ABSTRACT

Introduction

People who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and other sexual/gender minorities (LGBTQ+) may experience discrimination when seeking healthcare. Medical students should be trained in inclusive and affirming care for LGBTQ+ patients. This narrative literature review explores the landscape of interventions and evaluations related to LGBTQ+ health content taught in medical schools in the USA and suggests strategies for further curriculum development.

Methods

PubMed, ERIC, and Education Research Complete databases were systematically searched for peer-reviewed articles on LGBTQ+ health in medical student education in the USA published between 1 January 2011–6 February 2023. Articles were screened for eligibility and data was abstracted from all eligible articles. Data abstraction included the type of intervention or evaluation, sample population and size, and key outcomes.

Results

One hundred thirty-four articles met inclusion criteria and were reviewed. This includes 6 (4.5%) that evaluate existing curriculum, 77 (57.5%) study the impact of curriculum components and interventions, 36 (26.9%) evaluate student knowledge and learning experiences, and 15 (11.2%) describe the development of broad learning objectives and curriculum. Eight studies identified student knowledge gaps related to gender identity and affirming care and these topics were covered in 34 curriculum interventions.

Conclusion

Medical student education is important to address health disparities faced by the LGBTQ+ community, and has been an increasingly studied topic in the USA. A variety of curriculum interventions at single institutions show promise in enhancing student knowledge and training in LGBTQ+ health. Despite this, multiple studies indicate that students report inadequate education on certain topics with limitations in their knowledge and preparedness to care for LGBTQ+ patients, particularly transgender and gender diverse patients. Additional integration of LGBTQ+ curriculum content in areas of perceived deficits could help better prepare future physicians to care for LGBTQ+ patients and populations.

Introduction

The acronym ‘LGBTQ+’ describes people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and other sexual/gender minorities. Some people who are born with differences in sex development or who identify as intersex identify within the LGBTQ+ community as well and are considered within the ‘LGBTQ+’ umbrella in this paper. A survey conducted in the summer of 2022 by the Pew Research Center estimates that 7% of all adults and 17% of adults younger than 30 in the USA identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual[Citation1]. Data from May 2022 estimate that 1.6% of all adults and 5.1% of adults younger than 30 in the US identify as transgender or non-binary[Citation1].

LGBTQ+ identified individuals may experience discrimination in multiple areas of life, including employment, education, housing, legal, or healthcare settings. A recent study of interactions with healthcare providers among transgender, nonbinary, and gender expansive people found that 70.1% had at least one negative interaction with a healthcare provider in the past year [Citation2]. People who pursued gender-affirming care had 8.1 times the odds of reporting a negative interaction with a healthcare provider in the past year [Citation2].

Experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings may lead people to delay seeking care, contributing to further health disparities. A national survey of transgender individuals found that 30.8% of participants delayed or did not seek care due to discrimination [Citation3]. More than half of respondents had to teach their providers about transgender people, and this was significantly associated with greater odds of delaying care due to discrimination [Citation3].

Medical education has been posited as one area of intervention to address the health disparities faced by LGBTQ+ patients and improve patient healthcare experiences [Citation4]. In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Advisory Committee on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Sex Development published a detailed report that describes 30 competencies within eight domains to address the needs of LGBTQ+ patients in medical education [Citation4]. Despite these recommendations, the extent to which LGBTQ+ health is covered in medical education in the USA remains variable, and often limited, across different programs [Citation5–10].

While there are existing literature reviews that have explored medical education curricula on LGBTQ+ health [Citation5–7,Citation11] and transgender health [Citation8–10,Citation12], this review is uniquely comprehensive in that it integrates information from articles that evaluate both broad and specific curriculum items, curriculum development, as well as student knowledge and learning experiences in attempt to gain a holistic overview of this aspect of medical education, with the goal to identify common themes and opportunities for growth and development. This narrative literature review aims to explore the landscape of interventions and evaluations related to the LGBTQ+ health content that is taught and learned in medical schools in the USA with the goal of identifying critical gaps in existing curriculum and suggesting enhancements to address those gaps to better prepare future physicians.

Methods

Identification of relevant articles

The databases PubMed, ERIC, and Education Research Complete were systematically searched for peer-reviewed articles on LGBTQ+ health in medical school education in the USA written in the English language. The initial search identified articles published between 1 January 2011–19 May 2022. The search strategy was developed with the assistance of an academic librarian at our institution and the search terms utilized are available in Appendix 1.

Due to passage of time over the course of working on this review, the search was repeated for articles published between 20 May 2022–6 February 2023. The reference lists of all eligible articles were screened for additional articles for consideration.

Screening for eligible studies

The screening was completed by one author (TIJ) where areas of uncertainty were clarified with the other author (EMP). Articles were first screened by title and abstract. The inclusion criteria are displayed in . Articles that met initial inclusion criteria for further screening underwent full-text screening (see ). If the title and abstract for an article did not provide sufficient information to determine if the article should proceed with full text screening, the article underwent full text screening in an effort to identify all relevant articles.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria utilized when screening for eligible articles.

When considering articles that evaluated medical student education on LGBTQ+ health topics, articles that assessed medical student knowledge and comfort performing aspects of care for an LGBTQ+ patient were included. Articles that only evaluated medical student perception of a school’s acceptance of LGBTQ+ identities and without data on education or knowledge were excluded. Articles that only evaluated medical student biases toward the LGBTQ+ community were also excluded. Articles that gathered data from providers retrospectively about how much time they spent on LGBTQ+ health topics in medical school were also excluded given the variability of timeframes for their education.

Articles were only included for data abstraction if they involved the collection and analysis of new data. Commentaries, perspectives, letters to the editor, review articles, and other types of articles were excluded if they did not meet these criteria. Materials published outside of traditional commercial publishing, often referred to as ‘grey literature’, were excluded.

Data abstraction from included articles

Articles that were eligible based on full text screening underwent data abstraction. The following data were recorded in a spreadsheet: title, authors, year published, institution (if available), sample size, population studied (if applicable, e.g., first-year medical students), aim of the study, aspect of medical education studied (e.g., required clinical skills session), evaluation method (e.g., survey), intervention (if applicable, e.g., new lecture provided to students), description of LGBTQ+ health education at the medical school (if applicable), study findings, and conclusions. One author (TIJ) completed the data abstraction and conferred with the senior author (EMP) regarding any areas of uncertainty.

Articles used a variety of words to describe a method of evaluation that involved providing an instrument with questions for the participants to answer (e.g., surveys, questionnaires, evaluations, questions, forms, assessments). For consistency in this review, all of these methodologies are referred to as ‘surveys’. Additionally, some articles evaluated individual curriculum components or educational interventions, which will both be referred to as ‘interventions’ in this paper for consistency.

This review sought to characterize education in pre-clinical, clinical, or both settings. Some articles explicitly stated the type of curriculum they studied, however others did not. In some cases, the type of curriculum could be inferred based on the description. However, for some articles the type of curriculum could not be clearly identified, and this is noted as such with the article in .

Table 2. Overview of reviewed articles.

Articles that involved a learning outcome evaluation were also classified according to the Kirkpatrick Model of the 4 levels of evaluation [Citation13]. Level 1 (also referred to as ‘Reaction’) in this model refers to evaluations that assess to the degree to which trainees found the educational aspect to be engaging, favorable, and relevant to their position or program. Level 2 (‘Learning’) refers to evaluations that examine the degree to which trainees acquired the intended knowledge, skills, attitude, commitment, and confidence based on their participation in the educational material. Level 3 (‘Behavior’) refers to evaluations that assess the degree to which trainees apply what they have learned to situations in their program. Level 4 (‘Results’) refers to evaluations that examine the degree to which targeted outcomes occur as a result of the trainees participating in the educational aspect studied [Citation13].

No IRB or other ethical review was required for this project.

Results

Identification and screening of potential articles

The initial database search from 01/01/2011-05/19/2022 yielded 1,186 results (PubMed 1,048; ERIC and Education Research Complete 138). Among these, 1,097 were screened by their titles and abstracts after duplicates were removed. Subsequently, 250 articles underwent full text screening for eligibility, and 97 met inclusion criteria.

When the database search was repeated from 05/20/2022-02/06/2023, 174 unique additional articles were identified and underwent title and abstract screening. Thirty-one articles underwent full text review and 18 met inclusion criteria.

Screening of the references for all articles included following the two database searches above yielded 19 additional unique articles that met inclusion criteria. demonstrates the article identification and screening process.

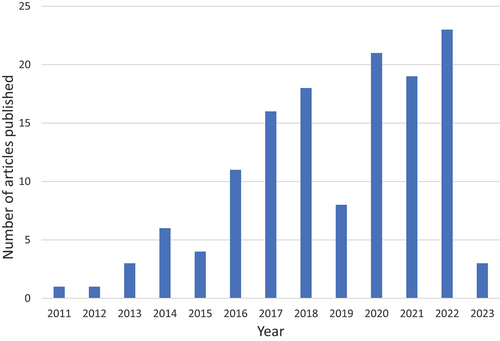

Screening yielded 134 total articles that met inclusion criteria, all of which were subsequently reviewed. An overview of all 134 reviewed articles can be found in , including information on the sample, methods, and select results. The articles are organized by topic area: those that evaluated existing curriculum (N = 6) [Citation14–19]; specific curriculum interventions (N = 77) [Citation20–96]; student learning experiences and knowledge (N = 36) [Citation97–132]; and the development of learning objectives and curricula (N = 15) [Citation133–147]. There was a trend for a greater number of relevant articles published in recent years, shown in . There was one article published in 2011 and in 2012. This increased to 21 (2020), 19 (2021), and 24 (2022) articles published that met inclusion criteria.

Broad evaluation of existing curriculum

Six articles (4.5%) evaluated the LGBTQ+ health content in existing curricula. Common tools for pre-clinical and/or clinical curriculum evaluations included the 2014 AAMC competencies [Citation4,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17] and learning objectives from Vanderbilt University [Citation14,Citation17]. Additionally, a team at Boston University developed the Sexual and Gender Minority Curriculum Assessment Tool (SGM-CAT) [Citation19] based on the AAMC competencies [Citation4] and used this to evaluate their curriculum [Citation19].

Using the 2014 AAMC competenecies [Citation4], two articles evaluated their school’s pre-clinical curriculum [Citation14,Citation17] and one the pre-clinical and clinical curriculum [Citation15]. Among these articles, fifteen [Citation14] and twenty-one [Citation17] of the 30 competencies were partially or fully met in the pre-clinical curricula of two programs, and the pre-clinical and clinical curriculum at a different institution was found to address thirteen [Citation15] of the 30 competencies. Two articles evaluated their pre-clinical curriculum using 31 learning objectives developed by Vanderbilt University in addition to the AAMC competencies [Citation14,Citation17]. These articles found their pre-clinical curricula to fully address twelve [Citation14] and twenty-two [Citation17], and partially address seven [Citation14] and five [Citation17], of the learning objectives. One article detailed the development of a 12-topic curriculum assessment tool based on the 30 AAMC competencies, named the SGM-CAT, which was then used to evaluate the pre-clinical and clinical curriculum at the institution [Citation19]. This evaluation found that while all topics were covered at some point in the curriculum, some were addressed only a couple of times, and LGBTQ+ health content was concentrated in the pre-clinical curriculum [Citation19]. Another team utilized a retreat to review their curriculum and develop proposed changes, which they subsequently tracked [Citation18]. Lastly, one article evaluated the inclusion of LGBTQ+ patients in the American Academy of Dermatology’s online Basic Dermatology Curriculum, and found one of 293 cases to mention an LGBTQ+ patient [Citation16].

Specific curriculum interventions

Seventy-seven (57%) articles evaluated the impact of specific curriculum interventions related to LGBTQ+ health. Of these, 42 (54.5%) took place in the pre-clinical curriculum, 16 (20.8%) in the clinical curriculum, and 19 (24.7%) either took place throughout both parts of the curriculum or it was unclear when they took place. Forty-three (55.8%) of the interventions were required for students to participate in, 32 (41.6%) were elective, 1 (1.3%) had both elective and required components, and for 1 (1.3%) intervention it was unspecified if it was required or elective. displays the type and requirement of the curriculum interventions.

Table 3. The most common intervention classification was required in the pre-clinical curriculum.

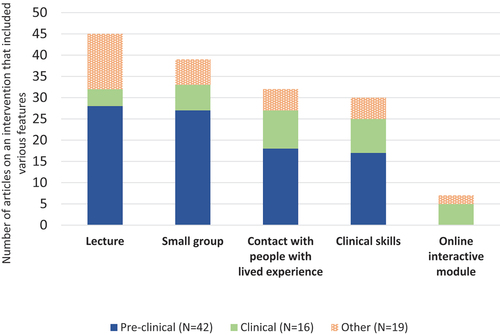

The curriculum interventions used a variety of teaching methods and features. Forty-five (58.4%) included a lecture component, 39 (50.6%) small group activities, 32 (41.6%) direct contact with people with lived experience, 30 (39.0%) hands-on clinical skills, and 7 (9.1%) online interactive modules. displays the frequency of these learning features by curriculum type.

Figure 3. Frequency of teaching modalities and learning features among the studied curriculum interventions.

Of the 45 interventions that included a lecture component, 13 (28.9%) involved only lectures and 32 (71.1%) combined the lecture with additional learning activities. The 32 interventions that included direct contact with people with lived experience incorporated this aspect in the following ways: a panel in 15 (46.9%); Q&A with an individual in 3 (9.4%); interactions with patients in clinical settings in 8 (25%); interactions with LGBTQ+ standardized patients in 7 (21.9%); LGBTQ+ people leading sessions/lecture in 2 (6.3%); and community work in 1 (3.1%).

Though not all articles provided measurements of knowledge and learning following the interventions, there were statistically significant improvements in knowledge in 22 (28.6%) articles, significant improvements confidence in 13 (16.9%), and significant improvements in comfort in 15 (19.5%). Almost all interventions were evaluated with one or more surveys.

Classifying these interventions according to the Kirkpatrick Model of the 4 levels of evaluation [Citation13], 22 (28.6%) studies involved level 1 (‘Reaction’) evaluation. Sixty-eight (88.3%) involved level 2 (‘Learning’) evaluation. Two (2.6%) included level 3 (‘Behavior’) evaluation, which in both studies occurred via evaluation of student encounters with standardized patients [Citation52,Citation75]. Some studies included more than one level of evaluation. None of the studies involved a level 4 evaluation (‘Results’).

While some interventions took a broader approach in looking at LGBTQ+ health, others had a more specific focus. Interventions in the pre-clinical curriculum covered a wide variety of topics, including: health disparities; barriers to care; terminology; taking an inclusive sexual history; reproductive endocrinology; sexually transmitted infections, including HIV; and care for transgender and gender diverse people (among both adult and pediatric patients). Interventions in the clinical curriculum covered similar topics, including: social determinants of health; reproductive justice; care for LGBTQ+ youth; and care for transgender and gender diverse people (among both adult and pediatric patients).

The most common topic across these interventions, described in 34 articles, was related to gender identity, care for transgender and gender diverse communities, and/or gender-affirming care. This included 19 interventions in the pre-clinical curriculum (15 of which were required) and 9 interventions in the clinical curriculum (3 of which were required). There was 1 required intervention on this topic area that involved both the pre-clinical and clinical curriculum, as well as 5 optional interventions that were not specified as occurring in a specific part of the curriculum. Among these interventions that focused on aspects related to gender identity and affirming care: 13 significantly increased knowledge [Citation25,Citation61,Citation62,Citation68,Citation71,Citation73,Citation75–78,Citation81,Citation85,Citation89]; 7 significantly increased comfort with aspects of providing care [Citation25,Citation37,Citation47,Citation48,Citation71,Citation73,Citation85]; and 4 significantly increased confidence in providing care [Citation21,Citation59,Citation62,Citation86].

Information about HIV and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) was a topic area of focus in 6 interventions. This included 2 required pre-clinical interventions and 4 elective interventions that either took place throughout both parts of the curriculum or it was unclear when they took place. While not all studies discussed statistical significance, among these interventions that focused on HIV and PrEP, 2 studies demonstrated significantly increased knowledge on this topic [Citation23,Citation91], 1 study found significantly increased agreement or confidence in some learning objectives at one site in the study [Citation79], and 1 study found significantly increased comfort discussing sexual behaviors with men who have sex with men (MSM), identifying at-risk MSM who may benefit from PrEP, and prescribing PrEP to MSM [Citation91].

Evaluating curriculum by student knowledge, preparedness, and learning experiences

Thirty-six articles (26.9%) studied medical student knowledge, preparedness, and learning experiences. Among these, 13 (36.1%) evaluated students and student experiences at a single institution and 23 (63.9%) across multiple institutions. Thirty-one (86.1%) articles involved data collection from medical students and 5 (13.9%) from faculty or medical school administrators. The most common method of data collection used was a survey, which was used by 35 (97.2%) articles. Three (8.3%) used interviews, 1 (2.8%) focus groups, 1 (2.8%) curriculum inventories, and 1 (2.8%) coding of recorded video interactions with standardized patients. There were a variety of themes studied within these articles, the frequency of which are shown in . This includes knowledge in 16 (44.4%), comfort in 9 (25%), preparedness in 9 (25%), specific or general curriculum components in 6 (16.7%), perceived coverage in curriculum in 5 (13.9%), amount of LGBTQ+ patient interaction in 4 (11.1%), hours of education in 4 (11.1%), comprehensiveness of training in 3 (8.3%), and confidence in 2 (5.6%).

Figure 4. Frequency of theme evaluation. ‘LGBT-DOCSS’ stands for the ‘LGBT-Development of Clinical Skills Scale’. This was developed by Bidell (2017) [Citation99] and was used as a measurement tool in two additional studies represented in this figure [Citation120,Citation121]. Of note, the LGBT-DOCSS includes assessment of preparedness and knowledge, and these articles are additionally included in the frequency displayed above for the categories ‘preparedness’ and ‘knowledge’ in addition to ‘LGBT-DOCSS’.

![Figure 4. Frequency of theme evaluation. ‘LGBT-DOCSS’ stands for the ‘LGBT-Development of Clinical Skills Scale’. This was developed by Bidell (2017) [Citation99] and was used as a measurement tool in two additional studies represented in this figure [Citation120,Citation121]. Of note, the LGBT-DOCSS includes assessment of preparedness and knowledge, and these articles are additionally included in the frequency displayed above for the categories ‘preparedness’ and ‘knowledge’ in addition to ‘LGBT-DOCSS’.](/cms/asset/e35f2252-df0e-4d4d-92a8-62953644602e/zmeo_a_2312716_f0004_oc.jpg)

Classifying these interventions according to the Kirkpatrick Model of the 4 levels of evaluation [Citation13], 11 (30.6%) of these studies involved level 1 (‘Reaction’) evaluation. Twenty-seven (75%) involved level 2 (‘Learning’) evaluation. One (2.8%) used level 3 (‘Behavior’) evaluation, which in this study consisted of evaluations of students in a standardized patient encounter [Citation127]. Some studies included more than one level of evaluation. None of the studies involved a level 4 evaluation (‘Results’).

During the period of this review, the ‘LGBT-Development of Clinical Skills Scale’ (LGBT-DOCSS) was developed by Bidell (2017) [Citation99] and was used as a measurement tool in 4 additional studies [Citation80,Citation93,Citation120,Citation121]. This tool includes subscales on attitudinal awareness, clinical skills, and basic knowledge [Citation99], and can be utilized to conduct evaluations at level 2 on the Kirkpatrick model, focusing on the knowledge and confidence of the learners.

Eleven studies discussed overarching gaps in LGBTQ+ health curricula at medical schools [Citation98,Citation101,Citation102,Citation109,Citation111,Citation114,Citation116,Citation118,Citation122,Citation124,Citation130]. This includes a survey of medical students across 175 of the 176 medical schools in the US and Canada that found that 76% of US DO and 65% of US MD medical students described their school’s LGBT-related curriculum as ‘fair,’ ‘poor,’ or ‘very poor’ [Citation130], a survey of medical students across two schools that described the average coverage as ‘too little’ or ‘basic’ of LGBT health items [Citation98], a survey of medical students across 12 schools that rated the comprehensiveness of their training about sexual and gender minority (SGM) health on average to be 5.37 (on a scale of 1–10 with 1 being minimal and 10 being comprehensive) [Citation101], and a survey of medical students across 12 schools who most commonly rated their training on SGM health as ‘moderate’ (34.8%) and ‘adequate’ (45.1%) with fewer responses on either end of the spectrum [Citation102]. A survey of faculty found that overall, coverage of concepts related to LGBT health were rated as ‘poor’ to ‘adequate’ [Citation116].

A study that included residents and fellows in addition to medical students found that while most respondents felt comfortable caring for LGBTQ+ patients, 39% did not feel that they received sufficient training and about half of the medical students and residents had minimal or no interaction with LGBTQ+ patients during their training [Citation114]. Also important to note is that this study found that respondents who had some discomfort treating LGBTQ+ patients cited lack of education as a reason for this [Citation114]. A study that surveyed medical students in addition to students in other programs found that 48% agreed their training prepared them to care for LGBTQ patients and 52% reported that their school integrated LGBTQ content into the formal curriculum [Citation111].

A common finding, identified in eight studies, a gap in student knowledge, preparedness, and/or training related to transgender health and gender-affirming care [Citation97,Citation111,Citation115,Citation118,Citation120,Citation126,Citation128,Citation132]. Four of these studies specifically found that students had lower knowledge, comfort, and preparedness related to working with transgender patients compared to lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients [Citation111,Citation115,Citation120,Citation126]. Specific deficits included only 32% of students agreeing that they know appropriate terminology for working with someone who is transgender [Citation97] and 23% feeling somewhat/very competent describing treatment options for patients who are transgender [Citation132]. The amount of education about the care for transgender and gender diverse people students reported receiving was variable, as one survey of medical students at one school found that 87% reported transgender patient care was part of their curriculum, however 52.5% reported needing more information on transgender health, and on average there was a self-reported lack of sufficient knowledge related to surgical and hormonal aspects of gender-affirming care [Citation118]. Another survey of medical students and physicians that found that only 56% participants received any formal transgender and non-binary health education in medical school [Citation109].

Another commonly studied discrete topic was student knowledge and education on HIV care, including PrEP, which was included in nine articles [Citation98,Citation103–108,Citation117,Citation124]. A survey of medical school administrators found that 38% of schools reported offering any PrEP content and 15.4% of schools reported having specific training regarding PrEP for LGBT patients [Citation108]. In a different survey, most (83.9%) medical and physician assistant students reported being taught about HIV risk and 60% being taught about PrEP, however 88.6% were aware of PrEP [Citation106]. One study found health professional students to have a mean HIV knowledge score of 79.6% and PrEP knowledge score of 84.1%[Citation103], and in a different evaluation of medical students, respondents demonstrated an average of 57.8% of questions on HIV and prophylaxis correct [Citation117]. Interviews with medical students found that LGBTQ+ health issues came up in the formal curriculum related to social history or with an HIV-positive gay male patient in case studies [Citation124]. Regarding findings related to HIV and PrEP in specific populations, the following findings were identified: 65% of medical and physician assistant students agreed that PrEP is effective in transgender women and 72% in MSM [Citation104]; medical students were less likely to identify a heterosexual female patient as a PrEP candidate and reported lowest confidence caring for heterosexual female patient seeking PrEP [Citation105]; and medical students were most willing to prescribe PrEP to patients with sustained condom use and multiple male partners (86%) and a single male partner (93%) [Citation107]. Health professional students surveyed about their education on HIV and PrEP reported that MSM were the most frequently presented candidate patient population for PrEP and transgender women who have sex with men were the least frequently presented patient population indicated for PrEP in their education [Citation106].

Broad curriculum and learning objective development approaches

Fifteen articles (11.2%) described approaches for broad curriculum and learning objective development. Many of these articles described the utilization of group settings as a key component, specifically including a retreat by 1 (6.7%) [Citation147], summit by 1 (6.7%) [Citation133], forum by 1 (6.7%) [Citation142], community of practice by 1 (6.7%) [Citation140], and specific committees or groups by 5 (33.3%) [Citation134–138]. Six (40%) [Citation136–138,Citation140,Citation142,Citation147] involved community members in their development. Two (13.3%) articles utilized surveys [Citation141,Citation142], 1 (6.7%) interviews [Citation143], 3 (20%) needs assessments [Citation136,Citation141,Citation145], and 1 (6.7%) a Delphi process [Citation139]. One (6.7%) article described the process by which a Topic Steward oversaw the integration of LGBTQ+ content into the curriculum [Citation144]. One (6.7%) utilized the epistemic peerhood model to consider medical education on gender-affirming care at their institution [Citation146].

Discussion

The aim of this review was to explore the landscape of interventions and evaluations related to the LGBTQ+ health content that is taught and learned in medical schools in the USA. We found a wide range of studies that described evaluations of the overall curriculum and specific curriculum interventions, procedures for the development of learning objectives and curricula, and evaluations of student knowledge and learning experiences related to LGBTQ+ health. In bringing the findings of these studies into conversation together, we offer insight into the current state of LGBTQ+ health medical student education with opportunities for growth and development.

Many specific curriculum interventions on LGBTQ+ health have been developed and studied over the past eleven years, which have been summarized in this review. Particular strengths demonstrated in the review include the breadth of educational interventions in the pre-clinical curriculum, variety of teaching modalities, and inclusion of LGBTQ+ community members. The educational interventions identified in this review most commonly occurred in the pre-clinical curriculum, with a little more than half of the interventions occurring exclusively during this portion of a training program (N = 42, 54.5% in pre-clinical curriculum; N = 16, 20.8% in clinical; and N = 19, 24.7% in both or unclear timing). These pre-clinical interventions provided education on a wide variety of topics, including: health disparities; barriers to care; terminology; taking an inclusive sexual history; reproductive endocrinology; sexually transmitted infections, including HIV; and care for transgender and gender diverse people (both adults and children). The breadth of topic coverage demonstrates how medical educators have integrated LGBTQ+ health into multiple didactic curricular areas. Similar to previous reviews, we found that components of teaching interventions were variable (for example, the content was sometimes delivered in lectures, small groups, panels, or online modules, among others) [Citation5–12]. This variability in teaching modality is another strength identified through this review, as studies have found benefits to active learning, compared to the more traditional lecture model [Citation148–150].

A third strength Identified In this review Is the Inclusion of LGBTQ+ community members. Various approaches to curriculum and learning objective development were described, and notably 6 included community members. Among curriculum interventions, 32 (41.6%) included direct contact with LGBTQ+ individuals. This is an increase in the proportion of curriculum interventions including LGBTQ+ people compared to the results reported in a review article by Sekoni et al. (2017), which found 5 of 16 (31.3%) to involve LGBTQ+ people in curriculum interventions [Citation7]. Intergroup contact theory suggests that direct contact between members of different groups can reduce intergroup prejudice [Citation151]. This has been shown to be true related to direct contact of students with LGBTQ+ people [Citation142,Citation152–154] suggesting that this could be a valuable addition to medical education. However, this should be balanced with consideration for the potential burden, often referred to as the ‘minority tax,’ that may occur when people from marginalized communities teach others about their identities, which was a concern raised in a study that involved a peer education model at one institution [Citation54].

Despite the strengths identified among current practices of medical educators, this review found common gaps in knowledge, confidence, and preparedness for medical students related to aspects of LGBTQ+ health. Eleven articles described overarching gaps in LGBTQ+ health curricula at medical schools [Citation98,Citation101,Citation102,Citation109,Citation111,Citation114,Citation116,Citation118,Citation122,Citation124,Citation130]. Overall ratings of the curricula broadly in these studies were generally adequate or lower. Specifically, these studies include surveys of medical students who described their curriculum in the following ways: LGBT-related curriculum as ‘fair,’ ‘poor,’ or ‘very poor’ by 76% of US DO and 65% of US MD students [Citation130]; average coverage of LGBT health items as ‘too little’ or ‘basic’[Citation98]; comprehensiveness of training about SGM health on average as 5.37 out of 10101; and training on SGM health as ‘moderate’ by 34.8% and ‘adequate’ by 45.1%[Citation102]. These findings extended to faculty, as a survey found that overall they rated coverage of concepts related to LGBT health as ‘poor’ to ‘adequate’ [Citation116].

This review also identified particular areas within LGBTQ+ health that were a common topic with lower proficiency for students. A specific topic area that was identified commonly as a gap in student training was related to gender-affirming care and the health of people who identify as transgender or gender diverse. Eight articles described gaps in student knowledge, preparedness, and training related to this topic [Citation97,Citation111,Citation115,Citation118,Citation120,Citation126,Citation128,Citation132]. Examples of specific deficits included only 32% of students agreeing that they know appropriate terminology for working with someone who is transgender [Citation97] and 23% feeling somewhat/very competent describing treatment options for patients who are transgender [Citation132]. This area is of particular importance to address when considering interventions to improve LGBTQ+ health education also because four studies found that medical students had lower knowledge, comfort, and preparedness related to working with transgender patients compared to lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients [Citation111,Citation115,Citation120,Citation126].

Given the high rate of negative experiences with healthcare providers among people who identify as transgender, nonbinary, and gender expansive [Citation2,Citation3], in addition to the health disparities faced by these patients [Citation155–157], improving medical student education on health for these communities is critical for improving healthcare experiences and outcomes for this population. This review sheds light on educational interventions that could be utilized to address these gaps, as there were 34 studies on interventions related to the health of people who identify as transgender or gender diverse and gender-affirming care, and 19 of these studies that showed statistically significant improvement in student outcomes. These interventions had a significant impact on multiple aspects of trainees preparation: 13 significantly increased knowledge [Citation25,Citation61,Citation62,Citation68,Citation71,Citation73,Citation75–78,Citation81,Citation85,Citation89]; 7 significantly increased comfort with aspects of providing care [Citation25,Citation37,Citation47,Citation48,Citation71,Citation73,Citation85]; and 4 significantly increased confidence in providing care [Citation21,Citation59,Citation62,Citation86]. Educational interventions on this topic area also align with the guidance in the 2014 AAMC report. For example, one competency reads, ‘Describing the special health care needs and available options for quality care for transgender patients and for patients born with DSD (e.g., specialist counseling, pubertal suppression, elective and nonelective hormone therapies, elective and nonelective surgeries, etc.)’[Citation4]. While future physicians in some specialties may not provide direct affirming hormonal or surgical care, it should be anticipated that the vast majority of physicians across all specialties will care for transgender and gender diverse patients in their residencies and clinical practice. Given that some of the gaps identified in this area were related to fundamental aspects of clinical care such as terminology [Citation97] or feeling comfortable caring for a patient [Citation111,Citation115,Citation126], providing all medical students with more familiarity with affirming care approaches would help optimize care for these patients.

Another common discrete topic that was studied in both medical student knowledge and preparedness as well as in curriculum interventions was related to HIV and PrEP. When comparing the findings from different studies assessing the state of education on this topic and student knowledge, it appears that there is variability across institutions. Specifically, data from a sample of medical school administrators shows that 38% of schools report offering any PrEP content and 15.4% of schools report specific training regarding PrEP for LGBT patients [Citation108]. In a different survey, 60% of medical and physician assistant students reporting being taught about PrEP [Citation106]. It is possible that the differences in findings from administrators compared to students could be related to their position within the school or due to a difference in schools represented by the samples. Student knowledge was also variable, as one study found health professional students to have a mean HIV knowledge score of 79.6% and PrEP knowledge score of 84.1%[Citation103], and medical students in a different evaluation had an average of 57.8% of questions on HIV and prophylaxis correct [Citation117]. Lastly, the articles in this review shed light on the importance of considering patient representation in this setting. Health professional students surveyed about their education on HIV and PrEP reported that MSM were the most frequently presented candidate patient population for PrEP and transgender women who have sex with men were the least frequently presented patient population indicated for PrEP in their education [Citation106]. Other studies found variability in how students responded when considering PrEP for patients of different demographics: a slightly higher percentage of medical and physician assistant students agreed that PrEP was effective in MSM (72%) compared to in transgender women (65%) [Citation104]; and medical students were less likely to identify a heterosexual female patient as a PrEP candidate and reported lowest confidence caring for heterosexual female patient seeking PrEP [Citation105]. While we cannot draw definitive conclusions between these findings, it is important to ensure that a diverse group of patients are portrayed in educational settings, and furthermore that stereotypes are not perpetuated in teaching materials.

Though the AAMC competencies do not explicitly reference HIV and PrEP, the report includes this topic in an example for integrating a competency (‘Explaining how homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and heterosexism affect health care inequalities, costs, and outcomes’): understanding that LGBTQ+ youth experience HIV at disproportionate rates compared to those who are not LGBTQ+[Citation4]. It is essential that all medical students are provided with information on HIV and PrEP, as they will very likely care for a patient with HIV or who takes, or is interested in, PrEP at some point during their careers.

While there is no standard requirement for what medical school curricula should cover in regard to LGBTQ+ health, the 2014 AAMC report details 30 competency recommendations that students should accomplish by the end of medical school [Citation4]. It appears that medical educators have responded to the guidance in this report as publications on LGBTQ+ health in medical education have steadily increased since 2014 (). This review found that certain competencies in the report are being addressed in these efforts to enhance LGBTQ+ medical education. Specifically, a competency that was addressed across many studies within the domain of patient care describes the expected ability for graduating students to obtain an inclusive sexual history, ‘Sensitively and effectively eliciting relevant information about sex anatomy, sex development, sexual behavior, sexual history, sexual orientation, sexual identity, and gender identity from all patients in a developmentally appropriate manner.’[Citation4] This competency was addressed by 13 interventions in this literature review [Citation20,Citation23,Citation31,Citation43,Citation46–48,Citation62,Citation66,Citation82,Citation84,Citation88,Citation94]. However, there remains work to be done in this field in order to fully address all recommended competencies. Across all reviewed articles, 5 school evaluated their full pre-clinical and/or clinical curriculum [Citation14,Citation15,Citation17–19]. Three institutions [Citation14,Citation15,Citation17] specifically used the AAMC competencies in their evaluations [Citation4]. These studies of curricula at individual institutions found that in the pre-clinical curriculum at two institutions partially or fully met fifteen [Citation14] and twenty-one [Citation17] of the 30 competencies, and the pre-clinical and clinical curriculum at a different institution addressed thirteen [Citation15]. It is important to note that the curricular gaps related to LGBTQ+ health may vary widely between individual institutions. When comparing the findings from the two studies that evaluated their pre-clinical curriculum based on the 30 AAMC competencies, the institutions had fifteen [Citation14] and nine [Citation17] competencies that were not addressed, and there were only five common gaps between these programs.

Therefore, we recommend that the existing curricula at individual institutions should be evaluated to identify strengths and gaps related to LGBTQ+ health education. Educators may opt to use a variety of frameworks for evaluating their curriculum. This could involve a broader evaluation of the curriculum, for example using the AAMC competencies [Citation4,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17], learning objectives from Vanderbilt University [Citation14,Citation17], or the more recently published tool from Boston University, the SGM-CAT [Citation19], which is based on the AAMC competencies [Citation4]. The 2014 AAMC report devotes a chapter to discussing curriculum and program evaluation, including sample interventions and evaluations [Citation4]. Educators could also follow the Kirkpatrick model of training evaluation [Citation13], and in this case could utilize the recently developed LGBT-DOCSS tool [Citation99], which was used in four studies in this review [Citation80,Citation120,Citation121,Citation143], and evaluates training at level 2 of the Kirkpatrick model.

Based on identified gaps in student training, knowledge, confidence, and preparedness or in the overall curriculum, specific educational activities and materials can be incorporated into the curriculum, such as those displayed in . Procedures that institutions used to evaluate and update their curricula discussed in articles in this review can also be considered in steps toward integration, such as forming specific committees or groups [Citation134–138] or hosting an event such as a retreat [Citation147], summit [Citation133], or forum [Citation142].

Based on this literature review, it is clearly evident and laudable that medical educators have developed significant content in response to the recommendations in the 2014 AAMC report. However, this review also demonstrated that gaps in student education and knowledge remain. To ensure learners are ultimately prepared to care for LGBTQ+ patients, LGBTQ+ health topics should be integrated longitudinally throughout medical school curriculum. In addition to educators evaluating the curriculum at their individual institutions, further teaching materials should be developed for the clinical curriculum. While many interventions in the pre-clinical curriculum were identified in this review, it is essential to integrate these topics throughout all aspects of a program’s curriculum. Furthermore, future studies are needed to assess the long-term implications of these educational interventions, specifically how they may impact patient care after training (in other words, addressing level 4 of the Kirkpatrick model, ‘Results’). Beyond the individual institution, building upon the competencies set forth by the 2014 AAMC report to determine standardized requirements for what students should learn about LGBTQ+ health in medical school is a critical next step in ensuring students at all institutions receive an adequate, inclusive, and holistic education that incorporates LGBTQ+ health appropriately. For instance, this may involve considering how to integrate assessment of LGBTQ+ health knowledge and skills in accreditation guidelines and assessment by national testing metrics.

Finally, in a country where sociopolitical discourse and policy create varying health care access and health equity issues for members of the LGBTQ+ community, especially as it relates to access and coverage for gender-affirming care, it is increasingly important that medical students within and across the US have more comprehensive knowledge about LGBTQ+ health issues so they are prepared to advocate for, and provide, equitable care.

Strengths and limitations

While existing reviews have studied specific curriculum aspects LGBTQ+ health [Citation5–7] and transgender health [Citation8–10] in medical school education, this is the first review to our knowledge that provides a comprehensive overview of studies on LGBTQ+ health education for medical students in the US that includes evaluation of specific curriculum evaluations, curriculum development procedures, and medical student learning outcomes. The broad approach taken by this review allows for the exploration of literature from multiple avenues that all contribute to our understanding of strengths and opportunities for improvement in LGBTQ+ health education for medical students.

This review is limited in that it is a narrative review that involved article reviews by one reviewer. Furthermore, 19 additional eligible articles were identified by screening reference lists of included articles, suggesting that other articles could have been missed by the search criteria we utilized. This review was limited to peer-reviewed studies and excluded grey literature, which may have prevented inclusion of relevant material. The review was also limited by the variable methodologies in the articles reviewed as many included measures of student self-reported knowledge and preparedness and some articles had mixed samples that including medical students among others. Additionally, the specific materials used in educational interventions and curricula were not consistently available with the published articles. Therefore, the way LGBTQ+ identities and topics were portrayed in these materials is not encompassed in this literature review. Future studies should include an examination of how this content is taught, to ensure that the material is presented in an inclusive manner that does not perpetuate stereotypes.

Lastly, it is important to note that this literature represents a segment of time with literature published between 1 January 2011–6 February 2023. Excitingly, additional studies in this area have been published since the conclusion of this literature review, and these will also likely prove useful to medical educators. Notably, a recent publication from medical educators across the country describes concrete strategies to promote inclusivity in language related to gender identity in pre-clinical and clinical learning spaces [Citation158].

Conclusions

Medical student education is an important avenue to consider in addressing health disparities faced by the LGBTQ+ community. This topic has been increasingly studied in peer-reviewed literature in the USA. There have been a variety of curriculum interventions at single institutions that show promise in enhancing student knowledge and training in LGBTQ+ health. Despite these advances, multiple studies find that some students report inadequate education on this topic and there are limitations in their knowledge and preparedness to care for LGBTQ+ patients, particularly transgender and gender diverse patients. This is likely driven by how LGBTQ+ health education is variable in its coverage and depth across different institutions, and future studies and efforts should be devoted to refining a standardized requirement or minimum guidelines for the inclusion of this content in medical education.

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

Both authors conceived and designed the review. TIJ conducted the literature screening and analysis, based on an approach for screening and analysis as determined by both authors. EMP reviewed the analysis and areas of uncertainty were clarified through reaching consensus in discussions between both authors. TIJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EMP reviewed the draft and provided feedback. Both authors collaborated on editing and finalizing the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final article, including all submitted tables, figures, and appendix.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank senior academic librarian Mary Hitchcock for her guidance and assistance in developing and executing the database searches for this project. We would also like to thank all of the community members, students, staff, and faculty who have and continue to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on LGBTQ+ health in medical education. We also thank the Kern National Network funded by the Kern Family Foundation that provided partial salary support for one of the authors (EMP) during the time of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown A. 5 key findings about LGBTQ+ Americans. Pew Research Center; 2023 [cited Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/06/23/5-key-findings-about-lgbtq-americans/.

- Inman EM, Obedin-Maliver J, Ragosta S, et al. Reports of negative interactions with healthcare providers among transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female at birth in the USA: results from an online, cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):6007. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20116007.

- Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care. 2016;54(11):1010–33.

- Hollenbach AD, Eckstrand KL, Dreger AD. Implementing curricular and institutional climate changes to improve health care for individuals who are LGBT, gender nonconforming, or born with DSD: a resource for medical educators. Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/129/

- Utamsingh PD, Kenya S, Lebron CN, et al. Beyond sensitivity. LGBT healthcare training in U.S. Medical schools: a review of the literature. Am J Sexuality Edu. 2017;12(2):148–169.

- McCann E, Brown M. The inclusion of LGBT+ health issues within undergraduate healthcare education and professional training programmes: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;64:204–214.

- Sekoni AO, Gale NK, Manga-Atangana B, et al. The effects of educational curricula and training on LGBT-specific health issues for healthcare students and professionals: a mixed-method systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21624.

- Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr, et al. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377–391.

- Nolan IT, Blasdel G, Dubin SN, et al. Current state of transgender medical education in the USA and Canada: update to a scoping review. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520934813.

- van Heesewijk J, Kent A, van de Grift TC, et al. Transgender health content in medical education: a theory-guided systematic review of current training practices and implementation barriers & facilitators. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2022;27(3):817–846.

- Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, et al. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):325.

- Korpaisarn S, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: a major barrier to care for transgender persons. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(3):271–275.

- Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick WK. Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development; 2016. https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/product/kirkpatricks-four-levels-of-training-evaluation/

- DeVita T, Bishop C, Plankey M. Queering medical education: systematically assessing LGBTQI health competency and implementing reform. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1510703.

- Encandela J, Zelin NS, Solotke M, et al. Principles and practices for developing an integrated medical school curricular sequence about sexual and gender minority health. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):319–334.

- Park AJ, Katz KA. Paucity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health-related content in the basic dermatology curriculum. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):614–615.

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Abon N. An audit of the medical pre-clinical curriculum at an urban university: sexual and gender minority health content. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1947172.

- Ton H, Eidson-Ton WS, Iosif AM, et al. Using a retreat to develop a 4-year sexual orientation and gender identity curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(5):796–801.

- Zumwalt AC, Carter EE, Gell-Levey IM, et al. A novel curriculum assessment tool, based on AAMC competencies, to improve medical education about sexual and gender minority populations. Acad Med. 2022;97(4):524–528.

- Bakhai N, Ramos J, Gorfinkle N, et al. Introductory learning of inclusive sexual history taking: an e-lecture, standardized patient case, and facilitated debrief. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10520.

- Berenson MG, Gavzy SJ, Cespedes L, et al. The case of sean smith: a three-part interactive module on transgender health for second-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10915.

- Bi S, Vela MB, Nathan AG, et al. Teaching intersectionality of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in a health disparities course. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10970.

- Cannon SM, Graber S, King HL, et al. PrEP university: a multi-disciplinary university-based hiv prevention education program. J Community Health. 2021;46(6):1213–1220.

- Christensen JA, Hunt T, Elsesser SA, et al. Medical student perspectives on LGBTQ health. PRiMER. 2019;3:27.

- Click IA, Mann AK, Buda M, et al. Transgender health education for medical students. Clin Teach. 2020;17(2):190–194.

- Croniger CM, Qua K, Seymour AR, et al. Preparing students to deliver care to diverse populations. Med Sci Educ. 2022;32(6):1285–1288.

- Eriksson SE, Safer JD. Evidence-based curricular content improves student knowledge and changes attitudes towards transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(7):837–841.

- Gavzy SJ, Berenson MG, Decker J, et al. The case of ty jackson: an interactive module on LGBT health employing introspective techniques and video-based case discussion. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15(10828). DOI:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10828

- Grosz AM, Gutierrez D, Lui AA, et al. A student-led introduction to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health for first-year medical students. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):52–56.

- Jin H, Dasgupta S. Genetics in LGB assisted reproduction: two flipped classroom, progressive disclosure cases. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10607.

- Lee R, Loeb D, Butterfield A. Sexual history taking curriculum: lecture and standardized patient cases. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9856.

- Leslie KF, Sawning S, Shaw MA, et al. Changes in medical student implicit attitudes following a health equity curricular intervention. Med Teach. 2018;40(4):372–378.

- Leslie KF, Steinbock S, Simpson R, et al. Interprofessional LGBT health equity education for early learners. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10551.

- Levy A, Prasad S, Griffin DP, et al. Attitudes and knowledge of medical students towards healthcare for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender seniors: impact of a case-based discussion with facilitators from the community. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17425.

- Marshall A, Pickle S, Lawlis S. Transgender medicine curriculum: integration into an organ system-based preclinical program. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10536.

- McCave EL, Aptaker D, Hartmann KD, et al. Promoting affirmative transgender health care practice within hospitals: an IPE standardized patient simulation for graduate health care learners. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10861.

- Najor AJ, Kling JM, Imhof RL, et al. Transgender health care curriculum development: a dual-site medical school campus pilot. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):102–113.

- Neff A, Kingery S. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: a problem-based learning case. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10522.

- Potter LA, Burnett-Bowie SM, Potter J. Teaching medical students how to ask patients questions about identity, intersectionality, and resilience. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10422.

- Safer JD, Pearce EN. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(4):633–637.

- Sanchez K, Abrams MP, Khallouq BB, et al. Classroom instruction: medical students’ attitudes toward LGBTQI(+) patients. J Homosex. 2022;69(11):1801–1818.

- Sell J, George D, Levine MP. HIV: a socioecological case study. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10509.

- Silverberg R, Averkiou P, Servoss J, et al. Training preclerkship medical students on history taking in transgender and gender nonconforming patients. Transgend Health. 2021;6(6):374–379.

- Singh P, Lee C. LGBTQ+ curriculum in medical school: vital first steps. Med Educ. 2022;56(5):556–557.

- Song AY, Poythress EL, Bocchini CE, et al. Reorienting orientation: introducing the social determinants of health to first-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10752.

- Stumbar SE, Garba NA, de la Cruz M, et al. Integration of sex and gender minority standardized patients into a workshop on gender-inclusive patient care: exploring medical student perspectives. South Med J. 2022;115(9):722–726.

- Stumbar SE, Garba NA, Stevens M, et al. Using a hybrid lecture and small-group standardized patient case to teach the inclusive sexual history and transgender patient care. South Med J. 2021;114(1):17–22.

- Stumbar SE, Garba NA, Holder C. Let’s talk about sex: the social determinants of sexual and reproductive health for second-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10772.

- Thompson HM, Clement AM, Ortiz R, et al. Community engagement to improve access to healthcare: a comparative case study to advance implementation science for transgender health equity. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):104.

- Thompson H, Coleman JA, Iyengar RM, et al. Evaluation of a gender-affirming healthcare curriculum for second-year medical students. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96(1139):515–519.

- Turban JL, Winer J, Boulware S, et al. Knowledge and attitudes toward transgender health. Clin Teach. 2018;15(3):203–207.

- Weingartner L, Noonan EJ, Bohnert C, et al. Gender-affirming care with transgender and genderqueer patients: a standardized patient case. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11249.

- Wong J. Medical school hotline: looking forward and enriching John A. Burns school of medicine’s curriculum: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender healthcare in medical education. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73(10):329–331.

- Gomez J, Gisondi MA. Peer teaching by stanford medical students in a sexual and gender minority health education program. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1731–1733.

- Greene RE, Garment AR, Avery A, et al. Transgender history taking through simulation activity. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):531–532.

- Johnson K, Rullo J, Faubion S. Student-initiated sexual health selective as a curricular tool. Sex Med. 2015;3(2):118–127.

- Kutscher E, Boutin-Foster C. Community perspectives in medicine: elective for first-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10501.

- Minturn MS, Martinez EI, Le T, et al. Early intervention for LGBTQ health: a 10-hour curriculum for preclinical health professions students. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11072.

- Pathoulas JT, Blume K, Penny J, et al. Effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve medical student comfort and familiarity with providing gender-affirming hormone therapy. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):61–64.

- Sequeira GM, Chakraborti C, Panunti BA. Integrating Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) content into undergraduate medical school curricula: a qualitative study. Ochsner J. 2012;12(4):379–382.

- Wright D, Campedelli A. Pilot study: increasing medical student comfort in transgender gynecology. MedEdPublish (2016). 2022;12:8.

- Zheng C, D’Costa Z, Zachow RJ, et al. Teaching trans-centric curricular content using modified jigsaw. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11257.

- Bakhai N, Shields R, Barone M, et al. An active learning module teaching advanced communication skills to care for sexual minority youth in clinical medical education. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10449.

- Cooper MB, Chacko M, Christner J. Incorporating LGBT health in an undergraduate medical education curriculum through the construct of social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10781.

- Dowshen N, Nguyen GT, Gilbert K, et al. Improving transgender health education for future doctors. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e5–6.

- Mayfield JJ, Ball EM, Tillery KA, et al. Beyond men, women, or both: a comprehensive, LGBTQ-inclusive, implicit-bias-aware, standardized-patient-based sexual history taking curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10634.

- Noonan EJ, Weingartner LA, Combs RM, et al. Perspectives of transgender and genderqueer standardized patients. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(2):116–128.

- Norwood AS, Altillo BSA, Adams E, et al. Learning with experts: incorporating community into gender-diverse healthcare education. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e6543–e6552.

- Ojo A, Singer MR, Morales B, et al. Reproductive justice: a case-based, interactive curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11275.

- Roth LT, Friedman S, Gordon R, et al. Rainbows and “ready for residency”: integrating LGBTQ health into medical education. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:11013.

- Schmidt CN, Stretten M, Bindman JG, et al. Care across the gender spectrum: a transgender health curriculum in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):706.

- Underman K, Giffort D, Hyderi A, et al. Transgender health: a standardized patient case for advanced clerkship students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10518.

- Park JA, Safer JD. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students’ preparedness above levels seen with didactic teaching alone: a key addition to the Boston university model for teaching transgender healthcare. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):10–16.

- Srinivasan S, Goldhammer H, Crall C, et al. A novel medical student elective course in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and sexually and gender diverse health: training tomorrow’s physician-leaders. LGBT Health. 2022;10(3):252–257.

- Vance SR Jr, Dentoni-Lasofsky B, Ozer E, et al. Using standardized patients to augment communication skills and self-efficacy in caring for transgender youth. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(8):1441–1448.

- Vance SR Jr, Buckelew SM, Dentoni-Lasofsky B, et al. A pediatric transgender medicine curriculum for multidisciplinary trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10896.

- Vance SR Jr, Lasofsky B, Ozer E, et al. Teaching paediatric transgender care. Clin Teach. 2018;15(3):214–220.

- Vance SR Jr, Deutsch MB, Rosenthal SM, et al. Enhancing pediatric trainees’ and students’ knowledge in providing care to transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(4):425–430.

- Alzate-Duque L, Sánchez JP, Marti SRM, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis education for clinicians caring for spanish-speaking men who have sex with men (MSM). MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11110.

- Barrett DL, Supapannachart KJ, Caleon RL, et al. Interactive session for residents and medical students on dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer patients. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11148.

- Braun HM, Garcia-Grossman IR, Quiñones-Rivera A, et al. Outcome and impact evaluation of a transgender health course for health profession students. LGBT Health. 2017;4(1):55–61.

- Braun HM, Ramirez D, Zahner GJ, et al. The LGBTQI health forum: an innovative interprofessional initiative to support curriculum reform. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1306419.

- Bunting SR, Saqueton R, Batteson TJ. A guide for designing student-led, interprofessional community education initiatives about HIV risk and pre-exposure prophylaxis. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10818.

- Calzo JP, Melchiono M, Richmond TK, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent health: an interprofessional case discussion. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10615.

- Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender health medical education intervention and its effects on beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge. Kans J Med. 2018;11(4):106–109.

- Congdon AP 3rd, Tiene K, Price C, et al. Closing the gap: raising medical professionals’ transgender awareness and medical proficiency through pharmacist-led education. Ment Health Clin. 2021;11(1):1–5.

- Gibson AW, Gobillot TA, Wang K, et al. A novel curriculum for medical student training in LGBTQ healthcare: a regional pathway experience. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520965254.

- Grant W, Adan MA, Samurkas CA, et al. Effect of participative web-based educational modules on HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention competency among medical students: single-arm interventional study. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e42197.

- Guss CE, Dahlberg S, Said JT, et al. Use of an educational video to improve transgender health care knowledge. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2022;61(5/6):412–417.

- Ingraham N, Magrini D, Brooks J, et al. Two tailored provider curricula promoting healthy weight in lesbian and bisexual women. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26 Suppl 1:S36–42.

- Perucho J, Alzate-Duque L, Bhuiyan A, et al. PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) education for clinicians: caring for an MSM patient. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10908.

- Pfaff MJ, Malapati SH, Su L, et al. A structured facial feminization fresh tissue surgical simulation laboratory improves trainee confidence and knowledge. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(5):1016e–1017e.

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Phillips S. Health professional student preparedness to care for sexual and gender minorities: efficacy of an elective interprofessional educational intervention. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(3):418–421.

- Sawning S, Steinbock S, Croley R, et al. A first step in addressing medical education curriculum gaps in lesbian-, gay-, bisexual-, and transgender-related content: the university of louisville lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health certificate program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2017;30(2):108–114.

- Thomas M, Balbo J, Nottingham K, et al. Student journal club to improve cultural humility with LGBTQ patients. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720963686.

- Block L, Ha N, Pleak RR, et al. LGBTQIA+ health care: faculty development and medical student education. Med Educ. 2020;54(11):1055–1056.

- Beck Dallaghan GL, Medder J, Zabinski J, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: a survey of attitudes, knowledge, preparedness, campus climate, and student recommendations for change in four Midwestern medical schools. Med Sci Educator. 2018;28:181–189.

- Bleasdale J, Wilson K, Aidoo-Frimpong G, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health education in healthcare professional graduate programs: a comparison of medical, nursing, and pharmacy students. J Homosex. 2022;1–14. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2022.2111535.

- Bidell MP. The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender development of clinical skills scale (LGBT-DOCSS): establishing a new interdisciplinary self-assessment for health providers. J Homosex. 2017;64(10):1432–1460.

- Bohnert CA, Combs RM, Noonan EJ, et al. Gender minorities in simulation: a mixed methods study of medical school standardized patient programs in the USA and Canada. Simul Healthc. 2021;16(6):e151–e158.

- Bunting SR, Calabrese SK, Spigner ST, et al. Evaluating medical students’ views of the complexity of sexual minority patients and implications for care. LGBT Health. 2022;9(5):348–358.

- Bunting SR, Chirica MG, Ritchie TD, et al. A national study of medical students’ attitudes toward sexual and gender minority populations: evaluating the effects of demographics and training. LGBT Health. 2021;8(1):79–87.

- Bunting SR, Feinstein BA, Hazra A, et al. Knowledge of HIV and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among medical and pharmacy students: a national, multi-site, cross-sectional study. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101590.

- Bunting SR, Garber SS, Goldstein RH, et al. Health profession students’ awareness, knowledge, and confidence regarding preexposure prophylaxis: results of a national, multidisciplinary survey. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(1):25–31.

- Bunting SR, Feinstein BA, Hazra A, et al. Effects of patient sexual orientation and gender identity on medical students’ decision making regarding preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus prevention: a vignette-based study. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(12):959–966.

- Bunting SR, Garber SS, Goldstein RH, et al. Student education about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) varies between regions of the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2873–2881.

- Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, et al. Prevention paradox: medical students are less inclined to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for patients in highest need. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(6):e25147.

- Cooper RL, Tabatabai M, Juarez PD, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis training among medical schools in the USA. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211028713.

- Dimant OE, Cook TE, Greene RE, et al. Experiences of transgender and gender nonbinary medical students and physicians. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):209–216.

- Green AR, Chun MBJ, Cervantes MC, et al. Measuring medical students’ preparedness and skills to provide cross-cultural care. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):15–22.

- Greene MZ, France K, Kreider EF, et al. Comparing medical, dental, and nursing students’ preparedness to address lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer health. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204104.

- Hayes V, Blondeau W, Bing-You RG. Assessment of medical student and resident/fellow knowledge, comfort, and training with sexual history taking in LGBTQ patients. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):383–387.

- Lapinski J, Sexton P, Baker L. Acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients, attitudes about their treatment, and related medical knowledge among osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114(10):788–796.

- Leandre F, Diaz-Fernandez V, Ginory A. Are medical students and residents receiving an appropriate education on LGBTQ+ health? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55(4):426–427.

- Liang JJ, Gardner IH, Walker JA, et al. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(8):897–906.

- Lindberg BM, Fulleborn ST, Semelrath KM, et al. Steps to improving sexual and gender diversity curricula in undergraduate medical education. Mil Med. 2019;184(1–2):e190–e194.

- Mani S, Bral D, Soltanianzadeh Y, et al. Evaluating attitudes toward and knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections in first-year medical students. J Stud Run Clin. 2018;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.59586/jsrc.v4i1.32.

- Muns SM, Ortiz-Ramos KJ, García-Rivera EJ, et al. Knowledge and attitudes about transgender healthcare: exploring the perspectives of hispanic medical students. P R Health Sci J. 2022;41(3):128–134.

- Newsom KD, Carter GA, Hille JJ. Assessing whether medical students consistently ask patients about sexual orientation and gender identity as a function of year in training. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):142–147.

- Nowaskie DZ, Patel AU. How much is needed? Patient exposure and curricular education on medical students’ LGBT cultural competency. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):490.

- Nowaskie DZ, Patel AU, Fang RC. A multicenter, multidisciplinary evaluation of 1701 healthcare professional students’ LGBT cultural competency: comparisons between dental, medical, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physical therapy, physician assistant, and social work students. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237670.

- Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. Jama. 2011;306(9):971–977.

- Phelan SM, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Medical school factors associated with changes in implicit and explicit bias against gay and lesbian people among 3492 graduating medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1193–1201.

- Robertson WJ. The irrelevance narrative: queer (In)visibility in medical education and practice. Med Anthropol Q. 2017;31(2):159–176.

- Talbott JMV, Lee YS, Titchen KE, et al. Characteristics and perspectives of human trafficking education: a survey of U.S. medical school administrators and students. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023;32(2):192–198.

- Thompson HM, Coleman JA, Kent PM. LGBT medical education: first-year medical students’ self-assessed knowledge and comfort with transgender and LGB populations. Med Sci Educator. 2018;28(4):693–697.

- Varas-Díaz N, Rivera-Segarra E, Neilands TB, et al. HIV/AIDS and intersectional stigmas: examining stigma related behaviours among medical students during service delivery. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(11):1598–1611.

- Vasudevan A, García AD, Hart BG, et al. Health professions students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward transgender healthcare. J Community Health. 2022;47(6):981–989.

- Warner C, Carlson S, Crichlow R, et al. Sexual health knowledge of U.S. medical students: a national survey. J Sex Med. 2018;15(8):1093–1102.

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):254–263.

- Wilson CK, West L, Stepleman L, et al. Attitudes toward LGBT patients among students in the health professions: influence of demographics and discipline. LGBT Health. 2014;1(3):204–211.

- Zelin NS, Hastings C, Beaulieu-Jones BR, et al. Sexual and gender minority health in medical curricula in new England: a pilot study of medical student comfort, competence and perception of curricula. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1461513.

- Coleman E, Elders J, Satcher D, et al. Summit on medical school education in sexual health: report of an expert consultation. J Sex Med. 2013;10(4):924–938.

- Coria A, McKelvey TG, Charlton P, et al. The design of a medical school social justice curriculum. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1442–1449.

- Eckstrand KL, Potter J, Bayer CR, et al. Giving context to the physician competency reference set: adapting to the needs of diverse populations. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):930–935.

- Holthouser A, Sawning S, Leslie KF, et al. eQuality: a process model to develop an integrated, comprehensive medical education curriculum for LGBT, gender nonconforming, and DSD health. Med Sci Educator. 2017;27(2):371–383.

- Katz-Wise SL, Jarvie EJ, Potter J, et al. Integrating LGBTQIA + community member perspectives into medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2022;1–15. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2022.2092112.

- Keuroghlian AS, Charlton BM, Katz-Wise SL, et al. Harvard medical school’s sexual and gender minority health equity initiative: curricular and climate innovations in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2022;97(12):1786–1793.

- Loder CM, Minadeo L, Jimenez L, et al. Bridging the expertise of advocates and academics to identify reproductive justice learning outcomes. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(1):11–22.

- Matthews-Juarez P, Brown KY, Suara HA. Communities of practice: transforming medical education and clinical practice for vulnerable populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(4s):18–25.

- Newsom KD, Buehler SA, Kurman TM. Filling the gap: creating a student-run LGBT+ clinic to address health disparities. Acad Med. 2022;97(6):777.

- Noonan EJ, Sawning S, Combs R, et al. Engaging the transgender community to improve medical education and prioritize healthcare initiatives. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(2):119–132.

- Pratt-Chapman ML. Implementation of sexual and gender minority health curricula in health care professional schools: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):138.

- Raygani S, Mangosing D, Clark KD, et al. Integrating LGBTQ+ health into medical education. Clin Teach. 2022;19(2):166–171.

- Stumbar SE, Brown DR, Lupi CS. Developing and implementing curricular objectives for sexual health in undergraduate medical education: a practical approach. Acad Med. 2020;95(1):77–82.