Abstract

Disabled employees in the British public sector lodge more claims of discrimination at Employment Tribunals than their private sector counterparts, yet their claims are more likely to fail. We argue that this is because disabled employees in the British public sector are more aware of equality issues than their private sector counterparts, subjectively perceiving discrimination. Yet the policies and practices that result from representative bureaucracy and the equality duties found only in the public sector result in judges mostly finding that disability discrimination in the public sector has not occurred, compared to such discrimination in the private sector.

Introduction

There is more discrimination in employment in the British public sector than in the British private sector, as measured by judicial complaints. The latest statistics show that the public sector has a higher proportion of discrimination cases (28%) than their share of cases overall (17%) (BEIS Citation2020a). Moreover, this is a long-standing phenomenon (Harding et al. Citation2014); as far back as 1998, the public sector accounted for 38% of all discrimination cases, but only 23% of all cases (DTI Citation2002). Yet employment discrimination cases cover complaints on various grounds, such as gender, age, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation and religion and belief. This article focuses only on disability discrimination and seeks to uncover differences between the public and private sectors

Our research questions are as follows: first we examine the number of cases brought by those employed in the British public sector compared to those employed in the British private sector, overall and by gender. Second, we investigate the outcome of claims, again comparing the two sectors. To develop hypotheses, we draw on theories of representative bureaucracy using the concept of the impact of representative bureaucracy through extra-organizational institutions, such as laws, policies and regulations, to understand the differences between the sectors. To test the hypotheses, we analyze all disability Employment Tribunal claims lodged in England and Wales in the three calendar years 2015–2017.

In brief, we found that disabled employees in the public sector brought proportionately more claims than their private sector counterparts. We suggest that public sector disabled employees lodge more claims because they are more aware of equality issues due to passive representation and therefore, report more subjective discrimination. Yet we also found that claims brought by disabled claimants in the public sector were more likely to fail at Employment Tribunals than those brought in the private sector. We suggest that although disabled employees may be of the view that they have been the target of discrimination, the role of extra-organizational institutions in the form of policies and practices that result from increased representative bureaucracy, and differences in the form of the law between the two sectors, result in judges finding that disability discrimination, as legally defined, has taken place less often in the public sector compared to the private sector.

The plan of this article is as follows. First, we outline the context: disabled people’s employment, British disability discrimination law, the Employment Tribunal process and the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED). We next turn to current research on representative bureaucracy and subjective and objective discrimination which help frame our hypotheses. Then we set out our methodology and present our findings. We conclude by discussing some possible reasons for our findings, limitations and some future research avenues.

The context

Disabled people’s employment

Over 4.2 million disabled people aged 16–64 were in employment in the United Kingdom in 2019 and this equated to roughly half of disabled people (53.2%) compared with the employment of just over four out of five non-disabled people (81.8%), according to the Office of National Statistics. Furthermore, one in five working disabled people cited a mental health condition as the main cause of their disability (ONS Citation2019).

Moreover, disabled people are less highly educated and professionalized than non- disabled people. Only a quarter (24.9%) of disabled people aged 21 to 64 years had a degree or equivalent as their highest qualification, compared with 42.7% of non-disabled people in 2021. In addition, disabled people were almost three times as likely to have no qualifications (13.3%) than non-disabled people (4.6%) and working disabled people were less likely to work as managers, directors and senior officials or in professional occupations than working non-disabled people (ONS Citation2022).

Turning to sectoral differences: although in terms of absolute numbers there is a marked difference (800,000 disabled people were employed in the public sector compared to over 3.5 million in the private sector), the public and private sectors have similar proportions of workers (14% and 13% respectively) who reported being disabled (ONS Citation2019).

Indeed, the British public sector has a legacy of being open and receptive to the employment of disabled people (Roberts et al. Citation2004), reflecting the increasing attention paid to demographic diversity in the public sector (Lee and Zhang Citation2021). Also, disabled people working in the public sector have higher retention rates than disabled people working in the private sector (DWP Citation2019), while Hoque and Bacon (Citation2019) found that public and third sector employers were more likely to report that employing a disabled person was positive for their organization than private sector employers.

It should also be noted that public sector employees are more likely to be aware of their legal rights than their private sector counterparts. This is because union density is 52% in the public sector compared to 13% in the private sector (BEIS Citation2020b) and unions endeavor to make their members aware of their legal rights. Thus, they issue publications on legal rights; many workplace union representatives give advice to their members on legal rights and many unions, when seeking to recruit members, emphasize that the provision of legal advice is a key benefit, as is the provision of legal representation at an Employment Tribunal when a case meets a given threshold.Footnote1

Lockwood, Henderson, and Thornicroft (Citation2013: 144–5), examined cases brought by claimants with a mental health impairment (not a physical or sensory impairment) at Britain’s Employment Appeal Tribunal between 2005 and 2013 comparing the public and private sectors. They found over-representation of the public sector: “44% of cases were associated with private sector organizations compared to 51% that were linked to public sector organizations.” They also indicated that public sector claimants were more likely to succeed than those in the private sector. This was because claimant success was strongly associated with legal representation, with those in the public sector more able to access legal help through their trade unions or professional associations. We will examine disability discrimination claims and outcomes by sector, stemming from all types of impairment at first instance (the Employment Tribunal level) to see to what extent our findings support Lockwood et al. (Citation2013) finding in respect of mental health impairments at the appellate level.

Another key sectoral difference is the fact that the public sector is more feminized than the private sector. According to Meager et al. (Citation2002), white, male, better qualified, white-collar employees with permanent jobs are most aware of their rights; however, they are also least likely to experience discrimination at work. We will analyze disability claims by gender in the light of Meager et al. (Citation2002) contention, but before doing so, we outline disability legislation.

British disability legislation

We now summarize the legal provisions in respect of British disability discrimination. These are set out in the Equality Act 2010 and provide for the redress of discrimination on grounds of disability after such discrimination has occurred, whether in the public or private sectors, lodging a claim with an Employment Tribunal. This British approach, with the state providing a forum and setting the procedural rules in what Ford (Citation2018: 6) calls “privatised social justice,” depends on enforcement using the “self-service” approach (Dickens, Citation2012: 2). Accordingly, it depends on an individual having the knowledge to lodge a claim.

Claiming disability discrimination

The legislation only applies to a disabled person, but the legal definition of disability is not straightforward (Equality Act, s.6).

“A person (P) has a disability if -

a) P has a physical or mental impairment, and

b) the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on P’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.”Footnote2

An impairment is long term if it has lasted or is likely to last for at least 12 months.

To compound this complexity, there are seven possible types of disability discrimination: direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, failure to provide a reasonable adjustment, discrimination arising from a disability, harassment, victimization and associative discrimination and each of these six types have to be separately claimed. Direct discrimination claims and claims of discrimination arising from a disability are brought by those who argue that they have been directly discriminated, whereas indirect discrimination is the result of institutional criteria, provisions or practices that result in discrimination. Failure to provide a reasonable adjustment is alleged where the employer has failed to provide a reasonable adjustment for the disabled employee to ensure he/she is not at a substantial disadvantage compared to a non-disabled employee.

Adjustments include, for instance, shorter working hours, adjustments to physical premises, the provision of a reader for an employee with a visual impairment, enhanced supervision for an employee with learning impairments and reallocating some of a disabled employee’s duties to another person. Whether or not such adjustments are “reasonable” depend inter alia on the employer’s resources.

Harassment claims are where an individual has been harassed because of their disability. Victimization is where an individual has been adversely treated because they are bringing an Employment Tribunal claim or supporting a claim, for instance by giving evidence. In contrast associative disability discrimination is not claimed by a disabled person, but by a person who has been discriminated against because of their association with a disabled person, for instance as a carer and has therefore not been included in this study, which only covers claimants who consider that they are disabled.

The employment tribunal process

In short, disability discrimination law is not straightforward as noted above, and claimants also have to navigate their way through the Employment Tribunal process, which we now summarize.

First, before lodging the claim at an Employment Tribunal a claimant must notify the Advisory, Conciliation & Arbitration Service (ACAS) that he/she wishes to make a claim and give ACAS the opportunity to try to broker a voluntary, “early conciliation” settlement between the parties. As a result, only 7% of such notifications went to an Employment Tribunal hearing (ACAS Citation2021).Footnote3

The next step is for the claimant to submit a claim by means of a standard form (ET1). The respondent, that is the relevant employer, is then asked by the Employment Tribunal to respond, also by means of a standard form (ET3). Our analysis below will compare the number of cases lodged by public sector claimants with cases brought by private sector claimants.

After this a preliminary hearing is conducted in front of a judge, usually sitting alone. This can be held in private where a case management order is issued dealing, for instance, with the time needed for a full hearing and the witness statements required. The preliminary hearing must be held in public, however, where a preliminary issue is considered, such as a jurisdictional issue (ETS (Constitution & Rules of Procedure 2013 Schedule 1, Rule 53)).

Almost always in disability discrimination cases a preliminary hearing is held in public and often deals with the narrow legal time limit prescribed by law. Claimants have only three months minus one day after the act of discrimination, or a series of acts, to lodge a claim, although a judge has discretion to extend this time limit if it is “just and equitable” to do so (Equality Act 2010s.118 (1)).

An employer can challenge a claimant alleging that he/she does not meet the complex definition of disability and is thus not disabled. This matter can be decided by a judge at a preliminary hearing held in public, or alternatively this matter may be left to be determined at a full hearing. Even if claimants satisfy the definition of disability, however, employers can defend a claim if they can demonstrate that at the relevant time they had no knowledge of the claimant’s disability. Our analysis below will explore to what extent such challenges are made by employers, comparing the British public and private sectors.

If a claimant’s case has not been disposed at a preliminary hearing,Footnote4 the case can proceed to full hearing. At the full hearing, the judge is joined by two lay members, one drawn from an employee panel and the other drawn from an employer panel and they hear the evidence with witnesses being cross-examined. Again, this is complex both because of the provisions on the burden of proof, and because there are various types of discrimination which are not mutually exclusive but have to be separately claimed, proved and ruled upon. See above. So, for example, a claimant’s reasonable adjustment claim may succeed, but the direct discrimination claim may fail. Our analysis, below will explore the outcomes, comparing the British public and private sectors.

If any part of a claimant’s claim is successful compensation can be awarded both for material loss and injury to feelingsFootnote5. The median award in 2019/20 was £13,000 and the average £27,043 (Morton Fraser Citation2020).

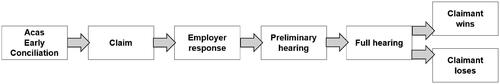

Finally, it should be noted that claimants can list other claims at the same time, for instance an unfair dismissal claim and/or a whistleblowing claim, as well as one or more disability discrimination claims. Evidence for all these claims is normally given at the same hearing, but are adjudicated separately and if found to be meritorious are separately compensated. Employment Tribunals, however, have no power to enforce their money judgments, so the claimant may not receive their award from the employer. is a diagram summarizing the Employment Tribunal process.

Figure 1. The Employment Tribunal Process.

Note: A claim can be withdrawn or settled, either privately or through ACAS, at any stage before a judgment is handed down.

The public sector equality duty

Having summarized the law relating to the redress of discrimination through an adjudicatory process which is reactive (that is after discrimination has occurred), we now turn to the law that requires organizations to be proactive to promote equality and thus avoid discrimination occurring in the first place. The United Kingdom, in contrast to most other European countries, is unusual in never having subjected public sector employees to a separate legal regime (Bach and Winchester Citation2003). Nevertheless, there is an exception in respect of Britain’s Equality Act 2010 s.149 as it imposes a Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) that requires public authorities to be proactive and to ensure that minority groups, including disabled people, are not disadvantaged (House of Lords Citation2009). Under the PSED there is a general duty to have “due regard” to eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimization and to advance equality of opportunity. According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s website,Footnote6 “[how] much regard is “due” will depend on the circumstances and …. the greater the relevance and potential impact for any group, the greater the regard required by the duty.”

In addition to this general duty, there are specific duties on certain public authorities to enable them to carry out the PSED more effectively (Hepple Citation2011: 134). In England and Wales, this requires public bodies to publish relevant, proportionate information demonstrating their compliance with the PSED and to set themselves specific, measurable equality objectives at least every four years. (Wales and Scotland impose additional specific duties).

It should be noted that “public authorities” include some bodies, such as universities, that are not counted as “public” by Britain’s Office of National Statistics, but are classified as public under the Equality Act and in this article’s analysis.

Representative bureaucracy and discrimination

Given the over representation of discrimination claims in the British public sector compared to the British private sector (BEIS Citation2020a) and some key sectoral differences, we use the theory of representative bureaucracy to explore these patterns and frame our research questions.

It is argued that when government bodies reflect (or represent) the population they serve, policy outcomes for the public will be improved (Mosher Citation1982) and that these improved outcomes for the public are derived from both passive and active representation (Meier Citation1993). Passive or descriptive representation focuses on how the demographic makeup of the organization reflects the diversity of a population (Naff and Capers Citation2014), whereas active representation concentrates on the actions of the bureaucrats that benefit minority groups (Mosher Citation1982). Where public servants proactively respond to their key demographic groups, their actions will result in more relevant public policy as they become more sensitive to the needs of the public due to shared experiences (Hong, Citation2021).

Traditionally theories of representative bureaucracy have been used to shed light on the impact of representative bureaucracy on public policies in western societies, focusing on gender (see Van Ryzin, Riccucci, and Li Citation2017; Meier and Nicholson-Crotty Citation2006) and ethnicity (see Atkins, Fertig, and Wilkins Citation2014), while Keiser and Soss (Citation1998) and Dhillon and Meier (Citation2022) have highlighted the influence of context and extra organizational institutions, such as the law, on bureaucratic discretion. Other studies have found theories of representative bureaucracy hold true in non-western contexts where improved infrastructure positively reinforces the influence of representative bureaucracy on student outcomes in respect of gender (Dhillon and Meier Citation2022).

More recently representative bureaucracy has been used to determine the impact of representation on employee inclusion, again with a particular focus on gender and ethnicity. While the evidence of the impact of representative bureaucracy on the public is largely uncontested, the evidence on the relationship between representative bureaucracy and employee inclusion is ambiguous. Lee (Citation2022) examining the impact of representative bureaucracy on ethnic minorities, found higher levels of ethnic minority supervisors did not lead to a decrease in racial discrimination at lower ranks in the organizational hierarchy. Lee (Citation2022) speculates that this is because organizational norms and pressures prevent ethnic minority supervisors acting in the interest of other ethnic minority employees. Krøtel, Ashworth, and Villadsen (Citation2019), looking at Danish local government, also found little support for a positive impact of representative bureaucracy on its employees; despite women being overrepresented in general management, there remained a glass ceiling in respect of senior management roles.

In contrast, Andrews and Ashworth (Citation2015) found a link between representation and inclusion for women and minority ethnic employees in the UK Civil Service and suggest that this is because representative organizations develop policies and procedures based on a wider set of perspectives, which result in improved policy outcomes for all, including employees. They submit that in a representative organization, minority groups feel that they are valued and have a stake in organizational life; therefore, they are treated with respect and dignity, reducing potential exposure to bullying and discrimination.

For representative bureaucracy to have the most impact on employee inclusion, a critical mass of senior minority bureaucrats with high levels of discretion is needed (Andrews and Ashworth Citation2015; Broadnax Citation2010; Krøtel et al. Citation2019). Studies, however, are less clear about what constitutes a critical mass and the seniority level at which the critical mass is needed (See Andrews, Ashworth, and Kenneth Citation2014; Broadnax Citation2010). Other factors, according to the literature, are a predisposition to active representation (Andrews and Ashworth, Citation2015), levels of political representation and organizational size (Krøtel et al. Citation2019).

We combine theories of representative bureaucracy with the distinction between objective and subjective discrimination. Hopkins (Citation1980:131) defined objective discrimination as discrimination “that is seen to exist by an observer” based on a set of predetermined criteria. Strict legal criteria need to be met to prove that objective discrimination has occurred. In contrast, subjective discrimination occurs when an individual, or a group, believe that they are the target of discrimination, but that belief is based on their subjective perceptions (Hopkins Citation1980). Incidences of subjective discrimination may result in an Employment Tribunal claim, but the claim may fail if it does not meet the criteria set out in law for objective discrimination. Also, Lee and Zhang (Citation2021) report that the public sector attracts people who value diversity and to whom the organization’s diversity reputation is important and that could also make them more aware of discrimination when it occurs. When employees become aware of breaches of their rights, they could then be more likely to make a claim.

Hopkins (Citation1980) found that individuals with higher social and economic status were more likely than those with a lower status to perceive discrimination and he suggests that higher status individuals could be more sensitized to more progressive attitudes about sex, race and age than lower status individuals. (This article has already noted that public sector employees are more highly educated and professionalized than private sector employees.) Furthermore, Park (Citation2021) albeit in the American context, found that public sector employees have higher levels of procedural justice perceptions than their private sector counterparts. If this holds for Britain, then public sector employees may be more likely to put in a legal claim if they consider that there has been discrimination.

H1: There will be a higher rate of disability discrimination cases brought by those in the public sector than those in the private sector.

We have already noted that more women than men work in the public sector compared to the private sector (ONS Citation2019) and greater numbers of identity groups can increase awareness of when rights are breached (Lee and Zhang Citation2021). Despite women being more likely to hold precarious contracts than men (De Henau et al., Citation2016) giving them lower job security, and thus reducing their likelihood of making a claim, they are more likely to experience discrimination than men (Manzi Citation2019). Furthermore, American research shows that support from colleagues increases the propensity to make a formal complaint (Park, Citation2021) and women overall experience more support from colleagues than men (Schieman Citation2006). The high levels of female representation (passive representation) in the British public sector, together with higher levels of discrimination and support from colleagues among women generally compared to men therefore lead us to hypothesize that more disabled women than disabled men report disability discrimination in the public sector.

H2: Women in the public sector will bring more disability discrimination cases than men in the public sector.

We have already commented that public sector claimants are on the whole more likely to be aware of legal issues than their private sector counterparts, wholly or mainly because of their greater propensity to unionize, and so may have only brought claims if they consider they meet the definition of disability. Therefore, we expect fewer challenges by public sector employers to an employee’s disability status compared to challenges by private sector employers.

Moreover, when passive and active representation are in place, then more policies and procedures that support inclusion are present, as noted above (Andrews and Ashworth, Citation2015). This factor, combined with the proactive PSED, should result in more formal routes for disability disclosure and should reduce stigma, which is a principal antecedent of disclosure (Santuzzi et al. Citation2019). Accordingly, we expect fewer challenges by public sector employers alleging that they had no knowledge of an employee’s disability compared to such challenges by private sector employers.

H3a: Disability discrimination claims brought by public sector employees will be less likely to be challenged on disability status than claims brought by private sector employees.

H3b: Disability discrimination claims brought by public sector employees will be less likely to be challenged on employer knowledge of disability than claims brought by private sector employees.

Research shows that active representation is linked to improved policies and procedures (Andrews and Ashworth Citation2015) and that these policies and procedures, in turn, improve the treatment of minority groups, suggesting a reduced chance of objective discrimination occurring. Furthermore, the PSED tends to result in more formal equality and diversity policies and procedures in the public sector than in the private sector (see Van Wanrooy et al. Citation2013, 117).

Therefore, given the high employment levels of disabled people in the public sector combined with the impact of active representation and the effect of the PSED on policies and procedures, we expect that discrimination claims will be less likely to be successful in the public sector compared to the private sector.

H4: Disability discrimination claims brought by public sector employees will be less likely to be successful at a full hearing than those brought by private sector employees.

Data and methods

Having briefly outlined the context, we now turn to our data and methods. Our data include all Employment Tribunal cases that went to a preliminary hearing or beyond and were resolved in the three calendar years 2015–17 inclusive in England and Wales and are thus a census, not a sample. Judgments of all disability discrimination cases in 2015 and 2016 were collected in hard copies by the first author at the Employment Tribunal register in Bury St Edmunds, England. In 2017, the Ministry of Justice placed Employment Tribunal judgments online, so judgments in disability discrimination cases in 2017 were located, downloaded and saved by the first author.

Cases where associative discrimination was claimed were removed as we wanted to focus on disabled claimants only, as were disability discrimination cases settled after a claim was lodged either by ACAS or privately, as details of any settlement are not available for public scrutiny.

All the cases that went to a preliminary hearing or beyond, and that were resolved by the end of 2017, were then subject to content analysis. A code book was developed based partly on the coding used in the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications (Harding et al. Citation2014). To assess the reliability of the coding, 100 cases were coded independently by the first and the third author. Interrater reliability was 97%. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

For the present study, the outcome of a claim was coded as a nominal variable, with categories “dismissed at preliminary hearing,” “withdrawn after preliminary hearing,” “dismissed at full hearing” and “successful at full hearing.” Sector was coded 0 for public sector and 1 for private sector. In this regard, we note that the PSED may partly apply to private sector organizations if they carry out a public sector function, for instance an organization that provides both prison guards (a public function) and car park guards (a private function). As we have no information about (or inquired into) the contracts held by such private sector organizations at the material time, we have classified them as private sector. Readers should also note that our categorization of the public sector includes universities as the PSED applies to universities.

In addition, we included variables measuring claimants’ gender (0 = man, 1 = woman), type of impairment (i.e., physical or sensory impairment: 1 = yes, 0 = no; mental or learning impairment: 1 = yes, 0 = no), and whether claimants had legal representation (1 = yes, 0 = no), as well as dummy variables for the six types of disability discrimination claims. Variables concerning other characteristics of the case were included as well, notably a count of other types of claims included in a case, and binary variables measuring whether the case included any procedural claims Footnote7 (1 = yes, 0 = no) or any other discrimination claims Footnote8 (1 = yes, 0 = no). Further, we coded whether any claims had been submitted out of time (1 = yes, 0 = no), whether the claimant’s disability status had been challenged (1 = yes, 0 = no) and whether the employer had claimed being unaware of the claimant’s disability status at the material time (1 = yes, 0 = no). Location of the Employment Tribunal was measured with binary variables for southeast England (incl. London), northern England, and other regions.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 concerned the number of cases brought compared to the number of employees and the gender composition in each sector. To address these hypotheses, we compared the cases in our data set with employment data provided by the Office of National Statistics (ONS Citation2022). For these analyses, we focus on the 667 cases in our data set that were brought in 2015 and 2016 ().Footnote9

Table 1. Disability cases compared to number of employees with disabilities, 2015–2016.

Hypotheses 3a and b concerned differences between public and private sector cases with regard to the challenges brought. For those cases where this information was available, we conducted independent samples t-tests to see whether there was a difference between cases brought in the public sector and in the private sector in this regard.

Hypothesis 4 concerned differences between the outcomes of disability discrimination claims in the public and private sectors. For these analyses we used data on claims from the years 2015–2017. Excluding claims with missing information,Footnote10 this left data on 934 claims. and show descriptive information on the characteristics and outcomes of these claims, both overall and for each sector. For the analysis, we used multinomial logistic regression to examine the likelihood of different possible outcomes, namely whether a claim was “dismissed at preliminary hearing,” “withdrawn after preliminary hearing,” or “successful at full hearing” as opposed to being “dismissed at full hearing” (the reference category). To take into account potential differences between different types of disability discrimination claims, we included dummy variables for the six types of disability discrimination claims, with direct discrimination as the reference category. In addition, to provide a stronger test of our hypothesis concerning the effects of sector, we controlled for other claimant and case characteristics for which data was available. shows the results.

Table 2. Characteristics of claimants and disability claims.

Table 3. Outcomes of disability discrimination claims.

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression results.

Findings

Our first hypothesis concerned differences in the rate of disability cases brought in the public and private sectors. shows the number of disabled employees and the number of disability discrimination cases by sector and gender for the years 2015 and 2016. Taking the average of the years 2015–2016,Footnote11 we see that there were 192.5 cases brought by private sector claimants, and 134.5 cases brought by public sector claimants; this corresponds to 6.8 cases per 100,000 employees in the private sector, and 15.8 cases per 100,000 employees in the public sector. In other words, there were twice as many cases in the public sector per 100,000 employees than in the private sector. This supported Hypothesis 1.

Further, we see that irrespective of sector, men were more likely than women to bring cases: there were 10.5 cases per 100,000 male employees compared to 7.9 cases per 100,000 female employees. The difference between male and female claimants was more pronounced in the public sector than in the private sector, although in the opposite direction than predicted by Hypothesis 2. In the private sector, women brought 5.6 cases per 100,000 employees while men brought 8.0 cases per 100,000 employees. In the public sector, women brought 12.3 cases per 100,000 employees, while men brought almost double the number of cases (24.2 cases per 100,000 employees). Thus Hypothesis 2 was rejected.

Hypotheses 3a and 3 b concerned differences between public and private sector cases with regard to the challenges brought by the employer to the claimant’s disability status and the employer’s knowledge of the claimant’s disability. We found that challenges concerning disability status were brought in 59% of the private sector cases compared to 48% of the public sector cases (t(286) = 1.917, p = 0.056). In other words, challenges to claimants’ disability status were somewhat more common in the private sector than in the public sector, although this tendency was only significant at the .1 level. Further, we found that employers claimed being unaware of claimants’ disability more often in private sector cases (49%) than in public sector cases (37%), a significant difference between sectors (t(283) = 2.041, p < .05). These findings provided support for Hypothesis 3b, but not for Hypothesis 3a.

Hypothesis 4 concerned the outcome of disability discrimination claims brought in the public and private sectors. shows the outcomes of disability discrimination claims overall and in each sector. We see that at the preliminary hearing, disability discrimination claims brought by private sector claimants were significantly more likely to be dismissed (16.6%) than claims brought by public sector claimants (7.2%; t(932) = 4.452, p < .001). At a full hearing, private sector claims were significantly less likely to be dismissed (57.0%) than public sector claims (69.3%; t(932) = 3.917, p < .001), and they were significantly more likely to be successful (19.3%) than public sector claims (13.1%; t(932) = 2.553, p < .05). There were no significant differences between sectors regarding the withdrawal of claims after a preliminary hearing.

This pattern remained when controlling for the effects of other variables in the multinomial logistic regression analyses (), i.e., compared to public sector claims, private sector claims were more likely to be dismissed at the preliminary hearing and more likely to be successful at a full hearing, as opposed to being dismissed at full hearing. This provides support for Hypothesis 4.

Discussion

A longstanding research agenda explores the differences between the public and private sectors in various aspects such as motivation, performance and absenteeism. More recently research has explored differing patterns of discrimination between the sectors. Our paper adds to this body of research by exploring differences between the sectors in respect of patterns of disability discrimination claims. Specifically, our objective was to examine the number of claims and their outcome in the public sector compared to the private sector through the lens of representative bureaucracy and, to that end, we developed and tested four hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that because of passive representative bureaucracy and the extra institutional environment in the form of the PSED and resultant policies, there would be more disability discrimination claims in the public sector compared to the private sector. As expected, the results showed that there were twice as many disability discrimination cases brought in the public sector per 100,000 employees than in the private sector. This is in line with Lockwood et al.’s findings in relation to claimants with mental health impairments at the appellate level, as they also found more public sector than private sector cases.

This could suggest that disability discrimination is more prevalent in the public sector, but instead we believe that the higher levels of representation of disabled employees, coupled with the impact of an extra-organizational institution such as the law, as seen in Keiser and Soss (Citation1998), results in more formal written policies and procedures in the public sector than in the private sector. In short, these formal policies result in public sector employees being more attuned to equality issues than their private sector comparators (Lee and Zhang Citation2021) and act as a signal to disabled public sector employees when events occur that could be perceived subjectively as discriminatory.

Furthermore, we have already noted that public sector employees are more likely to be unionized than their private sector counterparts and that unions provide members with information on their legal rights, increasing the ability to make a claim. Accordingly, we posit that the signaling effect of representative bureaucracy and the PSED, coupled with increased knowledge of their legal rights among employees at unionized workplaces (see Bacon and Hoque Citation2012, Citation2015) and higher prosocial motivation in the public sector (Marvel and Resh Citation2019), results in more disability discrimination cases being brought by public sector employees than by private sector employees. While Thaler and Sunstein (Citation2008) report that the form of the law can nudge employers to act in certain ways, we believe that the form of the law and representative bureaucracy can nudge public sector employees to act in certain ways through a signaling effect. We apply this signaling effect of representative bureaucracy, which has previously only been applied to women and ethnic minority employees (see Atkins et al. Citation2014; Meier and Nicholson-Crotty Citation2006; and Van Ryzin et al. Citation2017) for the first time to disabled employees.

Second, we tested the hypothesis that in respect of disability discrimination in the public sector, there would be more female claimants than male claimants given the higher passive representation of women in the public sector. This hypothesis was rejected. We found that men were more likely to bring disability discrimination cases than women in both sectors, but the difference was greater in the public sector. This pattern is repeated in other research where there are more male claimants than female claimants at Employment Tribunal overall (see BEIS Citation2020a).

Possible reasons for this could be that men tend to be more aware of their rights (Meager et al. Citation2002), as well as displaying higher levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy and risk taking than women (Bleidorn et al. Citation2016; Rolison et al., Citation2014). Therefore, men could be more willing to engage in the adversarial, and often stressful Employment Tribunal process. We propose, therefore, that the higher representation of women in the public sector does not result in more claims, because other factors such as self-esteem, self-efficacy and risk taking constrain their decision to lodge a claim at an Employment Tribunal. Furthermore, Naff and Capers (Citation2014) call for a nuanced exploration of descriptive bureaucracy to move beyond counting the number of identity groups in an organization (in this instance number of men and women) and instead consider identity construction and how identity is used in the organization.

Wider research suggests it is critical mass and seniority that are significant for representative bureaucracy to have an impact on employee inclusion (see Andrews et al. Citation2014; Broadnax Citation2010). Of course, public sector women are not a minority group, but nevertheless there are relatively few women in senior positions in the public sector, either in the civil service or across education, healthcare and the police (House of Commons Library Citation2021; Institute for Government Citation2021). Women are also more commonly employed on precarious contracts than men, increasing job insecurity (De Henau et al. Citation2016), reducing likelihood of taking a case. Accordingly, this lack of critical mass at senior levels as reported in Andrews et al. (Citation2014) and Broadnax (Citation2010) coupled with the low levels of power of women on precarious contracts could be an alternative or additional explanation for the rejection of our second hypothesis.

The next hypotheses concerned employer challenges to disability status and employer knowledge of the claimant’s disability. Analyses indicated that there were more challenges to disability status in the private sector than in the public sector, although this tendency was only significant at the .1 level. We also found that there were more challenges in respect of employers asserting no knowledge of a claimant’s disability by private sector employers compared to public sector employers. We propose that this occurs because there is more incidence of disability disclosure in the public sector than in the private sector. Again, we link this point to representative bureaucracy and the effect of the PSED through the role of extra organizational institutions, commenting that the public sector has more policies than the private sector which have the effect of reducing stigma, resulting in more incidence of disability disclosure (see Santuzzi et al. Citation2019). Where disability disclosure is governed by a formal policy, and where disability is less stigmatized because there are more disabled people present, then the employer will be more likely to be aware of disability status. This awareness will reduce employer challenges.

The fourth hypothesis tested was whether outcomes of disability discrimination claims differed by sector. In the analysis, we distinguished between outcomes at the preliminary hearing, withdrawal after a preliminary hearing, and outcomes at a full hearing. Overall claims in the private sector were more likely to be dismissed at a preliminary hearing than public sector claims. Employees in the private sector may be less aware of their rights as they are less professional, less highly educated, and less likely to be a union member (see above). Therefore, their disability claim may be more likely to be out of time, leading to dismissal at a preliminary hearing.

Concerning success at the full hearing, we found that private sector claims were significantly more likely to be successful at the full hearing than public sector claims. Therefore, while the number of cases brought are higher per 100,000 employees in the public sector than in the private sector, the likelihood of success at a full hearing is higher in the private sector. Our findings on the outcome of disability discrimination cases at the Employment Tribunal level, comparing the public and private sectors, are not congruent with Lockwood et al.’s findings in relation to the outcome of cases at the appellate level.

We believe the explanation is two-fold. First, as we have said, representative bureaucracy, impacted by extra-organizational institutions - the form of the law -, results in formal, written and often detailed policies and procedures that have “due regard” to disability and advance equality of opportunity. As such, these formal policies and procedures may contribute to reducing objective discrimination in the workplace, as legally defined and thus the failure of public sector claims at the full hearing. Second, the greater likelihood of success at the full hearing for the private sector could be a consequence of the greater number of cases being dismissed at a preliminary hearing in the private sector, as this process could weed out the weaker cases, bringing only the stronger cases to a full hearing.

We are cognizant, however that just because an Employment Tribunal has found that discrimination has not occurred, this does not necessarily mean that there was no discrimination, only that the legal tests for proving discrimination were not met. Drawing on work by Hopkins (Citation1980), any remedy that only considers objective discrimination is by its very nature partial as subjective discrimination remains untouched. As a result, the expectations of employees may be dashed, where their cases fail, a more common occurrence in the public sector than in the private sector. Employees bringing discrimination claims are the most likely to still be in employment at the time of the claim compared to claimants in non-discrimination claims (BEIS Citation2020a) and the impact of losing a claim could be detrimental to morale. Therefore, we suggest that it is not advisable to ignore perceptions of discrimination.

Limitations

As with all research on public and private sector differences, some limitations should be noted (Hansen, Løkke, and Sørensen Citation2019). While the use of archival data allowed us to avoid the biases associated with self-reports in survey studies (Jakobsen and Jensen Citation2015), it was not possible to include information on all variables that might be potentially relevant, such as workplace culture, prosocial motivation (Marvel and Resh Citation2019; Mastekaasa Citation2020), or the demographic composition of particular organizations. The key limitation in using archival data was the information contained in the case files (Blackham Citation2021). Some types of information were not collected systematically (e.g., employees’ rank, contractual status); for some variables, the information available did not allow meaningful interpretation and comparison (e.g., organizational size), and for some variables the case files were often incomplete (e.g., ethnicity, job role). While such limitations should not limit the usefulness of a paper (Hansen et al., Citation2019), to complement our study, we would encourage future studies using surveys or taking a mixed method approach to explore the role of these variables. In particular, where organization-level information on demographic composition is available, future studies should adopt a multilevel approach (i.e., cases nested in organizations and sectors) to take into account variation in representation between the organizations in each sector.

Conclusions

In conclusion, does representative bureaucracy reduce discrimination for employees inside an organization, a key question in the literature? The answer is both “yes” and “no.” Taking Employment Tribunal claims as a proxy for discrimination, this study finds that representative bureaucracy does not lead to fewer incidents of subjective or perceived discrimination, reflecting earlier work by Lee (Citation2022) on ethnicity and Krøtel et al. (Citation2019) on gender. We do find, however, some support for the argument that the presence of the policies and procedures, resulting from representative bureaucracy, combined with the PSED, reduce objective discrimination in line with research by Andrews and Ashworth (Citation2015) reinforcing the important role of extra organizational institutions. We, therefore, break new ground by extending the concept of representative bureaucracy to disabled employees and differentiating between subjective and objective discrimination.

We add, however, that we have not been able to ascertain the exact extent to which the presence of equality policies and procedures flow from representative bureaucracy and/or from the PSED and further research could perhaps investigate this angle. Further research could also distinguish between objective and subjective discrimination when assessing the impact of representative bureaucracy on inclusion.

Finally, we address the concerns raised by Atkins et al. (Citation2014) that much extant research lacks individual level data to analyze the behaviors of individuals. Using cases taken by individuals to Britain’s Employment Tribunals, we were able to examine the impact of representational bureaucracy on individual level actions of disabled people. Future research, however, based on in-depth interviews with disabled employees in both the public and private sectors could shed light on our findings.

Disclosure statement

There are no financial interests or benefits that have arisen as the direct application of this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura William

Laura William is an Associate Professor of Employment Relations and Equality at the University of Greenwich, London, UK. She is the director of the University’s Diversity Interest Group and researches on how the law is implemented in the workplace, particularly in respect of disability and whistle-blowing.

Birgit Pauksztat

Birgit Pauksztat is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Business Studies at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her research focuses on employees’ well-being, workplace interactions and ways of dealing with work-related problems.

Susan Corby

Susan Corby is Professor Emerita at the Business School, University of Greenwich, London, UK. Her research focuses on labor courts in the UK and abroad and on disability and gender rights in the workplace.

Notes

1 For instance, Unison, the largest public sector union, enumerates seven reasons to join. ‘Legal help’ is the first reason. https://join.unison.org.uk/?gclid=CjwKCAjwyo36BRAXEiwA24CwGQ_OsJ20nEMHU4JBzF8uiXrkE27b90xBsdpzdnRHzvDWQpQ6vj60RRoC2R8QAvD_BwE [accessed 24.8.20].

2 A non-exhaustive list of normal day to day activities is given in Guidance on the Definition of Disability 2011.

3 Conciliation by ACAS, as opposed to ‘early conciliation’ can be provided at any time up to the Employment Tribunal hearing.) If a settlement is not reached in early conciliation, the claim can proceed to an Employment Tribunal..

4 At a preliminary hearing, the Employment Judge may strike out a case on certain prescribed grounds (Rule 37), for instance because the claim is scandalous or vexatious or has no reasonable prospect of success. Alternatively, the judge may require the claimant to pay a deposit if he/she wishes to continue with the claim or an aspect of it if there is ’little reasonable prospect of success’ (Rule 39). The judge may also issue a default judgment because, for instance, the respondent has failed to provide a response (ET3)

5 Monetary compensation may include aggravated damages. These may apply where, for instance, the employer has been especially unpleasant or aggressive.

6 https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/public-sector-equality-duty-scotland/public-sector-equality-duty-faqs#:∼:text=The%20public%20sector%20equality%20duty%20was%20created%20by%20the%20Equality,belief%2C%20sex%20and%20sexual%20orientation. {accessed 7 March 2022)

7 Procedural claims included claims concerning whistleblowing, failure to provide written reason for dismissal, failure to provide written pay statement, failure to provide written statement of terms and conditions, detriment for trade union membership, redundancy for acting on a health & safety regulation, exercising a statutory right, breach of working time regulations, unfair dismissal, and breach of contract.

8 Other discrimination claims included claims concerning sex discrimination, race discrimination, age discrimination, religion or belief discrimination, sexual orientation discrimination and pregnancy or maternity discrimination.

9 Our data set only includes cases that were resolved by the end of 2017, i.e. cases that were not resolved at the end of 2017 were not included. Consequently, for 2017, our data set was less suitable for comparison with the ONS data with regard to the number of cases brought in that year.

10 In some judgments, certain information is not mentioned or redacted for privacy reasons (see also Blackham Citation2021).

11 The pattern was similar when analysing the data for each year separately.

References

- ACAS. 2021. Annual Report 2020–2021. London: Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service.

- Andrews, Rhys, and Rachel Ashworth. 2015. “Representation and Inclusion in Public Organizations: Evidence from the UK Civil Service.” Public Administration Review 75(2):279–88. doi: 10.1111/puar.12308.

- Andrews, Rhys, Rachel Ashworth, and J. Meier. Kenneth. 2014. “Representative Bureaucracy and Fire Service Performance.” International Public Management Journal 17(1):1–24. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.874253.

- Atkins, Danielle N., Angela Fertig, and Vicky Wilkins. 2014. “Connectedness and Expectations. How Minority Teachers Can Improve Educational Outcomes for Minority Students.” Public Management Review 16(4):503–26. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.841981.

- Bach, Stephen, and David Winchester. 2003. “Industrial Relation in the Public Sector.” in Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed, edited by Paul Edwards. Oxford: Blackwell

- Bacon, Nick, and Kim Hoque. 2012. “The Role and Impact of Trade Union Equality Representatives in Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 50(2):239–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8543.2011.00865.x.

- Bacon, Nick and Kim Hoque. 2015. “The Influence Of Trade Union Disability Champions On Employer Disability Policy And Practice”, Human Resource Management Journal 25(2):233–249.

- BEIS. 2020a. Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications: Findings from the 2018 Survey, Research Paper 2020/007. London: Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

- BEIS. 2020b. Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2019: Statistical Bulletin. London: Department of Business, Enterprise and Industrial Strategy.

- Blackham, Alysia. 2021. “Enforcing Rights in Employment Tribunals: Insights from Age Discrimination Claims in a New “Dataset.” Legal Studies 41(3):390–409. doi: 10.1017/lst.2021.11.

- Bleidorn, Wiebke, Ruben C. Arslan, Jaap J. A. Denissen, Peter J. Rentfrow, Jochen E. Gebauer, Jeff. Potter, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2016. “Age and Gender Differences in Self-Esteem-A Cross-Cultural Window.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111(3):396–410. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000078.

- Broadnax, WalterD. 2010. “Diversity in Public Organizations: A Work in Progress.” Public Administration Review 70:S177–S179. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02268.x.

- De Henau, Jerome, Susan Himmelweit, Zofia Łapniewska, and Diane Perrons. 2016. “Investing in the Care Economy: A Gender Analysis of Employment Stimulus in Seven OECD Countries.” A Report by the UK Women’s Budget Group Commissioned by the International Trade Union Confederation. Retrieved May 3, 2021 from (http://oro.open.ac.uk/50547/).

- Dhillon, Anita, and Kenneth J. Meier. 2022. “Representative Bureaucracy in Challenging Environments: Gender Representation, Education, and India.” International Public Management Journal 25(1):43–64. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2020.1802633.

- Dickens, Linda. 2012. “Fairer Workplaces: making Employment Rights Effective.” Pp. 205–88. In Making Employment Rights Effective, edited by L. Dickens. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- DTI. 2002. Findings from the 1998 Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications. Employment Relations Research Series 13. London: DTI.

- DWP. 2019. “Health In The Workplace: Patterns Of Sickness Absence, Employer Support And Employment Retention”. Accessed 31st March 2021: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/health-in-the-workplace-patterns-of-sickness-absence-employer-support-and-employment-retention.

- Ford, Morton. 2018. “Employment Tribunal Fees and the Rule of Law: R (Unison) v Lord Chancellor in the Supreme Court.” Industrial Law Journal 47(1):1–45.

- Hansen, Jesper Rosenberg, Ann-Kristina Løkke, and Kenneth Lykke Sørensen. 2019. “Long-Term Absenteeism from Work: Disentangling the Impact of Sector, Occupational Groups and Gender.” International Journal of Public Administration 42(8):628–41. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2018.1498104.

- Harding, Carrie, Shadi Ghezelayagh, Amy Busby, and Nick Coleman. 2014. Findings from the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications 2013. London: Business Innovation and Skills.

- Hepple, Bob. 2011. Equality: The New Legal Framework, Oxford: Hart.

- Hong, Sounman. 2021. “Representative Bureaucracy and Hierarchy: Interactions among Leadership, Middle-Level, and Street-Level Bureaucracy.” Public Management Review 23(9):1317–38. pp. DOI:.1080/14719037.2020.1743346 doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1743346.

- Hopkins, Anne H. 1980. “Perceptions of Employment Discrimination in the Public Sector.” Public Administration Review 40(2):131–7. doi: 10.2307/975623.

- Hoque, Kim and Nick Bacon. 2019. “Response To The Uk Government's Reforms Of Disability Confident Level 3”. Accessed 31 March 2021. https://www.disabilityatwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/[email protected].

- House of Commons Library. 2021. “Women in Politics and Public Life.” Retrieved March 24, 2021. (https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01250/).

- House of Lords. 2009. “Legislative Scrutiny: Equality Bill Twenty-sixth Report of Session 2008-09.” HL Paper 169 HC 736. Retrieved September 18, 2020. (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt200809/jtselect/jtrights/169/169.pdf).

- Institute for Government. 2021. “Gender Balance in the Civil Service.” Retrieved March 24, 2021. (https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/gender-balance-civil-service).

- Jakobsen, Morten, and Rasmus Jensen. 2015. “Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies.” International Public Management Journal 18(1):3–30. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.997906.

- Keiser, Lael, and Joe Soss. 1998. “With Good Cause: Bureaucratic Discretion and the Politics of Child Support Enforcement.” American Journal of Political Science 42(4):1133–56. doi: 10.2307/2991852.

- Krøtel, Sarah M. L., Rachel Ashworth, and Anders R. Villadsen. 2019. “Weakening the Glass Ceiling: Does Organizational Growth Reduce Gender Segregation in the Upper Tiers of Danish Local Government?” Public Management Review 21(8):1213–35. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1550107.

- Lee, Danbee, and Yahong Zhang. 2021. “The Value of Public Organizations’ Diversity Reputation in Women’s and Minorities’ Job Choice Decisions.” Public Management Review 23(10):1436–55. And doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1751253.

- Lee, Hongseok. 2022. “Perceived Racial Discrimination in the Workplace: Considering Minority Supervisory Representation and Inter-Minority Relations.” Public Management Review 24(4):512–35. DOI: 0.1080/14719037.2020.1846368 doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1846368.

- Lockwood, Graeme, Claire Henderson, and Graham Thornicroft. 2013. “Challenging Mental Health Discrimination in Employment.” Journal of Workplace Rights 17(2):137–52. doi: 10.2190/WR.17.2.b.

- Manzi, Francesca. 2019. “Are the Processes Underlying Discrimination the Same for Women and Men? A Critical Review of Congruity Models of Gender Discrimination.” Frontiers in Psychology 10:469. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00469.

- Marvel, John, and William D. Resh. 2019. “An Unconscious Drive to Help Others? Using the Implicit Association Test to Measure Prosocial Motivation.” International Public Management Journal 22(1):29–70. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2018.1471013.

- Mastekaasa, Arne. 2020. “Absenteeism in the Public and the Private Sector: Does the Public Sector Attract High Absence Employees?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30(1):60–76. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muz003.

- Meager, Nigel, Claire Tyres, Sarah Perryman, Jo Rick, J. Rebecca, and R. Willison. 2002. Awareness, Knowledge and Exercise of Individual Mechanisms. London: IES.

- Meier, KennethJ. 1993. “Representational Bureaucracy: A Theoretical and Empirical Exposition.” Research in Public Administration 2:1–35.

- Meier, KennethJ., and Jill Nicholson-Crotty. 2006. “Gender, Representative Bureaucracy and Law Enforcement: The Case of Sexual Assault.” Public Administration Review 66(6):850–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00653.x.

- Morton, Fraser. 2020. Employment Tribunal Award Statistics 2019–2020. Retrieved March 20, 2022 (https://www.morton-fraser.com/insights/employment-tribunal-award-statistics).

- Mosher, Frederick. 1982. Democracy and the Public Service. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Naff, Katherine C, and K. Juree. Capers. 2014. “The Complexity of Descriptive Representation and Bureaucracy: The Case of South Africa.” International Public Management Journal 17(4):515–39. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.958804.

- ONS. 2019. “Who Works in the Public Sector?” Retrieved June 29, 2020 from (https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicspending/articles/whoworksinthepublicsector/2019-06-04).

- ONS. 2020. “Disability Status and Sex by Sector of Employment, UK, 2015 to 2017” Accessed 3 January, 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/publicsectorpersonnel/adhocs/11964disabilitystatusandsexbysectorofemploymentuk2015to2017.

- ONS. 2022. “Outcomes for Disabled People in the UK: 2021” Retrieved March 28, 2022 from (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/outcomesfordisabledpeopleintheuk/2021#employment).

- Park, Jungyeon. 2021. “Going Beyond The System: The Role of Trust In Coworker Support And Organization-Based Self-Esteem in Dealing With Sexual Harassment Issues” International Public Management Journal 24(3):418–434.

- Roberts, Simon, Claire Heaver, Katherine Hill, Joanne Rennison, Bruce Stafford, Nicholas Howart, and Graham Kelly Graham. 2004. Disability in the Workplace: Employers' and Service Providers’ Responses to the Disability Discrimination Act in 2003 and Preparation for 2004 Changes. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

- Rolison, Jonathan J, Yaniv Hanoch, Stacey Wood, and Pi-Ju Liu. 2014. “Risk-Taking Differences across the Adult Life Span: A Question of Age and Domain.” The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 69(6):870–80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt081.

- Santuzzi, Alecia M, Robert T. Keating, Jesus J. Martinez, Lisa M. Finkelstein, Deborah E. Rupp, and Nicole Strah. 2019. “Identity Management Strategies for Workers with Concealable Disabilities: Antecedents and Consequences.” Journal of Social Issues 75(3):847–80. doi: 10.1111/josi.12320.

- Schieman, Scott. 2006. “Gender, Dimensions of Work, and Supportive Coworker Relations.” The Sociological Quarterly 47(2):195–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00043.x.

- Thaler, Richard, and Cass Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. London: Penguin.

- Van Ryzin, Gregg G., Norma M. Riccucci, and Huafang Li. 2017. “Representative Bureaucracy and Its Symbolic Effect on Citizens: A Conceptual Replication.” Public Management Review 19:1365–1379 doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1195009.

- Van Wanrooy, Brigid, Helen Bewley, Alex Bryson, John Forth, Stephanie Freeth, Lucy Stokes, and Stephen Wood. 2013. Employment Relations in the Shadow of Recession: Findings from the 2011 Workplace Employment Relations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.