ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition (LCHC) as a living, distributed bio-geography—that is, as the diversity of ways in which the lab exists today in and through research-practice work and experiences across multiple locations and generations of scholars. Taking a genetic perspective, we ground our discussion in two moments in the history of LCHC, embodied in two international meetings that took place in San Diego, the institutional home of LCHC —one in 2003 and the other, part of Re-generating CHAT project, in 2019. Taking as our point of departure the empty room depicted in Section 6 of LCHC’s Polyphonic Autobiography, “The Future,” we examine these two meetings as two moments where that metaphorical empty room is enlivened and populated. In our discussion, we identify LCHC’s progressive and critical orientation toward social justice through scholarly praxis, and discuss how this orientation evolves throughout changing circumstances and configurations. Most characteristic of LCHC’s particular way of life, we discuss a degree of dis/coordination in its organization, which creates imaginative opportunities—open gaps—between the diverse voices, ideas, and identities in its collaborative research-practice activities.

Introduction

The Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition (LCHC) is introduced in the very first lines of its Polyphonic Autobiography (LCHC PA) as a research organization. The autobiography narrates this organization’s “long story,” beginning with its “pre-history” in Section 1 and ending with Section 6 – deliberately left blank – titled “The Future” (see also, Vadeboncoeur, Citationthis issue). The Polyphonic Autobiography describes the sociocultural context of the laboratory’s inception, the emergence and evolution of the ideas and research topics that have kept it busy, and the intersecting trajectories of the people who animated and continue to animate those ideas and research-practice projects. LCHC is thus presented as a fluid, dynamic organization that evolves over time.

Not only is it fluid and evolving, but, as the articles in this collection testify, it also expands beyond institutional and geographical affiliations. That is, LCHC takes shape in and through research-practice work and the life trajectories of scholars in different geographic and (inter)disciplinary locations. In the autobiography, this decentralized organization of the lab is defined as “a distributed geography of research sites” (LCHC PA, Section 3, Chapter 7).

Inspired by this articulation, we explore LCHC in the present article as a living, distributed bio-geography – that is, as the diversity of ways in which the lab exists today across multiple locations and generations of scholars. We thus aim to contribute to the understanding of what sort of research organization LCHC is and, of how it lives – and outlives itself – in and through distributed, intersecting, but also diversifying biographies, individual and collective. In one way or another, all of the articles included in this special issue deal with this topic. Our contribution adds a testimonial “from the future,” so to speak, in the sense that it attempts to understand LCHC from the perspective of a collaborative project that, while owing its roots to LCHC, continues as we write the words on this page. The project is called “Re-generating Cultural Historical Theory: Building a critical science of learning for education in challenging times” (or Re-gen, for short, as many of its members refer to it).Footnote1

Founded upon several of the personal and institutional trajectories that were grounded in LCHC’s long history, Re-gen is one of the ways in which LCHC continues to exist as distributed bio-geography. Indeed, its important goal is to engage with colleagues across generations to ensure cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) both acknowledges its critical roots and continues to evolve in ways critically responsive to the sociohistorical context of today. As scholars whose professional and personal trajectories intersect with LCHC through the Re-gen project, understanding some of the dynamics and emergent practices that hold it together as a distributed bio-geography is a way of both understanding LCHC’s past and glimpsing its future.

Accordingly, and consistent with a genetic perspective (Vygotsky, Citation1997), we examine the developmental trajectory that connects LCHC to the Re-gen project in three sections. In the first section, we present a genetic approach for our analysis that conceives of organizations as defined by their purpose, or the collective, historical motive that moves them. In doing so, we identify four constitutive dimensions by which LCHC as an organization develops in and through concrete activity, and include evidence to describe: 1) the shifting sociohistorical backdrop of LCHC activity; 2) the themes, discourses, and narratives that are central in different phases of LCHC; 3) practical considerations in organizing the communication of LCHC; and 4) the intergenerational collaboration.

In the second section, we ground our analysis in two moments in the history of LCHC, and the broader historical contexts they represent in the lab’s trajectory, embodied in two international meetings at UC San Diego, the institutional home of LCHC: one in 2003 and the other, part of Re-gen, in 2019. Taking as our point of departure the empty room depicted in Section 6 of LCHC's Polyphonic Autobiography, “The Future,” we examine these two meetings as two moments where that metaphorical empty room is enlivened and populated. By attending to the trajectory of LCHC’s activity, we are interested in understanding its future possibilities and growth and what motivates and identifies it as a moving force.

In the third section, we identify LCHC’s progressive and critical orientation toward social justice and discuss how this orientation evolves throughout changing circumstances and configurations across the four dimensions listed above. Most characteristic of LCHC, we discuss a degree of dis/coordination in its organization, which creates imaginative opportunities – open gaps – between the diverse voices, ideas, and identities in its collaborative research-practice activities (Engeström, Citation2008; Pelaprat & Cole, Citation2011).

We end with a brief conclusion that highlights the imaginative, utopian nature of the project. Overcoming social injustice involves a continued and productive struggle to address cross-generational and cross-sectorial challenges and gaps, both within and outside LCHC’s collaborative effort. By attempting to overcome these challenges, LCHC continues to create ever renewed conditions for its own development, and for the development of an expanding field of research.

An inquiry into LCHC’s future: a genetic approach

Our approach to understand LCHC as a living, moving force that develops across biographies and geographies is in accordance with a genetic perspective (Vygotsky, Citation1997). By examining how LCHC’s constitutive dimensions manifest differently across different moments of the organization’s trajectory, we pursue a description that “asks about origination and disappearance, about reasons and conditions, and about all those real relations that are the basis of any phenomenon” (p. 69), and does not simply consider traits and external manifestations. Under the premise that Re-gen is one of the ways in which LCHC lives further, we examine how its constitutive dimensions manifest differently across different moments of LCHC’s history. To do so, we first identify a theoretical definition of organizations, and identify constitutive dimensions more generally. We then provide a description of the Re-gen project that will serve as empirical basis for part of the analyses.

Theoretical background

We take as point of departure a cultural-historical conceptualization of organization that posits purpose as its most defining aspect. We theorize purpose as historical motive or object of activity (Engeström, Citation2008; Leontiev, Citation1978), which allows us to move from a fortuitous, random, or unscientific account of why people may get along and do things together, to a social scientific one. The idea of historical motive allows us to better understand how collective and individual (personal) moments mutually intertwine in the development of cultures.

Furthermore, our argument is inspired by the notion of communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991) to examine the way in which LCHC purposeful organization is achieved by means of concrete activity that, in its material organization, creates the conditions for its own development. We direct attention to ways in which “the old and the new, the known and the unknown, the established and the hopeful, act out their differences and discover their commonalities, manifest their fear of one another, and come to terms with their need for one another” (p. 116).

To identify constitutive dimensions, we draw on research that has both informed and been generated by LCHC. The first dimension attends to the backdrop of shifting historical contexts against which the purpose of the activity of LCHC is formulated. Anyone connected to LCHC’s history and legacy is subjected to new contexts that raise the question of what kind of scholarship on human culture we wish to give continuity to – a statement particularly relevant today given a world in a deep crisis. In our analysis, we discuss how the historical conditions that motivated LCHC’s emergence have changed as socioecological crises and inequality have continued to grow, shaping today’s social, economic, and academic landscapes.

The second dimension attends to the themes, discourses, and narratives that emerge as scholars deal with and respond to those shifting historical contexts in their work. We will observe development within this dimension as we compare episodes of the lab’s history, discussing how emerging themes reflect and refract changes in the organization’s relation to its historical environment, especially by analyzing the organizational and communicative means in use.

The third dimension attends to the way in which collaboration is practically organized, refracting historical context into collaborative activity. As LCHC evolves and transforms with new configurations, its expansion across space and time has been supported by the early adoption and creative use of new communication technologies. Moreover, the desire to use frontline theoretical understandings of the organization of human activity has been a signature achievement of LCHC.

Lastly, the fourth dimension attends to intergenerational collaboration in the different moments of LCHC’s history. Every organization lives and outlives its members in and through intergenerational participation in the organization, more aptly referred to by Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) as apprenticeship in a community of practice, through which “the larger community of practitioners reproduces itself” (p. 16). Of course, this process is never one of transmission and assimilation of knowledge, so it may be more appropriate to call it “intergenerational co-participation,” as the very process of apprenticeship involves not only newcomers learning to become competent members, but the whole organization changing in and through its apprenticeship practices.

Importantly, these four dimensions are mutually constitutive, and hence interdependent.

Re-generating CHAT project

Central to our argument is that projects such as Re-gen can be considered as ways in which LCHC continues to evolve into new forms of research organization. Initiated by the MCA editorial team – of which we, the authors, are fresh members – and funded by the Spencer Foundation, the project began in late 2018 as a set of meetings and online collaborations. Scholars interested in the relations between mind, culture, and activity gathered to discuss and identify ways in which our scholarly work needed to be renewed to address the existential and political challenges facing our societies.Footnote2

The Re-gen research project is motivated by (a) a sense of dissatisfaction with how cultural-historical theory concepts are taken up in mainstream literature, where their critical and revolutionary edge tends to be “domesticated” and diluted into hegemonic forms of scholarly praxis; and (b) a sense of urgency that, in these times of rising right-wing nationalism and ecological crises, it is those critical and revolutionary dimensions that most need to be revised and strengthened. These two motivations already resonated in the prior publications of some Re-gen participants (e.g., Esmonde & Booker, Citation2017; Politics of Learning Writing Collective, Citation2017).

The goals of the project include (i) facilitating dialogue and sustained collaboration among cultural historical scholars from different generations and different applied domains to ensure development and renewal of the critical analytic lens; (ii) clarifying important synergies and differences between seemingly complementary critical approaches, with a focus on addressing social justice concerns; (iii) stimulating joint publications; and (iv) establishing long-term networks of collaboration based on innovative future projects, so as to ensure the continuity and sustainability of a critical, cultural-historical approach to equitable and sustainable education.

LCHC’s bio-geography, then and now: snapshots of a meeting room

“The Future” (Section 6 of LCHC PA) opens with an image of a typical academic meeting room (). Its tables and chairs form a square – an ordinary setup for conversation-based teaching – and there is a big screen in the room for instructional display and a smaller one for videoconferencing. There is nothing special about the room other than its placement under the LCHC PA heading “The Future.” From a semiotic perspective, it is possible to perceive the page as an invitation to join, an open space for us to take a seat and join in the dialogue (Vadeboncoeur, this issue).

Presumably, the room depicted in Section 6 of LCHC PA is one of the rooms at the University of California San Diego, which has hosted the lab since 1978. In the image, the room is empty. In real life, though, the room has often been populated, animated by activities and discussions, many of which have been connected to LCHC’s life. In this section, we look at two such occasions in the lab’s history, in which rooms that could have been this room bring us to the same place, UC San Diego, but (a) they are separated by 16 years in time; and (b) they extend beyond the building’s physical location by virtue of videoconferencing technology, embodying the interdisciplinary, international organization LCHC has been since its inception.

Next, we briefly describe each of these meetings with regard to their format, their sociohistorical contexts, participants, and focus themes. Building on the four dimensions identified in the previous section, the descriptions then serve as the empirical basis for a discussion to examine core features that characterize LCHC, then and now, as a distributed bio-geography, and go on to infer, via induction, the dynamics that characterize its movement toward a future.

The two episodes are selected for convenience, as the two meetings are video recorded and accessible for observation. They are organized in different formats and are not representative samples of any larger set of meetings. However, as moments of LCHC, they immanently express the lab’s modes of working, at least in two instances. In the discussion section, we foreground these empirical observations against a larger historical backdrop surmised from our reading of LCHC PA and our own firsthand experiences as part of Re-gen. The empirical snapshots presented here thus provide an illustrative basis for our ensuing discussion, which will be based on a broader analysis and understanding of LCHC’s trajectory.

Snapshot 1: a video conference on mediation, consciousness, and creativity

The first snapshot takes place in November 2003 and involves a videoconference hosted from UC San Diego (). The videoconference was arranged on the occasion of the International Vygotsky Conference in Moscow, which took place at the L.S. Vygotsky Psychology Institute, and was chaired by Elena Kravtsova, an exceptional colleague and friend to so many of us and whose recent passing is something we acknowledge only briefly here. Mike Cole, accompanied and supported by Belorussian graduate student Olga Kuchinskaya, leads the session with a conference presentation that lasts for about 45 minutes, after which the session turns into a discussion, involving exchanges with as well as within the group in Moscow, that lasts for another 45 minutes. The group in Moscow is composed of Russian and international scholars, many of whom have collaborative ties with LCHC.

Figure 2. The 2003 videoconference. LCHC in San Diego (left) and the L. S. Vygotsky Psychology Institute in Moscow (right).

Speaking in both English and Russian, Mike brings the concepts of mediation, consciousness, and creativity together around the idea of imagination, showing how it is implicated in all aspects of our perception of reality. He describes how restricting imagination to objects and situations we cannot perceive establishes a fraught binary of presence versus absence; how even the perception of stationary and present objects involves constant, involuntary – saccadic – movement of the eyes (Pelaprat & Cole, Citation2011). In fact, studies of visual perception show that we can understand all seeing, including the perception of color, as partially a consequence of discoordination between the perceiver and the object perceived. In his lecture, Mike argues for moving away from the term “representation,” which is concerned with re-presenting the world but not necessarily with how we actively engage in making it, so as to muddle and bridge the binary between perception and imagination. To capture the insight that “imagination is fundamental to experiencing the world in the here and now” (Pelaprat & Cole, Citation2011, p. 2), Mike reads Sonnet 4 in Book II of Sonnets to Orpheus, by Rainer Maria Rilke, in English translation, which describes the emergence of a unicorn. He then interprets the poem to illustrate his view of human imagination as constantly developing, adaptive, and involving the active coordination of intervals of time between dis/coordinated moments of perception. “That which is imagined needs to be reified and made real, and when made real, it reacts back on us as an instrument of our imagination,” Mike proposes in his talk (see Vadeboncoeur, this issue, for the text of the sonnet in English and German).

As the presentation concludes, Mike and Olga open the floor for discussion by framing the talk as an occasion to address the educational implications of these ideas. A discussion ensues in which both Russian and international scholars engage, raising questions about and commenting on the dialectical relationship between socio-material constraints and the goal of creative and progressive education.

Snapshot 2: a re-generating CHAT meeting

The second moment in the LCHC trajectory takes place after the publication of LCHC PA, when Section 6 – “The Future” – had already been left blank. It is a Re-generating CHAT meeting that took place in the seminar rooms of the Department of Communication at UC San Diego () on June 6–8, 2019. Even though in this article we focus on this second of two Re-gen project meetings, it is impossible to examine it without being reminded of the first meeting at UC Berkeley, which took place several months earlier in January 2019. The conversations in San Diego are both deliberately and intuitively shaped by participants’ experiences of the Berkeley sessions. They are also shaped by the fact that the Berkeley meeting ended with a new configuration based on what were called “affinity groups” – working groups that organized collaboration around themes, including the themes of play, learners’ voices, literature rhizome, consensus points, the Anthropocene, and utopian methodologies. While still nested within the larger community and intergroup communication, these groups have worked closely via e-mail lists and online meetings.

The first working day begins with the introduction of all 37 participants from four continents (South America, North America, Europe, and Australia) and eight countries (Australia, Canada, Colombia, Finland, Norway, Sweden, UK, USA), with 25 participants physically in the room and 12 taking part remotely via Zoom videoconferencing. After introductions, the meeting continues with a session titled “We, in the Anthropocene,” aimed at rethinking our practices and identity as a community of scholars. To address the current era of ecological crisis, we discuss the new forms of education necessary for future generations to grapple with the challenges ahead.

A youth activist from the Fridays for Future movement takes part in the session via Zoom while participating in a protest in front of the United Nations' headquarters in New York City. Directly addressing and posing questions to the other meeting participants, he talks about the activist movement and expresses his expectations and hopes with respect to policy makers and educators. After the discussion, the large group breaks out into smaller affinity groups, each reconsidering their internal conversations held prior to the meeting over e-mail and Zoom to address the question of how their work could be integrated into the topic of the Anthropocene.

This first day ends with a discussion of the communication tools and practices that would sustain the community’s collaboration. The session is chaired by the Communication Committee, one of two groups – the other being the Organizing Committee – that have been created for the project’s organization. The formation of a communication committee followed from the view, expressed by one of its members, that “technology and digital media continue to be seen as objects of critical inquiry rather than as a mediating tool for expanding our work or examining agency and social transformation that is the glue of collaboration.” One of the discussion topics in the session concerns the results of a survey that project participants had filled out regarding their experiences and desires surrounding the communication tools, practices, and platforms used.

The last day of the event begins with a session titled “Consensus? Points,” chaired by the affinity group of the same name. The goal of the session is to further articulate key CHAT narratives, metaphors, and concrete examples – ideas and implications that are “commonsense” to CHAT scholars – to help communicate them to policy makers as well as broader audiences of academic and practitioners who are not trained in CHAT. The topic had been initiated at the Berkeley meeting, and conversation surrounding it had been continued over e-mail since.

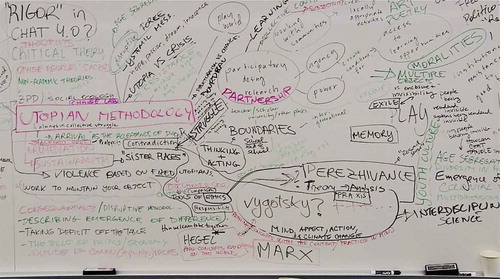

During the Berkeley meeting, a mind map had been created to capture the topics and connections that emerged in discussions (). Although not much attention was paid to it after the session (despite original design intentions), the mind map did reflect the chaotic and diverse number of themes that emerged, and reference is made to it during this last discussion at the San Diego meeting.

The ensuing “Consensus? Points” discussion revolves around two senses of the word “consensus”: First, there is trying to establish key principles that can be “taken for granted,” i.e., principles on which everyone might agree as part of the collective agenda, including in areas such as methods, theory, and immediately relevant public engagement. Second, there is trying to achieve agreement on basic premises of the project’s research, captured by questions such as “What are we all passionate about?” or “What drives us?”

An important follow-up question is raised that resonates with many participants: “Toward what ends are we articulating these consensus points?” During the ensuing discussion, some members suggest that what is missing from the mind map is a sense of collective subject and collective agency. At that juncture, two opposing tendencies enter into dialogue. Some participants wish to establish a collective movement toward social justice as a shared focus. Others point out that in order to achieve such collective subjectivity, first, all diverse voices within the group need to be heard – suggesting that some voices had not been heard – and; second, that it should be through ongoing collaboration that the participants would “learn from each other, and try to hear each other around, as opposed to determining that now, so that we are all moving to the same place in a way that might be normalizing and making for a singular way of thinking.”

The day ends with a discussion of future prospects of the project. First, the participants discuss the topic in two separate groups – an older generation group and a newer generation group – so as to provide more junior participants with a safer space in which to propose tentative ideas. This is followed by a reconvening of the groups for an intergenerational wrap-up discussion summarizing project achievements and desires going forward.

A genetic analytical sketch of LCHC as a distributed bio-geography

In this section, we develop insights that emerge when the two moments in LCHC’s history – past and present/future – are used to anchor a broader discussion characterizing LCHC as a purposeful entity and an unfolding and distributed bio-geography of research sites and experiences. Much as with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) method of double stimulation, the two meetings act for us as auxiliary stimuli, which we mobilize to address the problem of characterizing a dislocated, distributed, and shifting, yet unitary, research organization.

To organize our analysis, we structure the section to correspond to the four dimensions we identified in our overview, but consolidated under two main analytical concerns: one attending to the ways in which the lab has historically related to its historical context, including the themes, discourses, and narratives that have emerged from that relation; and the other, attending to the ways in which this relation and its thematic emphases have materialized in and through specific forms of (dis/coordinated) intergenerational and intersectional collaboration.

LCHC’s progressive and critical agenda in the wake of neocolonialism and in the crises of the Anthropocene

From a genetic as well as a cultural-historical perspective, there is no more primary definition of a living organism than that which describes its relation with its environment, specifically its purposeful relation or motive. It is out of and by reference to this ongoing relation that perceptual and conceptual differentiations emerge and characterize a definite form of life. Applying the same logic, the first feature that emerges when one considers the way in which LCHC has historically related to its sociocultural context or environment is its progressive and critical orientation – that is, an orientation toward challenging and changing existing societal forms, including forms of scholarly praxis and discourse, and doing so for social justice and the common good.

This orientation is visible in the two meetings presented above; each one, however, reflects distinctive qualities that relate to changes in sociohistorical context. By contrasting the two moments and their respective historical contexts, it is possible to see a shift: from a commitment in the earlier moment to deepening and expanding new theoretical (Vygotskian) ideas to address the challenges of inequality and social injustice through education, to a revived self-critique in the later moment, where the domestication of the earlier ideas comes to attention, and the urgency of renewing those ideas in a pressing context of global ecological and humanitarian crisis becomes a priority.

Expanding Vygotskian notions toward equitable educational design

Chapter 1 of LCHC PA, “A Pre-History,” discusses the sociohistorical and intellectual context in which the lab emerged as a research unit, describing how, “during the 1960s, several social trends converged to focus scholarly and social attention on the relationship between cultural experience and intellectual development.” It is referring here to the ideological and geopolitical struggles for global influence characteristic of the Cold War era, which, in the US, led to greater emphasis on STEM education and educational reform. This in turn converged with a growing international focus, in the West, of spreading and supporting “economic development” in the so-called Third World. It also converged with national efforts toward school desegregation and the erasing of poverty.

In this context, the recognition of intrinsic relations between human culture and human cognition and development – a staple LCHC concern – was emerging in American society, but in a way that was directly opposite to what would become the focus and motive of the lab in those early days. Ideological trends in politics, which were reflected in academia as well, were characterized by a deficit-oriented conceptualization of poverty, which, anchored by the idea of so-called “cultures of poverty,” argued that “growing up in conditions of poverty produces an experiential deficit (cultural deprivation) that in turn produces a shortcoming in psychological functioning” (LCHC PA, Chapter 2). The lab’s early work, which characterized its pre-history, grew as a response to precisely these cultural deficit ideas.

Not only did this work aim to problematize a thoroughly colonialist view of Western culture as the standard criterion against which to evaluate development, but it did so with an overt, activist, social justice orientation. LCHC PA describes the lab’s motivation succinctly: “The problematic was to better understand the relationships of culture and cognition in their historical and social contexts as a resource for addressing the very real problems of social inequality.” Thus, from its inception, LCHC was defined by two co-constitutive dimensions, which Thompson (Citation2020) summarizes as follows: On the one hand, there is a critical perspective “identifying the way that social scientists misunderstood the nature of the problem of social inequality.” On the other hand, building on these insights, LCHC strove “to identify interventions that would help ameliorate social inequality,” a characteristic most clearly epitomized in its work with Fifth Dimension on after-school programs (well documented by other articles throughout this issue).

Both these tendencies – of approaching hegemonic views of development critically and of implementing action- and transformation-oriented research – resonated with the Soviet psychological, Vygotskian ideas that the lab had helped to disseminate in the West. By the time of the 2003 meeting described in the first snapshot, there was already a robust history of relations between international scholars – including US and Russian scholars – who shared an interest in how Vygotskian ideas could help transform the conditions of human life. Mike Cole’s lecture at the 2003 meeting was an in-depth exploration of Vygotskian notions of imagination and cultural mediation as they related to understanding the nature of human perception and activity. The shared interest among meeting participants in the transformation of life conditions was especially visible in the discussion following Cole’s talk, in which the participants discussed means for organizing creative forms of education to reduce social inequalities. In other words, the discussion did not remain in the theoretical realm of cognitive definitions but quickly moved into issues of pedagogical design, which were a growing focus of scholarly debates at the time.Footnote3

Problematizing the domestication of theory: the pressing problem of discourses of white nationalism and a context of ecocide

In the second snapshot, which captures Re-gen efforts, Vygotskian theoretical concepts appear again as a starting point. There is a clear aim at continuing to expand upon them; yet there is a twist in the critical character of the expansion, in that Vygotskian notions appear here not only as a means, but also an object of reflexive critique and addressing social injustice concerns. As stated in the project’s webpages,

Today, CHAT is widely taken up, but its critical, transformational character is often “domesticated,” serving, rather than transforming established practices. This is problematic given pressing contemporary concerns, including the rise of nationalist, authoritarian, and/or racist movements that threaten the autonomy and democratic mission of education and of the human and the social sciences more generally. (https://re-generatingchat.com/)

This revisionist spirit guides the questions that motivate the reflection activities throughout the Re-gen meeting, with several concerns converging around not only the usefulness of CHAT concepts, but also their problematic nature in some of their original formulations. Some of the latter could be read as following a colonial logic (e.g., Bang, Citation2017), thereby becoming problematic to the group’s emancipative social justice intentions. There are also issues with the narrow ways in which some of the concepts are presented in Western mainstream literature (Roth & Jornet, Citation2017).

The sense of urgency in revising CHAT concepts, and the fact that a young leader from the Fridays for FutureFootnote4 movement is among the first participants to take the floor during the Re-gen meeting (via mobile phone connection, directly from his active participation in a protest event in front of New York’s UN headquarters) speak to the changing historical context. Between 2003 and June 2019, the dates of the two meetings described in the snapshots, a number of dire historical developments had given shape to a very different intersection of sociocultural forces from that which characterized LCHC’s birth. A Great Recession following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, growing inequalities across the globe, rapidly declining ecosystems, the 10 warmest climate years on record, and a surge in white nationalist and radical right-wing governments – all of which had taken place by the June 2019 meeting – stood in strong contrast to the so-called US boom of the golden years that preceded the 2003 meeting.

A central way in which emerging notions develop during the June 2019 meeting and throughout the Re-gen project more generally is by problematization of the anthropocentric and, to some extent, colonial views – perceivable today – of the original formulations of CHAT ideas. Some of these ideas had sprung up in prior publications (e.g., Bang, Citation2017) as calls to attend to the values and perspectives of indigenous cultures, especially as they related to wisdom in conceiving and cultivating human-nature relations. The question of how to foreground black, brown, and indigenous activism (e.g., in relation to climate change) and build scholarly cultures that support such visibility and activist leadership is raised as well at the June 2019 meeting.

Other novel themes of the June 2019 meeting concern the reconsideration of more classical notions, such as perezhivanie, in light of global crises and what these mean to human (and humanity’s) development, as elaborated – for example, – by Blunden (Citation2020). Finally, an important thematic thread that characterizes the collaboration at the Re-gen meeting is an insistence on bringing CHAT literature into dialogue with critical and often less well represented works relevant to its emancipating, decolonizing aims, such as Frantz Fanon’s theory (e.g., Nzinga, Citationthis issue).

Perhaps more important even than the shifting content of the theoretical ideas being discussed is the shift of an emerging self-awareness of the group in relation to itself as the discussing collective subject, and the issue of how different voices within the collective are or are not being heard. This is most clearly visible in our description of Snapshot 2, where an attempt is made to render cohesive the diversity of topics and ideas represented in the messy mind map () not by means of identifying a pre-given focus or goal, but by the collaborative, time-spanning work of generating an inclusive collective subject.

Connecting the two different moments of LCHC’s development and expansion across the diversifying, distributed geographies of scholarly engagement, therefore, is a constitutive feature: a purposeful critical and activist orientation toward change for social and ecological justice. But this constitutive feature itself evolves in mutually constitutive relation with a changing sociohistorical environment: one in which, despite years of scholarly discourse for and about education for social justice, the realities of people in societies around the globe – along with the world’s prospects of a livable Earth – are not getting better but, on the contrary, getting worse. In this context, the lab’s expansion over time into new forms of collaboration and intergenerational relations becomes the co-constitutive medium through which certain opportunities emerge – opportunities for bringing new diversities of scholars and perspectives to bear upon and support CHAT-informed scholars’ critical revision of how they address societal issues through academic work.

A dis/coordinated, distributed organization: intergenerational, intersectional, and international collaboration in LCHC

Two additional dimensions crucial to understanding an organization’s life involve the way the organization lives across generations, locations and occasions through collaboration and communicative means. In order to characterize LCHC’s way of organizing collaboration across sites and generations, we turn to a concept presented at the 2003 meeting that we have previously mentioned and that has also been published in an article about imagination (Pelaprat & Cole, Citation2011): the realization that, in human perception, “constant discoordination with the world is a necessary, constitutive aspect of our perception of the world as individuals that behave in the world” (p. 400). This idea of discoordination, exemplified by the human eye’s saccadic movements, is advanced by Pelaprat and Cole to argue that imagination is inherent to perception. To form the simplest image, there is the need to compensate for what sense organs are unable to record by both imaginatively creating and filling a gap; or, in Bateson’s (Citation1972) parlance, to make a difference that makes a difference. Here, we use the dis/coordination form to emphasize the dialectical nature of the process, in which both the intention to achieve coordinated action and the possibility of literally achieving such a coordination co-exist as opposites within the same notion.

By way of analogy, we argue that, through the generation of a complex network of co-participation across sites and generations, the way in which LCHC reproduces itself toward its own imagined future is also characterized by a form of constant discoordination, in which the gaps that emerge – due to the impossibility of fully aligning the diversity of views, sensitivities, and intentions involved – also constitute the organizations’ moving force. More specifically, we identify two characteristic ways in which such dis/coordination is generative in the LCHC’s development: (i) through the increasing tensions and uncertainties that emerge as the organization expands and decenters into a more distributed, supra-institutional collective subject, which (ii) in turn involves an increasingly self-critical character in its intergenerational, intersectional relations.

Expanding distributed bio-geographies: from international networking across institutions to fluid knotworking toward a supra-institutional subject

The international, interdisciplinary breadth of LCHC is well documented in the LCHC PA, as well as in the articles of this issue, and is clearly visible in both moments examined in this article. The 2003 episode in particular is illustrative of the lab’s long-standing collaboration with colleagues from the former Soviet Union, which, when the collaboration began back in the 1960s, was a remarkable historical achievement, both because of the diplomatic implications of enabling dialogue across competing nations, and also because of the significant impact that Soviet psychology’s cultural-historical ideas have had on psychology and education in US and Western academic circles.

The physical and communicative format of the 2003 meeting displays its reliance on internet-based videoconferencing, which was probably much less commonly in use in academic settings then compared to the present time of the writing of this article. These arrangements testify to an established set of technology-supported LCHC practices that helped forge the type of international and interdisciplinary scholarship documented throughout this special issue. By appropriating existing and emerging forms of digitally mediated communication, the lab has built an international network of collaborations surrounding the shared goals and interests represented in this issue.

Contrasting this with Snapshot 2 helps to anchor a discussion of wider developments in this vein, particularly the increasingly distributed and diverse nature of the collaborations shaping the ongoing Re-gen project – the collaborations through which LCHC lives further. From the outset, there is the difference that Re-gen is a project initiated by multiple actors with diverse institutional affiliations from across the globe. While LCHC was always a place for the interdisciplinary, international exchange of ideas, its emergence and development were tied to institutional homes, first in New York and then in San Diego (as described in chapters 3 to 7). Re-gen does not belong to any single institution but rather depends upon a wider web of emerging connections across institutional affiliations. Its institutionalization is indeterminate, an open inquiry; so are its forms of scholarly practice. In the terminology advanced by Engeström (Citation2008), the emerging organization resembles much more the type of fluid knotworking that organizes around “runaway,” rapidly changing objects and “takes shape without rigid, predetermined rules or a fixed central authority” (p. 20).

Although both meetings were organized using similar technology (despite being 16 years apart!) and around a similar spirit of dialogue, they also present different moments in the development of LCHC’s collaboration practices. Academic meetings and conferences such as the one described in Snapshot 1 have been and remain key to the internationalization of collaboration in that they can be organized along more or less familiar scripts and expected routines of what such scholarly engagement should look like. Re-gen, which lacked a clear, familiar definition of the collective effort, created something unusual, an emergent new configuration prone to generating gaps that literally had to be filled up with imagination. The argument here is not, of course, that prior moments of LCHC’s development could not be characterized in this way. However, in Re-gen, the push for a decentered, distributed entity takes center stage and becomes the leading – most determining – activity of the organization.

Making a case in point are the attempts to experiment with collaborative methods described in Snapshot 2. The mind map of CHAT theories and methods, the product of a two-day scholarly effort, is left unexamined – against its design intentions – but nevertheless becomes instrumental to opening further opportunities for more long-term collaboration and for re-orienting the group’s attention toward the emergence of a collective subject. In the filling of these sort of gaps, which are created by the uncertainty of the collaborative grounds upon which the effort is built, (un)intended consequences are achieved that prove fundamental to the development of the distributed organization.

This distributed organization, which lacks an institutional locus but is nonetheless dependent on the institutional affiliations of diverse individual members with diverse degrees of investment in the organization’s functioning, poses an open question or inquiry: What sort of collaborative configurations can be functional when a rapidly changing societal context poses the need to not only generate renewed research foci but also create new ways of inclusive scholarship? The description of Snapshot 2 shows that actively coordinating among participants to find scholarly synergies and tensions makes evident that re-generating critical cultural-historical approaches to human development calls for stepping back to address the issue not as an imagined outcome of the project, but as “a collaborative engagement – utopian methodology – in the here and now,” as one of the participants judiciously remarked during the Berkeley meeting.

An increasingly self-critical, intergenerational dialogue

Actively engaging and providing career opportunities for younger, junior scholars has been characteristic of the way LCHC has developed as a research organization over time. This is reflected, for example, in the fact that several of the authors in this special issue have at some point, in one form or another, been junior members of the lab, with several of these papers involving co-authorship between senior and junior scholars. Snapshot 1 presents only some of the features characteristic of this organization. Given the conference format, Mike, as the director of LCHC, becomes the central figure of the meeting, delivering a lecture and orchestrating the polyphonic engagement of different voices. He does so, however, accompanied by one of the lab’s PhD students, who occasionally contributes to the collective discussion and whose presence becomes key in several respects, which Mike acknowledges at different moments. Such forms of participation often lead to joint publications where junior scholars take the lead, such as the paper published by Pelaprat and Cole (Citation2011) based on some of the ideas discussed in the 2003 meeting.

As LCHC moves on to live into new distributed geographies, however, previously existing intergenerational challengesFootnote5 acquire new dimensions on a new historical stage. At a glance, comparing intergenerational involvement by observing how intergenerational interactions unfold in the two meetings discussed here might appear to illustrate the distinctive nature of intergenerational collaboration in the Re-gen meeting in San Diego, which was deliberately designed to disrupt conventional academic scripts. The opening of the Re-gen meeting, which was led by two junior scholars and featured the voice of a young climate activist, is illustrative in this regard.

Yet, as is certainly true to any organizational development, such transitions into more decentered and intergenerational modes of leadership do not occur without struggle. The Re-generating CHAT project made evident that intergenerational dynamics were embedded within intersectional dynamics of national, gender, ethnic, and class identities. Although the Re-gen meeting in San Diego is organized and led by two early-career scholars of different national, ethnic, gender, and class origins, overcoming the problem of hierarchical structures within the community to create opportunities for socially just intergenerational and interethnic dialogue is not resolved by a simple act of swapping leadership responsibilities for several months.

As is evidenced in written feedback collected from participants after the meeting in San Diego, many junior scholars reported in their feedback that they found it challenging to overcome the power structures attributed to generational issues because their initiatives were at times usurped or simply shut down – and this happening more often than when activities were led or organized by more senior members. This is a more general challenge in academia that is also reflected in the collaborative project, even as it is taken up as the focus of the activities. As one of the junior scholars points out, the way in which this intergenerational challenge is taken up tends to circumscribe the understanding of what constitutes “having a voice” along generationally oriented categories such as “junior,” “mid-career,” “senior,” failing to account for intersectionality and diverse social identities as the baseline of Re-generating CHAT’s efforts. From this feedback and later discussions, a need has become apparent to consider how these intergenerational barriers intersect with other layers of exclusion that junior colleagues of color face within the group and in academia more generally.

These later issues are not disconnected from the prior history of LCHC, where early attempts were made to engage in collaborative research with diverse scholars and practitioners (documented in chapter 2 of the LCHC PA). At the time, in order to collaborate with communities traditionally considered minorities, the lab needed to balance following the lead of the communities’ emancipative efforts with building approaches rooted in the lab’s own historical experience. Bridging these two parallel projects or intentions remains a challenge, one that is exacerbated when the projects expand into more widely distributed forms of collaboration. All in all, everyone in the Re-gen project, whether “junior” or “senior,” recognizes that it is easier to find alignments in collaborative tasks than to really acknowledge or meet each other and talk through differences, especially as differences show up in the moment – surprisingly, violently, unseen, or as anticipated.

Conclusion: utopia, struggle, dis/coordination, and future

In this paper, we examine the living history of LCHC by conceptualizing it as a set of distributed bio-geographies that organize around a common purpose or motive, which determines the lab as a historically evolving entity. Taking a CHAT-informed genetic perspective, we identify four constitutive dimensions by which that historical motive materializes as concrete practice, generating the conditions for its own development. Looking for a case in which LCHC has outlived itself into new configurations, we consider how the Re-gen project – as the participants started to call it – could be understood as genetically connected to LCHC, and therefore as one way of expressing its future.

Through our analyses, we identify a progressive and critical orientation toward achieving social justice through academic work as the primary motive that binds people together in the intermeshing knotwork that is LCHC – the knotwork it is when it is understood as an expanding set of distributed bio-geographies. We further discuss, from the perspective of Re-gen as an anchoring case, how this motive has evolved through shifting sociohistorical contexts and shifting forms of intergenerational and intersectional organization. Taking inspiration from the ideas of discoordination and imagination developed by Pelaprat and Cole (Citation2011), we understand these shifting dynamics as the result of opportunities for imaginative work that emerge when gaps open between divergent intentions and histories. As four generations of scholars from different disciplinary and institutional backgrounds sit down to articulate a collective research agenda for critical CHAT studies, participants imaginatively engage in coordinating collective dialogue and practical tasks, moving through dis/coordinated moments. Such gaps open when attempts to coordinate (productively) fail, and when race, gender, and power dynamics become visible in the organization’s struggle to live further. The collaboration thus becomes an ongoing, sometimes disruptive, at other times adaptive, non-linear product of its own operation.

In our inquiry to unpack future possibilities of LCHC, we are inspired by Ernst Bloch’s (Citation1986) notion of cultural surplus, which refers to utopian elements featured in past cultural forms that cannot be reduced to the historical conditions of production of these cultural forms, but rather involve anticipation of and desire for transformed futures. From this perspective, LCHC is a utopian effort that connects the researchers involved with it to generate more relevant and just scholarship. It is a way, too, of generating subjectivities and forms of academic experience. As our analyses show, the activities of cultivating sensibilities and attending to intergenerational collegial relationships, identities, and tensions among scholars coming to CHAT, seem to be refracted – and avoidably bound – to the research themes, narratives, and practices these activities are re-generating, to their forms of communication, and to the sociohistorical contexts that shape these efforts and conversations.

Although we draw on Re-gen as a specific case, it is important to note that there are other ways in which LCHC continues to be vibrant on different planes and in different domains. One such case is Angela Booker’s Democracy Lab, community-based research project (funded with support from UC Links). Continuing LCHC’s ethos of developing a shared plan and project that engages faculty and students across disciplines at UCSD, LCHC is currently planning to update the letters in the lab’s name to Laboratory of Collective Human Communication (LCHC). This idea was motivated by a desire to connect LCHC to a new generation of graduate students, in order to bring Vygotsky studies closer to the types of cultural studies and communication studies conducted in the Communication Department at UCSD (A. Booker, personal communication, April 15, 2020)

While emphasizing the utopian spirit of the endeavors discussed, we also want to point to their material and organizational challenges, which we have found to be crucial for the development of productive cooperation. In a time in which global challenges such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbate white nationalist racism and inequity worldwide, scholarly responses such as Re-gen need to continuously renew their critical and self-critical discourse and orientation if they are to remain true to LCHC’s original purposes of scholarship for social justice and solidarity. Particularly through our analyses of the intergenerational and intersectional aspects of Re-gen, we have become aware of the importance of coming to terms with our own histories and privileges. We also need to be reflexive about our contributions and stakes in eco-social injustices if we are to further reduce gaps between theory and practice and between academic intentions and the realities of everyday life that we aim to transform.

Acknowledgments

The Re-generating CHAT project was supported by the Spencer Foundation. A special thanks to Jennifer Vadeboncoeur for her comments and advice, which helped us extraordinarily in the writing of this article. This manuscript is partly stimulated by the ongoing discussions and collaborative activities of a diverse group of scholars as part of the Re-generating CHAT research network, www.re-generatingchat.com. Re-gen members who have participated in the discussions forming the background of this article include Michael Bakal, Megan Bang, Bryce Becker, Joe Berry, Andy Blunden, Angela Booker, Sophina Choudry, Mike Cole, Maricela Correa-Chávez, Krista Cortes, Arturo Cortéz, Ola Erstad, Meg Escudé, Moisés Esteban-Guitart, Beth Ferholt, Shelley Goldman, Kris Gutiérrez, Sandra Jacobo, Robert Lecusay, Carol Lee, José Ramón Lizárraga, Lisette Lopez, Mara Mahmood, Ray McDermott, Luis Moll, Fernando Moreno, Kalonji Nzinga, Martin Packer, Anna Rainio, Edward Rivero, Wolff-Michael Roth, Jose Eduardo Sanchez Reyes, Barbara Rogoff, Jeremy Sawyer, Anna Stetsenko, David Swanson, Luca Tateo, Greg Thompson, Charles Underwood, Jennifer Vadeboncoeur, Karen Villegas, Shirin Vossoughi, Julian Williams, Helena Worthen, and Peng Yin.

Notes

1. To learn more about the project, visit www.re-generatingchat.com.

2. The authors of this article have played a central role in the organization and activity of the Re-generating CHAT project and are members of its Organizing Committee.

3. Design-based research, which was oriented toward the merging of theory and practice in education, had by 2003 been around for a decade and was in the process of becoming the most defining methodological asset of the learning sciences. A special issue on the topic was about to be published in the Journal of the Learning Sciences (Barab & Squire, Citation2004), and went on to be highly cited.

4. Fridays for Future is a global movement led by students and activists to demand action on the current climate crisis (https://fridaysforfuture.org/).

5. As members of the collective familiar with the informal, tacit history of LCHC, we are aware that issues of gender and race have emerged over time, as they have in many other academic institutions. Our focus on how such issues have become visible in Re-gen is not intended to underestimate or misrepresent any ways in which those issues may have emerged in the past; rather, it reflects our closer knowledge of Re-gen and the focus of our inquiry on present/futures.

References

- Bang, M. (2017). Towards an ethic of decolonial trans-ontologies in sociocultural theories of learning and development. In I. Esmonde & A. Booker (Eds.), Power and privilege in the learning sciences: Critical and sociocultural theories of learning (pp. 115–138). Taylor & Francis.

- Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago Press.

- Bloch, E. (1986). The principle of hope. Mit Press.

- Blunden, A. (2020, March). The coronavirus pandemic is a world perezhivanie. Cultural Praxis. http://culturalpraxis.net/wordpress1/2020/04/15/the-coronavirus-pandemic-is-a-world-perezhivanie/

- Engeström, Y. (2008). From teams to knots: Activity-theoretical studies of collaboration and learning at work. Cambridge University Press.

- Esmonde, I., & Booker, A. (Eds.). (2017). Power and privilege in the learning sciences: Critical and sociocultural theories of learning. Taylor & Francis.

- Gregory A. Thompson. (2020). Race in the LCHC autobiography: past, present, and future. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 27(2).

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Leontiev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Prentice Hall.

- Nzinga, K. (2020). Exploring Fanon’s psychopolitical project as a theory of learning. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 27, 2.

- Pelaprat, E., & Cole, M. (2011). “Minding the gap”: Imagination, creativity, and human cognition. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 45(4), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-011-9176-5

- Politics of Learning Writing Collective. (2017). The learning sciences in a new era of US nationalism. Cognition and Instruction, 35(2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2017.1282486

- Roth, W.-M., & Jornet, A. (2017). Understanding educational psychology: A late Vygotskian, Spinozist Approach. Springer.

- Vadeboncoeur, J. A. (2020). Inviting social futures, imagining unicorns: A commentary on The story of LCHC: A polyphonic autobiography. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 27(2).

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (Vol. 4). Plenum.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Harvard University Press.