ABSTRACT

Over three decades, community-based tourism and sustainable tourism have emerged as innovative approaches to tourism development. Yet, only limited reviews have been conducted. Using VOSviewer software, this bibliometric review analyzed 869 Scopus-indexed documents on sustainable community-based tourism for research insights. The study suggests the recent trend has shifted from developed toward developing countries. Research foci include tourist and resident satisfaction, the effects of sustainable community-based tourism on economic growth, stakeholder participation and decision-making, and heritage conservation. Future research directions are suggested with a focus on post-pandemic resilience and the contributions of community-based tourism toward global sustainable development goals.

Introduction

Tourism is a key generative industry that contributes to economic development through both direct and indirect job creation (Sharpley, Citation2020). In fact, tourism accounts for one in 10 jobs created throughout the world (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2020). This is reflected in global economic output; Tourism contributed US$ 9.1 trillion or 10.4% of the global gross domestic product in 2019 (World Travel and Tourism Council, Citation2020). Furthermore, while tourism creates economic benefits in all countries, the effects are particularly significant in developing societies that often feature less diversified economies (Brida et al., Citation2016; Suriyankietkaew et al., Citation2022). For example, in Thailand, the tourism sector represented 20% of the nation’s GDP in 2019, a proportion predicted to rise to 30% of the GDP by 2030 (OECD, Citation2018).

However, tourism is not simply an engine for economic growth and development. When properly managed, tourism also has the potential to improve the satisfaction of community members, improve and diversify their productive capacity, conserve the environment, and preserve local cultures and heritage (Dodds et al., Citation2018; Suriyankietkaew et al., Citation2022). However, these positive effects of tourism do not happen organically. Their achievement requires intentional, cohesive, and skillful tourism management at the government, industry, community, and provider levels (Dodds et al., Citation2018; Thananusak & Suriyankietkaew, Citation2023).

Without planning and coordination, tourism providers tend to prioritize quantity over quality and short-term profits over sustainable growth (Yoopetch & Nimsai, Citation2019). This can lead to unintended negative consequences for longer-term economic, sociocultural, and environmental development (Cohen, Citation2008; Pigram & Wahab, Citation2005). For example, scholars have documented the deterioration of natural resources and local habitats due to the uncontrolled influx of tourists in both developing (Calgaro et al., Citation2014; Mondal & Haque, Citation2017) and developed societies (Moscardo et al., Citation2001; Romao & Neuts, Citation2017). There are also numerous cases in which communities have become overly dependent on unpredictable or fluctuating tourism demand (Andereck et al., Citation2005; Lasso & Dahles, Citation2018). Poor tourism development is also associated with the “commodification of local cultural heritage” (Cohen, Citation2008). This occurs when cultural artifacts, traditions, and celebrations organized and marketed to attract tourists gradually lose their meaning for the local population (Pigram & Wahab, Citation2005). These unintended negative consequences of unplanned and/or uncontrolled tourism represent threats that can undermine the sustainability of tourism as an engine of sustainable economic growth, environmental conservation, and social-cultural development (Leksakundilok & Hirsch, Citation2008). This underlines the need for identifying and refining alternative tourism models that demonstrate the potential to contribute a positive environmental, sociocultural, and economic impact on society (Bramwell & Lane, Citation1993; Johnston & Tyrrell, Citation2005).

Community-based tourism (CBT) is one model that seeks to explicitly address these concerns. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) defined community-based tourism as follows.

CBT is tourism activity, community-owned and operated, and managed or coordinated at the community level that contributes to the well-being of communities through supporting sustainable livelihoods and protecting valued socio-cultural traditions and national and cultural heritage resources. (ASEAN Secretariat, Citation2016, p. 2)

Nonetheless, the knowledge base on CBT as a “sustainable tourism strategy” has yet to be fully documented or analyzed (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2018; Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Graciano & Holanda, Citation2020; Joo et al., Citation2019). Thus, scholars lack a comprehensive perspective on the literature that explicitly links CBT and sustainability. In this review, the concept of sustainability in CBT refers to the ability of community-based tourism initiatives to balance environmental, socio-cultural, and economic considerations. It ensures long-term benefits for the local community, by generating income and employment, creating inclusive economic opportunities, preserving natural and cultural resources, and fostering responsible tourism practices.

The purpose of this bibliometric review of research is to examine how the concept of sustainability has been used to refine current conceptualizations of community-based tourism. The review addressed the following research questions:

What do the size, growth trajectory, and geographic distribution of the literature on sustainability in community-based tourism suggest about the evolution of this tourism approach?

What concepts and issues are highlighted by the analysis of the most highly cited documents in the literature on sustainability in community-based tourism?

What is the intellectual structure of the knowledge base on sustainability in community-based tourism?

Which topics in research on sustainability in community-based tourism have received the greatest attention in the literature over time, and which topics represent the research front in this literature?

This study employed the bibliometric review method to analyze 869 Scopus-indexed documents related to sustainability in community-based tourism (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Descriptive statistics, citation, co-citation, and co-word analysis were conducted using VOSviewer software 1.6.18 (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020).

This review was undertaken to extend prior review of the literature on sustainability and community-based tourism (see also Álvarez-García et al., Citation2018; Graciano & Holanda, Citation2020). The science mapping techniques employed in this review clarify the theoretical relationship between these concepts and highlight the distinctive contributions that can be gained by examining them together. The review's findings support the development of an evidence-based literature the role that community tourism can play in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) and building a sustainable planet (Zimring & Bosch, Citation2008).

Method

A bibliometric review is a type of systematic research review that analyzes bibliographic data associated with a set of documents rather than research findings extracted from the studies (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Bibliometric software enables this review method to manage and analyze more documents than possible with meta-analysis, scoping, or integrative review methods.

Identification of documents

The Scopus database was selected for use in this review. Scopus offers a rigorous and searchable source for reviews in the social sciences (Falagas et al., Citation2008; Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016). Moreover, Scopus has facilities for the export of bibliographic information about documents, the data employed in bibliographic reviews.

In this review, a keyword-based search strategy was applied. The initial Scopus search used five keywords: community-based tourism, community tourism, rural tourism, sustainable, and sustainability. The authors included “rural tourism” since CBT initially emerged as a branch of the root concept of rural tourism. The search terms were entered into the Scopus search engine as follows.

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Community based tourism”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Community tourism”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Rural tourism”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Sustainable”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY. (“Sustainability”)

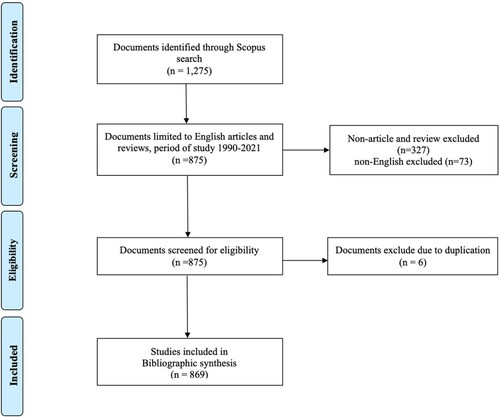

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of source identification procedures used in the CBT review (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Data analysis

The bibliographic data derived from the 869 documents were exported from Scopus to an Excel file. The Excel spreadsheet contained information on the authors, author affiliations, year of publication, journal name, abstract, keywords, and various citation data. These represented the raw data used in the review (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015).

The Excel data file was uploaded to the VOSviewer version 1.6.17 software (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020) to facilitate data cleaning. A thesaurus file was created to “disambiguate” the data. The thesaurus file replaces similar keywords (e.g. tourist and tourists) or author names (Dangi, T.B. and Dangi, T.) with a common term (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014). The thesaurus file was uploaded into the VOSviewer software during data analysis to ensure accurate results (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015).

Descriptive statistics generated by Scopus analytical tools and Excel were used to explore the review database's size, growth trajectory, and geographic distribution of documents. Tableau software (Tableau, 2008–2020) was used to create a heat map representing the geographic distribution of documents in this literature. Citation and science mapping analyses were conducted in VOSviewer version 1.6.17 (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020).

Scopus citation analysis and co-citation analysis were applied to assess the impact and influence of authors and documents in this literature (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Citation analysis measures scholarly impact by counting the frequency with which an author or document in the review database had been cited in other Scopus-indexed documents (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Therefore, we refer to “citation impact” in terms of ‘Scopus citations’.

Scholars have used co-citation analysis as a complementary means of gaining insight into scholarly impact (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). We wish to highlight four interrelated features of co-citation analysis. First, when executed in VOSviewer software, author co-citation analysis tracks the frequency with which authors have been “cited in the reference lists of the review documents.” This contrasts with citation analysis, which tracks citations of the review documents. For example, assume that B. Bramwell is frequently cited in the reference lists of the S-CBT documents (co-citations), we interpret this as a measure of his influence on this literature. Thus, co-citation analysis identifies influential authors whom S-CBT scholars have referenced for conceptual support (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022).

Second, “co-citation analysis” also tracks the frequency with which any two authors have been “cited together” in the reference lists of the review documents (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015, p. 431). This analysis is based on the empirically supported observation that authors frequently appearing in the same reference lists tend to evidence a similarity in intellectual approach or perspective (Small, Citation1973; White & McCain, Citation1998). For example, assume that a document authored by D. Getz and another authored by B. Bramwell appear in the reference list of an S-CBT document in the S-CBT review database. In this case, each author would accrue one “co-citation” as well as a “co-citation link” (i.e. between Getz and Bramwell). If Getz and Bramwell accrue numerous “co-citation links,” it suggests that their published works have an intellectual affiliation or similarity (Hallinger & Kovačević, Citation2022; White & McCain, Citation1998).

In addition, when executing author co-citation analysis VOSviewer creates a matrix of co-cited authors. This matrix is then used to create a co-citation map that visualizes relationships among authors in the literature based on their co-citation links (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014). In the current study, an author co-citation map was developed with the goal of gaining insight into the “intellectual structure” of the S-CBT literature. Intellectual structure refers to the dominant theoretical streams of research resulting from the self-organized efforts of scholars working within a similar domain of scholarship (White & McCain, Citation1998).

Co-citation analysis is based on the “reference lists of review documents.” Thus, it overcomes the limitation of relying on any single database as the source of documents for review. In other words, despite Scopus’ extensive coverage, it does not include the entire literature. By accessing the reference lists of the Scopus-indexed documents in our S-CBT dataset, co-citation analysis was able to identify other relevant authors who have influenced scholarship in this field of study.

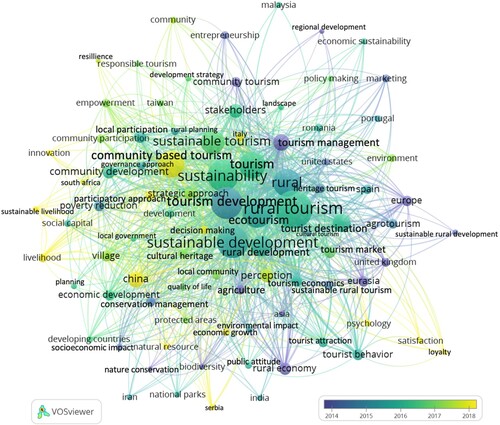

The authors employed keyword co-occurrence analysis (co-word analysis) in VOSviewer to analyze the topical composition of this literature. Keyword analysis proceeded in three steps. First, VOSviewer was used to calculate frequency counts of terms appearing in the review documents’ titles or keywords. Raw frequency counts are useful in identifying topics of high interest.

Second, like co-citation analysis, co-word analysis was used to “calculate the number of publications in which two keywords occur [ed] together (i.e. co-occur) in keyword lists of documents included in the review database” (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014, p. 287). After tracking the co-occurrence of terms, the authors used VOSviewer to generate a “map that visualized similarities in relationships among frequently co-occurring keywords” (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014). Co-word analysis was used to complement author co-citation analysis to visualize conceptual themes in the literature.

Finally, “temporal co-word analysis” was used to identify the research front or emerging topics studied in the S-CBT literature. A temporal overlay on the basic co-word map highlights the period in which different topics have been more (or less) popular. For example, assume that the term “stakeholder participation” has appeared in 37 documents published between 1998 and 2021. VOSviewer tracks the publication year of each of the 37 documents and then calculates a “mean year of publication.” If the mean publication year calculated from the 37 documents was 2005, we could reasonably conclude that this keyword was more popular during the early years of this literature. In contrast, if the mean year was 2017, we could conclude that studies focusing on stakeholder participation were concentrated in the more recent period of this literature’s evolution. This is highlighted on the map through the use of color coding that differentiates the temporal variation among keywords.

Results

The findings are organized according to the four research questions outlined above.

Landscape of the S-CBT literature

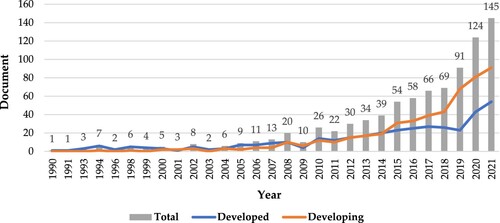

Bramwell (Citation1990) published the first Scopus-indexed article related to sustainability in CBT. The subsequent growth trajectory of this literature shows that scholarly interest in sustainability in CBT grew slowly from 1990 to 2007 before gathering momentum around 2010 (see ). Growth in the past decade has accelerated in concert with the global dissemination of the sustainable development goals. Sustainable tourism and variants such as community-based tourism have become identified as desirable alternative approaches to mass tourism.

Figure 2. Growth trajectory of publications on sustainability in community-based tourism, 1990–2021 (n = 869 documents).

The data presented in further suggest that the recent growth in S-CBT scholarship has been mainly driven by publications authored in developing countries. This is significant given the broader dominance of English-language scholarship in the global research literature. This trend may also reflect a perception that sustainability-oriented, community-based tourism is well suited to the needs and conditions of developing societies (Hsu et al., Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2022).

Analysis of the geographic distribution of this literature extended the latter finding. The 869 Scopus-indexed documents were distributed across 98 countries, affirming global interest among tourism scholars. Yet, while Anglo-American and European-based scholars have made leading contributions to this literature (e.g. USA 82 articles, UK 78, Spain 83), developing societies are far more prominent in this literature than might have been expected. In fact, scholars based in China (94), South Africa (69), Malaysia (47), Thailand (29), Indonesia (24), and Korea (24) have begun to develop a critical mass of scholarship on S-CBT from developing nations. In fact, the trend addressed the knowledge gap and currently lacking studies in this growing field, particularly in the developing countries when compared to the developed nations. The result suggests future opportunities for more studies to advance the S-CBT research front.

The identification of China-based authors as the most prolific source of scholarship on this topic can be attributed to two factors. The first is the rapid growth of the tourism sector in China since 2010. The second is the solid policy-driven attention and funding for research on sustainable tourism by the Chinese government since 2007. The Chinese literature has focused mainly on sustainable rural tourism (Hsu et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2021), destination development (Gao et al., Citation2019; Wang & Lin, Citation2021), and ecotourism (Zheng et al., Citation2021).

Key concepts and issues highlighted by highly-cited documents

Analysis of the 20 most cited documents revealed a concentration of conceptual and empirical studies, with few research reviews. The paucity of research reviews in is surprising since reviews often feature among the most highly-cited papers in mature literatures. Further analysis of the full document dataset found only eight research reviews in total, with two focusing on specific countries (i.e. Mexico, Botswana) and none on sustainability in CBT.

Table 1. The 20 top-cited Scopus documents in the literature on sustainability in community-based tourism.

The concept of sustainable development was introduced in the Brundtland Report in 1987, placing “sustainability” within a political framework capable of application across different academic disciplines (Saarinen, Citation2006). This report envisioned the possibility of achieving a balance between economic development and sustainable use of natural resources (Lane, Citation1994a). The term “sustainable tourism” emerged as a new approach in tourism and hospitality. Bramwell and Lane first introduced the term “sustainable tourism” as an economic development model designed to promote the quality of life of local communities, support tourism experiences in travel destinations and preserve the environment of tourist attractions (Lane, Citation1994a). Since then, there has been a growing number of literatures on the discussion around the conceptual structure of sustainable tourism among academics and professionals (Lane, Citation2018).

Sustainable tourism is widely interested by academic researchers from developed and developing nations. Sustainable tourism has evolved from a purely reactive to a proactive concept. In the past, it has studied the negative impacts of tourism and how to mitigate them to protect nature. Currently, most academic research is focused on implementation and management models that develop innovation and competitiveness through management (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2012). Sustainability has been the central theme in tourism discussions and management policies (Ryan, Citation2002; Saarinen, Citation2006). So, there is a growing need to understand the nature of constraints on tourism growth. The study by Saarinen (Citation2006) explored how these limits are approached and evaluated in the different sustainability principles, namely resource-based, activity-based, and community-based. Each principle has its own advantages and limitations when utilized in sustainable tourism processes.

There are many forms of sustainable tourism that have developed. Rural tourism is an alternative means of promoting local community development and social empowerment while driving sustainable economic growth through tourism (Lane, Citation1994b). Rural tourism has grown over the past four decades because there is good community acceptance that tourism is a viable economic activity. There is also an increasing demand due to changes in the lifestyle of tourists, the desire to engage more in outdoor recreation, and the growth of micro-mobility. At first, rural tourism emerged as a rural diversification tool to compensate for declining income from the agricultural sector (Mbaiwa & Stronza, Citation2010). Later, rural tourism entered a consolidated growth stage. Lifestyle entrepreneurs entered rural tourism with new skills and resources. Rural tourism activities transform into a complex and multifaceted business during this phase (Garrod et al., Citation2006). Food and wine are fast-growing and important sectors of rural tourism. The study by R. Sims examined how one artifact of local culture, food, can contribute to the sustainable tourism experience (Sims, Citation2009). Sim argues that local food can enhance the visitor experience by connecting consumers with the region and its perceived culture and heritage. Local foods are conceptualized as “authentic” products that symbolize the place and culture of the destination.

Choi and Sirakaya (Citation2006) developed objective indicators to measure community tourism development within a sustainability framework using a modified Delphi technique. One hundred twenty-five objective indicators cover six interdependent and collectively supporting dimensions that serve as the basis of community development: political, social, ecological, economic, technological, and cultural. This study expands the monitoring system for managing community tourism development, which is an essential step in tourism planning. Moreover, many scholars have since used their sustainability indicators to formulate a set of indicators to evaluate the performance and impacts of tourism at the local and regional levels.

Another study by Choi and Sirakaya (Citation2005) validated a subjective indicator that evaluated the attitudes toward sustainable tourism (SUS-TAS). These scales have been used to measure residents’ attitudes and perceptions. It is a valuable assessment tool for academic researchers and practitioners, as it provides insight into how residents regard tourism. These subjective indicators can be used jointly with objective measures to provide a broader picture and help decision-making and tourism planning personnel evaluate current tourism and strengthen the results of future tourism development.

Over the past three decades, research on resident attitudes toward tourism and its impact has gained wide interest among scholars. Studies by Choi and Murray (Citation2010) used social exchange theory to explain the residents’ significant role in tourism development, as they are directly affected by tourism. Social exchange theory looks at interactions from a cost–benefit perspective. People tend to trade using their perceptions and intention. These findings confirmed three elements of sustainable community tourism: long-term planning, full community participation, and environmental sustainability are predictors of residents’ perception and behavioral intentions. Additionally, the perceived positive and negative impacts significantly influence future tourism support.

Intellectual structure of the CBT literature

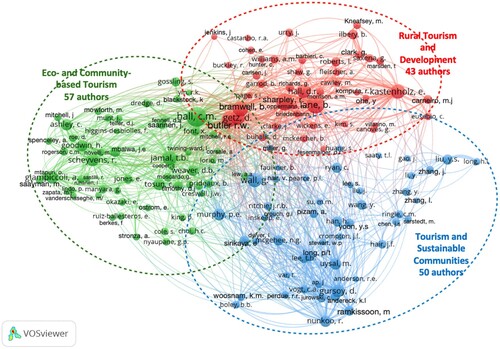

An author co-citation map was generated to reveal the underlying intellectual structure of the S-CBT literature (Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). The co-citation analysis of authors identified 37,825 authors in the reference lists of the 869 review documents. Using a threshold of 38 author co-citations, VOSviewer software generated an author co-citation map that displays the 150 most highly cocited in the S-CBT literature (see ).

Figure 4. Author co-citation map of the sustainability in community-based tourism knowledge base (threshold 38 author co-citations, display 150 authors), map generated in VOSviewer 1.6.18 (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020).

On this map, the colored nodes represent authors, with the size reflecting the frequency of author citations in the reference lists of the review documents. The thickness of the line connecting any two nodes suggests their co-citation frequency, a measure of theoretical similarity between their published works (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014). The distance between nodes on the map indicates “similarity,” with nodes closer to one another suggesting closer intellectual affiliation. Finally, the colored clusters on the map group authors of a similar intellectual persuasion. These clusters have been interpreted as “schools of thought” that comprise the intellectual structure of the literature.

The author co-citation analysis map reveals three distinctive and coherent schools of thought in the S-CBT literature. These are: (1) Eco- and Community-based Tourism, (2) Tourism and Sustainable Communities and (3) Rural Tourism and Development. Eco- and Community-based Tourism is the largest school of thought, comprised of 57 authors. This school is led by C.M. Hall (375 co-citations), E. Kastenholtz (195), T.B. Jamal (188), R. Scheyvens (146), A. Giampiccoli (143), and C. Tosun (134). This school provides the theoretical foundations for the development of ecotourism and community-based tourism (Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Hall & Page, Citation2014; Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2019; Scheyvens & Biddulph, Citation2018; Tosun, Citation2006). Kastenholz, for example, pioneered the conversion of rural tourism from sightseeing into a broader set of experiential activities. Her scholarship also elaborated on issues related to governance, leadership, networking, product development and marketing in the rural tourism context (Kastenholz et al., Citation2012; Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015).

The concept of ecotourism emerged in the 1980s as a path toward sustainable tourism by focusing on environmental protection in the context of tourism. In fact, over time, ecotourism and sustainable tourism became closely associated (Moyle et al., Citation2020). Ecotourism has been adopted by providers who aim to lessen the effects of traditional tourism on the environment. Thus, ecotourism emphasizes the need for proactive efforts to reduce pollution, waste, and depletion of natural resources (Scheyvens, Citation1999; Weaver, Citation2005). Community-based tourism has increasingly embraced these facets of eco-tourism.

Hall conceptualized sustainable tourism development by forming five fundamental principles, namely (1) holistic strategy, which considers all three pillars of sustainability which are environmental, social, and economic aspects, (2) preservation of natural ecology, (3) development which maintain productivity for the future, (4) conservation of human cultural heritage and biodiversity, and (5) promotion of equal opportunity and fairness (Hall & Page, Citation2014). Local community participation is fundamental in ecotourism and community-based tourism (Scheyvens, Citation1999). The power, objectives, and expectations can vary levels of community participation levels, and this shapes their attitudes towards forms of community participation (Tosun, Citation2006).

The second school of thought, represented in blue, suggests a theme of Tourism and Sustainable Communities. This cluster, consisting of 50 authors, is led by G. Wall (199 co-citations), D. Gursoy (149), M. Uysal (130), P.E. Murphy (129), and R. Nunkoo (124). This school highlights the importance of tourism planning for both residents and visitors (Liu & Wall, Citation2006). Thus, authors in this school have highlighted concepts such as stakeholder engagement (Ryan, Citation2002) and sustainable livelihoods as essential to sustainable tourism planning. Stakeholder engagement highlights the diverse contributions tourism providers, government, NGOs, and community members need to achieve sustainable communities.

The concept of sustainable livelihoods emphasizes that tourism must be understood in the broader economic and cultural context in which it takes place (Su et al., Citation2019; Tao & Wall, Citation2009). Livelihood sustainability is measured using the two-dimension framework of livelihood diversity and livelihood freedom (Su et al., Citation2019). Nunkoo and Gursoy identified that the occupational, environmental, and gender identities of the residents influence their attitudes toward and behavioral support for tourism. Therefore, community-based tourism supports the adoption of a sustainable livelihoods approach for residents in destination cities (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012). A study by Lee showed that the commitment to the natural environment is correlated with the destination’s attachment, participation in recreational activities, and responsible mindset and behaviors toward nature (Lee, Citation2011).

The third school of thought (red cluster) suggests a theme of Rural Tourism and Development. This school consists of 43 authors led by B. Lane (298 co-citations), R. Sharpley (264), R.W. Butler (220), B. Bramwell (214), and D. Getz (202). Lane founded and co-edits the Journal of Sustainable Tourism and together with Bramwell introduced the term “sustainable tourism” in 1993. They defined sustainable tourism as a model of economic development designed to promote the quality of life of local communities, support tourist experiences in tourism destinations, and sustain the environment of the tourism destinations (Bramwell & Lane, Citation1993). Lane and Kastenholz (Citation2015) asserted that rural tourism has two essential characteristics. First, tourism provides employment for rural inhabitants, thus reducing unhealthy migration to urban areas and the hollowing out of rural communities. Second, rural tourism can contribute to the development of the physical and cultural infrastructure of rural communities.

The authors of this school have focused on describing the evolving nature of rural tourism activities and their effects on rural communities. Scholars have documented that tourism can raise levels of social cohesion and pride in rural communities (Choi & Turk, Citation2011; Sharpley, Citation2020), reverse declining economic productivity (Mccool et al., Citation2013; Saxena et al., Citation2007), and reduce an overdependence on agriculture (Kastenholz et al., Citation2012; Komppula, Citation2014).

However, authors adopting a sustainability perspective have noted that these positive effects of rural tourism are not always achieved. Lack of planning, stakeholder participation, and a “sustainability mindset” can produce uneven, short-term, unsustainable economic gains, depletion of natural resources, and community conflict. Whether or not rural tourism has positive or negative impacts on the community quality of life and environment depends on various factors that can be shaped by government policy, community leadership, local planning, and community awareness (Uysal & Sirgy, Citation2019). The concepts of carrying capacity and tourism life cycle are increasingly incorporated into the planning process for sustainable rural tourism (Butler, Citation2019; Jamal & Getz, Citation1995).

Topical trends in sustainability in community-based tourism knowledge base

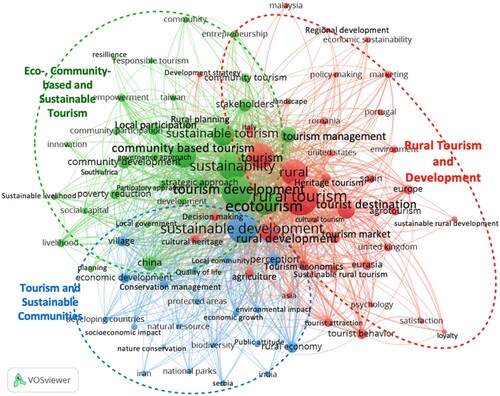

Topics studied in the literature on S-CBT were analyzed using the keyword co-occurrence feature of VOSviewer software. First, the most frequently occurring keywords are extracted from the titles, keywords, and abstracts of our review documents. These were rural tourism (309), sustainable development (227), tourism development (220), ecotourism (187), rural (170), tourism (165), community-based tourism (157), sustainable tourism (135), rural development (101), tourist destination (76) and tourism management (68).

Next, a “co-word map” was generated in VOSviewer. The co-word map offers a complementary means of gaining insight into the dominant conceptual themes that have emerged through the self-organized efforts of scholars to study S-CBT. Using a threshold of 9 keyword occurrences, the map displays 89 keywords (see ). The co-word map is interpreted using similar guidelines as those outlined for the co-citation map. The difference is that keywords are substituted for author names in the analysis and interpreted as topics.

Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence map of S-CBT literature, 1990–2021 (threshold 9 co-occurrences, display 89 keywords, map generated in VOSviewer software (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2009, Citation2020)).

The three conceptual themes that emerged from this analysis (see ) align closely with the “schools of thought” highlighted in the author co-citation map in . They are: (1) Rural Tourism and Development, (2) Eco- and Community-based Tourism, and (3) Tourism Development and Community Livelihood. It is interesting to note that the frequently occurring keywords/topics stated above are clustered closely in the center of the map, with dense links to one another. This suggests that these terms represent this literature's closely connected conceptual building blocks.

The first conceptual theme (red cluster) is centered on Rural Tourism and Development. The main topical keywords in this category are rural tourism (309 occurrences), rural (178), tourism (165), rural development (101), tourist destination (76), tourism market (35), tourist behavior (33), heritage tourism (26), agrotourism (25), tourist attraction (24), decision making (22) and cultural heritage (21). The authors of this school have elaborated on the emergence of a greater diversity of rural tourism activities. These include agrotourism, food tourism, cultural tourism, heritage tourism, farm-based tourism, and nature-based tourism (Frochot, Citation2005; Roberts & Hall, Citation2004). The economic benefits of rural tourism have received the most attention from researchers (Cánoves et al., Citation2004; Lane, Citation1994b).

The second conceptual theme (green cluster) is composed of Eco-, Community-based, and Sustainable Tourism. The most frequently occurring keywords in this theme are tourism development (220 occurrences), sustainability (210), ecotourism (187) community-based tourism (157), sustainable tourism (135), tourism management (68), stakeholders (50), community development (42), local participation (39), poverty reduction (29), and strategic approach (27). This category highlights the effects of tourism activities on the environment, including studies of resource exploitation and depletion, and environmental impact. Sustainability has emerged as a unifying concept by providing a strategic focus for tourism planning and development. Sustainable tourism requires responsible policies and sound community governance that include multiple stakeholder groups, and engage local participation in the processes (Butler, Citation2019; Pastras & Bramwell, Citation2013). Concepts such as the triple bottom line have also clarified and highlighted the need to set balanced goals for tourism development in communities (Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Dwyer, Citation2005).

The third conceptual theme (blue cluster) focuses on Tourism and Sustainable Communities. The main keywords in this category are sustainable development (227 occurrences), perception (42), rural economy (36), village (32), conservation management (23), local economy (18), protected areas (15), public attitude (14), environmental impact (14), socioeconomic impact (13) and quality of life (10). In this theme, sustainability has been integrated as part of an organization, and can reinforce the image of a company or enterprise, which can be seen from the keywords such as environmental impact, socioeconomic impact, and conservation management (Alonso-Almeida et al., Citation2018; Ayuso, Citation2006). Conservation of nature, the locals’ quality of life of locals, cultural development, economic improvement, and tourist satisfaction are essential drivers that make sustainable community tourism possible (Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Lee & Jan, Citation2019). This thematic cluster is different from the green cluster in that it is not exclusively focused on rural tourism. Instead, scholars in the blue cluster have adopted a broader perspective on sustainable tourism across all contexts.

In our final research task, we applied temporal co-word analysis to identify topics that have featured in the most recent S-CBT literature. The temporal overlay map in is interpreted similarly to the map in co-word in , except that the colors refer to the time period in which the topic has featured. More specifically, the yellow and bright green nodes in are associated with topics of recent interest, while the darker nodes indicate topics that were popular earlier in the evolution of this literature (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014; Zupic & Čater, Citation2015). Thus, when interpreting this map, the reader should attend to both the nodes’ color (recency) and size (frequency) associated with different keywords/topics.

Figure 6. Temporal keyword co-occurrence map of the sustainability in S-CBT literature, 1990–2021 (threshold 9 keyword occurrences, display 89 keywords, map generated in VOSviewer software, van Eck & Waltman, Citation2009, Citation2020).

Upon revisiting the country names listed on the map, it becomes apparent that early researchers on S-CBT were primarily based in developed countries, including the United States, the UK, and various European nations. However, more recent researchers tend to originate from developing societies, such as China, South Africa, Vietnam, Thailand, and Serbia.

Topic-related keywords that have emerged as significant in the five years (i.e. yellow and bright green) include several clusters of related keywords related to stakeholder engagement, socio-economic benefits, environmental impact, and community-based tourism.

Stakeholder engagement: participatory approach, community participation, empowerment, governance;

Socio-economic benefits: economic growth, sustainable livelihoods, livelihoods, community development, quality of life, resilience, cultural heritage, satisfaction, loyalty;

Environmental impact: protected areas, environment;

Community-based tourism: community-based tourism, responsible tourism, strategic approach, decision making, innovation, community, village, local community.

These four themes capture the current foci of research on S-CBT. Taken together, they highlight the currency of interest in both S-CBT processes (e.g. stakeholder engagement, governance, decision-making) and the social, economic, and environmental effects of community-based tourism on communities, especially, but not limited to, rural communities. Notably, most of the emerging topics highlighted in yellow and bright green are located within the boundaries of the Eco-, Community-based, and Sustainable Tourism cluster and to a lesser degree in the Tourism and Sustainable Communities cluster identified in . Very few emerging topics within this field are located within the conceptual boundaries of rural tourism and development. This is a potentially important finding for understanding how the lens of sustainability is reshaping community-based tourism.

Discussion

This analysis aims to identify how the concept of sustainability provides additional leverage to understand the nature and effects of community tourism. In this section, the authors provide a summary of the scholarship in the S-CBT field, interpret the main findings, discuss implications of the review, address limitations and suggest future directions.

Interpretation of the findings

The review identified 869 Scopus-indexed S-CBT documents published between 1990 and 2021. The literature on sustainability in CBT grew slowly from 1990 to 2007. The volume of publication began to increase dramatically since 2008. There was consistent growth during the review period. The literature on S-CBT is widely distributed across 98 countries spanning all continents. While the literature from 1990 to 2010 was predominantly dominated by scholarship based in developed countries, the more recent literature exhibits a more balanced representation, with significant contributions from developing societies. The contribution of China-based scholars to this review is particularly notable. Our finding regarding the growth of scholars from developing world also aligns with the previous reviews of research on the community-based tourism (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2018; Graciano & Holanda, Citation2020). The increased contribution from the scholars based in developing countries also reflects the continuing growth of the emerging research front, which has oriented toward community-based tourism and sustainability focus in these countries.

Author co-citation and co-word analyses revealed this literature's remarkably consistent “intellectual structure.” Specifically, the emerging knowledge base on sustainable community-based tourism is comprised of three distinctive, coherent schools of thought: (1) Eco- and Community-based Tourism, (2) Tourism and Sustainable Communities, and (3) Rural Tourism and Development (see and ).

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of author affiliations, including the first author in Scopus-indexed publications on sustainability in community-based tourism, 1990–2021, with a world map (n = 869 documents).

The Eco- and Community-based Tourism School highlights the effects of tourism activities on the environment, including studies of resource exploitation and depletion and environmental impact. Sustainability has emerged as a unifying concept by providing a strategic focus for tourism planning and development. Sustainable tourism requires responsible policies and sound community governance that include multiple stakeholder groups and engage local participation in the processes.

The second school of thought, focusing on tourism and sustainable communities, highlights the importance of tourism planning for both residents and visitors. Stakeholder engagement and sustainable livelihoods are essential for sustainable tourism planning (Kunjuraman, Citation2023). Sustainability has been integrated as part of an organization and can reinforce the image of a company or enterprise. Conservation of nature, the locals’ quality of life, cultural development, economic improvement, and tourist satisfaction are essential drivers of sustainable community-based tourism.

The third school of thought, Rural Tourism and development, emphasizes rural tourism and Rural Development Processes. It focuses on describing the evolving nature of rural tourism activities and their effects on rural communities. The concepts of carrying capacity and tourism life cycle are increasingly incorporated into the planning process for sustainable rural tourism (Butler, Citation2019).

Temporal co-word analysis revealed that four themes have been featured in the most recent S-CBT literature. Currently, stakeholders are viewed as an important factor in sustainable community-based tourism policies. Scholars focus on how to identify, participate, and collaborate with stakeholders, how these stakeholders can participate more effectively in the development and implementation of sustainable tourism policies, and how to encourage full community participation and empowerment (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Jaafar et al., Citation2020; Ruiz-Ballesteros, Citation2023; Wondirad et al., Citation2020).

The second theme is on the socio-economic benefits. Community-based tourism is considered a driving force for increasing income and employment opportunities. Recent studies focus on how to assess socioeconomic sustainability through various indicators such as local quality of life (Uysal & Sirgy, Citation2019), sustainable livelihood (Su et al., Citation2019), cultural development, and tourist satisfaction (Lee & Jan, Citation2019).

The third theme is about environmental impact. The attention given to environmental protection is growing in tourism development. This theme focuses on community-based tourism's role in conserving the environment and protecting natural resources and how CBT can lessen the negative impact of over-tourism or unplanned tourism activities (Hsu et al., Citation2020; Kim & Kang, Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2021).

Finally, community-based tourism is the fourth theme. This theme highlights the importance of sustainability from a strategic point of view. Sustainable CBT is responding to the need for more responsible policies and forms of corporate governance in the sector, which embed local community participation in the decision-making process and how to create innovative products and infrastructure that harmonies the environment (Dangi & Petrick, Citation2021; Scheyvens & van der Watt, Citation2021).

Furthermore, the concept of sustainability can be used to refine current conceptualizations of community-based tourism (CBT) by incorporating principles and practices that balance environmental conservation, socio-cultural integrity, and economic viability. This entails considering the long-term impacts and benefits of tourism activities for the local community, environment, and overall destination. Integrating sustainable practices into CBT may include incorporation of carbon footprint reduction, cultural heritage preservation, promoting responsible tourism behavior. The concept of sustainability can enhance the overall planning, management, and outcomes of CBT initiatives. The sustainability-oriented CBT framework can support tourism development. It can support economic benefits, social development and environmental responsibility, thereby contributing to the long-term well-being of local communities and preservation of natural and cultural resources.

Researchers (e.g. Bramwell, Weaver) look at “sustainability” as the results or outcomes of CBT practices and the systematic mindset or vision-oriented toward community participation, the learning process, and how the community decides any actions (Álvarez-García et al., Citation2018; Bramwell et al., Citation2017; Moyle et al., Citation2020). The concept of sustainable CBT is not only focused on the environmental aspect. According to previous literature, sustainable CBT must uphold three principles as the following.

Economic sustainability where CBT can benefit from the increase in income and lessen the poverty. The community should also consider other negative consequences caused by over-tourism, such as increased cost of living and migration of outsiders into the community.

Socio-cultural sustainability where CBT can preserve traditional cultures; however, “cultural commoditization” should put in precautions.

Ecological sustainability where CBT can help conserve the natural resources and enrich biodiversity. The community should help reduce negative impacts on the physical environment, such as exploitation of waste or natural resources (Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016; Dodds et al., Citation2018). The concept of how a community withstands natural and human-induced external crises should be incorporated into the desired sustainability outcomes (Bui et al., Citation2020; Calgaro et al., Citation2014).

A recent study by the authors (Suriyankietkaew et al., Citation2022; Thananusak & Suriyankietkaew, Citation2023) affirms that CBT is an alternative self-reliant, self-sufficient, and sustainable business model for sustainable tourism. The research provides evidence that the CBT business cases can survive and thrive for resilience and sustainable futures, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in conjunction with the UN SDGs, CBT is critical for inclusive socio-economic growth in rural and disadvantaged communities to achieve sustainable development.

Implications of the findings

This geographic distribution focus on the United States, UK, and Spain suggests a knowledge gap in developing countries. It is implied that more research in the emerging field is needed in developing countries. To address this need, journals could sponsor special issues focusing on sustainability in CBT in developing countries. This would sustain the growing momentum in contributions from scholars in developing countries and broaden our understanding of challenges and solutions in different contexts (Yoopetch & Nimsai, Citation2019). It is suggested that future journals may sponsor special issues on emerging themes relevant to developing countries in CBT. Derived from our resulting topical keywords, we recommend that possible themes may include stakeholder engagement and participatory approaches toward S-CBT or studies of sustainable best practices relating to community participation, community empowerment, and community governance. The themes may present opportunities to investigate innovative sustainability practices and sustainable outcomes in CBT. Another suggested theme may be linked to sustainable livelihoods, quality of life, community resilience and sustainability impacts on culture, society and economy toward building S-CBT. The suggested themes for the special issues may contribute to further theoretical development and advance S-CBT knowledge in developing countries.

The research in S-CBT shares a similar pattern and trend in tourism research. However, the theoretical research development in this field is still underdeveloped (Correia & Kozak, Citation2022). Thus, we suggest that future research development can focus on the following issues. Encouraging interdisciplinary research collaboration among researchers may expand our perspectives in S-CBT. Examining contextual factors that are related to S-CBT, such as local traditions and governance structures, may enrich our limited understanding. Furthermore, comparative studies across different communities, regions, or countries may reveal insights about different sustainability practices and practical implications in S-CBT. Our recommendation may contribute to advance the theoretical foundations of S-CBT and fostering its sustainable development.

The empirical research in this domain mainly focuses on small sample sizes, descriptive surveys, and case studies. Moving away from this limitation, our study implies that future studies should employ a more advanced research design methodology that facilitate a larger-scale investigation and multiple cross-case comparison to understand impact on S-CBT. Moreover, fostering research partnerships and promoting international collaboration among scholars from diverse countries may broaden our perspectives. Collaboration may also be extended to include data from government agencies to gain valuable insights into policy development. Longitudinal and comparative research that focuses on sociocultural and environmental changes and outcomes over time should be explored for further insightful analysis. The longitudinal studies may also deepen our understanding of the evolution and changes that impact S-CBT. Their results may contribute to better understanding diverse factors that may drive or limit transformations and outcomes to create S-CBT in different contexts.

Existing S-CBT research publications narrowly focus on single or two destinations, thus limiting the contextual interpretation and generalization issues. Researchers may further employ strategies, such as conducting multi-destination studies, utilizing comparative analysis, or employing a mixed methods approach. Multi-destination studies may capture the diversity of CBT practices across different regions, while comparative analysis may identify patterns and best practices. Employing a mixed methods approach may allow for a comprehensive understanding of S-CBT's social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions in both qualitative and quantitative sense. These strategies may contribute to a broader understanding of S-CBT, enabling researchers to draw meaningful conclusions and inform sustainable tourism practices.

In the future, we suggest that additional S-CBT studies should consider the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the research context. The COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a “disruptive influence” on tourism worldwide (Lee et al., Citation2022; Palacios-Florencio et al., Citation2021). It has created massive global unemployment in local communities and has adversely affected tourism-dependent economics with mass tourism (Lopes et al., Citation2021; Yeh, Citation2021). Despite this economic disruption, the COVID-19 pandemic has also created an opportunity for nations and local communities to rethink and redesign how tourism can be “rebooted” in a more sustainable fashion with a socio-environmental sustainability orientation (Suriyankietkaew et al., Citation2022; Cheer, Citation2020; Palacios-Florencio et al., Citation2021). Our review recommends that future researchers may incorporate the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on CBT into future S-CBT studies to comprehend its effects on sustainability and tourism practices. Upcoming studies may focus on the following areas, such as exploring the socioeconomic effects of the pandemic, evaluating community resilience, examining the environmental impacts, analyzing governance and policy responses, and investigating the utilization of digital platforms and technology adoption to understand socio-cultural or behavioral changes. These areas may help us better understand the disruptions of local livelihoods, changes in their ecosystem, adaptive strategies or resilience of local communities and policy responses. We also propose that more research should analyze how CBT could embrace digitalization by utilizing digital platforms for marketing, communication, and virtual experiences to engage with tourists as well as examine impacts of digitalization on community empowerment, participation, and preservation of cultural heritage. Therefore, researchers can gain insights into the challenges and opportunities that have emerged during the pandemic and inform future sustainable practices in CBT.

The resulting trend from the review also suggests that the demands for tourist travel have shifted toward more robust healthcare destination, engage in more mindful and meaningful tourist activities with responsible tourism after the pandemic (Bhati et al., Citation2022; Seraphin & Dosquet, Citation2020; Uglis et al., Citation2022). We suggest that future studies may focus on the emerging CBT trends with sustainability lens. Further research may explore how to build sustainable healthcare destinations through community-and-stakeholder partnership, integration of local wisdom into wellness programs, mindful tourism experience enhancement, and responsible tourism from the perspectives of local host communities and visitors. These opportunities involve providing a nature-based environment and focusing on activities that promote physical and psychological well-being (Kamata, Citation2022; Uglis et al., Citation2022). Future findings may reveal insights about opportunities for S-CBT to attract diverse tourists, generate socio-economic benefits, and preserve local culture plus the environment.

In the post-COVID-19 era, the promotion of S-CBT and responsible tourism becomes inevitably crucial to achieve the global sustainability goals. We call for future studies to link S-CBT to various SDGs. The emerging field has the potential to contribute to diverse SDGs. For instance, poverty alleviation, environmental sustainability, cultural preservation, social inclusion, well-being, and partnerships for sustainable development. Further studies will need to investigate how specific CBT mechanisms, indicators, or factors, such as community participation, capacity building, and policy frameworks, may effectively support varied SDGs. Future research should explicitly connect theoretical and practical implications to SDGs and elaborate how they foster inclusive socio-economic growth and advance the common global goals. Furthermore, future S-CBT studies can employ SDG-related frameworks for data analysis and result interpretation within the context of the SDGs.

Lastly, our result suggests three upcoming conceptual themes: ecotourism, responsible tourism, rural tourism, and community-based tourism. Therefore, the future of tourism should head forward to these emerging themes, moving away from the pre-COVID mass tourism. Further studies may examine how to implement sustainability principles/practices as well as promote the alternative tourism development in diverse settings. Their findings may provide further insights and enable us to understand possible sustainability strategies and sustainable tourism management to support further development of ecotourism, responsible tourism, rural tourism, and community-based tourism. As a result, future findings may benefit small or rural communities, particularly the aspects of socio-economic impacts, local heritage, environmental conservation, and stakeholder engagement. Our review results can overall contribute to resilience and post-COVID recovery in the tourism sector, paving a path towards a more sustainable and inclusive future.

Limitations and future directions

Two limitations deserve elaboration. Firstly, our bibliometric review mainly provides an overview that examines the landscape of existing scholarship and theoretical structure of the emerging literature. For more in-depth analyses, future scholars should conduct integrated or scoping reviews to extract and analyze specific findings from individual studies in the literature. Secondly, this review specifically focused on articles and reviews published in English-language journals, which was a deliberate choice rather than a limitation. Setting boundaries by prioritizing English-language literature allowed for a more manageable scope and a focused analysis within the available resources. However, it is important to acknowledge that Graciano and Holanda's (Citation2020) review indicates that a significant body of literature on community-based tourism is also published in other languages. Therefore, it is recommended to interpret the findings of this review in conjunction with findings from bibliometric reviews conducted on related literature published in other languages in the future.

The analytical software used in this review, VOSviewer, does not support the utilization of data from multiple databases. However, Scopus is a robust and searchable source for reviews in the social sciences (Falagas et al., Citation2008; Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016). Moreover, other databases, such as Web of Science and ProQuest, should be incorporated in the future. Researchers can also explore alternative analytical software tools that can accommodate multiple databases. Another approach is to conduct a systematic review, which involves systematically searching and analyzing literature from multiple databases. This rigorous methodology ensures a comprehensive synthesis of available evidence and minimizes potential bias, leading to a more complete coverage of the literature. Supplementary keywords, such as agritourism, agrotourism, ecotourism, responsible tourism, and/or people-to-people tourism, can be included to enhance the search to help capture a broader range of literature on S-CBT.

In addition to our international research, it is highly recommended that future studies prioritize specific regional orientations or emerging economies in the field of CBT. Supporting this recommendation, a study by Mowforth and Munt (Citation2015) highlighted the significance of examining CBT practices in diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts. Additionally, conducting comparative research may provide valuable insights. For instance, a comparative analysis of CBT initiatives in different regions has the potential to identify patterns, trends, and best practices, as demonstrated by the work of Hall and Page (Citation2014). To further advance our understanding, it is crucial to conduct more empirical research focusing on emerging themes such as rural tourism, eco-tourism, and CBT. This aligns with the findings of a study by Ruhanen et al. (Citation2015), which stressed the need for empirical investigations to address the gaps in knowledge and practices in these specific areas. Expanding our knowledge through empirical research will contribute to the sustainable development and effective management of CBT initiatives in the evolving field.

To enhance research on S-CBT in specific regional orientations, such as the ASEAN region, is through international collaborative research. By leveraging diverse perspectives and expertise, international collaboration can provide a comprehensive understanding of S-CBT practices and challenges in the region. Mixed methods research can be employed to gather both qualitative and quantitative data, allowing for a more nuanced analysis. This approach enables researchers to examine the broader picture of S-CBT in the region, addressing the complexities and interconnections between social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions. Furthermore, such regional research can be compiled into special issues in journals, creating a platform for disseminating knowledge, sharing insights, and fostering further research collaboration among scholars in the emerging field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

Bibliographic data associated with this article can be obtained by sending an email request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alonso-Almeida, M. D. M., Bagur-Femenias, L., Llach, J., & Perramon, J. (2018). Sustainability in small tourist businesses: The link between initiatives and performance. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1066764

- Álvarez-García, J., Durán-Sánchez, A., Río-Rama, D., & De la Cruz, M. (2018). Scientific coverage in community-based tourism: Sustainable tourism and strategy for social development. Sustainability, 10(4), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041158

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Vogt, C. A., & Knopf, R. C. (2007). A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(5), 483–502.

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2016). Asean community based tourism standard. Public Outreach and Civil Society Division.

- Ayuso, S. (2006). Adoption of voluntary environmental tools for sustainable tourism: Analysing the experience of Spanish hotels. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 13(4), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.103

- Bhati, A., Mohammadi, Z., Agarwal, M., Kamble, Z., & Donough-Tan, G. (2022). Post COVID-19: Cautious or courageous travel behaviour? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(6), 581–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2091944

- Blackstock, K. (2005). A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal, 40(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsi005

- Bramwell, B. (1990). Green tourism in the countryside. Tourism Management, 11(4), 358–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(90)90072-H

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the journal of sustainable tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (1993). Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589309450696

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2012). Towards innovation in sustainable tourism research? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.641559

- Brida, J. G., Cortes-Jimenez, I., & Pulina, M. (2016). Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(5), 394–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.868414

- Bui, H. T., Jones, T. E., Weaver, D. B., & Le, A. (2020). The adaptive resilience of living cultural heritage in a tourism destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 1022–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1717503

- Butler, R. W. (2019). Overtourism and the tourism area life cycle. Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions, 1, 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110607369-006

- Calgaro, E., Lloyd, K., & Dominey-Howes, D. (2014). From vulnerability to transformation: A framework for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.826229

- Cánoves, G., Villarino, M., Priestley, G. K., & Blanco, A. (2004). Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 35(6), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.03.005

- Cheer, J. M. (2020). Human flourishing, tourism transformation and COVID-19: A conceptual touchstone. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 514–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1765016

- Cheng, T. M., Wu, H. C., Wang, J. T. M., & Wu, M. R. (2019). Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(14), 1764–1782. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1405383

- Choi, H. C., & Murray, I. (2010). Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903524852

- Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274651

- Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1274–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.018

- Choi, H. C., & Turk, E. S. (2011). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. In M. Budruk & R. Phillips (Eds.), Quality-of-life community indicators for parks, recreation and tourism management (pp. 115–140). Springer.

- Chok, S., Macbeth, J., & Warren, C. (2007). Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: A critical analysis of ‘pro-poor tourism’and implications for sustainability. Current Issues in Tourism, 10(2-3), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit303

- Cohen, E. (2008). The changing faces of contemporary tourism. Society, 45(4), 330–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-008-9108-2

- Correia, A., & Kozak, M. (2022). Past, present and future: Trends in tourism research. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(6), 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1918069

- Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability, 8(5), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

- Dangi, T. B., & Petrick, J. F. (2021). Enhancing the role of tourism governance to improve collaborative participation, responsiveness, representation and inclusion for sustainable community-based tourism: A case study. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(4), 1029–1048. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-10-2020-0223

- Dodds, R., Ali, A., & Galaski, K. (2018). Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(13), 1547–1568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1150257

- Dwyer, L. (2005). Relevance of triple bottom line reporting to achievement of sustainable tourism: A scoping study. Tourism Review International, 9(1), 79–938. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427205774791726

- Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G. A., & Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, web of science, and Google scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal, 22(2), 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF

- Frochot, I. (2005). A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: A Scottish perspective. Tourism Management, 26(3), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.016

- Gao, C., Cheng, L., Iqbal, J., & Cheng, D. (2019). An integrated rural development mode based on a tourism-oriented approach: Exploring the beautiful village project in China. Sustainability, 11(14), 3890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143890

- Garrod, B., Wornell, R., & Youell, R. (2006). Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. Journal of Rural Studies, 22(1), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.001

- Graciano, P. F., & Holanda, L. A. D. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of scientific literature on community-based tourism from 2013 to 2018. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 14(1), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.7784/rbtur.v14i1.1736

- Hall, C. M., & Page, S. J. (2014). The geography of tourism and recreation: Environment, place and space. Routledge.

- Hallinger, P., & Kovačević, J. (2022). Mapping the intellectual lineage of educational management, administration and leadership, 1972-2020. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(2), 192–216.

- Hsu, C. H., Lin, H. H., & Jhang, S. (2020). Sustainable tourism development in protected areas of rivers and water sources: A case study of Jiuqu Stream in China. Sustainability, 12(13), 5262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135262

- Jaafar, M., Md Noor, S., Mohamad, D., Jalali, A., & Hashim, J. B. (2020). Motivational factors impacting rural community participation in community-based tourism enterprise in Lenggong Valley, Malaysia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(7), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1769696

- Jamal, T. B., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Johnston, R. J., & Tyrrell, T. J. (2005). A dynamic model of sustainable tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 44(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505278987

- Joo, J., Choi, J. J., & Kim, N. (2019). Examining roles of tour Dure producers for social capital and innovativeness in community-based tourism. Sustainability, 11(19), 5337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195337

- Joppe, M. (1996). Sustainable community tourism development revisited. Tourism Management, 17(7), 475–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00065-9

- Kajanus, M., Kangas, J., & Kurttila, M. (2004). The use of value focused thinking and the A’WOT hybrid method in tourism management. Tourism Management, 25(4), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00120-1

- Kamata, H. (2022). Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1881452

- Kastenholz, E., Carneiro, M. J., Marques, C. P., & Lima, J. (2012). Understanding and managing the rural tourism experience—The case of a historical village in Portugal. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.08.009

- Kim, S., & Kang, Y. (2020). Why do residents in an overtourism destination develop anti-tourist attitudes? An exploration of residents’ experience through the lens of the community-based tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(8), 858–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1768129

- Komppula, R. (2014). The role of individual entrepreneurs in the development of competitiveness for a rural tourism destination–A case study. Tourism Management, 40, 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.007

- Kunjuraman, V. (2023). A revised sustainable livelihood framework for community-based tourism projects in developing countries. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(4), 540–546.

- Lane, B. (1994a). Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1-2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510687

- Lane, B. (1994b). What is rural tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1-2), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510680

- Lane, B. (2018). Will sustainable tourism research be sustainable in the future? An opinion piece. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.12.001

- Lane, B., & Kastenholz, E. (2015). Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches–towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8-9), 1133–1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1083997

- Lasso, A., & Dahles, H. (2018). Are tourism livelihoods sustainable? Tourism development and economic transformation on Komodo Island, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(5), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1467939

- Lee, N., Lee, S., & Lee, T. J. (2022). Resident reactions to a pandemic: the impact on community-based tourism from social representation perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(9), 967–985.

- Lee, T. H. (2011). How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(7), 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.570345

- Lee, T. H., & Jan, F. H. (2019). Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tourism Management, 70, 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.003

- Leksakundilok, A., & Hirsch, P. (2008). Community-based ecotourism in Thailand. In J. Connell & B. Rugendyke (Eds.), Tourism at the grassroots: Villagers and visitors in the Asia-Pacific (pp. 214–235). Routledge.

- Lew, A. A. (2014). Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864325

- Liu, A., & Wall, G. (2006). Planning tourism employment: A developing country perspective. Tourism Management, 27(1), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.08.004

- Lopes, A. S., Sargento, A., & Carreira, P. (2021). Vulnerability to COVID-19 unemployment in the Portuguese tourism and hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1850–1869.

- Manyara, G., & Jones, E. (2007). Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 628–644. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost723.0

- Mbaiwa, J. E., & Stronza, A. L. (2010). The effects of tourism development on rural livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(5), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653500

- Mccool, S., Butler, R., Buckley, R., Weaver, D., & Wheeller, B. (2013). Is concept of sustainability utopian: Ideally perfect but impracticable? Tourism Recreation Research, 38(2), 213–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2013.11081746

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Mondal, M., & Haque, S. (2017). SWOT analysis and strategies to develop sustainable tourism in Bangladesh. UTMS Journal of Economics, 8(2), 159–167.

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Moscardo, G., Pearce, P., Green, D., & O'Leary, J. T. (2001). Understanding coastal and marine tourism demand from three European markets: Implications for the future of ecotourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(3), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580108667399

- Mowforth, M., & Munt, I. (2015). Tourism and sustainability: Development, globalisation and new tourism in the third world. Routledge.

- Moyle, B., Moyle, C. L., Ruhanen, L., Weaver, D., & Hadinejad, A. (2020). Are we really progressing sustainable tourism research? A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1817048

- Mtapuri, O., & Giampiccoli, A. (2019). Tourism, community-based tourism and ecotourism: A definitional problematic. South African Geographical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Geografiese Tydskrif, 101(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2018.1522598

- Murphy, P. E. (1988). Community driven tourism planning. Tourism Management, 9(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(88)90019-2

- Nguyen, D. T. N., d’ Hauteserre, A. M., & Serrao-Neumann, S. (2022). Intrinsic barriers to and opportunities for community empowerment in community-based tourism development in Thai Nguyen province, Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 723–741.

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.006

- OECD. (2018). Multi-dimensional review of Thailand: Volume 1. Initial assessment, OECD development pathways. OECD Publishing.

- Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

- Palacios-Florencio, B., Santos-Roldán, L., Berbel-Pineda, J. M., & Castillo-Canalejo, A. M. (2021). Sustainable tourism as a driving force of the tourism industry in a post-COVID-19 scenario. Social Indicators Research, 158(3), 991–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02735-2