ABSTRACT

Low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) bear a high burden of intimate partner violence (IPV). However, there are no reviews assimilating the factors affecting risk of IPV in LMICs. This systematic review (2010–20) identifies risk and protective factors of IPV in LMICs. We followed the PRISMA guidelines to review 399 studies and included 32 studies. Studies were of ever-partnered women living in an LMIC, aged 15 years and above, who had ever faced IPV from a male partner. Disaggregating factors using the ecological framework, we found that women less than 45 years of age face increased risk of IPV. Secondary and higher education levels of men lower the risk. Both employment and unemployment of women increase the risk. Male partner’s dependence on alcohol or substances increases the risk. Prior exposure to abuse of either partner increases risk of IPV. Similarly, justification of wife-beating by any partner increases risk. Intimate relations which are more gender-equal experience lowered risk. Women who have no children, stay in smaller-sized families and reside in rural areas, face lower risks. The review found that risk factors outnumber protective factors. Protective factors are much more context-dependent, while risk factors are more universalizable for the LMIC world.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is behavior within an intimate relationship that causes emotional, physical, psychological, sexual, or economic harm, and involves acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, and psychological abuse (World Health Organization, Citation2009). It affects one in three women worldwide (World Health Organization, Citation2021) and has harmful consequences for a woman’s physiological, psychological, reproductive, and mental health. Some of these health consequences are intergenerational, impacting the quality of lives of the children who grow up in abusive households (Ahmed et al., Citation2006). The burden of IPV varies across settings and prevalence can be up to five times higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) compared to high-income countries. In a multicountry study Ethiopia reported 71% IPV compared to 15% in Japan (Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2005). Despite this high prevalence in LMICs, data on risk and protective factors for IPV from LMICs is sparse.

Sociological theories help us analyze factors associated with IPV. The World Health Organization (WHO) uses an ecological framework to study factors for IPV along four levels, namely, individual, relationship, community, and societal levels. Individual-level factors include biological and personal histories, such as age, education, and employment among others. Relationship-level factors include interpersonal experiences, including experience of violence as a child. Community-level factors include factors such as socioeconomic status of the couple. In 2010, the WHO reported on the absence of research, particularly of longitudinal studies, on risk factors for IPV in the LMICs (World Health Organization, Citation2010). This lack proves to be a challenge in developing a contextual understanding of factors that increase risk of IPV in LMICs, and factors that can mitigate it. To address this gap, the present review synthesizes risk and protective factors for IPV in LMICs, between 2010 (when WHO published the report) and 2020.

Method

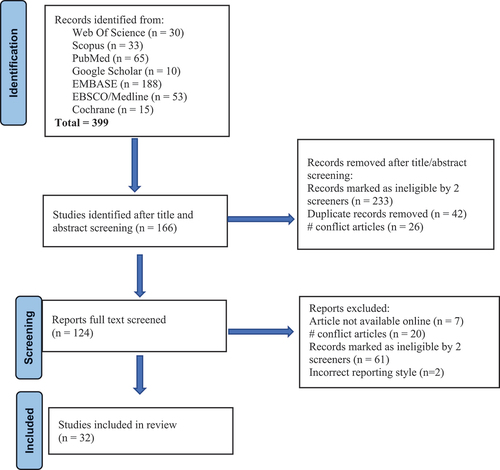

We conducted a systematic review of literature using eight databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. Keywords included variations of the term IPV, marital, spousal, or family abuse, rape, or violence, risk and protective factors, and low- and middle-income countries. We followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021247915). We included quantitative, mixed methods and systematic review studies published in English, in academic journals, between January 2010 and December 2020. Risk and protective factors were defined as any condition associated with increasing/decreasing at least one type of IPV. Perpetrator-focused studies which sampled men who perpetrated violence were also included to understand risk and/or protective factors of IPV against women. Full eligibility criteria are listed in .

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Eligibility Criteria.

Selection process

Initial searches produced 399 articles. None of the primary studies in our review were included in any other systematic review. Articles were screened by RG and ACD; DS was approached for conflict resolution. To further minimize selection bias, weekly meetings under the supervision of NR were held to validate reasons for inclusion. After removing duplicates, and screening titles and abstracts, we had 124 eligible articles. Three of the coauthors with help from a colleague formed two teams and read these texts in full to assess their eligibility and reach agreement on inclusion. Twelve authors were contacted to provide full-text articles; seven did not respond. After reading the full texts, 32 articles were included for the final review ().

Data extraction and quality analysis

Data on the country of study, sample size, population characteristics, study methodology, and odds ratios with confidence intervals for any significant risk and protective factors were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet. Unadjusted odds ratio was considered only when adjusted odds ratio was not available. Four studies reported a total of 58 statistically significant odds ratios but did not report their confidence intervals. The odds ratios were included as the researchers believe that the possible insight gained from these studies is superior to any quality loss. Quality of each article was assessed using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tools (Study Quality Assessment Tools NIH). Studies were rated as ‘Good’ (fulfilled >70% of the NIH assessment tool), ‘Fair’ (50 to 70% adherence) or ‘Poor’ (<50% criteria fulfilled).

Data analysis

Data such as age, education, or number of children were merged under thematic categories. For instance, under the risk factor ‘Man drinks alcohol,’ all descriptions of ‘man drinks occasionally,’ ‘man drink often,’ ‘man drinks monthly,’ ‘man drinks daily,’ ‘man drinks any alcohol,’ were combined. The combined factors were categorized under the corresponding level of the ecological model of IPV (individual or relationship or household or community) and narratively summarized.

Results

Forty countries from four continents were represented in the final 32 studies; five studies included more than one country Most studies included only female participants (n = 27); three included only men, and four included both men and women. Twenty studies did mention any eligibility requirements regarding participant’s relationship status. Of the remaining, eight accepted only married participants, two ever-married, two ever-partnered, one ever-married or cohabitating and one both married and un-married participants. Nine studies reported only risk factors and no protective factors.

Using the ecological framework, we present the risk and protective factors under four levels: individual, relational, household, and community. Societal-level factors were not presented in any of the articles, and thus are not analyzed in this present systematic review. All Confidence Intervals (CIs) reported are 95%.

Individual level factors

Individual-level factors were age, education, employment, alcohol, or substance consumption, and past exposure to violence and abuse of both women (as victims) and men (as abusers)

Overall, younger women were at higher risk of abuse than older women. However, results were dependent on context, as both increased and decreased odds of abuse were observed in different countries. At multiple ages below 35 years, women had higher odds of abuse in Sri Lanka (3.0, 1.5–13.9; Jayasuriya et al., Citation2011), in India (1.57, 1.33; Mahapatro et al., Citation2012), and in rural Bangladesh (7.69, 1.20–49.41; Islam, Citation2020). In Palestine, women aged 25 to 34 were at higher risk of moderate (1.46, 1.12–1.91) and severe (1.92, 1.24–2.99) psychological IPV (Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013).

Odds of abuse were higher for younger women in India, Rwanda, and Nigeria. In India, women aged 21 to 25 years (1.48, 1.25–1.74), aged 26 to 30 (1.57, 1.33–1.85) and 31 to 35 years (1.42, 1.2–1.68) had greater odds of abuse, compared to women under 20 years (Mahapatro et al., Citation2012). For women aged 45 years and older, odds of abuse declined across all countries.

Older men were less likely to perpetrate IPV in Vietnam (older than 30; Jansen et al., Citation2016) and Palestine (over 35; Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013). In all other countries, men over 29 were consistently more likely to perpetrate IPV than younger men.

Women were at increased risk irrespective of their educational levels. The male partner’s level of education was a protective factor in some cases. Odds of abuse increased for women whose partners had incomplete or no formal education in Pakistan (1.87, 1.31–2.67; Ali et al., Citation2011) and in Rwanda (1.94, 1.14–2.72; Umubyeyi et al., Citation2014) compared to men who had completed some level of formal education. Men who had attained a secondary education or higher were least likely to perpetrate IPV except for rural Indonesia (2.07, 1.36–3.17; Hayati et al., Citation2011).

Employment of both men and women did not show any consistent association with IPV. Five studies showed increased risk employed women, while four showed increased risk for unemployed women. A study from India found reduced IPV among unemployed women (0.73, 0.67–0.81; Mahapatro et al., Citation2012). However, being economically dependent on their husband increased odds of psychological IPV (2.97, 1.33–6.61) among women in Kathmandu, Nepal (Dhungel et al., Citation2017). In rural Bangladesh, women who were economically independent of their husbands faced reduced sexual IPV (0.06, 0.02–0.22; Islam, Citation2020); but in rural Indonesia, economically independent women faced more sexual IPV (1.65, 1.08–2.52; Hayati et al., Citation2011).

Women’s and men’s past experience of/exposure to violence consistently increased the odds of abuse in the present. Thirteen studies showed that women who had experienced violence in childhood had higher odds of experiencing physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in adult life, with odds ranging from 1.46 in peri-urban Ghana (1.07–1.99; Ogum Alangea et al., Citation2018) to odds of 3.15 in Nepal (1.41–7.05; Yoshikawa et al., Citation2014). Likewise, women who had witnessed their mothers being abused by their fathers were at higher risk of abuse themselves.

Consumption of alcohol/substances by the male partner consistently increased risk of IPV. In Vietnam odds increased from 2.97 (1.48–5.98) for men who drank monthly, to 3.32 (1.59–6.94) for those who drank weekly, up to 7.06 (3.39–14.69) for those who drank daily (Jansen et al., Citation2016). Odds also increased when the woman drank, especially prior to having sex (1.21, 1.0–1.32; Kouyoumdjian et al., Citation2013).

Relationship level factors

Relationship-level factors that increased IPV included justification of violence against women by either partner, marital status, ages at exposure to sexual experiences, suspicions of infidelity, and level of gender inequity in the relationship. Across twelve studies, women whose partners justified IPV faced up to three time higher odds of abuse (2.0–4.95; Fleming et al., Citation2015). Similar results were observed for women who justified wife beating (Cofie, Citation2020; Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013). However, according to one study in rural Indonesia women who agreed with the statement that ‘the woman is obliged to have sex with her husband’ and disagreed with the statement that ‘people from outside the family should intervene during an episode of violence’ had lower odds of being physically abused (0.48, 0.29–0.8 and 0.58, 0.34–0.99 respectively; Hayati et al., Citation2011).

Women who were married had higher odds of abuse than those who were in an intimate relationship but not married. Among married women in India, abuse was more likely to be present among those who had an arranged marriage compared to those who had a love marriage (2.19, 1.86–2.57; Mahapatro et al., Citation2012).

Gender equitable relationships with shared or equal decision-making lowered odds of abuse. Comparatively, low decision-making power or gender inequity resulted in greater odds of violence in parts of Asia and Pacific countries (1.77, 1.5–2.6; Jewkes et al., Citation2017).

Household level factors

Household-level factors showed that smaller sized families were protective against abuse. Compared to women with no children, those with more children had higher risks. Five studies representing Tanzania, Rwanda, and Democratic Republic of the Congo showed that having at least one child increased risk (Rurangirwa et al., Citation2017; Tiruneh et al., Citation2018; Umubyeyi et al., Citation2014). Studies in India, Palestine and urban Pakistan families showed that compared to women living in households with four or fewer members, those living in households with five or more members had increased likelihood of abuse, with odds from 1.49 (1.03–2.15) to 1.54 (1.36–1.74; Ali et al., Citation2011; Mahapatro et al., Citation2012).

Community level factors

At the community level, it was found that women living in rural areas had reduced risks compared to those in urban areas. Living in rural Tajikistan and Palestine reduced risk of severe IPV by up to 56% (0.24–0.79) while living in urban Rwanda and Tajikistan increased risks by up to 94% (1.33–2.81).

Lack of social support from neighbors/community was a significant risk factor in Rwanda, Vietnam, and Ghana. In Palestinian territories, women receiving help from their neighborhood had less chance of suffering psychological IPV (0.85, 0.76–0.98; Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013). However, in Ghana, receiving support from significant others in the community increased risk by 8.249 (p < .001) (odds ratios not reported in this study) compared to women who did not receive any community support (Cofie, Citation2020).

In Maputo, Mozambique, school-going women aged 15–24 who lacked religious commitment had increased odds (1.01–2.53; Maguele et al., Citation2020). Being a Protestant was associated with 1.48 greater odds for women (no CI) compared to Catholics in Ghana (Cofie, Citation2020). A study in India found that Catholic (0.55, 0.42–0.71) and Buddhist women (0.26, 0.20–0.36) had lower risks of violence than Hindu women (Mahapatro et al., Citation2012).

Discussion

The systematic review captures diversity of factors at four ecological levels. It shows that neither education nor employment of women are consistently protective against IPV. Common risk factors include younger age of woman, larger sized families, normative acceptance of abuse, absence of social support, and past experiences of/exposure to violence. Higher levels of education of the male partner, older age of the woman, smaller families, residing in rural settings and the presence of social support are usually protective against IPV.

Neither women’s education nor their employment is a consistent protective factor despite these being tools of empowerment. We invoke the male backlash hypothesis to understand this. Most societies are patriarchal and find it disruptive when women break the power status quo to move into traditionally male spaces, including into higher education or taking up employment. Such moves threaten male dominance and backlash follows in the form of violence against women in both public and family spaces (Lolayekar et al., Citation2020). Some scholars point out that such subversions are transitory and shall stabilize over time, when the changes become the norm (Simister & Mehta, Citation2010). But since the studies analyzed in this review are cross-sectional, we remain unable to assess if IPV actually decreased over time.

Along with employment, unemployment too is a risk factor, and the latter is easier to understand. Married women who are unemployed would most likely be dependent on their husbands/in-laws for financial support. Their limited/no financial autonomy would make them vulnerable to abuse. A study using demographic health survey data from 19 LMICs (Zafar et al., Citation2021) disaggregated IPV into severe physical violence, less-severe physical violence, sexual violence, and emotional violence, and studied the association of employment with each type. They found that the risk of less-severe physical IPV and of emotional IPV increased for employed women, while risk of sexual IPV reduced. It is likely that employed women trigger insecurity among the male partners and are accused of neglecting family duties. Such accusations constitute emotional IPV. At the same time, reduced contact time with the male partner (since the woman is leaving the house to pursue her employment) would decrease the risk of sexual IPV.

Age is a protective factor with older women less at risk of IPV (Ismayilova & El-Bassel, Citation2013; Kimuna & Djamba, Citation2008; Yüksel-Kaptanoǧlu et al., Citation2012). This is likely because compared to women who are older and married for a longer time, younger women are fewer years into the relationship/marriage and thereby are less stabilized within the household. Younger women have less power within the family and are thus more vulnerable (Devries et al., Citation2010; Johnson et al., Citation2015). Additionally, we argue that younger women deal with pressures of family planning, pregnancies, motherhood, and economic and job-related uncertainties, all of which add to her vulnerability. These pressures decrease as the woman grows older and significantly reduces by the time she crosses 45 years of age. By this time other younger women have entered the family and power equations have shifted. It is not unlikely that the older women would themselves become abusers of the younger ones, repeating the intergenerational cycle of violence. Also, older women tend to get more respect in traditional societies, and that could also be a reason for the reduced violence. Further, as the woman ages, the abusive male partner/spouse also ages, and could be affected by failing health or morbidity (Gerino et al., Citation2018).

Some evidence suggests that in certain contexts social support is more available for elderly women than for younger ones (Gerino et al., Citation2018). A final explanation for why IPV is lower in older age groups is women who have tolerated abuse over a few decades, are very likely to normalize it as part of life – this acceptance would reduce disclosure/reporting. Literature shows that in certain types of IPV are reduced elderly women though abuse per se is not eliminated (Meyer et al., Citation2020). Sexual and physical violence are more likely to be reduced for elderly women compared to emotional abuse, which could stay the same or even increase (Warmling et al., Citation2017). However, for someone who has been facing abuse over several years, a reduction in two types of IPV can be relieving.

Alcohol and substance dependence increase risk of abuse (Abbey et al., Citation1998; Barrett et al., Citation2012; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Thompson & Kingree, Citation2004). Substance dependence affects cognition and physical functioning. Substance abusers cope poorly with frustration and anger, and vent out with aggression on the less powerful, such as the wife/spouse and children (Field et al., Citation2004; Flanzer, Citation2005; Wang et al., Citation2017). Individuals who have witnessed abuse in childhood, such as the abuse of their mother, have a higher likelihood of perpetrating or suffering IPV as an adult (Abramsky et al., Citation2011; Islam et al., Citation2015; Lünnemann et al., Citation2019; Monnat & Chandler, Citation2015). This happens because violence is a ‘socially learned behaviour’ (Bandura, Citation1978), and people tend to reproduce behaviors they witness as children (Fonseka et al., Citation2015). Justification of wife-beating by any of the partners is a risk factor. In a patriarchal system, men who justify wife-beating perceive their female partners as possessions to be controlled and abused at will (Antai, Citation2011; Mandal & Hindin, Citation2013).

Women who justify wife-beating are more accepting of their own abuse and tend to hold themselves responsible for the situation. They are less likely to seek support from their social network, or report it to the authorities (Cofie, Citation2020; Flood & Pease, Citation2009; Walker, Citation2006). The cycle of violence thus continues, and women enter a state of ‘learned helplessness’ (Swanson & Dougall, Citation2017). Learned helplessness indicates a situation wherein the woman believes that there is little she can do to alter her circumstances since violence is a normal part of life. This acceptance of occurrence of abuse eliminates any helpseeking behavior at her end. This systematic review highlights one exception where women who justified IPV faced lower risks of IPV (Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013). This is very likely an outlier, and we use the theory of ‘benevolent sexism’ to understand this. According to this theory, when women subscribe to traditional gender roles and accept that they can be abused, and stop questioning or resisting the abuse, they are occasionally ‘rewarded’ by the abusers by reduced violence (Allen et al., Citation2009).

Suspicions of infidelity increase risk of IPV. Men who have relationships outside of marriage tend to view such polyamory as an extension of their masculine identities: “Discourses of male sexuality (as active) provide a context in which having multiple sexual partners and resultant marital infidelity is accepted and sometimes tolerated that emphasize sexual conquests and male-dominance” (Boonzaier, Citation2005, p. 102). A cross-sectional study from Nepal (Shrestha et al., Citation2016) showed that 11% of the sampled (pregnant) women said that male infidelity was the reason they faced abuse. When a woman suspects her partner of infidelity and confronts him, he sees it as questioning his male privileges. He resorts to violence in order to maintain the gender status quo (Conroy, Citation2014). A study from Uganda (Karamagi et al., Citation2006) found that women whose husbands had other sexual partners faced more IPV “because of unequal love, jealousy and neglect” (p. 7).

In cases where the male partner suspects/accuses the woman of infidelity, the likelihood that she shall face IPV is high (Kim & Motsei, Citation2002). Women are considered as property to be possessed, or a conduit to material property in many patriarchal cultures (Dandona et al., Citation2022). Male ownership of the woman translates to her expected emotional and physical loyalty to the partner. If she is suspected of intimacy with another male, her partner’s insecurities are triggered, leading to violence against her (Shrestha et al., Citation2016). However, compared to men who have extramarital relations, women who have extramarital relations face additional stigma and discrimination in society, increasing their overall exposure to abuse (Pichon et al., Citation2020).

Marriage is a risk factor for women (Conroy, Citation2014; Zablotska et al., Citation2009). This is likely because marriage as an institution is patriarchal and is premised on the ‘exchange of women.’ Anthropologist Levi-Strauss in his Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) theorized that the basis of modern institution of marriage is the exchange of women between men/families for the core purpose of propagating the species. Rubin (Citation1975) unpacks how marriage renders women into commodities for exchange with predetermined purposes, namely, to reproduce for the family that she belongs to after the ‘exchange.’ Aggravating the potential for violence within marriages is dowry, a custom prevalent in many South Asian and African countries whereby, the woman also becomes the source for obtaining material wealth from her natal family (Naved & Persson, Citation2010; Srinivasan & Bedi, Citation2007). When the amount or quality of wealth obtained through her (on the occasion of the marriage) is considered not adequate or satisfactory enough, violence ensues. India records one of the highest burdens of dowry deaths globally. According to national police statistics, 19 women were killed per day in India in 2020 by their in-laws over dowry demands (Chaudhary, Citation2022).

Intimate relations built on gender equality are protective against IPV. Gender equality implies that women are considered at par with men in policies, laws, and society, besides ensuring equality in terms of access to resources and services within families and communities (World Health Organization, Citation2009). Women in such relationships enjoy more decision-making power which is an indicator for empowerment (Zegenhagen et al., Citation2019).

Smaller sized families are more protective against IPV, and having no children is a protective factor. This may be so since married women with no children are more likely to be in the initial years of marriage/cohabitation, which is more likely to be a phase where the violence has not yet initiated. But this explanation contradicts the above discussion where we saw younger women (who are more likely in the initial stages of the relationship) face higher odds of IPV compared to older women. So, another explanation for the woman with no children facing lower violence could be that smaller families face less economical constraints compared to larger families. Less economical constraints imply lower stress among family members. Haj-Yahia and Clark (Citation2013) suggest that larger family sizes go hand in hand with women’s “loss of control over their body […] and fertility” (Haj-Yahia & Clark, Citation2013, p. 806). This can be supported by results found on use of contraceptives. Women whose partners refused to use contraceptives, showed higher odds of being abused (Stöckl et al., Citation2010). However, in this case, larger families would be a consequence of IPV due to men’s controlling behavior over women’s body, and not a cause. Moreover, women may have to stop working once they have children to take care of them, thus lowering their individual incomes and hence lowering their bargaining power, and thus increasing their risks of being abused.

Poor social support increases the risks, and by extension, good social support decreases risk. These results are consistent with literature. Cofie (Citation2020) found that receiving social support from close friends and family increased the odds of IPV. This could be likely when support sought/received from the woman’s natal family is perceived as a threat by the abuser or as questioning his authority. Such perceptions could increase violence. Specific religions appear to affect odds of IPV. It is possible that in some of the studies religion is a confounder. For instance, a Protestant in Ghana or a Muslim in India can be more at risk of IPV because they belong to the minority religious community, rather than for their religion per se. As a minority they are more likely to suffer from stigma, have less educational and economic opportunities and therefore be more prone to all forms of violence including IPV (First et al., Citation2017). Women with no religious commitment were seen to be at increased risk. Many religions promote unquestioning respect and obedience of the husband and submission by the wife (Maguele et al., Citation2020). Women who disregard religious dictates tend to be more questioning of patriarchal norms, and by extension, are less tolerant of abuse. They would disclose IPV more readily. The association between living in a politically violent setting and increased IPV is consistent with literature. Politically violent contexts such as a civil war, increase stress and anxiety in people and lead to abuse of power within intimate relationships (Usta et al., Citation2008). The general IPV characteristics of a community reflect on individual women (Tiruneh et al., Citation2018), showing the organic interconnections between individual and community-level factors. This review had the counterintuitive finding that IPV risks are lower for those living in rural settings. Most studies have argued the opposite, namely that women in rural areas are more at risk since such societies are more traditional and oppressive for women with little or no community support for abused women (Brownridge et al., Citation2008; Lawoko et al., Citation2007). A few studies though show that cities have more IPV than rural areas. They explain that employment difficulties are more in cities than in rural areas, and this leads to more frustration and aggression for city dwellers. Rural areas are agriculture based with lower levels of financial uncertainty and thus have lower IPV compared to urban. Also, rural communities have stronger social networks as compared to urban communities (VanderEnde et al., Citation2015). Some argue that rural women are more likely to justify IPV leading to reduced disclosure (Reese et al., Citation2021). However, most studies included in this systematic review were based either in rural or in urban areas and did not offer a comparison between the two settings.

Limitations

This review did not unpack the types of IPV (physical, sexual, emotional) against each risk or protective factor. Studying the effect of each factor against specific IPV types can help design interventions with clearer objectives. Further, very few studies analyzed any community-level risk or protective factor. More research on factors at this level could greatly contribute to a better understanding of the interplay between levels. IPV affects individuals of all genders and same-sex relationships. However, this review only included studies of heteronormative partners where the survivor was the biological female, and the abuser the biological male. The authors acknowledge their limitations of gender diversity. The review excludes studies (since we did not use the required search keywords) on minority groups such as transgender women, refugees, or immigrants. The results of the review thereby remain only partially applicable to these subgroups. The selection bias is acknowledged since only publications in English and in peer-reviewed journals were considered. While only 14 included articles were assessed to be of “good” quality (NIH assessment tool), we also included studies which scored ‘Poor’ in order to account for diversity. Further, all the studies in this review are cross-sectional, and so we are unable to provide insights into the longitudinal effects of any exposure. To address this gap, we encourage future research to use cohort or longitudinal study designs to increase the reliability of the likely causal links.

Conclusion

The findings of this systematic review delineate the factors that associate with IPV against women in the ecological framework and for women residing in the LMICs. We note that risk factors are more definitive to identify, but protective factors are rarely consistent across context. Definitive risk factors include low education levels of men and women, alcohol and substance dependence, prior exposure to violence, acceptance of abuse as normal, poor social support network and living in politically volatile contexts. Some risk factors are also contradictory such as employment: both employed women and unemployed women are at increased risk. Some of the definitive protective factors include older age of women, smaller sized families, living in rural geographies. Risk factors vastly outnumber protective factors. This implies that as researchers we are yet unable to specifically pinpoint exposures which can reduce IPV. We use this conclusion to emphasize the urgency to design studies enquiring only into factors that protect women against IPV. Unless protective factors are actively identified, we cannot design effective interventions to reduce the burden of IPV. Further, certain ecological-level factors are more conducive to intervention. Interventions to reduce risk factors and promote protective ones need to address the ecological levels accordingly.

Author note

Rakhi Ghoshal, CARE India, Patna, Bihar; Anne-Charlotte Douard, Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Shegufta Shefa Sikder, CARE USA; Atlanta, USA; Nobhojit Roy, The George Institute for Global Health – India; Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Dell Saulnier, Department of Clinical Sciences Malmö, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden; Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Rakhi Ghoshal is now at CARE, Delhi, India; Anne-Charlotte Douard is now at Medicine Foundation; Amsterdam, Netherland; Nobhojit Roy is also at The George Institute for Global Health – India.

Acknowledgments

We express our most sincere gratitude to Dr. Taylor Jones who provided her valuable time to support us with search of full texts, assess for eligibility, participate in consensus meetings, and assess for quality using the NIH tool. We are also extremely grateful to Prof (Dr) Anita N. Gadgil for her incisive comments and enriching inputs to the manuscript. Finally, we express heartfelt thanks to our peers who were present at the weekly meets and helped with periodic inputs, suggestions, and multiple brainstorming sessions. We specifically name Ms. Ramona Stoßberger for her sustained engagement of this paper over many months.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbey, A., McAuslan, P., & Ross, L. T. (1998). Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(2), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1998.17.2.167

- Abramsky, T., Watts, C. H., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A., & Heise, L. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-109

- Ahmed, S., Koenig, M. A., & Stephenson, R. (2006). Effects of domestic violence on perinatal and early childhood mortality: Evidence from North India. American Journal of Public Health, 96(8), 1423–1428. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066316

- Ali, T. S., Asad, N., Mogren, I., & Krantz, G. (2011). Intimate partner violence in urban Pakistan: Prevalence, frequency, and risk factors. International Journal of Women’s Health, 3(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S17016

- Allen, C. T., Swan, S. C., & Raghavan, C. (2009). Gender symmetry, sexism, and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(11), 1816–1834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508325496

- Antai, D. (2011). Controlling behavior, power relations within intimate relationships and intimate partner physical and sexual violence against women in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 511. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-511

- Bandura, A. (1978). Social Learning Theory of Aggression. Journal of Communication, 28(3), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x

- Barrett, B. J., Habibov, N., & Chernyak, E. (2012). Factors affecting prevalence and extent of intimate partner violence in Ukraine: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Violence Against Women, 18(10), 1147–1176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212464387

- Boonzaier, F. (2005). Woman abuse in South Africa: A brief contextual analysis. Feminism & Psychology, 15(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353505049711

- Brownridge, D., Ristock, J., & Hiebert-Murphy, D. (2008). The high risk for IPV against Canadian women with disabilities. Medical Science Monitor, 14, 27–32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18443559/

- Chaudhary, S. (2022). Dowry and dowry death. The Times of India. April 15. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/politiclaw/dowry-and-dowry-death-42574/

- Cofie, N. (2020). A multilevel analysis of contextual risk factors for intimate partner violence in Ghana. International Review of Victimology, 26(1), 50–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758018799030

- Conroy, A. A. (2014). Gender, power, and intimate partner violence: A study on couples from rural Malawi. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(5), 866–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505907

- Dandona, R., Gupta, A., George, S., Kishan, S., & Kumar, G. A. (2022). Domestic violence in Indian women: Lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance. BMC Women’s Health, 22(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

- Devries, K. M., Kishor, S., Johnson, H., Stöckl, H., Bacchus, L. J., Garcia-Moreno, C., & Watts, C. (2010). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reproductive Health Matters, 18(36), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36533-5

- Dhungel, S., Dhungel, P., Dhital, S. R., & Stock, C. (2017). Is economic dependence on the husband a risk factor for intimate partner violence against female factory workers in Nepal? BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0441-8

- Field, C., Caetano, R., & Nelson, S. (2004). Alcohol and violence related cognitive risk factors associated with the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 19(4), 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOFV.0000032635.42145.66

- First, J. M., First, N. L., & Houston, J. B. (2017). Intimate partner violence and disasters: A framework for empowering women experiencing violence in disaster settings. Affilia, 32(3), 390–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109917706338

- Flanzer, J. P. (2005). Alcohol and other drugs are key causal agents of violence. 163–174. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328584.n10

- Fleming, P. J., McCleary-Sills, J., Morton, M., Levtov, R., Heilman, B., Barker, G., & Dalal, K. (2015). risk factors for men’s lifetime perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners: Results from the international men and gender equality survey (IMAGES) in eight countries. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0118639–e0118639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118639

- Flood, M., & Pease, B. (2009). Factors influencing attitudes to violence against women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334131

- Fonseka, R. W., Minnis, A. M., Gomez, A. M., & Dalal, K. (2015). Impact of adverse childhood experiences on intimate partner violence perpetration among Sri Lankan men. PloS One, 10(8), e0136321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136321

- Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Report on the first results. World Health Organization, 55–89. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924159358X

- Gerino, E., Caldarera, A. M., Curti, L., Brustia, P., & Rollè, L. (2018). Intimate partner violence in the golden age: Systematic review of risk and protective factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01595

- Haj-Yahia, M. M., & Clark, C. J. (2013). Intimate partner violence in the occupied palestinian territory: Prevalence and risk factors. Journal of Family Violence, 28(8), 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9549-2

- Hayati, E. N., Högberg, U., Hakimi, M., Ellsberg, M. C., & Emmelin, M. (2011). Behind the silence of harmony: Risk factors for physical and sexual violence among women in rural Indonesia. BMC Women’s Health, 11(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-11-52

- Islam, M. S. (2020). Intimate partner sexual violence against women in Sylhet, Bangladesh: Some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002193202000067X

- Islam, T. M., Md I, T., Sugawa, M., & Kawahara, K. (2015). Correlates of intimate partner violence against women in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Violence, 30(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9683-0

- Ismayilova, L., & El-Bassel, N. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence by type and severity: population-based studies in Azerbaijan, Moldova, and Ukraine. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513479026

- Jansen, H. A. F. M., Nguyen, T. V. N., & Hoang, T. A. (2016). Exploring risk factors associated with intimate partner violence in Vietnam: Results from a cross-sectional national survey. International Journal of Public Health, 61(8), 923–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0879-8

- Jayasuriya, V., Wijewardena, K., & Axemo, P. (2011). Intimate partner violence against women in the capital province of Sri Lanka. Violence Against Women, 17(8), 1086–1102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211417151

- Jewkes, R., Fulu, E., Tabassam Naved, R., Chirwa, E., Dunkle, K., Haardörfer, R., Garcia-Moreno, C., & Tsai, A. C. (2017). Women’s and men’s reports of past-year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women’s risk factors for intimate partner violence: A multicountry cross-sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PLoS Medicine, 14(9), e1002381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002381

- Johnson, W. L., Manning, W. D., Giordano, P. C., & Longmore, M. A. (2015). Relationship context and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 57(6), 631–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.014

- Karamagi, C. A., Tumwine, J. K., Tylleskar, T., & Heggenhougen, K. (2006). Intimate partner violence against women in eastern Uganda: Implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health, 6(1), 284. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-284

- Kim, J. C., & Motsei, M. (2002). ‘Women enjoy punishment’: Attitudes and experiences of gender-based violence among PHC nurses in rural South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00093-4

- Kimuna, S. R., & Djamba, Y. K. (2008). Gender based violence: correlates of physical and sexual wife abuse in Kenya. Journal of Family Violence, 23(5), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9156-9

- Kouyoumdjian, F. G., Calzavara, L. M., Bondy, S. J., O’Campo, P., Serwadda, D., Nalugoda, F., Kagaayi, J., Kigozi, G., Wawer, M., & Gray, R. (2013). Risk factors for intimate partner violence in women in the rakai community cohort study, Uganda, from 2000 to 2009. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 566. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-566

- Lawoko, S., Dalal, K., Jiayou, L., & Jansson, B. (2007). Social inequalities in intimate partner violence: A study of women in Kenya. Violence and Victims, 22(6), 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1891/088667007782793101

- Lolayekar, A. P., Desouza, S., & Mukhopadhyay, P. (2020). Crimes against women in India: A district-level analysis (1991–2011). Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520967147

- Lünnemann, M. K. M., Horst, F. C. P. V., der Prinzie, P., Luijk, M. P. C. M., & Steketee, M. (2019). The intergenerational impact of trauma and family violence on parents and their children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96(9), 104134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104134

- Maguele, M. S., Tlou, B., Taylor, M., Khuzwayo, N., & Santana, G. L. (2020, December12). Risk factors associated with high prevalence of intimate partner violence amongst school-going young women (aged 15–24years) in Maputo, Mozambique. PLoS ONE, 15 (12), e0243304. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243304

- Mahapatro, M., Gupta, R., & Gupta, V. (2012). The risk factor of domestic violence in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 37(3), 153. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.99912

- Mandal, M., & Hindin, M. J. (2013). Men’s controlling behaviors and women’s experiences of physical violence in Malawi. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(7), 1332–1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1137-1

- Meyer, S., Lasater, M., & García-Moreno, C. (2020). Violence against older women: A systematic review of qualitative literature. PLoS ONE, 15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239560

- Monnat, S. M., & Chandler, R. F. (2015). Long-term physical health consequences of adverse childhood experiences. The Sociological Quarterly, 56(4), 723–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12107

- Naved, R., & Persson, L. A. (2010). Dowry and spousal physical violence against women in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Issues - J FAM ISS, 31(6), 830–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X09357554

- Ogum Alangea, D., Addo-Lartey, A. A., Sikweyiya, Y., Chirwa, E. D., Coker-Appiah, D., Jewkes, R., Adanu, R. M. K., & Kamperman, A. M. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence among women in four districts of the central region of Ghana: Baseline findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 13(7), e0200874–e0200874. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200874

- Pichon, M., Treves-Kagan, S., Stern, E., Kyegombe, N., Stöckl, H., & Buller, A. M. (2020). A mixed-methods systematic review: Infidelity, romantic jealousy and intimate partner violence against women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165682

- Reese, B. M., Chen, M. S., Nekkanti, M., & Mulawa, M. I. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors of women’s past-year physical IPV perpetration and victimization in Tanzania. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1141–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517738775

- Rubin, G. (1975). The traffic in women: Notes on the “political economy” of sex. In R. R. Reiter (Ed.), Towards an Anthropology of Women (pp. 157–210). Monthly Review Press.

- Rurangirwa, A. A., Mogren, I., Ntaganira, J., & Krantz, G. (2017). Intimate partner violence among pregnant women in Rwanda, its associated risk factors and relationship to ANC services attendance: A population-based study. BMJ Open, 7(2), 13155. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013155

- Shrestha, M., Shrestha, S., & Shrestha, B. (2016). Domestic violence among antenatal attendees in a Kathmandu hospital and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1166-7

- Simister, J., & Mehta, P. S. (2010). Gender-based violence in India: Long-term trends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(9), 1594–1611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509354577

- Srinivasan, S., & Bedi, A. S. (2007). Domestic Violence and Dowry: Evidence from a South Indian Village. World Development, 35(5), 857–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.08.005

- Stöckl, H., Watts, C., & Kilonzo Mbwambo, J. K. (2010). Physical violence by a partner during pregnancy in Tanzania: Prevalence and risk factors. Reproductive Health Matters, 18(36), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36525-6

- Study Quality Assessment Tools | NHLBI, NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved 9 August 2021, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Swanson, J. N., & Dougall, A. L. (2017). Learned helplessness. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.06475-0

- Thompson, M. P., & Kingree, J. B. (2004). The role of alcohol use in intimate partner violence and nonintimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 19(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.19.1.63.33233

- Tiruneh, F. N., Chuang, K.-Y., Ntenda, P. A. M., & Chuang, Y.-C. (2018). Unwanted pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and other risk factors for intimate partner violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Women & Health, 58(9), 983–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1377800

- Umubyeyi, A., Mogren, I., Ntaganira, J., & Krantz, G. (2014). Women are considerably more exposed to intimate partner violence than men in Rwanda: Results from a population-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-99

- Usta, J., Farver, J., & EL Zein, L. (2008). Women, war, and violence: Surviving the experience. Journal of Women’s Health, 17(5), 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0602

- VanderEnde, K. E., Sibley, L. M., Cheong, Y. F., Naved, R. T., & Yount, K. M. (2015). Community economic status and intimate partner violence against women in Bangladesh: Compositional or contextual effects? Violence Against Women, 21(6), 679–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215576938

- Walker, L. E. A. (2006). Battered woman syndrome: Empirical findings. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1087(1), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1385.023

- Wang, T., Liu, Y., Li, Z., Liu, K., Xu, Y., Shi, W., & Chen, L. (2017). Prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 12(10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175108

- Warmling, D., Lindner, S. R., & Coelho, E. B. S. (2017). Prevalência de violência por parceiro íntimo em idosos e fatores associados: Revisão sistemática. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 22(9), 3111–3125. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017229.12312017

- World Health Organization. (2009). Promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44098

- World Health Organization. (2010). Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44350

- World Health Organization. (2021). Devastatingly pervasive: 1 in 3 women globally experience violence. https://www.who.int/news/item/09-03-2021-devastatingly-pervasive-1-in-3-women-globally-experience-violence#:~:text=Younger%20women%20among%20those%20most%20at%20risk%3A%20WHO&text=Across%20their%20lifetime%2C%201%20in,unchanged%20over%20the%20past%20decade

- Yoshikawa, K., Shakya, T. M., Poudel, K. C., Jimba, M., & Kissinger, P. (2014). Acceptance of wife beating and its association with physical violence towards women in Nepal: A cross-sectional study using couple’s data. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e95829. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095829

- Yüksel-Kaptanoǧlu, İ., Türkyilmaz, A. S., & Heise, L. (2012). What Puts Women at Risk of Violence From Their Husbands? Findings From a Large, Nationally Representative Survey in Turkey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(14), 2743–2769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512438283

- Zablotska, I. B., Gray, R. H., Koenig, M. A., Serwadda, D., Nalugoda, F., Kigozi, G., Sewankambo, N., Lutalo, T., Mangen, F. W., & Wawer, M. (2009). Alcohol Use, Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Coercion and HIV among Women Aged 15–24 in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 13(2), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9333-5

- Zafar, S., Zia, S., & Amir-ud-Din, R. (2021). Troubling Trade-offs Between Women’s Work and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence From 19 Developing Countries. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605211021961. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211021961

- Zegenhagen, S., Ranganathan, M., & Buller, A. M. (2019). Household decision-making and its association with intimate partner violence: Examining differences in men’s and women’s perceptions in Uganda. SSM - Population Health, 8, 100442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100442