as possible since [the interviewer] doubted my story because there was a witness’ (Participant 88).

As an extension of the present project, Håkansson (Citation2020) coded the responses from the open-ended questions about counter-interrogation strategies. Her data indicate that a total of 25 participants explicitly indicated a strategy of attempting to explain away of the interviewer’s evidence (inter-rater agreement was high, Gwet’s AC = .96). The vast majority of the participants reporting this strategy (22/25, 88%) indicated they changed their strategy during the interview. Of those 25, one (4%) was in the Direct condition, 7 (28%) were in the Selective condition, and 17 (68%) were in the Reactive condition. As an example, one participant wrote, ‘In the beginning I was going to deny everything, but when it was explained that my fingerprints were found, I changed my strategy to explain that I had been at the locations, but for innocent and random reasons’ (Participant 13). Taken together, these exploratory analyses support the notion that the Reactive technique was effective at sensitizing at least some participants to the importance of responding to the interviewer’s evidence in a way that allowed them to maintain a credible appearance.

There is sufficiently rich information in participants’ responses to the open-ended prompts concerning their strategies to fill another article, so here we refrain from more thorough analyses of these qualitative data. For a more detailed (but not exhaustive) discussion of participants’ self-reported strategies, see Håkansson (Citation2020). For transcriptions of participants’ responses in their original language, see the data files available online (https://osf.io/3ea49/).

Discussion

The SoS approach is dependent on all three sets of tactics that the SUE technique offers (Granhag & Hartwig, Citation2014). First, for the SOS approach the interviewer must carefully assess the background evidence and select which parts to ask about. Second, they must obtain an account and then ask tactical questions without revealing the evidence. Finally, the interviewer must disclose the evidence in a tactical manner. For the SoS approach the aim is to make the suspect shift counter-interrogation strategy, and for this to happen the interviewer must use the SUE tactics to elicit statement-evidence inconsistencies. The present results provide support for effectiveness of the Reactive variation of the SoS approach. Participants interviewed with the Reactive technique revealed more information overall and also disclosed more new information, compared to those who were questioned without any special evidence presentation tactics (i.e. the Direct condition). Challenging statement-evidence inconsistencies as in the Reactive condition may encourage suspects to change their strategy from a less forthcoming one to a more forthcoming. Indeed, consistent with the intended purpose of shifting suspects’ strategies, one-third (33%) of participants in the Reactive condition reported changing their strategy during the interview – considerably more than the 12% who reported changing strategies in the Direct condition. Participants reported that these shifts in strategy were often a response to the realization that the interviewer knew more than previously thought – exactly in line with the intention of the technique.

The effectiveness of the Reactive technique can be contextualized in several ways. On average, participants in the Reactive condition provided an additional 0.59 of a piece of new information to the interviewer, compared to the Direct condition. This difference appears small, but it is potentially practically meaningful. In the Direct condition, 43% of participants provided no information (receiving a score of 0) related to the third phase of their activities about which the interviewer had no evidence, thereby depriving the interviewer of new information. In contrast, only 26% of participants in the Reactive condition fully denied this part of their activities. In the Direct condition, the modal response was to provide no new information, whereas in the Reactive condition, the modal response was to provide some new information (see ), at minimum saying that were at the location where the crime occurred. Thus, compared to those in the Direct condition, participants subjected to the Reactive technique were more likely to provide potentially incriminating information the interviewer did not previously possess. In legal contexts, the difference between a suspect providing no new information and placing themselves at a crime scene may be enormously practically important.

Although the results were supportive of the SoS approach, not all of our predictions were borne out. Given that previous research has demonstrated that guilty suspects are generally withholding with information and prone to statement-evidence inconsistencies when evidence has not been presented to them (Hartwig et al., Citation2014a; Luke et al., Citation2014a), we had expected the pattern of information disclosure in the Direct condition to be an approximately flat line across the three phases of the interview, disclosing little or no information. Instead, the general pattern in this condition was for participants to disclosure a relatively small amount of information in the first two phases (for which the interviewer asked focused follow-up questions) and even less information in the third phase (for which the interviewer lacked evidence and thus asked only general follow-up questions). Though we did not predict this specific pattern, it is not surprising in retrospect. This pattern may have been due to the focused questioning in the first two phases. That is, these questions may have provided the participants with clues that the interviewer had some prior knowledge about their activities, and therefore it was in their interests to provide some information to appear credible (Brimbal et al., Citation2017; Srivatsav et al., Citation2020). Indeed, previous studies have found similar reductions in information disclosure in phases of an interview in which few focused questions are asked (e.g. Hartwig et al., Citation2018).

In addition to examining the summary and inferential statistics, several noteworthy patterns are apparent in the data visualizations ( and ). Particularly in the first two stages of the interview, the Selective and Reactive conditions have similar means of information disclosure but have clearly different distributions. In the Reactive condition, in the first two phases of the interview, the distributions of information disclosure are bimodal, with the most common values low on the scale and high on the scale (for analyses of the distributions, see https://osf.io/w3ehc/ and https://osf.io/mgwfd/).

Bimodal patterns like this have been observed repeatedly in the literature on suspect interviewing. Luke and colleagues (Citation2014a), Brimbal and Luke (Citationin press), and Srivatsav and colleagues (Citation2021) each bimodal patterns of statement-evidence consistency or information disclosure, under at least some circumstances, when suspects were presented with incriminating evidence. Noting this recurring pattern, Neequaye and Luke (Citation2020) theorized that when suspects perceive the disclosure of a given piece of information to entail both potentially high costs (e.g. disclosure could be very incriminating) and high benefits (e.g. disclosure could strongly bolster their credibility), they will tend to become either extremely withholding or extremely forthcoming, resulting in a bimodal pattern of information disclosure or statement-evidence consistency. In this view, the extremity of suspects’ strategies reflects a commitment to accepting or rejecting the risks of disclosure. Here, it is plausible that the Reactive technique created circumstances in which participants perceived disclosing information to be an effective means of creating a credible impression but that doing so could risk severely incriminating them – hence the bimodality. However, we did not predict this pattern a priori in the present study, and the result ought to be confirmed through replication before arriving at strong conclusions.

Although the general patterns of information disclosure in each condition suggest that the Reactive technique was effective, there was considerable variation in information disclosure across participants. This can be easily seen by the individual trajectories plotted in . This variation should surprise no one and ought to serve as a reminder that no questioning technique is consistently effective with all persons, in all contexts. Although laboratory procedures pale in comparison to the rich complexities of real-world interviews (Kelly et al., Citation2016), even in relatively controlled contexts, interviews are dynamic, complex, and influenced by individual differences.

Suspect perceptions of the interview and interviewer

Unexpectedly, participants in all conditions rated their performance in the interview significantly lower than the midpoint of the self-assessment scale. Participants evidently found the interviews more challenging than we had anticipated, even in the Direct condition in which the interviewer did not comment on the participants’ statements and did not identify inconsistencies with the evidence. Also contrary to what we expected, the Reactive technique seemed to reduce participants’ assessments of how well they performed in the interview and caused them to perceive the interview less positively. Although unexpected, these effects are sensible when one considers that the Reactive technique entails confronting the suspect whenever they make a statement that conflicts with the evidence, whereas the other approaches tested here are more tolerant of such inconsistencies. There is a risk that such confrontations could lead to suspects becoming less engaged and more withholding with information, particularly if they are done judgmentally (e.g. involving an accusation of deception; Alison et al., Citation2013; Surmon-Böhr et al., Citation2020). However, it seems these effects on self-assessment and perceived interaction quality were not sufficient to discourage participants from attempting to create a credible impression by disclosing information about their activities. That is, even though participants who were interviewed with the Reactive version of the SoS approach were aware that their credibility was endangered, they still ‘stayed in the game’ and attempted to create a credible impression, in part by providing information to the interviewer.

We have discussed why the Reactive technique was effective at eliciting information from mock suspects, but it is also reasonable to ask why the Selective technique was less effective (or ineffective). Speculatively, it may have been because it did not provide participants with as much immediate feedback that withholding information was damaging to their credibility. Indeed, the distributions of information disclosure in the Selective condition (see ) conform to what Neequaye and Luke (Citation2020) predict would occur when suspects perceive there is relatively little benefit to disclosing information (or little risk to withholding). The reduction in participants’ assessments of their performance in the Reactive condition could be seen as a problematic outcome, but it is possible that letting the suspect know they have done something to harm their credibility is what makes the technique effective. In other words, the Selective technique may have been too tolerant of statement-evidence inconsistencies to sufficiently prompt shifts of strategy.

Neither of the SoS conditions significantly damaged participants’ impressions of the interviewer, compared to the Direct condition. However, the present data do not provide evidence that the interview techniques were statistically equivalent on this variable. If there are differences, however, it is likely they are relatively small.

Limitations and directions for future research

Methodological limitations

One methodological limitation of the present experiment is its inability to directly address how the SoS approach might affect innocent suspects. We have no specific reason to think that the SoS approach, when implemented as intended, would put innocent suspects at risk (e.g. of falsely confessing), but perhaps some situations may interact with the SoS approach to create problematic circumstances for innocent suspects. Previous laboratory studies on the SUE technique and similar interviewing approaches has demonstrated that innocent participants in mock crime experiments, with few exceptions, are highly forthcoming with information and are highly consistent with the evidence (see, e.g. Luke et al., Citation2014a). Innocent suspects deviate from this pattern only rarely, for example when they have some reason to conceal information (Clemens & Grolig, Citation2019). Because innocent suspects tend to act so predictably in experiments like the one reported here, future research examining innocence-related issues concerning the SoS approach may benefit from specifically investigating situations in which innocent people may deviate from the general trend – for example, by motivating them to conceal information about unrelated criminal activities or to protect other people from suspicion.

Generalizability and practical considerations

In the present experiment, we used three structurally similar mock crime scenarios, each consisting of three parts, and we randomized the order of the parts. These scenarios offer considerably more variation than many experiments using similar methods (e.g. Hartwig et al., Citation2005). Nevertheless, only a negligible amount of variance in participants’ behavior was attributable to the mock crime they committed and the order of the events. Additionally, relatively little variance was attributable to the interviewer conducting the questioning. We cannot firmly conclude that the effectiveness of the SoS approach is invariant across situations and interviewers, but total invariance is rather implausible anyway, given the complexities of intelligence interviewing (see, e.g. Hartwig et al., Citation2014b). However, it is encouraging that we did not observe large amounts of heterogeneity in the effects. High levels of heterogeneity would have suggested that the technique performs substantially differently across situations that differ only in relatively superficial ways.

There are good reasons to think that the observed results are not merely artifacts of laboratory procedures. The SoS approach is based on not only empirical research and psychological theory but also practitioner experience. Specifically, the SoS approach draws in part on the experiences of interviewers attempting to use tactics like the ones we tested here in order to induce shifts in suspects’ strategies, from withholding to more forthcoming (see Granhag & Luke, Citation2018). These practitioners have not, of course, been in a methodologically strong position to evaluate the effectiveness of the tactics. One of the benefits of experimental research like the present study is in its ability to rigorously assess the validity of insights from practice. Other interviewing techniques have been successfully developed in practice before being more rigorously tested under more controlled conditions, such as the tactics of Hanns Scharff (Oleszkiewicz et al., Citation2014). Moving from the field to the laboratory offers the benefit of confidence that the techniques under examination are applicable in the field, since that is the first place in which they were tried.

That said, even if we are confident the SoS approach is usable in the field, the technique is not universally applicable, as it makes several assumptions about the circumstances under which the interview is conducted. First, the suspect must be willing to talk – not necessarily willing to divulge incriminating information, but willing to engage with the interviewer. Second, the suspect must be motivated to convince the interviewer that they are innocent of a given transgression. The SoS approach attempts to capitalize on suspects’ attempts to ‘outsmart’ the interviewer. In situations in which the suspect is spontaneously willing to confess, the SoS approach is not needed. In situations in which the suspect has acknowledged culpability and it is transparent to the suspect that the interviewer is interested in other information (e.g. intelligence about ongoing activities by other actors), the SoS approach may not be applicable. That is, the suspect may not shift to a more forthcoming strategy in order to bolster their credibility, since their credibility is immaterial. Third, the interviewer must possess evidence about at least some of the suspect’s activities. The SoS approach requires the identification of (in)consistencies with established facts. Bluffs and false evidence will not do, and their use is inadvisable for other reasons (Luke et al., Citation2017a; Meissner et al., Citation2014; Perillo & Kassin, Citation2011). Future research will be necessary to better identify the boundaries of the SoS approach’s applicability and to identify the circumstances under which it may be the most useful.

Conclusion

The present experiment builds on previous work on strategic interviewing to offer an initial support for the effectiveness of the Shift-of-Strategy approach. Specifically, we have demonstrated that eliciting statement-evidence consistencies and requesting explanations for them in a non-accusatory manner may be an effective method of influencing suspects to shift from a withholding strategy to a more forthcoming one. There is, as always, room for improvement and for further development, but these results provide promising support to the essential principles of the SoS approach.

Acknowledgements

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Government. For their assistance with data collection, coding, and logistics, we are grateful to Elsa Fanni, Raver Gültekin, Johan Green, Clara Håkansson, Helena Jansson, and Lina Nyström (listed alphabetically by surname). For comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, we would like to thank Kristina Kollback and Charlotte Löfgren.

Supplemental data

Supplemental material is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mfus8/). Parts of data from the project reported here were also analyzed in an unpublished master’s thesis (Håkansson, Citation2020). A preprint of this document is available at https://psyarxiv.com/wncb5/

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alison, L., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., & Christiansen, P. (2013). Why tough tactics fail and rapport gets results: Observing rapport-based interpersonal techniques (ORBIT) to generate useful information from terrorists. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(4), 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034564

- Alison, L., Alison, E., Noone, G., Elntib, S., Waring, S., & Christiansen, P. (2014). Whatever you say, say nothing: Individual differences in counter interrogation tactics amongst a field sample of right wing, AQ inspired and paramilitary terrorists. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.031

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Brimbal, L., Hartwig, M., & Crossman, A. M. (2017). The effect of questions on suspects’ perception of evidence in investigative interviews: What Can We infer from the basic literature? Polygraph, 46(1), 10–39.

- Brimbal, L., & Luke, T. J. (in press). Deconstructing the evidence: The effects of strength and reliability of evidence on suspect behavior and counter-interrogation tactics. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.10.001

- Clemens, F., & Grolig, T. (2019). Innocent of the crime under investigation: Suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies and statement-evidence inconsistency in strategic vs. Non-strategic interviews. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(10), 945–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2019.1597093

- Granhag, P. A., & Hartwig, M. (2014). The Strategic Use of Evidence (SUE) technique: A conceptual overview. In P. A. Granhag, A. Vrij, & B. Vershuere (Eds.), Deception detection: Current challenges and new directions (pp. 231–251). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118510001.ch10.

- Granhag, P. A., Kleinman, S., & Oleszkiewicz, S. (2016). The Scharff technique: On how to effectively elicit intelligence from human sources. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 29(1), 132–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2015.1083341

- Granhag, P. A., & Luke, T. J. (2018). How to interview to elicit concealed information: Introducing the shift-of-strategy (SoS) approach. In P. Rosenfeld (Ed.), Detecting concealed information and deception (pp. 271–295). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812729-2.00012-4.

- Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., Willén, R. M., & Hartwig, M. (2013). Eliciting cues to deception by tactical disclosure of evidence: The first test of the evidence framing matrix. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 18(2), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8333.2012.02047.x

- Håkansson, C. (2020). Do suspects use the counter-interrogation strategies they say they use? Unpublished master’s thesis. Available at https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/63440/1/gupea_2077_63440_1.pdf.

- Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., & Luke, T. J. (2014a). Strategic use of evidence during investigative interviews: The state of the science. In D. C. Raskin, C. R. Honts, & J. C. Kircher (Eds.), Credibility assessment: Scientific research and applications (pp. 1–36). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394433-7.00001-4.

- Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., & Strömwall, L. A. (2007). Guilty and innocent suspects’ strategies during police interrogations. Psychology, Crime & Law, 13(2), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160600750264

- Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Kronkvist, O. (2006). Strategic use of evidence during police interviews: When training to detect deception works. Law and Human Behavior, 30(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9053-9

- Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Vrij, A. (2005). Detecting deception via strategic disclosure of evidence. Law and Human Behavior, 29(4), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-5521-x

- Hartwig, M., Luke, T. J., & Granhag, P. A. (2018). Validating the strategic Use of Evidence technique. Unpublished Report Submitted to the High-Value Interrogation Group.

- Hartwig, M., Meissner, C. A., & Semel, M. D. (2014b). Human intelligence interviewing and interrogation: Assessing the challenges of developing an ethical, evidence-based approach. In R. Bull (Ed.), Investigative interviewing (pp. 209–228). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9642-7_11.

- Kelly, C., Miller, J., & Redlich, A. (2016). The dynamic nature of interrogation. Law and Human Behavior, 40(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000172

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTestPackage: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects ModelsLmertest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

- Lakens, D. (2017). Equivalence tests: A practical primer for t-tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617697177

- Luke, S. G. (2017). Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behavior Research Methods, 49(4), 1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0809-y

- Luke, T. J. (2021). A meta-analytic review of experimental tests of the interrogation technique of Hanns Joachim Scharff. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(2), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/yxpja

- Luke, T. J., Crozier, W. E., & Strange, D. (2017a). Memory errors in police interviews: The bait question as a source of misinformation. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(3), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.01.011

- Luke, T. J., Dawson, E., Hartwig, M., & Granhag, P. A. (2014a). How awareness of possible evidence induces forthcoming counter-interrogation strategies. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(6), 876–882. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3019

- Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Brimbal, L., Chan, G., Jordan, S., Joseph, E., Osborne, J., & Granhag, P. A. (2014b). Interviewing to elicit cues to deception: Improving strategic use of evidence with general-to-specific framing of evidence. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 28(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-012-9113-7

- Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Brimbal, L., & Granhag, P. A. (2017b). Building a case: The role of empirically-based interviewing techniques in case construction. In H. Otgaar, & M. Howe (Eds.), Finding the truth in the courtroom: Dealing with deception, lies and, memories (pp. 187–208). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190612016.003.0009

- Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Joseph, E., Brimbal, L., Chan, G., Dawson, E., Jordan, S., Granhag, P. A., & Donovan, P. (2016a). Training in the Strategic Use of Evidence technique: Improving deception detection accuracy of American law enforcement officersTraining in the Strategic Use of Evidence: Improving deception detection accuracy of American law enforcement officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 31(4), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-015-9187-0

- Luke, T. J., Hartwig, M., Shamash, B., & Granhag, P. A. (2016b). Countermeasures against the Strategic Use of Evidence technique: Effects on suspects’ strategies. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 13(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1448

- May, L., Granhag, P. A., & Tekin, S. (2017). Interviewing suspects in denial: On How different evidence disclosure modes affect the elicitation of New critical information. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01154

- Meissner, C. A., Redlich, A. D., Michael, S. W., Evans, J. R., Camilletti, C. R., Bhatt, S., & Brandon, S. (2014). Accusatorial and information-gathering interrogation methods and their effects on true and false confessions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(4), 459–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9207-6

- Meteyard, L., & Davies, R. A. (2020). Best practice guidance for linear mixed-effects models in psychological science. Journal of Memory and Language, 112, 104092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2020.104092

- Neequaye, D. A., & Luke, T. J. (2020). The disclosure-outcomes management model: Propositions to facilitate research aimed at explaining intelligence interviewees’ disclosure of information. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tfp2c.

- Oleszkiewicz, S., Granhag, P. A., & Cancino Montecinos, S. (2014). The scharff-technique: Eliciting intelligence from human sources. Law and Human Behavior, 38(5), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000085