Abstract

Public service stereotypes have been the subject of various studies in public administration research. However, the cognitive processes that form the basis of these stereotypes and the heuristics processing of stereotypical information, remain empirically vague. Starting from insights on the anti-public sector bias and representativeness heuristic, we apply an experimental vignette study (n = 1,412) in which we analyze how citizens process information on employees' sector affiliation. Furthermore, we integrate non-work role-referencing to test the stereotype confirmation assumption underlying the representativeness heuristic. Our results show that sector as well as non-work role-referencing influences perceived employee professionalism but has little effect on positive stereotype confirmation. However, our results do not confirm a congruity effect of consistent stereotypical information.

Public service stereotypes have been a prominent subject of various studies in public administration research (Hvidman Citation2019; Hvidman and Andersen Citation2016; Marvel Citation2015; Meier, Johnson, and An Citation2019; Tummers Citation2019; Willems Citation2020). There are manifold everyday life examples that address either the abstract notion of public administration in general, such as ‘inefficient government’ or ‘rigid procedures’, or aim directly at employees working in the public sector, such as the ‘lazy bureaucrats’. Public sector employees are often referred to with a set of stereotypical associations, distinguishing them—at least with respect to their public image—from employees in the private sector. Evidently, these stereotypes are often argued to have a rather negative connotation (Tummers Citation2019; Van de Walle Citation2004).

These stereotypes are argued to have wide-reaching effects, including diminishing citizens’ trust in institutions (Stouffer Citation1955; Van de Walle Citation2004) and the attractiveness of public sector jobs (Korac, Lindenmeier, and Saliterer Citation2020; Ritz and Waldner Citation2011) as well as affecting the results of citizen evaluation (del Pino, Calzada, and Díaz-Pulido Citation2016). Thus, stereotypes play an important role in citizen-state interactions at all levels.

However, the cognitive processes that form the basis of these stereotypes, and the heuristic-based processing of stereotypical information, remain empirically vague. Nonetheless, as Van de Walle (Citation2004) argues, it is relevant to understand the stereotypes of public servants and the effects they have on the public sector. Moreover, if we better understand the cognitive processes underlying the stereotypes and citizens’ overall perceptions, and how they are amplified with stereotype-confirming information, we can also elaborate more precisely on theoretical and practical recommendations to change the undesired stereotypes of public servants. Therefore, we aim to gain a better understanding of how citizens process information of public servant stereotypes. In particular, we focus on the effect of stereotype-confirming information on the employee’s professional image as perceived by others. In other words, our research questions are as follows: Do employees in the public sector have a less professional reputation due to the fact that they are employed in the public sector, and is this less professional reputation aggravated as a result of stereotype-confirming information?

First, we empirically test whether public servants are indeed perceived as less competent and professional, just because they are working in the public sector. In doing so, we put a widespread assumption in political and societal debates as well as in the academic community to the test. Second, relying on the extensive literature from social psychology on employees’ perceived professional reputation, we test the additional effect of non-work role-referencing (NWRR) on professional reputation. Non-work role referencing describes the use of artifacts and activities at the workplace that refer to an individual’s domains of family and/or community (Fisher, Bulger, and Smith Citation2009, 442). This can, for example, encompass informal and colloquial ways of communication or decorating one’s workplace with personal mementos, such as family pictures. It is hypothesized that encountering such artifacts, customers or colleagues will perceive employee’s as being less competent due to the blending of professional and private life domains. Hereby, our study additionally replicated insights from social psychology in a public administration context while introducing a novel concept to this field of research. Third, we combine these two main assumptions in order to advance the theoretical development and empirical investigation of stereotypes and heuristic-based thinking. In doing so, we answer the call that combining insights from the public administration literature with other disciplines, such as social psychology, can improve our understanding of fundamental cognitive processes (Grimmelikhuijsen et al. Citation2017; Kelman Citation2007). Concretely, as non-work role referencing has been assumed negatively to affect professional reputation (Uhlmann et al. Citation2013), it provides a useful concept to test stereotype confirming cognitive processing. For that reason, we rely on the extensive literature of heuristics-based thinking to argue that additional stereotype-confirming information increases effects of low perceived individual professionalism (Bodenhausen and Wyer Citation1985). In testing this interaction, we may show how concrete characteristics of public servants indeed relate to such strong beliefs about public servants, and we can test whether assumptions of the more fundamental social psychology literature also apply to assumed stereotypes about public servants. In other words, and building on fundamental insights on stereotyping cognitive processes, we examine the hypothesis that congruent stereotypical information on being less professional—due to the sector in which someone works combined with individual non-work role referencing—can lead to an even more negative evaluation of that person’s professionalism.

For our empirical design, we rely on a seminal study in organizational psychology (Uhlmann et al. Citation2013) and build on their experimental design. However, we adjust and elaborate their design for a better fit with our specific research aim in the context of public servant stereotypes. This means that we adjust the design to test the main effect of sector of employment on employee professional image. As a result, we are on the one hand able to replicate the findings of Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013) with a substantially larger sample (n = 1,412; MTurk online survey). On the other hand, we elaborate their design by additionally testing (1) the effect of sector of employment—to test a potential anti-public servant bias—and (2) the interaction of that sector-effect with the effect of non-work role-referencing. Testing this interaction contributes to theory confirmation and elaboration about cognitive processes on stereotype confirmation in a public administration context, and in general.

Theory

Stereotypes and heuristics

Stereotypes are ubiquitous in human societies. As social interaction and communication are complex phenomena, interaction partners face an overwhelming flood of information from various explicit and implicit sources, which are difficult to decode (Bodenhausen Citation1993, 13ff). Simultaneously, humans tend to satisfice during such interactions due to limited resources and capacities (Simon Citation1955). Thus, stereotypes serve as an efficient information source to categorize subjects and derive characteristics and appropriate behavior toward these subjects. Bodenhausen and Macrae (Citation1998, 4) define stereotypes as “descriptive concepts that are associated with membership in a social category.” Humans tend to rely upon such categorization “whenever they lack the ability or the inclination to think more extensively about the unique personal qualities of outgroup members” (Bodenhausen, Sheppard, and Kramer Citation1994, 49).

Moreover, building on the heuristics-systematics framework in social psychology, stereotypes can be categorized as a heuristic (Bodenhausen Citation1993; Bodenhausen and Wyer Citation1985). Heuristics are defined as “knowledge structures, presumably learned and stored in memory” (Chen, Duckworth, and Chaiken Citation1999, 44). These structures provide quick and effortless access to supportive information.

Further, systematic processing describes a conscious and effortful retrieval and appraisal of information in order to make decisions. However, the process that is chosen and applied depends on the resources and motivation available in specific situations (Chen, Duckworth, and Chaiken Citation1999). If individuals find themselves confronted with complex information, time-pressure, and a lack of motivation, they are more likely to rely on heuristics (Wegener, Clark, and Petty Citation2006, 43). Therefore, “stereotype use is efficient not only during the encoding of social information, but also during its retrieval” (Sherman and Bessenoff Citation1999, 106). People rely on stereotypes to make social judgments (Bodenhausen and Wyer Citation1985), especially when those individuals are outgroup members.

It is, however, imperative to be aware that stereotypes do not only focus on negative projections. So-called ‘positive stereotypes’ associate certain characteristics (e.g., race) with positive expectations, such as athletic or cognitive skills (Czopp Citation2008). While one might make the mistake of belittling such types of stereotypes, they follow the same cognitive processes as their ‘negative’ counterparts. Furthermore, studies have shown the discriminating effects of such positive stereotypes (Czopp, Kay, and Cheryan Citation2015; Kay et al. Citation2013).

In the following section, we develop the three hypotheses for our study. While Hypothesis 1 covers the intensively discussed topic of anti-public sector bias, Hypothesis 2 focuses on a social psychological phenomenon of non-work role referencing as a cue for stereotype-based assessments. Hypothesis 3 provides a combination of both cues. Thus, we heed the call by Grimmelikhuijsen et al. (Citation2017) for combining social psychology with public administration research.

Employee professional image and sector-specific stereotypes

Organizations often form a strong social identity under which its members are supposed to be subsumed (Pratt and Corley Citation2007). In organizations offering services to clients, professionalism is one of most commonly assumed characteristics that members of the organization are expected to hold (Morrow and Goetz Citation1988). However, this notion of professionalism differs from what sociologists define as a profession and is used more broadly in this stream of research on employees’ professional image (Roberts Citation2005). In this sense, professionalism is the “individual’s ability to meet normative expectations by effectively providing a given service to clients and colleagues” (Roberts Citation2005, 687). Thus, it is desirable for an organization to have staff which is associated with characteristics and competences that are related to successful and effective service delivery.

Meanwhile, social identity theory differentiates between the self-perceived and others-perceived professional image (Stets and Burke Citation2000). The first is often referred to as a desired or intended image and conceptualizes our own expectations and definition of our social identity (Brown Citation2006). Accordingly, one implicitly or explicitly chooses social groups one identifies with and wants to belong to.

Building and maintaining a professional reputation among customers and colleagues are the result of relevant work-related signals which may stem from various sources. First, employees may directly demonstrate professionalism through their behavior (Hoobler, Wayne, and Lemmon Citation2009). Second, clients might formally and informally exchange opinions or experiences with each other about an employee, which in turn influences their images about the employee (Michelson, van Iterson, and Waddington Citation2010). Due to these social constructionist processes among colleagues and supervisors, the shared image about an employee constitute their professional reputation (Roberts Citation2005). However, when groups of people are similarly affected by common sources in terms of their personal reputation, stereotypes emerge that in turn lead to assumptions about other individuals with similar group characteristics. As a result, a mutual influence between sector and organizational characteristics on the one hand, and individual and group stereotypes on the other, can be assumed. This is important to study, as group and individual stereotypes might affect the organization’s attractiveness as an employer. More specifically, public organizations that suffer from a negative reputation might struggle to attract qualified employees (Korac, Lindenmeier, and Saliterer Citation2020; Ritz and Waldner Citation2011).

Furthermore, negative professional stereotypes of employees may reduce the trust put in these organizations (Van de Walle Citation2004). This is especially important for public organizations which depend on institutional trust. Moreover, the perceived professional image also affects the direct interactions of employees with clients. Studies have shown that the professional image of employees affects the client’s perception, resulting in lower expectations (Keh and Xie Citation2009), lower satisfaction levels (Habel et al. Citation2016; Kleijnen, de Ruyter, and Andreassen Citation2005), and lower thresholds for frustration in case of failures (Mostafa et al. Citation2015). Additionally, the reputation affects the client’s behavior by, for example increasing customer loyalty (Nguyen and Leblanc Citation2001; Srivastava and Sharma Citation2013).

Cues to assess this image may stem from various sources such as the organization’s reputation, own experiences, or word-of-mouth. However, we argue that sectoral associations may be an important source for individual employee stereotypes. Several studies in public administration research have focused on a potential anti-public sector bias (Hvidman Citation2019; Hvidman and Andersen Citation2016; Marvel Citation2015). Scholars argue that the general public holds implicit attitudes that cause an unconscious association of public organizations and their members with negative frames such as inefficiency, ineffectiveness, and slack (Tummers Citation2019). These prejudices may hold even if individuals have opposite experiences (del Pino, Calzada, and Díaz-Pulido Citation2016).

These prejudices are often amplified through media (Druckman and Parkin Citation2005; Ladd and Lenz Citation2009), continuous political blame shifting toward public organizations, and societal narratives which present negative connotations of words such as bureaucracy (Hvidman and Andersen Citation2016). Public servants are, therefore, often described as lazy, hiding behind rules and regulations, and inflexible. Such depictions may affect citizens’ perception of employees’ abilities to solve problems in citizen-state interactions. Further, Marvel (Citation2015) argues that implicit attitudes influence explicit attitudes toward individuals, eventually affecting their behavior. In this context, a study by Hvidman and Andersen (Citation2016) found experimental evidence that public hospitals are viewed as being less efficient while displaying more red tape. These results were partially replicated in two follow-up studies by Hvidman (Citation2019). Van den Bekerom, van der Voet, and Christensen (Citation2020) find that citizens preferring private sector service provision tend to penalize public service providers more severely in case of service failures. Furthermore, clients may presume that public employees suffer from higher constraints on their job, e.g. due to less funding or red tape which may affect their decision-making and performance capacities (Barnes and Henly Citation2018).

However, Willems (Citation2020) finds that negative words are associated with public servants, but that these play only a minor role. This is supported by a study from de Boer (Citation2020) that finds that both, positive and negative characteristics are associated with various types of street-level bureaucrats.

Nevertheless, as these studies do not explicitly focus on the public sector framing, for which a negative connotation has been documented in the literature, we hypothesize that a sector-related cue will result in less professional image attributed to employees working in the public sector.

Hypothesis 1: Employees of the public sector have a less professional image compared to employees in the private sector.

Role-referencing in public encounters

Stereotypes derive from various sources such as own experiences or narratives from trusted sources. Moreover, they are activated in different situations. Public encounters or direct citizen-state interactions are some of the occasions that, aside from general attitudinal judgments, provide a multitude of cues, artifacts, and signals to form judgments. Visual artifacts, such as employees’ and workspaces’ appearance, are an especially strong source of information that may contribute to situational assessments. Scholars have shown the impact of such cues on citizen-state interactions (Karl, Hall, and Peluchette Citation2013; Raaphorst and van de Walle Citation2017). Moreover, non-work role referencing provides a significant source for such artifacts during interactions, and thus, may play an important role for stereotypical assessments.

Research on the boundary between work and non-work domains has gained substantial attention in organizational research over the past years. Numerous studies have examined the effects of work-life balance measures (for a review, see Kossek and Lambert Citation2004) and investigated the various consequences if this balance is shifted. Studies on work/non-work boundaries have further investigated how individuals manage their different work and non-work roles in the working environment (Greenhaus and Parasuraman Citation1999; Maxwell and McDougall Citation2004). Accordingly, some employees will pursue a strategy of segmentation, where they will try to clearly differentiate between their private and professional networks and environments by limiting information diffusion between either sphere and adjusting their behavior. However, other employees are more likely to blend these roles where they will “behave similarly with their co-workers as with their neighbors” (Uhlmann et al. Citation2013, 867). This may also translate to the organization and decoration of their workplace. Offices may be decorated with personal elements such as family pictures, motivational post cards, comics, etc. Such an individualization of the workplace may come with several advantages for the employee (Elsbach Citation2004), such as increased satisfaction (Donald Citation1994) and performance (Sundstrom and Altman Citation1989). However, it also serves as a source of signals toward coworkers and clients. These artifacts signal an accordance of the different roles and alternative roles expected from the employee (Ashford and Northcraft Citation1992). A collection of artifacts that deviate from expected roles may change the employee’s image perceived by others, such as clients.

Acknowledging the effect of perceivable artifacts on professional image, impression management is discussed as an essential element in professional services of various types (Bolino, Klotz, and Daniels Citation2014; Swartz and Iacobucci Citation2000). For instance, studies point to the importance of visual appearances, such as dressing (Rafaeli and Pratt Citation1993; Smith, Chandler, and Schwarz Citation2020). For example, Furnham, Shuen Chan, and Wilson (Citation2013) show that an employee’s attire affects the assessment of professionalism by the client.

Members who identify with this image will pursue displaying these characteristics to outer groups, thus shaping their behavior (Roberts Citation2005). Karl, Hall, and Peluchette (Citation2013) found evidence that this is a crucial mechanism in public services as well. They found that public employees in a U.S. municipality felt more authoritative and competent when dressing formally for their job. The respondents also expect that the dress code has an impact on their competence perceived by clients.

However, this self-image is not necessarily congruent with the image perceived by others. The perceived image is shaped by one’s nonverbal cues, verbal disclosures, and actions. These elements may unintentionally differ from the expected image that employees want to display.

Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013) investigated the effect of workplace decoration on the perceived professional image of employees. They found that fictitious employees are expected to have more non-work role referencing artifacts attached to their workplace if they are described as unprofessional. As various public services are provided within public offices, it is essential to understand the configuration of such workplaces. Visual artifacts such as the personalization of workspaces (Wells, Thelen, and Ruark Citation2007) have been shown to have complex relationships with antecedents and effects. Scheiberg found that the decoration of the individual workspace with personal mementos serves as “reflexive communication” (Citation1990, 335) to help cope emotionally and intellectually with the day-to-day work. Other studies have shown that such personal displays have a positive impact on the employees’ well-being and job satisfaction (Brill Citation1984; Wells Citation2000). However, such displays may also negatively affect others’ perception of performance (Brown and Zhu Citation2016).

Thus, we hypothesize that displays of substantial non-work role-referencing results in lower levels of professionalism perceived by others.

Hypothesis 2: Higher levels of non-work role referencing result in a lower professional employee image.

On “confirming stereotypes”

As argued above, people tend to use heuristics when confronted with various pieces of information and cues. A decision heuristic that is often discussed in this context is the representativeness heuristic, which evaluates the extent to which new information about a person is similar to an existing stereotypical image (Bodenhausen Citation1990; Grant and Mizzi Citation2014; Tversky and Kahneman Citation1983). When information about a person confirms this stereotype, the representativeness heuristics enables one to classify (the information about) this person with little mental effort within a broader, existing mental framework (Feldman Citation1981). However, due to this cognitive framing process, it is likely that other stereotypic characteristics are attributed to a specific person, even when no information was given on these characteristics in the first place (Bodenhausen Citation1990). Furthermore, Bodenhausen and Wyer (Citation1985) show that people attempt to interpret additional data in order to confirm stereotypes. If such data disconfirms stereotypes, people tend to even ignore such data (Bohnet, van Geen, and Bazerman Citation2016).

Hence, when a citizen is confronted with information or cues about an employee that is consistent with the characteristics of a stereotypical public sector employee, it is likely that an unconscious attribution is made of other characteristics as well (Dumas and Sanchez-Burks Citation2015; Feldman Citation1981; Uhlmann et al. Citation2013). Under the assumptions that public sector employees are attributed with a less professional image (Hypothesis 1) and that non-work role referencing also signals lower levels of professionalism (Hypothesis 2), we expect that both characteristics reinforce each other. Consequently, we can anticipate that when a citizen is confronted with additional non-work role information about an employee—which is information that is relevant for the particular work role of the employee (Olson-Buchanan and Boswell Citation2006)—the citizen is more likely to attribute other characteristics of the public sector employee stereotype and as a result, is also more likely to consider the employee as being less professional, even if no explicit information about professionalism was given. Hence, building on the representativeness heuristic, we test how individuals combine seemingly congruent cues that are supposed to trigger representativeness heuristics. Thus, due to stereotype-conforming cognitive processes, we assume that non-work role referencing will aggravate the negative impact of the public sector cues on the employees' professional reputation.

Hypothesis 3: Higher levels of non-work role referencing reinforce the negative public sector effect on professional employee image.

Method

Experimental setting

We conducted an online experiment with a 2 × 2 × 2-between-subjects design, in which we closely followed certain design features given by Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013). Respondents were given one of eight vignettes, which all contained a description of an employee along with an office picture (see the Appendix for all survey material). Across all vignettes, the basic description of the employee was kept constant and mentioned that the employee works as an accountant who assists citizens if they have questions about their taxes. As a first treatment, we varied the type of organization where the employee worked (public or private), which enabled us to test Hypothesis 1. As a second treatment, we manipulated the level of non-work role-referencing (low vs. high), which was done by varying the level of non-work role referencing in the office pictures. One picture showed the employee’s office with very little non-work role-referencing, while the other picture showed the exact same office but with the addition of several non-work role referencing elements (e.g. Family pictures, sunglasses, and post cards). This allowed us to test Hypothesis 2 and 3. Moreover, by diversifying the type of treatment by including a visual cue, we enhanced the cognitive stimulation in comparison to treatments solely relying on text vignettes.

However, while Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013) asked participants to assign these pictures to fictitious (un-)professional employees, we asked respondents to evaluate their assessment of professionalism, based on the pictures. Thus, our design is more consistent with the causal relation embedded in the logic of Hypotheses 2 and 3 and the literature built on for these hypotheses. Hence, while adapting the design of Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013) as a starting point, we provide a conceptual replication (Walker, James, and Brewer Citation2017) of the original study by advancing its theoretical implications through adaptions fitting our theoretical elaborations. Therefore, and similar to Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013), we also included an additional treatment with respect to gender as this was also varied—as a control—in their original study. This also serves as a control treatment to rule out gender-based biases. However, for the sake of parsimony, it is not part of the theoretical frame of our study. The employee in the description was either called Stephanie or Eric (i.e. the same names as in the original study by Uhlmann et al.).

Procedure

Having our 2 × 2 × 2-design in mind, we are able to detect a small effect size (f = 0.10) under the following assumptions: balanced one-way analysis of variance, k = 8 (number of groups), n = 175 (minimum number of observations per group), significance level = 0.05, power = 0.8, (Champely Citation2018; Cohen Citation1988).

Our online experiment was administered with Qualtrics surveys, and we relied on Mechanical Turk (MTurk) respondents. As the survey was expected to take less than one minute, respondents were paid US $0.20 for completion. Respondents were informed upfront that their participation was anonymous, voluntary, and served scientific research only. Moreover, they were informed that the payment might have been contingent upon correctly answering some attention questions. However, as it only concerned a small task for a minimal amount, we opened the questionnaire to 2,000 respondents and paid all of them. In a later stage, we deleted responses from our sample when they did not answer the basic attention questions correctly; however, this did not affect the payment of this small amount. We paid all the respondents for the following two reasons: first, due to the small task, the payment itself covers the minimal time at a rate of about US $12 per hour. However, and more importantly, being rejected might have a substantially stronger negative effect for the MTurk workers as being rejected for a single task can influence their worker rating and therefore, they might potentially miss out on other and more valuable HITs. Additionally, answering a questionnaire in a “successful” way is likely not a good criterion for task performance in other MTurk tasks. Second, paying all the respondents justifies the use of all the data obtained, including answers from respondents that, for example, failed the attention questions. Aronow, Baron, and Pinson (Citation2019) cautiously noted that dropping cases that fail attentions checks may systematically distort results during the analysis. Thus, comparing both samples with and without successful attention check allows for sensitivity testing.

After a small introduction, respondents were randomly assigned (using Qualtrics build-in randomizer) to one of eight groups based on the 2 × 2 × 2-design. Along with the presentation of the vignette, including the office picture, respondents were asked to rate the focal person (Stephanie or Eric) based on nine characteristics by use of a seven-point Likert scale (see: Measurement).

On a subsequent page, respondents were asked some attention check questions in which they were asked to remember exact details that concerned several elements of the description in the vignette. In total, four such questions were asked. For example, with respect to the treatments of our experiment, we asked respondents to remember for which kind of organization the focal person worked, where the true answers were embedded in a list of four options. Similar for the names of the target person, the two actual options were embedded in a randomized list of four names. We also asked additional attention questions on elements that did not vary across vignettes (see the Appendix for the full experiment design and measures). The questionnaire ended with asking for the respondent’s age, gender, and political identification (conservative/liberal).

This study was conducted following ethical requirements of the University of Hamburg.Footnote1 All participants were provided with full information. All materials and data are available on Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/g58ht/

Measurement

Given the literature that we built on, which consists of a combination on public servant stereotypes and on employee professionalism in the context of NWRR, we decided for measuring professional image by following two strategies. First, we include items that directly focus on professionalism. In doing so, we are able to directly compare our results with previous work on NWRR (Uhlmann et al. Citation2013)—relevant for Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, we can analyze the relationship between stereotypical associations toward public servant confirmation and the evaluation of professionalism (Hypothesis 3). Against this background, we included nine items, that had the following structure: “Based on the following information do you think [Stephanie or Eric] is …,” each time followed by a personal characteristic. Seven Likert-scale response options were provided, ranging from ‘Extremely unlikely’ (−3) to ‘Extremely likely’ (3). To probe perceived professionalism—based on the original study of Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013), we asked for the following two characteristics: professional (+) and competent (+). Internally consistency is high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). Second, we rely on recent studies on public servant stereotypes (de Boer Citation2020; Van de Walle Citation2004; Willems Citation2020) to test the effects of our experimental treatments on stereotypical associations that are relevant for public servants. As a result, we can test the extent to which our experimental treatments aggravate stereotypical associations, which relates to Hypotheses 1 and 3. These personal characteristics are: caring (+), dedicated (+), hardworking (+), helpful (+), corrupt (−), greedy (−), and lazy (−). They were selected based on the data and analysis from Willems (Citation2020), which shows that these are the most-occurring stereotypical associations for public servants in the US. Originally, we planned to conduct our main analysis based on one main construct including all nine items. However, a further post-hoc analysis—pinpointed by one of the reviewersFootnote2—and based on the argument for better face validity—showed that because of discriminant effects it is more informative to analyze the stereotype and professionalism items as separate constructs. Therefore, our further analysis makes a distinction between these two concepts and focusses on them as different dependent variables that focus on professionalism, and stereotype confirmation, respectively. The analysis based on all nine items combined is reported in the supplementary materials. A comparison between both analysis strategies reveals only minor differences.

We added a tenth item that probed for the level of NWRR in the picture as a manipulation check The item was formulated as “… has a lot of non-work related elements in the office?,” and was also answered using the same 7-point Likert-scale. As non-work role-referencing, in contrast to the other treatments in our experiment, was not verbally communicated in the vignette, it was necessary to test whether the picture indeed induced this difference. Hence, this question also functions as a manipulation check question.

Sample

In total, 2,029 respondents started the survey (and saw the vignette), of which 1,941 finished the survey and got paid. After evaluation of the quality control questions and the accurate recollection of information about the treatments from the vignettes, we retained 1,412 respondents for further analysis. Given the short vignette descriptions, we assume that people that did not remember the basic information, did not pay sufficient attention to the treatment information, or did not read the vignette at all.

In the Appendix we additionally analyze whether respondent drop-out—based on failing the attention questions—is related to treatment or control variables. Older people are less like to remember all vignette information (odds ratio = 1.02: p < 0.001). Moreover, people who received the picture with more non-work role-referencing are also more likely to answer at least one attention question wrongly (odds ratio = 1.54: p < 0.05), and were thus not included in the strict sample. An interpretation could be—based on the literature that we build on for Hypothesis 2—that due to the lower professional perception created by non-work role-referencing, respondents have potentially less interest in details about a person, or are cognitively less triggered (Gigerenzer Citation2008; Goldstein and Gigerenzer Citation2002). Or more likely, and inherent to random experiments, this is probably a randomness issue (Mutz, Pemantle, and Pham Citation2019).

Results of the analysis on the full data set—without deleting these respondents—are also reported in the online supplementary materials; as well as an additional robustness test on whether dropouts relate to treatment and control variables. These additional analyses shows that only a minimal effect of NWRR exists. We can assume that—because of the picture—this treatment was immediately noticed. However, the text-related treatments do not have an effect in this additional analysis, as we can assume that people did not pay (sufficient) attention to it. This justifies the approach to build our interpretations on a sample for which we can assume that respondents read the vignettes.

Results

The manipulation check for induced impression of non-work role referencing in the office picture suggest that the visual clues had indeed the intended effect (ANOVA test: df = 1,410; SS = 2,253; F = 884.7; p < 0.001). Moreover, from the total sample, 1,412 respondents answered all four attention questions correctly. The analysis reported here is based on this restricted sample of respondents for which we assumed they paid sufficient attention to the vignette. However, as excluding participants who failed the attention check might bias the results (Aronow, Baron, and Pinson Citation2019), we repeated the analysis utilizing the full sample (see the Appendix).

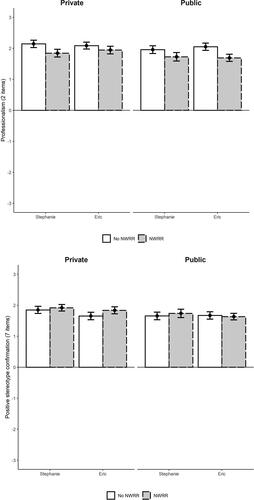

reports the mean values per treatment group along with group sizes, for (A) the professionalism items and (B) the stereotype confirmation items. reports the output of the OLS regressions with (A) professionalism and (B) positive stereotype conformation as dependent variables, while give insights into group differences and their significance based on 95%-confidence intervals.

Figure 1. (A) For the dependent variably ‘Professionalism’ (on Y-axis); Means and 95% confidence of group means showing difference for public (right) vs. private (left) sector employees (Treatment 1), reported with main split for non-work role-referencing (Treatment 2), and for gender (Treatment 3). (B) For the dependent variably ‘Stereotypes’ (on Y-axis); Means and 95% confidence of group means showing difference for public (right) vs. private (left) sector employees (Treatment 1), reported with main split for non-work role-referencing (Treatment 2), and for gender (Treatment 3).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables (A) professionalism and (B) positive stereotype confirmation for the eight treatment groups.

Table 2 (A). OLS regressions for professionalism, without (Model 1) and with control variables (Model 2).

Table 2 (B). OLS regressions for positive stereotype confirmation, without (Model 1) and with control variables (Model 2).

For sector difference, a public sector framing results in a small but significantly negative effect on the perceived professionalism ( β = −0.19; p < 0.05). That means that public sector workers are seen as less professional, which supports Hypothesis 1. However, we also refer to , giving a visual indication of this relatively small difference on a 7-point scale. Consistently, the positive stereotype confirmation (H1a) is slightly more negative for the public sector (; β = −0.19; p < 0.05). That is despite the fact that these associations were particularly identified for public servants (Willems Citation2020). Overall, our data supports Hypothesis 1, though with minimal effect size.

Furthermore, more non-work role-referencing is perceived as less professional, compared to no NWRR ( β = −0.30; p < 0.001) which is consistent with Hypothesis 2. In contrast, the positive stereotype confirmation shows no significant difference.

In sum, both Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported based on perceived professionalism, and partially based on the positive (and reversed negative) common associations made about public servants. Hence, despite the positive overall correlation between professionalism and stereotype confirmation (r = 0.661), the concepts show some discriminant validity for the treatments of this experiment. This distinction is elaborated in more detail in the discussion section.

As a control treatment, we also looked if a female versus a male name of the employee evoked differences for perceived professionalism (A) as well as stereotypical confirmation (B). ‘Eric’, compared to ‘Stephanie’, is perceived as less positive with respect to stereotype confirmation ( β = −0.20; p < 0.05). But there is no significant difference for professionalism. Moreover, intercepts for both dependent variables are significantly positive, meaning that respondents answered on average on the positive side of the 7-point Likert scale with 0 as the middle option.

reports the analyses with and without control variables. The main effects are robust. Furthermore, men are overall more negative about stereotypical associations, but not professionalism. The more conservative responders are with respect to political identification, the more negative they are about stereotypical associations and professionalism. A significant but negligibly small age effects is also visible, showing that older people are more positive.

Finally, the results in show that none of the interaction terms is significant. As a result, Hypothesis 3 is not supported by our data, neither for perceived professionalism nor for stereotype confirmation.

Discussion

This study offers four contributions to public administration research:

First, we add to the current research on public sector stereotypes by providing potential evidence for a potential bias on the micro-assessment of public employees’ professionalism. While we found a significantly lower level of professionalism attributed to public compared to private employees, the effect size is rather small. Hence, the results of this study stand in between studies providing evidence in favor of such biases (Hvidman Citation2019; Hvidman and Andersen Citation2016; Marvel Citation2015) and those failing to find differences (Jilke, van Dooren, and Rys Citation2018; Meier, Johnson, and An Citation2019). Furthermore, Meier, Johnson, and An (Citation2019) provide a direct replication of Hvidman and Andersen’s study (Citation2016) as they found no replicable results of a potential anti-public sector bias.

While there has been a long-standing debate about sector differences between public and private (Boyne Citation2002), research provides evidence that these differences may not be as pronounced as often assumed (Baarspul and Wilderom Citation2011; Frank and Lewis Citation2004) or that the research finds signs of convergence (Desmarais and Abord de Chatillon Citation2010). Against this background, our results show that for characteristics attributed to public servants (based on Willems Citation2020), only small differences exist for a public-sector framing versus a private sector framing. Therefore, we contribute to that stream of research by providing additional evidence and a micro approach to potential anti-public sector bias by examining the perceived professional image of employees. The results are also in line with Van de Walle (Citation2004), who argues that such stereotypes matter less at the specific micro-level, which was also addressed in the presented vignettes. Previous studies have often assumed a direct spillover effect of sector bias on employees’ image. However, we suggest that future research should attempt to decompose this effect to specific situations, specific characteristics, and specific causalities. Does a major bias occur during the general assessment of organizational performance in comparison to day-to-day micro interactions? Does the perception differ between various job types within the public sector (de Boer Citation2020)? As Bysted and Hansen (Citation2015) suggest, there may be more variance between different subsectors/industries and job types, than between the general public and private sector. Future research should contribute to our understanding of what the underlying processes of a potential public sector bias are. Against this background, we agree with Baarspul and Wilderom (Citation2011) who have called for an improvement of the theoretical underpinnings of supposed sector differences. Our results show sector differences with respect to professionalism, but not for characteristics particularly identified for public servants. Hence, in addition to documenting stereotypes and associations, further research remains necessary on what triggers particular cognitive associations.

Second, this study contributes to research on micro-management of workplaces. Our experimental study is able to replicate the findings of Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013), who found that the perceived professional image is negatively related to the amount of artifacts of non-work role referencing. Hence, we suggest that public organizations that have regular contact with clients should be aware of this effect on client’s perception. As non-work role referencing may also have a positive effect on employees’ psychological well-being, such personal artifacts should, however, not be banned per se from the workplace. However, future research is needed to confirm our findings as our results are to a degree contingent on the composition of our dependent variable (see robustness analysis in the supplementary materials).

Third, based on our post-hoc analysis, our data indicates a small gender bias effect on positive stereotypes. Female employees are more likely to be associated with positive traits, such as ‘dedicated’, ‘hardworking’, ‘not corrupt’, or ‘not greedy’. These results are in line with general research on gender-role stereotypes affecting the perception of leaders, politicians, and other groups (Alexander and Andersen Citation1993; Schneider and Bos Citation2014). However, this gender bias has no effect on the perception of competence and professionalism.

Fourth, while public sector employees have been assessed as less professional on average—and thereby reflecting assumed stereotypes—additional information on the state of the workplace shows no effect on the appraisal of professionalism. For example, despite a moderate correlation between professionalism and positive stereotype conformation for public servant characteristics, results are not consistent for both variables. This suggest that other types of information trigger assumptions about sector stereotypes and about professionalism. Consequently, we also did not find a stereotype-confirming effect of additive pieces of information. The results indicate that disconfirming information on professionalism indicated by non-work role referencing are ignored when assessing stereotypes. This study also follows scholars’ call for studies with higher statistical power. Due to the high level of statistical power in this study, we can be confident that there was no substantial effect that remained undetected due to a lack of observations. In summation, building upon earlier research in social psychology and public administration, we hypothesized that sector of employment (Hypothesis 1) and non-work role referencing (Hypothesis 2) have a negative effect on the professional reputation of employees as well as stereotypical associations. In addition and relying on theoretical and empirical insights on stereotypes and heuristic cognitive processes, we developed the hypothesis that both effects would aggravate each other as a result of the stereotype-confirmation processes (Hypothesis 3). However, the non-existent or very minimal main effects are likely that the reason that this particular context the stereotype-confirmation assumption cannot be verified with this study, despite the substantial statistical power of our sample. In contrast, our study and design contribute to a more nuanced debate on the scale and scope of a true anti-sector bias and the role of non-work role-referencing for professional reputations.

Limitations and further research

Stereotypes have often been studied from a general societal perspective, by focusing, for example, on ethnic and/or minority characteristics (Ashton and Esses Citation1999) or on gender-specific characteristics in the overall work force (e.g. Diekman, Eagly, and Kulesa Citation2002). Similarly, the overall public employee stereotype can be studied to develop a better understanding of stereotype thinking in the public sector context (Roberts Citation2005). Nevertheless, the current design, in which a nonspecific situation was used, can substantially be elaborated by taking a broader set of contextual factors into account. For example, the stereotypical “police officer,” is substantially different from the stereotypical “nurse,” “firefighter,” or “professor.” Nevertheless, the current argumentation—that stereotype confirmation and disconfirmation help in explaining the associative process for building professional reputations—would mean that stereotypes still, or even increasingly, play an important role in the contemporary workplace. However, better understanding of these processes also enables potentially changing stereotypes, and how they influence behavior, especially when it concerns negative and non-accurate stereotypes.

Despite the fact that stereotypes are often argued to be negative and that they should be avoided (Chan et al. Citation2012; Coffman Citation2014), the continuous fragmentation of needs and preferences in our society could mean that stereotypes will remain playing a crucial role; only the stereotypes themselves are changing. When we consider the ongoing trends of blurring boundaries between work and nonwork roles (Kossek, Noe, and DeMarr Citation1999; Nippert-Eng Citation1996; Olson-Buchanan and Boswell Citation2006), the content-related associations within existing stereotypes are likely changing over time. Therefore, there is theoretical value in applying a framework that takes a broader and more abstract approach. Based on the argumentation in this article, the results of this study and of earlier empirical studies could be framed as public employee stereotype confirmation or disconfirmation with a positive and negative effect, respectively, on professional reputation. However, characteristics of public employees can be very different in various contexts. Further research could, thus, include contextual elements that influence the context-specific stereotypes that are used. Furthermore, our data indicates that associated gender may play a role in the association of stereotypical traits. Future research should incorporate potential gender biases in their design to investigate this phenomenon in more detail.

While our data does not show a significant effect of non-work role referencing artifacts, there are various types of signals and cues from service interactions left to examine. There are only a few studies on such aspects of workplace configurations in a public sector context (Karl, Hall, and Peluchette Citation2013; Scheiberg Citation1990), however, studies from the private sector emphasize their relevance (Brill Citation1984; Brown and Zhu Citation2016; Wells Citation2000; Wells, Thelen, and Ruark Citation2007).

Conclusion

An employees’ professional image is an essential characteristic in service provisions as it sets the client’s expectations of professionalism and competence in public and private service encounters. The configuration of the workplace where service provisions take place plays a crucial role as a source for implicit signals and cues determining the perceived professional image. This study contributes to our knowledge of the effects of non-work role referencing artifacts. Drawing on social identity theory, we conducted a vignette experiment that investigated the effects of such artifacts while examining the potential effects of sector affiliation. The data showed no effect of non-work role referencing on the perceived professional image of employees, while there is a significant but small difference for public employees being perceived as less professional. Thus, our study cannot confirm the findings of Uhlmann et al. (Citation2013), while it contributes to the contested discourse about anti-public bias.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.7 MB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matthias Döring

Matthias Döring is assistant professor in public administration at the Department of Political Science and Public Management at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses on citizen-state interactions, street-level bureaucracy, service management, and digitalization.

Jurgen Willems

Jurgen Willems is professor Public Management & Governance the Vienna University of Economics and Business. He researches citizen participation and performance management in public and nonprofit organizations; and recent projects focus on public servant stereotypes, bureaucratic reputation, and pro-social behavior.

Notes

1 The University of Hamburg was the university where the second author was affiliated at the time of the data collection for this study.

2 We thank the anonymous reviewer for the suggestion to analyze the professionalism dimension separately, because of face validity: Stereotypical associations can be strongly related with professionalism but are not necessarily the same cognitive construct. The stereotype and professionalism constructs in this study correlate moderately (0.662). All nine items combined have a high-Cronbach alpha (0.88) and an integrated analysis—based on an index of all items—is reported in the online supplementary materials.

References

- Alexander, Deborah, and Kristi Andersen. 1993. “Gender as a Factor in the Attribution of Leadership Traits.” Political Research Quarterly 46 (3):527–45. doi: 10.1177/106591299304600305.

- Aronow, Peter M., Jonathon Baron, and Lauren Pinson. 2019. “A Note on Dropping Experimental Subjects Who Fail a Manipulation Check.” Political Analysis 27 (4):572–89. doi: 10.1017/pan.2019.5.

- Ashford, Susan J., and Gregory B. Northcraft. 1992. “Conveying More (or Less) than We Realize: The Role of Impression-Management in Feedback-Seeking.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 53 (3):310–34. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(92)90068-I.

- Ashton, Michael C., and Victoria M. Esses. 1999. “Stereotype Accuracy: Estimating the Academic Performance of Ethnic Groups.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25 (2):225–36. doi: 10.1177/0146167299025002008.

- Baarspul, Hayo C., and Celeste P. M. Wilderom. 2011. “Do Employees Behave Differently in Public- Vs Private-Sector Organizations?: A State-of-the-Art Review.” Public Management Review 13 (7):967–1002. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2011.589614.

- Barnes, Carolyn Y., and Julia R. Henly. 2018. “‘They Are Underpaid and Understaffed’: How Clients Interpret Encounters with Street-Level Bureaucrats.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28 (2): 165–181. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muy008.

- Bekerom, Petra van den., Joris van der Voet, and Johan Christensen. 2020. “Are Citizens More Negative about Failing Service Delivery by Public than Private Organizations? Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey Experiment.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31 (1):128–149.

- Bodenhausen, Galen V. 1990. “Stereotypes as Judgmental Heuristics: Evidence of Circadian Variations in Discrimination.” Psychological Science 1 (5):319–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00226.x.

- Bodenhausen, Galen V. 1993. “Emotions, Arousal, and Stereotypic Judgments: A Heuristic Model of Affect and Stereotyping.” Pp. 13–37 in Affect, Cognition, and Stereotyping: Interactive Processes in Group Perception, edited by Diane M. Mackie and David L. Hamilton. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Bodenhausen, Galen V., and C. N. Macrae. 1998. “Stereotype Activation and Inhibition.” Pp. 1–52 in Advances in Social Cognition, vol. 11, edited by S. Wyer Jr. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Bodenhausen, Galen V., Lori A. Sheppard, and Geoffrey P. Kramer. 1994. “Negative Affect and Social Judgment: The Differential Impact of Anger and Sadness.” European Journal of Social Psychology 24 (1):45–62. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420240104.

- Bodenhausen, Galen V., and Robert S. Wyer. 1985. “Effects of Stereotypes in Decision Making and Information-Processing Strategies.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48 (2):267–82. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.267.

- Boer, Noortje de. 2020. “How Do Citizens Assess Street‐Level Bureaucrats’ Warmth and Competence? A Typology and Test.” Public Administration Review 80 (4):532–42. . doi: 10.1111/puar.13217.

- Bohnet, Iris, Alexandra van Geen, and Max Bazerman. 2016. “When Performance Trumps Gender Bias: Joint vs. Separate Evaluation.” Management Science 62 (5):1225–34. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2015.2186.

- Bolino, Mark, Anthony Klotz, and Denise Daniels. 2014. “The Impact of Impression Management over Time.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 29 (3):266–84. doi: 10.1108/JMP-10-2012-0290.

- Boyne, George A. 2002. “Public and Private Management: What’s the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies 39 (1):97–122. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00284.

- Brill, Michael. 1984. Using Office Design to Increase Productivity. Buffalo, NY: Workplace Design and Productivity.

- Brown, Graham, and Helena Zhu. 2016. “‘My Workspace, Not Yours’: The Impact of Psychological Ownership and Territoriality in Organizations.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 48 (December):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.08.001.

- Brown, T. J. 2006. “Identity, Intended Image, Construed Image, and Reputation: An Interdisciplinary Framework and Suggested Terminology.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2):99–106. doi: 10.1177/0092070305284969.

- Bysted, Rune, and Jesper Rosenberg Hansen. 2015. “Comparing Public and Private Sector Employees’ Innovative Behaviour: Understanding the Role of Job and Organizational Characteristics, Job Types, and Subsectors.” Public Management Review 17 (5):698–717. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.841977.

- Champely, Stephane. 2018. “Pwr: Basic Functions for Power Analysis. R Package Version 1.2‑2.”

- Chan, Wayne, Robert R. Mccrae, Filip De Fruyt, Lee Jussim, Corinna E. Löckenhoff, Marleen De Bolle, Paul T. Costa, Angelina R. Sutin, Anu Realo, Jüri Allik, et al. 2012. “Stereotypes of Age Differences in Personality Traits: Universal and Accurate?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103 (6):1050–66. doi: 10.1037/a0029712.

- Chen, Serena, Kimberly Duckworth, and Shelly Chaiken. 1999. “Motivated Heuristic and Systematic Processing.” Psychological Inquiry 10 (1):44–9. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1001_6.

- Coffman, Katherine Baldiga. 2014. “Evidence on Self-Stereotyping and the Contribution of Ideas.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (4):1625–60. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju023.

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. “Statistical Power Analysis for the Social Sciences.” Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Czopp, Alexander M. 2008. “When is a Compliment Not a Compliment? Evaluating Expressions of Positive Stereotypes.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2):413–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.12.007.

- Czopp, Alexander M., Aaron C. Kay, and Sapna Cheryan. 2015. “Positive Stereotypes Are Pervasive and Powerful.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 10 (4):451–63. doi: 10.1177/1745691615588091.

- Desmarais, Céline, and Emmanuel Abord de Chatillon. 2010. “Are There Still Differences between the Roles of Private and Public Sector Managers?1.” Public Management Review 12 (1):127–49. doi: 10.1080/14719030902817931.

- Diekman, Amanda B., Alice H. Eagly, and Patrick Kulesa. 2002. “Accuracy and Bias in Stereotypes about the Social and Political Attitudes of Women and Men.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 38 (3):268–82. doi: 10.1006/jesp.2001.1511.

- Donald, Ian. 1994. “Management and Change in Office Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 14 (1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80195-1.

- Druckman, James N., and Michael Parkin. 2005. “The Impact of Media Bias: How Editorial Slant Affects Voters.” The Journal of Politics 67 (4):1030–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00349.x.

- Dumas, Tracy L., and Jeffrey Sanchez-Burks. 2015. “The Professional, the Personal, and the Ideal Worker: Pressures and Objectives Shaping the Boundary between Life Domains.” Academy of Management Annals 9 (1):803–43. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2015.1028810.

- Elsbach, Kimberly D. 2004. “Interpreting Workplace Identities: The Role of Office Décor.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (1):99–128. doi: 10.1002/job.233.

- Feldman, Jack M. 1981. “Beyond Attribution Theory: Cognitive Processes in Performance Appraisal.” Journal of Applied Psychology 66 (2):127–48. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.66.2.127.

- Fisher, Gwenith G., Carrie A. Bulger, and Carlla S. Smith. 2009. “Beyond Work and Family: A Measure of Work/Nonwork Interference and Enhancement.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 14 (4):441–56. doi: 10.1037/a0016737.

- Frank, Sue A., and Gregory B. Lewis. 2004. “Government Employees: Working Hard or Hardly Working?” The American Review of Public Administration 34 (1):36–51. doi: 10.1177/0275074003258823.

- Furnham, Adrian, Pui Shuen Chan, and Emma Wilson. 2013. “What to Wear? The Influence of Attire on the Perceived Professionalism of Dentists and Lawyers.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (9):1838–50. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12136.

- Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2008. “Why Heuristics Work.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 3 (1):20–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00058.x.

- Goldstein, Daniel G., and Gerd Gigerenzer. 2002. “Models of Ecological Rationality: The Recognition Heuristic.” Psychological Review 109 (1):75–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.75.

- Grant, Sharon, and Toby Mizzi. 2014. “Body Weight Bias in Hiring Decisions: Identifying Explanatory Mechanisms.” Social Behavior and Personality 42 (3):353–70. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2014.42.3.353.

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., and Saroj Parasuraman. 1999. “Research on Work, Family, and Gender: Current Status and Future Directions.” Pp. 391–412 in Handbook of Gender and Work, edited by G. N. Powell. Sage Publications.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephan, Sebastian Jilke, Asmus Leth Olsen, and Lars Tummers. 2017. “Behavioral Public Administration: Combining Insights from Public Administration and Psychology.” Public Administration Review 77(1):45–56. doi: 10.1111/puar.12609.

- Habel, Johannes, Sascha Alavi, Christian Schmitz, Janina-Vanessa Schneider, and Jan Wieseke. 2016. “When Do Customers Get What They Expect? Understanding the Ambivalent Effects of Customers’ Service Expectations on Satisfaction.” Journal of Service Research 19 (4):361–79. doi: 10.1177/1094670516662350.

- Hoobler, Jenny M., Sandy J. Wayne, and Grace Lemmon. 2009. “Bosses’ Perceptions of Family-Work Conflict and Women’s Promotability: Glass Ceiling Effects.” Academy of Management Journal 52 (5):939–57. . doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.44633700.

- Hvidman, Ulrik. 2019. “‘Citizens’ Evaluations of the Public Sector: Evidence from Two Large-Scale Experiments.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 29 (2):255–67. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muy064.

- Hvidman, Ulrik, and Simon Calmar Andersen. 2016. “Perceptions of Public and Private Performance: Evidence from a Survey Experiment.” Public Administration Review 76 (1):111–20. doi: 10.1111/puar.12441.

- Jilke, Sebastian, Wouter van Dooren, and Sabine Rys. 2018. “Discrimination and Administrative Burden in Public Service Markets: Does a Public–Private Difference Exist?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28(3):423–39. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muy009.

- Karl, Katherine A., Leda McIntyre Hall, and Joy V. Peluchette. 2013. “City Employee Perceptions of the Impact of Dress and Appearance: You Are What You Wear.” Public Personnel Management 42 (3):452–70. doi: 10.1177/0091026013495772.

- Kay, Aaron C., Martin V. Day, Mark P. Zanna, and A. David Nussbaum. 2013. “The Insidious (and Ironic) Effects of Positive Stereotypes.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49 (2):287–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.11.003.

- Keh, Hean Tat, and Yi Xie. 2009. “Corporate Reputation and Customer Behavioral Intentions: The Roles of Trust, Identification and Commitment.” Industrial Marketing Management 38 (7):732–42. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.005.

- Kelman, Steven. 2007. “5 Public Administration and Organization Studies.” Academy of Management Annals 1 (1):225–67. doi: 10.5465/078559810.

- Kleijnen, Mirella, Ko de Ruyter, and Tor W. Andreassen. 2005. “Image Congruence and the Adoption of Service Innovations.” Journal of Service Research 7 (4):343–59. doi: 10.1177/1094670504273978.

- Korac, Sanja, Jörg Lindenmeier, and Iris Saliterer. 2020. “Attractiveness of Public Sector Employment at the Pre-Entry Level – A Hierarchical Model Approach and Analysis of Gender Effects.” Public Management Review 22 (2):206–33. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1582688.

- Kossek, EllenErnst, and Susan J. Lambert. 2004. Work and Life Integration: Organizational, Cultural, and Individual Perspectives. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Kossek, Ellen Ernst, Raymond A. Noe, and Beverly J. DeMarr. 1999. “Work-Family Role Synthesis: Individual and Organizational Determinants.” International Journal of Conflict Management 10 (2):102–29. doi: 10.1108/eb022820.

- Ladd, Jonathan McDonald, and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2009. “Exploiting a Rare Communication Shift to Document the Persuasive Power of the News Media.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (2):394–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00377.x.

- Marvel, John D. 2015. “Unconscious Bias in Citizens’ Evaluations of Public Sector Performance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (1):143–58. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muu053.

- Maxwell, Gillian A., and Marilyn McDougall. 2004. “Work – Life Balance: Exploring the Connections between Levels of Influence in the UK Public Sector.” Public Management Review 6 (3):377–93. . doi: 10.1080/1471903042000256547.

- Meier, Kenneth J., Austin P. Johnson, and Seung‐Ho An. 2019. “Perceptual Bias and Public Programs: The Case of the United States and Hospital Care.” Public Administration Review 79 (6):820–8. doi: 10.1111/puar.13067.

- Michelson, Grant, Ad van Iterson, and Kathryn Waddington. 2010. “Gossip in Organizations: Contexts, Consequences, and Controversies.” Group & Organization Management 35 (4):371–90. doi: 10.1177/1059601109360389.

- Morrow, Paula C., and Joe F. Goetz, Jr. 1988. “Professionalism as a Form of Work Commitment.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 32(1):92–111. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(88)90008-5.

- Mostafa, Rania B., Cristiana R. Lages, Haseeb A. Shabbir, and Des Thwaites. 2015. “Corporate Image: A Service Recovery Perspective.” Journal of Service Research 18 (4):468–83. doi: 10.1177/1094670515584146.

- Mutz, Diana C., Robin Pemantle, and Philip Pham. 2019. “The Perils of Balance Testing in Experimental Design: Messy Analyses of Clean Data.” The American Statistician 73 (1):32–42. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2017.1322143.

- Nguyen, Nha, and Gaston Leblanc. 2001. “Corporate Image and Corporate Reputation in Customers’ Retention Decisions in Services.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 8 (4):227–36. doi: 10.1016/S0969-6989(00)00029-1.

- Nippert-Eng, Christena. 1996. “Calendars and Keys: The Classification of ‘Home’ and ‘Work’.” Sociol Forum 11:563–82.

- Olson-Buchanan, Julie B., and Wendy R. Boswell. 2006. “Blurring Boundaries: Correlates of Integration and Segmentation between Work and Nonwork.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68 (3):432–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.006.

- Pino, Eloísa del., Inés Calzada, and José M. Díaz-Pulido. 2016. “Conceptualizing and Explaining Bureauphobia: Contours, Scope, and Determinants.” Public Administration Review 76(5):725–36. doi: 10.1111/puar.12570.

- Pratt, Michael G., and Kevin Corley. 2007. “Managing Multiple Organizational Identities: On Identity Ambiguity, Identity Conflict, and Members’ Reactions.” Pp. 99–118 in Identity and the Modern Organization, edited by Bartel Caroline A., Steven L. Blader, and Amy Wrzesniewski. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Raaphorst, Nadine, and Steven van de Walle. 2017. “A Signaling Perspective on Bureaucratic Encounters: How Public Officials Interpret Signals and Cues.” Social Policy & Administration 52(7):1367–78. doi: 10.1111/spol.12369.

- Rafaeli, Anat, and Michael G. Pratt. 1993. “Tailored Meanings: On the Meaning and Impact of Organizational Dress.” Academy of Management Review 18 (1):32–55. doi: 10.5465/amr.1993.3997506.

- Ritz, Adrian, and Christian Waldner. 2011. “Competing for Future Leaders: A Study of Attractiveness of Public Sector Organizations to Potential Job Applicants.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 31 (3):291–316. doi: 10.1177/0734371X11408703.

- Roberts, Laura Morgan. 2005. “Changing Faces: Professional Image Construction in Diverse Organizational Settings.” Academy of Management Review 30 (4):685–711. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.18378873.

- Scheiberg, Susan L. 1990. “Emotions on Display: The Personal Decoration of Work Space.” American Behavioral Scientist 33 (3):330–8. doi: 10.1177/0002764290033003007.

- Schneider, Monica C., and Angela L. Bos. 2014. “Measuring Stereotypes of Female Politicians.” Political Psychology 35 (2):245–66. doi: 10.1111/pops.12040.

- Sherman, Jeffrey W., and Gayle R. Bessenoff. 1999. “Stereotypes as Source-Monitoring Cues: On the Interaction between Episodic and Semantic Memory.” Psychological Science 10 (2):106–10. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00116.

- Simon, Herbert A. 1955. “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69(1):99. doi: 10.2307/1884852.

- Smith, Robert W., Jesse J. Chandler, and Norbert Schwarz. 2020. “Uniformity: The Effects of Organizational Attire on Judgments and Attributions.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 50 (5):299–312. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12660.

- Srivastava, Kavita, and Narendra K. Sharma. 2013. “Service Quality, Corporate Brand Image, and Switching Behavior: The Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention.” Services Marketing Quarterly 34 (4):274–91. doi: 10.1080/15332969.2013.827020.

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2000. “Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (3):224. doi: 10.2307/2695870.

- Stouffer, Samuel Andrew. 1955. Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties: A Cross-Section of the Nation Speaks Its Mind. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Sundstrom, Eric, and Irwin Altman. 1989. “Physical Environments and Work-Group Effectiveness.” Research in Organizational Behavior 11:175–209.

- Swartz, Teresa, and Dawn Iacobucci. 2000. Handbook of Services Marketing and Management. London: Sage.

- Tummers, Lars. 2019. “Public Sector Stereotypes.” In. Annual Meeting of the European Group of Public Administration, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1983. “Extensional versus Intuitive Reasoning: The Conjunction Fallacy in Probability Judgment.” Psychological Review 90 (4):293–315. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.90.4.293.

- Uhlmann, Eric Luis, Emily Heaphy, Susan J. Ashford, Luke Zhu, and Jeffrey Sanchez‐Burks. 2013. “Acting Professional: An Exploration of Culturally Bounded Norms against Nonwork Role Referencing.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (6):866–86. doi: 10.1002/job.1874.

- Van de Walle, Steven. 2004. “Context-Specific Images of the Archetypical Bureaucrat: Persistence and Diffusion of the Bureaucracy Stereotype.” Public Voices 7 (1):3–12. doi: 10.22140/pv.192.

- Walker, Richard M., Oliver James, and Gene A. Brewer. 2017. “Replication, Experiments and Knowledge in Public Management Research.” Public Management Review 19 (9):1221–34. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1282003.

- Wegener, Duane T., Jason K. Clark, and Richard E. Petty. 2006. “Not All Stereotyping is Created Equal: Differential Consequences of Thoughtful versus non-thoughtful stereotyping.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (1):42–59. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.42.

- Wells, Meredith M. 2000. “Office Clutter or Meaningful Personal Displays: The Role of Office Personalization in Employee and Organizational Well-Being.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (3):239–55. doi: 10.1006/jevp.1999.0166.

- Wells, Meredith M., Luke Thelen, and Jennifer Ruark. 2007. “Workspace Personalization and Organizational Culture: Does Your Workspace Reflect You or Your Company?” Environment and Behavior 39 (5):616–34. doi: 10.1177/0013916506295602.

- Willems, Jurgen. 2020. “Public Servant Stereotypes: It is Not (at) All about Being Lazy, Greedy and Corrupt.” Public Administration 98(4):807–23. doi: 10.1111/padm.12686.