Abstract

Interdependence is typically regarded as the cause of inter-organizational collaboration. But it is also a consequence. Collaboration itself creates new interdependence as partners become more entwined in one another’s operations and experience the vetoes, compromises, delays, and risks inherent in joint working. This paradox – mitigating one set of interdependencies by creating another – renders collaborative relations inherently unstable. Dissolution may occur if “ex-post” interdependence becomes more troublesome than the original “ex-ante” trigger for the partnership. We test this proposition through comparative analysis of 13 sustained, aborted, and dissolved inter-municipal cooperations in English local government. Ex-post interdependence was most pronounced in those partnerships that ended in dissolution, and informed the design of replacement arrangements. It was also a contributory factor in the abortive cases. But ex-post interdependence was minimized in the group of sustained collaborations by management actions that streamlined the coordination burden imposed by joint working. These findings have implications for partnership design, the collaborator’s skillset, and theories of collaborative public management.

Introduction

Organizations develop collaborative relationships in order to address external interdependencies that are deemed to be consequential for performance. Firms engage in joint ventures to develop products that may otherwise be too expensive, risky, or technically complex to attempt alone, for example (Oliver Citation1990; Doz and Hamel Citation1998; Scholten and Schilder Citation2015). And government agencies use collaborative strategies to manage the synergies, externalities, and interconnections that arise from either problem complexity, institutional fragmentation, or some combination of the two (Agranoff and McGuire Citation2003; Bingham and O'Leary Citation2008; Meek Citation2021). Indeed, so frequently do governments confront policy challenges that transcend organizations and/or sectors that Agranoff and McGuire (Citation2003:vii) regard contemporary public administration as having entered “the era of the manager’s cross-boundary interdependency challenge.” Others contend that collaboration has become an “imperative” (Kettl Citation2006) and “the predominant approach to solving complex public problems” (Silvia Citation2018:472). And many more wish it were so.

Why, then, would organizations with a history of joint working choose to terminate their collaborative arrangements and revert to independent operations? Why, in other words, should they “divorce”? Research in organization studies (for instance, Fichman and Levinthal Citation1991; Ring and van de Ven Citation1994; Jap and Anderson Citation2007; Talay and Akdeniz Citation2014) suggests that evolving internal and/or environmental conditions, poor initial forecasting of costs and benefits, and power struggles or irreconcilable cultural differences might trigger partnership breakdown. But in this article, we argue that an additional (albeit complementary) explanation can be found, in ironic symmetry, in the problem of new interdependence arising from the collaboration itself.

Organizations that engage in collaboration become more entwined in each other’s operations. Their decision-making is subject to new vetoes, compromises, delays, and risks resulting from the joint working itself. Therefore, rather than interdependence being solely an antecedent of collaboration, partnering organizations “become netted together in a web of interdependencies” (emphasis added), as Aiken and Hage (Citation1968:917) argued long ago (see also Chisholm Citation1989). This paradox of mitigating one set of problems by creating another with similar attributes brings an inherent instability to inter-organizational working. Because managers need some autonomy to adequately control service delivery (Gouldner Citation1959; Cook Citation1977), and because coordinating interdependent parties through "mutual adjustment" is both costly and fallible (Thompson Citation1967; March and Simon Citation1993), collaborations may be abandoned if the “ex-post” interdependence arising from the joint working itself comes to be regarded as more troublesome than the “ex-ante” interdependence that led to the decision to collaborate in the first place.

We test this proposition through comparative case research involving thirteen sustained, dissolved, and abortive inter-municipal cooperations (or “shared services”) undertaking tax collection and social assistance programs in England during 2004-21. Interview and archival data reveal that, though present in all cases, ex-post interdependence was most pronounced in partnerships that ultimately ended in voluntary dissolution. It was also explicitly cited in their termination decisions, and informed the design of their replacement arrangements for service delivery. Ex-post interdependence was also a contributory factor in abortive cases, where collaboration was abandoned midway through development. However, in the sample of sustained collaborations, ex-post interdependence was far less pronounced, having been minimized by proactive management actions that streamlined the coordination processes required in highly interdependent systems. This lessened both the objective administrative burden created by joint working and the salience of that burden among staff, so doubly reducing pressure for dissolution.

These findings challenge the notion that theories of resource dependence have less to say about how collaborations evolve over time than how they are formed in the first place. They also qualify the claim that managing collaborations requires a “unique” skillset compared to conventional public management; for both require the coordination of interdependencies in work processes, whether these originate internally or externally, and whether they are the stimulus for collaboration, or an artifact of it. Finally, regarding partnership design, ex-post interdependence indicates that reaching collective solutions to policy problems is not only inhibited by information asymmetry and opportunism (problems of governance, studied in institutional economics), but is also constrained by partners’ capacity to achieve reliable yet efficient coordination of work processes (problems of administrative science).

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. The next section reviews existing accounts of collaborative dissolution, and the third builds our theoretical model. The fourth and fifth introduce the empirical case and research design, and the sixth and seventh present and discuss the results. Theoretical and practical implications are then considered.

Dissolving inter-organizational relations

Inter-organizational relations are “relatively enduring transactions, flows, and linkages that occur among or between an organization and one or more organizations in its environment” (Oliver Citation1990:241). (Throughout, we employ the terms “collaboration,” “cooperation” and “partnership” interchangeably as instances of inter-organizational relations.)Footnote1 Such multi-organizational arrangements, which occur both within and between the public, private and nonprofit sectors, may be open-ended or intentionally time-limited (Woo Citation2021); but, in either case, can be subject to unplanned termination.

Firstly, changes within the organization or its environment may alter the necessity or desirability of collaboration (Seabright et al. Citation1992). Organizations may develop new capabilities internally, reducing their dependence on external partners. Or an alternative partner may be found to supply the missing capability at lower cost or higher quality. Or the organization’s strategy may evolve so that the missing capability is no longer goal-critical. Either way, “the reasons for the severing of exchange relationships are the inverse of the reasons for their formation” (Seabright, et al. Citation1992:123) – i.e., the loss or reconfiguration of the external interdependence that triggered collaboration in the first place.

Break-up may also result from failure to achieve anticipated performance gains. Partnerships are devised under conditions of bounded rationality, with forecasted costs and benefits containing inherent uncertainty (Talay and Akdeniz Citation2014). Once those predictions are tested, disillusionment may cause termination or downsizing. However, collaborative performance may be difficult to ascertain (Guarneros-Meza et al. Citation2018). Sponsors may attempt performance turnaround by increasing investment or oversight. And even when enthusiasm is waning, sunk costs, lack of alternatives, limited capacity for reform or continuing regulatory requirements may prevent or delay termination (Oliver Citation1990; Talay and Akdeniz Citation2009; Schrank and Whitford Citation2011). Furthermore, staff may form inter-personal attachments across partnering organizations, biasing them toward “maintaining an [inefficient] exchange … curtailing the exploration of available alternatives and more generally enhancing immobility” (Seabright, et al. Citation1992:127). In this manner, “network inertia” may inhibit rational adaptation to new circumstances (Tai-Young et al. Citation2006).

Alternatively, partnerships may evolve through a “life-cycle,” where risk of termination varies over time (Lowndes and Skelcher Citation1998; Jap and Anderson Citation2007). Familiarity and trust among partners may change with age, for example; as may enthusiasm of sponsor organizations, intensity of oversight, and size of resource commitment (Fichman and Levinthal Citation1991). New relationships may be especially vulnerable to termination due to difficulties of role innovation and coordination between strangers; whereas mature partnerships may be protected by escalating commitments, path dependence and inertia (Ring and van de Ven Citation1994:107). Alternatively, Fichman and Levinthal (Citation1991:442) suggest a “liability of adolescence,” in which “the hazard rate of the relationship ending increases for an initial period and then declines,” creating an early “honeymoon period” (see also Deeds and Rothaermel Citation2003). This occurs when partnerships are founded with protective but time-limited “assets,” like cash, goodwill, and psychological commitment. These initially de-sensitize partners to negative feedback about performance, meaning that the same adverse event may affect survival chances differently depending on when it occurs.

Organizational culture and inter-organizational trust can also influence partnership termination. Cultural “fit” describes the extent to which norms and values are compatible between partners (Weare et al. Citation2014; Dixon Citation2021). Do explicit and implicit objectives overlap, or is there “strategic discord”? Does communication require decoding of culturally-specific messages, causing error and delay? (Talay and Akdeniz Citation2009:238) Again, any initial assessment of compatibility will be confirmed or revised experientially. And values and beliefs may evolve over time, either converging and sustaining the relationship, or diverging and undermining it. Similarly, buildup of trust may support longevity by gradually reducing transaction costs (Zyzak Citation2017:257–258; Song et al. Citation2019). Perception of “equity” and “fair dealing” may also be important (Ring and van de Ven Citation1994:93–94), and compact violations may hamper future relations (Zyzak Citation2017). Indeed, the enhanced oversight and formalization of governance that typically result from mistrust may themselves damage partnership performance, further hastening dissolution (Ring and van de Ven Citation1994).

Overall, then, partnership dissolution may be prompted or delayed by multiple conditions. Objective performance is not necessarily determinative of continuing relations; and nor is termination automatic when founding conditions are reversed. As Zyzak (Citation2017:254) concludes, “there is no unified theoretical approach to explain breakdown.” To bring such an account within closer reach, we next set out how interdependence could underpin both partnership formation and termination.

Interdependence and partnership dynamics

Ex-ante and ex-post interdependence

Interdependence arises whenever “one actor does not entirely control all of the conditions necessary for the achievement of an action, or for obtaining the outcomes desired from the action” (Pfeffer and Salancik, Citation1978:40). Inside organizations, this occurs when “individuals, departments, or units … depend on each other for accomplishing their tasks” (Thompson Citation1967). Indeed, interdependence in complex production processes is precisely the reason for arranging work in formal organizations in the first place, since their authority structures, routines and staff socialization often prove more efficient than markets at coordinating production (Blau and Scott Citation1963:5). Coordination is thus a response to interdependence, aimed at ensuring that “each decision in a set is somehow adjusted … to other decisions in the set, rather than standing without any influence from the others” (Lindblom Citation1965:25). Scheduling of new projects can be adjusted to accommodate different workloads among the various contributing parts of the organization, for example; and project specifications can be expanded to satisfy multiple needs or avoid duplication.

As well as coordinating these internal interdependencies, organizations are also “open systems,” exposed to and affected by the external environment. This includes the behavior of related organizations (suppliers, regulators, funders), the availability of resources (finance, workforce, materials), and wider social, political or economic events (Katz and Kahn Citation1978). So powerful are these outside determinants of performance that Pfeffer and Salancik (Citation1978) speak of the “external control” of organizations. Re-gaining control can involve managers bargaining with third parties whose behavior affects the organization, “internalizing” critical dependencies by acquisition or merger, or forming new inter-organizational relations (Chisholm Citation1989; Hillman et al. Citation2009). Indeed, Alexander (Citation1995:271) describes external interdependence as the “critical stimulus” that explains partnership formation, while Gray (Citation1985:921) argues that collaboration “make[s] no sense” without “some fundamental interdependence” between partners.

Nonetheless, interdependence is not only a cause of collaboration; it is also a consequence. The very act of collaborating – of devoting scarce resources to a shared endeavor in which policy and results are jointly determined – generates new interdependence. Decisions that could previously have been taken without much regard for external opinion now must be taken consensually, even for matters relatively removed from the focal activity (due to chain reactions and “tight coupling” (Orton and Weick Citation1990)). Consultations, permissions, and adjustments need to be sought where hitherto they were not, so debate and negotiation increase while flexibility and rapidity decline (Hood Citation1976:89). And exposure to each other’s successes and failures, competencies and opportunism arises in a wider domain of activity than when the separate organizations simply co-existed in the same environment. Hence, as Aiken and Hage (Citation1968:913–914) conclude, interdependence is not only an antecedent of collaboration; it is also a outcome, such that:

“The greater the number of joint programs, the more organizational decision-making is constrained through obligations, commitments, or contracts with other organizations, and the greater the degree of organizational interdependence.”

Ex-post interdependence and collaborative dissolution

We thus arrive at the paradox underpinning our theory of partnership dissolution. Managers wishing to mitigate the “external controls” on their organizations adopt collaborative arrangements which themselves generate new “ex-post” interdependencies, ceding control to environmental forces in new and unprecedented domains. While existing literature already recognizes such autonomy loss as a key difficulty in collaborative public management (Thomson and Perry Citation2006; Carlsson et al. Citation2022) and a potential cause of termination (Seabright, et al. Citation1992), conceptualizing this more specifically as the accrual of ex-post interdependencies brings several advantages. First, whereas the concept of autonomy loss is somewhat abstract and “enigmatic” (Zeemering Citation2018:603), interdependencies are more traceable in fieldwork. Second, this approach highlights an oft-ignored symmetry in management challenges for both collaborative and conventional service delivery: the need to coordinate interdependencies that affect performance, whatever their origin. And third, and most importantly, this approach provides a significant head start in generating theoretically-informed predictions of when collaborations will terminate. In particular, because interdependencies vary along a number of dimensions, different forms of ex-post interdependence may be more-or-less tolerable or problematic for collaborators, and thus have differing effects on the risk of dissolution.

Four dimensions of interdependence seem particularly relevant to partners’ experience of autonomy loss and propensity to terminate:

Strength of interdependence is the extent to which one party’s actions affect another, determined by the opportunity cost of actors ignoring their mutual reliance and acting independently (Baldwin Citation1980). Strong interdependence, with high opportunity costs for uncoordinated action, exerts greater influence over organizational performance than weaker interdependence.

Direction refers to the distribution of costs and benefits among interdependent parties. When interdependence is “positive” (or “cooperative”), coordination makes both parties better off (i.e., is win-win). Conversely, for negative (or “competitive” or “zero-sum”) interdependence, goal attainment by one party “interferes with and makes it less likely that others will reach their goals” (Tjosvold Citation1986:524). If, for instance, finite budget is distributed among two projects, the size of one award is constrained by the size of the other (producing interdependence), and the more funding granted to the former, the less is available for the latter (negative interdependence).

Predictability describes whether the causes and consequences of interdependence are regularized or not. As March and Simon (Citation1993:180) explain, “stable and fixed” interdependence is relatively unproblematic since mutual adjustments can be encoded into organizational routines. Conversely, “difficulties arise only if program execution rests on contingencies that cannot be predicted perfectly in advance,” since the errors and exceptions that occur require managerial intervention on a case-by-case basis, which is costly and fallible.

Lastly, salience is the extent to which parties recognize their interdependence. As Deutsch (Citation1949:138) explains, there may be a “lack of perfect correspondence between ‘objective’ and ‘perceived’ interdependence” (see also Tjosvold Citation1986). Significant connectivity may be overlooked it if lacks salience among busy decision-makers (Hedlund et al. Citation2023); and perceived interdependence may exaggerate objective conditions, or even be a fabrication (Elston et al. Citation2023b).

With both ex-ante and ex-post interdependence potentially varying along each of these four dimensions, risk of termination will vary under different scenarios.

Firstly, and most straightforwardly, collaboration should be more tolerable when ex-ante interdependence is stronger than ex-post, so that the opportunity cost of uncontrolled environmental disturbance is greater than that of investing resources in coordinating ex-post interdependencies. Conversely, where ex-post interdependencies is stronger than ex-ante, termination may be considered; for the cost of collaboration outweighs the benefits.

Secondly, regarding direction of interdependence, organizations often appear more attentive to solving problems than proactively exploiting opportunities. Prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1979), bureaucratic risk aversion (Chen and Bozeman Citation2012), and asymmetric responses to positive and negative feedback (Greve Citation2003) all support the conjecture that managers will prioritize avoiding negative interdependence over exploiting positive interdependence. (Optimism bias provides a potential counter-argument.) Thus, collaboration designed to avoid damaging externalities may be tolerated even with strong ex-post interdependence. But collaboration to exploit synergies between partners might be abandoned if it brings negative ex-post interdependence with a competitive, zero-sum pay-off.

Thirdly, regarding predictability, when coordination of ex-post interdependence can be sufficiently regularized to be incorporated into organizational routines, lowering the burden on administrators, the likelihood of termination should reduce. Such routinization may be gradual and a reaction to initial inefficiencies imposed by high interdependence (March and Simon Citation1993). New inter-organizational entanglements need to be understood, and solutions need to be trialed, refined, and encoded in routines. Were such adjustments to be difficult or delayed (for instance, because of highly variable and contingent interdependence), termination may be triggered.

Fourth and finally, Deutsch (Citation1949), Tjosvold (Citation1986), Hedlund, et al. (Citation2023) and others argue that decision-makers respond to perceived rather than objective interdependence. Organizational culture or the professional background of decision-makers might affect which interdependencies are either prioritized or over-looked. A significant negative event – for instance, a well-publicized mistake that attracts media attention or political scrutiny – could raise the profile of a previously ignored interdependence. Or, given the bounded rationality under which partnerships are formed (Talay and Akdeniz Citation2014), and the tendency to ignore bad news during “honeymoon periods” (Fichman and Levinthal Citation1991; Deeds and Rothaermel Citation2003), recognition of ex-post interdependence may only develop gradually.

Three summary propositions

These arguments about how interdependence stimulates both the formation and termination of inter-organizational relations can be summarized with the following set of propositions, which the remainder of this article tests empirically:

Organizations collaborate in order to address external interdependencies that are deemed consequential for performance; but, in so doing, generate new, “ex-post” interdependencies that result from the collaboration itself.

Because organizations value autonomy, and because coordination of interdependencies is costly and fallible, ex-post interdependence renders partnerships inherently unstable and at risk of dissolution.

Collaborations are more likely to dissolve when:

a. Ex-post interdependence is strong relative to ex-ante interdependence;

b. Ex-post interdependence involves a negative, competitive pay-off for partners;

c. Ex-post interdependence is unpredictable, and/or the administrative capacity for coordination is slow to develop;

d. The salience of ex-post interdependence increases, either because of initial bounded rationality or spotlighting caused by adverse events.

Empirical case

Inter-municipal cooperation

We test these propositions on the case of inter-municipal cooperation in England. Inter-municipal cooperation involves two or more neighboring or non-neighboring local governments providing one or more public service jointly across their jurisdictions (Tavares and Feiock Citation2018; Teles and Swianiewicz Citation2018; Holum Citation2020). It is a subtype of collaborative public management, widely used to obtain scale economies in local services. (For reviews on the financial effects of inter-municipal cooperation, see Bel and Warner (Citation2015); Silvestre et al. (Citation2018); Bel and Sebő (Citation2021).) Management of regional externalities, and improved service quality and resilience, are also common objectives (see Holum and Jakobsen Citation2016; Aldag and Warner Citation2018; Warner et al. Citation2021; Arntsen et al. Citation2021; Elston and Bel Citation2023; Elston et al. Citation2023b).

Termination of inter-municipal arrangements has received little research attention. Zyzak’s (Citation2017) comparative case research in Norway found that limited administrative capacity, high political turnover, informal governance and a desire for more geographically-proximate partners led to termination. Similarly, Zeemering’s (Citation2018) study of disbanded police cooperations in California concluded that poor performance, differing local priorities, and – again – insufficient administrative capacity caused dissolution. Aldag and Warner (Citation2018) used econometric techniques to show that a focus on cost reduction rather than service quality, high staff turnover, and simultaneous outsourcing were all associated with shorter agreements between municipalities in New York state. And Chen and Sullivan (Citation2023) found that prior performance, balanced rather than imbalanced resources, and participant homophily reduced the likelihood of participants leaving interlocal collaborations in Illinois.

Local tax and social assistance services in England

English local governments consists of a two-tier system of district and county councils in predominantly rural areas, and single-tier unitary authorities, metropolitan boroughs and London boroughs elsewhere.Footnote2 By 2017, most were using one or more inter-municipal cooperation (generally termed “shared services”) to deliver a wide range of local services, driven by severe financial pressure since 2010 and the pausing of nationally-imposed council mergers between 2009 and 2019 (Dixon and Elston Citation2020; Elston and Dixon Citation2020). Among the most commonly shared functions, particularly among district councils,Footnote3 are “revenues and benefits” services (Dixon and Elston Citation2019). These collect domestic and business property taxes (amounting to some £60bn in 2019–20) and distribute a nationally-designed and -funded means-tested rent subsidy to low-income households called Housing Benefit (worth £18bn). Revenues and benefits teams thus maintain contact with every household and business in their jurisdiction, with most adults on low incomes, and with other council teams like Housing Departments, which are responsible for allocating public housing stock, liaising with third-sector housing providers, and meeting statutory duties to reduce homelessness (see Walker and Williams Citation1995). Indeed, the (then) local government inspectorate argued that “the [benefits] service needs to establish effective links with many other areas of council work” in order to deliver high-quality services to local residents (Audit Commission Citation2001). This interdependence between different services within a single council is important to our analysis, below.

Across councils, tax collection rates are typically high (Dixon and Elston Citation2019), and benefit processing speeds improved markedly during the 2000s (Murphy et al. Citation2011), but payment accuracy continues to be criticized. In 2019–20, overpayments were estimated at 6 per cent of the total Housing Benefit budget, and underpayments at 1.7 per cent (Department for Work and Pensions Citation2020:192). Central government, which pays for Housing Benefit, penalizes councils with high error rates by withholding funding. Since 2016, it has also sought to combine Housing Benefit for working-age claimants with five other welfare entitlements that are administered centrally, reducing councils’ caseload significantly. Beset with difficulties, these reforms (known as “Universal Credit”) have been repeatedly delayed, creating uncertainty for councils in planning for declining caseloads.

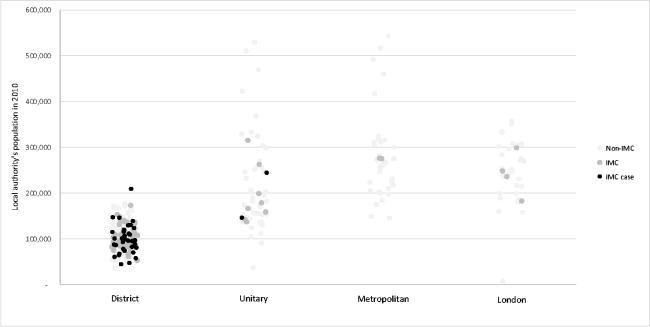

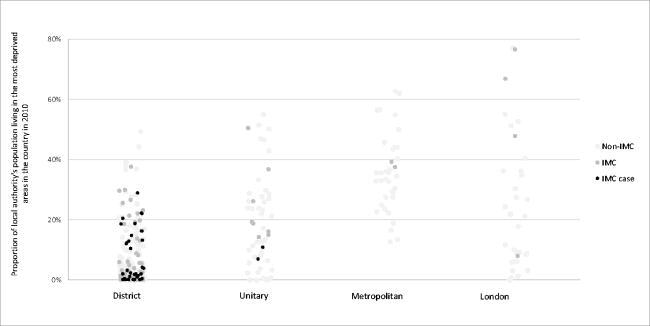

Research design and methods

Given the limited number of cases of dissolution among England’s shared “revenues and benefits” services to-date, and the multiple factors likely to influence termination decisions, we adopt a qualitative research design focused on comparing similar cases of collaboration ending in different outcomes. Our sample consists of: (i) all five known cases of partnership termination over the last two decades; (ii) all five known cases of “abortive reforms,” in which an intended collaboration was abandoned during its development; and (iii) a sample of three “negative cases” of sustained collaboration, selected as the three longest surviving partnerships as of August 2021. Appendix 1 compares our 13 cases against both English councils in general and the subgroup (about 28 per cent) that deliver revenues and benefits inter-municipally. Collaboration is far more prevalent among lower-tier districts; but is otherwise spread fairly evenly among small and large jurisdictions (by population size) and those with higher or lower incidence of social deprivation. Our sample reflects this profile well. (To maintain informant anonymity, council identities are not disclosed).

To identify sequences of issues, events and decisions preceding partnership formation and termination, documentation was sought from council websites, council information requests, and local media outlets. Nearly 600 items were collected, including committee agendas, discussion papers and meeting minutes; performance reports; corporate plans; commissioned external reviews; and newspaper articles. Semi-structured interviews with bureaucrats were then used to generate narrative accounts of the instigation, development and/or termination of the 13 partnerships. Informants were selected for having direct involvement in establishing, running, or closing the partnership. We first approached more senior officers whose relevance could be inferred from job titles (e.g., “Head of Revenues and Benefits Shared Service”), wherever possible seeking representatives from multiple councils within the same partnership. We then proceeded by recommendation to more junior colleagues or others that had changed role since the events in question occurred. A total of 21 interviews, involving 23 participants (three in a focus group) were achieved during August and September 2021. Fifteen interviewees held management positions. Interviews used video conferencing software, lasted up to 75 min, and were transcribed verbatim. The topic guide combined questions on (i) the origin, costs and benefits, governance, side-effects, and ultimate outcome of partnerships; (ii) whether and how interdependence arose within partnerships; and (iii) particular events, issues or meetings identified from the documentary research as potentially relevant.

Documents and transcripts were coded deductively. Each passage indicating ex-ante or ex-post interdependence entered the database, as did explanations of strategies used to establish or improve the partnership (e.g., policy standardization, changes to governance arrangements). Additional codes recorded significant features or events relevant to each case but not captured by the main framework. Coded data was then reviewed, first to remove any mis-coded items, then by grouping data according to case outcomes (sustained, aborted, dissolved), and then finally by the four sub-propositions 3a–d, listed previously. We sought to confirm or refute emergent findings by triangulating between sources.

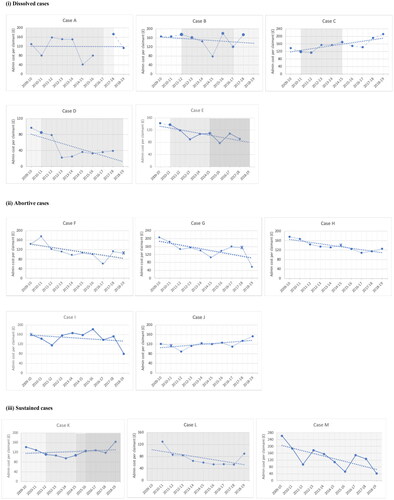

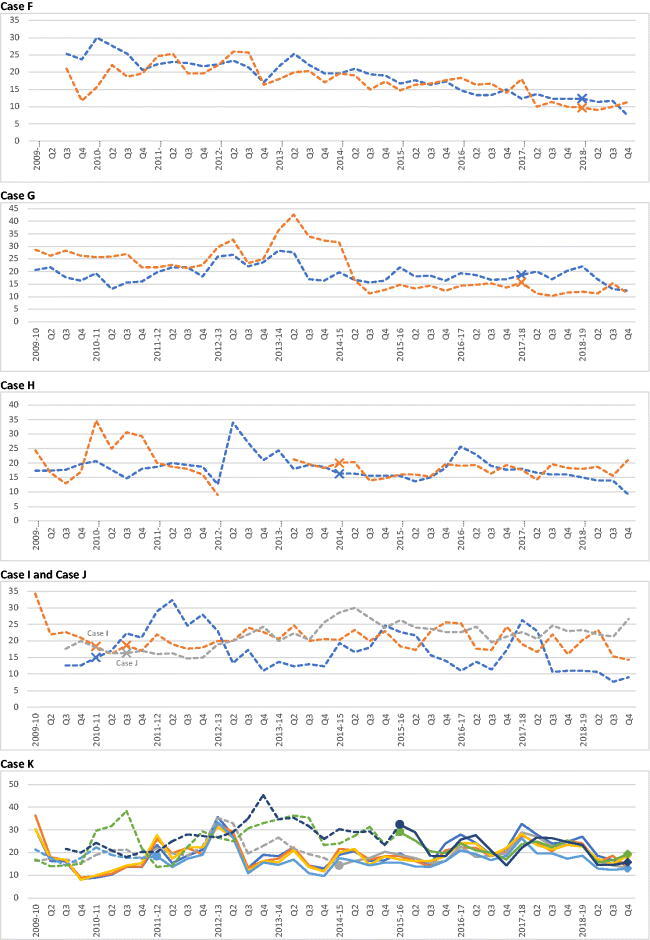

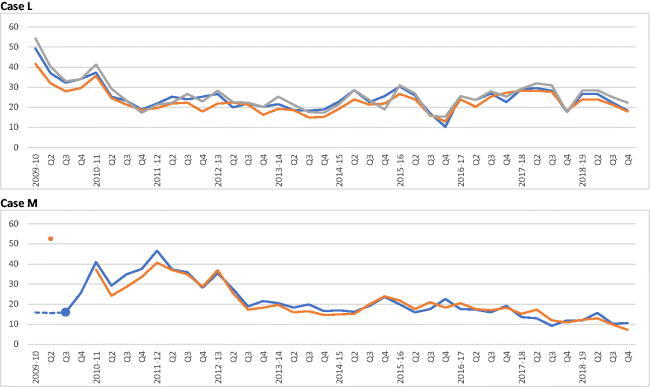

Finally, to corroborate the narrative accounts of partnership performance, we also analyzed partnership-level data on administrative costs per Housing Benefit claimant (see ), and council-level data on case processing speeds (see Appendix 2), both for the decade 2009–19 (during which time the population of local authorities and the specification of these performance metrics were stable). Although Housing Benefit is just one portion of the work of each partnership, it employs most staff (due to the labor-intensive nature of means-testing) and attracted most discussion in council documents and interviews.

Results

Collaboration life cycles, governance and performance

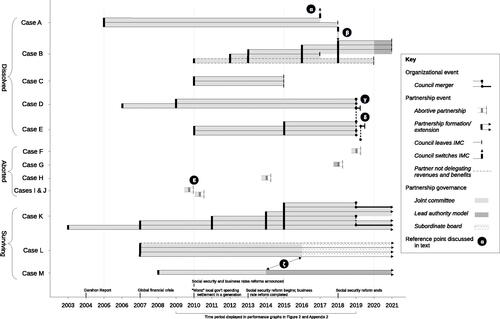

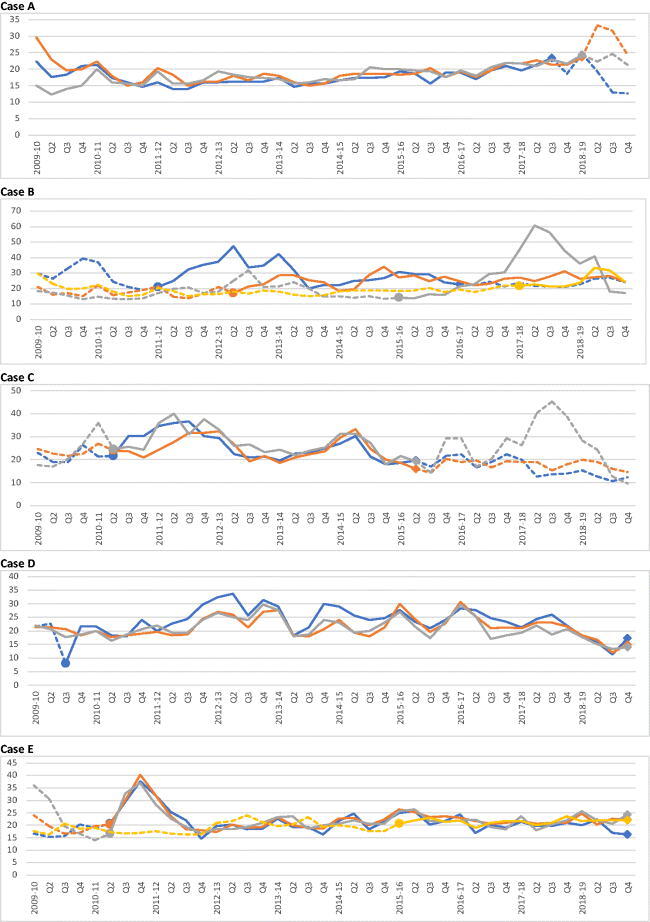

depicts the life cycles of the 13 cases. Five terminated after between 5 and 13 years of operation, either through locally-instigated withdrawal (Cases A-C) or after nationally-legislated council mergers (D and E). Five more were canceled before the joint service delivery went live (F-J). And three surviving collaborations (K-M) lasted for between 12 and 18 years (by 2021), in one case expanding threefold since its inception.

Annotations along the x-axis depict relevant national policy events. Incidence of partnership formation/expansion was highest after the financial crisis of 2007–08, the change of national government in 2010, and its program of fiscal retrenchment. Other relevant events include the aforementioned amalgamation of working-age Housing Benefit into the new centrally-administered “Universal Credit” scheme, and the replacement of national Council Tax Benefit with local support based on council-devised eligibility.

Partnership governance is denoted with four degrees of shading. Most cases began as joint committees, consisting of councilor politicians from each partner with equal voting rights. Only the aborted Case G planned a less participative, more contractual, “lead authority” model from the start, in which one council was to provide services as a nominated agent of the others. But four cases adapted their governance over time, either switching to this simpler lead authority model (Cases B and M), jointly outsourcing to a private provider (Case L) or adding late-comer partners on more contractual terms (Case K).

Regarding performance, the best-fit lines in indicate that, for the whole decade 2009–19, estimated administrative costs per Housing Benefit claimant declined in 9 of the 13 cases. These savings occurred in three of the five dissolved cases, four of the five abortive cases, and two of the three sustained partnerships. Conversely, costs flatlined or markedly increased in two of the dissolved cases, and slightly increased in the remaining one abortive and one sustained case. As for service quality, Appendix 2 depicts monthly average case processing speeds for each case council and partnership. Collaboration corresponds with faster benefit processing in Cases K and M. But the same occurs in abortive Cases F and G. And worsening performance follows the onset of collaboration in Case A and, initially, in Cases C, E, L and M. Overall, therefore, collaboration is not associated with systematic performance gains in either financial or non-financial terms in our case studies (findings confirmed by the impact evaluations in Elston et al. Citation2023a and Elston et al. Citation2023b).

Ex-ante interdependence

Turning to the qualitative data, we begin by comparing the three groups of cases – sustained, aborted, and dissolved – in terms of motivations for the collaboration. Since termination risk may be higher in those cases that experienced weaker ex-ante interdependence at the outset (and thus stood to profit less from collaboration), we must test this first before considering the impact of ex-post interdependence.

Across all cases, the rationale for merging revenues and benefits departments was expressed in terms of achieving objectives that were (believed to be) unattainable by councils acting individually. Principally, these related to cost savings owing to the increased scale of operation possible through collaboration. As one initial “options paper” explained, “services in district councils could be run more efficiently and effectively if they could secure an economy of scale which individual districts simply cannot do alone” (Doc-1). A business case for another partnership similarly referred to the “economies of scale inherent within any shared service” (Doc-2). And an official told us that, prior to their partnership, “each individual organization was overspending in Revs and Bens” (Int-13).

The mechanisms conjectured for these cost savings were multiple. Bulk-buying discounts were often cited: “contracting collectively [is] considerably cheaper than going out to software providers individually” (Int-12); “you’re immediately dealing with much bigger volumes, and therefore can attract better deals” (Int-3). Pooled investments in labor-saving technology were also mentioned; particularly regarding “self-service” websites in which service users undertake data entry for themselves (Doc-3). Production and maintenance of legislation-compliant “single processes” (Int-7), designed once but “copy-pasted” (Int-15) across multiple jurisdictions, was also referenced, as was job losses (Int-16).

Some councils anticipated improvements in service quality and resilience too. “A lot of small authorities who try to work in isolation can end up without specialist [staff],” said one official (Int-4). And a business case argued: “It is difficult, and expensive, to provide the specialist, technical parts of revenues and benefits in a small team” (Doc-4). In partnership, however, “the volume of work is huge, absolutely huge” (Int-17), and you gain access to “specialists that … you couldn’t afford to pay for if you’re on your own” (Int-8). As for service continuity, interviewees from one case explained how they formed a “resilience team” to be deployed flexibly across partner jurisdictions according to weekly need (Ints-18, −19, −21). And a case worker from another recalled: “Part of the reason for joining the partnership was that we could actually share the expertise that existed in the other two councils [to improve business continuity]” (Int-3). Nonetheless, these gains to quality and resilience were still regarded in primarily financial terms – reflecting the wider context of retrenchment since 2010 and “a real desperation that there was no money” (Int-7). One council expected more accurate benefit processing to reduce financial penalties levied by central government for “overpayment errors” (Doc-5). And another argued: “if you don’t have resilience, your business continuity to resolve issues becomes expensive [because you pay a premium for urgent, unscheduled help from contractors]” (Int-3).

Comparing these rationales for collaboration across sustained and dissolved cases, there is no discernable difference in either the tenor or magnitude of the expected benefits. The ex-ante interdependencies were alike, irrespective of the ultimate outcome of partnering. With the five abortive arrangements (Cases F-J), however, more detailed cost appraisal and changes to national welfare policy between project announcement and implementation led prospective partners to downgrade the predicted benefits. One reported that “inclusion of Universal Credit into the Partnership Business Case has eroded the anticipated salary savings,” since council caseloads would now reduce anyway (Doc-6). Staff in another of the abortive cases gradually realized that the likely economies were only slight and, thus, could be obtained autonomously:

From [the partner’s] point of view, there was potentially a significant amount of savings to be made – we were talking £100,000s. But when it came to [us], once we got through the options appraisal, we were looking at around £20,000-30,000. And the deputy chief executive … didn’t feel this was significant enough, and they came up with another option of how to [make that saving without entering the partnership]. (Int-6; also Int-9)

Ex-post interdependence

Turning to “ex-post” interdependencies, the intensity and tone with which new, collaboration-induced contingencies and constraints on decisions and performance were reported differed markedly across the sustained, aborted, and dissolved cases.

Sustained collaborations. Among sustained cases, all interviewees reported ex-post interdependencies, but none regarded these as appreciable compared to the benefits of collaboration. Ensuring continued liaison with “deeply interrelated” (Doc-7) services still provided in-house by each council was one concern. In Case K, this mainly involved providing access to data, like the registry of taxable businesses (for councils’ economic planning) or lists of benefit claimants (for Housing Departments). As one official explained, “the data we hold is very rich for them [the partners] to analyze and work with” (Int-4). In Case L, dependencies with retained Information Technology (IT) functions were initially problematic. “Revenues and Benefits is a significant user of IT services” (Int-16), and is “particularly IT dependent” (Doc-7) (see also Maybury, Citation2019). Consequently, the partners quickly transferred this function to the shared service too, re-uniting the interdependent teams within the same common provider. Also in Case L, problems arose after policy changes “were not communicated to each authority’s Housing Department, leading them to give out incorrect information [to tenants]” (Doc-7). A review recommended that “joined-up thinking and working with each authority’s Housing department … be explored by the [shared service],” and the frequency of liaison meetings duly increased.

As well as coordinating shared and retained functions, councils in the sustained group noticed increased financial interdependence arising from collaboration. High error rates when processing Housing Benefit incur penalties from central government, which both funds the benefit and contributes toward administration costs. Accordingly, “A mistake … by the shared service [is] shared amongst the authorities … regardless of where the mistake arises [i.e., in which council area]” (Doc-8). Indeed, one year, councils in Case L received no reimbursement for administrative costs because of high error rates. In addition, several councils added lower tax receipts to their risk registers after partnership commencement, partly because the vigor with which debtors would be pursued would now depend upon the collective will of the joint committee. Indeed, councils in Case K vigorously debated whether collection targets should be relaxed during the 2008–09 recession, given the more challenging context for obtaining revenue. Upon being put to a vote (itself a rarity), councilors resolved to retain the original targets by four votes to two (Doc-9).

Overall, though, ex-post interdependencies in the three sustained cases were mostly regarded as insignificant, either from the outset (Cases K and M) or after initial problems were resolved (Case L). “There isn’t much of a link [with other council activities],” argued one official, meaning that the partners could “take [Revenues and Benefits], lift it and deliver it [separately],” with any remaining interdependencies coordinated “task-by-task” in occasional “projects” (Int-4). Another interviewee from a different sustained partnership concurred, arguing that risks to council autonomy had not materialized in practice:

When you’re managing a service directly, you’re quite flexible and agile … When you’re in a partnership, obviously, it’s more consensual, and you have to do things by agreement with other partners. But, as it happens, I don’t remember a single incident where that was a difficulty …. What was a pressure point for one council would be a pressure point for others, so there was never really any conflict there. (Int-16)

Beginning again with shared and retained functions, officials in Cases A, B and C complained that Revenues and Benefits “[became] very siloed, and [were] not working in collaboration with other council departments” (Int-1); that what retained staff needed was “colleagues, not a fee structure” (i.e., not a tariff of charges preventing rapid and informal joint working with the shared service) (Int-7); and that “there was no way [to] appease and satisfy the respective control requirements of each council” (Int-12). In Case A particularly, liaison with each separate Housing Department faltered, leading to rebukes such as: “If a council [housing] tenant is also a benefit claimant, they are mutual customers!” (Int-1), and “[a] joint working approach [is] needed to prevent homelessness” (Doc-4). Efforts were made to enhance coordination. “[We tried to] create relationships with other managers from certain other services who, obviously, are going to be very much involved [in housing provision],” explained one official. “But that needed doing over three councils, so … [you] start spreading yourself a little bit thin” (Int-13). Another (from Case B) suggested that partnership expansion was most difficult: “when [a further council] joined the partnership, [my boss was] spread quite thin trying to keep three major partners happy” (Int-14).

In Case A, this increased coordination ultimately failed to assuage concerns that, “if you’ve got a service that is only concentrating on its core activities, you almost always lose that broader collaborative working across the wider organization” (Int-1). Consequently, when first one and then another council exited the partnership (forcing the one remaining partner to also abandon the project; see Reference Points α and β in ), both cited poor integration of housing services in their rationale, and both sought to rectify this in their replacement arrangements for service delivery. With the first defection, this meant finding a new partner with whom to share both benefits and housing services (Doc-10), thereby internalizing the problematic interdependence in a single shared organization. As one interviewee confirmed: “[In this new partnership], we’ve spent an awful lot of time improving liaison” (Int-1). With the second (and terminal) defection, the departing council’s Head of Housing helped select the replacement partnership, advocating one that “provided substantial reassurance and commitment toward the joint working approach needed,” including “[a promise] to work closely … to create fast-track solutions to Housing Services priorities [like] homeless prevention, temporary accommodation, [etc.]” (Doc-4).

Besides shared-retained interdependencies, the problem of no-fault financial penalties also recurred more perniciously in the dissolved cases. Case A saw three consecutive years of financial penalties from central government. “The fallout amongst elected members particularly was quite gruesome,” recalled an official, and “the leader of [one partner] decided to go to the local press and completely slammed the [shared service] staff” (Int-2). Another said: “Repeatedly, errors were discovered by the auditors that had a negative financial impact on [our council],” which meant “I will lose significant amounts of money” (Int-1). This othering of the source of the errors (“slammed the shared service”) yet personalization of their financial impact (“I will lose") highlights the growing recognition of the new and unanticipated external dependency in securing financial reimbursement. Indeed, the first council to leave Case A argued that this would “mitigate future financial penalties” (Doc-10), while the second chose its new partner (Case B) in part because of its track record whereby “None of the councils [already] in [Case B] has lost Housing Benefit subsidy” (Doc-4).

A further set of ex-post interdependencies, largely unmentioned in the sustained collaborations, related to policy standardization, which is essential for realizing economies of scale. Many informants noted that, “in theory” (Int-15), this should be straightforward. “Revenues and benefits are pretty mandated, very regulated, statutory-based services” (Int-15) and are “laid down by statute in great detail … the same between all councils” (Int-10). Nonetheless, “harmonizing working practices was probably the biggest challenge” (Int-1), given different “interpretations” of the complex and dynamic regulations (Int-17), inertia among staff transferring from different councils (Int-3), and, particularly in Case B, convoluted governance for resolving disputes. As one interviewee explained, while this shared service “had its own board … it still had to get authority from its parent [councils]” (Int-7). Consequently, “the biggest problem … was getting agreement … and getting ‘the approvals’” (Int-8). “[You] need[ed] to have buy-in all the way down the chain” (Int-21).

Attempting policy standardization amid multiple veto players had several negative effects. First was to delay decisions. As one official recalled: “[We found] that [we had only] 2.5 weeks to write the business case, because you needed four months to get through all of this ‘sign-off.’ … If anyone wanted a change, they [had] to go back down the loop and through [all the approvals] again. You were circling a lot” (Int-7). Second was to deplete morale. “I found it incredibly draining to waste so much time and energy aligning people on stuff that was fairly obvious and logical,” complained one interviewee (Int-15). “[It] felt like quite a slog,” said another (Int-7). And “the biggest challenge” was “trying to get everyone [in my team] to understand what other people [from different councils] want,” said a third, whose role was to supervise a team of Housing Benefit case workers (Int-18).

A third implication was to forestall workforce integration. “[Staff were] still treated as, effectively, local teams,” only processing cases from their original jurisdiction (Int-15). “It was: same people, same jobs, same processes … different desk” (Int-7). And a fourth effect was to abandon plans to “double in size” by adding additional partners (Doc-11). Rather, officials started to fear “tak[ing] on yet another customer with its own personality, its own politics, it’s different policies” (Int-7). Eventually, and fifthly, pressure for dissolution grew. And while policy divergence contributed to the aforementioned Case A defections (“If you don’t have that agreement … it’s going to be far harder to make a partnership work”; Int-2), it was central to Case B’s termination. “[This partnership is] difficult to manage, [gives] limited direct control for [us], … [and requires] multiple engagement/consultations for any service changes,” wrote one options paper (Doc-12). Conversely, re-taking “direct control of the service … allow[s] for greater influence” and to “‘clean up’ the currently over-complicated … arrangements,” with “simplified decision-making process [and] less complex governance” (Doc-12).

Turning to Case C, established in 2010 and dissolved five years later: again, exacerbated interdependence across shared and retained functions, problems of standardization, and complex governance fueled termination. Initially, Revenues and Benefits and ICT were co-located in the shared service (the approach that had helped to sustain Case L, above); but in 2014 the decision was taken to “revert [ICT] back to local provision,” enabling more tailored support for each partner council but impeding coordination with the “completely intertwined” revenues and benefits function (Int-12). Additionally, Housing Benefit was calculated in the partnership but “paid out of the respective financial system of each council” (Int-12), creating significant hand-over problems. “We couldn’t physically pay it,” explained an official, meaning that “if [the three Finance Departments] had queries, we had delays in our processing and backlogs of work” (Int-12). Nonetheless, as with Case B, the most significant trigger for termination was standardization and governance. Actioning recommendations from an external inspection was delayed by “extended negotiations” (Doc-13); and “progress [with ICT modernization] was slow and dependent on all parties agreeing solutions and prioritizing this work” (Doc-14). These difficulties were compounded by national policy developments, including the differently-timed rollout of Universal Credit across jurisdictions, which “meant [that] we as an operating unit had to act differently in those areas” (Int-12). The advent of new, locally-devised arrangements for council tax support benefits also introduced new opportunities for policy variance among partners (Doc-15). The overall effect was: “a heck of a lot [of meetings],” including “updates, the provision of information, explanation … briefings and all that stuff, … coming at you three ways instead of one” – all intended to “keep a lot of players … up to speed” (Int-12). Eventually, this high coordinative burden yet frequent failure to reach agreement led the partners to terminate their collaboration agreement and “localize” services once more, albeit retaining some shared contracts with suppliers (Doc-14). As one official described, “Now, if we want to do something in [our council], I can – I don’t have to rely on the other parties to agree or not, or vice versa” (Int-12).

The remaining two of the dissolved partnerships (Cases D and E) reported far less disturbance from ex-post interdependence. Work standardization was mentioned, but problems were rare (“we didn’t always have agreement”; Int-3) and short-lived (“[just] the initial problems arising from joint working”; Doc-17). Conflicting work schedules – or “queuing” – was also noted: “There were certainly periods when we weren’t able to do something for one party because we’re doing something for the other. … But that was very, very rare.” (Int-3). But in terms of strategic direction, officials “tend[ed] to get similar buy-in from all councils” and “could consistently move in the same direction across the whole of the service” (Int-3). While this lower strength and salience of ex-post interdependence differs from the other three dissolved partnerships, Cases D and E were wound-up not by local choice, but following the abolition and merger of their constituent councils by central government (see Reference Points γ and δ in ). Indeed, for Case D, the decade of effective inter-council collaboration simply proved that full merger was the logical next step (Int-3; Docs-18 and −19). Conversely, in Case E, the “remarkably successful” partnership demonstrated how improved services could be obtained without the loss to local identity and representation that council amalgamation brings (Doc-20).

Abortive. As for the five abortive cases, although these were abandoned mid-development, even just preparing to share services generated new interdependencies among prospective partners – and concern about what further constraints would follow.

Project announcement immediately affected investment decisions. “It would be paramount for each of the three Councils to be on the same ICT system, and … now could be an advantageous time for the councils to consider purchasing equipment,” wrote one proposal (Doc-21). “If [we] decide not to pursue a shared service, the decision regarding the digital solution will rest solely with [us],” noted another (Doc-22). “However, given that a shared service is to be implemented, it will be necessary to work with our partner to ensure that IT and digital provision is harmonized” (Doc-22). Failure to heed this advice meant that Case H “foundered at implementation due to incompatible IT” (Doc-23). Similarly, a proposal for technology alignment proved fatal in Case F: “The [first council] were trying to … implement a new bit of software, and [the second council] refused to follow suit … which [meant] the two departments would never be able to work [in an] integrated [way]. I think that became the turning point” (Int-6).

Additionally, fears about the burden of coordinating shared and retained functions reappeared in several aborted partnerships. “It will be necessary to agree appropriate mechanisms … to ensure that the Revenues and Benefits service … is not fractured from the delivery of other services,” warned one proposal (Doc-2). This project was soon abandoned by one partner, leaving the other to seek alternative arrangements which, again, were later aborted (see Reference Point ε in ). Similarly, a paper for abortive Case G emphasized the need to preserve existing joint projects, including work to reduce council house rent arrears through joint “Housing and Revenues … training and best practice accreditation … by the Chartered Institute of Housing” (Doc-24).

Discussion

Having completed the comparative case analysis, we return now to the conjectures from organization theory developed earlier and summarized at the end of the theory section.

The first proposition was that interdependence is both trigger for, and consequence of, collaboration. This was clearly borne out by the data. Among all cases, partnering was motivated by a perceived inability to attain efficient, specialized, and resilient service delivery by autonomous means. The firm belief was that “bigger is better,” and that partnering with one or more other authorities was the way to grow service volumes. And yet collaboration also imposed new constraints on councils, in two main categories. First were those interdependencies that pre-dated each partnership but were exacerbated by it. Coordination between separate Benefits and Housing Departments, for example, has long been regarded as essential to ensuring a “unified” local housing service (Walker and Williams Citation1995; Audit Commission Citation2001), but became more difficult once these functions were split across organizational boundaries and made responsible to multiple overseers simultaneously. Second were entirely novel interdependencies for which no pre-partnership analogue exists; for instance, processing errors in neighboring jurisdictions leading to budget shortfall across the partnership; and the determination of tax collection targets, debt-write-off polices or software choices by inter-council consensus.

The second proposition was that ex-post interdependence makes collaboration inherently unstable, because interdependence requires coordination, coordination is costly and prone to error, and these costs and errors could be avoided but for the decision to collaborate. Again, the data affirmed this. Many spoke of the reduced coordination burden after termination. “Basically, I had to do a lot of things three times” recalled an official. “[Now,] I still have meetings, but not to the same extent, and not three times!” said another (Int-2).Footnote4 The tales of hard-won policy standardization illustrate the underlying dilemma particularly well. To reap most reward from shared services, councils must totally align their tax and benefit policies, so that one set of services is “copy-pasted” across jurisdictions without variation. Only then can scale economies be fully realized; and yet such intensive standardization greatly constrains individual autonomy. Thus, the greater the ambition for achieving the benefits of collaboration, the greater the requirement for ceding control through new external interdependencies.

The third proposition was that the dissolution of collaborative relations is more likely when ex-post interdependence is (a) stronger than ex-ante interdependence, (b) involves a negative, competitive pay-off for partners, (c) is variable and not easily coordinated by routine, and (d) increases in salience over time. Strong support was found for the first, third and fourth of these conjectures; more data is required on the second.

Regarding (a) the balance of the ex-ante and ex-post interdependence, reductions in the forecasted benefits of collaboration, and increases in the costs, contributed explicitly to several cases of abortive reform. By contrast, among both the sustained and dissolved cases, virtually no-one disputed that scale economies had been realized and costs reduced as a result (although the expenditure data in , above, question this, as does recent econometric analysis (Elston et al. Citation2023b)). “Pretty much everything that was in that [original] plan was delivered and saved,” said one manager of a dissolved partnership (Int-14). Yet the price paid for these perceived efficiencies differed significantly across cases. Sustained collaborations and those ending in involuntary termination (due to council mergers) reported no appreciable problems stemming from new entanglement between councils. But those ending in voluntary dissolution described significant damage being incurred from having to accommodate outside interests when deciding “stuff that was fairly obvious and logical.” Accordingly, pernicious ex-post interdependence informed both the decision to terminate (“Now … I don’t have to rely on the other parties to agree or not, or vice versa”), and the design of replacement arrangements, including the criteria for selecting alternative partnerships and the assurances that had to be sought before committing.

Turning to (b), our findings are inconclusive about whether negative ex-post interdependence increases the propensity for dissolution. Ex-ante interdependence was deemed positive among all cases, with “win-win” pay-offs anticipated as a result of reduced average unit costs and enhanced resilience. But the ex-post interdependencies reported were mostly competitive (or zero-sum) in direction. For instance: member councils having to “queue” for sequential attention from the shared service (Int-4), vying for support from only the most experienced staff (Int-7), and seeking to agree standardizations requiring least adaptation of one’s own existing policies. In each instance, a good outcome for one partner (immediate attention, most-expert help, least adaptation) was by definition bad for others (delayed attention, less-expert help, greatest adaptation).Footnote5 Hence, we lack variance on this dimension to determine whether negative direction enhances termination risk separate to strength of ex-post interdependence.

As for (c) predictability of ex-post interdependence and development of coordination capacity: notable among the sustained partnerships was each council’s willingness to continue to adapt structures and processes, including ceding further control to the partnership where necessarily to streamline the emerging coordination burden. One strategy was “internalization” (see Alexander Citation1995:61), where interdependencies that would have spanned the new organizational boundaries were instead brought within a single authority structure. IT, for example, was co-located with revenues and benefits from the outset in Case K, and in response to initial coordination problems in Case L; and any remaining inter-organizational interdependencies were then coordinated “task-by-task” as discrete “projects.” Conversely, in dissolved Case C, IT was returned to each partner, and other interconnections that could have been streamlined (like payment handovers with each council’s finance team) were left unreformed. Indeed, in general routinization was rare in the dissolved partnerships; and, when it did occur, was perceived as bureaucratic and a retrograde step (“They would say, ‘Well, there is this form you could fill in…’” (Int-7)). Instead, officials relied on the labor-intensive strategy of developing inter-personal relationships across different organizations to achieve mutual adjustment, which meant “spreading yourself a little bit thin” and ultimately proved “frustrating” (Int-3), “incredibly draining,” and dependent upon “heck of a lot” of meetings.

Another strategy for reducing the coordination burden was to simplify the formal governance of the partnerships. This occurred in all three sustained collaborations: by reducing the frequency, membership or quoracy of committees (Cases K and L), or by abandoning joint committees altogether for less participative, more contractual terms (Cases L and M; see Reference Point ζ in ). Conversely, among dissolved partnerships, governance either remained unreformed for too long, or actually increased in stringency as partners sought more formal protections against autonomy loss. In Case A, an initial arrangement whereby “one of the partners [led] and the other two were following” was curtailed after a change of leadership in one partner (Int-13), whereupon “the scale of that governance increased” (Int-10) and “we just added [more] complexity” (Int-7). For example, committee standing orders were changed to reaffirm that individual councils “will be solely responsible for policy decisions for these statutory services” (Doc-32). In Case B, the switch from joint committee to lead authority only occurred in the final year of the partnership, as a last-ditch revival after several partners had already left. And in Case C, member councils went full circle in oversight stringency, "discuss[ing] and manag[ing] and monitor[ing] initially monthly, [then] quarterly, and then, toward the end, back to monthly” (Int-12).

Finally, concerning (d) increasing salience of ex-post interdependence as a proximate cause of termination: bounded rationality during project design, and adverse “spotlighting” events thereafter, both occurred among the dissolved cases. In fact, many interviewees spoke of failures to anticipate from the outset the downsides of partnership working. “Go into it with your eyes open … warts and all,” cautioned one (Int-2). “They were sold a different partnership [than they got]” (Int-13), said another. And “I spent a lot of time [explaining] what people had signed up for” (Int-15), recalled a third. The original proposals for Cases B and C even forecast that collaboration would mean “freeing-up management capacity within partner authorities to focus on their core business” (Doc-27), and a greater “ease of coordinating tasks” (Doc-28) – the exact opposite of what occurred in practice. Conversely, in sustained cases, partners were aware from the outset of the tradeoffs and compromises ahead. One (generally favorable) business case even contained a section titled, “Why is sharing so difficult?” (Doc-29).

As for events raising the salience of ex-post interdependence over time, this was most apparent in Case A during the “gruesome fallout” among councilors after three consecutive years of financial penalties. Housing Benefit is recognized as an extremely complex means-tested program to administer (Kemp Citation2007), and in 2011–12 the financial returns of 78 per cent of council were qualified by auditors (Audit Commission Citation2014). Case A’s problems were not unique, therefore; but their repetition year-on-year, coupled with political and media outcry, spotlighted the lack of leverage that each individual partner had over the issue of benefit accuracy for the partnership’s jurisdiction as a whole. This awakened them to external influences on performance in a domain where hitherto they were autonomous, hastening the partnership’s demise in order to “mitigate future financial penalties.”

Conclusion

Interdependence has long been central to our understanding of the onset of collaborative relations – in public administration, business management and organization theory alike. Mutual reliance to achieve some individually-unobtainable goal, or to avoid some mutually-damaging harm, motivates managers to voluntarily endure the disruption, risks, autonomy loss and cultural reorientation that collaboration entails. After commencement of inter-organizational relations, however, resource dependence theories have been said to “pay little or no attention to the ongoing sustainability of collaborative ventures” (Sharfman et al. Citation1991:182; see also Gray Citation1985; Gray and Wood Citation1991). Interdependence, in other words, has mostly explained collaborative beginnings; much less middles and endings.

In this article, however, we have shown that interdependence remains vital to understanding performance and behavior throughout the collaborative life cycle, and not only because the ex-ante trigger for partnering may disappear or transform over time (Seabright, et al. Citation1992). Rather, collaboration itself generates ex-post interdependence, affecting both the performance of the shared endeavor, and staff sentiment toward it, and so prompting a variety of non-trivial responses from managers. These range from building new coordinative capacity and making further delegations in order to “internalize” the problematic interconnections, to increasing governance stringency, turf wars, and even termination – where interdependent parties once more work independently.

Using the empirical example of inter-municipal cooperation in England, and the comparative case method, we have shown how accumulation of new contingencies and constraints in the wake of shared service adoption contributed to decisions about dissolving and replacing collaborative tax and social assistance services. Importantly, no partnership that achieved full operations was subsequently dissolved for allegedly failing to reap anticipated scale economies – the ex-ante trigger for the collaborations. Rather, it was the paradox of mitigating one problem by creating another with similar attributes (mutual dependence) that rendered the partnerships unstable. As Van de Ven and Walker (Citation1984:604–605) astutely note, therefore, “cooperation and antagonism have a common origin.”

This dual role of interdependence in both partnership formation and termination has implications for the practice of collaborative public management, and the role of scholarship in developing more effective partnerships. Despite well-documented differences between collaborative and conventional public service delivery (O'Toole Citation1997; Kettl Citation2006; although see McGuire Citation2006, for a critique), their shared preoccupation with coordinating interdependencies – whether internal or external, and whether stimulus for or artifact of the collaboration – represents an important point of convergence. As our study showed, inability to design structures and forge administrative capacity that produced rapid, efficient, and reliable coordination of work processes – the mantra of bureaucratic public administration – was instrumental in the breakdown of collaborations. Thus, when O’Toole cautions that “conventional theory may actually be counter-productive when applied inappropriately to network contexts” (1997:45), the qualifier “inappropriately” is essential, lest the proverbial baby is discarded with the bath water. Indeed, our analysis shows the continuing relevance of conventional administrative science to understanding the challenges of joint working. This can, for instance, help predict when the coordination of work processes will be more or less resource intensive, prone to error, or capable of being streamlined – which, as we have shown, directly affects collaborative performance and sustainability.

Our study contains several limitations. While it is theoretically valuable to distinguish objective and subjective interdependence, empirically these are notoriously difficult to separate and measure (in international relations, for instance, see Tetreault Citation1980). Indeed, contrary to the confident assertions in our qualitative data that scale economies were achieved by sustained and dissolved partnerships alike, it seems likely that many councils over-estimated their ex-ante interdependence when forming shared services, so large are these organizations relative to the minimum efficient scale for the delivery of this service (Elston et al. Citation2023b). Consequently, our case analysis may overstate the degree to which sustained collaborations owe their longevity to attaining a favorable balance of costs and benefits, rather than rational undoing of these reforms being prohibited by, say, network inertia or leadership pride in expensive pet projects. In addition, whilst confining the empirical analysis to just two services helped control for task-related influences on termination risk, it reduces external validity, as does the focus solely on English local government, which is a recognized outliner internationally (except perhaps in Scandinavia) in terms of jurisdiction size and degree of control exercised by central government. Future work should therefore expand the framework presented here to new jurisdictions with different institutional arrangements, as well as compare multiple service areas. This should include public functions that are less transactional and more discretionary than tax and benefit administration, and which may display even greater interconnectivity across policy areas and thus more pronounced risk of ex-post interdependence.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the council officers who provided documents and participated in interviews, and to Kai Wegrich, Jade Wong, María José Canel, John Boswell, Ellen Stewart, and two anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Elston

Thomas Elston ([email protected]) is Associate Professor of Public Administration at the University of Oxford. His research, teaching, and advisory work relate to the organization and management of government and public services. He is the author of Understanding and Improving Public Management Reform (Policy Press), and has led studies into collaboration, organizational resilience, performance auditing, and political-administrative relations.

Maike Rackwitz

Maike Rackwitz ([email protected]) researches digital and urban governance, with a particular focus on public sector reform and decision-making in national and local governments. She has published on topics related to collaboration, digitalization, and corporatization. She received her PhD in Governance from the Hertie School, Berlin, and currently works as a public sector consultant.

Germà Bel

Germà Bel ([email protected]) is a Professor of Economics and Public Policy, and Director of the Institute of Research on Applied Economics (IREA-UB) at the Universitat de Barcelona. His research interests and publications focus on local government reform, with a special emphasis on privatization, regulation, and cooperation in public services delivery, infrastructure and transport, and environmental challenges.

Notes

1 Literature typically refers to our empirical case as an instance of inter-municipal “cooperation,” though this is also regarded as a subtype of “collaborative” public management. Given our reliance on organization theory, we reserve the term “coordination” to mean mutual adjustment of behavior among interdependent actors. Consequently, we cannot regard these three terms as being arrayed on a spectrum of horizontal integration among organizations (Keast et al. Citation2007).

2 Strictly, the 32 London boroughs are also in a two-tier arrangement with the Greater London Authority.

3 District rather than county councils are responsible for revenues and benefits; but counties may still enter the inter-municipal cooperation if it is “multi-purpose” and provides additional services such as accounting or procurement (see dashed lines in Cases B and L in ).

4 In the discussion section, citations to data sources are provided only for new data not previously presented.

5 One exception concerned accountability, for which some mutual gain was said to derive from the presence of additional veto players: “You’re being challenged all the time [by] three organizations … which … makes for better decisions” (Int-13).

References

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2003. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- Aiken, M., and J. Hage. 1968. “Organizational Interdependence and Intra-Organizational Structure.” American Sociological Review 33(6):912–30. doi: 10.2307/2092683.

- Aldag, A. M., and M. Warner. 2018. “Cooperation, Not Cost Savings: Explaining Duration of Shared Service Agreements.” Local Government Studies 44(3):350–70. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2017.1411810.

- Alexander, E. R. 1995. How Organizations Act Together: Interorganizational Coordination in Theory and Practice. Luxembourg: Gordon and Breach.

- Arntsen, B., D. O. Torjesen, and T.-I. Karlsen. 2021. “Asymmetry in Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Health Services – How Does It Affect Service Quality and Autonomy?” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 273:113744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113744.

- Audit Commission. 2001. Learning from Inspection: Housing Benefit Administration. London: Audit Commission.

- Audit Commission. 2014. Councils’ Expenditure on Benefits Administration: Using Data from the Value for Money Profiles. London: Audit Commission.

- Baldwin, D. A. 1980. “Interdependence and Power: A Conceptual Analysis.” International Organization 34(4):471–506. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300018828.

- Bel, G., and M. Sebő. 2021. “Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Really Reduce Delivery Costs? An Empirical Evaluation of the Role of Scale Economies, Transaction Costs, and Governance Arrangements.” Urban Affairs Review 57(1):153–88. doi: 10.1177/1078087419839492.

- Bel, G., and M. E. Warner. 2015. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation and Costs: Expectations and Evidence.” Public Administration 93(1):52–67. doi: 10.1111/padm.12104.

- Bingham, L. B. and R. O'Leary (Eds.). 2008. Big Ideas in Collaborative Public Management. Armonnk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Blau, P. M., and W. R. Scott. 1963. Formal Organizations: A Comparative Approach. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Carlsson, V., D. Mukhtar-Landgren, and M. Fred. 2022. “Local Autonomy and the Partnership Principle: Collaborative Governance in the European Social Fund in Sweden.” Public Money & Management:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2076516.

- Chen, C.-A., and B. Bozeman. 2012. “Organizational Risk Aversion: Comparing the Public and Non-Profit Sectors.” Public Management Review 14(3):377–402. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2011.637406.

- Chen, X., and A. A. Sullivan. 2023. “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Why Participants Leave Collaborative Governance Arrangements.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 33(2):246–61. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muac024.

- Chisholm, D. 1989. Coordination without Hierarchy: Informal Structures in Multiorganizational Systems. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cook, K. S. 1977. “Exchange and Power in Networks of Interorganizational Relations.” The Sociological Quarterly 18(1):62–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1977.tb02162.x.

- Deeds, D. L., and F. T. Rothaermel. 2003. “Honeymoons and Liabilities: The Relationship between Age and Performance in Research and Development Alliances.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 20(6):468–84. doi: 10.1111/1540-5885.00043.

- Department for Work and Pensions 2020. Annual Report and Accounts (HC 401). London: The Stationery Office.

- Deutsch, M. 1949. “A Theory of Co-Operation and Competition.” Human Relations 2(2):129–52. doi: 10.1177/001872674900200204.