ABSTRACT

This special issue of the Nonproliferation Review results from a project funded by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency, aiming to identify lessons learned from efforts to eliminate weapons of mass destruction (WMD) around the world. It contains edited versions of papers presented at a November 2015 workshop at the Washington, DC, offices of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. One section covers cross-cutting themes, including the strategic, diplomatic, legal, technical, and inter- and intra-agency dimensions of elimination. The second section discusses lessons learned from work in the former Soviet states, Iraq in the 1990s, Iraq in 2003–04, South Africa, Libya, and Syria. Major observations include that the field lacks institutionalization. There are few standing bodies with funding and responsibility for WMD elimination; each case usually emerges by surprise and has ad hoc character. Different combinations of states and international agencies may be involved, bringing varied authorities and competencies to different operational environments. A generic “checklist” approach accordingly may be best suited to applying past lessons to new missions. Among the few constants are a need for extensive coordination between partners and, where applicable, the WMD possessor, and the importance of cultivating high-level support for the mission, both nationally and internationally. Persistent gaps can be seen in both institutions and capabilities. These include the lack of any standing pre-crisis planning body or forum; a lack of sufficient capabilities for identifying and characterizing WMD, especially biological weapons; a lack of understanding of how to approach the dismantlement of foreign nuclear weapons, if necessary. Without continued investment in destruction technologies and organizations, new gaps are likely to emerge as today's parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention complete the destruction of their chemical-weapons stockpiles. Elimination is comparable to other areas of countering WMD. It would benefit from corresponding levels of attention and resources.

In mid-2014, a US-led coalition of states and international organizations completed a remarkable task: eliminating one of the largest remaining chemical-weapons (CW) stockpiles in the world, declared by Syria one year before. This effort concluded a process of elimination that began after the Syrian regime employed CW in a large-scale attack against civilians in Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus controlled by the opposition, in August 2013.

Although this effort was in many ways unique, it was far from the first of its kind. The United States and its international partners have sought to eliminate weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs in Libya, Iraq, and former Soviet states. In the case of South Africa, international agencies worked to verify the country’s unilateral WMD elimination ex post facto. This special issue provides new insights into these experiences and seeks to identify their lessons for the future.

Similar opportunities for elimination are likely to arise. At least three categories of potential elimination missions can be identified, including those of possessor states, North Korea being the most challenging case that can be foreseen; non-state actors, that are likely to be active within failed or fragile states or ungoverned territories; and residual cases, i.e., past WMD possessors that may never have completely disarmed, such as Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

In possessor states, any current or future WMD program might be a candidate for elimination. In addition to its well-publicized nuclear-weapon program and rapidly advancing missile capabilities, North Korea is thought to possess large stockpiles of CW and the ability to produce significant amounts of biological weapons (BW). In time, the opportunity to eliminate these programs may arise, either in cooperation with a North Korean government seeking to change its relationship with the outside world or in the event of the collapse or overthrow of the regime.

A handful of other states remain outside the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and are suspected of CW possession; one or more parties might also try to cheat. No state currently acknowledges an existing BW program, but concerns about the activities of some states go beyond just North Korea. There are five acknowledged nuclear-weapon possessors within the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), plus another four states outside the treaty: India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea. Non-nuclear NPT parties could also try to cheat.

The WMD elimination challenge is not limited to states' programs. As this special issue goes to press, the Islamic State (IS) organization is reported to have employed CW on the battlefield in Syria and Iraq. The group is believed to have used both chlorine and sulfur mustard, possibly of its own manufacture. IS may also be recruiting experts and establishing procurement pipelines to bolster those efforts. The United States and its partners may have opportunities, or feel compelled, to eliminate those capabilities. This is a new type of threat, involving a non-state actor operating inside failed or fragile states, including places like Iraq, Syria, and Libya—all states where CW elimination has taken place, but was not completed.

Background

Understanding the lessons of past elimination efforts should take place before the next crisis unfolds. Although this problem is hardly unknown to national-security policy makers, practitioners and close observers of WMD elimination have noted a tendency to “reinvent the wheel” at each opportunity to pursue such an effort. In most instances, there will be little time available for study or contemplation when the next instance of WMD elimination arises; the insights from these experiences should therefore be grasped today.

The overall record of preparedness for elimination missions is poor. The disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the nuclear, biological, and chemical insecurity it produced, caught most by surprise. Neither Iraq's 1990 invasion of Kuwait nor the extent of its unconventional-weapons programs were anticipated. Although the United States initiated the 2003 invasion of Iraq, partly on the basis of misperceptions of the status of Iraq's WMD programs, it entered the conflict largely unready to secure and eliminate the remnants of those capabilities, let alone what had been expected. Years of negotiation resulted in Libya's agreement to disarm, though implementation encountered unforeseen challenges, particularly after civil war erupted.

The opportunity to eliminate Syria's chemical weapons also arose unexpectedly, but it represents a different model, one of readiness. The US government and its allies and partners, including other governments and international organizations, were ready to take advantage of the opening precisely because they had spent months intensively preparing for potential CW-related contingencies. Thus, when the opportunity to eliminate Syria's CW arsenal arose, the international community was able to move swiftly. (See, in this volume, Philipp C. Bleek and Nicholas J. Kramer, “Eliminating Syria's chemical weapons: implications for addressing nuclear, biological, and chemical threats,” pp. 197–230.)

Recognizing the need for a comprehensive framework for eliminating WMD is not new. Nonetheless, while past cases of elimination have received considerable attention, no single work broadly captures their lessons for future policy and planning.Footnote1 This special issue is the culmination of a project funded by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency, intended to help governments, international organizations, and nongovernmental experts prepare for WMD elimination contingencies. Each article stands alone, but taken together, they cover multiple thematic areas and case studies. Early drafts were discussed at a November 2015 workshop at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Washington, DC, with over forty participants, including current and former officials from the US government, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations.

Defining WMD elimination

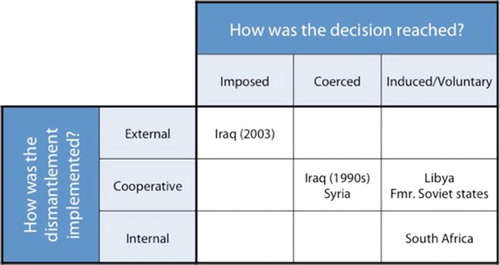

How to define WMD and WMD elimination formed an important part of discussions among contributors to this project. There is no single, generally accepted definition of WMD elimination, even within the US government. For the purposes of this project, WMD elimination was defined as efforts to eradicate nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons and their means of production and delivery that involve states other than their possessor. The decision to eliminate WMD might be directly imposed by outside forces, coerced or induced, or wholly internally driven (see ). Similarly, the implementation of elimination might be performed by external actors, cooperatively, or largely or exclusively by the possessor state.

Elimination carried out solely by the possessor state itself falls beyond this project's scope. For example, the elimination of declared CW and associated capabilities in the United States, although subject to verification by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the implementing body of the CWC, does not meet the definition for WMD elimination adopted here. Nevertheless, one of the case studies in this volume, involving South Africa, was included on the grounds that it offers useful lessons for future efforts within the project's focus, despite falling outside of the adopted definition. (See, in this volume, Olli Heinonen, “Lessons learned from dismantlement of South Africa’s biological, chemical and nuclear weapons programs,” pp. 147–62.)

Despite largely agreeing on a definition, individual authors still preferred to use the term in slightly different ways, as discussed in their articles. Some authors treated cooperative threat reduction programs (CTR) as falling within the elimination mission. (See, in this volume, Paul F. Walker, “Cooperative Threat Reduction in the former Soviet states: legislative history, implementation, and lessons learned,” pp. 115–29.) Others have included the control of dual-use capabilities, information, and expertise. This broader family of missions offers a number of relevant lessons.

The collection of papers is divided into two parts. The first part explores themes relevant to WMD elimination work, including strategic, diplomatic, legal, technical, and inter- and intra-agency dynamics. The second part covers six case studies: post-Soviet CTR, Iraq in the 1990s, Iraq in 2003, South Africa, Libya, and Syria. The authors have sought to identify best practices and lessons learned that future decision makers and experts should consider when planning and executing elimination missions.

While not an exhaustive treatment of the subject, this special issue provides what we believe is the most comprehensive overview of the issue to date, and one that, we hope, stimulates further analysis of these important topics.

Major observations

Based on the specific lessons identified in each of the articles, the November 2015 workshop, and subsequent discussions, several broad observations may be offered.

Lack of institutionalization

Despite considerable activity in the last quarter-century, WMD elimination lacks recognition as a well-bounded field with an associated professional community. Its scope is not firmly established nor agreed upon. There is no clearly identified group of experts covering these issues or responsible for them on a daily basis. There is neither a single template nor a clearly established lead organization for WMD elimination, either internationally or within the US government. Each new case is a “pickup game;” as a result, the available resources and authorities often must be applied creatively and flexibly.

A multiplicity of actors and conditions

At a minimum, each WMD elimination case involves a possessor state (or, in a non-state actor case, one or more host states), along with one or more international partners. Depending on the context, these partners can be states or international agencies such as the OPCW, the United Nations, the International Atomic Energy Agency, or the World Health Organization, each of which has unique authorities and competencies. They may be called upon to operate in “permissive” environments, where they can move and operate with relative freedom, or in “non-permissive” environments, where their security may not be assured. Sometimes certain types of information may not be shared among partners for reasons of security, legal limitations, or other reasons. These complexities demand intensive efforts at coordination, which sometimes have involved the creation of ad hoc bodies between or within governments and international organizations.

Within the United States alone, WMD elimination almost invariably involves multiple departments, agencies, and their components, with overlapping and potentially competing roles and their own diversity of authorities and capabilities. High-level support and attention are required to carry out the mission effectively, as well as a clear vision and capable leadership at both the political and operational levels. Furthermore, both strong working relationships and personal relationships between officials in different organizations are often necessary to clear the path for success.

Special demands of multinational collaboration

International coalitions are crucial to get virtually any elimination mission authorized, financed, legitimized, and accomplished. Working across national boundaries and organizations, however, also usually means WMD elimination is not conducted within the confines of a clearly defined chain of command or an established concept of operations. Control of activities in the field tends to be indirect; sometimes those activities are in the hands of the possessor state and its contractors. Sensitive issues such as sovereignty and public health are usually involved, as are multiple stakeholders, potentially down to the level of local communities, e.g., those hosting destruction facilities. This situation demands routine communication and cooperation to avoid misunderstandings and surprises and to synchronize what can be a complex set of activities. These circumstances demand flexibility and responsiveness. For these reasons, too, diplomatic interventions are a recurrent feature of elimination activity, to gain cooperation either by appealing to common interests, offering inducements, or threatening consequences. In most cases, US-Russian cooperation has been essential for both adopting an elimination mandate and executing it.

Sustaining institutional support

Beyond operational leadership, institutional support cannot be taken for granted. Activities that require significant money and time require stronger and deeper support than has sometimes been evidenced. For example, because Congress was deeply skeptical of the Russian and other former Soviet authorities, it imposed numerous conditions on CTR funds and activities, which complicated their implementation. In Iraq in the 1990s, some members of the UN Security Council gradually seemed to lose their appetite for supporting the inspection activities of the UN Special Commission, which led to the commission's dissolution and replacement. Because sustaining the political and financial support necessary to eliminate WMD has proven to be a challenge, advocacy for the mission, the identification of “champions” in key institutions, and the management of relationships should be viewed as essential activities.

The persistence of surprise

As noted above, surprise is common and flexibility is therefore crucial to success. Each case is different for a variety of reasons, including complex and heterogeneous legal and organizational environments. Governments, international agencies, and experts rarely anticipate cases of insecure WMD in time to plan and organize well in advance.

The Syrian case was a notable exception. The US government and its partners foresaw a possible opportunity and need to eliminate Syria's CW arsenal; thus, when that opportunity arose, they had suitable destruction technology, and the broader diplomatic, bureaucratic, and legal, context required to use it, at the ready. Even then, however, a great deal of flexibility was required to agree on a legal mandate and to organize suitable partnerships, modalities, and venues for destruction activities.

The need for investment

Preparation takes investment, especially in technology. The political and environmental sensitivities involved in elimination significantly complicate the problem; there is rarely an off-the-shelf technical solution that meets all needs. Continued research and development is therefore crucial, especially to develop highly adaptable destruction technologies. Furthermore, the resulting capabilities must be represented in acquisition budgets ahead of time, or they will not be available when needed. As a result, there is always a need to sustain institutional support for WMD elimination, in order to ensure that the resources and people to support the mission are available when WMD elimination gets underway.

Focusing on both technology and people

The definition of WMD elimination adopted here emphasizes weapons, their means of production, and their delivery systems. Nevertheless, many cases also illustrate the importance of a more comprehensive approach that covers the entire program, not only weapons. A similarly comprehensive approach is also crucial during the verification process to reconstruct the scope and scale of the WMD programs; verification should include access to documents and personnel. During and after elimination work, it will also be important to ensure that possessor-state scientists, engineers, and industrial specialists with sensitive knowledge find and remain engaged in constructive and peaceful work. Otherwise, as has happened in the past, they may end up contributing to the further proliferation of WMD.

The need for a “checklist”

Because of the complexity and unpredictability of the WMD elimination problem set, no single “playbook” or generic plan is likely to encompass every aspect of the problem or provide sufficient preparation. Instead, it may be more useful to use the lessons identified in this study to develop a framework or checklist that helps to identify and think through the crucial aspects of different situations and contingencies.

A partial checklist

In view of these observations, policy makers should consider the following issues, among others, when preparing for future elimination missions. This is not an exhaustive list and many more recommendations can be found in the specific case studies.

Prior to an elimination decision, the immediate challenge is to identify the proper mix of instruments of national and international power (military, economic, diplomatic, and others) to convince the state to abandon its WMD program. The Libyan case illustrates that it is possible to create a win-win formula both during the negotiations leading to the elimination decision and during the elimination process itself. (See, in this volume, Patrick Terrell, Katharine Hagen, and Ted A. Ryba, Jr., “Eliminating Libya’s WMD programs: creating a cooperative situation,” pp. 185–196.)

Once the elimination decision is taken, several important factors must be incorporated into the scope of the elimination mandate. These include an international and (when relevant) domestic legal basis for action, ideally through a UN Security Council resolution based on Chapter VII of the UN Charter; adequate and timely funding; a specific and well-defined mission, which includes a definition of what should be eliminated (weapons vs. programs); clearly defined political relations, including a dispute-resolution mechanism with the country to be disarmed; and an enforcement mechanism, ideally established through a Chapter VII mandate. To strengthen the nonproliferation regime and enhance international legitimacy, it is advisable to rely to the greatest extent possible on existing international treaties and regimes, while retaining as much flexibility and agility as possible. (See, in this volume, Robert A. Friedman, “Legal aspects of weapons of mass destruction elimination contingencies,” pp. 61–82.)

Decision makers should recognize that uncertainties about the completeness of elimination usually will persist after the mission ends. Even in the best case, a former possessor state will retain most of its weapon-related expertise and dual-use capabilities. As a result, the elimination mandate should incorporate mechanisms for effective verification and monitoring, preferably including access to people, documents, dual-use materials, as well as plans for the redirection of scientists. Decision makers should also recognize that immediate elimination goals and these longer-term activities are different and may even be in tension with each other. The relationship between these goals should be considered when developing the mandate, especially if responsibility for the elimination process and responsibility for subsequent verification and monitoring will fall to different entities.

Gaps in institutions and capabilities

The study also identified several institutional gaps relevant to WMD elimination at the international and US government levels. At the international level, notably, no organization or readily available mechanism exists for BW elimination. Another gap involves information-sharing, which is a particularly acute problem between international partners. For example, there are significant legal restrictions in the United States on sharing nuclear weapon-related information, such as the composition of materials, samples of material, and weapon design information. These restrictions could hamper future nuclear elimination efforts. Solutions and workarounds should be considered today, rather than later.

Within the US government, no single entity has clear responsibility for planning or executing WMD elimination missions. Furthermore, despite being charged with doing so, the military has not historically maintained the capabilities to carry out these missions. Funding these operations has proven challenging. In the United States, beyond the Department of State's Nonproliferation and Disarmament Fund and some Department of Defense programs, most US agencies do not have dedicated funding available for elimination. Special authorization is required to shift funds, which could impede timely action. Coordination among and within US government agencies will also be a key challenge. It is also an important challenge to identify resources (principally, though not only, money) and authorities (legal permission to engage in specific activities) to allow the government to act beyond its normal scope of activity. A standing pre-crisis planning body could provide a forum to identify and work through disagreements. The establishment of such a standing body should be considered.

There are also gaps in capabilities relevant to elimination. Two examples are particularly noteworthy. First, there are insufficient diagnostic capabilities to identify and characterize WMD in a timely manner, especially BW. Second, nuclear weapons have never been dismantled by a country other than the one that built them, and could pose special challenges should the possessor state be uncooperative. Identifying ways to close these gaps should rank high among research-and-development priorities for WMD elimination.

Gaps in capabilities go beyond the availability of technologies; they also include training, equipment, and other resources. To prepare for future cases, concerned governments should work more closely with partners and international organizations to develop contingency plans, provide training, and supply necessary elimination technologies.

Furthermore, institutions and capabilities should not be considered independently of each other. Governments and international agencies will be hard-pressed to maintain one without the other. The sporadic and typically unpredictable nature of WMD elimination contingencies feed into this dynamic. The need for institutions to sustain capabilities, and vice versa, will become especially relevant in the chemical field after today's CWC parties complete the elimination of their CW stockpiles.

Creating standing national and international bodies could help to internationalize planning and implementation, and to establish, maintain, and promote technical capacities. Doing so would open “on-ramps” to a wider range of potential elimination missions. Wherever planning takes place, it would be best served by using a range of scenarios for planning technical options, consulting early with the full range of stakeholders who could support or challenge technical decisions, developing strong communications plans, and ensuring that planning accounts for critical enabling technologies.

Conclusion

For all its complications, ensuring the viability of WMD elimination in the face of legal, organizational, technological, budgetary, security, and other constraints should be a matter of concern to all seeking to enhance national and international security. Elimination is not synonymous with global disarmament; prioritizing it should be a matter of consensus, independently of one's views on the practicality or desirability of a world without nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons. In this sense, elimination could be compared to better-institutionalized activities in the WMD arena, such as verification or materials security.

This special issue should not be the last word on the topic of WMD elimination. Instead, we hope it will prompt governments, international organizations, and nongovernmental experts to deepen their engagement with these important issues.

Notes

1. See, for example, United Nations Monitoring, Verification And Inspection Commission, “Compendium on Iraq's Proscribed Weapons Programs,” June 27, 2007, Chapter VIII, “Observations and Lessons Learned,” <www.un.org/depts/unmovic/new/documents/compendium/Chapter_VIII.pdf>; Trevor Findlay, “The lessons of UNSCOM and UNMOVIC,” Verification Yearbook 2004, VERTIC, <www.vertic.org/media/Archived_Publications/Yearbooks/2004/VY04_Findlay.pdf>; Raymond T. Van Pelt, “JTF - WMD Elimination, An Operational Architecture for Future Contingencies,” April 28, 2004, The Industrial College of the Armed Forces, National Defense University (NDU), <www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA436471>; Rebecca K.C. Hersman and Todd M. Koca, “Eliminating Adversary WMD: Lessons for Future Conflicts,” Strategic Forum, No. 211, October 1, 2004, <http://wmdcenter.ndu.edu/Publications/Publication-View/Article/627032/eliminating-adversary-wmd-lessons-for-future-conflicts/>; Rebecca K.C. Hersman, “Eliminating Adversary WMD: What's at Stake?,” NDU Occasional Paper 1, December 2004, <http://wmdcenter.dodlive.mil/files/2012/02/Eliminating-Adversarial-WMD.pdf>; Johnny Hall, Jr., “Compelled Compliance: WMD Elimination in the New Era of Arms Control,” Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, September 2006; Łukasz Kulesa, “Elimination of Chemical Weapons Stockpiles: Lessons for Syria,” The Polish Institute for International Affairs, No. 100 (553), September 25, 2013, <www.pism.pl/files/?id_plik=14792>; Norman Cigar, “Libya's Nuclear Disarmament: Lessons and Implications for Nuclear Proliferation,” MES Monographs No. 2, Marine Corps University, January 2012; and Zachary Kallenborn and Raymond A. Zilinskas, “Disarming Syria of its Chemical Weapons: Lessons Learned from Iraq and Libya,” CNS Issue Brief, Nuclear Threat Initiative, October 31, 2013, <www.nti.org/analysis/articles/disarming-syria-its-chemical-weapons-lessons-learned-iraq-and-libya/>.