ABSTRACT

For centuries, Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-keepers (IEKK) and their land-based stories have played a vital role in environmental sustainability. Following the Indigenist relational theoretical framework, in this article, I honor and respect IEKK as scientists for their community and their traditional land-based stories as scientific knowledge for their environmental sustainability. As a visible minority immigrant researcher and educator on the Indigenous land known as Canada, IEKK land-based stories helped me rethink who I am as an Indigenist environmental researcher when I learn about my responsibilities from Indigenous communities. Following the Indigenist methodology and research framework, I used deep listening and reflective journal writing as my research methods. I also highlighted how my learning from IEKK land-based stories could help me take responsibility to rethink, relearn, and reshape us as environmental researchers.

Introduction

While there are many studies about the environmental impacts of climate change in many parts of the world, particularly the Canadian prairies and north, the role of Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-keepers’ (IEKK) land-based stories in resilience has been a lesser focus of inquiry (Hansen, Citation2018; Wildcat et al., Citation2014). IEKK land-based stories have been ignored, dismissed, and even undermined by governments in developing national policies. Addressing resilience in Indigenous communities or building community-led environmental sustainability in Canada requires leadership from Indigenous peoples, organizations, and governments. IEKK land-based stories can guide this process for governments, institutions, and international agencies (Bang et al., Citation2014; Cajete, Citation2015, Citation1994; Hansen, Citation2018; Kermoal & Altamirano-Jiménez, Citation2016).

The IEKK and their traditional land-based stories are significant parts of Indigenous culture, practice, and resilience (Cajete, Citation2015, Citation1994; Hansen, Citation2018; Kermoal & Altamirano-Jiménez, Citation2016; Tuck et al., Citation2014). Indigenous communities, Elders, Knowledge-keepers and their traditional land-based stories come from the land. IEKK’s land-based stories refer to both humans and non-humans (i.e. land, water, plants, animals, insects, and so on) (Simpson, Citation2014). Several Indigenous studies suggest IEKK land-based stories can guide a pathway to building environmental resilience, acting as a method of decolonization by reclaiming Indigenous ideology and land use (Holtgren, Citation2013; Norman et al., Citation2020). Other studies also indicated that without IEKK land-based stories, it is difficult to explore the meanings and means of environmental sustainability (Tom et al., Citation2019).

Indigenous people have stories that teach them that being on and working with the land every day gave them knowledge about the land, which led to their languages, cultures, and spirituality (Cajete, Citation2015, Citation1994; Hansen, Citation2018; Kermoal & Altamirano-Jiménez, Citation2016). IEKK land-based stories are essential to all aspects of environmental sustainability, including physical, spiritual, emotional, and cultural well-being, as it is through the land that Indigenous people have learned to live. Therefore, the connection to IEKK land-based stories is crucial for understanding and practicing environmental sustainability and for the well-being of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Thus, I center my learning reflections on Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-keepers as part of my responsibilities with respect and honor (Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008). It is important to note that I am not trying to generalize or predict the meanings of environmental sustainability on behalf of Indigenous people; rather, I share my learning as part of my relational responsibility (Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008). Thus, following the Indigenist theoretical framework, I highlighted how we all (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) could learn, practice, and benefit from IEKK land-based stories to re-think, re-learn, and re-shape us as researchers. I highlighted how IEKK land-based stories could help empower us as researchers, reshape our understanding of environmental sustainability, and advocate for community-led climate change resilience education and research. In this paper, I also discuss how IEKK land-based stories can refer to Indigenous rights, sovereignty, and self-determination; it is essential to know who designed the initiative, how it developed, and how the eligibility criteria reflect Indigenous ways of knowing and expertise.

Situating self

As a visible minority immigrant scholar in Canada, I need to understand who I am and what my responsibilities are as a researcher while learning from IEKK. Learning from various Indigenous communities in North America and South Asia, I know I need to take responsibility for building trustful relationships with the land and Indigenous people to create my belongingness and resilience on this Indigenous land (Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008). Learning and sharing land-based stories is part of my relational responsibilities; it is also a starting point for decolonization (2021).

I grew up as a religious minority in Bangladesh. Religious minority refers to non-Muslims, such as Hindus, Christian, Buddhists, and Indigenous. Non-Muslims experience racism in everyday practice, displacement, and killing (Bangladesh Human Rights Reports 2010–2020). Because of my minority identity, my family was displaced many times from our land (Guhathakurta, Citation2012; Samad, Citation1998). My family lost many of our relatives because of our land rights, land-based identities, land-based practices, and spiritualities. As a minority, our Elders and Knowledge-keepers’ traditional knowledge and land-based practice were not considered part of our education, profession, and decision-making processes. Many of our young people have experienced the consequences of this institutional denial through suffering many climate change disasters, including floods, cyclones, drinking water crises, and many more. Therefore, I understand the importance of IEKK land-based knowledge and practice as a vital part of environmental sustainability.

As a community-based researcher for the last 17 years, I know land-based learning and practice are integral parts of Indigenous meanings of environmental sustainability. For me, land-based learning advocates land rights for the community I am working with. Land-based research offers environmental justice for the community (Datta, Citation2018). As a minority, I did not have enough opportunity to learn the importance of land-based environmental sustainability in our institutional education. I did not learn our (non-Muslim) spiritual practices in my colonial education. In land-based learning, the land is considered everyday family members, body parts, parents, friends, and many more (Datta, Citation2018). In our institutional education, we did not have the opportunity to learn land-based education. Therefore, my mom used to refer to our institutional education in Bangladesh as colonial education. In my institutional education, I had to learn about how we can colonize our land by taking ownership of the land. In my colonial education, I also had to learn the justifications for racism against our family, our ancestors, and our everyday practice. I did not learn how to reclaim our traditional knowledge about land-based practice in my colonial education. When I asked my mom and other minority and Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-keepers about these issues, they usually complained that our colonial education system did not teach the true history. We had to learn that our colonizers were our heroes and that their colonial system was superior. Most of my land-based learning was from my mom, as she was a well-respected land-based storyteller. My mom is no longer with me; I have no opportunity to learn from her again. Mainstream society stole our traditional histories, knowledge, and sustainability. Racism is alive in our everyday life. The racist practices of mainstream society displaced and forced many minority people to migrate from their land internally and internationally.

I had the opportunity to receive land-based learning from Indigenous Elders, Knowledge-keepers, and educators once I moved to Canada. As a visible minority scholar in Canada, I know the importance of IEKK’s land-based learning and practice. With the support of IEKK’s land-based stories, I can reconnect with my land and create my self-determination and belonging with this land and people. Therefore, IEKK land-based stories are ceremonies for me.

Methodology and methods

Following an Indigenist theoretical framework, I use traditional storytelling as my research methodology and methods (Datta, Citation2019). The Indigenist theoretical framework honors and respects Indigenous worldviews, culture, and practice (Datta, Citationin press; Wilson, Citation2008). I choose the Indigenist theoretical framework because it centers on land-based relationality. Indigenous scholars Battiste (Citation2013), Smith (Citation2012), and Wilson (Citation2008, Citation2007) suggest that the Indigenist theoretical framework helps us understand deeper meanings of land-based learning, respecting relationships with land and people. The Indigenist framework teaches that Indigenous people are not in relationships with the land; they are relationships, they are land. Therefore, in Indigenist worldviews, IEKK land-based stories are their sustainability. Indigenist research views knowledge production through the lens of researchers being responsible and maintaining trustful relationships. In accordance with the Indigenist research framework, I followed both institutional and traditional protocols, developed long-term trusting relationships, and honored and respected IEKK knowledge and practice. For instance, in the Indigenist research framework, I considered Indigenous Elders and Knowledge-keepers as scientists, educators, and researchers in my research and my life, and their (IEKK) land-based stories as scientific knowledge. Indigenous peoples’ scientific knowledge emerges from thousands of years of practical learning. It is relational, fluid, and situational with local ways of knowing and doing (Datta, Citation2018). Its meanings are not fixed but may differ from community to community, land to land and generation to generation.

In learning IEKK land-based stories, my intention was not to generalize or to predict IEKK knowledge and practice but to reflect on my learning ceremonies about how we all (Indigenous, settler, immigrant, and refugee researchers, educators, and community members) can re-shape, re-think, and re-learn who we are as researchers and how we can benefit from IEKK stories by knowing our responsibilities and belongingness to protect all life, both human and non-human. For the last 17 years, my learning from IEKK land-based stories re-shaped me as a researcher (Datta, Citation2018), helped me re-think my research, and re-take my responsibilities (Datta, Citation2020) as part of my everyday responsibilities. Therefore, according to IEKK’s suggestion and respect, I did not identify IEKK names and locations in many situations; however, I respectfully acknowledged their name whenever they wanted.

Growing up on land-based stories, I learned that land-based knowledge and practice varies from Elder to Elder, Knowledge-keeper to Knowledge Keeper, land to land, community to community, and generation to generation. The land-based stories are not single event but lifelong learning and re-learning ceremonies. From my learning, I have seen that the IEKK land-based stories are diverse, multiple, and relational. In this article, and with permission from the communities I worked with, I reflect on the three years (2019–2021) I learned from Cree and Dene First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers in Treaty 6 and 7 Territories. Most of my learning was informal, such as during three cultural camps, seven traditional gatherings, 10 Powwow, 12 evening story sharing, and 15 informal online story sharing while maintaining and respecting conventional protocols. I used deep listening and reflective writing in a daily journal to develop my understanding.

My reflective writing helped me be responsible for my learning as a continuous process of becoming. Therefore, both deep listening and reflective writing are interconnected processes. It is a continuous process of becoming who I am on this Indigenous land and who I need to be. I sent my manuscript to First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers for their review and consent. They provided their oral consent and suggested continuing to do this as part of my relational responsibility. I was also told that once I am accountable for my learning and practice, once I am in relationships with both land and people Cree First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers, those who have the opportunity to read this article also become responsible for the land and people.

Learning land-based stories

IEKK land-based learning is mostly full of stories (Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008). I learned that land-based stories are diverse, complex, and relational. I learned that Elders and Knowledge-keepers have many oral stories about the land. Not all stories are written or possible to write. Many stories are sacred and cannot be written but only passed orally to future generations. Many IEKK suggested during our conversations in 2019 and 2021 that land-based stories are medicine for many communities. For instance, an Elder explained in June 2021 that land-based stories about traditional trapping, hunting, fishing, and gathering have helped people heal. There are many stories that provide a portrait of ways of life.

IEKK’s land-based stories helped me to reconnect with my ancestors’ meanings of land. For instance, while I was learning from IEKK, I felt I was learning from my mom. My mom used to tell me that everything in our surroundings has a story; every story has purpose, agency, and power. She also used to say we are combinations of stories; we as humans need to respect all non-human stories. She also said non-human stories are critical for humans as they are helpful to community resilience, resistance, and understanding of our purposes in life. According to her, the current human world is far away from these non-human stories. Therefore, humans become greedy; too often, they do not know what to do in a crisis and do not know how to find happiness. As a family, I observed my mom’s story reflection during Covid-19 that many people lost their hope and suffered many invisible stresses. Therefore, land-based stories are relationships that are critical to building our environmental sustainability.

Land-based identity

As a visible minority immigrant scholar in Canada, IEKK’s land-based stories helped me understand Indigenous identity meanings. For instance, in December 2020, one of the Cree Elders explained that everyone is Indigenous if they can connect with the land, understand Indigenous meanings of land, and take responsibility to protect it. The meanings of land-based identity are the responsibilities we all have towards each other. The discussion gave me the strength to rethink who I am and where I came from and take responsibility for protecting our land-based identity and stories.

I also learned from another Woodland Cree First Nation Elder (Dwayne Lasas), who was allowed to be one of his relatives (brother) as we are all related. He explained that land-based identity is scientific, and it does not need any validation from colonial histories and colonizers. I can connect Elders’ explanation of land-based identity with my mom’s stories. According to my mom, our land-based identity can help us reclaim our self-determination wherever we live. Therefore, land-based identity helps me re-think who we are on this Indigenous land known as Canada and what we need to do to protect land and ourselves, to act for environmental sustainability. Therefore, according to IEKK, I see my land-based identity as relational responsibilities and my self-determination as stories.

Land as a teacher

IEKK suggested we consider land as our teacher in our learning and practice. The IEKK I learned from suggested that the land, as a teacher, supports respectful, relational, reciprocal and responsible engagements and embraces multiple ways of knowing, being, and doing. For instance, Knowledge-keeper William Singer III, a member of the Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy who considered me as his relative, explained in an Indigenous-led land walk in summer 2021 that land teaches us relationality as everything in our surroundings is relational, the land, water, animals, plant life, and other human beings, because we rely on each other for survival. He shared many land-based stories while walking on the land, introducing himself to Native plants. He suggested that we can learn together that each element, plant and animal, has a name and a story, a gift and a responsibility, as do we humans. According to another IEKK story shared in January 2020, I learned that land as a teacher can offer many benefits, including kindness, sharing, honesty, and strength. In acknowledging IEKK as a teacher, in our everyday practice, we ask ourselves what we can do to honor our relationships that allow all beings (both human and non-human) to live in harmony and balance.

Story-based teaching

Land-based teaching is all about relational stories. There are different teaching stories in land-based learning and practice, including ceremonial teaching stories, spiritual teaching stories, medicinal teaching stories, animal and plant teaching stories, traditional teaching knowledge-based teaching stories, and Elders and Knowledge-keepers teaching stories. Elders also described that every animal has stories that can inspire, influence, and create self-determination. These stories can teach us how to balance human and non-human needs. During the Covid-19 pandemic, I had many opportunities not only to learn and relate to many stories from the online and land-based walk but also to share those stories with my children. I can see that this land-based teaching became effective for my children as they can relate their learning to the land they live on.

Co-existing and co-learning

Indigenous land-based learning is a process of co-existing and co-learning. I had many opportunities to learn IEKK stories at various times, particularly from various community meetings with Cree First Nation communities in August 2019, August 2020 and September 2021; land-based learning connects both humans and non-humans. For instance, one of Cree First Nation Elder suggested that understanding Indigenous identity (i.e. who I am) is interconnected with both human and non-human. He said everything in our surroundings has feelings, stories, and importance.

We consider the land as human relatives, family members, or creators in land-based relational stories. For instance, one of the Woodland Cree First Nation Elders explained that relationality in land-based learning is a life journey. It interconnects everything in our surroundings. Relationality has many forms and dimensions, and we need to respect the relationship. Another Cree First Nation Knowledge-keeper told stories about how humans should be respectful to the land because the land (i.e. land, water, birds, animals, plants, insects) provides everything for humans. From a land-based perspective, the Elders said that everyone is Indigenous if they think about where they came from, their ancestors’ relationship with the land and their language. Therefore, in land-based learning, everything has purpose, agency, and a story and we must co-exist to maintain sustainability.

Roles and responsibilities

According to Elders and Knowledge-keepers, land-based practices teach roles and responsibilities in life as environmental sustainability. As Cree Elders explained, everything in our surroundings plays roles and has responsibilities in maintaining sustainability. If one part does not meet their responsibilities, things become unbalanced. Elders pointed out that we as humans are not upholding our responsibilities; thus, there are many natural disasters and pandemics such as Covid-19, and so on. They said that we all need to know that all plants, animals, and insects, including weeds, have a purpose, language, and importance. Elders said that many plants considered weeds by Western researchers, Indigenous knowledge tells us it is medicine. Another Knowledge-keeper suggested that we have the profound responsibility to learn many things from the non-human. We consider everything land, including humans, land, water, sun, moon, plants, insects, fish, etc so on. Everything in the land has spirit, power, and agency.

Reclaiming

Indigenous land-based stories can help to be part of Indigenous land rights movements. For instance, one of the Elders suggested that land-based learning helps reclaim what was forgotten in colonization. The same Elder suggested that land-based stories can help us transform ourselves from colonial salve to Indigenous warriors. Another Knowledge Keeper, while leading a land-based walk discussed how we can be part of Indigenous land rights movements and identity once we know the critical land and land-based knowledge.

Decolonization

I learned from various Indigenous educator’s land-based stories that land-based learning can help us decolonize through learning, unlearning, and re-learning. Learning refers in land-based stories to learning the colonial history, its effects, how to unpack the negative outcomes of colonization, and critical perspectives on the colonial system; unlearning refers to a process that challenges injustice, racism, and oppression on land and people; and re-learning refers to the process coming to know the importance of Indigenous ways of life, traditional knowledge, practice, and ongoing movements for land-water rights, Indigenous rights, and justice. The land-based learning and practice are explained as a process of decolonization by Indigenous scholars such as Smith (Citation2012), who explained that decolonization is interconnected with land-based understanding and practice. Smith refers to decolonization in various forms, such as a solid understanding of Indigenous people, Indigenous rights, support for Indigenous people, unpacking histories, and consciousness regarding what needs to be done. Land-based learning centers on all these perspectives.

Political positionality

Many IEKK said that land-based learning and practice is a political positionality for many Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers. Similarly, many Indigenous and non-Indigenous studies also suggested that land-based research could empower researchers and participants (Datta, Citation2020, Citation2018; Smith, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2008). Thus, discussing the political position is critical for environmental sustainability research. The researcher’s political positionality helps the researcher center Indigenous voices, support and advocate for Indigenous needs in research, and promote Indigenous traditional knowledge in research.

Anti-racist solidarity

IEKK land-based stories promote anti-racist perspectives. For instance, over the last 11 years, I had many learning opportunities from Indigenous anti-racist scholars of Indigenous history, the impact of colonization, sustainability during pre-colonial histories, and the challenge of colonization on land, Indigenous people, and other racialized people. Most of the IEKK stories suggested anti-racist learning and practice for reclaiming Indigenous land rights and sustaining Indigenous environment sustainability.

IEKK suggested that land-based learning and practice can build responsibilities for many generations of children, youths, Elders and Knowledge-keepers in environmental sustainability. Bowra and Mashford-Pringle (Citation2020) suggested that ‘land-based learning is a powerful decolonizing tool that centers and honours Indigenous relationships with the land and all of creation’ (p. 1). Elders and Knowledge-keepers explained how land-based knowledge and practices could provide many forms of responsibilities; however, Cree First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers shared five forms of responsibilities that are prominent for their communities: (1) renewing relationships between human and non-human, (2) taking responsibility to protect both human and non-human, (3) respecting all creation, all generations, all cycles, (4) honoring Elders and Knowledge-keepers knowledge and practice and traditional knowledge, (5) sharing land-based knowledge with youths so that they can take responsibility.

Community-based and community-led

The IEKK land-based stories promote community-based and community-led perspectives. I learned how IEKK land-based stories advocated for community perspectives in decision-making, community teaching for researchers, and community guidelines. IEKK suggested in many stories told during community knowledge sharing that Indigenous decision-making in their environmental sustainable development would be community-led, community-guided, and community-engaged.

Renewal

Elders and Knowledge-keepers suggested that land-based learning refers to the community-led renewal of the earth system. The renewal earth system in land-based learning help to re-build a relationship with both earth and human. Re-building or renewal of relationships helps us learn how to take responsibility to protect humans and non-humans, including land, water, air, animals, and plants. According to Elders, our renewal relationships with land can make us hopeful. Therefore, we should be excited to renew our relationships. For example, IEKK suggested that collaborative protection for both humans and non-humans should be considered in each decision-making step when it comes to development.

Hopes

Elders and Knowledge-keepers suggested that the land-based learning and practices create hope for the community regarding how to live life confidently. Hope in land-based learning become ceremonies. Land-based learning can help us become hopeful about our relationships with the land and connect and celebrate each moment as an opportunity. Community perspectives, knowledge, and practice are the center of land-based research. According to Elders, community-led land-based learning refers to a firm voice for positive change for the community, hopes for the future generation, and collective strengths to protect the earth.

Connection with UN declaration

The IEKK land-based stories are interconnected with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Binder & Binder, Citation2016; Murphy, Citation2014; UNDRIP, Citation2007). Many Elders and Knowledge-keepers suggested that Canada’s federal and provincial governments have judicial responsibilities to implement UNDRIP. For instance, IEKK during 2019 and 2020 community knowledge sharing that land-based stories are powerful tools for implementing the UN declaration in Canada and beyond. IEKK land-based stories can guide all stakeholders (Indigenous IEKK call it rightsholders), including governments, educational intuitions, leaders, to work in cooperation with Indigenous peoples to change the existing worldview, challenge colonialism, and protect Indigenous land rights, eliminating discrimination (Gilbert & Lennox, Citation2019; McGregor et al., Citation2020). Therefore, my learning and IEKK suggests, the IEKK land-based stories can play a critical role in implementing Canada’s commitments to UNDRIP.

Connection with reconciliation in Canada

IEKK’s land-based stories are deeply connected with the meaningful implications of reconciliation (Johnson, Citation2016). As various Elders and Knowledge-keepers suggested, Indigenous land-based stories are based on Indigenous land rights, climate justice, and environmental rights. These stories can enhance meaningful reconciliation initiatives in Canada. Elders and Knowledge-keepers specifically suggested some of the TRC Calls for Action, including Calls 12, 13, and 63. IEKK land-based stories can also develop non-Indigenous awareness and responsibilities for implementing TRC calls (Eckert et al., Citation2019). Specifically, IEKK land-based stories can help both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people’s relationship with the land, learning the importance of land-rights and land-based knowledge.

Connection with UN SDGs

Besides the TRC and the UN Declaration, I learned that IEKK land-based stories have substantial implications for UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (Carling, Citation2018; Yap & Watene, Citation2019). For instance, IEKK land-based stories are significantly associated with SGDs 13 and 15. IEKK land-based stories often refer to how the UNDRIP can be implemented to support Indigenous groups worldwide to drive their development agenda.

Discussion

As I have learned, IEKK land-based knowledge and practice are significant for all Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples for various reasons, including refocusing on land-based practice, the proven scientific knowledge gained from centuries of environmental sustainable practices; redeveloping community-led decision-making processes; unpacking the colonial history of the land; rethinking the meanings of scientific knowledge; reshaping both research and researchers; promoting Indigenous rights; redeveloping self-determination for the communities; recentring relationship with the land; understanding science as holistic and practice-based.

Re-thinking and re-shaping opportunities

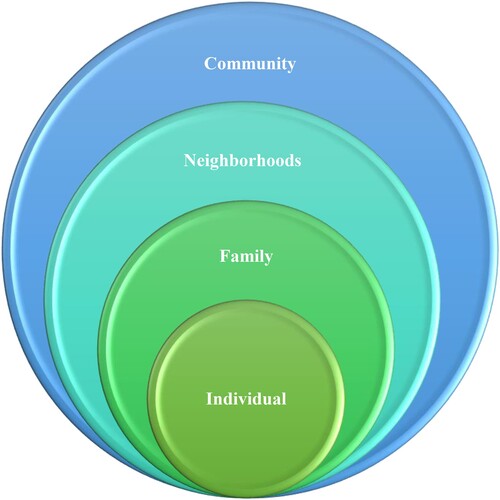

Learning IEKK land-based stories in environmental sustainability plays a critical role as I rethink and reshape who I am as an environmental researcher and where I came from (i.e. my worldview). IEKK’s land-based stories helped me reshape my responsibility in many relational ways. For instance, according to Cree First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers, land-based knowledge and practices have four interconnected relations: with self, with family, with community, and with culture. This provides a holistic perspective of learning into practice. It also shows how our relationships start with meeting our own responsibilities. The steps are interconnected; they create encouragements and responsibilities to protect land, share our stories with future generations, and work together spiritually, mentally, and physically.

These four forms of direction focus on land-based learning and practice, which can explain the responsibilities of self. I do not separate these relationships from each other, rather understand them as deeply interconnected with various intergenerational land-based stories, cultures, knowledge, and practices ().

Figure 1. Shows how land-based knowledge edges are interconnected with each other individuals, families, neighborhoods, and communities. It also shows how responsibilities start from and within ourselves as an individual.

I have also seen that IEKK land-based stories have many meaningful implications in my personal life. For instance, I grew up with land-based learning and practice. I learned from my mom that land is another mom who takes care of all of us. Without our land, we would not be here. My family prayed and showed respect to our land every early morning. We understood the land to include everything in our environment, such as the Sun, Water, Plants, Animals, insects, and soil. All of them are part of our family, our neighborhood, and our community. I learned from my mom that we (human Sun, Water, Plants, Animals, insects, soil, and so on) are all spiritually connected. Our relationships are not based on religious worship but spirituality. When I hear similar stories from Cree First Nation Elders and Knowledge-keepers, I can re-connect, re-learn, re-imagine, and re-dream to re-figure who I am, where I came from, and which land I am living, and what I should do.

IEKK’s land-based stories help me to rebuild my relationship with the land. For instance, when I am learning land-based stories, I feel I am part universe, where the sun, moon, plants, and animals are part of my family. Whenever I had a chance, I used to go to the local forest and talk to plants, insects, animals, and small birds like friends. I used to sit, walk, be silent, talk, feel, and smell my surroundings. Whenever I am in the local forest, riverside, and open land, I think I am with my family and relatives (Tuck et al., Citation2014).

Indigenous IEKK land-based stories can help us in (re)connecting, creating all of our belongingness, and building community-led climate change resilience. From my reflections on various stories from my ongoing research with Indigenous communities, I learned that IEKK land-based stories are Indigenous-led. All these stories have the agency to create environmental sustainability within and from the community. They are effective for the community, particularly the youth. Elsewhere, I have discussed how Indigenous youth are taking the lead in redefining the meanings of environmental sustainability thanks to a sustainable education from IEKK stories (Datta, Citation2018).

Relational responsibilities

My relationships with land always keep me responsible, not to harm them, not to destroy them but to take care of them. I used to feel how the land was taking care of me by providing food, water, sunlight, air, wind. Therefore, whenever I close my eyes, I feel that my body and mind are in relationships with the land, water, plants, animals, sun, moon, and insects. My relationships with land always remind me of my responsibilities to know who I am and who I should be. Whenever I reflect on land and my land-based learning, I see myself as a cosmos of relationships, love, and joy. I am no longer apart from my surrounding, above or below in my relationships. I am within and from my relationships. Therefore, IEKK land-based stories help us re-shape and re-think, which starts from me; land becomes part of my family, neighborhood, and community.

IEKK’s land-based story is a process of relational practice. Relationality is centered on land-based stories. According to Cree First Nation Elders, we become responsible for each other once we are in a relationship. Similarly, Indigenous scholars Battiste (Citation2013), Smith (Citation2012), and Wilson (Citation2008) explain the importance of relationality in land-based research. According to them, relational storytelling helps us understand deeper meanings of relationships, maintain relationships, and be respectful in relationships. They refer to relationality as a form of sustainability for researchers and research participants. Likewise, Cree Elders also suggested that land-based learning can make both researchers and participants responsible for each other.

Learning IEKK land-based stories should be our responsibility in developing our relationships with the land and Indigenous people. While IEKK land-based stories have been effective for many centuries for many Indigenous communities, currently, they are in a precarious position. Many IEKK suggested that they carry many sustainable stories; however, neither the current education system (Datta, Citation2018) nor environmental policymakers document these land-based knowledges. Therefore, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children do not have these opportunity to learn and practice in their everyday lives. During my previous research in 2016, one Dene First Nation Elder from Saskatchewan, Canada, explained the importance of IEKK land-based stories during our story sharing, saying that

I will die with many successful stories. I have passed my successful life; now, it is your [educators and researchers] responsibility to record our [Elders and knowledge holders] successful stories and share them with future generations. (Datta, Citation2018, p. 53)

Thus, I learned from my reflections that taking responsibility to learn IEKK land-based stories and practice can create our future with this Indigenous land that we live on. Thus, Indigenous scholar Shawn Wilson (Citation2008) suggests land-based learning as a relational ceremony. As indicated by Wilson, once we are in relationships, we are accountable to each other.

Building a bridge

IEKK land-based stories can re-engage Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in their education and build a bridge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, decolonize colonial histories, re-think Indigenous and non-Indigenous responsibilities to protect land and people, and revitalize Indigenous languages and practices (Tuck & Yang, Citation2018; Wilson, Citation2008). Bowra and Mashford-Pringle (Citation2020) suggested that ‘In being on the land, Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples can come together and draw strength from their ancestors, relationships, and histories to heal and transcend the trauma caused by past and present colonial processes’ (p. 1). IEKK land-based stories provide benefits such as building community connectedness and resilience, improving mental, physical, and spiritual wellness, advancing reconciliation by decolonizing environmental sustainability, and improving our responsibilities as researchers and educators.

Connected with TRC calls for action

IEKK’s land-based stories are directly and indirectly connected with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Citation2015) Calls for action and accountability through transparency (TRC, Citation2015). Studies have suggested that recognizing the importance of IEKK land-based stories and the knowledge in them is fundamental to Canada’s reconciliation process (Corntassel & Hardbarger, Citation2019). As in the case of reclaiming land rights, such experience may provide important lessons about how people today can more respectfully and sustainably interact with our non-human neighbors. In these times of severe climate change, honoring and safeguarding traditional IEKK has never been more critical. Indigenous IEKK land-based stories are beneficial, including meaningful implications for Indigenous rights and connection with TRC Calls for Action.

Indigenous IEKK land-based stories in environmental sustainability center on Indigenous rights, including the right of Indigenous peoples to own, use, and protect their lands (Borrows, Citation2016). Indigenous IEKK land-based stories are deeply connected to spiritual, physical, mental, and social wellness. The Indigenous IEKK land-based stories teach how to share food, a practice done between community members to facilitate connectedness. Many Indigenous and non-Indigenous research shows that IEKK land-based stories have many mental health benefits, improve understanding for active learners, and help non-Indigenous people develop environmental awareness and connect to the land (Corntassel & Hardbarger, Citation2019; Datta et al., Citationin press). Similarly, other Indigenous studies suggest IEKK land-based stories often bring together Elders and youth so that Elders can pass on their knowledge, including cultural ceremonies, traditional medicines, cultural camps, the history of the land, how to be good stewards of the land, and how to speak traditional languages, among other activities.

IEKK stories remind me that we, as Indigenist researchers, must remember that everything is interconnected and relies upon everything working together. IEKK stories have diverse meanings, agency, and power to guide us to decolonize our understanding of environmental sustainability in a way that can be beneficial for researchers and the community. Therefore, I see IEKK stories are living, ceremonial opportunities and relational responsibilities like Indigenous scholars.

Conclusion

As an Indigenist researcher, I see my learning opportunities from IEKK land-based stories as a lifelong, relational process. It is also a continuous process to know who I am on this Indigenous land and what my responsibilities are towards the land and people. By using deep listening and reflective writing, I learned that IEKK land-based stories have the agency to reshape both who I am as a researcher and who I need to be. IEKK’s land-based stories have celebrated each moment, each opportunity.

The findings from IEKK land-based stories and my reflective writing have important implications for learning the Indigenous meanings of environmental sustainability and well-being and how future generations perpetuate indigenous knowledge. I have seen how IEKK land-based learning can create the resilience and strength of Indigenous youth, as exemplified in Dene and Cree First Nation Communities (Datta, Citation2018, Citation2019). While I was learning from IEKK land-based stories in Canada, it reconnected and reminds me of my own land-based stories. I know land rights is a crucial part of environmental sustainability. When we were out on the land, the land was a strength for us. Our land-based stories were also our environmental sustainability. IEKK land-based stories also remind me how we as researchers and educators need to be responsible to the humans and our other family members, such as water, plants, animals, or other aspects of the natural world.

Indigenous IEKK land-based stories in land-based environmental sustainability center on land’s importance in everyday practice. The meaning of environmental sustainability in Indigenous communities is not static, but complex, interrelated, fluid, and situational. For example, Indigenous IEKK land-based stories provide a sense of belonging to a collectively shared place and create a safe space for sharing and learning. Indigenous IEKK land-based stories help us re-learn how and why to celebrate traditional land-based ceremonies such as cultural camps, space itself, fire, for materials such as drums or clothing, sweat lodges, Pow Wow, and much more. The Indigenous IEKK land-based stories also center on the importance of Indigenous language rights deeply connected to and shaped by the land. I have learned how IEKK land-based stories in land-based environmental sustainability provide various learning opportunities for ongoing decolonization, such as its uses and history, and protecting and caring for the land as a community facilitates community connectedness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bang, M., Curley, L., Kessel, A., Marin, A., Suzukovich, E. S., III & Strack, G. (2014). Muskrat theories, tobacco in the streets, and living Chicago as Indigenous land. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.865113

- Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing Limited.

- Binder Ch & Binder Co. (2016). A capability perspective on indigenous autonomy. Oxford Development Studies, 44(3), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1167178

- Borrows, J. (2016). Outsider education: Indigenous law and land-based learning. Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice, 33(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.22329/wyaj.v33i1.4807

- Bowra, A., & Mashford-Pringle, A. (2020). Indigenous learning on Turtle Island: A literature review on land-based learning. The Canadian Geographer, 65(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12659.

- Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of Indian education. Kivaki Press.

- Cajete, G. (2015). Indigenous community: Rekindling the teachings of the seventh fire. Living Justice Press.

- Carling, J. (2018, March 20). ‘Development makes us vulnerable’: Call for SDGs to learn from Indigenous peoples. https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/articles/development-makes-us-vulnerable-call-sdgs-learn-indigenous-peoples

- Corntassel, J., & Hardbarger, T. (2019). Educate to perpetuate: Land-based pedagogies and community resurgence. International Review of Education, 65(1), 87–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-018-9759-1

- Datta, R. (2018). Traditional story sharing: An effective Indigenous research methodology and its implications for environmental research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117741351

- Datta, R. (2019). Rethinking environmental science education from indigenous knowledge perspectives: An experience with a Dene First Nation community. Environmental Education Research, 24(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1219980

- Datta, R. (Ed.). (2020). Reconciliation in practice: Cross-cultural perspectives. Fernwood Publishing.

- Datta, R., Hurlbert, M., & Wilson, M. (in press). Building Indigenous community-led energy resilience. Springer.

- Datta, R. (in press). Learning from the land: An effective Indigenist methodology in environmental sustainability research. In N. Denzin and M. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry in (post?) pandemic times: New challenges. Routledge.

- Eckert, L. E., XEMŦOLTW_ Claxton, N., Owens, C., Johnston, A., Ban, N. C., Moola, F., & Darimont, C. T. (2019). Indigenous knowledge and federal environmental assessments in Canada: Applying past lessons to the 2019 impact assessment act. FACETS, 5(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2019-0039

- Gilbert, J., & Lennox, C. (2019). Towards new development paradigms: the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a tool to support self-determined development. The International Journal of Human Rights, 23(1-2), 104–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2018.1562921

- Guhathakurta, M. (2012). Amidst the winds of change: The Hindu minority in Bangladesh. South Asian History and Culture, 3(2), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2012.664434

- Hansen, J. G. (2018). Cree Elders’ perspectives on land-based education: A case study. Brock Education: A Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 28(1), 74–91. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v28i1.783.

- Holtgren, M. (2013). Bringing us back to the river. In N. Auer, & D. Dempsey (Eds.), The Great Lake Sturgeon (pp. 133–147). Michigan State University Press.

- Johnson, S. (2016). Indigenizing higher education and the calls to action: Awakening to personal, political, and academic responsibilities. Canadian Social Work Review / Revue canadienne de service social, 33(1), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.7202/1037096ar

- Kermoal, N., & Altamirano-Jiménez, I. (2016). Living on the land: Indigenous women’s understandings of place. Athabasca University Press.

- McGregor, D., Whitaker, S., & Sritharan, M. (2020). Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.007

- Murphy, M. (2014). Self-determination as a collective capability: The case of indigenous peoples. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 15(4), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.878320

- Norman, M. E., Hart, M., & Mason, G. (2020). Restor(y)ing place: Indigenous land-based physical cultural practices as restorative process in Fisher River Cree Nation (Ochékwi Sipi). In B. Wilson, & B. Millington (Eds.), Sport and the environment (Research in the sociology of sport) (Vol. 13, pp. 85–101). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1476-285420200000013005

- Samad, S. (1998). State of minorities in Bangladesh: From secular to Islamic hegemony. Country Paper presented at Regional Consultation on Minority Rights in South Asia, 1998 (pp. 20–22).

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3). http://decolonization.org/index.php/des/index

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). University of Otago Press.

- Tom, M. N., Sumida Huaman, E., & McCarty, T. L. (2019). Indigenous knowledges as vital contributions to sustainability. International Review of Education, 65(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09770-9

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015). Honoring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 20(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.877708

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2018). Introduction: Born under the rising sign of social justice. In E. Tuck, & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Toward what justice? (pp. 1–17). Routledge.

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). (2007). A/RES/61/295. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

- Wildcat, M., McDonald, M., Irlbacher-Fox, S., & Coulthard, G. (2014). Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity. Education and Society, 3(3), I–XV.

- Wilson, S. (2007). What is an Indigenist research paradigm? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 30(2), 193.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.

- Yap, M., & Watene, M. (2019). The sustainable development goals (SDGs) and Indigenous peoples: Another missed opportunity? Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 20(4), 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2019.1574725