ABSTRACT

This study assessed the nature and local people’s perceptions of human-crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) conflicts (HCCs) for the period 2007 to 2016 in Kariba town, northern Zimbabwe. A mixed-method approach was used with 150 local fish folks interviewed between July and October 2017 through face-to-face interviews and secondary data on HCC were retrieved from the wildlife authority’s records. In contrast to the general perception from fish folks that there was an increase in HCC, secondary data analysis showed no significant trends of crocodile attacks on people for the period under study. HCC was mainly driven by fishing activities which exposed people to crocodile attacks. The study concludes that despite the recorded non-increasing trend in HCCs, HCC is a major conservation issue in Kariba town given enhanced human–wildlife interactions due to the economic needs for local livelihoods. Community educational programs are recommended as a way to manage HCC and close gaps between the conventional scientific and local knowledge.

Introduction

In Africa for the past three decades, human settlements close to large water bodies have grown at a rate of about 3% per annum, partly because of migration of people displaced by drought conditions, and by economic and political upheavals (Muringai et al., Citation2020). Inadvently, this has increased water-related livelihood activities, thus escalating human-crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) conflicts (HCCs), especially in areas where the two exist together. For this study, HCC is defined as any human and crocodile interaction that results in negative effects on human social, economic or cultural life, or on the conservation of crocodilian species and their habitats (Porras Murillo & Cambronero, Citation2020). These conflicts may result when crocodiles injure or kill domestic animals or people, or when humans encroach into crocodile territory (IUCN International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Citation2004). The HCC can be real or perceived and may be associated with some ecological, social, economic, and political factors (Porras Murillo & Cambronero, Citation2020).

Crocodile attacks on humans have been well documented in developed countries in the last few decades, whilst attacks in developing countries are poorly documented despite having the highest incidences of HCC (Sideleau & Britton, Citation2013). Many crocodile attacks on humans are less reported in Africa, and without an accurate reporting system in place, these attacks are difficult to track (Anderson & Pariela, Citation2005). Crocodiles are potential human eaters and are adapted to a wide distribution range (Sindaco & Jeremcenko, Citation2007), hence are found in different types of ecosystems.

HCC is a growing problem in Kariba town, a tourist resort located in northern Zimbabwe. There are reports of an increase in crocodile attacks on humans especially fishers over the years (Muringai et al., Citation2020), as Lake Kariba is the largest water body in Zimbabwe, with the fishing industry in Kariba employing more than 5,000 people (ZPWMA Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Citation2015). Due to recent socio-economic challenges experienced in the country, most people in Kariba resorted to fishing to supplement their income (ZimVac Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2020). As these local fishers ventured into lake shore waters for a better catch, they found themselves in conflict with crocodiles. It is essential that an understanding of the key factors and perceptions of people that have a bearing on the HCC in Kariba come up with appropriate prevention and mitigation measures. This study sought to (i) establish the nature and trends of HCC cases in Kariba town for the period 2007–2016 and (ii) determine the local people’s perceptions and attitudes toward crocodiles in Lake Kariba.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

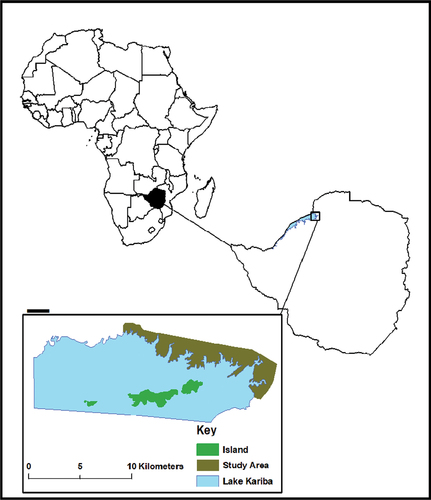

The study was conducted in Kariba town, which is adjacent to Lake Kariba, northern Zimbabwe () and had a human population of about 26,500 people in 2012 (ZimStats Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency, Citation2012). Lake Kariba is a man-made lake that was developed by the impoundment of the Zambezi River at the Kariba Gorge (ZPWMA Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Citation2015). The primary function of the lake is to provide hydroelectricity for Zambia and Zimbabwe that jointly own the lake (Magadza, Citation2006). Lake Kariba has a catchment area of 663,848 km2 extending over parts of Angola, Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe (Marshall, Citation1987). The climate of Kariba town is predominantly semi-arid with mean annual temperatures of 28°C and mean annual rainfall and evaporation of 766 mm and 1700 mm, respectively (ZPWMA). Lake Kariba’s riparian vegetation is dominated by mopane (Colophospermum mopane). However, the highland and escarpment areas consist of typical Miombo woodland on shallow gravel soils dominated by the Prince of Wales’ feathers (Brachystegia boehmii) and mnondo tree (Julbernardia globiflora).

The lake is home to large populations of crocodiles and hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). A fish survey along the Zimbabwe’s shore of Lake Kariba recorded 33 fish species of 10 families. The most dominant fish species include bream (Tilapia sparrmanii), kapenta (Limnothrissa miodon), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), purple face largemouth (Serranochromis macrocephalus), and slender barb (Barbus unitaeniatus) (Moyo, Citation1990). However, the fish population is reportedly declining due to both overfishing and reduced volume of water as the climate changes toward high frequencies of dry spells and droughts (ZPWMA Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Citation2015).

Data Collection

The target population in Kariba town for this study was a section of local fish folks who used rods and lines for fishing in Lake Kariba since these were the very people who were normally faced with the challenge of crocodile attacks. A sample of 150 fish folks (10%) was randomly drawn from a population of about 1,500 registered people practicing fishing as a livelihood activity at the household level in Kariba (ZPWMA Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Citation2015). A mixed-method research approach was used with primary data collected between July and October 2017 through face-to-face interviews conducted by the first author and research assistants using a semi-structured questionnaire that covered the following questions or thematic areas: socio-demographics, crocodile threats in the study area, causes or drivers of crocodile attacks, known cases, patterns, trends, seasonality and characteristics of crocodile attacks, actions taken when attacks occurred, and perceptions and attitudes of respondents to crocodiles and their management. Each interview took on average 20 minutes and clearance to conduct the study was granted by the Chinhoyi University of Technology and Kariba local authority. Further, secondary data on HCC in and around Lake Kariba for the period 2007 to 2016 were retrieved from the law enforcement and human wildlife conflict records kept at ZPWMA’s stations in Kariba.

Data Analysis

The collected survey data were tabulated in Microsoft Office Excel 2013. Simple linear regression analysis was used to determine trends in crocodile attacks over time using STATISTICA version 10 for Windows (StatSoft, Citation2010). Further, descriptive statistics were used to describe people’s perceptions and attitudes toward crocodiles.

Results

Characteristics of Study Respondents

The study sample comprised 53.3% (n = 80) males and 46.7% (n = 70) females. Twenty percent (n = 30) of the respondents were youths of 18–30 years of age, 72% (n = 108) of study respondents were adults of 31–60 years of age, whereas, 8% (n = 12) of study respondents were the elderly of over 60 years of age. Most study respondents were educated with 64% (n = 96) having attained secondary education, while 29% (n = 43) had acquired primary education and 1% (n = 2) had attained tertiary education. However, 6% (n = 9) of study respondents had no formal education. In terms of employment, 33% (n = 49) of study respondents were formally employed in the fishing industry, 15% (n = 23) of the study respondents were involved in fishing on a part-time basis, while they were also employed full time in the tourism industry, 3% (n = 5) were fully employed in the wildlife industry, and 23% (n = 34) were fully employed in other businesses while engaging in fishing as part-time work, 26% (n = 39) of the study respondents were not formally employed as they full time engage in fishing in Lake Kariba.

Nature and Trends of HCC Cases in Kariba Town

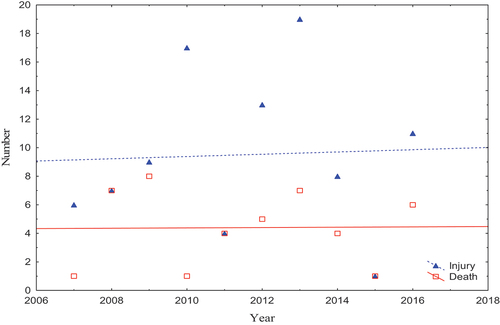

Between 2007 and 2016, there was a record of 48 (40 males and 8 females) people killed by crocodiles, and 95 (75 males and 20 females) people injured by crocodiles in Kariba town. Overall, the results from the secondary data analysis showed that there were no significant trends of people injured (y = 0.08x − 148.98; r2 = 0.002; p = .907) and killed by crocodiles (y = 0.01x − 19.98; r2 = 0.0002; p = .970) () over the study period. In contrast, most study respondents perceived that there was an increase in HCC with 89% (n = 133) indicating that crocodiles attacked and sometimes killed people, whereas 9% (n = 14) did not confirm the existence of crocodile attacks on people. However, only 2% (n = 3) of study respondents did not know whether the HCC existed or not.

Local People’s Perceptions on HCC and Attitudes Towards Crocodiles in Kariba Town

Most of the study respondents, 82% (n = 123) perceived an increase in crocodile population in Lake Kariba for the period 2007 to 2016, whereas 13% (n = 19) of the respondents highlighted a decline, whilst 5% (n = 8) of the respondents indicated no change in crocodile population for the same period. The main reasons given for the population increase of crocodiles were as follows: (i) crocodiles were breeding at a faster rate, (ii) there was no culling of crocodiles by the ZPWMA, and (iii) crocodiles were escaping from crocodile farms into Lake Kariba. The reason given by those respondents who claimed crocodile population was decreasing was that crocodiles were being captured and translocated by the wildlife authority, and the reason for no change in crocodile population size was also that crocodiles were being captured and translocated.

The majority of study respondents (85%; n = 121) believed that people got attacked while fishing in Lake Kariba, whereas 3% (n = 5) of the respondents indicated that the people were attacked while bathing, 8% (n = 12) of the respondents perceived that the people were attacked whilst they were fetching water, and 4% (n = 5) of the respondents highlighted that the people were attacked whilst they were undertaking other activities in Lake Kariba. About 61% (n = 92) of the respondents indicated that males were mostly attacked by crocodiles, while only 3% (n = 4) of the respondents indicated that females were mostly attacked, and 36% (n = 54) of the respondents highlighted that both males and females were equally attacked.

There were mixed responses on why people continued to fish even though people were constantly being attacked. Seventy-one percent (n = 107) of the respondents attributed this to poverty explaining that people had no other sources of livelihood, and so they mostly relied on fishing even though they knew that fishing was risky and dangerous. Twenty-five percent (n = 38) of the respondents were of the view that it was because of unemployment that people relied on risky fishing to earn income. One percent (n = 1) of the respondents highlighted that they were into fishing for relish and 3% (n = 4) of the respondents indicated that they were into fishing for leisure.

Respondents had different attitudes toward the conservation of crocodiles in Lake Kariba. About 34% (n = 51) of the respondents highlighted that they liked the conservation of crocodiles, while the majority (66%, n = 99) expressed their dislike of the conservation of crocodiles in Lake Kariba. Reasons for liking the conservation of crocodiles were highlighted to include: (i) that they brought revenue for the country through tourism and (ii) they were a natural resource, which could be sold to generate revenue for the country. On the contrary, the main reason given for disliking the conservation of crocodiles was that crocodiles killed and injured people.

Study respondents had different perceptions on how to manage HCC in Kariba town. Fourteen percent (n = 21) of the respondents suggested that the wildlife authority could consider killing all the problem crocodiles in Lake Kariba. This study found out that most people would report incidences of problem crocodiles to ZPWMA instead of killing them. On the other hand, 26% (n = 39) of the respondents suggested that the large crocodiles need to be captured and translocated to other distant places, and 7% (n = 11) of the respondents suggested that ZPWMA could sell some of the larger crocodiles since they were the ones causing problems. However, more than half of the study respondents, 53% (n = 79) suggested that people need to be educated so that they become aware of the dangers posed by crocodiles as well as to be able to co-exist with crocodiles.

Discussion

The study results showed that although there was a perceived increase in the number of HCC, trend analysis of the secondary data revealed that there were no significant increases in crocodile attacks in terms of injury and fatalities to local communities between 2007 and 2016. This points to the local community attributing HCC trends to perceived crocodile increases, no culling of crocodiles and HCC incidences in Kariba town. Generally, it has been reported that there has been a recovery and increase in wild crocodile populations, a species that was previously threatened with extinction, in Zimbabwe due to successful conservation methods and protection implemented in the country (Muringai et al., Citation2020) associated with measures put in line with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). However, in Zimbabwe, Nile crocodiles have also been reported to have become a serious threat to humans due to their increasing population sizes (Ndhlovu et al., Citation2017). Of note, though, there is need to have the scientific information on crocodile attacks also shared with local communities and policy makers to allow for informed decision-making as only relying on local knowledge would not provide the full scale of HCC in the study area.

This study results highlighted that HCCs were perceived to be influenced by the extent of fishing with people being perceived to be getting further into the lake and secluded habitats to get enhanced chances of fish harvests, which leads to fishers being exposed to crocodile attacks. Fish is a primary food source and an income for families, and part of a way of life in Kariba town (Ndhlovu et al., Citation2017). Fishers are bound to meet crocodiles more frequently when they get into Lake Kariba. The injury and/or killing of an active working-class member of a household from crocodile attacks can cause food insecurity and livelihood loss among vulnerable urban households in Zimbabwe (Gwetsayi et al., Citation2016; ZimVac Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2020). The death of the breadwinner to a poor family in a developing country can mean the difference between a secure life for all and one of destitution where day-to-day survival becomes a life’s priority. The loss of the mother of a family will mean that a child must take her place doing family chores and that the opportunity of an education for that child may be lost (FAO, Citation2005).

The study recorded that most respondents from Kariba town had negative attitudes toward the conservation of crocodiles, and this stemmed from the fact that the crocodile was considered as a dangerous reptile that injures and kills people. Only a few respondents reportedly liked crocodile conservation in Kariba town. Pooley et al. (Citation1992) stated that human dislike of crocodiles is influenced by memories or personal experiences of attacks and stories that are passed on in different groups of people about the demerits of crocodiles. Accordingly, the crocodiles are disliked by most people especially fishers due to the threat to life when fishing (Pooley et al., Citation2021).

The study recorded that to mitigate the problem of HCC in Kariba town, most respondents suggested that people need to be educated on crocodile behavior, while others suggested that “problem” crocodiles be translocated to protected set-ups, not in proximity to people. The removal of crocodiles from conflict hotspots was a widely suggested solution to reduce the number of attacks and this corroborated with an earlier study in Australia that cited this approach as an effective technique in dealing with HCC (Nichols & Letnic, Citation2008). Thus, the capture and relocation or removal of “problem” crocodiles to crocodile farms could be beneficial as the crocodiles will not trek their way back to their original habitat. Conservation education and awareness campaigns would benefit local people who could transform and have a positive attitude toward wildlife management in which crocodile conservation is also included (Pooley et al., Citation2021). Enhancing the HCC response strategy and community engagement at the human–wildlife interface would allow for effective means of addressing human wildlife conflicts, in particular, HCC. Further, sharing of HCC information among key stakeholders allows the local community to better interact with wildlife and close the gap between scientific information and local knowledge. Interventions that address the major drivers of HCC such as limited economic opportunities, poverty and maximize on the natural heritage economic opportunities are essential such as wildlife, aquaculture, and agro-based community projects that diversifies economic activities in areas adjacent to Lake Kariba needs to be explored as these would reduce overdependence on fishing within the lake, hence, reduce the extent of HCC.

Conclusion

This study recorded a non-significant trend in HCC in Kariba town between 2007 and 2016, in contrary to the perceived increase of HCC by the respondents. The major driver of HCC was highlighted to be increasing fishing practices that exposed people to crocodile attacks in Lake Kariba. Generally, most respondents had a negative attitude toward the conservation of crocodiles, and this stemmed from the fact that crocodiles were considered as a dangerous reptile that injures and kills people. It is hereby recommended that there is need to (i) enhance the conservation education and awareness programs to assist with closing the gap between scientific and local knowledge and manage HCC and (ii) initiate diversified community projects that reduce over-dependence on the fishing in Lake Kariba.

Ethics statement

The informed consent was obtained from all participants and the institutional research committee from the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority approved the study.

Policy Highlights

There is an increasing concern in Zimbabwe in relation to human-crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) conflict.

Major driving factors for Human-Crocodile Conflicts (HCC) are fishing activities which exposes people to crocodile attacks in Lake Kariba.

Increase in human population, unemployment, and poverty is perceived to have increased pressure on the utilization of aquatic natural resources and hence exacerbates HCC.

In contrast to the general perception from fish folks that there was an increase in HCC, information from the local wildlife authority showed no increasing trends of crocodile attacks on people in Kariba town.

Community educational programs are necessary in Zimbabwe as a way to manage HCC and close gaps between the conventional scientific and local knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority for granting permission for us to undertake the study. Special thanks go to Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute for logistical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, J., & Pariela, F. (2005). Strategies to mitigate human-wildlife conflict in Mozambique. Mozambique National Directorate of Forests and Wildlife.

- FAO. (2005). Strategies to mitigate human-wildlife conflict in mozambique (J. Anderson & F. Pariela, Ed.). Report for the National Directorate of Forests & Wildlife. FAO.

- Gwetsayi, R. T., Dube, L., & Mashapa, C. (2016). Urban horticulture for food security and livelihood restoration in mutare city, Eastern Zimbabwe. Greener Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3), 056–064. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJSS.2016.3.082116130

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature. (2004). Benefits beyond boundaries: Proceedings of the Vth IUCN World parks congress. IUCN. Retrieved September 1–17, 2003.

- Magadza, C. H. D. (2006). Environmental state of Lake Kariba and Zambezi river valley: Lessons learned and not learned. Lakes & Reservoirs: Science, Policy and Management for Sustainable Use, 15(3), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1770.2010.00438.x

- Marshall, B. E. (1987). Catch and effort in the Lake Kariba sardine fishery. Journal of the Limnological Society of Southern Africa, 13(1), 20–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03779688.1987.9634539

- Moyo, N. A. G. (1990). The inshore fish yield potential of Lake Kariba. Africa Journal of Ecology, 28(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.1990.tb01155.x

- Muringai, T. R., Naidoo, D., & Mafongoya, P. (2020). The challenges experienced by small-scale fishing communities of Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 16(1), a704. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.704

- Ndhlovu, N., Saito, O., Djalante, R., & Yagi, N. (2017). Assessing the sensitivity of small-scale fishery groups to climate change in Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe. Sustainability, 9(12), 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122209

- Nichols, T., & Letnic, M. (2008). Problem crocodiles: Reducing the risk of attacks by Crocodylus porosus in Darwin harbor, Northern Territory, Australia. In R. E. Jung & J. C. Mitchell (Eds.), Urban Herpetology. Herpetologial Conservation (Vol. 3, pp. 509–517). Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles .

- Pooley, A. C., Hines, T., & Shield, J. (1992). Attacks on humans. In C. A. Ross (Ed.), Crocodiles and Alligators (2nd ed., pp. 172–185). Blitz Editions.

- Pooley, S., Siroski, P. A., Fernandez, L., Sideleau, B., & Ponce-Campos, P. (2021). Human–crocodilian interactions in Latin America and the Caribbean region. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(5), e351. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.351

- Porras Murillo, L. P., & Cambronero, E. M. (2020). Analysis of the interactions between humans and crocodiles in Costa Rica. South American Journal of Herpetology, 16(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.2994/SAJH-D-18-00076.1

- Sideleau, B. M., & Britton, A. R. C. (2013). An analysis of crocodilian attacks worldwide for the period of 2008 - July 2013. In: Proceedings of the World crocodile conference, 22nd working meeting of the IUCN-SSC crocodile specialist group, Negombo, Sri Lanka. Retrieved May 21-23, 2013.

- Sindaco, R., & Jeremcenko, V. K. (2007). The reptiles of the Western palearctic 1. Annotated checklist and distributional atlas of the turtles, crocodiles, amphisbaenians and lizards of Europe, North Africa, Middle East and Central Asia. Edizioni Belvedere.

- StatSoft. (2010). STATISTICA for windows, version 10. StatSoft Inc.

- Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency. (2012). Population census: Zimbabwe main report. ZimStats.

- Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. (2015). Status of wild crocodile population in zimbabwe. ZPWMA.

- Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee. (2020). 2020 Urban livelihoods assessment technical report. Food and Nutrition Council of Zimbabwe, Government of Zimbabwe.