ABSTRACT

The need to provide novel but meaningful ways to reason and talk about an unprecedented crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a surge of creative metaphoric expressions in a variety of communicative settings. In order to investigate novel ways of conceptualizing the pandemic, we consider the metaphors included in the #ReframeCovid collection, a crowdsourced dataset of metaphors for the pandemic that rely on non-war frames. Its heterogeneous makeup of multilingual and multimodal examples (to date, over 550 examples – monomodal and multimodal in 30 languages) offers a unique opportunity to explore the ways in which metaphors have been used creatively to describe different aspects of the coronavirus pandemic. The patterns of metaphor creativity discussed in this paper include: creative realizations (verbal and visual) of wide-scope mappings, the use of one-off source domains, shifts in the valence of the source domain evoked, and the exploitation of source domains that are specific to particular discourse communities. The analysis of multimodal examples contributes to our understanding of the role of metaphor in sense-making and communication at a time of an extraordinary global crisis and will also provide new insights into metaphor creativity as a multidimensional phenomenon that integrates conceptual, discursive and cultural factors.

Exploring patterns of creativity in the use of metaphors for Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has created challenges for communication, thinking and well-being that have been met, in part, by means of creative metaphors, which are the topic of this paper. We draw from a crowdsourced dataset of metaphors for Covid-19 – the #ReframeCovid collection – to explore the different ways in which metaphors have been used creatively in the first six months of the pandemic, and the rhetorical purposes that creative metaphors have served.

Metaphors are central to our everyday interactions and cognition because they make it possible to communicate and talk and think about one thing in terms of another, based on perceived similarities or correspondences. Crucially, each metaphor highlights some aspects of the relevant topic or experience and backgrounds others. Metaphors can help bridge the gap between what we know and what we seek to know by making the strange look familiar, or, conversely, providing a novel angle on what is familiar. Creative metaphors, in particular, can provide new perspectives on our experiences and therefore, as argued by Hidalgo-Downing (Citation2020, p. 8), they can potentially shape new discourses and social practices.

This aspect of creative metaphors is particularly relevant in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, where there was a sudden and unexpected need to understand and cope with a new situation that upended people’s lives around the globe. This has resulted in the emergence of a wide range of diverse metaphors to reason about different aspects of the pandemic, as well as to heighten or mitigate its negative emotional impact. Since March 2020, we have been “fighting a war”Footnote1 against an “invisible enemy”Footnote2 that came in “waves”Footnote3; health workers became “soldiers at the frontline”Footnote4; “herd” immunity became the center of an agitated debate in the media; our “hibernating”Footnote5 economies had to be “restarted”Footnote6 to “activate”Footnote7 countries after months of lockdown; and regions faced intermittent “firebreaks”Footnote8 and “lockdowns” to bring down infection rates. We have also seen pictures of curves that had to be “flattened”Footnote9 (even “hammered”Footnote10), “traffic-light” color-coded mapsFootnote11 to show the areas with greater incidence of the virus; and cartoons of the virus displaying various human featuresFootnote12 to illustrate how it spreads and can be dealt with.Footnote13

As can be seen, these metaphors are diverse in their source and target domains and, more importantly, in terms of conventionality and novelty. Whereas MACHINE metaphors (e.g. “restart” the economy) are entrenched in everyday discourse and used in conventional ways, other examples are more creative, such as the reference to a brief lockdown (which is a metaphor in itself) as a “firebreak.” In this paper we focus on such creative examples.

We combine conceptual and discursive perspectives to explore different verbal and visual manifestations of metaphorical creativity in relation to Covid-19. Our goal is to show the different ways in which creative metaphors can provide novel, and often urgent, perspectives on the pandemic, including, in some cases, by targeting very specific audiences. Our data is drawn from the #ReframeCovid collection of metaphors, a one-of-its-kind dataset of metaphors crowdsourced during the pandemic. The #ReframeCovid initiative started on Twitter in March 2020, with a call for alternatives to WAR metaphors, which were widely used, and equally widely criticized as inappropriate and problematic, at the beginning of the pandemic. This call quickly led to the creation of a crowdsourced dataset of metaphors for different aspects of the pandemic other than WAR metaphors. The dataset has been built collaboratively since March 2020. At the time of writing (February 2021), the dataset consists of 550 metaphors in over 30 languages drawn from a wide range of genres and modes, with verbal, visual and multimodal examples (see Olza et al. Citation2021 for a detailed account of the initiative and its future potential).

The original goal of the initiative was to raise awareness of the (ab)use of WAR metaphors in the discourse about the pandemic. Therefore, the contributions reflected both alternative conventional metaphors for negative events (e.g. difficult journeys or monsters) and creative ways to conceptualize the pandemic, which are the focus of the present study.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews different ways in which creativity has been defined and operationalized in the scientific literature and in the literature on metaphor, to show that a comprehensive approach to creativity needs to integrate conceptual, discursive and cultural factors. We then illustrate several patterns of metaphorical creativity, with case studies that reflect unusual realizations of wide-scope source domains (Section 3.1) and creative exploitation of one-off source domains (Section 3.2). We close this paper (Section 4) with reflections on the role of creative metaphors during the pandemic and the implications of the study for a better understanding of metaphorical creativity.

Approaches to creativity and metaphor

The phenomenon of creativity has been approached from many different perspectives, including psychology, cognitive science, philosophy, and education (for a review, see Kaufman & Sternberg, Citation2019), with each perspective involving different definitions, questions, and sources of data. However, as Kauffman and Glăvenau (Citation2019, p. 27) put it, there is “reasonable consensus” that creativity “is something both new and task-appropriate.” Sternberg and Lubart (Citation1999, p. 47) influential definition captures this consensus as follows:

Creativity is the ability to produce work that is both novel (i.e. original, unexpected) and appropriate (i.e. adaptive concerning task constraints).

This tension between originality and appropriateness is also central to theorizing and analyzing metaphoric creativity (cf. Giora et al., Citation2004).

As with creativity generally, however, there are different approaches to what counts as a creative or novel metaphor, as well as a general recognition that there is no clear-cut line separating conventional and creative metaphors (e.g. Vega Moreno, Citation2007). In what follows we begin with cognitive accounts of creative metaphors, drawing from Conceptual Metaphor Theory and Blending Theory, and then consider the contribution of studies that focus on the manifestation of metaphors in discourse.

Within Conceptual Metaphor Theory, metaphorical creativity has tended to be associated with novel exploitations of conventional conceptual metaphors. Lakoff and Turner (Citation1989) identify four main ways in which this can happen in poetry in particular, but the same phenomena can in fact be observed in many different genres:

Extension – exploiting a normally unused element of the source domain of a conventional conceptual metaphor, such as Covid-19 as a train that causes more problems when it makes “a long stop” in a particular place (see section 3.1.1).

Elaboration – realizing in an unusual way the source domain of a conventional conceptual metaphor; e.g. the UK Prime Minister’s description of the virus as an “invisible mugger” can be described as an elaboration of the metaphor “DIFFICULTIES ARE OPPONENTS”.

Combination – bringing together two conventional conceptual metaphors; e.g. the Irish Prime Minister’s statement in May 2020 “Coronavirus is a fire in retreat; but it is not defeated. We must extinguish every spark, quench every ember” combines the source domains of FIRE and WAR in the description of the virus.

Questioning – explicitly calling into doubt the appropriateness of a conventional conceptual metaphor, often involving, in the local discourse context, what has more recently been called overt “resistance” to the presuppositions and entailments of a particular metaphor (Renardel De Lavalette, Andone, & Andone, Citation2019); e.g. a UK journalist commenting “I’m not sure who this register of battle and victory and defeat truly aids”.Footnote14

In the founding text of Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Lakoff and Johnson (Citation1980) also discuss the possibility of what is arguably the most radical form of metaphorical creativity, namely, the establishment of entirely original connections between concepts or images. Lakoff and Johnson’s main example is “LOVE IS A COLLABORATIVE WORK OF ART” – a novel unidirectional mapping between a source and a target domain (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980, p. 142ff.). This hypothetical conceptual metaphor provides a fresh conceptualization of love (or, to be more precise, romantic relationships) because its entailments are different from those of conventional conceptual metaphors such as “LOVE IS A JOURNEY” or “LOVE IS MADNESS,” including, for example, the idea that relationships are, at least to some extent, under the lovers’ control. On the other hand, this metaphor is appropriate because it explains and reinforces the notion that romantic relationships require some degree of cooperation from the people involved. The metaphorical description of the coronavirus as “glitter,” which we discuss in section 3.2.2, involves precisely this kind of entirely novel connection between two concepts.

To proceed, image metaphors consist of mappings between visual images, based on visual similarities (Lakoff & Turner, Citation1989; Ruiz de Mendoza & Pérez, Citation2011), but can also involve original source-target mappings. In fact, the origin of the term “coronavirus” itself is an image metaphor: the surface of the virus cells (seen through a scanning electron microscope) is covered in small protein spikes that resemble a crown, which, in Latin and some contemporary Romance languages, translates as “corona.” This is an example of metaphoric creativity performing a lexical gap filling function, i.e. creating a name for a new entity based on a similarity with a familiar entity (Goatly, Citation2011).

Creative uses of metaphors cannot, however, always be fully accounted for in terms of unidirectional mappings between conceptual domains or visual images, as they can involve novel combinations of elements from multiple sources. Explanations of metaphors as interactions and implication complexes between different conceptual structures have a long history (e.g. Black, Citation1962), but have been further developed in Fauconnier and Turner’s (Citation2002) Blending Theory. In this approach, metaphors involve the selective combination of elements from different mental representations known as input spaces into a blended space. The input spaces correspond to the topic or target of the metaphor, one or more sources, and a generic space that captures the structural similarities among source and target spaces. In the blended space, the interaction of elements from different inputs results in an emergent structure, i.e. new meanings that are not mapped from any of the inputs. We provide some examples in section 3.1.

From a lexical and textual perspective, metaphoric creativity has been described and operationalized with reference to individual words or expressions, textual patterns, and genres or discourse communities (see Goatly, Citation2011).

At the level of the word, or multi-word linguistic expression, a distinction can be made between cases where a particular metaphorical use is so conventional as to be included in dictionaries (e.g. “marathon” used to describe problems such as Covid-19, which take a long time to deal with; Macmillan English Dictionary) and cases where a particular metaphorical use is a one-off (e.g. the virus being described as a “spiritual inoculation,” to suggest that, in the long term, it could have positive effects on societies). Goatly (Citation2011) uses the term sleeping metaphors for cases such as the former and active metaphors for the latter. These two cases are in fact the opposite ends of a cline of conventionality, with many metaphorical uses falling somewhere in the middle.

From a textual point of view, creativity in the use of metaphor also manifests itself in patterns of related metaphorical expressions. The traditional, textual, notion of extended metaphor (Werth, Citation1994), for example, involves the use, in the same stretch of text, of several expressions for a particular subject-matter that draw from the same metaphor scenario, as in this explicit comparison between dealing with the coronavirus and dealing with a forest fire, by virologist Chris Smith in a radio interview:

“The way that you stop a disease spreading is in the same way as if we have a forest fire and we want to stop the fire, pouring water on it immediately where the fire is doesn’t actually work, you’ve got to get downwind of the fire and you rob it of fuel, you create a fire break by cutting the trees down.” (30/9/2020, added by Elena Semino)Footnote15

Another type of creative pattern involves the repeated use of the same source domain or metaphorical mapping across a text, resulting in an overarching figurative theme that has been described as a megametaphor (Werth, Citation1999).

Studies of metaphors as realized in different modes have identified creative manifestations of metaphoricity in pictorial and gestural modes as well as in the interaction between verbal and visual metaphors (e.g. Forceville & Urios-Aparisi, Citation2009; Pérez-Sobrino, Citation2017). For example, Forceville (Citation1996) coins the term hybrid pictorial metaphor for cases where a single visual entity combines elements of both a source and target concept, such as a boat’s sail looking like a face mask in a cartoon we discuss in in section 3.1.1.

From a genre point of view, creativity in metaphor use can in some cases only be properly accounted for in relation to the discourse community that produces and/or receives particular types of texts (e.g. Caballero, Citation2017), as discussed in section 3.2.3. For example, the use of “host” to refer to a living entity affected by a virus is conventional in immunology but may be perceived as novel by a non-expert.

Overall, these different approaches to metaphoric creativity are not mutually exclusive, but rather have overlaps and complementary strengths and weaknesses. For example, novel source-target mappings, as well as Lakoff and Turner (Citation1989) four types of novel exploitations of conventional metaphors are defined in conceptual terms but inevitably involve creativity at the lexical and textual levels when realized in language. While some instances of creativity can be explained in terms of unidirectional source-target mappings, others are better accounted for in terms of Blending Theory (see section 3). Moreover, without taking into account the knowledge and genres associated with different discourse communities, we cannot explain differences in accessibility or perceptions of creativity of the same metaphors by different audiences (see also Caballero, Citation2006; Deignan, Littlemore, & Semino, Citation2013). Kövecses (Citation2010) provides a Conceptual Metaphor Theory account of a form of metaphorical creativity where the choice of source domain is induced by some aspect of the context in which communication takes place, including the physical, social and cultural settings, and participants in the discourse (see also Koller, Citation2004; Semino, Citation2008 for the notions of topic-triggered and situation-triggered metaphors, respectively). This applies, for example, to a tweet about the newly-released efficacy data for a coronavirus vaccine that was posted by a US-based doctor immediately after the 2020 US presidential election illustrated in (1):

90% efficacy is far better than even most optimistic projections. An election analogy: these are CA results, rather than PAFootnote16

At the time, the result of the vote in California (CA) was rapidly and decisively declared in favor of Joe Biden (against incumbent Donald Trump), while the result for Pennsylvania (PA) was very close, contested and delayed. In Kövecses’s (Citation2010) terms, the (creative) choice of the US presidential election as a source domain for the efficacy of the vaccine (clear-cut good news, assuming an anti-Trump perspective) is induced by the political and historical context of that particular US election.

In what follows, we combine these different perspectives to discuss the main patterns of metaphorical creativity we have identified in the #ReframeCovid collection.Footnote19

Creativity in action in the #ReframeCovid collection

In this section we begin with creative uses of source domains that are often conventionally exploited, in English and other languages, to talk about problems and difficult enterprises, namely JOURNEY and FIRE. We then turn to examples of original mappings where the source domain or concept is not part of conventional conceptual metaphors. Our analyses show how the #ReframeCovid collection makes it possible to appreciate the ways in which metaphors have been used creatively to highlight different aspects of the pandemic, convey urgent messages, combine a lighthearted tone with serious messages, counter dominant framings, and reach different audiences. We should also add that the collection may well have an inherent bias toward creativity, as observers of metaphor use are more likely to add examples to the #ReframeCovid spreadsheet if these are in some way interesting and striking rather than highly conventional.

Creative realizations of conventional conceptual metaphors: wide-scope source domains and Covid-19

The #ReframeCovid collection contains many examples where conventional conceptual metaphors are used creatively to convey specific messages and perspectives in relation to Covid- 19. In this section we consider examples that can be traced back to source domains that, across different languages, have a wide metaphorical scope, i.e. are conventionally applied to many different target domains: JOURNEY and FIRE (Kövecses, Citation2002, p. 107ff.). More specifically, at the time of writing JOURNEY metaphors were one of the two most frequent types of metaphors in the collection, alongside SPORTS metaphors (74 examples each, with examples of JOURNEY metaphors from 19 of the 30 languages represented in the collection). In contrast, FIRE metaphors were less frequent (12 examples from 8 different languages), but the FIRE source domain has been described as “a common source domain for many target concepts” (Kövecses, Citation2002, p. 112; see also Charteris-Black, Citation2017) and as particularly appropriate and versatile with regard to Covid-19 specifically (Semino, Citation2021). For each source domain, the examples we discuss were selected so as to exemplify different types of metaphoric creativity.

The JOURNEY source domain

A long stop of the Coronavirus train

On 11th May 2020, a TV anchor on Al Arabyia TV commented on the rising number of Covid-19 infection in the United States as illustrated in (2):

ﺎر ﻛﻮروﻧﺎ ﻣﺮ ﺑﺪول اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻢ أﺟﻤﻊ ﻟﻜﻦ اﻟﻮﻻﯾﺎت اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة ﻛﺎﻧﺖ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ وﻗﻮف طﻮﯾﻠﺔFootnote17

“The Corona train crossed the whole world, but the United States station was a long stop”

Metaphorical descriptions of the virus as a moving object, and specifically as a train traveling toward different parts of the world, occur several times in different languages in the #ReframeCovid collection. Such metaphors draw from the broad source domain of JOURNEY, which is conventionally applied across languages to a wide range of target domains, including LIFE, RELATIONSHIPS, ILLNESS, among others. Its central function to present changes of state as movement and purposes as destinations has been explained in terms of the event-structure metaphor (Lakoff, Citation1993; Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1999) and of primary metaphors including “STATES ARE LOCATIONS” and “CHANGE IS MOTION” (Grady, Citation1997; Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1999).

In (2), the metaphorical description of widespread contagion as the coronavirus train crossing the whole world is relatively conventional. However, the use of “long stop” to suggest a particularly high rate of infection in the US exploits a normally unused element of the (train) JOURNEY source domain, resulting in what Lakoff and Turner (Citation1989) call extension of a conventional conceptual metaphor. A further aspect of creativity in context lies in the significance of “long stop.” Normally, a long stop on a journey is a problem for those who are traveling, as it delays reaching their destination. Here, in contrast, it is a problem for those who live in the location of the long stop, because the coronavirus train reaches its aim of causing infections and, the longer it stops, the more serious are consequences of this stop.Footnote18

A face mask for a sail

The cartoon in , by Iranian cartoonist Alireza Pakdel, also involves a (visual) JOURNEY metaphor. Here, however, the journey is by sea; the travelers are human beings (metonymically represented by a family on the boat); the virus is a rough sea that imperils the safety of the small sailing boat that the family are on (as suggested by the presence of objects looking like magnified coronavirus cells among the waves); and the journey has a destination, represented by a virus-free coastline and blue skies, which the people on the boat are looking and pointing at. Although the specifics of the visual image add an overall element of originality to the image, the idea of problems as rough terrains/seas and solutions as safe destinations is conventional. Against this conventional basis, a striking element of creativity is provided by the fact that the sail on the boat looks like a giant face mask. It is this creative element that is the point of the cartoon. Creativity, in this case, can be explained as a blend in which the object that enables the reaching of the destination (the boat’s sail) is merged with an object that has been suggested as a way to keep oneself and others (relatively) safe from the virus (a face mask). The two objects can both be made of cloth and look sufficiently alike for the visual blend to work; in addition, both are a means to an end – reaching a destination for the sail and preventing contagion for the face mask (cf. the notion of generic space in Blending Theory). Their differences, however, particularly in terms of size, result in a visual incongruity (cf. Forceville’s (Citation1996) hybrid pictorial metaphors) that is presumably intended to draw viewers’ attention and convey the crucial message that face masks should be worn by everyone to be safe from the virus and help stop the pandemic (cf. the notion of the blend having emergent structure).

In both examples discussed in this section, the virus is a hard-to-control entity (a train that stops of its own accord, a stormy sea) within a JOURNEY metaphor, and creative elements are introduced to convey specific points about the pandemic, i.e. how it affects different countries differently, and how face masks can provide protection. In the cartoon in , the face mask/sail is the instrument that human beings can use to exercise control on their situation and achieve their goal.

The FIRE source domain

Reclaiming the soil after the coronavirus fire

On 28th March 2020, Italian commentator Paolo Costa published a blog post entitled “Emergenza coronavirus: Non soldati ma pompieri” (“Coronavirus emergency: not soldiers but firefighters”).Footnote20 As anticipated by the title, in the course of the piece, Costa explicitly questions and resists WAR metaphors as inadequate and counterproductive, and proposes instead a view of Covid-19 as a (forest) fire.

While the source domain of FIRE is conventionally used, amongst other things, to describe fast-developing problems (e.g. “inflation spreads like wildfire through the economy,” from the Oxford English Corpus), Costa’s application of this source domain to Covid-19 is creative in terms of both textual and conceptual extension. Here we will focus on the beginning of Costa’s development of the metaphor as illustrated in (3), immediately following a description of the Covid-19 challenge as an “enormous cooperative enterprise” (“un’enorme impresa cooperative”):

(3) Non solo ci sono continuamente focolai da spegnere e, quando la sorte si accanisce, giganteschi

fronti di fuoco da arginare, ma è dovere di tutti collaborare quotidianamente alla bonifica del

terreno affinché scintille, inneschi, distrazioni più o meno colpevoli non provochino adesso o in

futuro disastri irreparabili.

“Not only are there constantly outbreaks to extinguish and, when our luck gets worse, gigantic fronts of fire to control, but it is everyone’s duty to collaborate daily in the reclamation of the soil so that sparks, triggers, more or less guilty distractions do not cause irreparable disasters now or in the future.”

Costa’s reference to the reclamation of the soil exploits an element of the FIRE source domain that is not conventionally used when problems are described as fires. As such, this is another case of extension of a conventional metaphor in Lakoff and Turner's (Citation1989) sense. This original use of the source domain is particularly interesting and appropriate because it captures an aspect of the pandemic that can be potentially overlooked, in the midst of the crisis, namely that it may be necessary for everyone to act and live differently in the longer term in order to prevent future pandemics. Such future-oriented and collaborative framing of the pandemic is a crucial affordance of the FIRE source domain, as compared with, for example WAR or JOURNEY source domains.

A line of matches catching fire

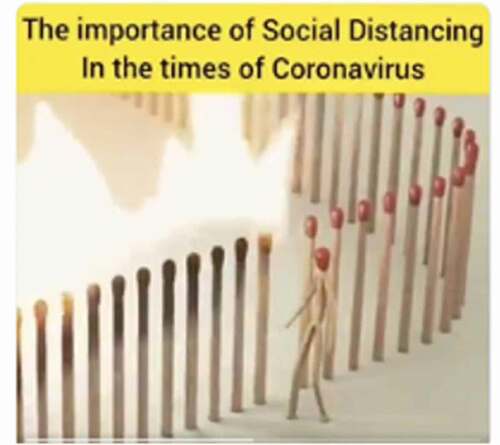

We now turn to another creative visual exploitation of the FIRE source domain that aims to convey a public health message, in this case to do with social (or rather physical) distancing as a way to avoid contagion. is a still from a short video that was in wide circulation on social media in March 2020.Footnote21 It shows a line of matches catching fire one after the other until one of them, which is shaped like the outline of a human being, steps out of the line and thereby stops the fire.

While the notion of contagion as a fire that spreads from one person to another has become increasingly conventional during the pandemic, the scenario in this short film does not correspond to a familiar experience, as matches are not normally positioned in that way. Rather, the scene presented in the video can be explained as a blend of different input spaces involving: matches that progressively catch fire if positioned close to one another; a line of dominoes (see also Nerlich, Citation2020), where the fall of one piece causes the rest to fall one after the other; and people standing close to one another, possibly in a queue. The point of the video is the emergent structure of the blended space, namely that physical distancing between people is needed to stop contagion. Crucially, the fact that the one match that steps out of line is visually personified with arms and legs makes clear that the message is about human behavior and human life. Accordingly, the caption for the video makes explicit mention of social distancing. In both cases discussed in this sub-section, FIRE metaphors are used creatively to convey the need for action on the part of individual citizens, short term in the case of social distancing and longer term in the case of the metaphorical reclamation of the soil (cf. also the use of the term “fire break lockdown” in Wales in Autumn 2020; and Semino, Citation2021) for a discussion of FIRE metaphors for Covid-19). In the next section we turn to cases of metaphorical creativity where the source concept

or scenario cannot straightforwardly be subsumed under wide-scope source domains and conventional conceptual metaphors.

Creative exploitation of one-off source domains for Covid-19

We now turn to examples of creative metaphors in the #ReframeCovid collection that do not draw from wide-scope source domains, but rather from concepts that are not conventionally exploited as metaphorical sources in the relevant language, resulting in one-off mappings. We show how, besides being highly creative, these examples make serious points about the pandemic in a light- hearted manner. The combination of creativity and lightheartedness potentially has an important function. Creative metaphors, by definition, avoid the potential loss of rhetorical power that may come from overuse (Flusberg, Matlock, & Thibodeau, Citation2018, p. 9), as well as providing fresh perspectives; light-hearted metaphors, in addition, can convey important messages about the pandemic without increasing anxiety and pessimism, at a time when these are already widespread.

“Acting like a hedgehog”

In late April 2020, a Norwegian newspaper article described “heroic” behavior in Covid-19 times as in (4):

(4) … hvis man skal være helt i dise tider, skal man gjøre som pinnsvinet. Ikke brøle som en løve eller slås som en titan, men rulle seg sammen og vente, håper på bedre tider https://www.nrk.no/osloogviken/xl/derfor-er-pinnsvinet-helten-i-korona-tiden-1.14958647(24/4/2020, added by Susan Nacey). .

“ … if one is going to be a hero in these times, one should act like a hedgehog. Don’t roar like a lion or fight like a giant, but roll up in a ball and wait, hope for better times.”

This example contrasts with the ones seen in section 3.1 for two reasons. First, even though “PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS” is a conventional conceptual metaphor in Norwegian as in many other languages, HEDGEHOG is not a conventionally used source domain in that language. Second, it is an unlikely source domain to convey heroic behavior. The reason why this mapping is appropriate in this context is made explicit by questioning more prototypical “heroic” behaviors which involve intense activity and aggression (“don’t roar like a lion or fight like a giant”). Rolling up into a ball and waiting is not to be understood as an illustration of active resting (as it is the case with conventional HIBERNATION metaphors), but rather as an act of endurance and resilience.

The contrast between, on the one hand, hedgehogs and their potentially endearing behavior, and, on the other hand, prototypical heroic behavior as exemplified by lions and giants, results in a lighthearted tone. However, the metaphor makes a very serious point about the behavior that the population needs to adopt to reduce the transmission of the virus, for their own benefit and that of others. Without a clear prospect of the end of the pandemic, reactive behaviors, such as those more typically associated with lions and giants, are not appropriate to convey the need to adopt self-limiting behaviors, such as staying at home, for long periods of time. This has been pointed out as one of the main shortcomings of WAR metaphors in the context of the pandemic (Sabucedo, Alzate, & Hur, Citation2020, p. 619). The stark contrast established between the explicit questioning of aggressive behaviors with the behavior of hedgehogs (signaled by the formulation in terms of a simile) prompts a creative tension that invites us to reconsider the value of being patient and quiet as an act of heroism and endurance in times of the pandemic.Footnote22

“Coronavirus is like glitter”

An even clearer, and even more lighthearted, example of the exploitation of one-off source domains for the coronavirus involves glitter, as illustrated in (5):

(5) Coronavirus is like glitter: Even when you think you got rid of it, it shows up again in random

places (5/3/2020, added by Veronika Koller).

GLITTER is not only an unusual source domain, but also another unexpected and non- threatening concept that, in principle, makes for an unlikely candidate to convey the persistence and invisibility of the virus, due to its festive associations with parties and celebrations.

However, the fact that the ground of comparison is made explicit (once again, through a simile) draws our attention to a very specific aspect of glitter – one that is associated with the aftermath of parties, and that is particularly relevant to understanding two important aspects of the virus: its persistence (“even when you think you got rid of it”) and the unexpected places where it appears even after one thinks it had been completely removed (“it shows up in random places”). In context, therefore, the festive connotations are backgrounded to convey a very serious point about the need to avoid complacency because of the ways in which the virus spreads, and hence the need to change our behavior accordingly to prevent infections. Nonetheless, those positive associations of the source domain, or, minimally, the absence of negative ones, help to convey a serious point in a non-threatening way, and make this metaphor particularly appropriate for specific groups of the population, such as children, who are familiar with glitter but who may not be suitable recipients for more negative frames (e.g. wars or natural disasters). The tensions in emotional valence and evaluation between source and target domain are therefore a particularly interesting, and, potentially, rhetorically useful aspect of this metaphor.

Discourse community specific source domains

We now turn to cases of one-off metaphorical source domains that, unlike HEDGEHOG and GLITTER, draw from specialized areas of knowledge and can be partly explained in terms of the audiences that are being addressed or represented (cf. Kövecses’s (Citation2010) notion of context-induced metaphorical creativity). Our first example in (6) involves music, and was shared on social media by Classic FM – a UK-based private radio station dedicated to classical music:

(6) Social distancing is like asking a string section to play pianissimo: it only works if everyone does

it. https://twitter.com/classicfm/status/1243472908581777408?lang=en(27/3/2020, added by

Laura Filardo)

Playing “pianissimo” (in other words, very quietly) is one of the greatest challenges in orchestras, especially for the string section, which is the largest section of the orchestra and also closest to the audience. The simile in (6) exploits the idea that just one instrument not playing pianissimo undermines the efforts of all the other musicians who are doing so. In the same way, one person or a few people not socially distancing undermine the efforts of everyone else. The metaphorical comparison thus highlights the necessity for joint responsibility and social discipline. Because of its intangible nature, MUSIC tends to be the target of metaphorical mappings (Julich-Warpakowksi, Citation2019; Zbikowski, Citation2008), rather than the source. The specific scenario of an orchestra playing pianissimo is an even more unconventional choice, resulting in a highly creative mapping.

Similarly to examples (4) and (5), orchestras and playing music have positive associations, even though what is being highlighted is a challenge in the performance of musical pieces. In contrast to examples (4) and (5), however, this metaphor is clearly more appropriate for musicians or those with experience in that field, as they are familiar with the relevant scenario and associated terminology. People without the requisite knowledge may not perceive any noticeable association between playing music and social distancing, particularly if jargon (“pianissimo”) is involved. As noted above, the simile was posted on social media by a classical music radio station, and it is therefore safe to assume that some background knowledge can be expected from their audience. Specialized metaphors can be useful to appeal to specific groups of people (just as we argued in section 3.2.2 that glitter could be particularly useful to engage with children).

Our final example in (7) appeared in the Spanish press to frame the reopening phases after the pandemic, and appeals to a different audience:

(7) Los Juegos del Hambre autonómicos https://www.eldiario.es/politica/coronavirus-fernando-simon-desescalada_1_5966418.html(9/5/2020, added by Ana Belén Martínez García)..

“The regional Hunger Games”

People who have not read the trilogy of novels The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (2008– 2020) may not understand that what the reporter conveys is the fierce battle of the regions to reopen their local businesses after the lockdown, to avoid further economic damage. This kind of reference to popular culture may resonate more strongly with adolescents (the primary target audience of the films), although that does not necessarily render these references meaningless for a wider community of speakers.

Conclusions

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused illness, death, and social and economic disruption on a global and unprecedented scale, for anyone currently alive on the planet. The #ReframeCovid collection provides an opportunity to appreciate and study the importance of metaphor as a way of making sense of, and communicating about, such an overwhelming phenomenon. This is indeed a time when multiple perspectives, as provided by different metaphors, are absolutely crucial for individuals and societies. By focusing on creative uses of metaphors from the dataset, we have highlighted more specifically the conceptual and rhetorical pressures caused by the pandemic, and the ingenuity of speakers, writers and designers in using metaphors creatively to deal with those pressures. Of course, not all metaphors are successful or well-meaning. The examples we have discussed, however, were selected to demonstrate both originality of different kinds and appropriateness in context, to convey different messages at different junctures for different audiences.

While we have relied on existing accounts of metaphorical creativity to select and analyze our examples, we have also pointed out phenomena that have not been discussed in previous studies. We have shown particularly the use of novel one-off mappings with lighthearted associations to make serious points about the need for sacrifice and vigilance during the pandemic. We have suggested that these creative metaphors are particularly appropriate in the context of Covid-19, as they provide fresh perspectives on crucial aspects of the pandemic without directly contributing to anxiety and pessimism by conveying negative evaluations. Evaluation is well known to be an important function of metaphor (Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Citation2013; Littlemore, Citation2019; Semino, Citation2008), and creative metaphors in particular have been found to be more likely to convey evaluation than conventional metaphors and non-metaphorical statements (Fuoli, Littlemore, & Turner, Citation2021). Our examples of one-off mappings balance generally positive associations with a highly negative subject matter in ways that are particularly appropriate at a time when behavior change may be undermined by growing gloominess and fatalism.

Our discussion of community-specific choices of one-off source domains contributes to a substantial existing literature on variation in metaphor use according to audience, genre, and discourse community, although that literature tends to focus on patterns of metaphor that are conventional for specific groups, rather than the choice of source domains familiar to specific groups. Research shows that the personal resonance of the source domain can have a positive impact on the framing effects of metaphors (Landau, Arndt, & Cameron, Citation2018). In the context of a long-term pandemic, this could be an important consideration in public health messaging.

Overall, our study provides further evidence that both metaphor and creativity are crucial cognitive and communicative tools, especially in the presence of a new and overwhelming crisis. In addition, the fact that this study has been made possible by a crowdsourced process of data collection and sharing will hopefully provide inspiration for future initiatives, for the benefit of researchers and society more generally.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

13 For a more comprehensive review of Covid-19 language, see: https://wakelet.com/wake/201b93ed-5f55-46c0-9148-26cb11c4c812

14 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/07/horror-coronavirus-real-imaginary-war-britain

15 We cite examples from the #ReframeCovid dataset following this structure: source (date, contributor).

19 https://www.instagram.com/p/B9OsjmunEaw/(2/3/2020, added by Zoe Gravani).

17 https://www.alarabiya.net/ar/alarabiya-today/2020/05/11/ﻷاﺑﯿﺾ-ﻟاﺒﯿﺖ-ادﺧﻞ-ﻮﻛروﻧﺎ-ﺎرﯾﻌﺔ-ﻟاﻌﺮﺑﯿﺔ-ﻲﻓ-.html (11/5/2020, added by Sami Chatti).

18 We are grateful to Tasneem Solie for help with this example.

20 https://www.settimananews.it/societa/emergenza-coronavirus-non-soldati-ma-pompieri/ (28/3/2020, added by Elena Semino).

21 https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/health-news/viral-match-video-shows-how-social-distancing-can-save-lives/ar-BB11gtMi (16/3/20, added by Elena Semino)

22 We thank Susan Nacey for her help with this example.

References

- Black, M. (1962). Models and metaphors: Structure in language and philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Caballero, R. (2006). Re-viewing space: Figurative language in architects´ assessment of built space. En re-viewing space. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. Retrieved from https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/17776

- Caballero, R. (2017). Genre and metaphor: Use and variation across usage events. In E. Semino & Z. Demjén (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 193–205). London: Routledge.

- Charteris-Black, J. (2017). Fire metaphors: Discourses of awe and authority. London: Bloomsbury.

- Deignan, A., Littlemore, J., & Semino, E. (2013). Figurative language, genre and register. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. New York: Basic Books.

- Flusberg, S. J., Matlock, T., & Thibodeau, P. H. (2018). War metaphors in public discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 33(1), 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1407992

- Forceville, C. (1996). Pictorial metaphor in advertising. London: Routledge.

- Forceville, C. J., & Urios-Aparisi, E. (2009). Multimodal metaphor. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110215366

- Fuoli, M., Littlemore, J., & Turner, S. (2021). Sunken ships and screaming banshees: Metaphor and evaluation in film reviews. English Language and Linguistics, 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674321000046

- Giora, R., Fein, O., Kronrod, A., Elnatan, I., Shuval, N., & Zur, A. (2004). Weapons of mass distraction: Optimal innovation and pleasure ratings. Metaphor and Symbol, 19(2), 115–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms1902_2

- Goatly, A. (2011). The language of metaphors. London: Routledge.

- Grady, J. (1997). Foundations of meaning: Primary metaphors and primary scenes (Doctoral dissertation). California, USA: University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3g9427m2

- Hidalgo-Downing, L. (2020). Towards an integrated framework for the analysis of metaphor and creativity in discourse. In L. H. Downing & B. Kraljevich Mujic (Eds.), Performing metaphoric creativity across modes and contexts (pp. 1–18). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Ibarretxe-Antuñano, I. (2013). The relationship between conceptual metaphor and culture. Intercultural Pragmatics, 10(2), 315–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2013-0014

- Julich-Warpakowksi, N. (2019). Why do we understand music as moving?: The metaphorical basis of musical motion revisited. In L. J. Speed, C. O’Meara, L. San Roque, & A. Majid (Eds.), Perception metaphors (pp. 165–184). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kauffman, J. C., & Glăvenau, V. P. (2019). A review of creativity theories. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (pp. 27–43). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaufman, J. C., & Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). (2019). The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Koller, V. (2004). Businesswomen and war metaphors: ‘Possessive, jealous and pugnacious’? Journal of Sociolinguistics, 8(1), 3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2004.00249.x

- Kövecses, Z. (2002). Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kövecses, Z. (2010). A new look at metaphorical creativity in Cognitive Linguistics. Cognitive Linguistics, 21(4), 663–697. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2010.021

- Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (2nd ed., pp. 202–251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.013

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. New York: Basic Books.

- Lakoff, G., & Turner, M. (1989). More than cool reason: A field guide to poetic metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Landau, M. J., Arndt, J., & Cameron, L. D. (2018). Do metaphors in health messages work? Exploring emotional and cognitive factors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 135–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.09.006

- Littlemore, J. (2019). Metaphors in the mind: Sources of variation in embodied metaphor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nerlich, B. (2020). Metaphors in the time of coronavirus. Retrieved from https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/makingsciencepublic/2020/03/17/metaphors-in-the-time-of-coronavirus/

- Olza, I., Koller, V., Ibarretxe-Antuñano, I., Pérez-Sobrino, P., Semino, E. (2021). The #ReframeCovid initiative: From Twitter to society via metaphor. Metaphor and the Social World 11(1): 99–121

- Pérez-Sobrino, P. (2017). Multimodal metaphor and metonymy in advertising. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Renardel De Lavalette, K. Y., Andone, C., & Andone, G. J. (2019). “I did not say that the government should be plundering anybody’s savings”: Resistance to metaphors expressing starting points in parliamentary debates. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(5), 718–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.18066.ren

- Ruiz de Mendoza, F., & Pérez, L. (2011). The contemporary theory of metaphor: Myths, developments and challenges. Metaphor and Symbol, 26(3), 161–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2011.583189

- Sabucedo, J.-M., Alzate, M., & Hur, D. (2020). Covid-19 and the metaphor of war (Covid-19 y la metáfora de la guerra). International Journal of Social Psychology, 35(3), 618–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2020.1783840

- Semino, E. (2008). Metaphor in discourse. Edición: 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Semino, E. (2021). “Not soldiers but fire-fighters” – metaphors and Covid-19. Health Communication, 36(1), 50–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1844989

- Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3–15). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vega Moreno, R. (2007). Creativity and convention: The pragmatics of everyday figurative speech. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Werth, P. (1994). Extended metaphor: A text-world account. Language and Literature, 3(2), 79–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/096394709400300201

- Werth, P. (1999). Text worlds: Representing conceptual space in discourse. Harlow: Longman.

- Zbikowski, L. M. (2008). Metaphor and music. In R. W. Gibbs Jr. (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of metaphor and thought (pp. 502–524). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816802.030