Abstract

The focus of red tape research so far, has been on public organizations, their organizational rules, and on managers’ perceptions of red tape. In the literature, it is suggested that red tape research should focus more on red tape that can be considered as existing objectively and on the compliance burdens of stakeholders such as businesses and citizens. For this purpose, the current definitions of red tape are too narrow or hardly applicable in practice. In this present article, a proposal for the redefinition and reconceptualization of red tape based on microeconomic production theory is submitted. The proposed definition brings red tape theory closer to the administrative policy topics and is therefore a good starting point for researching them. It is likely to be well suited for identifying red tape from an economic perspective in case studies and to initiate rule removal and change. The definition might also be appropriate to provide respondents in empirical studies with a basis for their assessment of red tape.

Introduction

Over the last three decades, administrative research as well as administrative policyFootnote1 have dealt increasingly with the subject of red tape. The focus of red tape research so far has been on red tape in public organizations, which is triggered by organizational rules, and on managers’ red tape perceptions. By contrast, the focus in US congressional records and US newspaper articles has been on other topics. These include especially the compliance burdens devolving on other stakeholders, namely businesses and citizens, how red tape is created through government rules and regulations, and how it can be reduced (Kaufmann and Haans Citation2021). OECD reports show that these issues are also present in the administrative policies in other countries (OECD Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2010). Therefore, more research is recommended on these issues (Kaufmann and Haans Citation2021; with a focus on the burdens devolving on citizens Herd and Moynihan Citation2018, XIV).

In red tape research, two different views of red tape have developed. Pandey (Citation2021) labels them “economic benefit-cost view” and “psychological process view.” For the emergence of the different views, see Pandey, Pandey, and Van Ryzin (Citation2017). Good contrasting comparisons are provided by Campbell (Citation2019) and Pandey (Citation2021). According to them, in the economic benefit-cost view, the classification of rules as red tape is the result of an objective and rational analysis of the benefits of the rules, and of the costs caused by the rules. This view goes back to the fundamental work of Bozeman (Citation1993, Citation2000) on developing a red tape theory. From the outset, Bozeman differentiated between organizational red tape and stakeholder red tape (Bozeman Citation1993, 283–4). Most recently, he formulated the corresponding definitions as follows:

Organizational red tape: Rules, regulations, and procedures that remain in force and entail a compliance burden for the organization but make no contribution to achieving the rules’ functional objectives. (Bozeman Citation2012, 251).

Stakeholder red tape: Organizational rules, regulations, and procedures that remain in force and entail a compliance burden, but serve no objective valued by a given stakeholder group. (Bozeman Citation2012, 255).

The term “economic benefit-cost view” used by Pandey (Citation2021) could be understood as always involving a comparison of monetized benefits and costs, as is the case in the familiar method of benefit-cost analysis. This is indeed true for Bozeman's definitions, especially for his definition of “multidimensional red tape” that will be discussed later. However, concepts such as “green tape” (DeHart-Davis Citation2009, Citation2017) or “sludge” (Sunstein Citation2019, Citation2020; Thaler Citation2018) are also assigned to the economic benefit-cost view (George et al. Citation2021, 646). These concepts do not provide for a comparison of monetized benefits and costs. For the fundamental ontologically and epistemologically based distinction of the underlying view from the psychological process view (Pandey Citation2021, 262), it is irrelevant whether exactly such a comparison takes place. Rather, it is only a question of whether any economically rational analysis of cost, benefit, or other economic measures is carried out in order to decide whether there is red tape. Therefore, in order to avoid possible misunderstandings, instead of the term “economic benefit-cost view,” the somewhat broader term “economic decision view” will be used below.

In the psychological process view, red tape is a “socially constructed reality that is dependent on the individual’s social role” (Pandey and Marlowe Citation2015, 217). The red tape perception develops through a psychological process in which both cognitive and affective components play a role. The great importance of affective components has been impressively elaborated by Hattke, Hensel, and Kalucza (Citation2020). According to Pandey’s (Citation2021, 264) definitions based on the psychological process view, “bureaucratic red tape is comprised of negative perceptual assessments of compliance burden imposed by an organisation” or, more generally, “bureaucratic red tape is role-specific subjective experience of compliance burden imposed by an organisation.” This subjective experience is not shaped by the rules themselves, but by the features of the organization’s structure and procedures that they create (Pandey Citation2021, 264). These include, for example, formalization (Pandey and Scott Citation2002), hierarchy and centralization (Kaufmann, Borry, and DeHart-Davis Citation2019). Davis and Pink-Harper (Citation2016) identified the following three theses that have emerged regarding the development of red tape perception through psychological processes. According to the rationalization thesis, employees experiencing negative work outcomes may invoke red tape as a rationalization for this scenario and thus report more red tape (Pandey and Kingsley Citation2000). According to the cognitive dissonance thesis, employees who see a contradiction between negative emotions at work and minimal red tape may resolve it by assuming that there is more red tape (Pandey and Welch Citation2005). According to the attribution thesis, individual perceptions of red tape may be greater on the part those who view events as more externally controlled than by individuals who view events as more self-controlled (Scott and Pandey Citation2005). Davis and Pink-Harper (Citation2016) identified a further psychological factor. Using attribution theory, they argued that perceptions of red tape are also influenced by perceptions of rule-breaking by others in the organization, and demonstrated this using an experiment. All of this means that red tape perceptions of individuals may differ significantly from whether rules constitute red tape from an economic decision perspective. It could even be the case that red tape is perceived, but no rule can be found that can be classified as red tape from an economic decision perspective. Conversely, there may be rules that can be classified as red tape from an economic decision perspective but without red tape being perceived.

The economic decision view and the psychological process view differ significantly, but neither is superior to the other. Rather, each view is suitable for different purposes, so that both have their place in science. Pandey (Citation2021) correctly states the considerable significance of the psychological process view for human resource management in the public sector. Of course, if red tape affects work motivation, causes stress in the workplace, or influences employee behavior (e.g., by avoiding procedures associated with red tape), it is because of subjective perceived red tape. Leaders must therefore accept red tape perceptions as realities and deal with them appropriately. The possible effects of red tape on employees, the relevant factors influencing red tape perceptions, and possibilities for leaders to influence these perceptions under given rules can only be researched from a psychological perspective.

If red tape is perceived, the question is how to respond. For example, a modification of leadership behavior could be considered. Studies suggests that the perception of red tape can be reduced by transformational leadership behavior (Moynihan, Wright, and Pandey Citation2012; Van der Voet Citation2016) and that a social exchange with the supervisor (instead of an instrumental one) can counteract the loss of well-being caused by obstructive rules (Sauer and Weibel Citation2012). However, the priority should be to clarify whether rules can be identified as a possible (contributory) cause of the red tape perception. For example, George et al. (Citation2021), who found through a meta-analysis that internal red tape is more detrimental than externally imposed red tape, “encourage practitioners to analyze the rules, regulations, and procedures […] that they impose on their own organization critically, and ask whether these might actually induce red tape perceptions among employees. And, if so, they need to ask how these rules, regulations, and procedures can be made more functional for the task (and stakeholder) at hand” (648). For such detailed examination, the economic decision view is helpful.

Methodologically, this means that for a specific rule or set of interrelated rules, the effects for the organization and all stakeholders must be economically analyzed in detail. Based on this, an objective assessment must be made. Following Bozeman and Feeney (Citation2011), to research this “real red tape” (126), it is necessary to conduct what they describe under the term “clinical research on red tape” (126, 130). The necessary approach is different from the many empirical studies that initially referred to Bozeman’s definition of organizational red tape, but then measured how managers assessed the level of red tape on a scale. This method conforms well to the psychological process view, but not to the economic decision view.

One may argue that an analysis of the economic effects of rules cannot in fact be objective and rational, even if performed by an independent scientist not involved in rule enforcement or if representatives of all stakeholder groups are in consensus, because information is never complete, and assessors are never completely free of subjective attitudes. But the result can be considered sufficiently sound to decide whether the rule or the set of interrelated rules constitutes red tape in the sense of the objective concept and should thus be changed or eliminated. Accordingly, governments apply the economic decision view when pursuing a cutting red tape agenda. For example, the European Commission (Citation2017, 4) states that “better regulation,” the title of its cutting red tape agenda, “means designing EU policies and laws so that they achieve their objectives at minimum cost.” This clearly points to the economic decision view.

However, the economic decision view can also be useful for surveying red tape perceptions. This has been demonstrated by the many studies in which respondents were given a definition of red tape as the basis for their assessment of the level of red tape. Although this definition did not match Bozeman’s of organizational red tape (more on this later), it was usually a definition that is attributable to the economic decision view. This is also the case in Davis and Pink-Harper (Citation2016), who explicitly consider red tape perception as the result of a psychological process that they examine. There is no contradiction in this. The definition serves to establish a common understanding among respondents of the meaning of the term “red tape.” This concern is probably best supported by a definition based on an objective concept of red tape. Admittedly, the assessment of red tape is strongly determined by other influences, as evident from the results of the research on psychological processes. On the other hand, Feeney (Citation2012) has shown that it is not irrelevant for assessing red tape, whether respondents are given a red tape definition and, if so, which one.

This article focuses on how red tape can be redefined and reconceptualized, conforming to the economic decision view. To this end, the following section takes a critical look at matching definitions of red tape that are known from the literature. Subsequently, a new proposal is made and justified with the aid of microeconomic production theory.

Red tape definitions in critical analysis

Bozeman’s definitions of organizational red tape and stakeholder red tape were already mentioned at the beginning. Both definitions have a stringent requirement for a rule to constitute red tape. The rule must serve absolutely no legitimate purpose. Thus, no red tape exists as long as a rule contributes to the achievement of an objective, even if this contribution is disproportionately expensive (Bozeman Citation2000, 88, 104; Bozeman Citation2012, 251).

In many empirical studies, which initially referred to Bozeman’s definition of organizational red tape, those asked to assess the level of red tape in their organization on a scale of 0 to 10 were presented with a different definition to that of Bozeman as the basis for their assessment. In a survey conducted in 1993 under the auspices of the National Administrative Studies Project (NASP), it was worded as follows: “burdensome administrative rules and procedures that have negative effects on the organization’s effectiveness” (Rainey, Pandey, and Bozeman Citation1995, 574). This definition, which can also be categorized under the economic decision view, is less narrow than Bozeman’s definition of organizational red tape. It allows a rule that contributes to the achievement of an objective to constitute red tape, if the resources used for pursuing it (e.g., working hours) cannot be deployed elsewhere and thus, the effectiveness of the organization is impaired more than aided by the rule. This definition was also used in 2005 in the NASP-III survey (Feeney and Rainey Citation2010), as well as in later surveys (Chen Citation2012; Feeney Citation2012; Jacobsen and Jakobsen Citation2018; Kaufmann and Feeney Citation2014; Kaufmann, Taggart, and Bozeman Citation2019; Kaufmann and Tummers Citation2017; Van der Voet Citation2016; Van Eijk, Steen, and Torenvlied Citation2019; similarly Borry Citation2016; Feeney and Bozeman Citation2009; Kaufmann, Ingrams, and Jacobs Citation2021; Steijn and van der Voet Citation2019). For the NASP-II survey, which commenced in 2002, the word “effectiveness” was replaced by “performance” (DeHart-Davis and Pandey Citation2005). The terms “effectiveness” and “performance” are frequently used as synonyms in the literature (Selden and Sowa Citation2004, 396), but in fact “performance is a multidimensional construct that covers many concerns such as quality, efficiency, effectiveness, responsiveness, and equity” (Brewer and Walker Citation2010, 238, with reference to Boyne Citation2002; Carter, Klein, and Day Citation1992). Accordingly, the definition must be considered as even broader than the previous one. It was also used subsequently in further surveys (Hussain and Ahmad Citation2015; Kjeldsen and Hansen Citation2018; similarly Brewer and Walker Citation2010; Davis and Pink-Harper Citation2016; DeHart-Davis Citation2007; Torenvlied and Akkerman Citation2012; Tummers et al. Citation2016).

In an empirical study, Feeney (Citation2012) compared the original red tape measure, using the definition “burdensome administrative rules and procedures that have negative effects on the organization’s effectiveness,” with three other one-item red tape measures and found “that the question wording and the definitions provided in the red tape questionnaire items influence respondents’ assessments of organizational red tape” (440). The highest level of red tape was reported when respondents were not given a definition at all. This suggests that the definitions used are narrower than how respondents actually understand the concept of red tape.

During the 2010 Red Tape Research Workshop: Rethinking and Expanding the Study of Administrative Rules, which took place at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with the participation of many of the most important red tape scholars, there was agreement that Bozeman’s narrow definitions of red tape are limited in their applicability. Rules that have absolutely no benefit are hard to find. Rather, a rule should already be seen as red tape if it results in a disproportionate compliance burden. It was proposed that the most ineffective rules on a continuum of rule effectiveness be regarded as red tape, but it was left open at what point on this continuum red tape actually commences. In addition, it should be taken into account that rules should not only be considered in terms of efficiency and effectiveness but could also be used to achieve other public administration values such as transparency, accountability, equity, representation and fairness (Feeney, Moynihan, and Walker Citation2010, 4). At this point, it should be critically added that Bozeman’s definition of organizational red tape only takes into consideration the compliance burden of the organization. But the focus of government agendas for cutting red tape is the compliance burden of stakeholders outside the organization, which can also make a rule red tape. Whether Bozeman’s definition of stakeholder red tape should take the compliance burden of stakeholders outside the organization into consideration its wording does not clearly state.Footnote2

Redefining and reconceptualizing red tape is one of the points on the red tape research agenda and considered by participants of the aforementioned workshop (Feeney, Moynihan, and Walker Citation2010, 12). Bozeman and Feeney (Citation2011) subsequently outlined a multidimensional red tape concept, using the following definition:

Multidimensional red tape: Rules that remain in force and entail a compliance burden for the organization or its stakeholders, but that are ineffective with respect to at least some of the organization’s or the stakeholders’ objectives for the rules (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 46).

Shortly afterwards, Bozeman (Citation2012) presented a substantially different multidimensional red tape concept and discussed it in greater detail. He thus made another interesting contribution to the debate on redefining and reconceptualizing red tape. The definition which is worded more precisely and according to which red tape is clearly subject-dependent, is as follows:

Multidimensional red tape: Rules, regulations, and procedures that remain in force and entail a compliance burden for designated stakeholders but whose contribution to [achieving]Footnote3 stakeholders’ objectives or values is less than the compliance and implementation resources expended on the rule (Bozeman Citation2012, 257).

Bozeman (Citation2012, 258) himself points out that he does not necessarily mean monetary benefits and costs, since many benefits and costs cannot easily be monetized. This is sufficient for a theoretical construct to describe the rule-determined component of the psychological process that leads to a respondent’s perception of red tape. However, if red tape is to be objectively identified in a concrete practical case according to the economic decision view, non-monetizable benefits and costs may be an obstacle to an unambiguous result.

Finally, three newer scales for measuring red tape should be mentioned. The researchers in question used them to measure red tape perceptions without presenting a definition of red tape to the respondents. However, the provided interpretation of the measurement results gives an idea of what the scholars consider to be red tape from an objective perspective. The one-item measurement scale used in many studies as described above, also called the General Red Tape (GRT) scale, was contrasted by Borry (Citation2016) with the Three-Item Red Tape (TIRT) scale. The TIRT scale measures the extent to which policies and procedures in the respondent’s work division are perceived as burdensome, unnecessary, and ineffective. Borry derived the TIRT scale from Bozeman's definition of organizational red tape and a certain explanation of red tape as “a rule or set of rules that have for one reason or another proved ineffective and burdensome” (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 20). Van Loon et al. (Citation2016) presented a job-centered red tape measurement scale, consisting of two dimensions, namely the perceived lack of functionality and the perceived compliance burden, each measured with three questionnaire items. On this basis, the authors defined red tape as “a rule that is perceived to entail a high compliance burden and lacks functionality” (664). By contrast, “rules that have a high compliance burden but achieve the rules’ functional objective” are explicitly not qualified as red tape, but as “necessary bureaucracy” (644). For the consideration of citizen red tape, Hattke, Hensel, and Kalucza (Citation2020) have taken up this approach and placed administrative delay alongside the compliance burden as an alternative criterion for the existence of red tape. They distinguish between “delay red tape” and “burden red tape” and call it “strong red tape,” when both forms occur together (55). However, they also assume that administrative delay and administrative burden are “necessary bureaucracy,” if there is no rule dysfunctionality (55). This reveals a comparable narrowness in Bozeman’s definitions, by not taking into account that there could be alternative rules that would achieve the functional objective equally, but with a (significantly) lower compliance burden or administrative delay. In this case, the existing rules should also be considered red tape.

Redefinition of red tape

It was already mentioned at the beginning of this article that administrative policy has a stronger focus on stakeholders outside public organizations, such as businesses and citizens. For example, the European Commission’s agenda of “better regulation” aims to reduce all unnecessary regulatory burdens for citizens, public authorities and businesses, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (European Commission Citation2017, 3–6). In the interest of achieving greater relevance of public administration research, Kaufmann and Haans (Citation2021) recommend aligning research more closely to the topics of administrative policy. If this is to be pursued, a definition and conceptualization of red tape would be helpful, in which the compliance burdens of businesses and citizens are at least as important as compliance burdens within the public organization.

Below, a new proposal for the definition and conceptualization of red tape is presented. In the process, the definition of red tape is to: 1. see red tape as objective, as in Bozeman’s organizational red tape, but 2. be less narrow, 3. take compliance burdens of stakeholders into account and 4. in addition to objectives, also take values into consideration. In the section thereafter, it will be shown that the proposed definition can be justified with the aid of microeconomic production theory, and that this theory is also suitable for underpinning elements of red tape theory already described in the literature.

The new proposal for the definition of red tape starts from Bozeman’s definition of organizational red tape. However, in addition to the compliance burden imposed on the organization, that imposed on the stakeholders is also incorporated into the definition. This idea is already found in the definition of “multidimensional red tape” by Bozeman and Feeney (Citation2011, 46). Furthermore, the focus is extended from “the rules’ functional objectives” to all objectives and values (such as transparency, accountability, equity, representation, and fairness) that are legitimate. The definition can then be formulated as follows:

Red tape: Rules [, regulations, and procedures] that [remain in force and] entail a compliance burden for the organization or its stakeholders, but do not make any contribution to achieving a legitimate objective or value.

The term “compliance burden” adopted from Bozeman should not be confused with the term “administrative burden” used by Burden et al. (Citation2012, 742) in referring to “an individual’s experience of policy implementation as onerous,” by Herd and Moynihan (Citation2018, 22) in referring to “the learning, psychological, and compliance costs that citizens experience in their interactions with governments,” and by the OECD (Citation2014, 12) in referring to “costs of complying with information obligations stemming from government regulation.” Rather, the term “compliance burden” refers to “total resources actually expended in complying with a rule” (Bozeman Citation2000, 77; Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 38).

The words in brackets are not necessarily required. If we understand the term “rules” in its broadest sense, then all regulations and procedures are based on rules. A regulation or procedure cannot be red tape without the rule that it contains or is based upon, also being red tape. As red tape therefore always has its origin in rules, the definition can be based on them. In the literature too, only the term “rules” is used frequently, such as the title of the book Rules and Red Tape (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011) and the versions to be found in it of the definitions of organizational red tape (44), stakeholder red tape (44) and multidimensional red tape (46). The explicit naming of regulations and procedures, however, should be helpful in achieving the same understanding on the part of all readers, of what is covered by the definition. By “rules […] that remain in force,” Bozeman means rules that continue to be applied by somebody. Rules that are still in place but no longer applied by anyone do not create a compliance burden (Bozeman Citation1993, 280, 2000, 13). For this reason alone, they cannot be red tape according to the definition. Consequently, it is not necessary additionally to explicitly restrict the rules in the definition to those that remain in force.

However, the presented definition is only a provisional one, because it is still too narrow. It has been rightly pointed out that it is difficult to find rules that do not have any function or positive effect whatsoever (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 45–6; Feeney, Moynihan, and Walker Citation2010, 4; Pandey, Pandey, and Van Ryzin Citation2017, 221–2). Those rules that contribute to achieving a legitimate objective or value must then also be seen as red tape if they are inferior to the alternatives, i.e., if the same contribution could also be made with a lower compliance burden. If a rule triggers an additional compliance burden without any additional benefit, it is clearly pathological. This results in a broader definition of red tape as rules that entail a higher overall compliance burden for the organization and its stakeholders than an alternative that would make the same contribution to achieving certain legitimate objectives and values. Materially equivalent, but slightly easier to follow, the definition can be formulated as follows:

Red tape: Rules [, regulations, and procedures] that [remain in force and] entail a higher overall compliance burden for the organization and its stakeholders than is strictly necessary for achieving certain legitimate objectives and values.

In the red tape definition proposed here, a certain result is assumed to be desired. This result is a complex construct, because it can include the achievement of more than one objective and must also satisfy values such as transparency, accountability, equity, representation and fairness. Nevertheless, the red tape definition proposed here has a practical advantage over Bozeman’s multidimensional red tape definition. That is, in order to identify red tape, it is not necessary to monetize the benefits of the given result. Instead, it is sufficient to draw the conclusion that an alternative would lead to an equivalent result. Arriving at this assessment is much easier than monetizing the benefit of the result. Only the compliance burden of the rule or the set of interrelated rules is compared with the compliance burden of the alternative. For this comparison, it is usually relatively easy to obtain a sufficiently accurate result using economic methods, e.g., the cost estimation methods that are commonly used in regulatory impact assessments (e.g., OECD Citation2014).

There remains a limit to the definition that must be pointed out. The minimum compliance burden cannot be analytically derived from the objectives and values to be achieved. One can only look for possible alternatives that are equivalent to achieving the objectives and values, and then check whether these would entail a lower compliance burden. The more clearly red tape is present, the more obvious the alternatives are. Although certain principles, such as those from process management, may help, the identification of red tape is just as limited as the knowledge and ingenuity of the observer. If there is a possible alternative that would lead to an equivalent result as the existing rule or set of rules, but would entail a lower compliance burden, and the observer merely does not recognize it, he/she will not identify any red tape, even though there is some there. This is where the assumption of rationality simply reaches its bounds. However, the fact that false estimations are possible does not affect the reasonableness of the definition as such.

Conceptualization of red tape

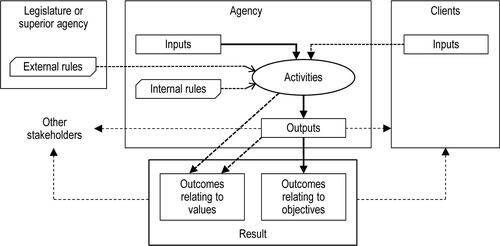

Regarding the conceptualization of red tape with the aid of microeconomic production theory, the production process of a government agency is viewed as follows, and as outlined in . The agency transforms several inputs into outputs. Certain outcomes are thus intended to be generated. Clients such as businesses or citizens (at the same time stakeholders of the agency) are involved in the production. In part, the outputs and outcomes serve the clients and in part, other stakeholders. If clients are involved as applicants for some decision or permission to do something in the production process, they are usually also recipients of it, while the application requirement may in fact be intended to protect the interests of other stakeholders. However, the participation can also result from a statutory obligation to provide information required for the production process, without the clients themselves deriving any benefit. The various outcomes are summarized below as the “result” of the production process. The clients do not have any influence over the design of the production process, which is determined by the agency through internal rules, taking into account external rules that are specified by the legislature or a superior agency. At times, the clients are offered various options for integration into the production process, such as being able to choose whether communication with the agency is on paper or electronic.

Let us take a look at some examples. If a motor vehicle is registered, at any rate in Germany, the client is involved in the production process in that he/she makes a registration application to the agency but has a car registration plate produced by some other body than the agency and receives the car license from the agency. For this purpose, he/she seeks out an agency and may have to wait a while. If he/she wishes to build a house and requires building permission to do so, he/she will submit an application with building plans to the agency. Whereas in the aforementioned cases, the agency becomes active at the instigation of a client, companies who have to provide data to a statistical office are involuntarily involved in the production process. Output in the form of statistics is not specifically available to the companies concerned, but rather to the general public. There are also many production processes in which the client belongs to the agency itself. Such an internal client includes, for instance, an employee of an agency who requests approval for a business trip and at a later point in time, reimbursement of the travel costs. In all the above cases, the agency implements external rules and fills any gaps with internal ones.

Depictions of the activities of a public organization in process models can also be found in the literature on public management and are used as a basis for assessing organizational performance (e.g., Van Dooren, Bouckaert, and Halligan Citation2015, 21; developed further by Zahradnik Citation2011). In these models, any inputs of clients (also representing stakeholder burdens) are usually not taken into account. For the analysis of red tape, however, they are relevant, because red tape, according to the definition developed above, not only exists when unnecessary compliance burdens are incurred in the organization, but also when they are incurred among stakeholders. In addition, in , outcomes relating to values have been added in order to emphasize that various degrees of transparency, accountability, equity, representation, fairness, etc. are inevitable part of the result of the production process of an agency.

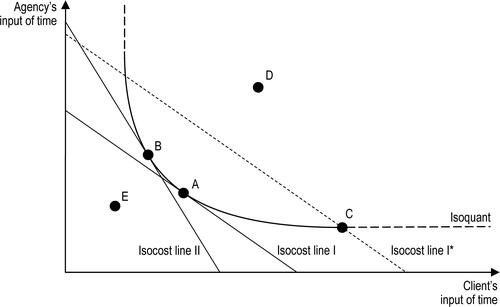

The main part of the inputs is in most cases the input of time, both for the agency as well as for a client. Based on the aforementioned considerations, the lowest-cost (cost-efficient) production of a specific result by both the agency’s input of time and the client’s, is shown in . The form of depiction is based on a model of production theory which has been around almost a century (Lloyd Citation2012) and has frequently been described in microeconomic textbooks (e.g., Pindyck and Rubinfeld Citation2018, 224–8, 252–6; Samuelson and Nordhaus Citation2010, 144–7). The model is also used in public management theory to explain the concept of production process efficiency in public organizations (De Borger and Kerstens Citation1995; Mühlenkamp Citation2003, 63; Van Dooren, Bouckaert, and Halligan Citation2010, 19). The difference in what follows is that here it is not both inputs that are contributed by the agency, as one of them is contributed by the client. This particular version of the model has already been used in the literature (Jakobsen and Andersen Citation2013; Ostrom Citation1996; Parks et al. Citation1981). Moreover, we do not consider outputs as constituting a result, as microeconomic production theory does for business firms, but rather, and appropriately for the public sector, the outcomes that finally matter. This takes into account that it can be red tape if a rule prescribes a certain output that is not needed to achieve the objectives, e.g., a decision as an output of an approval procedure if a less burdensome notification procedure would serve the objectives and values just as well.

The influence of external and internal rules is initially not taken into account at this point but will be addressed later. The restriction to two inputs permits a two-dimensional depiction that makes the model easier to understand. In principle, any number of different inputs could be considered in the model. With four or more inputs, however, it would no longer be possible to depict the model graphically.

It is assumed in the model that the agency is required to produce a specific result. This explicitly includes all outcomes, including those relating to public administration values. The specified result also entails the exclusion of unwanted side effects and minimum probabilities of production errors. The procedural safeguards that are necessary in order to achieve the specified result are part of the production process and are taken into account in the input of time in the model presented here.

Each possible design of the production process can be depicted in the diagram as an input combination. There are many possible input combinations, of which only a few are shown here as examples in the form of points. The boundary of the space of all input combinations that lead to the desired result is simplified in the model by a curved line. This line is referred to as an “isoquant” in microeconomics. The input combinations that lead to the desired result are those on or above the isoquant. With other input combinations, such as point E, producing the required result is not possible. The course of the isoquant is monotonic and convex, which means that the two inputs are imperfect substitutes. In many administrative processes in which clients are involved, there are different design options for the extent of client involvement. For example, the design of the process and the time required on both sides depends on whether a client has to visit the agency, whether he/she has to fill out and submit a form on paper, or whether he/she can do this digitally via the Internet. It also plays a role, whether the agency retrieves certain data from its archives, whether it receives them from another agency or whether the client has to provide them again. These examples show that the inputs of the agency and the client are not only comparative but can also be substitutive. The unbroken curved segment of the isoquant represents the input combinations where the quantity of one input cannot be reduced without having to increase the quantity of the other input. These input combinations are referred to as “technically efficient.” The input combinations on the dashed segments of the isoquant or above the isoquant, e.g., point D, are technically inefficient, entailing wasted time. The dashed segments of the isoquant that run parallel to the axes show that a minimum of input of time cannot be reduced either for the agency or the client.

An isocost line constitutes all input combinations that, with a given ratio between the costs of a unit of the client’s input of time, to the costs of a unit of the agency’s input of time, lead to the same overall costs. The gradient of the isocost line corresponds to the ratio between the cost of a unit of the client’s input of time and the cost of a unit of the agency’s input of time. With isocost line I, the agency’s time is more expensive than the client’s. Isocost line I*, which runs parallel, is based on the same cost ratio, but at a higher cost level. With this cost ratio, the input combination A, with which the isocost line I just touches the isoquant, has the lowest cost and is therefore cost-efficient.Footnote4 With isocost line II, another cost ratio is assumed, where the client’s time is more expensive than the agency’s. In this case, input combination B is cost-efficient. Input combination C would result in minimal costs for the agency but would only be cost-efficient if the client’s time did not cost anything.

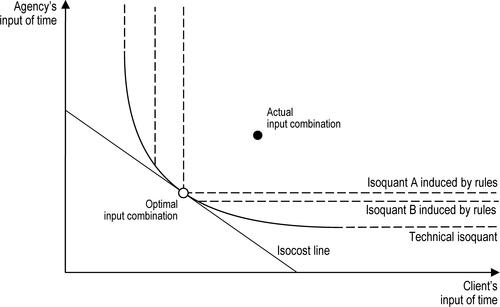

We now analyze how rules and red tape can be taken into account in this model. For this purpose, we assume that the result to be achieved is given, or that there is no disagreement about it between all stakeholders, i.e., legislature or superior agency, agency, client (see ). The deviating case will be addressed later. Furthermore, a differentiation is made between result-oriented and action-oriented rules. The former are those by means of which specifications are given for the result, but not for the production process. Action-oriented rules are those by means of which specifications are given for the production process. Result-oriented rules cannot be considered as red tape according to the concept presented here.

Action-oriented rules mean that any technically possible design of the production process that does not comply with these rules cannot be realized, as long as the rules are followed. Optimal action-oriented rules should lead to the optimal input combination. This corresponds to the “optimal control” that DeHart-Davis (Citation2009, Citation2017) describes as a prerequisite for effective rules, which she labels “green tape.” “Over-control,” she states, “is a catalyst for red tape […]. From the organizational perspective, over-control is inefficient and requires more constraint than necessary for achieving rule objectives” (DeHart-Davis Citation2017, 119).

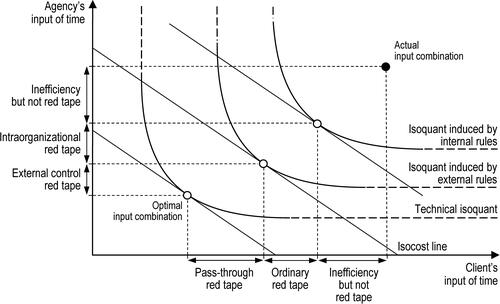

If all details are determined by optimal action-oriented rules, the unbroken segment of the isoquant is reduced to a point, namely that of the optimal input combination, shown in as isoquant A. Isoquant B stands for rules that are less restrictive and reduce the unbroken part of the isoquant to a segment on which a technical substitution of the inputs is still possible. If more time is spent by the agency or the client or by both, than would be necessary according to the technical possibilities and in compliance with the rules (designated as “actual input combination” in ), there is inefficiency. However, as this inefficiency is not caused by rules, there is no red tape.

Red tape exists when rules prevent the required result from being achieved cost-efficiently by the optimal input combination. There is an additional compliance burden for the agency or the client or both, without anything changing in the result specified in the model. There is therefore red tape according to the definition developed above.

It should be clarified that the isoquant induced by rules basically refers to the rules as they are to be understood and if they are applied correctly. Whoever applies a rule incorrectly and thus has an additional burden, may perceive red tape. But according to the concept presented here, there is objectively no red tape. However, if the agency communicates a rule incorrectly, then this communication can be considered in the same way as an additional rule set by the agency, which further limits the space of possible input combinations and can lead to red tape. If a rule is poorly formulated, so that it is to be understood differently than intended, this can also further limit the space of possible input combinations and lead to red tape.

In , the case is shown in which rules require time-consuming actions by the agency that are unnecessary for achieving the result. This leads to an upward shift in the isoquant by the amount of time wasted. All input combinations that lie between the two isoquants are impermissible according to the rules and are excluded from the space of technically possible input combinations leading to the required result. The isoquant induced by rules thus limits the space of input combinations that are technically possible and permissible according to the rules. The optimal input combination can no longer be achieved, and only one that is more burdensome for the agency. The following also applies here; if the time spent by the agency is above this isoquant, or the time spent by the client is on the right of this isoquant (actual input combination in ), there is inefficiency but no red tape.

Compatibility with existing elements of red tape theory

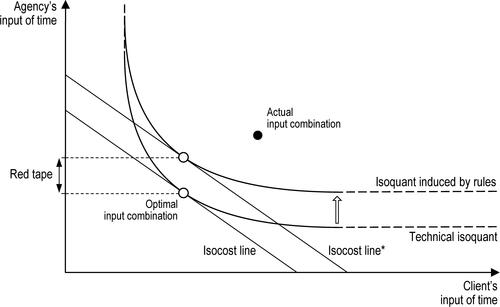

Below, it will be shown that the presented concept of red tape is compatible with elements of red tape theory that were introduced by Bozeman. In doing so, microeconomic production theory can contribute to underpinning Bozeman's considerations. initially shows the case of requiring time-consuming actions by both the agency and the client, which are unnecessary for achieving the result. The isoquant then shifts upwards and to the right. In addition, external rules and internal rules are analyzed separately in . Assuming that internal rules do not cancel out external rules, but can only have a more restrictive effect, internal rules that constitute red tape raise the isoquant to an even higher level than external rules that constitute red tape.

Various types of red tape can now be depicted on the X-axis and the Y-axis. We can refer to them in the terms introduced by Bozeman (Citation1993, 289–91). According to his typology, the origin and impact of red tape can be divided into internal and external, resulting in four types of red tape: “intraorganizational red tape” (internal origin, internal impact), “ordinary red tape” (internal origin, external impact), “external control red tape” (external origin, internal impact), and “pass-through red tape” (external origin, external impact). These terms and the underlying typology have also been described in later publications (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 141; Pandey and Kingsley Citation2000, 781; Scott and Pandey Citation2000, 618; Scott and Pandey Citation2005, 159) and used to classify red tape that has already been the subject of research (Feeney and Bozeman Citation2009; Hattke, Hensel, and Kalucza Citation2020; Kaufmann, Ingrams, and Jacobs Citation2021; Turaga and Bozeman Citation2005). The model presented here underpins Bozeman’s red tape typology.

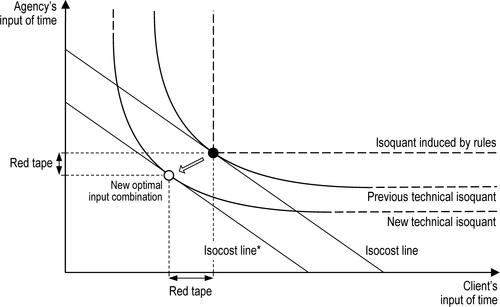

In addition, Bozeman differentiates between rules that constitute red tape from the outset (“rules born bad,” Bozeman Citation1993, 285), from rules that have only developed into red tape over the course of time (“good rules gone bad,” Bozeman Citation1993, 287). An example of this would be a rule in an examination regulation according to which students have to submit three bound paper copies of their thesis, together with a digital version, to the examination office. In fact, due to technological progress and computerization, all examiners have meanwhile switched to reading, commenting on and marking only the digital versions, so that the bound paper copies are arguably redundant. In this case, the rule has changed from a good one to a bad one, triggering a compliance burden that used to be offset by a benefit that no longer exists. Accordingly, the rule has become red tape.

The reasons for the development of a rule on red tape (last described in Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 54) can be attributed to the fact that either the technical isoquant, or the isoquant induced by rules, changes over time. In , an example of this is shown, with technical progress facilitating a production of the result at lower cost, for instance through progress in digitalization, but the rules do not yet permit this. The “change in the rule’s ecology” (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 54) shifts the technical isoquant to the left or downwards, but the isoquant induced by rules remains unchanged, meaning that red tape develops. The more the rules intervene and limit the space of the input combinations that are possible and lead to the desired result, the more a shift in the technical isoquant to the left or downwards results in the optimal input combination no longer being possible.

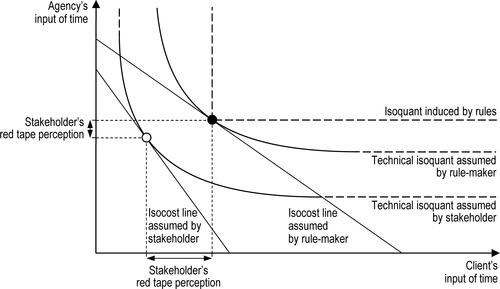

Bozeman’s definitions of stakeholder red tape and multidimensional red tape assume that red tape from a stakeholder perspective depends on what result the stakeholder desires. This was already described by Dwight Waldo (“one man’s red tape is another man’s system,” Citation1946, 399) and Herbert Kaufman (“one man’s red tape is another’s treasured procedural safeguard,” Citation1977, 4). Even if each stakeholder reflected on which objectives and values are legitimate and make them the basis of assessment, we would have to assume that different stakeholders may come to different conclusions. This phenomenon can be described as follows, at least in part, through the presented model.

If there are different assessments among stakeholders about what result is legitimate or what is technically required to achieve it, different isoquants are derived from this. For instance, an employee of the agency could consider a lower level of outcomes as sufficient, or not see the probability of side effects from agency activities, or estimate them to be smaller than they really are, so that he/she does not consider certain procedural safeguards to be necessary. People or organizations who or which submit an application to an agency may not consider information that is requested from them to be necessary, although it is in fact necessary. Irrespective of whether this is attributable to a wrong assessment of what is technically possible, or to a different assessment of what result is legitimate, an isoquant will result, on which the optimal input combination has a lower cost level. Furthermore, a stakeholder could assess the ratio of costs between a unit of the client’s input of time and a unit of the agency’s input of time differently to the rule-maker, which means that he/she assumes a different gradient of the isocost line, which can also influence the input combination that is perceived as ideal and can result in the perception of red tape. Both these influences on red tape from a stakeholder perspective are shown in .

Discussion and conclusion

Over the last few decades, many research papers have been written on the subject of red tape. Different definitions of red tape have formed a sound basis for this, but also revealed a number of weaknesses. For further research, a proposal for the redefinition and reconceptualization of red tape according to the economic decision view has been developed in the present paper. The issue was to find a definition that takes into account the compliance burden of the organization and all its stakeholders, but that is neither too narrow nor too broad, and differentiates pathological rules from other rules as clearly as possible. Through the conceptualization of red tape with the aid of microeconomic production theory, the proposed definition of red tape should now be clear and straightforward.

According to the concept presented, red tape is procedural inefficiency caused by bad rules. Let us compare this statement with the definition of red tape as “burdensome administrative rules and procedures that have negative effects on the organization's effectiveness,” with which the respondents in many surveys were presented. For this purpose, we have to distinguish between two cases. In the first, we assume that the organization's resources are limited. If limited resources are wasted through inefficiency, then the organization will have fewer resources left to use in pursuing its goals. Therefore, it can be assumed that the organization’s effectiveness is lower if red tape is present. In this first case, there is no contradiction between viewing red tape as inefficiency and viewing red tape as negative for the organization’s effectiveness. The advantage of viewing red tape as inefficiency, however, is that it focuses on the real problem, i.e., the unnecessary compliance burden. The loss in the organization’s effectiveness is just a consequence of this. In the second case, we assume that the organization’s resources are not completely limited. No limitation exists, for example, insofar as an agency charges cost-recovery fees for a process and clients cannot elude this process and the associated fees. Then, if bad rules result in unnecessarily high costs, the organization does not have to cover them itself, so that the inefficiency does not affect the organization's ability to pursue its goals. Thus, it can be assumed that inefficiency will not have any effect on the organization’s effectiveness. In this second case, the advantage of viewing red tape as inefficiency is that the bad rules are to be considered as red tape, while the criterion “negative effects on the organization's effectiveness” leads to the opposite result, which is not appropriate. Whether rules are red tape from an objective perspective should not depend on who has to bear the costs they cause. These reflections make it clear that it is more appropriate to link red tape to procedural inefficiency than to “negative effects on the organization’s effectiveness.”

Hattke, Hensel, and Kalucza (Citation2020) pursued the approach of considering administrative delay alongside administrative burden as a further criterion for constituting red tape. In the red tape definition presented here, administrative delay is not considered as a separate criterion. However, it is possible to interpret the meaning of the term “compliance burden” in the definition broadly enough to include “administrative delay” via the costs it triggers. Only if administrative delay has some adverse consequence for the client, can it be relevant to consider a rule as red tape. Such an adverse consequence could entail a financial loss, because the start of the client's action is delayed, because he/she has a long wait for the authority's approval. Adverse consequences can also be burdensome reactions of the person waiting, such as frustration or stress. In economic terms, these can be interpreted as “psychological costs” (Herd and Moynihan Citation2018, 23). Such costs can also be covered by the term “compliance burden” in the sense of the definition presented here. For clarification, it would be better not to define compliance burden as “total resources actually expended in complying with a rule” (Bozeman Citation2000, 77; Bozeman and Feeney Citation2011, 38) but rather as “total costs actually incurred by complying with a rule.” The red tape definition presented here is therefore also applicable to such approaches but with the restriction that costs of administrative delay, especially psychological costs, can hardly be measured in monetary terms.

A critical remaining question is whether a rule which imposes compliance burdens that are disproportionate to the objectives and values, should not also be considered as red tape. According to the definition presented here, whether or not the rule is in fact the real problem, is decisive. This is the case if the desired contribution to the defined objectives and values could also be achieved with a reduced compliance burden, but the rule continues to apply. Red tape then exists. If, on the other hand, the rule guarantees that the desired contribution to the defined objectives and values is achieved with the lowest possible compliance burden, but if this is nevertheless disproportionate to the objectives and values, then it is not the rule that is the problem, but retaining the objectives and values that could probably be described as pathological in this case.

What is presented in this article can make several contributions to red tape research and theory. First, it can extend red tape theory to better fit what administrative policy seeks to achieve, namely the reduction of compliance burdens not only of public authorities but especially of businesses and citizens (Kaufmann and Haans Citation2021; OECD Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2010). Although Bozeman already depicted in 1993 that the effects of red tape can be internal and external no definition has yet explicitly considered the total compliance burden inside and outside the organization as decisive for the existence of red tape from an objective view. However, this is precisely what the definition presented here does. It provides a view of red tape as objective as Bozeman's definition of organizational red tape, but in addition to the compliance burden of the organization it also takes into account the compliance burden of its stakeholders. Considering red tape as procedural inefficiency conforms conceptually to the objectives of red-tape-cutting agendas, such as the European Commission’s “Better Regulation”: the achievement of certain objectives at minimal cost (European Commission Citation2017, 4).

Second, the proposed definition is therefore a good starting point for research that addresses administrative policy topics. It is likely to be well suited to identifying red tape from an economic perspective in the context of case studies and to initiating rule removal and change. For this purpose, the proposed definition offers the following advantages over Bozeman's previous definitions: It is not as narrow as the definition of organizational red tape, according to which a rule is only red tape if it is completely useless which hardly ever occurs. A similar narrowness exists in the definition of stakeholder red tape, where a rule, in order to be considered red tape, must be completely useless with respect to the values of a given stakeholder group. Bozeman (Citation2012) had already responded to this weakness with his definition of multidimensional red tape. However, this definition does not cover the case in which the benefits of a rule are higher than the costs, but the costs are nevertheless unnecessarily high, because the same result could be achieved in a different way at lower cost. According to the definition of multidimensional red tape, this rule would not be red tape, but according to the definition proposed here, it would be. Furthermore, using the definition of multidimensional red tape to identify a rule as red tape in a concrete practical case requires monetization of the benefits, which is often not possible, certainly not with reasonable ease. With the definition proposed here, on the other hand, it is sufficient to assess that an alternative to the rule would lead to an equivalent result. Then, its benefit does not need to be monetized, but only the costs of the alternatives, so as to compare them.

Third, the definition may also contribute to the measurement of subjective red tape perceptions. In many studies in which red tape perceptions were measured, respondents were given a red tape definition that fits the economic decision view as a basis for their assessment. For this purpose, the definition that conforms best to what is understood as red tape in the administrative policy discussion present in newspapers might be more appropriate. For example, one could ask: “If red tape is defined as ‘rules and procedures that entail a higher overall compliance burden for the organization and its stakeholders than is strictly necessary for achieving the legitimate objectives and values’, how would you assess the level of red tape in this regulatory area?” The regulatory area to which this question refers should be clear beforehand or specified explicitly in the question. The extent to which this question can improve the measurement of red tape perceptions should be the subject of further research.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for the very valuable comments that improved an earlier version of this article, and to Dr. Brian Bloch for his comprehensive editing of the English.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefan Zahradnik

Stefan Zahradnik ([email protected]) is professor of public management at University of Applied Sciences Nordhausen, Germany. He received his doctorate from the Faculty of Economics and Business at Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany. His research interests include red tape, public performance management, and public sector accounting.

Notes

1 According to Christensen and Lægreid (Citation1998, 457), "administrative policy" should be understood as "ideas, goals and programmes aimed at influencing the formal organization, personnel, and working methods of public administration" pursued "by political and administrative leaders." See also Christensen, Lægreid, and Wise (Citation2002).

2 Bozeman did not always use the same wording for his definitions. In Bozeman and Feeney (Citation2011, 44), the compliance burden explicitly refers only to that of the organization.

3 The word “achieving” is missing in the original, but is probably meant by Bozeman, as in his definition of organizational red tape (2012, 251).

4 In accordance with the terminology used in the microeconomic model, the term “cost-efficient” is used here in distinction to the term “technically efficient,” regardless that outcomes are meant here by the result. It should be noted that in the process models used in the literature on public management as a basis for assessing organizational performance, efficiency related to outcomes is instead referred to as outcome efficiency (e.g., Glöckner and Mühlenkamp Citation2009, 403) or cost effectiveness (e.g., Van Dooren, Bouckaert, and Halligan Citation2015, 21).

References

- Borry, Erin L. 2016. “A New Measure of Red Tape: Introducing the Three-Item Red Tape (TIRT) Scale.” International Public Management Journal 19(4):573–93. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2016.1143421.

- Boyne, George A. 2002. “Concepts and Indicators of Local Authority Performance: An Evaluation of the Statutory Framework in England and Wales.” Public Money and Management 22(2):17–24. doi: 10.1111/1467-9302.00303.

- Bozeman, Barry. 1993. “A Theory of Government ‘Red Tape’.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 3(3):273–304. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037171.

- Bozeman, Barry. 2000. Bureaucracy and Red Tape. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bozeman, Barry. 2012. “Multidimensional Red Tape. A Theory Coda.” International Public Management Journal 15(3):245–65. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2012.725283.

- Bozeman, Barry, and Mary K. Feeney. 2011. Rules and Red Tape: A Prism for Public Administration Theory and Research. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Bozeman, Barry, and Patrick Scott. 1996. “Bureaucratic Red Tape and Formalization: Untangling Conceptual Knots.” The American Review of Public Administration 26(1):1–17. doi: 10.1177/027507409602600101.

- Brewer, Gene A., and Richard M. Walker. 2010. “The Impact of Red Tape on Governmental Performance: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20(1):233–57. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mun040.

- Burden, Barry C., David T. Canon, Kenneth R. Mayer, and Donald P. Moynihan. 2012. “The Effect of Administrative Burden on Bureaucratic Perception of Policies: Evidence from Election Administration.” Public Administration Review 72(5):741–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02600.x.

- Campbell, Jesse W. 2019. “Obtrusive, Obstinate and Conspicuous: Red Tape from a Heideggerian Perspective.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27(5):1657–72. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-11-2018-1584.

- Carter, Neil, Rudolf Klein, and Patricia Day. 1992. How Organizations Measure Success: The Use of Performance Indicators in Government. London, UK: Routledge.

- Chen, Chung-An. 2012. “Explaining the Difference of Work Attitudes between Public and Nonprofit Managers: The Views of Rule Constraints and Motivation Styles.” The American Review of Public Administration 42(4):437–60. doi: 10.1177/0275074011402192.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 1998. “Administrative Reform Policy: The Case of Norway.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 64(3):457–75. doi: 10.1177/002085239806400308.

- Christensen, Tom, Per Lægreid, and Lois R. Wise. 2002. “Transforming Administrative Policy.” Public Administration 80(1):153–78. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00298.

- Davis, Randall S., and Stephanie A. Pink-Harper. 2016. “Connecting Knowledge of Rule-Breaking and Perceived Red Tape: How Behavioral Attribution Influences Red Tape Perceptions.” Public Performance & Management Review 40(1):181–200. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2016.1214156.

- De Borger, Bruno, and Kristiaan Kerstens. 1995. “Produktiviteit en efficientie in de Belgische publieke sector: Situering van recent empirisch onderzoek [Productivity and Efficiency in the Belgian Public Sector: Situating of Recent Empirical Research].” Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management 40(2):101–31.

- DeHart-Davis, Leisha. 2007. “The Unbureaucratic Personality.” Public Administration Review 67(5):892–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00776.x.

- DeHart-Davis, Leisha. 2009. “Green Tape: A Theory of Effective Organizational Rules.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19(2):361–84. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mun004.

- DeHart-Davis, Leisha. 2017. Creating Effective Rules in Public Sector Organizations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- DeHart-Davis, Leisha, and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2005. “Red Tape and Public Employees: Does Perceived Rule Dysfunction Alienate Managers?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15(1):133–48. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui007.

- European Commission. 2017. “Commission Staff Working Document, Better regulation Guidelines.” SWD(2017) 350 final, 7 July 2017.

- Feeney, Mary K. 2012. “Organizational Red Tape. ‘A Measurement Experiment.’” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22(3):427–44. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus002.

- Feeney, Mary K., and Barry Bozeman. 2009. “Stakeholder Red Tape: Comparing Perceptions of Public Managers and Their Private Consultants.” Public Administration Review 69(4):710–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02019.x.

- Feeney, Mary K., Donald P. Moynihan, and Richard M. Walker. 2010. “Rethinking and Expanding the Study of Administrative Rules: Report of the 2010 Red Tape Research Workshop.” SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3508167.

- Feeney, Mary K., and Hal G. Rainey. 2010. “Personnel Flexibility and Red Tape in Public and Nonprofit Organizations: Distinctions Due to Institutional and Political Accountability.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20(4):801–26. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mup027.

- George, Bert, Sanjay K. Pandey, Bram Steijn, Adelien Decramer, and Mieke Audenaert. 2021. “Red Tape, Organizational Performance, and Employee Outcomes: Meta-Analysis, Meta-Regression, and Research Agenda.” Public Administration Review 81(4):638–51. doi: 10.1111/puar.13327.

- Glöckner, Andreas, and Holger Mühlenkamp. 2009. “Die Kommunale Finanzkontrolle. Eine Darstellung und Analyse des Systems zur finanziellen Kontrolle von Kommunen [Municipal Financial Control. A Presentation and Analysis of the System of Financial Control of Municipalities].” Zeitschrift für Planung & Unternehmenssteuerung 19(4):397–420. doi: 10.1007/s00187-008-0065-0.

- Hattke, Fabian, David Hensel, and Janne Kalucza. 2020. “Emotional Responses to Bureaucratic Red Tape.” Public Administration Review 80(1):53–63. doi: 10.1111/puar.13116.

- Herd, Pamela, and Donald P. Moynihan. 2018. Administrative Burden. Policymaking by Other Means. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hussain, Syed Bashir, and Ijaz Ahmad. 2015. “Public Service Motivation: Incidence and Antecedents in Pakistan.” International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 6(10):1354–73.

- Jacobsen, Christian Bøtcher, and Mads Leth Jakobsen. 2018. “Perceived Organizational Red Tape and Organizational Performance in Public Services.” Public Administration Review 78(1):24–36. doi: 10.1111/puar.12817.

- Jakobsen, Morten, and Simon Calmar Andersen. 2013. “Coproduction and Equity in Public Service Delivery.” Public Administration Review 73(5):704–13. doi: 10.1111/puar.12094.

- Kaufman, Herbert. 1977. Red Tape, Its Origins, Uses, and Abuses. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, Erin L. Borry, and Leisha DeHart-Davis. 2019. “More than Pathological Formalization: Understanding Organizational Structure and Red Tape.” Public Administration Review 79(2):236–45. doi: 10.1111/puar.12958.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, and Mary K. Feeney. 2014. “Beyond the Rules: The Effect of Outcome Favourability on Red Tape Perceptions.” Public Administration 92(1):178–91. doi: 10.1111/padm.12049.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, and Richard F. J. Haans. 2021. “Understanding the Meaning of Concepts across Domains through Collocation Analysis: An Application to the Study of Red Tape.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31(1):218–33. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muaa020.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, Alex Ingrams, and Daan Jacobs. 2021. “Being Consistent Matters: Experimental Evidence on the Effect of Rule Consistency on Citizen Red Tape.” The American Review of Public Administration 51(1):28–39. doi: 10.1177/0275074020954250.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, Gabal Taggart, and Barry Bozeman. 2019. “Administrative Delay, Red Tape, and Organizational Performance.” Public Performance & Management Review 42(3):529–53. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2018.1474770.

- Kaufmann, Wesley, and Lars Tummers. 2017. “The Negative Effect of Red Tape on Procedural Satisfaction.” Public Management Review 19(9):1311–27. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1210907.

- Kjeldsen, Anne Mette, and Jesper Rosenberg Hansen. 2018. “Sector Differences in the Public Service Motivation-Job Satisfaction Relationship: Exploring the Role of Organizational Characteristics.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 38(1):24–48. doi: 10.1177/0734371X16631605.

- Lloyd, Peter. 2012. “The Discovery of the Isoquant.” History of Political Economy 44(4):643–61. doi: 10.1215/00182702-1811370.

- Moynihan, Donald P., Bradley E. Wright, and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2012. “Working within Constraints: Can Transformational Leaders Alter the Experience of Red Tape?” International Public Management Journal 15(3):315–36. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2012.725318.

- Mühlenkamp, Holger. 2003. “Zum grundlegenden Verständnis einer Ökonomisierung des öffentlichen Sektors – Die Sicht eines Ökonomen [On the Fundamental Understanding of an Economization of the Public Sector – An Economist’s View].” Pp. 47–73 in Die Ökonomisierung des öffentlichen Sektors – Instrumente und Trends, edited by Jens Harms and Christoph Reichard. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- OECD. 2003. From Red Tape to Smart Tape. Administrative Simplification in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264100688-en.

- OECD. 2006. Cutting Red Tape. National Strategies for Administrative Simplification. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264029798-en.

- OECD. 2010. Cutting Red Tape. Why Is Administrative Simplification So Complicated? Looking beyond 2010. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264089754-en.

- OECD. 2014. OECD Regulatory Compliance Cost Assessment Guide. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264209657-en.

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24(6):1073–87. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X.

- Pandey, Sanjay K. 2021. “The Psychological Process View of Bureaucratic Red Tape.” Pp. 260–75 in Research Handbook HRM in the Public Sector, edited by Eva Knies and Bram Steijn. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. doi: 10.4337/9781789906622.00028.

- Pandey, Sanjay K., and Gordon A. Kingsley. 2000. “Examining Red Tape in Public and Private Organizations: Alternative Explanations from a Social Psychological Model.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10(4):779–800. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024291.

- Pandey, Sanjay K., and Justin Marlowe. 2015. “Assessing Survey-Based Measurement of Personnel Red Tape with Anchoring Vignettes.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 35(3):215–37. doi: 10.1177/0734371X14531988.

- Pandey, Sanjay K., Sheela Pandey, and Gregg G. Van Ryzin. 2017. “Prospects for Experimental Approaches to Research on Bureaucratic Red Tape.” Pp. 219–43 in Experiments in Public Management Research, edited by Oliver James, Sebastian Jilke, and Gregg Van Ryzin. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316676912.011.

- Pandey, Sanjay K., and Patrick G. Scott. 2002. “Red Tape: A Review and Assessment of Concepts and Measures.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 12(4):553–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003547.

- Pandey, Sanjay K., and Eric W. Welch. 2005. “Beyond Stereotypes. A Multistage Model of Managerial Perceptions of Red Tape.” Administration & Society 37(5):542–75. doi: 10.1177/0095399705278594.

- Parks, Roger B., Paula C. Baker, Larry L. Kiser, Ronald J. Oakerson, Elinor Ostrom, Vincent Ostrom, Stephen L. Percy, Martha B. Vandivort, Gordon P. Whitaker, and Rick K. Wilson. 1981. “Consumers as Co-Producers of Public-Services – Some Economic and Institutional Considerations.” Policy Studies Journal 9(7):1001–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1981.tb01208.x.

- Pindyck, Robert S., and Daniel L. Rubinfeld. 2018. Microeconomics: Global Edition. 9th ed. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

- Rainey, Hal G., Sanjay K. Pandey, and Barry Bozeman. 1995. “Research Note: Public and Private Managers’ Perceptions of Red Tape.” Public Administration Review 55(6):567–74. doi: 10.2307/3110348.

- Samuelson, Paul A., and William D. Nordhaus. 2010. Economics. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Sauer, Harmonie, and Antoinette Weibel. 2012. “Formalisierung und Wohlbefinden am Arbeitsplatz: Neue Perspektive auf eine Kontroverse [Formalization and Employee Well-Being: New Perspective on a Controversy].” Pp. 1–41 in Steuerung durch Regeln, edited by Peter Conrad and Jochen Koch. Wiesbaden: Gabler. doi: 10.1007/978-3-8349-4349-1_1.

- Scott, Patrick G., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2000. “The Influence of Red Tape on Bureaucratic Behaviour: An Experimental Simulation.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 19(4):615–33. doi: 10.1002/1520-6688(200023)19:4<615::AID-PAM6>3.0.CO;2-U.

- Scott, Patrick G., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2005. “Red Tape and Public Service Motivation. Findings from a National Survey of Managers in State Health and Human Services Agencies.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 25(2):155–80. doi: 10.1177/0734371X04271526.

- Selden, Sally Coleman, and Jessica E. Sowa. 2004. “Testing a Multi-Dimensional Model of Organizational Performance: Prospects and Problems.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 14(3):395–416. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muh025.

- Steijn, Bram, and Joris van der Voet. 2019. “Relational Job Characteristics and Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees: When Prosocial Motivation and Red Tape Collide.” Public Administration 97(1):64–80. doi: 10.1111/padm.12352.

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2019. “Sludge and Ordeals.” Duke Law Journal 68:1843–83.

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2020. “Sludge Audits.” Behavioural Public Policy First view:1–20. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2019.32.

- Thaler, Richard H. 2018. “Nudge, Not Sludge.” Science 361(6401):431. doi: 10.1126/science.aau9241.

- Torenvlied, René, and Agnes Akkerman. 2012. “Effects of Managers’ Work Motivation and Networking Activity on Their Reported Levels of External Red Tape.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22(3):445–71. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur076.

- Tummers, Lars, Ulrike Weske, Robin Bouwman, and Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen. 2016. “The Impact of Red Tape on Citizen Satisfaction: An Experimental Study.” International Public Management Journal 19(3):320–41. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2015.1027800.

- Turaga, Rama Mohana R., and Barry Bozeman. 2005. “Red Tape and Public Managers’ Decision Making.” The American Review of Public Administration 35(4):363–79. doi: 10.1177/0275074005278503.

- Van der Voet, Joris. 2016. “Change Leadership and Public Sector Organizational Change: Examining the Interactions of Transformational Leadership Style and Red Tape.” The American Review of Public Administration 46(6):660–82. doi: 10.1177/0275074015574769.

- Van Dooren, Wouter, Geert Bouckaert, and John Halligan. 2010. Performance Management in the Public Sector. London: Routledge.

- Van Dooren, Wouter, Geert Bouckaert, and John Halligan. 2015. Performance Management in the Public Sector. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Van Eijk, Carola, Trui Steen, and René Torenvlied. 2019. “Public Professionals’ Engagement in Coproduction: The Impact of the Work Environment on Elderly Care Managers’ Perceptions on Collaboration with Client Councils.” The American Review of Public Administration 49(6):733–48. doi: 10.1177/0275074019840759.

- Van Loon, Nina M., Peter L. M. Leisink, Eva Knies, and Gene A. Brewer. 2016. “Red Tape: Developing and Validating a New Job-Centered Measure.” Public Administration Review 76(4):662–73. doi: 10.1111/puar.12569.

- Waldo, Dwight. 1946. “Government by Procedure.” Pp. 381–99 in Elements of Public Administration, edited by Fritz Morstein Marx. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Zahradnik, Stefan. 2011. “Prozessmodell und Bewertungskriterien für öffentliche Verwaltungen [Process Model and Evaluation Criteria for Public Administrations].” Verwaltung & Management 17(2):78–83. doi: 10.5771/0947-9856-2011-2-78.