ABSTRACT

The impacts of trauma and violence are well documented, calling for trauma-responsive organizations and trauma-resilient communities. Organizations serving traumatized youth should focus on preventing and healing from trauma, building individual resilience, and responding to structural violence in the systems in which they operate. Grounded in theories on constructivist self-development, structural violence, and organizational social context, and utilizing a resilience framework, the Trauma Resilient Communities (TRC) Model aims to promote healing from the aftermath of trauma and violence within organizations and communities. Its goal is to improve organizational culture and climate through shared knowledge, understanding, language, practices, values, and culture to create safety for all stakeholders. The model’s theoretical framework is described, including a logic model addressing dynamics across all system levels.

Trauma is a physical and emotional response to individual or on-going threatening events (American Psychological Association, Citation2016; Loomis et al., Citation2019) or experiences of racism, poverty, and marginalization (American Psychological Association, Citation2016; National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Citation2015). Organizations that serve clients recovering from trauma are becoming increasingly aware of trauma’s complex and structural dynamics, making trauma-informed approaches an organizational imperative (Hummer et al., Citation2010). Trauma-informed approaches address complex trauma experienced at every level of an organization and the community as a whole, and aid the organization in providing care to clients (Hummer et al., Citation2010). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Citation2014) purports that a trauma-informed approach should be grounded in four assumptions and six key tenets. A trauma-informed organization is assumed to 1) realize the impact of trauma and understand pathways to recovery, 2) recognize the symptoms of trauma both in clients and staff in the organization, 3) respond by integrating trauma knowledge into the practices and policies of the organization, and 4) resist retraumatization in clients and staff. The key tenets include: 1) safety; 2) trustworthiness and transparency; 3) peer support; 4) collaboration and mutuality; 5) empowerment, voice, and choice; and 6) cultural, historical, and gender issues.

Existing research on trauma-informed organizational interventions and/or approaches highlights challenges and important considerations. An analysis of sites implementing trauma-informed care approaches and curricula (Hummer et al., Citation2010) found that most approaches focus on micro-level change, including trauma-specific interventions that address the needs of individuals who are traumatized to avoid retraumatization. Researchers identify that this is only one aspect of trauma-informed organizational culture change (J. S. Middleton et al., Citation2019). Additionally, research indicates that micro-level change efforts are not sustainable. For example, when restraints were reduced amongst children in a residential care setting, they were only reduced for a short amount of time (LeBel et al., Citation2004). Research regarding micro-level change efforts often excludes underserved, underrepresented client populations such as children of color and children with special needs (LeBel et al., Citation2004). Researchers emphasize the importance of focusing on organizational readiness, assessment, and change (Harris & Fallot, Citation2001; Rivard et al., Citation2005), facilitating cultural change in the organization, addressing gaps and barriers, and basing efforts on implementation science (Fixsen et al., Citation2005).

Models for Trauma-Informed Organizational Change

To address the impact of trauma on the individual client, staff person, and organization, a number of approaches exist. However, to date, a literature review reveals that only three specific evidence-informed models for trauma-informed organizational change have been implemented and tested across a variety of types of organizations: 1) The Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) Model; 2) the Children and Residential Experiences (CARE) Model; and 3) the Sanctuary Model.

Though these models address multiple systems of care (i.e., individual, family, school) as well as across organizations with trauma-informed practices and interactions, there are individual experiences and systemic issues not explicitly addressed by these models. The models outlined above do not specifically focus on the oppression that shapes the experiences of an organization’s staff or the clients being served. Furthermore, the models outlined above approach trauma-informed care for clients with a resilience lens without considering the need to dismantle the inherently and foundationally oppressive external systems that target and/or involve clients served by the organization to end the cycle of oppression and harm. The Trauma Resilient Communities (TRC) Model is currently being tested in a southern U.S. metropolitan city in response to escalating incidents of community violence. The current paper presents the model’s theoretical framework and proposed logic model. A deeper examination of the model’s implementation process and outcomes will be discussed in future publications. The TRC Model seeks to close the abovementioned gaps by 1) weaving together knowledge about trauma science, racial trauma, and equity, 2) promoting equity-based values and practices that are culturally adaptive, intersectional, and challenge dominant, white-centered culture, and 3) redefining resilience with an intentional focus on structural violence.

Theoretical Framework

The TRC Model is an organizational intervention that is grounded in constructivist self-development theory (CSDT; McCann & Pearlman, Citation1990; Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995), structural violence theory (Galtung, Citation1969), and organizational social context theory (Glisson, Citation2000, Citation2007; Glisson & Green, Citation2006; Glisson & Hemmelgarn, Citation1998; Glisson & James, Citation2002), utilizing a resilience framework (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1992; Ogbu, Citation1990) to promote healing from the impact of the aftermath of trauma (including racial trauma), adversity, and violence within organizations and communities. Its goal is to improve organizational culture and climate by educating staff on the effects of trauma and stress on behavior. This goal is to ultimately change the mind-set of staff regarding client’s behaviors from being pejorative (i.e., sick) to being the result of injury, and providing tools to change individual and group behavior. The theoretical framework addresses dynamics across all levels of the system, and by doing so, the model aims to improve the quality-of-service delivery and, ultimately, improve client outcomes.

Constructivist Self-Development Theory

Constructivist Self-Development Theory (CSDT; McCann & Pearlman, Citation1990; Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995) is an integrative personality theory that provides a framework for understanding the impact of childhood maltreatment on the developing self (Saakvitne et al., Citation2010). With origins in psychoanalytic theory, self-psychology, social learning, and cognitive development, this theory describes the unique impact of traumatic events that arise from interactions among aspects of the person, the event, and the context (Brock et al., Citation2006); thus, it is a constructivist theory of personality development. Because it highlights those aspects of development most likely to be affected by traumatic events, it is also a clinical trauma theory (Saakvitne et al., Citation2010).

CSDT describes three self-capacities: the ability to maintain a sense of connection with benign others (inner connection); the ability to experience, tolerate, and integrate strong affect (affect tolerance); and the ability to maintain a sense of self as viable, benign, and positive (self-worth). Drawing from theory and research on attachment (Bowlby, Citation1988), CSDT suggests that self-capacities develop through early relationships with caregivers and allow one to learn to regulate one’s inner state. The capacity to maintain a sense of connection with others is posited to form the basis from which the other self-capacities (affect regulation and a sense of self-worth) develop (Brock et al., Citation2006).

CSDT establishes the foundation for understanding the disruptions in social and behavioral functioning that accompany exposure to trauma and the strong relationship between attachment and emotion regulation. CSDT also drives the importance of maintaining a sense of connection to self (individual), the community (we), and the organization. The TRC Model draws from this knowledge and focuses on creating a community environment within the organizational system that allows clients to restore connections with others and staff to restore connections with each other and their work. A primary goal of establishing this organizational community environment is to develop multiple relationships and connections that will ultimately help clients, staff, and leaders regulate their internal states by normalizing grief and painful experiences and externalizing what is internal.

Structural Violence

Importantly, equity must be at the center of all trauma-informed change work (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Citation2014; Dhaliwal, Citation2016). Special attention must be paid to an organization’s commitment to anti-oppressive practices, including how individuals who represent underserved communities (e.g., Black, Indigenous and other People of Color; BIPOC) experience the organization’s culture and climate. This perspective is critically important in informing trauma-informed organizational culture change efforts in order to enhance organizational effectiveness and ultimately, client outcomes. While existing organizational change interventions may commonly include special attention to constructs such as organizational readiness for change, transformational leadership, secondary traumatic stress, supervisor support, and intent to leave, an extensive review of the literature reveals that trauma-informed organizational change interventions often do not account for the structural determinants of organizational health (J. Middleton et al., Citation2022), namely structural and institutional violence.

Structural violence refers to a form of violence wherein policies, social structures, or social institutions harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs (Galtung, Citation1969). Examples of structural violence can include but are not limited to ableism, classism, elitism, ethnocentrism, nationalism, racism, and sexism. Utilizing a parallel lens, institutional violence is most commonly defined as the use of power by an institution, such as an organization or a school, to cause harm and to enforce structural oppression (Rossiter & Rinaldi, Citation2018). Expanding upon psychologist Albert Bandura’s theory of situational moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation1999), Drs. Rossiter and Rinaldi (Citation2018) maintain that institutional violence is not caused by individual perversion. Rather, they claim particular organizational traits can lead to moral abandonment, which then can create “an ethos of violence.” They argue that these organizational traits are embedded within institutions, and thus institutional care is, by design, inherently violent. For Rossiter and Rinaldi, violent acts exist along a continuum, whereby institutionally sanctioned practices, such as the use of physical restraints, dampen staff members’ abhorrence to cruelty.

Institutional violence is a persistent and long-standing social condition within organizations (Better, Citation2002; Peterson & Zimmerman, Citation2004; Watts & Carter, Citation1991; Zimmerman, Citation2000) and relies on established, traditional ways of operating in which leadership is defined by historically white values and norms (Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2001). The organizational environment reflects and protects the cultural assumptions of the dominant group (e.g., institutionalizing the centering of whiteness) so that the practices of that group are seen as the norm to which all others should conform. Accepting this oppressive system as normative provides substantial advantages for the majority culture, including those who actively seek to eradicate oppression (Feagin, Citation2010). Embedding and embodying anti-oppressive organizational practices to combat the effects of institutional violence remains a challenge for most organizations. Yet, the hard work of exposing an institution’s structural biases (e.g., internalized racism) is critical to our efforts to create inclusive, trauma-responsive organizations. The TRC Model works with organizational communities to prepare the soil for courageous conversations that will challenge the structures that are violent and move toward disruption of the system as a whole. The TRC Model tools and values help organizations to embed language and develop organizational neural networks built upon trust, safety, and restorative practices. If these anti-oppressive neural networks are not developed, “diversity, equity, and inclusion” programming becomes nothing more than an intellectual exercise.

Organizational Social Context Theory

Organizational theory and research indicate that organizational health is represented by a number of overlapping dimensions, including workforce practices and outcomes (e.g., recruitment, retention, and workload), organizational climate, organizational culture, service patterns, and client outcomes. The social context of an organization is important to consider when assessing organizational health, as it helps to shape the implementation of quality services. Specifically, the social context of an organization includes the norms, values, expectations, perceptions, and attitudes of the members of the organization, all of which affect how services are delivered. An organization’s social context determines how things are accomplished in the organization and the psychological impact of the work environment on the professionals who work there (Glisson, Citation2007).

A significant body of empirical evidence indicates that organizational culture and climate play central roles in the social context of an organization (Glisson, Citation2000; Hemmelgarn et al., Citation2006). A number of studies in child welfare and mental health organizations link culture and climate to service quality, service outcomes, worker morale, staff turnover, the adoption of innovations, and organizational effectiveness (Glisson, Citation2002, Citation2007; Glisson & Green, Citation2006; Glisson & Hemmelgarn, Citation1998; Glisson & James, Citation2002). From this research, culture and climate have emerged as critical constructs in the conceptual model of organizational social context, first proposed by Glisson (Citation2007), and adapted by Middleton (Citation2011). As shown in , culture and climate are depicted as two important but distinct domains that mold the work attitudes and behaviors of the members of the organization and thus, affect the organization’s performance and success.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

An extensive literature review found consensus that culture depicts the way things are done in an organization, and climate depicts the way people perceive their work environment (Verbeke et al., Citation1998). This distinction suggests that culture is a property of the organization and climate is a property of the individual (Glisson, Citation2007) and has important implications for how health is measured within an organization. Culture, which is more difficult to change, is defined as the norms, expectations, and way things are done in the organization, and includes the values, beliefs, and assumptions shared by members of the organization (Glisson, Citation2007; Hofstede, Citation1980). Climate is separated into two reflexive domains: psychological climate and organizational climate. Psychological climate is viewed as the individual employees’ perceptions of the psychological impact of their work environment on their wellbeing. These perceptions can be modified with well-planned interventions (Hofstede, Citation1980). Organizational climate is created when individuals in a work unit, team, or organization share the same perceptions of how their work environment affects them as individuals (Glisson, Citation2007). In this manner, psychological climate directly informs organizational climate.

Organizational climate constructs such as stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy (Glisson et al., Citation2006) have been shown to be more strongly correlated with staff turnover than organizational culture constructs (DePanfilis & Zlotnik, Citation2008). Other research indicates that organizational climate relates to intention to leave and the quality of services and client outcomes (Bednar, Citation2003; Glisson & Hemmelgarn, Citation1998). Therefore, attention to climate might be expected to have a significant impact on an organization, doing much more than simply retaining workers. The TRC Model utilizes trauma-informed, resilience-building approaches and leadership coaching practices to create change within both climate dimensions: organizational climate and psychological climate.

Building on the work of organizational social context theorists such as Charles Glisson (Citation2007), this new conceptual model begins to account for the potential impact of structural violence and institutional violence on an organization’s culture and climate. As depicted in the model, structural violence is hypothesized to impact the organization’s culture and structure most directly. The organizational environment reflects and protects the cultural assumptions, then policies, practices, and/or procedures become embedded in the organization’s structure, and ultimately the organization commits institutional violence. As employees experience institutional violence individually and collectively, they embody the institution’s structural biases and make meaning of their experiences of institutional violence and compassion fatigue, which plays out in their work performance (e.g., attitudes and behaviors). This framework informs the design and implementation of the TRC Model, as it accounts for the impact of structural violence on organizational culture and climate. Understanding how institutional and structural violence impact organizational change efforts are critically important to creating long-lasting, equitable change. Through cultural humility and resilience-building approaches and strategies, the model aims to disrupt the impact of structural violence on the organization at the cultural and climate levels, ultimately enhancing performance and client outcomes.

Resilience Framework

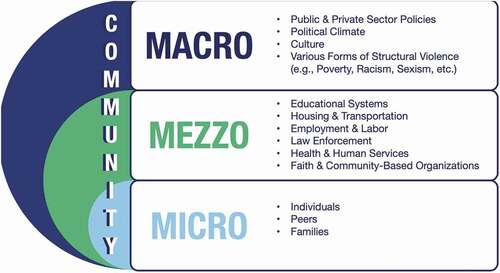

The illustration demonstrates the community context in which the work of the TRC Model is situated (see, ). The operating system or framework utilized to envision this work is a Resilience Framework, with the understanding that all of this work happens within the context of “community.” The Resilience Framework is informed by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994), which considers the interpersonal and environmental factors that affect individual and community development. In this way, community is defined at the micro, mezzo, and macro level. This approach is also informed by John Ogbu’s cultural-ecological approach (Ogbu, Citation1990), which looks at the study of institutionalized patterns of behaviors interdependent with features of the environment.

At the micro level, the TRC Model aims to impact individuals, peers, and families. At the mezzo level, the focus is on systems and institutions impacting communities, such as education, housing, transportation, employment/labor, law enforcement, health and human services providers, faith-based institutions, and community-based organizations. This is where the TRC Model focuses much of the initial initiative-development work. Macro level factors within the Resilience Framework include public (government) and private (corporations) sector policies; political climate; culture; and various forms of structural violence such as racism, sexism, and poverty. The Resilience Framework aims to impact the aftermath of trauma (including racial trauma), adversity, and violence at the macro, mezzo, and micro levels. By creating sustainable, trauma-informed organizational culture change, the TRC Model ultimately aims to prevent these forms of violence and trauma from occurring in the first place.

Building Trauma-Informed Organizations

Trauma has a powerful impact on individuals, organizations, communities, and entire systems. Organizations are impacted by chronic stress and organizational trauma and can become toxic environments that add more adverse experiences to those they serve rather than providing healing environments. Not only can organizations cause trauma or stress for clients, but such a working environment may also have a detrimental effect on the care providers, ultimately leading to compassion fatigue, vicarious and secondary trauma, and burnout. The TRC Model uses the current science of trauma resilience and organizational development to build trauma-responsive and trauma-resilient organizations. This is done by embedding a set of researched building blocks that, once embedded, create community protective factors (i.e., community immunity) that not only mitigate and protect clients, but also staff and the surrounding community from the impact of trauma (see, ). These trauma-informed building blocks (i.e., shared knowledge, shared language, shared understanding, shared values or commitments, and shared practices) serve as the foundation that ultimately leads to a shared trauma-informed, trauma-responsive culture.

Figure 3. The trauma resilient community model building blocks.

Shared Knowledge

Shared Knowledge focuses on a body of trauma research that is essential for every person or organization working with individuals affected by trauma to know. This includes Resilience Building, Equity and Justice, Adverse Childhood Experiences, Organizational Chronic Stress, Trauma Science, and Compassion Fatigue. These themes are embedded throughout the training curriculum and are delivered via eight modules.

Shared Understanding

Shared Understanding focuses on deepening the knowledge and learning process and beginning a critical thinking development approach to organizational culture change. Once trauma knowledge has been imparted, everyone in the organization must have a congruent comprehension of what this theory means. This understanding across the entire organization is crucial in creating a healing ecology where every member knows and understands what It means to be trauma-informed, responsive, and driven (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

Shared Language

Shared Language expands knowledge and understanding by embedding common and congruent trauma-informed language across an organization. This language is grounded in three key trauma-responsive questions, which include: What happened? What is happening? What is strong? (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Shared language allows for an even deeper understanding of the impact of adversity and how trauma is reflected in both verbal and nonverbal language. For example, outcomes of a shared, trauma-informed language would include less physical, verbal, and emotional forms of violence and a better ability to articulate goals and create strategies for change (Bloom, Citation2005).

Shared Values

This area of focus is on trauma-informed values and the importance of having a clearly delineated and operationalized set of values that are culturally embedded norms. These norms are practiced by everyone in the organization and are present in all aspects of the work. The TRC Model utilizes the Seven Commitments by Dr. Sandra Bloom (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013b): 1) Commitment to Nonviolence, 2) Commitment to Emotional Intelligence, 3) Commitment to Social Learning, 4) Commitment to Social Responsibility, 5) Commitment to Open Communication, 6) Commitment to Democracy and 7) Commitment to Growth and Change. Norms determine the organizational culture and the culture’s climate as well as strategies, goals, and modes of operations (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

Shared Practice

This building block primarily focuses on building organizational learning structures that embed and lead to embody trauma-informed knowledge, understanding, language, and values. The mission of the TRC Model is to intentionally and purposefully implement all the trauma concepts and tools learned. This multi-level approach pivots around clients, staff serving clients, leaders, and the organization as a whole entity. One of the most fundamental aspects of this block is that it does not have a destination point. Having a shared practice is a journey that aims to practice all the TRC Model trauma-informed building blocks daily (McCorkle, Citation2019).

Shared Culture

Once the above-mentioned TRC Model building blocks are consistently embedded and implemented throughout the organization, the organization’s culture and climate create a healing ecology for all clients, staff, leaders, and the organization itself. In this way, the organization’s ecological system serves as a healing agent for every member of the system through intentional embedded practices and embodied trauma-informed values. At this stage, the organization operationalizes the values and practices that support and encourage the use of the model. Examples of an organizational cultural shift can be found in the organization’s hiring, coaching, supervision, and human resources policies and practices. This also leads to changes in how decisions are made and how organizations hold themselves accountable regarding the TRC Model fidelity. The organizational community utilizes its agreed upon practices, values, and tools, which leads to improved collaboration and conflict management, increased resilience in managing change, improved interactions with peers and clients, and improved organizational culture. In this way, everyone in the organizational system is responsible for the culture. If this shift in power and accountability does not occur, organizations will continue to reenact a negative parent-child dynamic (e.g., authoritarian) between leaders and staff. The TRC Model building blocks were intentionally created to move an organization from knowing about trauma-informed work to embodying trauma-informed work.

Logic Model

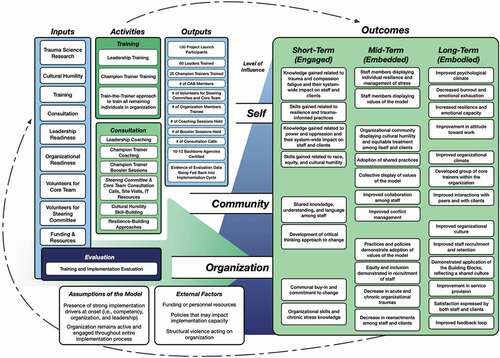

The TRC Model is currently being tested in Louisville, Kentucky, in response to escalating incidents of community violence and racial trauma throughout the city. The following logic model (see, ) illustrates the inputs, activities, and outputs of the TRC Model, as described in earlier sections. Given the aforementioned organizational social context in which organizations function, the logic model also depicts anticipated outcomes across three distinct levels: the Self (i.e., intrapersonal outcomes for individual members of the organization), the Community/We (i.e., interpersonal accomplished outcomes among multiple members or groups within the organization), and the Organization (i.e., global outcomes seen across the agency as a whole). These outcomes are displayed across three primary stages of the TRC Model implementation process: the Engagement stage (i.e., Short-Term Outcomes), the Embedding stage (i.e., Mid-Term Outcomes), and the Embodiment stage (i.e., Long-Term Outcomes).

Outcomes

Given that the initial assumptions are met (i.e., having strong implementation drivers prior to implementation and remaining actively engaged throughout the full implementation process), it is anticipated that an organization, its staff, and ultimately its clients, will experience the following proposed short-term, mid-term, and long-term outcomes across their three levels.

Self level. At the individual level, early engagement with implementation activities assists members of the organization in gaining initial knowledge related to trauma science, resilience, cultural humility, and trauma-informed practice. With the TRC Model becoming embedded into the organizational culture, staff have the opportunity to increase their resilience as training and consultation progress. Early engagement is also a time when staff begin operationalizing the Seven Commitments, including the commitment to nonviolence as well as emotional intelligence, contributing to an increased capacity for managing stress. Once embodied, this culminates in staff experiencing less emotional exhaustion and more positive shifts in their attitude toward work as their psychological climate improves and more positive perceptions of their workplace develop.

Community “we” level. As individuals who embody the model interact within the organization, a new interpersonal dynamic emerges through their newfound critical thinking skills and the shared knowledge, understanding, and language of the TRC Model. The embedding of these shared components becomes evident through increased cultural humility and equity within the organization; evidence of the model’s values (e.g., social learning, resilience toward shifts and changes in the organization); capacity related to collaboration among members; as well as conflict-resolution when unavoidable conflict arises. As the model is embodied, staff begin to have better interactions among each other and with clients, and an improved organizational climate with more positive shared perceptions of the workplace.

Organization level. At the organization level, engagement produces understanding of the causes and impact of chronic stress and organizational skills that are useful in protecting the organization from stress. This creates buy-in among the organization’s members as well as a commitment to changing organizational practices. Once embodied, the model leads the organization to enact trauma-informed values in its practices and policies (e.g., democracy, open communication, and social responsibility) while also demonstrating equity and inclusion throughout the agency, including recruitment and hiring practices. This stage is also marked by a decrease in all forms of organizational trauma (i.e., acute and chronic) as organizational behaviors shift to produce less harm and to respond to inevitable stressors in healthier ways. This shift also contributes to decreased reenactments among staff, contributing to reduced reenactments between clients and staff. An organization that has fully embodied the model will reflect improvements in its overall functioning, including better recruitment and retention of staff, a more positive organizational culture, and a stronger feedback loop to evaluate practice and make needed changes. Ultimately, this leads to improvements in service provision and higher satisfaction among the clients being served.

Other Considerations

It is important to note that while the logic model depicts a linear implementation process – where inputs and activities result in expected outcomes – the process in practice is cyclical in nature. Organizations who embody the model may evaluate their progress over time and identify necessary changes or may encounter new or emergent external factors and realize the need for unexpected shifts in their practice. For example, funding and personnel resources are outside factors that can impact an organization’s capacity for implementation. Shifts in an organization’s access to resources (e.g., funding, personnel) could create a need for significant change across all levels of the organizational structure. Additionally, structural violence (as shown in our theoretical model) is another external factor that constantly acts on an organization, impacting its functioning and evolving needs. It may be common and even expected that organizations will cycle back to the earlier stages of engagement or embedment even after achieving long-term outcomes to address new challenges as ongoing evaluation prompts them to do so.

Implications for Practice

The negative impacts of trauma on individuals are well documented and calls for trauma-responsive interventions. These interventions should focus on preventing future trauma, healing from trauma that has already occurred, and building resilience to fortify the individual. For interventions to be successful and to achieve their desired results, they must move beyond the sole focus of individual interventions and increase efforts to build trauma-responsive and trauma-resilient organizations, which informs important practice implications.

In addition to the client, staff, and organizational outcomes delineated in the logic model, another important practice implication must be considered. If organizational culture change efforts are to be successful, they must respond to structural violence in the systems and communities that our organizations operate within. Without this purposeful interruption, organizations will unknowingly perpetuate structural violence and inequity against those they are trying to serve. Dr. Sandra Bloom (Citation2002) describes a parallel process as when two or more systems are closely connected, they begin to take on characteristics of each other, often becoming “trauma organized” in the way they structure and organize around chronic and prolonged stressors. Building on Galtung’s (Citation1969) definition of structural violence, public systems such as the national child welfare system are rooted in structural violence, which can manifest in racially disproportionate outcomes (Dettlaff & Boyd, Citation2020; Krase, Citation2015). In a similar manner, the organizations that serve the public system may perpetuate similar outcomes. By the same token, the public mental health system that has used violence as a form of control and treatment (e.g., institutionalization, seclusion/restraint, overmedication) has partnerships with organizations that perpetuate these destructive patterns and contribute to institutional violence (Rossiter & Rinaldi, Citation2018). In a more benign example, when systems are in a constant state of change or “reform” and resources are unreliable, organizations closely aligned with that system reflect that chaos and instability, often resulting in competitive and/or siloed organizational cultures (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013a). The TRC model is designed to disrupt the destructive parallel processes between systems of power and the organizations whose purpose is to serve vulnerable individuals.

Conclusion

Elements of structural violence such as racism, classism, gender bias, and homophobia are often silently and cyclically continued within helping organizations because of the parallel processes identified above. Without deliberate organizational interventions, structural violence can and will be perpetuated. Similarly, organizations do not deliberately organize around crisis and chaos, nor do they intentionally devalue their workers by focusing on productivity and profit over safety, healing, and self-care. Still, they often fall into destructive parallel processes when intentional structures are not in place. Leadership is one of the most crucial factors in building a trauma-responsive and trauma-resilient culture, but it takes an entire organization’s commitment to make this change sustainable. The TRC Model is a framework or blueprint for change, and it is the organization’s job to take on the change work. We know that trauma is contagious, not only from individual to individual but from system to system. By seeking to address systemic and structural violence, the TRC Model is built upon a theoretical framework that combines the current science regarding how to prevent and heal from trauma with the evidence-based organizational development science to implement sustainable culture change.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychological Association. (2016). Trauma. APA. http://www.apa.org/topics/trauma/

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

- Bednar, S. G. (2003). Elements of satisfying organizational climates in child welfare agencies. Families in Society, 84(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.70

- Better, S. (2002). Institutional racism: A primer on theory and strategies for social change. Burnham.

- Bloom, S. (2002, October 29). Organizational stress as a barrier to trauma-informed service delivery. Connecting Paradigms. https://connectingparadigms.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/21360-Organizational_Stress_as_a_Barrier_to_Trauma-Informed-Bloom.pdf

- Bloom, S. L. (2005). The sanctuary model of organizational change for children’s residential treatment. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations, 26(1), 65–81.

- Bloom, S. L., & Farragher, B. J. (2013a). Destroying sanctuary: The crisis in human service delivery systems. Oxford University Press.

- Bloom, S. L., & Farragher, B. (2013b). Restoring sanctuary: A new operating system for trauma-informed systems of care. Oxford University Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 145(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.145.1.1

- Brock, K. J., Pearlman, L. A., & Varra, E. M. (2006). Child maltreatment, self capacities, and trauma symptoms: Psychometric properties of the Inner experience questionnaire. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v06n01_06

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory (R. Vasta, Ed.). Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (p. 187–249). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3). Elsevier. Reprinted in: Gauvain, M. & Cole, M. (Eds.), Readings on the development of children, 2nd Ed. (1993, pp. 37-43). NY: Freeman.

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction (1st ed. ed.). New York University Press.

- DePanfilis, D., & Zlotnik, J. L. (2008). Retention of front-line staff in child welfare: A systematic review of research. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(9), 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.017

- Dettlaff, A. J., & Boyd, R. (2020). Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system: Why do they exist, and what can be done to address them? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692(1), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220980329

- Dhaliwal, K. (2016, October 24). Racing ACEs gathering and reflection: If it’s not racially just, it’s not trauma-informed. ACEs Too High. https://acestoohigh.com/2016/10/24/racing-aces-gathering-and-reflection-if-its-not-racially-just-its-not-trauma-informed/

- Feagin, J. R. (2010). Racist America: Roots, current realities, and future reparations (2nd ed. ed.). Routledge.

- Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. The National Implementation Research Network.

- Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

- Glisson, C. (2000). Organizational culture and climate. In R. Patti (Ed.), The handbook of social welfare management (pp. 195–218). Sage.

- Glisson, C. (2002). The organizational context of children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(4), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020972906177

- Glisson, C. (2007). Assessing and changing organizational culture and climate for effective services. Research on Social Work Practice, 17(6), 736–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507301659

- Glisson, C., Dukes, D., & Green, P. (2006). The effects of the ARC organizational intervention on caseworker turnover, climate, and culture in children’s service systems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(8), 855–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.010

- Glisson, C., & Green, P. (2006). The effects of organizational culture and climate on the access to mental health care in child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-005-0016-0

- Glisson, C., & Hemmelgarn, A. L. (1998). The effects of organizational climate and interorganizational coordination on the quality and outcomes of children’s service systems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(5), 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00005-2

- Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2002). The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 767–794. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.162

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (Eds.). (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. New directions for mental health services. Jossey-Bass.

- Hemmelgarn, A. L., Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2006). Organizational culture and climate: Implications for services and interventions research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00008.x

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 10(4), 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300

- Hummer, V. L., Dollard, N., Robst, J., & Armstrong, M. I. (2010). Innovations in implementation of trauma-informed care practices in youth residential treatment: A curriculum for organizational change. Child Welfare, 89(2), 79–95. PMID: 20857881.

- Krase, K. S. (2015). Child maltreatment reporting by educational personnel: Implications for racial disproportionality in the child welfare system. Children & Schools, 37(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv005

- LeBel, J., Stromberg, N., Duckworth, K., Kerzner, J., Goldstein, R., Weeks, M., Harper, G., & Sudders, M. (2004). Child and adolescent inpatient restraint reduction: A state initiative to promote strength-based care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200401000-00013

- Loomis, B., Epstein, K., Dauria, E. F., & Dolce, L. (2019). Implementing a trauma-informed public health system in San Francisco, California. Health Education & Behavior, 46(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118806942

- McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Constructivist self-development theory as a framework for assessing and treating victims of family violence. In S. M. Stith, M. B. Williams, & K. H. Rosen (Eds.), Violence hits home: Comprehensive treatment approaches to domestic violence (pp. 305–329). Springer Publishing Co.

- McCorkle, D. (2019). Train the trainer manual (2019). Center for Trauma Resilient Communities.

- Middleton, J. S. (2011). The relationship between vicarious traumatization and job retention among child welfare professionals (Doctoral dissertation, University of Denver).

- Middleton, J. S., Bloom, S. L., Strolin-Goltzman, J., & Caringi, J. (2019). Trauma-informed care and the public child welfare system: The challenges of shifting paradigms: Introduction to the special issue on trauma-informed care. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2019.1603602

- Middleton, J., Harris, L. M., Matera Bassett, D., & Nicotera, N. (2022). Your soul feels a little bruised”: Forensic interviewers’ experiences of vicarious trauma. Traumatology, 28(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000297

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2015). Culture and trauma. https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/culture-and-trauma

- Ogbu, J. U. (1990). Understanding diversity: Summary comments. Education and Urban Society, 22(4), 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124590022004009

- Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Treating therapists with vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress disorders. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized, (pp. 150–177). Brunner/Mazel.

- Peterson, N. A., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1–2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040151.77047.58

- Rivard, J. C., Bloom, S. L., McCorkle, D., & Abramovitz, R. (2005). Preliminary results of a study examining the implementation and effects of a trauma recovery framework for youths in residential treatment. Therapeutic Community: The International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations, 26(1), 83–96.

- Rossiter, K., & Rinaldi, J. (2018). Institutional violence and disability: Punishing conditions. Routledge.

- Saakvitne, K. W., Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (2010). Exploring thriving in the context of clinical trauma theory: Constructivist self development theory. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01219.x

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. substance abuse and mental health services administration. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Verbeke, W., Volgering, M., & Hessels, M. (1998). Exploring the conceptual expansion within the field of organizational behavior: Organizational climate and organizational culture. Journal of Management Studies, 35(3), 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00095

- Watts, R. J., & Carter, R. T. (1991). Psychological aspects of racism in organizations. Group and Organizational Studies, 16(3), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960119101600307

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43–63). Plenum Press.