Abstract

A frequently cited recommendation of public service motivation (PSM) research is to use PSM in the context of HR marketing. However, empirical evidence demonstrating the usefulness of addressing PSM in the recruitment process is limited. Moreover, we know little about the relative importance of PSM for public employers’ attractiveness. We address this gap using an experimental research design to investigate whether public service motivated individuals differ from extrinsically motivated individuals in terms of their attraction to organizations that emphasize either “traditional” public or private values in their employer branding. Our findings indicate that public service motivated individuals are attracted neither to public nor to private values in employer branding. Furthermore, individuals with very high levels of extrinsic motivation are more attracted to private values employer branding than to public values employer branding and to the control group.

Introduction

In recognition of the “war for talent,” especially for increasingly rare and expensive knowledge workers, becoming an “employer of choice” is a central human resource and a business imperative (Greening and Turban Citation2000; Martin et al. Citation2005; Wilden, Gudergan, and Lings Citation2010). With a workforce that is aging faster than the labor force as a whole, public organizations face the challenge of attracting and retaining talent in public service careers (Äijälä Citation2002; Leisink and Steijn Citation2008; Lewis and Frank Citation2002). As a result, increasing employer attractiveness—the interest of individuals to be employed by a certain organization (Lieber Citation1995)—is of key importance for public organizations.

A commonly held assumption is that public service motivation (PSM)—or the willingness to contribute to society at large and serving the public interest (Perry and Hondeghem Citation2008)—affects individuals’ attraction to government as the employer of choice (e.g., Carpenter, Doverspike, and Miguel Citation2012; Christensen and Wright Citation2011; Leisink and Steijn Citation2008; Lewis and Frank Citation2002; Perry and Wise Citation1990; Vandenabeele Citation2008), and therefore, recruitment for public sector organizations should be different from that for their private sector counterparts (Van der Wal and Oosterbaan Citation2013). On the basis of a systematic literature review, Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann (Citation2016) found that studies frequently recommend the use of PSM in the context of HR marketing. However, empirical evidence demonstrating the usefulness of addressing PSM in the recruitment process seems to be largely absent. Moreover, our knowledge is limited regarding the question of how “relevant the fulfillment of the need for public service motivation is in relation to other motives” (Leisink and Steijn Citation2008:131) when it comes to the attractiveness of an employer.

This study aims to increase our limited knowledge of whether the PSM dimension “Commitment to Public Values” (CPV), which refers to the degree to which an individual's interest in the public service is driven by the internalization of and interest in pursuing “traditional” public values, such as equity and accountability (Kim et al. Citation2013), can actually be used to attract future employees. In addition, we aim to better understand the relative importance of PSM as a predictor of sector choice by including extrinsic motivation in our analysis of the relationship between employer branding and the perceived attractiveness of an employer. In order to test the effect of the CPV and extrinsic motivation on the relationship between employer branding and the perceived attractiveness of an employer, we designed an experiment involving 66 master’s students from a Swiss university.

Assuming that PSM is beneficial for both individuals and organizations, and given the strained situation in many labor markets around the world, this study is highly relevant. It provides insights into the question of whether public service motivated individuals are actually attracted by a specific HR marketing practice: employer branding. In addition, from a more theoretical point of view, this study answers the call to investigate the importance of PSM in public service employer attraction (Leisink and Steijn Citation2008; Perry and Wise Citation1990), thereby focusing specifically on the fit between public values at the organizational level and public service motives at the individual level (Andersen et al. Citation2012; Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen Citation2008; Maesschalck, van der Wal, and Huberts Citation2008). In addition, we have responded to the call by various PSM scholars for more experimental research, since experimental research designs facilitate causal inference and the isolation of the effects of specific variables (e.g., Bouwman and Grimmelikhuijsen Citation2016; Wright and Grant Citation2010).

The next section discusses the theoretical background of employer branding and employer attractiveness. This is followed by a discussion of the role of CPV and extrinsic motivation in explaining the attraction to specific public or private values in the employer brand. After this discussion, the approach we used to test our expectations is explained in more detail, followed by a presentation of our results. On the basis of these results, we then propose suggestions for future research and describe the implications of our findings for theory and practice.

Theoretical framework

Employer branding and its effect on employer attractiveness

Employer branding is “the process of building an identifiable and unique employer identity” (Backhaus and Tikoo Citation2004:502). The employer brand differentiates the organization from its competitors and helps to communicate to potential and existing employees what the organization stands for (Love and Singh Citation2011). An organization’s employer branding is expected to influence potential employees’ perceptions of the functional and symbolic benefits of an organization (Backhaus and Tikoo Citation2004; Lievens, van Hoye, and Anseel Citation2007; Lievens, Hoye, and Schreurs Citation2005; Lievens and Highhouse Citation2003; Slaughter et al. Citation2004). Functional benefits describe elements of employment with the firm that are desirable in objective, concrete, and factual terms, such as salary, benefits, or leave allowances. These attributes trigger interest primarily because of their utility. Symbolic benefits, by contrast, describe the organization in terms of subjective, abstract, and intangible attributes. They convey company information in the form of imagery and general trait inferences and are related to perceptions about the prestige of the organization. The ability to convey symbolic benefits to employees makes employer branding especially useful, as symbolic benefits have been found to be more important than functional ones in predicting employer attractiveness, which describes the basic interest of an individual to be employed by a certain organization (Lieber Citation1995). According to Highhouse, Lievens, and Sinar (Citation2003:989), employer attractiveness “is reflected in individuals’ affective and attitudinal thoughts about particular [organizations] as potential places for employment.” However, this does not necessarily imply that the individual will also take action to join that specific organization. Individuals may be attracted to many organizations at the same time, and perceived attractiveness of an employer is likely to be influenced by employer branding. In the following, we will discuss in detail the relationship between employer branding and employers’ attractiveness, making use of insights from person-environment fit theory.

Organizational values as symbolic benefits in the employer brand

To investigate the potential role of employer branding in attracting public service motivated individuals, we use organizational values, which can be defined as “important qualities and standards that have a certain weight in the choice of action” (Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen Citation2008:468), as a means to make symbolic benefits in the branding more concrete and measurable. The focus here is on “shared organizational values,” or the values that dominate the present decision-making practices of the organization. This is in line with the literature on organizational culture, where it is argued that organizations have their own specific set of values that are encoded in their culture (e.g., Deal and Kennedy Citation1982; Schein Citation1992). This means that organizational values reflect what is important to an organization and serve as an indicator of a general standard of conduct. They demonstrate what an organization stands for and what employees can expect from it. As such, organizational values are a core element of employer branding that help organizations to communicate to potential and existing employees who they are and what they stand for.

Traditionally, scholars have differentiated between public and private organizational values (e.g., Bovens Citation1996; Jos and Tompkins Citation2004). Public values have been equated with public organizations and “traditional” or Weberian values such as impartiality, lawfulness, and neutrality. Efficiency, innovation, profit, and quality, on the other hand, are seen as private values and are associated with the private sector. This traditional perspective resonates with Frederickson’s (Citation2005) view on the incompatibility of the public value of fairness and the private value of efficiency. In a similar vein, De Graaf and Van der Wal (Citation2010) have questioned whether it is possible to do things right (that is, with integrity) while simultaneously realizing objectives (that is, being effective). In other words, many scholars warn against the possibility that private values may override public values.

According to Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen (Citation2008), the discussion about differences between public and private values is primarily of a theoretical and ideological nature; comparative empirical research efforts, in contrast, are few and far between. In order to fill this gap in knowledge, the authors empirically investigated organizational values of public and private sector managers. The present study provides evidence that differences in value preferences do in fact exist, but that “there are also a number of strong similarities between the values of government and business” (Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen Citation2008:476). The private sector values found were profitability, innovativeness, and honesty, whereas the public sector values were lawfulness, incorruptibility, and impartiality. The values in the “common core”—values that were perceived as important by both public and private managers—include accountability, expertise, reliability, effectiveness, and efficiency. Because this traditional conceptualization of public and private values has been found to be empirically distinguishable, we will use it as the basis from which we make different types of employer branding measurable (see the method section for more information about the operationalization of employer branding).

However, we also need to be aware of the fact that some scholars have pointed to the “blurring” (Bozeman Citation1987) of sectors as a consequence of the rise of new public management reforms on the one hand, and corporate social responsibility on the other (Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen Citation2008). Accordingly, it has recently been argued that, in addition to traditional public values, many other values can be considered “public” (Andersen et al. Citation2012). In this more “inclusive” view of what public values are, a number of different categorizations have been proposed. Hood (Citation1991), for example, distinguishes three clusters of administrative values that are part of the NPM doctrine: sigma (economy and parsimony), theta (honesty and fairness), and lambda (security and resilience). Meanwhile, Jorgensen and Bozeman (Citation2007) identified seven value constellations, categorizing 72 public values. Following this line of argument, there is not so much a “public versus private” distinction, but instead distinct types of public values, including more “businesslike” values focused on economy and parsimony, and more “traditional” values focused on honesty and fairness. However, the study by Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen (Citation2008) provides no evidence for one common set of values that is characterized by both public and private organizations. Therefore, as mentioned earlier, this study relies on the traditional distinction between public and private values for the operationalization of different types of employer branding.

Individual motives for employer attractiveness

Public service motivation

As mentioned in the introduction, there is a common assumption that a group of individuals with certain motives is attracted to work for government as a means of fulfilling their desire to serve society at large and contribute to the public interest (e.g., Christensen and Wright Citation2011). This motivation has been referred to as public service motivation (PSM) (Rainey Citation1982). Perry and Wise were the first to coin the concept of PSM as “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions” (Perry and Wise Citation1990:368). Although this definition is still widely used, others have refined it. For example, Vandenabeele (Citation2007:547) refers to the concept of PSM as “the belief, values and attitudes that go beyond self-interest and organizational interest, that concern the interest of a larger political entity and that motivate individuals to act accordingly whenever appropriate.”

The present authors agree that PSM is a multidimensional concept (e.g., Kim et al. Citation2013) encompassing the dimensions of Commitment to Public Values (CPV), Attraction to Public Service (ATP), Self-Sacrifice (SSF), and Compassion (COM). In this study, we focus on the dimension of CPV, which assesses “the extent to which an individual’s interest in the public service is driven by the internalization of and interest in pursuing commonly held public values, such as equity, concern for future generations, accountability and ethics” (Kim et al. Citation2013:83), in order to analyze the role played by PSM in the employer branding process. Andersen et al. (Citation2012) argue that the different PSM dimensions include values to a varying degree and found empirical evidence supporting this notion. In particular, they found that the CPV dimension correlated more strongly with a larger number of public values than the other PSM dimensions. Because of this strong link between CPV and public values, when investigating the potential role of symbolic benefits and employer branding in attracting public service motivated individuals, we focus not on PSM as a one- or multi-dimensional construct, but on CPV.

Extrinsic motivation

Although most scholars assume that highly public service motivated individuals are attracted to work for government as a means of fulfilling their desire to contribute to society and the public interest (e.g., Perry and Wise Citation1990; Vandenabeele Citation2008), research shows that extrinsic motivation also plays an important role. For example, French and Emerson (Citation2014) found that extrinsic motivation, “which refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome” (Ryan and Deci Citation2000:55), such as security, wages, and fringe benefits, was considered highly important among public sector employees, next to the opportunity to fulfill higher-order needs. Similarly, Stazyk (Citation2012:265) concluded that “performance-related pay and public service motivation may work in tandem—at least in some cases—to motivate employees.” Weske and Schott (Citation2016) go one step further and argue, based on Causal Orientation Theory, that different types of motives not only co-exist, but that different groups of individuals can also be motivated by different motivational profiles. Related to this, Leisink and Steijn (Citation2008) point out that we know little about how relevant PSM is in relation to other motives for organizational choice. The authors used the item “I want to contribute to solving societal problems” as a proxy for PSM and found that only 9% of Dutch governmental employees and 7% of educational employees cite PSM as their most important work motive. About the same percentage of employees stated salary as their most important motive (10% of governmental employees and 8% of educational employees). Houston (Citation2011) found slightly different results in a U.S. context. In his study, almost 35% of the public servants participating indicated that “a useful job to society” is very important to them, while only 14% said the same about a job with high income. Following on from this line of research, we argue that it is important to assess not only how PSM is reflected in an individual’s attraction to an employer’s branding, but also which role extrinsic motivation plays in this regard.

Matching organizational values and individual motives

One frequently discussed explanation for the role of symbolic benefits in employer's attractiveness relates to person-organization fit (P-O fit) theory (e.g., Backhaus and Tikoo Citation2004; Cable and Judge Citation1996; Foster, Punjaisri, and Cheng Citation2010; Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005). A central argument of this theory is that when there is compatibility or “fit” between the characteristics of an individual and her or his work environment, this fit may result in positive effects on both individual and organizational outcomes. Some authors have followed Tom’s (Citation1971) operationalization of P-O fit as personality-climate congruence (e.g., Ryan and Schmitt Citation1996); however, since Chatman’s (Citation1991) seminal work on P-O fit theory, attention has shifted to value congruence between organizational and personal values (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005). Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson (Citation2005) differentiate between complementary or supplementary fit. Complementary fit occurs when an individual’s characteristics or abilities fill a gap in the current environment (demands-ability fit) or when the needs of individuals are met by the environment (needs-supplies fit). Supplementary fit exists when the environment and the individuals share similar characteristics and values. In this study, we will focus on supplementary fit in order to explain the role of symbolic benefits in the perceived attractiveness of an employer.

On the basis of P-O fit theory, we expect that a match between the individual’s motivation and certain types of an organization’s values will result in high employer attractiveness, while a mismatch is likely to result in low employer attractiveness. More specifically, individuals are attracted to organizations with clear values that they themselves view as important (Chatman Citation1991) and to organizations that offer an opportunity for personal goal attainment (Pervin Citation1989). It is commonly recognized among psychologists that a key determinant for satisfaction with a certain situation is the extent to which it fulfills the individual’s goals (Higgins, Shah, and Friedman Citation1997). This means that if people perceive that they and the organization share similar values (supplementary fit) and if they believe that goals are attainable, then organization attractiveness is likely to be high.

We expect individuals with high levels of CPV to be attracted by organizations that focus on public values in their employer branding. These organizations share values similar to those of individuals with high levels of CPV and offer them an opportunity to attain their personal goals. Van der Wal and Oosterbaan (Citation2013) found that individuals with public service motivation are attracted to organizations with public values such as equality, self-sacrifice, and justice. This is in line with the findings of a systematic literature review on PSM (Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016). The aggregated results of this review suggest that public service motivated individuals are likely to choose public service jobs. Therefore, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1: Individuals with high levels of CPV are attracted by employer branding focusing on public values.

With regard to extrinsic motivation, previous research indicates that individuals working in the private sector attribute a higher value to extrinsic rewards, such as promotions, good wages, and shorter work hours (Crewson Citation1997; Houston Citation2000, Citation2006; Karl and Sutton Citation1998). Moreover, evidence suggests that individuals with high levels of extrinsic motivation are attracted by the private sector (Van der Wal and Oosterbaan Citation2013) and that, for example, high-need-for-achievement individuals prefer organizations offering individual payment systems more than their low-need-for-achievement counterparts do (Trank, Rynes, and Bretz Citation2002). Therefore, we expect that extrinsically motivated individuals will be responsive to private values in employer branding and formulate the following second hypothesis:

H2: Individuals with high levels of extrinsic motivation are attracted by employer branding focusing on private values.

Research design

An experimental design is most appropriate to tackle our research question since it enables us to simulate symbolic benefits of the employer branding process and to control for other influences—such as prior knowledge about the organization, types of jobs available at the organization, and familiarity with the organization’s branding—that are also at play when investigating the effect of existing employer branding on the perceived attractiveness of an employer (Iyengar Citation2011).

Setting and context

The research model was evaluated using a two-stage experimental research design, combining a preliminary online survey and a campus-based classroom experiment at a Swiss university. Although some researchers have criticized the use of students on account of the limited external validity, there are also a number of arguments that justify the use of students. First, we use master’s students since they are expected to naturally relate to questions of (initial) job choice, being in their last year of studies (Carpenter, Doverspike, and Miguel Citation2012). The relevance of the topic to students is also shown by the majority of participants who have previously engaged in a job search. When asked how often they viewed job advertisements, only 7.7% of the respondents indicated that they never do. We chose to include all master’s students from a Swiss university since previous research (Vandenabeele Citation2008) has shown that several study backgrounds are relevant for attraction to public or private organizations. Second, using students has advantages for internal validity, since it may be expected that students are a more homogenous sample than a non-student sample (Margetts Citation2011). A more heterogeneous sample of individuals in employment may make the association between treatment and outcome less clear (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell Citation2002), as participants could be influenced by other factors, such as previous employment experience. Third, the validity of an experiment is based on the principle of random allocation of individuals to treatment and control groups, rather than the representativeness of the sample (Anderson and Edwards Citation2015).

Procedure

In February 2014, all 3,665 master’s students at a Swiss university were invited by e-mail to participate in the experiment and, in return for participation, were promised CHF 20, which they could either keep or donate to a charity. The experiment consisted of two interconnected stages. In the first stage, a total of 75 students completed a preliminary online questionnaire in which their motivations and background variables were measured. Out of these 75 students, 66 ultimately participated in the second stage (in which the treatments were administered) in March 2014. This second stage was organized as an on-campus classroom experiment. The low overall response rate was likely due to the fact that only a small number of students use the university’s e-mail system (which we used to send out the invitations to participate) on a regular basis and due to the large number of projects that attempt to recruit students through this channel, as a subsequent inquiry revealed. To anonymously connect the survey responses (stage 1) to the results of the classroom experiment (stage 2), students were asked to create an identification number based on the letters of their parents’ first name and the last three digits of their mobile phone number. In the second stage, students were randomly allocated to one of the two experimental groups or the control group. They were provided with descriptions of organizations (the treatments) and were instructed to imagine that they were searching for an entry-level job for themselves. After reading the organization descriptions, students were asked to fill in a post-experiment questionnaire. This questionnaire included questions about the perceived values of the organization (the treatment check) and their attraction to the organization.

Experimental design

A between-group design was set up for the experiment. In this design, the independent variable (employer branding) was manipulated in order to test its effect on the dependent variable (employer attractiveness). Two experimental organization descriptions (public values and private values) and one control description were created. The different parts of the descriptions were based on the investigation of several employer branding efforts and job advertisements. In addition, two interviews were conducted with HR managers responsible for employer branding in different sectors in order to ensure the realism of the treatments.

Both treatments and the control group shared a “common core” (based on the common core values found by Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen (Citation2008)) that contained fictional descriptions of organizations (presenting organizational characteristics such as offering a wide range of products and services) and information about what the organization offers (including flexible work hours and a competitive salary). These descriptions were included for all groups to resemble an actual situation of recruitment as closely as possible. At the same time, these descriptions were formulated as neutrally as possible in order to prevent the participants from (not) being attracted due to these descriptions or making associations with real-life organizations or the nature of possible jobs. Moreover, the visual design of all organizational descriptions was the same for all groups (see Appendix 1 for the design).

In addition to information about the organization and what the organization offers, the individuals in the treatment groups received information about the values of the organization (the symbolic benefits), which reflected both an organization's internal and external orientation. This information was presented under the headings “our key values,” “our employees about us,” and “our goal.” These three headings used different formulations to emphasize the same set of values. The purpose of this was to ensure that the participants noticed the importance of these values for the organization.

Two variants of these values were created, one referring to public values (treatment 1) and the other referring to private values (treatment 2), respectively. The distinction between the two types of values was based on empirical research comparing values in the public and private sector (Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen Citation2008). In order to clearly separate the two treatments, we selected only values that are especially strongly associated with the specific sectors; values that were important in both sectors were omitted. For treatment 1, we selected three values that characterize public sector organizations: impartiality, incorruptibility, and lawfulness. For treatment 2, we selected the values of innovativeness and profitability. Since no other private values were included in the study by Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen (Citation2008), we added the value of competitiveness, which can be seen as a typical private value due to the absence of market competition in the public sector (Rainey and Chun Citation2005).

Before carrying out the experiment, a pre-test was performed with a small number of students to test whether the manipulation was perceived as intended. Based on this test, the organization descriptions and the layout of the treatments were improved.

Descriptive statistics

Our final sample comprised 66 master’s students from different faculties at a Swiss university. We checked the sample for homogeneity on a number of variables that could affect the perceived attractiveness of an employer, such as gender, age, semester of master’s studies, previous encounters with employer branding (expressed in the number of job applications within the last year), and faculty of study. Furthermore, the moderating variables CPV and extrinsic motivation were also included.

shows that the sample consists of 79% females with an average age of 25.9 years (SD = 4.4) who have been studying for an average of 3.3 semesters (SD = 1.2) and have applied for 3.1 jobs (SD = 2.3). Furthermore, their average CPV score is 6.2 (on a 7-point scale, SD=.7) and their extrinsic motivation averages 4.9 (on a 7-point scale, SD = 1.1).Footnote1 shows the faculty of study of the participants.Footnote2 Students from six different faculties participated: medicine (N = 1), humanities (N = 9), human sciences (N = 22), science (N = 10), law (N = 12), and business, economics, and social sciences (N = 12).

Table 1. Sample composition on background variables.

Table 2. Sample composition based on faculty.

Table 3. Multivariate OLS regression analyses for predicting perceived attractiveness of an employer.

TABLE A1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

The differences between the control and treatment groups on these variables were all insignificant (see and ), indicating effective randomization. This should cancel out any confounding effects, making it unnecessary to include these background variables in further analyses.

A post-hoc power test for unequal sample sizes revealed that, on the basis of the means, the statistical power in the experimental treatments is .98 (α = .05, df = 63, N = 66, f = 0.54), thus exceeding the recommended statistical power of .80 (Cohen Citation1988).

Measures

Several measurement scales were used to measure the variables included in the research model. Since some of these scales had not been sufficiently validated in the original studies, we used exploratory factor analysis instead of confirmatory factor analysis to assess the validity of all scales (Fabrigar et al. Citation1999:277) (). The dependent variable employer attractiveness was measured using the organizational attraction scale developed by Highhouse, Lievens, and Sinar (Citation2003). Factor loadings were .75 or higher and Cronbach’s alpha was .89. The moderating variable Commitment to Public Values (CPV) was measured using the items from the PSM scale developed by Kim et al. (Citation2013). All CPV items had loadings above .67 and Cronbach’s alpha was adequate (.70). The moderating variable extrinsic work motivation was measured using Neumann’s (Citation2016) validated measure, which is based on various existing motivation measurement scales. The advantage of this generic scale is that it does not focus solely on certain limited aspects of extrinsic work motivation depending on the specific focus of a study (e.g., reward preferences, prestige, career opportunities), but on a more encompassing set of extrinsic motivation facets. Moreover, the scale is suitable for assessing general extrinsic work motivation because it is not developed for individuals performing a specific job (e.g., teaching). Factor loadings of this scale are all above .63 and Cronbach’s alpha is .88. For our manipulation check (see the following), we measured the perception of public and private values using the value formulations by Van Der Wal, de Graaf, and Lasthuizen (Citation2008). Both had high loadings (consistently above .84 for public values and above .83 for private values) and high Cronbach’s alphas (.93 for public values and .89 for private values). All measurement scales were aggregated by calculating a mean score of the respective items of each construct.

Manipulation check

To check whether the participants perceived the experimental treatments (the manipulation) in the way we had intended, we performed a manipulation check. This was done by asking respondents to which degree they had perceived the particular values as being contained in the organization descriptions. An ANOVA test showed that the manipulation was indeed successful: the public values treatment group perceived a higher degree of public values (M = 6.54, on a scale from 1 to 7) than the private values treatment group (M = 3.30) and the control group (M = 4.02) (F = 57.345, p = < .001). The private values treatment group perceived higher private values (M = 6.65, on a scale from 1 to 7) than the public values treatment group (M = 3.12) and the control group (M = 4.25) (F = 51.087, p= <.001). All of these differences were highly statistically significant.

Results

At the beginning, we investigated the difference in attraction between individuals included in the three experimental conditions. Individuals in the public values treatment group have a mean attraction of 5.76 (SD=.99), individuals in the private values treatment group have a mean attraction of 4.79 (SD = 1.29), and individuals in the control group have a mean attraction of 5.99 (SD=.60). The results indicate that there is a significant difference in perceived attractiveness of an employer between the treatments (F = 8.23, p < .001). A post-hoc Tukey test showed that the private values treatment differed significantly from the public values treatment (p < .01) and from the control group (p < .001). No significant difference in attraction was found between individuals in the public value treatment group and the control group. These results indicate that the individuals included in our sample are significantly less attracted to the private values treatment than to the public values treatment or the control treatment. In order to test both the direct effect of the treatments and the interaction effects of the treatments with the various motivations (extrinsic and CPV), we used multivariate OLS regression analysis to estimate three models. In a first step, we computed the direct effects of public and private values employer branding on the perceived attractiveness of an employer (model 1). Second, we added CPV and extrinsic motivation to assess the combined effect of employer branding and motivation (model 2). Third, we added the interaction effects between employer branding and CPV and employer branding and extrinsic motivation (model 3). Reflecting our focus on the link between motivation and values, the third step of the analysis is the most important in order to test our hypotheses. Following common practice in experimental research, we have included the two experimental treatments as dummies to the analyses and used the control group as a reference category. The results of the regression analyses are shown in .

In the first step, we found that, compared to the control group (no public or private values), only the private values employer branding had a statistically significant, negative impact on the perceived attractiveness of an employer (B = –.1.194, p < .001). This means that exposure to the private values treatment led to an average decrease of 1.2 points in the perceived attractiveness rating compared to the control group, whose average attractiveness rating was 6.0 (on a 7-point scale).

In the second step, after adding the two motivation-related variables, only extrinsic motivation was directly and positively related with attraction (B = .400, p < .001), while the coefficient for private values remained virtually unchanged (B = –1.217, p < .001). The coefficient estimate for extrinsic motivation translates to an average increase of .4 points in perceived employer attractiveness for each one point increase in the variable extrinsic motivation for all experimental groups (again, both variables were measured on 7-point scales).

Although steps 1 and 2 show significant effects on our dependent variable, our main interest is the interaction of motivation and employer branding efforts. In this third step, the adjusted R2 doubled from .18 in model 1 to .37 in model 3. This indicates that the additional variables included add value when explaining the perceived attractiveness of an employer. The first hypothesis focuses on the attraction to the public values treatment among individuals with high levels of CPV, while the second hypothesis focuses on attraction to the private values treatment among individuals with high levels of extrinsic motivation. After adding the four interaction terms in model 3, only the interaction effect of extrinsic motivation and the private values treatment had a significant effect on the perceived attractiveness of an employer. This means that no significant effects were found for the interaction between CPV and either of the treatments. Therefore, our data did not support the first hypothesis that individuals with high levels of CPV are more attracted to employer branding focusing on public values as seen in the match between CPV and values.

To check whether the lack of significant effects of CPV may be explained by low statistical power, we have conducted several power tests. First, we have tested the power of model 3 as a whole. The post-hoc power test for linear multiple regression (Faul et al. Citation2009) indicates that, on the basis of the R2 deviation from zero, the statistical power of model 3 is .99 (α = .05, df = 57, N = 66, f2 = 0.81), thus exceeding the recommended statistical power of .80 (Cohen Citation1988). In addition to testing the power of model 3 as a whole, we conducted several robustness checks. First, we conducted a power test for the power of model 3 without the direct and interaction effect of extrinsic motivation. The post-hoc test for multiple regression on the basis of the R2 deviation from zero indicated that the statistical power of the model is .89 (α = .05, df = 60, N = 66, f2 = 0.27). Second, we conducted a power test for the added explained variance of model 3 compared to model 1 to check whether CPV and extrinsic motivation—and their interaction with the experimental treatments—have sufficient statistical power. The post-hoc power test for linear multiple regression, based on the R2 increase, indicates that the power is .92 (α = .05, df = 57, N = 66, f2 = 0.32). Third, we conducted a power test in which we test for the power of the added variance of model 3 as compared to model 1 without the direct and interaction effects of extrinsic motivation. Doing so allowed us to check whether a model that includes CPV and the interaction of CPV with the experimental treatments has sufficient statistical power as compared to a model with treatments only (model 1). The post-hoc power test for multiple linear regression, based on the R2 increase, indicates that the power is .06 (α = .05, df = 60, N = 66, f2 = 0.003). This low power indicates that our model does not have sufficient power to detect added variance explained by adding CPV and the interaction of CPV with the experimental treatments. We will reflect on this power issue in the discussion section of this article.

The significant interaction effect of extrinsic motivation and private values (B = .908, p < .001) indicates that, compared to individuals in the control group, individuals in the private values treatment group differ significantly in their attraction to the employer. Since our first analysis indicated that only the private values treatment differs significantly from both the control group and the public values treatment, we have computed an additional analysis, which uses the private values treatment as the reference category. This analysis indicates that the interaction effect of CPV remains non-significant regardless of the reference group, whereas the interaction effect of extrinsic motivation and private values remains stable.

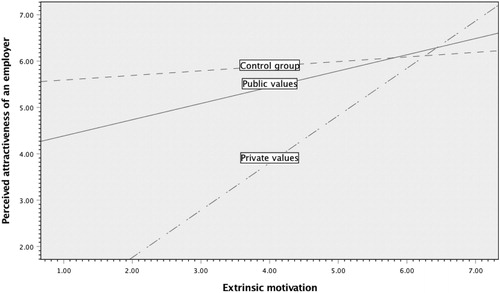

For the interpretation of the statistically significant interaction effect, we turn to the marginal effects plot in . On the y-axis of the plot, we see the average degree of perceived employer attractiveness. On the x-axis, we see the average degree of extrinsic motivation. The solid slope represents individuals in the public values treatment group, the double-dashed slope represents individuals in the private values treatment group, and the dashed slope represents individuals in the control group. The fact that all slopes are positive indicates that, in general, the higher the level of extrinsic motivation, the higher the attractiveness of an employer.

The interaction plot shows that, compared to individuals in the public values treatment group and the control group, individuals in the private treatment group are least attracted to the employer when they have low to high levels of extrinsic motivation (ranging from 1 to 6.3). Only when individuals in the private treatment group have extremely high levels of extrinsic motivation (between 6.3 and 6.5) do they find the private values treatment more attractive than the control group and the public values treatment. These results indicate that the private values treatment is more attractive only for individuals with extreme levels of extrinsic motivation. Individuals with low, medium, and high levels of extrinsic motivation are more attracted to the public value treatment and control group treatment.

These findings support our second hypothesis, postulating that individuals with higher levels of extrinsic motivation are highly attracted to private values in the employer branding in part only. In line with our expectations, we found a higher level of attraction to private values among individuals with higher levels of extrinsic motivation. Contrary to our expectation, however, only individuals with very high levels of extrinsic motivation are more attracted to the private values treatment than the public values and control group treatments.

Discussion and conclusion

This study contributes to the literature on the role of the PSM dimension of commitment to public values (CPV) in the attraction and selection of public service motivated employees. Studies frequently recommend that public organizations should use PSM for recruitment purposes, but limited empirical evidence supporting this recommendation can be found (Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016). This study empirically investigates whether individuals with high levels of CPV are indeed attracted by public organizations using specific employer branding strategies. Whereas a large amount of theoretical and empirical research in the field of public service motivation claims that individuals with high levels of PSM are interested in public organizations and public service jobs (e.g., Lewis and Frank Citation2002; Naff and Crum Citation1999; Steen Citation2008), our results indicate that using a specific HR (marketing) instrument—so-called “employer branding”—to attract these individuals might be more complex and less effective than expected.

We did not find an interaction effect between the PSM dimension CPV and the public values treatment to have significant effects on the perceived attractiveness of an employer (H1). Individuals scoring high on CPV seem not to be attracted to an organization displaying public values in their employer branding. This finding is not in line with earlier survey-based studies focusing on the role of PSM in explaining the employer attractiveness of public sector organizations (e.g., Lewis and Frank Citation2002; Naff and Crum Citation1999). We will therefore discuss several statistical and theoretical explanations for this unexpected finding.

A first explanation is statistical in nature and relates to the sample upon which our analysis is based. As we have shown in the results section, our model does not have sufficient power to detect an increase in explained variance by adding CPV and the interaction of CPV with the experimental treatments (as compared to a model including the treatments only) to the model. This means that, whereas the statistical power of the model as a whole is sufficient, the power of our study was too low to find significant effects for the interaction effect of CPV and the public values treatment. This is likely to be associated with the relatively small effect of CPV, as compared to the effect of extrinsic motivation.

In addition, as shown in , the average CPV score is a rather high 6.2 (on a 7-point scale) and not much variation among the participants can be found (SD=.7). Even though low variance is not uncommon in PSM research (see, e.g., Kim et al. Citation2013; Ward Citation2014) and the high PSM may result from the fact that all participants were enrolled as students at the University of Bern, which claims to serve the capital region by providing knowledge for a sustainable development of society and the local economy, and most participants come from faculties such as the humanities (psychology, education science, and sports science), law, and social science; we need to be aware of the risk of sampling bias. As the scores of CPV were high among all three experimental groups, participants in the private values treatment may have reacted comparatively strongly and the public values treatment may not have delivered its effects as hypothesized.

The high level of CPV and its limited variance among participants found in this study not only help to explain the unexpected findings of this study, but they are interesting in themselves. They provide additional support for Kim and Kim’s (Citation2016) argument that people tend to respond in a socially desirable way when responding to questions about PSM. In addition, they stress the importance of socialization as a source of PSM (e.g., Perry and Vandenabeele Citation2008; Vandenabeele Citation2007). As all participants were students at the same public university, the low variance among respondents may be interpreted as the result of socialization processes.

In addition to statistical explanations, our findings can also be explained by theoretical arguments. One theoretical explanation for our non-finding could be that individuals who are highly committed to public values are less inclined to search for careers and to pursue job offers. Instead, public service motives may be satisfied by less formalized (job) settings, such as volunteering (Houston Citation2006; Lee Citation2012). Another explanation for this non-finding might be the limited relative importance of CPV in explaining employer attraction compared to other types of motivation, such as extrinsic motivation. In a Western market economy, a potential job and an organization as potential employer might, at the preliminary stage, be instrumental in satisfying extrinsic motives. This may be the case in particular for young individuals who are about to apply for their first serious job after completing their master’s degree. In the early stages of a career especially, extrinsic motives such as good career prospects and high wages are likely to be more important for an organization’s attractiveness than motives related to CPV (Kanfer and Ackerman Citation2004). An additional explanation for the absent effect could be that there are other potential values that can be considered relevant to public organizations and attractive to public service motivated individuals, such as the public at large, budget keeping, professionalism, balancing interests, efficient supply, and user focus (see Andersen et al. Citation2013; Jorgensen and Bozeman Citation2007).

Net to the unexpected findings, we did find a significant interaction effect for extrinsic motivation and our private values treatment. Partly in line with both H2 and previous research (e.g., Crewson Citation1997; Houston Citation2000), we found that privately branded organizations seem to be more attractive for very highly extrinsically motivated individuals than for low, medium, and highly extrinsically motivated individuals. This indicates that a “match” in values does indeed lead to greater attraction, but only where there are extremely high levels of extrinsic motivation. Moreover, our results indicate that individuals with higher levels of extrinsic motivation are, in general, more attracted to potential employers. These findings again indicate the importance of extrinsic motivation in a recruitment context.

This study also has a number of limitations. First, as we have argued when explaining the non-significant findings of CPV, there are limitations associated with our sample. These include a low statistical power that does not allow us to detect small effects and limited variance on the scores on CPV. Together, these limitations may have resulted in non-significant findings regarding our hypothesis regarding the match between CPV and a public values treatment in explaining attraction to an employer.

Second, the experimental treatments focused on public and private values, rather than the opportunity to contribute to society. This means that the central aspect of PSM—which is contributing to society (Perry and Hondeghem Citation2008; Schott et al. Citation2017)—is not reflected in our experimental treatment. However, when focusing on the opportunity to contribute to society, it is difficult to think of a contrasting treatment (i.e., self-interest) at the organizational level. Moreover, the concept of contributing to society is very elusive and cannot be defined (Bozeman Citation2007). Therefore, individuals might attach different meanings to the concept, for which it is not possible to control.

Third, the second stage of the experiment was conducted in a laboratory, using master’s students as research participants. This could pose a threat to the external validity and generalizability of our findings, since previous research has shown that individuals respond to different motives at different stages of their life. Therefore, the findings are limited to individuals in the early phase of their career. However, students also have the advantage of being a homogenous group, as we discussed in the method section (i.e., not influenced by prior working experiences). Additionally, master’s students actually orient themselves towards the labor market. However, against the backdrop of our sample from only one university, we highly recommend that this study be replicated including other samples of participants.

Fourth, presenting descriptions of organizations without referring to an actual organization and specific organizational characteristics could pose a threat to how realistic the experiment is perceived to be. However, the description was the same for all subjects in our experiment, and therefore does not affect the internal validity. Moreover, we spoke to practitioners from both sectors before conducting the experiment in order to make the descriptions more realistic.

For practice, our findings suggest that the role of CPV-related motives in predicting the attractiveness of an employer is, if at all, limited. As a result, organizations need to be aware of the limited importance of PSM-related motives for the organization’s attractiveness for graduate students from the outset. Therefore, they are advised to focus on HR activities that stimulate PSM (see, for example, Giauque, Anderfuhren-Biget, and Varone Citation2013; Schott and Pronk Citation2014) after hiring if they want to ensure a public service motivated workforce.

For future research, we recommend that this study be repeated with a larger sample (to have more statistical power) so that a more robust answer can be given to the question of whether PSM plays a role in the recruitment process. Preferably, the ideal sample size should be computed with an a priori power test (Faul et al. Citation2009).We also suggest to pay close attention to the sampling strategy. Assigning individuals with high and low levels of PSM to public and private treatment groups, respectively, enables us to draw stronger conclusions and to ensure that the non-findings are not the result of potential sample bias. Furthermore, we recommend that greater attention be focused on the concrete role that PSM in general, and the PSM dimension CPV in particular, may play in attraction and selection processes. This could, for example, be done by investigating other aspects of employer branding (such as functional benefits) or focusing on other HR (marketing) instruments (e.g., social media recruitment and recruitment and career fairs). In addition, future research should differentiate more between functions, professions, and sectors to further investigate what attracts public service motivated individuals to apply for a position. Such research could focus, for example, on more specific job components that attract public service motivated individuals. In one instance, Leisink and Steijn (Citation2008) found that more than 50% of governmental and educational employees mention job content as their most important work motivation.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to empirically investigate the recommendation that PSM should be used in the attraction and selection of future employees. In addition, we answered the call to investigate the relative importance of PSM as a criterion of employer attractiveness. Our experimental approach allowed us to isolate the use of values in the HR instrument of employer branding. Our findings are interesting because they are not in line with the common recommendation found in PSM research, which is to focus on PSM in the attraction and selection of future employees. Instead, the findings suggest that the potential advantages of using symbolic benefits—a specific form of employer branding—to attract individuals with high levels of the PSM dimension CPV are limited. This suggests that greater scholarly attention should be devoted to critically investigating whether, and how, organizations can attract individuals with high levels of PSM, while taking into account the fact that the relative importance of PSM as a predictor of organizational choice may be limited. However, we are also well aware of the fact that these findings may be the result of low statistical power and therefore call for more experimental research based on lager sample sizes.

Appendix

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robin Bouwman for his advice on the statistical analysis used in this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ulrike Weske

Ulrike Weske ([email protected]) is a Ph.D. student at the University Medical Center Utrecht and the Utrecht University School of Governance. Her research focuses on the implementation and internalization of quality and safety initiatives in hospitals.

Adrian Ritz

Adrian Ritz ([email protected]) is a professor of public management at the KPM Center for Public Management at the University of Bern, Switzerland. His research interests focus on public management, leadership, motivation, and performance in public organizations.

Carina Schott

Carina Schott ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at the Utrecht University School of Governance (USG). Carina Schott conducts research in the field of public management at the individual level. Specifically, her research concerns the motivation and decision-making processes of public servants and the implications of a changing work environment on the nature of their work.

Oliver Neumann

Oliver Neumann ([email protected]) is a postdoctoral researcher in the Institute of Information Systems at the University of Bern in Switzerland. His research interests include public sector innovation, digital transformation in government, open data, and organizational behavior.

Notes

1 While the variance of the CPV measure was rather low, which may have affected certain non-findings, it should be noted that such low variance is not uncommon in PSM research (see, e.g., Kim et al. Citation2013; Ward Citation2014).

2 The results are shown for faculties. We also checked whether the experimental groups were homogeneous with regard to the degree courses followed by the participants. Since we did not find any significant differences here (=30.549, p=.438), this analysis is not included in the results section.

References

- Äijälä, K. 2002. Public Sector - An Employer of Choice? Report on the Competitive Public Employer Project. Paris: OECD.

- Andersen, L. B., T. B. Jorgensen, A. M. Kjeldsen, L. H. Pedersen and K. Vrangbaek. 2013. “Public Values and Public Service Motivation: Conceptual and Empirical Relationships.” The American Review of Public Administration 43(3):292–311.

- Andersen, L. B., T. B. Jørgensen, A. M. Kjeldsen, L. H. Pedersen and K. Vrangbaek. 2012. “Public Value Dimensions: Developing and Testing a Multi-Dimensional Classification.” International Journal of Public Administration 35(11):715–28.

- Anderson, D.M., and Edwards, B.C. 2015. “Unfulfilled Promise: Laboratory Experiments in Public Management Research.” Public Management Review 17(10):1518–42.

- Backhaus, K. and S. Tikoo. 2004. “Conceptualizing and Researching Employer Branding.” Career Development International 9(5):501–17.

- Bovens, M. (1996). “The Integrity of the Managerial State.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 4(3):125–32.

- Bouwman, R. and S. Grimmelikhuijsen. 2016. “Experimental Public Administration from 1992 to 2014: A Systematic Literature Review and Ways Forward.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 29(2):110–31.

- Bozeman, B. 1987. All Organizations are Public. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bozeman, B. 2007. Public Values and Public Interest: Counterbalancing Economic Individualism. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Cable, D. M. and T. A. Judge. 1996. “Person-Organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67(3):294–311.

- Carpenter, J., D. Doverspike and R. F. Miguel. 2012. “Public Service Motivation as a Predictor of Attraction to the Public Sector.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 80(2):509–23.

- Chatman, J. A. 1991. “Matching People and Organizations: Selection and Socialization in Public Accounting Firms.” Academy of Management 1989(1):199–203.

- Christensen, R. K. and B. E. Wright. 2011. “The Effects of Public Service Motivation on Job Choice Decisions: Disentangling the Contributions of Person-Organization Fit and Person-Job Fit.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(4):723–43.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Crewson, P. E. 1997. “Public-Service Motivation: Building Empirical Evidence of Incidence and Effect.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7(4):499–518.

- Deal, T., and A. A. Kennedy. 1982. Corporate Cultures: The Rites of and Rituals of Corporate Life. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- De Graaf, G., and Van Der Wal, Z. (2010). Managing Conflicting Public Values: Governing with Integrity and Effectiveness. The American Review of Public Administration 40(6):623–30.

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., and Strahan, E. J. 1999. “Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research.” Psychological Methods 4(3):272–99.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A.G. 2009. “Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses.” Behavior Research Methods 41:1149–60.

- Foster, C., K. Punjaisri and R. Cheng. 2010. “Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate, Internal and Employer Branding.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 19(6):401–09.

- Frederickson, H. G. 2005. Public Ethics and the New Managerialism: An Axiomatic Theory. Pp. 165–183 in Ethics in Public Management, edited by H. G. Frederickson and R. K. Ghere. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- French, P. E. and M. C. Emerson. 2014. “Assessing the Variations in Reward Preference for Local Government Employees in Terms of Position, Public Service Motivation, and Public Sector Motivation.” Public Performance & Management Review 37(4):552–76.

- Giauque, D., Anderfuhren-Biget, S. and Varone, F. (2013), “HRM Practices, Intrinsic Motivators and Organizational Performance in the Public Sector”, Personnel Management 42( 2):123–50.

- Greening, D. W. and D. B. Turban. 2000. “Corporate Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce.” Business & Society 39(3):254–80.

- Highhouse, S., F. Lievens and E. F. Sinar. 2003. “Measuring Attraction to Organizations.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 63(6):986–1001.

- Higgins, E. T., J. Shah and R. Friedman. 1997. Emotional Responses to Goal Attainment: Strength of Regulatory Focus as Moderator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72(3):515.

- Hood, C. 1991. “A Public Management for all Seasons?” Public Administration 69(1):3–19.

- Houston, D. J. 2000. “Public-Service Motivation: A Multivariate Test.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10(4):713–28.

- Houston, D. J. 2011. “Implications of Occupational Locus and Focus for Public Service Motivation: Attitudes toward Work Motives across Nations. Public Administration Review 71(5):761–771.

- Houston, D. J. (2006). ‘Walking the Walk’ of Public Service Motivation: Public Employees and Charitable Gifts of Time, Blood, and Money.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16(1):67–86.

- Iyengar, S. 2011. “Laboratory Experiments in Political Science.” Pp. 73–88 in Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science, edited by J. N. Druckman, D. P Green, J. H. Kuklinski and A. Lupia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jorgensen, T. B. and B. Bozeman. 2007. “Public Values: An Inventory.” Administration & Society 39(3):354–81.

- Jos, P. H., and Tompkins, M. E. (2004). “The Accountability Paradox in an Age of Reinvention: The Perennial Problem of Preserving Character and Judgment.” Administration & Society 36(3):255–81.

- Kanfer, R., and Ackerman, P. L. (2004). “Aging, Adult Development, and Work Motivation.” Academy of Management Review 29(3):440–58.

- Karl, K. A. and C. L. Sutton. 1998. “Job Values in Today’s Workforce: a Comparison of Public and Private Sector Employees.” Public Personnel Management 27(4):515–27.

- Kim, S. H., and Kim, S. (2016). “National Culture and Social Desirability Bias in Measuring Public Service Motivation.” Administration & Society 48(4):444–76.

- Kim, S., W. V. Vandenabeele, B. E. Wright, L. B. Andersen, F. P. Cerase, R. Christensen et al. 2013. “Investigating the Structure and Meaning of Public Service Motivation across Populations: Developing an International Instrument and Addressing Issues of Measurement Invariance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23(1):79–102.

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., R. D. Zimmerman and E. C. Johnson. 2005. “Consequences of Individuals' Fit At Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person-Job, Person-Organization, Person-Group, and Person-Supervisor Fit.” Personnel Psychology 58:281–342.

- Lee, Y. J. 2012. “Behavioral Implications of Public Service Motivation Volunteering by Public and Nonprofit Employees.” The American Review of Public Administration 42(1):104–121.

- Leisink, P. L. M. and B. Steijn (2008). “Recruitment, Attraction, and Selection.” in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, edited by J. L. Perry and A Hondeghem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, G. B. and S. A. Frank. 2002. “Who Wants to Work for the Government?” Public Administration Review 62(4):395–404.

- Lieber, B. 1995. Personalimage: Explorative Studien zum Image und zur Attraktivität von Unternehmen als Arbeitgeber [Employer Image: Exploratory Studies On The Image and Attractiveness of Companies As Employers]. Munich: Germany Rainer Hampp.

- Lievens, F. and S. Highhouse. 2003. “The Relation of Instrumental and Symbolic Attributes to a Company's Attractiveness as an Employer.” Personnel Psychology 56:75–102.

- Lievens, F., G. Hoye and B. Schreurs. 2005. “Examining the Relationship between Employer Knowledge Dimensions and Organizational Attractiveness: An Application in a Military Context.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 78(4):553–572.

- Lievens, F., G. van Hoye and F. Anseel. 2007. “Organizational Identity and Employer Image: Towards a Unifying Framework.” British Journal of Management 18(s1):S45–S59.

- Love, L. F. and P. Singh. 2011. “Workplace Branding: Leveraging Human Resources Management Practices for Competitive Advantage Through ‘Best Employer’ Surveys.” Journal of Business and Psychology 26(2):175–181.

- Maesschalck, J., Z. van der Wal, and L. Huberts. 2008. “Public service motivation and ethical conduct.” Pp. 157–176 in Motivation in public management: The Call of Public Service, edited by J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Margetts, H. Z. 2011. “Experiments for Public Management Research.” Public Management Review 13(2):189–208.

- Martin, G., P. Beaumont, R. Doig and J. Pate. 2005. “Branding: A New Performance Discourse for HR?” European Management Journal 23(1):76–88.

- Naff, K. C. and J. Crum 1999. “Working for America: Does Public Service Motivation Make a Difference?” Review of Public Personnel Administration 19(4):5–16.

- Neumann, O. 2016. “Does Misfit Loom Larger Than Fit? Experimental Evidence on Motivational Person- Job Fit, Public Service Motivation, and Prospect Theory.” International Journal of Manpower 37(5):822–39.

- Perry, J. L. and A. Hondeghem. 2008. “Editors' Introduction.” Pp. 1–16 in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, edited by J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Perry, J. L., and Vandenabeele, W. (2008). “Behavioural Dynamics: Institutions, Identities and Self-Regulation.” Pp. 55–79 in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, edited by J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, J. L. and L. R. Wise. 1990. “The Motivational Bases of Public Service.” Public Administration Review 50(3):367–73.

- Pervin, L. A. 1989. “Persons, Situations, Interactions: The History of a Controversy and a Discussion of Theoretical Models.” Academy of Management Review, 14(3):350–60.

- Rainey, H. G. 1982. “Reward Preferences among Public and Private Managers: In Search of the Service Ethic.” American Review of Public Administration 16:288–302.

- Rainey, H. G.; Chun, Y. H. (2005). Public and Private Management Compared. Pp S.72–102 in The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, edited by E. Ferlie, L. E. Lynn and C. Pollitt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ritz, A., G. A. Brewer and O. Neumann. 2016. “Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook.” Public Administration Review 76(3):414–26.

- Ryan, R. M. and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55(1):68.

- Ryan, A. M. and M. J. Schmit. 1996. An Assessment of Organizational Climate and PE fit: A Tool for Organizational Change.” The International Journal of Organizational Analysis 4(1):75–95.

- Schein, E. H. 1992. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Schott, C., and Pronk, J. L. J. (2014). “Investigating and Explaining Organizational Antecedents of PSM.” Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship 2/1:28–56.

- Schott, C., Neumann, O., Baertschi, M., Ritz, A. 2017. “Public Service Motivation, Prosocial Motivation, Prosocial Behavior, and Altruism: Towards Disentanglement and Conceptual Clarity.” Paper Presented at the IRSPM Conference 2017, Budapest, Hungary.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., and Campbell, D. T. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Slaughter, J. E., M. J. Zickar, S. Highhouse and D. C. Mohr. 2004. “Personality Trait Inferences About Organizations: Development of a Measure and Assessment of Construct Validity.” Journal of Applied Psychology 89(1):85–103.

- Stazyk, E. C. 2012. “Crowding Out Public Service Motivation? Comparing Theoretical Expectations with Empirical Findings on the Influence of Performance-Related Pay.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 33:252–74.

- Steen, T. 2008. “Not a Government Monopoly: The private, nonprofit, and voluntary sector.” Pp. 203–222 in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service, edited by J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tom, V. R. 1971. “The Role of Personality and Organizational Images in the Recruiting Process.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 6(5):573–92.

- Trank, C. Q., Rynes, S. L. and R. D. Bretz 2002. “Attracting Applicants in the War for Talent: Differences in Work Preferences among High Achievers.” Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(3):331–45.

- Van Der Wal, Z., G. de Graaf and K. Lasthuizen. 2008. “What’s Valued Most? Similarities and Differences between the Organizational Values of the Public and Private Sector.” Public Administration 86(2):465–82.

- Van der Wal, Z. and A. Oosterbaan. 2013. “Government or Business? Identifying Determinants of MPA and MBA Students' Career Preference.” Public Personnel Management 42(2):239–58.

- Vandenabeele, W. 2007. “Toward a Public Administration Theory of Public Service Motivation.” Public Management Review 9(4):545–56.

- Vandenabeele, W. 2008. “Government Calling: Public Service Motivation as an Element in Selecting Government as an Employer of Choice.” Public Administration 86(4):1089–105.

- Ward, K. D. (2014). Cultivating public service motivation through AmeriCorps service: A longitudinal study. Public Administration Review, 74(1):114–25.

- Weske, U. and C. Schott (2016). “What Motivates Different Groups of Public Employees Working for Dutch municipalities? Combining Autonomous and Controlled Types of Motivation.” Review of Public Personnel Administration. doi:10.1177/0734371X16671981.

- Wilden, R., S. Gudergan and I. Lings. 2010. “Employer Branding: Strategic Implications for Staff Recruitment.” Journal of Marketing Management 26(1–2):56–73.

- Wright, B. E., and A. M. Grant. 2010. “Unanswered Questions about Public Service Motivation: Designing Research to Address Key Issues of Emergence and Effects.” Public Administration Review 70(5):691–700.