ABSTRACT

Local authorities in Palestine are the service providers for solid waste management. Given that the organic fraction is the largest in municipal solid waste, and with ineffective management policies, the study of attitudes and behavioral aspects of personnel involved are very-important parameters in developing an effective waste management system and assisting policymakers in rectifying these policies. This study aims to assess the attitude of local authorities (LAs) in the southern West Bank of Palestine towards organic municipal solid waste composting and the factors that affect their attitude. The data was gathered via a structured questionnaire from all local authorities in the study area. The results showed that the local authorities’ attitude toward organic solid waste composting is low and can be considered dissatisfactory since only 36.5% of the local authorities are planning for composting compared to 63.5% who are not. The results also showed that municipal solid waste composting is significantly affected by nine factors, including financial capacity, proper machinery, enough refuse collection vehicles to collect solid waste fractions separately, availability of area of land to be used for composting, familiarity with composting systems, staff previous-experience in compost production, acceptance of the rapid composting system, staff training in compost production, and believe that solid waste composting is within the LAs’ responsibility.

Implications: The generation of municipal solid waste is growing continuously due to the population growth leading to increased methane emissions, adding more pressure on the landfills which are facing political and social restrictions for expansion in Palestine. In addition, there are severe restrictions imposed on the import of chemical fertilizers. Therefore, composting the organic fractions of solid waste can, to a large extent, extend the life of the landfills and compensate for the shortage of fertilizers in the market. Moreover, it will encourage organic farming and reduce methane emissions as well. Further, it can contribute to achieve the objective of the national strategy on solid waste management.

Introduction

Urbanization and population growth have led to increased municipal solid waste (MSW) generation. The annual MSW quantity generated in Palestine (West Bank and Gaza Strip) during 2018 was about 1.59 million tons (CESVI Citation2019). In the Southern part of the West Bank (the study area), the annual MSW production is around 0.34 million tons, as per the records of the weighing bridge of the Joint Service Council for Solid Waste Management for Hebron and Bethlehem governorates (JSC-H&B Citation2020). A previous study has identified the organic fraction of MSW is 46% of the total waste stream by the International Finance Corporation (IFC Citation2012). This waste stream is collected mixed (organic and inorganic) and disposed of in a regional sanitary landfill. As the sanitary landfill lacks a gas collection system, this waste stream undergoes anaerobic digestion causing releases of methane gas into the atmosphere, thus contributing to global warming and climate change. The estimated contribution of the solid waste (SW) sector is 23% of the total emissions in Palestine, as per a study conducted by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP Citation2016). Therefore, the diversion of the organic materials and composting of the such waste stream can, to a large extent, reduce methane emissions and environmental pollution well as.

In Palestine, compost is still implementing on a pilot scale. Some of the previous attempts at compost production were not fully-successful. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) supported a household compost program in the West Bank, and part of the program was implemented in the study area (Al-Walajah village/Bethlehem governorate). About 90 household composters were distributed, out of the 150 planned. However, only 60 out of 90 were found in use, during the monitoring of the program, which reflects the relatively low interest in household composting (JICA Citation2019). Another central pilot composting (windrow and pile systems) was conducted in the study area by the JSC-H&B in partnership with Rostock University – Germany, and Al-Jaar Engineering Establishment – Jordan, on municipal organic solid waste generated from the central market of fruit and vegetables in the city of Hebron, and mixed with fresh manure from animal and poultry farms. This pilot succeeded in producing good-quality compost (Al-Sari’ Citation2019).

Apart from technical inputs for organic waste composting, attitudes and behavioral aspects are essential parameters in the sustainability of any waste management system, including composting program. Ulhasanah and Goto (Citation2018) reported that attaining an integrated MSW management begins with identifying people’s attitudes, social norms, and behavioral intentions. Among the most relevant stakeholders in this respect are the SWM service providers, the waste producers, and the farmers. In Palestine in general and the study area in particular, local authorities (LAs), including, municipalities; village councils; joint councils for services, planning, and development (JCSPDs); and joint service councils for solid waste management (JSCs-SWM) are the service providers of MSW, and fully responsible for SWM including composting of the organic waste fraction. Citizens are the waste producers, and their participation could be through waste sorting at the source. To close the loop, farmers are supposed to use the compost produced from organic waste.

The attitude of some stakeholders toward SWM in Palestine, including compost production and use, and the factors affecting their attitudes, were studied by previous research. For example, Al-Khateeb et al. (Citation2017) studied the factors affecting the sustainability of the SWM system in two Palestinian cities, Ramallah and Jericho. Al-Sari’, Sarhan, and Al-Khatib (Citation2018) have studied the farmers’ attitudes toward compost use in agriculture and the factors affecting their attitudes in the Hebron area. Al-Madbouh et al. (Citation2019) have studied the socioeconomic, agricultural, and individual factors influencing farmers’ perceptions and willingness for compost production and its use in Wadi al-Far’a Watershed, Palestine. On the contrary, the attitude of local authorities, the key stakeholders in SWM, toward composting has never been studied previously. Therefore, this study focuses on the assessment of the LAs’ attitude toward MSW composting and the factors influencing their attitudes in the southern West Bank of Palestine.

Attitudes toward SW composting

“Attitude is a feeling about something or the way of thinking in cooperative or uncooperative behavior” (Petty and Krosnick Citation2014; Swesi, Mallak, and Tendulkar Citation2019), and an individual can frame his attitude based on beliefs and perception. The organization’s efficiency depends on the attitude of its management and staff, where the top management draws the strategy, and the staff members translate it into actions, thus, determining the organization’s behavior. Changing the attitude of the management and employees creates a change in the organization’s attitude and behavior. Nafei (Citation2014) reported that the capabilities of managers, employees, and the work environment are examined by the organizational change that affects the employees’ attitude and behavior by turning a situation from the known to the unknown. This interrelationship exists in the LAs, the key stakeholders in SW management, and could change the LAs’ attitude toward SW management options. These LAs play a crucial role in MSW management by applying the waste management principles of reducing, reusing, and recycling (3Rs) (Seah and Addo-Fordwuor Citation2021) if they have the resources and positive attitudes. They can also play a definitive role in determining the country’s strategy and translating it, in reality, into action.

The National Strategy for Solid Waste Management in Palestine (NSSWM 2017–2022) set eight strategic objectives to achieve its vision in solid waste management and focused on organizational, technical, and financial issues. Strategic objective 3 of “effective and environmentally-safe SW service”, and policy 6 of “Encouraging the policies and methods of SW reduction, recycling, reusing, and regenerating before final disposal at regional sanitary landfills” (NSSWM Citation2017), are encouraging organizations for private sector investment in reuse and recycling of SW to reduce the quantities that are currently sent for landfilling. One of the recycling options mentioned under this strategic objective is composting organic SW materials to be used as compost or as cover material in sanitary landfills. From a strategic point of view, the local authorities are the key players who can create real change through direct investment or attracting investors for this sector. The attitude of these authorities toward SW recycling through composting is essential and can indicate their future direction and steps toward a new composting system.

It has been reported that success in solid waste management depends on the extent to which stakeholders are integrated into the management process, thus harnessing their respective resources to build collective strength with a clear division of roles and responsibilities (Klundert and Anschütz Citation2001; Phong Le, Nguyen, and Zhu Citation2018). Joseph (Citation2006) has discussed and defined the rule of the different stakeholders, including municipalities, in sustainable solid waste management. Phong Le, Nguyen, and Zhu (Citation2018) investigated the stakeholders’ perspectives on utilizing organic municipal solid waste in agriculture, indicating that the attitude and behavior of stakeholders are significant elements for the success of composting organic waste and its subsequent use.

Factors affecting local authorities’ attitude toward SW composting

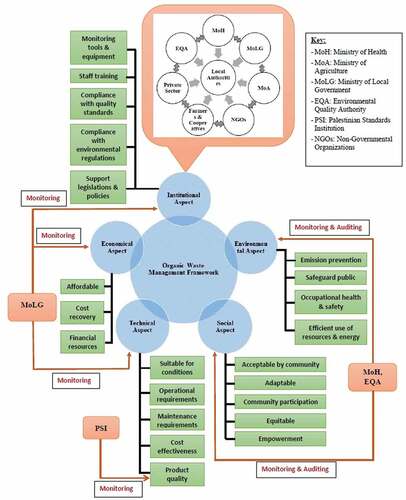

The attitude of the local authorities toward composting could be affected by several factors similar to other waste recycling programs. Past research on challenges and constraints faced by the waste management (WM) organization highlighted that financial, technical, awareness, and institutional constraints, are dominantly responsible. McAllister (Citation2015) studied the factors influencing SWM in the developing world and classified the factors into culture and education, infrastructure and technology, policy and institutional, and integrated SWM system. Since municipalities in developing countries are providing SWM service, they are responsible for providing the required infrastructure for waste collection, transport, treatment, and disposal, and the system often fails to manage the waste due to various social, institutional, and technical constraints (McAllister Citation2015). Nitivattananon and Suttibak (Citation2008) assessed the factors that affect the performance of SW recycling programs and classified them into general factors such as awareness, technical, financial, and institutional. Lalitha and Fernando (Citation2019) reported the factors that affect SWM in Sri Lanka. These included citizens’ participation, adequacy of resources, awareness and training, availability of market for compost and other recyclables, awareness of the national policy and laws related to SWM, developing innovative methods for SWM, support from the political leadership, the contribution of the society and business community, and remuneration and other facilities to the staff for successful implementation of the solid waste management program. Phong Le, Nguyen, and Zhu (Citation2018) reported that the stakeholders influence various SWM system elements, including composting, through environmental, financial, institutional, legal, and social aspects. Raza and Ahmad (Citation2016) reported that a lack of political, legal, and regulatory environment could derail composting efforts. He also mentioned that since composting is a multi-sectoral issue, the municipality’s priority outcomes should be accounted-for early in the dialogue, and the related policies, should be aligned appropriately. Based on the review of the literature and the situation of the local authorities in the study area, a system approach for organic waste management is suggested as depicted in

The implementation of the proposed SWM framework requires cooperation between all of the stakeholders involved in SWM. By the proposed framework, the stakeholders’ organizations include the LAs that will carry out composting of the organic waste; farmers who will use the compost in agriculture; the Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), which will conduct monitoring on technical, institutional, and economic aspects; the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), which is the regulator of the agricultural sector and can play a crucial role in compost utilization for agriculture; Environmental Quality Authority (EQA) and the Ministry of Health (MoH), which can conduct monitoring on environmental, social and safeguard of the workers and the public community; non-governmental organizations, which can conduct awareness in the community and promote the culture of composting; and the private sector, which can take part in solid waste collection, transport, and composting as well. The framework of Waste Management should be compatible with the waste management strategy to achieve its objectives and could include strategic initiatives to reduce the pressure on the environment. The use of waste recycling options such as composting and change of attitude and behavior are examples of these strategic initiatives (Zorpas Citation2019, Citation2020). In addition, identifying the constraints and risks and overcoming them, can contribute to the successful implementation of the proposed waste management framework. For the study area, a SWOT analysis matrix is prepared to explore strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats as presented in

Figure 2. SWOT analysis to explore strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in the study area.

As the purpose of this paper is to identify the factors that affect the attitude of the LAs toward composting, which is considered the main constraint toward successful implementation of composting program, the following factors are identified to include in the study for successful implementation of composting program:

Community participation

Community participation in the waste recycling programs is essential, especially if the local authority plans to apply the role of waste segregation at the source, which is the key element in the successful implementation of the waste recycling program as it reduces the time, effort, and cost. Shukor et al. (Citation2011) reported that the residents are responsible as users, and their minimum input and participation are required to separate recyclable and organic materials from the other waste. Community participation can contribute to the success of SWM programs and is a crucial factor in the effective implementation of SWM (Rathi Citation2006). Further, community awareness regarding organic waste separation and composting is essential and can facilitate participation in waste segregation at the source. Planning for composting is necessary for community participation as the lack of suitable areas for composting was identified as a reason for disagreeing to participate in home composting (Ridzuan et al. Citation2012). The motivation of the community to participate in organic waste composting can be achieved in several ways, including, but not limited to, providing free compost bins (NC State Extension Citation2022), and tax waste discounts (Francesco Storino et al. Citation2018). Mangundu et al. (Citation2013) raised the importance of community awareness and promotion regarding the use of compost through road shows, radio, and TV programs, which should follow the education on policies and implications regarding violation of bylaws. In the study area, measures for composting on the household level are absent, although pilot measures’, were implemented through the free distribution of home composters (JICA Citation2019). Concerning central composting, there is a waste sorting facility, but composting is still conducted on a pilot scale.

Availability of resources

The availability of adequate resources is essential to implement the SWM program. Resources include financial, technological, land, and infrastructure, which are necessary for the local authorities to initiate and sustain the WM system. Malwana (Citation2008) reported that many local governments pay scant attention to the infrastructure for waste collection and disposal because of the limited budget allocated to them by the central government. Previous studies highlighted the importance of adequate resources in the success of WM. Henry, Yongsheng, and Jun (Citation2006) identified that a lack of SW collection vehicles, poor infrastructure, and a lack of financial resources with local government units reduced the level of success of SWM projects. Atienza (Citation2011) reported that developing countries are more affected than developed countries due to the lack of financial resources to purchase and employ modern technologies in SWM. A study carried out in Sri Lanka reported that limited land available was a vital issue faced by the local government units in conducting their recycling and composting programs (Lalitha and Fernando Citation2019). The study also found that the vast majority of the local authorities engaged in composting activities have failed because of the lack of necessary facilities and the latest technology. The main-financial resource contributing to SWM at the level of local authorities is the fees collected from the community on a monthly or annual basis. The rate of fees-collection is an indicator of the financial status of the local authority and could affect its attitude toward initiating a new composting facility. Another important financial-indicator is the cost-to-billing ratio which indicates if the tariff is adequate in covering the cost of the SWM service and could also affect the local authority toward alternative methods in SWM.

Employees’ awareness and training

The awareness and training received by the local staff on compost production could accelerate and speed up the rate of organic waste processing and improve the quality of compost production. Training of the local staff shall include training on the collection, recycling, and composting of SW (Lalitha and Fernando Citation2019). The LAs’ employees’ knowledge and experience in compost production can affect the LAs’ attitude toward composting. Previous studies reported human factors, including previous work experience and personal perception factors, affecting the adoption of compost in organic waste management (Vigoroso et al. Citation2021).

Marketing

Composting of organic municipal SW generates compost, and proper marketing is essential to generate revenues to cover the cost of production. Marketing of compost can generate a financial resource that contributes to SWM. Bandara (Citation2008) reported that the reason behind the failure of composting programs is not only operational failure but also the lack of marketing, which discourages the large-scale production of compost, and compost quality is a cornerstone in marketing. Pergola et al. (Citation2018) have also reported that compost quality plays a critical role in its marketing and encourages farmers to use it in agriculture. The World Bank (Citation2016) reported the marketing risks of compost; when lacking market demand, product sales do not generate enough revenues to sustain the operation of the composting facility. Rouse, Rothenberger, and Zurbrügg (Citation2008) also reported that marketing compost at a price and in sufficient quantity is essential to ensure the successful of the business. Moreover, a lack of market demand was identified as one of the barriers to the adoption of composting (Iacovidou and Zorpas Citation2022). Therefore, compost marketing can be considered one of the factors affecting attitude toward organic waste composting.

Support from the government

Support from the government could be financial, technical, or political. Direct finance contribution from the government to solid SWM or through tax exemption (World Bank Citation2016) or other incentives on compost produced from the organic fraction of municipal SW can significantly solve many waste management problems and can encourage local authorities to look for composting of the organic SW. In addition, this will promote the public-private partnership in SWM. Technical contributions from the government can take several forms, for example, establishing regional composting plants, providing the local authorities with bins for waste sorting, providing the local authorities with the required machines and collection vehicles, etc. Political support is through issuing/enforcing the policies and regulations of SWM, which can support the local authorities to seek alternative solutions in WM. Political support is considered one of the compulsory elements to achieve a radical SWM system (Gustavson Citation2008). Another remarkable intervention and support from the government are directing international donors to support the local authorities in the field of SWM, including the recycling and composting programs.

National policy and laws related to organic waste composting

Policies and roles can support local authorities to develop WM practices and move to better environment-friendly systems. Waste separation at the source and waste reduction through waste composting can ensure cooperation between the community and the service provider to establish composting programs. Previous studies (Mangundu et al. Citation2013; Taylor Citation2000) also highlighted the importance of well-established SWM policies for successful implementation.

InnovatIon on solid waste management

One of the challenges in SW composting using turned windrow or pile composting is the long time needed (5–10 weeks) for processing (FAO Citation2007) in addition to maturation time before use, which requires a large area of land to operate (World Bank Citation2016). Therefore, developing a new rapid composting system with acceptable operation cost, which can reduce the area and time needed, is considered a novel method and could change the attitude of these local authorities toward composting.

Now, considering that composting of organic fraction of municipal solid waste can significantly reduce the load over the waste management system and landfills, and the attitude of the local authorities can affect the successful implementation of a new composting plant, the present study was undertaken to determine the attitude of the local authorities of Palestine toward adapting composting, and to understand the role of different factors toward determining their attitude and support for composting of municipal organic waste. For this research, two hypotheses are assumed: (1) the attitude of the LAs toward organic solid waste composting is negative, and (2) several factors, including technical, financial, institutional, environmental, and social, can negatively affect the attitude of the LAs toward composting. The study focuses on the southern part of the West Bank (Hebron & Bethlehem governorates) as this is the highest densely populated area in Palestine and generates large quantities of MSW.

Research methods

The study aims to evaluate the local authorities (LA) attitudes toward organic SWM in the southern West Bank (Hebron & Bethlehem governorates/Palestine. Perception of the LAs toward organic SWM was evaluated through data collection via a survey questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed depending on the literature and included information about the solid waste service provider, solid waste generated, knowledge and awareness of composting and waste management legislations, tariff and fee collection, financial and technical capacity to conduct composting, and challenges faced by the service provider in composting the organic fraction of the solid waste. The information included in the questionnaire covered the technical, financial, environmental, institutional, and social sides. The questionnaire was peer-reviewed by two Professors in environmental engineering from India and Palestine. Peer reviewing was conducted before data collection to ensure the adequacy of the questionnaire for the study.

The target group for collecting the responses was the local authorities in the southern West Bank/Palestine, which include municipalities, VCs, JCSPDs, and JSCs-SWM, who are providing the SWM service. The list of the LAs was obtained from the Ministry of Local Government – MoLG (MoLG Citation2021). Following the list, there are 89 municipalities and VCs, 3 JSCs-SWM, and 6 JCSPDs, but only 3 of them are providing SWM service. The JCSPDs that are not providing SWM service are excluded from the study. In addition, 9 of the remote communities were found not served, and the VCs in these communities are not providing the SWM service. Such VCs, are excluded from the data collection via questionnaire, but general information about current practices of organic waste management, was obtained. A total of 85 LAs are included in the data collection using the questionnaire. Because the research population is limited, all of the population is considered as a sample, and the data is collected from all.

The questionnaires were filled through direct interviews, where possible, via e-mail and over the phone. The interviewees were the key-staff members, such as the heads of the SWM division or the managers of the LAs. For a few instances, the finance managers participated partially in the survey to answer the questions related to the waste quantities and cost as directed by the LA officials. Ethical issues were fully considered such as confidentiality through excluding the names of the LAs and the persons who participated, and informed consent as all of the LAs were informed about the purpose of the survey and obtained their agreement before filling out the survey questionnaire. After the completion of the data collection, the questionnaires were coded, and the data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences software (SPSS) version 23.

Results and discussion

Description of the LAs

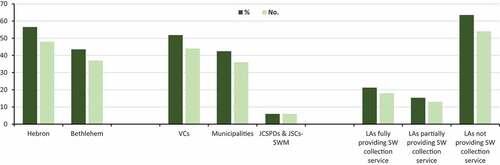

It has been found that 56.5% of the LAs (48 LAs) are located in the Hebron governorate and 43.5% (37 LAs) are located in the Bethlehem governorate. The largest portion is the VCs which represent 51.8% (44 VCs), followed by the municipalities which represent 42.4% (36 municipalities), and then the joint services councils (JSCs), including the JSC-SWM and JCSPD, which represent 5.9% (5 JSC-SWM and JCSPD) of the total LAs in the study area.

LAs are the service providers for street sweeping, waste collection, and disposal. The LAs, in cooperation with the MoLG, have established the JSCs-SWM and JCSPDs to optimize the SW collection and disposal. The JCSPDs were established in the rural areas where several villages cooperated to establish these councils to optimize the services provided, while the JSCs-SWM were established on the governorate level to handle the SW collection, transfer, and disposal services. However, the councils are not fully functioning in all of the governorates because contracting the service is optional, therefore, there are still several local authorities providing the SWM service. However, it has been found that 21.2% of the LAs (18 LAs) are fully providing the SW collection service, 15.3% of them are providing the collection service in part (13 LAs), and 63.5% are not providing the collection service (54 LAs). LAs providing the SW collection service in part don’t have enough refuse collection vehicles to handle all the waste stream, therefore, it contracts part of the service to the JSC-SWM. However, LAs not providing the collection service are normally small-sized and mostly VCs, which can’t carry out the collection service. Therefore, these LAs contract the SW collection service to the JCSPD or the JSC-SWM. summarizes the LAs’ description.

Attitudes toward municipal organic SW composting

Attitudes of LAs toward applying SW separation at the source and composting of organic municipal SW are almost similar and low. The results revealed that only 36.9% of the LAs (31 LAs) are planning to apply separation at the source compared to 63.1% of them (53 LAs) who are not, and only 36.5% of them (31 LAs) are planning to compost the organic fraction of municipal SW compared to 63.5% (54 LAs) which are not planning for that.

Factors affecting LAs’ attitude toward municipal organic SW composting

The bivariate analysis is used to assess the relationship between two variables, and examine the effect of each influencing factor independently. The findings of the bivariate analysis are presented in . The analysis of the results of these factors is described as follows.

Table 1. Economic and environmental factors and their role in determining the attitude of LAs toward composting of organic SW in the study area.

Table 2. Role of resources, technical and technological factors toward shaping the LAs’ attitudes toward organic SW composting.

Table 3. Role of innovation, marketing, institutional and social factor in shaping the attitude of LAs toward organic SW composting.

Financial factors

Several factors were selected to investigate their influence in shaping the LAs’ attitude toward composting of organic waste as presented in . Only one factor showed a significant relationship with the LAs’ attitude, which is “having the financial capacity to conduct composting” (with P-value = .012). Financial capacity is one of the key elements in the initiation and successful implementation of any project. It has been found that 50.0% of the LAs have the financial capacity to conduct composting but are not planning compared to 41.7% and 75.5% of them which have limited capacity, and haven’t financial capacity, respectively, and are not planning for composting.

Other financial factors are of less importance because it is not significant in shaping the LAs’ attitude toward composting. The debt on the LA is not of significant effect (P-value = .459), where 66.1% of the LAs having debts are not planning for composting compared to 57.1% of them which have no debts. The monthly cost of the SW disposal factor (P-value = .056) hasn’t provided a specific relationship with the planning for composting. It showed that majority of the LAs that pay in the range of NIS 5,000.0 - NIS 30,000.0/month for waste disposal are also not planning to for composting (USD 1= NIS 3.3237; Currency exchange based on Currency Citation2022). Household tariff factor (P-value = .110) showed that 84.2% of the LAs which have a tariff system in the range of NIS 21 – 30/household/month are not planning for composting. Similarly, 60.0% and 50.0% of which have tariff systems in the range of NIS 10–20 and NIS 2 – 3/capita/month, respectively, have no plan for composting. The fee collection rate is one of the most important elements in SWM because it enables the LA to cover the costs associated with waste collection, transport, and disposal, and the financial capacity of the LA increases with the increase of the fee collection rate. User fees are the most appropriate revenue source for the LAs, which can be amenable to cover the cost of services (UN-Habitat Citation2015). The fee collection rate factor (P-value = .18) didn’t provide a clear relationship with the planning for composting. About 62.5% of the LAs, which have a collection rate of ≤20%, haven’t planned for composting, 40.0% of the LAs, which have a fee collection rate in the range of 21–40%, are not planning for composting, and similarly, 57.1% of them, which have fee collection rate in the rage of 61–60%, and are also not planning for composting. Finally, the factor of receiving financial support from the government to develop waste reduction through composting (P-value = .565) showed that 50.0% of the LAs, which “sometimes” received financial support from the government, are not planning for composting compared to 64.2% of them, which haven’t received any financial support from the government. Al-Khatib et al. (Citation2010) reported that support from the government budget is limited, which limits the opportunities for the development of the SWM system.

Environmental factors

Perception of the “impact on the environment” could be one of the driving forces behind a positive attitude toward organic SW composting. Two variables were set to measure the effect of the environmental factors on the LAs’ attitude toward SW composting, as presented in . The data analysis revealed that none of the factors is significant in shaping the LAs’ attitudes. About 61.3% of the LAs, which perceive that compost can contribute to the reduction of environmental pollution (P-value = .117), haven’t planned for composting compared to 100.0% of the LAs that lack this perception. In addition, 61.1% of the LAs, which have the perception of compost contribution to SW reduction (P-value = .197) haven’t planned for composting against 71.4% and 100.0% of the LAs, which don’t know and haven’t perceived this, respectively, have also not planned for organic SW composting. As reported by Aini et al. (Citation2002), the attitude toward SW recycling, including organic SW recycling through composting, was found positively affected by the knowledge-level of environmental conservation and environmental awareness.

Resources (Technical and technological)

The data analysis showed that 5 out of 7 factors are found significant in shaping the attitude of LAs toward composting of the MSW, as presented in . All of the LAs, which have the proper machinery to conduct composting (P-value = .007), is planning for waste composting compared to 66.7% of them, which don’t have the proper machinery and haven’t planned for composting. Lack of machinery could be the reason behind the absence of planning for composting. In addition, 100.0% of the LAs, which have enough RCVs to collect SW fractions separately (P-value = .006), are planning for composting compared to 67.5% of them with a limited number of RCVs not planning for composting, so the availability of RCVs increases positive attitude toward composting. Lalitha and Fernando (Citation2019) reported that most of the LAs lack a sufficient number of waste collection vehicles and the available vehicles are old and broken. The factor of “having an appropriate area of land to be used for composting”, such as the construction of composting plant, (P-value = .001), showed that 42.9% of the LAs that owned appropriate land area had no plan for composting compared to 78.0% of them, which have no appropriate area of land, which means that the unavailability of the land reduces positive attitude toward composting. The limitation of land, was found, to be a major issue faced by the LAs for composting (Lalitha and Fernando Citation2019). Land availability was also identified as a potential barrier to the successful implementation of the recycling strategy (Troschinetz and Mihelcic Citation2009). Moreover, 42.3% of the LAs that are familiar with the composting system (P-value = .007) are not planning to compost organic waste compared to 72.9% of them who are not familiar with composting systems (absence of knowledge of composting reduces attitude toward composting). Further, 40.0% of the LAs, which have staff members with previous experience in compost production (P-value = .037), are not planning for composting of the SW compared to 68.6% that lack previous experience. A high portion of LAs, with staff lacking previous experience, reduces positive attitudes toward composting. Staff experience, in general, affects the LAs’ performance. Tembo et al. (Citation2020) reported that inadequate qualification of manpower affects the LAs’ service delivery.

On the other hand, 2 out of the 7 factors are not significant in determining the LAs’ attitude toward organic SW composting. The factor of having enough financial resources to employ modern technology in SW composting (P-value = .714) showed that 57.1% of the LAs, which have financial resources, are not planning for composting compared to 64.1% with no financial resources for this purpose. Although the availability of financial resources to employ modern technology in composting was found insignificant, the absence of proper technology to apply was found the main factor behind the failure of LAs’ composting programs (Lalitha and Fernando Citation2019). Iacovidou and Zorpas (Citation2022) reported that the quality of compost depends on the composting technology employed, and therefore, the compost quality, can be improved with the adoption of the appropriate technology. The monthly SW quantity generated (P-value = .633) didn’t show a specific relationship with the attitude toward composting. For example, 60.0%, 64.7%, and 60.0% of the LAs, which produce monthly quantities of SW of ≤ 20 tons, 21–50 tons, and 51–100 tons, respectively, are not planning for composting. So the size of the SW quantity produced didn’t provide any specific relation regarding planning for composting or organic waste.

Innovation

Developing novel methods are necessary to manage solid waste (Lalitha and Fernando (Citation2019). The development of a new rapid composting system, which can optimize the compost parameters and reduce the time required for composting, is a novel system and can attract the interest of organizations and companies working on compost production. The LAs were asked whether they could accept the use of a new rapid composting system if developed, and the result showed a significant relationship (P-value = .036) with LAs’ attitude toward composting, as presented in , about 60.3% of the LAs that accept the use of the new developed composting system haven’t planned for composting compared to 100.0% of them which declined to use it. This indicates that the attitude toward composting is negative for LAs who rejected the new rapid composting system.

Marketing

Marketing of compost is essential as the revenues from the sale can ensure cost recovery and support the sustainability of the composting program as well. Lalitha and Fernando (Citation2019) reported that most of the LAs engaged in composting programs have failed, and the main reason for failure was marketing. The influence of marketing on the LAs’ attitude toward composting is measured and found insignificant in shaping the LAs’ attitude (P-value = .294), as shown in . The results showed that 58.6% of the LAs, which believe in good marketing for the compost produced from municipal SW in Palestine, are not planning for composting. Marketing of compost depends on the quality, as well as, the willingness and acceptance of the farmers. The Palestinian farmers’ attitudes and acceptance toward the use of compost in agriculture were found positive, as per the findings of Al-Sari’, Sarhan, and Al-Khatib (Citation2018) and Al-Madbouh et al. (Citation2019). It has been reported that the lack of confidence in the production of good quality compost and its market uptake appears to be a barrier to the adoption of composting in waste management (Iacovidou and Zorpas Citation2022).

Institutional

Staff training, familiarity with the laws and policies, and understanding the responsibilities are all considered institutional factors. Three institutional factors were set to test their impact on the LAs’ attitude toward SW composting, as presented in . The results showed that “staff training in compost production” and “SW composting as the responsibility of the LA” have significant relationships with the planning for organic SW composting (P-value = .018 and .005, respectively). The analysis showed that 35.7% of the LAs that have staff members trained in compost production from organic materials lack a plan for composting, while 69% of them are not trained and have no plan as well (LAs with staff trained in compost production have a more positive attitude toward composting). However, 51.0% of the LAs believe that SW composting is within the LA responsibilities and haven’t planned for composting, compared to 80.6% of them, which do not believe that SW composting is within the LA responsibilities and haven’t composting plan. This indicates that LAs that believe they are responsible for SW composting have a more positive attitude toward composting. The “Familiarity with SWM bylaw” factor, was found with an insignificant effect on the LAs’ attitude with P-value = .818, as presented in . The data analysis showed that 62.2% of the LAs, which are familiar with the SWM bylaw, are not planning to compost the organic fraction of MSW since the law doesn’t enforce it over the LAs.

Social

The social acceptance of any program is one of the important sustainability pillars besides the environment and economy. Community awareness about composting, community participation in the composting program through waste segregation at the source, and farmers’ willingness to use compost produced from MSW in agriculture, are all social factors and could affect the LAs’ attitude toward composting of MSW. The effect of these factors is investigated, as shown in , and the results revealed that none of these factors is significant in determining the LA attitude toward composting. The results revealed that 55.6% of the LAs, which have conducted community awareness on organic waste composting, haven’t planned to compost an organic fraction of MSW compared to those that didn’t. Lack of public awareness of the consequences of biowaste mismanagement was found, one of the barriers to adopting composting (Iacovidou and Zorpas Citation2022). In addition, 55.6% of the LAs who believe in citizens’ participation through sorting organic waste at the source when the LA decided to start composting program are planning for composting. Milea (Citation2009) reported that attitude could be affected by various reasons, including lack of public participation, and lack of education and awareness of efficient WM techniques. Moreover, 61.1% of the LAs, which believe in farmers’ acceptance to use the compost produced from MSW in agriculture, haven’t planned for composting. Iacovidou and Zorpas (Citation2022) reported that the LAs in Cyprus used the farmers’ ignorance of the use of compost instead of artificial fertilizers, which is available in the market at low prices, as an excuse for their growing reluctance to invest in separate biowaste collection and composting because they are unable to return a profit via the sale of compost.

Conclusion

The attitude of LAs toward MSW composting is of great importance and can assist in the design of the proper composting program. This study has identified that the LAs’ attitude toward organic MSW composting is significantly affected by nine factors, including financial capacity, proper machinery, enough RCV to collect SW fractions separately, availability of area of land to be used for composting, familiarity with composting systems, staff-previous experience in compost production, acceptance of the rapid composting system, staff training in compost production, and believe that SW composting is within the LA responsibility.

It is highly recommended that before forcing any policy or initiation of the MSW composting program, the LAs, shall be provided with institutional capacity building and financial and technical requirements to support the program’s sustainability. Awareness of the SWM bylaw, staff training on compost production, and community awareness are all essential perquisites for social and institutional capacity-building activities. LAs also shall be equipped with the proper machinery and RCVs to enable composting of MSW. The SWM bylaw shall be upgraded to include targets to ensure LAs adherence through composting the organic waste to meet the specified targets. This shall be associated with a monitoring program by the regulating Ministry to ensure compliance. Finally, financial support is mandatory through direct contribution or attracting investors in the organic MSW composting.

Questionnaire_Modified_Final.docx

Download MS Word (22.2 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors thank the officers and officials of different LAs in Palestine for their responses to the questionnaire survey of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2022.2141919

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Majed Ibrahim Al-Sari’

Majed I. Al-Sari’ Ph.D. scholar in the Department of Environmental Engineering at Delhi Technological University. His research focuses on solid waste management, composting, and urban mining.

A. K. Haritash

A. K. Haritash is a Professor in the Department of Environmental Engineering at Delhi Technological University in Delhi. His area of interest is environmental monitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), water quality assessment, wetland monitoring, waste management, and bioremediation.

References

- Aini, M. S., A. F. Razi, S. M. Lau, and A. H. Hashim. 2002. Practices, attitudes, and motives for domestic waste recycling. Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol. 9 (3):232. doi:10.1080/13504500209470119.

- Al-Khateeb, A. J., M. I. Al-Sari’, I. A. Al-Khatib, and F. Anayah. 2017. Factors affecting the sustainability of solid waste management system—The case of Palestine. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189:93. doi:10.1007/s10661-017-5810-0.

- Al-Khatib, I. A., M. Monou, A. F. Abu Zahra, H. Q. Shaheen, and D. Kassinos. 2010. Solid waste characterization, quantification and management practices in developing countries. A case study: Nablus district – Palestine. J. Environ. Manage. 91 (5):1131–38. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.01.003.

- Al-Madbouh, S., I. A. Al-Khatib, J. I. Salahat, B. Y. A. Jararaa, and L. Ribbe. 2019. Socioeconomic, agricultural, and individual factors influencing farmers’ perceptions and willingness of compost production and use: An evidence from Wadi al-Far’a Watershed-Palestine. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191:191–209. doi:10.1007/s10661-019-7350-2.

- Al-Sari’, M. I. 2019. Pile composting efficiency in organic waste management. In The second international conference on civil engineering (ICCE). Bethlehem, West Bank - Palestine, November 25, 26.

- Al-Sari’, M. I., M. A. A. Sarhan, and I. A. Al-Khatib. 2018. Assessment of compost quality and usage for agricultural use: A case study of Hebron, Palestine. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190:190–223. doi:10.1007/s10661-018-6610-x.

- Atienza, V. 2011. Review of the waste management system in the Philippines: Initiatives to promote waste segregation and recycling through good governance K. a. EconomIc integration and recycling in Asia: An interim report, 65–97. Institute of Developing Economics, Chosakenkyu Hokokusho.

- Bandara, N. (2008). Municipal solid waste management – The Sri Lankan Case. Conference on Development in Forestry and Environment in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka: The University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

- CESVI. 2019. Solid waste management in the Palestinian territory, West Bank including East Jerusalem & Gaza Strip. Overview report.

- Currency. 2022. Your UK Currency and Exchange Rates Resource. Accessed on August 30, 2022. https://www.currency.me.uk/convert/usd/ils.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2007. Waste management opportunities for rural communities: Composting as an effective waste management strategy for farm households and others. Agricultural and Food Engineering Working Document 6. Rome, Italy.

- Francesco Storino, F., R. Plana, M. Usanos, D. Morales, P. M. Aparicio-Tejo, J. Muro, and I. Irigoyen. 2018. Integration of a communal henhouse and community composter to increase motivation in recycling programs: overview of a three-year pilot experience in Noáin (Spain). Sustainability 10 (3):690. doi:10.3390/su10030690.

- Gustavson, A. 2008. Minor Field Study: Implementation of SWM Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu State of India. Master of Science Thesis INDEK 2008:86.

- Henry, R. K., Z. Yongsheng, and D. Jun. 2006. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing countries – Kenyan case study. Waste Manage. 26 (1):92–100. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2005.03.007.

- Iacovidou, E., and A. A. Zorpas. 2022. Exploratory research on the adoption of composting for the management of biowaste in the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Cleaner Circ. Bioecon. 1:100007. doi:10.1016/j.clcb.2022.100007.

- IFC (International Finance Corporation). 2012. Solid waste management in Hebron and Bethlehem Governorates, assessment of current situation, and analysis of new system. Report. Palestine.

- JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency). 2019. Project for Technical Assistance in Solid Waste Management in Palestine. A Technical Cooperation between Palestine and Japan (2015 -2019). Final Report. Palestine.

- The Joint Service Council for Solid Waste Management for Hebron and Bethlehem (JSC-H&B). 2020. Weighting bridge records of solid waste quantities delivered to Al-Menya landfill.

- Joseph, K. 2006. Stakeholder participation for sustainable waste management. Habitat Int 30:863–71. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.09.009.

- Klundert, A. V. D., and J. Anschütz. 2001. Integrated sustainable waste management – the concept. Tools for Decision-makers. Experiences from the Urban Waste Expertise Programme (1995-2001). The Netherlands: WASTE.

- Lalitha, R., and S. Fernando. 2019. Solid waste management of local governments in the Western Province of Sri Lanka: An implementation analysis. Waste Manage. 84:194–203. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2018.11.030.

- Malwana, C. 2008. Solid waste management in Sri Lanka. Econ. Rev. 34 (3&4): 34–37.

- Mangundu, A., E. S. Makura, M. Mangundu, and R. Tapera. 2013. The importance of integrated solid waste management in independent Zimbabwe: The case of Glenview Area 8, Harare. Global J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2 (3):85–92.

- McAllister, J. (2015). Factors influencing SWM in the developing world. All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. Paper 528. Utah State University.

- Milea, A. (2009). Waste as a social dilemma: Issues of social and environmental justice and the role of residents in municipal solid waste management, Delhi, India. Master’s thesis, Lund University. Lund, Sweden.

- MoLG (Ministry of Local Government). 2021. List of local authorities in the West Bank.

- Nafei, W.A. 2014. Assessing employee attitudes towards organizational commitment and change: The case of King Faisal Hospital in Al-Taif Governorate, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Manage. Sustainability 4 (1). Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education. doi:10.5539/jms.v4n1p204.

- NC State Extension. 2022. Community Backyard Composting Programs Can Reduce Waste and Save Money. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/community-backyard-composting-programs-can-reduce-waste-and-save-money.

- Nitivattananon, V., and S. Suttibak. 2008. Assessment of factors influencing the performance of solid waste recycling programs. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 53:45–56. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.09.004.

- NSSWM (National Strategy for Solid Waste Management in Palestine: 2017 - 2022). 2017. The state of Palestine.

- Pergola, M., A. Piccolo, A. M. Palese, C. Ingrao, and G. Celano. 2018. A combined assessment of the energy, economic and environmental issues associated with on-farm manure composting processes: Two case studies in South of Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 172:3969–81. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.111.

- Petty, R. E., and J. A. Krosnick. 2014. Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. New York, USA: Psychology Press.

- Phong Le, N., T. T. P. Nguyen, and D. Zhu. 2018. Understanding the stakeholders’ involvement in utilizing municipal solid waste in agriculture through composting: A case study of Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 10:2314. doi:10.3390/su10072314.

- Rathi, S. 2006. Alternative approaches for better municipal solid waste management in Mumbai, India. Waste Manage. 26 (10):1192–200. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2005.09.006.

- Raza, S., and J. Ahmad. 2016. Composting process: A review. Int. J. Biol. Res. 4 (2):102–04. doi:10.14419/ijbr.v4i2.6354.

- Ridzuan, M. R., M. A. Abas, S. M. Abdul Kadir, S. Sibly, and N. M. Nor. 2012. Empowering community via composting practices in promoting sustainable lifestyle. In Proceeding of University-Community Engagement Conference: University-Community Engagement for Empowerment and Knowledge Creation (UCEC 2012), Le Meridien Chiangmai, Thailand, January 9–12.

- Rouse, J., S. Rothenberger, and C. Zurbrügg. 2008. Marketing compost: A guide for compost producers in low and middle-income countries. Eawag, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

- Seah, S., and D. Addo-Fordwuor. 2021. Roles and strategies of the local government in municipal solid waste management in Ghana: Implications for environmental sustainability. World Environment 11 (1):26–39.

- Shukor, F. A., A. H. Mohammed, S. I. Sani, and M. Awang. (2011). A review of the success factors for community participation in solid waste management. In International Conference on Management Proceedings, Penang, Malaysia, 963–76.

- Swesi, A. E. M., S. K. Mallak, and A. Tendulkar. 2019. Community attitude, perception, and willingness toward solid waste management in Malaysia, Case study. J. Wastes Biomass Manage. 1 (1):09–14. doi:10.26480/jwbm.01.2019.09.14.

- Taylor, D. C. 2000. Policy incentives to minimize generation of municipal solid waste. Waste Manage. Res. 18 (5):406–19. doi:10.1177/0734242X0001800502.

- Tembo, M., E. M. Mwanaumo, S. Chisumbe, and A. O. Aiyetan. 2020. Factors affecting effective infrastructure service delivery in Zambia’s local authorities: A case of Eastern Province. Supporting Inclusive Growth Sustainable Dev. Afr. 2:65–81.

- Troschinetz, A. M., and R. J. Mihelcic. 2009. Sustainable recycling of municipal solid waste in developing countries. Waste Manage. 29 (2):915–23. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2008.04.016.

- Ulhasanah, N., and N. Goto. 2018. Assessment of citizens’ environmental behavior toward municipal solid waste management for a better and appropriate system in Indonesia: A case study of Padang City. J. Mat. Cycles Waste Manage. 20:1257–72. doi:10.1007/s10163-017-0691-4.

- UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlements Program). 2015. The challenge of the local government financing in the developing countries, the City of Barcelona and the Province of Barcelona.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2016. Provision of services to prepare a Green House Gases (GHG) emission inventory and the mitigation chapters of Palestine’s Initial National Communication Report (INCR).

- Vigoroso, L., N. Pampuro, G. Bagagiolo, and E. O Cavallo. 2021. Factors influencing adoption of compost made from organic fraction of municipal solid waste and purchasing pattern: A survey of Italian professional and hobbyist users. Agronomy 11:1262. doi:10.3390/agronomy11061262.

- World Bank. 2016. Sustainable Financing and Policy Models for Municipal Composting. Urban Development Series. Washington, D.C.

- Zorpas, A. A. 2019. The role of end of waste criteria in the framework of circular economy strategy. In 16th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology CEST2019, Rhodes, Greece, September 4–7. https://cest2019.gnest.org/.

- Zorpas, A. A. 2020. Strategy development in the framework of waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 716:137088. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137088.