Abstract

Most Russians applaud the official narrative that Russia has reemerged as a great power. Yet they increasingly disagree with the assertion of the Kremlin that the United States is a looming external danger and a subversive force in Russian domestic politics. In line with these opinions, many Russians balk at the costs of confrontation with the West, demonstrating the initially limited and now waning political significance of the “Crimea euphoria” (or “Crimea effect”) and “rally ‘round the flag” phenomena. Russian elites often differ from the general public in their stronger backing for a more assertive foreign posture. Nevertheless, such preferences are frequently moderated by the apprehension that Russia will neglect domestic modernization indefinitely if its foreign policy is confrontational.

INTRODUCTIONFootnote1

With the persistence of strained relations between Russia and the United States, observers often fear the advent of a new Cold War. While the determinants and goals of Russia’s foreign policy toward the West and particularly the United States are subject to debate, experts often assume that Russian society will fully support the Kremlin in a protracted confrontation. Some Western analysts offer the provocative argument that Russia’s mass publics and elites hold “entrenched revanchist” views about the American-led West which will ensure the survival of Russian hostility toward the United States after Vladimir Putin has left the political stage.Footnote2 Yet surveys of mass and elite opinion and other materials point to a more complex assessment: that most of Russia’s general public as well as broad segments of its elites are concerned over the costs of confrontation with the West and want the government to focus on social and economic problems at home.

Most Russians applaud the official narrative that Russia has reemerged as a great power under Vladimir Putin, particularly with the annexation of Crimea, and also agree with the claims of the Russian state that America is an unfriendly power. Yet they increasingly disagree with the assertions of the Kremlin that the United States is a looming external danger and a subversive force in Russian domestic politics. In line with these opinions, many Russians are unwilling to bear the economic burden of an escalating confrontation with the West, demonstrating the limited political significance of the “Crimea euphoria” (or “Crimea effect”) produced by the annexation as well as the “rally ‘round the flag” phenomenon generated by ensuing tensions with the West.

The “Crimea effect” strengthened Putin’s authority by some measures but was less successful in providing durable support for Russia’s socioeconomic and political institutions and policies. Belief among Russians that the country was headed in the right direction increased from 40% in November 2013 to 64% in August 2014 (five months after the annexation of Crimea), but then dropped to 46% by June 2018.Footnote3 Even Putin’s approval numbers have suffered a significant decline, due in part to an unpopular government proposal in mid-2018 to raise the retirement age.Footnote4

Although a modest majority of Russians (54% in October 2018) still approve “on the whole” the Kremlin’s foreign policy,Footnote5 they are increasingly preoccupied with problems at home. Survey data reveal relatively weak approval among the public for a forceful external posture, including intervention in the “near abroad” to check American power or protect Russian speakers from perceived discrimination. Similarly, a large majority of Russians do not favor the creation of an imperium reminiscent of the Soviet Union or tsarist Russia.

Russia’s elites, unlike its mass publics, often advocate the projection of state power, including the creation of a sphere of influence in Eurasia which experts in the West often identify as a central goal of the Kremlin’s foreign policy.Footnote6 Nevertheless, many, perhaps most, of these elites (like mass society) want their government to emphasize domestic socioeconomic development, not the production and demonstration of hard power. Lev Gudkov, the Russian sociologist and director of the independent Levada Center, provided a similar assessment in mid-2018. Gudkov observed that the “Crimea effect,” particularly popular approval of Russia’s foreign policy as a reemerging great power, was waning in part because Russians increasingly believe that the Kremlin’s pursuit of its geopolitical goals comes “at the [social and economic] expense of the population.”Footnote7 This insight and related propositions are evaluated below through an examination of the attitudes of elites and mass publics on Russia’s relationship with the external environment since the annexation of Crimea.

FOREIGN POLICY AND RUSSIAN PUBLIC OPINION

Three important perspectives provide different explanations for Russia’s assertive, often confrontational, behavior toward the West, including the seizure of Crimea in 2014 and then covert support for insurrection in eastern Ukraine. Some Russia experts and scholars, including Timothy Garton Ash and Marcel van Herpen, maintain that Vladimir Putin is a neo-imperialist whose foreign policy reflects an expansionist impulse in Russian national identity.Footnote8 The Kremlin is said to foster and justify neo-imperialism by asserting the responsibility (and right), especially with the annexation of Crimea, to protect Russians living in the “near abroad” who are purportedly threatened by discriminatory policies.Footnote9 Agnia Grigas devotes particular attention to “Russian compatriot-driven reimperialization efforts.”Footnote10

From this standpoint, post-imperial nostalgia and currents of post-Soviet ressentimentFootnote11 are important drivers of Russia’s external behavior. Scholars suggest that Russia’s national identity is shaped by feelings of humiliation, injustice, and inferiority that arise from envious comparisons with the West, reflecting as well as strengthening an authoritarian, aggressive personality as described by Theodor Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School.Footnote12 By this account, a significant number of both elites and mass publics expect their leaders to restore the geopolitical equivalent of the Soviet Union.

Proponents of realist theory challenge this position, arguing that great power competition and conflict provide a more plausible explanation for Russian foreign policy. They trace the spiral of East–West tensions to an increasingly militarized struggle for regional hegemony between an advancing West led by the United States and a Russia that is at once defensive and resurgent.Footnote13 According to realists, tensions between Washington and Moscow had been building since the mid-1990s as NATO and the EU steadily encroached on the historical spheres of influence of tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union. Amid these challenges, made more acute by the Western policy of democracy promotion, Russia viewed the toppling of the pro-Russian government of Ukraine in 2014 as another “color revolution” purportedly engineered by the United States to undermine Russia’s regional position and perhaps its domestic political order. The Kremlin’s seizure of Crimea and support for insurrection in eastern Ukraine were efforts to claw back some of Russia’s diminished status and security in the region.

A third perspective, which is examined at length in this article, identifies domestic politics as the mainspring of the Kremlin’s official world view and external behavior. The Kremlin is described as an opportunistic actor that advances the narrative of Russia as a resurrected but beleaguered great power confronting external threats, particularly the United States. The intention is to generate patriotic fervor that bolsters Vladimir Putin’s domestic power and aggressive foreign policy while weakening his domestic adversaries and obscuring the socioeconomic costs of authoritarian misrule.Footnote14 An underlying assumption of this position is that the Kremlin successfully instills in Russian society the belief that a hostile West threatens a resurgent Russia. Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss credit pervasive Kremlin propaganda, particularly through state-controlled television, with shaping mass and elite consciousness to conform to official explanations for Russia’s conflict with the West.Footnote15 Russians are often described as “zombified” by the combative messaging of a neo-totalitarian state.Footnote16

While this third perspective stresses the ability of the Russian state to use “great power” and threat-based narratives to fundamentally shape the political attitudes of society, the other two approaches described above also diminish or neglect the agency of Russian society. This evaluation of Russian mass publics is flawed in important respects. Survey evidence and other materials indicate that Russian public opinion enjoys a significant measure of autonomy from manipulation by the state and that caution and restraint—and aversion to external confrontation—are important attributes of much of Russian opinion in its orientation toward foreign policy.

This assessment applies in particular to Russian attitudes at the mass level. In his important study about public opinion and foreign policy in post-Soviet Russia, William Zimmerman argues that Russians in the aggregate are both rational and prudent in their “policy responses concerning the use of force in general and with regard to their policy choices in reaction to NATO expansion.”Footnote17 To a significant extent, Zimmerman’s conclusions remain relevant as of this writing despite sweeping changes in Russian domestic politics and foreign policy since the publication of his book in 2002. Although the Russian public is reliant to a significant extent on state-controlled media, it is able to develop clear, if broad, preferences on foreign policy that are often at odds with those of the Kremlin.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 worked to bolster national self-esteem in Russia and its identity as a great power. It significantly lifted Putin’s approval ratings as did the powerful “rally ‘round the flag” effects from the subsequent confrontation with the West over Crimea, Russia’s support for the insurgency in eastern Ukraine, as well as other issues.Footnote18 However, public opinion surveys point to the limits as well as the decay of these sources of political authority. Russians see confrontation abroad and economic decline at home as threats to their core priorities: socioeconomic development and political stability. Their foreign policy preferences are shaped more by sensible concerns about domestic problems than by dreams of global power or nightmares of military attack by America.

Russian elites often differ from the general public in their stronger backing for a more assertive foreign posture. Nevertheless, such preferences among elites are frequently moderated by a preoccupation with socioeconomic problems at home and by the apprehension that Russia will neglect domestic modernization indefinitely if its foreign policy is confrontational. Like other Russians, many elites view the external environment as dangerous, a perception that is cultivated by the Kremlin to help produce patriotic “rally” sentiments. Yet this rally effect is often dulled by the widespread belief among both elites and masses that the greatest threats to Russia are rooted in its social and economic underdevelopment.

The Kremlin possesses sufficient authority as well as coercive power to ignore such preferences, but not without risk. As Henry Hale persuasively argues, public approval has been “consistently important” in keeping Putin in power. Although such support has allowed Putin to extend his control over the state and cripple opposition to his rule, his political survival still requires the maintenance of this approbation.Footnote19

Similarly, Dmitri Trenin observes that Putin and his ruling circle understand that Russia’s future, and their own, “depends mostly on how ordinary citizens feel … Russia is an autocracy, but it is an autocracy with the consent of the governed.”Footnote20 Trenin echoes Hans Morgenthau, who identified “national morale,” or the “degree of determination” with which society approves its government’s foreign policy, as a core element of state power. For Morgenthau, morale is expressed in the form of public opinion, “without whose support [i.e., consent] no government, democratic or autocratic, is able to pursue its policies with full effectiveness, if it is able to pursue them at all.”Footnote21 While most Russians currently back, if often cautiously, the Kremlin’s foreign policy, a costly and unpredictable escalation of conflict with the West in the context of Russian socioeconomic stagnation or decline could undermine “consent” with uncertain political consequences.

This argument is developed in two sections and a conclusion. The first part examines the attitudes of the general public in Russia on issues with implications for Russian foreign policy, including neo-imperialist sentiment; perceptions of external threat, particularly from the United States; and preferred definitions of a great power. The second section addresses these topics from the perspectives of segments of the Russian elite. The conclusion provides a summary and identifies important limits to the influence of elite and mass opinion on Russian foreign policy.

Empirical support for the argument draws on opinion surveys published by the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences and by leading Russian firms, including the Levada Center, the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM), the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM), and the Eurasia Monitor (which employs VTsIOM and the firm ZIRKON to conduct their surveys). The Levada Center kindly provided data for select questions from their surveys administered in July 2015 and March 2017. Bashkirova and Partners, the Russian firm, also conducted a nationally representative survey of 1500 respondents in October 2016. Data on elite attitudes after the Crimea annexation are drawn from a number of sources, including Sharon Werning Rivera et al., The Russian Elite 2016 (an analysis of the latest wave of the long-term study Survey of Russian ElitesFootnote22); the 2015 survey by the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences; a report by the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (SVOP); and a study by the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) and the Center for Strategic Research (CSR).

WEAK PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR NEO-IMPERIALISM OR REGIONAL HEGEMONY

Observers of Russian politics often identify the annexation of Crimea in 2014 as a watershed event that enabled Vladimir Putin to forge a new “social contract” that employs a triumphant narrative of Russia as a resurgent great power blunting the malign influence of the United States. For Sergei Guriev: “Thanks largely to the government’s extensive control over information, Mr. Putin has rewritten the social contract in Russia. Long based on economic performance, it is now about geopolitical status. If economic pain is the price Russians have to pay so that Russia can stand up to the West, so be it.”Footnote23

According to this argument, the Kremlin’s assurances to society of Russia’s enhanced geopolitical status based on anti-Americanism, renewed military strength, greater international prominence, and opposition to Western liberalism and democracy have replaced earlier implicit promises that the regime would supply stability and economic growth if society provided political compliance. Russians are portrayed as accepting socioeconomic stagnation and autocratic rule in exchange for the recovery of Russia’s status as a great power able to defy the United States and extend its influence abroad.

From this viewpoint, the Kremlin is increasingly dependent on belligerent propaganda and external tension, perhaps including military confrontation, to maintain this important source of its political legitimacy and that of the siloviki, a key support group. The siloviki are influential elites from the different organizations (particularly the “power ministries”) that compose Russia’s security establishment. The Kremlin, the siloviki, and other like-minded elites construct and disseminate narratives of American hostility that authorize their political power and justify responses in kind. According to Andrei Kolesnikov: “The Kremlin’s permanent war footing has become the primary means for Russian elites to keep themselves in power … the Kremlin continues to stake its legitimacy on the conviction that military actions [to advance Russian interests and block U.S. encroachments] will stimulate broader public support.”Footnote24

To what extent has this threat-based, great power narrative been successful in shaping Russian public opinion about foreign policy and the external environment in the post-Crimea period? Has Russian society embraced a new “contract” based on its acceptance of domestic economic hardship and political regimentation in exchange for the expansion of Russian power and prestige? The evidence suggests that while most Russians are pleased and often inspired by the Kremlin’s story that Russia is a resurgent great power reclaiming its rightful place on the global stage,Footnote25 they view the external environment with caution and are wary of an aggressive foreign policy.

Contemporary attitudes about the Soviet Union help us understand how Russians perceive a possible return to forms of neo-imperialism or regional spheres of influence. Although opinion surveys show that Russians feel significant nostalgia for the Soviet state, the sources of this sentiment are complex. Russians often view the Soviet Union, particularly under Leonid Brezhnev, as a time of social cohesion and economic stability, with steady employment, adequate wages, and reasonable access to basic social services. Economic inequality and political corruption were seemingly held in check. Russians also recall that the Soviet Union enjoyed international prestige and leverage as one of only two superpowers.Footnote26

Private memories as well as official representations of the Soviet collapse, followed by the political instability, economic distress, and feelings of national humiliation of the Boris Yeltsin period (the 1990s) have shaped popular and elite evaluations of Putin as a leader who enabled Russia to rise “from its knees,” helping it recover socioeconomic and political stability as well as an uplifting national identity.Footnote27 According to a study by the Institute of Sociology, with the annexation of Crimea and other assertions of national power, Russians overcame the “syndrome of self-abasement” that had taken root in the post-Soviet 1990s.Footnote28 Yet the survival under Putin of significant socioeconomic adversity and inequality as well as widespread political corruption encourages many Russians to valorize the Soviet era as one of order and social justice—and to judge life under Putin as falling short of the idealized Soviet past.Footnote29

Despite such positive representations of the Soviet past, a survey by the Eurasia Monitor Agency in October 2016 found that no more than 7% of respondents in any age group believed that the Soviet Union in some form could “definitely” be resurrected.Footnote30 In another survey, also in late 2016, only 12% of the respondents felt that the Soviet Union should be restored.Footnote31 These pragmatic and normative stances suggest that the danger of “restorative” nostalgia, defined by Svetlana Boym as an individual’s strong desire to recreate the past, is relatively weak in Russia as to the revival of the Soviet empire in some form. Instead, the feelings of most Russians are in line with Boym’s more benign “reflective” nostalgia, which represents a depoliticized and personalized longing for a lost period.Footnote32 Russians may have nostalgia for the Soviet Union, but only a minority expect or want it to be restored.

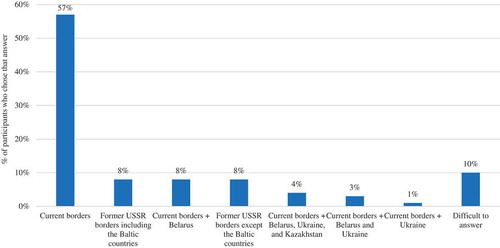

The effect of the incorporation of Crimea in 2014 on mass attitudes about Russia’s territorial identity provides other evidence of the weakening of expansionist sentiment in post-Soviet Russia. The greatest annual increase in the percentage of Russians who accept Russia’s existing borders rose to 57% from 32% of survey respondents and occurred during the year following the absorption of Crimea in March 2014.Footnote33 In 1998, near the end of Boris Yeltsin’s term in office and the eve of Putin’s accession to power, only 19% of survey respondents were content with Russia’s post-Soviet boundaries (see ).Footnote34

How did the events of 2014 help produce this outcome? For many Russians, the incorporation of Crimea was a cathartic event, seeming to confirm that Russia had finally recovered from the Soviet collapse, casting off the “syndrome of self-abasement.” The widespread belief that Russia now possessed the strength and self-confidence of a great power helped foster a more stable sense of national identity and, as a result, a greater acceptance of Russia’s interstate boundaries. At the same time, the ensuing conflict with the West demonstrated to Russians the heavy costs of the annexation and the likely burdens and dangers of further attempts to redraw Russia’s post-Soviet borders.

In part because the Kremlin’s military operation in Crimea was virtually bloodless and the subsequent annexation was widely perceived in Russia as free of coercion, Russians in 2014 strongly supported their government’s action. The fact that more than 65% of the population of Crimea self-identify as ethnic Russians and that the peninsula has significant ethnocultural, historical, and strategic value for Russia reinforced popular approval of the decision. The demonstration of Russian national power after more than two decades of strategic marginalization and international decline also prompted widespread approbation, akin to the subsequent pro-Kremlin “rally” response generated by the confrontation with the West over the annexation and Russia’s overt and clandestine support for separatist movements in eastern Ukraine.

Russians did embrace the idea of military confrontation and territorial expansion for a brief period after the seizure of Crimea. In a March 2014 Levada survey, 74% of respondents said they would support the Russian government in the event of armed conflict between Russian and Ukraine, now governed by a pro-Western regime. Less than a year later, this number fell to 44%, reflecting the growth of caution in Russian society despite the Kremlin’s claim that Ukraine had become a platform for future American aggression against Russia. Now 39% of respondents said they would either “definitely” or “probably” withhold support from the Kremlin in a direct clash with Ukraine, up from 13% eleven months earlier.Footnote35

Most Russians fear that regional conflict will likely produce unacceptable social and economic costs for themselves, for Russia as a whole, and for the communities in the “near abroad” with which Russia has long-standing historical, political, ethnocultural, economic, and personal ties. Millions of Russians have relatives, friends, colleagues, or acquaintances in Ukraine.Footnote36

Emotions in Russia over the annexation of Crimea also cooled. Although the great majority of Russians still support the incorporation of the peninsula, the passionate outpouring that had greeted the event subsided. When asked about their reaction to Russian policy toward Ukraine in March 2014, shortly after the annexation, 31% of respondents experienced a “feeling of [the] triumph of justice”; 34% felt greater “pride” in their country, while 19% simply expressed “joy.” But by October, these responses had declined to 10%, 18%, and 4%, respectively.Footnote37

Expansionist fervor waned over whether Russia should annex the provinces of eastern Ukraine under the control of pro-Russian rebels. In early 2014, at the time of the incorporation of Crimea, almost half of Russian respondents (48%) approved of the absorption of eastern Ukraine into Russia. Less than a year later this preference had dropped to 15%.Footnote38 As for whether Russia and Ukraine as a whole should unite in a single state—long a core demand of extreme ethnic and state nationalists in Russia—barely 7% of respondents supported that goal in September 2014, down from 28% in March of that year.Footnote39 By 2017, Russian society was split over whether Russia should even publicly approve the rebellion of the pro-Russian eastern provinces of Ukraine. According to one survey in April 2017, 41% of respondents believed that Russia should support the self-proclaimed DNR and LNR governments in eastern Ukraine; 5% thought that Russia should back the government in Kiev; and 37% believed that Moscow should remain neutral.Footnote40

The backdrop to these opinions was growing ambivalence about (or disinterest in) the fate of eastern Ukraine: In July 2018 only 18% of respondents acknowledged following events in eastern Ukraine (Donbas) on a regular basis, while 39% described themselves as minimally attentive. It is notable that 41% expressed no interest at all (64% of Russians between 18 and 30; 61% of younger Russians with higher education). Approval of the leadership of the breakaway Donetsk and Lugansk “people’s republics” has also declined significantly in the years since Crimea.Footnote41 Given these trends in public opinion, the Kremlin was motivated to mask its military support for pro-Russian insurgents in eastern Ukraine as much by a lack of strong domestic approval as by a desire to avoid Western condemnation and retaliation.

A question in the March 2017 Levada survey focused on an issue that the Kremlin had employed, among others, to justify the annexation of Crimea in 2014: Should Moscow protect Russian speakers in the countries of the “near abroad” (other than Ukraine) if they experienced serious discrimination? Alarmed by Russian behavior in Ukraine and the Baltic region, the governments of Lithuania and particularly Latvia and Estonia fear that the Kremlin will engage in hybrid warfare against them. A particular concern of these states is that Russia will condemn their alleged mistreatment of Russian minorities in order to mobilize support, in Russia and its diaspora in the “near abroad,” for asymmetric forms of aggression.

The survey question asked: “If the rights of ethnic Russians in neighboring countries (apart from Ukraine) are seriously violated, what should Russia do?” 35.8% selected the response that Russia should work toward a peaceful settlement of the problem, while 29.8% believed that Russia should not become involved in such disputes. 28.1% of the respondents felt that “all means” (including military force) should be used to protect Russian speakers who might be mistreated in the region.

That each of the three possible responses garnered roughly equivalent levels of support underscores the divisions within Russian society on this central issue—and the domestic political risk for the Kremlin in fomenting aggression of the sort feared by the Baltic states. It is noteworthy that the villages, towns, and small cities in Russia’s “heartland” that the Kremlin moved to activate as conservative counterweights after the political protests in 2011 and 2012 exhibited only modest levels of approval for the “right to protect” Russians in border countries. These population centers were slightly above or below the national average of 29.8% in advocating non-intervention. Respondents in Moscow were least willing to approve direct involvement by Russia in ethno-nationalist disputes. 41.2% of the Muscovites felt that intervention would be an unjustified intrusion into the “internal affairs of other countries.” This number marked a 22 percentage point increase over prior Levada survey results (July 2015) when only 19% of Muscovites provided that response.

Russians express even greater reluctance to intervene in the “near abroad” if survey questions do not address the thorny issue of the Russian diaspora. In terms of broad regional ambitions, most Russians do not advocate the emergence of their country as a post-Soviet hegemon. Only 6% of respondents in a January 2017 Levada survey “definitely” agreed with the statement that Russia should keep the former Soviet republics “under its control” by any means necessary, 19% “mostly” agreed, and 65% of respondents “definitely” or “mostly” disagreed (29% and 36%, respectively).Footnote42 In October 2016, a survey by the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences also found respondents opposed to Russia becoming “the leader of post-Soviet space”: Only 8% supported this role for their country.Footnote43

Beyond the “near abroad,” mass publics are hesitant about Russia extending its military footprint to advance its geopolitical position. A Pew survey in early 2017 that addressed Russian military involvement in Syria found that most respondents believed that “limiting civilian casualties” and “fighting terrorist groups” should be the top priorities for Russian forces. Only 25% of respondents felt that “ensuring Assad stays in power” (serving as a regional ally for Russia) was most important.Footnote44 In a Levada poll in August 2017, 49% of participants selected the response: “Russia must end its military operations in Syria,” while 30% supported the continuation of Russia’s military presence.Footnote45 Reflecting the Kremlin’s sensitivity to public opinion, and with echoes of its careful behavior in eastern Ukraine, casualty aversion has influenced Russia’s military operations in Syria to an important extent.Footnote46

THE POLITICAL LIMITATIONS OF ANTI-AMERICAN AND GREAT POWER NARRATIVES: MEASURING THREAT PERCEPTION

Threat perception is an important determinant of mass attitudes on whether Russia should expand its regional influence as well as its hard power. For The Economist, the Kremlin’s best hope for fulfilling its ambitious program for a military build-up is “persuading citizens to tighten their belts for the sake of a nation that supposedly faces a perpetual American peril.”Footnote47

Has this political strategy been successful? Drawing on their surveys of public opinion in Russia, Theodore Gerber and Jane Zavisca demonstrate that most Russians have adopted anti-Americanism.Footnote48 Other sources confirm their assessment: A recent Levada poll found that a large majority of Russians believe that Western, particularly American, criticism of the incorporation of Crimea is unfounded and represents an attempt to weaken their country.Footnote49 In the years before Crimea, the overwhelming power of America as well as U.S. foreign policy missteps and blunders like the invasion of Iraq helped instill in Russians resentment and sometimes fear of the United States.Footnote50 At the same time, the Kremlin had long fueled such attitudes, having made anti-Americanism a core component of its makeshift ideology for well over a decade.Footnote51

Despite the Kremlin’s identification of the United States as a serious threat and the existence of widespread anti-Americanism in Russian society, most Russians do not yet believe they face a “perpetual American peril.” Although the crisis over Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014 produced among Russians a significant increase in the perception of external military threats, mass publics and elites in general remained more preoccupied with domestic concerns.Footnote52

The March 2017 Levada survey, the October 2016 Bashkirova survey, and other polling data help measure threat perception in Russia as well as levels of societal support for greater military spending and an aggressive foreign policy. While the data confirm that most Russians hold negative opinions of the United States, the intensity and political significance of these attitudes should not be overstated; Russian anti-Americanism evokes feelings of dislike and apprehension rather than those of fear and alarm, with correspondingly different (more moderate) effects on beliefs, attitudes, and behavior.

If Russians did perceive an imminent and serious threat from abroad, intergroup emotions theoryFootnote53 and other models of group behavior, such as predatory imminence theory,Footnote54 would predict widespread expressions of collective anger at the menacing outgroup (the West, particularly the United States) as well as a strong desire to resist or inflict harm (for example, one would expect strong public backing for increased military spending; widespread pressure that Russia directly confront NATO; and perhaps advocacy for the annexation of eastern Ukraine and other controls over post-Soviet space as defensive buffers). The surveys under review point to the limited appeal of such responses among mass publics in Russia despite anti-American sentiments.

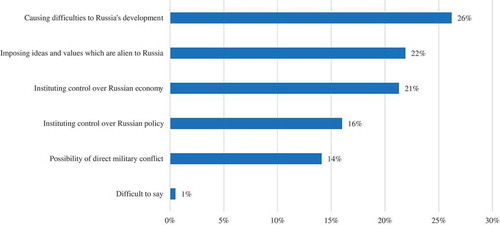

In a question from the March 2017 Levada survey, respondents were asked whether the United States currently poses a threat to Russia. 12.4% responded “definitely no” and 33.5% responded “more likely no than yes.” “Definitely yes” garnered 13.9% of responses, while 31.1% of respondents chose “more likely yes than no.” When the second group (which perceived a U.S. threat) was asked to identify all types of threat that applied, the “possibility of a [U.S.] military invasion or incursion” was selected by only 14.1% of respondents. Respondents regarded the peril of a military attack, presumably viewed as the worst of possible dangers, as the least likely of major threats (see ).

FIGURE 2 What kind of threat does the United States currently pose to Russia? Choose all that apply (for respondents who view the United States as a threat) (Levada, March 2017).

It is notable that the American threat most often selected by the respondents—“causing difficulties to Russia’s development”—reflects perceptions of the vulnerabilities of Russia’s economy, not its defensive capacity. So too does the third-ranked selection: the threat of America “instituting control over the Russian economy.” Other polling data suggest that Russians believe that both of these nonmilitary threats are best addressed through domestic socioeconomic reform, including effective controls over political corruption, limits on military spending, and greater investments in human capital.

The October 2016 survey by Bashkirova and Partners underscores that most Russians are not preoccupied with threats from the United States. It employed a five-point scale to determine how respondents perceive potential dangers to Russia, identifying 1 as the “absence of threat” and 5 as the “greatest danger” (the interior scale numbers were not labeled).Footnote55 Respondents were asked to measure the severity of seven possible threats, evaluating each according to the five points of the scale. Results showed that 9.9% of the respondents felt that the growth of American military power posed a “greatest danger” to Russia, while almost twice as many perceived no threat from that quarter. As for the possible threat to Russia of a “color revolution,” just under 8% of respondents saw Western-inspired political unrest in Russia as a “greatest danger,” while almost 24% perceived no danger at all. At the same time, 19% of respondents found an “information war” of the West against Russia as a “greatest danger,” while only 8.5% did not consider it to be a threat.

The remaining four dangers, which did not relate to threats from the United States or the West, were terrorism; the inability to solve domestic problems; interethnic conflict in Russia; and conflict between Russia and members of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States. Almost 29% (28.7%) of respondents selected terrorism as an “utmost threat,” the highest percentage among the seven listed threats. Further, 12.8% of respondents chose domestic problems, 9.3% selected interethnic conflict, and 6.9% identified conflict between Russia and its post-Soviet neighbors in the CIS as an “utmost threat.”

Other polling data confirm that most Russians have a moderate level of threat perception regarding the West. In the months after the Maidan Revolution of 2014, most Russians accepted the Kremlin’s explanation that Ukraine was moving closer to the American-led West and away from Russia because the new Ukrainian leadership was a “marionette” in the hands of the United States and Western Europe.Footnote56 Despite this negative assessment, a majority of Russians (58%) in a September 2014 Levada poll thought that whether or not Ukraine signed an Association Agreement with the EU (the issue which helped spark the Maidan demonstrations) was the “internal affair” of that country.Footnote57

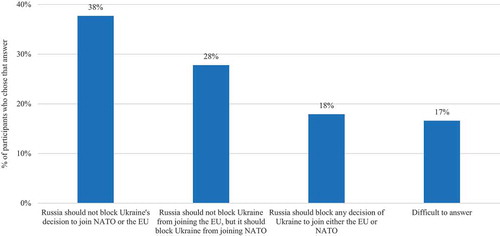

A question in the March 2017 Levada survey also probed how Russians would react to Ukraine’s possible acceptance of an invitation to join western political, economic, and security institutions. Overall, 37.7% of respondents thought that Russia should allow Ukraine to join either the European Union or NATO despite that country’s strong historical, cultural, socioeconomic, and strategic importance to Russia. Close to 48% of Muscovites supported this position, as did 37% of respondents from Russia’s villages and towns. Opposition to Ukraine’s entry into NATO, but not the EU, was expressed by 27.8% of survey participants. Almost 18% of respondents felt that Russia should “block any decision by Ukraine to join either the EU or NATO” ().

FIGURE 3 If Ukraine accepted an invitation to join NATO or the EU, should Russia block its decision? (Levada, March 2017).

Surveys on attitudes toward Ukraine reveal an important distinction in how Russians evaluate possible external threats: A majority is less troubled by the risk of foreign attack and more concerned about Russia being drawn into a conflict in a bordering country like Ukraine. Despite significant public sympathy for the insurgency in eastern Ukraine, only 13% of respondents in a late 2014 Levada survey (at the height of patriotic and expansionist enthusiasm in Russia) would approve a son joining the pro-Russia militias.Footnote58 Just 3% of respondents in a February 2015 survey would “definitely” (22% would “probably”) support the introduction of Russian troops into the conflict.Footnote59 Another survey by Levada in October 2014 found that a majority approved the efforts of independent Russian NGOs to compile lists of active duty soldiers of the Russian Army killed or wounded in the Kremlin’s clandestine war in eastern Ukraine.Footnote60

This aversion to entanglement in Ukraine was undiminished by the “Crimean effect” or by the widespread belief, confirmed in surveys, that the Kremlin’s policy toward Ukraine was intended to defend Russia’s “military-strategic and geopolitical interests” and the prevention of NATO expansion.Footnote61 In another indication of wariness, only a minority of Russians in surveys thought the Kremlin should balance against Western influence in Eurasia by increasing Russia’s own power in post-Soviet space, particularly over the countries of the CIS, the Russian-sponsored security and economic organization.Footnote62 These cautious, inward-looking preferences have persisted over time.

THE LIMITS OF “PRACTICAL PATRIOTISM”: EXPLAINING TEPID SUPPORT FOR HARD POWER AND AN AGGRESSIVE FOREIGN POLICY

Why do the Kremlin’s threat-based and great power narratives often fail to resonate in Russian society? The well-known hypothesis that external threat often strengthens political cohesion and weakens dissent requires qualification. As the data above suggest, threat should be viewed as a continuous variable in which individuals perceive different gradations or progressions of peril. Perceptions of external danger must reach a certain threshold before beliefs and behaviors that support political conformity begin to emerge. Whether this threshold is attained depends on a number of factors, including the character of the threat as well as the mobilizational capacity of the state and the coherence and intensity of its messaging. Other intervening variables, such as the material calculus of individuals, are situated at the societal level and shape an individual’s evaluation of the nature and degree of the external threat.

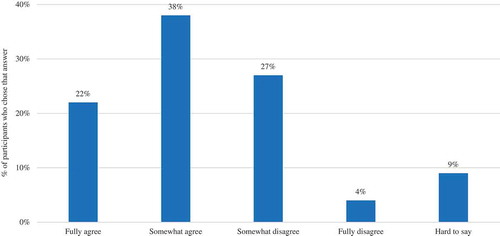

In the case of Russia after Crimea, two intertwined variables are particularly important: the perceived cost of preparing for and engaging in external conflict and the increase in societal autonomy from the messaging of the state. In conditions of socioeconomic decline and uncertainty, most Russians rationally calculate the costs of militarization and external confrontation. They fear that a significant rise in military spending and escalating clashes with the West will bring greater personal and collective distress. Economic concerns are substantial. After a noteworthy increase during 2000–2007, the level of personal wealth for most Russians has stagnated or declined, a problem predating Western sanctions and the steep drop in oil and gas prices.Footnote63 As a survey by Levada in August 2017 showed,Footnote64 Russians are more worried about economic and other domestic problems than external dangers (see ).

FIGURE 4 Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “The internal problems of Russia are now more serious than external threats”? (Levada, August 2017).

Russians are often reluctant to risk greater economic difficulties for the sake of the state and its foreign policy, reflecting the limitations of what Russian sociologists refer to as “practical patriotism.”Footnote65 According to surveys administered by the Institute of Sociology, only 8% of respondents in late 2015 were “absolutely” willing to approve policies designed to restore Russian international power and defensive capacity “even if these measures were linked to a significant decline in their standard of living,”Footnote66 while 30% were “somewhat willing” to endure such costs (for a total of 38%). By contrast, 23% of respondents were “absolutely” unwilling to do so, and 39% were “more unwilling than not” to engage in such self-sacrifice (for a “willing/unwilling” ratio of 38:62). For respondents who approved “the activities of V. Putin in the post of President of Russia,” the ratio, at 45:55, demonstrates that approval of Putin’s foreign policy is often provisional even among his devoted followers; the imbalance grew to 30:70 for those who supported Putin’s presidency only “in part.”Footnote67

Only two groups of Russian respondents were more willing than not to engage in self-sacrifice to advance the power and prestige of the state: those who experienced personal economic improvement over the previous year and those who expected the country as a whole to “develop successfully” in the coming year. Yet even for these two groups (those who had experienced economic gain and those who expected economic improvement) the percentages of those “ready to sacrifice” and those “not ready to sacrifice” differed by only a few points (with ratios of 52:48 and 51:49, respectively).Footnote68

In a detailed evaluation of these and other surveys, scholars from the Institute of Sociology concluded that Russians are willing to engage in some self-sacrifice on behalf of the state, but only if it affects what were viewed as “relatively minor aspects” of one’s lifestyle.Footnote69 For example, 75% of respondents in a 2015 poll would forego the purchase of food products imported from the West, but only 9% were willing to pay higher taxes.Footnote70 Moreover, this limited commitment to self-sacrifice “gradually weakens” as painful economic conditions persist.

Against these trends, the “Crimea effect” clearly stimulated intense patriotic sentiments. After 2014, respondents more often identified love of country or patriotism as among the most important values for Russians.Footnote71 The “Crimea effect” also produced some regime-supportive attitudes that were relatively durable. In its large-sample surveys (4,000 participants) conducted in 2014–2016, the Institute of Sociology found that the number of respondents who believed the government was successful in its fight against corruption and terrorism grew significantly after the annexation of Crimea and remained at high levels.Footnote72 As the institutions most closely linked in mass perception with sociopolitical unity, stability, and safety, the presidency and the Russian Army enjoyed the strongest surge in popular trust after Crimea, with the Army attracting the most resilient level of support over the following years. Other institutions enjoyed less significant boosts. For example, trust in the Russian government (led by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev), jumped from 43% in 2012 to 56% by October 2014 (approximately six months after the annexation of Crimea), but then declined to 40% by October 2016.

The often fragile, uneven nature of the “Crimea effect” is also evident in the sociocultural sphere. Surveys of the Institute of Sociology found among respondents increasingly negative evaluations of the moral, cultural, civic, and socioeconomic condition of society. For example, 25% of participants in a survey administered a few months after the incorporation of Crimea (October 2014), believed that Russia as a moral-ethical community was growing stronger, marking an increase from 14% in 2011. By October 2016 only 9% expressed this opinion. Now 53% of respondents thought that the moral cohesion of Russian society was fraying; 38% had expressed this opinion two years earlier, in October 2014.Footnote73

These responses suggest that the Kremlin’s threat-based and great power narratives face important limits in their ability to mobilize and unite Russian society. During the historical process of state formation, particularly in Europe, military conflict or the danger of war often enabled the government to centralize and increase its extractive capacity. Perceptions of high external threat, often manipulated by political authorities, led society to cohere more closely around symbols and myths associated with patriotic duty and provide more resources to the state through higher taxation and other methods.Footnote74 In Russia, this dynamic of self-sacrifice remains comparatively weak despite the “Crimea effect.” Although tensions with the West have helped produce a “rally” response that has bolstered Putin’s authority and strengthened dislike and mistrust of the United States, this condition has not increased broad societal support for the political system or for the production and exercise of the state’s hard power, despite the prevalence of official narratives that emphasize external threat and state greatness.

Why isn’t threat perception stronger in Russian society given the regime’s control or influence over most forms of mass media? After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reach of the newborn Russian state into society was reduced dramatically by processes of socioeconomic privatization. The turbulent 1990s, when Russians could not reliably depend on the state for security, were a harsh and effective school for developing self-sufficient attitudes. Now more insulated from the state and its web of public communications, Russians increasingly privilege personal, family, and group interests—including economic concerns—over those of the state. As these interests misalign with the priorities of the Kremlin, they act to filter, shape, or otherwise blunt the messaging of the state, including its threat-based narratives.

In a late 2015 survey administered by the Institute of Sociology, 59% of respondents felt that “[safeguarding] personal interests should be the main concern of people,” while 41% agree that “people should be willing to sacrifice their personal interests” to the needs of the government. The demographic groups that placed the greatest emphasis on personal interests included residents of smaller cities, the better-educated, and those with market-based employment opportunities. Overall, 66% of 18- to 30-year-olds favored “personal interests” over those of the state, while 33% of this group believed that the interests of the government should be paramount.Footnote75 Related surveys, also by the Institute of Sociology, identify an increase in the percentage of Russians who say they are self-sufficient and do not rely on public institutions for material help (44% in early 2015).Footnote76 Although other polling data indicate that belief in the centrality of the state and its paternalistic relationship with society remains strong in Russia, the growing emphasis on private life, even at the expense of the interests of the government, is politically significant.

The growth in the autonomy of post-Soviet society is both cause and effect of the declining trust that Russians have in state-run mass media. Reflecting their reliance on alternative sources of information and perspectives—the family, the internet, business and social circles, as well as diverse forms of civic engagement—47% of respondents in a March 2017 Levada surveyFootnote77 did not trust or only partially trusted the information provided by state television, which is still the primary source of news about the country and the world for most Russians. According to another survey, this one by FOM, by mid-2017 the overall percentage of Russians who lacked confidence in state television crossed the “red line” of 50%.Footnote78 Another FOM survey more than a year later—in late 2018—found that only 47% of respondents fully trusted state-controlled media, down from 70% at the height of the “Crimea effect” in 2015. Three-quarters of the survey participants also thought that state-controlled media should contain criticism of the political authorities.Footnote79

Although Russian evaluations of external threat and domestic conditions are increasingly free of state manipulation, official messaging still predominates in a constrained marketplace of ideas where alternative, authoritative sources of mass information remain weak and dispersed. Public opinion on the existence of a seditious “fifth column” provides a useful example of the decay but also persistence of the regime’s threat-based narrative. Since the annexation of Crimea, the regime has strengthened its condemnation of allegedly treasonous or subversive activities on the part of pro-Western liberals, Russian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) with links to the West, and Western NGOs in Russia. In the July 2015 Levada survey, 37.9% of respondents felt that an organized “fifth column” existed “which supports Western efforts at weakening the Russian state,” while 29.9% believed that such claims were fabricated by a government intent on “persecuting” its opponents. Almost a third (32.3%) selected the response “It is difficult to say.”

Answering the same question almost two years later (in the March 2017 Levada survey), 37.6% of respondents now felt that accusations of a “fifth column” were fictitious (up from approximately 30%), while 33.5% continued to accept the claims of the regime (down from 37.9%). Muscovites registered the most significant change in outlook. In the July 2015 Levada survey, 31% of respondents living in the capital believed the government’s accusations of a “fifth column” were baseless. This number rose to 49% in the March 2017 Levada survey (25.3% of Muscovites still considered assertions about a “fifth column” to be credible).

Despite the declining effectiveness of the Kremlin’s narrative, the information strategy of the government still spreads considerable confusion and doubt (and also caution) among Russians who might otherwise reevaluate their political beliefs. For example, 37.3% of the 18- to 24-year-old group rejected West-inspired conspiracies in the March 2017 Levada survey. Only 22.5% believed in the existence of an organized fifth column. However, 40.3% of this group now selected “It is difficult to say” (36% chose this response in the July 2015 survey).

Although the attitudes of society often align more closely with official discourse on other issues related to the security of the Russian state, in one important case this close association likely damages the integrity of the Kremlin’s threat-based narrative. An important reason why many Russians do not perceive a serious threat from the West is the emphasis in state-controlled media on the power and ability of the Russian Army. After the bold takeover of Crimea, which seemed to confirm such claims, a strong majority of Russians expressed confidence in the armed forces to ensure the country’s safety (from 49% in April 2013 to 74% in August 2014).Footnote80 The strength of this conviction enables Russians to discount or ignore the regime’s warnings of external peril, undercutting the efforts of the Kremlin to mobilize political support.

WHAT KIND OF GREAT POWER DO RUSSIANS WANT TO BE?

How Russians define a modern great power also offers insight into their evaluation of the external environment, including what kinds of foreign threats confront Russia. Similarly, their definition of a great power helps identify dominant preferences in society for Russia’s future socioeconomic and political development.

The issue of guns versus butter underscores the inward-looking quality of Russian public opinion and its priorities for a modern power. When asked in the March 2017 Levada survey whether they prefer that Russia strengthen the military power of the state or improve the well-being of its citizens, the overwhelming majority of respondents (74.3%) chose the “well-being of its citizens.” This number rose to 80.2% in Moscow. As for Russia’s youth, analysts often maintain that a large segment of “Gen Putin” (the 18- to 24-year-old group) has been socialized into anti-American authoritarianism, forming a bulwark against the West and its values. While there is some truth in this position, only 22.5% of “Gen Putin” in the survey favored a build-up of Russia’s military strength; this group also demonstrated the strongest approval of any age group for improved ties to the West (66.1%) in another question from the same survey. Confirming the limited reach of Kremlin messaging, these attitudes weaken efforts of the regime to heighten perceptions of threat in order to augment its authority while ignoring reform of Russia’s archaic developmental model.Footnote81

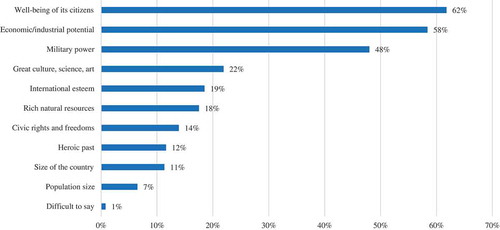

In the March 2017 Levada survey, respondents were also asked what constitutes a great power. The two leading answers were “the well-being of its citizens” (62%) and “the economic and industrial potential of a country” (58%). “Military power” came in third at 48% (up to three answers were permitted) (). While 66% of 18- to 24-year-olds selected “well-being,” no age, occupational, settlement, or educational category fell below 60% for this answer. The income groups of both “poor” and “wealthy” registered slightly above 64%. Other surveys have elicited similar responses.Footnote82

FIGURE 5 In your opinion, what constitutes a “superpower”? Select up to three items (Levada, March 2017).

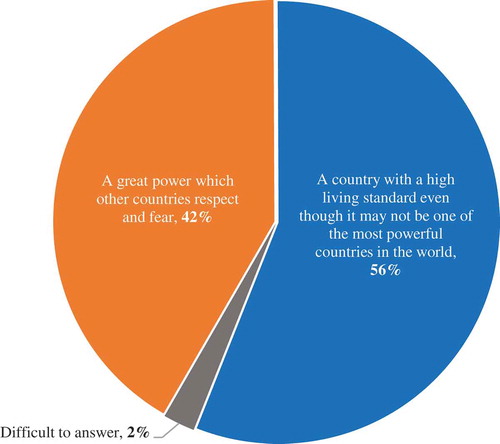

Another question from the March 2017 Levada survey probed how Russians might differently value the hard and soft dimensions of national power. The respondents were asked how they would prefer to see Russia in the future: as a great power that other countries “both respected and somewhat feared” or as a country “with a high standard of living that might not be one of the most powerful countries in the world.” Overall, 56.1% of respondents would like to see Russia as a country with a high standard of living; 41.6% felt that hard instruments of international status and influence, such as military power, should take precedence over peaceful economic development ().

FIGURE 6 Would you prefer Russia to be first and foremost…? (Levada, March 2017; % of participants who chose that answer).

The least affluent of the four income groups in the survey (“poor,” “middle class,” “upper-middle class,” “wealthy”) expressed the strongest preference for a country that enjoys a high standard of living. (61.5% vs. 36.4%). Weighing the same alternatives, Muscovites also strongly favored socioeconomic modernity over outsized clout in the international environment (63% vs. 34.4%). Although these responses indicate that the Kremlin’s efforts to cultivate a muscular national identity have achieved less success than is often assumed, support among Russians for a country that commands respect and fear did surge at the onset of the “Crimea effect” and the initial period of the crisis in eastern Ukraine. In Levada surveys administered in March and November 2014, this perspective overtook by a point (48%) the percentage of respondents who favored a country with a high standard of living (47%).Footnote83 Over the following three years, the earlier long-term pattern, in which majorities (of moderately fluctuating size) expressed a preference for a developed economy, reasserted itself (as reflected in the March 2017 Levada survey).

The October 2016 study of the Institute of Sociology provides further evidence that a majority of Russians do not prioritize hard power or an aggressive foreign policy. According to the institute’s report, Russia’s war with Georgia in 2008, its conflict with Ukraine and the West beginning in 2014, and its recent intervention in Syria did not foster a belief in society that Russia should become a militarized great power reminiscent of the Soviet Union.Footnote84 Broadly in line with the results of other surveys, the institute’s study found that only 26% of respondents wanted Russia to recapture its Soviet past in terms of expansive military capacity.Footnote85

THE DIMENSION OF ELITES: APPROACHES TO THREATS, POWER, AND IDENTITY

To what extent do the opinions of Russian elites resemble the preferences of mass publics examined above? Do Russia’s elites support an aggressive, expansionist foreign policy? Are they concerned that the external environment poses significant threats to the Russian state that require militarization? Do they emphasize hard or soft power as the foundation of a resurgent Russia?

Although detailed and reliable information about the attitudes of Russia’s elites (political, economic, security, and cultural) after the annexation of Crimea is much more scarce than data on the views of the general public, a few important sources are available for analysis. Four are particularly useful: Sharon Werning Rivera et al., The Russian Elite 2016; the survey of elites (2015) of the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences; the theses published in 2016 under the auspices of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (SVOP); and the joint study of the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) and the Center for Strategic Research (CSR), published in 2017.

The Russian Elite 2016 analyzes the latest wave of the Survey of Russian Elites, the long-term study of the attitudes of Russian elites on foreign and domestic conditions and policies. The respondents are leaders from political and bureaucratic institutions (the legislature, federal administration, etc.), private and state-owned enterprises, the security services (including the military), the media, and academic research institutions. Providing a rare measurement over time of Russian elite opinion, the Survey of Russian Elites includes seven waves: 1993, 1995, 1999, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2016. The most recent wave (as analyzed in The Russian Elite 2016) provided a questionnaire to 243 Moscow-based elites.Footnote86

The results of the survey point to the increasing legitimacy of the current regime. A majority of respondents saw no viable challengers to Putin or to the ruling United Russia Party. In terms of systemic preferences, the 2016 survey revealed that just under 20% of participants favored a “western-style democracy,” marking a decline from 27% in 2012. The poll registered a significant increase in the percentage of respondents favoring the “current political system” (42.8%, up from 31% in 2012; p. 5).

How elites conceptualize Russia’s national interests also underwent important changes since the previous survey in 2012, which was administered approximately two years before the events in Crimea. Perhaps most significant was the increase in the belief among respondents in 2016 that the national interests of Russia extend beyond its current borders. In 2012, about 43% of Russian elites held this opinion, reflecting a steady decline from a high of 82.3% in 1999. The “Crimea effect” and tensions with the West, as well as Russia’s military intervention in Syria, helped reverse this trend, driving the percentage back to the 1999 level of precisely 82.3% (p. 16). Although this renewed interest by elites in Russia’s regional and global position contrasts with the more restrained views of much of the general population, it broadly reflects the stronger external orientation of elites in other powerful, influential states.

Russia’s elites and the general public also differ, if less significantly, on the primary sources of national power. In answering the question “What determines a state’s role in the world?” respondents in The Russian Elite 2016 could choose one of two responses: “the economic and not the military potential of a country determines its influence and place in the world” or “military force will always ultimately decide everything in international relations” (p. 17). When Putin assumed office at the turn of the century, only 22% of foreign policy elites felt that military power was the key factor in determining a state’s global position. The Russian Elite 2016 marked the first time that an absolute majority of elites (52.9%, up from 35.8% in 2012) agreed that military capacity was the decisive determinant of a country’s power. “Economic potential” suffered a corresponding decline as the perceived foundation of national influence (46.5% in 2016, down from 64.2% in 2012). Only those elites born in 1971 or later felt that “economic potential” was more important than “military force” (52.6%). By contrast, almost 77% of respondents born in 1950 or before believed that military power determined a state’s position in the world (p. 18).

The survey by Bashkirova and Partners in late 2016Footnote87 asked the same question of the general population: “What determines a state’s role in the world?” Unlike the almost 53% of respondents in The Russian Elite 2016, only 34% of the participants in the Bashkirova survey believed that “military force will ultimately decide everything in international relations.”Footnote88 Among different demographic groups, only those with incomplete secondary education and older Russians (over 60 years) felt that military potential outstripped economic strength as the ultimate determinant of national power.

Despite these differences, the attitudes of elites and masses on the importance of military power share an upward trend. Recall that the top two answers to the related question in the Levada March 2017 survey (“What constitutes a great power?”) were “the well-being of its citizens” (61.8%) and “the economic and industrial potential of a country” (58.4%). “Military power” came in third at 48% (up to three answers were permitted). If we track responses to this question over time in other Levada surveys of mass publics, we find that only 30% of respondents selected “military power” in 1999, the eve of the Putin era. By 2012, “military power” was chosen by 44% and by 2017, 48% of respondents.Footnote89 During the same period (1999–2017), the percentage of responses for “well-being of its citizens” and the “economic and industrial potential of a country” remained about 60%, straying by only a few percentage points, plus or minus.

If belief among elites and masses in the positive effect of military power on Russia’s international status continues to increase, even if at somewhat different rates for each group, approval of forms of militarization is likely to grow as well. Such a development might, in turn, encourage external confrontation, weaken elite and popular support for balanced economic development, and strengthen acceptance of domestic political regimentation as society’s understanding of a great power rests increasingly on military factors.

Working against this possible outcome is the continued, strong preference of elites and mass publics to prioritize a national agenda that tackles domestic problems. The data in The Russian Elite 2016, drawn from the 2016 wave of the Survey of Russian Elites, indicate that the great majority of respondents (80.8%) believed that the United States poses a threat of some kind to the security of their country. Yet, in line with the March 2017 Levada survey and other polls of the Russian public, most of the elites did not perceive America to be a grave or immediate military or political menace.

As analyzed in The Russian Elite 2016, the 2016 wave of the Survey of Russian Elites asked respondents to evaluate several potential dangers to Russia on a 5-point scale, with 5 representing an “utmost threat.”Footnote90 A plurality of respondents (32.1%) thought that the “inability to solve domestic problems” was an “utmost threat” (36.7% selected this response in the 2012 wave of the survey), while 22.2% considered “terrorism” in the same light. The “growth of the U.S. military vis-à-vis the Russian military” trailed far behind, with only 7.4% of respondents selecting this factor as an “utmost threat”: the lowest level since the 1993 wave (7.1%). Earning even lower percentages were “border conflicts in the CIS countries” (4.5%), “ethnic (domestic) tensions” (3.3%), “information war conducted by the West” (2.5%), and “color revolution” (2.2%).

It is noteworthy that the participants in different waves of this survey of elites found domestic problems much more worrisome than U.S. military power, American information warfare, or a “color revolution” fomented by the West, each of which the Kremlin has framed as important threats in its efforts to mobilize domestic supporters and isolate opponents. These results and other data suggest that a significant number of Russia’s elites do not believe the Kremlin should emphasize costly policies designed to offset U.S. military power or other potential American threats.Footnote91

The Institute of Sociology conducted a survey in late 2015 which offers additional insight into the political attitudes and policy preferences of key segments of the Russian elite. In its report based on the survey, the institute analyzed the views of an occupational cross-section of influentials similar to that of the Survey of Russian Elites project, including 154 leaders (94 in Moscow and 60 in different regions) in the following categories: government, business, the “third sector” (NGOs, civil society), mass media, and science.Footnote92 The stated purpose of the survey was to elicit assessments of the health of Russia’s society and political system as well as views on the prospects for national development over the next five years.

Gathered during the patriotic upsurge of 2015, the results of the survey challenge to an important extent the claim that Russia now enjoys significantly greater solidarity within society and between society and the state due to the mobilizing effects of the Sochi Olympics, the annexation of Crimea, the ensuing conflict with Ukraine, and particularly the subsequent confrontation with the West. While these events buoyed the standing in society of the president and the armed forces as well as bolstered patriotic pride in Russian identity, their positive effect on how elites evaluate the sociopolitical system appears limited. The survey confirms that diverse Russian elites often remain more preoccupied with domestic problems than with threats from the external environment or with Russia’s status as a great power.

Using a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), the first question of the survey asks respondents to “evaluate the current condition of Russian society” according to “important characteristics” that might be found in any country. A list of 13 items, such as the “level of inter-ethnic tensions” and the “level of tolerance,” was given to the participants. The only item to receive a score of “8” (relatively high) was the “level of social stratification” in Russia and society’s unequal access to resources.

At a time (2015) when one might expect to find robust evidence of the “Crimea effect,” the “level of patriotism” scored only 5.8 on the 10-point scale. Respondents placed the “physical and psychological health” of society at a relatively low 4.3, while the “moral condition of society” registered 4.2. The degree of trust in government was scored at 3.9, and interpersonal trust in society at 3.5. Confidence in Russia’s “democratic values and institutions” (elections, parties, and the media) came in last at 2.9.Footnote93

The answers to other questions in the survey reveal the policy priorities of many elites and their evaluation of foreign and domestic threats. In their assessment of dangers emanating from the external environment, respondents identified the dependence of the Russian budget on international oil and gas markets as the greatest threat (8.3) among the 13 items on the list, a reference to the vulnerabilities of Russia’s economic model. The prospect of Russia being drawn into a broader conflict in Ukraine was next (8.1), followed by capital flight and the decline in foreign and domestic investment (7.6). Although respondents were fearful of a new Cold War accompanied by an arms race with harmful effects on Russian development (7.2), they placed the “information-psychological warfare” of the West, as well as the threat of a “fifth column,” last on the list, at 5.0.Footnote94

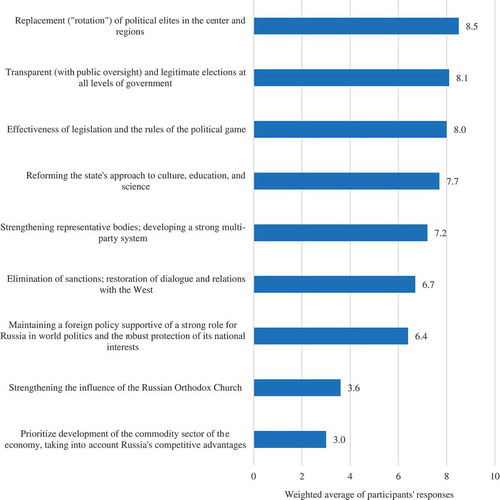

When respondents were asked in another question what conditions were necessary for Russia to achieve the “desired situation in … society by 2020,” the selection “restoration of Russia’s strong role in international politics” lagged behind domestic issues, placing seventh (6.4) on a list of nine items. Instead, the elites in the survey viewed political reform and authentic democratization as most important. The “rotation” (replacement) of political elites “in the center and regions” came in first (8.5) and holding “transparent and legitimate elections with societal controls at all levels of government” took second place (8.1) ().Footnote95

FIGURE 7 To what extent are the following conditions necessary to achieve the desired situation in Russian society by 2020? Scale: 1-10 (1 = no need; 10 = highest need) (Institute of Sociology 2015).

The respondents recognized that political renovation would require fundamental changes in Russian political culture, particularly the need to overcome widespread political apathy and alienation. Asked to identify the conditions and processes that would promote the development of Russian society, they selected as their first choice (8.1, out of nine items) the need to cultivate civic activism and “sociopolitical activity” which would pressure ruling elites “to change existing conditions.”Footnote96

RESISTING THREAT-BASED NARRATIVES: PUBLIC CALLS AMONG ELITES FOR DOMESTIC REFORM AND EXTERNAL CAUTION

Other survey data show that a significant number of Russia’s political, economic, and cultural elites are concerned by the regime’s failure to address chronic socioeconomic and political problems arising from authoritarianism and a statist developmental model.Footnote97 In mid-2016, Russia’s leading foreign policy think tank, SVOP, published a high-profile program advocating reform. The theses of the program (entitled Strategiia XXI) were intended to shape a new foreign policy Concept for Putin’s expected fourth presidential term.Footnote98 The theses are of particular importance given SVOP’s proximity to centers of power in the Kremlin.

Composed of influential foreign policy and security experts, the SVOP working group engaged in discussions with almost two hundred politicians, academics, and other elites of “diverse ideological orientation.” The project was led by Sergei Karaganov, the director of SVOP and dean of the Faculty of International Economics and Foreign Affairs at the Higher School of Economics (HSE), and by Fyodor Lukyanov, the head of the Presidium of SVOP, research professor at HSE, and editor of Rossiya v global’noi politike, the leading Russian journal of international politics.

The theses of Strategiia XXI begin with praise for Russian foreign policy under Putin. The document views Russia’s incorporation of Crimea as a master stroke that stopped Ukraine from being pulled into the Western orbit by an aggressive United States. More generally, the annexation halted the advance of Western military and political institutions toward Russia—which was the crucial issue that Russia under Yeltsin had neglected in the 1990s. Identifying Russia as a resurrected great power, the authors discuss its national interests in capacious regional terms, maintaining that the Kremlin’s foreign policy was able to stop the “collapse of historical Russian imperial space” despite determined encroachment by the West.

The theses also contend that Russia has successfully wielded its soft power against political and cultural threats from the West. Attempts by the United States to spread its “decadent” culture and “revolutionary democratic messianism” as instruments of regional and global hegemony, including “regime change,” are judged a disaster. Russia helped bring about this failure with its “international ideology” of “new conservatism” which emphasizes state sovereignty, traditional and religious values, and opposition to radical secularism. According to the authors, Russia must continue to hold the United States at bay but also engage in selective cooperation on security issues, such as terrorism, as it turns to the east and south to deepen regional relationships, particularly with China. Defining Russia’s national identity as Eurasian, the theses reject as futile post-Soviet efforts by Russia to seek integration with the West.

The authors of the theses temper their positive assessment of the Kremlin’s foreign policy with clear warnings, particularly against a new arms race that might replicate the militarized overextension that gravely weakened the Soviet Union.Footnote99 They also warn against policies of aggressive ethno-nationalism, maintaining that demands within Russia to “protect the Russian world” (particularly in the “near abroad”) with military force are both “unrealistic and counterproductive.”

Building on these sober assessments, the theses emphasize that Russia must better evaluate dangers emanating from the West. The American threat, according to the theses, is not from military power or a U.S.-inspired color revolution. Stung by failure in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, America is said to increasingly devote its energy to economic development as the core element of its national power. China similarly continues to bet on sound economic growth as the primary base of its international influence.

For Strategiia XXI, the primary peril for Russia as a resurgent great power is the state’s misuse and waste of the nation’s socioeconomic resources: a threat made pressing by the multiplier effects of the global technological revolution. Echoing the dominant preferences identified above in mass and elite surveys, and challenging the position of many foreign policy elites that military capacity is the central attribute of national power, the theses emphasize that strong and balanced economic development remains the “primary determinant” of a state’s international influence.

Refusing to blame the West for Russia’s quandary, the document notes that Russia has failed to confront the economic stagnation that emerged several years before (emphasis added) the conflict with the West over Ukraine. According to the theses, Russia should immediately promote durable economic growth by preserving, developing, and recovering its “human capital” through the political, moral, and economic “modernization” of the country. Although the theses do not outline specific reforms to accomplish these objectives, the position papers and other materials produced in support of Strategiia XXI acknowledge that the mobilization of human capital will require far-reaching changes. These include large increases in state funding for health care and education; the expansion of individual civil and socioeconomic freedoms made possible by a significant retraction of the state’s role in regulating society; and the development of the rule of law.

Strategiia XXI concludes that the primary task of Russian foreign policy is to ensure that Russia successfully confronts the steering crisis which today “endangers its long-term interests in the world” and even “its sovereignty.” Foreign policy must now generate forms of international cooperation in support of the primary goal of economic, scientific, and technological progress.Footnote100 Yet Sergei Karaganov, the creative force behind Strategiia XXI, observes that ruling elites in Russia have failed to provide strategic direction to the country for years.Footnote101 Instead, they have exaggerated external threats in order to preserve the status quo and derail pressures for reform.Footnote102

Theses on Russia’s Foreign Policy and Global PositioningFootnote103 is another important source of elite attitudes about the need for liberal economic modernization and how the external environment determines this requirement. Published in mid-2017, the theses are a joint project of two prominent think tanks: the RIAC, led by Andrey Kortunov (the director general), and the CSR, represented by Sergei Utkin, the head of CSR’s Foreign and Security Policy Department.Footnote104 The CSR is an organizational base of Alexei Kudrin, the reformist economist who serves as its chairman of the board. In 2016, Putin selected Kudrin to serve as deputy chairman of the Presidium of the Presidential Economic Council. The theses also draw on the results of a parallel study conducted by a team of researchers at the Primakov Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the Russian Academy of Sciences. As part of the project, thirty interviews were conducted with RIAC members, including prominent diplomats, leading international relations experts and executives, and business entrepreneurs.