ABSTRACT

Concerns that biological weapons will be used has focused attention on the need to develop a capability to independently investigate any allegation of use. The United Nations Secretary-General’s Mechanism is one such tool, and efforts to revitalize and strengthen it have acknowledged a wide range of technical difficulties to overcome. This article emphasizes another aspect of the investigatory process: communicating the findings of an investigation. The article frames the investigation report as more than a technical recounting of what the investigators did and found, regarding it instead as the means by which the policy-making audience “makes sense” of the allegation. Drawing on literatures associated with science policy and “boundary objects,” the article reflects on the guidance provided thus far and suggests there has been an implicit move toward seeing the reports as “boundary documents.” The suggestion made here is that this implicit recognition should be now made explicit so that the critical position of the report is better appreciated. This has implications for the training of rostered experts.

The 2018 Agenda for Disarmament notes that “the very idea of the deliberate use of disease as a weapon is universally seen as repugnant and illegitimate. No country professes publicly to possess biological weapons or to require them for national security.”Footnote1 Yet concerns remain that such weapons will be used. Uncertainty about the potential of emerging areas of science and technology have featured prominently in these concerns,Footnote2 but recent events such as the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and repeated use of toxic chemicals in Syria have also acted as “focusing events”Footnote3 for those exploring ways to deter and mitigate the use of biological weapons (BW). At the center of the regime against BW, for example, states parties to the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC) are giving increasing consideration to issues of assistance, response, and preparedness, including as part of their current intersessional process. In the wider regime, efforts are also being made, including by updating and strengthening the United Nations Secretary-General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons (SGM). This mechanism, by which the secretary-general can promptly investigate allegations brought to their attention concerning the possible use of biological (and chemical) weapons, has, to date, only been used thirteen times. With the exception of an investigation into use of mycotoxins,Footnote4 these have been investigations into alleged use of chemical weapons, which provides some understanding of why the biological side of the mechanism is currently underdeveloped. Accordingly, strengthening the international capacity to investigate “any alleged use of biological weapons” so that “any illegal acts will be quickly detected” would make a significant contribution to deterring use.Footnote5

Many of the efforts to update and bolster the biological side of the SGM have focused on updating its technical aspects. In part, this is because the very nature of a biological attack is highly complex: a biological event could be the result of an accidental or deliberate release, but it may also be natural in origin; it could be directed against humans, animals, or plants; and it is likely that misinformation and disinformation will be rife during both a spreading disease outbreak and in the event of apparent BW use. These factors will make the determination of use and subsequent attribution a complex technical undertaking. Additionally, the SGM currently has no network of designated and accredited laboratories that can analyze samples during an investigation into alleged BW use, “leaving the BW capacity of the UNSGM comparatively underdeveloped and uncertain.”Footnote6 This lack of capacity for biological investigations to rely upon makes the investigation more complicated, and the need for technical strengthening greater.

However, technically proving whether use has occurred is only one aspect of the investigation. Investigators must also communicate what they did during the investigation, their findings, and their conclusions to the secretary-general, who in turn passes their report to the Security Council and General Assembly. Given the fundamental nature of the technical issues to be addressed, the task of writing a report may easily be overlooked. Yet the report is “one of the most critical elements of the investigation.”Footnote7 The report must show that the investigators have performed due diligence and come to a reasonable conclusion as to whether BW have indeed been used.

The purpose of this article is to examine this communicative role of the SGM report. The article will demonstrate how considering the SGM report as a “boundary object” enables us to understand the importance of these reports in communicating the conduct and findings of investigations. The article begins by outlining how the guidance on report writing developed from 1984 to 1989, before considering the latest set of updates, which occurred in 2007. The article then details an implicit move toward viewing reports as “boundary documents,” which connects the world of the investigation to the policy world. The final report of the latest SGM mission typifies this idea of a boundary document: by using a discursive narrative to straddle the worlds of science and policy making, it helps those in the policy-making world make sense of the investigation and allegation. Future investigation reports should adopt this boundary approach explicitly so that rostered experts can receive approropiate practice and training in communication alongside the technical training they receive.

Origins of the mechanism and pre-2006 guidance on drafting investigation reports

Efforts to ensure that the secretary-general has at their disposal the capability to investigate any allegation of BW use have tended to focus on the technical aspects of an investigation, such as the number of experts and laboratories that the secretary-general can call upon. This tendency has been shaped by the evolution of the mechanism itself and the wording of the associated General Assembly resolutions.

The origins of the SGM lie in allegations of chemical-weapons use in the late 1970s and early 1980s and the adoption, by vote, of Resolution 35/144 C, which gave the secretary-general the authority to investigate them.Footnote8 This authority was reconfirmed two years later in 1982 through the adoption, again by vote, of resolution 37/98 D, which requested the secretary-general to

investigate, with the assistance of qualified experts, information that may be brought to his attention by any Member State concerning activities that may constitute a violation of the Protocol or of the relevant rules of customary international law in order to ascertain thereby the facts of the matter, and promptly to report the results of any such investigation to all Member States and to the General Assembly.Footnote9

Requests the Secretary-General to carry out investigations in response to reports that may be brought to his attention by any Member State concerning the possible use of chemical and bacteriological (biological) or toxin weapons that may constitute a violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol or other relevant rules of customary international law in order to ascertain the facts of the matter, and to report promptly the results of any such investigation to all Member States;

Requests the Secretary-General, with the assistance of qualified experts provided by interested Member States, to develop further technical guidelines and procedures available to him for the timely and efficient investigation of such reports of the possible use of chemical and bacteriological (biological) or toxin weapons;

Also requests the Secretary-General, in meeting the objectives set forth in paragraph 4 above, to compile and maintain lists of qualified experts provided by Member States whose services could be made available at short notice to undertake such investigations, and of laboratories with the capability to undertake testing for the presence of agents the use of which is prohibited. Footnote10

Common to these resolutions is the idea that “qualified experts” will undertake the investigation into allegations of use so as to establish “the facts” surrounding the allegation. These facts will be “promptly” reported to the secretary-general, who will then report the results to “all Member States” so that they can judge responsibility. The 1987 resolution also requests the secretary-general “with the assistance of qualified experts” to develop “further technical guidelines and procedures.” This formulation of words acknowledges prior efforts to produce technical guidelines and procedures.Footnote11

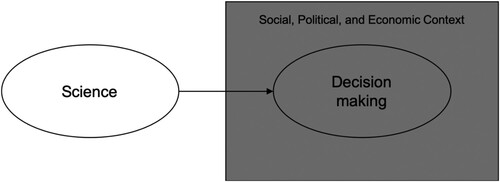

From a standpoint of the relationship between science and decision making in policy, the resolutions strongly invoke aspects of what is known as the “inverted decisionist model.” A graphic representation of this model is presented in .

Figure 1. Representation of the “inverted-decisionist” model. Adapted from Patrick van Zwanenberg and Erik Millstone, BSE: Risk, Science, and Governance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) p. 25.

In this model, scientific and policy-making deliberations are portrayed “as if they took place in separate compartments,” and as though science takes place in a social and political vacuum.Footnote12 Deliberations in the policy-making sphere are informed by the scientific inputs, but the model suggests that there is only a unidirectional influence between the two: scientific deliberations can influence policy, but policy cannot influence scientific deliberations. In some interpretations of this model, policy making is viewed as being unable to influence science because policy deliberations will “only commence once scientific experts have completed their deliberations and made their determinations.” Footnote13 In the case of the resolutions, science and policy are similarly portrayed as taking place in separate compartments: the investigations will be conducted by qualified experts and member states will be informed; the development of guidelines and procedures for investigations is to be the domain of another set of qualified experts who will also take charge of compiling and maintaining the lists of experts qualified to investigate and the laboratories with the capability to support the investigation.

While the General Assembly was invoking an inverted-decisionist understanding, the working methods of a group of “qualified experts” engaged to develop further the technical guidelines departed from this model in a number of ways. They convened, for example, “a total of three informal meetings open to attendance by representatives of any interested Member State to permit those representatives to express their views informally regarding procedures for investigation” and accepted “comments and recommendations from interested Member States on the group’s informal joint working paper,” which proved “extremely valuable” in the preparation of the final report.Footnote14 These methods allowed policy (“representatives of any interested Member States”) to influence science (“express their views … regarding procedures for investigations”) – running in the opposite direction to the inverted-decisionist model.

Nevertheless, the eventual report from the 1987 group of experts mimicked the compartmentalization of science from policy as per the inverted-decisionist model. Their twenty-page section on guidelines and procedures covered all aspects of the investigation process up to and including the drafting of the investigation report for the secretary-general.Footnote15 Nine appendices associated with the guidelines and procedures followed, detailing technical matters such as equipment for investigations (Appendix III); lists of areas of expertise for qualified experts (Appendix IV); sampling procedures for both physical and biomedical samples (Appendices VII and VIII); and model interview questions.Footnote16 The General Assembly considered and endorsed the report without qualification in 1989.Footnote17 Policy informed science, in order for science to inform policy.

In drafting the investigation report, the 1987 group of experts chose to remove much of the detail that had been proposed by a prior group of consultant experts charged to perform a similar task in 1984. Gone, for example, were many of the proposed prescriptive elements of the nature of the evidence to be listed, which, in 1984, had been suggested as

on-site inspection and collection of evidence at the location of the alleged attack; examination of human corpses or casualties; examination of dead or affected animals; analyses of the different types of samples; interviews with eyewitnesses and other witnesses; documentary evidence; etc.Footnote18

In order to conclude the investigation, the team of qualified experts should as early as possible, evaluate all the information available to it, including the results of the laboratory analyses, with a view to preparing its final report. The final report prepared by the team for submission to the Secretary-General should include the following:

Information on the composition of the team at various stages in the investigation, included during the preparation of the report;

All relevant data gathered during the investigation;

A description of the investigation process, tracing the various stages of the investigation with special reference to (i) the locations and tine of sampling and in situ analyses, (ii) supporting evidence, such as records of interviews, the results of medical examinations and scientific analyses, documents examined by the team, and (iii) locations and dates of deliberation on the report as well as the date of its adoption,

Conclusions proposed jointly by the team of qualified experts, indicating the extent to which the alleged events have been substantiated and possibly assessing the probability of their having taken place,

Individual opinions by a member or members of the team of qualified experts dissenting from the majority or differing on any of the points listed above should also be recorded in the report.Footnote20

This guidance moved away from a prescriptive structure and toward a set of guidelines that informed what the report should communicate. In doing so, the guidance recognized that different reports in different contexts have different purposes and thus different needs in terms of communication. For example, a less complex investigation may not require a detailed account of on-site investigations or examination of animal corpses and casualties. Through loosening the suggested requirements on the report authors, the needs of the investigation and its policy context were acknowledged as the primary drivers of report writing.

Efforts to strengthen the mechanism 2006

The guidance contained within the 1989 experts’ report stood until the 2006 UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy “somewhat unexpectedly” included reference to the SGM.Footnote21 The direction provided by the General Assembly in the Global Counter Terrorism Strategy followed the familiar pattern of encouraging the secretary-general “to update the roster of experts and laboratories, as well as the technical guidelines and procedures, available to him for the timely and efficient investigation of alleged use.”Footnote22 The United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs was charged with assisting the secretary-general in this task and organized two meetings in 2007 with an assembled group of experts that included representatives from relevant international organizations. These experts chose to leave the 1989 main document unaltered and instead concentrated their efforts on updating the appendices associated with the guidelines and procedures, with a “focus on relevant technical biological aspects of investigation of alleged use.”Footnote23

Changes in the socio-technical and geopolitical environment necessitated this focus on the biological side of the SGM so as to address “the misplaced belief that the biological weapons problem was resolved.”Footnote24 Between 1992 and 2006, when Carleton University’s Jez Littlewood argues that the SGM ossified,Footnote25 United Nations inspectors in Iraq uncovered details of an offensive BW programFootnote26; Cuba requested that a BWC Consultative Committee be called to investigate its claims that a US government airplane sprayed a substance over Cuba containing the insect Thrips palmi;Footnote27 efforts to negotiate a legally binding verification mechanism that would have established an organization capable of conducting a field investigation of alleged use had collapsed;Footnote28 and negotiations for the Chemical Weapons Convention were concluded and the resulting convention entered into force. In addition, the period saw increasing concerns about possible terrorist interest in using non-conventional weapons, including BW.Footnote29 These concerns reached a climax in the aftermath of the “Amerithrax” campaign that began shortly after the attacks on September 11, 2001.Footnote30 Concern about non-state actor interest in BW remains high.Footnote31

Reflecting the decision to focus on the strengthening of the biological side, the nature of the updates made in 2007 included, for example, the experts’ suggesting that information about transmissibility and data about effects on humans and animals (e.g., epidemiological data, treatments and countermeasures used, and response to treatments and/or countermeasures) be provided in the types of information that a member state was to convey to the secretary-general when reporting an allegation of use.Footnote32 Four new areas of expertise were added to Appendix IV, including the evaluation and rendering safe of military and improvised explosive devices and expertise in forensics.Footnote33 The guidance for sampling—what had been Appendices VII and VIII of the 1989 report—underwent significant updating, as did Appendix IX on interviewing witnesses and victims.Footnote34 In both cases, the detailed guidance of the 1989 report (e.g., the nature of questions to be asked during an interview) was removed in favor of more general guidance.

The assembled experts also created three new appendices: Appendix A, “Pre-mission planning;” Appendix B, “Measures to protect the confidentiality of investigations of alleged use of chemical, biological, or toxin weapons”; and Appendix C, “Report of investigation activities.” In Appendix C, the experts suggested that investigators consider a far more elaborate structure on which their reports “could be modeled … [and] adjusted as needed” than had been previously suggested.Footnote35 The updated structure proposed a report of two parts: a “non-technical” part and a series of technical appendices. It was suggested that, in the “non-technical” part of the report, investigators might consider including an executive summary, details of pre-investigation activities, investigation activities, and findings. Following from that, the proposal was for a series of technical appendices. Eleven were suggested, including terms of reference; administrative data, including team personnel; lists of samples, evidence collected, medical investigation activities; results of analysis and clinical diagnostics; records of interviews; and records of chain-of-custody activities and tags and seals.Footnote36

These changes reflect, again, an acknowledgement of the role that the SGM report plays in the policy process. By providing a non-technical summary of activities and findings as well as a longer technical part, the guidance acknowledges that the report must speak to policy makers and their technical advisers. In acknowledging these two communities (one technical, one political), the guidance reflects the different requirements and expectations of each. The report had to straddle the boundary between the two communities, speaking to both while still being a singular document.

Investigation reports as “boundary” documents

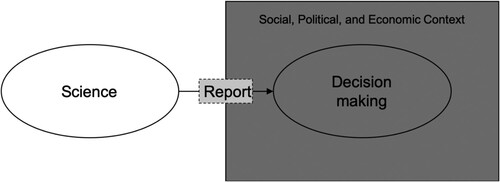

The working methods of both the 1989 and 2007 groups of experts, and their guidance to SGM investigators concerning the report, suggest that the sharp distinction in the relationship between science and policy as envisaged by the inverted-decisionist model is a weak guide for practice. The experts instead appear to be situating the report as being part of, rather than separate from, the policy process. Although the investigation remains separate from the policy process, the experts appear to be conceiving of the report as sitting on the boundary between the science of the investigation that has taken place, and the deliberations in the policy context that will follow.

This is an elaboration of the inverted-decisionist model, implicit though it may be. In this elaboration, the report is placed across the boundary between science and decision making, and mediates the transfer of scientific knowledge into the social, political, and economic context of the decision-making fora. A graphic illustration of this is presented in . Locating the report here means that it plays a role in shaping the social, political, and economic context, rather than simply communicating to decision makers.

Figure 2. Representation of the “inverted-decisionist” model including the location of the report. Author’s elaboration of van Zwanenberg and Millstone, BSE, p. 25.

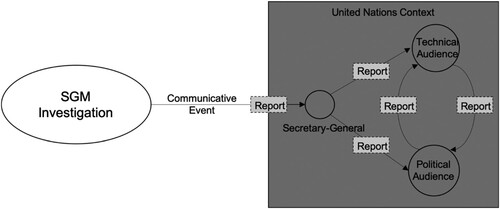

From a social-science perspective, the latest proposed report structure also suggests two further points. First, is an acknowledgement that the investigation is “performative,” i.e., it is performed “for others,”Footnote37 and so communicating what was involved in that work and what was found naturally involves “an ‘audience’.”Footnote38 In the case of the SGM, the report is prepared by the investigators for the secretary-general, who is then required to promptly inform the member states in the General Assembly and/or Security Council of the investigation results. These three audiences are located within a single political environment—the United Nations—but they are not homogeneous and comprise both political and technical constituents.Footnote39 The 2007 proposed report structure reflects this by spliting the report into a single thread with technical appendices so that it can “perform” for its multiple audiences, political and technical.

Second, and related, is the framing of the report as a “communicative event.”Footnote40 Viewing the report as sitting at the boundary between science and policy allows it to act as a “bridge between intersecting social and cultural worlds.”Footnote41 The report facilitates communication between these worlds by giving a common framework of understanding to the allegation and investigation. The SGM report, therefore, plays a dual role: it presents the activities and findings of the mission to the secretary-general and also facilitates discussions within the policy domain by creating a shared frame of reference for policy makers to discuss science. This dynamic is presented in .

Figure 3. Representation of the “inverted-decisionist” model incorporating a representation of context and use of the report. Author’s elaboration of van Zwanenberg and Millstone, BSE, p. 25.

One of the most effective ways to create this shared frame of reference is through the use of a discursive narrative,Footnote42 which cognitive scientists argue has “privileged status” in human cognition.Footnote43 However, in this case, the diversity of audience constituents means that the report must tell two narratives or “stories.” To the political constituents of the report’s audience, the proposed report structure implies the telling of a “what story”—what the investigators did and when, what they found, and whether it confirms the allegation that triggered the investigation. This “what story” is located in the main body of the report. To involve the technical audience, a different story needs to be relayed—a “how story”—which communicates, via the presentation of technical and methodological details in the appendices, the activities and findings of the mission as authoritative, robust, and comprehensive. This “how story” is of critical importance in providing a basis for discussions about the veracity and trustworthiness of the mission findings.Footnote44

Although two narratives are suggested by the report structure, neither they nor their receiving audiences are entirely separable. The political story of “what happened” needs to include some statement of technical facts to assure readers of reasons for the story, and the technical story of “how we know” must include some political facets in interpreting and explaining findings. In reality, however, this single report, giving a pair of separate but not entirely separable narratives to different but overlapping audiences, requires the production of a single narrative that communicates to both audiences effectively without confusing or excluding either.

In the latest invocation of the SGM, the idea that the report sits across boundaries and must involve both policy and technical constitutents is evident. This mission, headed by Professor Åke Sellström, was charged by the secretary-general to ascertain facts relating to allegations of chemical-weapons use in Syria. It produced two reports: an interim report circulated on September 16, 2013, focusing on the use of toxic chemicals in Ghouta on August 21, and a final report circulated on December 13, 2013, which conveyed findings on seven allegations of toxic chemical use in Syria.Footnote45 The final report was “generally seen as a report that was well crafted to respond effectively to the different requirements and expectations pertaining to a SGM Mission Report” and “a possible model for how reporting can be achieved.”Footnote46 There is instructive value, then, in considering how the Mission chose “to communicate information in ways that allow the recipients to understand the reported events and activities in their context, and to communicate assessments in ways that are relevant for political audiences.”Footnote47

Deconstructing the Sellström Mission’s final report

The understanding that an investigation report needs to involve its audience is evident in both the structure and content of the final report. From a structural point of view, the report follows the proposal made by the experts in 2007 to have a short and less technical front part followed by a series of appendices where the technical details of the investigation are conveyed. However, the Mission report also departs from the proposed structure. The section headings from the guidance and those which appear in Sellström’s final report are shown in .

Table 1. Comparison of 2007 SGM guidance with SGM final report 2013

Two points of departure are immediately obvious when the structures are compared. First, the final report is organized differently, the seven allegations that the Mission investigated forming the organizational spine of the technical appendices, rather than the different categories of data that were collected. The second point of departure is the more comprehensive front section of the report, which includes as its first offering the Mission’s terms of reference.

The decision to present the terms of reference as the first thing the audience reads is interesting. Andrew D. Brown describes the inclusion of terms of reference in official reports as an effort to establish provenance and authority.Footnote48 By placing them at the start of the final report, the document takes on a performative tone and immediately involves the audience by offering them a political and legal justification for the existence of the Mission. Given the fractured political environment in the Security Council and elsewhere in December 2013, an early demonstration of provenance and authority was clearly necessary. However, the Mission’s interim report released in September 2013 similarly presented the terms of reference at the start of that report.Footnote49 As the interim report had been circulated in a much more unified political climate where “no one doubt[ed] that poison gas was used in Syria,”Footnote50 this suggests a more deliberate action on the part of the report writers to engage their audience and establish political and legal provenance from the start. Such demonstrations are dispersed throughout the entirety of the final report with repeated references to the various guidelines and frameworks that the Mission adhered to, such as “the United Nations Mission adhered to the Guidelines and Procedures for the conduct of investigations set out in A/44/56”;Footnote51 and Appendix 1 lists relevant legal instruments, guidance, and other agreements.Footnote52 These demonstrations show that the authors understood their audience and were keenly aware of their audience’s cultural norms and expectations.

While attending to the needs of their audience may be expected, the final report stands out for its use of discursive narrative as a means to convey the complex details of the investigations. One of the first extended passages of narrative is a chronological account of the Mission which lasts thirteen paragraphs and is to be found in the third section of the report.Footnote53 In these paragraphs, the reader learns from the perspective of the investigators a sequence of events that influenced their work.Footnote54 From the perspective of communication, the narrative conveys the many practical difficulties of conducting that Mission and provides what Brown calls “good reasons” why the investigators made particular decisions with regard to their methodological performance.Footnote55 Eight of these paragraphs detail what the Mission did before deploying to Damascus, with tempo conveyed through description of the head of mission and advance team deploying to Cyprus at the beginning of April (para. 30); their work in country being delayed (paras. 31 and 33) and how the Mission utilized this unexpected delay, including by developing “a concept of operations and tools for planning”; establishing “criteria for the selection of witnesses and the conduct of interviews”; receiving “security and relevant technical training”; meeting with government officials and technical experts from several countries; and conducting “fact-finding activities in Turkey.”Footnote56 This lengthy preamble to the in-country activities, as well as the multiple points when the Mission’s objectives changed, conveys to the reader a sense of a mission that became complicated by events outside of the tasks it was charged to perform.

These details, and others, are conveyed to the reader through what Brown calls a “vicarious experience” that “permits us to understand the world from the perspective of others.”Footnote57 The utilization of a vicarious experiential narrative is most evident in the findings section of the report. A narrative for each of the seven allegations investigated is provided and places the technical results of what the Mission found in a context that enables a clear relationship to “what happened.” In each mini-narrative, a number of fine-grained details are provided that invite the reader to vicariously experience the attack from the perspective of those affected. In the narrative for Khan al-Asal, for example, the reader is told,

an incident occurred on 19 March at approximately 0700 hours, in the Haret Al Mazar neighborhood, which consists of a one-story building surrounded by a farming area. The location is close to the shrine of Sheikh Ahmad Al Asali located at the southern part of the Khan Al Asal village in the vicinity of a position held at the time by the armed forces of the Syrian Arab Republic in the Aleppo governorate.

During the ongoing shelling in the area, deaths, with no signs of wounds, and persons exhibiting symptoms of intoxication were suddenly observed and reported to survivors and first responders …

One survivor stated that “the air was static and filled with a yellowish-green mist and filled of a strong pungent smell, possibly resembling sulfur.”Footnote58

on 24 August 2013, a group of soldiers were tasked to clear some buildings under the control of opposition forces. Around 1100 hours, the intensity of the shooting from the opposition subsided and the soldiers were under the impression that the other side was retreating. Approximately 10 meters away from some soldiers, an improvised explosive device reportedly detonated with a low noise, releasing a very badly smelling gas. A group of 10 soldiers was evacuated in armoured personal vehicles to the field medical point with breathing difficulties and with, not further specified, strange symptoms.Footnote59

These fine-grained details for Khan al-Asal—the one-story building, the shrine of Sheikh Ahmad al-Asali, the deaths with no signs of wounds, and the survivor’s description of the air—and for Jobar—the task assigned to the soldiers, the lessening of the intensity of the shooting at 11:00 hours, the impression this gave the soldiers, the armored personnel vehicle—bring the readers of the report into the world of those affected and the investigation. In addition, such details contextualize the technical information that follows, providing an overview of weather patterns, munitions, symptoms, etc.

Recognizing that the audience is also technical, the methods of communication used in the appendices stand in stark contrast to how investigation activities and findings are conveyed in the front part of the report. The appendices are more than twice as long as the front part of the report and act as the fulfilment of the Mission’s terms of reference “to ascertain the facts related to the allegations of use of chemical weapons, to gather relevant data, [and] to undertake the necessary analyses for this purpose.” Demonstrations of provenance, authority, and robustness are essential tasks in this section, and a series of staccato statements result, such as those in the opening three paragraphs of the methodology section:

The Mission was guided by the United Nations Guidelines and Procedures for the timely and efficient investigation of reports of the possible use of chemical and bacteriological (biological) or toxin weapons (A/44/561), as well as the modern scientific standards applied by OPCW [Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons] and WHO [World Health Organization] for their respective specializations.

The three pillars of modern investigative methodology are:

Appropriate chain of custody of procedures applied to all collection of evidence.

Validated methodology used for acquiring and analysing evidence.

Personnel used must have the appropriate training.

This United Nations Mission collected the following types of evidence: biomedical samples, environmental samples, witness interviews/statements (collected as audio and video records) and documents/photos/videos received from Government or opposition representatives or witnesses.Footnote60

As previously noted, the allegations form the organizational spine of the technical section, each investigation having its own appendix. These appendices are much longer than their counterparts in the front part of the report and are notably different. In place of direct quotation material from witnesses and the inclusion of fine contextual details is the use of Google Earth images, photographs, charts, and tables, and the discussion of methods and findings are more in-depth and elaborate. This change in style and content suggests that the authors recognize, and are trying to directly involve, a different audience from those engaged in the front section. The use of different forms of data to convey the same meaning suggests this new audience has different criteria for judging the quality, comprehensiveness, and robustness of the Mission’s work.

Conclusions

For good reasons, efforts to strengthen the SGM have, to date, tended to focus on the technical aspects of biological investigations. These investigations will be complex undertakings, and it is essential from the standpoint of deterring use that there is a fully functioning and technically strong mechanism at the disposal of the secretary-general to investigate any allegation. However, this focus on the technical may mean that other critical elements of the investigation, such as report writing, have been overlooked.

The suggestion made in this article is that, in the last two rounds of guidance on report writing, the groups of experts have begun to implicitly recognize that SGM investigations are performative (i.e., done for others) and thus the reports are a communicative event that seeks to involve its audience. The most recent SGM report, the 2013 final report of the Sellström Mission, takes this a step further and employs communication devices that deliberately recognize and engage with the report’s diverse audiences and draw them into the world of the investigation. As such, the report is implicitly being reframed as a boundary document, which acts as a bridge between the two communities of science and policy. The report facilitates communication between and within them by providing a common framework to understand the allegation.Footnote62

However, writing a report that actively engages multiple communities with different needs and criteria for judging quality and robustness is extremely difficult. There is the added pressure of producing the report within a specific and short time frame. Such were the levels of difficulty that the Office for Disarmament Affairs identified the requirement to produce a final report “with appropriate balance between ‘science’ and political/legal ‘narrative’” as one of the key challenges of the Sellström Mission.Footnote63

Recognizing explicitly that the investigation report is a boundary document and acting accordingly could assist in overcoming this challenge in the future. Being explicit about the role that the report plays in ascertaining whether a biological (or chemical) weapon has been used has a number of important implications. First, it underscores the critical role that the report plays in “making sense” of the allegation. Both communities involved in the policy-making deliberations that follow the report must first understand the report and its contents and make sense of its findings before they can productively discuss policy in light of it. Although the investigation is a technical process, a chronological retelling of technical facts will not enable the audience to “make sense” of what the inspectors did, why they did it, and what they found. Instead, an alternative mechanism needs to be used, such as the technique displayed in the final report of the Sellström Mission, where demonstrations of authority, comprehensiveness, and robustness sit alongside vicarious experiential narrative to help both communities understand the investigations’s findings and its methods in a way that enables policy deliberations.Footnote64

Second, and related, the SGM’s activation requires an allegation of use. In the “congested and messy information space” of twenty-first-century conflicts, this means that it is likely that a future SGM report will enter a highly contested decision-making process.Footnote65 Future mission reports must be able to withstand intensive scrutinty that may, or may not be, technical in nature. Understanding the needs, culture, and expectations of the audience as the report is being written will assist in crafting a report that communicates the robustness, veracity, and trustworthiness of the investigation more effectively.

Finally, and on a practical level, viewing the investigation report as a boundary document suggests the need for future SGM rostered experts to be provided with opportunities to practice writing a report. These opportunities could be part of the enhanced training that experts are already provided, sitting alongside the necessary technical training they receive so that thinking about what and how to communicate is incorporated within all aspects of the investigation process. These opportunities should not just focus on what the experts communicate but on how they communicate, and include practice delivery to members of both audiences so that their reactions can further inform the learning process. Through providing training and practice, reports can be better authored to perform their boundary function effectively and to enable communication between and across the two communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Research used in this article was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (Award number: ES/L014505/1) and the University of Sussex-Economic and Social Research Council Doctoral Training Centre (Award number: 1365014).

Notes

1 United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, “Securing our Common Future: An Agenda for Disarmament,” New York, 2018, p. 24.

2 For recent examples, see Australia, “Review of Developments in the Field of Science and Technology Related to the Convention—Synthetic Biology,” BWC/MSP/2019/MX.2/WP.4, July 23, 2019; Statement of the high representative for disarmament affairs, Izumi Nakamitsu, as delivered by Anja Kaspersen, director of UNODA Geneva Branch, December 4, 2018; Kolja Brockmann, Sibylle Bauer, and Vincent Boulanin Bio, “Plus X: Arms Control and the Convergence of Biology and Emerging Technologies,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), March 2019, <www.sipri.org/publications/2019/other-publications/bio-plus-x-arms-control-and-convergence-biology-and-emerging-technologies>.

3 Thomas Birkland “Focusing Events, Mobilization and Agenda Setting,” Journal of Public Policy, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1998), pp. 53–74.

4 See United Nations General Assembly, “Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons. Report of the Secretary General,” A/36/613, November 20, 1981; United Nations General Assembly, “Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons. Report of the Secretary General,” A/37/259, December 1, 1982.

5 United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, “Securing our Common Future,” pp. 27–28.

6 James Revill, “Compliance Revisited: An Incremental Approach to Compliance in the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Occasional Paper No. 31, August 2017, p. 27.

7 Second UNSGM Designated Laboratories Workshop Report, Spiez, Switzerland, June 22–24, 2016, p. 15.

8 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 35/144 C, December 12, 1980. The voting results were: 78 in favor, 17 against, and 36 abstentions. See “United Nations General Assembly Resolutions, 1980,” in SIPRI Yearbook 1981 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1981), p. 402.

9 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 37/98 D, December 13, 1982. The voting results were: 86 in favour, 19 against and 33 abstentions. See “Resolutions,” in SIPRI Yearbook 1983 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1983), p. 585.

10 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 42/37, November 30, 1987. The Security Council endorsed this authority in Resolution 620, August 26, 1988.

11 See United Nations General Assembly, “Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons. Report of the Secretary General,” A/39/488, October 2, 1984.

12 Erik Millstone, “The Evolution of Risk Assessment Paradigms: In Theory and in Practice,” paper presented at Workshop on Paradigms of Risk Assessment and Uncertainty in Policy Research, Department of Sociology, University of California, San Diego, May 14–15, 2010, p. 7.

13 Ibid., p.7

14 United Nations General Assembly “Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons. Report of the Secretary General” A/44/561, October 4, 1989, p. 10.

15 Ibid., pp. 11–31.

16 Ibid., pp. 32–43.

17 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 45/57 C, December 4, 1990.

18 United Nations General Assembly, A/39/488, p. 32.

19 Ibid.

20 United Nations General Assembly, “Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons,” Report of the Secretary-General, UN document A/44/561, October 4, 1989, p. 30.

21 Jez Littlewood “Investigating Allegations of CBW Use: Reviving the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism,” Compliance Chronicles, No. 3 (2006), p. 6.

22 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 60/288, A/RES/60/288, September 20, 2006.

23 United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, “Secretary-General’s Mehanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons,” n.d., <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/>

24 Littlewood, “Investigating Allegations of CBW Use,” p. 19

25 Ibid., p. 6

26 See, for example. United Nations S/1995/1038, December 17, 1995; United Nations, S/1999/94, January 29, 1999.

27 See, for example, Raymond Zilinskas, “Cuban Allegations of Biological Warfare by the United States: Assessing the Evidence,” Critical Reviews in Microbiology, Vol. 25, No. 3 (1999), pp. 173–227.

28 See Article 9, “Investigations in Protocol to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction,” BWC/AD HOC GROUP/CRP.8, May 30, 2001.

29 See, for example, Amy Smithson and Leslie-Anne Levy, Ataxia: The Chemical and Biological Terrorism Threat and the US Response (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 2000).

30 See Jeanne Guillemin, American Anthrax (New York: Henry Holt, 2011).

31 See UN Terrorism Report S/2019/570, July 15, 2019, pp. 13, 22.

32 “Secretary-General’s Mehanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons,” Appendix I, <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/appendices/appendix-i/>.

33 “Secretary-General’s Mehanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons,” Appendix IV, <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/appendices/appendix-iv/>.

34 “Secretary-General’s Mehanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons,” Appendix VII, <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/appendices/appendix-vii/>, Appendix IX, <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/appendices/appendix-ix/>.

35 See Appendix C to the SGM, “Report of Investigation Activities,” August 8, 2019, <www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/secretary-general-mechanism/appendices>.

36 Ibid.

37 Mary Gergen and Kenneth Gergen, Playing with Purpose: Adventures in Performative Social Science (New York: Routledge, 2016), p. 11.

38 Brian Roberts “Performative Social Science: A Consideration of Skills, Purpose and Context” Historical Social Research, Vol. 34, No. 1 (2009), p. 307

39 An important lesson from the investigations into chemical-weapons use conducted by the UN and OPCW is that the public is also an important audience and should not be overlooked. A Counter-Terrorosm Implementaton Task Force WMD [Weapons-of-Mass-Destruction] Working Group tabletop exercise conducted in 2017 noted that “informing the media and the public will be critical for mission success,” as “a large scale international response will receive a lot of media attention … It is therefore of utmost importance that international organisations speak with one voice, are perceived as open and truthful by the public and release as much factual information as the situation permits.” However, it is acknowledged that the SGM report’s primary audience resides in the policy domain. See Stefan Mogl, “Table Top Exercise Evaluation Report,” in United Nations Office of Counterterrorism, Ensuring Effective Interagency Interoperability and Coordinated Communication in Case of Chemical and/or Biological Attacks (New York, 2017), p. 59

40 Robert de Beaugrande, New Foundations for a Science of Text and Discourse: Cognition, Communication, and the Freedom of Access to Knowledge and Society (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1997), p. 10

41 Davide Nicolini, Jeanne Mengis, and Jacky Swan, “Understanding the Role of Objects in Cross- Disciplinary Collaboration,” Organization Science, Vol. 23, No. 3 (2012), p. 614.

42 See Caroline A. Bartel and Rachel Garud, “Narrative Knowledge in Action: Adaptive Abduction as a Mechanism for Knowledge Creation and Exchange in Organizations,” in Mark Easterby-Smith and Marjorie A. Lyles, eds., Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 324–42; Richard J. Boland and Ramkrishnan V. Tenkasi, “Perspective Making and Perspective Taking in Communities of Knowing” Organization Science, Vol. 6, No. 4 (1995), pp. 350–72.

43 Arthur Graesser and Victor Ottati “Why Stories? Some Evidence, Questions, and Challenges,” in Robert Wyer, ed., Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story Advances in Social Cognition, Vol. 8 (New York: Psychology Press, 2014) pp. 121–33.

44 As Brown notes, “authority is not a property of texts per se, but a characteristic attributed to the texts by their readers.” Andrew Brown, “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report,” Organization Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1 (2004), pp. 95–112.

45 “Report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic on the Alleged Use of Chemical Weapons in the Ghouta Area of Damascus on 21 August 2013,” September 16, 2013, A/67/997–S/2013/553; “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic Final Report,” December 13, 2013, A/68/663–S/2013/735.

46 Second UNSGM Designated Laboratories Workshop Report, Spiez, Switzerland, June 22–24 2016, pp. 15

47 Ralf Trapp, “Lesson Learned from the OPCW Mission in Syria,” submitted to director-general of the Technical Secretariat of the OPCW, December 16, 2015, p. 13

48 Brown, “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report.”

49 “Report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic on the Alleged Use of Chemical Weapons in the Ghouta Area of Damascus on 21 August 2013.”

50 Vladimir V Putin, “A Plea for Caution from Russia,” New York Times, September 12, 2013, p. A31.

51 “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic Final Report,” para. 40.

52 Ibid., Appendix 1.

53 Ibid., pp. 6–8.

54 Ibid., para. 27–39.

55 Brown, “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report,” p. 96.

56 “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic Final Report,” para. 32.

57 Brown, “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report,” p. 100.

58 “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic Final Report,” paras. 49–51.

59 Ibid., paras. 86–87.

60 Ibid., Appendix 2.

61 Ibid.

62 Nicolini et al., “Understanding the Role of Objects in Cross- Disciplinary Collaboration.”

63 United Nations Office for Disarmament, “The Secretary-General’s Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical, Bacteriological (Biological) or Toxin Weapons: A Lessons-Learned Exercise for the Untied Nations Mission in the Syrian Arab Republic, 2015,” p. 7.

64 Brown, “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report.” For more on sensemaking and its role in reporting, see also Andrew Brown, “Making Sense of Inquiry Sensemaking,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (2000), pp. 45–75.

65 Revill, “Compliance Revisited,” p. 27.