ABSTRACT

Understanding peoples’ values and beliefs relating to wildlife is important in regions where human wildlife conflict is prevalent. This study investigated wildlife value orientations (WVO) among subsistence farmers in Bhutan. We explored WVOs and how they shape peoples’ attitudes toward wildlife using 48 semi-structured interviews and 8 focus group discussions in four districts. A qualitative thematic analysis of this data revealed alignment with seven WVOs identified from the literature. Most respondents showed positive WVOs related to widely held Buddhist beliefs; however, negative WVOs were dominant amongst herders, whose livelihoods were most affected by wildlife. This leads to personal and community dissonance between societal religious beliefs and WVOs. Policies that address HWC should capitalize on positive societal beliefs and WVOs but recognize that herders will need a particular focus to overcome negative WVOs. Policies need to be redesigned to avoid future negative impacts on people, livelihoods, and conservation objectives.

1. Introduction

A better understanding about peoples’ values regarding wildlife is needed for explaining fundamental differences in people’s attitudes toward wildlife (Fulton et al., Citation1996). Such understanding can aid in resolving wildlife related conflicts (Gamborg & Jensen, Citation2016). As Manfredo and Dayer (Citation2004, p. 317) state, “the thoughts and actions of humans ultimately determine the course and resolution of the conflict”. The Typology of Biophilia Values (Kellert, Citation1993, p. 59) describes the variety of ways in which humans relate to wildlife, and has been valuable for understanding Human Wildlife Conflict (HWC) issues (Manfredo & Dayer, Citation2004). The Wildlife Value Orientation (WVO) concept has provided conceptualization of values and associated attitudes and behaviors toward wildlife (Manfredo et al., Citation1995).

Value frameworks drawn primarily from developed country contexts have supported research. WVO studies conducted in developing regions include: Mongolia (Kaczensky, Citation2007), Thailand (Tanakanjana & Saranet, Citation2007), and China (Zinn & Shen, Citation2007). To date, no study on WVOs has been conducted in Bhutan. Building on these past studies, this research used Kellert’s typology of Biophilia values and the Manfredo et al. (Citation1995) concept of WVOs to study WVOs related to Buddhist beliefs in Bhutan to fill this knowledge gap.

As with many countries across Asia, incidences of HWC have intensified in many parts of Bhutan (Karst & Nepal, Citation2019; Wangchuk et al., Citation2018). HWC is defined as “occurring when the needs and behavior of wildlife impact negatively on the goals of humans or when the goals of humans negatively impact the needs of wildlife” (Madden, Citation2004). In Bhutan incidences of HWC involving numerous wildlife species have been widely reported from different parts of the country. Species commonly cited as depredating livestock included Tiger (Panthera tigris), Leopard (Panthera pardus), Himalayan black bear (Ursus thibetanus), Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus), Snow leopard (Panthera uncia), and Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus chanco) (Jamtsho & Katel, Citation2019; Sangay & Vernes, Citation2008; Wangchuk et al., Citation2018). The main species involved in crop raid are Wild pig (Sus scrofa) and Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus) (Tobgay et al., Citation2019; Wangchuk et al., Citation2018; Yeshey et al., Citation2022). Human injury is caused mainly by Himalayan black bear and Asiatic elephant (Letro et al., Citation2020; Penjor et al., Citation2020; Yeshey et al., Citation2022). Much of the population in Bhutan is subsistence farmers engaged in crop farming, livestock husbandry and collection of non-wood forest products to support their livelihoods (Choden et al., Citation2020).

Buddhism is the state religion in Bhutan, with ~ 90% of the total population Buddhist (Givel, Citation2015). Buddhism recognizes that all sentient beings could go through emotions such as fear, love, desire and are capable of suffering and pain (Barstow, Citation2013). The Buddhist belief system thus has strong eco-centric dimensions, which shapes adherents’ attitudes toward wildlife conservation. Bhutanese people and wildlife have coexisted for centuries because of these strong religious beliefs and cultural ethos (Thinley & Lassoie, Citation2013). Buddhist beliefs now co-exist with modern conservation policies, implemented in 1993 with the development of a system of protected area networks and progressing through a range of measures to protect and increase wildlife populations. Under these policies, HWC has increased (Karst & Nepal, Citation2019).

In view of this situation, Bhutan makes an interesting case study to examine the prevailing WVOs and how these WVOs and Buddhist beliefs shape peoples’ attitudes toward wildlife and HWC, particularly in relation to livelihood activities. The following research questions guided our study:

What are the types of WVOs in rural Bhutan?

How do the Buddhists beliefs shape WVOs?

How do WVOs shape respondents’ attitudes and behavior toward wildlife and HWC?

How do the WVOs vary between people depending on different livelihood types (Crop farming vs. livestock husbandry)?

1.1. Conceptual Background

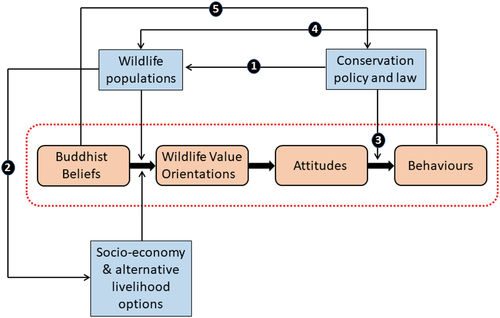

Religious beliefs and WVOs influence attitudes which in turn shape people’s behavior toward wildlife (Bhatia et al., Citation2017). Historically religion has played a central role in mobilizing policy changes, influencing values, providing meaning, and regulating peoples’ actions (Mcleod & Palmer, Citation2015). Most religions remain as an important wellspring of human concerns for other living beings (Negi, Citation2005) and promote ethical and moral codes of conduct, including support for conservation (Rinzin et al., Citation2009). Religion is defined as “an institutionalized set of beliefs and practices” (Ver Beek, Citation2000), and religious beliefs are cognitive associations between object concepts and truth-value concepts (Coleman et al., Citation2018).

Values are defined as “desirable trans-situational goals, varying in importance that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity” (Schwartz, Citation1994) and value concepts have been used as means of understanding peoples’ thoughts and behaviors related to wildlife, and/or HWC management (Manfredo, Bruskotter, et al., Citation2017). Value orientations are defined as networks of basic beliefs that organize around values and provide contextual meaning to those values regarding wildlife (Fulton et al., Citation1996). WVOs are most directly relevant to HWC and often suggested as a useful entry point for understanding HWC issues (Manfredo & Dayer, Citation2004). In this study, we used the Typology of Biophilia Values (Kellert, Citation1993, p. 59) to explain the different orientations (See ).

Table 1. A typology of Biophilia values, used as a framework of basic wildlife orientations.

Most WVOs relate to religious beliefs. People subscribing to religious beliefs with loving kindness, nonviolence, and compassion as core values are likely to relate to moralistic, humanistic, spiritual and sacred value orientations toward wildlife. Similarly, people with mutualism value orientation believe in wildlife deserving of loving kindness, trust and care (Laverty et al., Citation2019), the central tenets of Buddhist beliefs. Conversely, in some religious tradition, people believe that animals were divinely created to serve human interests, representing utilitarian orientation imposed by religion (Mcleod & Palmer, Citation2015). However, regardless of religious beliefs and cultural values, wild animals are abused in various ways (Cohen, Citation2013).

The complex concepts of human values underpin people’s attitudes and behaviors. Attitudes are favorable or unfavorable dispositions toward an action, an issue, or an event (Manfredo & Dayer, Citation2004). Behaviour on the other hand refers to actions (Ponizovskiy et al., Citation2019) while behavioral intention is the sign of a person’s readiness to perform a given behavior (Niaura, Citation2013). The concept of attitude has been central to attempts to predict and describe human behavior (Kansky & Knight, Citation2014). Two of the main factors influencing people’s attitudes about wildlife are wildlife interactions, both positive and negative (Nsonsi et al., Citation2017) and the under lying religious beliefs and values (Bhatia et al., Citation2017). In northern India for example, Buddhists showed positive attitudes toward carnivore conservation, but not Muslims (Bhatia et al., Citation2017).

Human behavior is determined by a complex interaction of internal factors (e.g., values, beliefs, attitudes, norms) and factors external to the person, such as wider community attitudes including those expressed through conservation laws and policies and associated sanctions (Reddy et al., Citation2017). Religious beliefs have an influence on human behavior (Minton et al., Citation2015), which is mediated by WVOs, that is religious beliefs cause people to develop certain WVOs and these values are one of many factors that then influence human behavior.

Laws and policies, like other social institutions, have a two-way relationship between those governing and the people being governed. They are made and shaped by people, but also people are shaped by the laws and policies around them (Lawrence, Citation1969). Laws and policies indicate expected norms of behavior and reflect societal values and beliefs. Effective conservation efforts have facilitated a rebound in wildlife populations (Karanth & Vanamamalai, Citation2020; Madden, Citation2008) (see & arrow 1), but they have also contributed to more HWC and impacts on peoples’ livelihoods (Madden, Citation2008) ( & arrow 2). Conservation laws and policies often punish or penalize people who kill a threatened or endangered species in retaliation ( & arrow 3). This can change human behavioral intention and can increase hostility toward wildlife and conservation ( & arrow 4). Religious beliefs also influence the formulation of conservation laws and policies (Rinzin et al., Citation2009) ( & arrow 5).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of HWC illustrating how religious beliefs may have shaped people’s WVOS, and WVOs in turn influence attitudes and then attitudes shape human behaviors toward wildlife and the response actions taken. The arrows represent the relationships, how one component is affecting or influencing the other in the framework. These components in turn can be influenced by other factors such as conservation laws and policies, wildlife population and socio-economy.

In this research, our analysis is based on the elements in our framework of Buddhist beliefs, WVOs, attitudes, and behavior (see red dashed rectangle in ) that can be also influenced by external factors (e.g., conservation laws and policies).

2. Research Methodology and Context

2.1. Geographical Context and Developmental Philosophy

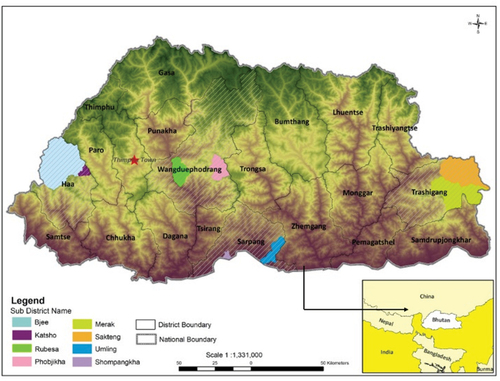

Bhutan (38,394 km2) is in the eastern Himalayas, between the Tibet Autonomous Region to the north and India to the east, west, and south (). About 71% of the country is under forest cover. All wild animals and wild plants listed in Schedule I in the legal framework for conservation are fully protected while other wild animals, not listed in Schedule I, are also afforded protection. Crop farming is the economic mainstay of the country; however, it occurs on only 2.75% of the total geographic land area (FRMD, Citation2017). More than 90% of farming communities are comprised of subsistence farmers. The Bhutanese version of sustainable development is guided by the philosophy of gross national happiness which emphasizes that development pathways must be socially, economically, culturally, and environmentally sustainable (Yangka et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Study Area and Livelihood Source

This research is part of a larger study across four districts of Bhutan (Yeshey et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Multi-level sampling was applied with the aim of including adult participants with diverse circumstances in relation to HWC, primarily different livelihoods and locations inside or outside a protected area. One district was selected to represent each of Bhutan’s four regions (). The four districts are: Trashigang (Eastern region); Sarpang (Central region); Wangduephodrang (West Central region); and Haa (Western region). Within each district, two sub-districts were selected: one located inside a protected area and the other outside the protected area. Pastoralism is the primary source of livelihoods for people of Merak and Sakteng in Trashigang. Similarly, in Haa, pastoralism is the main livelihood source though it is also supplemented with crop cultivation. Livestock animals reared by the herders in Trashigang and Haa include Yak (Bos grunniens), cattle (B. taurus), sheep (Ovis aries), and horses (Equus caballus). In Saprang and Wangduephodrang livelihoods are primarily based on crop farming supplemented with livestock rearing and collection of non-wood forest products.

For all livelihood types and land tenures, the larger study identified substantial economic losses through HWC (Yeshey et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). About 14 wildlife species are involved. Among livestock predators, Asiatic wild dog was dominant in Trashigang; Tibetan wolf and Snow leopard in Haa; Asiatic wild dog and Leopard in Wangduephodrang and Tiger in Sarpang. Amongst crop raiders, Wild pig and Asiatic Elephant were dominant. The species causing highest economic losses overall were Wild pig and Asiatic wild dog through crop and livestock depredation respectively. Economic losses were higher for farmers whose livelihoods depended mainly on livestock and for those residing inside protected areas (Yeshey et al., Citation2023).

2.3. Participant Selection and Data Collection

An exploratory qualitative approach was used (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation1994), as there has been no previous research on human values toward wildlife in Bhutan. Focus group discussions (FGD) and semi-structured interviews were combined to identify and organize Buddhist beliefs, WVOs, attitudes, and behaviors as conceptualized in .

Following the selection of the eight sub-districts, an FGD was held with key informants in each sub-district (8 FDGs), mainly for the purpose of collecting information to select households for interview and to get an overview of HWC at sub-district level. In each sub-district, 5–7 key informants judged to have longer crop and livestock farming experience and good knowledge of HWC were purposively selected in consultation with the head of the sub-district (Gup), agriculture, and livestock extension staff. The key informants were also asked questions similar to those in the semi-structured interviews and thereby provided data about HWC and values, enabling triangulation with the interview data.

Within each sub-district, households were grouped based on wealth category and gender of the household head. All households in each selected sub-district were listed and grouped according to local criteria for wealth classification into three wealth groups: Rich, Average, and Poor. Local criteria for wealth classification (understood through FDGs) included land and livestock holding size, type and size of the house, number of household labor, and number of family members in government service. Within each wealth group, one male-headed and one female-headed household were selected randomly, six households from each sub-district making 48 households in total from the eight sub-districts. Then from each selected household, one adult member was interviewed, in most cases the head of the household. Where household head was not available, another adult member of the family was interviewed.

Field data collection was then conducted according to ethics approval from the University of Melbourne (Ethics ID: 1955056), following consent, and data storage protocols. Interviews were carried out in the local language by the first author who is a native Bhutanese speaker at each respondent’s residence. The interviews lasted ~ 45–60 minutes with another 15–20 minutes for checking accuracy and completeness. The semi-structured interviews started with a few questions about HWC (e.g., Is HWC occurring in your village?) to set the context and understand the respondent’s experiences with HWC, if any (Yeshey, Citation2023). Questions were then asked related to the main concepts of interest, including: attitudes (e.g., how do you feel when you see/encounter wild animals?); behaviors (e.g., What do you do to protect your crops and livestock from wild predators?); values (e.g., How important is wildlife to you?) and conservation (e.g. how important is protection of wild animals to you?). Throughout the interview, respondents were encouraged to further explain their values related to each theme, using the key question, Why is that important to you? repeated as necessary. This question also elicited expressions of Buddhist beliefs, if these were not otherwise raised by the respondent. Thus, the interview used a modified value laddering method (Ford et al., Citation2019) to elicit values and religious beliefs. This method was more suited to exploration of the link between Buddhist beliefs and WVOs in the context of HWC in rural Bhutan than the standard WVO survey interview guide developed by Dayer et al. (Citation2007). All interviews were audio-recorded with permission from the respondents and written notes were taken. After each interview, the notes were read to the respondent to check for accuracy and completeness and then further crosschecked with the audio recording. Data was anonymized and stored securely. The semi-structured interview guide had been pre-tested with 12 Bhutanese people of varying ages and sexes living in Melbourne to determine if respondents understood the questions as well as if the questions elicited the required data to answer the research questions.

2.4. Data Analysis

Qualitative thematic analysis was used to code interview and focus group data. After acquiring a deep and thorough familiarity with the data, the first author developed broad themes/nodes for analysis following a partly inductive and partly deductive process (Azungah, Citation2018). The other authors reviewed the process and the themes identified. Themes identified inductively included for example conservation laws and policies. Prevalent in the data were values that fitted with Kellert’s (Citation1993) typology of Biophilia Values, attitudes, and WVO-attitude-behavior relationships. Having identified the relevance of these concepts, the first author then coded for them following a primarily deductive process (Azungah, Citation2018). The definition of the Sacred WVO was informed by the Dandy (Citation2005) classification of wildlife values. Then the other authors reviewed the process and the results.

In the following section, we present results for each of our research questions. First, we report the WVOs expressed by respondents and their potential causes. Second, we report the respondents’ attitudes toward wildlife and HWC management as shaped by WVOs and Buddhist beliefs. Finally, we explore respondents’ attitude and behavior relationships. We present results for all respondents combined and, where relevant, note any key differences between livelihood types.

3. Results

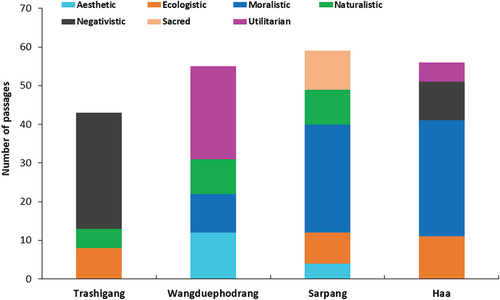

The semi-structured interviews revealed seven WVOs among the participants (). The two most frequently expressed WVOs were Moralistic and Negativistic with 101 and 40 passages respectively. Moralistic, Sacred, Utilitarian and Aesthetic value orientations were expressed mostly by crop farming-based livelihood respondents while negativistic orientation ranked the second highest and was common among the livestock farming-based livelihood respondents.

Table 2. Frequency of coded passages for WVOs by livelihood types in Bhutan (n = 48).

3.1. Wildlife Value Orientations

3.1.1. Moralistic

Moralistic value orientation was the most common (n = 31). This is most likely because of the Buddhist belief about reincarnation that provides another dimension to moralistic value orientation. It specifies the fundamental similarity of all animals, each endowed with equivalent rights to existence with ethical treatment, which is the basic principle of the moralistic value orientation. The perpetual cycle of birth and rebirth, which is central to Buddhist belief, engenders a commitment to nonviolence and compassion toward all living beings. For example, respondent (#8) stated:

Some people think animals are different from human. For me, we are all the same. I get hungry and animals get hungry. I want to live happily, and animals do aspire to live a happy full life because they have feelings. We should not harm animals, instead we should show empathy towards them. Killing, lying, stealing are non-virtuous actions that will lead us to bad Karma and suffering.

3.1.2. Sacred

A fewer number of respondents (n = 9) expressed sentiments linked to the sacred value of wildlife as the primary justification for wildlife protection, although they often expressed sentiments reflecting other orientations such as moralistic, humanistic, and aesthetic in their discussions of the need to protect wildlife. One specific tenet in Buddhist beliefs and culture was also revealed in the Sacred WVO: the high respect toward elephants and tigers. These respondents constantly expressed a spiritual connection with elephant and tiger, emphasizing the interconnections within nature and their own spiritual connection to some species. For example, respondent (#21) stated:

We worship elephant as Lord Ganesh asking to bless us with wealth and long life. Likewise, tigers are highly respected because they are protective deity and any action that can displease them can have repercussion on us.

3.1.3. Utilitarian

Sixteen respondents indicated a utilitarian WVO as the primary motivation for wildlife protection. This primarily derived from their role in, and benefits received from, ecotourism: with wildlife and associated nature as sources of pleasure, excitement, happiness and enjoyment for tourists and the willingness of tourists to pay for these wildlife experiences. Community income for these experiences was generally indirect, received through local accommodation and food, but also directly in payment to guides. This orientation also demonstrated in views about the necessity of a healthy natural world for human “well-being,” and the psychological benefits of wildlife. Some respondents noted the use of forest by people as a source of various forest products for both human and livestock.

3.1.4. Ecologistic

A few respondents (n = 12) indicated a related orientation, describing an appreciation for the diverse role wildlife play within ecological processes and noted that ecological integrity is necessary for human survival. These respondents acknowledged the importance of species diversity as much as human beings as components of functioning ecosystems and a natural cycle. They have great appreciation for the beauty of nature (aesthetic and naturalistic orientations) and believe that nature is intrinsically valuable for which they are morally obligated to preserve. Such expressions indicate respondents’ perspectives reflecting Buddhist beliefs about interdependence and/or interconnectedness and living in harmony with nature.

3.1.5. Naturalistic

The appreciation and the enjoyment that respondents noted to experience from an active engagement with nature demonstrated their naturalistic WVO. Some respondents (n = 8) considered forests as an excellent environment in which to bring about one’s transformation of consciousness, which resonates with Buddhist beliefs. This naturalistic orientation also reflects the Buddhist belief of interconnectedness and living in harmony with nature.

3.1.6. Aesthetic

More than a quarter of respondents (n = 15) expressed an aesthetic value of wildlife as the primary justification for wildlife protection, albeit their expressions also echoed naturalistic, humanistic, sacred, and moralistic orientations. These respondents spoke of how the elegant appearance of the black necked cranes (Grus nigricollis) attracts visitors to the valley. They expressed how the cranes leaving to summer roosting place brings sadness to them. This value orientation harmonizes the living in harmony with nature, an essence of Buddhism.

3.1.7. Negativistic

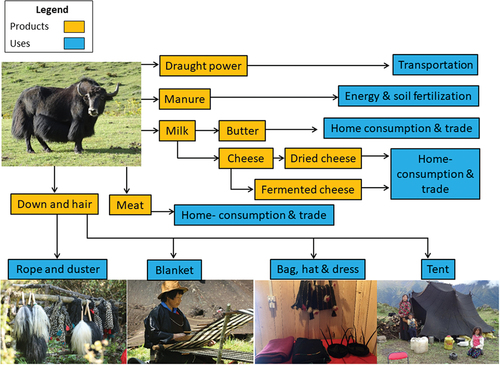

Demonstrating a substantially different value orientation (n = 17), respondents who derive their living mainly from livestock husbandry, consistently expressed a negativistic WVO. Lack of an alternative livelihood source and the economic losses caused by wildlife through depredation of yaks tended to trigger the negativistic orientation. Yaks are their lifeline (Supplementary Figure). Respondents also spoke of the constant worries, frustrations, and fears caused by wildlife that made them feel insecure (). For example, respondent (#32) stated:

My family lost few yaks almost yearly. I and my son stay with our herd all the time. Still, we lost yaks which caused us huge economic loss. Now whether these wild animals come to kill or not, there is no peace of mind, the worry and the fear do not go, they stay there in our head. I cannot sleep peacefully.

Herders often lamented how the current HWC situation pushes them to make hard life choices between their beliefs and their livelihoods. This is considered further in the next section.

3.1.8. Distribution of WVOs by Districts

A cross tabulation of the coded themes (WVO) with districts revealed the dominant WVO in each district. The results showed that Kellert’s typology of basic WVOs mostly fits the situation in Bhutan with some difference in dominant WVOs between districts ().

Figure 3. Wvos by districts presented in descending order (Dominant to less dominant and weak to weakest).

Our results also identified considerable overlaps between several WVOs. For instance, whereas the expression of a moralistic orientation among the respondents reflected some degree of love and care toward wildlife, this blended with the humanistic WVO. The moralistic WVO was also very closely related to the concept of sacred value. Other overlaps were found between aesthetic, naturalistic, and “utilitarian concept” in the context of this study. For instance, few respondents often referred certain forests as a holy place for appeasing local deities, a Buddhist cultural belief about sacred groves. Local people protect these patches of forests for their religious importance. Other respondents echoed similar expressions, suggesting utilitarian perspectives are shaped by naturalistic, aesthetic, and religious interests.

3.2. Respondents’ Attitudes Toward Wildlife

Despite the damage caused and the economic losses incurred by wildlife, respondents with moralistic, sacred, utilitarian, ecologistic, naturalistic, and aesthetic value orientations showed positive attitudes toward wildlife. Positive attitudes refer to the willingness to coexist with wildlife and acceptance of the losses caused by wildlife. They consistently spoke of the “Karmic cycle”, the “Non-violence,” and the “Compassion,” as the cause of their willingness to support wildlife conservation. In line with these ethics, respondents believed that those who cause violence and suffering to other living beings will experience that similar pain at some time in the future. For example, respondent (#10) stated:

If we kill animals, we are ruining our own life. We have to go through the same pain that we caused to those animals. Being kind and sympathetic to others including animals mean being kind to our own self because we accumulate merits. Nobody wants pain and suffering. Wild animals kill our yaks and cause us loss but killing wild animals will cause us more pain.

With these beliefs, respondents spoke of the need for moral treatment of all living being and to refrain from any retaliatory actions. This encourages sympathetic attitude toward wildlife that guides their behavioral direction. For example, respondent (#34) stated:

Killing of any other living being is sinful and it is as bad as killing of our parents. We believe that, if we kill animals in this life, the same animals will kill us in the same way in our next life.

The positive attitude is, in part, because of their ecologistic WVO. Respondents acknowledged the diverse roles of wildlife within ecological processes and functioning of ecosystem. Respondents noted how wildlife maintain forest soil fertility through dropping of their feces, decay of their carcasses, and dispersal of seeds of wild plants from one place to another. Respondents also recognized how one species controlling the population of another species, pointing example of leopard controlling barking deer (Muntiacus) population in one of our research sites. The varying appreciations for wildlife are summed up in respondent (#20’s) statement:

We depend on forest for fodder, firewood, vegetables, medicines, and so many other things and forest is wild animals’ home. We need wild animals; they are part of what we need in the world.

While most respondents showed positive attitudes toward wildlife; we did encounter respondents with negative attitudes, especially those respondents whose livelihoods depended entirely on livestock husbandry. Livestock, especially yaks, are fundamental to their survival and act as a store of capital. They depend heavily on yaks for food, clothing, housing (their tents are made of yak hair) and earning cash. Additionally, the inaccessible locations and marginal existence make these herders’ livelihoods difficult to diversify, making them more vulnerable to shocks and livelihood insecurity. Losing a yak to Asiatic wild dog affects every aspect of their life and livelihoods. For instance, respondent (#10) stated:

We have only yaks as our livelihood source, when they are killed and eaten by wild animals, our cash income, food and even wool for making our dress are all gone. We borrow from neighbors, or we go for off-farm work.

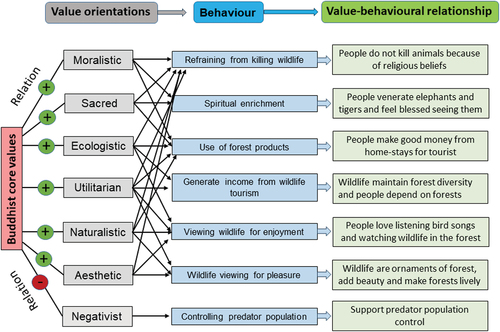

3.3. Respondent WVO-Behaviour Relationships

Our data also made it possible to describe several relationships between respondent attitudes and behaviors. Most respondents spoke of the importance of wildlife conservation and described a host of reasons (). For example, utilitarian WVO (non-consumptive ecotourism value) of wildlife was frequently mentioned by respondents in Phobjikha as an expression of positive attitude toward wild animals. They relate this to visits to the valley by international and local tourists who were attracted by black-necked cranes because of the bird’s aesthetic value (). Respondents responded to this by setting up homestays, a pro-conservation behavior for humans and cranes to live in harmony. For example, respondent (#39) stated:

Lots of people from other countries visit our place to see cranes. We have many home-stay owners who are making good income. We do not have to feed cranes; all we do is not harming them and sharing the valley with them while they come here in winter.

Figure 4. Illustration of how multiple values underpin particular human behavior with examples of value-behavioral relationships identified in the study.

Respondents also supported conservation, in part, because of their engagement with wildlife (). They spoke of the pleasure, excitement, and enjoyment they experience on hearing bird songs or seeing wildlife and feeling spiritually enriched on encountering species such as elephants or tigers. These respondents used terms such as “treasure” and “ornament” to describe wildlife which add “beauty” to forest and make forest “lively place” to gain pleasure and happiness (). For example, respondent (#15) stated: “You will gain great pleasure through engagement with the forest and the animals therein, it can provide you with many experiences of pleasure, happiness and beauty” an expression of pro-conservation behavior. Our result show that not only do subsistence farmer’s livelihoods, but their happiness, depend on the quality of their environment and the co-occurrence of wildlife. Most respondents showed their awareness of the various wildlife’s ecological role and the processes which are vital to the continued survival and functioning of all species including humans, which can be seen in an example statement of a respondent: “We depend on forest and wildlife maintain the forest.” These findings suggest that even when wildlife are impacting negatively on livelihoods, human wildlife interactions can have positive aspects.

In contrast, herders’ negative attitude toward wildlife extended to proposed mitigation measures for HWC. They expressed a willingness to support predator population control (), especially that of the Asiatic wild dog. Most herders perceived that the population of wildlife has increased since the establishment of Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary. These herders were vocal about their resentment. They believed that managing HWC should be park’s responsibility. While they showed support toward Asiatic wild dog population control, being Buddhist, most of them noted that killing is not the right solution. For example, respondent (#7) stated:

All animals were once our parents or children or relatives. Killing them is equivalent to killing our own parents or children. This will bring us bad karma and make us to be born as animals in next life. It is better let the wild animals kill our yaks. Even if park officers do not see us killing wildlife, God will see us.

This result indicates that HWC may be leading to personal and community dissonance between societal religious beliefs and livelihood needs, especially amongst herders.

4. Discussion and Synthesis

4.1. Buddhist Beliefs, WVOs and HWC

This study aimed to identify WVOs in rural Bhutan and to better understand the relationships between Buddhist beliefs, WVOs, human attitudes, behaviors, and the implications of these relationships for HWC management. In Bhutan, Buddhism is the state religion and ~ 90% of the total population is Buddhist (Givel, Citation2015). Buddhist beliefs strongly influence Bhutanese culture, people, and government. Our results showed that rural farmers hold seven WVOs and Buddhist beliefs appear to have an influence on farmer’s WVOs, attitudes and behavior toward wildlife. However, these are modulated by utilitarian factors, which may be positive (in the case of the economic benefits of wildlife tourism (e.g., black necked cranes)) or negative (in the case of yak depredation by (Asiatic wild dog) where yaks are the primary livelihood source). The role of Buddhist beliefs was evident from most respondents’ positive attitudes toward wildlife, the willingness to support conservation and their commitment to refrain from retaliatory actions. Our findings showed that Buddhist beliefs in the protection of nature, in all its manifestations and the sanctity of life, has permeated most respondents’ consciousness and has become integrated into their value system. For example, “Do not kill” is one of the five precepts of Buddhism (Winzer et al., Citation2018) that has shaped how respondents respond to wildlife in a profound way. Fundamentally, respondents believe that the lives of all sentient beings are equally valuable. This deeply felt dedication to refrain from harming other living beings, an essence of Buddhism (Dorje, Citation2011) seems to mitigate against a whole host of deeds involving violence against all animals including wildlife (Gayley, Citation2017).

Similar findings about the role of religious beliefs have been reported in other countries. Farmers refrain from taking retaliatory action toward Himalayan black bear in Tibet (Liu et al., Citation2011) and Snow leopard in Northern India (Bhatia et al., Citation2017). Buddhism largely defines itself through the cultivation of compassion and striving to relieve the suffering of all living beings (Barstow, Citation2013). These findings indicate how Buddhist beliefs shape peoples’ attitudes toward wildlife, demonstrating that such beliefs may lie at the very core of human motivations to conserve wildlife.

Buddhist beliefs are also important tenets of local conservation. For instance, in our study, those respondents holding a “sacred” value orientation put strong value on their spiritual beliefs and were more tolerant of wildlife, but more so for those species with religious and cultural significance (e.g., Elephant and Tiger) than those with less significance (e.g., Asiatic wild dog). A similar study in Nepal found that, people were more tolerant of Snow leopard than the Tibetan wolves (Chetri et al., Citation2020) due to Buddhist beliefs and cultural values attached to the Snow leopard. These beliefs associated with Snow leopards have strong positive influence on their conservation (Li et al., Citation2014). These differences in valuing or disliking different wildlife species can have important impacts in terms of policy formulation for HWC mitigation.

In addition to the Buddhist beliefs, respondents judged wildlife species and supported their conservation in a variety of ways. These judgments largely depended on respondents’ WVOs that cause their behavioral intent to vary markedly. For instance, the positive attitudes toward wildlife species among respondents in Phobjikha were driven primarily by the utilitarian orientation. The income generated from homestay and farmers’ involvement in tourism related income generating activities (e.g., local guide and porters) have benefitted farmers and encouraged local guardianship of black necked crane (Yeshey et al., Citation2022). This touristic aspect of wildlife value is one of the wildlife values widely studied mainly from a non-consumptive wildlife tourism perspective (Chardonnet et al., Citation2002). Perceiving wildlife as beautiful can relate to supporting their protection as respondents with aesthetic value orientation generally have a very positive attitude about wildlife. Similar findings are reported in Kenya (de Pinho et al., Citation2014). This demonstrates that understanding the drivers of HWC requires nuanced analysis, looking into the details of why respondents behave the way they do.

4.1.1. Livelihoods, HWC and Attitudes

In relation to livelihood types, crop farmers, with more alternative livelihood options and less vulnerability to food insecurity, put stronger value on their religious beliefs which is shown through their positive attitudes toward wildlife. Livelihood diversification provides self-insurance, which reduces vulnerability in the same way to wealth (Choden et al., Citation2020). The positive attitude is also extended to what they saw as reasons contributing to wildlife raiding crops. Most respondents from Sarpang district believed that the damages or losses caused by wildlife is because of farmers’ encroachment into wildlife habitat while Haa and Wangduephodrang respondents considered wildlife foraging on crops due to lack of food for the wildlife in the forest.

In contrast, Yak herders largely held a negativistic value orientation and the attitude toward Asiatic wild dogs and reducing the number of this species is seen as a necessity, mainly through culling. While the higher economic losses caused by wildlife is the main explanation associated with negativistic WVO, this may be explained, in part, by the fact that these herders live at higher altitude and have fewer livelihood diversification options. For these herders, yak is not only a critical source of food, income, and financial stability, but is also a source of cultural identity. This evokes the negativistic value orientation, supporting the contention that mode of livelihood is an important factor in determining values (Talhelm et al., Citation2014). This led to personal and community dissonance between the need to adhere to societal religious beliefs and values, norms, and the need to provide for livelihoods. As Manfredo, Bruskotter, et al. (Citation2017) states “values are the result of human adaptation to different social and environmental contexts”. Herders’ negative attitudes and their readiness to support wildlife population control may be an adaptive strategy. Yet, many herders spoke of the need to refrain from retaliation because of the existing conservation laws and policies, demonstrating how conservation laws and policies shape people’s behaviors. An intolerance to HWC during the 1980s however led farmers to exterminate Asiatic wild dogs in parts of Bhutan (Thinley & Lassoie, Citation2013) highlighting that while herders spoke of abiding by the rules, negative attitudes toward wildlife can trigger retaliation. The prevalence of HWC, and the readiness of herders to support wild predator population control, could therefore have long-term consequences for wildlife but also farmers as pressures on livelihoods foster increased dissonance and lead to a degeneration of core Buddhist beliefs and values.

4.1.2. Policy Implications

Gross national happiness is the Bhutanese policy framework that aims to maximize people’s well-being and minimize suffering by balancing economic needs with spiritual and emotional needs and seeks to complement inner happiness with outer circumstances. HWC can be counteractive to achieving gross national happiness goals. Conservation efforts must focus on incorporating the needs and attitudes of people impacted.

Given the relationship between Buddhist beliefs, WVOs and attitudes of respondents toward wildlife, religious beliefs can provide policy makers with a way to engage in non-lethal measures but also develop other options such as ecotourism. Policy choices must capitalize on strengthening existing Buddhist beliefs while management strategies must focus on increasing the ability of households with a lower coping ability to absorb wildlife impacts. Further, policy makers must consider multi-faceted approaches that also address the social factors that contribute to the conflict. Innovative approaches, such as those applied in East Africa (Allan et al., Citation2017), that integrate more collective traditional grazing management with wildlife conservation and ecotourism, might reduce HWC and diversify income options where appropriate. Future research can look into the challenges respondents face living with wildlife and the potential solutions they envision to address those challenges as done in Laverty et al. (Citation2019).

5. Conclusion

This is the first study of WVOs, attitudes and HWC in Bhutan, where there is a strong Buddhist basis to society and governance. Buddhist beliefs are important in shaping respondents’ attitudes toward wildlife, with respondents indicating their religious belief system largely determined their WVOs. Kellert’s Typology of Biophilia Values were very useful in the context of Bhutan, although they were developed for very different contexts. Buddhist beliefs and values support wildlife conservation policy and drive conservation outcomes. WVOs, attitudes and behaviors toward wildlife were in part shaped by negative wildlife impacts, which was shown through the complex experience of herders who suffer dissonance between their religious beliefs and value orientations. The fear of punishment under current laws, is holding retaliation by those affected negatively by wildlife in check. The foundation of Buddhist beliefs may be at risk of degenerating as negative orientations come to dominate, leading to increased dissonance and a general lack of compassion toward wildlife. Increasing HWC, due to conservation policies, may therefore be impacting on centuries of harmonious coexistence between herders and wildlife. Future studies should examine spatial distribution of attitudes toward wildlife shaped by Buddhist beliefs and values in other countries where Buddhism is a dominant religion.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Melbourne Research Scholarship program granted by the University of Melbourne for providing funding support to the first author. We are grateful to all the participants involved in the household survey and focus group discussion. Our heartfelt gratitude to the Renewable Natural Resource staff of the four districts and eight sub-districts for facilitating the field work. We are also grateful to our reviewers for their insightful suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allan, B. F., Tallis, H., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Huckett, S., Kowal, V. A., Musengezi, J., Okanga, S., Ostfeld, R. S., Schieltz, J., Warui, C. M., Wood, S. A., & Keesing, F. (2017). Can integrating wildlife and livestock enhance ecosystem services in central Kenya? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(6), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1501

- Azungah, T. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. (2018). Qualitative Research Journal, 18(4), 383–400. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

- Barstow, G. (2013). Buddhism between abstinence and indulgence. Vegetarianism in the life and works of Jigmé Lingpa. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 20, 73–104. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/religion_fac/6

- Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., & Mishra, C. (2017). The relationship between religion and attitudes toward large carnivores in Northern India? Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2016.1220034

- Chardonnet, P., des Clers, B., Fischer, J., Gerhold, R., Jori, F., & Lamarque, F. (2002). The value of wildlife. Sci Tech Rev Off Int Epizoot, 21(1), 15–52. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.21.1.1323

- Chetri, M., Odden, M., Devineau, O., McCarthy, T., & Wegge, P. (2020). Multiple factors influence local perceptions of snow leopards and Himalayan wolves in the Central Himalayas, Nepal. PeerJ, 8: e10108. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10108

- Choden, K., Keenan, J. K., & Nitschke, R. C. (2020). An approach for assessing adaptive capacity to climate change in resource dependent communities in the Nikachu Watershed, Bhutan. Ecological Indicators, 114: 106293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106293

- Cohen, E. (2013). “Buddhist compassion” and “animal abuse” in Thailand’s Tiger Temple. Society & Animals, 21(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341282

- Coleman, T. J., III, Jong, J., & Van Mulukom, V. (2018). Introduction to the special issue: What are religious beliefs? Contemporary Pragmatism, 15(3), 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1163/18758185-01503001

- Dandy, N. E. (2005). Wildlife Values in International Conservation Policy [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Leicester.

- Dayer, A. A., Stinchfield, H. M., & Manfredo, M. J. (2007). Stories about wildlife: Developing an instrument for identifying wildlife value orientations cross-culturally. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701555410

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publication.

- de Pinho, J. R., Grilo, C., Boone, R. B., Galvin, K. A., & Snodgrass, J. G. (2014). Influence of aesthetic appreciation of wildlife species on attitudes towards their conservation in Kenyan agropastoralist communities. PLoS ONE, 9(2), 1–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088842

- Dorje, O. T. (2011). Walking the Path of Environmental Buddhism through Compassion and Emptiness. Conservation Biology, 256: 1094–1097.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01765.x

- Ford, R. M., Rawluk, A., & Williams, K. J. (2019). Managing values in disaster planning: Current strategies, challenges and opportunities for incorporating values of the public. Land Use Policy, 81, 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.029

- FRMD. (2017). Land use and land cover of Bhutan 2016, maps and statistics. Royal Government of Bhutan.

- Fulton, D., Manfredo, M., & Lipscomb, J. (1996). Wildlife value orientations: A conceptual and measurement approach. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1(2), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209609359060

- Gamborg, C., & Jensen, F. S. (2016). Wildlife value orientations: A quantitative study of the general public in Denmark. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 21(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2015.1098753

- Gayley, H. (2017). The compassionate treatment of animals: A contemporary Buddhist approach in Eastern Tibet. Journal of Religious Ethics, 45(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jore.12167

- Givel, M. (2015). Mahayana Buddhism and gross national happiness in Bhutan. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(2), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v5i2.2

- Jamtsho, Y., & Katel, O. (2019). Livestock depredation by snow leopard and Tibetan wolf: Implications for herders’ livelihoods in Wangchuck Centennial National Park, Bhutan. Pastoralism, 9(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-018-0136-2

- Kaczensky, P. (2007). Wildlife value orientations of rural Mongolians. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701555303

- Kansky, R., & Knight, A. T. (2014). Key factors driving attitudes towards large mammals in conflict with humans. Biological Conservation, 179, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.008

- Karanth, K. K., & Vanamamalai, A. (2020). Wild Seve: A novel conservation intervention to monitor and address human-wildlife conflict. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00198

- Karst, H. E., & Nepal, S. K. (2019). Conservation, development and stakeholder relations in Bhutanese protected area management. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(4), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1580628

- Kellert, S. R. (1993). The biological basis for human values of nature. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 42–69). Island Press.

- Laverty, T. M., Teel, T. L., Thomas, R. E., Gawusab, A. A., & Berger, J. (2019). Using pastoral ideology to understand human–wildlife coexistence in arid agricultural landscapes. Conservation Science and Practice, 1(5), e35. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.35

- Lawrence, M. F. (1969). Legal culture and social development. Law & Society Review, 4(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3052760

- Letro, L., Sangay, W., & Tashi, D. (2020). Distribution of Asiatic black bear and its interaction with humans in Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan. Nature Conservation Research, 5(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.24189/ncr.2020.004

- Liu, F., McShea, W. J., Garshelis, D. L., Zhu, X., Wang, D., & Shao, L. (2011). Human-wildlife conflicts influence attitudes but not necessarily behaviors: Factors driving the poaching of bears in China. Biological Conservation, 144(1), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.009

- Li, J., Wang, D., Yin, H., Zhaxi, D., Jiagong, Z., Schaller, G. B., Mishra, C., McCarthy, T. M., WANG, H., WU, L., XIAO, L., BASANG, L., ZHANG, Y., ZHOU, Y., & LU, Z. (2014). Role of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in snow leopard conservation. Conservation Biology, 28(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12135

- Madden, F. (2004). Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: Global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9(4), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490505675

- Madden, F. (2008). The growing conflict between humans and wildlife: Law and policy as contributing and mitigating factors. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy, 11(2–3), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880290802470281

- Manfredo, M. J., Bruskotter, J. T., Teel, T. L., Fulton, D., Schwartz, S. H., Arlinghaus, R., Oishi, S., Uskul, A. K., Redford, K., Kitayama, S., & Sullivan, L. (2017). Why social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservation. Conservation Biology, 31)4(4), 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12855

- Manfredo, M. J., & Dayer, A. A. (2004). Concepts for exploring the social aspects of human–wildlife conflict in a global context. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490505765

- Manfredo, M. J., Vaske, J. J., & Decker, D. J. (1995). Human dimensions of wildlife management: Basic concepts. In R. L. Knight & K. J. Gutzwiller (Eds.), Wildlife and recreationists: Coexistence through management and research (pp. 17–31). Island Press.

- Mcleod, E., & Palmer, M. (2015). Why conservation needs religion. Coastal Management, 43(3), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2015.1030297

- Minton, E. A., Kahle, L. R., & Kim, C. H. (2015). Religion and motives for sustainable behaviors: A cross-cultural comparison and contrast. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1937–1944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.003

- Negi, C. S. (2005). Religion and biodiversity conservation: Not a mere analogy. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management, 1(2), 85–96.

- Negi, C. S. (2005). Religion and biodiversity conservation: Not a mere analogy. International Journal of Offshore and Polar Engineering, 1(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451590509618083

- Niaura, A. (2013). Using the theory of planned behavior to investigate the determinants of environmental behavior among youth. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management, 63(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.erem.63.1.2901

- Nsonsi, F., Heymans, J.-C., Diamouangana, J., & Breuer, T. (2017). Attitudes towards forest elephant conservation around a protected area in Northern Congo. Conservation & Society, 151(1), 59–73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393271

- Penjor, D., Dorji, T., & Bhadauria, T. (2020). Circumstances of human conflicts with bears and patterns of bear maul injuries in Bhutan: Review of records 2015–2019. PLoS One, 15(8), e0237812. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237812

- Ponizovskiy, V., Grigoryan, L., Kühnen, U., & Boehnke, K. (2019). Social construction of the value–behavior relation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00934

- Reddy, S. M., Montambault, J., Masuda, Y. J., Keenan, E., Butler, W., Fisher, J. R., Asah, S. T., & Gneezy, A. (2017). Advancing conservation by understanding and influencing human behavior. Conservation Letters, 10(2), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12252

- Rinzin, C., Vermeulen, W. J., Wassen, M. J., & Glasbergen, P. (2009). Nature conservation and human well-being in Bhutan: An assessment of local community perceptions. Journal of Environment & Development, 18(2), 177–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496509334294

- Sangay, T., & Vernes, K. (2008). Human–wildlife conflict in the Kingdom of Bhutan: Patterns of livestock predation by large mammalian carnivores. Biological Conservation, 141(5), 1272–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.02.027

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

- Talhelm, T., Zhang, X., Oishi, S., Shimin, C., Duan, D., Lan, X., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 344(6184), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246850

- Tanakanjana, N., & Saranet, S. (2007). Wildlife value orientations in Thailand: Preliminary findings. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701555519

- Thinley, P., & Lassoie, J. P. (2013). Human-wildlife conflicts in Bhutan: Promoting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods in Bhutan. Conservation Bridge.

- Tobgay, S., Wangyel, S., Dorji, K., & Wangdi, T. (2019). Impacts of crop raiding by wildlife on communities in buffer zone of Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, Bhutan. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 7(4), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v7i4.fe01

- Ver Beek, K. A. (2000). Spirituality: A development taboo. Development in Practice, 10(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520052484

- Wangchuk, N., Pipatwattanakul, D., Onprom, S., & Chimchome, V. (2018). Pattern and economic losses of human-wildlife conflict in the buffer zone of Jigme Khesar Strict Nature Reserve (JKSNR), Haa, Bhutan. Journal of Tropical Forest Research, 2(1), 30–48.

- Winzer, L., Samutachak, B., & Gray, R. S. (2018). Religiosity, spirituality, and happiness in Thailand from the perspective of Buddhism. Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS], 26(4), 332–343. https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv26n4.023

- Yangka, D., Devereux, P., Newman, P., & Rauland, V. (2018). Sustainability in an Emerging Nation: The Bhutan Case Study. Sustainability, (10), 5.https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051622

- Yeshey. (2023). Survey questionnaire for understanding social, economic, and environmental dimension of human wildlife conflict (Version 2). figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23528889

- Yeshey, Ford, R. M., Keenan, R. J., & Nitschke, C. R. (2022). Subsistence farmers’ understanding of the effects of indirect impacts of human wildlife conflict on their psychosocial well-being in Bhutan. Sustainability (Switzerland), 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114050

- Yeshey, Keenan, R. J., Ford, R. M., Nitschke, C. R. (2023). How does conservation land tenure affect economic impacts of wildlife: An analysis of subsistence farmers and herders in Bhutan. Trees, Forests and People, 11, 100378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2023.100378

- Zinn, H. C., & Shen, X. S. (2007). Wildlife value orientations in China. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 12(5), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200701555444