ABSTRACT

Background: Universities are facing increased budget constraints, often resulting in reduced funds to support microbiology laboratories. Online mock laboratory activities are often instituted as a cost-effective alternative to traditional wet labs for medical students.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to examine students’ perceptions of online and in-person microbiology lab learning experiences.

Design: We investigated undergraduate medical student perception of the in-person and online microbiology lab experience; 164 first-year medical students participated in newly designed online labs, while 83 second-year medical students continued to use in-person labs. An online survey was administered to collect student opinions of the lab experience.

Results: In terms of student self-reported learning styles, those students who attended the lab in person were more likely to report a tactile learning style (33% vs 16%) while those students who learned the material online reported a visual learning style preference (77% vs 61%; n = 264). Students felt that the online microbiology lab was more convenient for their schedules when compared to the in-person lab. A greater proportion of online students (12%) felt that they encountered brand-new material on the final quiz than in-person students (1%; n = 245). Even so, 43% of the online educated students and 37% of the in-person educated students perceived their assigned lab experiences to be the optimal lab design, and over 89% of both groups reported a desire for at least some in-person instruction in a wet-laboratory environment.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that, while students are strongly supportive of digital online lab activities, the overwhelming majority of students still report a desire for a blend of online and in-person, hands-on laboratory activities. These findings will further research directed towards student perception of the lab experience and aid in the adaptation of microbiology curriculums to accommodate both student and university needs.

Introduction

Laboratories provide students with a stimulating learning environment to acquire and develop practical skills which are otherwise unattainable through lectures and readings. The evaluation of laboratories is critical for educators to develop a well-rounded microbiology curriculum. Over the last two decades, laboratory instruction has undergone dramatic changes to both structure and frequency due to assessments of educational quality. Advancements in technology have led to the expansion of instruction from traditional methods (i.e., in-person labs) to online learning (i.e., online labs, virtual patients). Online labs attract attention from medical schools when they appear to better satisfy institutional needs, often leading to a reduction or elimination of in-person labs. These recent changes in microbiology education impact student perception of their learning experience depending on the efficiency, quality, and preconceived opinions of the lab experience.

Characteristics of in-person labs

In-person labs provide an opportunity for students to learn in a hands-on environment alongside peers and an instructor [Citation1]. A study by Salter and Gardner found that students prefer to receive face-to-face feedback from instructors when compared to receiving feedback via email [Citation2]. Students generate a sense of responsibility from directly handling and observing specimens [Citation1,Citation2], and student collaboration within the laboratory promotes an appreciation for the laboratory and fosters metacognition [Citation1,Citation3]. Increased interpersonal interactions with faculty and peers can also reportedly lead to increased intrinsic motivation and can foster additional learning experiences in the form of face-to-face feedback [Citation4]. However, due to the costs of lab equipment and supplies, construction, safety, and instructor availability and salary, medical schools have been reducing the use of in-person labs [Citation5]. A 2014 study found a 21% reduction (from 85% to 64%) of in-person labs offered by 70 medical schools between 2002 and 2012 [Citation6]. A more recent, subsequent survey of 104 schools found that only 54 (52%) utilized in-person lab-based methods, and the use of online learning modules was reported more frequently by 58 schools (57%) [Citation7].

Characteristics of online labs

An increasing number of studies have found the versatility of online learning to be a convenient, cost-effective approach to education [Citation8,Citation9]. Students can access online labs from any location, eliminating the cost for lab space and materials [Citation9,Citation10]. Additionally, online exercises give students the ability to attempt exercises multiple times, a feature too expensive and strenuous for in-person labs [Citation5]. Another study found that the ability to reattempt exercises was received positively by students, further supporting its cost-effectiveness [Citation11]. However, the low cost may be relative to the educational level and area of coursework [Citation12]. Higher levels of education in certain departments may require more detailed, expensive simulations. Regardless of these costs and benefits, the findings of Southwick et al. assert that instructors are recommended to use labs (online or in-person) as the primary method of case discussion learning [Citation13].

Characteristics of blended learning

Blended learning integrates components of online and in-person learning, thereby closing the gap between financial and faculty limitations and student learning preferences or requirements.

Studies have found that assigning students online labs prior to lab exercises or tests improved students’ confidence and motivation to learn [Citation14,Citation15]. Similar to online labs, the structure of blended learning offers a greater component of accessibility than in-person labs, while also providing face-to-face instruction. However, the creation of online lectures, assignments, or supplemental materials need to be interactive and provide feedback for the in-person component to be successful [Citation16,Citation17]. In a recent study, students preferred the structure of blended learning to a solely in-person course, citing variances in the specific instructor, time and location as drawbacks to in-person courses [Citation18]. Subsequently, instructors have used blended learning as both the design of a course and a preparation method or complement to physical labs [Citation12,Citation16]. Nevertheless, Sancho et al. stress that blended learning is unique to every course [Citation12].

Characteristics of case studies

Similar to online and blended learning, case studies have grown in popularity due to their interactivity. Furthermore, they may be available online or in-person, depending on the course content, rendering them cost-effective [Citation5,Citation10]. Online case studies provide medical students with multiple opportunities to exercise their skills on patients from any location [Citation10]. A study by Blewett and Kisamore found that students who participated in a case-based review session before an exam perceived it to be helpful and reported elevated exam scores [Citation8]. It should be noted that according to a recent survey, medical schools are replacing in-person labs with small case studies and activities, namely due to budget constraints, reduced teaching hours, and curriculum changes [Citation6].

Student performance

The efficiency of online learning has been reported to be equivalent, or superior to that of in-person learning [Citation13,Citation14,Citation19]. In a recent study, students performed similarly in online and in-person labs, but the study reported certain benefits from the online labs, such as reduced instruction time, reduced faculty/staff time, and greater intrinsic motivation by students [Citation14]. Students who used either a wet-lab (in-person) or virtual lab (online) experienced increases in both knowledge and self-efficacy in microbiology. Sancho et al. found that, in addition to performing similarly in online and in-person labs, the majority of students also reported the online lab to be an integral part of the course [Citation12]. Both studies concluded that an optimal curriculum would consist of blended learning: a balance of online and in-person lab exercises. Other studies have also concluded this integrated learning format to be a superior learning method [Citation13–Citation15,Citation19].

Student perception

Microbiology online learning studies have tended to focus on student performance as the primary objective [Citation3,Citation13,Citation14]. However, it is critical to also examine student perception of laboratory learning, especially considering the high levels of stress and depression that medical students are experiencing [Citation20–Citation22]. Preconceived student opinions towards online learning may positively or negatively impact the benefits. For instance, cohorts who have a positive opinion of online learning can make a positive impact on current and future students’ perceptions of those resources [Citation23]. Salter and Gardner’s study evaluating undergraduate perspectives reached the conclusion that students prefer only some elements from the two lab formats; utilizing online learning as a preparation tool for other learning activities may improve students’ perceptions of learning [Citation2]. Demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age) are another factor that may influence student perceptions of learning methods [Citation1,Citation5]. Lastly, some students may perceive an online learning experience as more convenient for their schedules due to the inherent flexibility while others may desire more structure. The benefits offered by either lab for a growing diverse group of students are another motivation to implement blended learning.

Objective of this study

We surveyed first and second-year undergraduate medical students for the duration of one academic year. The purpose of this study was to examine the students’ perceptions of online and in-person microbiology lab learning experiences. The results will be used to review the microbiology component of the medical student curriculum and better serve incoming medical students.

Materials and methods

Description of microbiology laboratory teaching experiences

During the time of data collection for this study, the discipline of microbiology was taught within a systems-based curriculum and was a component of most organ system courses throughout the first two (preclinical) years of the medical curriculum at Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences (KCU). According to a recent report, 45% of medical schools surveyed have similar microbiology curricula with some integration of microbiology within organ systems [Citation7]. There were eleven microbiology laboratory teaching sessions during the first two years of the medical curriculum spread throughout the organ system courses. Most courses contained at least one microbiology laboratory activity (some contained more than one). For this research study, labs were offered in one of two formats: in-person (also known as wet labs) or online (otherwise known as dry labs).

In-person wet labs

Students in this cohort were second-year medical students, and they attended a total of 4, 2-hour-long ‘wet’ in-person microbiology labs scattered throughout the year, where they were exposed to medical microbiology content at a number of pre-set stations. This had been their laboratory format for their first year of medical school as well. Each station contained a written clinical case, a microscope, organism specimen(s), and other relevant clinical or microbiological information (such as test results). Following small group participation to solve each case at each prepared station, students were expected to individually complete a worksheet containing a series of facts and questions related to each case, which was theirs to keep (worksheets were not graded). Points for the activity were earned by completing a nine-question online quiz within 5–7 days following the lab, which consisted of questions reflecting content derived from the lab. These quizzes were timed and students were provided their scores immediately following completion of the quiz. Correct answers were provided after the closing of the quiz to allow students to use for formative assessment purposes.

Online dry labs

Students in this cohort received a total of 5 online ‘dry’ digital labs throughout their first year of medical school. All of the content previously delivered in-person was moved online into the medical school’s learning management system. Digital microbiology laboratory stations were created based on the in-person lab stations, and contained a clinical case and other relevant clinical or microbiological information (such as test results). The digital station also contained images of specimen from a typical microscopic field of view with the magnification listed. Similar to the in-person microbiology lab experience, students were provided with a worksheet containing facts and questions for each case. Students were allotted up to one week of unlimited access to view the online microbiology lab, which was available when an in-person lab would have normally been offered within the course, and students could complete the online activity any time throughout the designated week. Similar to the in-person experience, students were expected to complete the worksheet questions, and points were earned by completion of a nine-point online quiz. The quiz was available for the entire time that the lab was available for viewing online and the quiz was closed 5–7 days following the first available viewing time for the online lab. Similar to the in-person labs, the quizzes were timed and students were provided their scores immediately following quiz completion. Correct answers were similarly provided to students after the closing of the quiz to allow students to use for formative assessment purposes.

Survey instrument development

A survey was developed to examine student perceptions of the microbiology laboratory experiences. The second-year medical students were administered all of their microbiology labs as in-person experiences, while the first-year students received labs entirely as online experiences. All students were asked to complete the same survey while reflecting on their own experience in the microbiology lab (in-person or online). The survey consisted of 14 questions ranging from perceived learning style to attitude towards blended style of curriculum (complete list of questions in ). All survey questions utilized multiple choice or Likert scale responses with one open-response question. The survey, advertisement and methods were approved by KCU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB study number 303626).

Table 1. Survey questions used in this study

Data collection

Data were gathered over one month from undergraduate medical students at KCU via an online third-party survey platform, surveymonkey.com (not associated with the medical school’s learning management system). Medical student participation in the survey was completely voluntary, responses were anonymous and did not influence grading, and no personal information was collected. The study was advertised by word-of-mouth, in-class announcements, and by campus email invitation. Subjects, which included students in the first and second year of medical school (classes of 2015 and 2014, respectively), volunteered to complete the online survey following online written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Data from the surveys were analyzed using SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Differences in proportions were analyzed using Chi-Square tests or Two Sample T-Tests. The assumptions of the Chi-Square tests were adequately met throughout.

Results

Student demographics and learning styles

We sought to describe medical student perceptions of the microbiology laboratory in two different teaching modalities: in-person (wet labs) and online (dry labs). Of the 500 students who had the opportunity to take the survey, 247 students completed it (49.4% response rate; ). In terms of age, 100 of the respondents (40.5%) were in the age range of 18–24 years, 140 (56.7%) were between the ages of 25–34, 6 students (2.4%) were 35 years or older, and one student did not give a response (0.4%) (, question 2). These age ranges closely mirror the overall age distribution of the student body. The majority of second-year medical students were aged 25 years or older (73%) and participated in the in-person microbiology labs. The students that learned the microbiology lab material online were in their first year of medical school and were, on average, younger at the time of data collection (only 53% were over the age of 25). There was no difference in the in-person and online student groups in terms of self-reported prior microbiology knowledge; nearly three quarters (71.7%) of students reported taking one or more college-level microbiology courses prior to entering medical school (, question 3).

Table 2. Summarized results from the survey

In terms of preferred learning format for new content, there was no significant difference when comparing the in-person and the online student groups (, question 4). Nearly 65% of students stated that they preferred in-person teaching (described on the survey as lecture and/or laboratory) when learning new content (66% of the online group and 61% of the in-person group) while only 35.2% stated that they preferred self-directed or online learning for learning new content ().

Students were asked to select their preferred primary study and learning format: study alone, study alone and then in a group, or study in a group (, question 6). There was no significant difference between the in-person and online groups with 53.5% (60% and 50%, respectively) preferring to study alone and then in a group, 43.5% (39% and 46%, respectively) preferring to study alone, and only 3.2% (1% and 4%, respectively) preferring to only study in a group (). We also found that students in both the online and in-person groups reported studying the lab material for approximately the same amount of time in order to prepare for the lab quiz, with most studying for less than one hour (, question 7). Additionally, both groups had similar perceptions regarding how well the microbiology lab reinforced the information/material from the classroom lecture (, question 10), with the majority of the students stating that the lab material either somewhat or completely reinforced the classroom material ().

Lastly, there was not a significant difference in responses between the two groups of students in terms of perception of value added by the microbiology lab to the medical school curriculum. The majority of students (90.2%) felt that the microbiology lab added some or a large amount of value to the overall curriculum, regardless of whether their microbiology lab experience was in-person (94%) or online (88%) (, question 13).

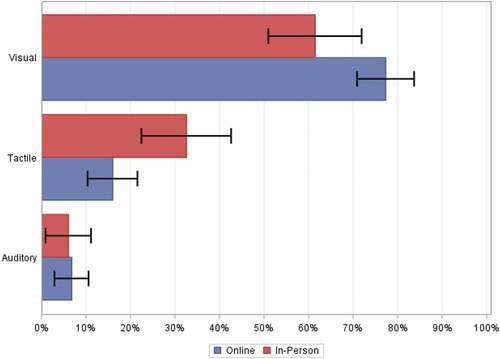

Student self-reported learning style: tactile for in-person and visual for online

Students were asked to report their desired current learning style and were given the choices of visual, auditory, or tactile (, question 5). As shown in , students who attended the in-person microbiology labs reported a greater preference towards a tactile learning style compared to students from the online microbiology lab group (33% vs 16%; p = 0.011; ). Conversely, students who learned the microbiology lab material online were more likely to self-report to prefer a visual learning style when compared to those students who attended the lab in person (77% vs 61%; p = 0.0112). Students who reported to be primarily auditory learners were the minority in both groups (7% of the online group, 6% for the in-person group).

Figure 1. Students’ self-reported learning style

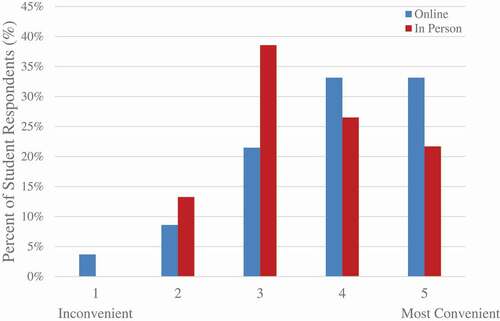

Convenience of online labs for students

Students were asked for their opinion regarding the convenience to their schedule of their assigned microbiology lab experience, rating the convenience factor on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 with 1 being ‘never convenient for my schedule’ and 5 being ‘always convenient for my schedule’ (, question 8). Students who learned the microbiology lab content online reported a higher level of convenience for their schedule when compared to the students who attended the in-person labs ( and ). High convenience ratings of 4–5 were provided by 66% of the online students compared with only 49% of students in the in-person group (p = 0.0096).

Figure 2. Student perceptions of the convenience of assigned lab teaching method

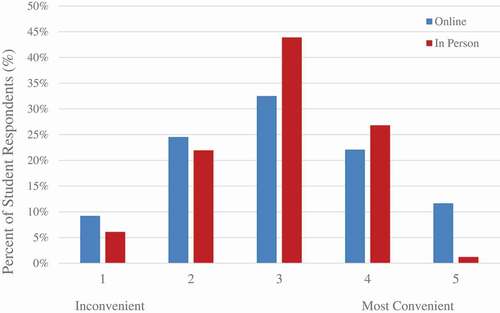

Online learners perceived content as new information

Students were asked how much new information they felt they had learned via their microbiology lab experience, using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 with 1 being ‘no new information was learned’ and 5 being ‘essentially all new information was learned’ (, question 9). As shown in , a larger proportion of students who participated in the online version of the microbiology lab reported that the lab contained essentially all new information (Likert scale of 5: 12%) compared to the students who attended the lab in person (Likert scale of 5: 1%) (p = 0.032) ().

Figure 3. Student perceptions of the amount of new information learned from assigned lab teaching method

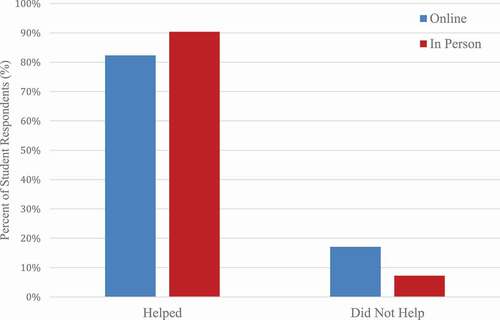

While student enjoyment was equivalent, students indicated in-person labs were more helpful

Students were asked a combined question of whether or not they found the microbiology lab experience to be enjoyable and helpful to their learning (, question 11). Overall, the level of enjoyment with the online and in-person microbiology lab experiences were mostly equivalent: 59% of online and 64% of in-person students reported to have enjoyed the lab (). However, more of the students who learned the material online felt that the lab did not help with learning microbiology-related material when compared to those students who participated in-person (17% vs 7%). In contrast, only 82% of students who learned the material online felt that the labs helped them to learn microbiology-related material, compared with 90% of students who participated in the lab in-person (; p = 0.038).

Figure 4. Student perceptions of helpfulness of assigned lab teaching method

Students preferred the lab format they were assigned over the alternative

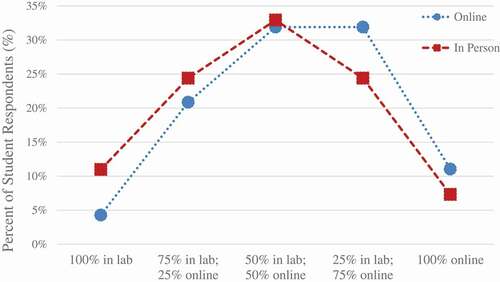

Finally, we asked students how they felt an ideal microbiology lab experience should be structured, with the possible answer choices being: 100% in-person, 75% in-person and 25% online, 50%-50% in-person and online, 25% in-person and 75% online, or 100% online (, question 14 and ). Overall, a greater proportion of students who learned the microbiology lab content online felt that the ideal lab experience would be more online (43%) than in-person (25%). Conversely, students who experienced the lab in-person felt that the ideal lab structure should be in-person (37%) when compared with online (30%). Approximately one-third of each group (32% online and 33% in-person) reported that an equal mixture of the two delivery methods would be the ideal structure for a microbiology lab experience. While these results are not statistically significant, even when we grouped the responses (see ), we believe that the trend is interesting (p = 0.097). Furthermore, 11% of the in-person students and 4% of the online students felt that the lab should be taught 100% in the lab ().

Figure 5. Student perceptions of optimal mix of ideal lab teaching methods

Discussion

This study investigated factors that may have affected undergraduate medical student perceptions of the lab experience. Previous research has primarily focused on the effectiveness of online and in-person labs, and have less frequently sought student opinions. The most influential factors that we identified included learning preference, convenience, helpfulness, and the amount of new material learned and reinforced. We surveyed 247 undergraduate medical students, 164 of whom were first-year students and 83 were second-year students. The first-year students participated in online microbiology labs while the second-year students continued to use in-person microbiology labs as they had experienced during their first year of medical school. The majority of students perceived their assigned lab experience as the ideal lab structure.

The difference in learning styles (defined here as visual, auditory, or tactile) between the online and in-person groups is reflective of the lab environment (). This preference was likely due to long-term exposure to a single lab method. These results are in accordance with Salter and Gardner’s findings that students appreciated the hands-on experience of in-person labs, but also valued the visuals unique to the online format [Citation2]. The particularly high score of online students in favor of visual learning (77%) confirms previous findings regarding the pivotal role of visuals in microbiology labs [Citation24]. These data further support Kay et al., who found that visual learning was the greatest benefit of the online lab experience [Citation25]. While it was outside of the scope of this study’s internal review board application, we noted no significant differences in aggregate quiz scores between the two groups at the completion of each lab quiz (data not shown).

In our findings, it was not surprising that the online group reported access to and utilization of the lab content to be more convenient than the in-person group (). This is in agreement with other studies’ findings of student preference towards flexible schedules [Citation2,Citation5,Citation24,Citation25]. A possibility for the report of high convenience may be explained by the online students’ week-long access to the lab content compared to the in-person students’ limited exposure of only two pre-scheduled hours, which is in agreement with previous research [Citation25]. Of interest, these data cannot be explained by a preference to study primarily alone due to both groups preferring to study alone, followed by group study (, question 6).

A larger number of students assigned to the online lab felt that they encountered completely new material during their experience (12%) than the in-person students (1%) (p = 0.032). This is important to note because both groups received the same material in lecture-format prior to the lab experience and that material was reinforced in the lab. However, due to limitations of our study design, the in-person group consisted of second-year students and therefore may have had a stronger knowledge of new material, potentially biasing our results. Indeed, convenient access to materials (i.e., the ability to access information from off-site locations at convenient/appropriate times) has been shown to enhance the ability to study new material [Citation24], a theory that is also supported by our findings. In addition, discomfort in the lab setting and desire for more immediate access to supplementary material may be contributing factors. In contrast, Salter and Gardner found that students felt more engaged in the learning process when able to physically interact with an instructor [Citation2]. It is important to note that both groups self-reported a similar amount of time spent studying for the quiz (, question 7). Due to these similarities, inadequate preparation by the online group is not a viable explanation for their higher perceptions of encountering new knowledge compared with the in-person group. Both groups of students reported in-person learning as their preferred method of learning new material (, question 4). This may explain the online students’ higher reports of encountering new knowledge than the in-person students.

The data concerning perceived helpfulness of labs (online 82% and in-person 90%, p = 0.032, ) are not the same as the findings of Polly et al., who found that undergraduate students felt an online molecular biology lab was the same as or better than the in-person experience [Citation16]. Our results are also not in agreement with comments made by allied health students in Kay et al.’s study, which suggested online labs are more helpful than in-person labs [Citation25]. However, other extraneous variables, such as the quality and personality of the instructor, undoubtedly play a significant role in student perceptions of educational experiences. These differences in perception may also be explained by our study design, in which in-person lab students were in their second year of medical school and may therefore show a greater appreciation for helpful activities that reinforce learning, despite having a greater command of microbiology as compared to first-year students. Student comments from Salter and Gardner’s study suggested that students greatly value one-on-one guidance from instructors, so access to instructors may be another reason for students perceiving the in-person lab as more helpful and even enjoyable than the online version [Citation2], which our findings support (, question 11).

When asked about their desires for online vs. in-person lab experiences, our results indicate that nearly 90% of students, including students from the online-only cohort, desire at least some in-person wet-lab instruction (; , question 14). This is consistent with Kay et al. who found that 50% of the surveyed students preferred both physical (in-person) and virtual (online) access to the lab work [Citation25]. Similarly, Salter and Gardner found that most students prefer in-person labs to online labs; however, they also reported preferences of a blended lab [Citation2]. Although these studies were comprised of integrated labs (combination of online and in-person modules), their designs and explanations of results warrant their comparison. Our data, combined with these studies, support the notion that most students respond extremely well to individual person–person interactions and feedback, regardless of the specific modality used [Citation4].

Despite the overwhelming majority of students reporting a desire for some in-person lab instruction, our data suggest a minor trend of students viewing their own lab experience format as the ideal format. Forty-three percent (43%) of students from the online cohort reported a preference for predominantly online instruction, compared to only 30% of the in-person lab cohort. Conversely, 37% of students receiving in-person lab instruction reported a preference for predominantly in-person lab instruction, compared to only 25% of the online lab student cohort. This suggests that, without exposure to an alternative to the current lab, students are somewhat hesitant to express a desire to change learning modalities. This preference by students for what is comfortable or familiar is supported by a study by psychologists Woody et al., who demonstrated that even technologically savvy students preferred textbooks to digital e-books, despite the physical advantages of digital resources [Citation26].

One potential advantage that an online lab has over a traditional wet lab is the length of time that students can access materials. In this study, students with access to the online lab had an entire week to examine the cases, as compared to the 2-hour-long wet lab for the in-person students. While we were unable to track the amount of time each student spent on the online activity, the students from both cohorts self-reported spending a similar amount of time on the activity (, question 7). As well, in-person labs have the potential advantage to limit distractions and allow students to focus for a dedicated amount of time. Digital resources, while convenient, are not without concerns. Online courses traditionally have lower completion rates [Citation27–Citation29], and the amount of time spent on digital activities (time-on-task) can be minimal, potentially due to the myriad of distractions [Citation30–Citation32]. Wet labs also have the advantage of ensuring a commitment from the student to the learning activity at a dedicated time and place.

Limitations to this study may provide a basis for future research of undergraduate medical student lab perceptions. First, the two groups of students were each limited to one microbiology lab method during the year due to curricular constraints, so no students were exposed to both methods in order to compare the two groups’ perceptions. Secondly, the wet lab cohort had already been exposed to a year of wet labs in microbiology, which may have altered their preconceptions regarding wet vs. online lab session. Thirdly, to preserve anonymity of the student responses, we did not capture or acquire the students’ individual assessment data to conduct a comparison of how students fared under each system, as this was not one of our core aims, and was also outside of the scope of the IRB approval. Although we noted no significant change in aggregate student grades between the two years (data not shown), future investigations could assess the educational outcomes of student learning under the different systems. Lastly, some of our perception data is potentially influenced through post-quiz bias; with our current design, students who scored well on the quiz may have been more likely to perceive the lab as ‘easy’ compared to students who did not score well. Future work could collect student perceptions before the quiz in order to negate the possible effects of the assessment scores.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrated that medical students generally perceived the microbiology lab design they personally experienced as the most beneficial, but that the vast majority of students report a desire for a blended microbiology laboratory experience containing both online and in-person wet-lab components. The in-person students’ preference for tactile learning corresponded with their perception that in-person labs are the optimal lab design. Likewise, the online students’ preference for visual learning was consistent with their perception that online labs are the ideal format. This study will contribute to future research investigating student perception of labs to ensure the development of a quality microbiology curriculum.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to collecting the data reported in this study, the survey, advertisement and methods were approved by KCU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB study number 303626).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Larry Mathias for literature review and writing assistance, Patrick Karabon for additional data analysis and Stephanie Swanberg for literature review assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Genuth S, Caston D, Lindley B, et al. Review of three decades of laboratory exercises in the preclinical curriculum at the case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 1992;67(3):203–12.

- Salter S, Gardner C. Online or face-to-face microbiology laboratory sessions? First year higher education student perspectives and preferences. Creative Educ. 2016;7(14):1869–1880.

- Matz RL, Rothman ED, Krajcik JS, et al. Concurrent enrollment in lecture and laboratory enhances student performance and retention. J Res Sci Teach. 2012;49(5):659–682.

- Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112.

- Baker N, Verran J. The future of microbiology laboratory classes – wet, dry or in combination? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(4):338–342.

- Hearing JC, Lu W-H. Trends in teaching laboratory medicine in microbiology to undergraduate medical students: a survey study. Med Sci Educator. 2014;24(1):117–123.

- Melber DJ, Teherani A, Schwartz BS. A comprehensive survey of preclinical microbiology curricula among US medical schools. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(2):164–168.

- Blewett EL, Kisamore JL. Evaluation of an interactive, case-based review session in teaching medical microbiology. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:56.

- Flint S, Stewart T. Food microbiology – design and testing of a virtual laboratory exercise. J Food Sci Educ. 2010;9(4):84–89.

- McCarthy D, O’Gorman C, Gormley GJ. Developing virtual patients for medical microbiology education. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(12):613–615.

- Moreno-Ger P, Torrente J, Bustamante J, et al. Application of a low-cost web-based simulation to improve students’ practical skills in medical education. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(6):459–467.

- Sancho P, Corral R, Rivas T, et al. A blended learning experience for teaching microbiology. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):120.

- Southwick F, Katona P, Kauffman C, et al. Commentary: IDSA guidelines for improving the teaching of preclinical medical microbiology and infectious diseases. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):19–22.

- Gibbins S, Sosabowski MH, Cunningham J. Evaluation of a web‐based resource to support a molecular biology practical class – does computer‐aided learning really work? Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2003;31(5):352–355.

- Makransky G, Thisgaard MW, Gadegaard H. Virtual simulations as preparation for lab exercises: assessing learning of key laboratory skills in microbiology and improvement of essential non-cognitive skills. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0155895.

- Polly P, Marcus N, Maguire D, et al. Evaluation of an adaptive virtual laboratory environment using Western Blotting for diagnosis of disease. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:222.

- Adams AE, Randall S, Traustadóttir T. A tale of two sections: an experiment to compare the effectiveness of a hybrid versus a traditional lecture format in introductory microbiology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14(1):ar6.

- McCarthy D, O’Gorman C, Gormley G. Intersecting virtual patients and microbiology: fostering a culture of learning. Ulster Med J. 2015;84(3):173–178.

- Finn KE, FitzPatrick K, Yan Z. Integrating lecture and laboratory in health sciences courses improves student satisfaction and performance. J College Sci Teach. 2017;47(1):66.

- Kotter T, Wagner J, Bruheim L, et al. Perceived medical school stress of undergraduate medical students predicts academic performance: an observational study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):256.

- Puthran R, Zhang MW, Tam WW, et al. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):456–468.

- Ludwig AB, Burton W, Weingarten J, et al. Depression and stress amongst undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:141.

- Merkel SM, Walman LB, Leventhal JS. An evaluation of computer-based instruction in microbiology. Microbiol Educ. 2000;1:14–19.

- Braun MW, Kearns KD. Improved learning efficiency and increased student collaboration through use of virtual microscopy in the teaching of human pathology. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1(6):240–246.

- Kay R, Goulding H, Li J. Assessing the impact of a virtual lab in an allied health program. J Allied Health. 2018;47(1):45–50.

- Woody WD, Daniel DB, Baker CA. E-books or textbooks: students prefer textbooks. Comput Educ. 2010;55(3):945–948.

- Seaton DT, Bergner Y, Chuang I, et al. Who does what in a massive open online course? Commun ACM. 2014;57(4):58–65.

- Parkinson D. Implications of a new form of online education. Nurs Times. 2014;110(13):15–17.

- Jordan K. Massive open online course completion rates revisited: assessment, length and attrition. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2015;16(3): 341–358.

- Calderwood C, Ackerman PL, Conklin EM. What else do college students “do” while studying? An investigation of multitasking. Comput Educ. 2014;75:19–29.

- Judd T. Making sense of multitasking: the role of Facebook. Comput Educ. 2014;70:194–202.

- Rosen LD, Carrier LM, Cheever NA. Facebook and texting made me do it: media-induced task-switching while studying. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(3):948–958.