ABSTRACT

This article explores how marriage animates the racial logic of the security state. While the pursuit of romantic love culminating in a wedding is considered to be a universal good, arranged marriages are viewed as a dangerous anachronism which threaten the state’s authority. By revealing the animating force of arranged marriage in the UK immigration regime and the War on Terror, we can see the central role of love marriage within the principles of choice, autonomy and individuality around which the liberal subject organises their moral economy. The legalisation of gay marriage – constructed as a kind of love marriagepar excellence – becomes the means through which the nation state can uphold this moral economy and be renewed and reinvigorated in the process. By putting gay marriage in dialogue with arranged marriage, the gendered and racial configuration of the UK as a security state becomes visible.

I don’t support gay marriage despite being a Conservative.

I support gay marriage because I’m a Conservative.

(Cameron Citation2011)

all roads lead to the bazaar

(Said Citation1993)

Introduction

In January 2019, the news broke that women ‘rescued’ by the UK government’s Forced Marriage Unit (a joint Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Home Office initiative) were being made to pay for the costs of their protection. If they were unable to pay outright, they had to agree to sign up to a loan, usually in the region of seven hundred pounds, to cover the costs of food, flights, and accommodation. Their passports were confiscated and held until the loan had been repaid in full (Guardian, 2 January 2019). Though there is much to be said regarding the implications of this policy in relation to the government’s vocal concern about coercive cultural practices, the matter of the passport seized as collateral for an involuntary debt requires particular attention. In ‘saving’ women from being taken from the UK against their will, the state then ensures that they are unable to leave the UK. The Forced Marriage Unit thus ‘liberates’ women from situations in which passports are routinely seized as a means of control (such as by family members attempting to prevent women from fleeing a forced marriage) by enlisting precisely the same mechanism of immobilisation. Further, while forced marriage tends to be viewed as an adherence to (anachronistic) cultural norms, it is also critiqued for its underlying economic or practical motivations, with marriage to a UK national aiding in access to residency and citizenship. As such, forcing women into debt in order to avoid an unwanted marriage appears to collude with rather than contest the notion that a woman’s value is primarily financial and that, whether being forced into marriage or ‘rescued’ by the state, she must earn her keep.

This policy illuminates the way that marriage sits at a key intersection of the crosscutting discourses of ‘love’, ‘value’ and ‘control’, bringing together powerful ideas about choice, autonomy and kinship in the liberal imaginary. In this article I ask, which expressions of love are sanctioned by the state? What kinds of kinship can be recognised at the border? Which relationships can be chosen freely, and which are antithetical to a liberal notion of freedom? In attempting to give historicised answers to these questions, I situate my analysis of marriage in the continuities between colonial governance and the UK immigration regime. As Nadine El-Enany suggests, Britain’s borders are the mechanism through which the plundered wealth of the British Empire is hoarded (Citation2020). It is with this understanding of the contemporary world as shaped by colonisation that I situate the War on Terror. I treat the War on Terror as a global geopolitical, technological, military, and cultural network, with each vector working together to secure new forms of empire. The War on Terror interacts and intersects with the UK border regime, both discursively and at the level of policy, for example, in the use of a discretionary, terrorism-related clause in the Home Office’s internal guidance to deny residency or citizenship. The War on Terror and the UK immigration regime form an increasingly militarised security state, which both relies on migrant labour and asserts a virulent nativist racism that makes obtaining legal passage, safety, and access to resources difficult if not deadly. While theorists, such as Nisha Kapoor (Citation2018), analyse the dynamics of racism and the security state through counterterrorism policing and border control’s use of expulsion and incarceration, this article focuses on the way in which marriage, a seemingly benign institution, animates the racial logic of the security state.

The security state is a particular iteration of the modern racial state, which, as David Theo Goldberg (Citation2002, 7) notes, ‘is racially conceived and expressed through its gendered configurations, and it assumes gendered definition and specificity through its racial fashioning’. In this article, I develop Goldberg’s understanding of race, not as a vector of identity, but as the logic that underpins and justifies surveillance, incarceration, militarisation, and other methods of exclusion and control. The gendered configuration of the modern racial state becomes highly visible in the UK’s immigration regime in which women migrants have been subjected to particular forms of sexualised violence (such as virginity tests, which I will discuss in more detail), while also having access to some minor legal protections (for example, the legislative protection for victims of ‘sex trafficking.)’Footnote1 In order to understand the security state’s deployment of sexuality, it must be considered not as a matter of personal desire, but of biopolitics, as a domain of life that is at the heart of state control and population management. State control over sexual life is, of course, largely obscured, and sexuality is conceived of as deeply personal and as ontologically primary. As Gargi Bhattacharrya (Citation2008, 14) notes, ‘we live in a culture that imagines fulfilment in terms of intimacy and sexual autonomy and views sexual expression as one of the purest expressions of self – what we really really want’. As such, though marriage is a relationship with and through the state, it is narrated as the natural outcome of, and container for, individual sexual and romantic desire. Taking the approach of deconstruction, I attempt to denaturalise marriage through an examination of its function in the UK as a security state.

This contemporary discourse on arranged marriage can be traced back to Orientalism, in which ‘the discourses of cultural and sexual difference are powerfully mapped onto each other’ (Yeğenoğlu Citation1998, 10). According to Sonya Fernandez:

The universal goods of liberal democracy (freedom, equality, rights, liberties and tolerance) are hailed by the West in the fight for moral supremacy against the evils of Islam (barbarism, savagery, oppression and subordination). These polarized constructions are then mapped on to gender-based issues such as veiling, honour killings and forced marriages to evidence the West’s promise of liberation and Islam’s all-conquering brutality (Citation2009, 271)

I would suggest, however, that these constructions aren’t mapped onto gender-based issues so much as intertwined with them from the outset. In this approach, I follow Meyda Yeğenoğlu who shows that many theories of Orientalism erroneously treat sexuality and gender as subdomains of the cultural or the institutional, rather than as constitutive of these domains. Subsequent work has tried to address this relegation of the sexual by taking up Said’s references to the latent aspects of Orientalism in fantasy, desire, and the unconscious. Though this is too wide and varied a field to summarise here, two key themes are particularly germane to my argument. Firstly, the Western subject’s fascination with veiling has proven to be potent and relentless. Frantz Fanon (Citation1970) notes the political doctrine forged by French colonial forces in Algeria, who saw unveiling as essential to domination and control. More recently, Lila Abu-Lughod (Citation2002) theorises the veil’s function as the visible sign of women’s oppression under the Taliban, which was mobilised to justify the invasion of Afghanistan. The structure of the discourse on veiling acts as a model for that on arranged marriage: both are assumed to be oppressive and misogynistic practices that women cannot choose, regardless of the claims many women make to opting for these practices. Further, they are both understood through reference, implicit or explicit, to an assumed opposite: veiling is counterpoised by Western dress; arranged marriage is compared to love marriage. As Abu-Lughod notes that women in the West also make sartorial decisions within socially constrained limits (786): by tracing this continuity, a deterministic and essentialist obsession with veiling is displaced. I use a similar method, revealing the continuities between arranged and love marriages as a means to disrupt the security state’s deployment of marriage as a metric of civilisation.

The second theme from postcolonial studies that is useful for my purposes is the relationship between Islam and homosexuality. Well-known Orientalists Richard Burton and T. E. Lawrence both document, with considerable enthusiasm, the apparently widespread sodomy and male prostitution in the Middle East and North Africa (Boone Citation1995). Though this enthusiasm contoured their view of imperialism, they remained highly invested in the colonial project. In this way they act as paradigmatic Orientalist scholars whose knowledge (however tenuous or fantastical) of the Other’s cultural and sexual difference is deployed in structures of domination and control. The close associations between Orientalist scholarship and empire building continue in contemporary geopolitics. As Said (Citation(1978) 2003)) confirms, ‘The major influences on George W. Bush’s Pentagon and National Security Council were men such as Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami, experts on the Arab and Islamic world who helped the American hawks think about such preposterous phenomena as the Arab mind and centuries-old Islamic decline that only American power could reverse’. Bhattacharrya, Jasbir Puar (Citation2008) and others note, the associations between the ‘Orient’ and sodomy have been complicated (though not displaced) by ‘homonationalism’, which trades on the view that Muslims are uniquely and violently homophobic, while the West is the natural defender of gay rights.

Queer theorists have explored the ways in which Western representations of Islam, the Middle East, and homosexuality are deployed in service of securitisation, military force, and the expansion of American empire. Judith Butler (Citation2008) argues, for example, that the liberal media portrayed the sexualised torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib through the lens of culture, by proposing that ‘these orchestrated scenes of sexual and physical humiliation exploit the specific sexual vulnerabilities of these populations’. Butler neatly reverses this formulation, to suggest that

If we want to speak about “specific cultures”, then it would make sense to begin with the specific culture of the US army, its emphatic masculinism and homophobia, and ask why it must, for its own purposes, cast the predominantly Islamic population against which it wages war as the site of primitive taboo and shame. (16)

Butler’s analysis works along the grain of deconstruction, which Yeğenoğlu describes as ‘mak[ing] the subject recognise the other in himself or herself’ (9), an approach I deploy in this article. Deconstruction yields the insight that the Orientalist imaginary constructs the Muslim Other by ascribing to him a repressed homosexuality. This ascription disavows the same quality in the Western subject, and becomes a justification for the sexualised violence of military intervention and occupation, as well as the War on Terror’s more insidious forms of violence. A similar logic informs the operations of the UK border regime’s culture of hostility, suspicion and disbelief within which LGBT asylum claims are assessed. As Mariska Jung (Citation2015) notes, immigration courts become an arbiter of legible and mobile LGBT subjectivities, only granting asylum to certain LGBT subjects and deporting others, while maintaining the claim that the UK protects gay rights.

Building on this body of work, I turn my attention to marriage. I begin by historicising the relatively recent emergence of marriage based on romantic love, trying to account for its significance in relation to ideas of choice, rationality, and sovereignty. I contrast this with the submerged but crucial presence of arranged marriage in the cultural imaginary, on which the UK immigration system constructs legislation designed to bar entry to South Asian migrants in particular. I suggest that forced and sham marriages operate as interchangeable signifiers, differentially deployed to interpolate different audiences. The two, however, work together to secure the relevance of the state at a time in which there are, as Jyoti Puri (Citation2016, 5) notes, ‘widespread perceptions […] of the scaling back of the state due to the effects of neoliberalism’. I then turn to gay marriage as a means through which love marriage and its role in the security state is renewed and consolidated. Finally, I consider why forms of sexuality outside of domestic, monogamous love marriage are so threatening to the Western liberal imaginary and its deep psychic investment in choice, autonomy and individuality.

Love marriage

In contemporary liberal common sense, marriage purports to be an expression of love, commitment, and romance (for the purposes of obtaining or fortifying stability and family) and as a way to organise property, illness, and death.Footnote2 Love marriage is defined by its consolidation of the nuclear (rather than extended) family. This consolidation is enabled by a focus on companionship and monogamy, as well as on the freedom to choose to whom and when one marries. In order to go beyond the naturalisation of love marriage, we must consider the function of marriage rather than what motivates individuals to marry. Love marriage is a relatively recent development: ‘only in the seventeenth century did a series of political, economic, and cultural changes in Europe begin to erode the older functions of marriage, encouraging individual to choose their mates on the basis of personal affection and allowing couples to challenge the right of outsiders to intrude upon their lives’ (Coontz Citation2005, 7). George Mosse (Citation1985, 18) confirms that the ‘intimate modern family’ develops in the eighteenth century as a result of industrialisation and the changing division of labour it produced. As Europe urbanised, production and domestic life became separated for the majority, and the nuclear family became dominant. The political, economic, and cultural changes in Europe are, of course, fundamentally tied to colonial expansion, which provided the raw materials for industrialisation, as well as the need and the discursive material for the new ideologies of race, gender and nation through which love marriage is legitimised. By the eighteenth century, marriage in the popular imagination had been transformed from arranged unions to partnerships based on love and affection. This transformation of marriage chimed with the emerging view of human sexuality as an organising principle.

In Foucault Citation1979, 22) description, sex ‘became a causal principle, an omnipresent meaning, a secret to be discovered everywhere’. Theorists of colonial discourse note that the Enlightenment began to view sex through the prism of ‘the economy of nature’. This notion could be instrumentalised for political ends. Anne McClintock (Citation1995, 39) observes:

[t]he doctrine of sexual complementarity, which taught that men and women are not physical and moral equals but complementary opposites, functioned as an important supplement to nascent liberalism, making inequalities seem natural while satisfying the needs of European society for a continued sexual division of labour.

Examples from the natural world, for example plant reproduction, were harnessed as an example of this complementarity in nature, giving further weight to the call for gendered inequality as a moral good, based in natural law. The Enlightenment focus on rational, free subjects, however, placed a new emphasis on individual desire and agency. In the eighteenth century, the rise of ‘affective individualism’ reimagined the marriage relationship as one of choice, rather than economic or social necessity. George Mosse traces how this idea of complementarity, once established as a principle in nature, was harnessed by nationalist projects eager to anchor their emergent biopolitical regimes to a moral logic. Nationalism continues to deploy the idea of gender complementarity, as Mehammed Amadeus Mack (Citation2017, 102) notes in his writing on ‘the French soft commerce of sexual complementarity’. Crucially, nature was enlisted to justify gender roles as inevitable and complementary, while also asserting that marital partners should be freely chosen. By harnessing choice to nature and nature to the nation, love marriage became a symbol of European civilisation.

Choice is heavily freighted with moral and political significance, as the central inheritance from the Enlightenment project that lies at the heart of the Western subject. In my use of ‘the Western subject’, I follow Yeğenoğlu’s assertion that ‘Despite the difficulties in attributing unity to this subject (as the differentiations are great and there are contradictory, discordant, and disharmonious positions), it is nevertheless not easy to claim that there is no validity or justified ground in the usage of the term’ (3). In the assumed natural or universal quality of love marriage we can see the way in which choice organises the moral economy of the Western subject, and the imagined geographies within which he locates himself and his Others. In the next section, I posit a reading of arranged marriages as a means to deconstruct love marriage, showing the ways in which it is present within its Others. In revealing the presence of a disavowed patriarchy and economic pragmatism within an institution that purports to be defined by individual desire and nucleated intimacy, the role of the state in the marriage relation becomes apparent. As my discussion of forced and sham marriages will show, as the state becomes increasingly securitised, its mediation of marriage is explicit, violent, and highly racialised.

Arranged marriage

Having established, albeit briefly, ‘how love conquered marriage’ (to use Coontz’ memorable phrase), I turn to arranged marriage, perhaps a more widespread practice, and with a much longer lineage. Its persistence and reach, incidentally, are not to recommend the practice but to situate it historically and geographically. Marriage, as a means of arranging family structures for economic purposes, has played a key part in almost all kinship systems. Claude Levi-Strauss surveys the anthropological literature and concludes (as summarised by Gayle Rubin (Citation1975, 173)) that ‘marriages are a most basic form of gift exchange, in which it is women who are the most precious of gifts’. We must, therefore, be attentive to these features in contemporary love marriage. I echo Sherene Razack’s (Citation2004, 165) assertion that ‘both arranged and forced marriages spring from an impulse to control women’s sexuality […] the patriarchal features of the practice cannot be denied’. Yet considering the ways that these patriarchal features can be located in love marriage too, rather than acting to justify them, facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of marriage as a whole.

Until relatively recently, the upper classes in Europe used arranged marriage as a way to secure and consolidate geopolitical power. In her close reading of ‘Human Visas: A Report from the Front Lines of Europe’s Integration Crisis’, Razack notes that ‘Europe’s own history of arranged marriages for its wealthier classes is acknowledged but used to indicate that whereas Europe has freed itself from its own feudal past, Muslim societies have not’ (137). Asserting a progressive teleology is a common approach to the shared custom of arranged marriage, yet its significance can be read in a myriad of ways. One could use the recent history of arranged marriage in Europe to affirm similarity or continuity between different kinship systems rather than difference or divergence. Further, in pursuing a deconstruction of love marriage, I note the ways in which love marriage is also used to consolidate power. Give that so many love marriages occur between people of almost identical social class, race, religion, and educational background, one could conclude that the consolidation of power remains a salient, if hidden, feature.

In showing these continuities, I follow the approach of ‘displacement’; rather than taking love marriage and arranged marriage as opposites and ‘flipping the binary’ by advocating for arranged marriage, I aim instead to show the ways that the patriarchal features that are assumed to inhere in arranged marriage are, in fact, constitutive of marriage as a modern institution. I posit that the disavowal of the recent history of European arranged marriage is an example of Orientalism’s practice of seeing the Other as a poor copy of a Western original. Said (62) notes:

It is as if, having once settled on the Orient as a locale suitable for incarnating the infinite in a finite shape, Europe could not stop the practice; the Orient and the Oriental, Arab, Islamic, Indian, Chinese, or whatever, become repetitious pseudo incarnations of some great original (Christ, Europe, the West) they were supposed to have been imitating.

Love marriage becomes, despite the inverted timeline, an original for which arranged marriage acts as a ‘repetitious pseudo incarnation’.

Arranged marriage has proven both troubling and productive for the UK’s immigration regime. It is the site of a paranoiac racism, in which the aim of securing the border is expressed as a defensive response to the ‘pathology’ of Asian family structures and, more recently, as a concern for Asian women’s safety. Questions of Asian marriage practices first emerged through the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which restricted the rights of Asian men to temporary leave the country and re-enter at a later date. As Rachel Hall (Citation2002) notes, ‘rather than jeopardize their chance of working in the UK many South Asian men decided to call their wives over’. Further, the government viewed family unification as a means of safeguarding against Asian men entering relationships with white women. Conservative MP Sir John Smyth stated (as quoted in Smith and Marmo Citation2011, 152), ‘If we do not allow families to come into the country as units we shall have all sorts of trouble with women. The female element is absolutely essential, and the sooner the men here have their wives with them the better I shall be pleased’. Therefore, as Hall notes, Asian women arrived as dependents on men: they were viewed as wives rather than as workers. As their immigration status was dependent on their marital status, it was as wives that their legitimacy was assessed. One of the most explicit and violent forms of assessment, in which the state’s paranoid sexual imaginary becomes visible, was ‘virginity testing’. In British High Commissions across South Asia, as well as at the UK border, women coming to join their fiancés were subjected to invasive physical examinations to ‘check’ that they were virgins and, therefore ‘legitimate’ fiancés.

The discourse regarding trans-continental arranged marriage is riddled with contradiction. As Parita Trivedi (Citation1984, 46) notes, ‘The ban on male fiancés was presented as a benign act by the govern to “protect” young Asian women from the “horrors” of the arranged marriage system’. Yet, simultaneously, the government suggested that British Asian women marrying men from the subcontinent ought to emigrate to join their husbands. Pratibha Parmar (Citation1992, 245) quotes the 1978 parliamentary Select Committee report: ‘we believe that the members of those minorities should themselves pay greater regard to the mores of their country of adoption and indeed, also to their traditional pattern of the bride joining the husband’s family’.Footnote3 These contradictory statements – that the British state are protecting young British Asian women from a harmful traditional practice; that British Asian women should more scrupulously follow tradition and join their husbands on the subcontinent – is circumscribed by an implicit third option, that British Asians could assimilate into Western marriage norms. As Chris Waters notes, it was hoped that ‘well-adjusted’ migrants would adopt a ‘Western model of the egalitarian family and companionate marriage’ (in Smith and Marmo 152), therefore committing to the values of choice, autonomy and individuality that organise the Western liberal imaginary. These successive pieces of immigration legislation from the 1960s marked a continuation of biopolitical colonial governance strategies, which sought to manage populations through control of kinship, sexual life, and family structures. As the example with which I began this article suggests, these state interventions have continued to evolve in the 21st century, inflected by a conviction that issues of national security are fundamentally intertwined with cultural and sexual practices. In the next section, I turn to the slippages between the idea of forced and sham marriages, and the way in which the tropes of violence, deceit and deviance circulate as threats to national and individual sovereignty.

Forced/Sham marriages

Given the hegemony of love marriage and the structuring force of romantic love in the collective imaginary, one can see why arranged marriage is viewed as a threat. One of the most visible iterations of this threat is the moral panic across Europe about ‘forced marriage’. In the UK, great pains are taken to invoke the distinction between forced and arranged marriages, for example on an educational BBC-run website, which states, ‘Forced marriages occur when either or both participants have been pressured into entering matrimony, without giving their free consent. It’s not the same as an arranged marriage, which may have been set up by a relative or friend, but has been willingly agreed to by the couple’. As Bhattacharrya observes, the racial discourse of the security state finesses older ideas: ‘This is a racialisation that builds on the insights of anti-racist critiques and the lessons of postcolonial theory [… it] knows to avoid generalisation, anachronism and mythologisation’ (91). Furthermore, in the tautology of ‘free consent’, it’s clear that the distinction between ‘arranged’ and ‘forced’ marriages relies upon the liberal investment in the rational, autonomous subject, the subject of and with choice. As Amrit Wilson notes, in this focus on choice, we can see the postcolonial panic around arranged marriage as an echo of the colonial obsession with sati [widow immolation] (Citation2006, 89) – or, I would argue, with veiling. Yet, arguably, the entire discourse of romantic love – a love conceived of as having a teleological and inherent relationship to marriage – could itself be seen as coercive, as feminist theorists regularly insist.Footnote4

In 2000, a government White Paper, ‘Secure Borders, Safe Haven’, set out its concerns with what it euphemistically referred to as ‘the overseas element’ of forced marriage. As noted, the government is essentially concerned with the marriages of British Asian women with men from South Asia who, by virtue of the marriage, are able to legally enter the UK. As Ratna Kapur (Citation2004, 156) puts it: ‘The White Paper thus subjects arranged marriages to a double illegitimacy. Either the marriage is not genuine because it is used for immigration purposes and is a sham; or it is a real marriage but then the whole practice of arranged marriage is rendered suspect’. This double illegitimacy parallels the logic that pervades the sexualised racism of the War on Terror, which Bhattacharyya notes draws on a view of the ‘East’ as highly sexualised and, therefore, in need of more ‘substantial constraints’ than in the West. As such, non-Western sexual practices are viewed as either dangerously untamed or excessively controlled. The Forced Marriage Unit, which now has global networks that span across South Asia and beyond, was launched in 2005 by a debate in the House of Commons led by Ann Cryer, MP for Bradford. In her speech, she addressed ‘the leaders of the Asian Muslim community’ to ‘encourage their people to put their daughters’ happiness, welfare and human rights first. If they do, their communities will progress and prosper, in line with the Sikh and Hindu communities’. As Wilson observes, Cryer here suggests not only that forced marriages were the preserve of Muslims, but that they were unhappy and poor as a result (87). The focus on Muslims is exemplary of the interface between the War on Terror and the immigration regime. The fact that forced marriage occurs across the three major religious groups she mentions is ignored, and the colonial tactic of ‘divide and rule’ is shamelessly deployed, expressed in the language of multicultural meritocracy.

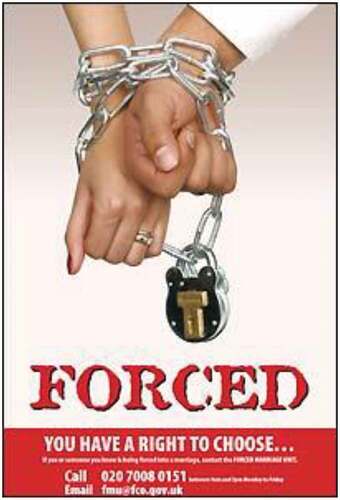

The various government initiatives regarding forced marriage are indivisible from attempts to prevent ‘sham marriages’, i.e, marriages undertaken for the sole purpose of obtaining a visa. A Forced Marriage Unit-produced poster () was displayed in registry offices where civil marriages are conducted, and which have increasingly been targeted by immigration enforcement. The notion of a ‘sham marriage’ is, itself, one that derives meaning from the naturalisation of ‘love marriage’; if one sees marriage as a contractual arrangement, then the notion of a ‘sham’ becomes obsolete. While the idea of a sham marriage implies a wily and cunning interloper, conspiring to evade immigration control, the moral panic takes the guise of concern for Asian women. The two, however, work together to secure the relevance of the state (as defender of national borders and protector of vulnerable women) as its welfarist function is being dismantled by neoliberalism and, more recently, austerity.

Highly mediatised raids on civil weddings by immigration enforcement began in 2013 as part of a Home Office policy to increase media coverage of immigration enforcement, arguably to demonstrate the continued might and capacity of the state. The most widely shared and controversial posts showed weddings being interrupted, rather than raids on commercial premises. As of 2015, all proposed marriages and civil partnerships in the UK involving a non-EEA national with limited or no immigration status in the UK are referred to the Secretary of State by the marriage registration officials. The Home Office then decide whether or not to investigate. As such, there is an element of racial differentiation built into the legislation itself (the proposed unions of EEA nationals are not subject to investigation), as well as space for the Home Office to exercise discretion according to both political demands (for example, to limit migration from the Global South) and personal prejudice. As such, while a marriage between a UK citizen and, for example, an Australian national could be interrupted or investigated, there are few media accounts of this happening.

It is within the context of the border as a spectacle that the forced marriage poster () displayed in registry offices must be understood. In the image, which shows two hands chained together, one can see a fantasy of the Other and their profane and coercive kinship structures. Implicit in the text (which states ‘Forced: You Have A Right to Choose’) is the assumed bondage of the extended family, as well as of forced marriage. Yet, in this image, we can also see some of the tropes of love marriage; the idea of being tied together is present in the language of ‘’til death do us part’, and wedding rings are symbols of ownership and possession, as well as love and eternity. In Spanish the term for wife is esposa and handcuffs is esposas; in English, one sometimes hears a man refer to his wife as a ‘ball and chain’. Moreover, the domesticated couple and nuclear family tend to perpetuate the feminisation of reproductive labour, regardless of the form of the marriage.Footnote5 These similarities – the blurriness of coercion and consent, the reproduction of social class and the family, the central role of state legitimation – are obscured by the racialising logic that subtends the discourse on marriage. In the next section, I consider the complex and revealing role of gay marriage as a means of understanding the security state’s investment in maintaining marriage norms organised around the ideas of love and choice.

Gay marriage

As Coontz observes, marriage is always assumed to be in crisis: ‘This history of love-based marriage […] is one of successive crises, as people surged past the barriers that prevented them from achieving marital fulfilment and then pulled back, or were pushed back, when the institution of marriage seemed to be in jeopardy’ (5). Gay marriage has been the latest attempt to roll back this crisis: it is used to regenerate marriage, perhaps akin to the role that gay communities have often played in gentrification, though a lengthier discussion of this dynamic is beyond the remit of this article.Footnote6 Gay marriage emerges as an aim for a global gay rights movement, albeit one increasingly led by the US, in the 1990s. By the 2000s, a movement focussed on love rather than sex became hegemonic. A global Amnesty International campaign, for example, was organised around the slogan ‘love is a human right’ As Rahul Rao (Citation2014, 170) notes, ‘marriage (a ‘love right’) curtails the very liberty that is the object of ‘prior’ struggles for ‘sex rights’. As such, the rights of prisoners to access condoms, for example, is rarely considered an essential demand by LGBT campaigners, while wedding services refusing to cater to gay weddings is the subject of considerable attention. This discrepancy confirms Michael Warner’s observation that ‘as long as people marry, the state will regulate the sexual lives of those who do not. (Warner Citation1999, 127)

Gay marriage became legal in the UK (excluding Northern Ireland) in July 2013. I use the vernacular phrase ‘gay marriage’ rather than the more neutral ‘same-sex marriage’ or the campaign rhetoric ‘equal marriage’ to gesture towards an under-theorised but significant dimension of the development. I posit that the ‘inclusion’ of homosexuals into the institution of marriage performed, on some levels, the precise function that many of those against gay marriage feared: changing the institution of marriage. Though marriage was not transformed at its root, it had the aforementioned regenerating effect. Straight people are delaying or eschewing marriage (heterosexual marriage rates reached a historic low in 2018 (Independent, 28 February 2018)) and divorce rates continue to rise, but marriage remains the cornerstones of the ‘family values’ agenda that permeates public discourse. As Warner notes,

Marrying makes your desire private and locates its object in an already formed partnership. Where coming out implies impropriety, because it breaks the rules of what goes without saying, marrying embraces propriety, promising not to say too much. Where coming out triggers an asymmetrical dialectic, since straight people cannot come out in any meaningful way as long as the world presumes their heterosexuality, marrying affirms the same repertoire of acts and identities for straights and gays and thus supplies a kind of reassurance underneath the agitational theater of the ceremony. (148)

As such, gay marriage reinvests marriage with meaning, renewing the sense in which it functions as a relevant and supported choice. The arguments for gay marriage often highlighted marriage as an expression of love, desire and commitment, though the campaign for gay marriage also noted the more pragmatic elements, namely, marriage as an economic institution that allows for the transfer of wealth. Further, the image of gay couples engaging in the same rituals – the same ‘repertoire of acts and identities’ – displaces the longstanding view of gay life (especially for men) as defined by indiscriminate casual sex.

The fight for gay marriage has come under attack from queer theorists such as Warner, Puar, and Butler, who note that the homonormative couple is one that can be incorporated into the national mythology and deployed as a metric of civilisation. In other words, gay marriage helps to reassert the relevance of the nation-state, allowing it to present itself as the protector of sexual freedoms. As sexual freedom is treated as the paradigmatic form of freedom, marriage rights for sexual minorities are drawn into the discourse of the War on Terror, which is framed as battle between freedom and constraint. Under the UK’s Conservative-led Coalition Government, gay rights were explicitly linked to an imperialist agenda. In 2011, Cameron pledged to cut aid to African nations where homosexuality remained illegal, regardless of the fact that these laws have their origins in British colonial legislation. As Rao notes, this announcement sparked hostile responses from political leaders in Tanzania, Ghana and Uganda, as well as from African LGBTI activists who warned that ‘gay conditionality’ could put them at risk of further scapegoating and violence. Cameron rearticulated this logic in a new, upbeat tone a couple of years later: in an attempt to make further political capital out gay marriage, he suggested it could be an export good. He said, ‘Many other countries are going to want to copy this. And, as you know, I talk about the global race, about how we’ve got to export more and sell more so I’m going to export the bill team. I think they can be part of this global race and take it around the world’ (Telegraph, 24 July 2013). By articulating gay imperialism in the language of neoliberal capitalism – in terms of ‘the global race’, the imperative to ‘export more and sell more’ – Cameron is able to cleave together international markets and gay marriage, with Britain as a leading player across the cultural, political, social and economic spheres.

Further, the meteoric ascendancy of gay rights in the West, as the AIDS crisis abated and marriage became the central goal, allows us to examine why other kinds of kinship arrangements perturb the state’s power structure. As Kapur notes, ‘when the law starts regulating emotional and intimate aspects of people’s lives, it exposes its preference for certain normative arrangements and its impetus to universalise and naturalise those arrangements’ (154). Gay marriage has allowed for a new conception of gay life, marked by access to state recognition. Gay marriage, therefore, allows for a disavowal of gay casual sex, which has long been the site of a profound ambivalence, particularly within the Orientalist discourse that acts as a key genealogical thread in conceptions of sexuality in Britain. While gay sex was criminalised in the UK – and sodomy laws were introduced across the British Empire – there remained a concurrent history of seeing the ‘East’ as the site of homosexual possibility.

As indicated, actors such as Burton and Lawrence who were at the heart of the colonial project propagated the myth of ‘Oriental’ homosexuality. This myth persisted into the postcolonial period: as Boone notes, ‘The number of gay and bisexual male writers and artists [such as E.M. Former, Andre Gide and Paul Bowles] who have travelled through North Africa in pursuit of sexual gratification is legion as well as legend’ (90). Boone observes that the ease of access to male sex workers in North Africa is central to their ‘fantasies of a decadent and lawless East’. Further, ‘A corollary of the occidental tourist’s fantasy that all boys are available for the right price is the assumption that they represent interchangeable versions of the same commodity: (nearly) underage sex’. (102). This fungibility is both desired and feared; Western writers and artists go to the Middle East and North Africa to access multiple, seemingly interchangeable partners, yet fear that this cornucopia of casual sex will prevent them from maintaining their creative capacities. Boone suggests that ‘for both Flaubert and Durrell the fantasized projection of sexual otherness onto Egypt eventually occasions a crisis of writing, of narrative authority, when the writing subject is confronted by (imagined) sensual excess’ (95). Extending this analysis, I suggest that this fear of creative impotence stands in for an anxiety about the sanctity of the individual. As artistic or literary production is understood to be a paradigmatic form of individual expression, its loss signals a loss of individuality itself. I posit that this fear of sexual fungibility, commodification, and loss of individuality is precisely what animates the debates around arranged marriage. While love marriage relies on the idea of individuality, in arranged marriage, like in casual sex, the individual as an individual is of secondary concern. In both cases, the individual is not ‘the one’ but one among many possible options; further, in arranged marriages as in casual sex, love is a possible outcome, rather than a precondition. The state’s defence of love marriage, then, is implicitly a defence of the individual.

Conclusion

If we revisit arranged marriage in light of the emergence of gay marriage as a consolidation of the nation-state’s regulation of sexuality, some new insights emerge. The discourse of romantic love posits that there is a universal moral framework in which the choice of a romantic and sexual partner is an essential aspect of human freedom. The nation-state claims to act as a guarantor of that freedom through the institution of marriage, which is, primarily, a relationship with the state. In extending marriage to same-sex couples, it bolsters its legitimacy through its association with gay life, which has come to represent sexual freedom and heightened individualism, unencumbered by the historical weight of heterosexual marriage. The extension of the institution of marriage to gay subjects develops the logic established by decades of UK state interventions into Asian marriage practices, in which arranged marriage is reified both as a fixed cultural norm that must be respected, and as a backward and misogynistic practice from which British Asian women need to be rescued. While the state’s paternal tone is reserved for ‘forced’ marriages, this masks its attempts to prevent ‘sham’ marriages; that is, marriages entered into for the sole purpose of obtaining a visa. Yet this notion of a sham is difficult to maintain unless you implicitly concur with ‘love’ as the primary and essential quality needed in order to marry. Under a different conception of marriage – which could assume that commitment acts as a precursor to love, rather than stemming from it, or which could view marriage as a contractual arrangement rather than an affective one – the idea of a ‘sham’ cannot hold. As the industry surrounding gay marriage extends, and its presence in the global imaginary is consolidated, the UK state’s interventions into sexual life, kinship structures, and domestic arrangements are ramped up in the name of security.

By contrasting the UK government’s interventions into Asian marriage practices as a tool of immigration control with their recent embrace of gay marriage, we can see how the modern racial state, in its most recent iteration as a security state ‘assumes gendered definition and specificity through its racial fashioning’. The comparison makes visible the ways in which marriage, as part of a larger arsenal of biopolitical tools, connects the management of the population with the individual’s management of their own life. Love marriage is constructed as an inherent and natural part of the latter, which obscures its role in the state management of population. As marriages entered into for reasons other than romantic love are seen as deviant or deficient, the state’s cynical use of arranged marriage as a tool of immigration control is viewed as the legitimate defence of love marriage as well as of national borders. By tying individual self-realisation to national sovereignty, the state renews itself as the natural arbiter of the self as well as the nation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For a contestation of the discourse on ‘sex trafficking’, see Julia Davidson’s Modern Slavery (Citation2015).

2. The most significant domain of research into the function of marriage comes from anthropology and the feminist critiques thereof. Gayle Rubin notes Lévi-Strauss’ The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) as a key text; it is ‘the boldest twentieth-century version of the nineteenth-century project to understand human marriage’ (170). It draws on nineteenth-century texts, such as Ancient Society, by Lewis Henry Morgan (Citation1877), which inspired Friedrich Engels to write The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884). As ever, anthropological work has focussed on the practices of the Other and tried to account for the purpose of marriage elsewhere.

3. One should note that this is not universally recognised as ‘tradition’.

4. Feminist critiques of romantic love are diverse. Radical feminists such as Firestone noted that ‘love is the pivot of women’s oppression today’ (Citation2018) and sought to develop alternative modes of kinship. More recently, autonomous feminists Clémence x Clémentine compare the coercive control of the couple form to that of the state (Citation2017). Many of these critiques have a limited critique of borders, citizenship, and the racial dimensions of biopolitical life, though black and postcolonial feminist writing (Carby (Citation1982), Spillers (Citation1987), McClintock (Citation1995)) seeks to denaturalise and historicise the nuclear family.

5. A 2016 study by the Office of National Statistics showed that women carry out an overall average of 60% more unpaid reproductive work than men.

6. For an overview of the relationship between urbanisation and gay identity, see Christine Hanhardt (Citation2013) and Jin Haritaworn (Citation2015).

References

- Abu-Lughod, L. 2002. “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections On Cultural Relativism And Its Others.” American Anthropologist 104 (3): 783–790. doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.783.

- Bhattacharyya, G. 2008. Dangerous Brown Men. London: Zed.

- Boone, J. A. 1995. “Vacation Cruises; Or, The Homoerotics Of Orientalism.” Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 110 (1): 89. doi:10.2307/463197.

- Butler, J. 2008. “Sexual Politics, Torture, And Secular Time.” The British Journal Of Sociology 59 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00176.x.

- Cameron, D. 2011. “Conservative Party Conference Speech”. Speech, Manchester

- Carby, H. 1982. “White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood.” In Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies the Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain, 212–235. London: Hutchinson.

- Clémentine, C. X. 2017. “Against the Couple-Form.” LIES 1 https://www.liesjournal.net/volume1-03-againstcoupleform.html.

- Coontz, S. 2005. Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage. New York: Penguin Books.

- Davidson, J. O. 2015. Modern Slavery: The Margins of Freedom. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- El-Enany, N. 2020. (B)ordering Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press. “Ethics: Forced Marriage”. BBC. BBC. Accessed September 2, 2019. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/forcedmarriage/

- Fanon, F. 1970. A Dying Colonialism. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Fernandez, S. 2009. “The Crusade over the Bodies of Women.” Patterns of Prejudice 43 (3–4): 269–286.

- Foucault, M. 1979. The History of Sexuality. London: Penguin.

- Golby, A. 2018. “Liberated Sex: Firestone on Love and Sexuality.” MAI, November 28. https://maifeminism.com/liberated-sex-firestone-on-love-and-sexuality/.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2002. The Racial State. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

- Hall, R. A. 2002. “When Is a Wife Not a Wife? Some Observations on the Immigration Experiences of South Asian Women in West Yorkshire.” Contemporary Politics 8 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/13569770220130121.

- Hanhardt, C. B. 2013. Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence. Durham, MD: Duke Univ. Press.

- Haritaworn, J. 2015. Queer Lovers and Hateful Others Regenerating Violent Times and Places. London: Pluto Press.

- Jung, M. 2015. “Logics Of Citizenship And Violence Of Rights: The Queer Migrant Body And The Asylum System.” Birkbeck Law Review 3: 305–335.

- Kapoor, N. 2018. Deport Deprive Extradite. London: Verso.

- Kapur, R. 2004. Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism. London: GlassHouse.

- Mack, M. A. 2017. Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Maclintock, A. 1995. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest. New York: Routledge.

- Morgan, L. H. 1877. Ancient Society. New York:H. Halt and Company.

- Mosse, G. L. 1985. Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe. New York: Howard Fertig.

- Parmar, P. 1992. “Gender, Race and Class, Asian Women in Resistance.” In The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain. London: Routledge in association with the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 235–275. London: Hutchinson.

- Puri, J. 2016. Sexual States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rao, R. 2014. “The Locations of Homophobia.” London Review of International Law 2 (2) (January): 169–199. doi:10.1093/lril/lru010.

- Razack, S. H. 2004. “Imperilled Muslim Women, Dangerous Muslim Men and Civilised Europeans: Legal and Social Responses to Forced Marriages.” Feminist Legal Studies 12 (2): 129–174. doi:10.1023/b:fest.0000043305.66172.92.

- Rubin, G. 1975. “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the Political Economy of Sex.” In Toward an Anthropology of Women, edited by R. Reiter, 157–210. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Said, E. W. (1978) 2003. Orientalism. New York: Random House US.

- Said, E. W. 1993. Culture And Imperialism. New York: Knopf.

- Smith, E., and M. Marmo. 2011. “Uncovering the ‘Virginity Testing’ Controversy in the National Archives: The Intersectionality of Discrimination in British Immigration History.” Gender & History 23 (1): 147–165. doi:10.1111/j.14680424.2010.01623.x.

- Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book.„ Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 65–81. Accessed July 4, 2021. doi:10.2307/464747.

- Trivedi, P. 1984. “To Deny Our Fullness: Asian Women in the Making of History.” Feminist Review 17: 37. doi:10.2307/1395008.

- Warner, M. 1999. “Normal and Normaller: Beyond Gay Marriage.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 5 (2): 119–171. doi:10.1215/10642684-5-2-119.

- Wilson, A. 2006. Dreams, Questions, Struggles. Pluto. “Women Shoulder the Responsibility of ‘Unpaid Work’”. Office for National Statistics, November 10, 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/womenshouldertheresponsibilityofunpaidwork/2016-11-10

- Yegenoglu, M. 1998. Colonial Fantasies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.